Abstract

SecB, a protein export-specific chaperone, enhances the export of a subset of proteins across cytoplasmic membranes of Escherichia coli. Previous studies showed that the synthesis of SecB is repressed by the presence of glucose in the medium. The derepression of SecB requires the products of both the cya and crp genes, indicating that secB expression is under the control of catabolic repression. In this study, two secB-specific promoters were identified. In addition, 5′ transcription initiation sites from these two promoters were determined by means of secB-lacZ fusions and primer extension. The distal P1 promoter appeared to be independent of carbon sources, whereas the proximal P2 promoter was shown to be subject to control by the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP)-cAMP complexes. Gel-mobility shift studies showed that this regulation results from direct interaction between the secB P2 promoter region and the CRP-cAMP complex. Moreover, the CRP binding site on the secB gene was determined by DNase I footprinting and further substantiated by mutational analysis. The identified secB CRP binding region is centered at the −61.5 region of the secB gene and differed from the putative binding sites predicted by computer analysis.

An Escherichia coli global regulatory protein, cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP), is involved in the regulation of transcription, either positively or negatively, in many genes involved in carbon metabolism (4, 18). CRP, a homodimer, undergoes a conformational change when complexed with its allosteric effector cAMP and binds to a specific sequence located near or within target promoters to regulate transcription (18). The cellular level of cAMP is controlled by carbon sources, in part by the inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity by glucose (36). CRP is present predominantly in the cAMP-complexed, active conformation under non-catabolite-repressed conditions (e.g., growth with glycerol as the carbon source). The level of CRP-cAMP complex is reduced under catabolite-repressed conditions (e.g., growth with glucose), decreasing the activities of CRP-dependent promoters (4, 28).

The CRP binding sites lie at different locations with respect to transcriptional initiation sites of various promoters (44). Simple CRP-dependent promoters in which CRP-cAMP alone is sufficient for activation have been grouped into two classes based on the location of the recognition site for CRP and the corresponding mechanisms for activation (2, 13). For class I CRP-dependent promoters, such as lacZ and malT promoters, the CRP binding site is located upstream of the −35 region (2, 12). For class II CRP-dependent promoters like galP1, the CRP binding site is centered near the −35 region (7). The interaction between CRP and RNA polymerase has been shown to play a critical role in the activation of transcription in CRP-dependent promoters (6, 18).

SecB, an export-specific molecular chaperone in E. coli, promotes protein export across cytoplasmic membranes for a subset of precursor proteins. SecB binds to these precursors, thus keeping them in loosely folded translocation-competent conformations (22, 35, 46). Subsequently, SecB-precursor complexes target the membrane translocase composed of SecYEG and SecDF-YajC complexes via interaction through a soluble and membrane-associated translocation ATPase, SecA protein (5, 10, 16, 35).

Our previous studies showed that the synthesis of SecB is controlled by carbon nutrients, in contrast to those of other Sec proteins, which are growth rate dependent (39). The cellular amount of SecB is reduced in the presence of glucose. CRP-cAMP has also been shown to be involved in SecB synthesis. Exogenous cAMP partially compensates for the repressed level of SecB in the presence of glucose, and the compensatory recovery by the addition of cAMP is lost in cells lacking functional production of CRP from a cya and crp mutant strain. When plasmids carrying the wild-type crp gene were reintroduced into this cya and crp mutant strain, cells were shown to restore the response to the exogenous cAMP. Moreover, deletion studies on the upstream portion of secB suggest that the expression of secB is controlled by more than one promoter (39). In this study, we report the identification of two secB-specific promoters and their corresponding 5′ transcriptional initiation sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype, phenotype, or description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MC4100 | F− ΔlacU169 araD136 relA rpsL150 flbB5301 deoC7 ptsF25 thi | 8 |

| ZK4 | MC4100 recA5 | 14 |

| RH77 | MC4100 Δcya851 Δcrp-zhd732::Tn10 | 25 |

| BL21λ(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB λlscUV5-T7 gene 1 | 42 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pQF50 | Transcriptional fusion vector, Apr | 23 |

| pTS series | secB-lacZ transcriptional fusions | This work |

| pQF52 | Translational fusion vector, Apr | 23 |

| pTQ series | secB-lacZ translational fusions | This work |

| pT7-6 | Vector with T7 RNA polymerase promoter | 43 |

| pHA7E | pBR322 derivative, crp+ Apr | 17 |

| pT7-CRP | pT7-6 with crp gene, Apr | This work |

| pHK205 | pBR322 derivative, secB+ Apr | 20 |

Cell growth, media, and DNA manipulations.

The medium used in this study was the modified minimal medium A (MinA) described by Davis and Mingioli (11) plus CaCl2 (5 μg/ml), FeSO4 · 7H2O (0.25 μg/ml), and thiamine (10 μg/ml). All carbon sources were at 0.5% (wt/vol), and Casamino Acids (Difco) was at 0.1% (wt/vol). Antibiotics were used when required at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml (ampicillin); 10 μg/ml (tetracycline).

In most cases, cells were grown in glycerol minimal medium overnight at 37°C in a rotary shaker water bath and inoculated into the same fresh medium. During the exponential phase of growth, cells were transferred to fresh media containing the indicated carbon sources with or without cAMP, and cell growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

Plasmid DNA digestion, transformation, and other routine DNA manipulations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (37). Plasmid DNA for nucleotide sequencing and PCR template was isolated by using plasmid isolation kits (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.).

Constructions of secB-lacZ transcriptional and translational fusion plasmids.

To construct transcriptional fusions, restriction enzyme-digested fragments from cloned secB gene plasmid in pHK205 (20) were ligated into appropriate multicloning sites of pQF50. For translational fusions, either restriction enzyme-digested fragments or PCR products, with pHK205 as a template with corresponding primers (Table 2), were first cloned into SmaI-digested pUC18. Then, fragments between the XbaI site of pUC18 and the secB internal EcoRV site were inserted into XbaI-SmaI-digested pQF52. All these fusion plasmids were transformed into ZK4, and transformants were selected on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) plates. All fusion plasmids were reisolated, and DNA sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used to construct probes for CRP binding assays

| Primer | Probe(s)a | Relative descriptionb | Sequence of oligonucleotide (5′ to 3′)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | Pr-46, -47, -102, -78, -80 | wt secB TS | (+174) TGGAAAACGTGCGGCGCGTTCGGC |

| 46 | Pr-46 | wt secB upstream CS | (−134) ATGGCAACGCCGCCAAGCGTGAAG |

| 47 | Pr-47 | wt secB upstream CS | (−89) GCACCACGGTTCCCCAGATTTTTATT |

| 56 | Pr-60 | wt secB TS | (+296) ACACAGGAACCCGGGTTCTTCGCCCGGC |

| 60 | Pr-60 | wt secB upstream CS | (−58) ACAGCACATTGGCGGCTGTGATGACTTGTA |

| 78 | Pr-BCRP-M | BCRP mutation CS | (−71) GATCTTTCTTGACGCACGGCGCGTTGGCGGCTG |

| 80 | Pr-BCRP-W | BCRP wt CS | (−76) CTAGAGATTTTTATTGACGCACAGCACAT |

W, wild type; M, mutations; BCRP, secB P2 CRP binding site.

wt, wild type; TS, template strand; CS, coding strand.

Underlines, CRP binding site or part of it. Italicized letters indicate base pair changes to create restriction sites, and bold letters indicate substituted base pairs for CRP site mutations as shown in Fig. 4. Numbers in parentheses indicated the 5′ position of primers relevant to the +1 of the secB transcript.

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase activities were determined in permeabilized cells (29). Cells harboring lacZ fusion plasmids were normally grown in glycerol medium to exponential phase (OD600, ≈1.2) and washed once with MinA medium. Cells were reinoculated into minimal medium with glycerol, glucose, or glucose plus cAMP (10 mM in final) to an OD600 of 0.1. Cells were allowed to grow for 3.5 generations before the β-galactosidase assay. For RH77 cells, cells from overnight culture in the glucose medium with 0.1% Casamino Acids were grown to exponential phase in the presence or absence of cAMP for about 3.5 generations.

RNA preparation and primer extension.

Total RNAs were prepared from ZK4 cells harboring pHK205, pTQ17, or pTQ46. Cells grown in glycerol minimal medium were harvested and transferred to minimal medium with either glycerol or glucose as the carbon source and were grown for 3.5 generations. Total RNAs were extracted by the acidic hot phenol method (33); briefly, cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer containing 0.02 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.2% diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC). An equal volume of phenol equilibrated with 0.02 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 5 min with gentle shaking. The aqueous phase was reextracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (1:1 [vol/vol]) and precipitated with 3 volumes of 100% EtOH (ethanol). The RNA pellet was dissolved in DEPC-treated deionized H2O and treated with 10 U of RNase-free DNase I in the presence of 40 U of RNase inhibitor (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The RNA was precipitated by adding 1/10 of the volume of 3 M sodium acetate and then 2.5 times the volume of 100% EtOH.

Primer extension was carried out by mixing indicated amounts of total RNA and 1 pmol of 32P end-labeled primer in the reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The reaction mixture was heated to 96°C for 5 min, incubated at 60°C for 60 min, slowly cooled to 42°C, and then incubated for 10 min. Reverse transcription was done at 42°C for 45 min by the addition of 200 U of reverse transcriptase (Supercript II; GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) and 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP). Final products were analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea sequencing gel (Sequegel; National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.). Reference sequences were carried out with the same primers used in primer extensions and with DNA from corresponding plasmids as templates (38). Primers with sequences complementary to the coding strand 5′-TCACCACGAGTAATCACCTTCACTTTCG-3′ and 5′-TGGAAAACGTGCGGCGCGTTCGGC-3′ were used in both primer extensions and reference sequencing ladders for P1 and P2, respectively.

Construction of pT7-Crp and CRP protein purification.

To clone the E. coli crp gene behind bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase promoter, the crp gene from pHA7E (1) was excised with BamHI and EcoRI digestions. The 1-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment was inserted in pT7-6 (43) digested with BamHI and EcoRI. The resulting plasmid, pT7-Crp, was transformed into BL21(λDE3), which carries an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T7 RNA polymerase gene.

CRP was overproduced from strain BL21(λDE3)/pT7-CRP induced with IPTG. Cell extracts were prepared, and CRP was purified by cAMP affinity chromatography followed by ion-exchange chromatography under conditions described previously (47). The identity of CRP protein was confirmed by both amino-terminal peptide sequencing and immunoblotting with anti-CRP sera (15). The purity of CRP was judged by analyzing purified fractions on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by Coomassie blue staining, and was estimated to be over 98% homogeneous (data not shown).

Site-directed mutagenesis and secB DNA fragment preparation.

DNA fragments containing various secB upstream regions were amplified by PCR with appropriate oligonucleotides shown in Table 2, with pHK205 as the template. Amplified fragments were subcloned into the SmaI site of pUC18 cloning vector. Site-directed mutagenesis on the secB CRP binding site and putative binding sites was performed by PCR amplification with base pair-substituted primers (shown in Fig. 4A and Table 2). After subcloning into pUC18, the orientation of inserts and sequences of all cloned fragments were verified by DNA sequencing for both coding and template strands (AmpliTaq; Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). DNA fragments were purified from agarose gel after 5′-HindIII and 3′-EcoRI digestions and labeled with [α-32P]dATP and dGTP (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.) by using Klenow enzyme (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

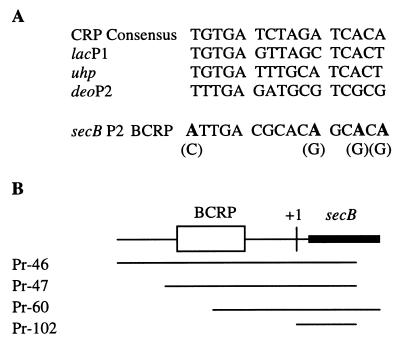

FIG. 4.

CRP binding consensus sequence comparison and DNA fragments for CRP binding assay. (A) Bold face letters indicate base pairs replaced by those in parentheses by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) DNA fragments used in the CRP binding assay and their relative positions with respect to the secB P2 CRP binding site. The probe numbers correspond to the 5′ primers for PCR amplifications, except Pr-102, which has the same 5′ end as that in pTQ102 in Fig. 2. Pr, probe; BCRP, secB P2 CRP binding site.

Gel-mobility shift assay and DNase I footprinting.

DNA fragments employed in these experiments are shown in Fig. 4B. 32P-labeled DNA fragments and purified CRP proteins were incubated in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 50 μM cAMP, 20 μg of salmon sperm DNA [Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.]/ml) for 30 min in a total volume of 20 μl. Then, 3 μl of loading buffer (binding buffer containing 50% glycerol and 0.1 mg of bromophenol blue/ml) was added, and the samples were immediately loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (Protogel; National Diagnostics), with current applied. Then electrophoresis was initiated at a low voltage and progressively increased to 150 V over 60 to 75 min. The electrophoresis buffer contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 1 mM EDTA, and 50 μM cAMP and was replaced with fresh buffer a couple of times during the run.

DNase I footprinting experiments were carried out as previously described (32). Reactions were performed in a total volume of 100 μl of CRP binding buffer as described above with the addition of 2.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2. 32P-labeled DNA fragments (0.1 nM) were incubated with CRP proteins (0 to 6.4 × 10−9 M) in the presence of cAMP for 30 min. Then, pancreatic DNase I (0.2 μg; Boehringer Mannheim) was added, followed by 2 min of digestion. After precipitation with ethanol, the products were analyzed in a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea sequencing gel against a G + A ladder (26).

RESULTS

The expression of the secB gene is controlled by two distantly separated promoters, one of which is subjected to catabolic regulation.

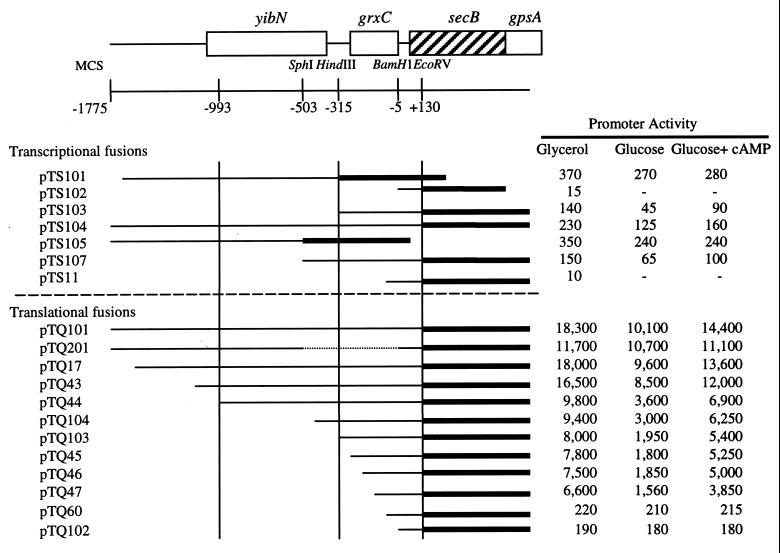

Previous studies on the SecB synthesis suggested that there might be separate promoters for secB expression with different regulatory mechanisms (39). To identify these putative secB promoters, secB-lacZ transcriptional fusions were constructed (Fig. 1). The presence of promoter activity was examined by measuring β-galactosidase activities from cells carrying these fusion plasmids. The responses to either glycerol or glucose as a sole carbon source and the effect of added cAMP were determined (Fig. 1). Two significant promoter activities were observed, one upstream of the HindIII site (at the −315 bp, pTS101), and the other downstream of the HindIII site (pTS103). Cells carrying plasmid pTS101 essentially did not respond to different carbon sources or to the addition of cAMP in the presence of glucose. In contrast, β-galactosidase activities in cells carrying plasmid pTS103 were significantly reduced in the presence of glucose, but not as severely if cAMP was also present. These responses were comparable to those of actual SecB synthesis observed with plasmid pKS101 containing a deletion of the HindIII upstream region (39). Plasmid pTS107, carrying a 5′ end extended by about 200 bp, did not show significant differences from pTS103.

FIG. 1.

Overview of secB and neighboring genes and diagrams of secB-lacZ fusion constructions. Boxes indicate ORFs for yibN, grxC, secB, and gpsA. The yibN product has not yet been identified; grxC has recently been suggested to code for glutaredoxin 3; gpsA encodes sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Solid lines show intergenic regions of these genes. For secB-lacZ fusion constructions, solid lines represent secB upstream regions fused to the corresponding lacZ gene, solid bars represent a promoterless lacZ gene or a promoterless lacZ gene without a ribosome-binding site, and MCS denotes multicloning sites. Promoter activities were determined by measuring β-galactosidase activities for cells carrying corresponding fusion plasmids with different carbon sources and with the addition of exogenous cAMP. During exponential growth in the glycerol medium, cells were transferred into indicated media. The activities of β-galactosidase (expressed in Miller units) were assayed. Data represent the average of three independent experiments, and standard error was typically within ±10%.

To determine whether these two promoters are specific to secB expression, the 5′ end of secB, with progressively smaller segments derived from the 1.8-kb upstream region, was fused to a lacZ gene that lacks both its own promoter and ribosome-binding site for translation (Fig. 1). SecB translational activities were measured as β-galactosidase activities (Fig. 1). β-Galactosidase activities from fusion plasmids, pTQ101, pTQ17, and pTQ43, were high in glycerol and repressed in glucose. However, there were significant decreases in overall activities when fusion fragments were shortened further. In addition, glucose repression became more prominent as seen in pTQ44 through pTQ47. From these data, we conclude that the expression of secB is controlled by two spatially separated promoters. The distal promoter, P1, resides within the fragment between pTQ43 and pTQ44 fusions, and the proximal promoter, P2, resides within a pTQ47 fragment. The P2 promoter likely accounts for the repression by glucose, since the internal deletion of the SphI-BamHI fragment from pTQ17 (pTQ201, Fig. 1) resulted in a complete loss of the ability to respond to different carbon sources. On the other hand, pTQ201 was expressed in a constitutive manner under the conditions tested.

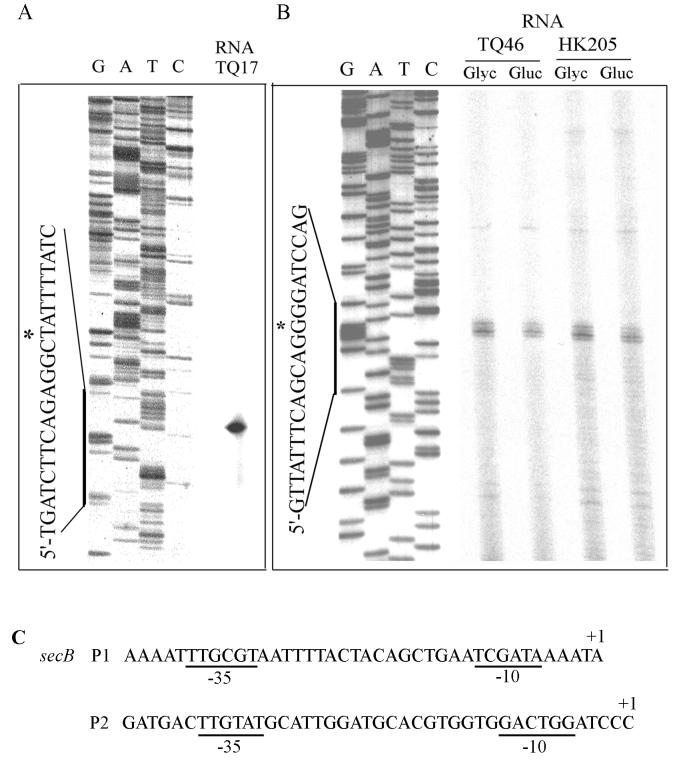

Determination of 5′ ends of secB transcripts from the P1 and P2 promoters.

The transcriptional initiation sites were determined by primer extension assays (Fig. 2). Total mRNAs were prepared from cells harboring the plasmid-encoded secB gene, pHK205 (21) or secB-lacZ fusion plasmids, pTQ46 or pTQ17, grown in glycerol or glucose minimal media. The 5′ end of the secB transcript from the proximal promoter P2 was located 75 bp upstream of the initiation codon of SecB and subsequently designated +1 (Fig. 2B). Upon quantitation of primer extension products with mRNAs from glycerol- or glucose-grown cells, P2 transcripts were consistent with β-galactosidase activities of pTQ46 measured at the time of total RNA preparations (data not shown). The 5′ end of distal promoter P1 transcript was also determined by a separate primer extension experiment with mRNA extracted from plasmid pTQ17 and located at position −988 with respect to the newly identified +1 of P2 transcript (Fig. 2A). Both promoter sequences are shown in Fig. 2C. These 5′ transcriptional initiation sites were in agreement with previous fusion studies (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Primer extension for the identification of 5′ ends of transcripts from the secB P1 and P2 promoters. Total RNAs were prepared from ZK4 harboring plasmid pTQ17 grown in glycerol or plasmid pTQ46 or pHK205 grown in glycerol or glucose media as indicated. Primers complementary to coding strand were extended at 42°C for 45 min with reverse transcriptase. Reference DNA sequencing was done with the same primers as those in primer extensions. (A) P1 promoter. (B) P2 promoter. Total RNA (2.5 and 5 μg, respectively) was used for panels A and B, respectively. Asterisks indicate 5′ positions from each respective promoter. (C) Sequences of the secB P1 and P2 promoters.

Characterization of the roles of CRP-cAMP in the secB expression: direct interaction between the secB and the CRP-cAMP complex.

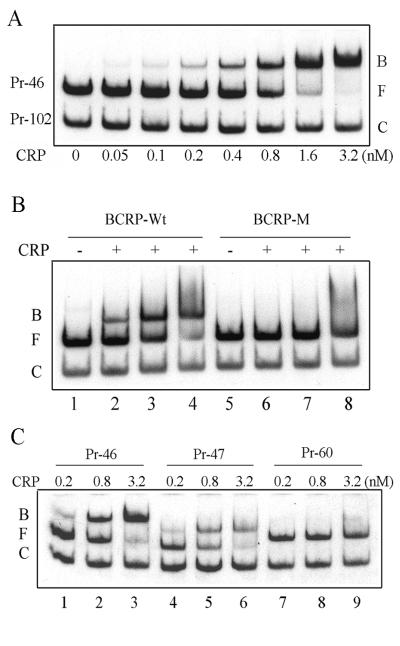

The addition of cAMP in the glucose medium resulted in increased transcriptional activation at the secB P2 promoter (Fig. 1). This recovery from catabolic repression requires the presence of the crp gene (39). These results suggest the involvement of the CRP-cAMP complex on the expression of secB. The possible interaction between the CRP-cAMP complex and the secB P2 promoter regulatory region was examined directly, by measuring the binding activity of purified CRP protein on the DNA fragment containing the secB P2 promoter. Preliminary results showed that CRP effectively bound to the secB P2 promoter region in the gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay (data not shown; see Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

CRP titration and mutational analysis on secB CRP binding sites. CRP binding affinities were determined with various secB DNA fragment probes carrying mutations on the CRP binding site as described in the legend for Fig. 4. (A) Binding of CRP protein on the secB gene. Gel-mobility shift assays were carried out with secB P2 containing DNA fragments and purified CRP. 32P end-labeled secB DNA probes were incubated with increasing amounts of purified Crp protein in the presence of 50 μM cAMP. DNA-protein complexes were analyzed in 5% native PAGE. (B) Site-directed mutagenesis on the BCRP site (secB P2 CRP). CRP proteins are 0, 0.2, 0.8, and 3.2 × 10−9 M in lanes 1 and 5, 2 and 6, 3 and 7, and 4 and 8, respectively. (C) Deletion and truncation on the BCRP site (secB P2 CRP). Abbreviations: B, bound-DNA probe; F, free-DNA probe; and C, unbound negative control DNA probe.

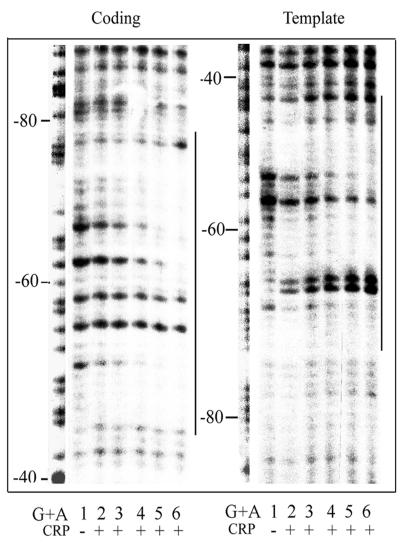

To determine the CRP binding site, DNase I footprinting experiments were performed. A labeled 170-bp DNA fragment containing secB regulatory regions was incubated with increasing concentrations of CRP in the presence of cAMP and then treated with DNase I. The products were analyzed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 3). CRP bound and protected the DNA region between −75 and −49 bp from DNase I cleavage. The protected region was centered −61.5 bp from the P2 promoter. Several sites in both coding and template strands showed enhanced cleavages.

FIG. 3.

CRP binding site for the secB P2 promoter. DNase I footprinting experiments with DNA fragment containing the secB promoter regions were carried out with purified Crp proteins. Final Crp protein concentrations are 0, 0.2 × 10−9, 0.4 × 10−9, 0.8 × 10−9, 1.6 × 10−9, and 6.4 × 10−9 M in lanes 1 to 6, respectively. Vertical dark bars indicate protected binding regions by Crp proteins, and numbers are in respect to the +1 transcriptional initiation site from the P2 promoter.

A CRP titration experiment was performed by gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay. A 314-bp DNA fragment, probe 46 (Pr-46), corresponding to the same upstream sequences as those in pTQ46 was used (Fig. 1). The affinity of CRP for the secB gene, expressed as the apparent Kd value, was estimated to be about 0.8 × 10−9 M, where the ratio of free DNA and bound DNA is 1 (Fig. 5A). Only a single shifted band of the same mobility was observed within the CRP concentrations ranging from 5 × 10−11 M to 6.4 × 10−9 M. Sequence-specific CRP binding for secB upstream regions was shown by incubating Pr-46 in the presence of nonreactive control probe 102 (Fig. 4B, Pr-102), from which the 5′ regulatory regions were removed from Pr-46 to +1 position, while the same 3′ end was retained. No shifted band was observed over the same CRP concentrations tested (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the absence of cAMP in the assay abolished the binding activity of CRP (data not shown).

The effect of the binding site truncation and mutations on CRP binding and secB P2 promoter activity.

The identified CRP binding site of the secB P2 promoter (hereafter designated BCRP) was somewhat surprising in that it is not very similar to previously known CRP binding sites (Fig. 4A) (12, 34). In addition, initial searches with Nucleotide Subsequence Search, MacVector, version 6.0 (Oxford Molecular, Campbell, Calif.), revealed two other potential candidates for CRP binding sites, one located at the −119-bp region and the other at the −44-bp region of the secB gene (respective to transcriptional start site +1). To further substantiate the actual BCRP site, deletions and site-directed mutations (Fig. 4A and B) were introduced and compared for CRP binding activities. A site-directed point mutation with a 4-bp substitution in the BCRP site (Fig. 4A) almost completely abolished the CRP binding affinity (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 to 8; Pr-BCRP-M) compared to that without mutations (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 4; Pr-BCRP-W). In addition, deletion upstream of BCRP, as in probe Pr-47, showed the same affinity for CRP (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 to 6; Pr-47) as in Pr-46 (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 to 3). However, when the left half of BCRP binding sequences was truncated (probe Pr-60), the ability of this fragment to bind CRP was almost completely abolished (Fig. 5C, lanes 7 to 9). Moreover, mutations at the −44-bp consensus sequence, TGTGA, did not have any effect on CRP binding (data not shown), and this site is not involved in CRP binding, even when the real BCRP site is altered or deleted (Fig. 5B and C). These data provide further evidence that the BCRP site is, indeed, the real CRP binding site for the secB gene, as shown by DNase I footprinting.

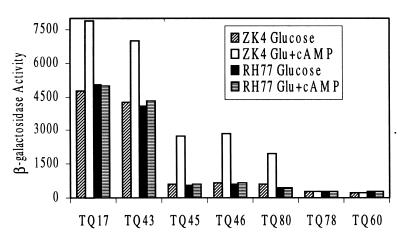

The effects of CRP binding site mutations on the expression of secB were further examined in vivo by secB-lacZ fusions in conjunction with cya and crp mutations. secB-lacZ fusions with mutations on the CRP binding site were constructed from the DNA fragments used in gel-mobility shift assay (Fig. 6). Translational activities of secB promoters were compared with or without the addition of cAMP in both wild-type and cya and crp mutant backgrounds (Fig. 6). As expected, fusion plasmids carrying both the P1 and the P2 promoters, pTQ17 and pTQ43, showed moderate responses to the addition of cAMP (less than a twofold increase), while plasmids with P2 promoter only (pTQ45, pTQ46, and pTQ80) had a more pronounced increase by the addition of cAMP (about three- to fourfold). Fusion plasmids carrying either deletion or mutations on the CRP binding site lost almost all promoter activity (pTQ60 and pTQ78) and showed little response to the cAMP. When examined in cya and crp mutant background (RH77), all these plasmids lost their ability to respond to the exogenously added cAMP.

FIG. 6.

The effect of CRP binding site mutations on secB promoter activity. Promoter activities and their responses to cAMP were determined from wild-type ZK4 cells as well as in cya and crp mutant background RH77 cells carrying secB-lacZ fusion plasmids with mutations on the CRP binding site. Fusion plasmids pTQ60, pTQ78, and pTQ80 were constructed by subcloning of DNA probes used in the experiments shown in Fig. 5B and C into translational fusion vector pQF52 as described in Materials and Methods. All other fusion plasmids were described in the legend for Fig. 1. Cells carrying indicated fusion plasmids were grown overnight in minimal medium containing 0.5% glucose and 0.1% Casamino Acids and were transferred to the same fresh media by dilutions with or without cAMP. Activities were expressed in Miller units, and averages of two independent cultures and standard error were within ±10%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, two spatially separated promoters for secB were identified by primer extension as well as by transcriptional and translational fusions. These results were in agreement with suggestions from previous physiological studies (39) as well as with E. coli genomic DNA sequence analysis (39, 41). Although these two promoters are separated by almost 1 kb, both lead to specific secB expression as determined by translational fusions (Fig. 1). The removal of the distal P1 promoter from fusion constructs results in a reduction of about twofold in overall secB-β-galactosidase expression, in agreement with the previous deletion analysis (39). Only the proximal P2 promoter is under the control of different carbon sources, while the distal P1 promoter appears to mediate expression in a constitutive manner under the conditions tested. Furthermore, glucose repression at the P2 promoter is shown to be regulated at the transcriptional level as evidenced by both secB-lacZ fusions and primer extension analysis (Fig. 1 and 2). Regulation at the transcriptional level was further substantiated by the finding that the stability of the SecB protein was unchanged in media containing different carbon sources (data not shown).

The catabolic repression at the secB P2 promoter involves the CRP-cAMP complex, since the addition of cAMP partially relieves glucose repression, and this compensatory recovery requires the presence of the crp gene (39). Gel-mobility shift assays with a DNA fragment containing the secB P2 promoter region and purified CRP protein clearly demonstrate that the effect of CRP-cAMP on secB expression results from a direct interaction between CRP and secB (Fig. 3). It also appears that there is only a single binding site for CRP on secB, since a single shifted band was observed over the range of CRP concentrations tested. The finding that the CRP binding site to the secB P2 promoter is centered at about −61.5 bp upstream of the +1 transcriptional initiation site indicates that it may be a class I CRP-dependent promoter like the lacP1 promoter (12). The estimated CRP binding affinity of secB P2 (0.8 × 10−9 M) is also comparable to that of lacP1 (0.328 × 10−9 M [45]), even though the secB site deviated more than lacP1 from the well-defined consensus sequences of CRP binding sites (Fig. 4A). Mutational analyses substantiate the finding that the site newly identified by DNase I footprinting is the real CRP binding site. Moreover, the consensus sequence (TGTGA) near −44 bp does not contribute or function, even in the absence of the real CRP binding sequences.

Two open reading frames (ORFs) upstream of secB also appear to be under the control of the distal P1 promoter. The distal putative ORF to secB is designated yibN, and the proximal ORF has recently been identified as a homologue to grxC, a minor glutaredoxin 3 (3). No other significant promoter activities have been identified for these ORFs, and SecB was expressed from the P1 promoter as efficiently as from the P2 promoter despite the distance between secB and the P1 promoter (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is likely that these four genes, i.e., the two upstream ORFs’ genes, secB, and gpsA, form an operon from the P1 promoter whose regulation differs from that of P2. In contrast, the expression from P2 covers only secB and downstream gpsA with carbon source-dependent expression. The physiological and functional relationships among these genes are unclear.

Since the only known physiological function of the SecB protein is as a molecular chaperone in protein export, it was previously assumed that the production of SecB may depend on growth rates of cells to support the increased need for protein translocation in faster-growing cells. Nonviability of secB null strains on Luria-Bertani plates and their viability on the glycerol minimal plate may also be partially explained by growth rate-dependent needs of the SecB protein (20). However, our previous studies showed that SecB synthesis is not related to the growth rates of cells (39). Moreover, Shimizu et al. (40) found that the nonviability of secB null strains on Luria-Bertani plates is due to the insufficient expression of the gpsA gene that is located immediately downstream from secB and encodes biosynthetic sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. In addition, the gpsA gene is translationally coupled to secB, as the start codon of GpsA overlaps with the stop codon of SecB (41), a finding we have confirmed. The secB P2 promoter region is required for the efficient expression of the gpsA gene (40). We conclude that the expression of secB does not depend on the growth rate of cells; rather, it is related to carbon sources in the media by means of catabolic repression mediated by the CRP-dependent P2 promoter.

The unique regulation of secB expression may be related to the fact that SecB is involved in the export of only a subset of precursor proteins. Thus, the export defect of OmpA caused by SecB deficiency is not as severe as other SecB-dependent precursors such as MBP (maltose binding protein) and LamB (20, 27). The expression of MBP and LamB is also activated by the CRP-cAMP complex (31), whereas the expression of OmpA is constitutive and thus affected little by CRP (30). Since SecB is present in relatively low amounts compared to SecB-dependent precursors (typically 100- to 400-fold in excess of SecB [39]) and SecB binds transiently to these precursors (19), small variations in SecB quantities (twofold overall) may be sufficient to modulate relatively large variations in precursors. Thus, it is possible that CRP-cAMP-activated expression of SecB from the proximal promoter P2 is designed to serve for similarly activated expression of precursors such as pLamB and pMBP. Another scenario, however, is also possible. Precursors of exported proteins are synthesized mainly from membrane-bound polysomes in fast-growing cells. They are synthesized equally from free polysomes and membrane-bound polysomes in slower-growing cells (9). Thus, in faster-growing cells in the presence of glucose, there may be less need for a chaperone for export. Accordingly, the requirement for and the production of SecB are less. Alternatively, other chaperones, such as trigger factor and GroEL (24), can function under these conditions in place of SecB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Richard Ebright for providing the CRP purification protocol, Hiroji Aiba for Crp antisera, and Carol Kumamoto, Jon Beckwith, Ann Hochschild, and Regine Hengge-Aronis for plasmids and E. coli strains. We thank Ping Jiang and Tim Brown of the Biotechnology Core Facility at Georgia State University for the preparation of oligonucleotide primers and for DNA sequencing and peptide sequencing. We also thank John E. Houghton and Chung-Dar Lu for discussions and help throughout this study and Chris Bates and Wendy Kellner for editorial assistance.

This work is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM 34766) and equipment grants from Georgia Research Alliance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba H, Fujimoto S, Ozaki N. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the gene for E. coli cAMP receptor protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:1345–1361. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.4.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba H, Hanamura A, Tobe T. Semisynthetic promoters activated by cyclic AMP receptor protein of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1989;85:91–97. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aslund F, Ehn B, Miranda-Vizuete A, Pueyo C, Holmgren A. Two additional glutaredoxins exist in Escherichia coli: glutaredoxin 3 is a hydrogen donor for ribonucleotide reductase in a thioredoxin/glutaredoxin 1 double mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9813–9817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botsford J L, Harman J G. Cyclic AMP in prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:100–122. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.100-122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breukink E, Nouwen N, van Raalte A, Mizushima S, Tommassen J, de Kruijff B. The C terminus of SecA is involved in both lipid binding and SecB binding. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7902–7907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busby S, Ebright R H. Promoter structure, promoter recognition, and transcription activation in prokaryotes. Cell. 1994;79:743–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busby S, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casadaban M J. Regulation of the regulatory gene for the arabinose pathway, araC. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:557–566. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Rhoads D, Tai P C. Alkaline phosphatase and OmpA protein can be translocated posttranslationally into membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:973–980. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.973-980.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Xu H, Tai P C. A significant fraction of functional SecA is permanently embedded in the membrane. SecA cycling on and off the membrane is not essential during protein translocation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29698–29706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis B D, Mingioli E S. Mutants of Escherichia coli requiring methionine or vitamin B12. J Bacteriol. 1950;60:17–28. doi: 10.1128/jb.60.1.17-28.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebright R H. Transcription activation at Class I CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebright R H, Ebright Y W, Gunasekera A. Consensus DNA site for the Escherichia coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP): CAP exhibits a 450-fold higher affinity for the consensus DNA site than for the E. coli lac DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:10295–10305. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilson L, Mahanty H K, Kolter R. Genetic analysis of an MDR-like export system: the secretion of colicin V. EMBO J. 1990;9:3875–3894. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogema B M, Arents J C, Inada T, Aiba H, van Dam K, Postma P W. Catabolite repression by glucose 6-phosphate, gluconate and lactose in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:857–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3991761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito K. The major pathways of protein translocation across membranes. Genes Cells. 1996;1:337–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.34034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joung J K, Chung E H, King G, Yu C, Hirsh A S, Hochschild A. Genetic strategy for analyzing specificity of dimer formation: Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein mutant altered in its dimerization specificity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2986–2996. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolb A, Igarashi K, Ishihama A, Lavigne M, Buckle M, Buc H. E. coli RNA polymerase, deleted in the C-terminal part of its alpha-subunit, interacts differently with the cAMP-CRP complex at the lacP1 and at the galP1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:319–326. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumamoto C A. Escherichia coli SecB protein associates with exported protein precursors in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5320–5324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumamoto C A, Beckwith J. Evidence for specificity at an early step in protein export in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:267–274. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.267-274.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumamoto C A, Beckwith J. Mutations in a new gene, secB, cause defective protein localization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:253–260. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.253-260.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumamoto C A, Chen L, Fandl J, Tai P C. Purification of the Escherichia coli secB gene product and demonstration of its activity in an in vitro protein translocation system. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2242–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon D H, Lu C D, Walthall D A, Brown T M, Houghton J E, Abdelal A T. Structure and regulation of the carAB operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas stutzeri: no untranslated region exists. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2532–2542. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2532-2542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lecker S, Lill R, Ziegelhoffer T, Georgopoulos C, Bassford P J, Jr, Kumamoto C A, Wickner W. Three pure chaperone proteins of Escherichia coli—SecB, trigger factor and GroEL—form soluble complexes with precursor proteins in vitro. EMBO J. 1989;8:2703–2709. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marschall C, Hengge-Aronis R. Regulatory characteristics and promoter analysis of csiE, a stationary phase-inducible gene under the control of sigma S and the cAMP-CRP complex in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McFarland L, Francetic O, Kumamoto C A. A mutation of Escherichia coli SecA protein that partially compensates for the absence of SecB. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2255–2262. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2255-2262.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkel T J, Dahl J L, Ebright R H, Kadner R J. Transcription activation at the Escherichia coli uhpT promoter by the catabolite gene activator protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1712–1718. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1712-1718.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Movva R N, Green P, Nakamura K, Inouye M. Interaction of cAMP receptor protein with the ompA gene, a gene for a major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1981;128:186–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Notley L, Ferenci T. Differential expression of mal genes under cAMP and endogenous inducer control in nutrient-stressed Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S M, Lu C D, Abdelal A T. Cloning and characterization of argR, a gene that participates in regulation of arginine biosynthesis and catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5300–5308. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5300-5308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S M, Lu C D, Abdelal A T. Purification and characterization of an arginine regulatory protein, ArgR, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its interactions with the control regions for the car, argF, and aru operons. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5309–5317. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5309-5317.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perini L T, Doherty E A, Werner E, Senear D F. Multiple specific CytR binding sites at the Escherichia coli deoP2 promoter mediate both cooperative and competitive interactions between CytR and cAMP receptor protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33242–33255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier M H., Jr Protein phosphorylation and allosteric control of inducer exclusion and catabolite repression by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:109–120. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.109-120.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seoh H K, Tai P C. Carbon source-dependent synthesis of SecB, a cytosolic chaperone involved in protein translocation across Escherichia coli membranes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1077–1081. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1077-1081.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu H, Nishiyama K, Tokuda H. Expression of gpsA encoding biosynthetic sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase suppresses both the LB-phenotype of a secB null mutant and the cold-sensitive phenotype of a secG null mutant. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1013–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6392003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sofia H J, Burland V, Daniels D L, Plunkett III G, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome. V. DNA sequence of the region from 76.0 to 81.5 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studier F W, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tagami H, Aiba H. A common role of CRP in transcription activation: CRP acts transiently to stimulate events leading to open complex formation at a diverse set of promoters. EMBO J. 1998;17:1759–1767. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vossen K M, Stickle D F, Fried M G. The mechanism of CAP-lac repressor binding cooperativity at the E. coli lactose promoter. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:44–54. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiss J B, Ray P H, Bassford P J., Jr Purified SecB protein of Escherichia coli retards folding and promotes membrane translocation of the maltose-binding protein in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8978–8982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X P, Gunasekera A, Ebright Y W, Ebright R H. Derivatives of CAP having no solvent-accessible cysteine residues, or having a unique solvent-accessible cysteine residue at amino acid 2 of the helix-turn-helix motif. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1991;9:463–473. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1991.10507929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]