Abstract

Background:

Surrogate decision makers are required to make difficult end-of-life decisions with little preparation. Little is known about what surrogates may need to adequately prepare for their role, and few resources exist to prepare them.

Objective:

To explore experiences and advice from surrogates about how best to prepare for the surrogate role.

Design:

Semistructured focus groups.

Setting/Participants:

Sixty-nine participants were recruited through convenience sampling in San Francisco area hospitals, cancer support groups, and community centers for 13 focus groups. Surrogates were included if they were 18 years of age or older and reported having made medical decisions for others.

Measurements:

Qualitative thematic content analysis.

Results:

Forty participants reported making surrogate decisions for others: 6 were Spanish speaking, 22 were women, 16 were Black American, 11 Asian/Pacific Islander, 6 Latinx, and 7 White; 9 had limited health literacy. The majority (29, 73%) emphasized the importance of advance care planning (ACP) and expressed the desire for additional guidance. Five themes and advice were identified: (1) lack of, but needing, surrogates' own preparation and guidance (2) initiate ACP conversations, (3) learn patient's values and preferences, (4) communicate with clinicians and advocate for patients, and (5) make informed surrogate decisions.

Conclusion:

Experienced surrogate decision makers emphasized the importance of ACP and advised that surrogates need their own preparation to initiate ACP conversations, learn patients' values, advocate for patients, and make informed surrogate decisions. Future interventions should address these preparation topics to ease surrogate burden and decrease disparities in surrogate decision making.

Keywords: advance care planning, medical decision making, proxy, qualitative, serious illness

Introduction

When individuals lose the capacity to make decisions about their own medical care, such decisions regularly fall upon the patient's family members or friends. Surrogate decision making is required in up to 76% of cases at the end of life, making it a vital component of how care is delivered and how patients may experience their final stages of life.1,2 However, in many cases surrogates are afforded little preparation or guidance resulting in surrogate distress.3,4

Ideally, surrogate decision making would be aided by prior advance care planning (ACP) discussions and, if appropriate, documentation of patients' wishes. ACP is a process wherein patients articulate their goals, values, and preferences for medical care.5 Unfortunately, previous studies have reported that less than one in four older adults with serious illness have engaged in ACP discussions with their potential surrogate decision maker.3 Consequently, less than one in four surrogates felt that they understood the patient's values and preferences regarding various health states and medical interventions.4

Surrogates are expected to have a deep understanding of patients' preferences and values to guide complex decision making. However, studies have shown that patients prefer surrogates to respond dynamically to medical circumstances, rather than only adhere to patients' previously expressed wishes.6–8 This makes surrogate decision making unique and complex as surrogates are tasked with balancing previous stated wishes, what may be known about patients' current preferences using substituted judgment, and what may be in the patient's best interest at the time of the decision.9–12

As patients' needs and contexts change, surrogates undertake many complex responsibilities, such as learning and knowing the patient's wishes, extrapolating those wishes to new circumstances and decisions, and advocating and communicating with medical providers. As a result, surrogates often report anxiety, depression, and distress, which has the potential to influence medical decisions, potentially at the cost of the patient's preferences and best interests.13,14

Although much is expected from surrogates, few ACP resources exist to prepare them for making medical decisions.15 In addition, despite known health disparities in ACP, only a few prior qualitative studies of surrogates' experiences have included participants from diverse demographic backgrounds or elicited advice from experienced surrogates about how best to prepare them for their role.13,15–19

Therefore, we explored the experiences of English- and Spanish-speaking surrogate decision makers and the advice they would give to others with the goal of informing future interventions to prepare surrogates for their role.

Methods

Setting and participants

This is a secondary analysis of qualitative focus group data designed to explore participants' ACP experiences, as previously described.20–22 This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Participants were recruited through fliers and convenience sampling from San Francisco hospitals, cancer support groups, and community centers. Potential participants were initially divided into two groups. The “patient” group consisted of participants aged 65 years and older who stated that they had made medical decisions for themselves. The “surrogate” group consisted of participants aged 18 years and older who stated that they had made medical decisions for others. Six groups were initially designated as “surrogate” focus groups and seven as “patient” focus groups, including three Spanish-speaking groups.

During the course of the focus groups, “patients” often spoke from the perspective of the “surrogate,” as many participants had experienced both roles. Data regarding surrogate experiences were, therefore, included from both groups. Participants were excluded if they reported that they did not speak English or Spanish, were deaf or blind, did not possess a telephone, or, through screening, were found to have had moderately impaired cognition on the telephone interview cognitive status questionnaire.23

Studies have shown that disparities in ACP exist among different racial and ethnic groups, particularly with lower ACP rates among Latinx and Black American populations.24–26 Given these disparities, we asked participants about their self-identified race and ethnicity, and conducted separate focus groups for individuals who self-identified as Asian-Pacific Islander, Latinx, Black American, or White.

Procedures

Thirteen semistructured focus groups were conducted; the focus group outline was previously published.20 The topics discussed included personal experiences with medical decision making and opinions about decision making based on vignettes about serious illness.20 In a unique aspect of this study, participants were asked about the “advice they would give others” in similar situations.

Data analysis

As previously described, many individuals in the “patient” groups, organically and unprompted, discussed surrogate decision-making experiences and provided advice for other surrogates. In this study, all comments regarding surrogate decision making were included in the analysis from all 13 groups, regardless of initial group designation.20,22 All groups were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and, for Spanish-speaking groups, translated to English. Transcripts were reviewed by one author to extract quotes from surrogate perspectives for qualitative thematic content analysis.27

Two authors then independently coded all surrogate-specific data and developed a codebook. The coding scheme was then refined through serial review of the transcripts using the constant comparative method.28 To ensure trustworthiness, we used a standard focus group outline and created an audit trail for coding. Overarching themes were identified, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. There is no overlap of this analysis with prior publications. However, if portions of quotes had been published in the context of unrelated research questions, we appropriately attributed the publication.

Results

Sixty-nine participants took part in 13 focus groups (Table 1),20,21 and 40 (58%) reported having made a surrogate decision. Of the 40 participants, 16 (40%) self-reported as Black American, 11 (27.5%) as Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 (15%) as Latinx or Hispanic, and 7 (17%) as White; 6 (15%) were Spanish speaking; 22 (55%) were women; and 9 (22%) had limited health literacy. Among the 40 experienced surrogate decision makers, 29 (73%) emphasized the importance of ACP and expressed the desire for additional preparation, guidance, and resources.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Characteristics | All focus group participants (n = 69) | Participants with surrogate experience (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean, age ± SD (range) | 69 ± 14 (33–89) | 63 ± 13.5 (33–88) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 36 (52) | 18 (45) |

| Female | 33 (48) | 22 (55) |

| Language, n (%) | ||

| English speaking | 56 (81) | 34 (85) |

| Spanish speaking | 13 (19) | 6 (15) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 18 (26) | 11 (27.5) |

| Black American | 20 (29) | 16 (40) |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 13 (19) | 6 (15) |

| White/Caucasian | 18 (26) | 7 (17.5) |

| Self-reported health status, n (%) | ||

| Excellent to good | 44 (64) | 26 (65) |

| Fair to poor | 25 (36) | 14 (35) |

| Self-reported health literacy, n (%) | ||

| Limited health literacy | 15 (22) | 9 (22.5) |

SD, standard deviation.

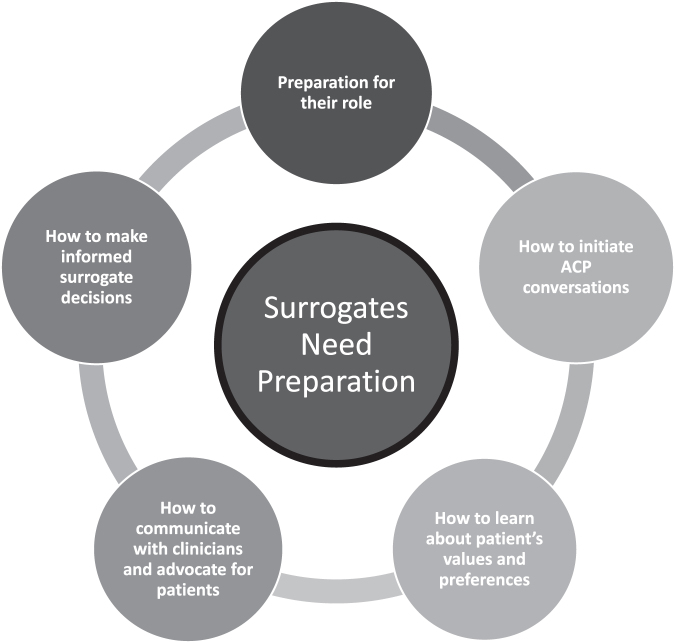

Five themes were identified including (1) lack of preparation and the advice that surrogates need their own preparation and guidance to (2) initiate ACP conversations, (3) learn about patient's values and preferences, (4) communicate with clinicians and advocate for patients, and (5) make informed surrogate decisions. See Table 2 for selected quotes and associated demographics. See Supplementary Table S1 for all quotes and associated demographics.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Needs of Culturally and Ethnically Diverse Surrogate Decision Makers, Selected Quotes from Text

| Surrogate needs | Gender | Race/ethnicity | Age (years) | Surrogate quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of preparation and importance of ACP | Woman | Black American | 63 | “I am on that advance directive, DPOA. He did that seven years ago and I never even knew about the papers… He surprised me.” (Q1) |

| Woman | Black American | 59 | “The advance directive helps because everything's in black and white and when the person made a decision prior, they, you know, had a clear mind.” (Q5) | |

| Challenges initiating ACP conversations | Woman | Black America | 58 | “She [my mother] got frustrated. She didn't want to talk about it no more.” (Q7) |

| Woman | Asian American | 61 | “We didn't brood. We don't talk about dying; we talk about the future.” (Q8) | |

| Needing guidance to learn patient's values and preferences | Man | Asian American | 81 | “I want to know what the framework is. What do you look at first and what is the last consideration? You know, where does the family come into this and acknowledge, “Yes, let's go through with this.” (Q10) |

| Man | Asian American | 60 | “I managed to talk to my father a few years before about a DNR and he said no and, you know, that was the extent of how much I knew what his wishes were. The other stuff we were guessing at.” (Q11)17 | |

| Needing guidance to communicate with clinicians and advocating choices | Man | White | 80 | “Having a good doctor who saw the value of counseling was important because I met so many doctors that tend to just tell you and then walk out of the room. They are very impatient.” (Q13) |

| Woman | Black American | 58 | “And the thing with advance directives is that they can change at any time. But somebody needs to know. Somebody needs to be close enough to you as to say that, ‘No, she changed her mind about that. So, I don't think that's what she wants’.” (Q14)17 | |

| Needing guidance about how to make surrogate decisions | Man | Latinx | 65 | “To see [my son], his siblings, and my wife suffering, it was too hard. The decision [to remove my son's life support] was made because we couldn't do anything else” (Q17) |

| Woman | Black American | 71 | “My husband, because of how I feel about him, I may deviate depending on what's going on at that time.” (Q20) |

ACP, advance care planning; DNR, do not resuscitate; DPOA, durable power of attorney.

-

1.

Lack of preparation and importance of ACP

Many participants described surrogacy as a role into which they or others were thrust unexpectedly or without notice: “I am on [my father's] advanced directive, DPOA [Durable Power of Attorney]. I never knew…he surprised me.” Examples of being thrust into the surrogate role included circumstances of acute medical crises such as a stroke or a car accident, or instances wherein there was a rapid change in the patient's health due to a pre-existing but noncritical illness, such as sickle-cell anemia. In multiple instances participants described not being aware of their role as a surrogate until being contacted by the health care team: “I didn't know I was going to be put in that position until the hospital called me.”

Participants emphasized the importance of ACP for surrogates, especially as it related to the difficulty of their experience. Several surrogates believed their experience would have been improved had they engaged in ACP discussions with the patient before such decisions were necessary: “What we should have done was…sit down with the family and say, ‘this is what Mom and Dad want’.”17 In instances when surrogates had participated in ACP activities with the patient before making medical decisions, they reported that the surrogate role was easier to navigate: “we had it all spelled out. It made it a lot easier.”

In these cases, surrogates endorsed a clear understanding of the patient's values and preferences for medical care and felt confident that their decisions for the patient's care were aligned with what the patient would have wanted: “the advance directive helps [me make decisions] because everything's in black and white.”

-

2.

Needing guidance to initiate ACP conversations

Many surrogates described difficulty initiating ACP conversations with patients, friends, or family, with some stating that they encountered resistance: “[My mother] didn't want to talk about it. It's hard when…they don't want to open up.” Surrogates felt that they did not know how to begin ACP conversations or how to frame the conversations. This prevented them from engaging in discussions about ACP topics, “[My mother] got frustrated. She didn't want to talk about [ACP] no more…” One surrogate who had received some guidance in conducting ACP conversations shared her advice on framing these discussions and spoke about how this approach facilitated her role as a surrogate: “We didn't brood. We don't talk about dying; we talk about the future.”

-

3.

Needing guidance to learn patient's values and preferences

-

Participants emphasized the importance of understanding the values and preferences of the person they would be making decisions for: “I, as a child, would feel better knowing…that I did the best I can with all the knowledge I could gather.” However, some surrogates were uncertain about how to navigate these conversations and did not know what questions to ask to understand the patient's values and preferences for medical care: “I want to know what the framework is [for these discussions]. What do you look at first and what is the last consideration?” In some instances when surrogates had previously engaged in ACP conversations, some reported that the conversation still did not adequately prepare them for new or complex decisions that they later encountered.

In such cases, surrogates emphasized the value in engaging in these conversations to gather the information that they needed for their role, and how the lack of guidance prevented these conversations from going as well as they could have: “I managed to talk to my father about a DNR…that was the extent of how much I knew what his wishes were. The other stuff we were guessing at…or whatever.”20

Many participants also felt forced to make medical decisions without a clear understanding of what the patient would have wanted, resulting in family discord. Experienced surrogates spoke of the importance of clarifying patient's wishes, and described how ambiguity around patients' wishes disrupted or complicated the surrogate process: “Our mother had a [DNR] in place. We just didn't know that, so that was difficult. [Instead, we began] making medical decisions, how to care for her at the end of her life. There may have been two of us that wanted to make Mom comfortable and then two of us to say ‘no’.”

-

4.

Needing guidance to communicate with clinicians and advocating choices

Surrogates reported that difficulty communicating with clinical teams made it difficult to advocate on behalf of the patient. They highlighted the importance of better preparation for communication and described how a lack of communication complicated their role: “I met so many doctors that tend to just tell you [what to do] and then walk out of the room. They are very impatient.” Many surrogates emphasized the importance of advocating on behalf of the patient's preferences, but often expressed reluctance in communicating this to the clinical team: “Somebody needs to know…to say, ‘No, I don't think that's what she wants’.”29

In some cases, surrogates felt that their opinion did not align with the recommendations of the clinical team and were uncomfortable expressing this concern or felt that the best option was to default to clinician recommendations: “I wanted to try my best to keep him alive, but the doctors say ‘Oh, at that age, if you put the tube in you will hurt him even more.”

-

5.

Needing guidance about how to make informed surrogate decisions

Surrogates felt that one of the most difficult aspects of their role was navigating the decision-making process, including being asked to make a treatment decision without any additional guidance: “I had to make medical decisions for my husband. I didn't know what to do. Doctors say they need me to make a decision right now. I didn't know my answer.” For some surrogates, this lack of guidance led them to default to decisions regarding treatments and therapies that prolonged the suffering of their loved ones without the understanding that alternative end-of-life options existed: “To see [my son], his siblings, and my wife suffering, it was too hard.

The decision [to remove my son's life support] was made because we couldn't do anything else.” Surrogates talked about the importance of receiving guidance when navigating complicated medical decisions, describing that they often reached out to family, friends, or clinicians for help: “My husband left the final decisions to me and I prayed on it; I spoke with people in the medical profession, my mom, nurse friends, to explain what the DNR meant. It was a very difficult decision.”

In recalling their decision-making process, most surrogates who had not previously discussed ACP with the patient described using their own personal feelings about medical care or quality of life to inform their decision: “I wasn't ready to let him go, and I thought of all the ways that I could keep him alive.” Even in instances when ACP discussions had taken place, some surrogates described using their own personal feelings and preferences about medical care to fill in the gaps in their direct understanding of the patient's values or preferences: “my husband, because of how I feel about him, I may deviate [from his expressed preferences] depending on what's going on at the time.”

Discussion

In this study of experienced surrogate decision makers from diverse demographic backgrounds, the majority described the importance of ACP before patients losing their decision-making capacity. This study also added to the literature by eliciting advice from experienced surrogates about how others can best prepare for the role, specifically that preparation is needed to initiate ACP conversations with patients, to learn about patients' values and preferences, to communicate with clinicians and advocate on the patient's behalf, and to make informed surrogate decisions.

Surrogates emphasized the importance of ACP when making medical decisions.18,22 Our results were similar to other studies wherein surrogates felt their knowledge of patients' preferences and values was often incomplete and inadequate.18 Prior research has also demonstrated discordance between surrogates' understanding of the goals of care and the medical treatments documented in the medical record, reflecting insufficient ACP conversations before surrogacy.30

Surrogates in this study advised that the decision-making process was easier with early, substantive, and direct communication with patients regarding their values and preferences. Conversely, surrogates associated difficult decision-making processes with lack of, or low-quality, communication with patients or clinicians.13,31 Indeed, prior research has validated this advice by demonstrating that higher quality communication between surrogates and patients, and between surrogates and clinicians, improves both patient and surrogate outcomes.13,31–33

Our study also highlights the complexities in how surrogates from diverse backgrounds approach medical decisions. Similar to previous studies, surrogates in our study reported using a multitude of factors when making medical decisions.10,15,18,21,34 Whereas previous studies have focused on surrogate barriers, this study focused on surrogates' advice and identified specific areas where guidance and support for surrogates have been more helpful or are most needed. The advice most often focused on the importance of communication and learning patients' wishes and goals.

Furthermore, the nuances of substituted judgment and best interests are reinforced in this study, where considerations of culture, family dynamics, and individual surrogate–patient relationships add complexity to the surrogate role.10 Although the use of patients' prior wishes, substituted judgment, and best interests has historically been viewed as hierarchical, more recent guidance characterizes these components as dynamic and variably contributory based on the individual context.35–37 Many of the surrogates in this study supplemented, or even substituted, the patient's expressed wishes with the surrogate's own personal experiences, family consensus, or interpretation and extrapolation of prior discussions with the patient.

This study builds on prior research by incorporating the perspectives of experienced surrogates from diverse demographic backgrounds, and also by eliciting surrogates' advice for others.19 Surrogates identified themes that reflect targets for better preparation within the decision-making process, thereby illustrating specific targets for surrogate ACP interventions (Fig. 1). Interventions to prepare culturally diverse surrogate decision makers are lacking. Through the cultural adaptation process, the results of this and other studies can be used to create interventions that will meet the needs of culturally and ethnically diverse populations.13,15,19,38

FIG. 1.

The self-reported preparation needs of culturally and ethnically diverse surrogate decision makers.

There are some limitations of this study. Participant recruitment was limited to convenience sampling within a single geographic region in northern California, therefore, sampling bias is possible. In addition, the qualitative nature of this study and the size of the cohort do not allow for association of themes by individual demographics. Furthermore, the focus group format may have limited our ability to capture all contributing factors within the surrogate decision-making process.

Conclusion

Experienced surrogate decisions makers consider ACP to be crucially important and advise that surrogates need better preparation and guidance to initiate ACP conversations with their family and friends, to learn patients' values and preferences, to communicate with medical providers and advocate on behalf of the patient, and to make informed surrogate decisions. Future research should focus on educational interventions that help surrogates prepare for their complex and unique role before an acute medical crisis to ease surrogate burden and decrease disparities in surrogate decision making.

Author's Contributions

All persons who contributed to this study are listed as authors.

Supplementary Material

Funding Information

Dr. Sudore is funded, in part, by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (Grant No. K24AG054415). Partial funding for this study was provided by The Greenwall Foundation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. : Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fried TR, Zenoni M, Iannone L, O'Leary JR: Assessment of surrogates' knowledge of patients' treatment goals and confidence in their ability to make surrogate treatment decisions. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:267–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fried TR, Zenoni M, Iannone L, et al. : Engagement in advance care planning and surrogates' knowledge of patients' treatment goals. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1712–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–832 e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD: Micromanaging death: Process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist 2005;45:107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fins JJ, Maltby BS, Friedmann E, et al. : Contracts, covenants and advance care planning: An empirical study of the moral obligations of patient and proxy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore CD, Sparr J, Sherman S, Avery L: Surrogate decision-making: judgment standard preferences of older adults. Soc Work Health Care 2003;37:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brudney D: Choosing for another: beyond autonomy and best interests. Hastings Cent Rep 2009;39:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger JT, DeRenzo EG, Schwartz J: Surrogate decision making: Reconciling ethical theory and clinical practice. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sulmasy DP, Snyder L: Substituted interests and best judgments: An integrated model of surrogate decision making. JAMA 2010;304:1946–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun UK, Naik AD, McCullough LB: Reconceptualizing the experience of surrogate decision making: Reports vs genuine decisions. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, et al. : Surviving surrogate decision-making: What helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1274–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W: Assessing psychological distress near the end of life. Am Behav Sci 2002;46:357–372. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thiede E, Levi BH, Lipnick D, et al. : Effect of advance care planning on surrogate decision makers' preparedness for decision making: Results of a Mixed-Methods Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med 2021;24:982–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, et al. : Beyond substituted judgment: How surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1688–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wittich AR, Williams BR, Bailey FA, et al. : “He got his last wishes”: Ways of knowing a loved one's end-of-life preferences and whether those preferences were honored. J Clin Ethics 2013;24:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fritsch J, Petronio S, Helft PR, Torke AM: Making decisions for hospitalized older adults: Ethical factors considered by family surrogates. J Clin Ethics 2013;24:125–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun UK, Beyth RJ, Ford ME, McCullough LB: Voices of African American, Caucasian, and Hispanic surrogates on the burdens of end-of-life decision making. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL: Advance care planning beyond advance directives: Perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Su CT, McMahan RD, Williams BA, et al. : Family matters: Effects of birth order, culture, and family dynamics on surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Petrillo LA, McMahan RD, Tang V, et al. : Older adult and surrogate perspectives on serious, difficult, and important medical decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1515–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cook SE, Marsiske M, McCoy KJ: The use of the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) in the detection of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2009;22:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD: Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: Results of a systematic integrated review. J Palliat Med 2016;19:202–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson KS: Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, et al. : Low completion and disparities in advance care planning activities among older medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1872–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bernard HR: Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glaser B, Strauss A: Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Sociology Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McMahan RD, Barnes DE, Ritchie CS, et al. : Anxious, depressed, and planning for the future: Advance care planning in diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:2638–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Comer AR, Hickman SE, Slaven JE, et al. : Assessment of discordance between surrogate care goals and medical treatment provided to older adults with serious illness. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e205179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC: Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: A systematic review. Chest 2011;139:543–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Torke AM, Petronio S, Purnell CE, et al. : Communicating with clinicians: The experiences of surrogate decision-makers for hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1401–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Torke AM, Callahan CM, Sachs GA, et al. : Communication quality predicts psychological well-being and satisfaction in family surrogates of hospitalized older adults: An observational study. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Devnani R, Slaven JE Jr., Bosslet GT, et al. : How surrogates decide: A secondary data analysis of decision-making principles used by the surrogates of hospitalized older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1285–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snyder L, Leffler C, Ethics, Human Rights Committee American College of Physicians: Ethics manual: Fifth edition. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:560–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, et al. : Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient's perspective. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Conference of Commissioners of Uniform State Laws. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 2005, pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scheerens C, Gilissen J, Volow AM, et al. : Developing eHealth tools for diverse older adults: Lessons learned from the PREPARE for Your Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:2939–2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.