Abstract

High-speed railways (HSRs) greatly decrease transportation costs and facilitate the movement of goods, services, and passengers across cities. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, HSRs may contribute to the cross-regional spread of the new coronavirus. This paper evaluates the role of HSRs in spreading Covid-19 from Wuhan to other Chinese cities. We use train frequencies in 1971 and 1990 as instrumental variables. Empirical results from gravity models demonstrate that one more HSR train originating from Wuhan each day before the Wuhan lockdown increases the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases in a city by about 10 percent. The empirical analysis suggests that other transportation modes, including normal-speed trains and airline flights, also contribute to the spread of Covid-19, but their effects are smaller than the effect of HSRs. This paper’s findings indicate that transportation infrastructures, especially HSR trains originating from a city where a pandemic broke out, can be important factors promoting the spread of an infectious disease.

Keywords: High-speed rails, Covid-19, Pandemic, Transportation infrastructure

1. Introduction

More than two-thirds of the high-speed railways (HSRs) in the world are built in China. According to the report of China’s Ministry of Transport, HSRs accomplished a ridership of 3.66 billion passengers in 2019, accounting for about 70 percent of the total railway passenger traffic. The passenger volume of HSRs was about four times that of civil aviation in 2019. With a much higher speed, HSRs greatly decrease transportation costs and facilitate the movement of goods, services, and passengers across cities (Chen et al., 2016, Heuermann and Schmieder, 2019, Lawrence et al., 2019).

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, HSRs may contribute to the cross-regional spread of the new coronavirus. The Wuhan lockdown on January 23, 2020, two days before the Spring Festival, marked the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in China. All trains and flights from and to Wuhan were canceled as the Wuhan lockdown began. The railway and airline services in Wuhan were not resumed until April 8, 2020. Epidemiological investigations show that most confirmed cases in other cities had traveled to Wuhan or had close contact with individuals returning from Wuhan at the early stage of the pandemic (Han et al., 2020). Thus, HSR trains can play an important role in spreading Covid-19 from Wuhan to other cities before the Wuhan lockdown. This is especially true because of the Spring Festival travel season (Chunyun), which is the largest annual human movement in the world and usually starts 15 days before the Spring Festival.

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the effect of HSRs and other transportation infrastructures on spreading Covid-19 from Wuhan to other Chinese cities at the early stage of the pandemic. Specifically, we rely on a gravity equation to estimate the elasticity of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city with respect to the number of HSR trains from Wuhan. To solve potential endogeneity issues, we use historical train connections to Wuhan as instrumental variables (IVs).

HSRs can contribute to the spread of Covid-19 in two ways. First, HSRs can directly transport passengers carrying the new coronavirus from Wuhan to other cities (Zheng et al., 2020). The second channel is that healthy passengers may get infected if they ride on the same HSR train with Covid-19 patients (Morawska et al., 2020, Hu et al., 2021). This paper studies the aggregate effect of the above two mechanisms. The estimates in this paper reflect the HSRs’ effect on spreading Covid-19 before the Wuhan lockdown when most social-distancing measures were not enforced. HSRs’ effect can be smaller if passengers follow the current social-distancing measures, including keeping distance from each other and wearing a mask. Thus, this paper’s estimates should be interpreted with care.

This paper has the following contributions. First, this paper proposes using historical train connections to Wuhan as IVs for the HSR connections with Wuhan in 2020. This identification strategy complements existing studies that usually use OLS models to study the effect of HSRs on spreading Covid-19. Second, this paper complements the literature on HSRs by demonstrating that in addition to affecting all kinds of economic outcomes, HSRs also contribute to the spread of infectious diseases. Third, this paper’s results suggest the importance of studying the number of HSR train frequencies (the “intensive margin”). Most current studies on HSRs focus on whether a city had an HSR station (the “extensive margin”) and few studies consider the intensity of HSR connections among cities. A more detailed discussion of this paper’s relationship to existing studies is presented in Section 2.

The rest of the paper consists of four sections. Section 2 reviews the current literature that is closely related to this paper. Section 3 introduces data and empirical strategies. Empirical results are shown in Section 4 and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review

This paper is mainly related to two strands of literature. First, this paper contributes to a rising literature investigating factors and policies that accelerate or slow the transmission of Covid-19. The current studies based on China and other countries have found that weather conditions and air pollution affect the spread of Covid-19 and the fatality rate of the coronavirus (Conticini et al., 2020, Sajadi et al., 2020, Qi et al., 2020, Shi et al., 2020, Tosepu et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020, Cartenì et al., 2021a). Specifically, temperature is found to be negatively associated with the infection risk of Covid-19 while the results on humidity are mixed. Please see McClymont and Hu (2021) for a more detailed review.

In addition to natural factors, human activities, including social activities, college student travel, inter-regional migration, in-person elections, and the concentration of population in public facilities, can also increase the spread of the novel coronavirus (Kuchler et al., 2020, Mangrum and Niekamp, 2020, Li and Ma, 2021, Mu et al., 2021, Loo et al., 2021, Palguta et al., 2021). These studies generally conclude that activities that encourage the concentration of population increase the infection risk of Covid-19.

More relevant to this paper, some studies investigate the probability of Covid-19 infection within transportation facilities. Due to the closed nature of transport vehicles, current research shows that transportation and the use of transportation facilities also promote the transmission of Covid-19. The usage of public transit, including buses, subways, and school buses, is found to contribute to the spread of Covid-19 in Italy and the US (Cartenì et al., 2021b, Ramirez et al., 2021, Thomas et al., 2022). Related studies on China are few. Better access to railroads increases the number of Covid-19 cases in Italy (Cartenì et al., 2021c). Air travel can also increase the infection risk of the novel coronavirus worldwide (Nakamura and Managi, 2020, Pombal et al., 2020).

In addition to public transit, railroads, and airlines, several studies have evaluated the effect of HSRs on spreading Covid-19 (Zhang et al., 2020, Li et al., 2021, Zhu and Guo, 2021). These studies focus on China and investigate the transmission of Covid-19 from Wuhan to other Chinese cities. Studies on the same topic in other countries are limited. The existing studies rely on OLS models and do not account for the potential endogeneity of HSR connections to Wuhan. In this paper, we complement the OLS estimates by using historical train connections to Wuhan as IVs. The estimates from using IVs are found to be larger than the OLS estimates, suggesting potential endogeneity issues may bias the OLS estimates towards zero. Another extension beyond existing studies is that this paper highlights the effect of HSR trains originating from Wuhan. As HSR trains originating from Wuhan carry much more Wuhan passengers than HSR trains originating from other cities and having a stop at Wuhan, HSR trains originating from Wuhan can contribute more to the spread of Covid-19 from Wuhan to other cities.

To contain the spread of Covid-19, all kinds of quarantine measures and social-distancing policies are implemented. Lockdown policies, mainly adopted by Chinese cities, have been found to effectively reduce or completely eliminate Covid-19 cases (Chinazzi et al., 2020, Fang et al., 2020, Lau et al., 2020, Qiu et al., 2020, Tian et al., 2020). Some more modest mobility-control policies taken by many cities in the US and Europe, including shelter-in-place orders, international travel restrictions, and work-from-home measures, are also able to decrease the infection risk of Covid-19 (Dave et al., 2020, Kraemer et al., 2020, Chiba, 2021). In addition to social-distancing policies, vaccination is another important measure to contain the spread of Covid-19 (Shinde et al., 2021, Thomas et al., 2021, Eyre et al., 2022).

Second, this study adds to the literature evaluating the economic and social consequences of HSRs. There has been an emerging literature studying the effect of HSRs on different types of economic outcomes in the past five years. As China experienced the largest wave of HSR construction in the past twenty years, many studies investigated HSRs’ effect by using Chinese datasets. HSRs are found to affect airline traffic, increase employment, affect GDP and income, promote academic cooperation, and encourage innovation by decreasing transportation costs in China (Chen et al., 2016, Lin, 2017, Ke et al., 2017, Dai et al., 2018, Yu et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019, Dong et al., 2020, Gao and Zheng, 2020, Hanley et al., 2022). In other countries, existing studies also confirm that HSRs increase the GDP per capita, improve productivity, and affect airline passenger flows (Cascetta et al., 2020, Avogadro et al., 2021, Bhatt and Kato, 2021, Miwa et al., 2022). This paper complements existing studies by demonstrating that HSRs also contribute to the spread of a contagious disease.

This paper’s results suggest the importance of studying the number of HSR train frequencies (the “intensive margin”). Most current studies focus on whether a city had an HSR station (the “extensive margin”) and analyze its impact on economic activities (Lin, 2017, Ke et al., 2017, Yu et al., 2019, Cascetta et al., 2020, Dong et al., 2020, Gao and Zheng, 2020, Bhatt and Kato, 2021). Few studies consider the intensity of HSR connections among cities. This paper finds that whether a city has HSRs or not has no significant effect on the number of Covid-19 cases while the number of HSR trains originating from Wuhan does have a significant impact. Given most cities in China have already connected to the national HSR network, this paper’s findings indicate that it is important to evaluate the effect of HSR train frequencies in future studies.

3. Empirical strategies

3.1. Data and summary statistics

We construct a cross-sectional dataset with 275 prefecture cities (including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) in China. Due to data availability, the cities in four western provinces or autonomous regions (Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and Qinghai) are excluded from the analysis. The cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in each city by February 6, 2020, two weeks after the Wuhan lockdown, is obtained from China Data Lab.1 We focus on the number of confirmed Covid-19 cases within two weeks after the Wuhan lockdown because the incubation period of Covid-19 can be up to two weeks. The confirmed cases before February 6, 2020 are more likely to originate from Wuhan.

The GDP, the population, the number of medical institutions, and the number of medical staff in each city in 2019 are assembled from local governments’ statistical reports or announcements. Each city’s straight-line distance to Wuhan and the geographic coordinates of city centers are calculated by ArcGIS using a map of prefecture cities. The weather conditions of each city in January 2020 are assembled from weather observatory stations.

For each city in the sample, we calculate the average daily number of HSR trains from Wuhan during the third week of January 2020 (from January 13, 2020 to January 19, 2020) from the “12306 China Railway” website.2 We focus on the third week of January 2020 for two reasons. The first reason is that the HSR train schedules in the third week of January 2020 can be different from the schedules in the earlier weeks because of the Spring Festival travel season. The government sometimes opens additional HSR trains in the Spring Festival travel season to accommodate the soaring travel demand. The second reason is that this week is right before the outbreak of the pandemic (Wuhan lockdown) and HSR trains this week may have the largest impact on spreading Covid-19.

We use two variables to measure the level of HSR connections to Wuhan: the daily number of HSR trains from Wuhan and the daily number of HSR trains originating from Wuhan. The number of HSR trains from Wuhan includes HSR trains originating from Wuhan and HSR trains starting from other cities but having a stop at Wuhan. As most of the tickets for a train are reserved for passengers in the departure city, the HSR trains originating from Wuhan carry much more passengers from Wuhan and may have a larger effect on spreading the new coronavirus to other cities. For example, for an HSR train from Wuhan to Shanghai, most of the passengers on the train usually get on board in Wuhan. For an HSR train that departs from Chengdu to Shanghai but stops in Wuhan, the number of passengers boarding the train in Wuhan is much fewer. Note that passengers know the departure station of each train when they buy a train ticket, and thus know whether a train departs from Wuhan.

We calculate the daily number of normal-speed trains from Wuhan and the daily number of normal-speed trains originating from Wuhan by exploring the train schedules between January 13, 2020 and January 19, 2020, from the “12306 China Railway” website. The average daily number of flights from Wuhan to other cities during the same period is obtained from VariFlight, a professional aviation data provider.3

We use train connections to Wuhan in the past as IVs. Specifically, we assemble the daily number of trains from (and originating from) Wuhan to each city in 1990 and 1971 by exploring the “National Railway Train Timetable”, which publishes the schedules for all trains in China in selected years. Similarly, whether a city had an airport in 1980 is used as an instrument for the number of air flights from Wuhan. We searched government announcements, official documents, and other information on the internet to find out whether a city had an airport in 1980.

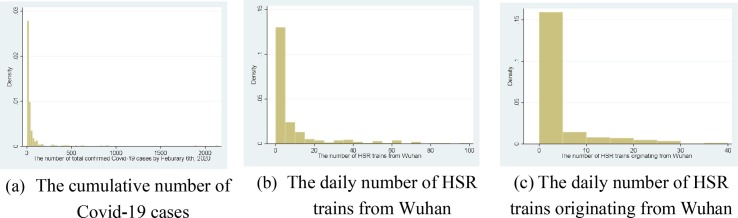

The summary statistics for the variables mentioned above are shown in Table 1 . On average, each city had 70 cumulative Covid-19 cases by February 6, 2020. About 85 percent of the cities are connected to the HSR network. Each city on average had 8.73 HSR trains from Wuhan and 3.47 HSR trains originating from Wuhan in a day. The distributions for the number of Covid-19 cases and the number of HSR trains from (and originating from) Wuhan are shown in Fig. 1 .

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key variables: | ||||

| The cumulative number of Covid-19 cases by February 6, 2020 | 70 | 205 | 1 | 2141 |

| The cumulative number of Covid-19 cases by January 30, 2020 | 25 | 63 | 0 | 573 |

| Has HSR or not (=1 if has HSR) | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 |

| No. of HSR trains from Wuhan | 8.76 | 17.11 | 0 | 98 |

| No. of HSR trains originating from Wuhan | 3.48 | 7.00 | 0 | 40 |

| No. of normal-speed trains from Wuhan | 4.29 | 7.51 | 0 | 51 |

| No. of normal-speed trains originating from Wuhan | 0.57 | 1.07 | 0 | 6 |

| No. of air flights from Wuhan | 0.95 | 2.69 | 0 | 17 |

| Population (in millions) | 4.68 | 3.54 | 0.42 | 31.24 |

| GDP (in billions of RMB) | 332.42 | 469.71 | 13.86 | 3815.53 |

| No. of medical institutions | 2955 | 2369 | 111 | 21,058 |

| No. of medical staff (in thousands) | 33.47 | 33.31 | 4.00 | 282.00 |

| The instrumental variables: | ||||

| No. of trains from Wuhan in 1990 | 1.32 | 3.48 | 0 | 25 |

| No. of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 | 0.56 | 1.71 | 0 | 17 |

| No. of trains from Wuhan in 1971 | 0.60 | 1.83 | 0 | 13 |

| No. of trains originating from Wuhan in 1971 | 0.26 | 1.01 | 0 | 10 |

| Had an airport in 1980 or not (=1 if had an airport) | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 |

Fig. 1.

The distribution of the number of Covid-19 cases and the number of HSR trains.

Each city had 4.29 and 0.57 normal-speed trains from and originating from Wuhan in a day, respectively. The number of HSR trains from Wuhan greatly exceeds the number of normal-speed trains from Wuhan. On average, each city had 0.95 flights from Wuhan in a day. Each city had 1.32 trains from Wuhan in 1990 and this number decreased to 0.60 trains in 1971. The daily number of trains originating from Wuhan was 0.56 and 0.26 trains in 1990 and 1971, respectively. The share of cities that had an airport in 1980 is 15 percent.

3.2. Empirical specifications

Our empirical specification follows a gravity model, which has been widely used in modeling trade and population flows between countries or regions (Head and Mayer, 2014). The gravity model states that the volume of trade or population flows between two countries or cities is proportional to their economic mass and a measure of their relative trade or flow frictions. One friction often considered in the literature is transportation cost (Mátyás, 1997, Anderson, 2011).

Following the setting of a gravity model, the empirical specification is set as follows:

| (1) |

-

•

is the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in city . is a constant term.

-

•

and represent the characteristics of Wuhan and city , respectively. We use subscript to represent Wuhan. City characteristics include population, GDP, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the longitude and latitude coordinates of the city center, and weather conditions. The population and GDP are used to account for potential economic or trade links between Wuhan and city . The numbers of medical institutions and medical staff measure the levels of medical services in city . The coordinates of city centers and weather conditions (including the average temperature and precipitation in January 2020) are used to account for the effect of latitude and weather on the spread of Covid-19.

-

•

is the product of city characteristics for city and Wuhan. and represent the exponents of powers and need to be estimated.

-

•

is the transportation cost between Wuhan and city . It depends on the straight-line distance () and the number of HSR trains from (originating from) Wuhan (). With a correlation coefficient of 0.99, the straight-line distance is highly correlated with the highway distance between Wuhan and city .4 Thus, the straight-line distance variable can largely capture the effect of highway trips using private cars. For simplicity, we assume the functional form of the transportation cost function is: . and are parameters that need to be estimated.

To get semi-elasticity estimates, avoid the effect of extreme values on estimation, and have a linear-regression form, we take equivalent logarithm transformations of Equation (1) and rearrange to get Equation (2):

| (2) |

In Equation (2), a constant term is denoted by , which equals . An error term is denoted by . The parameter represents the effect of one more HSR train from (originating from) Wuhan on the number of Covid-19 cases in city .

The Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan is unexpected and we do not have reverse causality problems in estimating Equation (2) by OLS. However, we may suffer from omitted-variable biases, as some uncontrolled factors can simultaneously affect the HSR connections to Wuhan and the number of Covid-19 cases. For example, the government officials of a city may be more passionate about building HSRs and this city thus has more HSR trains from Wuhan. If this city’s government officials are also more competent in implementing social-distancing measures, this city is likely to have fewer confirmed Covid-19 cases. Thus, the government officials’ personalities and competence can lead to more HSR trains from Wuhan and fewer Covid-19 cases. In this case, the omitted-variable problem will bias the OLS estimates towards zero.

Following the literature (Baum-Snow, 2007, Duranton and Turner, 2011, Duranton and Turner, 2012, Garcia-López et al., 2015, Baum-Snow et al., 2017, Dong et al., 2020), we choose to use historical variables as instruments to solve this identification problem. As summarized by Redding and Turner (2015), using historical variables as instruments is one of the major identification strategies in evaluating the impact of transportation infrastructures. For example, Baum-Snow et al. (2017) uses the railways in 1964 as an instrument to study the effect of highways, railroads, and ring roads on city growth in China. In this paper, we use the number of trains from (and originating from) Wuhan in 1990 and the number of trains from (and originating from) Wuhan in 1971 as IVs. These instruments are good predictors of the HSR connections in 2020, as cities that had lots of train connections to Wuhan in the past are more likely to have more HSR trains from Wuhan before the Wuhan lockdown. Thus, the relevance requirement of these IVs is satisfied.

The validity of these IVs hinges on the assumption that factors determining the train connections to Wuhan in the past are not correlated with potential unobserved variables that affect the transmission of Covid-19 at the early stage of the pandemic. The length of railroads in China started to grow rapidly in the 2000s and China had no HSRs before 2008. About half of Chinese railroads before 1990 were built before the People’s Republic’s establishment in 1949. Much of the railroad investment before 1990 was under Soviet influence and served to connect resource-rich regions of the west with manufacturing centers in the east (Baum-Snow et al., 2017). Therefore, it is plausible that the construction of rail networks before 1990, and thus the number of trains between Wuhan and a city in 1990 or 1971, was determined by factors unrelated to the transmission of Covid-19 in 2020.

Another argument for the validity of the instruments is that the growth of cities and the current distribution of economic activities in China are largely shaped by the “reform and opening-up” policy. China did not adopt this policy in 1971 and had just started the “reform and opening-up” process in 1990. Much of the economic and trade links among cities before 1990 were from the planned economy regime. After thirty years of rapid growth, China has established a market-oriented economy. Thus, the transmission of Covid-19 in 2020 was not likely to be determined by the train connections in 1990 and 1971.

In evaluating the effect of airline flights, we are unable to find the flight schedules between Wuhan and other cities before 1990. Therefore, we cannot use the number of flights from Wuhan in the past as an IV. Instead, we use whether a city had an airport in 1980 as an instrument for the number of flights from Wuhan in January 2020. The rapid development of China's aviation industry began in the 1990s. The number of airline passengers increased from 17 million in 1990 to 552 million in 2017. Most airports in China in 1980 were dual-use airports, i.e., the airports were used for both military and civilian purposes. Thus, whether a city had an airport in 1980 was mostly determined by factors unrelated to the spread of Covid-19. Whether a city had an airport in 1980 can strongly predict the number of flights from Wuhan. These arguments support the validity and strength of this IV.

4. Results

4.1. The effect of HSR trains on the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases

The major empirical results are summarized in Table 2 . All city characteristics are included in the regressions but omitted in the text to save space. The cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city is found to significantly decrease with the straight-line distance to Wuhan and increase with this city’s GDP. These effects are consistent with expectations. Cities that are farther away from Wuhan have higher transportation costs to Wuhan and thus have fewer Covid-19 cases. Cities with a higher GDP tend to have more economic and trade connections with Wuhan and receive more passenger flows and Covid-19 cases from Wuhan. The effect of other city characteristics is not statistically significant. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Table 2.

The effect of HSR trains on the number of Covid-19 cases.

| Variables | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS results | IV-Train connections in 1990 | IV-Train connections in 1971 | IV-Both IVs | ||||||

| Has HSR or not | 0.0778 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (0.206) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| No. of HSR trains from WH | – | 0.0111** | – | 0.0114 | – | 0.0181 | – | 0.00948 | – |

| – | (0.00455) | – | (0.00704) | – | (0.0113) | – | (0.00644) | – | |

| No. of HSR trains originating | – | – | 0.0404*** | – | 0.121*** | – | 0.103** | – | 0.103** |

| from WH | – | – | (0.0112) | – | (0.0470) | – | (0.0481) | – | (0.0481) |

| First-stage F statistics | – | – | – | 44.48 | 17.51 | 18.81 | 12.60 | 24.22 | 12.60 |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.635 | 0.644 | 0.655 | 0.644 | 0.575 | 0.641 | 0.607 | 0.644 | 0.607 |

The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city by February 6, 2020 (two weeks after the Wuhan lockdown). The number of trains from Wuhan in 1990 is used as an IV in column (4). The number of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 is used as an IV in column (5). The number of trains from and originating from Wuhan in 1971 are used as instruments in columns (6) and (7), respectively. In columns (8), we use the numbers of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 as IVs. The numbers of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs in column (9). p-values of over-identification tests are 0.26 and 0.23 in columns (8) and (9), respectively. Controlled but not listed city covariates include population, GDP, the straight-line distance to Wuhan, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the geographic coordinates of city centers, the average temperature in January 2020, and the average precipitation in January 2020. WH represents Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The OLS results following Equation (2) are shown in columns (1)-(3). The results in column (1) suggest whether a city is connected to the HSR network or not has no significant effect on the dependent variable. However, the number of HSR trains from Wuhan does have a significantly positive effect on the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases. The results in column (2) suggest one more HSR train from Wuhan each day can increase the Covid-19 cases in a city by one percent. In column (3), we find that one more HSR train originating from Wuhan each day significantly increases a city’s Covid-19 cases by four percent. The effect of HSR trains originating from Wuhan is much larger, consistent with the expectation that trains originating from Wuhan carry much more Wuhan passengers and tend to contribute more to the spread of the Covid-19 from Wuhan to other cities.

Columns (4)-(9) display the two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression results. The first-stage regression results are displayed in Table A.1. The daily number of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are good predictors for the daily number of HSR trains from Wuhan. In column (4) of Table 2, after instrumenting the number of HSR trains from Wuhan with the number of trains from Wuhan in 1990, the empirical results demonstrate that one more HSR train from Wuhan each day will increase the Covid-19 cases by one percent. This estimate, however, becomes statistically insignificant. In column (5), the number of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 is used as an instrument and the results suggest one more HSR train originating from Wuhan each day significantly increases the Covid-19 cases by 12 percent. This IV estimate is statistically significant and larger than the OLS estimate in column (3), suggesting potential confounding factors tend to bias the OLS estimates toward zero.

In columns (6)-(7), we use the number of trains from Wuhan in 1971 and the number of trains originating from Wuhan in 1971 as instruments. Compared with the 1990 IV, the number of trains from Wuhan in 1971 can be more valid, as the latter has a much longer lag. Nevertheless, the empirical results from the 1971 IVs are qualitatively and quantitively similar to the results when the 1990 IVs are used. The regression results by using both the 1990 and the 1971 IVs are reported in columns (8)-(9). The empirical estimates are still robust.

All IV regressions have a strong first stage.5 The null hypothesis of the over-identification tests is not rejected when we include both IVs in columns (8)-(9). This suggests the validity of the 1990 IVs is not statistically different from the validity of the 1971 IVs.

The empirical estimates in Table 2 are generally consistent with existing studies that also find HSRs contribute to the spread of Covid-19. However, the IV estimates in this paper are larger than the estimates in other studies that usually rely on OLS models. For example, Zhang et al. (2020) find that one more HSR train from Wuhan increases the number of Covid-19 cases by about 0.004 cases, which is much smaller than the IV estimates in this paper. Zhu and Guo (2021) conclude that cities connected to Wuhan by HSRs have 25 percent more Covid-19 cases than other cities, but they did not estimate the effect of one additional HSR train on the number of Covid-19 cases. Li et al. (2021) focus on provinces instead of cities, though they also find that HSRs promote the spread of Covid-19. Thus, this paper complements existing studies by offering new estimates from a more valid identification strategy.

4.2. Comparing the effect of HSRs with other transportation modes

In addition to HSRs, we also evaluate the role of normal-speed trains and air flights in spreading Covid-19 from Wuhan to other cities. The empirical specification still follows Equation (2). Similarly, historical variables are used as IVs to ease concerns about endogeneity problems.

The OLS results in column (1) of Table 3 indicate that one more normal-speed train from Wuhan each day can increase the number of Covid-19 cases by 2.2 percent. This estimate increases to 19.5 percent for one more normal-speed train originating from Wuhan each day in column (2). Note that the capacity of a normal-speed train is up to two thousand passengers while the capacity of an HSR train is usually smaller than one thousand passengers. Thus, a normal-speed train can carry much more passengers than an HSR train. This may explain why one more normal-speed train originating from Wuhan has a larger effect than an HSR train originating from Wuhan. The 2SLS results are qualitatively similar in columns (3) and (4) where we use the number of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 as instruments. The estimated effect of normal-speed trains originating from Wuhan in column (4), however, is only statistically significant at the 10 % significance level.

Table 3.

The effects of normal-speed trains and airline flights.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Normal-speed trains |

Air flights |

||||

| OLS | IV | OLS | IV | |||

| No. of normal-speed trains from WH | 0.0225** | – | 0.0169* | – | – | – |

| (0.00875) | – | (0.0100) | – | – | – | |

| No. of normal-speed trains originating | – | 0.195*** | – | 0.283* | – | – |

| from WH | – | (0.0563) | – | (0.166) | – | – |

| No. of air flights from WH | – | – | – | – | 0.125*** | 0.175*** |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0225) | (0.0634) | |

| First-stage F statistics | – | – | 76.73 | 15.09 | – | 20.07 |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.644 | 0.649 | 0.643 | 0.646 | 0.667 | 0.662 |

The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city by February 6, 2020. The numbers of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs in column (3). The numbers of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs in column (4). The p-values of over-identification tests are 0.26 and 0.21 in columns (3) and (4). Whether a city has an airport in 1980 is used as an IV in column (6). Controlled but not listed city covariates include population, GDP, the straight-line distance to Wuhan, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the geographic coordinates of city centers, the average temperature in January 2020, and the average precipitation in January 2020. WH represents Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Air flights are also found to have a significant positive effect on the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases in columns (5) and (6). The OLS results suggest one more daily flight from Wuhan before the outbreak of the pandemic increases the number of Covid-19 cases in the destination city by 12.5 percent. This effect increases to 17.5 percent when we use whether a city has an airport in 1980 as an instrument. Note that the infection risk in a plane cabin is larger than the infection risk in a train car (Hu et al., 2020). This might explain why a plane usually carries fewer passengers than a train but the effect of one more flight from Wuhan is similar to the effect of one more normal-speed train originating from Wuhan.

To compare the effect of different transportation modes, we further convert the semi-elasticity estimates in Table 2 and Table 3 to elasticity estimates. We multiply the estimated effect of one more train or flight from Wuhan by the average level of train or flight connections to Wuhan to get the elasticity estimate.6 This conversion accounts for the fact that the number of HSR trains, normal-speed trains, and airline flights from Wuhan is different across cities. The elasticity estimates in Table 4 suggest the HSR trains originating from Wuhan have the largest impact on spreading Covid-19. A ten percent increase in the daily number of HSR trains originating from Wuhan can increase the number of Covid-19 cases in the destination city by 3.5 percent. A ten percent increase in the daily number of flights from Wuhan and normal-speed trains originating from Wuhan can increase the number of Covid-19 cases in the destination city by 1.7 and 1.6 percent, respectively.7 The elasticity estimates for HSR trains from Wuhan and normal-speed trains from Wuhan are all below 0.1.

Table 4.

Elasticity estimates.

| The estimated effect of one more train or flight from WH | The average number of trains or flights from WH | Converted elasticities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSR trains from WH | 0.0095 | 8.76 | 0.083 |

| HSR trains originating from WH | 0.10 | 3.48 | 0.35 |

| Normal-speed trains from WH | 0.017 | 4.29 | 0.073 |

| Normal-speed trains originating from WH | 0.28 | 0.57 | 0.16 |

| Air flights from WH | 0.18 | 0.95 | 0.17 |

4.3. Robustness checks

We conduct a series of robustness checks for the major result in Table 2 that HSRs significantly improve the spread of Covid-19 from Wuhan to other cities. The first exercise is conducting a placebo test where we evaluate the effect of HSR trains from an alternative city on the number of Covid-19 cases. Specifically, we choose four regional center cities that are geographically close to Wuhan: Zhengzhou, Hefei, Changsha, and Nanchang. These four provincial capital cities are similar to Wuhan in GDP, population, and geographical locations. The regression results in columns (1)-(4) in Table 5 suggest the number of HSR trains from these four alternative cities have small and insignificant effects on the number of Covid-19 cases. This result is consistent with the expectation that the Covid-19 spreads from Wuhan to other cities and the number of HSR trains from these four alternative cities should have a zero effect on the transmission of Covid-19.

Table 5.

Robustness checks.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhengzhou | Hefei | Changsha | Nanchang | |

| No. of HSR trains from | −0.00510 | −0.00530 | 0.00101 | 0.00246 |

| alternative cities | (0.00380) | (0.00477) | (0.00322) | (0.00419) |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 274 | 274 | 274 | 274 |

| R-squared | 0.634 | 0.634 | 0.631 | 0.632 |

| (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Exclude cities in the Hubei province | Use the number of Covid-19 cases before January 30th, 2020 | |||

| No. of HSR trains from WH | 0.0120*** | – | 0.0107* | – |

| (0.00459) | – | (0.00627) | – | |

| No. of HSR trains originating | – | 0.0675*** | – | 0.106** |

| from WH | – | (0.0245) | – | (0.0430) |

| First-stage F statistics | 42.96 | 26.53 | 42.82 | 13.41 |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 260 | 260 | 275 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.613 | 0.577 | 0.597 | 0.554 |

The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city by February 6, 2020, for columns (1)-(6). The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases in a city by January 30, 2020, in columns (7)-(8). Columns (1)-(4) show OLS regression results. The numbers of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs in columns (5) and (7). The numbers of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs in columns (6) and (8). The over-identification tests cannot reject the null that both IVs are valid in columns (5)-(8). Controlled but not listed city covariates include population, GDP, the straight-line distance to Wuhan, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the geographic coordinates of city centers, the average temperature in January 2020, and the average precipitation in January 2020. WH represents Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The second robustness check is excluding the cities in Hubei province. The 2SLS results in columns (5)-(6) of Table 5 indicate the effect of HSR trains is robust after excluding the cities in Hubei province. In the third exercise, we test the robustness of the empirical results by focusing on the number of cumulative Covid-19 cases within one week after the Wuhan lockdown (before January 30, 2020). The results in columns (7)-(8) are qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those in Table 2.8

In the fourth robustness check, we test the sensitivity of the empirical results in Table 2 by including other modes of transportation in the regression. Columns (1), (2) of Table A2 display the OLS results when all three types of transportation modes are included in the regression. After controlling for the frequencies of normal-speed trains and the number of air flights from Wuhan, the number of HSR trains from Wuhan has an insignificant positive effect on the dependent variable in column (1). The effect of HSR trains originating from Wuhan, however, remains statistically significant in column (2). The magnitude of the estimate in column (2) is close to that of the estimate in column (3) of Table 2. The corresponding 2SLS results shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table A2 display similar patterns.

4.4. Potential heterogeneities

Several potential heterogeneities are explored, and the empirical results are displayed in Table 6 . This subsection focuses on the potential heterogeneous effects of HSR trains originating from Wuhan. We interact the number of HSR trains originating from Wuhan with a dummy variable to identify possible heterogeneous effects. For example, to study the heterogeneity over GDP, we define a dummy variable that equals one for cities with GDP more than 400 billion RMB in 2019, and equals zero for other cities.9 All regressions are estimated by 2SLS and the interactions of the historical variables with the heterogeneity dummy variable are used as instruments for the interactions of the HSR variables with the heterogeneity dummy variable.

Table 6.

Potential heterogeneities.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of HSR trains originating | 0.111** | 0.117** | 0.109** | −0.00382 | 0.0731* |

| from WH () | (0.0517) | (0.0472) | (0.0465) | (0.0537) | (0.0406) |

| −0.00741 | – | – | – | – | |

| (0.0532) | – | – | – | – | |

| – | −0.0353 | – | – | – | |

| – | (0.0387) | – | – | – | |

| – | – | −0.0249 | – | – | |

| – | – | (0.0731) | – | – | |

| – | – | – | 0.0959*** | – | |

| – | – | – | (0.0362) | – | |

| – | – | – | – | 0.0646*** | |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0246) | |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.600 | 0.606 | 0.595 | 0.643 | 0.578 |

The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases in a city by February 6, 2020. All results are from 2SLS regressions by using the numbers of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 as IVs. is a dummy variable that equals one for about 25 percent of cities whose GDP is larger than 400 billion RMB. is a dummy that equals one for 25 percent of cities whose population is larger than five million. is a dummy that equals one for 25 percent of cities whose distance to Wuhan is longer than one thousand kilometers. is a dummy that equals one for the top 25 % of cities that received the most travelers from Wuhan between January 1, 2020, and January 7, 2020 (measured by the Baidu migration index). is a dummy variable that equals one for cities (31 percent) that adopt lockdown policies after the Covid-19 outbreak (He et al., 2020). WH represents Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The results in column (1) of Table 6 indicate that there are no significant heterogeneous effect across GDP, i.e., the effect of HSR trains originating from Wuhan is homogeneous for cities with different levels of GDP. As shown in columns (2) and (3), similar homogeneous results are found for the city population and the straight-line distance to Wuhan. In column (4), the Baidu migration index is used to measure the number of Wuhan travelers to a city.10 The empirical results suggest that HSRs’ effect in cities that received more Wuhan passengers between January 1, 2020 and January 7, 2020 is significantly larger than the effect in cities that have fewer visitors from Wuhan. This result is consistent with the expectation that HSR trains promote the spread of Covid-19 by facilitating the inter-city flow of passengers. The estimates in column (5) demonstrate that HSR trains originating from Wuhan have a larger effect in cities that adopt lockdown policies after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.11 This result suggests that cities that have more HSR trains originating from Wuhan tend to have more Covid-19 cases at the early stage of the pandemic and the local governments of these cities are more likely to adopt lockdown policies to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates the role of HSR trains in spreading Covid-19 from Wuhan to other Chinese cities. The historical number of train frequencies from Wuhan are used as instrumental variables. The empirical results demonstrate one more HSR train from Wuhan to a city each day increases the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in this city by about one percent. One more HSR train originating from Wuhan each day, however, can increase the Covid-19 cases by about 10 percent. The empirical analysis suggests other transportation modes, including normal-speed trains and air flights, also contribute to the spread of Covid-19, but their effects (elasticity estimates) tend to be smaller. This paper’s findings suggest transportation infrastructures, especially HSR trains originating from a city where a pandemic broke out, can be important factors promoting the spread of an infectious disease. The estimates in this paper should be considered in making social distancing and reopening policies. In addition to HSR trains, normal-speed trains, and air flights, public transportation can also greatly affect the transmission of Covid-19, especially within cities. This topic merits future research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jindong Pang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Youle He: Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization. Shulin Shen: Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Jindong Pang and Shulin Shen thank the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71903145 and 71903060, respectively).

The data source is https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/chinadatalab/home. The imported Covid-19 cases from other countries are excluded from the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases in a city.

This website is the official website for booking train tickets in China: https://www.12306.cn/index/. Wuhan has three train stations: Wuhan station, Wuchang station, and Hankou station.

The flight data can be downloaded from VariFlight: https://www.variflight.com/en?AE71649A58c77=.

The F statistics for the first stage is 12.6 when both the number of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and the number of trains originating from Wuhan in 1971 are used as IVs in column (9). To test whether the empirical results are sensitive to potential weak-IV issues, we also try to conduct the IV estimation with limited-information maximum likelihood (LIML) method. The estimates from the LIML method are less sensitive to weak-IV issues. The empirical results (available upon request) from the LIML method are qualitatively and quantitatively similar to the results in Table 2.

For example, an average city has 3.5 HSR trains originating from Wuhan. Based on the estimates in column (9) of Table 2, one more HSR train originating from Wuhan (a 29 percent increase) will increase the number of Covid-19 cases by 10 percent. This indicates an elasticity of 0.35.

Although both a normal-speed train originating from Wuhan and an air flight from Wuhan have a larger positive effect on the dependent variable than an HSR train originating from Wuhan, the elasticity estimates for the formers are smaller than the latter. The reason is that, as shown in Table 1, a city has far more HSR trains originating from Wuhan than the number of normal-speed trains and flights from Wuhan.

We also conduct the same series of robustness checks for the estimates of normal-speed trains and air flights. Due to space, these results are not presented in the paper and are available upon request.

About one fourth of the cities in sample have a GDP of more than 400 billion RMB in 2019. We also experiment with other cut-offs (e.g., 190 billion RMB, the 50% cut-off) and the empirical results are qualitatively similar.

This Baidu migration index reflects the daily intensity of population movements from Wuhan to another city by all modes of travel. A larger value of this index denotes more passengers traveled from Wuhan to a city.

Following He et al. (2020), lockdown cities are defined as cities that adopted the following policies: (1) prohibition of unnecessary commercial activities in people’s daily lives; (2) prohibition of any types of gathering by residents; (3) restrictions on private (vehicle) and public transportation. The share of lockdown cities in the sample is about 31 percent.

We use Baidu map to calculate the shortest distance if one drives from Wuhan to a city by highways. With a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99, this highway distance is highly correlated the straight-line distance between Wuhan and this city. The Spearman correlation coefficient of these two variables is also 0.99. We may suffer multicollinearity issues if both the highway distance and straight-line distance are included in the regression. Therefore, we only keep the straight-line distance in the regression.

Appendix A.

.

Table A1.

First-stage regression results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HSR trains from WH | HSR trains originating from WH | ||||

| Trains from WH in | 2.430*** | – | 3.191*** | – | – | – |

| 1990 | (0.364) | – | (0.752) | – | – | – |

| Trains from WH in | – | 3.883*** | −1.528 | – | – | – |

| 1971 | – | (0.895) | (1.250) | – | – | – |

| Trains originating from | – | – | – | 1.138*** | – | 0.672 |

| WH in 1990 | – | – | – | (0.272) | – | (0.912) |

| Trains originating from | – | – | – | – | 1.864*** | 0.822 |

| WH in 1971 | – | – | – | – | (0.525) | (1.598) |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 |

| R-squared | 0.618 | 0.573 | 0.621 | 0.529 | 0.528 | 0.530 |

The dependent variable is the number of HSR trains from Wuhan or originating from Wuhan. Controlled but not listed city covariates include population, GDP, the straight-line distance to Wuhan, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the geographic coordinates of city centers, the average temperature in January 2020, and the average precipitation in January 2020. WH denotes Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A2.

More robustness checks.

| Variables | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Instrumenting HSRs from Wuhan by both IVs | |||

| No. of HSR trains from WH | 0.00751 | – | −0.00792 | – |

| (0.00661) | – | (0.00952) | – | |

| No. of HSR trains originating | – | 0.0327*** | – | 0.0941** |

| from WH | – | (0.0121) | – | (0.0374) |

| No. of normal-speed trains | 0.0113 | – | 0.0285** | – |

| from WH | (0.0121) | – | (0.0116) | – |

| No. of normal-speed trains | – | 0.114* | – | 0.0991 |

| originating from WH | – | (0.0654) | – | (0.0642) |

| No. of air flights from WH | 0.123*** | 0.113*** | 0.120*** | 0.119*** |

| (0.0218) | (0.0228) | (0.0223) | (0.0230) | |

| First-stage F statistics | – | – | 25.31 | 8.77 |

| City Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.678 | 0.689 | 0.676 | 0.687 |

The dependent variable is the logarithm form of the cumulative number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in a city by February 6, 2020. The numbers of trains from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs for the number of HSR trains from Wuhan in column (3). The numbers of trains originating from Wuhan in 1990 and 1971 are used as IVs for the number of HSR trains originating from Wuhan in column (4). The over-identification tests cannot reject the null that both IVs are valid in columns (3)-(4). Controlled but not listed city covariates include population, GDP, the straight-line distance to Wuhan, the number of medical institutions, the number of medical staff, the geographic coordinates of city centers, the average temperature in January 2020, and the average precipitation in January 2020. WH represents Wuhan. Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

References

- Anderson J.E. The gravity model. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2011;3(1):133–160. [Google Scholar]

- Avogadro N., Cattaneo M., Paleari S., Redondi R. Replacing short-medium haul intra-European flights with high-speed rail: Impact on CO2 emissions and regional accessibility. Transp. Policy. 2021;114:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baum-Snow N. Did highways cause suburbanization? Quart. J. Econ. 2007;122(2):775–805. [Google Scholar]

- Baum-Snow N., Brandt L., Henderson J.V., Turner M.A., Zhang Q. Roads, railroads, and decentralization of Chinese cities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2017;99(3):435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt A., Kato H. High-speed rails and knowledge productivity: a global perspective. Transp. Policy. 2021;101:174–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cartenì A., Cascetta F., Di Francesco L., Palermo F. Particulate matter short-term exposition, mobility trips and COVID-19 diffusion: a correlation analyses for the italian case study at urban scale. Sustainability. 2021;13(8):4553. [Google Scholar]

- Cartenì A., Di Francesco L., Henke I., Marino T.V., Falanga A. The role of public transport during the second COVID-19 wave in Italy. Sustainability. 2021;13(21):11905. [Google Scholar]

- Cartenì A., Di Francesco L., Martino M. The role of transport accessibility within the spread of the Coronavirus pandemic in Italy. Safety Sci. 2021;133:104999. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascetta E., Cartenì A., Henke I., Pagliara F. Economic growth, transport accessibility and regional equity impacts of high-speed railways in Italy: ten years ex post evaluation and future perspectives. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2020;139:412–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Xue J., Rose A.Z., Haynes K.E. The impact of high-speed rail investment on economic and environmental change in China: a dynamic CGE analysis. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2016;92:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba A. The effectiveness of mobility control, shortening of restaurants’ opening hours, and working from home on control of COVID-19 spread in Japan. Health Place. 2021;70:102622. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., Vespignani A. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticini E., Frediani B., Caro D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environ. Pollut. 2020;261:114465. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Xu M., Wang N. The industrial impact of the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed rail. Travel Behav. Soc. 2018;12:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dave D., Friedson A., Matsuzawa K., Sabia J.J., Safford S. JUE Insight: were urban cowboys enough to control COVID-19? Local shelter-in-place orders and coronavirus case growth. J. Urban Econ. 2020:103294. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2020.103294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Zheng S., Kahn M.E. The role of transportation speed in facilitating high skilled teamwork across cities. J. Urban Econ. 2020;115:103212. [Google Scholar]

- Duranton G., Turner M.A. The fundamental law of road congestion: evidence from US cities. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011;101(6):2616–2652. [Google Scholar]

- Duranton G., Turner M.A. Urban growth and transportation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2012;79(4):1407–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre D.W., Taylor D., Purver M., Chapman D., Fowler T., Pouwels K.B., Walker A.S., Peto T.E.A. Effect of Covid-19 vaccination on transmission of alpha and delta variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386(8):744–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Wang L., Yang Y. Human mobility restrictions and the spread of the novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) in china. J. Public Econ. 2020;191:104272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Zheng J. The impact of high-speed rail on innovation: An empirical test of the companion innovation hypothesis of transportation improvement with China’s manufacturing firms. World Dev. 2020;127:104838. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-López M.À., Holl A., Viladecans-Marsal E. Suburbanization and highways in Spain when the Romans and the Bourbons still shape its cities. J. Urban Econ. 2015;85:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Liu Y., Zhou L., Chen E., Liu P., Pan X., Lu Y. Epidemiological assessment of imported coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases in the most affected city outside of Hubei Province, Wenzhou, China. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(4):e206785–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley D., Li J., Wu M. High-speed railways and collaborative innovation. Regional Sci. Urban Econ. 2022;93:103717. [Google Scholar]

- He G., Pan Y., Tanaka T. The short-term impacts of covid-19 lockdown on urban air pollution in china. Nat. Sustain. 2020;3(12):1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Head, K., Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of international economics (Vol. 4, pp. 131-195). Elsevier.

- Heuermann D.F., Schmieder J.F. The effect of infrastructure on worker mobility: evidence from high-speed rail expansion in Germany. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019;19(2):335–372. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M., Wang, J., Lin, H., Ruktanonchai, C. W., Xu, C., Meng, B., ... & Lai, S. (2020). Transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 on airplanes and high-speed trains. medRxiv.

- Hu M., Lin H., Wang J., Xu C., Tatem A.J., Meng B., Zhang X., Liu Y., Wang P., Wu G., Xie H., Lai S. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 transmission in train passengers: an epidemiological and modeling study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72(4):604–610. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X., Chen H., Hong Y., Hsiao C. Do China's high-speed-rail projects promote local economy?—New evidence from a panel data approach. China Econ. Rev. 2017;44:203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M.U., Yang C.H., Gutierrez B., Wu C.H., Klein B., Pigott D.M., Scarpino S.V. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchler, T., Russel, D., Stroebel, J. (2020). The geographic spread of COVID-19 correlates with the structure of social networks as measured by Facebook (No. w26990). National Bureau of Economic Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lau H., Khosrawipour V., Kocbach P., Mikolajczyk A., Schubert J., Bania J., Khosrawipour T. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J. Travel Med. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, M., Bullock, R., Liu, Z. (2019). China's high-speed rail development. World Bank Publications.

- Li B., Ma L. JUE insight: Migration, transportation infrastructure, and the spatial transmission of COVID-19 in China. J. Urban Econ. 2021:103351. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2021.103351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Rong L., Zhang A. Assessing regional risk of COVID-19 infection from Wuhan via high-speed rail. Transp. Policy. 2021;106:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. Travel costs and urban specialization patterns: evidence from China’s high speed railway system. J. Urban Econ. 2017;98:98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Loo B.P., Tsoi K.H., Wong P.P., Lai P.C. Identification of superspreading environment under COVID-19 through human mobility data. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84089-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangrum D., Niekamp P. JUE insight: college student travel contributed to local COVID-19 spread. J. Urban Econ. 2020:103311. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2020.103311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mátyás L. Proper econometric specification of the gravity model. World Economy. 1997;20(3):363–368. [Google Scholar]

- McClymont H., Hu W. Weather variability and COVID-19 transmission: a review of recent research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(2):396. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa N., Bhatt A., Morikawa S., Kato H. High-Speed rail and the knowledge economy: evidence from Japan. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2022;159:398–416. [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L., Tang J.W., Bahnfleth W., Bluyssen P.M., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., Cao J., Dancer S., Floto A., Franchimon F., Haworth C., Hogeling J., Isaxon C., Jimenez J.L., Kurnitski J., Li Y., Loomans M., Marks G., Marr L.C., Mazzarella L., Melikov A.K., Miller S., Milton D.K., Nazaroff W., Nielsen P.V., Noakes C., Peccia J., Querol X., Sekhar C., Seppänen O., Tanabe S.-I., Tellier R., Tham K.W., Wargocki P., Wierzbicka A., Yao M. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ. Int. 2020;142:105832. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Yeh A.G.O., Zhang X. The interplay of spatial spread of COVID-19 and human mobility in the urban system of China during the Chinese New Year. Environ. Plann. B: Urban Analyt. City Sci. 2021;48(7):1955–1971. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H., Managi S. Airport risk of importation and exportation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Policy. 2020;96:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palguta J., Levínský R., Škoda S. Do elections accelerate the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Population Econ. 2021:1–44. doi: 10.1007/s00148-021-00870-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombal R., Hosegood I., Powell D. Risk of COVID-19 during air travel. Jama. 2020;324(17) doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Xiao S., Shi R., Ward M.P., Chen Y., Tu W., Su Q., Wang W., Wang X., Zhang Z. COVID-19 transmission in Mainland China is associated with temperature and humidity: a time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138778. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y., Chen X., Shi W. Impacts of social and economic factors on the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Population Econ. 2020;33(4):1127–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez D.W., Klinkhammer M.D., Rowland L.C. COVID-19 Transmission during Transportation of 1st to 12th Grade Students: experience of an Independent School in Virginia. J. School Health. 2021;91(9):678–682. doi: 10.1111/josh.13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding S.J., Turner M.A. Transportation costs and the spatial organization of economic activity. Handb. Regional Urban Econ. 2015;5:1339–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi M.M., Habibzadeh P., Vintzileos A., Shokouhi S., Miralles-Wilhelm F., Amoroso A. Temperature, humidity, and latitude analysis to estimate potential spread and seasonality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(6):e2011834–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Dong Y., Yan H., Zhao C., Li X., Liu W., He M., Tang S., Xi S. Impact of temperature on the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138890. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde V., Bhikha S., Hoosain Z., Archary M., Bhorat Q., Fairlie L., Lalloo U., Masilela M.S.L., Moodley D., Hanley S., Fouche L., Louw C., Tameris M., Singh N., Goga A., Dheda K., Grobbelaar C., Kruger G., Carrim-Ganey N., Baillie V., de Oliveira T., Lombard Koen A., Lombaard J.J., Mngqibisa R., Bhorat A.E., Benadé G., Lalloo N., Pitsi A., Vollgraaff P.-L., Luabeya A., Esmail A., Petrick F.G., Oommen-Jose A., Foulkes S., Ahmed K., Thombrayil A., Fries L., Cloney-Clark S., Zhu M., Bennett C., Albert G., Faust E., Plested J.S., Robertson A., Neal S., Cho I., Glenn G.M., Dubovsky F., Madhi S.A. Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine against the B. 1.351 variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384(20):1899–1909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M.M., Mohammadi N., Taylor J.E. Investigating the association between mass transit adoption and COVID-19 infections in US metropolitan areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;811:152284. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.J., Moreira E.D., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Perez J.L., Pérez Marc G., Polack F.P., Zerbini C., Bailey R., Swanson K.A., Xu X., Roychoudhury S., Koury K., Bouguermouh S., Kalina W.V., Cooper D., Frenck R.W., Hammitt L.L., Türeci Ö., Nell H., Schaefer A., Ünal S., Yang Q.i., Liberator P., Tresnan D.B., Mather S., Dormitzer P.R., Şahin U., Gruber W.C., Jansen K.U. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine through 6 months. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385(19):1761–1773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Liu Y., Li Y., Wu C.H., Chen B., Kraemer M.U., Dye C. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6491):638–642. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosepu R., Gunawan J., Effendy D.S., Ahmad L.O.A.I., Lestari H., Bahar H., Asfian P. Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;725:138436. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.u., Jing W., Liu J., Ma Q., Yuan J., Wang Y., Du M., Liu M. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139051. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Lin F., Tang Y., Zhong C. High-speed railway to success? The effects of high-speed rail connection on regional economic development in China. J. Regional Sci. 2019;59(4):723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Wan Y., Yang H. Impacts of high-speed rail on airlines, airports and regional economies: a survey of recent research. Transp. Policy. 2019;81:A1–A19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang A., Wang J. Exploring the roles of high-speed train, air and coach services in the spread of COVID-19 in China. Transp. Policy. 2020;94:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng R., Xu Y., Wang W., Ning G., Bi Y. Spatial transmission of COVID-19 via public and private transportation in China. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;34:101626. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P., Guo Y. The role of high-speed rail and air travel in the spread of COVID-19 in China. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;42:102097. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]