Abstract

Objectives

Young adults report disproportionality greater mental health problems compared with the rest of the population with numerous barriers preventing them from seeking help. Peer support, defined as a form of social-emotional support offered by an individual with a shared lived experience, has been reported as being effective in improving a variety of mental health outcomes in differing populations. The objective of this scoping review is to provide an overview of the literature investigating the impact of peer support on the mental health of young adults.

Design

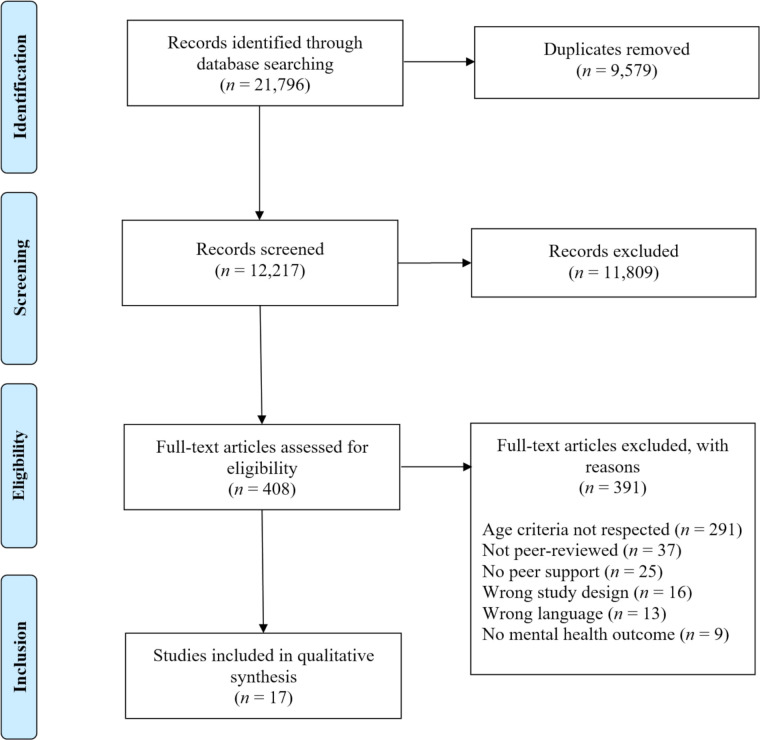

A scoping review methodology was used to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines across six databases and Google/Google Scholar. Overall, 17 eligible studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Results

Overall, studies suggest that peer support is associated with improvements in mental health including greater happiness, self-esteem and effective coping, and reductions in depression, loneliness and anxiety. This effect appears to be present among university students, non-student young adults and ethnic/sexual minorities. Both individual and group peer support appear to be beneficial for mental health with positive effects also being present for those providing the support.

Conclusions

Peer support appears to be a promising avenue towards improving the mental health of young adults, with lower barriers to accessing these services when compared with traditional mental health services. The importance of training peer supporters and the differential impact of peer support based on the method of delivery should be investigated in future research.

Keywords: depression & mood disorders, mental health, child & adolescent psychiatry, adult psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Literature from six electronic databases and Google/Google Scholar were screened to comprehensively describe the literature.

Inclusion criteria were developed based on clear definitions of peer support, mental health and young adulthood.

Only published peer-reviewed research articles in English or French were included.

Inconsistencies in the ways peer support and mental health were measured make it difficult to synthesize results across studies.

Background

Young adults, aged 18–25, are disproportionality affected by mental health disorders when compared with the rest of the population.1 The transition to university often coincides with young adulthood and a peak of mental illness onset due to decreased support from family and friends, increased financial burden, loneliness and intense study periods.2–4 Psychological and emotional problems in university students have been on the rise, both in frequency and severity.5–7 In fact, psychological distress has been reported as being significantly higher among university students compared to their non-student peers.8–11 For instance, the WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project surveyed 13,984 undergraduate freshman students across eight countries and found that one-third of students had an anxiety, mood or substance use disorder.12 Moreover, university students face a host of academic, interpersonal, financial and cultural challenges.10 13–15 Due to the chronic nature of mental health issues, poor mental health in university students has the potential to result in significant future economic consequences on society. This is both at an indirect level in terms of absenteeism, productivity loss and underperformance, as well as at a direct level in terms of the need for hospital care, medication, social services and income support.16 Additionally, depression, substance use disorders and psychosis are the most important psychiatric risk factors for suicide.17 The high prevalence of psychological distress indicates the importance of developing and establishing programmes that address such problems.13

Previous research indicates that between 45% and 65% of university students experiencing mental health problems do not seek professional help.10 18 19 Barriers to mental health help-seeking among university students include denial, embarrassment, lack of time and stigma.20 21 As a result, university students often choose informal support from family and friends, or other resources, such as self-help books and online sites.22 In addition, when students do reach out to counselling services, long wait lists are frequently listed as an obstacle for receiving help.22 These attitudes and the barriers associated with help seeking behaviors must be addressed when providing supportive services.

Currently, universities are more challenged than ever when it comes to providing cost-effective and accessible services that meet the broad range of concerns faced by their student population. Beyond counselling and psychiatric services, an emerging resource for help-seeking young adults is peer support. Peer support, in the context of mental health, has previously been defined as a form of social-emotional support offered by an individual who shares a previously lived experience with someone suffering from a mental health condition in an environment of respect and shared responsibility.23 Various forms of peer support exist; they can be classified based on the setting in which peer support is provided (eg, hospital, school, online), the training of the individual offering the service (eg, prior training in active listening/supportive interventions, no previous training), shared characteristic or past experience(s) between the supporter or person receiving support, and/or the administration overseeing the service.23 Furthermore, peer support has been identified as having the potential to serve individuals, for example, ethnic and sexual minorities, who are in need of mental health services yet feel alienated from the traditional mental health system.24

Reviews of the outcomes of peer support interventions for individuals with severe mental illness have generally come to positive conclusions, yet results are still tentative given the infancy of this research area.25–28 Beyond the effects to those receiving support, there are also promising findings related to the benefits of providing peer support.29 30 Some of the positive reported outcomes include improvements in self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-management and in the recovery from addiction or bereavement.31–33 Nevertheless, findings are mixed when it comes to the effects of peer support. In a systematic review investigating the role of online peer support (ie, internet support groups, chat rooms) on the mental health of adolescents and young adults, only two of the four randomised trials reported improvements in mental health symptoms, with the two other studies included in the review showing a non-statistically significant decrease in symptoms.34

Overall, these results indicate the need for reviews that are broader in scope which can nuance the effects of different forms of peer support (eg, online vs in-person; individual vs group) on specific mental health outcomes among young adults. Moreover, as a number of challenges are present in the evaluation of peer support services (eg, difficulties with random assignment, varied roles of peer supporters, differences in training and supervision), it is critical to evaluate the state of the peer-reviewed research evidence as it relates to these variables.35 As such, the primary aim of this review was to synthesize the available peer-reviewed literature regarding the relationship between peer support and mental health among young adults. The following research questions were established for this scoping review: (1) How is peer support being delivered to young adults? and (2) What is the effect of peer support on the mental health of young adults?

Methods

Patient and public involvement

This study is a scoping review based on study-level data and no patients were involved in the study.

Search strategy

A scoping review is a systematic approach to mapping the literature on a given topic. The aims of scoping reviews generally include determining the breadth of available literature and identifying gaps in the research field of interest. An iterative approach was taken to develop the research questions for the present scoping review, which included identifying relevant literature, such as reviews and editorials, and having discussions with stakeholders who have firsthand experience with university peer support centres. The present scoping review is congruent with the recommended six-step methodology as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley36 and follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for Scoping Reviews.

To methodically search for peer-reviewed literature addressing these research questions, a broad search strategy was developed and employed across several databases. In January 2021, the following databases were searched for studies published up to the end of December 2020: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL and SocIndex. The search terms used were centred around three principal topics: peer support, mental health and young/emerging adulthood. An example of the search strategy is provided in table 1. Previous literature reviews on related topics, as well as discussions with research librarians, were used to help inform these terms. Additionally, a search was conducted in January 2021 and included the top 50 results from Google and Google Scholar. All articles were imported to EndNote and were uploaded to the Covidence Systematic Review Software for removal of duplicates.

Table 1.

Keywords for database searches

| Grouping terms | Keywords |

| Peer support | (“peer support” OR “online peer support” OR “peer to peer” OR “peer counsel*” OR “peer mentor*” OR “support group*” OR “emotional support” OR “psychological support” OR “help seeking” OR “peer support cent*” OR “peer communication” OR “social support”) AND |

| Mental health | (“mental health” OR “college mental health” OR “university mental health” OR “student mental health” OR “emotional well*being” OR “psychological well*being” OR “social isolation” OR loneliness OR stress OR “psychological distress” OR “psychological stress” OR “academic stress” OR depression OR “depressive symptoms” OR anxiety OR “anxious symptoms” OR suicide* OR grief OR “psychological resilience”) AND |

| Young/emerging adulthood | (“young adulthood” OR “emerging adulthood”) |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility for study inclusion in the present review was based on the following criteria: original peer-reviewed articles published in English or French; participants or specified groups of participants within a study aged 18 to 25 (if range not reported, the mean age had to fall between 18 and 25, with a SD ±1.75); measured or assessed the provision of peer support (defined as social or emotional support that is provided by people sharing similar experiences to bring about a desired emotional or psychological change) or peer mentoring; assessed a mental health outcome (ie, mental health, depression, anxiety, mood, suicidality, loneliness/social isolation, grief, psychological or academic stress, psychological, emotional well-being, self-esteem, resilience and psychological or emotional coping); and described a relationship between peer support and the mental health outcome of either the supporters (ie, individuals providing peer support) or supportees (ie, individuals receiving peer support). No limitations were included specific to geographic location of the study.

Studies were excluded if they: were literature reviews, study protocols, dissertations, case reports or presentations/conference abstracts; assessed social support more generally or as provided by non-peers (eg, family members, mental healthcare providers); assessed other forms of peer communication that were not defined as peer support; or investigated the association between peer support and non-mental health outcomes (eg, medical, social or occupational variables).

Study selection

Screening of titles and abstracts was performed by two independent reviewers (JR, RR, JEAC, AC, KW, SK, AK and MS) using the described eligibility criteria using the Covidence Systematic Review Software. Subsequently, full text screening of remaining articles was also carried out by two independent reviewers (JR, RR, JEAC, AC, KW, SK and MS). At both stages, conflicts were reviewed and resolved by an independent third screener (JR and RR).

Data collection

Data collection and extraction from each included article was conducted independently by two reviewers (JEAC, AC, AC, SK and MS) and consensus of extracted information was established. The following characteristics were extracted from each study: citation (including authors, title, and year of publication), study design, study objective(s), participant characteristics (eg, gender, age), type and delivery method of peer support, mental health outcomes measured, and main findings. Main reported findings include measures of effect size including Pearson correlation coefficients (r), standardized beta coefficients (β), beta coefficients (b) with SE and Cohen’s d. 90% or 95% confidence intervals (CE) and p values are also reported when applicable. These extracted characteristics were identified based on previous systematic and scoping reviews investigating peer support and/or mental health outcomes. No risk of bias assessment was completed as the purpose of conducting a scoping review is to better understand the breadth of a topic of study rather than evaluate study quality. Online supplemental appendix I presents a table with an overview of the included studies.

bmjopen-2022-061336supp001.pdf (94.7KB, pdf)

Results

Cumulatively, 21,796 articles were identified from the database searches. After duplicates were removed, 12,217 articles remained, and each title and abstract was reviewed. Of these, 408 passed on to full-text review, following which, 17 articles ultimately met criteria for inclusion. The overall search process and reasons for exclusion for the reviewed full-text articles are included in figure 1. Geographically, studies were carried out in the USA (n=10), Canada (n=3), the UK (n=3, with one study recruiting part of their sample from Portugal) and Pakistan (n=1). Most samples included university students (n=15), with the remaining studies including young adults from the general population (n=2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process for studies evaluating the impact of peer support the mental health of young adults. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Measurement of peer support

Overall, there appears to be significant variability in the methodology used to measure peer support. The most common method was through the use of validated self-report measures for perceived support coming from friends or peers. However, these assessment tools varied widely and included the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support,37 Perceived Social Support from Friends measure,38 Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment,39 Interpersonal Relationship Inventory40 and the Social Provisions Scale.41

Generally, these scales include items related to perceived social support (eg, “I get the help and support I need from my friends.”; “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.”; “When we discuss things, my friends care about my point of view.”; “Could you turn to your friends for advice if you were having a problem?”) with responses provided on Likert-type scales ranging from strongly disagree/never/no to strongly agree/always/yes.

One of the included studies coded interview responses for instances of perceived support42 and another conducted a qualitative analysis of online forum posts including themes of social support.43 Other studies quantitatively measured instances of emotional support,44 45 while others did not directly measure social support, but based their study on the fact that they were offering peer support services.46–48 Finally, three studies investigated the impact of peer support, not based on the response of supportees, but based on the experience of supporters.31 49 50

Measurement of mental health

The assessed mental health outcomes also varied, with some studies measuring a single outcome and others investigating several. While some of the included studies investigated the alleviation of negative psychological states, other studies researched the effects of peer support on positive psychological outcomes. Specifically, studies measured depression/depressive symptoms (n=8), anxiety (n=6), stress (n=3), negative affect (n=1), loneliness (n=1) and internalised homonegativity (n=1). One study measured various specific mental health problems including obsession–compulsion, somatisation, interpersonal sensitivity, phobic anxiety and hostility, in addition to depression and anxiety.51 As for positive psychological outcomes, although less common, some studies measured emotional and/or general well-being (n=3), self-esteem (n=2), mental health (n=1), happiness (n=1), flourishing (social, emotional, psychological; n=1), belonging (n=1), coping (n=1) and positive affect (n=1). Details regarding the instruments used to measure the mental health outcomes are provided in online supplemental appendix I.

Delivery of peer support and characteristics of supporters

Eleven of the included studies investigated peer support delivered individually and in-person,.44 45 48 49 51–57 Two studies investigated in-person group peer support,46 47 two studies investigated individual online peer support31 43 and one looked at helplines for individual peer support.50 Finally, a single study qualitatively investigated the importance and significance of peer support in a university setting.42

The roles of individuals providing peer support also varied greatly, with some studies including multiple different types of supporters. These roles included friends (n=8), significant others (n=3), other university students (n=4), volunteer peer supporters (n=2), mentors (n=2) and therapists-in-training/healing practitioners acting as peer supporters (n=1).

All individuals providing peer-support services in a group context or through helplines were trained.46 47 50 These individuals were less likely to be friends or family members and were more likely to be volunteer peer supporters or therapists-in-training. The studies investigating online peer support had both trained and untrained supporters, although untrained supporters had previous knowledge of additional resources for students experiencing depression.31 43

Effects of peer support on supportee mental health

Individual peer support

A total of nine studies investigated the impact of individual peer support on the mental health of young adults. Overall, peer support was significantly associated with various mental health benefits for supportees, including increases in happiness (β=0.38, p=0.03),49 self-esteem (r=0.40, p<0.01),53 problem focused coping strategies (β=0.17, p<0.01),57 as well as marginal reductions in loneliness (β = −0.49, p=0.06),49 depression (r=−0.12 to −0.32, p<0.05),51–53 and anxiety (r=−0.15, p<0.01).51 None of these studies included confidence intervals relevant to their measures of effect size. Moreover, qualitative analyses identified benefits of peer support such as a majority of students (77%) experiencing a sense of relief from their anxieties about dental school,48 nursing students experiencing decreases in anxiety regarding first experiences in hospital,56 and general improvements in the mental health and well-being of university students.42

One study did not identify a significant effect of peer support in reducing depressive symptoms based on an alpha level of 0.05.43 This study investigated the effect of an online peer support intervention for students by untrained supporters. Although a numerical decrease in depressive symptoms was present when the baseline to post-intervention scores were compared (mean Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D] scores from 37.0 to 33.5), this difference did not meet the threshold of statistical significance (p=0.13). Overall, these studies suggest that individual peer support generally has an effect on mental health, including increases in happiness, self-esteem and effective coping, and decreases in depression, loneliness and anxiety.

A total of three articles investigated the role of individual peer support on the mental health of specific minority groups including marginalised Latino undergraduates,54 lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) young adults,55 and sexual minority men.45 In the study investigating peer support among Latino students, Llamas and Ramos-Sánchez54 found that perceptions of support from peers significantly decreased the association between intragroup marginalisation and college adjustment, whereby intragroup marginalisation was no longer a significant predictor of college adjustment when social support was present (β = –0.17, p>0.05). Specific to LGB young adults, greater peer support was associated with reductions in depression (r=−0.28, p<0.05) and internalised homophobia (r=−0.30, p<0.05). It was also a significant moderator in the relationship between family attitudes and anxiety (β=0.26, 95% CI 0.002 to 1.154), as well as family victimisation and depression (β=−0.23, 95% CI −0.444 to –0.010).55 In other words, peer support buffered against the mental health consequences of negative family attitudes and family victimisation. Finally, Gibbs and Rice45 qualitatively identified factors associated with depression in sexual minority men. Of note, greater connections within the gay community (b=−0.01, SE=0.006, p=0.047) and the increased availability of emotional support (b=−0.35, SE=0.161, p=0.03) was associated with decreases in depressive symptoms. Overall, peer support appears to be beneficial for ethnic and sexual minorities, with noted improvements in college adjustment and decreases in anxiety and depression.

Group peer support

Two studies investigated the effect of group peer support on mental health.46 47 Both studies had predominantly female samples (70% and 77%, respectively) and featured trained peer supporters. Byrom46 identified that individuals with lower initial mental well-being participated in the peer support programme for longer and had greater increases in mental well-being from beginning to end of the programme (effect size of d=0.66, 95% CI [0.23 to 1.08] from baseline to week 3, and d=0.39, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.83] from week 3 to week 6). Specifically, attending a greater number of sessions was associated with greater improvements in well-being from baseline to follow-up 6 weeks later, while also increasing a supportee’s knowledge of mental health and ability to take care of their own mental health. Similarly, the study by Hughes et al47 found that young adults in outpatient care for psychological distress experienced decreases in severity of both depressive (p=0.003) and anxious (p=0.031) symptoms following group peer support; this improvement was maintained for up to 2 months post-treatment. Overall, group peer support appears to have a positive impact on increasing well-being and reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Effect of peer support on supporter mental health

Four studies investigated the effect of peer support on the individuals providing support. Two of these studies had untrained, in-person, individual peer supporters providing both emotional and instrumental support. These studies evaluated whether providing these types of support led to improvements in either affect or well-being.44 49 The first, by Armstrong-Carter et al44 noted that providing instrumental support to a friend resulted in greater positive affect that same day and across multiple days (r=0.17, p<0.001) if they continued providing this support. However, over extended periods of providing instrumental support, negative affect also increased (r=0.07, p<0.01), with this association being significantly moderated by gender (ie, negative affect was present for men but not for women). The second study by Morelli et al49 identified that emotional support had the greatest effect in decreasing loneliness (β = −0.29, p<0.01), stress (β = −0.17, p<0.01), anxiety (β = −0.14, p<0.01) and increasing happiness (β=0.25, p<0.01).

The remaining two studies investigated peer support provided by trained supporters either online31 or through helplines.50 Investigating the coping styles of peer supporters, Johnson and Riley30 found that following the peer support training, peer supporters reported a decrease in avoidance-based coping (d=0.51, p=0.02) and an increased sense of belonging (d=0.43, p=0.04). Pereira et al50 focused more on the effects of working for the helpline and noted that the two most stressful aspects of the work reported by peer supporters were waiting for calls and receiving calls concerning more serious topics (eg, suicidality). They noted that being supported by a colleague was a helpful way to cope with resulting distress. Overall, providing peer support appears to be beneficial to supporters although some aspects of the work may be distressing to some supporters.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to synthesize evidence describing and evaluating the impact of peer support on the mental health of young adults. According to published literature, peer support among young adults is being evaluated as delivered predominantly via in-person modality, though several studies investigated group peer support and other modalities of delivery (ie, over the internet or phone). The majority of studied peer support was provided by friends or significant others, although school peers and volunteer peer supporters were also represented in the included studies. Trained peer supporters were over-represented in the studies that investigated group-based, internet-based and telephone-based support compared with individual in-person peer support. Overall, these results indicate that there are multiple ways that peer support interventions could be delivered with positive results across modalities.

This scoping review represents an initial attempt at determining the breadth of the available literature on the effectiveness of peer support in addressing the mental health concerns of young adults. An initial review of the evidence by Davidson et al25 indicated that peer support groups may improve symptoms of severe mental illness, enhance quality of life and promote larger social networks. More recently, John et al26 conducted a systematic review of the literature specific to university students and they identified three studies with mixed findings related to mental well-being. The present review represents an updated summary and synthesis of the peer support literature as it relates to young adults irrespective of university status, which captures a broad array of mental health outcomes. Overall, results from the reviewed studies indicate that peer support has predominantly positive effects on the mental health outcomes of young adults including depressive symptoms, anxiety, psychological distress and self-esteem. Notwithstanding these results, there remains a paucity of controlled and prospective studies investigating the impact of peer support.

Peer support has been identified as an accessible, affordable and easy-to-implement mental health resource that has beneficial effects across populations.58 The long wait times and numerous barriers to accessing professional mental health services highlight the importance of more accessible and less stigmatised mental health services. As highlighted by the studies included within the present review, peer support can be effective in improving the depressive symptoms, stress and anxiety that young adults can experience. The results of this review suggest that peer support may represent a valuable intervention for improving mental health outcomes among young adults; specifically, among those attending college or university. Based on the results of the present review, it is recommended that future research investigate the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of formalised peer support services on improving the mental well-being of young adults.

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review examining the impact of peer support on the mental health of young adults beyond university students. Strengths of the present review include the rigorous search criteria used to capture over 12,000 articles from multiple databases. Moreover, all articles were screened and extracted by multiple reviewers. However, results of the present review are limited by significant methodological heterogeneity between included studies. For instance, a majority of the included studies used quantitative approaches with different peer support and mental health measurements being used across studies, with other studies using a qualitative approach to measure the benefit of peer support. Moreover, studies investigating the effect of peer support on mental health through the use of statistical approaches are limited in that they do not fully consider individuals, their peculiarities and unique characteristics, emphasizing the importance of qualitative research in this research domain. Another limitation of the statistical findings reported in most included studies is that they do not include confidence intervals for measures of effect size. The absence of such reported findings limits the accuracy of statements regarding effect sizes. Furthermore, peer supporters varied in their background and whether or not they had received peer-support-related training. These variations highlight the need for greater consistency in what comprises peer support within the research literature. Additionally, there was a lack of standardisation in the recruitment procedures for the participants within the included studies. As such, a number of unmeasured confounding variables could have been relevant to the changes in mental health detected within the studies, such as accessing other mental health services or the use of medications for various mental health conditions. Future research using more thorough screening procedures and randomization procedures are recommended to substantiate the results of the available literature. Although 17 studies were examined in this scoping review, only two studies provided longitudinal evidence investigating the direct effect of peer support on mental health outcomes among young adults. Future research should assess the impact of peer support on the mental health of young adults through randomized prospective trials. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the potential long-term effects of peer support on mental health outcomes, as well as the potential benefits of peer supporters themselves having access to relevant services.

Limitations should also be noted specific to the scoping review methodology. First, the risk of bias of the included papers was not assessed. Second, only peer-reviewed journal articles were included within the present review, with it being possible that additional commentaries, essays or programme evaluation reports have been written on this subject area. This was done in order to ensure a minimal level of scientific rigour within the included articles. Third, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to limit the number of included studies, with the current review not investigating the impact of peer support among those under the age of 18 and those over the age of 25. Additional reviews are required to synthesize the results specific to the impact of peer support on the mental health of children and older adults. Fourth, only studies with the specified mental health outcomes were included and other available literature investigating the benefits of peer support at the level of physical health and social/relational well-being were excluded. Although limiting the scope of the review, this was a predetermined decision to increase the specificity of included scientific articles. Finally, although this scoping review determined the breadth and general findings of the available literature on the effects of peer support for the mental health of young adults, literature reviews using data fusion methods (eg, Fisher’s method in meta-analysis) are necessary to draw firm quantitative interpretations of these effects.

In conclusion, this scoping review highlights the potential benefits of peer support in terms of improving the mental health outcomes of young adults. Importantly, in the included studies, peer support was provided by a wide variety of individuals, ranging from friends and significant others to trained peer supporters. This shows that peer support is being used informally in both everyday conversations and in formalized structured settings, pointing to the multitude of existing definitions of this term. From the reviewed studies, peer support has been shown to have largely positive effects on the mental health outcomes of young adults as it relates to depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, psychological distress and self-esteem. In order to bolster the present evidence base, future studies should focus on examining the impact of peer support on the mental health of young adults through prospective randomized studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @RRebinsky, @JasmynC

Contributors: JR: conceptualisation, methodology, literature search, literature screening, writing–original draft, writing-review and editing, supervision, project administration, guarantor. RR: conceptualisation, methodology, literature search, literature screening, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. RS: writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. SK: literature screening, data extraction. AC: literature screening, data extraction. JEAC: literature screening, data extraction, writing-review and editing. AK: literature screening. KW: literature screening. MS: literature screening, data extraction, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Funding: Funding was provided for assistance with the costs of open-access publication by the Mary H Brown Fund offered by McGill University (Award/Grant number is not applicable).

Disclaimer: No funding agencies had input into the content of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Jurewicz I. Mental health in young adults and adolescents - supporting general physicians to provide holistic care. Clin Med 2015;15:151–4. 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung WW, Hudziak JJ. The transitional age brain: "the best of times and the worst of times". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2017;26:157–75. 10.1016/j.chc.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world Health organization's world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry 2007;6:168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedrelli P, Nyer M, Yeung A, et al. College students: mental health problems and treatment considerations. Acad Psychiatry 2015;39:503–11. 10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benton SA, Robertson JM, Tseng W-C, et al. Changes in counseling center client problems across 13 years. Prof Psychol 2003;34:66–72. 10.1037/0735-7028.34.1.66 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallagher R. National survey of counseling center directors 2006. Project Report. The International Association of Counseling Services 2007:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitzrow MA. The mental health needs of today’s college students: challenges and recommendations. J Stud Aff Res 2003;41:167–81. 10.2202/1949-6605.1310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adlaf EM, Gliksman L, Demers A, et al. The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates: findings from the 1998 Canadian campus survey. J Am Coll Health 2001;50:67–72. 10.1080/07448480109596009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:667–72. 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke R, Bewick BM, Barkham M, et al. Measuring, monitoring and managing the psychological well-being of first year university students. Br J Guid Counc 2006;34:505–17. 10.1080/03069880600942624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stallman HM. Psychological distress in university students: a comparison with general population data. Aust Psychol 2010;45:249–57. 10.1080/00050067.2010.482109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2018;127:623–38. 10.1037/abn0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord 2015;173:90–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierceall EA, Keim MC. Stress and coping strategies among community college students. Community Coll J Res Pract 2007;31:703–12. 10.1080/10668920600866579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaez M, Laflamme L. Experienced stress, psychological symptoms, self-rated health and academic achievement: a longitudinal study of Swedish university students. Soc Behav Pers 2008;36:183–96. 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.2.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mental Health Commission of Canada . Making the case for investing in mental health in Canada. London, ON: Mental Health Commission; 2013: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brådvik L. Suicide risk and mental disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2028–32. 10.3390/ijerph15092028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Gollust SE. Help-Seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Med Care 2007;45:594–601. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zivin K, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, et al. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J Affect Disord 2009;117:180–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vidourek RA, King KA, Nabors LA, et al. Students' benefits and barriers to mental health help-seeking. Health Psychol Behav Med 2014;2:1009–22. 10.1080/21642850.2014.963586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czyz EK, Horwitz AG, Eisenberg D, et al. Self-Reported barriers to professional help seeking among college students at elevated risk for suicide. J Am Coll Health 2013;61:398–406. 10.1080/07448481.2013.820731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan ML, Shochet IM, Stallman HM. Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Adv Ment Health 2010;9:73–83. 10.5172/jamh.9.1.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2004;27:392–401. 10.2975/27.2004.392.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segal SP, Gomory T, Silverman CJ. Health status of homeless and marginally housed users of mental health self-help agencies. Health Soc Work 1998;23:45–52. 10.1093/hsw/23.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, et al. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol 1999;6:165–87. 10.1093/clipsy.6.2.165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John NM, Page O, Martin SC, et al. Impact of peer support on student mental wellbeing: a systematic review. MedEdPublish 2018;7:170–82. 10.15694/mep.2018.0000170.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson EL, House AO. Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. BMJ 2002;325:1265–70. 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon P, Draine J. The state of knowledge of the effectiveness of consumer provided services. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2001;25:20–7. 10.1037/h0095054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suresh R, Karkossa Z, Richard J, et al. Program evaluation of a student-led peer support service at a Canadian university. Int J Ment Health Syst 2021;15:1–11. 10.1186/s13033-021-00479-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson BA, Riley JB. Psychosocial impacts on college students providing mental health peer support. J Am Coll Health 2021;69:232–6. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1660351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Repper J, Carter T. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J Ment Health 2011;20:392–411. 10.3109/09638237.2011.583947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tracy K, Wallace SP. Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2016;7:143–54. 10.2147/SAR.S81535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartone PT, Bartone JV, Violanti JM, et al. Peer support services for bereaved survivors: a systematic review. Omega 2019;80:137–66. 10.1177/0030222817728204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali K, Farrer L, Gulliver A, et al. Online Peer-to-Peer support for young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health 2015;2:e19. 10.2196/mental.4418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ansell DI, Insley SE. Youth Peer-to-Peer support: a review of the literature. Youth M.O.V.E. National 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988;52:30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: three validation studies. Am J Community Psychol 1983;11:1–24. 10.1007/BF00898416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 1987;16:427–54. 10.1007/BF02202939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tilden VP, Nelson CA, May BA. The IPR inventory: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res 1990;39:337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cutrona CE. Ratings of social support by adolescents and adult informants: degree of correspondence and prediction of depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57:723–30. 10.1037//0022-3514.57.4.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McBeath M, Drysdale MTB, Bohn N. Work-integrated learning and the importance of peer support and sense of belonging. ET 2018;60:39–53. 10.1108/ET-05-2017-0070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horgan A, McCarthy G, Sweeney J. An evaluation of an online peer support forum for university students with depressive symptoms. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2013;27:84–9. 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong-Carter E, Guassi Moreira JF, Ivory SL, et al. Daily links between helping behaviors and emotional well-being during late adolescence. J Res Adolesc 2020;30:943–55. 10.1111/jora.12572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibbs JJ, Rice E. The social context of depression symptomology in sexual minority male youth: determinants of depression in a sample of Grindr users. J Homosex 2016;63:278–99. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1083773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrom N. An evaluation of a peer support intervention for student mental health. J Ment Health 2018;27:240–6. 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes S, Rondeau M, Shannon S, et al. A holistic self-learning approach for young adult depression and anxiety compared to medication-based treatment-as-usual. Community Ment Health J 2021;57:392–402. 10.1007/s10597-020-00666-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez N, Johnson S, Black N. Does peer mentoring work? Dental students assess its benefits as an adaptive coping strategy. J Dent Educ 2010;74:1197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morelli SA, Lee IA, Arnn ME, et al. Emotional and instrumental support provision interact to predict well-being. Emotion 2015;15:484–93. 10.1037/emo0000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira A, Williams DI. Stress and coping in helpers on a student ‘nightline’ service. Couns Psychol Q 2001;14:43–7. 10.1080/09515070110038019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jibeen T. Perceived social support and mental health problems among Pakistani university students. Community Ment Health J 2016;52:1004–8. 10.1007/s10597-015-9943-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duncan JM, Withers MC, Lucier-Greer M, et al. Research note: social leisure engagement, peer support, and depressive symptomology among emerging adults. Leisure Studies 2018;37:343–51. 10.1080/02614367.2017.1411968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.ST L, Albert AB, Dwelle DG. Parental and peer support as predictors of depression and self-esteem among college students. Journal of College Student Development 2014;55:120–38. 10.1353/csd.2014.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Llamas J, Ramos-Sánchez L. Role of peer support on intragroup marginalization for Latino undergraduates. J Multicult Couns Devel 2013;41:158–68. 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00034.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parra LA, Bell TS, Benibgui M. The buffering effect of peer support on the links between family rejection and psychosocial adjustment in LGB young adults. J Soc Pers Relat 2018;35:854–71. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sprengel AD, Job L. Reducing student anxiety by using clinical peer mentoring with beginning nursing students. Nurse Educ 2004;29:246–50. 10.1097/00006223-200411000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talebi M, Matheson K, Anisman H. The stigma of seeking help for mental health issues: mediating roles of support and coping and the Moderating role of symptom profile. J Appl Soc Psychol 2016;46:470–82. 10.1111/jasp.12376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suresh R, Alam A, Karkossa Z. Using peer support to strengthen mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:1–12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061336supp001.pdf (94.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.