Abstract

Pseudomonas fluorescens, a gram-negative psychrotrophic bacterium, secretes a thermostable lipase into the extracellular medium. In our previous study, the lipase of P. fluorescens SIK W1 was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli, but it accumulated as inactive inclusion bodies. Amino acid sequence analysis of the lipase revealed a potential C-terminal targeting sequence recognized by the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. The genetic loci around the lipase gene were searched, and a secretory gene was identified. Nucleotide sequencing of an 8.5-kb DNA fragment revealed three components of the ABC transporter, tliD, tliE, and tliF, upstream of the lipase gene, tliA. In addition, genes encoding a protease and a protease inhibitor were located upstream of tliDEF. tliDEF showed high similarity to ABC transporters of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease, Erwinia chrysanthemi protease, Serratia marcescens lipase, and Pseudomonas fluorescens CY091 protease. tliDEF and the lipase structural gene in a single operon were sufficient for E. coli cells to secrete the lipase. In addition, E. coli harboring the lipase gene secreted the lipase by complementation of tliDEF in a different plasmid. The ABC transporter of P. fluorescens was optimally functional at 20 and 25°C, while the ABC transporter, aprD, aprE, and aprF, of P. aeruginosa secreted the lipase irrespective of temperature between 20 and 37°C. These results demonstrated that the lipase is secreted by the P. fluorescens SIK W1 ABC transporter, which is organized as an operon with tliA, and that its secretory function is temperature dependent.

There are three major secretion pathways in gram-negative bacteria (57). The majority of the exoproteins are secreted via a two-step mechanism including a stopover in the periplasm (23). These proteins are translocated across the inner membrane in a signal sequence-dependent general export pathway (45). The subsequent translocation across the outer membrane requires 12 to 14 helper proteins (4, 23, 46). The second pathway used by several bacterial pathogens involves a transporter consisting of more than 20 secretion proteins (41). The protein is secreted through the inner and outer membranes simultaneously, bypassing the periplasm, and the secretion signals are located within 50 to 100 N-terminal residues (43). The last is an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) pathway, which also bypasses the periplasm (19). The protein is synthesized without an N-terminal signal sequence, and its secretion across two membranes involves three specific envelope proteins, ABC protein, membrane fusion protein and outer membrane protein. The secreted protein contains a C-terminal targeting signal containing several repeats of the consensus sequence GGXGXD (17, 22, 56) and an amphipathic α-helix (35, 50, 56).

Lipases of the Pseudomonas species are secreted by at least two different pathways (31). The two-step pathway, which requires at least 12 xcp gene products, is used by the signal sequence-containing lipases of P. aeruginosa (55) and P. glumae (25). These lipases also need molecular chaperones, which are located immediately downstream of the lipase structural genes of P. cepacia (33), P. glumae (24), and P. aeruginosa (13, 29, 30, 59). The lipase of P. fluorescens B52 was reported to be secreted by the ABC pathway mediated by the ABC transporter of P. aeruginosa alkaline protease (18), although the structural gene of the ABC transporter in P. fluorescens was not identified.

P. fluorescens SIK W1, a psychrotrophic bacterium, was found to secrete a thermostable lipase (7). We cloned this thermostable lipase (14) and expressed it in Escherichia coli, but it accumulated as inactive inclusion bodies in the cell (15). Sequence analysis showed that the lipase contained a C-terminal targeting signal sequence instead of an N-terminal signal sequence. Accordingly, the ABC transporter was assumed to be present in P. fluorescens SIK W1 because there is a specific ABC transporter for each protein secreted by the ABC pathway. Therefore, we searched for the ABC transporter gene in P. fluorescens SIK W1 and identified three components of the ABC transporter upstream of the lipase gene. In addition, the protease and protease inhibitor were located upstream of the three components. The ABC transporter of P. fluorescens was found to show temperature dependency in its secretory function when expressed in E. coli, and this suggested why P. fluorescens produces the lipase optimally at low temperature. There has been no report on the ABC transporter specific to lipase except in the Serratia marcescens Lip system (3), which is located separately from the lipase gene on the chromosome and secretes protease, lipase, and S-layer protein (34). In this paper, we report a new ABC transporter which is not only functionally specific for lipase but also structurally organized with the lipase gene as an operon on the chromosome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

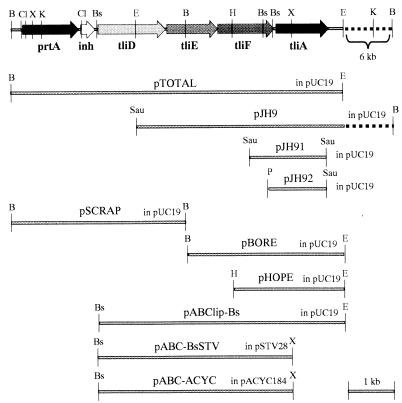

The plasmids used in this study are depicted in Fig. 1. pUC18 and pUC19 (60) were used as the cloning and subcloning vectors. Plasmid pACYC184 (11) and plasmids pSTV28 and pSTV29 (Takara, Japan) were used as low-copy-number plasmids possessing an oripP15A origin. Plasmid pAGS8 containing a 5-kb PvuII-SphI insert in pACYC184 expressing aprD, aprE, and aprF was donated by M. Murgier (18). P. fluorescens SIK W1 (8), the producer of thermostable lipase, was used for the cloning of six genes. E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) and JM109 (60) were used as recipients for plasmid transformation and the propagation of M13 phage. Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and nutrient broth were used for the growth of E. coli and P. fluorescens, respectively. The LAT plate (LB medium, 1.5% Bacto Agar, 0.5% tributylin) and the ROM agar plate (nutrient broth, 0.001% rhodamine-B, 1.0% olive oil, 1.5% Bacto Agar) were used to detect the lipase activity of the E. coli transformant and P. fluorescens, respectively. A skim milk agar plate (0.5% peptone, 5% skim milk, 1.5% Bacto Agar) was used for the detection of protease activity. When necessary, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (250 μg/ml) were included in the growth media.

FIG. 1.

Restriction endonuclease map of the various plasmids used. The relative positions of genes in P. fluorescens SIK W1 and restriction enzyme sites are depicted at the top. Inserts of subcloned plasmids are represented by the heavy line with pertinent enzyme sites at both ends. The names of subcloned plasmids and vectors used are given above the heavy line. Restriction enzymes: B, BamHI; Bs, BsrBI; Cl, ClaI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; P, PstI; Sau, Sau3AI; X, XhoI.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

General DNA manipulations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (47). For nucleotide sequencing, restriction fragments were subcloned into M13mp18 and M13mp19. DNA sequences were determined by cycle sequencing with the ABI PRISM BigDye primer cycle-sequencing kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). Synthetic oligonucleotides were used as primers to sequence both strands. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence data were analyzed by using DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering) and Vector NTI (Informax, Inc.). Homology searches were conducted with sequences in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database with the BLAST program (5). Multiple-sequence alignments were conducted with CLUSTALW (54). Potential transmembrane segments of the protein were predicted by TMHMM1.0 (48), and signal sequence was identified with SignalIP1.1 (44).

Southern hybridization and colony hybridization.

Total DNA of P. fluorescens was isolated as described previously (14) and digested with the appropriate restriction endonucleases. After gel electrophoresis, the DNA was transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) by capillary transfer. Labeling of probe DNA (digoxigenin system) was performed with a nonradioactive DNA-labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Hybridization was carried out at 42°C in a plastic bag with hybridization solution (5 × SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% [wt/vol] N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.02% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5% [wt/vol] blocking reagent, 50% [vol/vol] formamide). Colony hybridization was performed by the same method as Southern hybridization, except that the colonies on the plate were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to cell lysis and removal of cell debris as indicated in the manual provided by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

PCR on the genomic DNA.

The primers for the amplication of the 8.2-kb cloned genes were GF1 (5′-CGGCCTTGAACTTCTGAAAGTTGCTGGCGT-3′) and GR2 (5′-ACACAGCAACAATCGAAGTCGGGACATGCT-3′). The genomic DNA (100 ng) of P. fluorescens was used as the template, and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide was added to maximize duplex dissociation since the genomic DNA had a high G + C content. The PCR product was amplified in a thermocycler by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C, annealing at 68°C and elongation at 72°C for 6 min.

Immunoblot analysis of lipase.

Lipase was expressed by cultivating E. coli BL21 harboring plasmid pTTY2 (15). It was partially purified on a Q Sepharose fast-flow column as described previously (1). After electrophoresis, a slice containing the purified lipase was excised from the 9% polyacrylamide gel and anti-lipase serum was raised by injecting it into rabbits after homogenization (28). To detect the lipase in the cell and culture supernatant, cells were harvested and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 × g. Cell pellets were dissolved in SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (10.5% polyacrylamide). The cell supernatant was concentrated by precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or transferred onto a nitrocellulose sheet by electroblotting. The lipase was detected by immunoblotting with anti-lipase serum followed by binding of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G, and then signals were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham).

Assay of lipase activity.

Lipase activity was assayed qualitatively by spectrophotometry with p-nitrophenyl palmitate. The p-nitrophenyl palmitate was dissolved in acetonitrile to 10 mM. Ethanol and 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.5) were subsequently added to a final ratio of 1:4:95 (acetonitrile-ethnol-buffer). The reaction mixture was incubated at 45°C for 10 min, and the lipase activity was detected by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm. The lipase activity was estimated quantitatively by pH titration of fatty acids liberated from olive oil as described previously (37). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to release 1 μmol of fatty acids produced per min under the experimental conditions used.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the 8.5-kb fragment has been deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession no. AF083061.

RESULTS

Identification of the C-terminal targeting sequence.

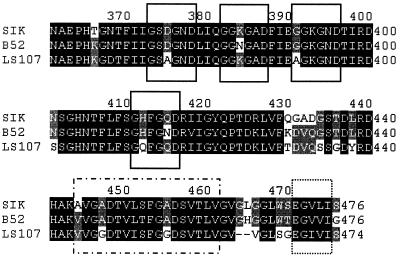

We previously cloned and sequenced the structural gene encoding a thermostable lipase from P. fluorescens SIK W1 (14). However, the lipase expressed in E. coli was not located in the culture broth or periplasm but was found within the cytoplasm in the form of inclusion bodies (15). The amino acid sequence analysis revealed that the lipase had a typical C-terminal targeting signal like the lipases of P. fluorescens B52 (18, 53) and LS107d2 (32) (Fig. 2). There were four GGXGXD consensus sequences and an 18-residue amphiphilic α-helix in the C terminus. In addition, an extreme C-terminal motif consisting of a negatively charged amino acid followed by 4 hydrophobic residues was identified as in the metalloproteases secreted by ABC transporters (26). We expected that the ABC transporter secreting the lipase was present in P. fluorescens SIK W1.

FIG. 2.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the C termini of lipases from P. fluorescens SIK W1 (SIK), P. fluorescens B52 (B52), and P. fluorescens LS107d2 (LS107). Identical residues in three different lipases are shaded in black, and identical residues in two different lipases are shaded in gray. Sequence alignment was performed with CLUSTALW (54), and gaps were introduced to maximize the homology. Position numbers for the sequences are given to the right. Solid boxes represent glycine-rich boxes; the dot-dash box represents a putative amphipathic α-helix; the dotted box represents the extreme C-terminal motif.

Identification of the secretory gene for P. fluorescens lipase.

There have been many reports that the ABC transporter is clustered with secreted proteins (17, 20, 27, 38, 51). Therefore, we attempted to find whether our lipase gene was clustered with any secretory gene. Previously, our group cloned the lipase gene by the shotgun method from P. fluorescens SIK W1 (14), obtaining pJH9 containing a 10.2-kb insert in pUC19 and two shortened plasmids from pJH9, pJH91 and pJH92, containing 2- and 1.2-kb inserts, respectively, in pUC19 (Fig. 1). First, lipase activity was tested on an LAT plate for E. coli harboring pJH9, pJH91, and pJH92. Large activity haloes were detected around the transformants harboring pJH9, while transformants harboring pJH91 or pJH92 showed small haloes. Although E. coli cells do not possess the secretion function for the lipase, E. coli cells carrying a high copy number of lipase genes accumulated a lot of lipase proteins in the cell and showed a lipase secretory phenotype by forming small haloes on the LAT plate. For this reason, the secretion of lipase was confirmed by estimating the lipase activity in a culture supernatant of E. coli containing each plasmid by the spectrophotometric method. Lipase activity of the culture supernatant was detected for E. coli containing pJH9 but not for E. coli containing pJH91 or pJH92. Therefore, we concluded that pJH9 contained a secretory gene in addition to the lipase gene.

Identification and sequencing of the ABC transporter.

In the course of the sequencing analysis, the secretory gene was found to be an ABC transporter, but the 5′ end was truncated in pJH9. Southern hybridization was used to find the truncated part. Chromosomal DNA of P. fluorescens was separately digested with HindIII, BamHI, and KpnI. The digested chromosomal DNA was hybridized with the probe that was complementary to the 1.3-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment of the pJH9. Hybridized bands were found in HindIII- and BamHI-digested chromosomal DNA (≥13 kb for HindIII and 4.5 kb for BamHI). The 4.5-kb BamHI fragments were eluted and ligated into BamHI-digested pUC19. The cloned plasmids were transformed into E. coli, and MacConkey agar plates were used for primary screening. Colony hybridization was used to select the transformant containing the desired recombinant plasmid. Two colonies hybridized with the probe which was used for Southern hybridization and were proved to harbor the same plasmid (pSCRAP). Gene mapping of pSCRAP revealed that the 3′ region of the insert overlapped with the 5′ region of the insert in pJH9. The genomic DNA sequence of the ABC transporter gene and its surrounding region (8.5 kb) revealed six open reading frames (ORF) on the same DNA strand. According to BLAST search, the six ORFs were predicted to encode protease, protease inhibitor, three components of ABC transporter, and thermostable lipase, and they were designated prtA, inh, tliD, tliE, tliF, and tliA, respectively. The genomic organization of the six-gene cluster was confirmed by performing PCR on the genomic DNA by using oligonucleotides hybridizing with the ends of the cloned fragment. The length of PCR product (8.2 kb) was exactly same as the length estimated from the sequence (data not shown).

Sequence analysis.

The first gene, prtA, encoded a protein of 477 amino acids (aa) (49.5 kDa). Sequence alignment showed that PrtA had high homology to metalloproteases of Erwinia chrysanthemi (58), P. aeruginosa (17), and P. fluorescens CY091 (40) (50, 60, and 77% identity, respectively). It was found to have a zinc metallopeptidase motif (TLTHEIGHTL) in the central part of the protein and four glycine-rich repeats (GGXGXD) close to the C terminus, implicated in calcium binding (10), cytolytic activity, and secretion (22). The second gene, inh, encoded a protein of 122 aa (12.9 kDa) which had similarity to protease inhibitors of E. chrysanthemi (58), P. aeruginosa (17), and P. fluorescens CY091 (40) (35, 38, and 83% identity, respectively). The protein contained a putative signal peptide composed of 25 aa. The third gene, tliD, encoded a protein (ABC protein) of 578 aa (62.5 kDa). The hydropathy profile of the amino acid sequence indicated that TliD lacked a signal sequence and had five or six highly hydrophobic domains corresponding to putative transmembrane segments in the N-terminal half. There was an ATP-binding consensus sequence (GXXGXGKS) in the central part. The fourth gene, tliE, encoded a protein (membrane fusion protein) of 433 aa (47.8 kDa), which was predicted to be located in the periplasm with the hydrophobic transmembrane domain in the N-terminal region and the N-terminal end pointing toward the cytoplasm. No signal peptide was found at the N terminus. The fifth gene tliF, encoded a protein (outer membrane protein) of 481 aa (53.3 kDa), which was found to be mostly hydrophilic from the hydrophobicity analysis and had a typical prokaryotic signal sequence with the most likely cleavage site between aa 17 and 18. All three components of the ABC transporter exhibited homology to the ABC transporter of E. coli alpha-hemolysin (21), E. chrysanthemi protease (38), P. aeruginosa alkaline protease (17), S. marcescens lipase (3), and P. fluorescens CY091 protease (40) (21 to 23, 42 to 54, 49 to 56, 41 to 55, and 35 to 95% identity, respectively). The sixth, tliA, which encodes a thermostable lipase (476 aa; 49.9 kDa), was sequenced and characterized previously (14). There were sequencing errors in our previous report of the lipase gene, and the updated sequence was deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession no. S77830. tliA and tliDEF was supposed to be organized as an operon because there was a putative promoter between inh and tliD.

Expression of the ABC transporter gene in E. coli.

To test whether the cloned ABC transporter could secrete protease or lipase, a 4-kb BamHI fragment of pSCRAP was inserted into the BamHI site of pBORE derived from pJH9, resulting in pTOTAL. pTOTAL contained all six genes (prtA, inh, tliD, tliE, tliF, and tliA) in the same orientation under the control of the lac promoter of pUC19. However, E. coli harboring pTOTAL showed neither protease nor lipase activity on the LAT plate or the skim milk agar plate. Also, no lipase was detected in the Western blot of the extract of cells containing pTOTAL, although the lipase accumulated in cells containing only the lipase gene (data not shown). We suspected that the failure to detect enzyme activity in E. coli resulted from poor expression of the Pseudomonas native promoter (9, 12) and presence of a long hairpin structure (ΔG = −28.6 kcal/mol) followed by a stretch of T residues, characteristic of a rho-independent transcriptional terminator immediately downstream of prtA (bp 1732 to 1755). To circumvent this problem, pABClip-Bs was constructed excluding the transcriptional terminator (Fig. 1), which contained the ABC transporter and lipase under the lac promoter. The E. coli harboring pABClip-Bs showed a large activity halo on the LAT plate and lipase activity in the culture supernatant.

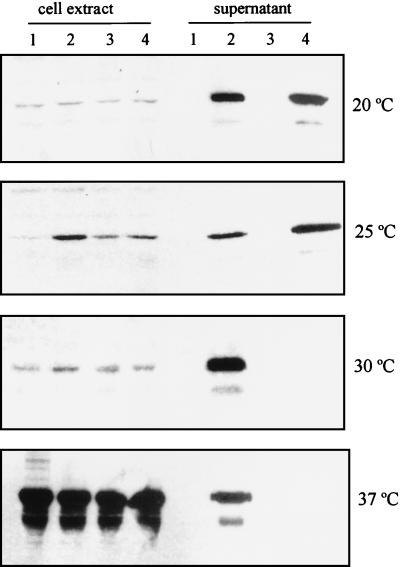

Expression of ABC transporter and lipase in dual plasmids at different temperatures.

Based on the results described above, it was clear that pABClip-Bs carried all the necessary genes for lipase secretion in E. coli. To check whether the ABC transporter in a different plasmid could complement the secretory function of E. coli harboring the lipase gene (tliA), a 5-kb BsrBI-XhoI fragment containing tliD, tliE, and tliF was subcloned into pACYC184 and pSTV28 to give pABC-ACYC and pABC-BsSTV under the control of the constitutive Cm promoter and inducible Lac promoter, respectively (Fig. 1). pHOPE containing the lipase in pUC19 was introduced into E. coli XL1-Blue together with pSTV29, pAGS8, pABC-BsSTV, or pABC-ACYC. Preliminary tests showed that E. coli harboring the lipase and ABC transporter gene did not secrete as much lipase as expected at 37°C. For this reason, E. coli carrying the various sets of dual plasmids were grown at different temperatures and the lipase activity of each culture supernatant was measured (Table 1). In addition, the lipase within the cell and in the extracellular medium was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 3). E. coli carrying pHOPE and pABC-ACYC secreted the lipase at 20 and 25°C but secreted only a very small amount of lipase at 30 and 37°C, whereas E. coli carrying pHOPE and pAGS8 containing the ABC transporter, aprD, aprE, and aprF of P. aeruginosa protease secreted the lipase at all the temperatures tested. pABC-BsSTV did not facilitate the secretion of the lipase despite isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction. E. coli carrying pHOPE and pABC-BsSTV showed the same pattern as E. coli carrying pHOPE and pSTV29, which was used as a negative control of the lipase-nonsecretory phenotype. As a result, E. coli harboring the lipase gene secreted about 19 U of lipase per ml to the extracellular medium by supplementing the ABC transporter gene of P. fluorescens or P. aeruginosa whereas the wild-type P. fluorescens SIK W1 secreted only 1.7 U of the lipase per ml after prolonged incubation for a week.

TABLE 1.

Secretion of thermostable lipase by E. coli XL1-Blue harboring various plasmids at different culture temperaturesa

| Plasmids | Extracellular lipase activity (U/ml)b at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20°C | 25°C | 30°C | 37°C | |

| pSTV29 + pHOPE | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| pAGS8 + pHOPE | 19.0 | 16.0 | 21.0 | 19.3 |

| pABC-BsSTV + pHOPE | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| pABC-ACYC + pHOPE | 19.1 | 19.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

E. coli XL1-Blue harboring various dual plasmids was grown at different temperatures in LB medium without induction. The cells were harvested when they reached an optical density at 600 nm of 4 for the 20, 25, and 30°C cultures and an optical density at 600 nm of 2.5 for the 37°C culture. Extracellular lipase activities of culture supernatants were estimated by the pH titration method.

Extracellular activity of P. fluorescens SIK W1 after prolonged incubation at 25°C was 1.7 U/ml.

FIG. 3.

Immunodetection of the lipase in cell extracts and culture supernatant of E. coli carrying various dual plasmids. E. coli XL1-Blue harboring dual plasmids was grown at different temperatures in LB medium without induction. The cells were harvested when they reached an optical density at 600 nm of 4 for the 20, 25, and 30°C cultures and an optical density at 600 nm of 2.5 for the 37°C culture. The cell extract and culture supernatant were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Cell extract of 20 μl (culture equivalent) and culture supernatant of 240 μl (culture equivalent) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by immunodetection. Lanes: 1, E. coli (pHOPE + pSTV29); 2, E. coli (pHOPE + pAGS8); 3, E. coli (pHOPE + pABC-BsSTV); 4, E. coli (pHOPE + pABC-ACYC).

DISCUSSION

P. fluorescens secretes thermostable lipase into the extracellular medium (8) via a signal sequence-independent pathway (ABC pathway) which is mediated by an ABC transporter. We report here the identification and expression of the ABC transporter specific for the lipase from P. fluorescens SIK W1. The three genes of the ABC transporter, tliD, tliE, and tliF, were identified upstream of the lipase gene, tliA. In addition, the protease and protease inhibitor genes, prtA and inh, respectively, were found upstream of tliDEF.

The deduced amino acid sequence of PrtA had four glycine-rich boxes as the C-terminal targeting signal of the TliA; therefore, the protease was also expected to be secreted by tliDEF. The protease activity was not detected in the E. coli strain harboring only prtA on the skim milk agar plate. We tried to express prtA by supplementing tliDEF or aprDEF of P. aeruginosa alkaline protease and found detectable protease activity on the skim milk plate. The ABC transporter was located between prtA and tliA as if it was specific to both protease and lipase. The ABC transporter of S. marcescens and P. aeruginosa can secrete both lipase and protease (2, 18), and the P. fluorescens CY091 ABC transporter, which is structurally similar to tliDEF, was reported to secrete the protease (40). Consequently, the ABC transporter of P. fluorescens was expected to secrete both protease and lipase. However, the presence of a transcriptional terminator downstream of prtA and a promoter immediately upstream of tliD suggested that the ABC transporter and lipase are structurally organized as an operon.

P. fluorescens lipase is quite different from those of other Pseudomonas strains in that it is considerably larger (about 480 aa, in contrast to about 285 aa for P. aeruginosa, P. alcaligenes, and P. fragi and about 320 aa for P. cepacia and P. glumae), contains no cystein residue, and contains no typical N-terminal signal sequence (31). Instead, it contains an export signal located at the C terminus, which is recognized by the ABC transporter. In particular, the lipase of P. fluorescens is different in its secretion mechanism from that of P. aeruginosa, which secretes the lipase in a sec-dependent pathway (31, 55). The genomic sequences of P. aeruginosa PAO1 were analyzed to find the genes corresponding to tliD, tliE, tliF, and tliA from P. fluorescens SIK W1 by performing a BLAST search against the P. aeruginosa assembled contigs at NCBI. There was no DNA sequence homologous to tliA, but there were two sequences homologous to tliDEF, one of which was aprDEF, specific for alkaline protease, and the other was the sequence which seemed to be the ABC transporter specific for and downstream of hasA (39). Consequently, there did not seem to be a similar organization in P. aeruginosa to the ABC transporter and lipase in P. fluorescens SIK W1.

In this study, the lipase expressed as inclusion bodies in E. coli was found to be secreted by ABC transporters of P. fluorescens and P. aeruginosa. The ABC transporter of P. fluorescens secreted lipase optimally at temperatures below 30°C, while that of P. aeruginosa secreted lipase irrespective of temperature (Table 1; Fig. 3). This was expected because P. fluorescens is a psychrotrophic bacterium growing optimally below 30°C whereas P. aeruginosa grows optimally at 37°C. It was not thought to be caused by transcriptional or translational control in the expression of tliD, tliE, and tliF, because the transcription of these was initiated from the Cm promoter and transcription and translation are usually more strongly activated at high temperature, as can be seen for the large lipase accumulation at 37°C (Fig. 3). Instead, it is presumed to be a functional or physical perturbation in either the lipid bilayer or ABC transporter at the temperature which is not optimal for the ABC transporter of P. fluorescens. Membrane proteins fulfill their role in a highly organized lipid bilayer which can change its fluidity and thickness according to temperature (16, 36, 49, 61). Therefore, we assumed that the ABC transporter of P. fluorescens was susceptible to structural changes of the ABC transporter itself or of the lipid bilayer at temperatures above 30°C and could not tolerate the changes, although the ABC transporter of P. aeruginosa could tolerate them. Optimal production of lipases is obtained by cultivating the cell at low temperatures in P. fluorescens (6, 42, 52). This phenomenon is explained if the ABC transporter of psychrotrophic bacteria is activated to secrete protein at low temperature but loses its secretory activity at the higher temperature.

In this study, we identified an ABC transporter of P. fluorescens lipase which is secreted in a signal peptide-independent pathway. This ABC transporter had characteristics in common with previously published ABC transporters but also showed a temperature dependency in its secretory function. The structural differences between the P. fluorescens ABC transporter and other ABC transporters should be elucidated to better understand the temperature dependency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge D. Y. Yum, D. H. Hahm, and T. Ahn for reading the manuscript and providing helpful discussion. We also thank M. Murgier for providing pAGS8.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn J H, Lee Y P, Rhee J S. Investigation of refolding condition for Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase by response surface methodology. J Biotechnol. 1997;54:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)01693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akatsuka H, Binet R, Kawai E, Wandersman C, Omori K. Lipase secretion by bacterial hybrid ATP-binding cassette exporters: molecular recognition of the LipBCD, PrtDEF, and HasDEF exporters. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4754–4760. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4754-4760.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akatsuka H, Kawai E, Omori K, Shibatani T. The three genes lipB, lipC, and lipD involved in the extracellular secretion of the Serratia marcescens lipase which lacks an N-terminal signal peptide. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6381–6389. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6381-6389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akrim M, Bally M, Ball G, Tommassen J, Teerink H, Filloux A, Lazdunski A. Xcp-mediated protein secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of two additional genes and evidence for regulation of xcp gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:431–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb02674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson R E. Microbial lipolysis at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:36–40. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.1.36-40.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson R E, Danielsson G, Hedlund C B, Svensson G. Effect of a heat-resistant microbial lipase on flavor of ultra-high-temperature sterilized milk. J Dairy Sci. 1981;64:375–379. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson R E, Hedlund C B, Jonsson U. Thermal inactivation of a heat-resistant lipase produced by the psychotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Dairy Sci. 1979;62:361–367. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(79)83252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagdasarian M, Timmis K N. Host:vector systems for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1982;96:47–67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68315-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehm D F, Welch R A, Snyder I S. Domains of Escherichia coli hemolysin (HlyA) involved in binding of calcium and erythrocyte membranes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1959–1964. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1959-1964.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang A C, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S T, Jordan E M, Wilson R B, Draper R K, Clowes R C. Transcription and expression of the exotoxin A gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3081–3091. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-11-3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chihara-Siomi M, Yoshikawa K, Oshima-Hirayama N, Yamamoto K, Sogabe Y, Nakatani T, Nishioka T, Oda J. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of lipase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;296:505–513. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90604-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung G H, Lee Y P, Jeohn G H, Yoo O J, Rhee J S. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of thermostable lipase gene from Pseudomonas fluorescens SIK W1. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:2359–2365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung G H, Lee Y P, Yoo O J, Rhee J S. Overexpression of a thermostable lipase gene from Pseudomonas fluorescens in E. coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:237–241. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornea R L, Thomas D D. Effects of membrane thickness on the molecular dynamics and enzymatic activity of reconstituted Ca-ATPase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2912–2920. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duong F, Lazdunski A, Cami B, Murgier M. Sequence of a cluster of genes controlling synthesis and secretion of alkaline protease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationships to other secretory pathways. Gene. 1992;121:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90160-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duong F, Soscia C, Lazdunski A, Murgier M. The Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase has a C-terminal secretion signal and is secreted by a three-component bacterial ABC-exporter system. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fath M J, Kolter R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:995–1017. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.995-1017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felmlee T, Pellett S, Lee E Y, Welch R A. Escherichia coli hemolysin is released extracellularly without cleavage of a signal peptide. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:88–93. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.88-93.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felmlee T, Pellett S, Welch R A. Nucleotide sequence of an Escherichia coli chromosomal hemolysin. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:94–105. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.94-105.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felmlee T, Welch R A. Alterations of amino acid repeats in the Escherichia coli hemolysin affect cytolytic activity and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filloux A, Bally M, Ball G, Akrim M, Tommassen J, Lazdunski A. Protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria: transport across the outer membrane involves common mechanisms in different bacteria. EMBO J. 1990;9:4323–4329. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frenken L G, Bos J W, Visser C, Muller W, Tommassen J, Verrips C T. An accessory gene, lipB, required for the production of active Pseudomonas glumae lipase. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:579–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frenken L G, de Groot A, Tommassen J, Verrips C T. Role of the lipB gene product in the folding of the secreted lipase of Pseudomonas glumae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:591–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghigo J M, Wandersman C. A carboxyl-terminal four-amino acid motif is required for secretion of the metalloprotease PrtG through the Erwinia chrysanthemi protease secretion pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8979–8985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser P, Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Ullmann A, Danchin A. Secretion of cyclolysin, the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase-haemolysin bifunctional protein of Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J. 1988;7:3997–4004. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harlow E, Lane D. Immunizations. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ihara F, Okamoto I, Akao K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Lipase modulator protein (LimL) of Pseudomonas sp. strain 109. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1254–1258. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1254-1258.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iizumi T, Nakamura K, Shimada Y, Sugihara A, Tominaga Y, Fukase T. Cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of a lipase and its activator genes from Pseudomonas sp. KWI-56. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:2349–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaeger K E, Ransac S, Dijkstra B W, Colson C, van Heuvel M, Misset O. Bacterial lipases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;15:29–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson L A, Beacham I R, MacRae I C, Free M L. Degradation of triglycerides by a pseudomonad isolated from milk: molecular analysis of a lipase-encoding gene and its expression in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1776–1779. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1776-1779.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorgensen S, Skov K W, Diderichsen B. Cloning, sequence, and expression of a lipase gene from Pseudomonas cepacia: lipase production in heterologous hosts requires two Pseudomonas genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:559–567. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.559-567.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawai E, Akatsuka H, Idei A, Shibatani T, Omori K. Serratia marcescens S-layer protein is secreted extracellularly via an ATP-binding cassette exporter, the Lip system. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:941–952. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenny B, Taylor S, Holland I B. Identification of individual amino acids required for secretion within the haemolysin (HlyA) C-terminal targeting region. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1477–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killian J A, Salemink I, de Planque M R, Lindblom G, Koeppe R E, Jr, Greathouse D V. Induction of nonbilayer structures in diacylphosphatidylcholine model membranes by transmembrane alpha-helical peptides: importance of hydrophobic mismatch and proposed role of tryptophans. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1037–1045. doi: 10.1021/bi9519258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee Y P, Chung G H, Rhee J S. Purification and characterization of Pseudomonas fluorescens SIK W1 lipase expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1169:156–164. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90200-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Letoffe S, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protease secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi: the specific secretion functions are analogous to those of Escherichia coli alpha-haemolysin. EMBO J. 1990;9:1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Letoffe S, Redeker V, Wandersman C. Isolation and characterization of an extracellular haem-binding protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa that shares function and sequence similarities with the Serratia marcescens HasA haemophore. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1223–1234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao C H, McCallus D E. Biochemical and genetic characterization of an extracellular protease from Pseudomonas fluorescens CY091. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:914–921. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.914-921.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menard R, Sansonetti P, Parsot C. The secretion of the Shigella flexneri Ipa invasins is activated by epithelial cells and controlled by IpaB and IpaD. EMBO J. 1994;13:5293–5302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merieau A, Gugi B, Guespin-Michel J F, Orange N. Temperature regulation of lipase secretion by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain MFO. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;39:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michiels T, Cornelis G R. Secretion of hybrid proteins by the Yersinia Yop export system. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1677–1685. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1677-1685.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pugsley A P, Possot O. The general secretory pathway of Klebsiella oxytoca: no evidence for relocalization or assembly of pilin-like PulG protein into a multiprotein complex. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:665–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonnhammer E L L, Heijne G, Krogh A. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squier T C, Bigelow D J, Thomas D D. Lipid fluidity directly modulates the overall protein rotational mobility of the Ca-ATPase in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9178–9186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanley P, Koronakis V, Hughes C. Mutational analysis supports a role for multiple structural features in the C-terminal secretion signal of Escherichia coli haemolysin. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2391–2403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strathdee C A, Lo R Y. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and characterization of genes encoding the secretion function of the Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin determinant. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:916–928. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.916-928.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan K H, Gill C O. Effect of culture conditions on batch growth of Pseudomonas fluorescens on olive oil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1985;23:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan Y, Miller K J. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of a lipase gene from Pseudomonas fluorescens B52. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1402–1407. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1402-1407.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tommassen J, Filloux A, Bally M, Murgier M, Lazdunski A. Protein secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;9:73–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90336-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wandersman C. Secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. Trends Genet. 1992;8:317–322. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wandersman C. Secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wandersman C, Delepelaire P, Letoffe S, Schwartz M. Characterization of Erwinia chrysanthemi extracellular proteases: cloning and expression of the protease genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5046–5053. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5046-5053.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wohlfarth S, Hoesche C, Strunk C, Winkler U K. Molecular genetics of the extracellular lipase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1325–1335. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y P, Lewis R N, Hodges R S, McElhaney R N. Interaction of a peptide model of a hydrophobic transmembrane alpha-helical segment of a membrane protein with phosphatidylcholine bilayers: differential scanning calorimetric and FTIR spectroscopic studies. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11579–11588. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]