Abstract

Background

Clinical trials have established the high effectiveness and safety of medication abortion in clinical settings. However, barriers to clinical abortion care have shifted most medication abortion use to out-of-clinic settings, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this shift, we aimed to estimate the effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion (medication abortion without clinical support), and to compare it to effectiveness of clinician-managed medication abortion.

Methods

For this prospective, observational cohort study, we recruited callers from two safe abortion accompaniment groups in Argentina and Nigeria who requested information on self-managed medication abortion. Before using one of two medication regimens (misoprostol alone or in combination with mifepristone), participants completed a baseline survey, and then two follow-up phone surveys at 1 week and 3 weeks after taking pills. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants reporting a complete abortion without surgical intervention. Legal restrictions precluded enrolment of a concurrent clinical control group; thus, a non-inferiority analysis compared abortion completion among those in our self-managed medication abortion cohort with abortion completion reported in historical clinical trials using the same medication regimens, restricted to participants with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation. This study was registered with ISCRTN, ISRCTN95769543.

Findings

Between July 31, 2019, and April 27, 2020, we enrolled 1051 participants. We analysed abortion outcomes for 961 participants, with an additional 47 participants reached after the study period. Most pregnancies were less than 12 weeks' duration. Participants in follow-up self-managed their abortions using misoprostol alone (593 participants) or the combined regimen of misoprostol plus mifepristone (356 participants). At last follow-up, 586 (99%) misoprostol alone users and 334 (94%) combined regimen users had a complete abortion without surgical intervention. For those with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation, both regimens were non-inferior to medication abortion effectiveness in clinical settings.

Interpretation

Findings from this prospective cohort study show that self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment group support is highly effective and, for those with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation, non-inferior to the effectiveness of clinician-managed medication abortion administered in a clinical setting. These findings support the use of remote self-managed models of early abortion care, as well as telemedicine, as is being considered in several countries because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Translations

For the Arabic, French, Bahasa Indonesian, Spanish and Yoruba translations of the Article see Supplementary Materials section.

Introduction

The WHO-recommended medication regimens of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol, or misoprostol alone,1 are established safe and effective methods of terminating pregnancy.2, 3, 4 Clinical trials have shown high levels of effectiveness and safety of both medication abortion regimens in the first 63 days of pregnancy5, 6 and, more recently, up to 84 days of pregnancy.7 Data for these trials have been collected in high-income and low-income contexts,8 and among abortions provided by multiple cadres of clinical providers.9, 10

Medication abortion is a low-cost, safe, effective, and relatively simple method of pregnancy termination. However, restrictive legal contexts, lack of trained or willing providers, cost of clinical services, experiences of mistreatment at health facilities, and other logistical and social concerns are persistent barriers to clinic-based abortion services.11 Consequently, most abortion by use of medication globally occurs outside of clinic settings.12

The use of medications to end a pregnancy on one's own, without clinical supervision, is referred to as self-managed medication abortion.11 Examples of self-managed medication abortion range from obtaining pills online or from a local pharmacy and using the medications at home without clinical support, to self-managed abortion supported by safe abortion accompaniment groups, wherein trained abortion counsellors (most of whom do not have clinical training) provide evidence-based counselling and person-centred support (over the phone or in-person) to a person who is self-managing an abortion. The self-managed abortion accompaniment model emerged as an area of autonomous health action and self-determination among feminist movements in response to the failure of the state to provide safe abortion care. This movement is characterised by activist-driven, community-based strategies to facilitate use of widely available medications outside clinical settings.13 For some people, self-managed medication abortion is a preferred model of care for the privacy and comfort it affords; for others, it is the only option when clinical care is inaccessible.11

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

To understand what is known about the effectiveness and safety of self-managed medication abortion outside a clinical setting, we did a systematic scoping review of the literature on self-managed abortion effectiveness in eight biomedical and public health databases in English and Spanish, with no date or duration of pregnancy limits. This review has been previously published and identified eight studies that reported high effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion. Since publication, several additional studies have been published on self-managed abortion effectiveness. Most studies are retrospective analyses and report high levels of abortion completion after self-managed medication abortion, ranging, by gestational age, from 48·3% to 99·5%. In our review, we identified very few prospective studies of self-managed medication abortion use, and no studies that formally assessed the non-inferiority of self-managed medication abortion compared with clinical medication abortion regarding abortion completion. Furthermore, few studies reported on reasons for health-care seeking after self-managed abortion.

Added value of this study

Results from this prospective, multi-country study support that self-managed medication abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol, as well as misoprostol alone, is highly effective and safe, and for those with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation, is non-inferior to the effectiveness of medication abortion in clinical settings. People who self-managed their abortion with accompaniment support succeeded in accessing care at clinics and hospitals, and primarily did so to confirm completion of the abortion, not for a safety concern.

Implications of all the available evidence

Data from our study show that self-managed abortion using misoprostol alone or in combination with mifepristone is highly effective. Given these results, to ensure access to a safe, effective, and routine medical service, ministries of health, professional bodies, and clinicians themselves should remove restrictions on and barriers to self-managed approaches for medication abortion and facilitate access to accurate information on medication abortion across a range of service delivery models, including self-use. Results from this study suggest that self-managed abortion with accompaniment support can be a core strategy for expanding access to safe, effective abortion care, regardless of legal setting.

Consistent with clinical trials that established medication abortion safety and efficacy, there is a growing body of evidence showing the effectiveness and safety of self-managed medication abortion.11, 14, 15 However, in many cases, study limitations, such as a reliance on retrospective record reviews, small sample sizes, and loss to follow-up, have undermined the full utility of the results.16 WHO guidance articulates the need for evidence on the safety, efficacy, and acceptability of medication abortion outside of clinic settings, particularly for pregnancies beyond 10 weeks' gestation, along with a need to understand the role of the individual in self-assessment of eligibility and abortion completion, especially for misoprostol alone regimens, which clinical data have suggested are less effective.1 Additionally, calls for rigorously collected data on people's experiences with self-managed abortion, and health-care seeking during and after self-managed abortion, have increased to determine whether individuals can safely and effectively manage the entire medication abortion process.12, 17

Abortion accompaniment groups provide a promising platform for rigorous, prospective research on self-managed medication abortion.18 To address gaps in research on self-managed medication abortion, we conducted a prospective, observational cohort study to estimate the effectiveness of both mifepristone with misoprostol (the combined regimen) and misoprostol alone regimens when used to terminate a pregnancy without clinical supervision, but with support from accompaniment groups, and to formally compare this effectiveness with the effectiveness of clinician-managed medication abortion shown in historical clinical trials via a non-inferiority analysis. Because of legal restrictions on abortion in both sites, recruitment of a concurrent clinical control group was unfeasible. We hypothesised that the effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion with both regimens would be high (>90%), and that self-managed medication abortion effectiveness would be non-inferior to effectiveness of medication abortion measured in clinical settings within a 5% non-inferiority margin.16

Methods

Study design and participants

The studying accompaniment feasibility and effectiveness (SAFE) study, a prospective, observational cohort study, enrolled people who contacted an abortion accompaniment group for self-managed abortion information and support and followed up for up to 4 weeks to assess abortion outcomes and experiences. Results from a pilot study, and full details of the study protocol, have been previously published.16, 18

We recruited callers from two abortion accompaniment groups—one in Argentina (based in Neuquén, primarily serving Neuquén province) and one in Nigeria (based in Lagos state, serving the entire country). At the time of data collection, abortion was illegal at both sites, with exceptions only to save the life of the pregnant person,19 or additionally in the case of rape for Argentina.20 Anyone who contacted either group during the study period requesting information about induced abortion for their own pregnancy was screened for eligibility. Anyone aged 13 years or older, starting a new medication abortion process, with no contraindications to medication abortion,1 and within a gestational age range that the accompaniment group supported—up to 24 weeks' gestation in Argentina and up to 15 weeks' gestation in Nigeria—was eligible for inclusion in the study.16 We excluded those with ongoing symptoms (eg, bleeding or cramping) from a previous abortion attempt, with symptoms suggestive of ectopic pregnancy, or who did not want to or were unable to be contacted by study staff.

All participants provided verbal informed consent. The Allendale Investigational Review Board reviewed and approved this multi-country study, and the Fundación Huésped institutional review board additionally approved the Argentina-specific protocol. An independent data monitoring and oversight committee reviewed study protocols and instruments, and a planned interim analysis of any safety events.

Procedures

At baseline, all participants received step-by-step instructions from accompaniment group counsellors on the appropriate WHO-recommended protocol for medication abortion (table 1 ) on the basis of duration of pregnancy (assessed via independently acquired ultrasound or date of last menstrual period)1, 16 and which medications the caller could access.

Table 1.

Medication protocols recommended by abortion accompaniment group counsellors on the basis of duration of pregnancy

| Mifepristone plus misoprostol | Misoprostol alone | |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 90 days | Swallow one tablet of mifepristone (200 mg) orally; after 24–48 h, put four pills of misoprostol (800 μg) under the tongue (sublingual), let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve, or place them in the vagina (vaginal); if, after 3 h, there are no signs of reaction, side-effects, or expulsion, put two additional misoprostol pills (400 μg) under the tongue or in the vagina, and let them dissolve | Put four pills (800 μg) under the tongue (sublingual), let them dissolve for 30 min, keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; after 3 h, put the second dose of four pills (800 μg) under the tongue and let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; after 3 h, put a third dose of four pills (800 μg) under the tongue, let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; continue with two to four misoprostol pills under the tongue every 3 h until expulsion occurs |

| Beyond 90 days* | Swallow one tablet of mifepristone (200 mg) orally; after 36–48 h, put two pills of misoprostol (400 μg) under the tongue (sublingual), let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; after 3 h, put two additional misoprostol pills (400 μg) under the tongue, and let them dissolve; continue with two misoprostol pills under the tongue every 3 h until expulsion occurs | Put two pills (400 μg) under the tongue (sublingual), let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; after 3 h, put the second dose of two pills (400 μg) under the tongue, let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; after 3 h, put a third dose of two pills (400 μg) under the tongue, let them dissolve for 30 min, and keep swallowing saliva until the pills dissolve; continue with two misoprostol pills under the tongue every 3 h until expulsion occurs |

After initial information counselling, participants answered a baseline questionnaire administered by their accompaniment counsellor. For all subsequent data collection, a trained study coordinator contacted each participant at two timepoints (1 week and 3 weeks after taking the first dose of medication) to assess access to and use of medication abortion, and document side-effects, additional doses taken, abortion completion, potential complications, and health-care seeking behaviour. Participants were compensated US$10–25 for participation in the study. Study procedures were consistent across both sites, except for pregnancy confirmation—counsellors in Argentina offered a randomly selected subset of participants a urine pregnancy test to confirm pregnancy (which was not offered in Nigeria).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment support, calculated as the percentage of respondents who self-reported a complete abortion without surgical intervention, overall and by medication regimen. Research has established that people are able to accurately self-assess abortion completion.23 The secondary outcome was an assessment of non-inferiority of self-managed medication abortion effectiveness, compared with clinician-managed medication abortion effectiveness, as measured in historical clinical trials.

Other outcomes measured included medication sourcing and use, factors that influenced self-assessment of abortion completion, and health-care seeking behaviour and treatment received. To measure safety and adverse event outcomes, we asked participants to self-report whether they had any of nine distinct safety outcomes (heavy bleeding, extreme pain, foul-smelling discharge, high fever, receipt of antibiotics, receipt of manual vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage, blood transfusion, receipt of intravenous fluids, or overnight facility stay). Participants were also asked to self-report any other treatments received. We additionally collected data on participant age, education, ascertainment of pregnancy, and gestational age.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to estimate the proportion of participants who had a complete abortion without surgical intervention after self-managed abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol or misoprostol alone, and to evaluate whether self-managed medication abortion effectiveness is non-inferior to effectiveness of clinician-managed medication abortion, as reported in historical clinical trials, within a margin of 5%.24, 25, 26, 27

For our primary analyses, we pre-specified exclusion of participants with unknown abortion outcomes, consistent with the comparison clinical trials.16, 24 The proportion of study participants who had a complete abortion was assessed via response to the following question, “Do you feel that your abortion process is complete?”, as well as whether they reported receiving a manual vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage procedure. Participants who reported that their abortion was complete and did not report receiving a surgical intervention were categorised as having a complete abortion without surgical intervention; participants who reported that their abortion was complete and reported receiving a manual vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage procedure were categorised as having a complete abortion with surgical intervention. Participants who reported that their abortion was not complete or reported being unsure about whether their abortion was complete were categorised as having an incomplete abortion or being unsure. We calculated all proportions overall, by medication regimen, and by duration of pregnancy (<7 weeks, 7–9 weeks, 10–12 weeks, and ≥13 weeks). Due to the differential registration of mifepristone in each country and an abundance of caution on behalf of implementing partners, we do not report the number of regimen users by country. Participants from both countries are represented in each regimen group; thus, we pooled across countries to calculate the primary outcomes.

Establishing the effectiveness and safety of self-managed medication abortion compared with clinician-managed medication abortion in clinic settings is an important gap in the evidence. Due to legal restrictions, recruitment of a concurrent clinical control group as part of the SAFE study was unfeasible. Thus, per established precedent,28 we identified previously published randomised controlled trials of medication abortion effectiveness in clinical settings to serve as historical controls for a non-inferiority analysis: three trials studied the same combined regimen,25, 26, 27 and one trial studied the same misoprostol alone regimen.24 These were the only identified trials where the regimen used was identical to the regimens recommended by the accompaniment groups, and all are widely cited in relevant safe abortion guidance.1 Historical controls are not intended to be a substitute for random assignment; however, to assess comparability, we tested for differences in participant age and duration of pregnancy in the SAFE study compared with historical controls using t tests and tests of proportion. We extracted data on abortion completion from the published results of the historical controls.

We did two tests for non-inferiority: one among users of the misoprostol alone regimen, and one among users of the combined regimen. We restricted the SAFE sample to participants with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation to match the eligibility criteria of comparison studies. Full details of the non-inferiority analysis have been published previously18 and are detailed in appendix 6 (pp 7–9).

Data were analysed with STATA version 15.1. The target minimum sample size was 213 for the combined regimen and 419 for the misoprostol alone regimen for a one-sided test to assess whether self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment support is no more than 5% less effective than the clinical setting for each regimen, with 80% power, an α of 5% and no correlation within counsellors (based on pilot study results).18 This study is registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN95769543.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

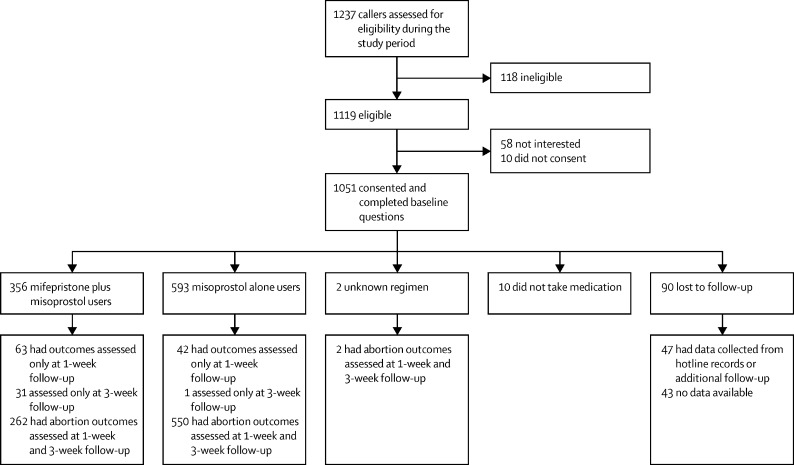

Between July 31, 2019, and April 27, 2020, study recruiters screened 1237 callers for eligibility (figure 1 ). 118 (10%) of callers were ineligible because of needing support unrelated to abortion, already having started a medication abortion process, or having symptoms from an ongoing abortion or miscarriage. Among the 1119 eligible callers, 1051 (94%) gave consent to participate, completed baseline questions, and were enrolled in the study (401 from Argentina and 650 from Nigeria). 961 (91%) of the 1051 enrolled participants completed at least one follow-up and reported whether they obtained and took the medications. Among those with at least one follow-up contact, 929 (97%) of 961 completed the 1-week survey and 846 (88%) completed the 3-week survey. Among the 90 participants lost to follow-up after baseline, 47 (52%) were reached later to ascertain primary outcomes and 43 (48%) had unknown outcomes.

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Participants ranged in age from 14 to 50 years, with most aged 20–29 years (table 2 ). Argentinian participants resided in three provinces (Neuquén, Río Negro, and Salta). Nigerian participants resided in 28 states (most commonly Lagos, Imo, and Abia). Most participants ascertained their pregnancies with a home pregnancy test. Among a random sample of participants that took home pregnancy tests at baseline, two (2%) of 102 tests were negative. Participants reported pregnancies of 4 weeks to 22 weeks' gestation at baseline. Most pregnancies were less than 12 weeks' duration.

Table 2.

Participant sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics

| All regimens (n=1051) | Mifepristone and misoprostol (n=356) | Misoprostol alone (n=593) | Unknown (n=102) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 28·1 (6·0) | 27·5 (6·3) | 28·5 (5·8) | 33·0 (12·7) | |

| 14 | 2 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | |

| 15–19 | 50 (5%) | 27 (8%) | 17 (3%) | 6 (6%) | |

| 20–24 | 271 (26%) | 101 (28%) | 136 (23%) | 34 (33%) | |

| 25–29 | 340 (32%) | 103 (29%) | 214 (36%) | 23 (23%) | |

| 30–34 | 211 (20%) | 73 (21%) | 116 (20%) | 22 (22%) | |

| 35–39 | 137 (13%) | 35 (10%) | 89 (15%) | 13 (13%) | |

| 40–44 | 36 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 18 (3%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 45–49 | 3 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| 50 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | |

| Level of education | |||||

| No schooling | 2 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Completed primary school | 134 (13%) | 97 (27%) | 14 (2%) | 23 (23%) | |

| Completed secondary school | 397 (38%) | 117 (33%) | 248 (42%) | 32 (31%) | |

| More than secondary school | 518 (49%) | 140 (39%) | 331 (56%) | 47 (46%) | |

| Ascertainment of pregnancy | |||||

| Took pregnancy test at home | 700 (67%) | 292 (82%) | 334 (56%) | 74 (73%) | |

| Took blood test in a facility | 285 (27%) | 55 (15%) | 205 (35%) | 25 (25%) | |

| Took urine test in a facility | 114 (11%) | 2 (1%) | 105 (18%) | 7 (7%) | |

| Ultrasound | 113 (11%) | 89 (25%) | 7 (1%) | 17 (17%) | |

| Late or missed period | 37 (4%) | 31 (9%) | 1 (<1%) | 5 (5%) | |

| Pregnancy symptoms | 13 (1%) | 11 (3%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | |

| Other | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Duration of pregnancy | 7·0 (2·2) | 7·6 (2·6) | 6·7 (1·8) | 7·0 (1·4) | |

| <7 weeks | 518 (49%) | 141 (40%) | 330 (56%) | 47 (46%) | |

| 7 to <9 weeks | 340 (32%) | 134 (38%) | 174 (29%) | 32 (31%) | |

| 9 to <12 weeks | 141 (13%) | 50 (14%) | 75 (12%) | 16 (16%) | |

| 12 to 22 weeks | 52 (5%) | 31 (9%) | 14 (2%) | 7 (7%) | |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%).

At the 1-week follow-up, 922 (96%) participants had obtained and 919 (96%) participants had taken the medications, including those who obtained an unknown medication (appendix 6, pp 3–4). Three (<1%) participants reported obtaining pills but not taking them because they decided to continue the pregnancy. For users of the combined regimen, all participants reported taking mifepristone first, and most followed this with four pills of misoprostol (349 [98%] of 356 participants), taken sublingually (274 [77%] of 356 participants; appendix 6 pp 3–4). Three (1%) participants reported taking a second dose of a single mifepristone pill before continuing to misoprostol—these three participants were at later durations of pregnancy (16, 17, and 19 weeks' gestation). For 593 users of the misoprostol alone regimen, most participants took four pills for all three doses, and almost all sublingually. Participants from both countries were represented in each regimen group; however, most combined regimen users lived in Argentina, whereas most misoprostol alone users lived in Nigeria.

Around 1 week after taking the pills, 868 (94%) of 919 participants who reported taking pills and completed the 1-week follow-up reported complete abortion without surgical intervention (300 [92%] of 325 combined regimen users, and 566 [96%] of 592 misoprostol alone users), and an additional ten (1%) participants reported complete abortion with surgical intervention (table 3 ). By the last study follow-up, 922 (97%) of 951 participants reported complete abortion without surgical intervention, and 17 (2%) reported complete abortion with surgical intervention. Abortion completion was high across both drug regimens. Among combined regimen users, the occurrence of surgical intervention to complete the abortion increased with advancing duration of pregnancy.

Table 3.

Abortion completion

| Any regimen (all gestations)* |

Mifepristone plus misoprostol |

Misoprostol alone |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All gestations | <7 weeks | 7 to <9 weeks | 9 to <12 weeks | 12 to 22 weeks | All gestations | <7 weeks | 7 to <9 weeks | 9 to <12 weeks | 12 to 22 weeks | ||

| 1 week after taking the pills† | |||||||||||

| Complete without surgical intervention | 868/919 (94%) | 300/325 (92%) | 126/132 (95%) | 112/122 (92%) | 41/45 (91%) | 21/26 (81%) | 566/592 (96%) | 317/329 (96%) | 165/174 (95%) | 70/75 (93%) | 14/14 (100%) |

| Complete with surgical intervention | 10/919 (1%) | 9/325 (3%) | 1/132 (1%) | 2/122 (2%) | 2/45 (4%) | 4/26 (15%) | 1/592 (<1%) | 1/329 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Incomplete or unsure | 40/919 (4%) | 16/325 (5%) | 5/132 (4%) | 8/122 (7%) | 2/45 (4%) | 1/26 (4%) | 24/592 (4%) | 11/329 (3%) | 9/174 (5%) | 4/75 (5%) | 0 |

| Missing | 1/919 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/592 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 1/75 (1%) | 0 |

| At last follow-up (up to 4 weeks after taking first dose) | |||||||||||

| Complete without surgical intervention | 922/951 (97%) | 334/356 (94%) | 134/141 (95%) | 131/134 (98%) | 46/50 (92%) | 23/31 (74%) | 586/593 (99%) | 327/330 (99%) | 172/174 (99%) | 74/75 (99%) | 13/14 (93%) |

| Complete with surgical intervention | 17/951 (2%) | 14/356 (4%) | 2/141 (1%) | 2/134 (1%) | 3/50 (6%) | 7/31 (23%) | 3/593 (1%) | 2/330 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 1/14 (7%) |

| Incomplete or unsure | 10/951 (1%) | 8/356 (2%) | 5/141 (4%) | 1/134 (1%) | 1/50 (2%) | 1/31 (3%) | 2/593 (<1%) | 1/330 (<1%) | 1/174 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 2/951 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/593 (<1%) | 0 | 1/174 (1%) | 1/75 (1%) | 0 |

Data are n/N (%).

Includes two participants with unknown medication abortion regimen.

32 participants who did not complete a first follow-up are excluded from the denominator for the 1-week outcomes.

Study coordinators reached 47 (52%) of 90 participants who were lost to follow-up after the study period to record the primary outcome—39 reported a complete abortion without surgical intervention. Under the conservative assumption that the remaining 43 (48%) participants who were unreachable after baseline did not have a complete abortion, overall abortion completion at last follow-up would fall to 961 (91%) of 1051 participants without surgical intervention. After including surgical interventions and miscarriages among those lost to follow-up, 987 (94%) participants were no longer pregnant at the end of follow-up.

Among participants who reported that their abortion was complete, almost all cited more than one factor that influenced their assessment of abortion completion, including 367 (39%) reporting some form of clinical confirmation of completion (appendix 6 p 4).

During study follow-up, 192 (20%) of 951 participants sought health care from a hospital or clinic (120 [34%] combined regimen users, 71 [12%] misoprostol alone users, and one [8%] participant with an unknown medication abortion regimen; appendix 6 p 6). Among participants that sought health care, most did so to confirm completion of the abortion (157 [82%] of 192 participants). 21 [11%] of 192 participants sought care for concerns related to pain, bleeding, discharge, or fever. Participants most frequently reported receiving the following treatments: ultrasonography (80 [8%] of 951 participants), pain medications (25 [3%] participants), intravenous fluids (19 [2%] participants), and antibiotics (16 [2%] participants). 17 (2%) participants reported receiving a manual vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage, and 12 (1%) reported staying overnight at a medical facility (all of whom had a manual vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage procedure), and six (1%) participants reported receiving a blood transfusion. Participants in Argentina were more likely to obtain a manual vacuum aspiration than participants from Nigeria (risk difference 9·2%, 95% CI 3·4–15·0; p=0·0013). 782 (82%) of 951 participants reported no potential warning signs of complications, 84 (9%) reported bleeding that soaked more than two pads per h and lasted more than 2 h, 80 (8%) reported foul smelling or coloured discharge, 50 (5%) reported pain that interfered with normal activities, and 16 (2%) reported a fever higher than 38°C for more than 24 h.

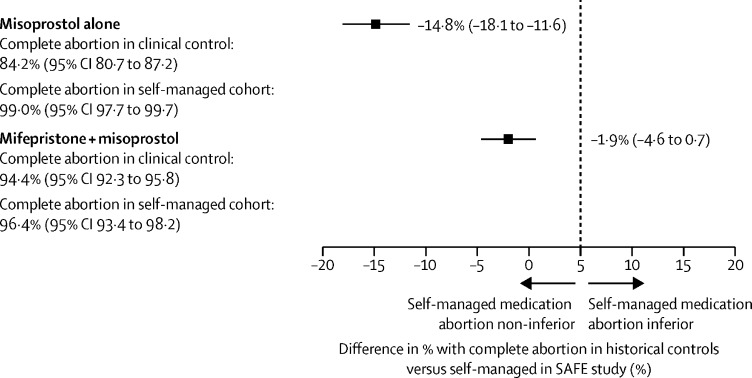

For the non-inferiority analysis, 1463 evaluable participants in the four comparator historical control studies had pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation, resided in one of 11 countries (Armenia, China, Cuba, Georgia, India, Mongolia, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden, Thailand, and Vietnam), and were randomly assigned to the same medication abortion regimen studied in the SAFE study (951 to the combined regimen and 512 with misoprostol alone), and were compared with 779 SAFE participants with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation (275 with combined regimen and 504 to misoprostol alone). By medication regimen, participants in the SAFE study and historical control studies were similar, although SAFE participants were slightly older (by 1–4 years on average), and slightly earlier in their pregnancies (around 1 week on average; appendix 6 pp 7–9).

Among users of the combined regimen, abortion completion among SAFE participants with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation was 96% (265 of 275 participants), compared with a pooled completion level of 94% (898 of 951 participants) among the three historical control groups (risk difference −1·9%, 95% CI −4·6 to 0·7; figure 2 ; appendix 6 p 11).25, 26, 27 Among users of misoprostol alone, abortion completion among SAFE participants with pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation was 99% (499 of 504 participants), compared with 84% (431 of 512 participants) completion reported in the single matched historical control group (risk difference −14·8%, −18·1 to −11·6).24 As the upper bounds of the 95% CIs for the risk difference between self-managed abortion and clinically-manged abortion for both regimens are less than the specified non-inferiority margin of 5%, we reject the null hypothesis of inferiority.

Figure 2.

Assessment of non-inferiority of self-managed medication abortion effectiveness, as measured in the SAFE study among 779 participants with pregnancies <9 weeks' gestation, compared with clinician-managed medication abortion effectiveness, as measured in historical clinical trials among 1463 participants with pregnancies <9 weeks' gestation

SAFE=studying accompaniment feasibility and effectiveness.

Discussion

Our findings show that self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment group support is highly effective and, for pregnancies of less than 9 weeks' gestation, is non-inferior to the effectiveness of clinician-managed medication abortion administered in a clinical setting. Over approximately 4 weeks of follow-up, most participants obtained medications, took them according to WHO-based protocols, and completed their abortions; a small number of participants (20%) sought health care at a clinic or hospital, primarily to confirm completion of the abortion.

Our results contribute to a growing evidence base concerning the effectiveness and safety of self-managed abortion with medication, with and without accompaniment support.11, 14, 15, 16 Taken together, these findings have several broad implications. First, results from the SAFE study add to a robust body of evidence that medication abortion is effective across a range of service delivery models in both clinical and non-clinical settings. The safety and effectiveness of medication abortion has been well established across a range of health-care worker supported settings, including traditional clinical settings,3, 24, 25, 26, 27 over video call with a clinician,29 and self-managed settings with pharmacy support.15 These findings show that medication abortion is also effective when self-managed at home with information provided by non-clinically trained abortion counsellors.

Additionally, SAFE study findings indicate that self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment support is safe, and that non-clinically trained abortion counsellors can support people to understand when and how to access care if they need or want to during a self-managed abortion. Observed differences in manual vacuum aspiration by country might be due to differences in accessibility of this service by country, as well as differences in accompaniment group relationships to trusted health-care providers. Although we cannot be sure that everyone who wanted to seek health care did so, our data suggest that people were able to access care when it was needed. From a measurement perspective, these findings challenge the notion that any health-care facility visit during or after a self-managed abortion should be measured as an abortion complication and, from a care provision perspective, should encourage health-care systems to reconsider how to best support people who self-manage abortion.

Notably, effectiveness of misoprostol alone in the SAFE study is higher than that typically reported in clinical trials.6 However, findings from this study are consistent with effectiveness levels of 92·6–96·4% reported in studies of self-managed abortion with misoprostol alone.14, 15, 18 The higher effectiveness of misoprostol alone seen in studies from self-managed contexts versus the effectiveness of misoprostol alone seen in clinical contexts can be attributed to the following factors. First, studies of self-managed medication abortion have typically assessed abortion completion over a 3–4-week time period, compared with the much shorter time period of 1–2 weeks in clinical trials.30 Additionally, in clinical trials, participants whose abortions are in process, incomplete, missed, or failed at the time of outcome assessment are typically recommended for surgical intervention,24 whereas participants in self-managed contexts are more likely to be counselled in an expectant management approach or counselled to take additional doses of misoprostol—in accordance with WHO guidelines1—before seeking additional medical care.30 Finally, in both the SAFE study and other out-of-clinic studies, study participants had on-demand access to abortion counsellors who were available as a resource for questions about the range of normal bleeding and side-effects, and to refer for care seeking in the event of possible complications. This kind of regular, supportive communication has been shown to help abortion clients feel more prepared for their abortion experience,31 and might have contributed to improved understanding of and ability to allow the medication abortion process to take its course. Given the higher effectiveness of misoprostol alone regimens reported in self-managed abortion contexts compared with clinical contexts, additional research is warranted to explore how adjusted protocols, as well as improved counselling and support for abortion clients in clinical settings, can maximise the effectiveness of misoprostol alone regimens.

Conducting a prospective study among people self-managing abortions in restrictive contexts presents some challenges. Notably, the study design relied on self-reported gestational age and abortion outcome, outcomes that are typically confirmed via ultrasound in clinical studies. However, the reliance on self-report for these eligibility characteristics and outcomes is informed by research that has shown the accuracy of report of last menstrual period compared with ultrasound assessment,32 and the effectiveness and safety of medication abortion without screening ultrasound.33 Indeed, WHO technical guidance does not require ultrasound confirmation of gestational age for early medication abortion.1 Furthermore, studies in a range of settings have shown the reliability of self-report of abortion completion.23 Given legal restrictions for abortion in both sites, it was unfeasible to recruit a concurrent clinical control. Therefore, we relied on borrowing from historical clinical trials that studied the same medication regimens within the same gestational age range,24, 25, 26, 27 an analytical approach for which there is robust precedent.28 Although we observed minor differences in two baseline characteristics between the SAFE study cohorts and the historical controls, based on existing literature and a meta-analysis of regimen effectiveness at different gestational ages, we would not anticipate a difference of several days' gestation below 9 weeks nor a difference in participant age of between 1–4 years to drive major differences in abortion completion.34 This study also had participant attrition— 4% of participants were not reachable after baseline. To account for this, we conservatively estimated effectiveness as if all participants lost to follow-up had a failed abortion. However, the true effect of potential sources of bias could be much lower, and future analyses could quantify this. Finally, this study was not designed to compare the combined regimen to misoprostol alone, but rather to assess each regimen's individual effectiveness in the self-managed context compared with the published literature on medication abortion in a clinical setting. Thus, we caution readers against drawing comparisons between outcomes reported in the combined regimen group versus the misoprostol alone group of the SAFE study. These limitations are balanced by the unique nature of the study sample, which enabled us to prospectively follow up participants who were self-managing abortion across two distinct contexts, the large, adequately powered sample, and low loss-to-follow-up.

In conclusion, self-managed medication abortion with accompaniment support is highly effective and safe. Going forward, governments, professional bodies, and clinicians should rely on evidence to guide their policies and practices towards self-managed approaches for medication abortion and focus on expanding access to medication abortion across a range of service delivery models, including self-use.

Data sharing

The study protocol, analysis plan, and instruments are available to the scientific community online.16 All data requests should be submitted to the principal investigator via email (hmoseson@ibisreproductivehealth.org) for consideration. Access to the anonymised data might be granted after review and approval of an investigator-initiated concept note by the principal investigator and data monitoring and oversight committee, and after the investigator signs a data access agreement.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to CG, HM, and RJ. HM is partly supported by a National Institute of Health grant (1R21CA256759-01). We are grateful to study participants for sharing information about their self-managed abortion processes with the study team. We also thank Ilana Dzuba, Sofía Filippa, Brianna Keefe-Oates, Onikepe Owolabi, Maria Yasinta, and the team at La Revuelta and the team at Generation Initiative for Women and Youth Network for their tremendous contributions to this work in various forms.

Contributors

BG, CG, HM, IAK, IE, RJ, RM, RZ, and SN contributed to the quantitative study conceptualisation and design. CB, HM, RJ, RM, and SC managed data collection and quality. HM and RJ conducted the quantitative analyses. HM led the writing of the manuscript, with contributions, review, and approval from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors had access to all the data in the study, and two authors (HM and RJ) have accessed and verified the data. CG, HM, and RJ were responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Medical management of abortion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez MI, Seuc A, Kapp N, et al. Acceptability of misoprostol-only medical termination of pregnancy compared with vacuum aspiration: an international, multicentre trial. BJOG. 2012;119:817–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winikoff B, Sivin I, Coyaji KJ, et al. Safety, efficacy, and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba, and India: a comparative trial of mifepristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulier R, Kapp N, Gulmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng L, Campana A. Medical methods for first trimester abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen MJ, Creinin MD. Mifepristone with buccal misoprostol for medical abortion: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:12–21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raymond EG, Harrison MS, Weaver MA. Efficacy of misoprostol alone for first-trimester medical abortion: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:137–147. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapp N, Eckersberger E, Lavelanet A, Rodriguez MI. Medical abortion in the late first trimester: a systematic review. Contraception. 2019;99:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson I, Scott H. Systematic review of the effectiveness, safety, and acceptability of mifepristone and misoprostol for medical abortion in low- and middle-income countries. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42:1532–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocca CH, Puri M, Shrestha P, et al. Effectiveness and safety of early medication abortion provided in pharmacies by auxiliary nurse-midwives: a non-inferiority study in Nepal. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress-sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391:2642–2692. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, Barr-Walker J, Baum SE, Gerdts C. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;63:87–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390:2372–2381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braine N. Autonomous health movements: criminalization, de-medicalization, and community-based direct action. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22:85–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster AM, Arnott G, Hobstetter M. Community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion: evaluation of a program along the Thailand-Burma border. Contraception. 2017;96:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stillman M, Owolabi O, Fatusi AO, et al. Women's self-reported experiences using misoprostol obtained from drug sellers: a prospective cohort study in Lagos State, Nigeria. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moseson H, Keefe-Oates B, Jayaweera RT, et al. Studying Accompaniment model Feasibility and Effectiveness (SAFE) study: study protocol for a prospective observational cohort study of the effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralph L, Foster DG, Raifman S, et al. Prevalence of self-managed abortion among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moseson H, Jayaweera R, Raifman S, et al. Self-managed medication abortion outcomes: results from a prospective pilot study. Reprod Health. 2020;17:164. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01016-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okorie PC, Abayomi OA. Abortion laws in Nigeria: a case for reform. Ann Surv Intl Comp Law. 2019;23:165–192. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Código Penal de la Nación Argentina. 1984. http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/15000-19999/16546/texact.htm#15

- 21.Zurbriggen R, Keefe-Oates B, Gerdts C. Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina. Contraception. 2018;97:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moseson H, Bullard KA, Cisternas C, Grosso B, Vera V, Gerdts C. Effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion between 13 and 24 weeks gestation: a retrospective review of case records from accompaniment groups in Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Contraception. 2020;102:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt-Hansen M, Cameron S, Lohr PA, Hasler E. Follow-up strategies to confirm the success of medical abortion of pregnancies up to 10 weeks' gestation: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Huong NTM, et al. Efficacy of two intervals and two routes of administration of misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1938–1946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Hertzen H, Huong NT, Piaggio G, et al. Misoprostol dose and route after mifepristone for early medical abortion: a randomised controlled noninferiority trial. BJOG. 2010;117:1186–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang OS, Chan CC, Ng EH, Lee SW, Ho PC. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on the use of mifepristone with sublingual or vaginal misoprostol for medical abortions of less than 9 weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2315–2318. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang OS, Xu J, Cheng L, Lee SW, Ho PC. Pilot study on the use of sublingual misoprostol with mifepristone in termination of first trimester pregnancy up to 9 weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1738–1740. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viele K, Berry S, Neuenschwander B, et al. Use of historical control data for assessing treatment effects in clinical trials. Pharm Stat. 2014;13:41–54. doi: 10.1002/pst.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, Ghosh N, Starling J. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no-test medical abortion provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1464–1474. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayaweera RT, Moseson H, Gerdts C. Misoprostol in the era of COVID-19: a love letter to the original medical abortion pill. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28 doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1829406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Kristianingrum IA, Khan Z, Hudaya I. Effect of a smartphone intervention on self-managed medication abortion experiences among safe-abortion hotline clients in Indonesia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149:48–55. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bracken H, Clark W, Lichtenberg ES, et al. Alternatives to routine ultrasound for eligibility assessment prior to early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone-misoprostol. BJOG. 2011;118:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raymond E, Chong E, Winikoff B, et al. TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States. Contraception. 2019;100:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashok PW, Templeton A, Wagaarachchi PT, Flett GM. Factors affecting the outcome of early medical abortion: a review of 4132 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2002;109:1281–1289. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study protocol, analysis plan, and instruments are available to the scientific community online.16 All data requests should be submitted to the principal investigator via email (hmoseson@ibisreproductivehealth.org) for consideration. Access to the anonymised data might be granted after review and approval of an investigator-initiated concept note by the principal investigator and data monitoring and oversight committee, and after the investigator signs a data access agreement.