Abstract

The partition region qsopAB of the Coxiella burnetii plasmid QpH1 was analyzed. Locus qsopA alone appears to fulfill the partitioning function; QsopA represses its own promoter 17-fold. Two partition-associated incompatibility sites were identified: incA in a 200-bp region covering the qsopA promoter and incB in the qsopB locus.

In order to be stably maintained at bacterial division, low-copy-number plasmids such as F (22) and prophage P1 (1) of Escherichia coli each carry a partition operon that encodes trans-acting protein A (e.g., SopA of the F plasmid and ParA of prophage P1) and protein B (SopB of the F plasmid and ParB of prophage P1) in addition to a cis-acting DNA region (sopC in F and parS in P1) which is located immediately downstream of the partition operon. Both trans- and cis-acting factors are essential for normal plasmid partition (13, 20, 23). Some other plasmids, such as plasmid pTAR of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, may carry one gene, instead of an operon, encoding the A protein (ParA), which is sufficient for a normal partitioning function (11). Expression of the protein A gene is subject to autoregulation in most plasmid partition systems, including F (14), P1 (9), and pTAR (10); protein B may significantly enhance protein A’s repressing activity, as demonstrated in the P1 system (9). Partitioning functions are closely related to the incompatibility of low-copy-number plasmids (10). Partition regions may contain one or more than one incompatibility (inc) sites in the cis-acting DNA regions (e.g., F and P1) or in the promoter regions (plasmids NR1 and pTAR) (29).

QpH1 is one of the low-copy-number plasmids isolated from the gram-negative, obligately intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii, the etiologic agent of Q fever in humans and other animals (17). Our previous studies have shown that QpH1 carries a partition region on a 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment (fragment C) which was able to stabilize a partition-defective mini-F plasmid (15). Sequence analysis and protein expression in E. coli revealed that fragment C specifies two proteins, QsopA and QsopB. The qsopAB region is a homolog to other active plasmid partitioning systems, including sopAB of the F plasmid (16). Here we have determined a minimal functional region on fragment C, analyzed possible autoregulation of qsopA and qsopB, and identified two inc sites. The data reported here will help us to gain an understanding of the mechanism by which these plasmids from a unique bacterial pathogen can be stably maintained.

The qsopA locus is sufficient for normal plasmid partitioning.

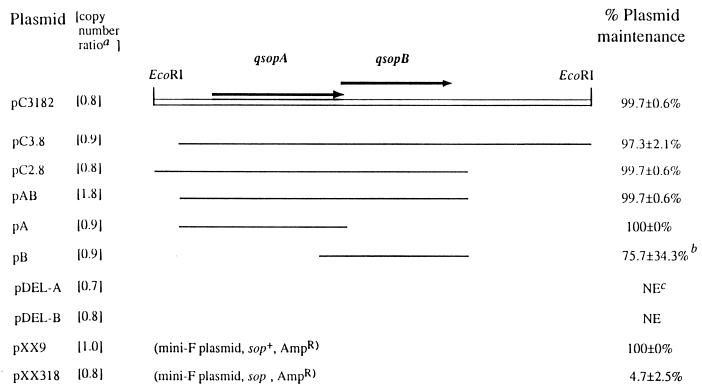

To localize the minimal region on fragment C encoding the full plasmid partitioning function, different regions of fragment C were subcloned into pXX318, a partition-defective (sop mutant) mini-F plasmid. The resulting pXX318 derivatives (Table 1) were examined for their abilities to complement the partitioning function of mini-F (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Genotype | Description and constructiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| For Fig. 1 or 3 | |||

| pXX9b | Aprsop+ | F replicon; mini-F derivative with intact partitioning function | 24 |

| pXX318b | Aprsop | A partition mutant of pXX9, carrying a deletion of the partition region | 24 |

| pC3182 | AprqsopAB+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment of QpH1 (fragment C) at the EcoRI site | Fig. 1 (see also reference 15) |

| pC3.8 | AprqsopAB+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 3.8-kb segment of fragment C at the EcoRI site; the segment was generated by PCR and carries a deletion of the first 225 nucleotides of the fragment | Fig. 1 |

| pC2.8 | AprqsopAB+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 2.8-kb segment of fragment C at the EcoRI site; the segment was generated by PCR and carries nucleotides 0 to 2833 | Fig. 1 (see also reference 15) |

| pAB | AprqsopAB+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 2.6-kb segment of fragment C at the EcoRI site; carries nucleotides 226 to 2833 from recombination between pC3.8 and pC2.8 | Fig. 1 |

| pA | AprqsopA+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 1.6-kb segment of fragment C at the EcoRI site; the segment was generated by PCR and carries nucleotides 226 to 1778 | Fig. 1 |

| pB | AprqsopB+ | pXX318 with insertion of a 1.5-kb segment of fragment C; the segment was generated by PCR and carries nucleotides 1336 to 2833 | Fig. 1 |

| pDEL-A | Aprsop | pA carrying an excision of the 1.6-kb EcoRI segment (the qsopA gene) | Fig. 1 |

| pDEL-B | Aprsop | pB carrying an excision of the 1.5-kb EcoRI segment (the qsopB gene) | Fig. 1 |

| For Fig. 2 | |||

| pΔUC19 | AprlacZα | ColE1 replicon; a pUC19 (31) derivative generated by SmaI-HincII digestion and religation to inactivate the lacZα gene of pUC19 | This study |

| pC4F | AprqsopAB+ | pUC19 with insertion of a 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment of QpH1 (fragment C) | 15 |

| pC1.9 | AprqsopA+ | pUC19 with insertion of a 1.9-kb EcoRI-KpnI segment of fragment C, covering the entire qsopA gene | 15 |

| pC1.6 | AprqsopB+ | pUC19 with insertion of a 1.6-kb HindIII segment of fragment C, covering the entire qsopB gene | 16 |

| pZL11 | Apr Cmr | p15A replicon (see the text for the construction) | This study |

| p30-8 | Apr KnrqsopA-phoA+ | QpH1 DNA::TnphoA containing a qsopA-phoA fusion at codon 63 of qsopA | 15 |

| pZL308 | CmrqsopA-phoA+ | pZL11 with insertion of a 4.1-kb BamHI-PstI segment containing the qsopA-phoA fusion gene of p30-8 | This study |

| pZL308+11 | CmrqsopA-phoA+ | pZL308 with insertion of a 2.4-kb noncoding PstI DNA segment at the 3′ end of TnphoA at the PstI site, in order for pZL308 to have the same 3′ end of the phoA gene as the lacZ gene in TnphoA′-4c, for in vivo recombinational switching (see below) | This study |

| pZL308+11λ2 | Cmr KnrqsopA-lacZ+ | pZL308+11::TnphoA′-4; the phoA gene in pZL308+11 was switched into lacZ after in vivo recombination with TnphoA′-4 (30), resulting in a qsopA-lacZ fusion gene (see below for a modified method) | This study |

| pZLΔ(308+11λ2) | CmrqsopA-lacZ | pZL308+11λ2 carrying a BamHI-BglII deletion of the qsopA-lacZ fusion gene | This study |

| pC1.6-TnphoA′-4-28 | Apr KnrqsopB-lacZ+ | pC1.6::TnphoA′-4; E. coli DH5α cells carrying pC1.6, after being infected with TnphoA′-4, were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by shaking at 37°C at 225 rpm for 30 min, before being plated out on LB plates (21) containing antibiotics and X-Gald (19) | This study |

| pZLqsopB-lacZ28 | KnrqsopB-lacZ+ | pZL11 with insertion of a 5.1-kb SmaI segment at its ScaI site; the segment was cut out from pC1.6-TnphoA′-4-28 and contained the qsopB-lacZ+ fusion gene | This study |

| pZLΔ(qsopB-lacZ28) | KnrqsopB-lacZ | pZLqsopB-lacZ28 derivative, carrying a deletion of a 3.8 kb HindIII fragment covering the entire qsopB-lacZ fusion gene | This study |

| For Fig. 3, pBRFCs | Tcr | pBR322 (4) derivatives carrying various segments of fragment C, generated by DNA recombination | Fig. 3 |

For those constructed with PCR-generated DNAs, the PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Murdock Molecular Biology Facility, University of Montana; for those produced by TnphoA′-4 mutagenesis or in vivo recombination, the DNA hybrids produced were all confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Kindly provided by Sota Hiraga, Kumamoto University School of Medicine, Kumamoto 862-0976, Japan.

This bacteriophage was obtained from Kevin P. Bertrand’s laboratory, Washington State University.

X-Gal, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside.

FIG. 1.

Localization on fragment C of a minimal region required for a normal plasmid partitioning function in HB101. Plasmid pXX9 is a partition-positive control, and pXX318 is a negative control. Different regions of fragment C were subcloned into pXX318, a partition (sop)-defective mini-F plasmid, in order to evaluate their abilities to complement the plasmid partitioning function by examining the percent maintenance of the resulting pXX318 derivative. The method has been described previously (15), except that the percentage here indicates plasmid retention (5) instead of plasmid loss. The orientations of the fragment C DNA segments were all the same in the pXX318 derivatives (see Table 1 for more information). The names and relative copy numbers of the plasmids are given on the left, and their fragment C regions are shown in the middle. The percent maintenance of each plasmid after 50 generations of nonselective exponential growth is given on the right as means ± standard deviations from three independent measurements. Arrows, qsopA and qsopB ORFs; open bar, the 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment of plasmid QpH1 (fragment C); lines, different regions of fragment C; a, relative to pXX9, which is taken as the standard and assumed to have a copy number of 1; b, six independent measurements; c, NE, not examined.

Deletion of either the upstream (225 bp; pC3.8) or downstream (1.3 kb; pC2.8) region of qsopAB did not influence the plasmid maintenance (Fig. 1), indicating that these DNA regions do not contribute to the partitioning function. These results were further verified by showing that plasmid pAB, which carried deletions of both the upstream and downstream regions, had complete plasmid partitioning function. A plasmid with further deletion (pA) of the qsopB locus retained the plasmid maintenance function intact (100% versus 99.7% for pAB), while deletion (pB) of the qsopA locus destabilized the plasmid maintenance (75.7% versus 99.7% for pAB [Fig. 1]). Thus the qsopA locus (nucleotides 266 to 1778 of fragment C) appeared to have full partitioning function. The qsopB locus alone was inefficient and displayed a weak partitioning function, which, however, was still significantly higher than that of the negative control (75.7% versus 4.7% for pXX318) (Fig. 1). The amino acid sequence of QsopA has 58% similarity to that of SopA of the F plasmid but only 47% similarity to ParA of the A. tumefaciens plasmid pTAR (16). However, unlike SopA, QsopA does not require QsopB for normal partitioning function, a situation similar to that of pTAR, which encodes only one protein sufficient for normal partitioning function (11).

To confirm that stabilization of pXX318 by insertion of the qsopAB locus was not due to changes in plasmid copy numbers, the plasmid copy number relative to that of pXX9 was determined for each plasmid by comparing the DNA concentrations of pXX9 and pXX318 or each pXX318 derivative. Overnight cultures of E. coli HB101 cells carrying appropriate plasmids in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (21) with ampicillin were subcultured at a dilution of 1:100 and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.7 in LB broth in the absence of ampicillin. The OD600 ml (OD600 value multiplied by the culture volume in milliliters) of each bacterial suspension was determined, and identical OD600 ml amounts (approximately 3) of HB101/pXX9 and different culture (carrying a different plasmid) were mixed. The plasmid DNAs were isolated from each mixture by alkaline lysis, followed by restriction digestion (26). The DNAs were separated by gel electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide for photography, DNA bands on the photographs were subjected to densitometric studies, and the relative plasmid copy numbers were calculated. In this study, pXX9 was assumed to have a wild-type copy number of 1, and the copy number was determined to be between 0.7 and 0.9 for pXX318 and all pXX318 derivatives except pAB (Fig. 1). Plasmid pAB had an average copy number (1.8) almost twice that of pXX9, consistent with the idea of an insertion-caused increase in plasmid copy number. In pDEL-A and pDEL-B, excisions of QpH1 DNAs from pA and pB, respectively, did not affect the copy numbers. These copy number data suggested that the increased stability of pA or pB was not due to changes in copy number.

Autoregulation of the qsopA and qsopB promoters.

To look at possible autoregulation of qsopA or qsopB expression in E. coli, an expression plasmid is required that carries a qsopA- or qsopB-reporter fusion gene in which the reporter gene is under the control of the qsopA or qsopB promoter. If expression of qsopA or qsopB is autoregulated, the presence of QsopA or QsopB would influence the fusion gene expression level, vice versa. We used the β-galactosidase gene (lacZ) as the reporter.

We constructed a medium-copy-number expression vector, called pZL11 (Table 1). Plasmid vector pACYC177 (7) was selected to start with because it is a medium-copy-number replicon (approximately 22 copies per chromosome) which is derived from the small cryptic plasmid P15A (8), and it carries ampicillin (Apr) and kanamycin (Knr) resistance genes that can be utilized and relatively few known unnecessary promoters that are undesirable. Besides the promoters of the replication origin and of the antibiotic resistance genes, two undesirable promoters were found located around the Knr gene and on a 1.4-kb HaeII fragment (12, 25, 27). In order to remove these two promoters, a 1.1-kb DNA fragment carrying a chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) gene but no undesirable promoters was copied from pACYC184 (7) by PCR using this vector as the template. Replacement of the 1.4-kb HaeII fragment of pACYC177 with the 1.1-kb PCR product resulted in pZL11. In this expression vector, the promoters of the Apr and Cmr genes are both directed towards the replication origin, and the region between these two promoters is not influenced by any known promoters in the vector and is thus suitable for carrying the qsopA- or qsopB-lacZ reporter gene. Expression plasmids pZL308+11λ2 (sopA-lacZ) and pZLqsopB-lacZ28 (qsopB-lacZ) were prepared by taking advantage of TnphoA′-4 mutagenesis and in vivo recombination (30) (Table 1).

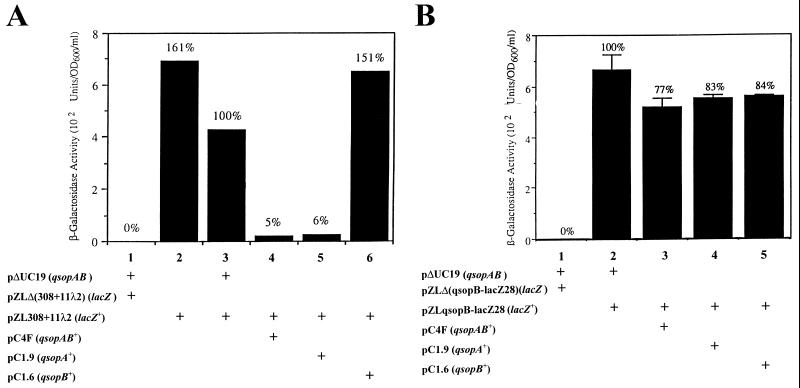

Transformation of E. coli DH5α containing pZL308+11λ2 (carrying the reporter gene qsopA-lacZ) with pUC19 derivatives carrying qsopAB or one of the qsopA and qsopB genes (Table 1) and examination of the β-galactosidase activity levels of these cotransformants allowed an evaluation of autoregulation of expression from the qsopA promoter. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 2A. The negative control did not display any enzymatic activity (Fig. 2A, lane 1). The presence of pΔUC19 reduced the β-galactosidase activity level by 38% (Fig. 2A; compare lanes 2 and 3). The presence of either pC4F (qsopAB+) (Fig. 2A, lane 4) or pC1.9 (qsopA+) (lane 5) reduced the enzyme activity to 5 or 6% of the activity of the qsopAB-negative control (pΔUC19) (lane 3), respectively. The presence of plasmid pC1.6 (qsopB+) (Fig. 2A, lane 6) did not decrease the reporter expression. These data meant that by using qsopA-lacZ as a reporter gene, the QsopA and QsopB proteins together repressed fusion protein expression by a factor of almost 20; the QsopA protein alone still repressed expression by a factor of 17, but QsopB did not repress expression at all. QsopB might slightly enhance the repressing activity of QsopA, and conceivably, this enhancement could become more significant if either QsopA or QsopB or both are expressed from low-copy-number plasmids or are present at lower concentrations. Autoregulation of qsopA by both QsopA and QsopB is quite similar to those observed for the P1 (9), pTAR (11), and NR1 (28) systems.

FIG. 2.

Autoregulation of the qsopA (A) and qsopB (B) promoters. (A) The experiments were repeated two more times, and the results remained consistent. (B) Each value was the mean from three independent measurements. Error bars, standard deviations. E. coli DH5α cells harboring one or two (as indicated) appropriate plasmids were measured for β-galactosidase activity. Simply, β-galactosidase (26) activity was measured in cells treated with CHCl3 and sodium dodecyl sulfate according to the published procedure. One unit of β-galactosidase was defined as hydrolyzing 1.0 μmol of o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside to o-nitrophenol and d-galactose per min per ml per OD600 unit of cell culture at pH 7.5. The genotype for each plasmid is shown in parentheses (see Table 1 for more information).

To evaluate the possible autoregulation of qsopB expression, plasmid pZLqsopB-lacZ28 (carrying the reporter gene qsopB-lacZ) was cotransformed into DH5α cells, again along with the pUC19 derivatives (Table 1). The results shown in Fig. 2B demonstrate that both the QsopA (lane 4) and QsopB (lane 5) proteins had equal, but weak, abilities to repress expression from the qsopB promoter. The QsopA and QsopB proteins together (Fig. 2B, lane 3) reduced β-galactosidase activity by 23% (P < 0.05), a reduction apparently, but not statistically (P > 0.05), greater than those for the individual proteins (16 to 17%) (Fig. 2B). Plasmid pΔUC19 was a negative control for pUC19 derivatives (Fig. 2B, lane 1); plasmid pZLΔ(qsopB-lacZ28) was a negative control for the reporter plasmid (lane 2).

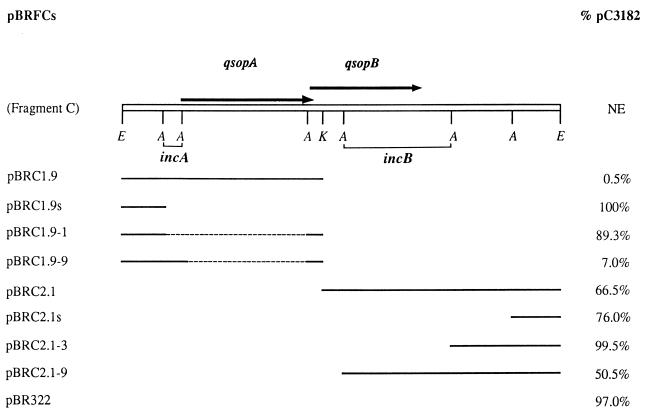

Localization of partition-associated incompatibility sites on fragment C.

Two different plasmids carrying the same incompatibility (inc) site(s) in a single host cell will discriminate against each other, and the disadvantaged one (for example, the one with a lower copy number) will be eliminated from the cell line (reviewed in reference 3). In an effort to identify incompatibility (inc) sites on fragment C, different segments of fragment C were subcloned into the plasmid vector pBR322, producing serial plasmids designated pBRFCs (Fig. 3; Table 1). We then looked at which of the derivatives display incompatibility against pC3182, which carries the entire fragment C, by cotransforming each of the derivatives together with pC3182 into the same HB101 cells and examining pC3182 maintenance. Cells containing a pBRFC with an inc site(s) would lose pC3182, and cells containing a pBRFC without an inc site(s) would retain pC3182.

FIG. 3.

Localization of inc sites on fragment C. The two identified inc sites, incA and incB, are delineated below fragment C. HB101 cells harboring plasmid pC3182 were cotransformed with one of the pBRFCs (listed at the left) (see Table 1), which carried different regions (indicated by solid lines) of fragment C. The resulting cotransformants were examined for percent maintenance (shown on the right) of plasmid pC3182 after 64 generations of nonselective exponential growth. Arrows, positions and orientations of the qsopA and qsopB genes; open bar, fragment C; NE, not examined; dashed lines, deletions. Restriction sites: E, EcoRI; A, AseI; K, KpnI. Each value was derived from an examination of 400 colonies.

Based on the significant difference in percent pC3182 retention between the coexisting plasmids pBRC1.9-1 (89.3%) and pBRC1.9-9 (7.0%) (see Fig. 3 for plasmid constructs and data), it appeared that there was a very strong inc site within a 200-bp AseI region (coordinates 393 to 597) that covered the promoter region of the qsopA gene. In addition, there was another (or at least one), weak inc site that was located on a 980-bp AseI region (between the fourth and the fifth AseI sites, coordinates 2020 to 3003), as suggested by comparison between pBRC2.1-3 (99.5% pC3182 retention) and pBRC2.1-9 (50.5%). This AseI region covered the majority of the qsopB open reading frame (ORF) and 237 bp downstream of qsopB. We termed the first site incA and the second incB (Fig. 3). In comparison with plasmid pBRC2.1-3, which did not carry any inc activity, for unknown reasons plasmid pBRC2.1s displayed some incompatibility activity even though it carried a smaller DNA segment.

Localization of a strong inc site in the promoter region of qsopA suggests that the structure of qsopA is similar to that of the pTAR parA of A. tumefaciens rather than the F sopA of E. coli. Plasmid pTAR carries parA, which is sufficient to stabilize the plasmid, and does not carry the gene for protein B. The promoter region of this parA gene contains an array of 12 7-bp AT-rich sequences and has four activities: it serves (i) for initiation of transcription, (ii) as an inc site, and (iii) as a cis-acting recognition site, and (iv) it is involved in autoregulation (15). Similarly, the qsopA promoter region has (i) an AT-rich sequence, the imperfect palindrome (16), (ii) a promoter, (iii) involvement in autoregulation, and (iv) the incA site. Thus, incA might be a cis-acting recognition site. Since qsopA alone is sufficient for normal plasmid partitioning, one question would be, why does plasmid QpH1 need qsopB, which displays a certain partitioning function (pB in Fig. 1)? The answer to that remains cryptic. If an inc site is a cis-acting site, the putative cis-acting site of the qsopB locus can be located, at least partially, on the downstream 67-bp region (coordinates 2767 to 2833), according to inc location studies (Fig. 3). If this is not the case, the inc site(s) responsible for the incompatibility activity displayed by the qsopB locus could reside within the qsopB ORF and/or near the stop codon of the qsopB ORF, a situation similar to that of the F plasmid, where both the sopB ORF and the sopC site display incompatibility activities (22).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. L. Kahn for stimulating discussions during these studies and S. Gottesman for critical review. The software used for DNA homology analysis is part of the VADMS Center, a campuswide computer resource at Washington State University. We are grateful to the VADMS Center for convenient access to computerized analysis.

This work was supported by grant AI20190 (to L.P.M.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIAID).

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Louis P. Mallavia for his excellence in teaching and research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeles A, Friedman S A, Austin S J. Partition of unit-copy mini-plasmids to daughter cells. III. The DNA sequence and functional organization of the P1 partition region. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alton N K, Vapnek D. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the chloramphenicol resistance transposon Tn9. Nature (London) 1979;282:864–869. doi: 10.1038/282864a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin S, Nordström K. Partition-mediated incompatibility of bacterial plasmids. Cell. 1990;60:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balbás P, Soberón X, Merino E, Zurita M, Lomeli H, Valle F, Flores N, Bolivar F. Plasmid vector pBR322 and its special-purpose derivatives—a review. Gene. 1986;50:3–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biek D P, Strings J. Partition functions of mini-F affect plasmid DNA topology in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:388–400. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boquet P L, Manoil C, Beckwith J. Use of TnphoA to detect genes for exported proteins in Escherichia coli: identification of the plasmid-encoded gene for a periplasmic acid phosphatase. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1663–1669. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1663-1669.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cozzarelli N R, Kelly R B, Kornberg A. A minute circular DNA from E. coli 15*. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;60:992–999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.60.3.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman S A, Austin S J. The P1 plasmid-partition system synthesizes two essential proteins from an autoregulated operon. Plasmid. 1988;19:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(88)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabant P, Newnham P, Taylor D, Couturier M. Isolation and location of the R27 map of two replicons and an incompatibility determinant specific for IncHI1 plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7697–7701. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7697-7701.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallie D R, Kado C I. Agrobacterium tumefaciens pTAR parA promoter region involved in autoregulation, incompatibility and plasmid partitioning. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:465–478. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heffron F, McCarthy B J, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. DNA sequence analysis of the transposon Tn3: three genes and three sites involved in transposition of Tn3. Cell. 1979;18:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helsberg M, Eichenlaub R. Twelve 43-base-pair repeats map in a cis-acting region essential for partition of plasmid mini-F. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:1043–1045. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.1043-1045.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano M, Mori H, Onogi T, Yamazoe M, Niki H, Ogura T, Hiraga S. Autoregulation of the partition genes of the mini-F plasmid and the intracellular localization of their products in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:392–403. doi: 10.1007/s004380050663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Z, Mallavia L P. Identification of a partition region carried by the plasmid QpH1 of Coxiella burnetii. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Z, Mallavia L P. The partition region of plasmid QpH1 is a member of the family of two trans-acting factors as implied by sequence analysis. Gene. 1995;160:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallavia L P, Samuel J E, Frazier M E. The genetics of Coxiella burnetii: etiologic agent of Q fever and chronic endocarditis. In: Williams J C, Thompson H A, editors. Q Fever: the biology of Coxiella burnetii. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 259–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoil C, Beckwith J. TnphoA: a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8129–8133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin K A, Friedman S A, Austin S J. The partition site of the P1 plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8544–8547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori H, Kondo A, Ohshima A, Ogura T, Hiraga S. Structure and function of the F plasmid genes essential for partitioning. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogura T, Hiraga S. Partition mechanism of F plasmid: two plasmid gene-encoded products and a cis-acting region are involved in partition. Cell. 1983;32:351–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogura T, Hiraga S. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4784–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oka A, Sugisaki H, Takanami M. Nucleotide sequence of the kanamycin resistance transposon Tn903. J Mol Biol. 1981;147:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selzer G, Som T, Itoh T, Tomizawa J-I. The origin of replication of plasmid p15A and comparative studies on the nucleotide sequences around the origin of related plasmids. Cell. 1983;32:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabuchi A, Min Y-N, Womble D D, Rownd R H. Autoregulation of the stability operon of IncFII plasmid NR1. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7629–7634. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7629-7634.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams D R, Thomas C M. Active partitioning of bacterial plasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1–16. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilmes-Riesenberg M R, Wanner B L. TnphoA and TnphoA′ elements for making and switching fusions for study of transcription, translation, and cell surface localization. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4558–4575. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4558-4575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]