Abstract

Objective

This study examines the potential benefit of an interactive counselling program via a mobile application (app), which can instantly provide patients with the necessary information and correct response regarding their condition.

Methods

We designed a free ‘Ureteric Stent Interactive Program’ for patients receiving ureterorenoscopic lithotripsy and provided the program to interested patients. Patient data were collected from medical records and depending on whether patients used our program, they were divided into two groups: ‘program-user’ and ‘non-user’. The differences between the groups were analysed using Fisher’s exact tests.

Results

Of the 70 patients, 50 elected to use the program. The program-user group was significantly younger (<60 years: 74% vs 15%, P<0.001) and had higher education levels (40% vs 5%, P = 0.004). All 50 patients in the program-user group reported being satisfied (32%) or very satisfied (68%) with the program. Patients over 60 years were significantly more satisfied with program (35.5% vs 6.3%, P = 0.04).

Conclusions

Younger patients with high education levels were more likely to use the app and improve their health knowledge. Using the program resulted in high satisfaction, especially among older patients. This study demonstrates the benefits of interactive application for educating patients regarding their health.

Keywords: Double-j ureteric stent, mobile communication application, patient education, tele-medicine, ureterorenoscopic lithotripsy

Introduction

Patient education is key not only for knowledge transfer, but also to empower patients in disease management and decision making. 1 Good patient education is especially paramount for older adults, as it can improve treatment adherence, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality.2,3 Face-to-face communication is currently the primary modality for patient education in hospitals. However, even when physicians are sufficiently trained to teach patients in an adaptive way, they might have time constraints in communicating and providing necessary information and instructions.

A mobile application (hereafter referred to as ‘app’), directed specifically at the actual disease, might have a positive effect on reminding patients’ about instructions and using given information. Patients might also be unable to correctly recall information provided by physicians when complications are encountered, resulting in unnecessary hospital visits or exacerbation of the abovementioned complications. Therefore, the development of novel methods to improve patient–physician communication and facilitate patient education is essential.

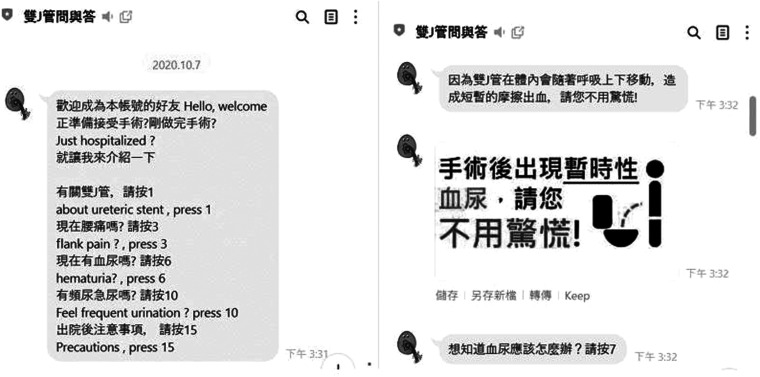

A double-J ureteric stent (DJ) is a popular medical device in urology. It is used to prevent or treat obstructions of the ureters, especially after endoscopic ureteral surgeries such as a ureterorenoscopic lithotripsy (URSL). However, indwelling DJs can also lead to intolerable symptoms, including haematuria, frequency or urgency of urination, dysuria and flank pain.4,5 These symptoms may not appear immediately after placement, and patients may experience discomfort several days after discharge. Forgotten ureteral stents and their encrustation are also serious issues and may cause severe complications if left unattended. 6 Therefore, patient education on self-care related to indwelling DJs and self-management of DJ-related symptoms is crucial for preventing morbidity. Although face-to-face education of DJ-related issues before discharge and telephonic follow-up by medical staff are routine urological practices in Taiwan, patients frequently forget this information, and a real-time response to their complaints or queries is warranted. With the increased significance of remote medical service during the COVID-19 pandemic, an app named ‘Urostentz’ was developed to provide guidance and personalized remote healthcare for patients with ureteral stents after surgery.7,8 Given the lack of development funds and engineering techniques, we intended to identify a route to developing remote medical service for our country. We found that several communication apps allow real-time person-to-person contact through smartphones. Line is a popular mobile app in Japan, Taiwan and Thailand; besides communication, it provides additional services such as third-party payment and advertisement for companies. It also offers modules for designing online interactive programs that can automatically reply and interact with users for customer services. 9 As limited version is free of charge, it was a suitable tool to design our program. We developed a ‘Ureteric Stent Interactive Counselling Program’ using the Line app (Figure 1). In the app, patients could easily access the program by scanning a QR code on their smartphones before their discharge. Through this interactive counselling program, they could ask and receive answers to questions related to DJs – such as the symptoms related to indwelling DJs, the self-care as well as management of DJ-related symptoms – via text. We evaluated patients’ satisfaction with the app, its influence on their subjective experience of DJ-related symptoms and noticed the potential benefit of this tool for patient education. A retrospective study collecting data from patients’ medical chart was then conducted.

Figure 1.

Example of a ‘ureteric stent interactive counselling program’ line application.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taipei City Hospital (IRB number: TCHIRB-11001011-E) on 2020/12/02. The IRB agreed that written informed consent from the patients were not required, owing to the retrospective nature of this study and the lack of identifiable patient information. Patients who received indwelling DJs after URSL between 1 August 2019 and 30 November 2019, were included in our study. We excluded patients aged < 20 years, those who did not return to our clinic, those who planned to have ureteral stenting more than one month, and those with incomplete records in the medical chart. Prior to their discharge, patients received face-to-face education from the urologists or other medical staff about the symptoms associated with DJs and their self-care at home. After the education sessions, we asked patients whether they understood all the information, to ensure they had no questions. Information and access to the Ureteric Stent Interactive Counselling Program were then provided by the medical staff. Based on their personal preference, patients had the choice of using the additional counselling program in Line. Telephonic follow-up would be performed once after discharge, and outpatient face-to-face follow-up would be arranged for all patients one to two weeks after discharge. The ureteric stents were removed via cystoscopy after the outpatient visit. Just before removal, patients were asked to rate their subjective experience of DJ-related symptom severity. The program-users were also asked to rate their satisfaction with the interactive counselling program on a five-point scale ranging from 1, indicating ‘very unsatisfied’ to 5, ‘very satisfied’. These data were retrospectively collected from our clinic medical records.

Statistical analysis

All data were collected from chart review. We divided patients into two groups, based on the mode of patient education for DJ-related information: the ‘non-user group’, who received only face-to-face education by medical staff, and the ‘program-user group’, who received both face-to-face education and program interaction. We used Fisher's exact tests to examine the between-group differences in demographic characteristics, DJ-related symptom severity, as well as factors associated with patient satisfaction in the program-user group. We performed logistic analyses, including multivariate analysis with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to examine factors related to gross haematuria. A P-value below 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance.

Results

A total of 92 patients had URSL and DJ stenting during the study period, among whom 22 patients were excluded. A total of 70 patients were included in our sample, of whom 50 received face-to-face education by medical staff as well as program interaction with the program after discharge. The remaining 20 patients received only routine education by the medical staff during their hospitalization. Patients’ demographic data are shown in Table 1. A significant number of patients in the program-user group (52.8 ± 15.6 years) were younger than those in the non-user group (66.0 ± 7.6 years, P<0.001), had higher education levels (40% vs 5%, P = 0.004), and had more severe gross haematuria than did those in the non-user group (66% vs 15%, P<0.001). No significant differences were observed in terms of other symptoms. In the multivariate analysis, the severity of gross haematuria was significantly associated with ages younger than 60 years (OR: 6.704, P = 0.003, 95% CI: 1.898–23.673) and the use of the interactive counselling program (OR: 6.63, P = 0.02, 95% CI: 1.374–31.989). All 50 patients in the program-user group reported being satisfied (score 4, 32%) or very satisfied (score 5, 68%) with the tool. No users reported feeling neutral (score 3), unsatisfied (score 2), or very unsatisfied (score 1) with the interactive counselling program. Significantly, older patients reported being very satisfied with the interactive counselling program (57.2 ± 14.5 years, very satisfied vs 46.9 ± 15.5 years, satisfied; P = 0.02). No statistical differences were observed in terms of education level, severity of other DJ-associated symptoms, and recognition of the necessity for DJ removal (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparative demographic characteristics and symptomatology of the two education groups (N = 70).

| Non-user group | Program-user group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 20) | (N = 50) | P-value | |

| Age | 52.8 ± 15.6 | 66.0 ± 7.6 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 11 (55%) | 37 (74%) | 0.16 |

| Education level above college | 1 (5%) | 20 (40%) | 0.004 |

| Severe ureteric stent-related symptoms | |||

| Flank pain | 6 (30%) | 18 (36%) | 0.63 |

| Gross haematuria | 3 (15%) | 33 (66%) | <0.001 |

| Frequency | 10 (50%) | 19 (38%) | 0.36 |

| Urgency | 7 (35%) | 7 (14%) | 0.09 |

| Difficulty in voiding | 1 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 0.99 |

| Unawareness of the necessity of stent removal | 3 (15%) | 2 (4%) | 0.14 |

Table 2.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction with the interactive counselling program according to demographic characteristics and symptomatology (N = 50).

| Satisfied (score 4) | Very satisfied (score 5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 16) | (N = 34) | P-value | |

| Age | 46.9 ± 15.5 | 57.2 ± 14.5 | 0.02 |

| Male sex | 14 (87%) | 23 (68%) | 0.18 |

| Education level above college | 5 (31%) | 15 (44%) | 0.39 |

| Severe ureteric stent-related symptoms | |||

| Flank pain | 8 (50%) | 10 (29%) | 0.16 |

| Gross haematuria | 12 (75%) | 21 (62%) | 0.36 |

| Frequency | 8 (50%) | 11 (32%) | 0.23 |

| Urgency | 1 (6%) | 6 (18%) | 0.41 |

| Difficulty in voiding | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0.99 |

| Unawareness of the necessity of stent removal | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0.54 |

Discussion

In this study, we found that younger patients with a higher education level were more likely to select this novel communication tool. This confirms the results of other studies, which state that people with a higher education level are more likely to retrieve information using smartphones 10 and typically search for information on the Internet, whereas older adults generally rely on simpler and more traditional search strategies, such as the newspaper or television programs.11,12 All the patients using this counselling program after discharge reported being satisfied and very satisfied with this simple conversation agent. Customization of these existing free modules in communication apps for patient education would be a cost-effective approach to improving patient understanding and satisfaction. Moreover, we also observed that older patients were more satisfied with the use of the interactive counselling program, similar to the findings of another study by Chaix et al. 13 Other studies show that patient education among older people is time-consuming,3,14 but older patients can understand the medical staff’s recommendations, provided they have sufficient time. 15 Previous studies revealed older people were at greater risk of forgetting ureteral stents.16,17 Application of this interactive counselling program provided older adults with more time to understand the information provided by the medical staff, even after discharge, which is advantageous and time-effective for both patients and medical staff.

Interestingly, we noticed that younger patients and those who used the interactive counselling program reported more severe gross haematuria. There were no differences in other reported symptoms, including frequency and urgency of urination, difficulty in voiding and flank pain. Patients with indwelling DJs were asked to increase their water intake and to avoid vigorous activities, which would alleviate the severity of gross haematuria.18,19 The compliance of younger patients is generally poor, and they are more likely to engage in inadequate water consumption 20 and participate in more daily activities than older adults; this could explain the more severe gross haematuria among younger patients. Another explanation is that symptoms such as urgency or flank pain are easily detected, and patients are told to be aware of the occurrence of gross haematuria and be mindful about observing the colour of their urine. People often neglect gross haematuria because it does not cause discomfort. As acquisition of information from the medical staff or from the interactive counselling program should not have affected the severity of gross haematuria, we speculate that the difference may be because the patients in the program-user group had more access to information and were therefore more aware of the symptoms of gross haematuria.

The interactive counselling program failed to have an impact on the awareness of the need for DJ removal in the present study. This is different from a previous study by Wang et al., which shows the efficacy of mobile social network apps in reminding patients of DJ removal. 21 One explanation is the small sample size in our study. The other probable reason is the design of the interactive counselling program. Because it was interactive, the patients would log a query using the program only when they had symptoms or discomfort. Questions related to DJ removal would not be asked, and therefore, patients were less likely to obtain the associated information. One can optimize the interactive counselling program further by sending an automatic reminder about the necessity of DJ stent removal upon interaction with the counselling program.

Patient education and effective communication between physicians and patients are key for a healthy patient–physician relationship, which can help reduce morbidity and avoid potential medical dispute claims. 1 With the application of Internet communication technology in medical practice, physicians and other medical personnel can expand on traditional in-hospital, and use face-to-face communication to better educate their patients, even after discharge with appropriate monitoring or contact.13,22 Our interactive application has been in use since 2019, preceding the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the pandemic, remote medical service and effective communication between medical staff and patients became even more critical. Many digital applications were developed and used for telemedicine. A study by BM Zeeshan Hameed et al. confirmed the effective communication for ureteral stent issue provided by the Urostentz smartphone app. 7 A study by Simone Morselli et al. also demonstrated the benefit of remote communication using MyBPHCare, an app for mobile phones. 23 However, conversational agents in health care are text-based, artificial intelligence-driven, and smartphone-delivered. These apps usually need professional engineering technique to develop and are usually designed for a single issue/disease. Thus, there is an urgent need to evaluate the diverse health care conversational agents’ format, 24 such as our interactive counselling program, also known as chatbot module in Line. Previous studies show that chatbots can help patients better understand their disease, improve treatment adherence, decrease the workload of medical staff and reduce the risk of hospitalization or emergency department visits.21,25–28 This type of interactive program in a mobile communication app does not require extra equipment and does not usually add to existing medical expenses. By using a free module provided by a mobile communication app, medical staff can design interactive counselling programs that are useful and well received by patients. Different interactive counselling programs can be built for different medical conditions at no additional cost. Further, we believe that this type of patient education is suitable for countries with high rates of smartphone use, such as Taiwan. 29

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective observational study, rather than a randomized controlled trial; therefore, there may be some selection and recall bias, which could potentially impact the reporting of the severity of DJ-related symptoms between program-users and non-users. Moreover, question-order bias may exist, as this study did not use a validated questionnaire to evaluate the symptoms associated with indwelling DJ. A further prospective randomized trial applying a validated questionnaire, such as the Ureteral Stent Symptoms Questionnaire, may mitigate these biases and help us to analyse how patients feel and whether they prefer an additional app-based program for health education or not. Second, the number of cases was limited, and our results failed to show an association with some parameters – such as awareness of the necessity of DJ removal with the use of the interactive counselling program. Third, the program in this study was designed using traditional Chinese language. Patients who could not read or type in traditional Chinese were unable to use it. Therefore, a potential culture bias may also exist if we do the translation without validation. Nevertheless, we believe that because of the simplicity and the low cost of developing the interactive counselling program based on free modules in communication apps, the same concept could be applied to other diseases and be used by patients in other countries speaking different languages. Fourth, there was a lack of organization overseeing the communication between the patients and the interactive counselling program. The program automatically responded to the keywords in the patients’ questions. Therefore, we used the program to emphasize the need to visit the hospital if discomfort persisted or even increased after following the suggestions supplied by the program. Fifth, there was no standardized format of DJ-related information provided by an individual urologist or medical staff member. This is a potential bias. However, every urologist or medical staff member in our hospital would confirm the patients’ understanding after face-to-face education before discharge. Sixth, this interactive counselling program was designed based on the free modules provided by the Line app on smartphones and would not be useful in areas where the rates of smartphone use are not high or where Line is not the primary communication app. Nonetheless, the concept of the present study can be applied to other areas and countries. Other popular communication apps, such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, Viber and Telegram, provide similar interactive program services to their users through modules. Customization of these existing free modules to design an interactive counselling program for patient education would be a cost-effective approach to improve patient understanding and satisfaction, especially among older patients. Further prospective randomized controlled trials with a large sample size are warranted to determine whether the free interactive counselling program in mobile communication apps could decrease the workload of medical staff, post-operative emergency room visits and rate of forgotten DJs in patients with indwelling DJs after URSL.

Conclusions

The development of an interactive counselling program based on the free module in a mobile communication app is readily available for medical staff from different countries without extra cost, maintenance fee or equipment. The use of this interactive counselling program in a mobile communication app could result in high satisfaction, especially among older patients, because it takes more time for them to understand such educational information. Younger patients with higher education levels were more likely to adopt this new form of communication, which aided in improving their knowledge about DJ-associated symptoms, especially gross haematuria.

Practical implications and future scope

Our study findings present our concept and show that interactive counselling program developed from the free module of communication app is feasible and beneficial for health education. Without any extra fees or equipment, it could provide a cost-effective way of improving remote patient education and satisfaction, especially during the pandemic. This model of free chatbot module application to create an interactive counselling program can be used not only in urology but in other medical specialties as well, in situations where real-time responses to patients’ queries and constant education is mandatory. In the future, we will develop more interactive counselling programs focused on different urological diseases or conditions with the free module in Line. We will also promote this concept for other medical specialties. A more thorough prospective randomized controlled trial using a validated questionnaire, objective evaluation and larger sample size will be initiated to investigate the potential benefits and interactive possibilities of the application for medical education.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the editors and staff from Editage for the English language editing. We also thank SH Lin, our research assistant for assisting with data collection and patient connection.

Footnotes

Contributorship: Tzu-Yu Chuang: conceptualization, investigation. Yi-Chun Chiu: conceptualization, software. Chang-Chi Chang: conceptualization, software, investigation. Weiming Cheng: conceptualization, software, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review & editing. Chia-Heng Liao: investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft. Yu-Hua Fan: investigation. Chia-Chi Chi: investigation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Guarantor: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: Chia-Heng Liao https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4346-365X

References

- 1.Stenberg U, Vagan A, Flink M, et al. Health economic evaluations of patient education interventions a scoping review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 2018; 101: 1006–1035. 2018/02/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter WB, McKenna M, Martin ML, et al. Health education: special issues for older adults. Patient Educ Couns 1989; 13: 117–131. 1989/03/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kececi A, Bulduk S. Health education for the elderly. Geriatrics. 2012, pp.153.

- 4.Joshi HB, Newns N, Stainthorpe A, et al. Ureteral stent symptom questionnaire: development and validation of a multidimensional quality of life measure. J Urol 2003; 169: 1060–1064. 2003/02/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyaoka R, Monga M. Ureteral stent discomfort: etiology and management. Indian J Urol 2009; 25: 455–460. 2009/12/04. DOI: 10.4103/0970-1591.57910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juliebø-Jones P, Pietropaolo A, Æsøy MS, et al. Endourological management of encrusted ureteral stents: an up-to-date guide and treatment algorithm on behalf of the European Association of Urology Young Academic Urology Urolithiasis Group. Cent European J Urol 2021; 74: 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hameed BZ, Shah M, Naik N, et al. Use of ureteric stent related mobile phone application (UROSTENTZ App) in COVID-19 for improving patient communication and safety: a prospective pilot study from a university hospital. Cent European J Urol 2021; 74: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hameed B, Shah MJ, Naik N, et al. Are technology-driven mobile phone applications (Apps) the new currency for digital stent registries and patient communication: prospective outcomes using urostentz app. Adv Urol 2021; 2021: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LINE Bot Designer. https://developers.line.biz/en/services/bot-designer/ (2014, accessed 03/08 2019).

- 10.Bomhold CR. Educational use of smart phone technology: a survey of mobile phone application use by undergraduate university students. Program 2013; 47: 424–436. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huvila I, Moll J, Enwald H, et al. Age-related differences in seeking clarification to understand medical record information. In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9–11 October: Part 2 Information Research, 24(1), paper isic1834 2019.

- 12.Xing Z, Yuan X, Vizer LM. The Age-related differences in web information search process. ArXiv 2020; abs/2010.13352.

- 13.Chaix B, Bibault JE, Pienkowski A, et al. When chatbots meet patients: one-year prospective study of conversations between patients with breast cancer and a chatbot. JMIR Cancer 2019; 5: e12856. 2019/05/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rojda C, George NM. The effect of education and literacy levels on health outcomes of the elderly. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners (JNP) 2009; 5: 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung A, Chi I, Lui YH. A cross-cultural study in older adults’ learning experience. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr 2006; 1: 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin T-F, Lin W-R, Chen M, et al. The risk factors and complications of forgotten double-J stents: a single-center experience. J Chin Med Assoc 2019; 82: 767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng W, Chiu Y-C, Fan Y-H, et al. Risks of forgotten double-J ureteric stents after ureterorenoscopic lithotripsy in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abt D, Warzinek E, Schmid HP, et al. Influence of patient education on morbidity caused by ureteral stents. Int J Urol 2015; 22: 679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosio A, Destefanis PG, Alessandria E, et al. Impact of double J ureteral stents on general health, work performance and sexual matters. In: 2nd Meeting of the EAU Section of Urolithiasis (EULIS) 2013, pp.70–71.

- 20.Rosinger AY, Herrick KA, Wutich AY, et al. Disparities in plain, tap and bottled water consumption among US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2014. Public Health Nutr 2018; 21: 1455–1464. 2018/02/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Xu M, Li W, et al. It is efficient to monitor the status of implanted ureteral stent using a mobile social networking service application. Urolithiasis 2020; 48: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramachandra M, Mosayyebi A, Carugo D, et al. Strategies to improve patient outcomes and qol: current complications of the design and placements of ureteric stents. Res Rep Urol 2020; 12: 303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morselli S, Liaci A, Nicoletti R, et al. The use of a novel smartphone app for monitoring male luts treatment during the COVID-19 outbreak. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2020; 23: 724–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Car L T, Dhinagaran DA, Kyaw BM, et al. Conversational agents in health care: scoping review and conceptual analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e17158. 2020/08/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avila-Tomas JF, Olano-Espinosa E, Minue-Lorenzo C, et al. Effectiveness of a chat-bot for the adult population to quit smoking: protocol of a pragmatic clinical trial in primary care (Dejal@). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019; 19: 249. 2019/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mierzwa S, Souidi S, Conroy T, et al. On the potential, feasibility, and effectiveness of chat bots in public health research going forward. Online J Public Health Inform 2019; 11: e4. 2019/10/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tielman ML, Neerincx MA, Pagliari C, et al. Considering patient safety in autonomous e-mental health systems - detecting risk situations and referring patients back to human care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019; 19: 47. 2019/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milne-Ives M, de Cock C, Lim E, et al. The effectiveness of artificial intelligence conversational agents in health care: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e20346. 2020/10/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.York S, Poynter R. Global mobile market research in 2017. Mobile Research. Springer, 2018, pp.1–14.