Abstract

Purpose:

Currently, there are an estimated 4.95 million blind persons and 70 million vision impaired persons in India, out of which 0.24 million are blind children. Early detection and treatment of the leading causes of blindness such as cataract are important in reducing the prevalence of blindness and vision impairment. There are significant developments in the field of blindness prevention, management, and control since the “Vision 2020: The right to sight” initiative. Very few studies have analyzed the cost of blindness at the population level. This study was undertaken to update the information on the economic burden of blindness and visual impairment in India based on the prevalence of blindness in India. We used secondary and publicly available data and a few assumptions for our estimations.

Methods:

We used gross national income (GNI), disability weights, and loss of productivity metrics to calculate the economic burden of blindness and vision impairment based on the “cost of illness” methodology.

Results:

The estimated net loss of GNI due to blindness in India is INR 845 billion (Int$ 38.4 billion), with a per capita loss of GNI per blind person of INR 170,624 (Int$ 7,756). The cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable blindness in India is INR 11,778.6 billion (Int$ 535 billion). The cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness increased almost three times in the past two decades. The potential loss of productivity due to vision impairment is INR 646 billion (Int$ 29.4 billion).

Conclusion:

These estimates provide adequate information for budgetary allocation and will help advocate the need for accelerated adoption of all four strategies of integrated people-centered eye care (IPCEC). Early detection and treatment of blindness, especially among children, is very important in reducing the economic burden; thus, there is a need for integrating primary eye care horizontally with all levels of primary healthcare.

Keywords: Burden of blindness, cost of illness, health economics

There are an estimated 4.95 million people blind (0.36% of the total population), 35 million people visually impaired (2.55%), and 0.24 million blind children in India.[1] Cataract and refractive error remain the leading causes of blindness and visual impairment, respectively, in India.[1,2,3,4] There have been significant developments in the field of blindness prevention, management, and control since the “Vision 2020: The right to sight” initiative[5] has been implemented over the last two decades. A recent study estimated the cost of blindness in terms of gross national income (GNI) per capita but on those aged above 50 years of age.[6] With many interventions in place for more than two decades now,[7] this study is undertaken to update the information on the economic burden of blindness and visual impairment in India based on the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment, GNI, and potential loss of productivity. This information at the national level has its utility in policy formulation and planning service delivery, including programmatic level budgetary provisions and allocations.

Methods

The methodology used is the “cost of illness” estimation.[6,8] We used secondary data and publicly available data in this study.

Demographic and prevalence of blindness and vision impairment data

We obtained demographic information such as the total population[9,10] and the total number of blind and vision-impaired people in India.[11] Data on the prevalence of blindness and vision impairment for the overall population and in children were obtained from the published literature.[1,2,12] Blindness is defined as “presenting visual acuity worse than 3/60 in the better eye”[1] in this study to compare the estimates previously estimated in 1998.[13]

Data for estimation of the economic burden of blindness and vision impairment in India

The economic burden of all blindness and vision impairment is expressed by considering the direct and indirect loss of GNI due to blindness and vision impairment and the economic productivity of the blind and visually impaired. We assumed that both GNI and gross national product are similar as this helps in comparison of the economic burden of blindness estimated in different time periods.[14] The economic burden of blindness was then estimated using multiple assumptions.

These are the data and assumptions for the estimations:

The total population of India as per current estimates is 1.38 billion[9,10] estimated at an annual growth rate (AGR) of 1.29% for the year 2020. There are 399 million children (29% of the population).[11] Population indicators range over a period from 2016 to 2020.

We included all four levels of distance vision impairment as defined by WHO in the study.[15] Blindness is defined as presenting visual acuity worse than 3/60 in the better eye. Mild vision impairment is defined as presenting visual acuity worse than 6/12 to 6/18 in the better eye, moderate vision impairment is defined as presenting visual acuity worse than 6/18 to 6/60 in the better eye, and severe vision impairment is defined as presenting visual acuity worse than 6/60 to 3/60 in the better eye.[1,15]

The estimated prevalence of blindness is 0.36% of the population (4.95 million).[1]

The estimated prevalence of mild, moderate, and severe vision impairment is 2.92% (40 million), 1.84% (25 million), and 0.35% (4.8 million) of the population, respectively.[1]

Per capita gross national income (GNI) is INR 139,867 (Int$ 6,357).[16]

51.5% of the population contributes to the labor force.[16,17] We assumed that 60% of blind adults contribute to the labor force.[13]

The average age of children is considered as 8 years.[13] The average lifespan for blind children is assumed to be between 40 and 55 years.

Primarily, the average number of working years considered lost due to blindness in children is estimated for 35 and 40 years due to the better survival rate of infants and the increase in life expectancy. All children are assumed to be economically productive after they attain 15 years of age.[13]

We assumed that the productive time lost by caregivers is 10% taking care of blind adults[13] and 5% taking care of visually impaired persons. We assumed that caregivers lose 20% of the productive time taking care of blind children as more effort is needed.

To calculate the cumulative loss of GNI, we assumed that 20% of the blind persons are economically productive at 25% of the actual productive workforce.[13]

To calculate the GNI loss due to vision impairment, we used disability weights for vision impairment published by WHO.[18] Disability weights for vision impairment are used as substitutes for the relative reduction in employment due to vision impairment by assuming a direct relationship between productivity and disability weights.[19,20]

Between 30% and 40% of blindness in children is due to avoidable (easily preventable and treatable) causes.[4] We assumed that 35% of blindness in children is avoidable.

82.3% of blindness among adults and 35% of blindness among children is due to avoidable causes.[2,21,22]

The formulas used for calculating the indicators used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Formulas and calculations of indicators

| Indicator | Calculation |

|---|---|

| Per capita GNI | INR 192,394 billion/1.38 billion=INR 139,867 |

| Per capita GNI produced by the labor force | Per capita GNI/% of labor force=INR 139,867/0.515=INR 271,587 |

| Direct loss of GNI due to blindness | All GNI is assumed to be due to labor force of 51.5%. Assuming that 60% of blind adults are in the age group of the labor force, Direct loss of GNI=Number of blind adults×60% × INR 271,587. To calculate the cumulative loss of GNI, we assume that there is a direct loss of GNI as children start contributing to the economy at 15 years of age with an annual economic growth rate of 5% (total blind children×per capita GNI produced by labor force at 5% growth rate for 35 years and 40 years) |

| Indirect loss of GNI due to blindness | Number of blind persons × 0.1 (10%) × per capita GNI by labor force. For cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness in children, we have assumed that the caregiver spends 20% of the time taking care of blind children |

| Economic productivity of blind | Assuming that 20% of blind adults are economically productive at 25% of the productivity level of a member of the labor force |

| Net loss of GNI due to blindness* | Direct cost + indirect cost−economic productivity |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness over the lifespan of the blind adults | Sum of net loss of GNI for 8 years and 10 years respectively at an annual growth rate (GR) of 5% |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness over the lifespan of the blind children | Sum of Net loss of GNI for 35 years and 40 years respectively with an annual growth rate (GR) of 5%; assuming all children contribute to labor force and caregivers spend 20% of the time taking care of the blind child |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable blindness | Cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness over the lifespan of blind adults × 82.3% (calculated for 8 years and 10 years) |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness over the lifespan of blind children × 35% (calculated for 35 and 40 years, respectively) | |

| Potential loss of productivity due to vision impairment (for each level of vision impairment) | No. of vision impaired people×60% × INR 271,587×0.005 or 0.089 or 0.314 |

| Disability weights for mild, moderate, and severe vision impairment.[23] | |

| All the calculations are converted to international dollars (Int$) purchasing power parity (PPP) | Int$ 1=INR 22 in the year 2020.[24,25] |

| Int$ 1=INR 9.75 in the year 1997.[24,25] | |

| All the calculations done in 1997-98 are converted to current inflation rates and compared with 2020 data. | 1 USD in 1997–98 is equal to 1.6 USD in 2020.[26] Considered 2020 as the base year for our calculations. |

*For children, this is the indirect cost

In this estimation, the calculation is done based on the burden of blindness and vision impairment in economic terms and its loss of productivity. To compare data between 1997 and 2020, we used 2020 as the base year and converted the 1997 data into Int$ Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) for the year 1997 and then used the US inflation rate to adjust the Int$ to the base year.[26,27]

Ethical clearance

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of the University of Hyderabad. Approval number: UH/IEC/2020/222.

Results

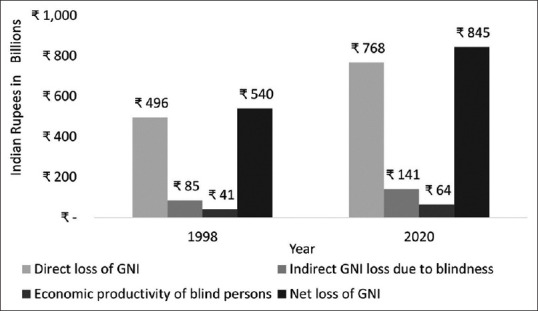

Economic burden of blindness in India estimated in the year 2020

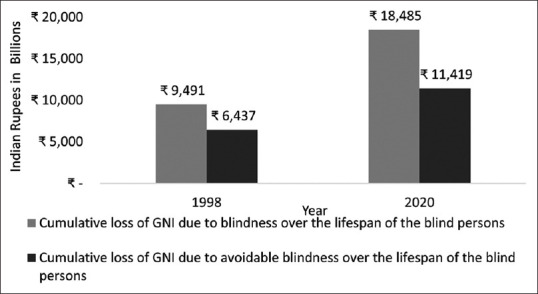

Based on the assumptions, the net loss of GNI due to blindness in India is INR 845 billion (Int$ 38.4 billion). Per capita net loss of GNI per blind person is INR 170,624 (Int$ 7,756). Net loss of GNI due to blindness in adults and children is INR 832 billion and INR 13 billion respectively. The direct and indirect loss of GNI due to blindness in adults is INR 768 billion (Int$ 35 billion) and INR 128 billion (Int$ 5.8 billion) respectively. The indirect loss of GNI due to blindness in children is to the tune of INR 13 billion (Int$ 590 million). The economic productivity of blind adults is estimated as INR 64 billion (Int$ 2.9 billion). The total cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness (considering a loss of 10 and 35 working years for blind adults and children, respectively) is INR 19,512 billion (Int$ 887 billion). The cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable blindness (considering a loss of 10 and 35 working years for blind adults and children, respectively) is INR 11,778.6 billion (Int$ 535.4 billion).

Estimates and comparison of the economic burden of blindness in 2020 and 1997–98 are presented in Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Results of the economic burden of blindness in India – 2020

| Indicator | Total |

|---|---|

| Number of blind people (millions) (*) | 4.95 |

| Loss of GNI due to blindness (INR: billions) | |

| Direct (†) | 768 |

| Indirect (‡) | 141 |

| Economic productivity of blind persons (INR: billions) (§) | 64 |

| Net loss of GNI due to blindness (INR: billions) (||) | 845 |

| Average number of working years lost due to blindness (¶) | 10 & 40 |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness over the lifespan of the blind (GR=5%) (INR: billion) (**) | 22,565 |

| Cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable blindness (GR=5%) (INR: billions) (††) | 12,847 |

* Estimated prevalence of blindness is 0.36% of the population (4.95 million).[1]. †Direct loss of GNI=number of adult blind persons×0.6×INR 271,587. ‡ Indirect loss of GNI due to blindness in adults=number of adult blind persons×0.1×INR 271,587. Indirect loss of GNI due to blindness in children=number of blind children×0.2×INR 271,587. §Economic productivity=0.2×0.25×INR 271,587. ||Net loss of GNI=direct cost+indirect cost−economic productivity. ¶Average number of working years lost in adults and children due to blindness are 10 and 40 years, respectively, ** Sum of the cumulative loss of GNI for all the working years for the lifetime of the bind at 5% annual growth rate. (Cumulative loss of net GNI in adults for the loss of 10 working years + cumulative loss of net GNI in children for the loss of 40 working years from the age of 15 years for children assuming caregiver spends 20% of the time taking care of blind children). ††82.3% of blindness among adults and 35% of blindness amongst children is due to avoidable causes[2,21,22] Cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable causes of blindness for the lifetime of blind=82.3% × cumulative loss of GNI over the lifespan of blind adults +35% × cumulative loss of GNI over the lifespan of blind children

Figure 1.

Comparison of the economic burden of blindness estimated in 1998 and 2020

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cumulative loss of GNI due to blindness estimated in 1998* and 2020 (GR = 5%). *To compare, we estimated the 1997–98 data based on 20% productivity time lost for caregivers as the original data published has considered 10% productivity time lost for caregivers

Potential loss of productivity due to vision impairment in India estimated in the year 2020

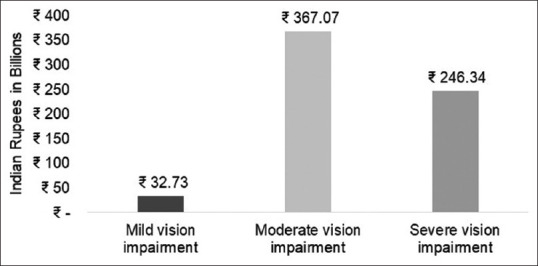

Based on the assumptions, the economic potential total loss of productivity due to vision impairment in India is INR 646 billion (Int$ 29 billion). The per capita loss of productivity due to vision impairment in India is INR 9,192 (Int$ 418). The loss of productivity due to mild, moderate, and severe vision impairment is presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Potential loss of productivity due to various levels of vision impairment

Discussion

Reduction in blindness and vision impairment and the economic impact in India

There is a substantial reduction in the prevalence of blindness in India compared with 1997–98 from 1% to 0.36% in 2020 by using the same definition of blindness. There is a nearly 50% reduction in vision impairment in 2020 from 2010 estimates.[1] This indicates that there have been sustained efforts toward the reduction of the prevalence of blindness in India in the last 22 years by various organizations and institutions.[4,13] Further, 62.6% of blindness is due to cataract in 2020 compared to 51.6% in 1997–98. The cumulative loss of GNI has almost doubled, and the cumulative loss of GNI due to avoidable causes has increased 1.8 times compared to 1997 data even after adjusting to inflation. These increases are largely due to the increase in per capita income, economic productivity, labor force, and lifespan, and a general increase in the proportion of avoidable causes of blindness. As these parameters increase, the economic impact of blindness is clearly more severe. The per capita net loss of GNI due to blindness in India is INR 644 (Int$ 28). Between 2016 and 2018, India spent around 3.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care (which is INR 4,381 (~Int$ 199) per capita).[28] Government expenditure was 1.33% of GDP on health care in 2017–18.[17] The total expenditure that can be attributed to preventive care in India is 6.8% (INR 364.8 billion or ~ Int$ 17.37 billion) of the total expenditure.[28] The net loss of GNI due to avoidable causes of blindness in India is INR 689 billion (Int$ 31.3 billion), which is more than the expenditure on all preventable causes in India.[28] To reduce the burden of blindness and visual impairment in India and the subsequent sizeable negative impact on the national economy and productivity, greater investment should be made toward early detection of avoidable conditions such as cataract and refractive error through screening at the primary level and toward providing targeted interventions for avoidable blindness and vision impairment, and increase the cataract surgery targets from the current 6.7 million per year.[4,10,29,30,31] Screening programs should target and identify persons at the primary level by using presenting vision <6/12 in the better eye to reduce the economic impact of blindness and visual impairment.[32,33] The burden of blindness and vision impairment estimates will help advocate the need for accelerated adoption of all four strategies of integrated people-centered eye care (IPCEC) by providing adequate information, which is helpful in budgetary allocation, especially reorienting the model of care by integrating primary eye care horizontally with all levels of primary healthcare and thereby establishing sustainable and efficient preventive care.[34,35]

Need for condition-specific utility measures and disaggregated information

Eye health condition-specific quality of vision and life utility weights combined with qualitative methodologies can measure societal impact and intangible costs and give us a comprehensive understanding of blindness and its economic, social, and cultural impact. The Universal Eye Health Global Action Plan 2014–2019 by the WHO highlights the fact that there is a need for disaggregated local data, human resource development, and infrastructure development for initiatives to reduce blindness prevalence.[36] Understanding and evaluating the economic consequences at a macro but decentralized population level will demonstrate the cost-benefit of investing in eye health as well as act as an important decision-making tool for governments, policymakers, eye care organizations, donors, and other stakeholders in the allocation of resources for eye care in India.

Estimates and their limitations

As recommended in earlier studies,[9,13] we used the GNI per capita over minimum wage to calculate the cost of blindness[6,13] to compare consistently. Furthermore, we have not estimated the cost of treating each of the ocular morbidities as these costs vary in different parts of the country. Cost per capita can give us an estimation of the total outlay needed to be spent on reducing the impact of blindness on GNI. For indirect costs, we considered that caregivers would spend only 20% of their time to take care of the blind; this is a very conservative estimate of indirect costs, and if we increase the time spent caring for a blind person to 50% of the caregiver’s time, the net loss of GNI increases to INR 1,376 billion (Int$ 62.5 billion). We could not find relevant data related to the level of productivity at workplace and cost of caregivers for each of the levels of vision impairment, which could have led to the underestimation of overall potential loss of productivity due to vision impairment. We used WHO disability weights as a surrogate measure for productivity loss due to a reduction in the level of employment of the visually impaired[23,27] as there is a lack of employment-related data for people with each of the levels of vision impairment. We used the projected overall population from the World Bank as relevant Indian census data were only available for 2011;[10] the number of children in India was last estimated in the year 2015–16.[11] Also, we considered the lowest estimate of prevalence of blindness in children as there is no nationwide data; most of these studies were done in South India and among children in blind schools. Further nationwide studies are needed to give us a more region-specific, age- and gender-stratified prevalence of blindness-related data as currently, these are estimates based on few population-based studies.

Conclusion

As the prevalence of overall blindness has decreased considerably in 2020, emphasis has to be made towards early detection of ocular morbidities both in adults and children. This study shows that greater investments are needed towards detection and treatment of avoidable causes of blindness at an early stage in order to reduce the economic burden of blindness in India. The economic burden could be different in different parts of the country due to the lack of disaggregated region-specific prevalence and economic data for adults and children. The results of this study enable key stakeholders to specifically plan budget and specifically allocate resources towards eye care programs and advocacy in the country and facilitate the implementation of the strategies of integrated people-centered eye care (IPCEC).

Financial support and sponsorship

This research is funded by Project Orbis International Inc.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of University of Hyderabad; and Dr. Rahul Ali and Dr. Sethu Sheeladevi, Orbis India Country Office.

References

- 1.New Delhi: 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 25]. National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment, National Blindness &Visual Impairment Survey India 2015-2019-A Summary Report. Available from:https://npcbvi.gov.in/writeReadData/mainlinkFile/File341.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadhwani M, Vashist P, Singh S, Gupta V, Gupta N, Saxena R. Prevalence and causes of childhood blindness in India:A systematic review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:311–5. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2076_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misra N, Khanna RC. Commentary:Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness and diabetic retinopathy in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:381–2. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1133_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna RC. Commentary:Childhood blindness in India:Regional variations. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:1461–2. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1144_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao GN. Vision 2020:The Right to Sight. [cited 2018 Apr 8];Community Eye Heal [Internet] 2000 13(35):42. Available from:https://www.cehjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/download/ceh_13_35_042.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckert KA, Carter MJ, Lansingh VC, Wilson DA, Furtado JM, Frick KD, et al. A simple method for estimating the economic cost of productivity loss due to blindness and moderate to severe visual impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:349–55. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1066394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness :Action plan 2006-2011. 2007. [Last accessed on 2021 Sep 22]. Available from:http://www.who.int/blindness/Vision2020_report.pdf .

- 8.Byford S, Torgerson DJ, Raftery J. Economic note:Cost of illness studies. BMJ. 2000;320:1335. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7245.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frick KD, Foster A. The magnitude and cost of global blindness:An increasing problem that can be alleviated. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:471–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The World Bank, World Development Indicators. World Bank Gr. 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 28]. Available from:https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=IN .

- 11.Mumbai: 2017. [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 31]. International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-2016. Available from:http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gudlavalleti VSM. Magnitude and temporal trends in avoidable blindness in children (ABC) in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:924–9. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shamanna BR, Dandona L, Rao GN. Economic burden of blindness in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1998;46:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York: 1993. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 20]. Inter-Secretariat Working Group on National Accounts C of the EC, System of National Accounts 1993. Available from:https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/1993sna.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO |Visual impairment and blindness. [Last accessed on 2015 Jun 19]. Available from:http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs282/en/print.html .

- 16.New Delhi: 2020. [Last accessed on 2021 Sep 22]. National Statistical Office, Economic Survey 2019-20 Statistical Appendix. Available from:https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/Statistical-Appendix-in- English.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delhi: 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Feb 11]. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Sustainable Development Goals National Indicator Framework Progress Report, 2020. Available from:http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/SDGProgressReport2020.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2020. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 27]. WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000-2019. Available from:https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_daly-methods. pdf?sfvrsn=31b25009_7 . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naidoo KS, Fricke TR, Frick KD, Jong M, Naduvilath TJ, Resnikoff S, et al. Potential Lost productivity resulting from the global burden of Myopia:Systematic review, meta-analysis, and modeling. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques AP, Ramke J, Cairns J, Butt T, Zhang JH, Muirhead D, et al. Global economic productivity losses from vision impairment and blindness. 2021;35:100852. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, National Programme for Control of Blindness. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 08]. Available from:http://npcbvi.nic.in/

- 22.Directorate General Of Health Services. National Programme for Control of Blindness &Visual Impairment. Ministry of Health &Family Welfare, Government of India. 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 May 25]. Available from:https://dghs.gov.in/content/1354_3_NationalProgrammeforControlofBlindnessVisual.aspx .

- 18.Geneva: 2020. World Health Organization. WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000-2019. Available from:https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_daly-methods.pdf?sfvrsn=31b25009_7 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.International Monetary Fund. Implied PPP conversion rate. 2022. [Last accessed date 2022 Jan 27]. Available from:https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPEX@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/DA/IND?year=2018 .

- 25.OECD. Purchasing power parities (PPP) (indicator) OECD2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 16]. Available from:https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm#indicator-chart .

- 26.Labor. United States Dep: 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 08]. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator. Available from:https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=52.5&year1=199711&year2=202002 . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner HC, Lauer JA, Tran BX, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Adjusting for inflation and currency changes within health economic studies. Value Heal. 2019;22:1026–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New Delhi: 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 May 25]. National Health Systems Resource Centre (2019). National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2016-17) Available from:http://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/FINAL National Health Accounts 2016-17 Nov 2019-for Web.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahi JS, Gilbert CE. Pediatr Ophthalmol strabismus. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2012. Epidemiology and world-wide impact of visual impairment in children; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert C, Shukla R, Murthy GVS, Santosha BVM, Gudlavalleti AG, Mukpalkar S, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity:Overview and highlights of an initiative to integrate prevention, screening, and management into the public health system in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:103–7. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2080_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, Das A, Jonas JB, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5:e888–97. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO |Priority eye diseases. WHO. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 07]. Available from:http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/inde×3.html .

- 33.Gudlavalleti VS, Shukla R, Batchu T, Malladi BVS, Gilbert C. Public health system integration of avoidable blindness screening and management, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:705–15. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.212167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das T, Keeffe J, Sivaprasad S, Rao GN. Capacity building for universal eye health coverage in South East Asia beyond 2020. Eye. 2020;34:1262–70. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0801-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 27]. World Report on Vision. Available from:https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328717 . [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Universal eye health:A global action plan 2014-2019. World Health Organization. 2013. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 27]. Available from:https://www.iapb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Universal-Eye-Health_A-Global-Action-Plan-2014-2019.pdf .