Abstract

Childhood trauma has been shown to contribute to low self-concept, potentially affecting trauma survivors’ perception of social evaluations from others. However, there is little evidence for the association between traumatic experience in childhood and adult processing of evaluative verbal cues related to self. Therefore, the present study aimed to address whether and how cognitive and affective responses to self-referential praise and criticism would vary with different forms of childhood trauma. We engaged undergraduates and postgraduates in completing the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and an evaluation task in which participants rated self-related praising and criticizing sentences for pleasantness and truthfulness. These ratings and CTQ scores were subjected to correlation and regression analyses. Positive correlations were found between the pleasantness ratings for criticism and the scores of the CTQ full scale (r90 = .314, p = 0.0011) and two subscales for physical abuse (r90 = .347, p = 0.0004) and physical neglect (r90 = .335, p = 0.0005), indicating that higher scores in the scales were associated with reduced unpleasantness for self-related criticism. The regression analysis further revealed that 14.2% variances of emotional response to criticism could be explained by experience in physical abuse (β = .452, p = .022) and physical neglect (β = .387, p = .027). These findings suggest that childhood exposure to traumatic experience, particularly physical abuse and neglect, leads to attenuated emotional responses to self-referential criticism possibly via the mediation of self-concept.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, Praise, Criticism, Pleasantness, Self-concept

Introduction

According to the report of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1999) childhood abuse or maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, and commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to children or survivors’ health, well-being, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. Childhood trauma is a predictor of severe psychological symptoms which may last a lifetime (Miller et al., 2011). Substantial evidence has suggested the links between childhood trauma and a variety of mental disorders including depression (Negele et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2020), anxiety (Gardner et al., 2019), borderline personality disorder (Ball & Links, 2009; Van der Kolk et al., 1994), and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Çoban & Tan, 2019).

Impaired self-concept has been shown to be an outcome of childhood trauma such that survivors feel worthless, guilty, and shameful with themselves (Gesinde, 2011; Gewirtz-Meydan, 2020; Lopez & Heffer, 1998). Self-concept is considered as a multifaceted cognitive schema that contains traits, values, episodic and semantic memories about the self (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985). Dysfunctional self-concept clarity comes with a higher risk of internalizing problems such as depressive and anxiety symptoms (Van Dijk et al., 2014). Hayward et al. (2020) found that adverse childhood experience including risk families and childhood trauma negatively predicated self-concept clarity, indicating that survivors of early adversity fail to have a well-defined, coherent, and stable sense of self.

Self is comprised of multiple, context-dependent selves that are called self-aspects, in which attributes are attached, representing the qualities exhibited by the person in those contexts (McConnell et al., 2009). Mood change in processing self-referent information reflects the impact of social evaluation on currently activated self-aspects or attributes: greater change in mood is associated with stronger attachment of one attribute with more self-aspects (McConnell et al., 2009). Previous research assessing differences between self-perceived attributes and external feedback has shown that enhanced discrepancies between self-concept and external evaluation trigger agitation-related emotions including fear, restless, and tension while the absence of such discrepancy is associated with “calm” and “secure” (Higgins, 1987).

Taken together, it is possible that affective and cognitive responses to self-referential evaluations from others vary with childhood traumatic experience, which distorts self-concept. Therefore, the present study examined the associations between the pleasantness and truthfulness of personal praise and criticism and different forms of childhood trauma measured by a short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., 2003; Fu et al., 2005).

Methods

Participants

Ninety-two healthy Chinese undergraduates and postgraduates (30 females; age range, 19–33; M ± SD, 22.4 ± 2.234 years) were recruited by local advertisement. The sample size was determined using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007), with effect size of 0.3 and power of 0.9 at α level 0.05. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants had no vision problems or language disabilities and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders according to their self-report. The study was approved by the local ethics committee at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

Prior to the experimental task, participants completed the Chinese version of CTQ (Fu et al., 2005), a 28-item self-report questionnaire assessing traumatic experiences in childhood. Apart from 3 valid items identifying whether or not individuals minimize or deny childhood abuse and neglect (Bernstein et al., 2003), there are 25 clinical items, divided into 5 subscales respectively assessing emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never true; 2 = rarely true; 3 = sometimes true; 4 = often true; 5 = very often true). Therefore, scores on each subscale range from 5 to 25 and the total score ranges from 25 to 125. Higher scores indicate higher levels of childhood trauma. Cronbach’s α was 0.6 for the full scale of the Chinese CTQ and the retest reliability was 0.71 (Fu et al., 2005).

The Evaluation Task

The evaluation task was administered using E-prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The materials used in the task were three types of self-referential descriptives (critical, e.g., "你优柔寡断", "You are indecisive" in English; praising, e.g., "你充满激情", "You are passionate!" in English; neutral, e.g., "你有时独处", "You are sometimes alone."). Each type included 60 sentences of 3 to 7 Chinese characters (M ± SD = 4.8 ± 0.865). The three types of descriptives significantly differed in valence (1 = extremely unpleasant to 7 = extremely pleasant; Mcritical = 2.227 ± 0.255, Mpraising = 5.545 ± 0.274, Mneutral = 3.968 ± 0.561; F2,165 = 1182.941, p < 0.001). While emotional sentences were more arousing than neutral statements (1 = not arousing at all to 7 = extremely arousing; Mcritical = 5.177 ± 0.385, Mpraising = 5.178 ± 0.27, Mneutral = 3.575 ± 0.585; both ps < 0.001) there was no significant difference between positive and negative comments (p = 1).

All sentences were presented randomly and none of them was repeated in the evaluation task. Participants read every sentence as a description of themselves given by an acquaintance and then rated how much they were pleased by the comments and how truly the comments described their attributes using 7-point scales (1 = not pleasant to or true of me at all to 7 = very pleasant to or true of me). In each trial, preceded by a fixation-cross for a random duration between 300 and 700 ms, a sentence was displayed for 1000 ms and then followed by cues for rating pleasantness and truthfulness consecutively. The duration of each rating was time-locked to the key press and the next trial was initiated after participants finished both ratings.

Data Analysis

With IBM SPSS statistics version 22, pleasantness and truthfulness ratings for praise, criticism, and neutral descriptions were analyzed respectively using a one-way repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bonferroni correction was used when pairwise comparisons were applicable. To assess the influence of childhood traumatic experience on the responses to self-referential comments, Pearson correlations (one-tailed) were calculated between comment ratings and questionnaire scores. Given that correlations were calculated between two types of ratings for three categories of descriptive statements and six scores based on the CTQ (five subscores and one total score), a p value of 0.0014 (0.05/36) was considered significant. To measure further the extent to which childhood trauma predict the changes in processing the evaluative verbal cues, a linear regression analysis was conducted between comment ratings and their correlated subscores.

Results

CTQ Scores

The descriptive statistics including the minimums, maximums, means, and standard deviations of the CTQ subscores are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) scores

| CTQ scores | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 5 | 15 | 7.207 | 2.926 |

| Physical abuse | 5 | 15 | 6.044 | 2.291 |

| Sexual abuse | 5 | 18 | 6.185 | 2.882 |

| Emotional neglect | 5 | 20 | 11.685 | 3.978 |

| Physical neglect | 5 | 18 | 9.109 | 3.405 |

| The full scale | 25 | 76 | 40.228 | 12.291 |

Comment Ratings

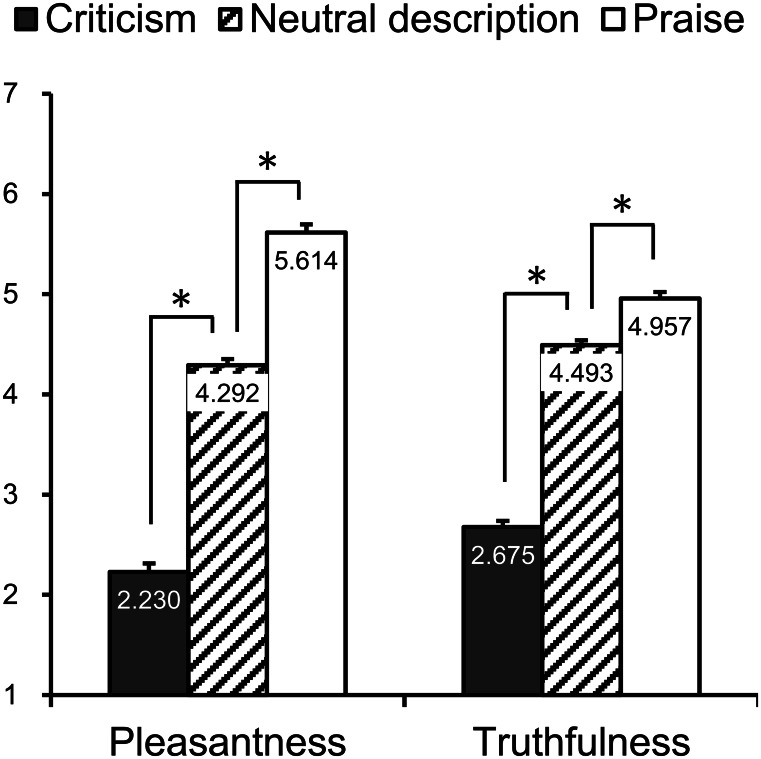

The ANOVA showed significant differences across descriptive types in terms of pleasantness (F2,184 = 513.772, p < 0.001) and truthfulness (F2,184 = 449.693, p < 0.001), respectively. Participants rated praise as the most pleasant and truthful while criticism was perceived as the most unpleasant and untruthful (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pleasantness and truthfulness ratings for criticism, praise, and neutral descriptions. Bars depict M ± SE. *p < .001

Correlations between Comment Ratings and CTQ Scores

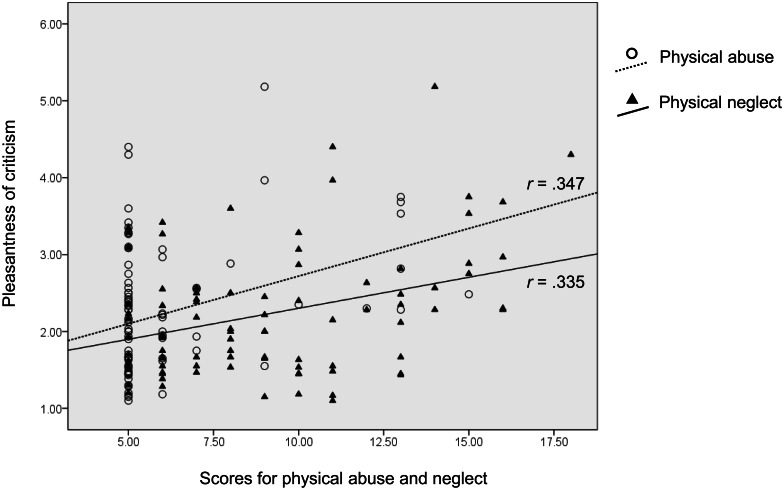

The correlational analyses showed that the pleasantness ratings for criticism were positively correlated with the subscores for physical abuse (r90 = 0.347, p < 0.0014) and physical neglect (r90 = 0.335, p < 0.0014) as well as the total score of the CTQ (r90 = 0.314, p < 0.0014) (Table 2; Fig. 2). No other correlations were significant.

Table 2.

Correlations between ratings and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) scores

| CTQ scores | Pleasantness | Truthfulness | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criticism | Neutral | Praise | Criticism | Neutral | Praise | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Emotional abuse | 0.168 | 0.054 | 0.094 | 0.187 | 0.019 | 0.429 | 0.086 | 0.207 | − 0.071 | 0.251 | 0.012 | 0.455 |

| Physical abuse | 0.347* | 0.0004 | 0.071 | 0.249 | − 0.093 | 0.190 | 0.115 | 0.137 | − 0.126 | 0.116 | 0.034 | 0.375 |

| Sexual abuse | 0.297 | 0.002 | 0.120 | 0.127 | − 0.082 | 0.220 | 0.063 | 0.276 | − 0.055 | 0.303 | 0.002 | 0.494 |

| Emotional neglect | − 0.145 | 0.083 | − 0.051 | 0.314 | − 0.061 | 0.280 | 0.033 | 0.377 | 0.200 | 0.028 | − 0.061 | 0.282 |

| Physical neglect | 0.335* | 0.0005 | 0.219 | 0.018 | 0.047 | 0.327 | 0.036 | 0.367 | − 0.155 | 0.070 | 0.039 | 0.354 |

| The full scale | 0.314* | 0.0011 | 0.141 | 0.090 | 0.001 | 0.496 | 0.056 | 0.298 | − 0.161 | 0.063 | 0.40 | 0.352 |

*significant correlations (one-tailed) with Bonferroni correction, i.e., p < 0.0014 (0.05/36)

Fig. 2.

Correlations between the pleasantness of criticism and scores for physical abuse and neglect

The regression analysis further revealed that 14.2% variances of emotional response to criticism could be explained by experience in physical abuse (β = 0.452, p = 0.022) and physical neglect (β = 0.387, p = 0.027) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) scores correlated with the pleasantness of self-referential criticism

| CTQ scores | β | t | p | F | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse | 0.452 | 2.326 | 0.022 | 6.008 | 0.170 | 0.142 |

| Physical neglect | 0.387 | 2.254 | 0.027 | |||

| The full scale | − 0.371 | − 1.385 | 0.169 |

Discussion

The present study primarily aimed to measure whether and how childhood trauma would influence affective and cognitive judgments of self-referential comments. Basically, praise was perceived as pleasant and more truthfully describing their attributes and criticism, in contrast, unpleasant and less truthful as compared to neutral statements, which is consistent with previous findings (Gao et al., 2018, 2019). More importantly, reduction in the unpleasantness of criticism was associated with more experience in childhood trauma, particularly physical abuse and physical neglect. Physical abuse and neglect were further revealed to predict 14.2% variances of affective response to criticism.

The associations between childhood trauma and the unpleasantness of self-referential criticism indicate the potential mediating role of impaired self-concept, notably self-criticism, the negative evaluation of the self (Blatt, 1974). Previous research (Gilbert & Procter, 2006) has shown that children with neglectful and abused experience tend to be more sensitive to threats and less emotionally regulated and they are more likely to adopt submissive and self-criticizing behaviors for others’ hostile or lack of care towards them. Such abnormality may remain to exist in their adolescence or even adulthood (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002). Sachs-Ericsson et al. (2006) has suggested that physical abuse is a predictor of internalizing symptoms, including self-criticism, and childhood abuse of any type has the potential to influence self-critical tendencies. In the current research, critical comments given by others may consist with the low, critical self-concept of the individuals who had traumatic experience in their childhood and thus elicited less negative emotional responses. On the other hand, self-criticism is deemed as a cognitive strategy favorable for coping with threatening information to avoid negative consequences of a perceived threat (Wytykowska et al., 2021). Kamholz et al. (2006) found that individuals who took self-criticism as a cognitive strategy were able to eliminate the effect of negative information by distracting their attention. In the present study, therefore, self-criticism may function as a survival mechanism to prevent trauma-exposed individuals from social threat represented by critical comments from others. However, it is a conjecture that should be testified in future work.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that childhood trauma, especially physical abuse and physical neglect, attenuates the unpleasantness of self-referential criticism via disturbed self-concept. Given that participants in the present study overall had low exposure to child trauma, it would be interesting to address further the issue in the population suffering severely traumatic experience in childhood. Besides, future research may investigate different neural responses to self-referential criticism in individuals with and without child trauma.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 31800961, the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Chinese Ministry of Education grant 17YJC740023, and the Social Science Planning Project of Sichuan Province grant SC20WY013. National Natural Science Foundation of China, 31800961, Lizhu Luo, Humanities and Social Science Fund of Chinese Ministry of Education, 17YJC740023, Jiehui Hu, Social Science Planning Project of Sichuan Province, SC20WY013, Zhao Gao.

Data Availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Declarations

Ethnical Approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xinying Zhang and Lizhu Luo contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhao Gao, Email: gaozhao@uestc.edu.cn.

Shan Gao, Email: gaoshan@uestc.edu.cn.

References

- Ball JS, Links PS. Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11(1):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ. Levels of object representation in anaclitic andintrojective depression. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1974;29(01):107–157. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1974.11822616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çoban A, Tan O. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Impulsivity, Anxiety, and Depression Symptoms Mediating the Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Symptoms Severity of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2019;57(1):37–43. doi: 10.29399/npa.23654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W. Q., Yao, S. Q., Yu, H. H., Zhao, X. F., LI, R., Li, Y., & Zhang, Y. Q. (2005). Initial Reliability and Validity of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF) Applied in Chinese College Students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 13(01), 40–42. 10.1005/3611(2005)01-0040-03

- Gao, S., Geng, Y., Li, J., Zhou, Y., & Yao, S. (2018). Encoding praise and criticism during social evaluation alters interactive responses in the mentalizing and affective learning networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gao, S., Luo, L., Zhang, W., Lan, Y., Gou, T., & Li, X. (2019). Personality counts more than appearance for men making affective judgments of verbal comments. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M. J., Thomas, H. J., & Erskine, H. E. (2019). The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104082 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gesinde AM. The Impact of Seven Dimensions of Emotional Maltreatment on Self Concept of School Adolescents in Ota, Nigeria. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011;30:2680–2686. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2020). The relationship between child sexual abuse, self-concept and psychopathology: The moderating role of social support and perceived parental quality. Children and Youth Services Review, 113. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104938

- Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2006;13(6):353–379. doi: 10.1002/cpp.507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LE, Vartanian LR, Kwok C, Newby JM. How might childhood adversity predict adult psychological distress? Applying the Identity Disruption Model to understanding depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;265:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review. 1987;94(3):319–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.94.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildyard KL, Wolfe DA. Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26(6–7):679–695. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamholz BW, Hayes AM, Carver CS, Gulliver SB, Perlman CA. Identification and evaluation of cognitive affect-regulation strategies: Development of a self-report measure. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(2):227–262. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9013-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MA, Heffer RW. Self-concept and social competence of university student victims of childhood physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(3):183–195. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Shavelson R. Self-concept: Its multifaceted, hierarchical structure. Educational Psychologist. 1985;20(3):107–123. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2003_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell AR, Rydell RJ, Brown CM. On the experience of self-relevant feedback: How self-concept organization influences affective responses and self-evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(4):695–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological Stress in Childhood and Susceptibility to the Chronic Diseases of Aging: Moving Toward a Model of Behavioral and Biological Mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(6):959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negele A, Kaufhold J, Kallenbach L, Leuzinger-Bohleber M. Childhood Trauma and Its Relation to Chronic Depression in Adulthood. Depression Research and Treatment. 2015;2015:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2015/650804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Verona E, Joiner T, Preacher KJ. Parental verbal abuse and the mediating role of self-criticism in adult internalizing disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93(1–3):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA, Hostetler A, Herron N, Fisler RE. Trauma and the development of borderline personality disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;17(4):715–730. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk MPA, Branje S, Keijsers L, Hawk ST, Hale WW, Meeus W. Self-Concept Clarity Across Adolescence: Longitudinal Associations With Open Communication With Parents and Internalizing Symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(11):1861–1876. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, He X, Chen Y, Lin C. Association between childhood trauma and depression: A moderated mediation analysis among normative Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;276:519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention. Retrieved from WHO Geneva.

- Wytykowska A, Fajkowska M, Domaradzka E. BIS-dependent cognitive strategies mediate the relationship between BIS and positive, negative affect. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;169:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.