Abstract

Dermatomyositis is a rare, type I interferon-driven autoimmune disease, which can affect muscle, skin and internal organs (especially the pulmonary system). In 2021, we have noted an increase in new-onset dermatomyositis compared to the years before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in our center. We present four cases of new-onset NXP2 and/or MDA5 positive dermatomyositis shortly after SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. Three cases occurred within days after vaccination with Comirnaty and one case after SARS-CoV-2 infection. All patients required intensive immunosuppressive treatment. MDA5 antibodies could be detected in three patients and NXP2 antibodies were found in two patients (one patient was positive for both antibodies). In this case-based systematic review, we further analyze and discuss the literature on SARS-CoV-2 and associated dermatomyositis. In the literature, sixteen reports (with a total of seventeen patients) of new-onset dermatomyositis in association with a SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination were identified. Ten cases occurred after infection and seven after vaccination. All vaccination-associated cases were seen in mRNA vaccines. The reported antibodies included for instance MDA5, NXP2, Mi-2 and TIF1γ. The reviewed literature and our cases suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination may be considered as a potential trigger of interferon-pathway. Consequently, this might serve as a stimulus for the production of dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies like MDA5 and NXP2 which are closely related to viral defense or viral RNA interaction supporting the concept of infection and vaccination associated dermatomyositis.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccines, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Dermatomyositis is a rare disease with an incidence of 1 to 15 per million [1]. Apart from muscle and skin, the disease can also affect other organs, such as lungs, heart, and blood vessels with varying clinical outcomes, depending on the specific antibody [2]. Although the pathophysiology has not yet been fully elucidated, type I interferon (IFN) is now known to play a key role in the development of the disease. Induction of interferon-stimulated genes can be seen in muscle biopsies of dermatomyositis and type I IFN signature has been reported in peripheral blood samples [3, 4]. Specifically, anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (anti-MDA5) antibody-positive dermatomyositis patients showed very high serum type I IFN signature [5].

Interestingly, MDA5 positive dermatomyositis and SARS-CoV-2 infection share clinical and laboratory features, such as inflammatory cytokine profile and interstitial lung involvement [6]. Furthermore, creatine kinase (CK) elevation has been reported in up to 27% of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients [7]. Inflammatory myopathy has been detected in infected patients as well as autoantibody production against nuclear matrix protein-2 (NXP2) and MDA5 without clinical symptoms of dermatomyositis but a correlation of worse pulmonary outcomes [8, 9].

The newly developed messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine is known to induce an IFN signaling, partly also via MDA5 [10]. After SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, elevated IFN levels can be detected in healthy individuals [11]. So far, the development of autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [12] and autoimmune myositis [13] after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination have been reported in a few case reports.

Both, SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination, may lead to new-onset dermatomyositis via autoimmunity due to interferon signaling, hyperinflammation and autoantibody induction.

Case presentation

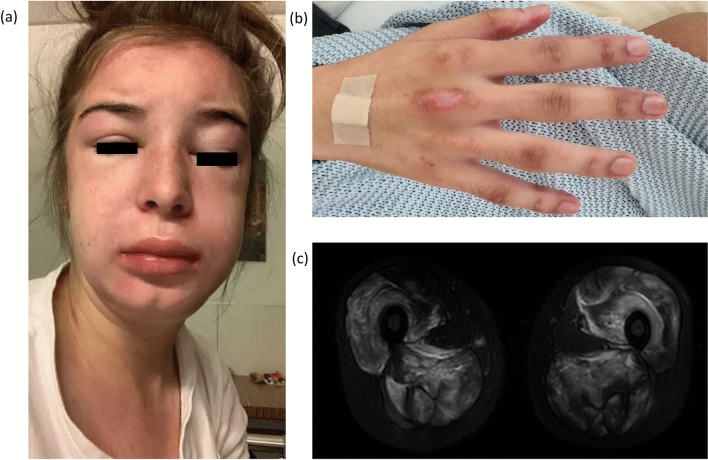

We report four cases with the occurrence of MDA5 and/or NXP2 positive dermatomyositis directly linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. Our sample comprises three female and one male patient ranging from 19 to 57 years of age. Three patients experienced the onset of dermatomyositis shortly after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination with BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) (1–7 days) and one patient 2 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Intriguingly, patient 1 developed dermatomyositis after his first vaccination, whereas dermatomyositis in patients 3 and 4 evolved after the second vaccination. All patients showed typical skin manifestations and reported proximal myalgia (Fig. 1). Two patients initially presented with arthritis. One patient had severe dyspnea, and another had excessive dysphagia. Only two patients had elevated CK levels. MDA5 antibodies could be detected in three patients and NXP2 antibodies were found in two patients (patient 3 was positive for both antibodies). In three patients, muscle magnetic resonance imaging was performed, showing bilateral proximal myositis. Patient 1, furthermore, developed rapid-progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD). Skin and muscle biopsies showed pathologies consistent with dermatomyositis.

Fig. 1.

Patients’ images: a Patient 2: facial swelling, heliotrope erythema. b Patient 1: Gottron papules c Patient 2: magnetic resonance imaging scan (T2) showing bilateral active myositis in the adductors and extensors of the thighs

All patients required immunosuppression and were treated with glucocorticoid pulse therapy. Whilst patients 3 and 4 showed mild symptoms that were successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine and azathioprine; patients 1 and 2 had a long hospitalization with multiple intensive care treatments due to life-threatening major organ involvements. Both patients required extensive immunosuppression including ciclosporin A, mycophenolate mofetil and rituximab. Table 1 displays patients’ characteristics and therapeutic concepts.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19 | 20 | 57 | 51 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Female |

| Symptom onset | 5 days after 1st vaccination with BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) | 2 weeks after infection | 1 week after 2nd vaccination with BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) | 1 day after 2nd vaccination with BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) |

| Skin manifestation | Gottron papules and Gottron signs over extensor sides of elbows and knees, Hiker’s feet | Heliotrope erythema, Gottron papules, scalp exanthem, V and Shawl sign, facial swelling | Heliotrope erythema, Gottron papules, Gottron signs at the elbows, erythematous macular rash on forehead, Shawl sign, periungual erythematous swelling | Reddened painful fingertips (Chillblain lesions) and periungual erythematous swelling, Gottron papules, heliotrope rash and occipital lesions |

| Organ involvement | Proximal myalgia, arthritis, RP-ILD | Proximal myalgia (including extensive dysphagia) | Proximal myalgia | Proximal myalgia, arthritis |

| Muscle MRI findings | Bilateral myositis of muscles inserting trochanter minor and major | Bilateral myositis of muscles of the pelvic hip girdle and thighs | Bilateral myositis of muscles of the shoulders and thighs | No MRI performed |

| Antinuclear antibody | < 1:80 | 1:640 | 1:2560 | 1:5120 |

| Myositis specific antibodies | MDA5, RO-52 | NXP2 | MDA5, NXP2 | MDA5 |

| CK (U/l) (normal < 190) | 1074 | 19,647 | 146 | 66 |

| LDH (U/l) (normal 120–250) | 839 | 1903 | 215 | 125 |

| CRP (mg/l) (normal < 5) | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 |

| Biopsies |

Muscle: mild myopathy and increased MHC I expression Skin: perivascular neutrophilic infiltrates |

Muscle: necrosis, expression of MAC and MHC I Skin: interface-dermatitis and perivascular lymphocytic dermatitis |

No biopsy performed | Skin: perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates consistent with DM |

| Treatment | Glucocorticoids, IVIG, Tofacitinib, MMF, Rituximab, Ciclosporin A, Anakinra, Nintedanib, Daratumumab | Glucocorticoids, IVIG, MMF, Ciclosporin A, Tofacitinib, Rituximab | Glucocorticoids, Hydroxychloroquine, Azathioprine | Glucocorticoids, MTX s.c., Hydroxychloroquine, Azathioprine |

RP-ILD Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, MDA5 Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5, NXP2 Nuclear matrix protein 2, CK Creatine kinase, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase, AST Aspartate aminotransferase, CRP C-reactive protein, MHC I Major histocompatibility complex, MAC Membrane attack complex, DM Dermatomyositis, IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin, MMF Mycophenolate Mofetil, MTX Methotrexate

Moreover, we have noted an increase of dermatomyositis diagnoses in our center since the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic with almost a doubling of new-onset dermatomyositis in overall inpatient cases from 0.06 to 0.15% (2017–2020) up to 0.26% in the year 2021 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of new-onset dermatomyositis (DM) over the last 5 years

| Year | New-onset DM casesa | Autoantibodies | Total number of inpatients | Percentageb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2 |

NXP2, Ro52 Mi2 |

1671 | 0.12% |

| 2018 | 2 |

MDA5 Antibody negative |

1342 | 0.15% |

| 2019 | 1 | Mi2 | 1207 | 0.08% |

| 2020 | 1 | Mi2, TIF1γ | 1720 | 0.06% |

| 2021 | 5 |

NXP2 MDA5, Ro52 MDA5 NXP2, MDA5 Antibody negative |

1895 | 0.26% |

aparaneoplastic associated DM excluded

bpercentage = (new-onset DM case) ÷ (total number of inpatients)

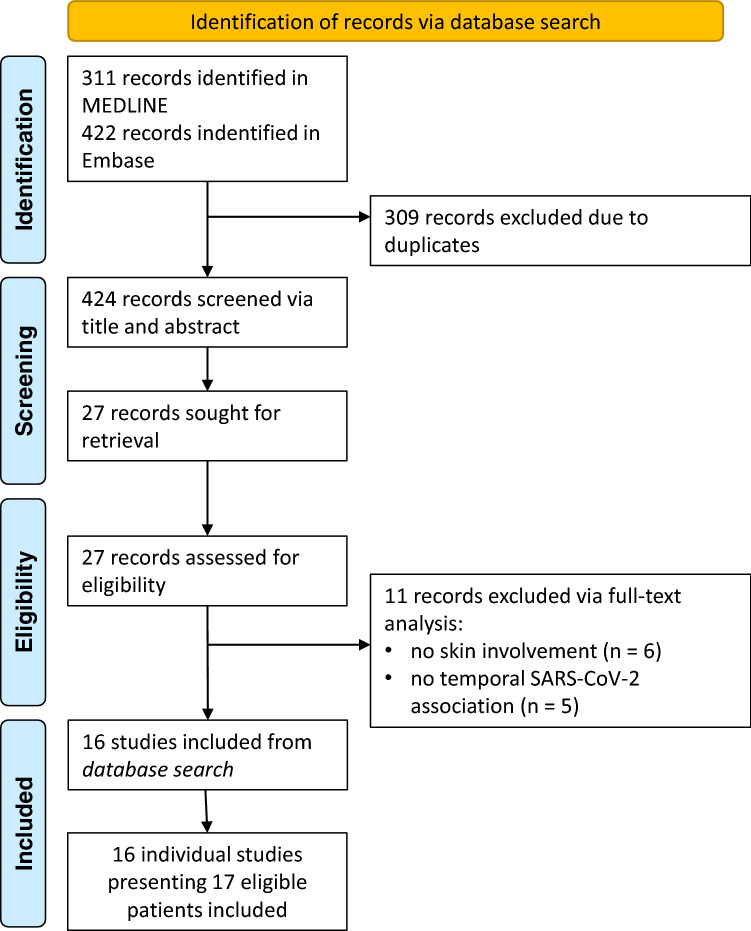

Methods

To identify previously reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 associated dermatomyositis, a systematic review of the literature according to PRISMA guidelines was performed. MEDLINE and Embase were systematically searched until the 25th of May 2022. The search strategy included the following terms to identify dermatomyositis cases: ‘myositis’, ‘dermatomyositis’, ‘polymyositis’, ‘rhabdomyolysis’, ‘antisynthetase syndrome’ and ‘inflammatory myopathy’. SARS-CoV-2 association was established with ‘SARS-CoV-2’, ‘COVID-19’ and ‘coronavirus’. All terms were used to search titles and abstracts of publications. The search was conducted as (‘myositis’ OR ‘dermatomyositis’ OR ‘polymyositis’ OR ‘rhabdomyolysis’ OR ‘antisynthetase syndrome’) AND (‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘coronavirus’). The database search in MEDLINE identified 311 publications, the database search in Embase 422, which were independently reviewed by two authors (MTH, NR). A third independent reviewer (MK) decided in case of discrepancy. Based on the EULAR/ACR criteria for (juvenile) dermatomyositis [14], new-onset cases of dermatomyositis with a temporal relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination were included in this review. Non-English articles, reviews without description of detailed case information and congress abstracts were excluded. Finally, 16 studies reporting 17 cases were included. The methodology flowchart is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Methodology flowchart of systematic literature review. n number

Results

The clinical, laboratory, radiographic and histopathologic features of SARS-CoV-2 infection-/vaccination-associated dermatomyositis of the identified 17 cases of the systematic review are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 [13, 15–29]. Interestingly, 70.6% of the patients were female, mean age was 52.4 years. Ten cases occurred after infection and seven after vaccination. All reported vaccinations were mRNA vaccination. Six of these seven cases were after BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) and one after mRNA-1273 (Spikevax) vaccination. All identified cases had pathognomonic skin manifestations. Myocardial involvement was assumed in two cases (one after infection and one after Comirnaty vaccination). Lung involvement was reported in seven patients. Five of these lung involvements were reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection. One patient with MDA5, and two patients with NXP2-antibodies were reported. Furthermore, four Mi-2 positive patients, two RNP/TIF1γ, respectively, and one Jo-1 positive patient were identified. All patients received glucocorticoids and nine patients IVIG. One patient had a lethal disease course.

Table 3.

Clinical, laboratory, radiologic and histopathologic features of SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination associated dermatomyositis cases found in systematic search [13, 15–29]a

| Author, year | Patient’s age in years, sex | Infection/ 1st, 2nd vaccination (with) | Myositis-specific antibodies | Creatine kinase | Muscle biopsy | MRI | Extramuscular involvement | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borges et al., 2021 | 36, Female | Infection | Mi-2 | 3518 U/l | Not performed | Not performed | Skin | GC | Improvement |

| Camargo Coronel et al. 2022 | 76, Female | 2nd vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | Mi-2 | 3368 U/l | Consistent with DM | Not performed | Skin, dysphagia | GC, MTX | Improvement |

| Derbel et al. 2021 | 61, Female | Infection | Jo-1 | 1052 U/l | Not performed | Not performed | Skin, possibly lung, joints | GC | Improvement |

| Gokhale et al. 2020 | 64, Male | Infection | Negative | 990 U/l | Not performed | Positive | Skin, possibly lung, dysphagia | GC, IVIG, MMF | Improvement |

| Gokhale et al. 2020 | 50, Male | Infection | Mi-2 | 1169 U/l | Not performed | Positive | Skin, possibly lung | GC, IVIG, MTX | Improvement |

| Gouda et al. 2022 | 43, Female | 2nd Vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | RNP | 3358 µg/l | Not performed | Positive | Skin, lung, joints | GC, MMF, HCQ | Improvement |

| Ho et al. 2021 | 58, Male | Infection | Negative | 9684 U/l | Consistent with DM | Not performed | Skin, possibly lung | GC, MTX | Improvement |

| Keshtkarjahromie et al. 2021 | 65, Female | Infection | MDA5 | 1222 U/l | Not performed | Positive | Skin, possibly lung, joints | GC, IVIG | Death |

| Kreuter et al. 2022 | 68, Female | 2nd Vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | TIF1γ | Not stated | Not performed | Not performed | Skin | GC | Improvement |

| Lee et al. 2022 | 53, Male | 2nd vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | NXP2 | 14,659 U/l | Consistent with DM | Positive | Skin, dysphagia | GC, IVIG, RTX | Improvement |

| Liquidano-Perez et al. 2021 | 4, Female | Infection | RNP | 403 mg/dl | Not performed | Positive | Skin, possibly lung, dysphagia | GC, IVIG, MTX, CsA | Improvement |

| Okada et al. 2021 | 64, Female | Infection | NXP2 | 1495 U/l | Consistent with DM | Positive | Skin | GC, AZA | Improvement |

| Rodero et al. 2022 | 15, Female | Infection | Negative | 545 U/l | Consistent with DM | Not performed | Skin | GC, IVIG, Tofacitinib | Improvement |

| Shahidi Dadras et al. 2021 | 58, Female | Infection | Negative | 2611 U/l | Not performed | Not performed | Skin, myocardial involvement | GC, MTX, HCQ | Improvement |

| Venkateswaran et al. 2022 | 43, Male | 1st Vaccination (mRNA-1273, Spikevax) | Negative | Not stated | Not performed | Not performed | Skin | GC, IVIG | Improvement |

| Vutipongsatorn et al. 2022 | 55, Female | 1st Vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | Mi-2 | 11,330 U/l | Not performed | Positive | Skin, myocardial involvement | GC, IVIG, CYC | Improvement |

| Wu et al. 2022 | 77, Female | 1st Vaccination (BNT162b2, Comirnaty) | TIF1γ | 4476 U/l | Consistent with DM | Not performed | Skin | GC, IVIG | Improvement |

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, DM Dermatomyositis, GC: Glucocorticoids, MTX Methotrexate, IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin, MMF Mycophenolate Mofetil, RNP Ribonucleoprotein, TIF1γ Transcription intermediary factor 1γ, MDA5 Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5, NXP2 Nuclear matrix protein 2, RTX Rituximab, CsA Ciclosporin A, AZA Azathioprine, HCQ Hydroxychloroquine, CYC Cyclophosphamide

aalphabetically ordered

Table 4.

Analysis of clinical, laboratory, radiologic and histopathologic features of SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination associated dermatomyositis cases found in the systematic review [13, 15–29]

| Total | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 5 | 29.4% |

| Female | 12 | 70.6% | |

| Age (years) | Mean | 52.4 | – |

| Median | 58.0 | – | |

| Infection | Negative | 7 | 41.2% |

| Positive | 10 | 58.8% | |

| Vaccination | Negative | 10 | 58.8% |

| Positive | 7 | 41.2% | |

| Vaccine | BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) | 6 | 85.7% |

| mRNA-1273 (Spikevax) | 1 | 14.3% | |

| First vaccine | 3 | 42.9% | |

| Second vaccine | 4 | 57.1% | |

| MSA | MDA5 | 1 | 5.9% |

| NXP2 | 2 | 11.8% | |

| Mi-2 | 4 | 23.5% | |

| RNP | 2 | 11.8% | |

| TIF1γ | 2 | 11.8% | |

| Jo-1 | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Negative | 5 | 29.4% | |

| Creatine kinase (U/l) | Mean | 3230 | – |

| Median | 2053 | – | |

| Muscle biopsy | Not performed | 11 | 64.7% |

| Performed | 6 | 35.3% | |

| Consistent with myositis | 5 | 29.4% | |

| MRI | Not performed | 9 | 52.9% |

| Performed | 8 | 47.1% | |

| Consistent with myositis | 8 | 47.1% | |

| Skin | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 17 | 100.0% | |

| Not reported | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Lung | Negative | 6 | 35.3% |

| Positive | 7 | 41.2% | |

| Possible SARS-CoV-2 manifestation | 5 | 29.4% | |

| Not reported | 4 | 23.5% | |

| Myocardial involvement | Negative | 1 | 5.9% |

| Positive | 2 | 11.8% | |

| Not reported | 14 | 82.4% | |

| Dysphagia | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 4 | 23.5% | |

| Not reported | 13 | 76.5% | |

| Arthritis | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 3 | 17.6% | |

| Not reported | 14 | 82.4% | |

| Glucocorticoids | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 17 | 100.0% | |

| Not reported | 0 | 0.0% | |

| IVIG | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 9 | 52.9% | |

| Not reported | 8 | 47.1% | |

| CYC | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Not reported | 16 | 94.1% | |

| RTX | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Not reported | 16 | 94.1% | |

| MMF | Negative | 0 | 0.0% |

| Positive | 5 | 29.4% | |

| Not reported | 12 | 70.6% | |

| Other treatment | Cyclosporine | 1 | 5.9% |

| Azathioprine | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Tofacitinib | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 2 | 11.8% | |

| Outcome | Death | 1 | 5.9% |

| Clinical improvement | 16 | 94.1% | |

MSA Myositis-specific antibodies, MDA5 Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5, NXP2 Nuclear matrix protein 2, RNP Ribonucleoprotein, TIF1γ Transcription intermediary factor 1γ, MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin, CYC Cyclophosphamide, RTX Rituximab, MMF Mycophenolate Mofetil

Discussion

The reported cases vary in autoimmune serology, clinical course, and prognosis. Nevertheless, the common feature was the new-onset dermatomyositis shortly after SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination.

Interestingly, lung involvement was the most frequent manifestation (despite skin and muscle). We would like to highlight, that after SARS-CoV-2 infection, radiographically changes of the lung might sometimes be hard to differentiate between infection- or autoimmune-disease related.

In general, viral infections are a well-known trigger of dermatomyositis [30]. Furthermore, seasonal clustering of MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with lower incidence in European summer months is known [31].

In the systematic database search, we identified ten cases of new-onset dermatomyositis after SARS-CoV-2 infection and one patient in our cohort.

In some of these cases apart from classical clinical and laboratory findings of dermatomyositis an IFN signature as well as autoinflammatory clinical aspects have been reported [15, 17, 26].

Consistent with the results of our center, Gokhale et al. also reported an increase of new-onset dermatomyositis in a center in Mumbai with five new cases of dermatomyositis in 6 months from April 2020 (usually one to two new cases per year) [20]. Furthermore, Movahedi et al. described an increase of new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis in Iran. Regularly, two to four new cases were admitted each year from the years 2014 to 2019, whereas from February 2020 to February 2021 eight new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis cases were registered [32].

MDA5- and NXP2-antibodies were reported in each four of the 21 identified cases (16.7%, respectively). Both antibodies are associated with viral interaction in general: MDA5 is an intracellular sensor for viral RNA, triggering proinflammatory immune response especially involving type I IFN [32]. NXP2 shows RNA binding activity and upregulation of its expression has been detected in influenza infection [33]. Furthermore, the two antibodies have been associated with SARS-CoV-2-infections: In a small study of 35 SARS-CoV-2 patients, de Santis et al. reported the occurrence of NXP2 (n = 3) and MDA5 antibodies (n = 1). Both antibodies were associated with a severe disease course [9]. In SARS-CoV-2 infection, MDA5 was shown to guide an innate immune response via IFN signaling [34]. It has been hypothesized, that viral RNA may trigger MDA5 expression and cell damage may lead to MDA5 release followed by autoantibody production [35]. In addition, Wang et al. demonstrated correlative evidence between high titer of anti-MDA5 antibodies and lethal outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of the 274 patients analyzed, 48.2% were anti-MDA5 positive and high antibody titer (> 10 U/ml) was more frequent in non-survivors [36].

In addition, muscle involvement seems to be an important feature of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Elevated CK was detected in 27% of the SARS-CoV-2 patients [7]. Furthermore, inflammatory myopathy was seen in SARS-CoV-2 patients without significant signs of viral infection of myocytes suggesting autoimmune features [8]. In addition, Manzano et al. discovered the presence of myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), a type I IFN induced protein, in the muscle biopsy of an SARS-CoV-2 patient with proximal myopathy, suggesting parts of the inflammatory myopathy caused by interferonopathy [38]. Another study also showed immune-mediated and inflammatory myopathy in 16 of 35 autopsies of deceased SARS-CoV-2 patients with high expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I and MxA expression in some cases, which was not seen in controls [39], underlining a possible IFN and cytokine triggered mechanism. These MHC I and IFN patterns found in muscles of SARS-CoV-2 patients closely resemble the pattern found in muscle biopsies in dermatomyositis [2].

Furthermore, the development of autoimmune diseases after vaccination by molecular mimicry and bystander activation in genetically susceptible individuals has frequently been discussed [40, 41]. There have been also a few case reports of vaccinations as a potential trigger of dermatomyositis but no significant association has been established in previous vaccination studies [42].

Rare, but possible side effects after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, such as the development of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), myocarditis, vasculitis, and thrombotic thrombocytopenia have been reported [12, 43–46]. In the last few months, since the beginning of the global vaccination campaign, apart from the mentioned autoimmune diseases after vaccination, myositis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has been reported. In the reviewed literature and our cohort, we detected ten patients with new-onset dermatomyositis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. All patients received a mRNA vaccination. Interestingly, six patients developed the disease after the second vaccination. Whilst mRNA vaccination seems to be more prevalent for dermatomyositis-association, other autoimmune diseases like thrombotic thrombocytopenia or SLE seem more likely to occur after adenovirus vector vaccine like ChAdOx1-S. Autoantibody production and activation is discussed as possible mechanism [12]. Furthermore, there are reports of myositis in temporal association to ChAdOx1-S vaccination [37].

In SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, the mRNA enters human cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and induces an immune response to develop spike antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection and memory T and B cells [47]. During the development of mRNA vaccine, a strong type I IFN response with MDA5 as one of the possible RNA sensing and IFN inducing mechanisms was seen [10]. Thus, the nowadays used mRNA vaccines are containing nucleoside-modified mRNA, which reduces the IFN pathway activation [10, 48]. Nevertheless, increased type I IFN levels were detected after mRNA vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, but they were comparable to IFN levels after influenza vaccination [11]. As dermatomyositis is known to be an IFN driven disease, there might be a tipping point inducing autoimmunity due to the vaccination response in some patients.

Most recently, Yin et al. were able to prove the importance of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathophysiology of dermatomyositis [49]. NLRP3 inflammasome activation has also been detected in myocarditis after mRNA vaccination. It is assumed, that similarly to SARS-CoV-2 infection, spike protein might trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activity, or that the lipid nanoparticles used, might stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome [50, 51]. This might present another additional pathomechanism in the development of autoimmune diseases like dermatomyositis following mRNA vaccination.

In summary, this case series and the reviewed literature suggest an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination and the development of dermatomyositis, since all reported cases occurred within a very short timeframe after vaccination or infection. Possible pathophysiological mechanisms may include type I IFN pathways, the NLRP3 inflammasome and the induction of autoantibody production (especially of those antibodies, which are closely related to viral defense or viral RNA interaction like MDA5 and NXP2).

Due to the limited number of identified cases, we would like to emphasize that the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination and the development of dermatomyositis does not necessarily prove causality, and further research is needed.

We would like to underline that the benefit of SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations highly outweighs possible very rare autoimmune phenomena. Nevertheless, rheumatologists should be aware of possible associations between dermatomyositis and SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination to maintain optimal medical management.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the conception of the manuscript and reviewed and edited the article carefully. The systematic database search was conducted by MTH, MK and NR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MTH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the anonymization of patients and for the privacy of individuals that participated in this case series. Non-confidential data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Standard

This manuscript does not contain human or animal studies. All patients gave written consent to anonymously publishing their cases, including pictures, in which the patients can’t be identified.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kronzer VL, Kimbrough BA, Crowson CS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and mortality of dermatomyositis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021 doi: 10.1002/acr.24786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:267–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg SA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, et al. Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:664–678. doi: 10.1002/ana.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baechler EC, Bauer JW, Slattery CA, et al. An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Mol Med. 2007;13:59–68. doi: 10.2119/2006-00085.Baechler. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono N, Kai K, Maruyama A, et al. The relationship between type 1 IFN and vasculopathy in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:918. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo Y, Kaneko Y, Takei H, et al. COVID-19 shares clinical features with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 positive dermatomyositis and adult Still's disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:631–638. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/44kaji. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitscheider L, Karolyi M, Burkert FR, et al. Muscle involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3411–3417. doi: 10.1111/ene.14564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aschman T, Schneider J, Greuel S, et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and immune-mediated myopathy in patients who have died. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:948–960. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Santis M, Isailovic N, Motta F, et al. Environmental triggers for connective tissue disease: the case of COVID-19 associated with dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021;33:514–521. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, et al. mRNA vaccines—a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:261–279. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ntouros PA, Vlachogiannis NI, Pappa M, et al. Effective DNA damage response after acute but not chronic immune challenge: SARS-CoV-2 vaccine versus systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 2021;229:108765. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Xu Z, Wang P, et al. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology. 2021 doi: 10.1111/imm.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vutipongsatorn K, Isaacs A, Farah Z. Inflammatory myopathy occurring shortly after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03266-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M, et al. 2017 European league against rheumatism/American college of rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2271–2282. doi: 10.1002/art.40320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keshtkarjahromi M, Chhetri S, Balagani A, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis and COVID-19 infection. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:59. doi: 10.1186/s41927-021-00225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee AYS, Lee C, Brown DA, et al. Development of anti-NXP2 dermatomyositis following Comirnaty COVID-19 vaccination. Postgrad Med J. 2022 doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2022-141510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada Y, Izumi R, Hosaka T, et al. Anti-NXP2 antibody-positive dermatomyositis developed after COVID-19 manifesting as type I interferonopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho BVK, Seger EW, Kollmann K, et al. Dermatomyositis in a COVID-19 positive patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camargo Coronel A, Jiménez Balderas FJ, Quiñones Moya H, et al. Dermatomyositis post vaccine against SARS-COV2. BMC Rheumatol. 2022;6:20. doi: 10.1186/s41927-022-00250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gokhale Y, Patankar A, Holla U, et al. Dermatomyositis during COVID-19 pandemic (a case series): is there a cause effect relationship? J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gouda W, Albasri A, Alsaqabi F, et al. Dermatomyositis following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e32–e32. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu M, Karim M, Ashinoff R. COVID-19 vaccine associated dermatomyositis. JAAD Case Rep. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liquidano-Perez E, García-Romero MT, Yamazaki-Nakashimada M, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;121:26–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkateswaran K, Aw DC-W, Huang J, et al. Dermatomyositis following COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022 doi: 10.1111/dth.15479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahidi Dadras M, Rakhshan A, Ahmadzadeh A, et al. Dermatomyositis-lupus overlap syndrome complicated with cardiomyopathy after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a new potential trigger for musculoskeletal autoimmune disease development. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04931–e04931. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodero MP, Pelleau S, Welfringer-Morin A, et al. Onset and relapse of juvenile dermatomyositis following asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42:25–27. doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-01119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borges NH, Godoy TM, Kahlow BS. Onset of dermatomyositis in close association with COVID-19-a first case reported. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:SI96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derbel A, Guermazi M, El Moctar EM, et al. Dermatomyositis following COVID-19 infection. Rev Med Interne. 2021;42:A445. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2021.10.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreuter A, Lausch S, Burmann S-N, et al. Onset of amyopathic dermatomyositis following mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol n/a. 2022 doi: 10.1111/jdv.18211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bax CE, Maddukuri S, Ravishankar A, et al. Environmental triggers of dermatomyositis: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:434. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toquet S, Granger B, Uzunhan Y, et al. The seasonality of dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibody: an argument for a respiratory viral trigger. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20:102788. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Movahedi N, Ziaee V. COVID-19 and myositis; true dermatomyositis or prolonged post viral myositis? Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19:86. doi: 10.1186/s12969-021-00570-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ver Lorena S, Marcos-Villar L, Landeras-Bueno S, et al. The cellular factor NXP2/MORC3 is a positive regulator of influenza virus multiplication. J Virol. 2015;89:10023–10030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01530-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin X, Riva L, Pu Y, et al. MDA5 governs the innate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in lung epithelial cells. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108628. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta P, Machado PM, Gupta L. Understanding and managing anti-MDA 5 dermatomyositis, including potential COVID-19 mimicry. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1021–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04819-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang G, Wang Q, Wang Y, et al. Presence of anti-MDA5 antibody and its value for the clinical assessment in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2021;12:791348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.791348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta K, Sharma GS, Kumar A. COVID-19 vaccination-associated anti-Jo-1 syndrome. Reumatologia. 2021;59:420–422. doi: 10.5114/reum.2021.111836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manzano GS, Woods JK, Amato AA. Covid-19-associated myopathy caused by type I interferonopathy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2389–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2031085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suh J, Mukerji SS, Collens SI, et al. Skeletal muscle and peripheral nerve histopathology in COVID-19. Neurology. 2021;97:e849. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vadalà M, Poddighe D, Laurino C, et al. Vaccination and autoimmune diseases: is prevention of adverse health effects on the horizon? EPMA J. 2017;8:295–311. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0101-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez-Pintó I, Shoenfeld Y. Myositis and Vaccines. Hoboken: Wiley Online Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orbach H, Tanay A. Vaccines as a trigger for myopathies. Lupus. 2009;18:1213–1216. doi: 10.1177/0961203309345734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu Mouch S, Roguin A, Hellou E, et al. Myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39:3790–3793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrido I, Lopes S, Simões MS, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis after COVID-19 vaccine—more than a coincidence. J Autoimmun. 2021;125:102741. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shakoor MT, Birkenbach MP, Lynch M. ANCA-associated vasculitis following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78:611–613. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wack S, Patton T, Ferris LK. COVID-19 vaccine safety and efficacy in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease: review of available evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y-D, Chi W-Y, Su J-H, et al. Coronavirus vaccine development: from SARS and MERS to COVID-19. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27:104. doi: 10.1186/s12929-020-00695-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin X, Han G-C, Jiang X-W, et al. Increased expression of the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome in dermatomyositis and polymyositis is a potential contributor to their pathogenesis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:1047–1052. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.180528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Theobald SJ, Simonis A, Georgomanolis T, et al. Long-lived macrophage reprogramming drives spike protein-mediated inflammasome activation in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13:e14150. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Won T, Gilotra NA, Wood MK, et al. Increased interleukin 18-dependent immune responses are associated with myopericarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Front Immunol. 2022;13:851620. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.851620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the anonymization of patients and for the privacy of individuals that participated in this case series. Non-confidential data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.