Abstract

Background:

According to the literature analysis, the majority of the studies focused primarily on public health institutions. Although assessing the compliance of healthcare workers in private and public institutions would give comprehensive evidence on existing problems and appropriate prevention method, as a result, research on adherence to standard precautions are still required. Rely on existing research, to the best of the investigator’s knowledge, compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town has not been assessed. Therefore, this study will contribute to narrowing these gaps and determining the scope of problems with standard precautions.

Methods:

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among 442 healthcare workers working in hospitals from June 10 to 30, 2021. A stratified random sampling technique was employed to select the study participants. Pre-tested and structured questionnaires and an observational checklist were used to collect the required data. The data were entered into EpiData and analyzed using SPSS version 22. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were used to assess the association between independent and outcome variables. Odd ratios at 95% CI were used to measure the strength of the association between the outcome and explanatory variables. Finally, a P-value of <.05 was considered as a cut-off point for statistical significance.

Results:

Of the 442 healthcare workers who participated in the study, 41% were compliant with standard precautions. Furthermore, 68.1% and 51.8% of the respondents had good knowledge and a positive attitude toward infection prevention, respectively. Consistent water supply availability (AOR = 1.92 and 95% CI = 1.63, 6.27), and access to infection prevention guidelines (AOR = 1.73 and 95% CI = 1.08, 2.77), and availability of personal protective equipment (AOR = 2.32 and 95% CI = 1.35, 3.98) were some of the factors significantly associated with health care workers’ compliance.

Conclusions:

The current study found that only about two-fifths of the healthcare workers complied with standard precautions. The study suggests that there is a significant risk of developing an infection. Therefore, the concerned organizations; Bahir Dar Zonal Health Office, and respective sectors including Amhara Regional Health Office and the Federal Ministry of Health must take appropriate measures to improve the implementation of safety practices.

Keywords: Compliance, healthcare workers, standard precautions, infection prevention and control, health facility

Introduction

Health care workers (HCWs) are more susceptible to contracting infections due to the nature of the critical care environment and frequently close contact with patients, invasive procedures expose them to body fluids and infectious microorganisms.1,2 The most important circumstance that HCWs are a risky group in any healthcare setting for Health Acquired Infections (HAIs).3,4 Infections that people contract while seeking treatment in medical facilities are known as “ healthcare-associated infections” (HCAIs). Infection is a challenge for medical services everywhere and a significant public health concern. It may lead to a protracted hospital stay, long-term incapacity, an increase in the resistance of bacteria to antimicrobial agents, a significant increase in the financial load on the health system, high patient costs, and morbidity.5,6

HAIs affect hundreds of millions of patients and approximately 3 million healthcare professionals around the world every year regardless of the economic level of countries. 7 Globally, each year, nearly 2 million Needle Stick Injuries (NSIs) occur among HCWs, resulting in approximately 16 000 Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and 66 000 Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infections. 8 The increased burden of HAIs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) affects especially high-risk populations like patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) and neonates. On average, in high-income countries, up to 30% of patients are affected by at least 1 HAI in intensive care units; in developing countries the frequency is at least 2 to 3 times higher. On average, 61% of HCWs do not adhere to recommended hand hygiene practices. 9

A study done among HCWs in Ethiopia suggested that the annual prevalence of NSI was 17.5% which is attributed to risky habits and suboptimal standard precautions compliance. 5 For this, compliance with infection prevention and control measures is the only way to reduce the burden of HAIs. 10 To solve these problems, internal and international organizations are developing standard safety precautions intended for use to protect HCWs, patients, and support staff from nosocomial infections and various occupational hazards. 11

In Ethiopia, even though there are guidelines, policies and laws on infection prevention practices and control, it is challenged by the accessibility and availability of infrastructures, shortage of staff and personal protective equipment (PPE), the workload, the inadequate structural organization and the lack of awareness that resulted in the poor practice of infection prevention and control practices. 12 Different measures have been carried out by the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health to strengthen infection prevention measures which focused mainly in providing up-to-date information and practical interventions. 13 According to the literature analysis, the majority of the studies focused primarily on public health institutions. Although assessing the compliance of HCWs in private and public institutions would give comprehensive evidence on existing problems and appropriate prevention method, as a result, research on adherence to standard precautions are still required. Relying on existing research, to the best of the investigator’s knowledge, compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town has not been assessed. Therefore, this study will contribute to narrowing these gaps and determining the scope of problems with standard precautions.

Materials and Methods

Study design period and area

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was carried out, from June 10 to 30, 2021 in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia. The town is located approximately 578 Km away from the capital of the country, Addis Ababa. There were 1401 HCWs who had been working in hospitals in Bahir Dar town during the study period. The study included 4 private and 3 public hospitals.

Source and study population

All HCWs working in public and private hospitals found in Bahir Dar town were a source population. HCWs working in selected public and private hospitals were the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All hospital HCWs with a minimum of 6 months of experience and above were included in the study. HCWs who were on annual leave, on maternity leave, and seriously ill during the data collection were excluded from this study.

Sample size determination

The sample size required for the current study was determined by using a double population proportion considering overall compliance with standard precautions practices of HCWs from a previously done study, reported 56.9%, 14 with a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error. A 10% for non-response rate was considered. Finally, a total of 454 HCWs were included in the study.

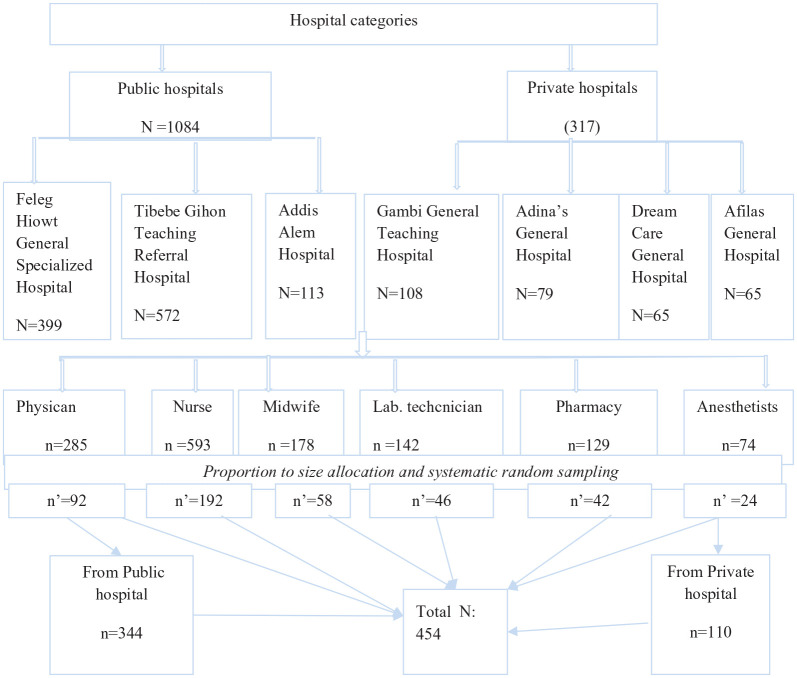

Sampling procedure and sampling technique

First, the sample was proportionally allocated to private and public hospitals. Then there was a distribution of samples to the different professions (strata). Then, each stratum (profession) sample was taken proportionally using a simple random sampling (SRS) technique (Figure 1). The number of HCWs included in the current study based on their profession are provided in the table below (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Sampling technique and procedure on HCWs compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021.

Table 1.

Distribution of HCWs based on their profession in Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021.

| No | Profession type | Feleg Hiowt general specialized hospital | Tibebe Ghion specialized university hospital | Addis Alem hospital | Adinas general hospital | Gambi general teaching hospital | Dream care general hospital | Afilas general hospital | Total | Sampling from each profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nurse | 170 | 280 | 30 | 28 | 43 | 20 | 22 | 593 | 192 |

| 2 | Physician | 67 | 95 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 19 | 19 | 285 | 92 |

| 3 | Midwifes | 60 | 70 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 178 | 58 |

| 4 | Laboratory | 44 | 47 | 15 | 7 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 142 | 46 |

| 5 | Pharmacy | 40 | 42 | 14 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 129 | 42 |

| 6 | Anesthetics | 18 | 38 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 74 | 24 |

| Total | 399 | 572 | 113 | 79 | 108 | 65 | 65 | 1401 | 454 |

Data collection methods

Data was collected using pre-tested and structured questionnaires. The questionnaire was adapted from WHO and Ethiopian National Infection Prevention Guidelines.15,16 The tool included 3 parts, including socio-demographic factors, institutional factors, and individual factors.

Study variables

Dependent Variable : Compliance with standard precautions

Independent Variables : Availability of PPE, accessibility of PPE, workplace safety climate, safety training, IP committee availability, attitude, Knowledge, and IP guideline availability.

Data quality control

The questionnaire was first prepared in English and translated into a local language, Amharic, and then translated back to English to check the consistency of the data collection tool. Before data collection, training was provided for data collectors on all aspects of data collection tools, sampling techniques, and ethical issues. Pretest was done using 5% of the sample size, outside of the study area to check the consistency, clarity, and accuracy of the questionnaires.

Methods of data processing and analysis

The data were coded, cleaned, edited, and entered into Epi data statistical software version 3.1 and were exported to SPSS for analysis. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to describe the characteristics of the study participants using frequencies, tables, and figures. Bi-variate and multivariable logistic regression were used to assess the existence of the association between independent and outcome variables. All variables with P ⩽ .25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the final model of multivariate analysis to control all possible confounders. The model goodness of fit was tested by the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic (P = .37) and Omnibus test (P = .000). The multi co-linearity test was carried out to see the correlation between independent variables using VIF and tolerance tests (no variables were observed with VIF of >10 or tolerance test <.1). The direction and strength of statistical associations were measured by odd ratio along with 95% CI. Finally, P-value <.05 in the multiple logistic regression was considered as a cut-off point for the statistically significant association.

Operational definitions

Knowledge

The knowledge of HCWs were assessed using 26 questions. All correct answers received 1 and incorrect answers received 0. A score of above 67.4% were considered as a good knowledge, whereas those who scored less than 67.4% were considered as to have poor knowledge. 17

Attitude

The attitude of HCWs is determined by 8 attitude questions using the Likert scale. Positive statements received scores ranging from 5 to 1 (strongly agree to strongly disagree). All of the individual responses were added together to provide scores, and those who had an average (50.2%) were considered as a positive attitude, whereas those who scored less than 50.2% were considered as a negative attitude. 18

Compliance

In this study, compliance is the extent to which HCWs practices are under WHO guidelines on infection prevention and control (PPE practices, hand hygiene practices, sharp handling practices, and instrument processing and waste handling practices). There were 26 questions concerning standard precautions which were measured based on the Likert scale. Rating questioners were included from 1 to 5 (1 never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 often, 5 very often). Study participants who scored more than or equal to the mean score value were considered as having good compliance (complaints) to standard precaution practices while these scored less than the mean score value were considered as poor compliance (non-compliant) to standard precaution practices. Respondents’ compliance scores were converted to percentages and used to categorize compliance levels. Scores above (59.5%) were considered as compliance, and scores below (59.5%) were considered as non-compliance. 18

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 442 healthcare workers were participated in the study, yielding a response rate of 97.5%. More than half (53%) of the respondents were females, and 63% were married. Almost three-fifths of those polled were between the ages of 25 and 30, with nearly two-fifths working as nurses, 265 (60%) of the participants were first-degree holders (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 442).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 211 | 47 |

| Female | 231 | 53 | |

| Age of respondent | <25 | 35 | 8 |

| 25-30 | 260 | 59 | |

| ⩾31 | 147 | 33 | |

| Marital status of respondents | Single | 148 | 33 |

| Married | 278 | 63 | |

| Divorced | 16 | 4 | |

| Educational status | Diploma | 100 | 23 |

| First degree | 265 | 60 | |

| Second degree and above | 77 | 17 | |

| Types of profession | Physician | 89 | 20 |

| Nurse | 186 | 42 | |

| Midwifes | 59 | 13 | |

| Laboratory | 44 | 10 | |

| Pharmacy | 42 | 10 | |

| Anesthetists | 22 | 5 | |

| Service year | <2 | 60 | 14 |

| 2-5 | 205 | 46 | |

| ⩾6 | 177 | 40 | |

| Type of wards | Medical ward | 24 | 5.4 |

| Surgical ward | 32 | 7.2 | |

| General operation room | 33 | 7.6 | |

| Emergency and inpatient | 12 | 2.7 | |

| Gynecology and obstetric | 71 | 16 | |

| Ortho ward | 29 | 6.6 | |

| Orthopedics room | 67 | 15.2 | |

| Radiology room | 9 | 2 | |

| Pedi ward | 19 | 4.3 | |

| Laboratory room | 46 | 10.4 | |

| Fistula ward | 8 | 1.8 | |

| Anesthetists room | 24 | 5.4 | |

| OPD | 68 | 15.4 |

Abbreviation: OPD, outpatient department.

Available facilities for infection control

The majority of respondents (84.6%) stated that their unit or department has functional handwashing facilities. The availability of a consistent water supply was mentioned by 53.4% of the respondents. More than half (53.2%) of HCWs reported that their health facility had an appropriate supply of resources to carry out standard precautions measures. Out of 442 HCWs, 54.5% received training in infection-prevention practices (Table 3).

Table 3.

Availability of standard precautions facilities in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 422).

| Variables | Category | No | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional handwashing facility availability | Yes | 374 | 84.6 |

| No | 68 | 15.4 | |

| Availability of consistent water supply on a daily basis (n = 374) | Yes | 236 | 53.4 |

| No | 138 | 31.2 | |

| Availability of PPE | Yes | 192 | 43.4 |

| No | 250 | 56.6 | |

| Availability of adequate supply of resources to apply standard precautions | Yes | 235 | 53.2 |

| No | 207 | 46.8 | |

| Accessibility of PPE | Yes | 184 | 41.6 |

| No | 258 | 58.4 | |

| Training on infection prevention standard precautions | Yes | 241 | 54.5 |

| No | 201 | 45.5 | |

| Frequency of training | Once | 205 | 46.2 |

| Twice | 36 | 8.1 | |

| Presence of infection prevention committee | Yes | 366 | 82.8 |

| No | 76 | 17.2 | |

| Provision of support supervision | Yes | 228 | 51.6 |

| No | 138 | 31.2 | |

| Feedback on support supervision | Yes | 187 | 42.3 |

| No | 41 | 9.3 | |

| Frequency of evaluating management staff | Less frequent | 203 | 45.9 |

| More frequent | 239 | 54.1 | |

| Work place safety climate | Satisfactory | 227 | 51.4 |

| Unsatisfactory | 215 | 48.6 | |

| Availability of written policy for general hygiene and cleaning | Yes | 237 | 54 |

| No | 205 | 46 |

Abbreviation: APPE: personal protective equipment.

Knowledge of healthcare workers regarding infection prevention

Out of 442 HCWs, only 55.8% were aware that their institution had an IP guideline. When it came to the mechanisms of transmission of HAIs, the majority of the respondents (96.9%) knew that contact with blood and body fluids was the most common, while the least common was through contaminated hands (70.3%). Regarding HAIs prevention, 94.4% of respondents understood that maintaining good hand hygiene was one method, while isolation was the least well-known (66.9%). Overall, about 68.1% of respondents knew standard precautions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Knowledge of HCWs compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 442).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information about IP standard precautions | Yes | 281 | 63.6 |

| No | 161 | 36.4 | |

| Information about HAIs | Yes | 268 | 60.6 |

| No | 174 | 39.4 | |

| Awareness on IP guidelines in the healthcare institutions | Yes | 247 | 55.8 |

| No | 195 | 44.2 | |

| Accessibility of the document (n = 247) | Yes | 158 | 64 |

| No | 89 | 36 | |

| Infection prevention control could be monitored | Yes | 207 | 46.8 |

| No | 235 | 53.2 | |

| Which method could be used to prevent infection? | Hand hygiene | 251 | 94.4 |

| PPE | 245 | 92.1 | |

| Proper disposal of medical waste | 216 | 81.2 | |

| Decontamination of instruments | 188 | 70.7 | |

| Isolation | 178 | 66.9 | |

| How could HCWs keep their hand hygiene? | Antimicrobial soap and water | 245 | 86.9 |

| Alcoholic solution | 105 | 37.2 | |

| Surgical hand scrub | 53 | 18.8 | |

| Any water | 13 | 4.6 | |

| Which practice should be applied to prevent sharp and needle stick injuries? | Avoiding open damping | 10 | 3.3 |

| Avoiding workload | 36 | 11.8 | |

| Avoiding recapping needles and syringes | 83 | 27.2 | |

| Disposing of puncture-resistant containers | 190 | 62.3 | |

| Avoiding reusing needles and syringes | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Using safety box | 238 | 78.0 |

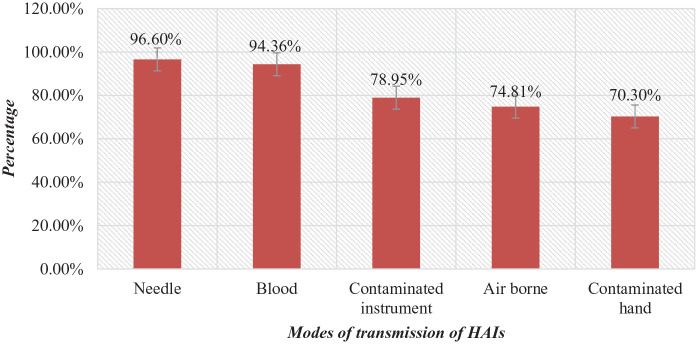

Furthermore, the mode of transmission of HAIs reported by the study participants is reported in Figure 2. About 96.6%, 94.36%, 78.95%, 74.81%, and 70.3% of the participants reported that HAIs are transmitted by needle, blood, contaminated instrument, air-borne, and contaminated hands, respectively.

Figure 2.

HCWs knowledge regarding HAIs transmission.

Attitude about standard precautions

This study found that 59 (13.3%) of respondents disagreed with the idea that all cuts and abrasions on their hands should be covered with a water-proof dressing. However, 175 (31.6%) of participants agreed that removing a wristwatch and any bracelets before washing hands is not obligatory, while 239 (54%) disagreed. About half (51.8%) of the respondents had a positive attitude regarding following standard precaution procedures (Table 5).

Table 5.

Attitude of HCWs toward compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variables | Strongly agree No (%) | Agree No (%) | Undecided No (%) | Dis agree No (%) | Strongly disagree No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keeping nails short clean and polish free | 246 (55.7) | 84 (41.6) | 7 (1.6) | 5 (1.1) | |

| Avoid wearing wrist watches and jewelery when on duty not mandatory | 87 (19.7) | 152 (34.4) | 29 (6.6) | 140 (31.7) | 34 (7.7) |

| Any cuts and abrasions in HCWs hands are covered with a water proof dressing | 148 (32.8) | 207 (46.8) | 31 (7) | 59 (13.3) | — |

| Removing wrist watch and any bracelets is not necessary before washing my hands | 80 (18.1) | 95 (21.5) | 28 (6.3) | 200 (45.2) | 39 (8.8) |

| Drying hands proper to prevent recontamination | 151 (34.2) | 251 (56.8) | 14 (3.2) | 21 (4.8) | 5 (1.1) |

| HCWs supplied with disposable papers and towels of good quality for hand drying | 152 (34.4) | 223 (50.5) | 34 (7.7) | 26 (5.9) | 7 (1.6) |

| Changing gloves before going to another patient | 168 (38) | 203 (45.9) | 14 (3.2) | 53 (12) | 4 (0.9) |

| Wearing gloves can substitute hand washing | 133 (30.1) | 260 (58.8) | 19 (4.3) | 19 (4.3) | 11 (2.5) |

Compliance with standard precautions

Handwashing is always practiced by 11.5% and 37.6% of HCWs before and after handling a patient, respectively. A total of 116 (26.2%), 109 (24.7%), and 139 (31.4%) HCWs were always wearing eye goggles, masks, and boots when indicated, respectively. Furthermore, 46 (10.4%) of participants always use a yellow color-coded dust bin for infectious waste, and 77 (17.4%) always use a safety box for needles and syringes. A total of 172 (38.9%) were never recapped needles, whereas 169 (36.9%) were never bent needles. About 15.6% of HCWs always utilize a 0.5% prepared chlorine solution for decontamination. Furthermore, 161 (36.4%) and 154 (34.8%) frequently employed cleaning and sterilization, respectively. In general, 63.1% of HCWs did not follow standard precautions while performing routine activities (Table 6).

Table 6.

HCWs compliance with standard precautions in hospitals of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 442).

| Variables | Level of compliance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | |

| No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | |

| Wash hands before touching a patient | 88 (19.9) | 119 (26.9) | 92 (20.8) | 92 (20.80) | 51 (11.5) |

| Wash hands after touching a patient | 63 (14.3) | 29 (6.6) | 19 (4.30) | 165 (37.3) | 166 (37.6) |

| Wash hands before cleaning/aseptic any procedure | 53 (12) | 70 (15.8) | 166 (37.6) | 101 (22.9) | 52 (11.8) |

| Wash hands after exposure to BBFs | 41 (9.3) | 45 (10.2) | 91 (20.6) | 144 (32.6) | 121 (27.4) |

| Wash hands immediately after removing a gloves | 30 (6.8) | 28 (6.3) | 78 (17.6) | 142 (32.1) | 164 (37.1) |

| Wash hands between patient contacts | 71 (16.1) | 198 (44.8) | 107 (24.2) | 38 (8.6) | 28 (6.3) |

| Wash hands after touching the patient surrounding | 37 (8.40) | 55 (12.4) | 479 (10.6) | 151 (34.2) | 151 (34.2) |

| Wash hands using antimicrobial soap | 6 (1.4) | 133 (30.10) | 81 (18.3) | 100 (22.6) | 121 (27.4) |

| Wash hands using water only | 24 (5.4) | 46 (10.4) | 90 (20.4) | 165 (37.3) | 117 (26.5) |

| Wash hands using alcohol antiseptic and water | 10 (2.3) | 55 (12.4) | 191 (43.2) | 118 (26.7) | 68 (15.4) |

| Provide care considering all patients are potentially infectious | 16 (3.6) | 49 (11.10) | 37 (8.4) | 1679 (37.8) | 173 (39.1) |

| Wear clean gloves whenever there is a possibility of any exposure to blood and body fluids | 5 (1.1) | 28 (6.3) | 50 (11.3) | 215 (48.6) | 144 (32.6) |

| Wear a gown when carrying out activities | 13 (2.9) | 21 (4.80) | 249 (56.3) | 159 (36.0) | |

| Wear eye goggles when indicated | 22 (5) | 54 (12.2) | 54 (12.2) | 196 (44.3) | 116 (26.2) |

| Wear face masks when indicated | 12 (2.70 | 50 (11.3) | 29 (6.6) | 242 (54.8) | 109 (24.7) |

| Wear boots when indicated | 24 (5.4) | 69 (15.6) | 28 (6.3) | 182 (41.2) | 139 (31.4) |

| Use sterilized reusable equipment before being used on another patient | 20 (4.5) | 59 (13.3) | 194 (43.9) | 101 (22.9) | 68 (15.4) |

| Segregate infectious wastes in the black color-coded dustbin | 33 (7.5) | 196 (44.3) | 83 (18.8) | 76 (17.2) | 54 (12.2) |

| Disinfect equipment and surfaces | 14 (3.2) | 38 (8.6) | 239 (54.1) | 93 (21) | 58 (13.1) |

| Seggregate infectious medical waste in a yellow color-coded dustbin | 21 (4.8) | 201 (45.5) | 90 (20.4) | 84 (19) | 46 (10.4) |

| Dispose used needles and syringes in to safety box immediately | 11 (2.5) | 31 (7) | 227 (51.4) | 96 (21.7) | 77 (17.4) |

| Place used sharps in puncture-resistant containers at points of use | 16 (3.6) | 41 (9.3) | 230 (52) | 84 (19) | 71 (16.1) |

| Recape needles | 172 (38.9) | 227 (51.4) | 43 (9.70) | 0 | 0 |

| Bend needles | 163 (36.9) | 202 (45.7) | 39 (8.8) | 16 (3.6) | 22 (5) |

| Use a decontamination sock in 0.5% chlorine solution for 10 minutes | 25 (5.7) | 19 (4.3) | 179 (40.50) | 150 (33.9) | 69 (15.6) |

| Use sterilized materials | 17 (3.8) | 16 (3.6) | 139 (31.4) | 154 (34.8) | 116 (26.2) |

| Avoid recapping and other hand manipulation of needles | 21 (4.8) | 13 (2.9) | 124 (28.1) | 218 (49.3) | 66 (14.9) |

| Use safety boxes | 12 (2.7) | 16 (3.6) | 106 (24) | 232 (52.5) | 76 (17.2) |

| Avoid disambling sharps | 13 (2.9) | 20 (4.5) | 112 (25.3) | 235 (53.2) | 62 (14) |

| Avoid over passing sharps with other person | 7 (1.6) | 24 (5.4) | 107 (24.20) | 230 (52) | 74 (16.7) |

Factors associated with HCWs compliance with standard precautions

In multivariate logistic regression, HCWs who were working in private hospitals (AOR = 2.22 and 95% CI = 1.40, 3.522) were 2.22 times more likely to comply with standard precautions compared to those who were working in public hospitals. Furthermore, HCWs with 2 to 5 years of experience (AOR = 1.95 and 95% CI = 1.02, 37.1) were 1.95 times more likely to follow standard precautions than those with less than 2 years. Similarly, those who had ⩾6 years of experience or service years were 2.78 times (AOR = 2.78 and 95% CI = 1.40, 5.52) more likely to have complied with standard precautions compared to those who had below 2 years.

Similarly, HCWs who had a consistent water supply were 1.92 times (AOR = 1.92 and 95% CI = 1.63, 6.27) more likely to comply with standard precautions compared to those who had no consistent water supply. HCWs working in health facilities who wore adequate PPE were 2.32 times more likely (AOR = 2.32 and 95% CI = 1.35, 3.98) to have followed standard precautions than their counterparts. HCWs working in the health facilities had a guideline that was 1.73 times (AOR = 1.73 and 95% CI = 1.08, 2.77) more likely to comply with standard precautions compared to their counterpart. Furthermore, HCWs who had a negative attitude toward compliance with standard precautions were 79% less likely to comply with standard precautions (AOR = 0.21 and 95% CI = 0.15, 0.36) compared to their counterparts (Table 7).

Table 7.

Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression on factors associated with HCWs compliance with standard precautions in Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 442).

| Variables | Category | Compliance | P-value | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance | Non compliance | |||||

| Types of hospitals | Public | 122 (67.4) | 210 (80.4) | .002 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Private | 59 (32.6) | 51 (19.6) | 0.50 (0.32, 0.77) | 2.22 (1.40, 3.52)* | ||

| Marital status of respondents | Single | 68 (37.5) | 80 (30.6) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Married | 109 (60.3) | 169 (64.7) | .18 | 0.759 (0.50, 1.13) | 0.66 (0.43, 1.03) | |

| Divorced | 4 (2.2) | 12 (4.7) | .119 | 0.392 (0.12, 1.27) | 0.34 (0.10, 1.16) | |

| Service year | <2 year | 18 (9.9) | 42 (16) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 2-5 year | 83 (46.1) | 120 (45.9) | .111 | 1.65 (0.89, 3.06) | 1.95 (1.02, 3.71)* | |

| ⩾6 year | 78 (43) | 99 (38.1) | .057 | 1.84 (0.98, 3.44) | 2.78 (1.45, 52)* | |

| Consistent water supply is availability on a daily basis | Yes | 136 (52) | 100 (55.3) | .027 | 0.82 (0.53, 0.96) | 1.92 (1.63, 6.27)* |

| No | 86 (48) | 52 (54.7) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Availability PPE | Yes | 61 (33.7) | 102 (39) | .204 | 0.79 (0.53, 1.17) | 2.32 (1.35, 3.98)* |

| No | 120 (66.3) | 159 (61) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Adequate supply resource | Yes | 107 (59) | 128 (70.7) | .037 | 1.5 (1.02, 2.20) | 1.4 (0.92, 2.14) |

| No | 74 (41) | 133 (29.3) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| PPE accessibility | Yes | 96 (53) | 165 (63) | .033 | 0.65 (0.44, 0.96) | 0.59 (0.34, 1.03) |

| No | 85 (47) | 96 (37) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Training on infection prevention standard precautions | Yes | 88 (48.6) | 153 (58.6) | .038 | 0.66 (0.45, 0.97) | 0.54 (0.24, 1.21) |

| No | 93 (51.4) | 108 (41.4) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| IP guide availability | Yes | 113 (43) | 58 (32) | .017 | 1.62 (1.08, 2.40) | 1.73 (1.08, 2.77)* |

| No | 148 (57) | 123 (68) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Provision of supporting supervision | Yes | 85 (47) | 143 (54.7) | .048 | 0.64 (0.42, 0.99) | 0.79 (0.36, 1.77) |

| No | 66 (53) | 72 (45.3) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Written policy availability | Yes | 93 (51.4) | 112 (43) | .08 | 1.4 (0.96, 2.05) | 1.17 (0.72, 1.91) |

| No | 88 (48.6) | 149 (57) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Frequency of evaluating the Management of supporting staff | Less frequent | 107 (59) | 96 (53) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| More frequent | 154 (41) | 85 (47) | .013 | 1.62 (1.10, 2.38) | 0.75 (0.45, 1.23) | |

| Workplace safety climate | Satisfactory | 101 (55.8) | 126 (48.2) | .12 | 1.35 (0.92, 1.98) | 1.84 (0.95, 2.93) |

| Unsatisfactory | 80 (44.2) | 135 (51.8) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Attitude | Negative | 59 (33) | 169 (64.7) | .000 | 0.26 (0.17, 0.39) | 0.21 (0.15, 0.36)** |

| Positive | 122 (67) | 92 (35.3) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Knowledge | Poor knowledge | 12 (6.6) | 7 (2.6) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Knowledgeable | 169 (93.4) | 254 (97.4) | .234 | 1.28 (0.85, 1.93) | 1.42 (0.90, 2.22) | |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odd ratio; IP, infection prevention; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Significant association (P-value < .05). **P-value ⩽ .001.

Discussion

This study revealed that overall compliance with SPs among HCWs in Bahir Dar town hospitals was 41% (95% CI = 36.7, 45.9), implying that 4 out of every 10 HCWs followed SPs. As a result, 6 out of every 10 HCWs may be exposed to occupational risk, particularly nosocomial infection. However, the level of compliance in this study is lower than when compared to a study conducted in the Dawuro zone (65%) and Addis Ababa (66.1%).18,19 However, it was higher than the finding of the study conducted in the Hdya Zone (15%). 14 This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in the study site, participants, study period, and availability of resources to implement standard safety precautions, as well as poor supervision, workload, and HCWs’ irresponsibility. For instance, the practice of following standard precautions was aided by continuous guidance, training, real-time feedback, and educational interventions that would provide all HCWs with the necessary information. 20

According to a recent study, HCWs compliance is higher in private hospitals compared to public hospitals. This research is similar to a study done in Tanzania. According to a Tanzanian study, private facilities had nearly double the chance of obtaining the recommended IPC level compared to public facilities. 21 This could be attributed to lower patient volumes, superior individual expertise availability, dedication to duty, or HCWS commitments to carry out routine activities more efficiently than in public hospitals. 22

HCWs with 2 to 5 years and 6-year of experience were more likely to follow SPs than those with less than 2 years of experience, which is similar to a study conducted in the Bale zone. 23 Therefore, HCWs with a longer year of experience are more compliant than those with a shorter stay. This could be because HCWs with many years of experience had enough knowledge about infection-prevention procedures, disease transmission mechanisms, and disease prevention methods. Afterall they might attend more seminars, conferences, and training sessions.

HCWs in facilities where a steady water supply were more compliant with SPs when compared to those working in facilities with no continuous water supply. The result is lower than a finding in Hawassa teaching and referral hospitals which shows that the HCWs who had running tap water in their workroom were approximately 3 times more likely to be compliant than those who did not have it. 24 These differences may be due to the availability and accessibility of water in different settings. Adequate supplies of basic necessities, such as water, contribute to greater compliance with IPC principles.

HCWs with access to PPE were more likely to follow standard precautions than those who did not have access. In the present study, it is lower than in a study in the Dawruo Zone, 18 which indicates that individuals with available PPE were approximately 10 times more likely than those without available PPE. This disparity could be healthcare professionals’ unwillingness to follow standard protocols as well as a lack of infection-control supplies and equipment such as masks, goggles, and alcohol-based hand rubs, which have been identified as obstacles to following standard precautions. The problem of non-compliance with standard precaution measures was aggravated by a lack of supplies and equipment. 25

HCWs who had access to IP guidelines were more compliant with SPs compared to those who did not have access to them. The current study result is lower than a finding from the Hadya Zone, which reported that those with access to IP guidelines were 2.5 times more likely to follow standard precautions than those without. 14 This could be due to increased understanding and dedication to standard measures as a result of having access to the document. The mismatch could be because of the lack of access to the document that led to a failure to follow standard precautions procedures.

Conclusions

Two-fifths of HCWs compliance with standard precautions and availability of consistent water supplies, availability of PPE, types of hospital, service year, access to infection prevention guidelines, and attitude were independently associated with compliance with infection prevention standard precautions. Therefore, this required strong commitment from all stakeholders, especially all private and public hospital administrators and Amhara Regional Health Office, should give and organize a mandatory seminar, workshop, or training for HCWs to ensure that infection prevention standard precautions are properly implemented. Additionally, each hospital administrator must address insufficient standard precautions supplies such as PPE, waste collecting bins, hand hygiene items, and water shortages and each hospital IP committee should be organized, and frequent support supervision should be conducted.

Limitation of study

One of the limitations of this study was the possibility of response bias as study participants likely over-report their practices. The site and study participants were only hospital HCWs, so generalizing other health centers and clinics was difficult.

Acknowledgments

We would also thank the Haramaya University College of Health and Medical Sciences Department of Environmental Health Science for organizing the student research program. Finally, many thanks go to all hospital managers and study participants for giving the required information for the preparation of the research project.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received a grant only for data collection from Haramaya University.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors Contributions: SM was involved in conducting the background study, writing the manuscript and detailed analysis of the results. BAM, AG, NB, DAM, TSA, LMT, YMD, YAA, WD, FKA, DMA, AB, and GD were also involved in supervision, gave directions and feedback, editing, and review of the manuscript. Finally, all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agreed on all aspects of this work.

Data Availability: Almost all data are included in this study. However, additional data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of the Faculty of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University (Ref. no.: IHRERC/075/2021). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals and concerned bodies included in this study.

References

- 1. Elston J, Hinitt I, Batson S, et al. Infection control in a developing world. Health Estate. 2013;67:45-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith H, Watkins J, Otis M, Hebden JN, Wright MO. Health care-associated infections studies project: an American Journal of Infection Control and national healthcare safety network data quality collaboration case study – chapter 2 identifying healthcare-associated infections (HAI) for NHSN surveillance case study vignettes. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:695-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prasad K, Mayank D, Anshuman M, Singh R, Afzal A, Baronia A. Nosocomial cross-transmission of Pseudomonas aeruginosa between patients in a tertiary intensive care unit. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joseph NM, Sistla S, Dutta TK, Badhe AS, Rasitha D, Parija SC. Role of intensive care unit environment and health-care workers in transmission of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:282-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mandona E, Obi Daniel E, Olaiya Abiodun P, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of infection prevention among health care providers in Chibombo District Zambia. World Journal of Public Health. 2019;4:87. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide Clean Care is Safer Care. World Health Organization; 2011: 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization ROfS-EAaR PO. Infection control practices. 2004. SEARO Regional Publication No. 41:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raka L, Mulliqi-osmani G. Infection control in developing world. February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level. World Health Organization; 2016. http://apps.who.int/bookorders (accessed 12 July 2021). [PubMed]

- 10. Sahiledengle B, Gebresilassie A, Getahun T, Hiko D. Infection prevention practices and associated factors among healthcare workers in governmental healthcare facilities in Addis Ababa. Ethiop J Sci. 2018;28:177-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prüss-ustün Rapiti E, Hutin Y; World Health Organization. Pruss ustun et al.pdf. Am J Ind Med. 2003;2005:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kasa AS, Temesgen WA, Workineh Y, et al. Knowledge towards standard precautions among healthcare providers of hospitals in Amhara region, Ethiopia, 2017: a cross sectional study.. Archives of Public Health. 2020;78:127-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tadesse T, Abebe F, Hawkins A, Pearson J. Improving Infection Prevention and Control in Ethiopia Through Supportive Supervision of Health Facilities. AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources Project.1-6; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yohannes T, Kassa G, Laelago T, Guracha E. Health-care workers’ compliance with infection prevention guidelines and associated factors in Hadiya Zone, southern Ethiopia: hospital based cross sectional study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15. MOH. The National Infection Prevention Guidelines for healthcare facilities in Ethiopia. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization (WHO). Infection Prevention and Control Assessment Framework at the Facility Level. World Health Organization; 2016:1-16. https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/tools/core-components/IPCAF-facility.PDF (accessed 12 July 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yetneberk T, Firde M, Adem S, Fitiwi G, Belayneh T. An investigation of infection prevention practices among anesthetists. Perioper Care Oper Room Manag. 2021;24:100172. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beyamo A, Dodicho T, Facha W. Compliance with standard precaution practices and associated factors among health care workers in Dawuro Zone, South West Ethiopia, cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:381-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Angaw DA, Gezie LD, Dachew BA. Standard precaution practice and associated factors among health professionals working in Addis Ababa government hospitals, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study using multilevel analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mpamize G. Adherence to universal precautions in infection prevention among health workers in Kabarole district. J Health Med Nurs. 2016;26:144-155. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kinyenje E, Hokororo J, Eliakimu E, et al. Status of infection prevention and control in Tanzanian Primary Health Care Facilities: learning from star rating assessment. Infect Prev Pract. 2020;2:100071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oli A, Ekejindu C, Ejiofor O, Oli A, Ezeobi I, Ibeh C. The knowledge of and attitude to hospital-acquired infections among public and private healthcare workers in south-east, Nigeria. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;11:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zenbaba D, Sahiledengle B, Bogale D. Practices of healthcare workers regarding infection prevention in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2020;2020:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bekele T, Ashenaf T, Ermias A, Arega Sadore A. Compliance with standard safety precautions and associated factors among health care workers in Hawassa University comprehensive, specialized hospital, southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee R. Occupational transmission of bloodborne diseases to healthcare workers in developing countries: meeting the challenges. J Hosp Infect. 2009;72:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]