Abstract

Background

Opioids remain the mainstream therapy for post-surgical pain. The choice of opioids administered by patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) for thoracoscopic lung surgery is unclear. This study compared 3 opioid analgesics for achieving satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis (SAME).

Methods

This randomized clinical trial enrolled patients scheduled for thoracoscopic lung surgery randomized to receive 1 of 3 opioids for PCIA: oxycodone (group O), hydromorphone (group H), and sufentanil (group S). The primary outcome was the proportion of subjects achieving SAME, i.e., no-to-mild pain (pain score < 4/10) with minimal nausea/vomiting (PONV score < 2/4) when coughing during the pulmonary rehabilitation exercise in the first 3 postoperative days.

Results

Of 555 enrolled patients, 184 patients in group O, 186 in group H and 184 in group S were included in the final analysis. The primary outcome of SAME was significantly different among group O, H and S (41.3% vs 40.3% vs 29.9%, P = 0.043), but no difference was observed between pairwise group comparisons. Patients in groups O and H had lower pain scores when coughing on the second day after surgery than those in group S, both with mean differences of 1 (3(3,4) and 3(3,4) vs 4(3,4), P = 0.009 and 0.039, respectively). The PONV scores were comparable between three groups (P > 0.05). There were no differences in other opioid-related side effects, patient satisfaction score, and QoR-15 score among three groups.

Conclusions

Given clinically relevant benefits detected, PCIA with oxycodone or hydromorphone is superior to sufentanil for achieving SAME as a supplement to multimodal analgesia in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery.

Trial registration

This study was registered at (ChiCTR2100045614, 19/04/2021).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12871-022-01785-4.

Keywords: Thoracoscopic surgery, Postoperative acute pain, Postoperative nausea and vomiting, Opioid

Introduction

Although minimally invasive techniques are increasingly popular, postoperative pain is one of the most common complaints from patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Of note, patients can still experience moderate-severe pain after VATS [1, 2]. Pain relief after VATS continues to be a challenging issue for anesthesiologists caring for these patients. Satisfactory postoperative pain management is crucial to assuring good patient experience, optimizing postoperative outcomes, enhancing functional recovery after surgery, and potentially decreasing the risk of developing chronic pain [3].

Current approaches for postoperative pain management, are increasingly centered on non-opioid approaches after VATS. For instance, epidurals have classically been recognized as the gold standard for pain management in thoracic surgery [4] and more recently, paravertebral blocks [5, 6]. Although the concept of opioid sparing, or multimodal analgesia has been recommended by guidelines and widely practiced [7–9], the use of patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) with opioid is generally the method of choice for pharmacologic pain control [10]. Moreover, opioid analgesics are the historical mainstay for postoperative cardiothoracic surgery pain relief and remain an essential and reliable analgesic for treating moderate to severe pain [11, 12]. However, opioid for postoperative analgesia is a matter of dispute in contemporary practice. Opioid administration is of concern and accompanied with many adverse effects, including postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), constipation, urinary retention, respiratory depression and delirium [13–16]. Therefore, it is more important to control postsurgical pain while minimizing opioid-related morbidity [17].

Oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil are potent opioid analgesics used to treat postoperative pain [18, 19]. However, no standardized and optimal opioid treatment for postoperative pain after VATS has been established so far. Consequently, there is a need to determine the most appropriate systemic opioid analgesia to control pain after VATS.

We designed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare 3 opioids PCIA for achieving satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis (SAME) in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery.

Methods

Ethics and registration

This three-arm RCT was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Ethical number: 2020[1327]). The protocol was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ChiCTR2100045614, 19/04/2021). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study protocol followed the CONSORT guidelines.

Participants

We recruited participants scheduled VATS resection of lung nodules at West China Hospital of Sichuan University, from April 2021 to November 2021. Patients were eligible for participation if they met the following criteria: age 18 years or older; American Society of Anesthesiologists statuses I-III; elective thoracoscopic lung surgery. Exclusion criteria were as follows: refusal to participate in the study, known allergies to study drugs or sulfonamides, renal or liver impairment, sleep apnea syndrome, chronic obstructive airway disease, bronchial asthma, ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, active gastrointestinal ulcer or bleeding or inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy or breast-feeding, refuse to use PCIA.

Randomization and blinding

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups (oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil) in a 1:1:1 ratio by computer-generated random permuted blocks of size 6. The blocks of random numbers were generated and put in opaque envelopes, each with a screen number on the front of the envelope. Participants, surgeons, and evaluators assessing outcomes were blinded throughout the study. The investigator opened the envelopes before the end of the surgery and prepared the PCIA pump accordingly. The analgesic pump was put into an opaque portable bag and connected at the end of the surgery. The nurses in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) and ward who was responsible for the PCIA knew the grouping.

Anesthesia and intraoperative care

All participants were monitored with electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, bispectral index electrodes and noninvasive blood pressure. Anesthesia management protocol was based on guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery [8]. General anesthesia was induced with propofol 1.5 ~ 2.0 mg/kg, sufentanil 0.3–0.5ug/kg, cisatracurium 0.2 mg/kg or rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg. After intubation with a double-lumen tube, lung protective ventilation strategies were adopted as described before [20]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (unless contraindicated) was given intravenously before skin incision. During the operation, anesthesia was achieved with propofol or sevoflurane or desflurane to maintain bispectral index level at 40–60. Intraoperative analgesia was provided with remifentanil and sufentanil. Muscle relaxation monitoring was conducted to guide the use of muscle relaxant and the reversal of neuromuscular blockade. A maintenance crystalloid was administrated throughout the procedure at 4–6 ml/kg/h. Prior to dermal closure, multiple-level, single-injection, unilateral intercostal nerve blocks of T3 to T8 with 20 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine were performed by the surgical team under direct thoracoscopic visualization. At the end of surgery, 5 mg tropisetron was injected intravenously.

Interventions and postoperative management

PCIA was applied to all patients for postoperative pain relief. Patients were randomly assigned to receiving PCIA containing oxycodone 0.5 mg/ml (group O), hydromorphone 0.05 mg/ml (group H) or sufentanil 0.5 μg/ml (group S) combined with tropisetron 5 mg in 100 ml normal saline. The PCIA was set to deliver 4 ml boluses, a 10-min lockout window, no basal infusion dose. All patients in the study were informed beforehand of the PCIA method in the pre-anesthetic appointment. Patients were instructed to press the PCIA in case of emerging pain. PCIA was maintained until patient was discharged from hospital, liquid used up with no request for further PCIA, or withdrawal due to adverse events. Parecoxib i.v. 40 mg was administered every 8 h in the first 3 days after surgery (flurbiprofen 50 mg if contraindicated). If there were numerical rating scale (NRS) pain scores > 3 and no pain relief by pressing the PCIA, the patient was administered i.v. dezocine 5 mg as rescue analgesics. PONV score ≥ 2 were treated with i.v. metoclopramide 10 mg.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was defined as the proportion of subjects achieving SAME, i.e., no-to-mild pain (pain score < 4) with minimal nausea/vomiting (PONV score < 2) when coughing during the pulmonary rehabilitation exercise in the first 3 postoperative days. Pain score was assessed on an 11-point NRS (0 = no pain, 0 < NRS < 4 (mild pain), 4 ≤ NRS < 7 (moderate pain), NRS ≥ 7 (severe pain), 10 = worst pain imaginable). The PONV score was defined as follows: 0 = no nausea, 1 = mild nausea (no treatment needed), 2 = moderate nausea or retching (may need treatment), 3 = frequent vomiting (controlled with anti-emetics), and 4 = severe vomiting (uncontrolled with anti-emetics). Key secondary outcomes included pain scores at rest and when coughing, and PONV scores within 3 days after surgery. Other secondary outcomes included the proportion of SAME at rest in the first 3 postoperative days, the total dose of opioids in morphine equivalents, the dose of opioids of PCIA in morphine equivalents, quality of recovery-15 (QoR-15) score, other opioid-related adverse events, and expectation pain score fulfilled on POD1-3, patient satisfaction score on pain control and the length of stay (LOS) in hospital.

At the end of surgery, the patients were transferred to PACU. Pain scores and PONV scores were assessed after tracheal tube removal at PACU by a trained nurse. After the patients returned to the ward, the pain score and PONV score were immediately assessed by a trained nurse, and then assessed every 4 h. Within the first 3 days after surgery, patients were followed up by a trained investigator between 17:00 to 19:00 every day. The investigator recorded the patient’s average pain score and PONV score within the past 24 h according to the nursing records. Patient satisfaction score (0 = dissatisfied and 100 = very satisfied) on pain control, QoR-15 score (ranging from 0 to 150), other opioid-related adverse events, and expectation NRS fulfilled by asking the patient whether the pain was acceptable or not were also recorded.

Sample size calculation

The sample size estimation was based on previous research data in our center, in which.

the proportion of SAME was 33% in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery with PCIA (sufentanil 3 μg/kg + tropisetron 15 mg + dexmedetomidine 200 μg in 200 ml normal saline, infusion rate of 2 ml/h) [2]. We hypothesized that 50% of patients achieving SAME would be clinically significant when using the trial interventions. The sample size of 555 was calculated by using PASS15.0, with a 2-tailed type I error rate of 0.0167, a power of 80%, and an anticipated 5% exclusion rate.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0) was used for statistical analysis. The analysis was conducted by intent-to-treat. Per-protocol analysis of the primary outcome was also performed. Normality of the data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normal continuous baseline variables are presented as the mean (standard deviation [SD]), and non-normal continuous variables are presented as median and quartiles, categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. For global group comparisons of variables, continuous data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance or the Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate, and the R*C Chi-square test was used for comparison of proportions. Specifically, generalized estimating equations with robust standard error estimates were used to account for repeated measures of pain scores and QoR-15 scores. For primary and secondary outcomes, if R*C Chi-square test or the Kruskal–Wallis test results were significant, pairwise group comparisons were performed by Chi-square test or Mann–Whitney U tests, and Bonferroni correction was applied. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

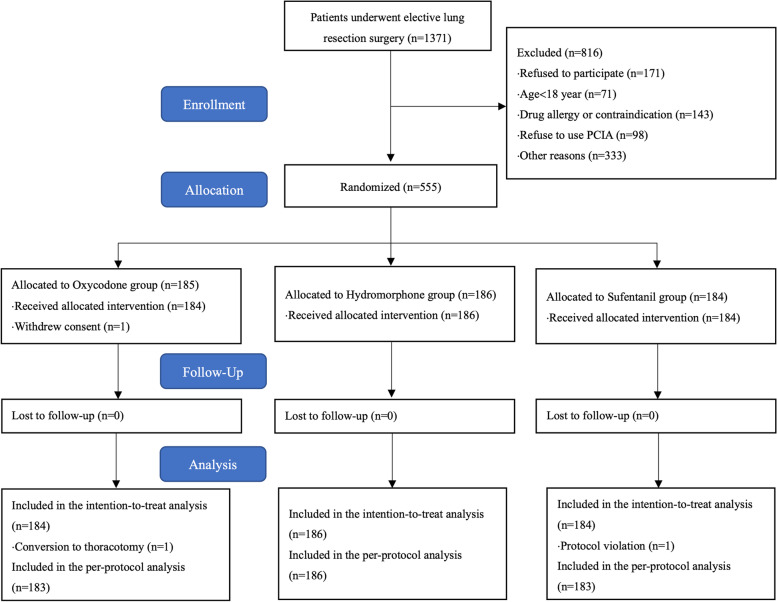

Of 1371 potentially eligible patients, 555 patients were randomized into the study (Fig. 1). Because one patient in group O withdrew consent after randomization, a total of 554 patients were analyzed with the intent-to-treat principle. One patient was excluded from per-protocol analysis because of conversion to thoracotomy and one protocol violation (not receiving the postoperative analgesia as assigned). The baseline characteristics, and relevant intraoperative and PACU variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Consort flowchart. PCIA, patient-controlled intravenous analgesia

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristics | Oxycodone group (n = 184) | Hydromorphone group (n = 186) | Sufentanil group (n = 184) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, no. (%) | 74(40.2) | 66(35.5) | 58(31.5) | 0.219 |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 53.1(10.6) | 53.5(12.5) | 51.6(12.6) | 0.282 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 22.93(2.89) | 22.94(2.79) | 22.71(2.87) | 0.677 |

| ASA physical status, no. (%) | 0.379 | |||

| I | 1(0.5) | 1(0.5) | 2(1.1) | |

| II | 171(92.9) | 163(87.6) | 163(88.6) | |

| III | 12(6.5) | 22(11.8) | 19(10.3) | |

| IV-V | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Smoking status, no. (%) | 0.295 | |||

| Never | 145(78.8) | 157(84.4) | 155(84.2) | |

| Former | 36(19.6) | 29(15.6) | 27(14.7) | |

| Current | 3(1.6) | 0(0.0) | 2(1.1) | |

| Apfel risk factors for PONVa, no. (%) | 0.218 | |||

| 1 | 38(20.7) | 24(12.9) | 24(13.0) | |

| 2 | 38(20.7) | 41(22.0) | 37(20.1) | |

| 3 | 103(56.0) | 111(59.7) | 118(64.1) | |

| 4 | 5(2.7) | 10(5.4) | 5(2.7) | |

| History of chronic pain, no. (%) | 9(4.9) | 13(7.0) | 20(10.9) | 0.089 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 30(16.3) | 27(14.5) | 31(16.8) | 0.814 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 14(7.6) | 14(7.5) | 8(4.3) | 0.350 |

| Chronic bronchitis or emphysema, no. (%) | 15(8.2) | 25(13.4) | 21(11.4) | 0.261 |

| Expected maximal pain on coughb, median (IQR) | 4(4,5) | 4(4,5) | 4(4,5) | 0.831 |

| Expected maximal pain at restb, median (IQR) | 2(2,2) | 2(2,2) | 2(2,2) | 0.784 |

| Expected average painb, median (IQR) | 3(3,3) | 3(3,3) | 3(3,3) | 0.778 |

| QoR-15 score, median (IQR) | 142(139,144) | 142(139,144) | 143(139,144) | 0.539 |

Data are presented as the mean (SD), median (IQR), or number (%)

Abbreviations: ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI body mass index, IQR interquartile range, PONV postoperative nausea and vomiting, QoR-15 Quality of Recovery-15 questionnaire, SD standard deviation

aApfel risk factors for PONV: female sex, previous history of postoperative nausea and vomiting or motion sickness, being a nonsmoker, and expected use of post-operative opioids for analgesia

bPain rated on a 0–10 numerical rating scale

Table 2.

Surgery and anesthesia data; pain score, rescue analgesics and PONV in the PACU

| Characteristics | Oxycodone group (n = 184) | Hydromorphone group (n = 186) | Sufentanil group (n = 184) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery, no. (%) | 0.693 | |||

| Lobectomy | 85(46.2) | 83(44.6) | 75(40.8) | |

| Segmentectomy | 47(25.5) | 55(29.6) | 59(32.1) | |

| Wedge resection | 52(28.3) | 48(25.8) | 50(27.2) | |

| Single-port thoracoscopy, no. (%) | 59(32.1) | 53(28.5) | 60(32.6) | 0.649 |

| Malignant lesion, no. (%) | 131(71.2) | 144(77.4) | 144(78.3) | 0.226 |

| Duration of surgery, min, median (IQR) | 91(64,122) | 88(70,114) | 90(70,117) | 0.878 |

| Anesthesia maintenance, no. (%) | 0.554 | |||

| Volatile anesthetics | 152(82.6) | 152(81.7) | 150(81.5) | |

| Propofol | 13(7.1) | 21(11.3) | 17(9.2) | |

| Volatile anesthetics combined with propofol | 19(10.3) | 13(7.0) | 17(9.2) | |

| Dose of sufentanil, μg/kg, median (IQR) | 0.5(0.4,0.6) | 0.5(0.4,0.6) | 0.5(0.5,0.6) | 0.029 |

| Dose of remifentanil, μg/kg/min, median (IQR) | 0.1(0.1,0.2) | 0.1(0.1,0.2) | 0.1(0.1,0.2) | 0.457 |

| NSAIDs, no. (%) | 165(90.7) | 166(89.7) | 174(95.1) | 0.136 |

| Antiemetic, no. (%) | ||||

| Tropisetron | 173(94.0) | 169(90.9) | 167(91.3) | 0.474 |

| Methylprednisolone | 167(90.8) | 164(88.2) | 159(86.4) | 0.423 |

| Dexamethasone | 1(0.5) | 5(2.7) | 2(1.1) | 0.291 |

| Intercostal nerve block, no. (%) | 149(81.0) | 148(79.6) | 139(75.5) | 0.417 |

| Total fluid, mL/kg/h, median (IQR) | 2.9(2.2,3.9) | 3.1(2.3,3.9) | 3.1(2.2,3.9) | 0.777 |

| Pain score in PACU, median (IQR) | 1(0,2) | 1(0,2) | 1(0,2) | 0.752 |

| Rescue analgesics in PACU, no. (%) | 5(2.7) | 5(2.7) | 7(3.8) | 0.778 |

| PONV in PACU, no. (%) | 0.850 | |||

| 0 | 183(99.5) | 185(99.5) | 183(99.5) | |

| 1 | 1(0.5) | 0 | 1(0.5) | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1(0.5) | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are presented as the median (IQR) or number (%)

Abbreviations: IQR interquartile range, NSAIDS non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PACU Post-anesthesia care unit, PONV postoperative nausea and vomiting

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of SAME was significantly different among groups O, H and S (41.3% vs 40.3% vs 29.9%, P = 0.043), but no difference was observed between pairwise group comparisons; The SAME on POD 1 were significantly different among three groups (42.4% vs 40.9% vs 30.4%, P = 0.037), but no difference was observed between pairwise group comparisons; On POD 2, groups O (59.2% vs 43.5%, P = 0.007) and H (57.2% vs 43.5%, P = 0.02) had significantly more patients achieving SAME than group S; On POD 3, the proportion of patients achieving SAME were similar among three groups (90.2% vs 86.6% vs 86.4%, P = 0.452) (Table 3). For per-protocol analysis, the primary outcome had no change (Additional file 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of postoperative outcomes in the intention-to-treat analysis

| Outcomes | Oxycodone group (n = 184) | Hydromorphone group (n = 186) | Sufentanil group (n = 184) | P value |

P value O versus H/ O versus S/ H versus S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, SAME on cough, no. (%) | 76(41.3) | 75(40.3) | 55(29.9) | 0.043 | 1.000/0.071/0.114 |

| POD 1–3 Pain score < 4 on cough, no. (%) | 79(42.9) | 77(41.4) | 56(30.4) | 0.027 | 1.000/0.041/0.091 |

| POD 1–3 PONV score < 2, no. (%) | 173(94.0) | 168(90.3) | 167(90.8) | 0.372 | n/a |

| POD 1 SAME on cough, no. (%) | 78(42.4) | 76(40.9) | 56(30.4) | 0.036 | 1.000/0.055/0.117 |

| POD 2 SAME on cough, no. (%) | 109(59.2) | 107(57.5) | 80(43.5) | 0.004 | 1.000/0.007/0.020 |

| POD 3 SAME on cough, no. (%) | 166(90.2) | 161(86.6) | 159(86.4) | 0.451 | n/a |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| SAME at rest, no. (%) | 168(91.3) | 162(87.1) | 158(85.9) | 0.240 | n/a |

| POD 1–3 Pain score < 4 at rest, no. (%) | 177(96.2) | 175(94.1) | 173(94.0) | 0.566 | n/a |

| POD 1 SAME at rest, no. (%) | 168(91.3) | 162(87.1) | 158(85.9) | 0.240 | n/a |

| POD 2 SAME at rest, no. (%) | 182(98.9) | 183(98.4) | 181(98.4) | 1.000 | n/a |

| POD 3 SAME at rest, no. (%) | 183(99.5) | 186(100.0) | 184(100.0) | 0.664 | n/a |

| Total dose of opioid in morphine equivalents, mg, median (IQR) | 29.5(14.0,48.0) | 25.0(12.8,45.3) | 36.5(18.0,55.8) | 0.006 | 0.734/0.134/0.004 |

| Dose of opioid of PCA in morphine equivalents, mg, median (IQR) | 20.0(10.0,37.5) | 20.0(10.0,28.0) | 24.0(12.0,42.0) | 0.009 | 0.416/0.342/0.007 |

| Rescue analgesics during POD 1–3, no. (%) | 10(5.4) | 11(5.9) | 16(8.7) | 0.400 | n/a |

| Patient satisfaction score on pain control, median (IQR) | 97(93,100) | 96(92,100) | 97(92,100) | 0.768 | n/a |

| QoR-15 score, median (IQR) | |||||

| POD 1 | 126(121,130) | 126(120,130) | 126(119,130) | 0.561 | n/a |

| POD 2 | 133(130,136) | 132(129,135) | 132(129,135) | 0.217 | n/a |

| POD 3 | 139(136,140) | 138(136,140) | 138(136,140) | 0.718 | n/a |

| Chest tube duration, days, median (IQR) | 2(2,3) | 2(2,4) | 2(2,3) | 0.094 | n/a |

| Discharge time from hospital, days, median (IQR) | 3(3,4) | 4(3,5) | 3.5(3,5) | 0.041 | 0.043/0.227/1.000 |

| Other opioid-related adverse events, no. (%) | |||||

| Constipation | 66(35.9) | 57(30.6) | 65(35.3) | 0.506 | n/a |

| Dizziness | 50(27.2) | 45(24.2) | 32(17.4) | 0.073 | n/a |

| Pruritis | 2(1.1) | 3(1.6) | 1(0.5) | 0.875 | n/a |

| Urinary retention | 6(3.3) | 9(4.8) | 10(5.4) | 0.583 | n/a |

| Severe sedationa | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Respiratory depression | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| PCA withdrawal due to adverse events | 6(3.3) | 11(5.9) | 7(3.8) | 0.416 | n/a |

Data are presented as the median (IQR) or number (%)

Abbreviations: IQR interquartile range, PCA patient-controlled analgesia, POD postoperative day, PONV postoperative nausea and vomiting, QoR-15 Quality of Recovery-15 questionnaire, SAME satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis.

adefined as Ramsay sedation scale score of 5–6

Key secondary outcomes

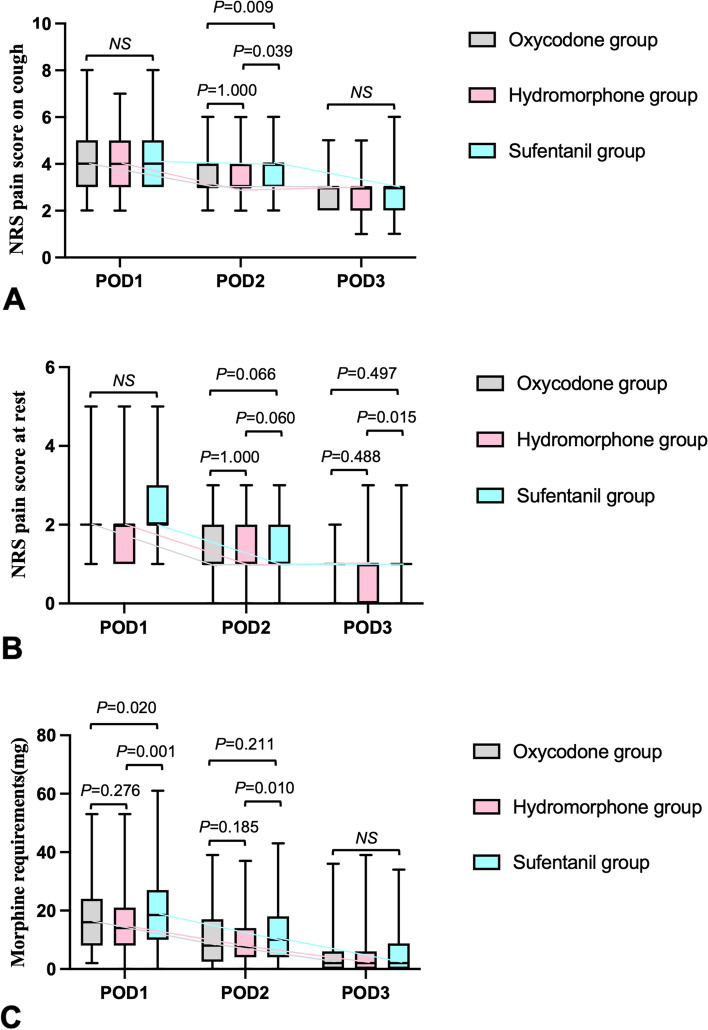

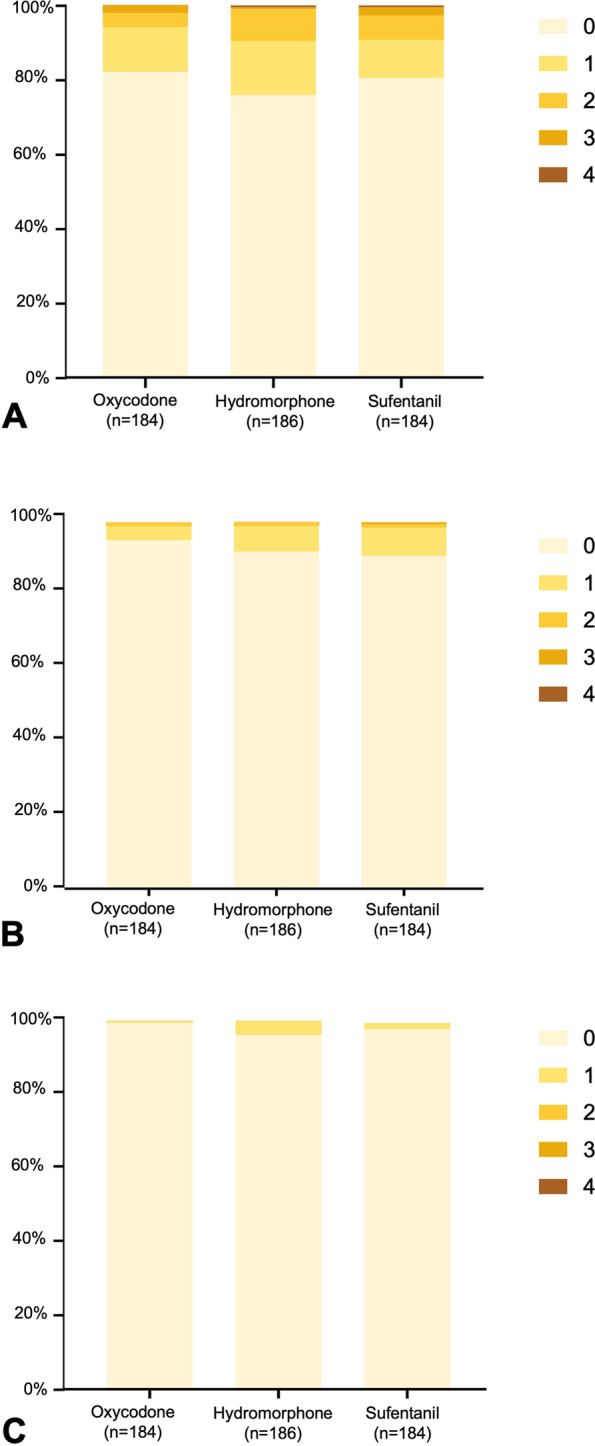

Patients in groups O and H had lower pain scores when coughing on POD2 than those in group S, both with mean differences of 1 (3(3,4) and 3(3,4) vs 4(3,4), P = 0.009 and 0.039, respectively) (Fig. 2). The PONV scores within 3 days after surgery were comparable among three groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of NRS pain scores and morphine requirements within 3 days after surgery among three groups. NRS, numerical rating scale; POD, postoperative day. Top and bottom of boxes indicate interquartile range; centerlines indicate medians; whiskers indicate range (minimum to maximum)

Fig. 3.

Comparison of PONV score among three groups. POD, postoperative day; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting. A POD 1; B POD 2; C POD 3

Other secondary outcomes

The SAME ratio at rest was similar during POD 1–3 (91.3% in group O vs 87.1% in group H vs 85.9% in group S, P = 0.24). Group H took less opioid both in total dose (25.0(12.8,45.3) mg vs 36.5(18.0,55.8) mg, P = 0.004) and in PCIA (20.0(10.0,28.0) mg vs 24.0(12.0,42.0) mg, P = 0.007) in morphine equivalents than group S. Subjects in all groups achieved a very good satisfaction score and QoR-15 score. Other opioid-related adverse events also were not significantly different among groups. Group O had shorter LOS after surgery than Group H (3(3,4) days vs 4(3,5) days, P = 0.043). The expectation NRS fulfilled (on cough, at rest, on average) within 3 days after surgery were comparable among three groups (P > 0.05) (Additional file 2).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical study, we found that the proportion of subjects achieving SAME within the first 3 days was of statistical significance among oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil for PCIA in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery. On POD 2, oxycodone and hydromorphone had significantly more patients achieving SAME than sufentanil; the pain scores when coughing on POD 2 were significantly lower in patients receiving hydromorphone or oxycodone than sufentanil; the PONV scores and other opioid-related adverse events within 3 days after surgery were comparable among three groups.

Perioperative pain management becomes increasingly important to the quality of surgical care [3]. Postoperative pain reduction is therefore one of the key elements of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program. Epidural analgesia may provide excellent pain relief, but is considered to be less necessary for a variety of less invasive surgical procedures, such as VATS [21]. Multimodal analgesia techniques, such as regional analgesia [22, 23], local anesthesia [24] and systemic analgesia are recommended [9]. Systemic opioids for pain treatment still gets mentioned in the latest WHO list of essential medicines for perioperative analgesia [10, 25]. Additionally, the opioid epidemic that may have originated in the US and Europe is not significant in China [10]. Considering a technical simplicity and less invasiveness of PCIA, this analgesic approach may be worthy of further research and is thus considered to have potential as a viable alternative to postoperative analgesia. So far, the existing literature is unclear about the choice of systemic opioid analgesia to be used postoperatively in thoracoscopic lung surgery [9].

To our knowledge, our trial is the first RCT to provide new evidence of PCIA with opioids (oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil). Considering the analgesic efficacy and the adverse event profile of opioids, our study focused on the proportion of satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis within the first 3 days after surgery. We found a 38% relative (11.4% absolute), or 35% relative (10.4% absolute) increase in the proportion of patients achieving SAME when compared oxycodone or hydromorphone with sufentanil, respectively, which was not statistically significant but, in our view, clinically relevant. Of note, more than half of patients receiving oxycodone (59.2%) or hydromorphone (57.5%) achieving SAME in the second day after surgery, and the differences reached statistically significant when compared to patients receiving sufentanil (43.5%). In addition, oxycodone or hydromorphone was superior to sufentanil for acute pain when comparing pain scores when coughing. In our view, this finding supported that the oxycodone or hydromorphone was superior to sufentanil for PCIA because clinically relevant benefits were detected. However, the existing studies that have compared oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil in surgical patients are limited. A recent meta-analysis evaluated the acute postoperative analgesic efficacy of intravenous oxycodone against other strong opioids in adult patients [26]. There were only three studies comparing oxycodone with sufentanil, and no eligible studies comparing oxycodone with hydromorphone. Consistent with our finding, they observed oxycodone exhibited better analgesic efficacy than sufentanil, with comparable incidence of nausea.

Although PONV is typically considered an inherent side-effect of opioid-based analgesia, our study showed that more than 90% patients had no or mild nausea (PONV score < 2) within the first 3 days after surgery. A previous study reported that a lower dose background infusion of oxycodone was associated with fewer PONV [27]. The relatively lower incidence of PONV found in our trial may be explained by no background infusion dose of opioids compared with published literature [28, 29]. Additionally, we found no significant difference among three study groups regarding PONV. This finding was consistent with a meta-analysis which showed that oxycodone, hydromorphone or sufentanil in equianalgesic doses via PCIA had no significant difference regarding PONV rates compared to morphine [15].

Our findings suggested that the incidence of other opioid-related adverse events was not significantly different among oxycodone, hydromorphone and sufentanil. Our reported incidence of constipation (33.9%) and dizziness (22.9%) were similar to Lee et al.’s study, in which constipation (28.9%) and dizziness (21.1%) were two most common side effects with opioid PCIA after thoracoscopic lobectomy [29]. Pruritus (1.1%) or urinary retention (4.5%) was observed in a small proportion of the study population, which was relatively lower compared to other literatures using fentanyl [29], morphine [30] or hydromorphone [31]. No sedation or respiratory depression was observed in our trial, which was more common with morphine [32, 33]. Although the adverse events occurred in a various proportion of patients, subjects in all groups achieved a very good satisfaction score, QoR-15 score and expectation NRS fulfilled rate. Given that, our study supports that PCIA with systemic opioids is the effective and well tolerated approach with minimum adverse effects and good patient satisfaction.

This study had several limitations. First, as the treatment effect of oxycodone or hydromorphone was lower than anticipated (a relative increase of 50%) compared to sufentanil, the trial was possibly underpowered to assess the primary outcome, and therefore, should be considered a pilot study. Therefore, no strong conclusions could be drawn from the present work. Consequently, further studies are needed to confirm the superiority of oxycodone and hydromorphone when compared to sufentanil for PCIA. Second, a small proportion of patients were not strictly following the optimal pain treatments recommended by PROSPECT for VATS, including intercostal nerves block (21%) and NSAIDs intra-operatively (8.8%) [9]. However, the use of these treatments was similar among three groups. Additionally, in our trial, the average pain scores within the first 3 days were equal or less than 4 (considered the upper end of mild pain category), and about only 5% of patients suffered moderate-to-severe pain at rest, so the basic analgesic protocol in this trial could be optimal.

Conclusions

Given clinically relevant benefits detected, PCIA with oxycodone or hydromorphone was superior to sufentanil for achieving satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery. The PCIA with opioids is considered to have potential as a supplement to multimodal analgesia with technical simplicity and less invasiveness, and may be worthy of further research.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Comparison of postoperative outcomes in the per-protocol analysis. Dataare presented as the median (IQR) or number (%). Abbreviations: IQR, interquartilerange; PCIA, patient-controlled intravenous analgesia; POD, postoperative day;PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; QoR-15, Quality of Recovery-15questionnaire; SAME, satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis.

Additional file 2. Expectation on pain fulfilled rate. POD, postoperativeday. A. Expectation on cough fulfilled; B. Expectation at rest fulfilled; C.Expectation on average pain fulfilled.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the surgeons and nurses working in the thoracic surgery units for their involvement and support.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BIS

Bispectral index

- BMI

Body mass index

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- EtCO2

End-expiratory CO2

- FiO2

Fraction inspired oxygen

- I:E

Inspiratory-expiratory ratio

- IQR

Interquartile range

- ITT

Intent-to-treat

- LOS

Length of stay

- NRS

Numerical rating scale

- NSAIDS

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OLV

One-lung ventilation

- PACU

Post-anesthesia care unit

- PCIA

Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- POD

Postoperative day

- PONV

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- PP

Per-protocol

- QoR-15

Quality of Recovery-15 questionnaire

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SAME

Satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis

- SD

Standard deviation

- VATS

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

- VT

Tidal volume

Authors’ contributions

HY1 (Hong Yu) and WT contributed equally to this work. HY2 (Hai Yu) have given substantial contributions to the conception or the design of the manuscript, RJJ, LJ, WJM, YC to collection of the data, WT and ZX to analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have participated to drafting the manuscript, and HY1, WT and HY2 revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Ethical number: 2020[1327]) and registered at http://www.chictr.org.cn (19/04/2021, ChiCTR2100045614). The study protocol followed the CONSORT guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hong Yu and Wei Tian contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Holbek BL, Horsleben Petersen R, Kehlet H, Hansen HJ. Fast-track video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: future challenges. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2016;50(2):78–82. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2015.1114665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi W, Chen Y, Zhang MQ, Che GW, Yu H. Effects of methylprednisolone on early postoperative pain and recovery in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2021;75:110526. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi GP, Van de Velde M, Kehlet H. Development of evidence-based recommendations for procedure-specific pain management: PROSPECT methodology. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(10):1298–1304. doi: 10.1111/anae.14776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zejun N, Wei F, Lin L, He D, Haichen C. Improvement of recovery parameters using patient-controlled epidural analgesia for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy in enhanced recovery after surgery: A prospective, randomized single center study. Thorac Cancer. 2018;9(9):1174–1179. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeap YL, Wolfe JW, Backfish-White KM, Young JV, Stewart J, Ceppa DP, Moser EAS, Birdas TJ. Randomized Prospective Study Evaluating Single-Injection Paravertebral Block, Paravertebral Catheter, and Thoracic Epidural Catheter for Postoperative Regional Analgesia After Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(7):1870–1876. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang QW, Li JB, Huang Y, Zhang WQ, Lu ZW. A Comparison of Analgesia After a Thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Operation with a Sustained Epidural Block and a Sustained Paravertebral Block: A Randomized Controlled Study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):4000–4014. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccioni F, Segat M, Falini S, Umari M, Putina O, Cavaliere L, Ragazzi R, Massullo D, Taurchini M, Del Naja C, et al. Enhanced recovery pathways in thoracic surgery from Italian VATS Group: perioperative analgesia protocols. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 4):S555–s563. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.12.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Brunelli A, Cerfolio RJ, Gonzalez M, Ljungqvist O, Petersen RH, Popescu WM, Slinger PD, et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55(1):91–115. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feray S, Lubach J, Joshi GP, Bonnet F, Van de Velde M. PROSPECT guidelines for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(3):311–25. 10.1111/anae.15609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Macintyre PE, Quinlan J, Levy N, Lobo DN. Current Issues in the Use of Opioids for the Management of Postoperative Pain: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(2):158–66. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6210. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wehrfritz A, Ihmsen H, Fuchte T, Kim M, Kremer S, Weiß A, Schüttler J, Jeleazcov C. Postoperative pain therapy with hydromorphone; comparison of patient-controlled analgesia with target-controlled infusion and standard patient-controlled analgesia: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020;37(12):1168–1175. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LM, Kratz A, Verba S, Tancredi D, Clauw DJ, Palmieri T, Williams D. Pain and Opioid Use After Thoracic Surgery: Where We Are and Where We Need To Go. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(6):1638–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frauenknecht J, Kirkham KR, Jacot-Guillarmod A, Albrecht E. Analgesic impact of intra-operative opioids vs. opioid-free anaesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(5):651–662. doi: 10.1111/anae.14582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer HD, Detriche O, Forget P. Opioid-related side effects: Postoperative ileus, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, and shivering. A review of the literature. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31(4):499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinges HC, Otto S, Stay DK, Bäumlein S, Waldmann S, Kranke P, Wulf HF, Eberhart LH. Side Effect Rates of Opioids in Equianalgesic Doses via Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(4):1153–1162. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swart LM, van der Zanden V, Spies PE, de Rooij SE, van Munster BC. The Comparative Risk of Delirium with Different Opioids: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(6):437–443. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanthanna H, Paul J, Lovrics P, Vanniyasingam T, Devereaux PJ, Bhandari M, Thabane L. Satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis in day surgeries: a randomised controlled trial of morphine versus hydromorphone. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(6):e107–e113. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y, Sun K, Xing X, Zhang F, Sun N, Gao Y, Zhu L, Yao J, Fan J, Yan M. Postoperative analgesic effect of hydromorphone in patients undergoing single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1091–1101. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S194541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitra S, Carlyle D, Kodumudi G, Kodumudi V, Vadivelu N. New Advances in Acute Postoperative Pain Management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22(5):35. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XF, Hu JR, Wu Y, Chen Y, Zhang MQ, Yu H. Comparative Effect of Propofol and Volatile Anesthetics on Postoperative Pulmonary Complications After Lung Resection Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(4):949–957. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehlet H, Joshi GP. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials on Perioperative Outcomes: An Urgent Need for Critical Reappraisal. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(4):1104–1107. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciftci B, Ekinci M, Celik EC, Tukac IC, Bayrak Y, Atalay YO. Efficacy of an Ultrasound-Guided Erector Spinae Plane Block for Postoperative Analgesia Management After Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(2):444–449. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Ni XX, Zhang LW, Zhao K, Xie H, Zhu J. Effects of ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block on postoperative analgesia and plasma cytokine levels after uniportal VATS: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Anesth. 2021;35(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed Z, Samad K, Ullah H. Role of intercostal nerve block in reducing postoperative pain following video-assisted thoracoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11(1):54–57. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.197342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organization WH. WHO model lists of essential medicines March 2017 [updated August 2017, 20th Edn.]. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

- 26.Raff M, Belbachir A, El-Tallawy S, Ho KY, Nagtalon E, Salti A, Seo JH, Tantri AR, Wang H, Wang T, et al. Intravenous Oxycodone Versus Other Intravenous Strong Opioids for Acute Postoperative Pain Control: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Ther. 2019;8(1):19–39. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-0122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Yan W, Chen Y, Fan Z, Chen J. Lower Background Infusion of Oxycodone for Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia, Combined with Ropivacaine Intercostal Nerve Block, in Patients Undergoing Thoracoscopic Lobectomy for Lung Cancer: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:3535–3542. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S316583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Z, Fang S, Wang Q, Wu C, Zhan T, Wu M. Patient-Controlled Paravertebral Block for Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(3):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CY, Narm KS, Lee JG, Paik HC, Chung KY, Shin HY, Yeom HY, Kim DJ. A prospective randomized trial of continuous paravertebral infusion versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(6):3814–3823. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giang NT, Van Nam N, Trung NN, Anh LV, Cuong NM, Van Dinh N, Pho DC, Geiger P, Kien NT. Patient-controlled paravertebral analgesia for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:115–121. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S184589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Wu J, Li H, Ye S, Xu X, Cheng L, Zhu L, Peng Z, Feng Z. Prospective investigation of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone or sufentanil: impact on mood, opioid adverse effects, and recovery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0500-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenz H, Sandvik L, Qvigstad E, Bjerkelund CE, Raeder J. A comparison of intravenous oxycodone and intravenous morphine in patient-controlled postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(4):1279–1283. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b0f0bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodarzi M. Comparison of epidural morphine, hydromorphone and fentanyl for postoperative pain control in children undergoing orthopaedic surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 1999;9(5):419–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1999.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Comparison of postoperative outcomes in the per-protocol analysis. Dataare presented as the median (IQR) or number (%). Abbreviations: IQR, interquartilerange; PCIA, patient-controlled intravenous analgesia; POD, postoperative day;PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; QoR-15, Quality of Recovery-15questionnaire; SAME, satisfactory analgesia with minimal emesis.

Additional file 2. Expectation on pain fulfilled rate. POD, postoperativeday. A. Expectation on cough fulfilled; B. Expectation at rest fulfilled; C.Expectation on average pain fulfilled.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.