Abstract

Mothers with elevated Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms demonstrate parenting deficits, as well as difficulties in emotion regulation (ER), which may further impact their ability to effectively parent. However, no empirical research has examined potential mediators that explain the relations between maternal ADHD symptoms and parenting. This prospective longitudinal study examined difficulties with ER as a mediator of the relation between adult ADHD symptoms and parenting among 234 mothers of adolescents recruited from the community when they were between the ages of nine to twelve. Maternal ratings of adult ADHD symptoms, difficulties with ER, and parenting responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions were collected over the course of three years. We found that maternal ADHD symptoms were negatively associated with positive parenting responses to adolescents’ negative emotions, and positively associated with harsh parenting and maternal distress reactions. Moreover, maternal ER mediated the relation between adult ADHD symptoms and harsh parenting responses, while controlling for adolescent ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms. However, maternal ER did not mediate the relation between ADHD symptoms and positive or distressed parental responses. Thus, it appears that ER is one mechanism by which maternal ADHD symptoms are associated with harsh responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotion. These findings may have downstream implications for adolescent adjustment.

Keywords: Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Maternal emotion regulation, Parenting

Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a disorder characterized by excessive levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Approximately 50–80 % of individuals diagnosed with ADHD during childhood retain the diagnosis in adulthood (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, and Fletcher 2006; Faraone, Biederman, and Mick 2006). In addition, prevalence rates of adult ADHD have been documented at around 4.4 % (Kessler et al. 2006). However, recent reports have supported a dimensional view of ADHD, whereby adults with more ADHD symptoms demonstrate greater impairment than those with fewer symptoms, regardless of their diagnostic status (Mannuzza et al. 2011).

Because adults with elevated ADHD symptoms have more difficulty sustaining attention, inhibiting impulsive responses, and organizing activities (McGough and Barkley 2004), many areas of functioning may be negatively impacted. One key role that is impaired among adults with ADHD symptoms is parenting (for a review, see Johnston, Mash, Miller, and Ninowski 2012). Weiss, Hechtman, and Weiss (2000) were among the first to theorize that parents with ADHD may experience more difficulty sustaining attention during supervision of the child and staying calm during their children’s tantrums. Subsequently, multiple empirical studies have demonstrated that mothers with elevated ADHD symptoms are poorer monitors of their children’s behaviors, less effective problem solvers, less involved, less positive/responsive, more negative, and less consistent in their use of discipline than mothers without elevated ADHD symptoms (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2008; Murray and Johnston 2006). More recently, Mokrova et al. (2010) found that mothers with ADHD symptoms also reported the use of non-supportive responses to their children’s negative emotions (e.g., punishing their children, minimizing their children’s feelings, and becoming distressed themselves).

Despite the growing literature demonstrating parenting impairments among adults with ADHD, we know very little about the mechanisms by which this process occurs (Johnston et al. 2012). One possible mechanism that may explain at least some of the parenting deficits demonstrated by adults with ADHD symptoms is the ability to regulate one’s emotions. Emotion regulation (ER) includes both the ability to consciously inhibit one’s self from reacting in a situation, and the ability to consciously modulate one’s emotional state as needed (Eisenberg and Spinrad 2004). Difficulties with ER are ubiquitous to many forms of psychopathology, whereby individuals with psychopathology tend to employ less productive ER strategies (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Schweizer 2010).

Recent research has demonstrated that emotion dysregulation is common among adults with ADHD (Barkley 2010). In fact, Barkley (2010) argued that emotion dysregulation (including difficulties with frustration, impatience, and anger) should be considered a third core component of ADHD (in addition to inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity) because emotion dysregulation is so central to the disorder. In further support of the role of emotion dysregulation in ADHD, Reimherr and colleagues (2005) found that many adults with ADHD presented with symptoms of emotion dysregulation (i.e., temper, affective lability, and emotional overreactivity), independent of comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders. By understanding the unique contribution of ER deficits above the well-established ADHD symptoms, impairments in various life areas, such as parenting, may be better explained (Barkley 2010).

One key aspect of parenting that may be disrupted among adults with ADHD symptoms is the ability to respond effectively to their children’s expressions of negative emotions. In particular, it may be the parent’s own difficulty regulating emotions that makes it more challenging for him/her to respond supportively when his/her child expresses negative emotions. Because parents are their children’s first models for emotion socialization, a parent’s ability to effectively cope with his/her own emotions and respond to his/her child’s expression of emotions is important for the development of the child’s emotional and social competence (Eisenberg, Cumberland, and Spinrad 1998). For example, Ramsden and Hubbard (2002) demonstrated that mothers who were not accepting of their children’s negative emotions were more likely to have children who had difficulty regulating their own emotions and displayed higher levels of aggression. Conversely, in a longitudinal study, Gottman, Katz, and Hooven (1996) found that parents who were more aware of and accepting of their children’s emotions had children with fewer behavior problems, greater academic achievement, and better physical health. Thus, examination of the manner in which parents respond to their children’s expressions of negative emotions is an important aspect of parenting that merits continued empirical examination.

Given that adults with ADHD symptoms often have difficulty with ER, these ER deficits may in part explain the documented association between adult ADHD symptoms and parenting. For example, parents with attention and ER difficulties could resort to using harsh or unsupportive parenting strategies in response to challenging child emotions (Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, and Martin 2001). Yet, to our knowledge, no empirical research has examined maternal emotion dysregulation as a mechanism by which adult ADHD symptoms relate to harsh or unsupportive parenting responses. Given that adolescence is a developmental period during which elevated conflict between the parent and adolescent is typical as the adolescent seeks greater autonomy (Steinberg 2001), examining parenting responses during the adolescent years is particularly important to further our understanding of the manner and mechanisms by which mothers with ADHD symptoms are impaired in the parenting role.

The present study therefore aimed to examine, in a community sample of 234 families, the predictive relations among maternal ADHD symptoms, maternal ER, and parenting. We specifically examined the manner in which mothers respond to their adolescents’ displays of negative emotions because adolescent’s negative emotions are more difficult for parents to tolerate than positive emotions (Fabes et al. 2001), and because negative affect increases during this developmental stage (Ciarrochi, Heaven, and Supavadeeprasit 2008). We hypothesized that higher levels of maternal ADHD symptoms would predict: lower levels of positive parenting responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions, higher levels of harsh parenting responses to adolescents’ negative emotions, and higher levels of distress responses to adolescents’ negative emotions. We also hypothesized that the links between maternal ADHD and parenting would be mediated by mothers’ difficulties regulating their own emotions. Given that adolescents with ADHD and other disruptive behaviors tend to evoke more over-reactive and inconsistent responses from their parents and have more negative interactions with them (Burke, Pardini, and Loeber 2008; Johnston and Mash 2001), we considered the contribution of adolescent ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms to parenting responses in our models. We hypothesized that maternal ER would continue to mediate the relation between maternal ADHD symptoms and parenting when difficult adolescent behavior was included in the model.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants included 234 mothers of youth who were originally recruited between the ages of 9–12 years as part of a larger longitudinal study examining early predictors of adolescent risk-taking behavior in a community sample. The youth were, on average, 12 years old at wave 2, 13 years old at wave 3, and 14 years old at wave 4 (see Table 1); and are therefore referred to as adolescents throughout this paper. The adolescents were 52 % male and 43 % of the sample were Caucasian, 41 % were African American, and 16 % identified as Other. The original sample of 277 adolescents and their parents were recruited through media outreach and mailings to schools, libraries and youth organizations within the Washington, DC metropolitan area. Inclusion criteria for the original study included the adolescents being within the specified age range, English language proficiency, consent of the parent/guardian, and youth assent. Sample demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Wave 1 participant demographics

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Mother | |

| Mean Age at T1 (SD) | 41.86 (6.21) |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 2.2 |

| High school degree/GED | 10.1 |

| Technical or trade school | 3.4 |

| Some college | 20.8 |

| Associates degree | 5.6 |

| College degree | 27.0 |

| Graduate school degree | 27.5 |

| Median Annual Income | $85,000 |

| Child | |

| Ethnicity/Race (%) | |

| Caucasian | 43.0 |

| African American | 40.8 |

| Other | 16.2 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Male | 52.2 |

| Female | 47.8 |

| Mean Age (SD) at T2 | 12.07 (0.9) |

| Mean Age (SD) at T3 | 13.06 (0.9) |

| Mean Age (SD) at T4 | 14.00 (0.9) |

With approval from the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board, families were invited into the laboratory for baseline assessments if they met inclusion criteria based on a telephone screen. Thereafter, families were assessed at annual intervals. Of the original 277 participants in Time 1, 234 mothers participated in Time 2, 234 in Time 3, and 221 in Time 4. Because constructs central to the current analyses were not included in all waves, the present study included data from T2 through T4 only. To assess for the impact of missing data, we compared participation for all participants who completed measures at each wave of the study to those who did not complete measures at that particular wave on gender, ethnicity/race, adult ADHD symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and parenting responses. Attrition was not significantly correlated with any of these key study variables (all ps>0.10).

Measures

Demographics.

At each assessment point, parents/guardians completed a basic demographics form, which included personal information such as age, gender, ethnicity/race, and annual family income.

Mothers’ ADHD Symptoms.

Mothers completed the Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS-S: SV; Conners et al., 1999) at T2. The CAARS assesses the core features of ADHD and symptoms appropriate for adults. Mothers were instructed to rate a list of 30 behaviors on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all, never) to 3 (very much, very frequently) based on how often or how much the item described their experiences with ADHD symptoms. Higher raw scores on the CAARS indicated that a mother experienced more ADHD symptoms. For the purposes of the current study, we calculated a total score using the CAARS DSM-IV Total ADHD symptom scale for inclusion in the models. In addition, means, standard deviations, and correlations with other study measures are provided for the DSM-IV Inattentive (IA) and Hyperactive-Impulsive (HY/IM) scales in Table 2. The CAARS has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties and validated age- and gender-based norms, including excellent test-retest reliability and moderate convergent validity with the Wender Utah Rating Scale (Erhardt, Epstein, Conners, Parker, and Sitarenios 1999) and adequate discriminant validity with the Beck Depression Inventory II (Steer et al. 2003). Internal consistency for the CAARS DSM-IV Total raw score in this sample was α= .89 (M=12.11, SD=7.66).

Table 2.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T2 CAARS Total Score | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. T2 CAARS IA Symptoms | 0.91*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. T2 CAARS HY/IM Symptoms | 0.88*** | 0.61*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. T3 DERS | 0.45*** | 0.47*** | 0.32*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. T3 Positive Responses | −0.32*** | −0.31*** | −0.26** | −0.32*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. T3 Harsh Responses | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27*** | −0.09 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. T3 Distress Responses | 0.36*** | 0.32*** | 0.33*** | 0.41*** | −0.32*** | 0.46*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. T4 Positive Responses | −0.25** | −0.30** | −0.13* | −0.18* | 0.70*** | −0.05 | −0.25** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. T4 Harsh Responses | 0.19** | 0.18* | 0.15* | 0.39*** | −0.19** | 0.77*** | 0.41*** | −0.14* | 1.00 | |||

| 10. T4 Distress Responses | 0.33*** | 0.32*** | 0.25** | 0.48*** | −0.35*** | 0.34*** | 0.72*** | −0.35*** | 0.53*** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. T2 CES-D | 0.42*** | 0.44*** | 0.30*** | 0.46*** | −0.21** | 0.15* | 0.25** | −0.12 | 0.30*** | 0.31*** | 1.00 | |

| 12.T2 DBD | 0.36*** | 0.35*** | 0.29*** | 0.10 | −0.23** | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.26** | 0.14* | 0.08 | 0.15* | 1.00 |

| Mean | 12.00 | 6.12 | 5.88 | 64.49 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 9,82 | 3.76 |

| SD | 7.66 | 4.50 | 4.07 | 16.40 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 8.39 | 5.77 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

CAARS=Connor’s Adult ADHD Rating Scale, IA=Inattentive, HY/IM=Hyperactive-Impulsive, DERS=Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, CES-D=Centers for pidemiological Studies – Depression, DBD=Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale

Mothers’ Difficulty With Emotion Regulation.

Mothers’ ER deficits were assessed using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer 2004) at T3 and T4. The DERS is a 36-item measure where mothers rated how often each item applied to them based on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (almost never, 0–10%) to 5 (almost always, 91–100%). These items assessed six domains of ER deficits: Nonacceptance of negative emotions, inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors when distressed, difficulty controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, being unclear about what emotion is being experienced, and lack of emotional awareness. A total score was calculated by summing all items. Items were coded so that a higher total score on the DERS indicated greater difficulties with emotion regulation. The DERS total score has high internal consistency (0.93) and test-retest reliability (0.88) and adequate construct and predictive validity (Gratz and Roemer 2004). Additionally, the DERS has shown adequate convergent and discriminant validity with measures of anxiety and depression (Gratz and Roemer 2004; Staples and Mohlman 2012). Internal consistency for the DERS total score in this sample was α= .80.

Mothers’ Depression Symptoms.

Given high levels of comorbidity between ADHD and depression in adult females (Kessler et al. 2006), as well as established links between depression and ER (Aldao et al. 2010; Gross and Muñoz 1995), and depression and parenting (Lovejoy et al. 2000), we included a measure of maternal depression in our analyses to isolate the contribution of maternal ADHD to ER and parenting. Mothers’ depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) at T2. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms across four domains: depressed affect, positive affect, somatic activity, and interpersonal relations. Items are ranked on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Items are summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 60. The CES-D is widely used in adult community samples and demonstrates adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability (Knight et al. 1997) and convergent validity and discriminant validity with self-esteem and state and trait anxiety (Radloff 1977). Internal consistency for the CES-D in the current sample was α= .88.

Mothers’ Responses to Their children’s Expression of Emotions

Mothers completed the Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale-Adolescent Version (CCNES-AP; Fabes and Eisenberg 1998) at T3 and T4. The CCNES consisted of nine items presenting different situations in which an adolescent expresses a negative emotion (e.g., “When my teenager gets angry because he/she can’t get something that he/she really wants, I usually…”). Mothers assessed how likely they would be to respond to their adolescents’ expression of negative emotions with each of the following six responses based on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely): problem-focused responses (e.g., “help him/her think of other ways to go about getting what he/she wants”), emotion-focused responses (e.g., “try to make him/her feel better by making him/her laugh”), expressive encouragement (e.g., “encourage him/her to talk about his/her angry feelings”), punitive responses (e.g., “get upset with him/her for being so angry”), distress responses (e.g., “become uncomfortable and don’t want to deal with him/her”) and minimization responses (e.g., “tell him/her he/she is being silly for getting so angry”). Total scores were calculated for each type of response, with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood that a mother would employ that response.

In this study, mothers’ responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions were categorized into three distinct parental responses (Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, and Madden-Derdich 2002): positive responses, harsh responses, and distress responses. Positive parenting responses were defined by mothers’ use of supportive responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions and included the problem-focused, emotion-focused, and expressive encouragement subscales described above. Harsh parental responses were defined by mothers’ use of non-supportive coping responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions and included the punitive and minimizing scales. Finally, distress responses were treated as a separate dimension of parental responses that described mothers’ own emotional response to their adolescents’ expression of negative emotions.

In line with previous research (Ehrlich et al. 2013a; Fabes et al. 2001), we computed a composite Harsh Parental Responses to Adolescent Expressions of Negative Emotions summary score by averaging the z-scores of the minimizing responses and punitive responses subscales. We also created a composite Positive Parental Responses to Adolescent Expressions of Negative Emotions summary score, averaging the z-scores of problem-focused responses, expressive encouragement, and emotion-focused responses subscales. Previous research has shown reliability estimates at 0.73 for the harsh parental response subscale and 0.87 for the positive parental response subscale with the adolescent version of this measure (Ehrlich et al. 2013a; Ehrlich et al. 2013b). The CCNES has also demonstrated adequate test-retest reliability and convergent and divergent validity with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index and the Parent Affect Test (Fabes et al. 2002). All summary scores at T3 and T4 were reliable (αs ranged from 0.84–0.90).

Child Disruptive Behavior Symptoms

Given that adolescent disruptive behaviors, including ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD), are closely linked with negative parenting (Burke et al. 2008; Johnston and Mash 2001), we included the mother-reported Disruptive Behavior Disorders checklist (DBD; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, and Milich 1992) at T2 to determine the relative contribution of parent and adolescent factors on parenting responses. Ratings were based on a 4-point scale from occurring not at all to very much (Pelham et al. 1992), where symptoms rated pretty much or very much true of the adolescent were considered present to a clinically significant degree. All items occurring at a clinically significant level were summed to create a total adolescent ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders score. The DBD has been used with adolescents up to age 18 (Pelham et al. 1992) and demonstrates good internal consistency, adequate test-retest reliability, and is sensitive to treatment effects (Pelham, Fabiano, and Massetti 2005). Internal consistency for T2 total DBD score in the current sample was α=0.93.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Missing data patterns were examined among all key study variables. In order to evaluate patterns of missingness, we computed Little’s (1988) missing completely at random (MCAR) test; results suggest the data are missing completely at random, χ2 (95)=90.04, p=0.63.

Descriptive statistics for T2 ADHD, CES-D, and DBD scores; T3 DERS; and T3 and T4 positive, harsh, and distress parental responses are reported in Table 2. Clinical levels of maternal ADHD symptoms were examined for comparison with other samples. CAARS raw scores ranged from 0 to 46; t-scores were also computed for ADHD symptoms (Mt=45.2, range=25–90) to provide an index of maternal ADHD symptom severity. Using the established clinical cutoff of 1.5 standard deviations above the mean (Conners et al. 1999), 7 % of our sample of mothers was in the clinical range for adult ADHD, which is consistent with prevalence estimates reported by Barkley et al. (2008). We also examined clinical levels of adolescents’ ADHD, CD, and ODD symptoms. We found 3.4 %, 3 %, and 4.8 % of our sample (respectively) were in the clinical range (i.e., above symptom cutoffs) for these disorders, similar to rates reported from other community samples (e.g. Costello et al. 2005).

Bivariate correlations were also computed for all variables (Table 2). T3 DERS was associated with all parenting variables at both time points, suggesting that poor maternal ER was positively associated with distress parenting responses and harsh parenting responses and negatively associated with positive parenting responses. In support of our original hypotheses, T2 maternal ADHD symptoms were positively correlated with both T3 and T4 parental distress responses as well as T2 DBD scores. Further, T2 maternal ADHD symptoms were negatively associated with positive parental responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions at both T3 and T4. T2 maternal ADHD symptoms were significantly and positively associated with harsh parental responses at T4 only. Both the IA and HY/IM subscales also followed the same pattern of associations as the total ADHD scale.

We also examined the relation between maternal ethnicity/race (using the groups European American, African American, and other) and all dependent variables using one-way ANOVAs because specific ethnicity/race has been associated with variations in parenting within the literature (e.g. Fagan 2000). There was a significant association between ethnicity/race on T3 DERS only, F (2, 171)=4.00, p=0.02 (all other ps ranged from 0.10–0.43). Post-hoc Tukey comparisons between groups indicate that European Americans reported significantly greater levels of difficulty in ER (M=66.96, 95 % CI [63.56, 70.36]) than African Americans (M=59.80, 95 % CI [56.28, 63.32]), p=0.02. Comparisons between the “other” group (M=66.00, 95 % CI [56.30, 75.69]) and the African American and European American groups were not statistically significant at p<0.05.

Predicting Mothers’ Responses to their Adolescents’ Expressions of Negative Emotions

We had also predicted that T3 ER difficulties would mediate the relation between T2 adult ADHD symptoms and T4 maternal responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. These analyses were conducted using Mplus 6 (Muthen and Muthen 1998–2010). We utilized a full information maximum likelihood estimation method to handle missing data, which provides less biased parameter estimates than ad hoc procedures (such as listwise and pairwise deletion) and is more robust to non-normal data (Little and Rubin 1989). In order to examine the hypothesized relations between maternal ADHD symptoms, ER, and parenting responses, we tested a series of structural equation models (SEM). Four fit indices were used to estimate how well the model fit the data: the χ2 statistic, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler 1990), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker and Lewis 1973), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger 1990). Nonsignificant chi-square values indicate good fit; however, this index is sensitive to sample size (Kline 2005). TLI values greater than 0.90 (Hu and Bentler 1999), CFI values greater than 0.93 (Byrne 1994) and RMSEA values less than 0.05 (Steiger 1990) suggest good fit.

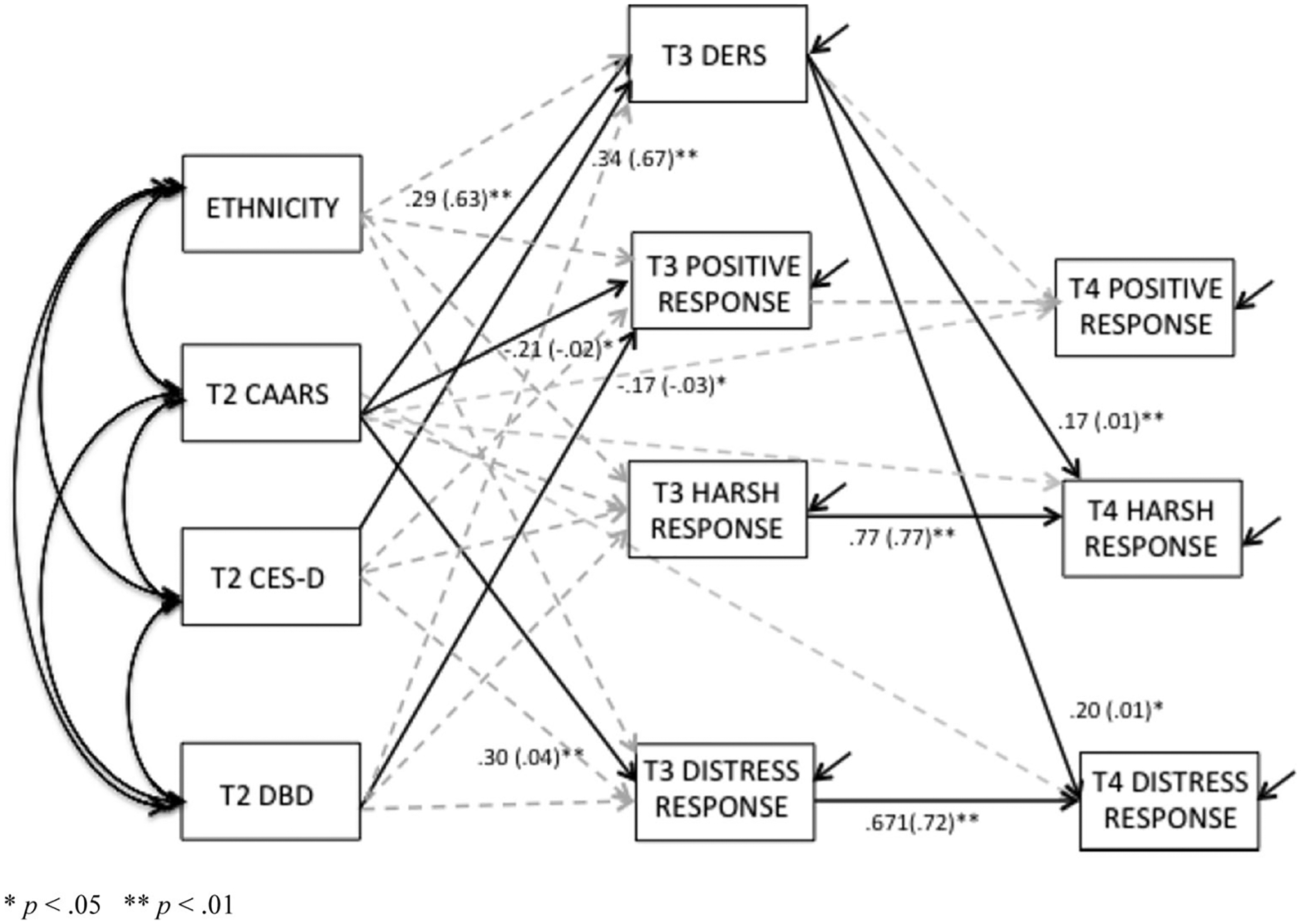

We examined the hypothesis that maternal ER would mediate the relation between maternal ADHD symptoms and parenting responses by testing a path model (see Fig. 1) in which T2 CAARS predicted T3 DERS and T4 parental responses, controlling for prior levels of parental responses, maternal depression, adolescents’ ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders, and (dummy coded) ethnicity/race1. Cross-wave correlations were allowed between the disturbance terms of positive parenting variables, in line with recommendations by Marsh (1993). The model fit the data well: χ2 (15)=17.61, p=0.28; CFI=0.99; TLI=0.99; and RMSEA=0.03 [90 % CI=0.00–0.07]. Path estimates suggest that T2 CAARS was significantly associated with T3 DERS and T3 DERS predicted T4 harsh and distress responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions, controlling for ethnicity, maternal depression, and children’s ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Standardized (and unstandardized) significant path estimates for mediation model. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01. Solid lines represent significant paths. Correlated residuals are not shown. CAARS=Connor’s Adult ADHD Rating Scale, DERS= Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression, DBD=Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale

We tested the indirect effects from the full model (i.e., T2 CAARS to T3 DERS to T4 parental responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions) by estimating their confidence intervals, using the bootstrapping procedure recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Unlike hypothesis testing based on parametric statistics, bootstrapping procedures do not assume normality (Preacher and Hayes 2008). An indirect effect with a confidence interval that does not contain zero would indicate a statistically significant indirect effect of maternal ADHD symptoms on parenting through ER. Results from the current analyses suggest the indirect effect of T2 CAARS on T4 harsh parenting responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions was significant, controlling for ethnicity, maternal depression, and children’s ADHD and disruptive behaviors, indirect effect=0.05, SE=0.03; [95 % CI=0.001–0.100], providing support for Hypothesis 4; however, the indirect effects of T2 CAARS on T4 positive parenting responses indirect effect=0.05, SE=0.05; [95 % CI=−0.051–0.155] and distress responses indirect effect=0.06, SE=0.03; [95 % CI=−0.003–0.119] were not significant.

Discussion

The purpose of this prospective longitudinal study was to better understand the mechanisms by which maternal ADHD symptoms impact mothers’ abilities to respond effectively to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. In doing so, this study advances our understanding of mechanisms that explain the link between maternal ADHD symptoms and maladaptive parenting (Johnston et al. 2012). This study additionally advances knowledge regarding how symptoms of maternal psychopathology relate to the manner in which mothers respond to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions (Katz et al. 2012).

The current study yielded several important findings, including establishing that maternal ADHD symptoms were negatively associated with positive maternal parenting responses to adolescents’ negative emotions, and positively associated with harsh parenting and maternal distress responses. In addition, maternal difficulties with ER were positively associated with distress responses and harsh parenting responses, and negatively associated with positive parenting responses after controlling for ethnicity, maternal depression, and children’s ADHD and disruptive behaviors. Importantly, maternal difficulties with ER mediated the relation between maternal ADHD symptoms and maternal harsh parenting responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. The indirect effects of ADHD on harsh parenting responses remained significant when we included maternal depression in the model. Additionally, mothers’ ADHD symptoms continued to significantly predict maternal ER and ER, in turn, predicted harsh parenting responses, above and beyond the effect of adolescents’ ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms (i.e., controlling for “child effects”).

In this community sample, maternal ADHD symptoms were significantly related to all three types of parenting responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotion (positive, harsh, and distress responses) in the expected directions. Given that parents with ADHD symptoms generally have more difficulty problem-solving (Murray and Johnston 2006), inhibiting impulsive responses (McGough and Barkley 2004), and staying calm in difficult parenting situations (Weiss et al. 2000), it is not surprising that mothers with elevated ADHD symptoms were less likely to endorse positive parenting response items, such as “help my adolescent think of things to do to solve the problem” and “talk to my adolescent to calm him/her down.” Studies have also shown that children with ADHD have difficulty attending appropriately to others’ non-verbal cues (Cadesky et al. 2000), which may continue into adulthood. Johnston and colleagues (2012), in their recent review, pointed to this difficulty of reading others’ social cues as another potential problem for parents with ADHD in terms of responding supportively to their children. Mothers with ADHD symptoms may therefore be unable to stay calm, interpret the situation appropriately, and plan a supportive response in the midst of their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions.

In fact, mothers who reported more ADHD symptoms also reported using harsh and distress parenting response items such as “I get upset with him/her for being so angry” or “I become uncomfortable and don’t want to deal with him/her.” Consistent with other studies conducted with children (Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2011), this finding suggests that mothers with ADHD symptoms may have more difficulties inhibiting their impulsive emotional or physical responses when they are confronted with a difficult parenting situation. Rather than optimally responding to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions by using effective coping strategies, like problem-solving, accepting their emotions, or encouraging them to express themselves, these parents may instead respond harshly (Fabes et al. 2002).

It is important to note that, while mothers’ ADHD symptoms were significantly correlated with mothers’ reports of harsh parenting responses at T4, they were not significantly correlated with harsh parenting responses at T3. This fluctuation in results may reflect a weak relationship between maternal reports of ADHD symptoms and harsh parenting responses, perhaps because community samples frequently report low rates of harsh parenting (Fabes et al. 2002; Rhoades and O’Leary 2007).

Unfortunately, we were unable to examine the relative contributions of maternal IA and HY/IM symptoms separately due to poor model fit. However, some studies that have attempted to look at the relationship between parenting behaviors and symptoms of IA and HY/IM separately have found that self-reports of over-reactive parenting were positively associated with mothers’ reports of their own HY/IM symptoms, but not IA symptoms (Johnston et al. 2004). Future studies should attempt to examine the unique contributions of adult HY/IM symptoms versus IA symptoms on parenting in order to better understand which factors are most closely associated with different facets of parenting (Johnston et al. 2012).

As expected, maternal ADHD symptoms were associated with greater difficulties with ER, and greater maternal difficulties with ER were associated with positive, harsh, and distress responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. This is consistent with past literature demonstrating that adults with ADHD experience more difficulty regulating their emotions (Barkley 2010). This finding is also consistent with Fabes and colleagues’ (2002) research demonstrating that parents who have difficulty regulating their own emotions also may become distressed themselves when their adolescents express negative emotions and, as a result, respond more harshly to them.

Importantly, we found that maternal difficulties with ER mediated the relation between ADHD symptoms and harsh parental responses to adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. The positive relation between ADHD symptoms and harsh parental responses has been demonstrated in prior studies showing that mothers with more ADHD symptoms tend to display less positive and more negative parenting (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2008; Johnston et al. 2012). Additionally, this study did not find emotion dysregulation to be a significant mediator of the relation between maternal ADHD symptoms and either parental positive or distress responses. This indicates that there may be another mechanism by which maternal ADHD symptoms influence these types of parenting responses (perhaps problem solving skills or the ability to read social cues).

The relation between maternal ADHD symptoms and harsh parental responses remained significant when we included adolescent disruptive behaviors into the model to control for “child effects.” By including adolescent ADHD and disruptive behavior in our model, we were able to determine the relative effects of parent versus child factors on parents’ abilities to respond effectively to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. Given that adolescents with ADHD and disruptive behaviors tend to evoke over-reactive and inconsistent responses from their parents (Burke et al. 2008; Johnston and Mash 2001), it was important to examine the extent to which maternal ADHD symptoms and ER contributed to maladaptive parenting beyond child effects. Future studies with larger samples should extend these findings by examining adolescent ADHD as a potential moderator of the relationship between maternal ER and parenting among mothers with ADHD symptoms.

Including maternal depressive symptoms in the model allowed us to document the unique associations among maternal ADHD symptoms, ER, and parenting. Depressive symptoms were important to consider in the model because research has shown that depressed mothers, similar to mothers with ADHD, tend to engage in more negative parenting behaviors, including more hostile and coercive behaviors towards to their children (Goodman 2007). In addition, ADHD and depression have been shown to be highly comorbid disorders, particularly in adult females (Kessler et al. 2006). Many prior studies examining maternal ADHD symptoms and parenting have not considered maternal depressive symptoms (Johnston et al. 2012). In doing so, we have greater confidence in our conclusions. However, we were unable to examine other possible co-occurring maternal symptoms, such as antisocial personality or anxiety symptoms, in our analyses. Therefore, future studies should examine a range of potential maternal difficulties that could impact the associations among maternal ADHD symptoms, ER, and parenting responses.

Although this study had many strengths, including a large diverse sample and a prospective longitudinal design, these findings must be considered in the context of some limitations. First, all measures included in these analyses were based on maternal report and did not include any observational measures of parent-child dyadic interactions, raising the possibility that shared method variance influenced results. Future studies should therefore include an observed parent-child interaction in which parent behaviors are coded with a standardized coding system, which is the gold standard in parenting studies (Danforth et al. 1991; Johnston et al. 2002). There may also have been a social desirability component at play that may result in these mothers not accurately reporting their use of harsh parenting responses (Lui et al. 2013); however, some studies have shown moderate to strong correlations between self- and other-reports of ADHD symptoms (e.g. Belendiuk et al. 2007). In addition, study assessments were conducted at different time points, which should have reduced the possibility of within-informant biases that may have occurred due to fluctuations in mood or other variables. Still, future studies should include other informant reports (e.g., from a partner or the child) or observational parenting data to enhance the measurement of maternal ADHD symptoms and parenting responses (McGough and Barkley 2004). Future studies might also incorporate biological measures of maternal ER (e.g., Ochsner et al. 2002). By including a measure of neural correlates, we may be able to identify activity patterns in specific areas of the maternal brain, which impact mothers’ ER and/or parenting (Swain 2011).

Additionally, we did not have measurements of all of the variables at all time points. This impeded our ability to examine maternal ADHD symptoms as a predictor of changes on the DERS. Also, the timing of our assessments, developmentally, could have been problematic. Given that maternal ADHD symptoms and ER abilities were likely present long before adulthood, we may have missed some critical periods of development. Also, given the timing of the parenting measure (i.e., at T4), we could not yet examine downstream effects of harsh maternal responses on subsequent adolescent socio-emotional development. Finally, although adolescence is an important developmental period to examine the mechanisms by which maternal ADHD symptoms impact parenting responses, it will be important for future studies to examine these questions at earlier stages of development as well.

Another limitation is that this study included only mothers. Future studies should include fathers as well, in order to determine if there are important differences in the manner in which maternal and paternal ADHD symptoms are associated with parental responses to adolescent expressions of negative emotions. Indeed, some research suggests that mothers and fathers employ different parenting strategies on the whole, especially in relation to disciplinary strategies and emotional support (Holmbeck et al. 1995; Russell et al. 2003; Tein et al. 1994).

Fourth, this was a community sample, and therefore, we were unable to examine the impact of more severe adult ADHD-related difficulties and how they might affect mothers’ parenting responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. Because we did not include a diagnostic interview or a measure of adult impairment in this study, we do not know the extent to which maternal ADHD symptoms were associated with impairment in functioning. It is likely that mothers experiencing greater impairment due to their ADHD symptoms may employ harsher responses to their adolescents’ negative emotions. Consistent with past literature that showed that community samples do not frequently report the use of harsh parenting (Fabes et al. 2002; Rhoades and O’Leary 2007), this sample reported relatively low rates of harsh parenting. On the other hand, this sample was consistent with other community samples in terms of ADHD symptoms as reported on the CAARS (Barkley et al. 2008; Erhardt et al. 1999). Future studies should include adult impairment measures (e.g., Barkley Functional Impairment Scale–Self Report; Barkley 2011), or ideally diagnostic interviews, to explore the extent to which functional impairments related to parental ADHD symptoms impact parenting. Future studies might also examine these questions in a clinical sample of parents with ADHD.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes uniquely to the literature by representing the first investigation of ER difficulties as one mechanism by which maternal ADHD symptoms are associated with harsh parenting responses to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions. This also represents one of the first studies to examine associations between maternal symptoms of psychopathology and the manner in which mothers’ respond to their adolescents’ expressions of negative emotions (Katz et al. 2012). This study found that the positive association between maternal ADHD symptoms and harsh parenting responses was at least partially mediated by maternal ER. Future studies should examine the impact of these parenting responses on adolescent socio-emotional development. Furthermore, this knowledge should inform the development of interventions that target maternal difficulties with ER, in addition to parenting, because of its potential impact on adolescent development (Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2014; Maliken and Katz 2013).

Acknowledgments

This project funded by a grant from NIH 2R01 DA18647 awarded to C.W. Lejuez, by NIDA R21-DA25550 to Jude Cassidy, and by NIDA F31- DA27365 to Katherine B. Ehrlich.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

We also ran the model with inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive ADHD symptoms as separate predictors. Traditional fit-criteria for structural equation models indicate that the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) should be greater than 0.90 (Hu and Bentler 1999), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) should above 0.93 (Byrne 1994) and the RMSEA should be below 0.05 (Steiger 1990). Unfortunately the model utilizing separate maternal inattentive and hyperactive/ impulsive symptoms did not meet these conventional cut-offs for adequate model fit (χ2 (19)=46.50, p<0.001, CFI=0.96, TLI=0.88, and RMSEA=0.08 [90 % CI=0.05–0.10]) and was therefore uninterpretable.

Contributor Information

Heather Mazursky-Horowitz, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA.

Julia W. Felton, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Laura MacPherson, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA.

Katherine B. Ehrlich, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA.

Jude Cassidy, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA.

C. W. Lejuez, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Andrea Chronis-Tuscano, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, 2109B Biology/Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Compendium 2000. (2000). Arlington, VA US: American Psychiatric Association [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2010). Deficient emotional self-regulation: a core component of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders, 1, 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2011). Barkley functional impairment scale (BFIS). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, & Fletcher K (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, & Fischer M (2008). ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Belendiuk KA, Clarke TL, Chronis AM, & Raggi VL (2007). Assessing the concordance of measures used to diagnose adult ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 10, 276–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Pardini DA, & Loeber R (2008). Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 679–692. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cadesky E, Mota V, & Schachar RJ (2000). Beyond words: How do problem children with ADHD and/or conduct problems process nonverbal information about affect? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1160–1167. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Raggi VL, Clarke TL, Rooney ME, Diaz Y, & Pian J (2008). Associations between maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 1237–1250. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, O’Brien KA, Johnston C, Jones HA, Clarke TL, Raggi VL, et al. (2011). The relation between maternal ADHD symptoms & improvement in child behavior following brief behavioral parent training is mediated by change in negative parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1047–1057. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9518-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Lewis-Morrarty E, Woods KE, O’Brien KA, Mazursky-Horowitz H, & Thomas SR (2014). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy-Emotion Development for preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Ciarrochi J, Heaven PL, & Supavadeeprasit S (2008). The link between emotion identification skills and socio-emotional functioning in early adolescence: a 1-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 565–582. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Erhardt DD, Epstein JN, Parker JA, Sitarenios GG, & Sparrow EE (1999a). Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults: I. Factor structure and normative data. Journal of Attention Disorders, 3, 141–151. doi: 10.1177/108705479900300303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Erhardt D, & Sparrow EP (1999b). Conners’ adult ADHD rating scales: Technical manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger H, & Angold A (2005). 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 972–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth JS, Barkley RA, & Stokes TF (1991). Observations of parent-child interactions with hyperactive children: research and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 703–727. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(91)90127-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KB, Cassidy J, Gorka S, Lejuez CW, & Daughters SB (2013a). Adolescent friendships in the context of dual risk: the roles of low adolescent distress tolerance and harsh parental response to adolescent distress. Emotion, 13, 843–851. doi: 10.1037/a0032587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KB, Cassidy J, Lejuez CW, & Daughters SB (2013b). Discrepancies about adolescent relationships as a function of informant attachment and depressive symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi: 10.1111/jora.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, & Spinrad TL (2004). Emotion-related regulation: sharpening the definition. Child Development, 75, 334–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, & Spinrad TL (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt DD, Epstein JN, Conners CK, Parker JA, & Sitarenios GG (1999). Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults: II. Reliability, validity, and diagnostic sensitivity. Journal of Attention Disorders, 3, 153–158. doi: 10.1177/108705479900300304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, & Eisenberg N (1998). The coping with Children’s negative emotions scale_adolescent perception version: Procedures and scoring. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Leonard SA, Kupanoff K, & Martin C (2001). Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Development, 72, 907–920. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, & Madden-Derdich DA (2002). The coping with Children’s negative emotions scale (CCNES): psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review, 34, 285–310. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J (2000). African american and Puerto Rican american parenting styles, paternal involvement, and head start children’s social competence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology, 46, 592–612. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, & Mick E (2006). The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine, 36, 159–165. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500471X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH (2007). Depression in mothers. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz L, & Hooven C (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 243–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Muñoz RF (1995). Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 2, 151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1995.tb00036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Paikoff RL, & Brooks-Gunn J (1995). Parenting adolescents. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Children and parenting, Vol. 1, pp. 91–118). Hillsdale, NJ England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LÄ, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, & Mash EJ (2001). Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4, 183–207. doi: 10.1023/A:1017592030434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Murray C, Hinshaw SP, Pelham WR, & Hoza B (2002). Responsiveness in interactions of mothers and sons with ADHD: relations to maternal and child characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 77–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1014235200174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Scoular DJ, & Ohan JL (2004). Mothers’ reports of parenting in families of children with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: relations to impression management. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 26, 45–61. doi: 10.1300/J019v26n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Mash EJ, Miller N, & Ninowski JE (2012). Parenting in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Maliken AC, & Stettler NM (2012). Parental meta-emotion philosophy: a review of research and theoretical framework. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00244.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners C, Demler O, et al. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the united states: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, & Olaman S (1997). Psychometric properties of the centre for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, & Rubin DB (1989). The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods & Research, 18, 292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy M, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, & Neuman G (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui JL, Johnston C, Lee CM, & Lee-Flynn SC (2013). Parental ADHD symptoms and self-reports of positive parenting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0033490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliken AC, & Katz L (2013). Exploring the impact of parental psychopathology and emotion regulation on evidence-based parenting interventions: a transdiagnostic approach to improving treatment effectiveness. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Castellanos FX, Roizen ER, Hutchison JA, Lashua EC, & Klein RG (2011). Impact of the impairment criterion in the diagnosis of adult ADHD: 33-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 122–129. doi: 10.1177/1087054709359907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW (1993). Stability of individual differences in multiwave panel studies: comparison of simplex models and one-factor models. Journal of Educational Measurement, 30, 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- McGough JJ, & Barkley RA (2004). Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1948–1956. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokrova I, O’Brien M, Calkins S, & Keane S (2010). Parental ADHD symptomology and ineffective parenting: the connecting link of home chaos. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10, 119–135. doi: 10.1080/15295190903212844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, & Johnston C (2006). Parenting in mothers with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 52–61. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (1998–2010). Mplus User’s Guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, & Gabrieli JE (2002). Rethinking feelings: an fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 1215–1229. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, & Milich R (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child, 31, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WR, Fabiano GA, & Massetti GM (2005). Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 449–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden SR, & Hubbard JA (2002). Family expressiveness and parental emotion coaching: their role in children’s emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 657–667. doi: 10.1023/A:1020819915881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimherr FW, Marchant BK, Strong RE, Hedges DW, Adler L, Spencer TJ, et al. (2005). Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD and response to atomoxetine. Biological Psychiatry, 58, 125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA, & O’Leary SG (2007). Factor structure and validity of the parenting scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 137–146. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Hart CH, Robinson CC, & Olsen SF (2003). Children’s sociable and aggressive behavior with peers: a comparison of the US and Australian, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 74–86. doi: 10.1080/01650250244000038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staples AM, & Mohlman J (2012). Psychometric properties of the GAD-Q-IVand DERS in older, community-dwelling GAD patients and controls. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Kumar G, & Beck AT (2003). Beck depression inventory-II items associated with self-reported symptoms of ADHD in adult psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80, 58–63. do i: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2001). We know some things: parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain JE (2011). The human parental brain: In vivo neuroimaging. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 35, 1242–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein J, Roosa MW, & Michaels M (1994). Agreement between parent and child reports on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 341–355. doi: 10.2307/353104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, & Lewis C (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Hechtman L, & Weiss G (2000). ADHD in parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1059–1061. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]