Abstract

Background

The emotional stress of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias is high and results in adverse effects on caregivers and the persons living with disease. In preliminary work, caregiver reports of regularly feeling “completely overwhelmed” were associated with lack of measurable clinical benefit from a comprehensive dementia care program.

Objective

To examine the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all caregivers who felt overwhelmed at entry into a comprehensive dementia care program, the trajectory of this symptom over 1 year, and its predictive value for 1-year caregiver outcomes.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study

Setting

Academic health center

Participants

Caregivers of patients enrolled in a comprehensive dementia care program

Exposures

Caregiver report of feeling “completely overwhelmed” at baseline

Main Measures

Caregiver report of feeling “completely overwhelmed” at baseline and 1 year, and validated scales of caregiver strain, distress, depressive symptoms, burden, mortality, and long-term nursing home placement

Key Results

Compared to caregivers who were not overwhelmed, overwhelmed caregivers had more distress from behavioral symptoms of the person living with dementia, worse depression scores, and higher composite dementia burden scores at baseline. They also had worse depressive symptoms, strain, and composite burden scores at 1 year, after adjustment for baseline scores. Having an overwhelmed caregiver did not predict long-term nursing home placement or mortality among persons with dementia.

Conclusions

A single question about whether a caregiver is overwhelmed might indicate caregivers who have considerable current and future symptom burden and who may benefit from increased support and resources.

KEY WORDS: caregiver stress, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, Prior presentations: None

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 11.2 million Americans provide unpaid care for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) [1]. As a result of the cognitive and behavioral consequences of dementia, the burden on caregivers can be immense including strain, depression, and other adverse consequences on their own health [2, 3]. Over half of family caregivers rate the emotional stress of caring for someone with ADRD as high or very high [1] and 30–40% develop depression [4], at considerably higher rates than those who are caring for persons with conditions such as schizophrenia [5]. The toll is especially high for those who care for persons living with dementia (PLWD) who have 4 or more behavioral symptoms [6]. Moreover, such burden can result in further adverse outcomes for the PLWD including nursing home placement [7, 8].

In the context of evaluating a comprehensive dementia care program [9] that has shown clinical [10], utilization [11], and cost benefits [12], we interviewed and surveyed a subset of caregivers of persons in the program who did not demonstrate any benefit on clinical outcomes, including validated scales assessing dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver strain and depression [10]. When examining characteristics of caregivers interviewed, we found that they commonly reported feeling “completely overwhelmed,” [13] an item from the Modified Caregiver Strain Index [14], which was administered to all program participants at entry into the program.

To further assess the value of this single symptom to identify caregivers at high stress, we studied the entire cohort of the first 1002 participants in the program to examine the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all caregivers who felt overwhelmed at entry into the program, the trajectory of this symptom over 1 year, and its predictive value for 1-year caregiver outcomes.

METHODS

The study was a secondary analysis of baseline and 1-year outcome data, and up to 4-year survival and long-term nursing home placement data from the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care (UCLA ADC) Program, a comprehensive dementia management program that utilizes nurse practitioner Dementia Care Specialists to co-manage PLWD and support their caregivers [8]. In a previous study, caregivers who felt overwhelmed at baseline perceived the program as being less beneficial [13]. To determine whether caregivers reporting regularly feeling overwhelmed were at high stress and characterize this population, we first performed cross-sectional analyses examining associations between this symptom and caregiver sociodemographic characteristics, aspects of the PLWD whom they were caring for, and other stress-related symptoms of caregiving. Then, we examined the effect of regularly feeling overwhelmed at baseline on 1-year caregiver and patient outcomes. We next examined the change in feeling regularly overwhelmed over 1 year. Finally, we examined the relationship between being overwhelmed at baseline and PLWD survival and long-term nursing home placement. Analysis of the UCLA ADC Program was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sociodemographic Measures Were Self-reported

Overwhelmed

The overwhelmed question is taken from the 13-item Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI) [15] (range 0–26), with higher scores indicating greater strain; the minimal clinically important difference is 1.3–2.3. Caregivers are shown the statement, “I feel completely overwhelmed,” and two examples are provided, “I worry about the person I care for; I have concern about how I will manage.” Respondents are given three response choices: “yes, on a regular basis,” “yes, sometimes,” and “no.” For this analysis, we collapsed “yes, sometimes” and “no,” which allowed us to compare those who regularly felt overwhelmed (hence termed “overwhelmed”) with all others who had less severe symptoms.

PLWD Measures

PLWD measures included sociodemographics; the Mini Mental State Exam, which measures cognition (range 0–30) with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment [16]; and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, a 19-item tool (range 0–38), where a score of ≥11 indicates probable depression [17].

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) [18] assesses the caregiver’s perception of the severity of 12 dementia-related psychiatric and behavioral symptoms and the level of distress experienced by the caregiver as a result. NPI-Q Severity score ranges 0–36 and NPI-Q Distress scores range 0–60; higher scores indicate more severe symptoms and distress, respectively. The minimal clinically important difference is 2.8–3.2 points for severity and 3.1–4.0 points for distress [19].

Functional status was measured using basic activities of daily living [20] and instrumental activities of daily living scales [21]. We also administered the Functional Activities Questionnaire, which measures tasks similar to instrumental activities of daily living (range 0–30) with higher scores indicating more functional dependence [22].

Caregiver Outcome Measures

Caregiver outcome measures included the MCSI, the NPI-Q Distress (both described above), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [23], a 9-item measure of depressive symptoms (range 0–27) with scores >10 indicating moderate symptoms and scores >20 indicating severe symptoms. The minimal clinically important difference for the PHQ-9 is 5 points [24]. The Dementia Burden Scale-Caregiver [25] is a composite of the NPI-Q Distress, MCSI, and PHQ-9 scales with items transformed linearly (range 0–100) with higher scores indicating higher caregiver burden; the minimal clinically important difference is 5 points.

Analysis

Continuous outcomes were summarized using median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical outcomes were summarized using counts and percentages. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to evaluate differences in continuous and categorical outcomes between overwhelmed and not overwhelmed caregivers at baseline. Multivariable linear regression models were used to assess the association between longitudinal changes at 1 year in caregiver outcome scores and feeling overwhelmed at baseline while adjusting for the baseline scores on these instruments. Because the “overwhelmed” item is part of the MCSI, we performed a sensitivity analysis removing that item from the scale. Results were summarized reporting mean change and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used the California Public Health Department mortality data to identify dates of death, supplemented by program files. Nursing home placement was obtained from claims data for a subsample provided to UCLA for its Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) [11, 26].

Unadjusted Cox proportional hazard models were used to report hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI for time to death and time to long-term nursing home placement and the composite score of the two events including feeling overwhelmed at baseline (yes/no) as an independent covariate. All tests were two-sided and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed in R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10).

RESULTS

Of the 1002 caregivers, 300 (30%) reported regularly feeling completely overwhelmed. Sociodemographic characteristics of these caregivers and the persons they cared for are provided in Table 1. Compared to those who were not overwhelmed, overwhelmed caregivers were more likely to be female and children of the PLWD. Wives of PLWD most commonly felt overwhelmed at program entry (40%), followed by daughters (35%).

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics of Caregivers Who Were Regularly Overwhelmed at ADC Program Entry Compared to Those Who Were Not or Were Sometimes Overwhelmed

| Variable | Not overwhelmed, n = 702 (70%) | Overwhelmed, n = 300 (30%) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver characteristics | |||

| Gender (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 252 (36%) | 73 (24%) | |

| Female | 448 (64%) | 227 (76%) | |

| Relationship | 0.002 | ||

| Spouse | 247 (35%) | 114 (38%) | |

| Child | 334 (48%) | 161 (54%) | |

| Other | 120 (17%) | 24 (8%) | |

| Caregiver relation and gender (row percent) | <0.001 | ||

| Female child | 235 (64.9%) | 127 (35.1%) | |

| Female other | 94 (82.5%) | 20 (17.5%) | |

| Female spouse | 119 (59.8%) | 80 (40.2%) | |

| Male child | 98 (73.7%) | 35 (26.3%) | |

| Male other | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| Male spouse | 128 (79%) | 34 (21%) | |

| Race | 0.81 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 328 (77%) | 129 (80%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 48 (11%) | 17 (11%) | |

| Asian | 38 (9%) | 13 (8%) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Other (not Hispanic, multiracial including Pacific Islander) | 5 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Person living with dementia characteristics | |||

| Age, years (interquartile range) | 84 (77–89) | 83 (76–88) | 0.07 |

| Gender | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 220 (31%) | 123 (41%) | |

| Female | 482 (69%) | 177 (59%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.008 | ||

| White not Hispanic | 468 (72%) | 165 (60%) | |

| Black not Hispanic | 48 (7%) | 26 (10%) | |

| Hispanic | 68 (10%) | 50 (18%) | |

| Other (not Hispanic, multiracial including Asian and Pacific Islander) | 71 (11%) | 34 (12%) | |

| Primary language not English | <0.001 | ||

| No | 592 (86%) | 211 (73%) | |

| Yes | 95 (14%) | 79 (27%) | |

| Number (%) with college or higher education | 0.03 | ||

| No | 216 (32%) | 114 (39%) | |

| Yes | 467 (68%) | 178 (61%) | |

| Medicare and Medicaid dually insured | 0.02 | ||

| No | 635 (91%) | 254 (85%) | |

| Yes | 67 (9%) | 45 (15%) | |

| Alzheimer’s, mixed vascular and Alzheimer’s, or unspecified type of dementia | 0.43 | ||

| No | 79 (11%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Yes | 617 (89%) | 269 (91%) | |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | 22 (15–28) | 25 (20–29) | <0.001 |

| ADLs performed independently range (0–5) | 4 (1–6) | 4 (1–5) | 0.21 |

| IADLs performed independently range (0–7) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.27 |

| Mini Mental State Exam, range (0–30) | 18 (13–23) | 17 (11–22) | 0.08 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) Severity | 8 (4–13) | 13 (8–19) | <0.001 |

| Cornell depression in dementia | 8 (5–12.8) | 12 (7–17) | <0.001 |

| Caregiver clinical symptoms | |||

| Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI) | 8 (4–12) | 17 (13–21) | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) Distress | 9 (3–15) | 17 (10–26) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 | 2 (0.2–5) | 7 (4–11) | <0.001 |

| Dementia Burden Scale-Caregiver | 21 (12–31) | 43 (34–54) | <0.001 |

*Except as indicated, percentages are column percent

p values calculated using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variable

The PLWD they cared for were more likely to be male and white and non-Hispanic; have a primary language other than English and less than college education; and be dually Medicare and Medicaid insured. The PLWD of overwhelmed caregivers had worse functional impairment, worse cognitive function, and more depressive and behavioral symptoms. In turn, overwhelmed caregivers had more distress from dementia-related behavioral symptoms, worse depression scores, and higher composite dementia burden scores (Table 1).

Outcomes at 1 year (Table 2) were available for 489 (49%) caregivers; reasons for the loss to follow-up have been reported [10]. About half were due to relocation, change in program eligibility, or failing to respond to program outreach efforts, and the other approximately half were caregivers who remained in the program but did not complete 1-year surveys. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of patients and their caregivers with outcomes data were similar to those missing outcomes but had slightly better baseline scores on function, PLWD depression, and both subscales of the NPI-Q [10]. Overwhelmed caregivers were no more likely to be lost to follow-up than non-overwhelmed caregivers (odds ratio: 1.18, 95%CI [0.89, 1.57], p = 0.26).

Table 2.

One-Year Outcomes by Caregiver Report of Feeling Regularly Overwhelmed at ADC Program Entry

| Outcome | Not overwhelmed, n = 338 (69%) | Overwhelmed, n = 151 (31%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver outcomes | |||

| Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI) | 8 (4–11) | 12 (8–17) | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) Distress | 5 (1–12) | 7 (1–16.5) | 0.01 |

| PHQ-9 | 1 (0–4) | 4 (1–8) | <0.001 |

| Dementia Burden Scale-Caregiver | 24 (14–34) | 37 (25–52) | <0.001 |

| Person living with dementia outcomes | |||

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | 26 (19–30) | 27 (22–30) | 0.04 |

| ADLs performed independently range (0–5) | 4 (1–6) | 4 (2–6) | 0.59 |

| IADLs performed independently range (0–7) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.47 |

| Mini Mental State Exam, range (0–30) | 17 (11–21) | 15 (11–19) | 0.10 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) Severity | 6 (2–11) | 8 (3–13) | 0.02 |

| Cornell depression in dementia | 6 (3–10) | 7 (3–13) | 0.04 |

Only those with baseline and 1-year follow-up

PLWD with overwhelmed caregivers at baseline had worse 1-year function, NPI-Q Severity, and depression scores. Most 1-year outcomes were worse for caregivers who were overwhelmed at baseline. After controlling for the baseline scores, being overwhelmed at the baseline was significantly associated with an increase in MCSI score at year 1 (mean difference = 1.91, 95% CI: [0.74, 3.09], p value=0.001). Removing the “overwhelmed” item from MCSI did not change the score appreciably (mean difference = 1.96, 95% CI: [0.73, 3.20], p value=0.002). The mean difference in 1-year depressive symptoms adjusted for baseline PHQ-9 was 1.00 (95% CI: [0.16, 1.83], p value=0.02) and overall caregiver burden (mean difference=4.02, 95% CI: [0.56, 7.47], p value=0.02) were worse at year 1 but distress due to the PLWD’s behavioral symptoms did not differ at 1 year (mean difference 0.61, 95% CI: [−0.93, 2.1], p value=0.44).

After 1 year in the ADC program, about two-thirds (102/151) of caregivers who were overwhelmed at baseline and were still in the program were no longer overwhelmed at 1 year. Conversely, among the entire sample with baseline and 1-year follow-up assessments, only 6% (20/338) were newly overwhelmed at 1 year and 10% (49/489) were overwhelmed at both time points (p<0.001 by Fisher’s exact test).

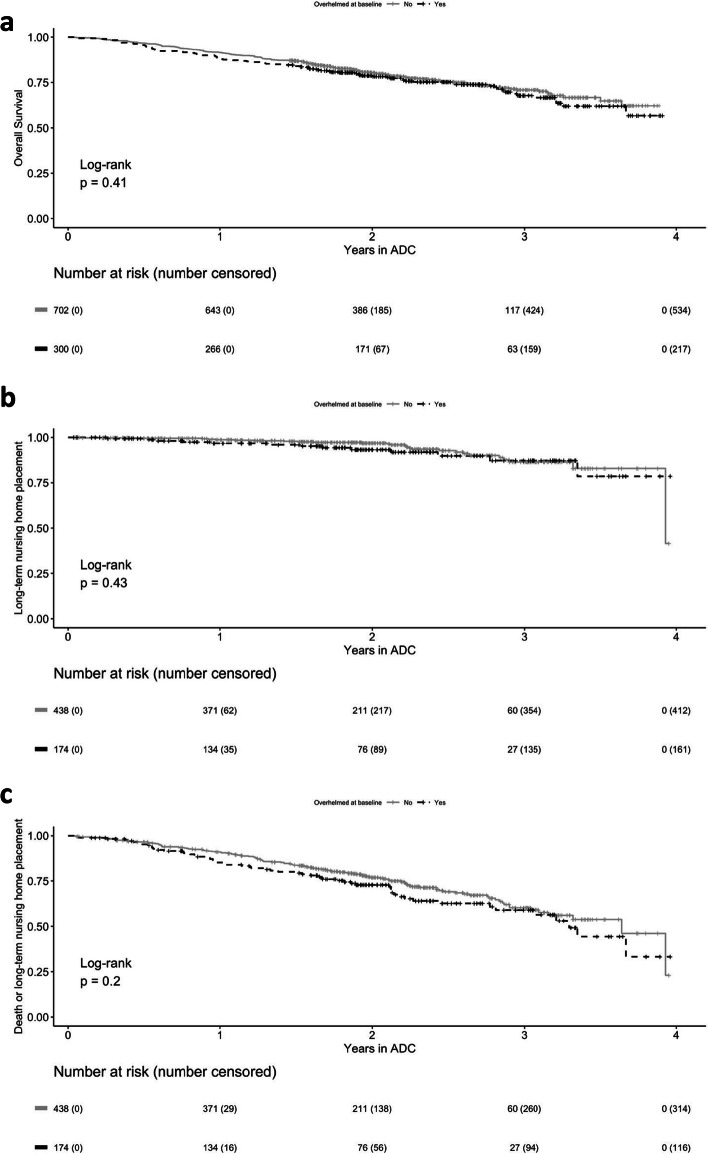

At 1 year, 251 PLWD had died, 168/702 (23%) among those whose caregivers were not overwhelmed and 83/200 (42%) of those whose caregivers were overwhelmed. Being overwhelmed at baseline did not predict PLWD time to death (hazard ratio [HR] 1.12, 95% [CI] 0.86, 1.45), long-term nursing home placement (HR 1.31, 95% CI 0.67, 2.55), or the combination of mortality and long-term nursing home placement (HR 1.23, 95% CI 0.90, 1.67) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of baseline caregiver overwhelmed status on PLWD time to death (a), long-term nursing home placement (b), and combination of death and long-term nursing home placement (c). Figure a is based on the entire sample, including those who had left the program, whereas Figs. b and c were limited to participants who also had claims data, including those who had left the program. ADC, UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that caregivers who reported regularly feeling completely overwhelmed had substantially greater symptom burden compared to those who reported this symptom sometimes or not at all. For each of the caregiver symptom scales, the difference met or exceeded (and, for some, far exceeded) the minimal clinically important differences. Thus, this one symptom was a marker of severe consequences of caregiving.

As expected, feeling overwhelmed was associated with PLWD behavioral complications of dementia, including depressive symptoms, and functional impairment, each of which adds to the stress of caregivers. Moreover, feeling overwhelmed at baseline was associated with 1-year caregiver depressive symptoms, strain, and burden, even when adjusting for baseline symptoms on these measures. However, baseline reports of feeling overwhelmed did not predict PLWD survival or long-term nursing home placement though the event rate and sample size limited the power to detect such effects.

It is important to note that everyone in this study received comprehensive dementia care management that has been shown to be beneficial in reducing caregivers’ symptoms [10]. This may partially explain why approximately two-thirds of those who reported feeling overwhelmed at baseline improved on this symptom. Whether such improvement was a response to the program or a temporal effect as the PLWD symptoms changed or adaptations were made is unknown. Yet the improvement on multiple clinical outcomes [10] among participants in the program suggests that this symptom may be modifiable. Similarly, our finding that feeling overwhelmed was not associated with mortality or long-term nursing home placement, which has previously been associated with high caregiver stress [7, 8], may be attributable, in part, to the program’s benefit on neuropsychological symptoms of persons with dementia and caregiver strain, distress, and depressive symptoms [10].

Although comprehensive dementia care programs are not widely available, individual clinicians could use the question to identify caregivers to refer to the Alzheimer’s Association and other local community-based organizations. Social workers and other mental health professionals are also available in health systems. Systematic use of a standardized question may also be valuable for health systems to determine the need for resources for patients who have strained caregivers. Despite evidence that support through programs such as REACH-II reduces caregiver depression and strain [27], caregivers do not routinely receive counseling [28].

These findings should be considered in the context of the study’s limitations including being conducted at a single site where all participants received an intervention. The sample size was limited and there was substantial loss to follow-up, which may have resulted in a conservative bias in the longitudinal outcomes (e.g., no difference in long-term nursing home placement when there actually was a difference). In addition, the study was not designed to answer some key questions about the prognostic importance of this symptom (e.g., predicting poorer health outcomes for caregivers). However, prior research [2, 3, 7] and the associated symptoms of caregiver strain, distress, and depressive symptoms in this study suggest that this symptom may have health implications for caregivers. Finally, because we used continuous measures to characterize associations and outcomes, we were unable to examine test characteristics such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of the “overwhelmed” question.

In summary, this study suggests that a single question assessing whether caregivers of PLWD regularly feel completely overwhelmed may prove valuable to identify caregivers who have high needs and may require more intensive dementia care services. Further research on the prognostic significance of this single item and its clinical value in directing caregivers to appropriate resources will determine its ultimate usefulness.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

The authors would like to acknowledge Katherine Serrano for her contributions to bring this study to completion.

Funders

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R21AG054681 and P30AG028748 and the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000124, the Commonwealth Fund, a national, private foundation based in New York City that supports independent research on health care issues and makes grants to improve health care practice and policy, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contract number HHSM 500-2011-00002I Task Order HHSM-500-T0009.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services, the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers, or staff. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David B. Reuben, Email: dreuben@mednet.ucla.edu.

Lee A. Jennings, Email: lee-jennings@ouhsc.edu.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures . Alzheimers Dement. 2021;2021:17(3). doi: 10.1002/alz.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stall NM, Kim SJ, Hardacre KA, Shah PS, Straus SE, Bronskill SE, Lix LM, Bell CM, Rochon PA. Association of Informal Caregiver Distress with Health Outcomes of Community-Dwelling Dementia Care Recipients: a Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019 Mar;67(3):609-617. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15690. Epub 2018 Dec 10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Goren A, Montgomery W, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Nakamura T, Ueda K. Impact of Caring for Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease or Dementia on Caregivers’ Health Outcomes: Findings from a Community Based Survey in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2016 Jun 10;16:122. 10.1186/s12877-016-0298-y. PMID: 27287238; PMCID: PMC4903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A, Ho R. Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Caregivers of Patients With Alzheimer Disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1034–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thunyadee C, Sitthimongkol Y, Sangon S, Chai-Aroon T, Hegadoren KM. Predictors of Depressive Symptoms And Physical Health in Caregivers of Individuals with Schizophrenia. Nurs Health Sci 2015 Dec;17(4):412-9. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12205. Epub 2015 Jun 17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Arthur PB, Gitlin LN, Kairalla JA, Mann WC. Relationship Between the Number of Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia and Caregiver Distress: What is the Tipping Point? Int Psychogeriatr. 2018 Aug;30(8):1099-1107. 10.1017/S104161021700237X. Epub 2017 Nov 16. PMID: 29143722; PMCID: PMC7103581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, Sands L, Lindquist K, Dane K, Covinsky KE. Patient and Caregiver Characteristics and Nursing Home Placement in Patients with Dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Does High Caregiver Stress Lead to Nursing Home Entry? with SK Long. Report to the Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy, April 2007. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2007/NHentry.pdf

- 9.Reuben DB, Evertson LC, Wenger NS, Serrano K, Chodosh J, Ercoli L, Tan ZS. The University of California at Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program for Comprehensive, Coordinated, Patient-Centered Care: Preliminary Data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013 Dec;61(12):2214-8. 10.1111/jgs.12562. Epub 2013 Dec 3. PMID: 24329821; PMCID: PMC3889469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Reuben DB, Tan ZS, Romero T, Wenger NS, Keeler E, Jennings LA. Patient and Caregiver Benefit From a Comprehensive Dementia Care Program: 1-Year Results From the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019 Nov;67(11):2267-2273. 10.1111/jgs.16085. Epub 2019 Jul 29. PMID: 31355423; PMCID: PMC6861615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Jennings LA, Hollands S, Keeler E, Wenger NS, Reuben DB. The Effects of Dementia Care Co-Management on Acute Care, Hospice, and Long-Term Care Utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020 Nov;68(11):2500-2507. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16667. Epub 2020 Jun 23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jennings LA, Laffan AM, Schlissel AC, Colligan E, Tan Z, Wenger NS, Reuben DB. Health Care Utilization and Cost Outcomes of a Comprehensive Dementia Care Program for Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 1;179(2):161-166. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5579. PMID: 30575846; PMCID: PMC6439653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Evertson LC, Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Zaila KE, Akram N, Romero T, Tan ZS. Caregiver Outcomes of a Dementia Care Program. Geriatr Nurs. 2021 Mar-Apr;42(2):447-459. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.02.003. Epub 2021 Mar 11. PMID: 33714024; PMCID: PMC8084597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the Reliability of the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):S127–32. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the reliability of the modified caregiver strain index. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):S127–132. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexopoulos GA, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao HF, Kuo CA, Huang WN, Cummings JL, Hwang TJ. Values of the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire in Individuals with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015 Jul;63(7):1448-52. doi:10.1111/jgs.13473. Epub 2015 Jun 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1):20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring Depression Treatment Outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peipert JD, Jennings LA, Hays RD, Wenger NS, Keeler E, Reuben DB. A Composite Measure of Caregiver Burden in Dementia: the Dementia Burden Scale-Caregiver. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018 Sep;66(9):1785-1789. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15502. Epub 2018 Aug 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Yun HKM, Curtis JR, et al. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using Medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Serv Outcome Res Methodol. 2010;10(1–2):100–110. doi: 10.1007/s10742-010-0060-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021. Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: a Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press 10.17226/26026. [PubMed]

- 28.Jennings LA, Tan Z, Wenger NS, Cook EA, Han W, McCreath HE, Serrano KS, Roth CP, Reuben DB. Quality of Care Provided by a Comprehensive Dementia Care Comanagement Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Aug 64(8):1724-30. 10.1111/jgs.14251. Epub 2016 Jun 29. PMID: 27355394; PMCID: PMC4988879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]