Abstract

Staff perceptions and attitudes regarding the introduction of the Reframing Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE) trauma-responsive school-wide approach were investigated in three Catholic primary schools in Victoria, Australia. School leaders, teachers, and support staff were interviewed regarding their experiences of the approach either individually or in focus groups. Educator attitudes towards trauma-responsive education was evaluated using the ARTIC–ED Scale, prior to and after participating in the six-month intervention. Qualitative data were interpreted using ecological analysis of the themes arising guided by the trauma informed principles and frameworks of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Trauma Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI). Findings indicated significant shifts towards trauma-responsive practice following the introduction of ReLATE. Strong themes emerged relating to the influence of improved trauma knowledge on perceptions of student behavior, consequent reported adaptations to behavior management practices, strengthened sense of trust and respect in the school climate, the centrality of leadership to effect change, and importance of school-fit to program uptake. Strengths and limitations of ReLATE are considered, along with implications for teacher professional learning, the role of leadership in effecting change and significance of perceived school-fit and collaboration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40653-021-00394-6.

Keywords: Trauma-informed, School professional learning, Practice change, Attitudes

The call for school environments to be responsive, trauma-informed, and safe contexts for learning and teaching (Chafouleas et al., 2019; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016) has never been more urgent in light of a global pandemic. Although some children live and learn in safe environments, others face childhood adversity and trauma that can result from experiences of family or neighbourhood violence, neglect and abuse, bullying, poverty, prejudice, war, or a natural disaster. Ongoing trauma can negatively impact a child’s emotional development, health, and well-being (Anda et al., 2010; Fonagy et al., 2013; Van der Kolk, 2007; Tobin, 2016). It can also give rise to challenges for schooling, such as severe behavioral, emotional, and relational concerns, low and irregular attendance, and disengagement from the social and academic aspects of learning (Baez et al., 2019; Blodgett & Lanigan, 2018; Cole et al., 2013; Perfect et al., 2016; Perkins & Graham-Bermann, 2012). Trauma disrupts essential learning processes including ability to focus and sustain attention, memory, recall and sequencing, problem solving, language development, and self-regulation skills (Finkelhor et al., 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2013; Perfect et al., 2016; Teicher & Khan, 2019). These experiences can have a considerable long-term impact on a child’s education and life outcomes, as well as the well-being and efficacy of their teachers.

In Australia, 72% of children are estimated to have been exposed to at least one adverse childhood experience such as bullying, family violence, sexual abuse, racism, neglect, death of a parent, parental mental-health or substance use issues, food or housing insecurity, or environmental disaster (Emerging Minds, 2020). Rates of exposure to trauma are disproportionately higher for vulnerable populations such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (AIHW, 2015; Gee et al., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2015) and children in out-of-home care (Mendis et al., 2015; Nathanson & Tzioumi, 2007).

In 2017, 40% of Australian primary and secondary school students were reported as disengaged, or at risk of disengaging, from education (Goss et al., 2017). Exposure to chronic trauma has been linked with disconnection from school, poor educational outcomes, and joblessness (Briggs et al., 2016; DuPaul et al., 2014; Gudmunson et al., 2013; Listenbee & Torre, 2012; Zimmerman et al., 2015). Schools are uniquely positioned to provide safe relational environments in which students have the opportunity for post-traumatic growth, relational safety, and learning success.

A trauma-informed school is seen to promote positive change by drawing significantly on educator knowledge of trauma in the daily moment by moment interactions within the school (Cole et al., 2013; Metz et al., 2007). Developing educator knowledge of trauma’s impact on learning and well-being becomes a catalyst for practice change (Avery et al., 2020; Chafouleas et al., 2016; Cole et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2018; Atallah et al., 2019). However, educators need professional training and specific skills to respond with confidence to trauma-impact on student learning and behavior (Alisic et al., 2012; Berger, 2019). A scoping review of school-based efforts supporting trauma-impacted students reports a critical need for evaluations of trauma-informed training and associated outcomes for staff and students (Stratford et al., 2020). In light of the current research base, this study aims to extend understanding of educator experience of trauma-informed training by reporting on the trauma-responsive school-wide approach, Reframing Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE), introduced in three Australian urban primary schools. Table 1 supplies operational terms and abbreviations in use throughout the paper.

Table 1.

Operational terms and abbreviations

| Abbreviation/Term | Operational Terms and Abbreviations |

|---|---|

| Educator | School leadership, teaching and administration staff |

| PL | Professional Learning: professional knowledge and in situ development of professional practice |

| ReLATE | Reframing Learning and Teaching Environments trauma-responsive school-wide approach |

| SAMHSA | Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration: USA government organisation to make substance use and mental health information, services, research & intervention guides widely accessible. Includes advisory councils, committees and resources |

| TLPI | Trauma Learning Policy Initiative: A collaboration of Harvard Law and Massachusetts Advocates for Children providing an inquiry-based process and a trauma-sensitive schools flexible framework for creating trauma-sensitive schools |

This paper uses the term trauma-responsive (TR) while recognising that the same principles are often embedded in other approaches referred to as trauma-informed, trauma sensitive, and trauma aware.

Re-framing Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE)

ReLATE is an Australian trauma-responsive school-wide approach which aims to create safe counter-stress learning environments in schools based on transformational relationships, by connecting trauma-responsive school policies with professional understanding and practice. ReLATE comprises a professional practice framework, trauma-responsive school policies and procedures, trauma training, and numerous components within four core domains (Fig. 1): (1) Reframing safe school cultures; (2) Learning via repeated and supported actions; (3) Teaching via transformative relationships; and (4) Environments of healing and flourishing. Throughout this paper the term ReLATE is used to refer to any number of the core components within these domains.

Fig. 1.

Re-Framing Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE) core components

ReLATE is underpinned by socio-ecological (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Crosby, 2015), trauma (Bloom, 2019; Shore, 2009; Siegel, 2012), and behavioral theories and educational research (CASEL, 2012; Hattie & Donoghue, 2016; Masters, 2018). These theories and principles were applied by MacKillop Education, Australia, over a period of six years in their specialist schools for students with significant behavioral needs. ReLATE as a model for general schools grew out of this practice. It is underpinned by four foundational concepts: (a) safety; (b) a counter-stress school environment; (c) enhanced teaching and learning; and (d) a sustainable whole-school culture (ReLATE, 2020). ReLATE comprises a range of elements common to trauma-informed approaches (Avery et al., 2020) including trauma training, adapted school policies and procedures, and a focus on relational connection, trust, and safety at every level of the school.

ReLATE is consistent with SAMHSA’s (2014) trauma-informed principles and ‘4 R’s’: realize, recognize, respond, and resist re-traumatizing. Firstly, through improved trauma understanding, all staff realize the prevalence and impact of trauma and see well-being as an essential pre-requisite for teaching and learning. Secondly, ReLATE aims to support staff to recognize the signs of trauma and develop an intentionality to both connect with and better understand students (ReLATE, 2020). ReLATE aims to support all school staff to create predictable, consistent, culturally appropriate, and trauma-responsive learning environments (ReLATE, 2020). Thirdly, ReLATE seeks to create responsivity to student needs within a cohesive school-wide environment using adapted behavior supports and restorative practices, and fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices. Fourthly, ReLATE aims to resist re-traumatization and re-triggering by providing learning environments that are safe physically, psychologically, culturally, and spiritually.

ReLATE is designed to be flexible and adaptive to the diversity of school communities whilst simultaneously providing a framework for achieving statutory requirements and congruent trauma-informed policies and practices. The use of a collaborative co-design approach similar to the inquiry-based process of the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI, Atallah et al., 2019), is intended to support the contextualization of the approach to individual schools. Capacity is built in schools to use the framework to support TR practices suited to their specific context. It includes the use of core implementation teams, class observations, and coaching supports. ReLATE is delivered as part of a Multi-Tiered System of Support similar to programs of mental health support Husabo et al. (2020) and school-wide positive behavior supports (Madigan et al., 2016), delivering a range of practices from universal preventative, to intensive targeted interventions for students with more complex needs.

Purpose of the Study

The current study aimed to better understand how the introduction of ReLATE was perceived by school staff in a general school context. The study was conducted as a partnership between State University in Victoria, Australia, and a Victorian Catholic Diocese. The diocese was considering ReLATE implementation in the diocese schools but wanted to obtain ‘first hand impressions’ from principals and teachers including any recommendations they may have before deciding on the investment in a diocese wide roll-out.

Research Questions

Drawing on the frameworks of SAMHSA and TLPI, the current study considered three central questions:

What was the impact of ReLATE on educators’ understanding of trauma-informed approaches and ability to recognise the signs of trauma (realize and recognize)?

What was the impact of ReLATE on educator capacity to implement school-wide, trauma-informed practices (resist and respond)?

How do staff perceive the impact of the ReLATE on student and staff well-being (recognize and respond)?

Method

Participants

Staff from Catholic primary schools which serve students aged 6–11 years, in Victoria, Australia, were invited to attend briefing sessions on ReLATE and associated commitments required by schools participating in the research. Principals open to using ReLATE in their schools expressed their interest to the Catholic Diocese. The Catholic Diocese then selected three urban schools (using internal criteria) from submissions to participate in the first offering of the ReLATE training. All data was de-identified by the Catholic authority prior to analysis.

Basic demographics of the participating schools are shown in Table 2, including the percentage of students whose second language was English. Non-reporting of detailed demographics such as ethnicity, teacher qualifications, and experience was necessary to maintain anonymity of the otherwise identifiable schools in this study. School A served a community with a high number of multi-ethnic refugees where English was a secondary language and the Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA, 2021) levels were significantly lower than the national average. Schools B and C served similar communities with socio-educational advantage levels around the national average. The percentage of Indigenous Australian students across the schools ranged from 0–2%. Economic disparities existed within each school. All teaching staff were post-graduates. Many of the participants had part-time roles, with the full time-equivalent number of staff totalling 53.7. A total of 20 staff (Males N = 2, Female N = 18) were either individually interviewed or part of a focus group. The sample size supported in-depth understanding of the intervention from the perspective of staff across the three schools (Guest et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Demographics of schools participating in the ReLATE professional learning

| School |

Staff (Full-time Equivalent) |

Staff (Head-count) |

1Female staff | 1Male staff | Students | Students with English as Second Language (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 28.7 | 40.0 | 266.0 | Over 80% | ||

| B | 14.2 | 20.0 | 112.0 | Under 40% | ||

| C | 11.0 | 16.0 | 90.0 | Under 40% | ||

| Total | 53.7 | 76.0 | 67 | 9 | 468.0 |

1No staff identified as gender diverse

Measures

A suite of measures was used including interviews and focus groups (FG), class observations, and observations of training sessions. Information was gained from documentation developed or used in the schools resulting from the training, e.g., using the Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011) tool for students to self-identify their mood. These materials were shared by staff members of the schools along with videos of staff implementing strategies and examples of the tools in use. Quantitative data was collected using the following measures:

School Climate Assessment

The ReLATE pre-implementation climate-assessment uses interviews and small FG’s to explore the strengths, challenges, and potential for implementing ReLATE. Areas of focus included school views on culture, gender, diversity, understanding of impact of stress and trauma on mental health, learning and behavior, school culture, leadership and values, problem solving strategies such as behavior management, strategies for building safety and belonging, and how staff well-being was viewed.

The Attitudes Towards Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale (Baker et al., 2016)

ARTIC is one of a few validated measures of a trauma-informed culture in the literature (Baker et al., 2016). It is a self-report tool used to evaluate a range of elements supporting trauma-informed methods. This includes staff beliefs regarding the use of trauma-informed practices, found to be a critical driver of trauma-informed practice that impacts the ‘moment to moment’ decision making of educators (Baker et al., 2016). The ARTIC–35ED is designed for use with schools commencing the journey towards being trauma-informed and produces an overall score and scores for five subscales as described in the categories provided in Table 3. Each question presented the participant with a choice between two statements to then score from 0 – 7, with higher scores indicating stronger positive views towards trauma-informed principles and practice.

Table 3.

Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) sub-scales measures (sourced from Baker et al., 2016)

| ARTIC-35 ED Subscale | Interpretation of the Subscale |

|---|---|

| 1 Underlying Causes of Problem Behavior and Symptoms | 1 Are student behaviors and symptoms viewed as adaptive and malleable or intentional and fixed |

| 2 Staff Responses to Problem Behavior and Symptoms | 2 Should responses to problem behavior focus on relationship, flexibility, kindness and safety as the agents of change or focus on accountability and consequences |

| 3 Empathy and Control | 3 Should staff be empathy-focused versus control-focused |

| 4 Self-Efficacy at Work | 4 Staff feel able and confident to meet the demands of working with traumatized students versus feel unable to meet the demands |

| 5 Reactions to the Work | 5 Do staff appreciate the effects of secondary trauma and seek support versus minimize the effects of secondary trauma and cope by ignoring or hiding the impact |

ARTIC scores are reported as means and percentile ranks. The mean score is the average of all the items on each ARTIC subscale. Percentile ranks (between zero and 100) show how the school compares to scores in the large representative sample used in the validity studies for the scale.

Staff Training Evaluation Form

A ReLATE training evaluation asked participants to confidentially rate what they had learned on a scale of ‘not useful’, ‘somewhat useful’, ‘quite useful’, or ‘very useful’.

Procedures

The Catholic Diocese pilot was conducted over a 10-month period extending from March to December 2019. The intervention period for each school lasted six months with varying start times accounting for the total study period. The overall structure of the study included four parts: (1) Baseline—School Climate Assessment and ARTIC-35ED Scale; (2) Intervention—ReLATE, delivered over six months, including coaching support and training implementation teams; (3) Data gathering—interviews, focus groups, school-wide observations (mid-intervention and at follow-up), documentation; and (4) Follow-up – ARTIC-35ED Scale.

A total of seven days of professional learning and consultation was offered to each school, six days of which were delivered within three-months of the start date. An initial climate assessment was conducted by MacKillop Institute consultants to better understand the strengths and needs of each school and their preparedness for implementing ReLATE, using FG’s and interviews with a range of core team staff, and a small number of parents and students. Prior to implementation at Timepoint 1 (T1), the ARTIC–35 ED Scale was administered to staff at each of the three schools (See Supplementary Table 1 for completion rates) and re-administered at Timepoint 2 (T2) following the six-months period of ReLATE intervention.

Delivery of ReLATE

Unlike much of traditional ‘one-and-done’ or short-course professional training, ReLATE builds safe and supportive professional learning communities to enhance collaboration and inquiry. A number of methods were utilized in the delivery of ReLATE, including whole-group direct teaching through lectures, small-group workshops, and individual and peer reflective practice. The content covered was referenced to Australian Professional Standards of Teaching and key Australian Education frameworks and included the following: trauma and attachment theory; basic neurobiology of the stress response; brain development, and learning; staff and student well-being; positive behavior support; relational trust; organisational change; cultural safety; and ReLATE components, as shown in Fig. 1. A hard copy of the learner guidebook was given to all participants, which reinforced the content of the ReLATE sessions. In addition, optional supplementary online learning materials were available to illustrate and extend on content delivered in the sessions. These activities occurred across a six-month period and included two all-staff whole-day training sessions, leadership, and core-team implementation training (four days), as well as a number of follow-up activities, including a network day for the core team comprising participants from all three schools. Direct support from ReLATE consultants on request via phone or in person was also available across the six month period.

Implementation Teams

A team of ReLATE ‘champions’ (core leadership team) was formed at each school to drive the implementation process. Members of each core team were selected by the school principal and they participated in an additional two days of learning led by the consultants, aimed to strengthen understanding of implementation processes and plan for the roll-out in their school. From a selection of 14 implementation tasks, core teams prioritized an area of focus for their school. The revision of existing school values and vision statements, policies, and procedures was recommended for the longer term. Networking activities included a Network Day for core teams at all three ReLATE schools to meet together for shared learning and practice development.

Interviews

Staff interviews were conducted at each school during school hours at two time points, Term 1 (May/June) and Term 4 (October). Principals at each of the schools (N = 3) were interviewed individually, with a number of school leaders (N = 17) who selected an individual interview over FG participation. Focus group participants included teachers who were part of the core team responsible for leading the ReLATE implementation in each school (well-being team staff and education support staff, along with teachers who participated in the professional learning). Schools were identified as School A (N = 7), School B (N = 4) and School C (N = 6). Global themes were used to guide individual and FG’s interviews including (a) understanding about the nature of trauma; (b) changes in individual teacher responses; (c) changes in school-wide responses; (d) integration of ReLATE with established school practices; (e) well-being of staff; and (f) quality of the ReLATE professional learning. Two researchers engaged in simultaneous notetaking during each interview and FG. All FG’s and individual interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Analysis

All data was de-identified prior to analysis. Thematic analysis was guided by (Bazeley, 2013) and the six-step process of Braun and Clarke (2013): (1) familiarization with data; (2) preliminary codes assigned to data using a priori themes from the content and aims of ReLATE documentation to describe content; (3) patterns or additional themes of codes that emerged inductively from the coding process from differing perspectives of the participants were discussed by the researchers across the different interviews; (4) themes reviewed and verified by cross-checking of affirming and disconfirming evidence within and across schools including reference to the summary memos written by each researcher (discrepancies or differing interpretations were discussed by the researchers and resolved until agreement was reached); (5) define and name themes; and (6) produce report.

The practice frameworks of SAMHSA and TLPI provided the analytical frame to evaluate the data, specifically, SAMHSA’s 4 R’s and six key principles of (a) safety; (b) trustworthiness and transparency; (c) trauma-impacted peer support; (d) collaboration and mutuality; (e) empowerment; and (f) responsive to cultural, historical, and gender issues (SAMHSA, 2014). The ARTIC–35ED Scale survey data was imported into a preformatted excel spreadsheet designed to automatically compute the mean subscale and total scale scores. Data were then collated using the median of the school-wide scores for each of the subscales. The scores are divided into the following three benchmark ranges based on percentile rank: Thrive range (75th to 100th percentile); Grow range (25th to 75th percentile); Learn range (0 to 25th percentile). Data were collated using the median of the school-wide scores for each of the subscales and the Overall score. Percentage ratings were used to present the findings from the Professional Learning Evaluation Form using the scale of ‘not useful’, ‘somewhat useful’, ‘quite useful’, or ‘very useful’.

Results

ReLATE School Climate Assessment

Participants in the climate assessment included teachers (N = 30), school leaders (N = 15), parents (N = 20), and students (N = 15–20 at each school). School A was assessed as having a focus on student well-being, physical safety, and community building. Teachers, whilst having a high degree of exposure to student trauma, showed limited understanding of trauma, and less cohesiveness, collaboration, and readiness for change. School B and C were found to have more robust systems of support, a distributive leadership approach, and existing social-emotional and positive behavior supports. All schools were grappling with how to meet the many different needs of their communities. The three schools worked to support physical safety, although understanding of the need to establish pre-conditions for emotional and cultural safety was limited, with a tendency to react to unsafe incidents rather than being proactive. All schools completed the initial two days of ReLATE professional learning, with a variable uptake for the three follow-up modules: School B – three days, School C – two days; School A – no attendance at the follow-up.

ARTIC Scale

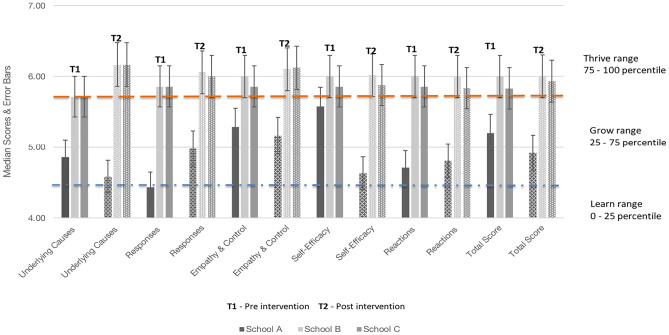

The attrition rates for completion of the ARTIC–35ED scale ranged between 13.33 – 26.67% with School A having the highest rate and School C the lowest (Supplementary Table 1). Attrition rates may be attributed to the timing of the follow-up survey aligning with the end of the school year. The results for all three schools are presented in Fig. 2 with individual school data provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 2.

ARTIC–35 ED scores pre- and post-ReLATE intervention for 3 schools

All Schools Pre and Post Intervention ARTIC Scores

Figure 2 represents the overall ARTIC and subscale scores for each of the three schools prior to the ReLATE professional development at T1 and post-intervention T2.

The standard range of data variability between the mean scores is indicated by the Standard Error bars. Equivalent scores were attained by Schools B and C within the Thrive range across four of the five subscales prior to intervention, indicating pre-existing staff strengths in focusing on the importance of relationship, flexibility, kindness, and safety as the agents of change (subscale 2); being empathy focused (subscale 3); and reactions to the work (subscale 4). Both Schools B and C scored at the top of the Grow range for understanding the underlying causes of behavior (subscale 1) with understanding shifting into the Thrive range at T2. No statistically significant increases in scores were found either at the subscale or Overall score level for Schools B and C. Self-efficacy (subscale 4) and reactions to the work (subscale 5) ranked in the Grow range, showing staff held a reasonable level of confidence working with trauma-impacted students, an appreciation of the effects of secondary trauma, and were likely to seek support rather than minimize the effects of secondary trauma.

Supplementary Table 2 illustrates how individual schools either made a positive change towards stronger trauma-informed attitudes and responses or sustained their position, with School A being the exception, scoring lower on self-efficacy post-intervention.

Subscale 1: Underlying Causes

Scores for School A showed a slight non-significant decrease, staying within the Grow range at T2. Scores for Schools B and C showed a progression from Grow into the Thrive range at T2, showing a positive trauma-informed shift in staff views about student behaviors and seeing behavior and symptoms as adaptive and malleable.

Subscale 2: Staff Responses to Problem Behavior and Symptoms

School A shifted from the Learn into the Grow range, the most marked of all score changes in a positive direction for School A and the greatest degree of positive subscale change across the total survey. This result shows a significant shift towards perceiving professional responses to problem behavior as needing to focus more on relationship, flexibility, kindness, and safety as the agents of change rather than issues of accountability, consequences, and rules. A minor shift further into the Thrive range was shown for Schools B and C, indicating that a relational focus to supporting behavior change was held and maintained in these schools with staff holding a robust trauma-informed view of students.

Subscale 3: Empathy and Control

Scores for School A remained in the Grow range at follow-up, with a minor non-significant negative shift. School B and C scores at T1 and T2 remained within the Thrive range, indicating staff held a strong view that professional behavior should be empathy-focused rather than control-focused.

Subscale 4: Self-Efficacy at Work

Scores for School A at follow-up show a significant reduction in staff sense of self-efficacy from the upper level of the Grow range at T1 to the lower level of the range at T2, beyond standard data variability. Scores for School B and School C both showed movement in a positive direction, remaining in the early stage of the Thrive range, indicating that staff felt both able and confident to meet the demands of working with traumatized students.

Subscale 5: Reactions to the Work

Although there was some increase for School A between T1 and T2 the scores remained within the early levels of the Grow range, indicating a growing appreciation of the effects of secondary trauma and the need to seek support. Both School B and School C maintained scores within the Thrive range from T1 to T2, indicating that staff had a good appreciation of the effects of secondary trauma and were likely to cope by seeking support.

The Overall Score, a mean global score reflecting answers on all items of the ARTIC Scale, shows School A remained within the Grow range at T2, indicating a non-significant decrease between pre/ post-intervention scores. The overall scores for both Schools B and C were within the Thrive range pre- and post-intervention. School C scored a non-significant increase from T1 to T2.

Summary Results

(1) staff at two schools held strongly positive trauma-informed practice views at baseline (T1), making positive, though non-significant shifts post-intervention; (2) no statistically significant increase was found in the Overall (total) score between the T1 and T2 phases across the schools; (3) the school ranking lowest pre-intervention made the greatest shifts on subscale scores post-intervention, with a statistically significant positive shift in responses to behavior and a significant decrease in staff sense of self-efficacy at follow-up.

Professional Learning Evaluation Forms

Out of 69 total participants in the professional learning, 57 completed and returned evaluation forms with 82% of participants rating the training as ‘Quite or Very Useful’ to their practice. The professional learning was rated as Very Useful by 75% of staff from School A, 66% of staff from School B, and 94% of staff from School C.

Educator Perceptions of ReLATE

The learnings and practice changes resulting from the ReLATE training were reported by school staff through individual and FG interviews, documentation relevant to ReLATE, and through researcher observations conducted across classrooms and playgrounds in the schools to consider:

The impact of ReLATE on educators’ understanding of trauma-informed approaches and ability to recognise the signs of trauma (realize and recognize);

The impact of the ReLATE on educator capacity to implement school-wide, trauma-informed practices (resist and respond);

How staff perceive the impact of the ReLATE on student and staff well-being (recognize and respond).

The following themes arose from the analysis of the data:

Understanding of Trauma. Congruous with SAMHSA’s realize precept, staff consistently reported that participation in the ReLATE professional learning had substantially developed their understanding of trauma and associated impacts. Participants reported new knowledge which they could apply to their students, themselves, and their colleagues. Various perceptions and presentations of trauma such as the neuro-developmental perspective, personal experiences, and reactions to trauma were repeatedly highlighted. An expansion of the concept of trauma was reported, which went beyond what educators perceived to be the commonly held view, as the following teacher explains:

Yes, I had thought trauma was more severe, whereas I think it was clearly explained that trauma had a range. (Teacher)

School-wide Responses. The development of school processes around responding to students and resisting re-triggering was perceived consistently by staff as extremely important in implementing ReLATE, as the following comments illustrate:

How do we communicate to all staff so there’s a consistent understanding? . . . So one of the first things that we did was put together a very brief snapshot, you know . . . this is how we act and play at our school and this is the terminology that we use so that it’s consistent . . . This is what we do. (Principal and teacher discussion)

Schools reviewed the key components of ReLATE that were being utilised in their school and the values that underpinned them. For example:

We then looked at our values and how could we simplify our values? And how could we encapsulate what we are doing as what’s really important to our school? The core team put this together and then we took it to the whole staff . . . And that will [then] be developed by students as much as adults for this school. (Teacher)

Several key strategies, introduced through the ReLATE modules were highlighted by staff as effective for achieving school changes. For example, the Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011), which is complementary to but not specifically part of ReLATE, provides a cognitive-behavioral approach to build student self-regulation. The approach was considered highly valuable as it provided a common language to communicate emotional states, which supported teachers to recognize students’ emotional struggles. In this way, because their interpretation of the behavior was different, teachers reported feeling more confident to respond in different ways. Safetyplans were also consistently rated as valuable for all students. Safetyplans are an individualized document of three or four interventions that the staff or student can implement when the student experiences difficult feelings, such as anxiety or anger (ex., put on headphones). Students develop their plans together with their teacher; are displayed either on a lanyard and/or on the class wall as visible reminders of their coping strategies. When students show signs of increased stress they may be prompted to activate their safety plan. When staff use their personal safety plans it normalizes times of stress while modelling proactive responses and how to return to a calmer state; however staff use of safety plans was variable. Teachers reported that displaying student safety plans and the zones of regulation charts supported them to avoid re-triggering students, and to respond to escalations using co-regulation and prompts to support students to self-regulate. Such actions were perceived to support students and their teachers by providing a common language for communicating how they were feeling, and strategies both students and staff viewed as being supportive:

We all have safety plans up now . . . that look the same as the children’s. All of the children have them up in their room. . . . that’s been really important, because it means that the specialists [also] have that common language when they have all of the different children. (Teacher)

The majority of the core team members agreed that the strategies introduced through ReLATE integrated with programs already established in the school and supported practice change. One teacher explained how responses to student behavior had changed since the professional learning:

. . .you have a little meeting with that child and you say, ‘Okay, what can we do?’ And so then you might build that in through their community meeting goal. You’d make that goal together, possibly . . . But if that child had in the meeting in the morning, indicated that they were in the yellow zone . . . that’s where I would go to their safety plan [saying] ‘You’ve told me this morning that you’re in the yellow zone because you told me that you were feeling really anxious. Let’s have a look at your safety plan, and see what we can do to help you move to the green zone and be ready for the day.’ (Teacher)

Overall, teachers and leadership felt ReLATE processes gave all students a voice and built their self-regulation development. It was universally agreed that ReLATE had positive benefits for teachers and all students and the benefits were visible. The following comment best illustrates the common view:

I’ve seen the most change that I’ve ever seen with any behavior management program, and I think the benefits are so high... It’s so valuable to have that time together to discuss, because in schools time is so scarce, …for me, the ReLATE program gives a scaffold to really help those kids who are not heard . . . it gives everyone a voice. I’ve been so impressed. . . [it’s] based on how people are feeling, and .. . . it’s teaching the children how to regulate themselves. (School Leader)

Equally, an administrative officer expressed changes in her experiences of student behavior:

. . . we’ve done many programs before in this school. . . and people at the beginning were like – and myself – very sceptical, like what can this give us that hasn’t been before? But the difference in the behavior from where I sit, the less [students we now] see with their behavior because they’re managed through them, being able to regulate it themselves, is enormous. (Administrative officer)

Teacher Responses to Behavior. Teachers and principals reflected on how realizing the prevalence and impact of trauma had shifted the way teachers viewed and responded not only to the behavior of students, but also to the behavior of colleagues, as comments from members of the core teams illustrate:

I think it’s shifted a lens in terms of how people view colleagues, how people view students, how people view our entire approach to the community. (Principal)

There has been a real shift in the way that teachers now view children’s behavior. So we’re no longer looking on ‘he’s frustrating, annoying and naughty’, it’s now . . . ‘there’s something happening for this child, if I . . . understand that then I might be able to respond more appropriately and might be able to bring about a better outcome for the young person’. (Teacher)

Teachers discussed how a shift in thinking changed their response not only to behaviors, but in a fundamental way to the student as a person. They provided a number of examples of their personal experiences with individual children to illustrate their views, as captured by the following:

I feel as if I don’t speak to the kids in an authoritarian kind of way[now], I can speak to them one to one, person to person ... It’s mutual respect. There was an incident …. I could have gone in, you know, boots and all, ‘Here boys, you’re doing this, bla bla bla’, but instead I took a different tack and spoke in a different way to the kids . . . and I think it takes away that fear that you are not going to be listened to . . . boys who are sort of really angry, they’re really anxious, but I think having the opportunity to have their voice and knowing that I wasn’t going to jump down their throat immediately and that I was going to listen, I think it just changed the whole thing and it was a much happier outcome for everybody. (School Leader)

Strategies valued in the training, and evidenced across all classes, included the use of safety-plans (Bloom, 1995), in conjunction with the Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011) to respond to student emotional states. This assisted in teaching and supporting emotional regulation, and in preventing re-triggering. Teachers varied, however, in the level of support they required to translate new knowledge into their class practice. For some teachers, their responsiveness to the training and subsequent use in their practice seemed dependent on the contextualisation of the new learning. A number of participants suggested that the professional learning should have included video examples of strategies or concrete examples of ‘safety plans’ that had been used elsewhere in mainstream schools, and wider student age-ranges in the examples provided would have been helpful. The following comment is illustrative:

. . . it would have been nice to see younger kids . . . [seeing] their safety plans to show what sort of things were on them, just to get a better idea, because . . . before we started putting [strategies] in place, I was very confused as to how it was going to really work.

Other teachers felt the training had supported them to interpret and translate it into their situation:

the thing that [a presenter] could do was . . . contextualise [information] and . . . was very good at acknowledging, ‘This is what we do, what do you reckon it’d look like here?’ Rather than, ‘This is what we do and it’s really important that you do it.’ (Teacher)

Well-being of Teachers. Staff well-being was recognized by members of the implementation teams as a valued and important focus of ReLATE to counter vicarious trauma effects from working with trauma-impacted students and families, combined with the often-overwhelming demands of their role, and stressors within their lives. The extent to which staff well-being initiatives had been realized in practice varied across schools. Statements from members of those schools which strategically implemented staff well-being as part of the change processes and everyday work are summed-up by a school leader:

The biggest part . . . was recognizing staff well-being when it comes to change and change processes. So it’s been slowed right down and we’ve been very overt in saying you have permission to slow things down in your classroom . . . We want you to put well-being at the forefront. (School Leader).

Three teachers discussed a lack of practical support for teacher self-care in their school, and the feeling of being ‘tasked’ to look after themselves; rather than collectively building a supported and resourced school practice, such as mindfulness:

We need to look after the teachers’ welfare as well as the children, because some of the things you hear, the stories . . . they're really damaging to teachers and it's hard for us to just walk away and say . . . ‘ I'm coming back to school tomorrow’ without thinking at home ‘What about us?’ (Teacher)

Impact of Leadership. Participants emphasized how leadership’s overtly prioritizing ReLATE and the involvement of the whole school, as fundamental for successful adaptation. This enabled staff engagement without having to find additional time in their schedules:

What helped me was that making space in what's considered important time, like [using] staff meeting time for a community meeting, because that then places the value on . . . if it's important enough to spend our time together doing this, it's important enough for me to make space for it . . . with the kids as well . . . if it's just delivered as another thing to do, then it is more like an add-on… rather than . . . we actually believe in it. (Teacher)

Discussion

Meeting the learning and well-being needs of trauma-impacted students is a critical challenge facing schools internationally. The primary aim of this study was to investigate educator perceptions of the impact of ReLATE on their understanding of TR approaches; ability to recognise the signs of trauma; capacity to implement school-wide trauma-responsive practices; and on student and staff well-being.

Using SAMHSA principles as an analytic tool provided strong evidence across schools of a deeper realization of the impact of trauma, and a shift in responses to student needs that supported emotional regulation and well-being, thus avoiding re-triggering. Strong evidence was also found for implementation of trauma-responsive classroom strategies, the introduction of teacher well-being interventions, and relationally-attuned discipline responses focused on self-regulation skill development. Three key themes arose from the analysis of the qualitative data:

Realization of trauma impact motivated practice change. Teachers, administrators, and school leaders credited ReLATE with deepening their understanding of trauma and recognizing its varied presentations and impact on students’ learning and social-emotional well-being, an outcome supported by the ARTIC data on understanding trauma. Adapted teacher responses to behavior was evidenced in the ARTIC and qualitative data relating to problem behavior, empathy, and control. The emergent literature suggests trauma understanding plays a significant role in assisting staff to reframe challenging behaviors and thereby adapt their responses. Although a shift in thinking may provide the impetus for practice change (Atallah et al., 2019; Haas, 2018; Perfect et al., 2016), other factors influence whether the practice change occurs and is sustained.

Practice-change was influenced predominately by perceived ‘fit’ and leadership. This study supports the findings of McIntyre et al. (2019) where teacher perception of ‘school-fit’ of the training was a strong moderator of translating training into practice. Acknowledgment of diverse views regarding ‘school-fit’ improved collaboration, buy-in, and shared ownership of implementing ReLATE. Equally, the strength of staff and school-wide responsiveness depended on leadership for practical implementation mechanisms and supports such as embedding strategies in everyday practice. The centrality of leadership support underpinning school practice change in this study is consistent with education literature (Hitt & Tucker, 2016). A close relationship was found between outcomes (i.e.,: positive teacher perceptions of ReLATE, depth of trauma understanding, and practice change) and a collaborative leadership style.

Positive response to iterative approach to collaborative co-design. The ReLATE pre-intervention assessment of school culture considered elements supported by the literature on professional learning uptake such as strengths, needs, leadership support, and readiness for change within each school context (Atallah et al., 2019; Avery et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2018). As the study progressed, an iterative and dynamic co-design process was evidenced, resulting in adaptations to delivery and strengthened sense of learning ‘fit’ to school contexts. Despite initial concerns from some staff, the majority view of participants was that the program had achieved both contextualization and collaboration. Collaborative co-design and attention to integrating strategies within existing school behavioral and well-being practices and routines aligns with TLPI’s framework and SAMHSA’s collaboration and mutuality principles.

Additional elements supporting change included increasingly consistent school-wide approaches to behavior, a shared language for adults and students to discuss emotions and coping skills, an improved sense of trust and communication within the schools consistent with SAMHSA’s principles of trustworthiness and transparency, and empowerment and collaboration. Well-being is considered a critical element in the delivery and sustainability of TR school approaches (Bloom, 2019; Luthar & Mendes, 2020) and was viewed as a critical element of ReLATE. Actualization of well-being processes was strongly linked to leadership initiatives and integration into school-wide practice change, capitalizing on the everyday schedule and routine for teachers. Actioning initiatives conveyed to educators that their well-being was forefront in leadership concerns, particularly when allowing teachers to manage change in ways that avoided a sense of becoming overwhelmed.

Safety, the central precept of ReLATE, was evidenced in the qualitative data referencing emotional regulation strategies and an improved sense of trust and respect in the school environment. Teachers recognized a perspective shift personally and in other staff, along with overall school culture change, with a strong emphasis on tolerance, respect, and increased empathetic responses to student behavior that had previously been viewed as problematic or disruptive. Significantly, educators’ understanding of safety shifted from a focus on physical aspects, to incorporate emotional, psychological, cultural, moral, gender, and spiritual safety, as conceptualized by ReLATE. Cultural safety, prioritized in ReLATE and core to being TR (Blaustein & Kinniburgh, 2018; Courtois & Ford, 2013) was not referenced by participants, possibly reflecting the interview process or factors on a spectrum of cultural bias or blindness to culturally attuned environments in the schools, where culturally responsive practices are the norm.

A number of factors may account for school outcome variance, including demographics, leadership support, and length of exposure to training. Implementation strength in School A may have been effected by a combination of reduced exposure to ReLATE (Fixsen et al., 2010) and lower readiness for change (Jones et al., 2018). Teacher-related factors such as ability to translate training into practice may also have impacted outcomes, with limited exposure to training sufficient for some teachers, whilst for others an extended exposure is necessary. A reduction in teacher sense of self-efficacy at follow-up (School A) is not unusual and often relates to a lower sense of mastery following exposure to new learning and the expectation of applying the learning (Klassen & Chiu, 2010; Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, 2009). Importantly, staff sense of efficacy is understood to influence attitudes toward, and rates of application of new practices, and can be improved through staff consultation (Atallah et al., 2019; SAMHSA, 2014). All schools committed to a second year of ReLATE suggesting a level of confidence in the approach to improve outcomes for students and staff. Measuring shifts in educator mindsets and practices and relationships between staff, students, and families may prove a valuable way for ongoing evaluation of a TR culture (Cole, 2019).

SAMHSA and TLPI frameworks provided a meaningful approach to informing data analysis and had utility in examining whether or not particular ReLATE initiatives aligned with current guidelines. The use of qualitative methods in the study also enabled context-related factors to be considered (QUALRIS, 2018). ReLATE offered a flexible, contextualized approach which included elements supported by current TR guidelines and implementation science, including pre-implementation assessments, educator-led implementation teams, and coaching support (Albers & Pattuwage, 2017; Proctor, 2012) demonstrated as effective in supporting teacher practice change (Artman-Meeker et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2015). ReLATE adopts a multi-tiered support system which is considered necessary to meet the intended outcomes of a trauma-informed approach as defined by SAMHSA (Chafouleas et al, 2016). In addition, ReLATE supports staff professional growth through a multi-tiered approach, including building professional learning communities understood to support teacher pedagogical knowledge, shared vision, teacher well-being, and importantly, critical thinking and examination of assumptions about teaching and learning (Owen, 2016; Stoll & Seashore Louis, 2007). The extent to which changes across the schools are embedded and sustained will be influenced strongly by leadership, and the allocation of teacher time and support to maintain and extend upon current gains experienced during this study.

Limitations

Findings from this study should be considered within the limitations of a moderate sample size and the specific context of the study (Catholic Education), limiting the generalizability of findings to other settings or schools. Additionally, the short implementation period in this study design is a significantly limiting factor when trying to determine the impact of a training and support process, with the second round of data collection less than four months following completion of the professional learning. Missing data sets in the ARTIC–35ED scale and attrition rates resulted in gaps in the post-intervention data. Use of the ARTIC-45ED as the follow-up measure in future studies would benefit from additional subscales measuring personal and systems-wide support for a TR approach. The perspectives of parents, students, and community organisations would add depth to findings, as would data on ways educators’ personal exposure to trauma may impact on educator engagement and perceptions of ReLATE. Notwithstanding these limitations, the outcomes and overall response from the participants in these schools in response to ReLATE was highly positive. All of the schools showed evidence of initial growth in considering ways to further develop trauma-responsivity. This was clearly linked with school-based practices and with what had been identified as needing to change.

Future Recommendations

In light of the limitations of this study, there are some potential directions for future research and practice with larger sample sizes. The collection of evidence systematically gathered and analysed by staff at the school level would enhance understanding of the value of the introduced practices in relation to student attendance, behavioral incidents, academic outcomes (e.g. learning progression points), and measures of well-being (e.g. validated student’ well-being measures such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) (Goodman, 2001). Future studies would be strengthened by assessing staff work satisfaction and well-being. It is imperative for schools, given the multiple stressors of a global pandemic, that research considers how tools used in broader social services and health arenas, may be utilised advantageously in the school context. For example, it is posited that trauma-responsive staff supervision and incident de-briefs, and the onsite availability of therapists or coaches would further support educator well-being and TR practice.

Improved understanding of the concept of trauma through the lens of culture, is essential if approaches to healing, growth, and change are to be relevant beyond dominant cultures. Therefore, research on culturally competent practices is also urgently required to build TR schools. Finally, the adoption of school-based leadership roles with responsibility for embedding TR practices and data-gathering would serve to guide and track practice change within schools, adding rigor to studies and informing iterative cycles of change (Taylor et al., 2014).

Conclusion

The literature indicates that schools can be influential contexts to counter the impacts of exposure to trauma and adversity (Atallah et al., 2019; Berger, 2019; Chafouleas et al., 2016; Stokes & Turnbull, 2016). Importantly, this study reports on the ReLATE approach, which evolved within specialist campus settings, and is now utilized in more generic school contexts. Teachers, principals, and administrators recognized changes in their own and colleagues’ perspectives, their school culture, and teacher practice, with a strong shift towards an emphasis on tolerance, respect, and increased empathetic responses to student behavior that had previously been viewed as problematic or disruptive. Perceived school-fit of the program and leadership support and integration with existing school practices were key drivers of change. This study contributes to emerging evidence on the use of trauma-informed professional learning to shift the thinking of educators and move teacher and school-wide practices toward trauma-responsivity. The results of this study support further debate and discussion within the professional community on the dynamic nature of trauma-responsive programs in schools and adapting to school contexts.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This research received no specific funding from any public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Informed Consent

The study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 17826). We confirm that the ethical standard of informed consent was followed in all matters.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- AIHW, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2015). The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: 2015. Cat. no. IHW 147. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved August 8, 2020 from 10.25816/5ebcbd26fa7e4

- Albers, B., & Pattuwage, L. (2017). Implementation in education: Findings from a scoping review. Melbourne: Evidence for Learning. Retrieved November 30, 2020 from http://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/evidence-informed-educators/implementation-in-education

- Alisic E, Bus M, Dulack W, Pennings L, Splinter J. Teachers’ experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:98–101. doi: 10.1002/jts.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Butchart A, Felitti VJ, Brown DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2010;39(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artman-Meeker K, Hemmeter ML, Snyder P. Effects of distance coaching on teachers’ use of pyramid model practices: A pilot study. Infants & Young Children. 2014;27(4):325–344. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0000000000000016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah DG, Koslouski JB, Perkins KN, Marsico C, Porche MV. An Evaluation of Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative’s (TLPI) Inquiry-Based Process: Year Three. Boston University, Wheelock College of Education and Human Development; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M. & Skouteris, H. (2020). Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baez JC, Renshaw KJ, Bachman LEM, Kim D, Smith VD, Stafford RE. Understanding the necessity of trauma-informed care in community schools: A mixed-methods program evaluation. Children in Schools. 2019;41:101–110. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdz007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Brown S, Wilcox P, Overstreet S, Arora P. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale. School Mental Health. 2016;8(1):61–76. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9161-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley P. Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies. SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berger E. Multi-tiered Approaches to Trauma-Informed Care in Schools: A Systematic Review. Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein, M., & Kinniburgh, K. (2018). Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Publications. ISBN 978–1–4625–3704–4.

- Blodgett C, Lanigan JD. The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2018;33(1):137–146. doi: 10.1037/spq0000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL. Creating Sanctuary in the School. Journal for a Just & Caring Education. 1995;1(4):403–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL. Trauma theory. In: Richard B, Haliburn J, King S, editors. Humanising mental health care in Australia: A guide to trauma-informed approaches. Routledge; 2019. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London, UK: SAGE.

- Briggs, A. R. J., Coleman, M., & Morrison, M. (2016). Research Methods in Educational Leadership and management. Sage Publications Ltd. L.A. 10.4135/9781473957695

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen, & T.N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), The international encyclopaedia of education (pp. 1643–1647). (2nd ed.). New York: Elsevier Sciences.

- Chafouleas S, Johnson A, Overstreet S, Santos N. Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health. 2016;8:144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chafouleas SM, Koriakin TA, Roundfield KD, Overstreet S. Addressing childhood trauma in school settings: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health. 2019;11:40–53. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-9256-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SF, Eisner A, Gregory M, Ristuccia J. Helping traumatized children learn: Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Massachusetts Advocates for Children; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. How Can Educators Create Safe and Supportive School Cultures? Massachusetts Advocates for Children; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2012). 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs (Preschool and elementary school edition). Chicago, IL: CASEL.

- Courtois, C., & Ford, J. (2013). Treating complex trauma: A sequenced relationship-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Crosby SD. An ecological perspective on emerging trauma-informed teaching practices. Children and Schools. 2015;37(4):223–230. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdv027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul, G. J., Reid, R., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Power, T. J. (2014). Assessing ADHD symptomatic behaviors and functional impairment in school settings: Impact of student and teacher characteristics. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(4), 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emerging Minds. (2020). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Summary of evidence and impact. National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health. Retrieved November 21, 2020 from: https://emergingminds.com.au/resources/background-to-aces-and-impacts/

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence and crime and abuse: Results from the National survey of children’s exposure to violence, 169(8), 746-54. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fixsen DL, Blase K, Duda M, Naoom S, Van Dyke M. Implementation of evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Research findings and their implications for the future. In: Weisz J, Kazdin A, editors. Implementation and dissemination: Extending treatments to new populations and new settings. 2. Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Gergely, G., et al. (2013). The developmental roots of borderline personality disorder in early attachment relationships: A theory and some evidence. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 23(3), 412–459.

- Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A. & Kelly, K. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. In: Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R. (eds). Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. (2nd ed). Canberra: Department of The Prime Minister and Cabinet, 55–68.

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss, P., Sonnemann, J., & Griffiths, K. (2017). Engaging students: creating classrooms that improve learning. Grattan Institute. Victoria, Australia. ISBN: 978–1–925015–98–0.

- Gray HL, Contento IR, Koch PA. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum, ‘Choice Control and Change’. Health Education Research. 2015;30(2):248–261. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmunson, C. G., Ryherd, L. M., Bougher, K., Downey, J. C., & Zhang, D. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences inIowa: A new way of understanding lifelong health. Findings from the 2012 Iowa behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Commissioned by the Central Iowa ACEs Steering Committee. Retrieved Nov. 27, 2020 from http://www.iowaaces360.org

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, L. (2018). Trauma-informed practice: The impact of professional development on school staff. (Doctoral Thesis) University of St. Francis. Retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2101893622?accountid=12528

- Hattie, J., Donoghue, G. (2016). Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model. npj Science Learn, 1(16013). Retrieved October 30, 2020 from 10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hitt DH, Tucker PD. Systematic Review of Key Leader Practices Found to Influence Student Achievement: A Unified. Review of Educational Research. 2016;86(2):513–569. doi: 10.3102/0034654315614911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husabo E, Haugland BSM, Wergland GJ, Maeland S. Providers’ Experiences with Delivering School-Based Targeted Prevention for Adolescents with Anxiety Symptoms: A Qualitative Study. School Mental Health. 2020;12:757–770. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09382-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ICSEA. (2021). Guide to Understanding the Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. https://www.myschool.edu.au/media/1820/guide-to-understanding-icsea-values.pdf

- Jones, W., Berg, J., & Osher, D. (2018). Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI): Trauma-Sensitive Schools descriptive study: Final report. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research.

- Klassen RM, Chiu MM. Effects on Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job Stress. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102(3):741–756. doi: 10.1037/a0019237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers, L. (2011). ZONES of Regulation. Think Social Publishing. Available at http://www.zonesofregulation.com/index.html

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven De Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J. et al. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 25 August 2020, https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/9DA8CA21306FE6EDCA257E2700016945/%24File/child2.pdf

- Listenbee, R. L., & Torre, J. (2012). Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Washington, D.C.: Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Retrieved January 19, 2020 from https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/24586/Children_and_exposure_to_violence.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Luthar SS, Mendes SH. Trauma-informed schools: Supporting educators as they support the children. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2020;8(2):147–157. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1721385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan K, Cross RW, Smolkowski K, Strycker LA. Association between schoolwide positive behavioural interventions and supports and academic achievement: A 9-year evaluation. Educational Research and Evaluation. 2016;22(7–8):402–421. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2016.1256783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masters, G. N. (2018, October). Gonski, learning and the case for change. Teacher. Retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/columnists/geoff-masters/gonski-learning-and-the-case-for-change

- McIntyre, E. M., Baker, C. N., Overstreet, S., & The New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2019). Evaluating foundational professional development training for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Psychological Services, 16(1), 95–102. 10.1037/ser0000312 [DOI] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., Hill, E. D., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslaysky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815–830. e14. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mendis, K., Gardner, F., & Lehmann, J. (2015). The education of children in out-of-home care. Australian Social Work, 68(4).

- Metz AJ, Blasé K, Bowie L, editors. Implementing evidence based practices: Six ‘‘drivers’’ of success. Child trends: Research-to-results brief. The Atlantic Philanthropies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson D, Tzioumi D. Health needs of Australian children living in out-of-home care. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2007;43(10):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen S. Professional learning communities: Building skills, reinvigorating the passion, and nurturing teacher wellbeing and “flourishing” within significantly innovative schooling contexts. Educational Review. 2016;68(4):403–419. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2015.1119101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect MM, Turley MR, Carlson JS, Yohanna J, Saint Gilles MP. School related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990–2015. School Mental Health. 2016;8:7–43. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins S, Graham-Bermann S. Violence exposure and the development of school-related functioning: Mental health, neurocognition, and learning. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 2012;17(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. Implementation science and child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(1):107–112. doi: 10.1177/1077559512437034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUALRIS. (2018). Qualitative research in implementation science. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

- ReLATE. (2020). An Introduction to ReLATE: Reframing Learning & Teaching Environments. The MacKillop Institute. Retieved November 10, 2020 from https://www.mackillop.org.au/institute/relate

- Shore AN. Relational trauma and the developing right brain: An interface of psychoanalytic self-psychology and neuroscience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1159:189–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: how relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. (2nd ed.) New York. NY. Guilford.

- Stokes H, Turnbull M. Evaluation of the Berry Street Education Model: Trauma informed positive education enacted in mainstream schools. University of Melbourne Graduate School of Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll L, Seashore Louis K, editors. Professional learning communities: Divergence, Depth, & Dilemmas. Open University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stratford B, Cook E, Hanneke R, Katz E, Seok D, Steed H, Fulks E, Lessans A, Temkin D. A scoping review of school-based efforts to support students who have experienced trauma. School Mental Health. 2020;12:442–477. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09368-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed J. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2014;23:290–298. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher, M. H., & Khan, A. (2019). Childhood Maltreatment, Cortical and Amygdala Morphometry, Functional Connectivity, Laterality, and Psychopathology. Child Maltreatment, 24(4), 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tobin, M. (2016). Childhood trauma: Developmental pathways and implications for the classroom. Retrieved August 8, 2020 from http://research.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/20/

- Tschannen-Moran M, McMaster P. Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal. 2009;110(2):228–245. doi: 10.1086/605771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2007). The developmental impact of childhood trauma. In L. J. Kirmayer, R. Lemelson, & M. Barad (Eds.), Understanding trauma: Integrating biological, clinical and cultural perspectives (pp. 224–241). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press. 10.1017/CBO9780511500008

- Zimmerman, E. B., Woolf, S. H., & Haley, A. (2015). Population Health: Behavioral and Social Science Insights: Understanding the Relationship Between Education and Health: A Review of the Evidence and an Examination of Community Perspectives. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Retrieved January, 29, 2020 from http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculumtools/populationhealth/zimmerman.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.