Abstract

By early 2021, The World Bank was indicating that the massive COVID-19 induced declines in remittance flows it had predicted in the previous year had not materialised; actual declines were smaller and shorter term than expected. In some cases like that for Zimbabwe, there were significant increases. It argued that coronavirus pandemic lock down policies led to a shift from use of informal to formal recorded money transfer channels. However, given the diversity of contexts in source and receiving countries, there is need for continued localised investigations to understand the nature and development policy implications of these flows. Focusing on remittances sent by Zimbabweans settled in the UK (diaspora) during COVID-19 pandemic year, this paper draws on survey data to explore increases in the remittance flows, nature of, motivations for and purposes of remittances. Crucially it examines how the diaspora managed to increase the remittances when they were under immense financial pressure themselves. It confirms and contributes to understanding of the countercyclical nature of remittance flows.

Keywords: Remittances, COVID-19, Diaspora, Migrants, Zimbabwe

1. Introduction: From narrative of plummeting to “defiant” remittances during COVID-19

Remittances that ‘migrants’send to their countries of origin in the form of finance, goods, information and services are critical for livelihoods (Bracking & Sachikonye, 2006), education, health, agricultural investments, economic growth and sustainable development (Mercer, 2008, Mukwedeya, 2012, Pharaoh & McKenzie, 2013, United Nations, 2021). For Africa, remittances are more ‘reliable’ and far exceed foreign direct investment (FDI) and have exceeded foreign Oversees Development Assistance (ODA) since 2000–2005 (ODI, 2007, Mukwedeya, 2012: 43; Ratha et al., 2020: 8). However, significant proportions of these transfers are lost in intermediation because of high charges (ODI, 2014, Esser and Cooper, 2020) while socio-economic crises or shocks can affect the transfers (ODI, 2007, The World Bank, 2020). In the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, The World Bank (2020: 1) predicted that the economic crisis induced by the pandemic and shutdown policies would lead to an unprecedented 20 % decline in global remittances to low and middle income countries. Sub-Sahara Africa would experience a sharper 23 % decline (Bisong et al., 2020, Kalantaryan and McMahon, 2020: 5–6) especially for transfers to conflict affected countries and fragile economies, countries with low remittance diversity indices and countries where remittances contribute at least 10 % of GDP (Kalantaryan & McMahon, 2020: 9–12).

Even the revised briefings of late November 2020, were that “remittances flows to low and middle income countries [would] decline by 7.2 % to $508 billion in 2020 followed by a further decline of 7.5 % to $470 billion in 2021” (Ratha et al., 2020: vii). These projected declines would be much higher than the 5.5 % (The World Bank, 2011: x) registered during the last major global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Factors leading to the projected declines would include weak economic growth, unemployment and uncertainties around jobs in migrant hosting countries (e.g. in Europe, USA, China and Gulf Cooperating Countries) weak oil prices, unfavourable exchange rate against the US$ in remittance source countries (Ratha et al., 2020: vii; The World Bank, 2021a: xi) and migrants returning home (Financial Express, 2021). Given the knowledge influence of The World Bank, the narrative of decline was dominant in 2020.

However, by May 2021, it had become clear that the actual 2020 decline in global remittances was at most a paltry 1.6 % below the volumes sent in 2019, and that excluding China, they far exceeded foreign direct investment (The World Bank, 2021a: x). Furthermore, diversity was prevalent across sending and receiving countries. For instance while the flows to Europe and Central Asia declined by 9.7 %; increases were registered for Latin America (+6.5 %), East Asia and the Pacific (+7.9 %), Middle East and North Africa (+2.3 %) and Sub-Sahara Africa + 12.5 % (ibid.). In contrast, during the 2008/2009 global financial crisis, remittances to developing countries fell 5.5 % while FDI dropped by 40 % (The World Bank, 2011: x). To explain the stability and increases in remittance flows during the COVID-19 pandemic, several factors have been suggested. First was the shift from informal unregistered to digital and formal channels of transfer (The World Bank, 2021a, Unit, 2021) in a context where lockdowns reduced movement of people and goods to a minimum. Second were the host country policies that were inclusive and offered migrants the same welfare support and vaccinations as offered to natives thus enabling them to continue working. Thirdly, the fiscal stimuli adopted in many developed countries ensured economic stability and limited job loss thus leading to a not so drastic reduction in the capacity of migrants to send remittances.

Given that the above patterns are global, there is need to unravel the local level remittance dynamics in both sending and receiving communities and approach remittances in a way that recognises regional and geographical complexity (Nyamunda, 2014, McGregor and Pasura, 2014). For instance, the switch to digital transfer channels had negative effects for communities with limited internet access and banking services such as in Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali (Kalantaryan & McMahon, 2020: 27). Mukwedeya (2012) confirmed that at the peak of Zimbabwe’s economic crisis (2006–2008), remittances to Zimbabwe’s low income areas of Harare were mainly ‘in- kind’ compared to cash transfers from the USA and the UK. In the UK, Black and ethnic minorities are also disproportionately represented in ‘shut down sectors of the economy’; the sectors closed during the initial phase of lockdowns such as transport and tourism, hotel, catering services, gym and leisure where they are typically low paid and more likely to lose their jobs (IFS, 2020; HC, 202:21–23).

Where the host governments have no capacity to provide welfare to all, such as in South Africa or where the migrants are undocumented (including in the UK), the capacity to send remittances would have been severely dented. Kalantaryna & Mohan (2020: 8) report that during the 2014–15 Ebola crisis, remittance inflows increased for Liberia and Guinea but remained flat for Sierra Leone. Country differences in remittance inflows were also observed for 2012 MERS crisis in Asia. While data on remittances is not reliable, the countercyclical nature of remittances needs continued investigation. The impact of COVID-19 at the local level and how the affected communities respond to their circumstances is thus an area for further interrogation.

In Fig. 1 , for instance, this entails asking why there was noticeable decline in remittances to Lesotho, The DRC and South Africa but a sharp increase in the case of Zimbabwe. The diversity of remittances and events in the sending countries and channels of transmission have to be analysed in detail. For instance, Lesotho depends on remittances from South Africa and has a Remittances Diversity Index1 of less than 0.1 (Kalantaryan & McMahon, 2020: 13). South Africa’s economy was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic and welfare support to migrants was non-existent. Thus, migrants in South Africa (including the large Zimbabwean diaspora) would have struggled to support themselves and send money back home. However, Zimbabwe has a Remittances Diversity Index of close to 0.8 (Kalantaryan & McMahon, 2020). This means that it has a wide range of source countries for its remittances: a collapse in one would likely not lead to a major decline. However, this and the switch to formal channels does not fully explain the sharp remittance inflow increases in 2020–2021; the actual experiences need deeper investigation.

Fig. 1.

Inflows of Remittances to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Region − 2008 − 2021Source: Original data extracted from The World Bank (2021b), Remittances and Migration Data (US$ '000).

This paper illustrates the necessity to understand dynamics in specific remittance corridors during COVID-19 and has broader implications on diaspora, remittances, livelihoods and development literature. However, except for a few points and to avoid going on a tangent, the concept of diaspora (e.g. Safran, 1991, Tololyan, 1991, Hear, 1998, Vertovic and Cohen, 1999) and as debated in the Zimbabwean context (e.g. Mbiba, 2005, Mbiba, 2011, Mbiba, 2012b, Mbiba, 2012, McGregor, 2007, Pasura, 2010, McGregor and Primorac, 2010, McGregor and Pasura, 2014, Chiumbu and Musemwa, 2012, Nyamunda, 2014) will not be discussed here. First, using the ‘outsider’ versus ‘insider’ notion of diaspora dominant among ordinary Zimbabweans (McGregor, 2010a) diaspora are those Zimbabweans living outside the country: as migrants, refugees, asylum seekers or exiles, settled citizens and those born to such Zimbabweans (the neo diaspora) and continue to live outside the country and who maintain transnational linkages with the country of origin. Second, there is a ‘near diaspora’ in Zimbabwe’s neighbouring countries especially South Africa and Botswana and a ‘far diaspora’ especially in the UK, Europe, North America, China, Australia and New Zealand. Consequently, Zimbabwe’s diaspora is variegated and fractured (McGregor and Primorac, 2010, Mbiba, 2012, Pasura, 2014) by history, origin and destination regions, original push factors, race, class, gender, ethnicity, identity, cultures and dynamics of transnationalism.

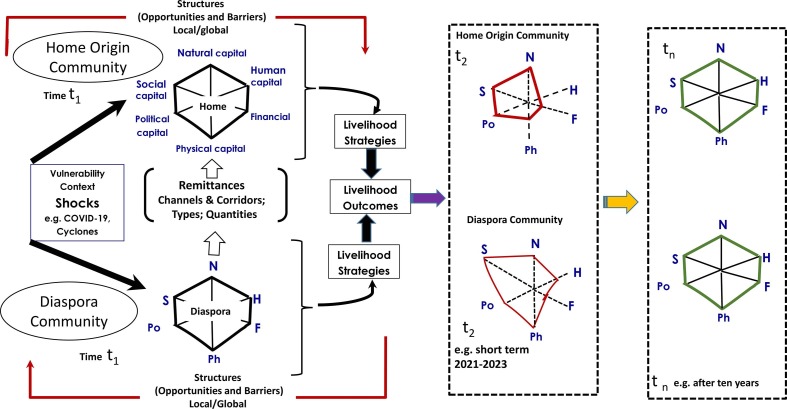

Furthermore, central to remittances are the poverty reduction, livelihoods and development impacts that they engender (Bracking & Sachikonye, 2006). Individuals, households and communities or entities (in the diaspora and at home) work to boost their assets/capitals such as human, physical, social, political and financial capital (Rakodi and Lloyd-Jones, 2002, Scoones & Wolmer, 2003) (see relations sketched in Fig. 2 ). Within given structural contexts (e.g. political economy, government policy, climate, gender, patriarchy) assets/capitals determine the capacity of entities to withstand shocks, to exploit opportunities and to construct complex livelihoods portfolios (Rakodi and Lloyd-Jones, 2002, Scoones & Wolmer, 2003) both in the diaspora (Mbiba, 2011, Mbiba, 2012b) and home community (Bracking and Sachikonye, 2006, Mukwedeya, 2012, Nyamunda, 2014). As implied in Fig. 2, and depending on context as well as the nature and duration of shocks, some capitals may shrink in the short term. Remittances help to stabilise, replenish and enhance assets and livelihoods of recipients.

Fig. 2.

COVID −19, Diaspora Remittances and Sustainable Livelihoods- Conceptual Apparatus.

However, there are other possibilities. For instance, sending remittances to stabilise livelihoods and assets of recipients (see Mukwedeya, 2012, Nyamunda, 2014) may erode the assets of the diaspora; leaving the sender vulnerable to future shocks. The hope is that in the long term (time tn in Fig. 2), the assets will be restored and enhanced relative to their status in earlier periods (time t1, t2). While the critique of this paper is on the need to understand implications of diversity of diaspora and remittance corridors on remittances sent during COVID-19, Fig. 2 is a sensitising device to connect emerging and comparative discussions and further case studies. Resources permitting, the diaspora and home community space, the corridors, the structure-agency relations all need time-series examination that was not focus of this paper.

2. Research questions and objectives

Zimbabwe registered an increase in formal remittance inflows during the COVID-19 year (2020–2021) of over US$ 1bn (RBZ, 2021, The World Bank, 2021a; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021) compared to the same period in 2019 (US$636 million). The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021: 1) suggested that this surge in remittance inflows:

… could be a result of many Zimbabweans in nearby South Africa, Malawi and Botswana, shifting to formal money-transfer channels owing to the effect of COVID-19 pandemic as travel across international borders was curtailed for much of 2020.

The closure of borders made it difficult to send funds through informal cross border options (the ‘Malayitsha’ systems) (see e.g. Nyamunda, 2014). However, border closures increased illegal crossings (along the porous Zimbabwe-South Africa boundary) and smuggling of goods (Africanews, 2020, Financial Mail, 2020). Police and soldiers mandated to protect the borders instead are involved and receive bribes “colloquially termed toll-gate fees” to facilitate the illegal movement of large amounts of goods (The Chronicle, 2021). All this has increased the risks and costs of informal trade on which Zimbabwe depends.

When it comes to financial remittances, the closure of borders and switch to formal channels explanation does not cover those in the USA and Europe for example who traditionally had limited options for use of cross border channels and are more likely to have always used more of the formal bank and money transfer operators. Beyond the change in transmission channels (The World Bank, 2021a; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021), there is need to investigate whether such diaspora sent more money than usual. Zimbabwe has a significant diaspora in the United Kingdom with the majority arriving in the 1999–2006 period. The Zimbabwean born population in the UK is now the third largest African population (ONS, 2019, Mbiba et al., 2020: 2) and has significant presence in the health and care sectors (McGregor, 2007, Mbiba et al., 2020).

This study investigates the patterns of cash remittances sent to Zimbabwe from the UK during the COVID-19 year (March 2020 – April 2021); whether individuals sent more money than in previous years, the motivations and purposes for which the remittances were sent. Black Africans in the UK were among the highest at risk of poverty and most likely to be infected by the coronavirus and to experience unemployment, loss of income or suffer financial stress (IFS, 2020: HC, 2020, Hu, 2021). Nevertheless, Pharoah and McKenzie (2013: 7) concluded that they were more likely to send money overseas even when they were under crisis conditions. Therefore, crucially, the study explores the sacrifices and adjustments that the UK diaspora had to make in order to send remittances under the stressful COVID-19 conditions.

3. In the field: Research design and methods

The data used in this paper was extracted from a study whose objective was to deepen understanding of the COVID-19 impacts, including on transnational relations, among Zimbabweans in the UK. Data was collected using an online survey, four one-hour zoom focus group discussions (FGs)2 and literature review. Although social media (Facebook and WhatsApp groups) are reservoirs of significant testimonies and information on impacts of COVID-19 among Zimbabweans, there are ethical issues relating to use of this information for research without the permission of each individual participant or contributor. To recruit participants, the study used information from LinkedIn, publicly available lists of participants to seminars or events and websites of organisations to build an email list of the target population. In addition, community and civil society leaders were invited to circulate the research flyer among their membership. The flyer was also posted at three shops patronised by Zimbabweans: an ethnic food shop in Central England, a hair salon and a vehicle repair shop both in the Thames Valley region. The flyer provided links to further information about the study and what volunteers needed to do to participate in the online survey and focus group discussions.

Emailed invitations to participate in the study were sent to two hundred individuals. From all these initiatives, there were eighty online survey responses of which fifty were valid with the rest either opt outs or incomplete and unusable. The online survey was created and managed using QUALTRICS software. QUALTRICS enabled sending of reminders and ‘thank you messages’ to participants at the end. The survey was left open for forty days in July- August 2021. To participate in the study, respondents had to confirm that they understood the study information, were Zimbabwean diaspora, aged 18 years and above, that their participation was voluntary and had been in the UK for at least six months before March 2020.

The study did not request any personal data. However, those opting to share their experiences in the focus group discussions were offered the opportunity to give an email contact at the end of the online survey. Nine participants opted into the FGs from using this method. To recruit more focus group participants, two community leaders, one from South East England and another from West England invited the study team to explain the study to their membership instead of just distributing the flyer. A one-hour session was held with each group on zoom at the end of July during which participants enrolled anonymously and asked questions. From these talks, eight participants either opted to participate in the FGs or offered to have an in-depth interview or both.

During the recruitment talks, it was clear that participants needed to build trust. In one of the sessions, they needed to understand why a “non-Zimbabwean’, ‘a Kenyan’ a ‘Cameroonian’” was conducting a survey on Zimbabweans. The study coincided with the episode when the UK Home Office was preparing to enforce deportations of Zimbabweans deemed undesirable in the UK. These deportations were done with the agreement of the Zimbabwe government and generated anger and anxiety among some Zimbabweans. Unsurprisingly, in these circumstances, any surveys were viewed with suspicion by sections of the community; the study could be covert operations of the two governments (McGregor, 2010b: 136–137). The talks helped to reduce anxieties.

The COVID-19 pandemic generated ongoing traumatic experiences in different ways among the community (Mbiba et al., 2020). The focus group discussions had the potential to exacerbate anxieties and distress among some participants. The study developed support pathways for individuals in distress and provided this information to participants before the start of deliberations. An experienced mental health support worker was also present at every discussion to help identify and offer immediate support to any participant in distress. A board chaired by an experienced medical practitioner was also constituted and on standby for consultation in the unlikely event that a study participant showed signs of acute distress or needed further support.3

Descriptive statistics of responses to pre-coded questions were produced automatically by the QUALTRICS software and are used to present profiles of respondents presented in the results section. Recordings from the FGs were transcribed and Nvivo software was used for content and thematic analysis of the textual material. This entailed searching for key terms (derived from literature review), interpretation and coding of statements to identify emerging and recurring themes. Main elements of this analysis will be subject of a separate paper.

4. Results and discussions: diasporic connections for development during Covid-19

4.1. Features of the survey respondents: Still in employment during and after COVID-19

There are about 130 000 Zimbabwean born citizens in the UK (ONS, 2019) and thousands more who were born in the UK: the latter can be described as the ‘neodiaspora’. The respondents to the online survey all identified themselves as ‘Zimbabwean born’. Seventy-eight percent (78 %) indicated that they were/are naturalised British citizens. The majority of respondents (66 %) left Zimbabwe for the UK in the period 2000 and 2004. This aligns with the period of rapid arrivals of foreign born nationals to the UK (2000 – 2009) (ONS, 2013, DMA, 2015: 4). They were largely in the 36 to 65 year age group (64 %) and drawn mainly from urban regions of Harare Province (30 %) and Bulawayo Province (24 %) with Manicaland Province (14 %) and Midlands Province (10 %) the notable contributions. These patterns are similar to those from another survey on health and care workers conducted in mid-2020 (Mbiba et al., 2020) where negligible proportions of respondents were recorded from the two Matabeleland Provinces and Masvingo.

At the start of COVID-19 in March 2020, 67 % of the respondents were employees while three percent were self-employed (with no employees), 14 % operated as agency workers and six percent were running businesses that had employees. Thus in total, up to 23 % of respondents were in the categories likely to be at the back of the queue to receive state support (Duke, 2020: 115). In the initial lockdown, nurses working as agency staff presented testimonies at community online forums (Mbiba et al., 2020) pointing to complex eligibility criteria and lack of awareness of the available state support systems on the part of both workers and managers.

Thirty-five percent of the participants described themselves as nurses, 14 % as pharmacists, 5.4 % as occupational health therapists, 11 % unemployed and 18 % working in other professions such as finance, surveying, local government and information management. The proportion of nurses in this survey was lower than the 63 % in the 2020 survey (Mbiba, et al., 2020) that had targeted health professionals. About 11 % of those who were employees at the start of COVID-19 year, had changed their employer or changed their main job over the year. Crucially, at least 94 % of respondents who were employed in March 2020 were still employed at the end of the COVID-19 year in April 2021. Their capacity to send remittances would not have been as compromised as that of the 23 % in insecure employment or contracts.

4.2. Zimbabwean remittances “soaring” during the COVID-19 year.

The rise in volumes of remittances to Zimbabwe seem to have taken most experts by surprise. Based on The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ: 2021: 31) data, after a decline in March and April 2020, official inflows of remittances increased by 57 % from US$635.7 million in 2019 to US$1.0 billion in 2020. For the RBZ, 2021: 31), the increases were “… mainly due to liberalisation of the use of free funds in the country and improved channelling of remittances through formal channels”. These figures have informed subsequent comment in the media and reports of international development organisations such as The World Bank (2021: 31) and the Economist Intelligence Unit (2021).

However, beyond the increased use of formal channels to send remittances, there is also the possibility of other factors including increases in actual amounts sent by diaspora during COVID-19. Diaspora faced significant financial insecurity and risk of unemployment (Hu, 2021) while lockdowns restricted international cross-border travel for seasonal migrant workers in the Zimbabwe-South Africa corridor. Nevertheless, these factors would differ from one remittances channel to another (DMA, 2015). For instance cross-border travel and use of informal channels would have been a more pronounced factor for the South Africa to Zimbabwe corridor and less so for the UK-Zimbabwe or USA-Zimbabwe channels. Given Zimbabwe’s relatively high Remittance Diversity Index (of 0.76) (Kalantaryan and McMahon, 2020, Eu, 2020, Kalantaryna, 2021) there is need to interrogate how COVID-19 affected remittances in different remittance corridors. This focus on the UK-Zimbabwe corridor is an initial start in that direction.

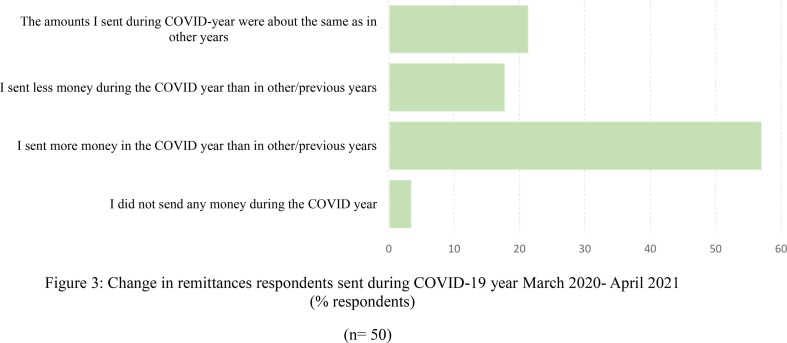

Respondents to the online study were asked to indicate whether there was any change in the amounts of money they sent to Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 year relative to previous years. Fig. 3 shows that the majority of respondents (57 %) reported having sent more money while 18 % sent less money than in previous years. This contrasts with rural Kenya (Janssens, 2021: 1) where in the short term, households ‘gave out less gifts and remittances”.

Fig. 3.

Change in remittances respondents sent during COVID-19 year March 2020- April 2021 (% respondents) (n = 50).

There is thus a real possibility that the diaspora dug deeper into their pockets to send more money to those in Zimbawe. The bulk of the cash remittances were sent through World Remit (43 %), Western Union (29 %), Mukuru.com (7 %) and via Bank to Bank transfers (7 %). This is in sharp contrast to the first decade of the millenium when families in Zimbabwe recived as much as 58 % of transfers via informal channels (Bracking & Sachikonye, 2006: 32). Notable as well in the responses was that no transfers were made using either ‘hand couriers’ or ‘barter exchanges that were dominant before 2010 (Bracking & Sachikonye, 2006). Low proportions sending cash to an account or cash in hand were also observed for other UK based diaspora (DMA, 2015). Barter exchanges are scenarios where a member of the diaspora requests someone in Zimbabwe to provide a service or goods with the payment made into a foreign account (see next section for diversity in sending goods). This was a feature during the era of hyperinflation (Gono, 2008) when those in Zimbabwe would seek to retain value of their earnings by keeping savings out of the country and shunning formal banking systems. Therefore unlike the cash remittances from South Africa that have signficant use of informal channels (Bracking and Sachikonye, 2006, Nyamunda, 2014), use of formal Money Transfer Operators dominates transfers in the UK-Zimbabwe corridor.

However, with use of free funds policy (RBZ, 2021: 31) in the country, the need for barter transactions has diminished. A large disparity between official exchange rates and the black market rates is a huge incentive for remitters to use informal channels (ODI, 2007). But over the year 2020, Zimbabwe’s headline inflation had reduced from a peak of 837.5 % in July 2020 to 326.6 % in January 2021 (RBZ, 2021: 23). Over the same period exchange rates had been stable and the parallel market premium had reduced to a tolerable band of up to 20 % (RBZ, 2021: 8). These were shifts towards conditions more favourable to use of formal channels for sending cash remittances. Thus the structural conditions in the home country (Fig. 2) had an influence on the mode of sending remittances. The story is however incomplete without considering the motivations or purposes for which the remittances where sent and why.

4.3. Remittances sustaining the Zimbabwean health system

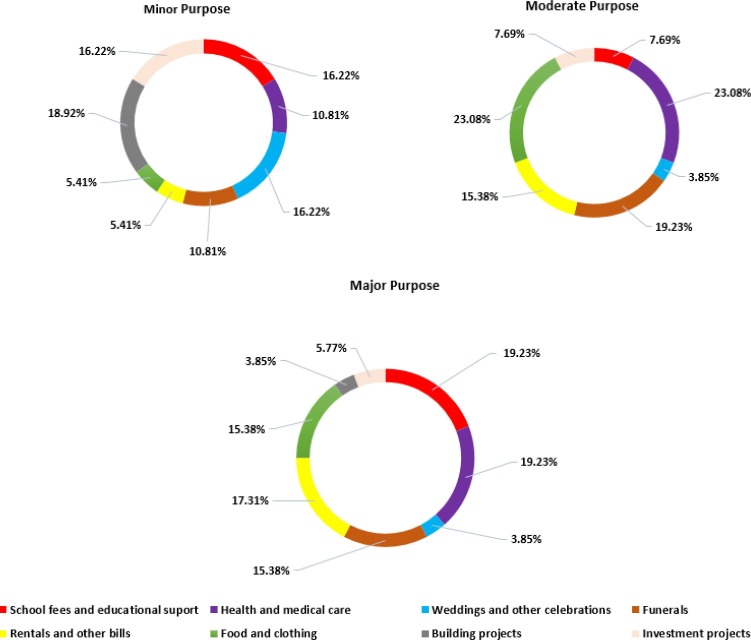

Respondents to the survey indicated that they sent money to a wide range of recipients but mainly to family (58 %), to friends (25 %) and community (8 %) (Fig. 4 ). The major purposes for these remittances were largely to address health and care issues (19.23 %), school fees and education related support (19.23 %), funerals (15.38 %) and food and clothing (15.38 %). Health, education and food are key basic needs at the core of sustainable development goals. As revealed in recipient community based studies (Bracking and Sachikonye, 2006, Mukwedeya, 2012), the channelling of remittances to sustain livelihoods remains a dominant phenomenon. Diaspora remittances also pay for investment in income generating projects and are channelled to government and community recipients in the form of collective contributions (AUC/CIDO, 2021).

Fig. 4.

Purposes for which respondents sent remittances to Zimbabwe: from the minor to major.

Crucially, the survey results confirm that in addition to family livelihoods and investments, remittances also pay for things that government and ODA will not pay for: namely dignity and the sense of being a human being in the form of payments for funerals. As during the HIV/Aids pandemic, households would spend as much as they could to keep their loved ones alive even where medical indicators pointed to little chance of survival. Moreover, the expenditures would continue after death. The view that “there is no sense or value of living if one cannot provide end of life care and decent burial to loved ones” was a recurring theme in the focus group discussions. Cash remittances from ‘children abroad’ (the diaspora) have contributed to the transformation of Zimbabwean ‘mourning and funeral’ rituals. As Chadya (2013: 141) observed from an ethnographic study of Zimbabweans in Canada, the impact of remittances is such that “… funeral paraphernalia – funeral food, dressing and etiquette, the kind of casket one is buried in and the use of funeral homes for burial …” that used to be a preserve of privileged economic and political elites are now prevalent. At the same time, gender and patriarchy dynamics have been truncated as power has shifted to younger and female diaspora sending remittances (Chadya, 2013: 155).

Higher levels of remittances were also paid for health care due to what a respondent called the ‘crazy situation in Zimbabwe’ where everything is informal and never under one roof.

Even the doctors’ services are secured informally, after paying for the doctor, you run around to secure the equipment, you need oxygen and you have to get it informally, you need the antibiotics, any tests to be done, you use informal means to secure them. And all providers know that there is diaspora support so they charge anything really… crazy situation” (Respondent Muvhuni, Liverpool).4

With a collapsed public health sector, private hospitals were charging a daily admission fee of US$800 – US$1000 per day for a COVID-19 bed: well beyond the reach of the majority (Sunday Mail, 2021).

A couple of reflections from the focus groups on the ‘crazy situation’ above are apt. First, informality is now ubiquitous including in the remittances sector (Bracking and Sachikonye, 2006, Mukwedeya, 2012, Chadya, 2013, Nyamunda, 2014). Even the state itself has informalised in order to sustain itself (see Mbiba, 2022). Second, as a health emergency, COVID-19 illnesses forced diaspora to send cash immediately. Third and crucially, the nature of the illness and the lockdown policies closed the option for diaspora relatives to transfer COVID-19 patients to better facilities in South Africa or India, as is increasingly the trend. Consequently, diaspora had to send cash to Zimbabwe and hope something positive would work out.

A recurring feature of these remittances is that they address poverty and well-being in ways that governments and donors do not do: they are direct, immediate and highly responsive to local needs and changing circumstances at the household level. According to Mrs Makomo, COVID-19 affected diaspora remittances in other ways and were sent:

“… because there was a huge rise in family members asking for financial support, who, pre-COVID-19 would not ask for support. The support was mainly-one-off; paying school fees, examination fees and food parcels for our elderly family members” (Survey response, 2021).

There was a broadening of the people to whom remittances needed to be sent. The one off money sent for tuition fees and examination fees reinforces the perception that investment in education remains highly valued among Zimbabweans (see also Mukwedeya, 2012.

Nevertheless, if food is added, survey results show that the health sector was the dominant recipient of remittances from the UK during COVID-19. Having enough food is critical for health and well-being of communities. However, during initial lock downs, even those with money could not go out to purchase food in some urban settings. Only security forces personnel and individuals in approved sectors would be permitted to pass through the lockdown roadblocks. Some of the security officers became ‘couriers of goods’ during the crisis as MaKhumalo explained:

I have friends and neighbours who work in the police. They were among the few able to travel around in Bulawayo at the time. We organised that they deliver groceries to our families… they were doing door-to-door service. They were paid on delivery or at times before, depending on the circumstances… everything was arranged on the phone and based on trust. Many people survived this way (Respondent MaKhumalo, July 2021).

The informal ‘couriers’ role of police and other government officers during COVID-19 mirrors that of illegal cross-border crossing and smuggling of goods on the Zimbabwe - South African border (Nyamunda, 2014: 40; Africanews, 2020; The Chronicle, 2021). The survival challenges these government officers face (d) are/were the same as those faced by the rest of society; hence, they were/are sympathetic. They also use/d the opportunity to earn extra income in forex.

Moreover, survey data reveals that those who needed support were not only in Zimbabwe. Thirty-seven percent of online survey respondents reported sending money to South Africa. In 2020, Zimbabweans in South Africa were hit hard by COVID-19 with many of those dependent on informal economy jobs not able to earn an income due to lockdowns and faced challenges to pay rents and to buy food. If the Zimbabwe diaspora sent more money during COVID-19 than in previous years, there is need to examine how they managed to do it given the pressures that they faced as well.

4.4. Capabilities to send remittances: The sources and adjustments

As summarised earlier, the overwhelming majority of respondents remained employed during the COVID-19 year and were thus able to continue sending remittances and sending even more than before. The literature points to higher risk of jobs loss among Africans during COVID-19 (IFS, 2020, Parliament, 2021, Hu, 2021). However, the respondents in the survey were dominated by health workers and professionals outside the shutdown sectors. Health care was a service in great demand while most professional jobs in finance, management and information could be conducted remotely from home. Thus, those who did not fall ill were likely to have continued working during COVID-19.

At the same time, the UK government welfare support system would be available to most of the respondents given that they were naturalised citizens. However, an Agency worker who was infected by the coronavirus reported that:

… The COVID self-isolation payment of £500 was denied by my local council. I then wrote my local MP for support and the council decision was overturned. I think COVID victims must have financial support … it has left many incapacitated (Online Survey Respondent July 2021).

This response points to a real possibility that some of those who were eligible for support had difficulties accessing it due to lack of awareness, lack of information or improper interpretation of policy on the part of officials.

But as indicated by Debra, many in employment especially nursing and health care were also able to access loans:

A time bomb will explode in two or so years. Many of us got these loans, up to ten thousand pounds for example. You had to do it to buy medication for parents or siblings struggling at home… Not sending money was not an option. However, if one is not able to pay in the coming two years and if cost of living goes up, then there will be problems. One will have to put in extra shifts to earn the money (Focus Group discussion, 2021).

Thus, those sending remittances are left with depleted assets and vulnerable to future or persistent shocks (See Fig. 2, time t2).

In the 2020 community zooms meetings (Mbiba et al., 2020) some participants advised others not to overwork themselves, to eat well and have a balanced healthy life. However, 49 % of survey respondents indicated working well over eight hours a day. Working long hours could arise for a variety of reasons beyond the need to send money home. Those in insecure jobs (agency staff, self-employed and zero hour contracts) worked as many hours as they could as there was no guarantee that they would get work the following day. At the launch of a Migrants’ Rights Network (2020) report, a security guard reported that guards risked not getting work if they demanded to work only for the statutorily prescribed hours as they would be replaced easily in a context where more people were looking for jobs. The report highlights how COVID-19 heightened the invisible workplace racism and structural inequalities affecting migrants. In the health and social care sector, working hours were also long due to high demand during the COVID-19 pandemic. These diasporic struggles for rights in the host country are juxtaposed with diasporic political activism in the home country (Mutambasere, 2022).

A respondent enrolling herself as Muroora R (daughter in law R) indicated that many in her circles resorted to “Food Banks” and collected free food humpers offered by large supermarkets.

Instead of buying pasta, cereals, baked beans and so on, every week we collect these dry food items at the large shops… just go into ASDA or TESCO, shoppers drop these in the boxes and the shops add some more. The thirty pounds I would normally use to buy these items every week… when I send it …it means a lot to those back home. There is nothing to be ashamed of… (Respondent Muroora, R. July 2021).

This testimony, corroborated in FGs, points to adjustments that some in the UK diaspora had to make in order to send more money home. Discussants observed that COVID-19 had normalised use of Food Banks that in the past would have been a source of shame among Zimbabweans (see similarities with work in ‘dirty, demeaning and dangerous jobs’ Mbiba, 2005, McGregor, 2007).

Use of Food Banks would have helped many destitute people to survive and others to make savings on grocery costs. Remote working (Deloitte, 2020) also helped those in work to make savings for example the cost of commuting was reduced significantly enabling individuals to send a bit more in remittances. Those who fell ill or were self-isolating had access to state support although success in accessing this support seems to have been better in large metropolitan areas than in rural settings and small towns (Focus Group discussions, 9th August 2021). From the online survey, 47 % respondents indicated that they did not need to apply for Statutory Sick Pay or that it was not applicable to them (34 %) while 19 % had made successful applications. The support they received ranged from three days to four months. Consequently, individuals would have access to food even if they had challenges paying for rent and sending remittances to Zimbabwe. Broadly, diaspora coping mechanisms were similar to those of rural households (Gupta et al., 2020, Janssens et al., 2021).

In line with (Duke, 2020) focus group discussions also revealed that Zimbabweans in the UK participated in mutual aid social formations that sprung up to support the vulnerable during COVID-19. These were involved in sourcing food, delivering prescription medications and ‘soup kitchens’. Mutual aid included online social ‘friends and talking groups’ that helped people keep in touch during self-isolation. Church based groups were critical in these mental health and emotional support activities. Thus, the strengths and role of social capital (in Fig. 2) during COVID-19 emerged as a major phenomenon even though it can be under stress (see also McGregor, 2010a, b) or not available at all times (Chadya, 2013).

4.5. Diasporic connections for development: From individual to collectives

The remittances narrative presented in this paper has focussed on individual giving during what is arguably an ‘emergency situation’. In that sense, these remittances can be considered humanitarian emergency giving (AUC/CIDO, 2021). It is this ‘urgency’ that explains why remitters had to do as much as they could at short notice. However, assuming the emergency becomes protracted, as was likely with COVID-19, or a new crisis unfolds as has happened with economic impacts of the war in Ukraine, then some remitters may find their capacity to give completely eroded and assets failing to recover (scenario of time t2 Fig. 2). If two family members needed COVID-19 hospital care in Zimbabwe at the same time for just one week, then even diaspora support would buckle. The duration and intensity of the shock is critical in how long the diaspora can continue giving meaningful support to their family and friends in the country of origin.

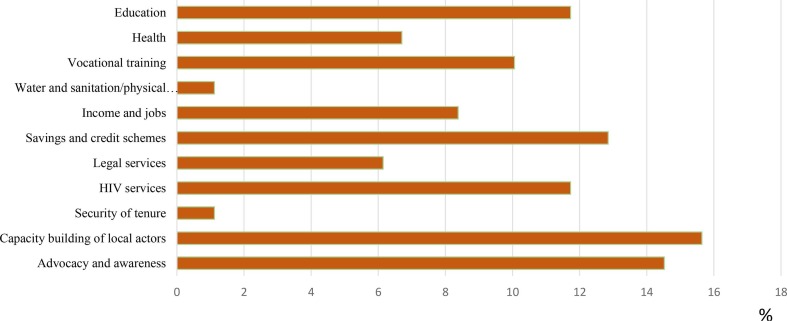

Beyond the individual giving there is also community and collective giving which was not explored in the study for this paper. Such giving tends to focus on organisations and communities in the home countries. In traditional development (Mercer, et al., 2008), diaspora civil society organisations support initiatives in a range of sectors including education and health. Fig. 5 gives a summary of how the UK based diaspora used the financial support received from COMIC Relief in the 1998 to 2008 decade. Awareness raising/advocacy and capacity building are significant features of collective initiatives that are not possible at the individual level. COVID-19 induced lock downs and border closures made in difficult for diasporic organisations and individual to travel for development work in their countries of origin. Face to face mobilisation was also curtailed and sending of goods was affected.

Fig. 5.

From basic needs to rights: Comic Relief funded diaspora activities (1998–2008) Source: Compiled by B. Mbiba from Comic Relief Project Files, 2013. (n = 50).

Consequently, like in the individual remitting of funds, diaspora groups switched to online platforms for mobilisation and connections with home. Knowledge exchange, awareness and capacity building (AUC/CIDO, 2021) dominated these online exchanges. These were targeted both at the country of origin as well as the diaspora itself (Mbiba et al., 2020, AUC/CIDO, 2021, Migrants’ Rights Network, 2020). The focus on rights which featured in the diasporic development initiatives (Fig. 5) also featured in the online exchanges during COVID-19. Evidence from the study focus group discussions indicates that rights of workers and migrants, information sharing on where or how to get help during the crisis, dispelling the myths/fake news on COVID-19 and vaccinations were dominant features of diaspora organisation discourses –both the formal and informal. The AUC/CIDO, 2021, Migrants’ Rights Network, 2020 underline the importance of this advocacy, humanitarian and capacity building aspect of diaspora remittances.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Observing the scale and development significance of remittances, governments and international development agencies have increased attention to address barriers that remitters face, such as transfer charges, regulations, speed and efficiency of delivery (ODI, 2014, DMA, 2015, Esser and Cooper, 2020, The World Bank, 2021a, The World Bank, 2021b, The World Bank, 2021c). The onset of COVID-19 inevitably raised anxieties among all key stakeholders with The World Bank (2020) predicting unprecedented declines in remittances due to low economic growth, lockdowns, illness and unemployment. However, the declines were short-lived and countries like Zimbabwe registered phenomenal increases in remittances sent during the COVID-19 pandemic. At a time the UK government was announcing a 29 % reduction in its ODA commitments from 0.7 % to 0.5 % of national income in 2020 (UK Parliament, 2021, IFS, 2021) the Zimbabwe diaspora in the UK was raising its remittance contributions. The paper confirms the countercyclical nature of diaspora remittances (ODI, 2007; The World Bank, 2021a: 30) and sought to explain how the increases occurred in the case of the UK-Zimbabwe remittances corridor.

This paper has argued that the diversity of conditions in remittance sending countries, nature and type of remittances (Bracking and Sachikonye, 2006, Mukwedeya, 2012), remittance corridors (Nyamunda, 2014) and remittance diversity indices of recipient countries (Kalantaryan & McMahon, 2020) demand that the impact of COVID-19 on remittances be examined in disaggregated ways. The World Bank (2021a) and The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021) for example have argued that COVID-19 induced lock downs closed the informal channels of remittances transfer and caused a switch to formal and mainly digital ones. Governments and money transfer operators also made initiatives to reduce the costs of remittances (ODI, 2014, Esser and Cooper, 2020; The World Bank, 2021). All this contributed to an increase in the recorded remittance inflows.

However, this paper has used data from a survey and focus group discussions with Zimbabwean diaspora in the UK to demonstrate that beyond the switch in the methods of sending remittances, the diaspora community sent more money during COVID-19 than in previous years. This happened because of the urgency and gravity of health, care and education needs arising during COVID-19 in a fragile socio-economy like Zimbabwe. In addition, the majority Zimbabwean diaspora in the UK retained their jobs and worked extra hours or borrowed to send emergency cash to family in Zimbabwe. They also made drastic consumption changes and behaviours including the use of Food Banks in order to survive or make small but fundamental savings. Those who fell ill or had to self-isolate had access to state support such as Statutory Sick Pay.

As noted by Pharoah & McKenzie (2013: 7–8), the case study of Zimbabweans in this paper reiterates the importance of diaspora remittances in international development and that although “Black and Black British populations in the UK are at the highest risk of poverty”, they are also the most likely to send money overseas. Further research, stakeholder and policy dialogue is needed to include these diaspora contributions in official household surveys and to bring this form of humanitarianism at par with donations made to and through charities. Furthermore, in the UK there is need to formulate ways of including such giving in the tax system.

Limited resources at the disposal of the researchers constrained the scope and sample size of this study. Larger longitudinal surveys should be done to deepen understanding of how COVID-19 affected remittances in different remittance corridors beyond prices (The World Bank, 2021c) for single country and community groups as well as the regional, global, and aggregate levels. Whether and to what extent coping mechanisms of Zimbabwe diaspora households mirror those of communities from other developing countries (Gupta et al., 2020, Janssens et al., 2021) requires further examination.

Implied in the diasporic remittances reported in this study is humanitarianism that illustrates and reinforces citizenship beyond the legal and civic realms as discussed in Mutambasere (2022) to social spheres of identity, culture and belonging at the family level. It is a multi-sited citizenship in which even Zimbabweans settled abroad pronounce their hostlands as ‘home from home’ (Chadya, 2013: 131). How the post-COVID-19 economic crisis (compounded by war in Ukraine) impacts on diaspora remittances remains a candidate for comparative study.

Funding

This was a self-financed project. The study reported in this paper received no funding from a public body, research funding organisation, international development agencies, private sector or civil society.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University Research Ethics Committee (Oxford Brookes University) for their suggestions on addressing legal and ethical issues related to online and social media platform based data collection. We are very grateful for the valuable feedback from two anonymous peer-reviewers and the referees appointed by the Editor. Our heartfelt thanks go to the many Zimbabweans who responded to the on-line survey. We are highly indebted to those who volunteered to share their diverse and often traumatic COVID-19 experiences and/or to participate in the focus group discussions. Names of respondents cited in the paper are pseudonyms.

Footnotes

The Index has a range of 0 to 1 with one the most diverse (i.e. a wide range of sources for remittance inflows).

Initially, the groups were supposed to be thematic but participants argued that given the overlapping nature of issues, it was best to have then as “open-ended” giving participants the opportunity to narrate experiences without limitations. Participants numbered eight, nine, six and nine. Only two males participated. Five participated in all the four sessions. COVID-19 regulations (national and University) did not permit face to face meetings at the time.

Fortunately, this did not happen.

All names from the surveys used in the paper as pseudonyms.

References

- Africanews (2020) Illegal crossings at Zimbabwe-South Africa border. Online: Africanews, 2nd October 2020. Online: https://www.africanews.com/2020/10/02/illegal-crossings-at-zimbabwe-south-africa-border// (last visited 9th August 2021).

- AUC/CIDO (2021) Mapping study on the role of African diaspora humanitarianism during COVID-19: Findings and recommendations. Addis Abba: African Union Commission/Citizens and Diaspora Directorate (CIDO), Paper prepared by SHABAKA, March 2021.

- Bisong A., Ahairwe P.E., Njoroge E. European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM); Brussels/Maastricht: 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on remittances for development in Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Bracking S., Sachikonye L. Working Paper No. 20. Global Poverty Research Group. 2006. Remittances, poverty reduction and the informalisation of household wellbeing in Zimbabwe. Online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241516390_Remittances_poverty_reduction_and_the_informalisation_of_household_wellbeing_in_Zimbabwe last visited 13th July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chadya J.M. In: Place and replace: assays on Western Canada. Perry A., Jones E., Morton L., editors. University of Manitoba Press; Winnipeg: 2013. Home away from home? The diaspora in Canada and the Zimbabwean funeral; pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chiumbu S., Musemwa M., editors. Crisis! What crisis? The multiple dimensions of the Zimbabwean crisis. Human Sciences Research Council; Cape Town: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte (2020) The COVID-19 Webinar: health, economics and business. Deloitte Webinar, Thursday, 24th September 2020, London.

- DMA . A Greenback 2.0 Report. Development Markets Associates (DMA); London: 2015. Migrants ‘remittances from the United Kingdom: International remittances and access to financial services for migrants in London, UK. survey for The World Bank and UKaid. [Google Scholar]

- Duke B. The effects of COVID-19 crisis on the gig economy and zero hour contracts. Interface: The Journal for and about Social Movements. 2020;12(1):115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Esser A., Cooper B. Bellville (South Africa): CENFRI Report for FSD Africa and UKaid. Online. 2020. Exploring remittances to Africa (Volume 7) - Removing the barriers to remittances in sub-Saharan Africa recommendations. last visited 9th August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EU (2020) Atlas of Migration 2020 , EUR 30534 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Luxembourg, JRC122942, doi:10.2760/430992.

- Financial Express (2021. “COVID-19 Pandemic Fallout: A Third of Kerala Expats Who Returned May Not Go Back.” https://www. financialexpress.com/economy/pandemic-fallout-a-third-of-kerala-expats-who-returnedmay-not-go-back/2164154/.(last visited 3rd August 2021).

- Financial Mail (2020) Lockdown: smugglers changing the way they operate. Features/Africa, Financial Mail (South Africa) 4th June 2020. Online: https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/features/africa/2020-06-04-lockdown-smugglers-changing-the-way-they-operate/ (last visited 9th August 2021).

- Gono G. ZPH Publications Pvt. Ltd; Harare: 2008. Zimbabwe’s casino economy: Extraordinary measures for extraordinary challenges. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Zhu H., Doan M.K., Michuda A., Majumder B. Economic impacts of COVID-19 lockdown in remittance-dependent region. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2020;103(2):466–485. doi: 10.1111/ajae.12178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HC . London: House of Commons (HC) Women and Equalities Committee (HC384) 2020. Unequal impact? Coronavirus and BAME people. Third Report of Session 2019–21, Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report. 15th December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. (2021) Intersecting ethnic and native–migrant inequalities in the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Research in Social Stratification and mobility, 68 (2020) 100528. Online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100528 (last visited 12th August 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- IFS (2020) Are some ethnic groups more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others? London: The Institute of Fiscal Studies (With Support from the Nuffield Foundation).

- IFS (2021) The UK’s reduction in aid spending. Briefing Note, The Institute for Fiscal Studies, London. Online: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15392 (last visited 8th August 2021).

- Janssens, W., Pradhan, M., De Groot, R., Sidze, E., Donfouet, H.P.P. and Abajobir, A. (2021) The short-term effects of COVID-19 on households in Kenya: an analysis using weekly financial household data. World Development 138 (2021) 105280. Online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105280 (last visited 12th August 2021).

- Kalantaryan S., McMahon S. Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2020. (2020) Covid-19 and Remittances in Africa, EUR 30262 EN. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantaryna, S. (2021) Remittance diversity index for Zimbabwe. Email correspondence to Mbiba, 2nd August 2021, sent at 12:14hrs GMT.

- Mbiba B. In: Skinning a skunk: Facing Zimbabwean futures. Palmberg M., Primorac R., editors. Uppsala; Nordic Africa Institute: 2005. Zimbabwe’s global citizens in ‘Harare North’ (United Kingdom): Some preliminary observations; pp. 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiba B. Beyond abject spaces: Enterprising Zimbabwean Diaspora in Britain. African Diaspora. 2011;4(1):50–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiba B. Zimbabwean diaspora politics in Britain: Insights from the Cathedral Moment 2009. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics. 2012;50(2):226–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiba, B. (2012b) Zimbabwe’s global citizens in ‘Harare North’: livelihood strategies of Zimbabweans in the United Kingdom. Pages 81 -99 in Chiumbu, S. and Musemwa, M. (2012a) Crisis! What crisis? the multiple dimensions of the Zimbabwean crisis. Cape Town: Huma Sciences Research Council.

- Mbiba B. The mystery of recurrent housing demolitions in urban Zimbabwe. International Planning Studies. 2022 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13563475.2022.2099353 [Google Scholar]

- Mbiba B., Chireka B., Kunonga E., Gezi K., Matsvai P., Manatse Z. (2020) At the deep end: COVID-19 experiences of Zimbabwean health and care workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Migration and Health. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2020.100024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor J. Joining the BBC (British Bottom Cleaners): Zimbabwean migrants and the UK care industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2007;33(5):801–824. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, J. (2010a) Introduction: the making of Zimbabwe’s new diaspora. Pages 1 – 33 in McGregor, J. and Primorac, R. (2010) Zimbabwe’s new diaspora: displacement and the cultural politics of survival. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- McGregor, J. (2010b) Diaspora and dignity: navigating and contesting civic exclusion in Britain. Pages 122 – 143 in McGregor, J. and Primorac, R. (2010) Zimbabwe’s new diaspora: displacement and the cultural politics of survival. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- McGregor J., Pasura D. Introduction: Frameworks for analysing conflict diasporas and the case of Zimbabwe. African Diaspora. 2014;7:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor J., Primorac R., editors. Zimbabwe’s new diaspora: displacement and the cultural politics of survival. Berghahn Books; Oxford: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, C Page B & Evans M (2008) Development and the African diaspora: place and the politics of home, London: Zed.

- Migrants’ Rights Network (2020) The effects of COVID-19 on migrant frontline workers and People of Colour. Report written by Migrants Rights Network, Kanlungan Filipino Consortium, The 3Million and Migrants at Work. London, December 2020. Online: https://migrantsrights.org.uk/2020/12/22/report-launch-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-poc-migrant-frontline-workers/ (last visited 11th August 2021).

- Mukwedeya, T. (2012) Enduring the crisis: remittances and household strategies in Glen Norah, Harare. Pages 42 – 61 in Chiumbu, S. and Musemwa, M. (2012) Crisis! What crisis? the multiple dimensions of the Zimbabwean crisis. Cape Town: Huma Sciences Research Council.

- Mutambasere T.G. Diaspora citizenship in practice: Identity, belonging and transnational civic activism amongst Zimbabweans in the UK. Journal of Ethnic and. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Nyamunda T. Cross-border couriers as symbols of regional grievance? the malayitsha system in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe. African Diaspora. 2014;7:38–62. [Google Scholar]

- ODI (2007) Remittances during crises: implications for humanitarian response. Humanitarian Policy Group, London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

- ODI . Overseas Development Institute (ODI); London: 2014. Lost in intermediation: How excessive charges undermine the remittances for Africa. [Google Scholar]

- ONS (2013) Key Statistics for Local Authorities in England and Wales. Office of National Statistic, UK. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/ re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77- 286262.

- ONS (2019) Population of the UK by country of birth and nationality. Office for National Statistics, UK (2019) On-line: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/datasets/populationoftheunitedkingdombycountryofbirthandnationality (3rd August 2021).

- Pasura D. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2014. African transnational diasporas: Fractured communities and plural identities of Zimbabweans in Britain. [Google Scholar]

- Pasura D. Competing meanings of the diaspora: The case of Zimbabweans in Britain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2010;36(9):1445–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Rakodi C., Lloyd-Jones T., editors. Urban livelihoods: a people centred approach to reducing poverty. Earthscan Publications Limited; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pharaoh, C. & McKenzie, T. (2013) Giving back to communities of residence and of origin. London: Alliance Publishing Trust. Online: https://www.afford-uk.org/category/publications/ (last visited 3rd August 2021).

- Ratha, D., De, S., Kim, E. J. & Plaza, S. (2020) Phase II: Covid-19 crisis through a migration lens. Migration and Development Brief, 33 (October 2020). Washington DC: The World Bank.

- RBZ . 18th February 2021. Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ); Harare: 2021. Monetary Policy Statement: Staying on Course in Fostering Price and Financial System Stability. [Google Scholar]

- Safran W. Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora. 1991;1(1):83–99. [Google Scholar]

- The Chronicle (2021) Broad daylight smuggling The Chronicle Newspaper, Wednesday 11th August, 2021, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Online: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/broad-daylight-smuggling/ (last visited 12th August 2021).

- The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021) Zimbabwean remittances soar. The Economist Intelligence Unit, London, 6th May 2021. Online: http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1950990578&Country=Zimbabwe&topic=Economy&subtopic=_1 (last visited 11th August 2021).

- The Sunday Mail (2021) Shocking bills for COVID-19 patients. The Sunday Mail, Harare, 8th August 2021. Online: https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/shocking-bills-for-covid-19-patients (last visited 12th August 2021).

- Scoones I., Wolmer W. Introduction: Livelihoods in crisis: Challenges for rural development in Southern Africa. IDS Bulletin. 2003;34(3):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank . second ed. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2011. Migration and remittances Factbook 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2020) World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History. Press Release No. 2020/175/SPJ, Washington DC: The World Bank, 22 April 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/22/world-bank-predicts-sharpest-decline-of-remittances-in-recent-history (last visited 3rd August 2021).

- The World Bank (2021a) Resilience - Covid-19 crisis through migration lens. Migration and Development Brief 34, May 2021. Washington DC: The World Bank. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/Migration%20and%20Development%20Brief%2034_1.pdf (last visited 3rd August 2021).

- The World Bank (2021b) Remittances and migration data. Washington DC: The World Bank. Online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/migrationremittancesdiasporaissues/brief/migration-remittances-data (last visited 9th August 2021).

- The World Bank (2021c) Remittances prices worldwide: making markets more transparent. The World Bank, Online: https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/en/corridor/South-Africa/Zimbabwe.

- Tololyan K. The nation state and its others; in lieu of a preface. Diaspora. 1991;1(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- UK Parliament (2021) Reduction in the IK’s 0.7 percent ODA target. London: UK Parliament, Friday 21st June 2021. Online: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/reduction-in-the-uks-0-7-percent-oda-target/ (last visited 5th August 2021).

- United Nations (2021) International Day of Family Remittances, 16th June: Remittances and the SDGS. New York: United Nations, Online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/remittances-day/SDGs (last visited 3rd August 2021).

- Hear V. Routledge; London: 1998. New Diasporas: The mass exodus, dispersal and regrouping of migrant communities. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovic S., Cohen R., editors. Migration, Diaspora and transculturalism. Edward Elgar Publishing; Chelternham, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]