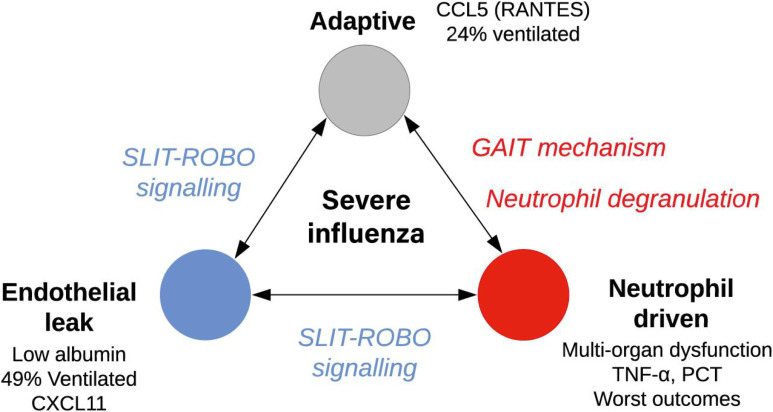

P010 - ARDS Ruler

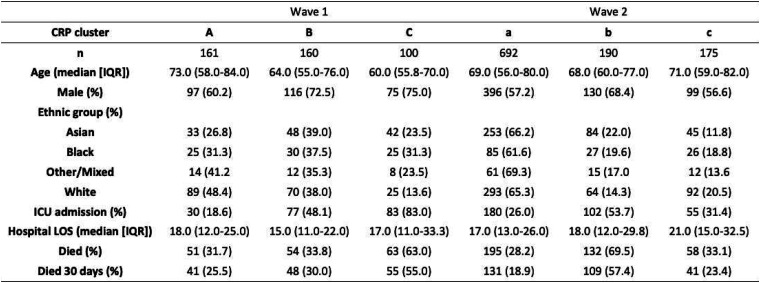

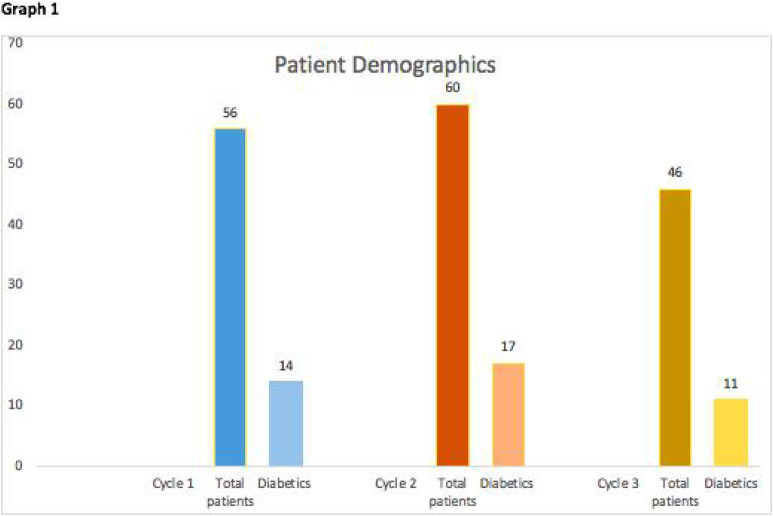

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

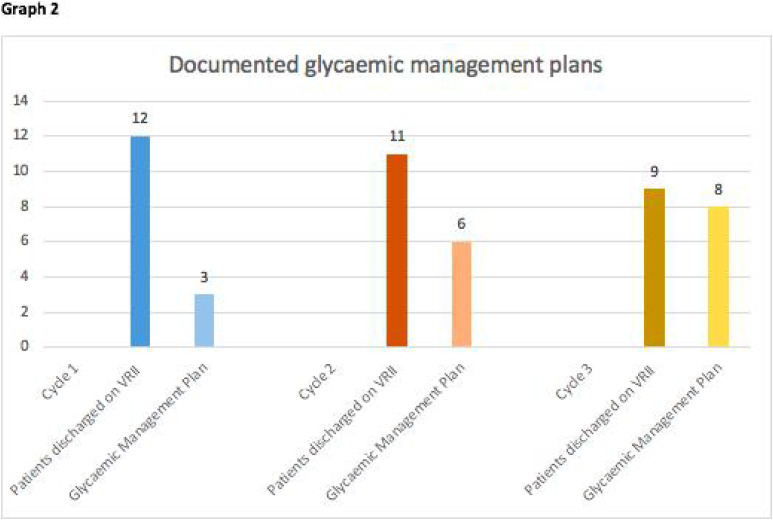

Carl Tua1 and Michael Buttigieg 2

1Mater Dei Hospital, Malta

2Mater Dei Hospital

Abstract

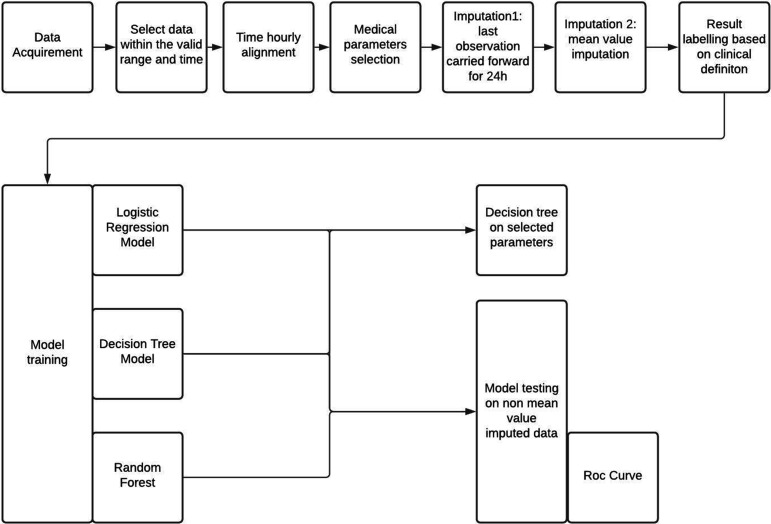

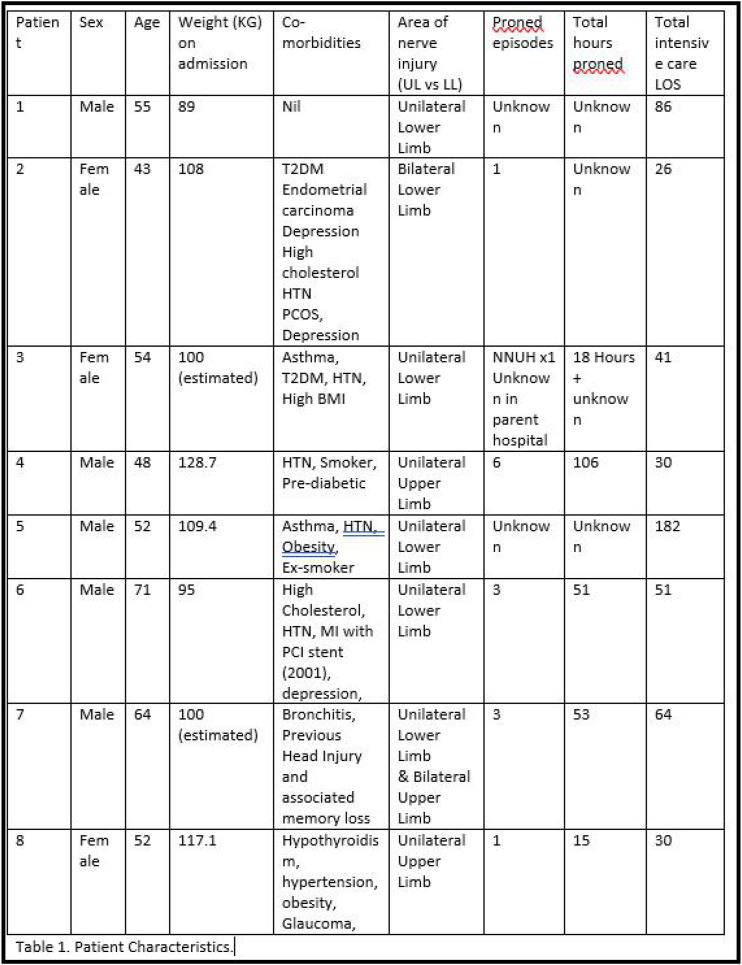

Introduction: Following the publication of the ARDS Network (ARDSnet) trial over two decades ago lung protective ventilation with low tidal volumes has become a mainstay in the evidence based management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The ARDSnet trial protocol uses the Devine formula which is based on height and gender to calculate the predicted body weight (PBW) which is then used to calculate the tidal volume in ml/kg.1-2

The first step to calculating a safe tidal volume is measuring the patient’s height. Visual estimates of patient’s height are often inaccurate and measurements in some patient groups can be challenging. Various methods have been suggested to aid accuracy and ease of measurement. Once the height is known the second step is to use the Devine formula to calculate the PBW. This is often done using online calculators or using tables with height and the PBW. The third and final step is multiplying the PBW by the desired tidal volume in ml/kg typically starting at 6ml/kg.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the combination of various factors such as greatly increased doctor and nursing workload, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), concerns over the use of reusable equipment such as tape measures and difficult access to online calculators for PBW calculation when donned in PPE in some COVID-19 units made measuring height and calculating a safe tidal volume particularly challenging.3

Objectives: To develop a quick, safe way of calculating lung protective tidal volumes for ARDS patients including in COVID-19 Intensive care units.

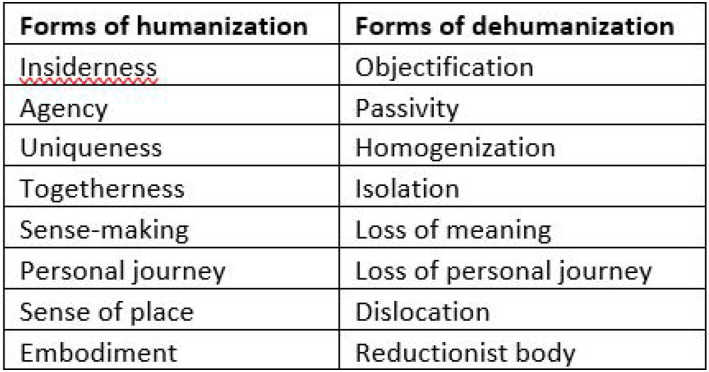

Methods: We used the Devine formula to calculate the PBW in males and females at every centimeter (cm) from 152cm to 200cm. Males PBW= 50 + (0.91 × [height in centimeters − 152.4]) Female PBW= 45.5 + (0.91 × [height in centimeters − 152.4]). We then multiplied the PBW by 6 to generate a 6ml/kg PBW tidal volume.

Using image editing software, we then designed gender specific rulers with cm markings to measure height placed beside the corresponding calculated PBW and tidal volume 6ml/kg for that height. We also placed the ARDSnet PEEP/Fio2 titration table. The resulting ruler when printed to scale can then be used as a disposable measuring tape that allows height, PBW and 6ml/kg tidal volume to be calculated easily with one measurement and without the need to resort to calculators, tables or reusable equipment.

Results:

Conclusions: These JPEG images can be downloaded and printed to scale. Once printed the ARDS ‘rulers‘ allow easy and quick measurement of height, PBW and 6ml/kg tidal volume with one measurement without resorting to calculators or tables. As they are simply printed on standard paper, they are single use and therefore do not pose an infection control risk.

References

1. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308.

2. Pai MP, Paloucek FP. The origin of the "ideal" body weight equations. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(9):1066-1069. Martin, D.C., Richards, G.N. Predicted body weight relationships for protective ventilation – unisex proposals from pre-term through to adult. BMC Pulm Med 17, 85 (2017).

3. Freitag E, Edgecombe G, Baldwin I, Cottier B, Heland M. Determination of body weight and height measurement for critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A quality improvement project. Aust Crit Care. 2010;23(4):197-207

P011

Lung protective and acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilation strategies in the age of COVID19

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Ben Deeming and Sophie Selley

HENE

Abstract

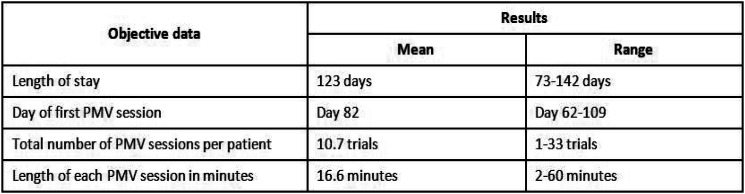

Introduction: The global COVID pandemic has led to an increase in UK intensive care unit (ICU) admissions requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Whilst the optimal management strategies of COVID ARDS are still the topic of research and debate, existing ARDS guidelines1 provide a framework for best practice. The University Hospital of North Durham (UHND) ICU is a 10 bed combined critical care unit which, during the pandemic, cared for significantly more patients requiring IMV for ARDS. We set out to quantify the number of patients requiring IMV and assess the number of these patients receiving optimal ARDS treatments based on the existing ARDS guidelines.1

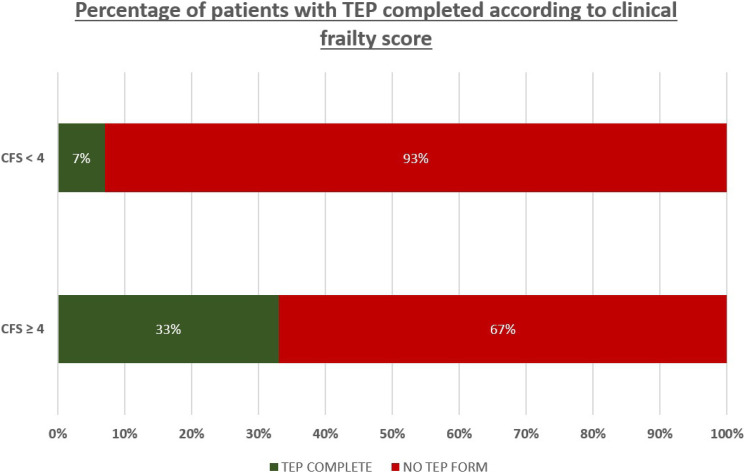

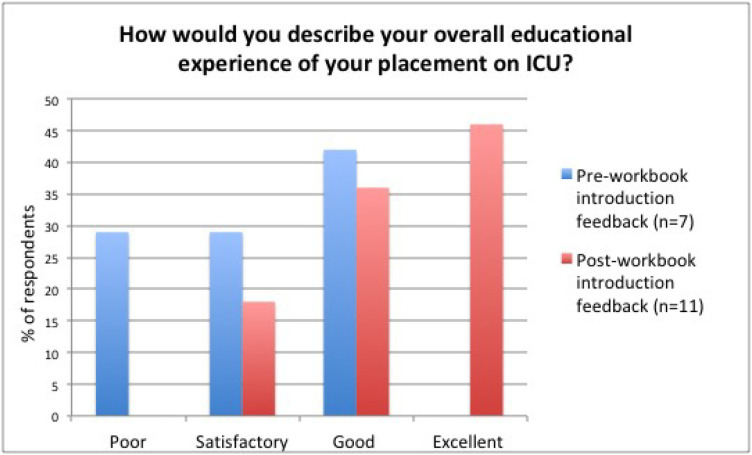

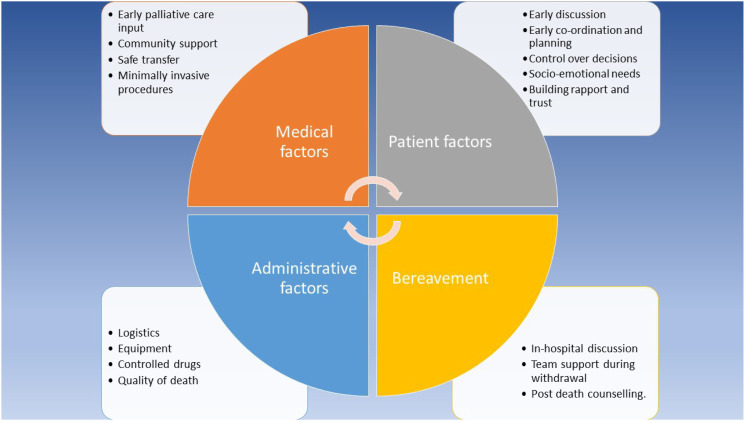

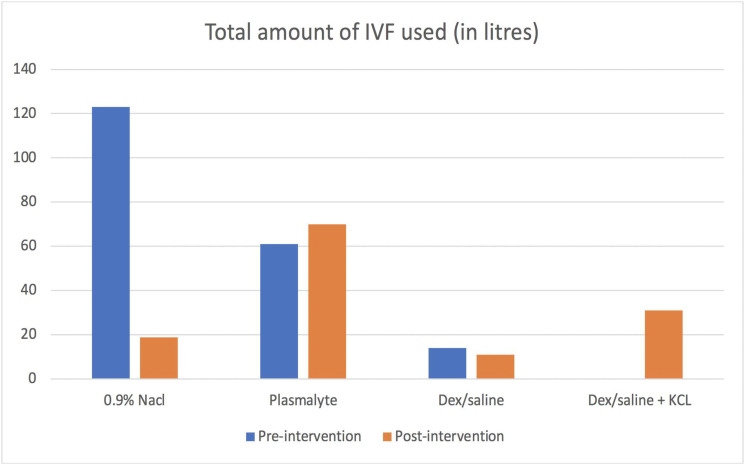

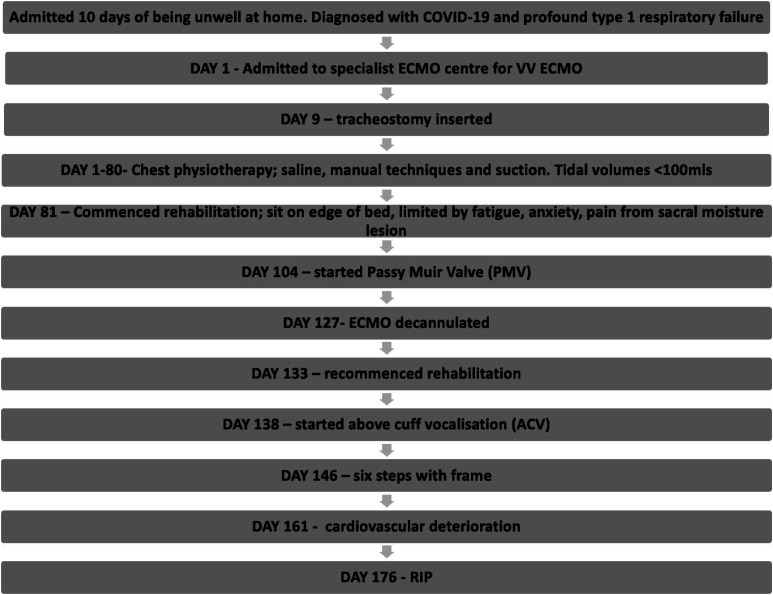

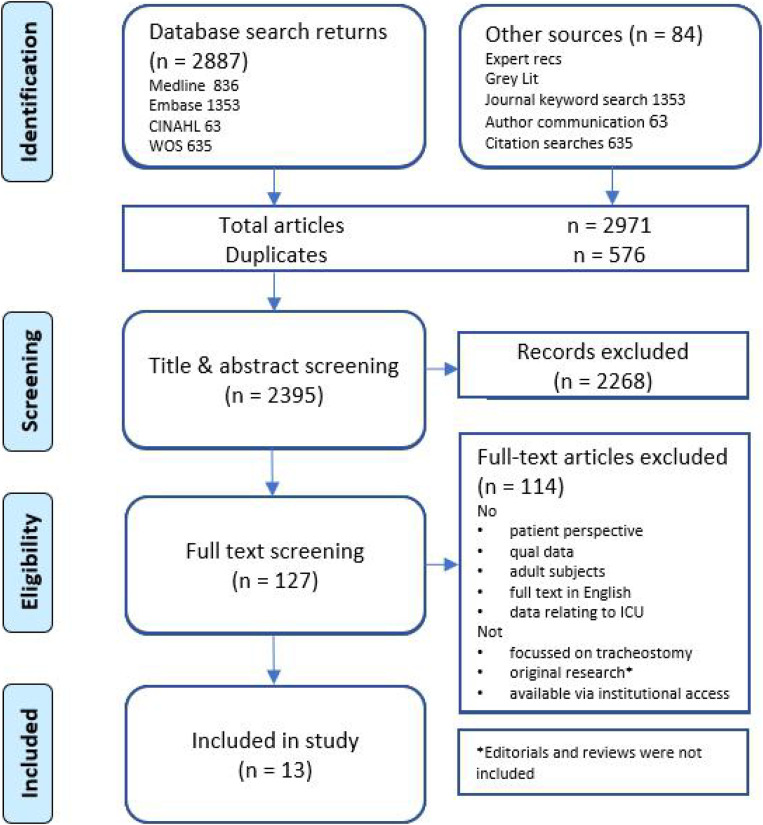

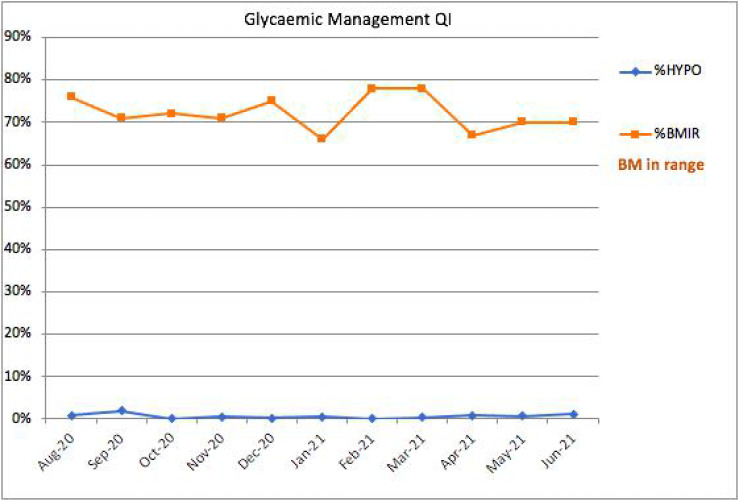

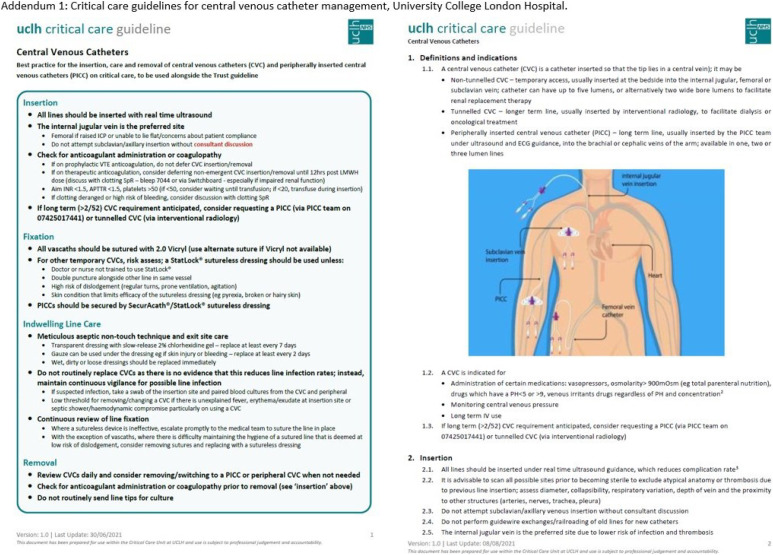

Figure 1.

Male and female ARDS Rulers. Height (cm), PBW (kg) and Tidal volume (6ml/kg) can be read from left to right.

Objectives: Assess performance against best practice guidelines for ventilation in ARDS with standards of 100% of ventilated patients having weight, ideal body weight (IBW), demispans and target tidal volumes documented, ARDS identified and delivered tidal volumes <8ml/kg.

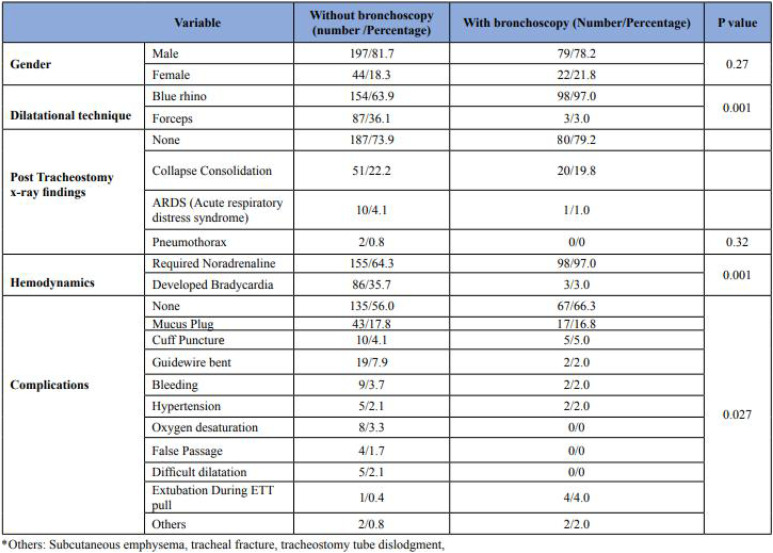

Methods: Prospective case review with inclusion criteria of adult (>18) patients admitted to UHND ICU in January 2021 requiring IMV for any indication. A range of clinical data was collected including arterial blood gas results, ventilator settings and treatments instigated.

Results: 40 patients underwent IMV during the audit, a 250% increase on similar period in 2017, with a mean age of 53. Respiratory failure was the primary indication for ventilation in 48% of which 84% was secondary to COVID. The average length of ventilation and stay was 4.9 days and 7.5 days respectively. Clear documentation of data relevant to ARDS ventilation was poor. 68% of patients had documented weight, 0% an IBW, 5% demispans and 25% target tidal volume.

63% fulfilled criteria for ARDS by the Berlin definition,2 44% of these ‘severe’. Only 20% had ARDS documented as a clinical problem. Despite this the majority (88%) had appropriate delivered tidal volumes (6-8ml/kg) with an average delivered tidal volume of 7.4ml/kg. Recommended ARDS ventilation strategies, depending on severity, were used largely appropriately with 52% of ARDS patients having high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), 76% paralysed and 48% proned. None were referred for extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

ARDS patients without a label of ARDS (‘missed ARDS’) demonstrated less conformance to guidelines than those with positively ‘identified ARDS’, with less paralysis and proning across both moderate and severe cases and two patients receiving inappropriately high tidal volumes (>8ml/kg).

Conclusions: Despite a significant increase in workload from the pandemic and perhaps consequently less complete documentation, the vast majority of patients with ARDS received appropriate lung protective ventilation. However, there is poor labelling of patients with ARDS, which this audit may suggest leads to those patients being less likely to receive ARDS treatments such as paralysis and proning, emphasising the importance of identification of ARDS. We suggest improvements in documentation could be made with proformas for ventilated patients prompting IBW and target tidal volume calculation, as well as serial PF ratios to identify and stratify patients with ARDS, serving as a prompt for consideration of paralysis, proning or ECMO referral.

References

1. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Guidelines on the Management of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (2018). Available from: https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ficm_ics_ards_guideline_-_july_2018.pdf [Accessed 20th July 2021]

2. The ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533

P012

Natural History and Trajectory of non-COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome patients. An observational study for comparison to COVID-19 populations.

Connor Toal 1 , Alex Fowler2, Brijesh Patel3, Zudin Puthucheary1 and John Prowle1

1William Harvey Research Institute, Queen Mary University of London

2William Harvey Research Institute, Queen Mary University of London

3Division of Anaesthetics, Pain Medicine & Intensive Care, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK

Abstract

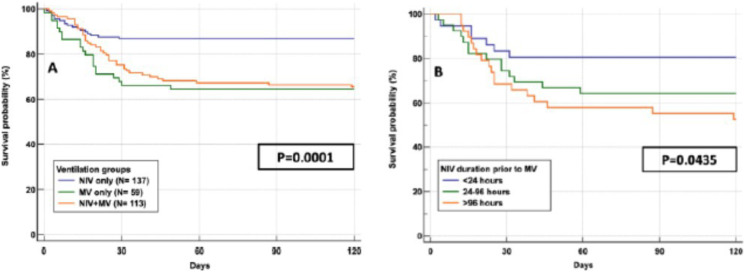

Introduction: Previous studies on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) relate trajectories to initial degree of hypoxia1,2 Further work is required to deduce whether previous ARDS frameworks are applicable to COVID-19 ARDS patients.

Objectives: How does hypoxia progression influence outcomes in non-COVID ARDS patients and does this differ from COVID-19 ARDS patients?

Methods: Mechanically ventilated patients that met the Berlin ARDS Criteria1 were selected from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC) database.3 Daily blood gas and ventilatory settings were analysed, from the point of intubation to death or discharge, allowing longitudinal analysis with high granularity. Our primary outcome was how the trajectory of patients was dependent on their hypoxia progression. Secondary outcomes included how base characteristics and initial clinical parameters affect trajectory and outcomes. Comparative analysis was performed between the results of this study and a previous large COVID-19 ARDS study4

Results: 1,575 ICU admissions were included in the study. All results report this study first followed by the COVID-19 study.4 Overall survival rate was higher (70.2% vs 57.7%); less patients had initial moderate or severe hypoxia (54.5% vs 76.8%); less patients had worsening of hypoxia over the first 7 days (18.9% vs 31.8%); and more patients improved their hypoxia status (33.1% vs 23.5%).

This study showed a smaller proportion of hypoxia non-resolvers compared to the COVID study (32.6% vs 57.9%). However, non-resolvers in the two studies had similar survival rates (58.6% vs 60.4%). Length of ICU stay (LOS) and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was significantly less in this study compared to the COVID-19 study regardless of hypoxia resolver status.

Conclusions: Non-COVID ARDS patients have a more predictable natural history and trajectory compared to COVID-19 ARDs patients. Respiratory failure occurs less frequently and is quicker to resolve, resulting in a lower proportion of hypoxia non-resolvers. However hypoxia non-resolvers of both populations have similar survival outcomes. Despite this, COVID ARDS patient have much longer ICU length of stay and length of ventilation which has significant implications for provision of critical care resources. Further analysis of the impact of COVID-19 therapies on these outcomes is needed.

References

1. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin definition. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc [Internet]. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1160659

2. Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA [Internet]. 2016;315(8):788–800. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2492877

3. Johnson, A., Bulgarelli, L., Pollard, T., Horng, S., Celi, L. A., and Mark R. MIMIC-IV (version 1.0). PhysioNet. 2021.

4. Patel B V., Haar S, Handslip R, Auepanwiriyakul C, Lee TM-L, Patel S, et al. Natural history, trajectory, and management of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients in the United Kingdom. Intensive Care Med [Internet]. 2021;47(5):549–565. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8111053/

P014

Evaluation of neutrophil microvesicles function in a novel tri-culture model of pulmonary vascular inflammation

Eirini Sachouli, Diianeira Maria Tsiridou, Claudia Peinador Marin, Masao Takata, Anthony C. Gordon and Kieran P. O’Dea

Division of Anaesthetics, Pain Medicine and Intensive Care, Imperial College London, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

Introduction: Microvesicles (MVs) are cell-derived membrane-encapsulated particles carrying functional molecular cargo and surface markers derived from their parental cells. Within blood, increased levels of circulating neutrophil-derived microvesicles (N-MVs) are associated with clinical severity in sepsis and severe burns injury patients suggesting potential as biomarkers and mediators of organ injury.1,2 We previously found a dramatic increase of circulating MVs uptake within the pulmonary vasculature by lung-marginated monocytes in a mouse model of endotoxemia.3 As a major site for accumulation of inflammatory cells during sepsis, uptake of N-MVs within pulmonary vascular microenvironment could influence inflammatory processes contributing to indirect acute lung injury.

Objectives: To determine N-MVs target cell-specific interactions and functions within the pulmonary vascular microenvironment by developing an in vitro monocyte-neutrophil-endothelial cell ‘tri-culture’ model of inflammation.

Methods: Neutrophils and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy volunteer blood by density gradient centrifugation, and monocytes from PBMCs by negative immunomagnetic bead selection (Miltenyi). N-MVs were generated by fMLP stimulation of isolated neutrophils. For establishing the tri-culture model, confluent human lung microvascular endothelial cells were pre-treated with low-dose tumour necrosis factor (TNF) to promote uniform leukocyte adherence. After renewal of media, neutrophils and monocytes were added to endothelial cells, allowed to adhere and then incubated with N-MVs for 3hrs. Expression of neutrophil and monocyte activation markers, and generation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were evaluated via flow cytometry. Production of soluble TNF was measured by ELISA. For uptake experiments, N-MVs were labelled with CFSE fluorescent dye, and cell-associated fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry.

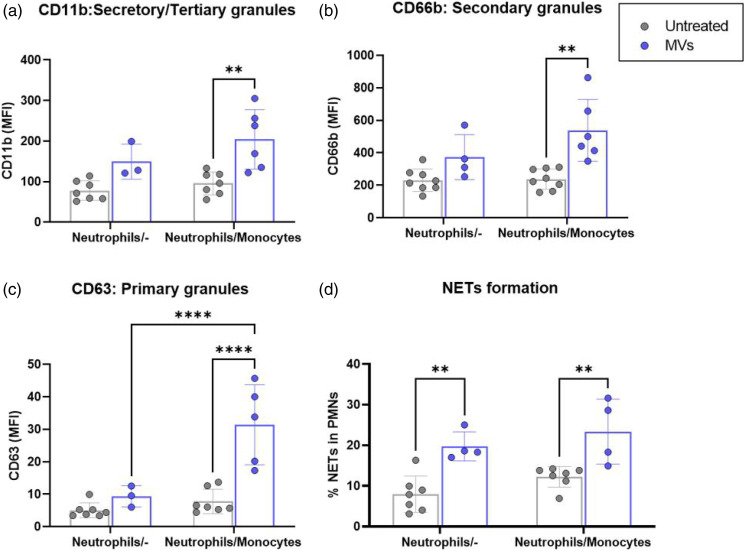

Results: Addition of N-MVs to tri-cultures resulted in significant upregulation of surface activation markers on neutrophils: the tertiary and secretory granule marker, CD11b (Figure 1(a)); the secondary granule marker, CD66b (Figure 1(b)); and the primary granule marker, CD63 (Figure 1(c)). These responses were reduced in the absence of monocytes. By contrast, N-MVs induced increased levels of NETs (Figure 1(d): myeloperoxidase/Sytox-green positive events) independently of monocytes. Monocyte activation by N-MVs was indicated by increased expression of tissue factor compared to untreated controls (MFI: 149.0±23.6 vs. 7.106±2.78, p<0.0001) and production of TNF in tri-culture supernatant (285.4±171.6 vs 1.98±1.64 pg/mL, p<0.01). Lastly, we demonstrated uptake of CFSE-labelled N-MVs by both neutrophils (MFI: 34.5±13.7) and monocytes (MFI: 197.0±177.0). Interestingly, the addition of a blocking anti-CD18 antibody significantly reduced uptake by neutrophils (MFI: 16.6±7.2, p < 0.05), but not by monocytes.

Figure 1.

N-MVs activation of neutrophilis is dependent (a-c) or the presence of monocytes (d). Flow Cytometric values of neutrophil surface activation markers refers to as mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI).The formation of NETs was assessed as the percentage of neutrophils(%) that co-express myleperoxidase (MPO) and Sytox-Green. Data expressed as mean with ± SD and analysed with Two-Way ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison test. n = 3–7, **p<0.01, ****p<0.001. The blue dots represent the addition of N-MVs while grey are the untreated controlls.

Conclusions: We developed a physiologically-relevant tri-culture model to study inflammatory crosstalk between N-MVs with myeloid leukocytes sequestered within pulmonary vasculature during sepsis. We demonstrated that N-MVs are likely taken up by both marginated monocytes and neutrophils within the pulmonary vasculature, and that they are capable of producing significant activation of marginated neutrophils, indirectly via monocyte-dependent mechanisms or directly via induction of NETs. Our results suggest a central role for circulating N-MVs as a strong mediator of acute intravascular inflammation within the lungs, leading ultimately to pulmonary endothelial dysfunction and development of indirect acute lung injury.

Acknowledgements: Funded by NIHR Research Professorship (RP-2015-06-18) and the Chelsea & Westminster Health Charity.

References

1. O’Dea KP, Porter JR, Tirlapur N, Katbeh U, Singh S, Handy JM, Takata M. Circulating microvesicles are elevated acutely following major burns injury and associated with clinical severity. PloS One. 2016;11(12):e0167801.

2. Nieuwland R, Berckmans RJ, McGregor S, Böing AN, Th M. Romijn FP, Westendorp RG, Hack CE, Sturk A. Cellular origin and procoagulant properties of microparticles in meningococcal sepsis. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2000;95(3):930-935.

3. O’Dea KP, Tan YY, Shah S, V Patel B, C Tatham K, Wilson MR, Soni S, Takata M. Monocytes mediate homing of circulating microvesicles to the pulmonary vasculature during low-grade systemic inflammation. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2020;9(1):1706708.

P015

Outcome of prophylactic noninvasive ventilation following planned extubation in high-risk patients: A two year prospective observational study

Adult & Paediatric critical care in low and middle-income countries

Supradip Ghosh1 and Ashutosh Meena 2

1Fortis Escorts Healthcare and Reasearch Centre, Faridabad, Haryana, India

2Imperial Healthcare NHS trust

Abstract

Introduction: Extubation failure (EF) in high risk mechanically ventilated patients is as high as 20-25%,1,2 resulting in increased morbidity, mortality and length of hospital stay. It is more relevant in times of global health pandemic that we look out for the strategies which can potentially reduce the burden on healthcare system. Prophylactic use of Non-Invasive ventilation (NIV) is recommended following extubation in patients at high risk of EF. Most studies2,4 so far have addressed the issue of prophylactic NIV use in setting of Randomized control trials. Therefore, we conducted a prospective cohort study in a real-world scenario looking for the overall impact of prophylactic NIV in patients at high risk of EF.

Objective: Evaluate risk factors and outcome associated with EF in the selected population group.

Material and Method: Consecutive adult patients (≥18 years) admitted in the mixed intensive care unit (ICU) of a tertiary care centre, between January 2018 and December 2019, who passed a spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) following at least 12 hours of invasive mechanical ventilation and put on prophylactic NIV for being at a high risk of EF, were prospectively followed throughout their hospital stay. Extubation failure (EF) was defined as developing respiratory failure within 72 hours post-extubation requiring reintubation or still requiring NIV support at 72 hours post-extubation.

Results: A total of 85 patients were included in the study. 11.8% of patients had extubation failure at 72 hours with an overall reintubation rate of 10.5%. Higher age (p < 0.05), longer duration of invasive ventilation (p < 0.05), and higher sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score at extubation (p < 0.05) were identified as risk factors for extubation failure in univariate analysis. However, in the multivariate analysis, only a higher SOFA score remained statistically significant in forward logistic regression analysis (p < 0.05). We found a clear trend toward worsening organ function score in the extubation failure group in the first 72 hours post-extubation, suggesting extubation failure as a risk factor for organ dysfunction. Cumulative fluid balance was higher both at extubation and in subsequent 3 days postextubation in the failure group, but the differences were not statistically significant. Overall, ICU mortality in the study population was 9.49% and was significantly higher in failure group (50% vs 4%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Higher age, longer duration of invasive ventilation, and higher baseline SOFA score at extubation remain risk factors for extubation failure even in this high-risk subset of patients on prophylactic NIV. Extubation failure is associated with the worsening of organ function. A trend toward higher cumulative fluid balance both at extubation and post-extubation, suggests de-resuscitation as a potentially helpful strategy in preventing extubation failure.

References

1. Thille AW, Boissier F, Ben-Ghezala H, Razazi K, Mekontso-Dessap A, Brun-Buisson C, Brochard L. Easily identified at-risk patients for extubation failure may benefit from noninvasive ventilation: a prospective before-after study. Crit Care. 2016;20:48. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1228-2. PMID: 26926168; PMCID: PMC4770688.

2. Nava S, Gregoretti C, Fanfulla F, Squadrone E, Grassi M, Carlucci A, Beltrame F, Navalesi P. Noninvasive ventilation to prevent respiratory failure after extubation in high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(11):2465-70. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186416.44752.72. PMID: 16276167.

3. Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, Hess D, Hill NS, Nava S, Navalesi P, Antonelli M, Brozek J, Conti G, Ferrer M, Guntupalli K, Jaber S, Keenan S, Mancebo J, Mehta S; Members Of The Steering Committee; Raoof S Members Of The Task Force. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1602426. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02426-2016. PMID: 28860265.

4. Ferrer M, Sellarés J, Valencia M, Carrillo A, Gonzalez G, Badia JR, Nicolas JM, Torres A. Non-invasive ventilation after extubation in hypercapnic patients with chronic respiratory disorders: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 Sep 26;374(9695):1082-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61038-2. Epub 2009 Aug 12. PMID: 19682735.

P016

A review of re-intubations in a mixed general and neurosciences unit and the development of extubation check list

Airway management

Antony Thomas and Juiliana Hamzah

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust

Abstract

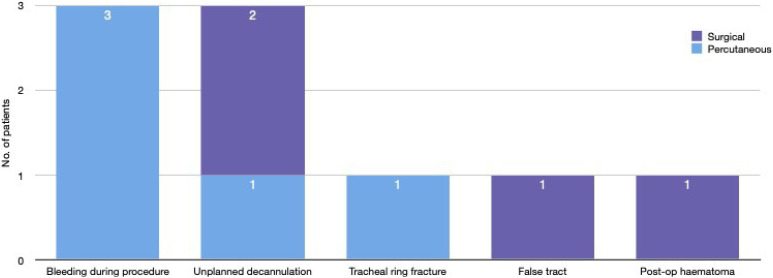

Introduction: Patients who require re-intubation are more likely to have prolonged ICU stays and to die in critical care.1 This may be a particular problem in patients with neurological disease.2

Objectives: To review the electronic intubation records in a mixed general and neurosciences unit to identify reintubations in critical care. To identify patient factors and risk factors associated with re-intubations and to use this information to improve patient care.

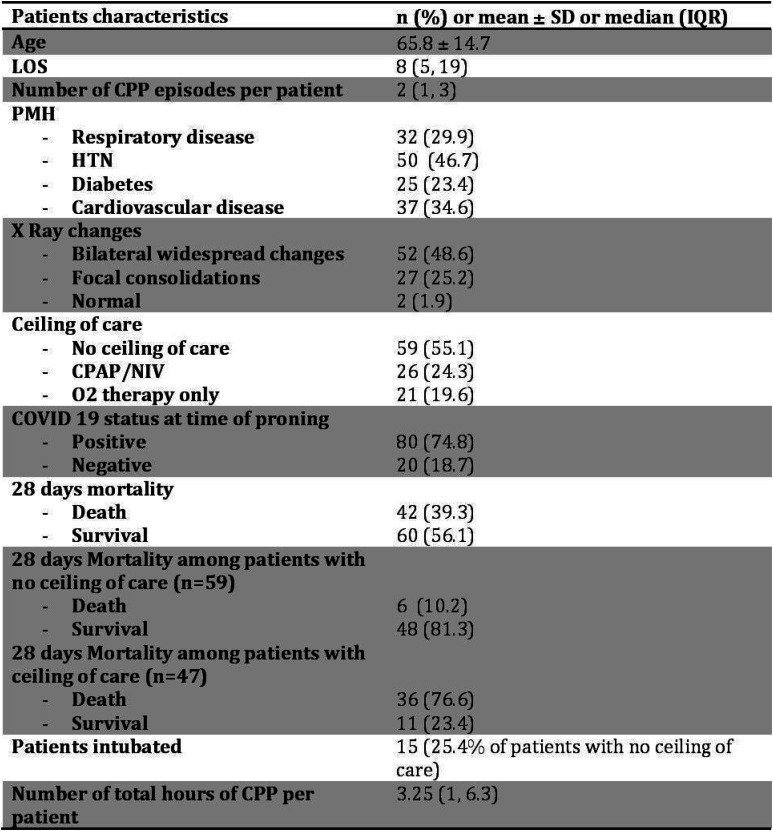

Methods: All intubations are recorded using a structured note on our unit. The records between January 2019 and November 2020 were reviewed together with the patients’ other electronic records. The numbers of critical care intubations per patient were calculated and the reasons for re-intubation were classified. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical data.

Results: There were 3657 admissions for 3164 patients admitted in the study period. 367 (12%) died on the unit and 1525 (48%) had a neurological diagnosis. The mean APACHE 2 score was 11 (SD 6). We identified 455 intubations in 342 patients. Of these 342 patients, 81 (23%) had more than one intubation in critical care (2=53, 3=24, 4=4). Of the 261 patients with single intubation, 81 died (31%) and 136 (52%) had a neurological disease of which 34 (25%) died. The corresponding figures for the 81 patients with multiple intubations were 24 deaths (30%), 39 (48%) had a neurological diagnosis of whom 8 died (21%). None of these findings was significantly different between the single and multiple intubation groups. 154 of the first intubations in critical care were documented as reintubations, having had their primary intubations prior to admission. This gave a total of 256 reintubations (56% of all intubations). Of the reasons for reintubation, 181 (70%) had had a failed trial of extubation (33 of these had signs of laryngeal oedema (27 or 82% female)), 52 had had a tube obstruction or leak and only 10 had self-extubated.

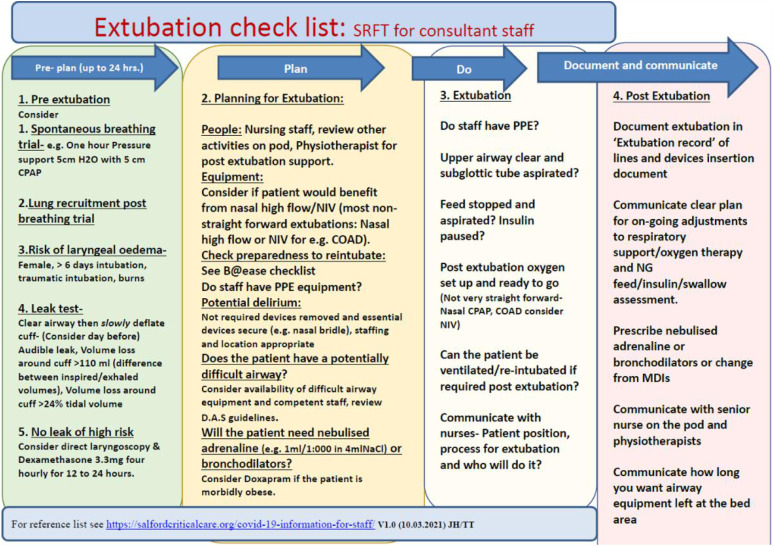

Conclusions: On our unit, there was no difference in the mortality or the number of patients with a neurological diagnosis between patients who had had one or more than one intubation on the unit. Over half of all the intubations on our unit were reintubations, most were associated with trials of extubation. To address this problem, we produced a checklist to facilitate best practices around trials of extubation. This is shown in Figure 1.3

Figure 1.

■■■.

References

1. Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, Apezteguia C, et al. Outcome of reintubated patients after scheduled extubation. J Crit Care. 2011;26(5):502–509.

2. Godet T, Chabanne R, Marin J, et al. Extubation Failure in Brain-injured Patients. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(1):104–114.

P017

Accidental tooth ingestion in the Intensive Care Unit

Airway management

Yap Suhao 1 and Lynn Yeo2

1Ministry of Health Holdings

2National Healthcare Group

Abstract

Introduction: Dislodgement of teeth is not uncommon in anaesthesia and intensive care. This is usually due to airway manipulation during intubation for surgical procedures or resuscitation. Many patients have risks factors for dislodgement of teeth, such as pre-existing dental pathology, poor dentition, restorative dental work and features of a difficult airway.

Objective: To emphasize the importance of dental assessment and maintenance of oral hygiene in the ICU.

Methods: A 67-year-old man, known to have poor dentition and loose teeth, was emergently intubated for low conscious level due to subdural haematoma with mass effect. He underwent burrhole surgery for decompression but remained intubated as he developed pneumocephalus and conscious state did not improve. His upper incisor was noted to be dislodged, 2 days after admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). A search began--direct laryngoscopy, chest X-ray and abdominal X-ray were performed and there was a 1cm calcific density projected over the left abdomen, likely the dislodged tooth. He did not present with any abdominal symptoms of intestinal obstruction or perforation and it was assumed that the tooth had been egested uneventfully after a few days.

Results: Dislodgement of loose teeth or dental prostheses can occur without any signs or symptoms in the critically ill patient. These patients may have low conscious levels or are sedated and intubated so they are not able to communicate to the nursing staff that dislodgement has occurred. If loose teeth or dental prostheses that have been aspirated into the tracheo-bronchial tree chronic lung infections, asthmatic symptoms, lung collapse or lung abscess can develop. These need to be identified and removed as soon as possible, usually be flexible or rigid bronchoscopy as they serve as a nidus of infection. Rarely, open thoracotomy may be required for removal. If the loose teeth are ingested, it typically passes through the digestive system and is expelled in the stool. However, swallowed dentures may lead to hollow viscus necrosis, perforation, fistulae formation, bleeding and obstruction.

In our ICU, there is at least once daily oral toileting for all patients. This is performed more frequently for patients who are on nasogastric feeding or are unconscious. Oral toileting can be done by one of the 2 methods--using a disposable pre-prepared oral swab stick with sodium bicarbonate or with swabs soaked with chlorhexidine 0.2% mouth wash. Any nursing staff can easily carry out this procedure and it includes simple daily inspection for loose teeth, sores, ulcers or thrush.

Conclusion: In the critically ill patient, in whom there are many medical issues to sort out, it is still important to care for the dental health of the patient, to avoid further complications. Basic dental assessment should be performed routinely and regularly by nursing staff, as soon as the patient is stabilized. Adequate training and oral care protocols should be in place. Loose teeth or dental prosthesis should involve a dentist for evaluation and removal.

References

1. Abidia RF. Oral Care in the Intensive Care Unit: A Review. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007;8(1): 076-082.

2. N Yokoo, A Igarashi, M Sato, M Nakane, K Kawamae. Importance of dental assessment in the intensive care unit: two cases of accidental metal crown migration detected by daily routine chest roentgenograms Yamagata Med J 2014: 32(1): 36-39

3. Gachabayov M, Isaev M, Orujova L, Isaev E, Yaskin E, Neronov D. Swallowed dentures: Two cases and a review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4(4):407-413.

4. L Abeysundara, A Creedon, D Soltanifar. Dental knowledge for anaesthetists, BJA Education 2016 16(11): Pages 362–368

5. Khoo Teck Puat Hospital guidelines. (2020). Work Instruction for Oral Hygiene SWI-NURS/INPT-01-03-01

P019

Life-threatening tracheobronchial obstruction with blood clot, managed using whole endotracheal tube suction

Airway management

Neil Roberts, Barney Scrace, Venkat Reddy and Nick Marshall

Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust

Abstract

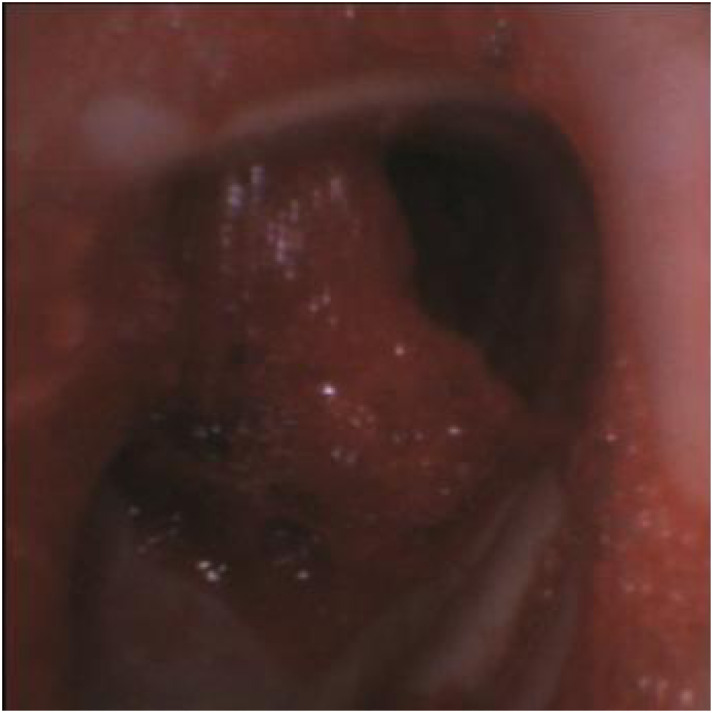

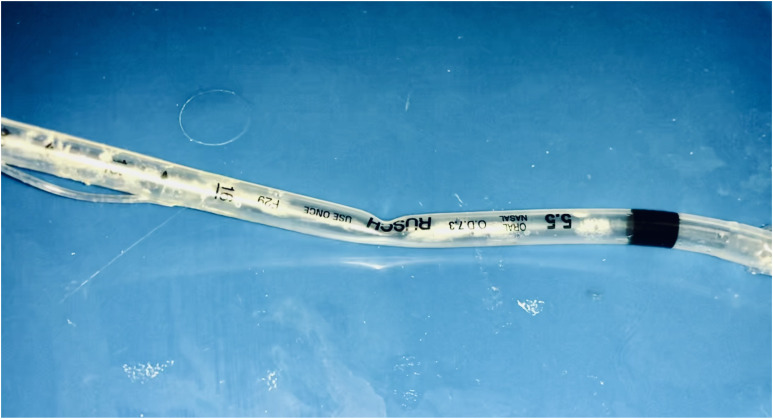

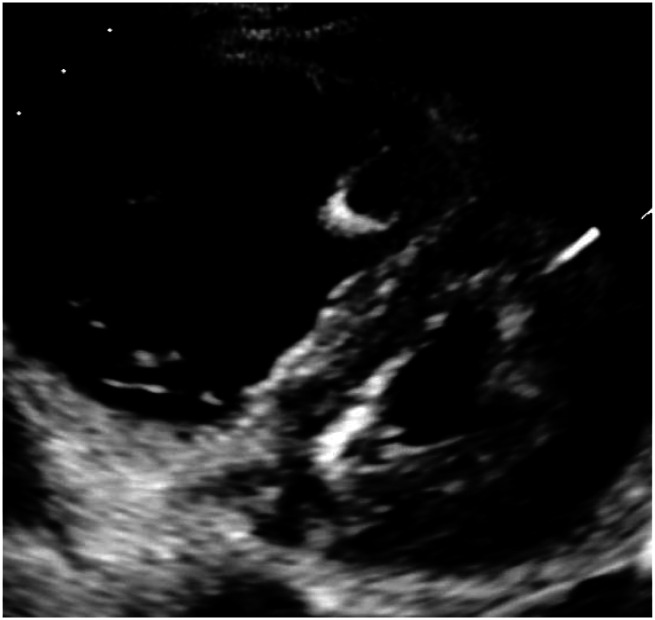

Introduction: Tracheobronchial obstruction due to blood clot after mucosal injury is a rare complication of tracheal instrumentation which may occur during airway surgery (eg tracheostomy), or during a minor procedure such as use of a bougie at intubation. This situation poses several challenges, including potential ongoing bleeding, obstruction of both distal and proximal airways, ball-valve behaviour, and the potential for complete airway occlusion at any stage with subsequent failure of ventilation. We present a case of life-threatening tracheal clot (Image 1) following bougie-facilitated tracheal intubation for a patient undergoing incision and drainage of an abscess.

Image 1.

View of obstructing tracheal clot on fibreoptic bronchoscopy.

Objectives: To describe a novel, life-saving management option for tracheobronchial clot, in the context of previous research.

Methods: A literature search was performed on Pubmed and GoogleScholar using search terms ‘tracheal/tracheobronchial’ ‘obstruction’ ‘blood clot’ ‘mucus plug’ ‘suction’. The authors reviewed this in context of a recent emergency case.

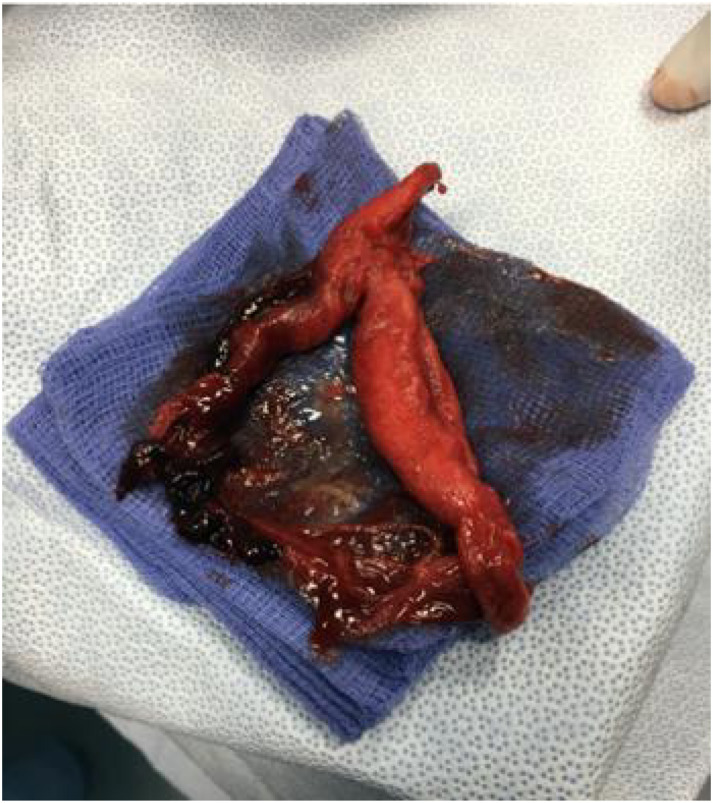

Results: There are several case reports of emergency management of tracheobronchial obstruction, usually either bleeding due to airway injury (for example at tracheostomy), or from large mucus plugs. Most are removable using standard suction catheters, or using suction via fibreoptic bronchoscopy. If this is unsuccessful, rigid bronchoscopy and optical grasping forceps may be indicated. Should all these tactics fail, as in this case, the endotracheal tube may be advanced onto the clot under fibreoptic vision, then connected directly to the suction and removed – along with the complete clot (Image 2).

Image 2.

Clot once retrieved using endotracheal tube as suction device.

Conclusions: The use of whole endotracheal tube suction in life-threatening tracheobronchial clot is a simple technique using standard kit available in all anaesthetic rooms, and may save lives where standard rescue methods fail.

References

1. ■■■

P020

Why can’t we purchase kidneys? A ethical review of presumed consent organ donation compared against a regulated organ marketplace.

Brain death, organ donation and transplantation

Jennifer Lewis

Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Abstract

Introduction: For those living with certain life limiting diseases, an organ transplant is the only option to return to normalcy and a life free of intensive medical investigation and treatment. The demand for organs, notably kidneys is growing internationally and far outstrips the supply available through either deceased or living donors.1 England has recently moved to a presumed consent model for organ donation in part to increase the number of organs available for transplant.2

Objectives: The objective of this research was to examine the likely impact a presumed consent model of organ donation will have on organ donation rates within England. A particular focus was placed on the ethical arguments for an against a model of this type. Alternative organ donation models are possible, a review of the controversial idea of selling organs has also been examined.3,4 The ethics concerning altruism, autonomy and the interplay between economic and health benefits from a utilitarian and Kantian viewpoint will be considered.3,4,5

Methods: This review has been conducted using sources from both medical and philosophical literature.

Results/Conclusion: The presumed consent model of organ donation is unlikely to make a difference to the number of transplants conducted in England.3 Although its efficacy as a project cannot be exclusively measured in terms of successful organ donation. The engagement of key stakeholders and importantly the general public in the discourse surrounding organ donation is vital, a change in organ donation law should initiate this process. In comparison the controversial idea of selling organs is a more efficacious way of increasing the number of organs available for donation. A black-market for organs (which currently exists in many countries) violates human rights, allows for exploitation and the undermines the sanctity of human life,4 however commercialisation does not necessarily result in exploitation if the marketplace is carefully controlled and governed. The review will conclude with a proposal for an independent regulator for the sale of organs, which will be both transparent, economically viable and ultimately save more lives.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014: World Health Organization; 2014.

2. NHS Blood and Transplant. What can you donate? https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/helping-you-to-decide/about-organ-donation/what-can-you-donate/n.d

3. Cohen C. The case for presumed consent to transplant human organs after death. Transplant Proc. 1992;24(5):2168-2172.

4. Orentlicher D. Financial incentives for organ procurement: Ethical aspects of future contracts for cadaveric donors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155(6):581-589.

5. Alpinar-Sencan Z. Reconsidering Kantian arguments against organ selling. Medicine, health care, and philosophy. 2016;19(1):21-31.

P021

Cause of death and consent rates during the COVID-19 pandemic

Brain death, organ donation and transplantation

Nicholas Plummer 1 , Harry Alcock 1 , Susanna Madden2, Alex Manara2, Dan Harvey2, Dale Gardiner2

1Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

2NHS Blood and Transplant

Abstract

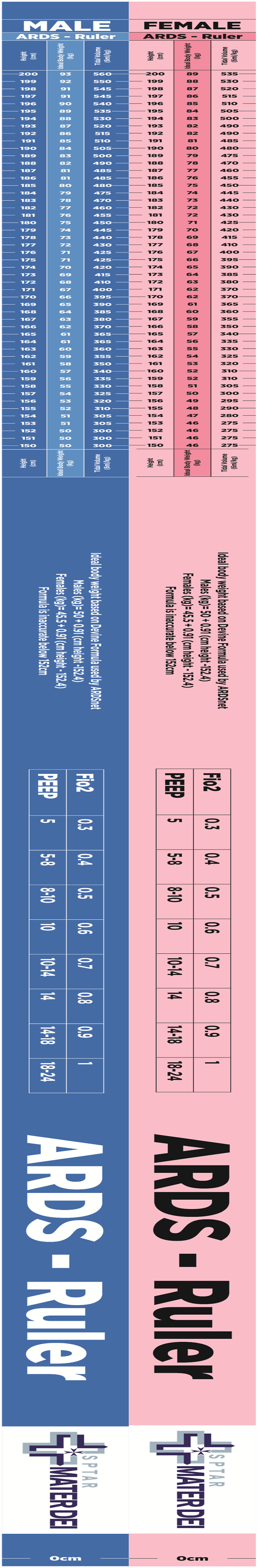

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-21 impacted all aspects of the UK health service. Organ donation acceptance criteria were initially revised to safeguard critical care resources, and prioritised younger donors and donation after brain death (DBD) over donation after circulatory death (DCD).1 These were later returned to the original criteria prior to the “second wave” in September 2020; yet referrals and donation numbers remained below pre-pandemic levels throughout 2020. This data was further confounded by England changing from an opt-in model to presumed consent for donation.2

Objectives: We aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on causes of death, and the subsequent effect on numbers of potential donors, referral rates (adjusted for the altered referral criteria during the first wave), and consent rates for donation.

Methods: Mortality, referral, and consent rate data were acquired from the Potential Donor Audit (PDA) database held by NHS Blood and Transplant. The two pandemic “waves” (defined as 11/3/2020-10/08/2020 and 11/08/2020-10/03/2021) were compared to their corresponding periods from 2019-20. Event counts were compared using exact Poisson tests, and proportions using two-sample z-tests.

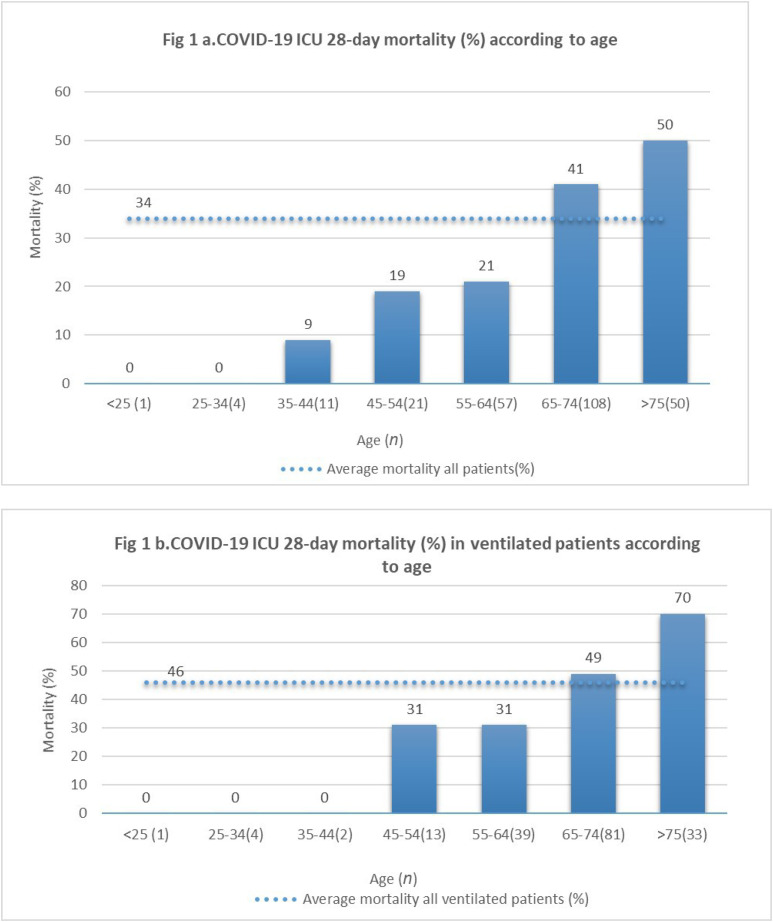

Results:

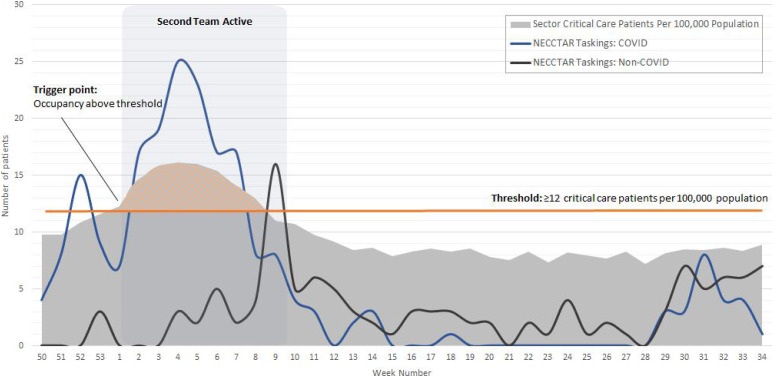

All-cause mortality was higher during both “waves” (p<0.001) than the previous year, with excess in-ICU non-COVID-19 mortality during the second wave (p=0.024, see figure). Mortality from cardiac arrest (p<0.001), catastrophic brain injury (p<0.001), and head trauma (p=0.280) were reduced in both waves, and deaths in ICU from suicide and self-harm were reduced in the second wave (p=0.002).

After accounting for COVID-19 positive patients and those outside of the adjusted age-criteria, there was no difference in referral rates for potential DBD patients (99% in all cases) but fewer DCD patients meeting criteria were referred during both waves (89% vs 93%, p=0.003, and 85% vs 92%, p<0.001).

There were fewer eligible donors during both waves (p<0.001). Fewer eligible families were approached during the first wave (42% vs 58%, p<0.001) but more were approached during the second (58% vs 54%, p=0.001) than in the preceding twelve months. There was no significant difference in Specialist Nurse in Organ Donation (SNOD) presence during approaches, nor family consent rates. Additionally, there was no difference in the proportion of patients who subsequently went on to donate.

Conclusions: The reduction in donations – and hence transplantation – during the COVID-19 pandemic was multifactorial. There was a significant reduction in causes of mortality that are most associated with donation, likely driven by an increased number of deaths in the community who never ‘made it’ to hospital. Potential DCDs were referred less frequently during both waves, although this was secondary to the change in acceptance criteria during the first wave. Additionally, fewer eligible families were approached during the first wave, further reducing donation potential.

Despite fewer eligible donors, consent rates, the relationship between SNOD presence and consent, and progression to donation remained unchanged, suggesting that the foundations underpinning the organ donation programme remained resilient.

Future work should focus on validating factors predicting family consent3 in the context of COVID-19 and assessing the ongoing impact of presumed consent.

References

1. NHS Blood and Transplant. COVID-19 Planning for Infection Surges. NHS Blood and Transplant; 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/21165/pol301.pdf

2. Gardiner D, McGee A, Shaw D. Two fundamental ethical and legal rules for deceased organ donation. BJA Education. 2021;21(8):292-299. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2021.03.003

3. Curtis RMK, Manara AR, Madden S, et al. Validation of the factors influencing family consent for organ donation in the UK. Anaesthesia. Online first. doi:10.1111/anae.15485

P022

Organ donation rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparing the approach taken during the first two waves

Brain death, organ donation and transplantation

Nicholas Plummer 1 , Harry Alcock 1 , Susanna Madden2, Alex Manara2, Dan Harvey2 and Dale Gardiner2

1Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

2NHS Blood and Transplant

Abstract

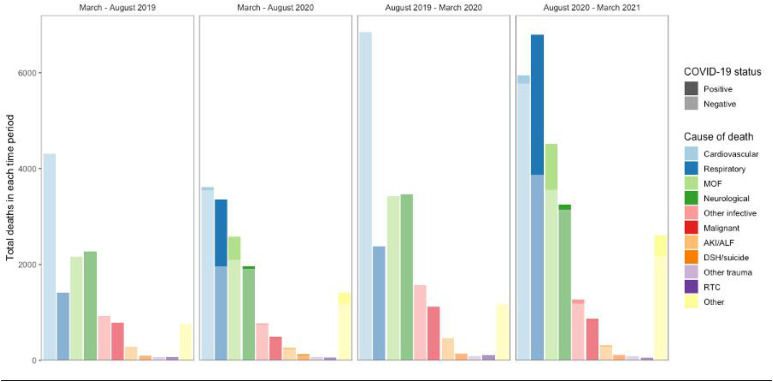

Introduction: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic the many UK transplant units had to close or reduce activity, with deceased donation and transplantation down 80% in March-May 2020. Donor age criteria were reduced in the “first wave” to protect ICU capacity, and donation after brain death (DBD) was prioritised over donation after cardiac death (DCD). From June onwards, an NHSBT recovery plan aimed to reopen programmes, with the aim to return to a position of exploring all eligible donors and reviewing their potential on a case-by-case basis,1 but the ability of such programmes was impacted by a further rise in COVID-19 cases (“second wave”).

Objectives: We aimed to compare the performance of NHSBT referral, donation, and transplantation strategies during the first two “waves” of COVID-19. Wave one was defined as 11/3/20 to 10/8/20, and wave two 11/8/20 to 10/3/21.

Methods: Mortality and transplant data were acquired from the Potential Donor Audit (PDA) and national transplant registries. COVID-19 healthcare utilisation data was acquired via the PHE API. Correlation between features were assessed using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient and means compared using Student’s t-test.

Results:

Weekly referral rates during the first wave were strongly inversely correlated to COVID-19 critical care utilisation (r=-0.82, 95%CI -.93 to -0.60) but moderately positively correlated during the second (r=0.61, 95%CI 0.31 to 0.80). Total transplanted organs were inversely correlated throughout (r=-0.64, 95%CI -0.78 to -0.44) with no difference between waves (p=0.055), although renal transplants were less effected during the second wave (p<0.001).

The mean “transplant gap” (difference between organs retrieved and transplanted) was significantly higher in the second wave (5.9 per week, 95%CI 3.4 to 8.5, p<0.001). The DBD/DCD ratio was significantly lower in the second wave (reduced from 3.3 to 2.0, 95%CI for reduction 0.5-2.1, p=0.001).

Conclusion: Referral rates to NHSBT improved during the second wave, and the ratio of DBD to DCD fell, both reflecting positively on the change of approach taken. Although total organ transplants fell during both waves, this is strongly correlated to critical care utilisation by COVID-19 patients, suggesting an impact on the ability for transplant centres to access critical care resources post-operatively. The relative sparing of renal transplants (who rarely require critical care post-operatively) and increasing transplant gap in the second wave fits with this assessment, although concerns regarding risks of COVID-19 in transplant recipients - especially in renal patients2- during periods of high burden of disease in hospital likely also contributed to reduced transplant rates,3 and the higher transplant gap could additionally be associated with the increase in DCD donation during the second wave.4

References

1. NHS Blood and Transplant. COVID-19 Planning for Infection Surges. NHS Blood and Transplant; 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/21165/pol301.pdf

2. Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, et al. Covid-19 and Kidney Transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(25):2475-2477. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2011117

3. Ravanan R, Callaghan CJ, Mumford L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and early mortality of waitlisted and solid organ transplant recipients in England: A national cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(11):3008-3018. doi:10.1111/ajt.16247

4. Manara AR, Murphy PG, O’Callaghan G. Donation after circulatory death. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(Suppl 1). 108-121. doi:10.1093/bja/aer357

P023

Retrospective review of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Post-resuscitation care pathway drives improved patient survival

Cardiac arrest

Shambavi Vettikumaran, Shona Johnson, Suzanne Maton, Liza Keating, William Orr and Tracey Realey

Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust

Abstract

Introduction: In England, overall, around 9% of patients who undergo an OOHCA survive to hospital discharge. Post-resuscitation care remains the least well-defined component of the crucial ‘chain of survival’ and was a focus of the 2013 Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes Strategy. At the RBH we have collaborated across teams with the emergency medical services (EMS), emergency department (ED), cardiology and critical care working to improve outcomes and ensure the right patients undergo timely angiography and percutaneous intervention (PCI) with subsequent admission to critical care.

In 2016, we analysed 3428 patients with OOHCA presenting to the RBH between October 2012 and May 2015 and established a local OOHCA protocol in collaboration with EMS, ED, interventional cardiology and critical care and demonstrated better than expected survival to hospital discharge at 19.5%.

Objectives: The aim of this review was to ascertain if the currently observed outcomes, which were previously better than expected at 19.5%, have been maintained.

Methods: We undertook a retrospective chart review of EMS data, ED records, Myocardial ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) and Trust coding data from 2018 to 2021. We identified 5785 adult patients with spontaneous OOHCA in which cardiopulmonary resuscitation was commenced or continued by EMS. Outcomes for the RBH were compared to current national statistics and to our previous 2012- 2015 data. A chi-squared test to evaluate comparison of proportions was used.

Results: Overall, locally 21.7% of patients with an OOHCA survived to discharge compared to 9.1% for England (P <0.0001). A greater proportion than in the previous audit (32.6% vs 22%) underwent coronary intervention. Although survival to hospital discharge in those undergoing PCI was lower in 2018 – 2021 at 51.5% compared to 62.4% in 2012 – 2015.

Conclusions: High survival rates at the RBH have been maintained for all patients admitted to critical care following an OOH CA compared to the national average with a greater proportion undergoing coronary intervention.

References

1. Cardiovascular disease outcomes strategy (DoH 2013) MedCalc Software Ltd. Comparison of proportions calculator. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/comparison_of_proportions.php (Version 20; accessed May 28, 2021)

2. G. D. Perkins, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Executive summary, Resuscitation (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.003

3. Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes Registry. www.warwick.ac.uk/go/ohcao

4. G. D. Perkins, et al. (2021) Epidemiology of cardiac arrest Guidelines. Retrieved from: https://www.resus.org.uk/library/2021-resuscitation-guidelines/epidemiology-cardiac-arrest-guidelines#references

P024

Prophylactic antibiotic use in post-arrest care

Cardiac arrest

Charlie Dunmore and Eoghan O’Callaghan

Aintree University Hospital

Abstract

Introduction: Despite significant advances in post-ROSC care, survival following an Out Of Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OOHCA) remains poor. Targeted temperature management is accepted practice in optimising survival and neurological recovery following admission to Critical Care, despite suggested increased risks of VAP. An increasing evidence-base suggests prophylactic antibiotics within 12 hours of admission can reduce the incidence of early-onset VAP and could lead to shorter ICU/hospital stays.1 This project looks into how our unit complies with this and examines the relevance in the ICU setting.

Methods: Retrospective analysis was conducted on routine patient data for all adults admitted to our ICU, based at a large tertiary centre teaching hospital, following an OOHCA with ROSC. This data was collected during the periods of September 2019-20 and November 2019-2020 respectively. Data collected included age, Arctic Sun use, positive sputum cultures within five days of admission, ventilator hours, ICU/hospital days and overall survival outcomes. A departmental guideline outlining post-arrest management including prophylactic antibiotics was published in March 2019 and was available to all staff on the local intranet.

Results: Average age was 55. Our re-audit data showed that 87% of our patients were started on prophylactic antibiotics from day one of admission, an improvement from 84% the previous year. Data gathered in the most recent cycle demonstrated that the Arctic Sun was documented as being utilised in only 40.9%, on average seven hours into their admission. 29% grew at least one potentially pathogenic organism in their sputum in the first five days, with two more patients colonising shortly beyond this period. Average daily CPIS trended upwards from 1.84 on day one, to 2.67 on day five. 40.9% survived to hospital discharge, spending an average of 86.26 hours on a ventilator, six days of their admission on ICU and 14.7 total days in hospital.

Discussion: The majority of our patients are started on prophylactic antibiotics on admission, although this aspect of the bundle appears to be less strictly adhered to, possibly because of varying opinions amongst clinicians. A significant proportion of ventilated patients grew potentially harmful organisms, which alongside raised CPIS supports a high incidence of VAP. Similar results were seen in both cycles, supporting the use of a short course of antibiotics for these patients.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the ICU audit department at Aintree University Hospital.

References

1. François B, Cariou A, Clere-Jehl R, et al. Prevention of Early Ventillator-Associated Pneumonia after Cardiac Arrest. New England Journal of Medicine 2019; 381:1831-1842

P025

Levosimendan within critical care. Coronary stenting verses no coronary stenting: an observational study

Cardiovascular monitoring

Gemma Millen, Lucy Cooper and Mark Snazelle

East Kent Hospital University Foundation Trust

Abstract

Introduction: Levosimendan acts as a vasodilator opening ATP-sensitive potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle, increasing myocardial oxygen supply, and reducing preload and afterload. It protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury and activating stunned myocardium in patients following cardiac intervention.1

An Observational Study was designed to review the impact of Levosimendan in the first 24 hours of treatment by measuring Cardiac Index (CI). This data was collected in a district general hospital which offers primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Objectives: To observe the impact of Levosimendan on CI during cardiogenic shock in patients who received coronary stenting vs no coronary stenting.

Methods: Patients requiring Levosimendan, due to cariogenic shock, were observed over an 8 year period. These patients were subject to inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| >18yrs old | Patients unlikely to survive >24hrs |

| Myocardial stunning with decreased organ perfusion | un-correctable medical conditions |

| Ejection Fraction <35% or regional wall abnormalities | Right heart failure due to pulmonary embolus |

| CI <2.5L/min/m² or dobutamine up to 10mcg/kg/min | High output failure due to thyrotoxicosis, arrhythmias, anaemia or massive blood loss |

| hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | |

| uncorrected stenotic valve disease in patients with no definite procedure planned. |

CI studies were performed on onset of Levosimendan, 12 hours and 24 hours from initiation.

Results: Manual data of 71 patients with a median age of 62 years. The male to female ratio was 76% vs 21% and the average organ support for the patients consisted of three organs

| Reason for admission | No of patients |

|---|---|

| Cardiac Arrest | 41 |

| STEMI | 22 |

| NSTEMI | 4 |

| OTHER (Sepsis) | 4 |

The patients were then observed for changes in CI at onset, 12hour and 24hour post Levosimendan infusion, in three groups;

| Group A | Patients receiving coronary stenting |

| Group B | Patient who didn’t receive coronary stenting |

| Group C | Septic Patients not assessed for coronary stenting |

| APACHE II Score | |

| ALL GROUPS | 18.5 |

| Group A | 19.5 |

| Group B | 16.5 |

| Group C | 17 |

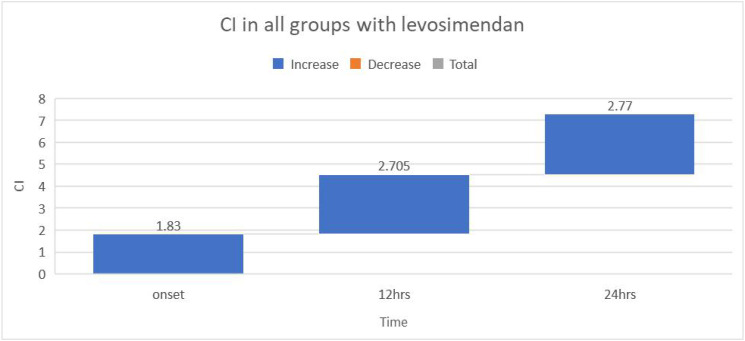

The overall CI in all patients improved from onset to 24hrs of commencement of Levosimendan from a median CI of 1.83L/min/min² to 2.77L/min/m²

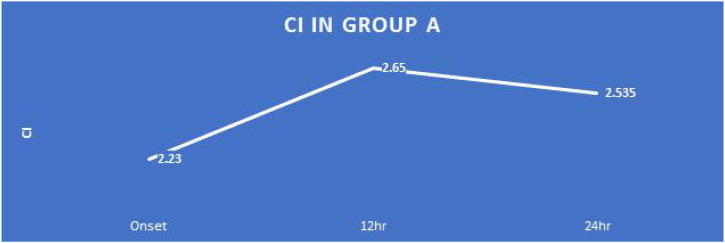

The patients’ CI in Group A, improved overall from onset of 2.23L/min/m² to 24 hour CI of 2.535L/min/m², however the CI at 12hrs was most improved to 2.65L/min/m². The overall mortality for this group of patients was 58%.

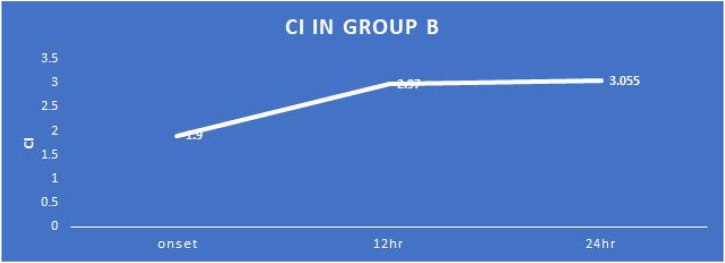

Patients in Group B show a consistenly improved median CI over the 24hrs from a CI of 1.9L/min/m² to 3.055L/min/m². The overall mortality for this group was 39%.

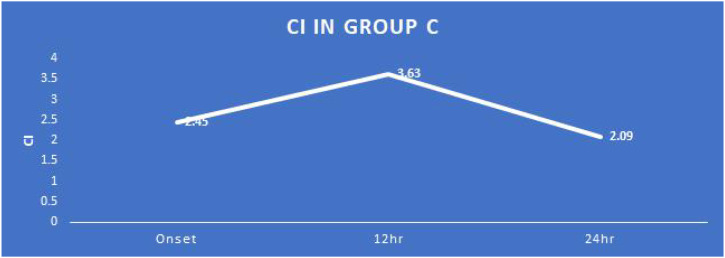

The data collected for patients in Group C is comparatively small and may well be excluded for this, however, the data showed a varying CI of onset 2.45L/min/m² to 2.09L/min/m². All the patients survived in this group.

Conclusion: The observational data for all three groups shows an overall improvement in CI, however there are some variations. Overall mortality of patients in Group B are improved from Group A, however the sample size and severity scoring is markedly different between the groups. APACHE II scores were higher in Group A, predicting a worse mortality. By definition, the patient groups being discussed have very high mortality and so isolation of the true benefit of Levosimendan will only be possible with large sample size.2 We postulate that due to cost, Levosimendan may be used too late. Further study into timing of administration of Levosimendan use in post coronary intervention group and use as first line therapy is warranted. We suggest future randomised controlled trials with larger patient groups, closer observation of the demographic data, severity scores, timing, administration and other variables. This would provide further evidence base to compare Levosimendan use verses standard therapy.

References

1. Manakers. Use of Vasopressors and Inotropes. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-vasopressors-and-inotropes?search=use%20of%20vasopressors%20and%20inotropes&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1∼150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (accessed 06/08/2021).

2. Brookes L, et al. REVIVE II and SURVIVE: Use of levosimendan for the treatment of acute decompensated heart failure. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/523043 (accessed 08/08/2021).

P026

Unusual case of BRASH syndrome precipitated by atrial fibrillation with a fast ventricular response

Cardiovascular monitoring

Luke Western 1 , Jessica Bialan2 and Benjamin Millette 3

1Oxford University Hospitals

2King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

3Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust

Abstract

Introduction: BRASH syndrome is a recently described clinical syndrome consisting of bradycardia, renal failure, atrioventricular (AV) nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalaemia. It often arises from initial renal injury, causing an accumulation of AV nodal blocking medication and potassium. This induces bradycardia which contributes to a cardiogenic shock. This further injures the kidney in a vicious circle of pathology.1

BRASH syndrome justifies its definition as a distinct clinical entity as prognosis and management differ significantly from routine adult life support algorithms, and temporary transvenous cardiac pacing can be avoided with appropriate critical care management. It is considered a largely underdiagnosed entity.1

Objectives: We present a case of BRASH syndrome preceded by fast atrial fibrillation (AF). This complicated the clinical picture, and this case is discussed to increase awareness of the syndrome and promote timely identification and management.

Methods: We detail the clinical context and management of a patient with BRASH syndrome and discuss relevant literature.

Results: A 60-year-old gentleman presented with worsening shortness of breath over one week and unremarkable blood results. ECG revealed AF with a ventricular rate of 140 which didn’t respond to 10mg Bisoprolol and the team proceeded to DC cardioversion. Within two hours of cardioversion, he became haemodynamically unstable (systolic 80mmhg, heart rate 32) despite fluid resuscitation. He became oliguric and a refractory hyperkalaemia of 7.2 was noted. He developed new right bundle branch block and significant impairment in left ventricular function on echocardiography.

Temporary pacing was considered, however, BRASH was identified as a differential and following admission to the intensive care unit for haemofiltration and inotropic support with isoprenaline, he improved rapidly. Haemofiltration likely reduced the hyperkalaemia and beta-blocker in circulation and broke the BRASH syndrome cycle.1,2 He recovered to his baseline over the following three weeks on the cardiovascular ward and was discharged home.

Conclusions: It is very likely that AF with a fast ventricular response contributed to the precipitation of BRASH syndrome. Furthermore, DC cardioversion resulted in the rapid deterioration due to high doses of long-acting beta-blocker administered prior to the procedure. Early discussion of BRASH syndrome allowed the team to avoid unnecessary temporary transvenous pacing and proceeding with haemofiltration and inotropic therapy.

We recommend awareness of BRASH syndrome as a potential complication of cardioversion of acutely decompensated AF patients and be aware of the risks of high doses of long-acting AV blockers in those vulnerable to accumulation.

References

1. Farkas JD, et al. BRASH Syndrome: Bradycardia, Renal Failure, AV Blockade, Shock, and Hyperkalemia. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 2020;59:216–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.05.001.

2. Tieu A, et al. Beta-Blocker Dialyzability in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. CJASN 2018;13:604–611. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.07470717.

P027

The role of a family communications team in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic

Communication

Jasmin Ranu 1 and David Hepburn2

1Cardiff University

2Grange University Hospital

Abstract

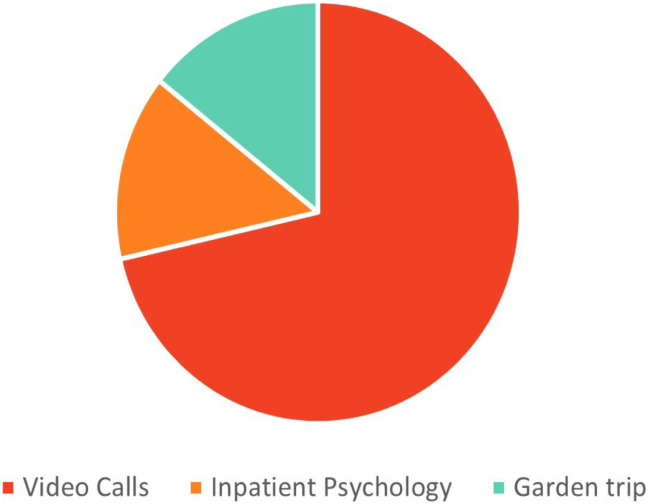

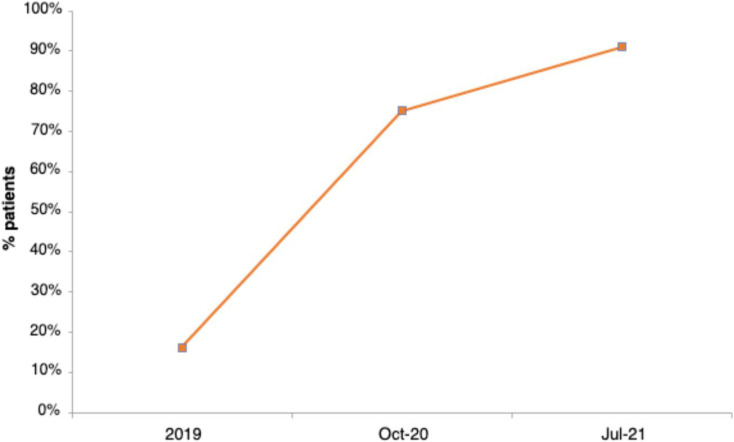

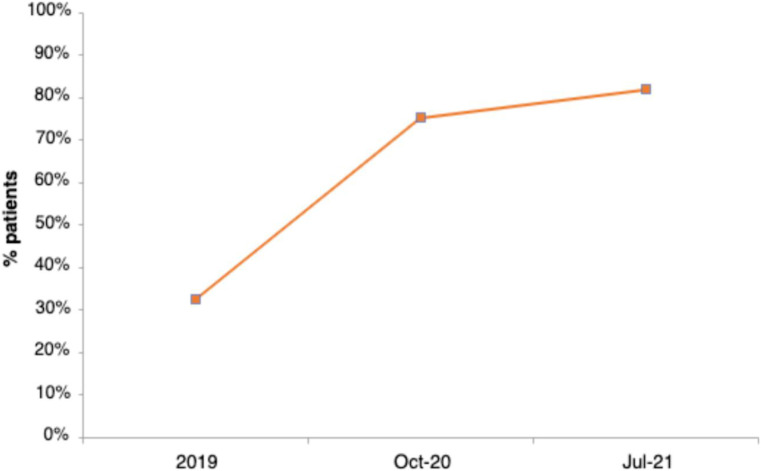

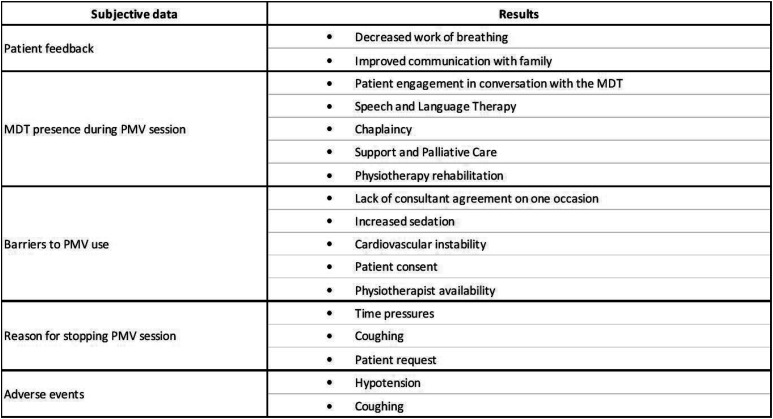

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has added pressures onto Intensive Care Units (ICUs), including family visiting being commonly restricted to end of life.1,2 ICU care is based on adopting a patient and family-centred approach.3,4 To continue providing care in this way, many ICUs across the UK began initiating daily phone calls with families,1 or developing a dedicated family liaison team.1,2 The Aneurin Bevan University Health Board created a dedicated family communications team (FCT), originally split across two hospitals and later combined after the ICUs were merged. The medical team would handover to the FCT daily, who would call patient’s families to update them on their clinical picture and future plans.

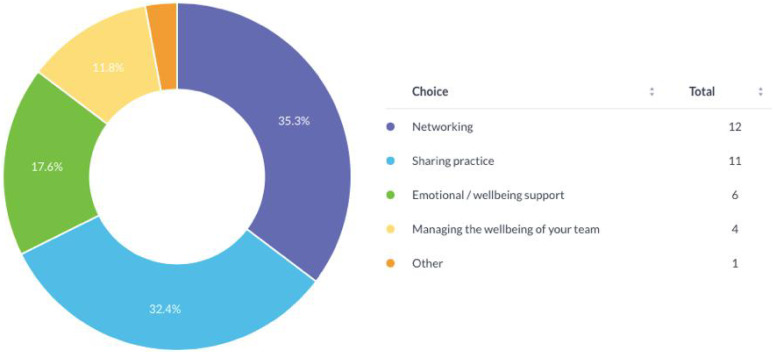

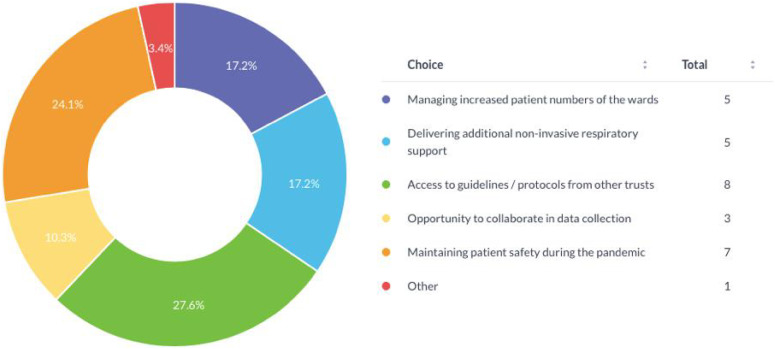

Objectives: To explore family perceptions of the FCT throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: A telephone questionnaire was created and retrospectively completed by families of patients admitted to ICU between November 2020 and May 2021. Families of patients who had since died were excluded. Families were randomly selected to allow for a distribution of participants across the study period. Data was added to that previously collected from the first wave within the health board to compare the general satisfaction of the FCT and analysed to look for strengths and weaknesses.

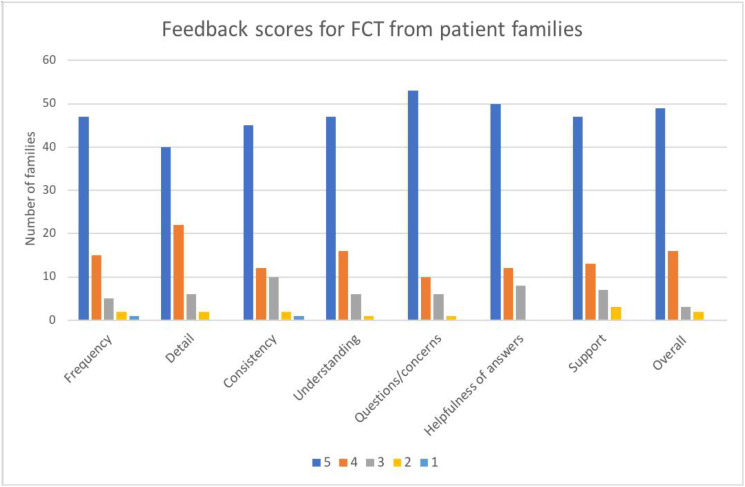

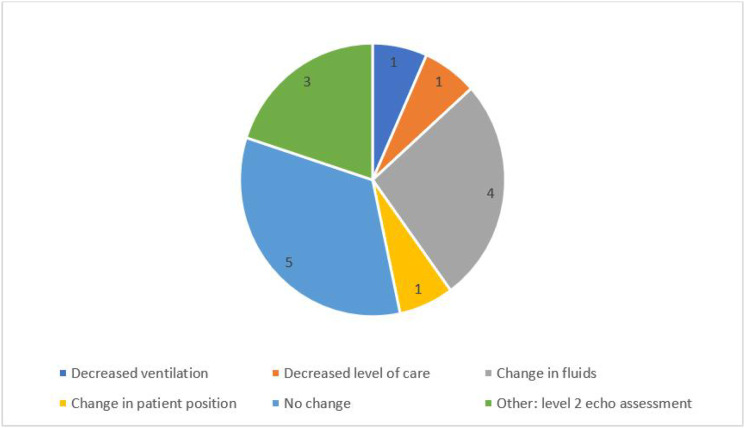

Results: The responses of 44 families of patients were added to the 26 previously collected – resulting in 70 family participants. The majority of responses to each question were scored at the maximum (figure 1). Of the 70 families, 65 (92.9%) rated the FCT overall as a 4 or 5 out of 5. There was little difference in satisfaction rates between the two hospitals (average overall score 4.73 vs 4.52 in wave 1 and 2 of the pandemic respectively), nor was there a change in satisfaction of the service over time.

Conclusions: The FCT received a fundamentally positive response, with majority of families scoring the service at the maximum across each domain measured. This study suggests that a dedicated FCT may have a role in the future of ICUs, both if visiting were to be restricted again in the future, or as a new normal.

Figure 1.

■■■.

References

1. Boulton AJ, Jordan H, Adams CE, et al. Intensive care unit visiting and family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK survey. J Intensive Care Soc Epub ahead of print 6 April 2021. DOI: 10.1177/17511437211007779.

2. Rose L, Yu L, Casey J, et al. Communication and Virtual Visiting for Families of Patients in Intensive Care during COVID-19: A UK National Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc Epub ahead of print 22 February 2021. DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202012-1500OC.

3. Mitchell ML, Coyer F, Kean S, et al. Patient, family-centred care interventions within the adult ICU setting: an integrative review. Aust Crit Care 2016; 29(4): 179-193.

4. Van Mol MM, Boeter TG, Verharen L, et al. Patient- and family-centred care in the intensive care unit: a challenge in the daily practice of healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26(19-20): 3212-3223.

P028

The infodemic in the pandemic: improving multidisciplinary ICU communication and responsiveness using QR code feedback

Communication

Brendan Spooner 1 , Emma Sherry2, Aimee Yonan2, Fahad Zahid2, Faisal Baig2, Martin LeBreuilly2, David Balthazor2 and Louisa Murphy2

1University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire

2UHB

Abstract

Introduction: During this pandemic our email inboxes, social media, general news and work meetings have become saturated with new information, guidelines, protocols and practices all subject to constant amendment. It has become an infodemic. This constant stream has caused cognitive fatigue to a workforce that is under severe pressure.1 Nonetheless, there is a need to report relevant information to the frontline on ICU in a timely and digestible way. It is also especially important for staff feedback to be assimilated rapidly. Therefore, having an agile communication strategy for the ICU workforce has never been more important.

Objectives: To introduce a communication and feedback strategy that met the needs of the evolving MDT workforce during the pandemic.

Methods: A multidisciplinary project team was assembled. The project had two arms – communication and feedback.

There was a need for an agile communication strategy for COVID ICU updates including to those re-deployed staff members. The aim was to achieve a suitable balance of relevant information without overwhelming colleagues with multiple daily emails. The group chose a weekly 1-page infographic poster that could easily be displayed, emailed and communicated via WhatsApp groups (see Figure 1). Update information was collated from multiple sources and distilled into a single page that was easy and quick to read.

Figure 1.

Example infographic.

Rapid feedback was collated from a QR code displayed in ICU rest areas, a suggestion/feedback box located next to the ICU and a dedicated email address. This information was fed to relevant stakeholders for them to act on to improve care, working practices and staff wellbeing.

Results: A pre-implementation survey of 31 multidisciplinary ICU staff members suggested staff felt very uninformed and uncertain about COVID ICU practice. From October 2020, 19 weekly updates were produced (until the end of the second wave). They were distributed to over 400 staff members and were widely shared amongst WhatsApp groups. They were displayed in 24 locations across critical care. As the processed matured colleagues would approach the project team with relevant updates that they wished to publicise. The team processed 137 pieces of feedback about a wide variety of issues on the ICU. Many were acted on for improvements. Other areas of the organisation adopted the QR code feedback strategy.

Feedback on the strategy has been excellent with 100% of those who saw the infographic finding it useful and staff felt more informed (post implementation survey of 29 colleagues). There were however several big challenges. Many of the issues raised via feedback were not within the gift of the project team to address. The rapidly changing and expanding workforce was hard to access.

Conclusion: Rapidly implementing a multidisciplinary digital communication and feedback strategy was possible during the pandemic. Results suggest it improved colleagues’ perception of being informed during the rapid changes that were necessary during the pandemic. The simplicity of QR code feedback generated much scope for improvement.

References

1. Kearsley R and Duffy CC. The COVID-19 information pandemic: how have we managed the surge? Anaesthesia 2020; 75: 993-996.

P029

Ready to talk? Evaluation of confidence in end-of-life communication among intensive care nurses

Communication

Jane Whitehorn 1 , Stephanie Cronin2, Kirsty Boyd3, Michelle McCool2, Susan Somerville2, Natalie Pattision4, Nazir Lone5 and Janine Wilson2

1Edinburgh Napier University

2NHS Lothian

3Edinburgh University

4University of Hertfordshire/East & North Herts NHS Trust

5NHS Lothian/Edinburgh University

Abstract

Introduction: Over 45,000 people receive critical care in Scotland annually and more than 12% of those admitted to intensive care die on the unit.1 Death of a family member in critical care leads to complicated grief in up to 52% of relatives.2 Caring for dying patients and their families contributes to burnout in up to 51% of team members.3 Clear, honest, and timely communication by the multidisciplinary team can help mitigate these adverse outcomes. However, the role of nurses in end-of-life (EOL) conversations can be unclear and passive.4

Objectives: To explore confidence in communication around EOL care among intensive care nurses and identify unmet educational needs.

Methods: Registered nursing staff of a 40 bedded, general ICU/HDU in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh completed an anonymous online survey during spring 2021 to assess their confidence in communication around EOL care, to explore the nature of EOL conversations, and identify key topics for further education. The survey was adapted from a validated tool5 designed to assess the level of knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and confidence of staff providing palliative care. No ethical approval was required.

Results: 32% (n=77) of invited ICU nurses responded to the survey. The majority of respondents were involved in EOL conversations on at least a monthly basis (58%, n=45). Over the previous 6 months, 81% (n=62) of nurses were involved in planned EOL discussions with patients/families whilst 71% (n=55) had taken part in impromptu conversations. Both planned and spontaneous EOL discussions were initiated by an ICU consultant more than twice as often as the patient’s nurse (planned n=57 vs 20, spontaneous n=37 vs 15). Among nurses with two or under years of experience in ICU, only 10% had initiated an EOL conversation with patients or their families in the previous six months.

31% of respondents were unsure or unconfident in their ability to speak with patients about death and dying and 21% felt similarly about talking with family members.

Only 22% of nurses said that they had received undergraduate training in EOL communication, whilst 40% had received postgraduate training. Further education in EOL care was requested by 99% of respondents, with the most required topics including communication relating to organ donation (n=49) and sharing bad news with patients and families (n=33).

Discussion: This study showed the significant involvement of ICU nurses in EOL communication. It highlighted the need for more undergraduate and postgraduate education in EOL communication and inclusion of critical care specific content. Improved education could increase nurses’ confidence and build a stronger multidisciplinary team approach to EOL communication. Better support for nurses in their role could decrease staff burnout. More effective and timely EOL communication may reduce the risk of complicated grief experienced by family members and promote better patient and family centred care.

References

1. Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group. Public Health Scotland. Audit of critical care in Scotland 2020 reporting on 2019. 2020. Available from: https://www.sicsag.scot.nhs.uk/Publications/_docs/2020-08-11-SICSAG-report.pdf?1

2. Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, Lefrant JY, Floccard B, Renault A, Vinatier I, Mathonnet A. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;45(5):1341-1352. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00160014

3. Malaquin S, Mahjoub Y, Musi A, Zogheib E, Salomon A, Guilbart M, Dupont H. Burnout syndrome in critical care team members: A monocentric cross sectional survey. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine. 2017;36(4):223-228. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2016.06.011

4. Ong KK, Ting KC, Chow YL. The trajectory of experience of critical care nurses in providing end‐of‐life care: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of clinical nursing. 2018;27(1-2):257-268. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13882

5. Phillips J, Salamonson Y, Davidson PM. An instrument to assess nurses’ and care assistants’ self-efficacy to provide a palliative approach to older people in residential aged care: A validation study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2011;48(9):1096-1100. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.015

P030

Introduction of a night time safety brief; improving patient safety in Critical Care at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals

Communication

Rachel Ward

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals

Abstract

Introduction: Since the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic in March 2020 we have had to change our day to day working practice in a large Critical Care department, with up to 36 patients across two floors. Prior to the pandemic, each floor functioned as an almost separate unit, with level 2 patients in one area and level 3 patients in another.

Patients requiring level 3 care are now present on both floors although the staffing for each floor has not changed to reflect this. Therefore, out of hours more complex patients are being cared for by staff who have less experience in caring for these patients.

The introduction of safety briefings in clinical care is based on concepts in aviation, where they are designed to make safety-consciousness routine practice.

Objectives: The introduction of a nighttime safety brief aimed to improve safety and communication across Critical Care with the key objectives of introducing all medical and senior nursing staff working across critical care, identifying bed pressures and ill patients. Aims included Increasing visibility of the airway registrar, identifying the skill mix of the staff across the units and initiating contact between medical staff and the nurse in charge across each floor.

Methods: A preliminary survey of medical and nursing staffing was undertaken to explore the attitudes of staff to the current arrangement and the perception of a need for change.

A ‘Night Time Safety Brief’ was developed by creating a proforma of key topics to be discussed and an agenda for a nightly meeting that was designed to take no more than five minutes and targeted to key information sharing.

The location and timing of the briefing was designed to be convenient by liaising with key stakeholders in the meeting. The tool was then implemented with all medical critical care staff and the nurse in charge from each unit meeting to undertake the safety brief following the independent medical handover of each of the units.

A follow up survey was undertaken to assess the impact of the safety brief and staff opinions on the introduction of the brief.

Results: Every member of staff surveyed felt that the introduction of the brief was beneficial. 76% of staff surveyed felt that they were more comfortable working the shift simply by having met the medical and nursing staff from across the floor to better understand the skill mix and points of contact. 90% of staff surveyed felt that the brief would positively impact on patient safety.

Conclusions: Briefings in intensive care are tools that increase the awareness of safety issues among front line staff and foster a culture of safety, making it part of the routine in a clinical area. A simple and effective brief has been developed and used in this tertiary hospital with the aim of improving patient safety.

In this hospital with critical care split across two clinical areas, this has shown to improve communication and team working in a busy tertiary teaching hospital.

P031

Safer discharge of patients from the critical care unit - Improving communications with primary care

Communication

lexandra Cockroft1, Sofia Arkhipkina 2 and Timothy Fudge2

1The Northern Hospital

2Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust

Abstract

Introduction: For patients who survive to hospital discharge following admission to the critical care unit (CCU), the sequelae of critical illness is often prolonged, and can encompass physical and psychological complications. Support is provided to high-risk patients by Salford Royals’ (SRFT) CCU follow-up clinics however, most patient’s ongoing care in the community is provided by general practitioners (GP). Provision of CCU discharge information to primary care is often inadequate or absent, meaning identifying and treating long-term CCU complications can be challenging.

Objectives: We aimed to understand the concerns hospital staff have surrounding CCU discharge communication and the concerns of GPs looking after patients who have had recent CCU admissions. We aimed to improve CCU communication with GPs to enhance safety and quality of ongoing care, in order to increase the support available to patients and their families following critical illness.

Methods: To confirm anecdotal concerns, questionnaires were sent to CCU consultants and junior doctors at SRFT, and GPs in Salford. Questionnaire results were analysed in focus groups and used to create a CCU specific discharge summary. The discharge summary was developed using PDSA methodology.

Results: Consultants (77%) had concerns regarding handover of patient information to ongoing care providers. Juniors (45%) were not confident in providing information regarding CCU long-term complications. Consequently, half of GPs did not find hospital discharge summaries useful in providing information about a CCU admission. No GPs felt confident in signposting patients to CCU follow-up services, with only 14% aware of the SRFT CCU follow-up clinic. Both GPs and CCU consultants agreed a CCU specific discharge summary would be beneficial.

A CCU specific discharge summary was developed and revised with expert opinion from the multidisciplinary team to tackle the issues stated. The discharge summary includes details of diagnoses, organ support, length of stay, ceiling of care, complications addressed by the CCU follow-up team and a CCU discharge information leaflet outlining commonly experienced symptoms and local follow-up services.

Conclusions: This CCU specific discharge summary has enabled SRFT’s CCU to effectively deliver relevant information to GP’s, to ensure continuity of care following discharge. Effective and safe handover of patients between care settings is crucial, to ensure care providers are well informed, and patients managed appropriately. Improving the communication interface between care providers will ensure clinicians are well informed, enabling the safe and timely community management of patients, post-critical care.

P032

Does COVID Affect Clot Formation?

COVID-19

Toby Katz1, Ed Walter 1 , Benjamin Mensah1, Mathew Rogers1, Ashley Tomlison2 and Lucas Alvarez-Belon2

1Royal Surrey NHS Hospital

2Royal Surrey County Hospital

Abstract

Introduction: Covid infection is associated with an increased rate of thrombosis, up to 50%,1 but the reasons for this are unclear.

Rotem is a form of viscoelastic measurement of blood coagulation, allowing graphical representation of the time a clot takes to form (clotting time (CT) and clotting formation time (CFT)), its strength (firmness of the clot after 5 min (A5) and maximum clot firmness (MCF)), and dissolution (maximum lysis (ML). Rotem provides four analyses to each sample: Intem (measure of intrinsic pathway), Extem (extrinsic pathway), Heptem (similar to Intem, excluding heparin effects) and Fibtem (isolating fibrinogen function).

In one study, Covid infection was associated with a reduced clotting time and an increased maximum clot firmness overall.2 The same study also suggested a possible increase in Fibtem MCF value for COVID patients, suggesting a strong influence of fibrinogen on the clot.

This clinical effectiveness audit was designed to determine if (1) Covid patients in the Royal Surrey County Hospital also displayed increased clotting tendencies compared with patients without, as measured by Rotem and fibrinogen levels, and (2) whether fibrinogen levels correlate with Fibtem MCF levels.

Methods: A retrospective data analysis from all Rotem analyses in ICU between June 2020 and February 2021 was performed.

To compare coagulation in patients with and without Covid, data were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilks testing. Normal data were compared by the Student t-test; non-normal data were compared by the Mann-Whitney U-test. A p-value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

In the second part, correlation between fibrinogen values and Fibtem MCF values was assessed using a Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results: 163 patients had Rotem analyses performed, of whom 12 (7.4%) had a positive Covid test.

The median Fibtem A5 in Covid patients was 21 mm compared with 13 mm in non-Covid patients, and median MCF was 25 mm compared with 16 mm, indicating a significant increase in the clot strength by the fibrin component between patients with and without Covid. No other Rotem differences were found.

There was also a statistically significant difference between fibrinogen levels in COVID (median 6.2) and non-COVID (median 3.05) patients, suggesting a significant contribution of fibrinogen to clotting in COVID.

Finally, the study demonstrated a strong positive correlation between fibrinogen levels, as measured by the laboratory, and corresponding Rotem MCF values in all patients (R2 = 0.8105), and in patients with Covid (R2 = 0.905).

Discussion: There was a significant increase in the clot firmness due to the fibrin component, and fibrinogen levels, in patients with Covid infection, compared with those without, consistent with a previous study.2

Rotem measurement of clot strength by fibrin correlated very well with fibrinogen levels.

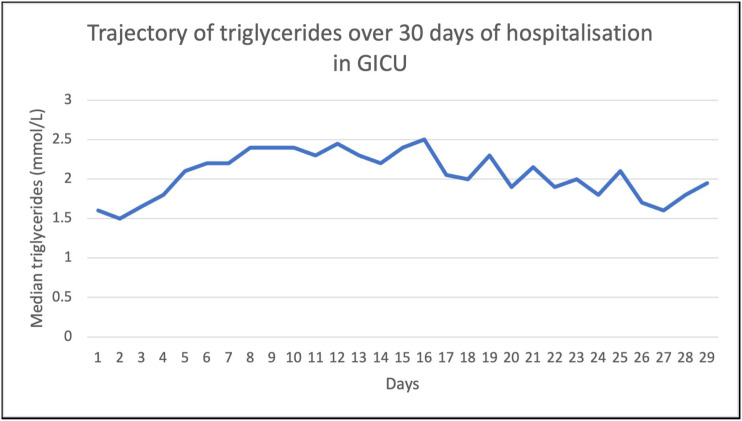

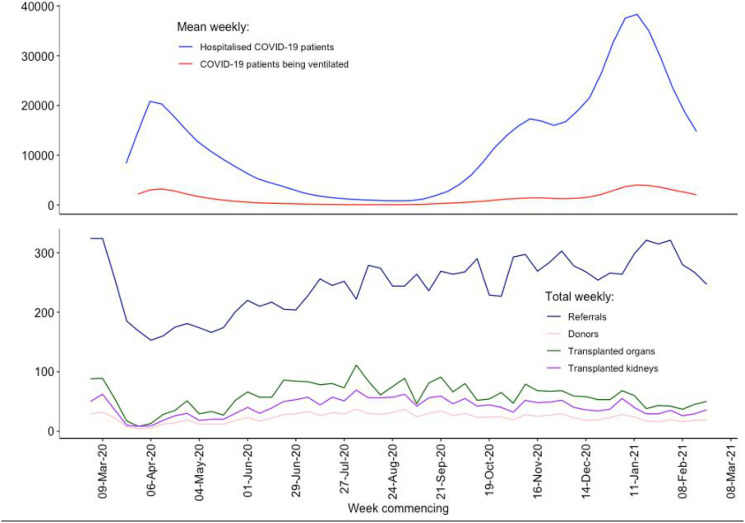

This study suggests that the increase in thrombosis in Covid may be in part related to increased fibrinogen activity.