Abstract

Suicide in youth exacts significant personal and community costs. Thus, it is important to understand predisposing risk factors. Experiencing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as child maltreatment (CM-ACE), and the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder has been identified as a risk factor of suicidal behaviors among adults. Theoretical models of suicide suggest that the presence of painful experiences such as CM-ACEs increase the risk of suicidal behaviors. The relation between child maltreatment, post-traumatic stress symptom clusters (PTSS) and suicidal behaviors has not been explicitly examined among youth. The present study examined the relations between CM-ACEs, PTSS clusters, and suicidal behaviors in a clinical population of children. Children, male, ages 6 to 14, enrolled in a residential treatment program completed self-report measures to evaluate variables of interest. Path analyses revealed statistically significant direct effects of CM-ACEs and PTSS clusters on suicidal behaviors. Significant total indirect effects and marginally significant individual indirect effects of intrusion and avoidance symptoms were observed for the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behavior. Findings suggest that symptoms associated with specific PTSS clusters might help explain the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behavior, and therefore, present important implications for clinical practice and future research.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Child maltreatment, PTSD, Suicide

Introduction

Suicidal behaviors were once considered rare occurrences in children and adolescents, yet rates of suicide attempts and completions in children and adolescents in the United States have steadily increased over the past several decades (Centers for Disease Control, 2018; Kennebeck & Bonin, 2020). Although these prevalence rates have risen across multiple age groups, the sharpest increase in the number of deaths by suicide has been observed in early adolescence (Nock et al., 2008; World Health Organization, 2017). The devasting impact of youth suicide cannot be understated and affects the individual, family, friends, and community (Cerel et al., 2008; Sveen & Walby, 2008). Furthermore, the direct and indirect costs of youth suicide on society are substantial and account for estimated annual costs up to $58 billion (Shephard et al., 2016).

Historically, research on suicidality has focused on adults and, to a lesser extent, adolescents. The increased prevalence of suicidal behaviors in younger populations has resulted in more research and greater clinical attention to suicide risk in prepubescent children (Tishler et al., 2008), with researchers often examining behaviors that fall along a broader spectrum of suicidality (Bursztein & Apter, 2009; Karthick & Barwa, 2017). Collectively referred to as suicidal behaviors, this spectrum includes threats of suicide, non-suicidal self-injury of varying intensity (Heilbron et al., 2010), suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Bursztein & Apter, 2009; Karthick & Barwa, 2017). Given that each type of suicidal behavior denotes some level of risk, conceptualizing suicidal behaviors more broadly in younger populations might be advantageous. These types of behaviors are relatively common in children as young as 6 years of age, especially those with mental health concerns (Kovess-Masfety et al., 2015; Whalen et al., 2015), and research suggests that one third of children who experience suicidal ideation eventually attempt suicide (Nock et al., 2013). Furthermore, the progression from ideation to action in youth is much shorter than what is typically observed in adults (Lipari et al., 2015) highlighting the importance of the prevention and early intervention of suicidal behaviors in children and adolescents.

Childhood Adversity

There are numerous theoretical models of suicide. One model that is gaining empirical support is the Three-Step Theory (3ST; Klonsky & May, 2015). The 3ST captures the spectrum of suicidal behavior by using an ideation-to-action framework to conceptualize suicide risk. Within this framework, it is suggested that painful experiences (i.e., aversive thoughts, emotions, sensations, and/or experiences), especially when experienced chronically, precipitate the development of suicidal behaviors. These behaviors are exacerbated when painful experiences are combined with a sense of hopelessness (Klonsky & May, 2015).

Consistent with the 3ST, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are one set of risk factors that repeatedly emerge as related to suicidal behavior (Felitti et al., 1998). ACEs include experiences such as exposure to violence, household dysfunction, abuse and neglect, and traumatic loss (Felitti et al., 1998). ACEs are relatively common, with nearly 50% of youth reporting exposure to at least one type of ACE (Bethell et al., 2017). Extensive research suggests that ACEs are individually and collectively associated with a myriad of negative outcomes including suicidal ideation, attempts, and completions during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Merrick et al., 2017; Serafini et al., 2015). However, ACEs themselves do not portend a greater risk of suicidal behavior. Instead, the way in which ACEs impact biological, cognitive, and emotional development and functioning are thought to increase the risk of suicidal behavior (e.g., impairments in executive functioning and emotion regulation; Erwin et al., 2000; Luby et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2017, 2019a).

The extent to which ACEs influence these developmental processes and thereby the risk of suicidal behavior appear to be shaped by various characteristics of ACE exposure. For example, the type, frequency, chronicity, and severity of ACE exposure have all been associated with suicidal behaviors (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 2016; Dunn et al., 2013), and exposure to multiple types of ACEs has been identified as one of the most common predictors of suicidal behavior (Felitti et al., 1998; Serafini et al., 2015).

While many ACE characteristics have been associated with greater risk of suicidal behavior, an increasing number of studies have identified a specific type of ACEs – child maltreatment (CM) – as an especially strong risk factor for suicidal behavior in children and adolescents (e.g., Cha et al., 2018). CM is understood as a chronic and severe form of interpersonal trauma (e.g., De Bellis, 2005) and collectively refers to experiences of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect during development (e.g., Leeb et al., 2008). CM is a fairly common experience, with an estimated one-third of all children in the United States experiencing maltreatment before the age of 18 (Kim et al., 2017). This prevalence rate is especially concerning given that CM accounts for an estimated 67% of population risk for suicide (Dube et al., 2003). When considering the prevalence of CM, it is also important to consider the high rates of co-occurrence among different types of maltreatment (Finkelhor et al., 2007). Research has shown that experiencing one type of maltreatment significantly increases the likelihood of experiencing other types (Aebi et al., 2017; Debowska & Boduszek, 2017; Finkelhor et al., 2007), and exposure to multiple types of maltreatment is associated with a greater risk for adverse outcomes such as earlier age at first suicide attempt (Finkelhor et al., 2007; Hoertel et al., 2015).

CM is associated with deleterious effects on neurobiological, behavioral, emotional, social, and cognitive development and functioning (Teicher et al., 2016). Alterations in these domains occur secondary to ACE exposure and impact the expression of both internalizing and externalizing problems (Cicchetti et al., 2000). They are thought to account for the link between CM and suicidal behavior (Dvir et al., 2014; Richey et al., 2016). Furthermore, CM can also negatively affect interpersonal functioning in ways that might result in disrupted connectedness (Cicchetti et al., 2000). The 3ST Model contends that suicide risk is not only influenced by the experience of painful or adverse experiences but also by one’s connectedness (e.g., social connections, attachments, sense of purpose within the community, etc.; Klonsky & May, 2015). For example, insecure attachment styles, dysfunctional family dynamics, and social isolation have been linked to suicidal behavior in maltreated children and adolescents (Cha et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2013; Rytila-Manninen et al., 2018). Similarly, the effects of CM on cognitive functioning including delayed processing skills and negative cognitions (e.g., low self-esteem and feelings of hopelessness) have been associated with suicidal behaviors in youth as well (Duprey et al., 2018; Meadows & Kaslow, 2002).

Post-Traumatic Stress

A preponderance of research has identified mental health disorders and psychopathology as mediators of the relation between ACEs and suicidal behavior (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2000). Depression has most often been considered one of the strongest predictors of suicidal behavior (e.g., Goldberg et al., 2019; Hodgman & McAnarney, 1992). While this link remains well-established, recent research also supports a relation between suicidal behaviors and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) independent of depression and other mental health disorders (Ruby & Sher, 2013; Wilcox et al., 2009). PTSD is a mental health disorder characterized by alterations in cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological processes following a traumatic event. These alterations are represented as symptoms within four distinct symptom clusters: intrusive symptoms, negative alterations in mood and cognition, altered arousal and reactivity, and avoidance of trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and external reminders (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

Stressful and traumatic events are especially potent risk factors for suicidal behavior in children and adolescents (Yildiz, 2020), which are exceedingly common in youth with PTSD (Panagioti et al., 2015). In fact, studies have shown that 60% of adolescents with PTSD exhibit suicidal ideation (Soylu et al., 2013), and 50% have attempted suicide (Panagioti et al., 2015). Even among children and adolescents with similar trauma histories, those diagnosed with PTSD exhibit more suicidal behaviors than those without the diagnosis (de Lima Bach et al., 2018). Research also indicates that poly-victimization, or exposure to multiple types of CM, is associated with greater PTSD symptom severity (Ford et al., 2013; Suliman et al., 2009) and exacerbates the risk of suicidal behaviors (Kearney et al., 2010).

Despite theoretical and empirical support for the interrelatedness of CM, PTSD, and suicidal behaviors, research examining a network of associations among these variables in child and adolescent populations is sparce, especially in the context of specific PTSD symptom clusters. However, an emerging albeit equivocal body of research provides support for unique associations between specific PTSD symptom clusters and suicidal behavior in adults. Several studies have identified hyperarousal symptoms as a single PTSD-related predictor of suicidal behavior (e.g., Pennings et al., 2017), and both avoidance and intrusive symptoms have emerged as the strongest PTSD-related predictor of suicide in other studies (Barr et al., 2016; Selaman et al., 2014). These findings help establish a foundation for investigating unique relations between suicidal behavior and individual PTSD clusters in children and adolescents. Specifically, examination of post-traumatic stress related to CM and suicidal behaviors, not only in the context of diagnosed PTSD but also as specific symptom clusters, is warranted.

The Present Study

There is substantial support linking the experience of child maltreatment ACEs (CM-ACEs) and suicidal behavior in children and adolescents, collectively referred to as “youth” in the present study. Although an expansive body of literature has identified a myriad of risk factors associated with each of these variables, CM and youth suicide both continue to represent clear public health crises. Broad conceptual and empirical connections between CM, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal behaviors have been established. However, no known research has examined potential inter-relations among these variables in children and adolescents. Furthermore, most existing research on CM has distinguished between specific types of abuse and neglect, thereby failing to account for the high rates of poly-victimization often observed in high-risk populations (Andrews et al., 2015; Ford et al., 2013). Similarly, most research on youth suicide differentiates between types of suicidal behaviors (e.g., ideation, threats, gestures, attempts, etc.), which might not adequately account for the overlap in behaviors along the suicide risk spectrum nor for the potentially rapid progression from suicidal ideation to action in children and adolescents (Lipari et al., 2015; Shain, 2018). Finally, PTSD represents substantial risk for suicidal behavior among those with a history of CM, yet little is known about how specific symptom clusters might influence this risk. To address these gaps in the literature, the goal of the present study was to examine relations between CM, post-traumatic stress symptom (PTSS) clusters, and suicidal behavior in a sample of high-risk male youth. Both CM and suicidal behaviors were examined as unitary constructs, and PTSS were disaggregated into individual clusters. It was hypothesized that two PTSS clusters – intrusion and avoidance symptoms – would have significant indirect effects on the relation between CM and suicidal behavior.

Method

Participants

Participants included male youth living in a residential treatment setting (N = 86). Most participants were in state custody and had a confirmed history of child maltreatment. Inclusion criteria included being a male between the ages of 6 and 14 with a verbal intelligence score of at least 75. Exclusion criteria included having active psychosis at the time of data collection. An age range of 6-14 years was used to represent the period of development between middle childhood to early adolescence, which has been identified as an important transitional period for the onset and exacerbation of suicidal behaviors (Musci et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019).

Procedure

Data were originally collected as part of a quality assurance program in the school setting of the residential treatment facility. This program was designed to evaluate the use of positive behavior supports on child outcomes in the classroom. Students were given the option to complete a brief battery of self-report measures within the context of daily classroom procedures. Those who chose to participate were given the option of completing the measures independently or with the help of a trained research assistant. Participants provided assent for their responses to be used for research purposes in addition to the quality assurance program. Limits of confidentiality were discussed, and any notable concerns that emerged during data collection were discussed with the child’s teacher and/or primary therapist. Data were collected within two weeks of the child being admitted to the treatment facility to minimize the effects the treatment (e.g., positive behavior supports, medication, individual, and group therapy, etc.) and/or living in a safe, structured setting might have on the variables of interest.

Measures

Child Maltreatment

The Adverse Childhood Experiences – Short Form (ACE-SF; Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998) is a self-report measure of lifetime exposure to adversity during early development. Respondents provide “yes” or “no” responses to indicate whether they have experienced events including physical and emotional neglect, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and several types of household dysfunction. In the present study, some of the language from the original ACE-SF was modified to be developmentally appropriate for this sample while retaining the content of the original questions. For example, items on the modified version of the ACE-SF included questions such as, “Were you hit, punched, or kicked very hard at home?” and “Did you ever see someone get beaten up?”. The ACE-SF was used in this study to obtain a CM score by calculating a sum score of items that assessed physical, sexual, and psychological abuse and physical and emotional neglect. Higher scores indicated exposure to more types of CM.

Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS)

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 (PTSD-RI-5; Elhai et al., 2013; Steinberg et al., 2004; 2013) is a self-report questionnaire used to assess the presence and severity of PTSS. The PTSD-RI-5 reflects diagnostic criteria for PTSD according to the DSM-5 and assesses symptoms within each PTSD symptom cluster – intrusive, avoidance/numbing, negative or distorted cognitions, hyperarousal, and dissociative features (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Respondents rate on a 5-point Liker scale ranging from 0 (None of the time) to 4 (Most of the time) how often they have experienced symptoms within the past month. The PTSD-RI-5 is scored using an algorithm that yields symptom cluster and overall PTSS scores, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of PTSS. Psychometric properties of the PTSD-RI-5 are considered “good to excellent” with high internal consistency (α = .86-.91), convergent validity with other PTSD diagnostic measures, and high test-retest reliability (r =.75; Elhai et al., 2013; Modrowski et al., 2019; Steinberg et al., 2013). In the present study, the PTSD-RI-5 yielded a high internal consistency of α = .93.

Suicidal Behavior

Suicidal behavior was measured using the Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire – Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001). The SBQ-R consists of four questions that assess lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts, the frequency of ideation, suicidal gestures, and perceived likelihood of future suicide. Respondents rated Likert scales for each item and a total sum score was computed with higher scores representing more suicidal behaviors. The SBQ-R is considered a valid instrument for screening of suicidal behavior, particularly in research (Cotton et al., 1995). Internal consistency is moderate in both clinical (α = .75) and nonclinical (α = .80) samples (Osman et al., 2001). Internal consistency of the SBQ-R in this study was α = .82.

Data Analysis Plan

Using SPSS software (IBM Version 26, 2019), assumptions for Pearson’s correlations and regression models were tested. Pearson’s bivariate correlations were used to examine relations between age, race, and all study variables of interest. Next, a path model was specified using MPLUS 8.4 software (Muthen & Muthen, 2017) to estimate the relations between study variables simultaneously. Specifically, suicidal behavior was specified as the outcome variable and regressed on CM-ACEs and all four PTSS clusters. Direct effects of CM-ACEs on each PTSS cluster and suicidal behavior were also estimated, and covariances among PTSS clusters were estimated to yield a fully saturated model with path coefficients rather than fit indices. Indirect effects were investigated, as well. The total indirect effect of PTSS clusters on the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behaviors was examined, and PTSS clusters were examined as multiple mediators of the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behavior.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants were an average of 10.44 years of age (SD = 2.29), and the racial/ethnic distribution of the sample is representative of the area in which data were collected. Most participants had a documented history of more than one type of CM-ACE (54.2%). At the time of admission, the average number of diagnoses was 3.14 (SD = 0.99). Twenty-three percent of children in the sample were diagnosed with a trauma or stress-related disorder (see Table 1). Participants endorsed an average of 2.16 (SD = 1.06) types of CM-ACEs, and 68.6% of the sample endorsed at least one CM-ACE. The prevalence of self-reported CM in this sample is commensurate with those reported in other residential youth settings (e.g., 71%; Greger et al., 2015). Participants reported higher scores on both Total PTSS and on the individual PTSS cluster scores compared to other clinical youth populations at-risk for PTSS (Kaplow et al., 2020). Diagnostic criteria for PTSD were met by 47% of the sample based on the PTSD-RI-5, and approximately two thirds of the sample endorsed clinically significant symptoms within at least one PTSS cluster. Nearly two thirds of the sample also endorsed any past or present suicidal behavior, and 12% of participants met the SBQ-R cutoff for high suicide risk. The average SBQ-R score was 2.86 (SD = 3.23), which is lower than the reported average SBQ-R score in the inpatient adolescent male sample on which the SBQ-R was validated (M = 4.42, SD = 2.32; Osman et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variables | n | % | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 51 | 59.3 | -- |

| African American | 30 | 34.9 | -- |

| Other | 5 | 5.8 | -- |

| Documented history of abuse and/or neglect | 59 | 68.6 | -- |

| Physical abuse | 34 | 46.6 | -- |

| Psychological abuse | 8 | 11.0 | -- |

| Sexual abuse | 22 | 20.1 | -- |

| Neglect | 42 | 57.5 | -- |

| State custody at time of admission | 58 | 69.0 | -- |

| Diagnoses at time of admission | |||

| ADHD | 69 | 81.2 | -- |

| Other neurodevelopmental disorder | 35 | 41.2 | -- |

| Mood disorder | 36 | 42.4 | -- |

| Anxiety disorder | 11 | 12.9 | -- |

| Trauma- or stress-related disorder | 23 | 27.4 | -- |

| Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorder | 59 | 69.4 | -- |

| Child maltreatment ACE score | -- | -- | 2.16 (1.06) |

| PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5* | -- | -- | -- |

| Total PTSS score | -- | 46.5 | 39.20 (18.39) |

| PTSS – Intrusion | -- | 66.3 | 10.08 (6.18) |

| PTSS – Avoidance | -- | 65.1 | 4.15 (2.60) |

| PTSS – Negative Mood/Cognitions | -- | 64.0 | 12.62 (6.49) |

| PTSS – Altered Arousal/Reactivity | -- | 61.6 | 12.12 (6.02) |

| Suicidal behaviors | -- | -- | 2.86 (3.23) |

| Any past or present suicidal behavior | -- | 65.1 | -- |

| Exceeds cutoff for high-risk | -- | 12.0 | -- |

PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSS Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms

*UCLA-PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5

Bivariate Correlations

None of the demographic variables were significantly associated with CM-ACEs, PTSS, or suicidal behavior. Significant correlations emerged in the expected directions for most study variables. CM-ACEs was positively associated with all PTSS clusters except for avoidance. Suicidal behaviors were positively and significantly associated with CM-ACEs and with all four PTSS clusters. The strength of these associations fell in the moderate range (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child maltreatment | - | ||||

| PTSS – Intrusion | .41** | - | |||

| PTSS – Avoidance | .24* | .58** | - | ||

| PTSS – Negative Mood/Cognitions | .47** | .72** | .45** | - | |

| PTSS – Altered Arousal/Reactivity | .40** | .70** | .44** | .71** | - |

| Suicidal behaviors | .40** | .46** | .42** | .34** | .36** |

PTSS Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms

*p < .05;** p < .01

Path Model

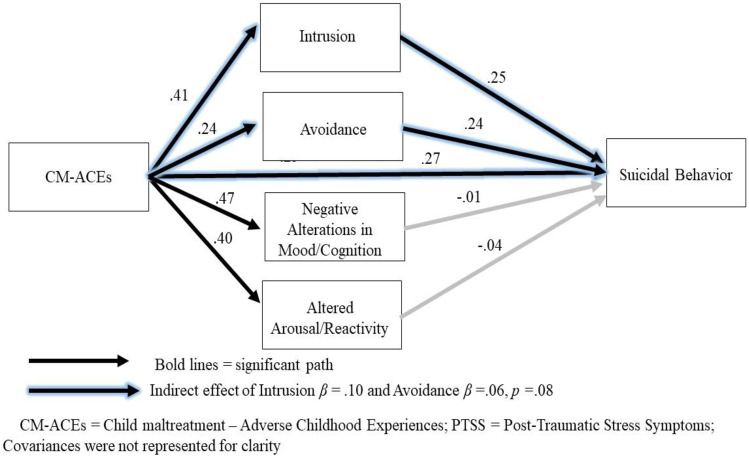

Results of the path model specified to examine direct and indirect effects of CM-ACEs and PTSS clusters on suicidal behavior indicated that the total direct effects within this model were significant (b = 1.22, SE = .27, β = .40, p < .01; Fig. 1). CM-ACEs were significantly related to all four PTSS clusters (b’s = .06 - 5.38, SE’s = .24 - 1.05, β’s = .24 - .47, p’s < .01) and to suicidal behaviors (b = .81, SE = .34, β = .27, p = .01). Suicidal behaviors were significantly related with the avoidance (b = .30, SE = .13, β = .24, p = .01) and intrusion (b = .13, SE = .07, β = .23, p = .05) PTSS clusters. The total indirect effect within the model was significant (b = .16, SE = .08, β = .15, p < .05), and a marginally significant indirect effect of intrusion and avoidance symptoms on the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behavior emerged (b’s = .06 - .10, SE = .03 - .06, β’s = .05 - .10, p’s = .08).

Fig. 1.

Path analysis model with standardized path coefficients

Discussion

Suicide in children and adolescents is a devastating outcome that represents ongoing personal, familial, and public crises. To inform suicide prevention effectively, investigation of risk factors that precede and exacerbate the development of suicidal behaviors is imperative. CM has been repeatedly implicated in the etiology of suicide (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 2016; Serafini et al., 2015). To advance suicide prevention efforts in maltreated children, it is crucial to investigate pathways through which CM might relate to suicidal behaviors. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine PTSS clusters as potential risk factors that might influence the relation between CM and suicidal behaviors in a high-risk sample of male youth.

The results from the present study fill several gaps in current literature by examining both CM and suicidal behaviors as broader constructs to account for the effects of poly-victimization and the spectrum of suicidal behaviors observed in children and adolescents. This study also examined PTSS outside the context of diagnosed PTSD to expand upon current research that is generally limited to individuals diagnosed with PTSD (e.g., Ruby & Sher, 2013) thereby often failing to account for barriers to diagnostic services, sex differences in PTSD diagnoses, and developmental factors that complicate the diagnostic process in children and adolescents.

Consistent with extensive literature enumerating the negative sequalae of CM and with study hypotheses, results demonstrated positive associations between CM-ACEs, all four PTSS clusters, and suicidal behaviors. Furthermore, the total indirect effect of PTSS clusters on the relation between CM-ACEs and suicidal behavior was significant. There was also a significant indirect effect of the intrusive PTSS cluster, and a marginally significant indirect effect emerged for the avoidance PTSS cluster. These results were consistent with the study hypotheses but were in contrast to other research examining the influence of PTSS clusters on suicidal behaviors in adults where support for the role of intrusive and/or avoidance symptoms has been equivocal. For example, while there is some support for the association between these two symptoms clusters and suicidal behaviors (Barr et al., 2016; Selaman et al., 2014), Brown et al. (2018) reported only weak but significant relations between avoidance and suicidal behavior and noted this relation was not as strong as those observed between suicidal behaviors and other PTSS clusters. Some studies have even reported that avoidance/numbing symptoms are not significantly associated with suicide risk unlike other PTSS clusters (Chou et al., 2020). However, these studies were performed with adults, and discrepant findings between the present study and existing literature might be related to developmental differences.

Reexperiencing and Avoidance Symptom Clusters and Suicidal Behavior

Existing research suggests that traumatic events during early development tend to be encoded as fragmented, sensory memories that lack contextual information. This is likely due to limited cognitive and linguistic capacity to encode these memories in early childhood (Salmon & Bryant, 2002). As such, CM might easily lend itself to the development of intrusive symptoms, which are often described as fragmented and highly perceptual experiences (Brewin et al., 2010; Ehlers, 2010). The vivid perceptual nature of these symptoms often contributes to feeling that past traumatic events are happening “here and now” which might be especially distressing for maltreated children and adolescents due to the effects of CM on cognitive and emotion regulation processes. These findings are supported by research that suggests an increase in the frequency and intensity of suicidality during periods of heightened emotional distress as well as the presence of poor distress tolerance in maltreated children (Benuto et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2019b; Viana et al., 2019). These results are also consistent with the 3ST model of suicide (Klonsky & May, 2015).

Intrusive and avoidance symptoms have been described in the literature as paired constructs with PTSD, with avoidance often considered a compensatory mechanism against intrusive symptoms (e.g., McFarlane, 1992). For children and adolescents, the greater intensity of intrusive symptoms might portend greater efforts to avoid reminders of traumatic events. However, avoiding reminders of emotionally salient events requires significant emotional and cognitive inhibition, which are likely limited in maltreated youth due to the effects of CM on these regulatory processes (McLaughlin et al., 2015) beyond the limitations already accounted for by development level. Moreover, attempts to avoid reminders of traumatic events might not only be ineffective at managing the associated distress, but they might inadvertently exacerbate it. Previous research suggests that avoidance symptoms of PTSD are strongly associated with and can even present as internalizing problems in children and adolescents (Johnson et al., 2020), thereby possibly exacerbating the risk of suicidal behaviors in maltreated children.

Clinical Implications

Findings from the present study yield several clinical implications. First is the importance of applying a developmental framework to conceptualizing post-traumatic stress in youth. Several findings from the present study were divergent from studies that examined similar relations in older adolescents and adults. However, these discrepancies were easily conceptualized within a developmental framework, thereby highlighting the importance of developmentally sensitive and informed approaches for identifying and treating post-traumatic stress in children and adolescents. Such an approach will enhance the ability to detect PTSS in youth, especially when they might otherwise be masked by other internalizing and externalizing problems. For example, PTSD-related hyperarousal is often mischaracterized as hyperactivity and impulsivity related to ADHD (Blank, 1994; Weinstein et al., 2000), but developmentally appropriate trauma-informed approaches would allow clinicians to attribute these symptoms more accurately to post-traumatic stress when appropriate.

Second, findings from this study emphasize the need to broaden the conceptualization of post-traumatic stress beyond a categorical approach. The average level of PTSS endorsed by participants in this study exceeded those reported in most clinical youth samples (e.g., Kaplow et al., 2020), yet only 27% of these participants had a diagnosis of PTSD. This is not to say that these children were misdiagnosed but to highlight the potentially deleterious effects associated with PTSS even in the absence of symptoms consistent with current diagnostic criteria for PTSD. One way to broaden our approach to understanding and treating PTSS is by adapting trauma-specific interventions to address other clinical phenomena such as aggression. For example, symptoms associated with negative alterations in mood/cognitions could be related to externalizing behaviors such as non-compliance, hostile attributions, or aggression. Thus, interventions that address alterations in mood and behavior by reshaping cognitive processes and challenging maladaptive beliefs, both of which are key elements of Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy (TF-CBT; Cohen et al., 2012), might be an effective approach to treating childhood aggression. Similarly, intrusive symptoms have been related to aggression, as well. Since symptoms within this cluster are largely related to emotional and cognitive dysregulation, it might be advantageous to incorporate the gradual exposure and trauma narrative components of TF-CBT when addressing aggression. The Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) Framework (Arvidson et al., 2011) should also be considered when working when with youth who have experienced complex developmental trauma. This framework might be especially useful for helping children who have been treated in a residential setting following multiple disruptions in their primary care systems to reintegrate in an outpatient setting and within a new or previously maladaptive caregiver context.

Finally, it might also be beneficial to incorporate trauma-specific approaches into suicide prevention and mitigation. Results suggest that, for children and adolescents, reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms are most strongly related to suicidal behaviors; thus, trauma-specific interventions such as gradual exposure therapy facilitated by trauma narratives might decrease these PTSS symptoms, thereby attenuating the risk of suicidal behaviors. Although the use of trauma-specific interventions to treat suicidal behaviors might not be appropriate for all at-risk clinical populations, it might be an effectual approach to treating a broad range of symptoms in children and adolescents with a history of maltreatment.

Limitations

Findings from the present study provide important contributions to literature informing suicide prevention in children and adolescents, but some limitations should be considered. First, the sample size for the present study was relatively small, and cross-sectional data were used. Thus, indirect effects should not be interpreted as true mediation. Future research should replicate this study using longitudinal data. Second, the present study examined the effects of CM specific to male youth. A male-only sample was used for several reasons including the overrepresentation of boys in residential treatment facilities (Sedlak & Bruce, 2010) and that boys are also less likely than girls to be diagnosed with PTSD (Breslau et al., 2004), which suggests that male youth are also likely under-represented in research examining post-traumatic stress. Thus, male youth represent a particularly vulnerable population, and the examination of these risk factors in this population was paramount. However, there is limited generalizability of results to female youth, especially considering well-documented gender differences on all study variables (e.g., Asscher et al., 2015). Future research should examine differential effects of sex on these relations. Additionally, the present sample represents a unique subset of youth who generally have high care needs, multiple psychiatric comorbidities, and complex history of adverse experiences. Future research should include comparison samples from normative, outpatient, and inpatient youth populations to provide a framework for understanding high-risk samples like the one in the present study. Future studies might also replicate this study in other referred youth samples with a broader range of support needs. Finally, the present study only examined two characteristics of ACE exposure (e.g., type and polyvictimization) that were thought to influence the development of long-term negative outcomes. Future research highlighting the effect of other ACE characteristics such as the chronicity, frequency, or severity of ACE exposure would be helpful in furthering our understanding of the consequences of ACE exposure across developmental periods.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Elizabeth McRae and Laura Stoppelbein. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Elizabeth McRae and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data and Code Availability

Data and coding information is available by request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The current study was approved through the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Institutional Review Board.

Consent Statement

Parental consent was not required because data was collected through program evaluation; however, assent was obtained from participants to have their data used as a part of the research study.

Consent to Publish

All authors have agreed to the submission of this manuscript for publication at the Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth McRae, Email: emcrae@uab.edu.

Laura Stoppelbein, Email: lastoppelbein@ua.edu.

Sarah O’Kelley, Email: sokelley@uab.edu.

Shana Smith, Email: sasmith@jsu.edu.

Paula Fite, Email: pfite@ku.edu.

References

- Aebi M, Mohler-Kuo M, Barra S, Schnyder U, Maier T, Landolt MA. Posttraumatic stress and youth violence perpetration: A population-based cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry. 2017;40:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AR, Jobe-Shields L, Lopez CM, Metzger IW, de Arellano MAR, Saunders B, Kilpatrick DG. Polyvictimization, income, and ethnic differences in trauma-related mental health during adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:1223–1234. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asscher JJ, Van der Put CE, Stams GJJM. Gender differences in the impact of abuse and neglect victimization on adolescent offending behavior. Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30:215–225. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidson, J., Kinniburgh, K., Howard, K., Spinazzola, J., Strothers, H., Evans, M., Andres, B., Cohen, C., & Blaustein, M. (2011). Treatment of complex trauma in young children: Developmental and cultural considerations in application of the ARC intervention model. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 4, 34–51.

- Barr NU, Sullivan K, Kintzle S, Castro CA. PTSD symptoms, suicidality and non-suicidal risk to life behavior in a mixed sample of pre- and post-9/11 veterans. Social Work in Mental Health. 2016;14:465–473. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2015.1081666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benuto LT, Yang Y, Bennett N, Lancaster C. Distress tolerance and emotion regulation as potential mediators between secondary traumatic stress and maladaptive coping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0886260520967136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell CD, Carle A, Hudziak J, Gombojav N, Powers K, Wade R, Braveman P. Methods to assess adverse childhood experiences of children and families: Toward approaches to promote child well-being in policy and practice. Academy of Pediatrics. 2017;17:S51–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank AS. Clinical detection, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;17:351–383. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Gregory JD, Lipton M, Burgess N. Intrusive images in psychological disorders: Characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. Psychological Review. 2010;117:210–232. doi: 10.1037/a0018113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LM, Lucia VC. Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: Lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:889–898. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Contractor A, Benhamou K. Posttraumatic stress disorder clusters and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research. 2018;270:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursztein C, Apter A. Adolescent suicide. Current Opinions in Psychiatry. 2009;22:1–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283155508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2018). Suicide rates rising across the U.S. CDC Newsroom. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0607-suicide-prevention.html

- Cerel J, Jordan JR, Duberstein PR. The impact of suicide on the family. Crisis. 2008;29:38–44. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha CB, Franz PJ, Guzmán ME, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Annual Research Review: Suicide among youth - epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2018;59:460–482. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou PH, Ito M, Horikoshi M. Associations between PTSD symptoms and suicide risk: A comparison of 4-factor and 7-factor models. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;129:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2016). Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective in Developmental Psychopathology (Vol. 3): Maladaptation and Psychopathology, (pp. 1–55): John Wiley & Sons.

- Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. L., & Maughan, A. (2000). An ecological–transactional model of child maltreatment. In A. J. Sameroff, M. Lewis, & S. M. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology (p. 689–722). Kluwer Academic Publishers. 10.1007/978-1-4615-4163-9_37

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (Eds.). (2012). Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. Guilford Press.

- Cotton CR, Peters DK, Range LM. Psychometric properties of the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire. Death Studies. 1995;19:391–397. doi: 10.1080/07481189508252740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:150–172. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Bach S, Molina MAL, Jansen K, da Silva RA, de Mattos Souza LD. Suicide risk and childhood trauma in individuals diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2018;40:253–257. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debowska A, Boduszek D. Child abuse and neglect profiles and their psychosocial consequences in a large sample of incarcerated males. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;65:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles W, Anda RF. Childhood abuse and neglect and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N, Rosand J, Smoller JW. Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: Results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:955–964. doi: 10.1002/da.22102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprey EB, Oshri A, Liu S. Childhood maltreatment, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation in a low-ses emerging adult sample: The moderating role of heart rate variability. Archives of Suicide Research. 2018;23:333–352. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1430640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir Y, Ford JD, Hill M, Frazier JA. Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2014;22:149–161. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A. Understanding and treating unwanted trauma memories in posttraumatic stress disorder. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie. 2010;218:141–145. doi: 10.1027/0044-3409/a000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Layne CM, Steinberg AS, Vrymer MJ, Briggs EC, Ostrowski SA, Pynoos RS. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index. Part 2: Investigating factor structure findings in a national clinic-referred youth sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:10–18. doi: 10.1002/jts.21755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BA, Newman E, McMackin RA, Morrissey C, Kaloupek DG. PTSD, malevolent environment, and criminality among criminally involved male adolescents. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2000;27:196–215. doi: 10.1177/0093854800027002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards VK, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:23–39. doi: 10.1017/S003329179900135X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Grasso DJ, Hawke J, Chapman JF. Poly-victimization among juvenile justice-involved youths. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37:788–800. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, X., Serra-Blasco, M., Vincent-Gil, M., Aguilar, E., Ros, L., Arias, B., Courtet, P., Palao, D., & Cardonera, N. (2019) Childhood maltreatment and risk for suicide attempts in major depression: A sex-specific approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology,10. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1603557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greger, H. K., Myhre, A. K., Lydersen, S., & Jozefiak, T. (2015). Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heilbron N, Compton JS, Daniel SS, Goldston DB. The problematic label of suicide gesture: Alternatives for clinical research and practice. Professional Psychology, Research, and Practice. 2010;41:221–227. doi: 10.1037/a0018712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgman CH, McAnarney ER. Adolescent depression and suicide: Rising problem. Hospital Practice (Office ed.) 1992;27:73–76. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1992.11705400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Franco S, Wall MM, Oquendo MA, Wang S, Limosin F, Blanco C. Childhood maltreatment and risk of suicide attempt: a nationally representative study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;76:916–923. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac OS, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Johnson D, McLennan JD, Heron J, Coleman I. The relationship between profiles and transitions of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children and suicidal thoughts in early adolescence. Psychological Medicine. 2020;50:2566–2574. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow, J. B., Rolon-Arroyo, B., Layne, C. M., Rooney, E., Oosterhoof, B., Hill, R., Steinberg, A. M., Lotterman, J., Gallagher, K. A. S., Pynoose, R. S. (2020). Validation of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5: A developmentally informed assessment tool for youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59, 186–194. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Karthick, S., & Barwa, S. (2017). A review on theoretical models of suicide. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research, 3. 10.7439/ijasr.v3i9.4382

- Kearney, C. A., Wechsler, A., Kaur, H., & Lemos-Miller, A. (2010). Posttraumatic stress disorder in maltreated youth: A review of contemporary research and thought. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 46–76. 10.1007/s10567-009-0061-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kennebeck, S., MD, & Bonin, L. (2020, May). Suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents: Evaluation and management. Retrieved January 22, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/suicidal-ideation-and-behavior-in-children-andadolescents-evaluation-andmanagement

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among us children. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107:274–280. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2015;8:114–129. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovess-Masfety V, Pilowsky DJ, Goelitz D, Kuijpers R, Otten R, Moro MF, Bitfoi A, Koç C, Lesinskiene S, Mihova Z, Hanson G, Fermanian C, Pez O, Carta MG. Suicidal ideation and mental health disorders in young school children across Europe. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;177:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb, R. T., Paulozzi, L., Melanson, C., Simon, T., & Arias, I. (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, GA.www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/CM_Surveillance-a.pdf.

- Lipari, R., Piscopo, K., Kroutil, L. A., & Miller, G. K. (2015). Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR2-2014/NSDUH-FRR2-2014.pdf [PubMed]

- Luby JL, Barch D, Whalen D, Tillman R, Belden A. Association between early life adversity and risk for poor emotional and physical health in adolescence: A putative mechanistic neurodevelopmental pathway. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171:1168–1175. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC. Avoidance and intrusion in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180:439–445. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Peverill M, Gold AL, Alves S, Sheridan MA. Child maltreatment and neural systems underlying emotion regulation. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows LA, Kaslow NJ. Hopelessness as mediator of the link between reports of a history of child maltreatment and suicidality in African American women. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:657–674. doi: 10.1023/A:1020361311046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ports KA, Ford DC, Afifi TO, Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;69:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, Renshaw KD. The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: A systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Review of Clinical Child and Family Psychology. 2013;16:146–72. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrowski CA, Chaplo SD, Kerig PK, Mozley MM. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic overmodulation and undermodulation, and nonsuicidal self-injury in traumatized justice-involved adolescents. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2019;11:743–750. doi: 10.1037/tra0000469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musci, R. J., Hart, S. R., Ballard, E. D., Newcomer A., Van Eck, K., Ialongo, N., & Wilcox, H. (2016). Trajectories of suicidal ideation from sixth through tenth grades in predicting suicide attempts in young adulthood in an urban african american cohort. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46, 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 8. Muthén & Muthén; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiological Review. 2008;30:133–54. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8:443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti M, Gooding P, Triantafyllou K, Tarrier N. Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:525–537. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0978-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings SM, Finn J, Houtsma C, Green BA, Anestis MD. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large military sample. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2017;47:538–550. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey A, Brown S, Fite PJ, Bortolato M. The role of hostile attributions in the associations between child maltreatment and reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Aggression and Maltreatment Trauma. 2016;25:1043–1057. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1231148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby E, Sher L. Prevention of suicidal behavior in adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2013;25:283–293. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytila-Manninen M, Haravuori H, Frojd S, Marttunen M, Lindberg N. Mediators between adverse childhood experiences and suicidality. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;77:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon K, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: The influence of developmental factors. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:163–188. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak, A., & Bruce, C. (2010). Youth’s characteristics and backgrounds: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227730.pdf.

- Selaman, Z. M. H., Chartrand, H. K., Bolton, J. M., & Sareen, J. (2014). Which symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder are associated with suicide attempts?. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Serafini G, Muzio C, Piccinini G, Flouri E, Ferrigno G, Pompili M, Girardi P, Amore M. Life adversities and suicidal behavior in young individuals: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;24:1423–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0760-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain BN. Youth suicide: The first suicide attempt. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;57:730–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, D. S., Gurewich, D., Lwin, A. K., Reed, G. A., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: Costs and policy implications. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46. 10.1111/sltb.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Soylu N, Alpaslan AH, Ayaz M, Esenyel S, Oruç M. Psychiatric disorders and characteristics of abuse in sexually abused children and adolescents with and without intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34:4334–4342. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer M, Decker K, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Kim S, Ghosh C, Ostrowski SA, Gulley K, Briggs EC, Pynoos RS. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index: Part I. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JG, Glenn CR, Esposito EC, Cha CB, Nock MK, Auerbach RP. Cognitive control deficits differentiate adolescent suicide ideators from attempters. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017;78:614–621. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JG, Polanco-Roman L, Duarte CS, Auerbach RP. Neurocognitive processes implicated in adolescent suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Applying an RDoC framework for conceptualization. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2019;6:188–196. doi: 10.1007/s40473-019-00194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JG, Shields GS, Esposito EC, Crosby EA, Allen NB, Slavich GM, Auerbach RP. Life stress and suicide in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2019;47:1707–1722. doi: 10.1007/s10802-019-00534-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman S, Mkabile S, Fincham D, Ahme R, Stein D, Seedat S. Cumulative effect of multiple trauma on symptoms of posttruamtic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveen CA, Walby FA. Suicide survivors' mental health and grief reactions: a systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviors. 2008;38:13–29. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. National Reviews. Neuroscience. 2016;17:652–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishler, C. L., Reiss, N. S., & Rhodes, A. R. (2008). Suicidal behavior in children younger than twelve: A diagnostic challenge for emergency department personnel. Academic Emergency Medicine, 14. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb02357.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Viana AG, Raines EM, Woodward EC, Hanna AE, Walker R, Zvolensky MJ. The relationship between emotional clarity and suicidal ideation among trauma-exposed adolescents in inpatient psychiatric care: does distress tolerance matter? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2019;48:430–444. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1536163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein D, Staffelbach D, Biaggio M. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Differential diagnosis in childhood sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:359–378. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen DJ, Dixon-Gordon K, Belden AC, Barch D, Luby JL. Correlates and consequences of suicidal cognitions and behaviors in children ages 3 to 7 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:926–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts in a community sample of urban American young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:305–311. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Disease and injury country mortality estimates, 2000–2015. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html.

- Yildiz M. Stressful life events and adolescent suicidality: An investigation of the mediating mechanisms. Journal of Adolescence. 2020;82:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X., Tian, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2019). Trajectories of suicidal ideation from middle childhood to early adolescence: Risk and protective factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 1818–1834. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and coding information is available by request from the corresponding author.