Abstract

This study investigated the efficacy and safety of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with PD-1 immunotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer (BTC) and evaluated the optimal timing of HAIC. A total of 36 unresectable BTC patients treated with HAIC and PD-1 inhibitors between September 2019 and July 2021 were included in this study. Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), tumor response, and adverse events (AEs) were investigated. Overall, 52.8% patients with advanced BTC were in stage IV, 23 patients who progressed after receiving PD-1 inhibitor had undergone HAIC, and 23 patients have received 2 or more lines of therapy. The median OS was 8.8 months (range: 4.0-24.0 months), and the median PFS was 3.7 months. The objective response rate and disease control rate were 11.5% and 76.9%, respectively. In the subgroup analysis, patients who treated with HAIC early without progression after immunotherapy were associated with a trend toward better OS (median 13.0 vs. 7.6 months; P = 0.004) and PFS (median 7.9 vs. 3.6 months; P = 0.09) compared to with HAIC with progression after PD-1 treatment. No treatment-related deaths occurred. A total of 44.4% of the patients experienced grade 3 or 4 AEs. We conclude that the combination of HAIC and PD-1 inhibitors is safe and effective. Early HAIC combined with immunotherapy can effectively prolong the overall survival of patients with advanced BTC.

Keywords: Biliary tract cancer, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, PD-1 inhibitor, combination therapy, interventional time of HAIC

Introduction

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) represent a group of malignancies comprised of intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and gallbladder cancer (GBC). In China, the incidence of CCA is relatively high (> 6/100,000), and the incidence of GBC is at the middle and lower levels compared with those in the world (2.0-2.9/100,000) and has been increasing in the past few decades [1]. Because of its insidious onset, the majority of patients are often diagnosed in advanced stages, which results in a dismal prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate typically below 10% [2]. Although the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin has been established as a first-line therapy for advanced BTC, its response rate is not high [3]. In the recent ABC-06 study, the combination of folinic acid, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX) as second-line treatment after progression with gemcitabine-cisplatin (GemCis) demonstrated an overall survival (OS) benefit vs. active symptom control [4]. Novel effective therapeutic options are needed to improve the outcomes of patients with advanced BTCs.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors represented by programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibodies block negative regulatory signals and restore the killing activity of T cells to tumor cells, therefore enhancing the antitumor immune response. With the success of PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in various tumors [5,6], the objective response rate (ORR) of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy for BTC was reported to be 3.0%~22% [7-9], while hypermutated BTCs harboring MSI or TMB-H showed a 12-month OS of 33% [10].

Locoregional treatments, such as transarterial chemoembolization, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), radiofrequency ablation and radiotherapy, are still important approaches for advanced BTC [11]. HAIC delivers high doses of chemotherapeutic agents to the hepatic artery, which could diminish the systemic toxic effects of chemotherapy. Cercek A et al. [12] conducted a phase 2 clinical trial including 38 unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) patients treated with HAI floxuridine plus systemic gemcitabine and oxaliplatin. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.8 months, and the median OS was 25.0 months, with an ORR of 58%. HAIC was also proven to be effective for BTC patients in a number of phase I and II trials [13-16]. On the basis of preclinical data, we conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of HAIC with PD-1 inhibitors for patients with advanced refractory BTC.

Methods

Study design and patients

From September 2019 to July 2021, 66 patients with advanced BTC were screened, and 36 patients were enrolled in an open, multicenter-center study that was initiated by Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH). The protocol was approved by the local ethical committee, and all patients provided informed consent (JS-1391). Pertinent eligibility criteria included histologically confirmed unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancers, treatment with PD-1 inhibitor and HAIC, at least 1 line of systemic therapy but no more than 3 prior lines of systemic therapy, ECOG performance status 0-2, Child-Pugh score A-B, and adequate bone marrow and liver function.

Patients were excluded if they had severe alteration of liver function (prothrombin time < 40%), if the tumor burden in the liver was over 70% of the total liver volume, or if patients had undergone other concomitant treatments. Previous chemotherapy was not an exclusion criterion for this study. Figure 1 summarizes the patient enrollment process of the current study.

Figure 1.

Patient Screening and Enrollment Flowchart.

Treatment and dosing information

Information regarding the dates of initiation and completion of treatment, radiological evaluation, laboratory data, surgery data, and adverse events (AEs) during treatment were systematically collected. All patients received different lines of systemic therapy, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. The PD-1 inhibitor dose included a fixed dosage of 200 mg every 3 weeks or a fixed dosage of 3 mg/kg body weight every 3 weeks. The HAIC regimen was composed of oxaliplatin (40 mg/m2 for 2 h) and 5-fluorouracil (800 mg/m2 for 22 h) on days 1-3 every 3 or 4 weeks. Leucovorin calcium was dripped intravenously at a dose of 200 mg/m2 for 2 h during 5-fluorouracil infusion [13,14].

Assessments

The clinical objective response was measured by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) [17] criteria, evaluated by professional radiologists at the center (PUMCH) who were blinded to therapeutic outcomes and clinicopathological features. The ORR was used to assess the efficacy of treatments. Complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) were recognized as overall responses, and CR, PR, and stable disease (SD) were considered tumor control. Safety assessment and grading were recorded in the electronic medical records or collected by the investigators using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) as a reference [18].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described as the median and range and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. OS was defined as the time from the initiation of HAIC to the date of death or censorship at the last follow-up, and PFS was defined as the date from the initiation of HAIC to disease progression, the last follow-up, or death, whichever occurred first. OS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to identify variables that were statistically significant. The factors with P < 0.10 in univariate analysis were analyzed in multivariate analysis. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered to prove significance for all tests. Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 24.0).

Results

Patient characteristics

Thirty-six patients with advanced BTC were included in this study. The characteristics of these patients are provided in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 59 years (range, 27-79), and 58.3% of patients were male. Twenty-seven patients (75%) had ICC, 5 (13.9%) had extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and 4 (11.1%) had gallbladder cancer. Most patients had TNM stage IV (55.6%) at the beginning of HAIC, and the liver (63.9%) and intraabdominal lymph nodes (55.6%) were the most common metastatic sites. Twenty-three patients (63.9%) who progressed after receiving PD-1 inhibitor had undergone HAIC. There were 23 patients who had received 2 or more lines of therapy prior to study enrollment. In addition, half of the patients had undergone previous surgery and 23 patients’ tumor burden score (TBS) were high according to imaging data [19]. Some patients lacked the data of CA199 and CEA levels before treatment, one patient could not be evaluated for TNM stage, and two patients could not accurately obtain TBS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 59 (27-79) |

| Sex, n [%] | |

| Male | 21 [58.3] |

| Female | 15 [41.7] |

| ECOG performance, n [%] | |

| 0 | 23 [63.9] |

| 1 | 10 [27.8] |

| 2 | 3 [8.3] |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| A | 32 [88.9] |

| B | 4 [11.1] |

| Tumor subtype, n [%] | |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 27 [75] |

| Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 5 [13.9] |

| Gallbladder cancer | 4 [11.1] |

| Differentiated histology, n [%] | |

| Poor | 12 [33.3] |

| Moderate | 15 [41.7] |

| Unsure | 9 [25] |

| CEA level, n [%] | |

| < 10 U/mL | 15 [41.7] |

| ≥ 10 U/mL | 11 [30.6] |

| CA19-9 level, n [%] | |

| < 200 U/mL | 13 [36.1] |

| ≥ 200 U/mL | 17 [47.2] |

| Site of metastasis, n (%) | |

| Intrahepatic | 23 [63.9] |

| Lymph nodes | 20 [55.6] |

| Lung | 11 [30.6] |

| Bone | 8 [22.2] |

| TNM stage, n [%] | |

| II | 5 [13.9] |

| III | 11 [30.6] |

| IV | 19 [52.8] |

| Prior surgery, n [%] | |

| Yes | 18 [50] |

| No | 18 [50] |

| Progression after immunotherapy, n [%] | |

| Yes | 23 [63.9] |

| No | 13 [36.1] |

| Previous line of therapy, n [%] | |

| 1 | 13 [36.1] |

| ≥2 | 23 [63.9] |

| Tumor burden score, n [%] | |

| TBS-H | 23 [63.9] |

| TBS-L | 11 [30.6] |

Response and survival

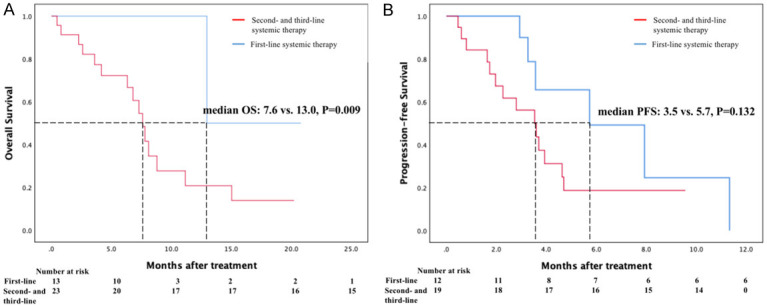

According to RECIST v1.1, PR and SD were achieved in 3 (11.5%) and 17 (65.4%) patients, respectively (Table 2). No CR was observed. The median OS was 8.8 months (range 0.5-20.8 months; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.2-12.4 months, Figure 2A), and the median PFS was 3.7 months (range 0.5-11.3 months; 95% CI: 3.2-4.2 months, Figure 2B) in this study. Patients treated with first-line systemic therapy (n = 13) had numerically better OS (median 13.0 vs. 7.6 months; P = 0.009, Figure 3A) than those treated with second- and third-line systemic therapy. The median PFS of patients with 1 line of systemic therapy was 5.7 months, and that of patients with 2 and 3 lines of systemic therapy was 3.5 months (P = 0.132, Figure 3B). On the other hand, HAIC without progression after PD-1 treatment (n = 13) was associated with a trend toward better OS (median 13.0 vs. 7.6 months, P = 0.004, Figure 4A) and PFS (median 7.9 vs. 3.6 months; P = 0.09, Figure 4B) compared to with HAIC with progression after PD-1 treatment.

Table 2.

Therapeutic efficacy of response and survival outcomes for 26 BTC patients

| Therapeutic response assessment | Evaluable patients (n = 26) |

|---|---|

| Complete response (CR, n, %) | 0 |

| Partial response (PR, n, %) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Stable disease (SD, n, %) | 17 (47.2%) |

| Progressive disease (PD, n, %) | 6 (23.1%) |

Figure 2.

A. Kaplan-Meier estimation of OS of the entire cohort; B. Kaplan-Meier estimation of PFS of the entire cohort.

Figure 3.

A. Kaplan-Meier estimation of OS of advanced BTC patients who treated with first-line systemic therapy (blue line) or second- and third-line systemic therapy (red line); B. Kaplan-Meier estimation of PFS of advanced BTC patients who treated with first-line systemic therapy (blue line) or second- and third-line systemic therapy (red line).

Figure 4.

A. Kaplan-Meier estimation of OS of advanced BTC patients who treated HAIC without progression after PD-1 treatment (blue line) or with progression after PD-1 treatment (red line); B. Kaplan-Meier estimation of PFS of advanced BTC patients who treated HAIC without progression after PD-1 treatment (blue line) or with progression after PD-1 treatment (red line).

Risk factors for survival

Tables 3 and 4 show all variables that were included in the univariate analyses and were potentially associated with a longer OS and PFS. The results indicate that ECOG, Child-Pugh score, TBS, and line of systemic therapy were relevant factors for better OS and PFS. Lines of systemic therapy showed significant differences in the univariate analyses, revealing that it was an independent prognostic factor related to decreased survival.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for OS

| Variates | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≥ 65) | 0.906 | 0.938 (0.324, 2.715) | ||

| Sex | 0.243 | 0.543 (0.195, 1.513) | ||

| ECOG PS (0/1+2) | 0.034 | 2.920 (1.082, 7.882) | 0.335 | 2.035 (0.480, 8.621) |

| Child-Pugh score (A/B) | 0.053 | 3.743 (0.986, 14.216) | 0.867 | 1.134 (0.261, 4.931) |

| CEA level | 0.583 | 1.363 (0.450, 4.127) | ||

| CA19-9 level | 0.904 | 1.067 (0.369, 3.087) | ||

| Metastasis (Y/N) | 0.727 | 1.195 (0.440, 3.241) | ||

| TNM stage (II+III/IV) | 0.479 | 1.438 (0.526, 3.927) | ||

| Prior surgery | 0.426 | 0.665 (0.244, 1.815) | ||

| Progression after immunotherapy | 0.122 | 3.259 (0.730, 14.541) | ||

| Line of systemic therapy | 0.036 | 8.780 (1.158, 66.572) | 0.013 | 27.868 (2.030, 382.574) |

| TBS (H/L) | 0.028 | 3.880 (1.161, 12.965) | 0.060 | 10.022 (0.910, 110.407) |

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for PFS

| Variates | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≥ 65) | 0.911 | 0.943 (0.337, 2.642) | ||

| Sex | 0.202 | 0.528 (0.198, 1.409) | ||

| ECOG PS (0/1+2) | 0.067 | 2.377 (0.940, 6.012) | 0.299 | 1.810 (0.590, 5.551) |

| Child-Pugh score (A/B) | 0.006 | 7.367 (1.794, 30.248) | 0.065 | 6.880 (0.886, 53.415) |

| CEA level | 0.978 | 0.985 (0.340, 2.856) | ||

| CA19-9 level | 0.326 | 0.596 (0.213, 1.672) | ||

| Metastasis (Y/N) | 0.482 | 1.391 (0.554, 3.489) | ||

| TNM stage (ll+lll/lV) | 0.347 | 1.595 (0.603, 4.220) | ||

| Prior surgery | 0.657 | 0.814 (0.329, 2.015) | ||

| Progression after immunotherapy | 0.121 | 2.268 (0.805, 6.390) | ||

| Line of systemic therapy | 0.084 | 2.490 (0.886, 6.995) | 0.169 | 2.481 (0.679, 9.069) |

| TBS (H/L) | 0.082 | 2.764 (0.880, 8.685) | 0.248 | 2.064 (0.603, 7.058) |

Tolerability and safety

None of the patients experienced complications attributable to the port-catheter system, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during or after HAIC treatment. Sixteen patients (44.4%) experienced grade 3 or 4 AEs (Table 5). Additionally, fatigue (52.8%), increased AST or ALT (52.8%), total bilirubin increased (38.9%) and abdominal pain (38.9%) were the most common AEs (any grade). The most common grade 3 AEs were fatigue (13.9%) and nausea (13.9%), followed by thrombocytopenia (11.1%). Grade 4 thrombocytopenia and hepatic encephalopathy were both observed in 1 patient (1 of 36, 2.8%).

Table 5.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Events, n (%) | Biliary tract carcinoma (n = 36) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Any grade, n (%) | Grade 1-2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) | |

| All term | 36 (100) | 36 (100) | 16 (44.4) | 2 (5.6) |

| Fatigue | 19 (52.8) | 14 (38.9) | 5 (13.9) | 0 |

| Nausea | 6 (16.7) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (13.9) | 0 |

| Dysphonia | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 4 (11.1) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 |

| Gingivitis | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 6 (16.7) | 4 (11.1) | 2 (5.6) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 8 (22.2) | 7 (19.4) | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Hydrothorax | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 9 (25) | 6 (16.7) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| Headache | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 14 (38.9) | 11 (30.6) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Ascites | 9 (25) | 9 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| AST or ALT increased | 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | 2 (5.6) | 0 |

| Anemia | 9 (25) | 9 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Total bilirubin increased | 14 (38.9) | 14 (38.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (16.7) | 6 (16.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoproteinemia | 10 (27.8) | 10 (27.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 17 (47.2) | 12 (33.3) | 4 (11.1) | 1 (2.8) |

| Leukopenia | 13 (36.1) | 10 (27.8) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 5 (13.9) | 4 (11.1) | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| Emaciation | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 6 (16.7) | 6 (16.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Biliary tract infection | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Lumbodorsal pain | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

BTC is a fatal and highly malignant gastrointestinal tumor with low response rates and poor prognosis. Previous studies have indicated a poor mean OS rate for patients with CCA (less than 24 months) and gallbladder cancer (6 months) [20]. In recent years, standard first-line chemotherapy has increased the survival time and improved the quality of life of patients with unresectable BTC [3,20-22]. In addition, 25%-50% of patients with disease progression still have therapeutic options, such as second-line chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, locoregional therapy and combination treatment. A systematic review by Lamarca A et al. [23], which included 25 studies involving 761 patients with advanced BTC who progressed after first-line chemotherapy, showed a mean OS of 7 months and PFS of 3 months when treated with second-line chemotherapy. Therefore, it is necessary to explore more possible combination therapies to improve outcomes of far-advanced BTC patients.

In the present study, we describe the antitumor activity and toxicity of HAIC plus PD-1 inhibitor as a non-first-line treatment in 36 patients with advanced BTC. Most patients enrolled in our study cohort were at a late clinical stage and were estimated to have a limited survival time. Patients who received PD-1 inhibitor plus HAIC achieved satisfactory median PFS and OS (3.7 and 8.8 months, respectively). Notably, an 11.5% ORR and 76.9% disease control rate according to the RECIST criteria were observed. After stratification by lines of systemic therapy, the median OS in the first-line group was significantly longer than that in the second- and third-line group (P = 0.09). In addition, after stratification by the presence or absence of progression after immunotherapy, patients without progression showed a significantly better median OS (13.0 vs. 7.6 months, P = 0.004) and PFS (7.9 vs. 3.6 months, P = 0.09) than those with progression after PD-1 therapy. In terms of therapeutic safety, although all patients experienced AEs, there were no grade 5 AEs reported, and only 2 patient experienced a grade 4 SAE. Approximately 44.4% of patients experienced grade 3 AEs, but all these SAEs were reversible. Our preliminary study reveals that earlier treatment with HAIC might be effective in prolonging survival time for advanced unresectable BTC patients.

Although the current study reported the results of HAIC combined with PD-1 inhibitor, thus providing clinical evidence for future prospective studies, it has some limitations. First, it was a multicenter, single-arm, retrospective study with a limited sample size. Therefore, the level of evidence is relatively low. Second, the categories of PD-1 inhibitors and prior systemic therapy varied. Thus, different baseline characteristics of patients caused a certain bias. This can also explain why multivariate analysis showed no independent prognostic factors related to prolonged survival. In the future, we will conduct a prospective randomized controlled trial to confirm the benefit of this combination.

In conclusion, treatment with HAIC combined with PD-1 immunotherapy for advanced BTC patients is safe and effective. The early addition of HAIC to systemic therapy may confer better efficacy, leading to longer survival. Our team hope to actively explore the possibility of combined local treatment and systemic treatment based on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to achieve the goal of bringing long-term tumor-free survival to patients with unresectable BTC.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients participating in this study and all staff at the hospital for their contributions to this study. This work was supported by grants from the CSCO-MSD Cancer Research Fund (Y-MSDZD2021-0213), Beijing Hospitals Authority Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (Grant No. ZYLX202117), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 7212198), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82172039).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, Lamarca A, Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Andersen JB, Braconi C, Calvisi DF, Perugorria MJ, Fabris L, Boulter L, Macias RIR, Gaudio E, Alvaro D, Gradilone SA, Strazzabosco M, Marzioni M, Coulouarn C, Fouassier L, Raggi C, Invernizzi P, Mertens JC, Moncsek A, Rizvi S, Heimbach J, Koerkamp BG, Bruix J, Forner A, Bridgewater J, Valle JW, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, Barriuso J, Zhu AX. New horizons for precision medicine in biliary tract cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:943–962. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J ABC-02 Trial Investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamarca A, Palmer DH, Wasan HS, Ross PJ, Ma YT, Arora A, Falk S, Gillmore R, Wadsley J, Patel K, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Iveson T, Waters JS, Hobbs C, Barber S, Ryder WD, Ramage J, Davies LM, Bridgewater JA, Valle JW. ABC-06 | A randomised phase III, multi-centre, open-label study of active symptom control (ASC) alone or ASC with oxaliplatin/5-FU chemotherapy (ASC+mFOLFOX) for patients (pts) with locally advanced/metastatic biliary tract cancers (ABC) previously-treated with cisplatin/gemcitabine (CisGem) chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:4003–4003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, Walsh LA, Postow MA, Wong P, Ho TS, Hollmann TJ, Bruggeman C, Kannan K, Li Y, Elipenahli C, Liu C, Harbison CT, Wang L, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Chan TA. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, Miller ML, Rekhtman N, Moreira AL, Ibrahim F, Bruggeman C, Gasmi B, Zappasodi R, Maeda Y, Sander C, Garon EB, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Schumacher TN, Chan TA. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueno M, Ikeda M, Morizane C, Kobayashi S, Ohno I, Kondo S, Okano N, Kimura K, Asada S, Namba Y, Okusaka T, Furuse J. Nivolumab alone or in combination with cisplatin plus gemcitabine in Japanese patients with unresectable or recurrent biliary tract cancer: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:611–621. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piha-Paul SA, Oh DY, Ueno M, Malka D, Chung HC, Nagrial A, Kelley RK, Ros W, Italiano A, Nakagawa K, Rugo HS, de Braud F, Varga AI, Hansen A, Wang H, Krishnan S, Norwood KG, Doi T. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for the treatment of advanced biliary cancer: results from the KEYNOTE-158 and KEYNOTE-028 studies. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:2190–2198. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim RD, Chung V, Alese OB, El-Rayes BF, Li D, Al-Toubah TE, Schell MJ, Zhou JM, Mahipal A, Kim BH, Kim DW. A phase 2 multi-institutional study of nivolumab for patients with advanced refractory biliary tract cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, De Jesus-Acosta A, Delord JP, Geva R, Gottfried M, Penel N, Hansen AR, Piha-Paul SA, Doi T, Gao B, Chung HC, Lopez-Martin J, Bang YJ, Frommer RS, Shah M, Ghori R, Joe AK, Pruitt SK, Diaz LA Jr. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oneda E, Abu Hilal M, Zaniboni A. Biliary tract cancer: current medical treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1237. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cercek A, Boerner T, Tan BR, Chou JF, Gönen M, Boucher TM, Hauser HF, Do RKG, Lowery MA, Harding JJ, Varghese AM, Reidy-Lagunes D, Saltz L, Schultz N, Kingham TP, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Drebin JA, Allen PJ, Balachandran VP, Lim KH, Sanchez-Vega F, Vachharajani N, Majella Doyle MB, Fields RC, Hawkins WG, Strasberg SM, Chapman WC, Diaz LA Jr, Kemeny NE, Jarnagin WR. Assessment of hepatic arterial infusion of floxuridine in combination with systemic gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;6:51–59. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Hu J, Cao G, Zhu X, Cui Y, Ji X, Li X, Yang R, Chen H, Xu H, Liu P, Li J, Li J, Hao C, Xing B, Shen L. Phase II study of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil for advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Radiology. 2017;283:580–589. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng K, Wang X, Cao G, Xu L, Zhu X, Fu L, Fu S, Cheng H, Yang R. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil for advanced gallbladder cancer. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2021;44:271–280. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura M. A successful treatment by hepatic arterial infusion therapy for advanced, unresectable biliary tract cancer. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:192–7. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i5.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinn M, Nicolaou A, Gebauer B, Podrabsky P, Seehofer D, Ricke J, Dörken B, Riess H, Hildebrandt B. Hepatic arterial infusion with oxaliplatin and 5-FU/folinic acid for advanced biliary tract cancer: a phase II study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2399–405. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE): version 4.0. Published May 28, 2009. Accessed March 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitale A, Lai Q, Farinati F, Bucci L, Giannini EG, Napoli L, Ciccarese F, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, Caturelli E, Zoli M, Borzio F, Sacco R, Cabibbo G, Virdone R, Marra F, Felder M, Morisco F, Benvegnù L, Gasbarrini A, Svegliati-Baroni G, Foschi FG, Missale G, Masotto A, Nardone G, Colecchia A, Bernardi M, Trevisani F, Pawlik TM Italian Liver Cancer (ITA.LI.CA) group. Utility of tumor burden score to stratify prognosis of patients with hepatocellular cancer: results of 4759 cases from ITA.LI.CA study group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:859–871. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3688-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shroff RT, Javle MM, Xiao L, Kaseb AO, Varadhachary GR, Wolff RA, Raghav KPS, Iwasaki M, Masci P, Ramanathan RK, Ahn DH, Bekaii-Saab TS, Borad MJ. Gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:824–830. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simile MM, Bagella P, Vidili G, Spanu A, Manetti R, Seddaiu MA, Babudieri S, Madeddu G, Serra PA, Altana M, Paliogiannis P. Targeted therapies in cholangiocarcinoma: emerging evidence from clinical trials. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55:42. doi: 10.3390/medicina55020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Péré-Vergé D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamarca A, Hubner RA, David Ryder W, Valle JW. Second-line chemotherapy in advanced biliary cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2328–38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]