Abstract

Aggression and violent behavior are widespread in the world and cause serious threats to public safety. Violent criminal recidivism rates remain very high among certain groups of offenders. In India, the quantum of total violent crimes is continuously increasing from 2009 to 2019. Adverse childhood experiences can affect the development of a child in many ways, leading to highly maladaptive behaviors, such as serious, violent, and chronic (SVC) delinquency. This study was done as a case–control method among recidivist violent offenders and controls to examine the effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on violent criminality. The questionnaire included the World Health Organization Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE- IQ) and standardized measures of Health Risk Behaviors (HRBs). Thirteen categories of adverse childhood experiences of the recidivist violent offenders and controls were measured. Bivariate analysis showed that there was a significant relation (p < 0.001) between ACEs and violent criminality in cases (M = 72.14, SD = 6.80, N = 35) and controls (M = 44.91, SD = 5.39, N = 32). The largest correlation was found between collective violence and household violence (r = 0.813). Bivariate correlation analyses were highly significant between total ACE score and criminality (r (35) = 0.927, p < 0.001). The results reveal that household violence, community violence and collective violence experienced by recidivist violent offenders were nearly double the rate of the control group. Findings emphasize the need for evaluations of ACEs in recidivist offenders for better rehabilitation strategies and also the necessity for preventive efforts at all levels.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40653-021-00434-1.

Keywords: Aggression, Violence, Offenders, Recidivism, Adverse childhood experiences, Health risk behaviors

Introduction

Violence among youth is a global health problem that includes various acts from physical fights, bullying, to more severe physical and sexual assaults to homicide. Aggression and violent behavior are widespread in the world and cause serious threats to public safety (Flannery et al., 2007; Ramsay et al., 2014; Shrivastava et al., 2016). According to the report of the World Health Organization, it is estimated that 0.2 million homicides occur worldwide each year among youths aged between 10–29 years (Organization, 2016). The majority of the perpetrators of the homicide are males in all countries and globally 83% of victims of homicide are youth males (Organization, 2016).

Violent criminal recidivism rates remain very high among certain groups of offenders. Many offenders, even after severe sentences of imprisonment, repeatedly fail to desist from crime and reintegrate into the community as law-abiding citizens. Imprisonment, in itself, is incapable of addressing the offender’s social integration issues. Even when solid prison programs have helped offenders to achieve some progress during detention, that progress is often lost in some offenders. Several studies have demonstrated the relations of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and health risk behaviors (HRBs) in the development of aggression and violence in youths (Farrington, 1994; Harrison et al., 1997).

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Violence

According to the concept of the ‘cycle of violence’, individuals who are maltreated and abused early in life are more likely to engage in violence later in life (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989). It is estimated that during childhood, more than half of the children suffer from at least one traumatic or adverse experience (Copeland et al., 2007; Felitti et al., 1998). Traumatic or adverse experience ranges from different types of abuses, neglect, dysfunctional household environments like parental separation, family violence, household mental illness, household incarceration, household substance abuse, peer group violence, and community violence.

Negative events occurring within the first 18 years of an individual’s life that result in disrupted neurodevelopment leading to social, emotional, and cognitive impairments are called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Felitti et al., 1998). As a result of the early childhood traumatic experiences, the creation of two traits in childhood was hypothesized and these traits were aggression and impulsivity, which were relatively stable throughout life (Farrington, 1994; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). Several studies indicated that when the intensity of ACEs increased there was an early onset of violent crimes among offenders (Baglivio et al., 2015; Howell & Griffiths, 2018).

The Group of juvenile delinquents that commit the highest rate of violent offenses in any given population were known as serious, violent, and chronic (SVC) delinquents (Loeber & Farrington, 1999). It was often found that numerous developmental, psychological and social risk factors heighten the propensity of SVC delinquents in developing chronic violence throughout life (Fox et al., 2015). It has been shown that the possibility of serious, violent, and chronic (SVC) delinquency in juveniles could be predicted by analyzing higher ACE scores (Fox et al., 2015). It was found that ACEs have both direct and indirect effects on criminal recidivism (Wolff & Baglivio, 2017).

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Health Risk Behaviors (HRBs)

Several studies have demonstrated the clustering of health risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol intake, and substance abuse during adolescence (Smith & Bradshaw, 2005). According to the Cumulative Risk Theory, the outcome of the exposure to adverse events by a child will be in a dose-dependent manner (Samerojf et al., 2014). Consistent with this theory, several researchers have found that exposure to multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are predictive of many of the leading causes of health risk behaviors (Garrido et al., 2011).

To cope with their emotions, there is an increased risk of utilizing alcohol by the children who have experienced early childhood trauma. In the children who have experienced childhood adversities an independent association between earlier drinking onset and sexual abuse, physical abuse, household substance abuse, household mental illness, and parental separation were seen (Rothman et al., 2008). Alcohol use disorders (AUD) and problem drinking behaviors were found in children who were abused (Dube et al., 2002; Simpson & Miller, 2002). Problem drinking behavior exists in the form of either dependence or abuse. Children having these two AUDs were likely to have a history of sexual abuse 18 to 21 times more and physical abuse, 6 to 12 times more (Clark et al., 1997). Beyond the effect of growing up with an alcoholic parent, various adverse childhood experiences could be used as a predictive of later-life alcoholism (Anda et al., 2002).

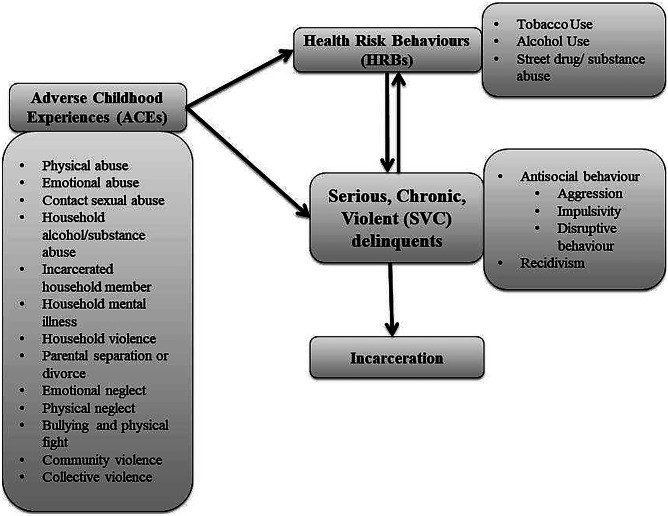

Varieties of other mood-altering substances are used by children in connection to childhood adversity. The use of marijuana, alcohol, and polysubstance abuse was predictive of anxiety, depression, and conduct disorders (Greenbaum et al., 1991; Neighbors et al., 1992). Substance abuse could exacerbate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, or other mental illnesses. The co-occurrence of these two problem behaviors intensifies the effect of both and propels youths towards severe violent and antisocial behaviors (Deykin et al., 1987; Simons et al., 1988). Higher rates of disruptive behavior disorders and depressive disorders were shown by the juveniles with greater levels of alcohol abuse (Rohde et al., 1996). Hence it was more likely that the onset of these behaviors is rooted in a variety of adverse experiences during childhood. Two to four times increase in the early initiation of illicit drug use, drug addiction, and drug use problems were found with each adverse childhood experience (Dube et al., 2003). Intravenous drug and substance use were found in children who were physically and sexually abused (Kerr et al., 2009; Ompad et al., 2005). Exposures to several ACEs were predictive of multiple substance use as the use of illicit drug use and alcohol simultaneously (Harrison et al., 1997). Rebellion towards traditional social values may be manifested by children who express their anger through early life aggression (Brook et al., 1992). This rebellion could take place in the form of drug experimentation and abuse. It was found that conduct problem and aggression is related to chronic substance abuse and dependence which persist in adulthood also (Fergusson et al., 2007). The initiation, abuse, and dependence on mood-altering substances like alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs are associated with higher levels of impulsivity (Gullo & Dawe, 2008; Verdejo-García et al., 2008). Hence it is conceptualized that ACEs and HRBs are involved in developing SVC delinquents as depicted in the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical considerations on the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), health risk behaviors (HRBs) and serious, violent, chronic (SVC) deliquents

If the basic causes of violent crimes can be identified at the grass-root level, corrective measures can be implemented to prevent the increasing rate of recidivism among violent criminals in the country. Further, there are no published research studies from Kerala, India, on the ACEs and HRBs among recidivist violent offenders. Hence, the current investigation is specifically undertaken.

Aim

The current investigation was an endeavor to examine the type and occurrence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and health risk behaviors (HRBs) among the recidivist violent offenders in Kerala and among the individuals who were selected as the control group.

Objectives

Objectives of the study were to: (a) estimate the prevalence of ACEs and HRBs among the recidivist violent offenders in Kerala (b) determine the relations between the ACEs and HRBs (c) understand the relations of violent criminality with ACEs and HRBs.

Hypotheses

Considering the evidence based on the past studies, it was expected that the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Felitti et al., 1998) and health risk behaviors (HRBs) (Strine et al., 2012) among recidivist violent offenders is more than the participants belonging to the control group. Also, criminality was developed by the influence of ACEs and HRBs in the offenders which prompt them repeatedly to commit violent crimes (Wolff & Baglivio, 2017).

Materials and Methods

The universe of the study was offenders from Thrissur, Palakkad, Malappuram, Calicut, and the Kottayam districts of Kerala, India. In the State of Kerala, the followings Acts and Rule deal with the habitual/ recidivist offenders: (a) Habitual Offenders Act, 1960 (b) Kerala Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Act, 2007 (KAAPA Act) (c) Chapter XIV, Sect. 200–205 & 207 of the Kerala Prisons Rules, 1958. Hence the populations of the study were male habitual/ recidivist violent offenders and age-matched controls, termed as case and control respectively. The history sheet of ‘Known Depredator (K.D)’, ‘Habitual Offenders’ and ‘Ex-convicts and Jail release list’ maintained in the police stations were verified in detail by the investigators to know the history of the offenders and crimes committed by them. Simple random sampling was employed to include them in this study. Also, the age at which the first crime was committed was taken into the record. As per the expert opinion, the number of crimes committed under the sections in Chapter XVI (Offences affecting the Human Body) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) was summed up to determine the violent criminality of the cases. Murder, attempt to murder, hurt, assault, wrongful restrain, and rape were considered for calculating violent criminality.

The investigators with the help of the Deputy Superintend of Police (DySP) and Circle Inspectors (CI) of concerned districts made a preliminary list containing details of seventy recidivist violent offenders among that only thirty-five participated in this study. The details of crimes committed by the cases are provided in the supplementary material. On prior intimation by the police officials, the identified offenders were asked to be present in the police stations or called upon to their convenient place or visited at their residence. After noting down the demographic information, a face-to-face structured interview was conducted based on the validated study instruments as detailed below. Individuals of the control group were identified and were met at their residence and interviewed. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. It took a span of 45 to 60 min to complete the interview of each participant.

Case

A male recidivist violent offender (n = 35) in this study referred to an individual, who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: Since the outcome of the aggressive behavior is in the form of offenses against person and property mostly, recidivist violent offenders in this study met three criteria: (a) Above the age of 18 and willing to provide informed written consent (b) Convicted for offenses punishable under Chapter XVI (Offences affecting the Human Body) or Chapter XVII (Offences against property) or both of Indian Penal Code, 1860 (c) Included in the history sheet of ‘Known Depredator (K.D)’/ Habitual offender’/ ‘Ex-convicts and Jail released list’ in the police stations of Kerala State, as per the Acts/ Rules as mentioned.

Exclusion criteria: (a) Individuals with reported psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study (b) Females were excluded from the study. This same criterion was followed in the selection of the control group.

Control

This group (n = 32) included individuals who were the neighbors of the cases.

Inclusion criteria: (a) Individuals of the same age, sex, socio-demographic background (b) No specified antisocial behavior and registered criminal cases.

Study Instruments

The tools used to collect data were the modified and the translated version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE- IQ) (Organization, 2014) and Health Risk Behavior questions (HRBs) (CDC, 2014). Demographic information of the participants was noted, which included age, education, work status over the last 12 months, and civic status. All the questions in the data collection tools were translated to the native language, Malayalam (using the back-translation method). The translation and validation of the study instruments were done with the help of psychology, criminology, language, and statistics experts. On each item of both instruments, the experts expressed 90% or above agreement. The test–retest reliability coefficients for various scales of both study instruments ranged between 0.61 to 0.84.

Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE- IQ)

Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE- IQ) developed by World Health Organization (WHO) (Organization, 2014) was included in the survey instrument. ACE- IQ was developed by WHO to measure adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in all countries (Organization, 2014). This questionnaire was designed for administrating to people aged 18 years older and measures the adverse childhood experiences retrospectively. ACE- IQ contains 9 sections, Demographic information, Marriage, Relationship with Parents/Guardians, Family environment, Peer violence, Witnessing community violence, Exposure to War/ Collective Violence.

Using the original ACE-IQ, 13 categories of childhood experiences can be assessed, which include physical abuse (2 questions); emotional abuse (2 questions); contact sexual abuse (4 questions); alcohol and/or drug abuser in the household (1 question); incarcerated household member (1 question); someone chronically depressed, mentally ill, institutionalized or suicidal (1 question); household member treated violently (3 questions); one or no parents, parental separation or divorce (2 questions); emotional neglect (2 questions); physical neglect (3 questions); bullying (3 questions); community violence (3 questions); collective violence (4 questions) (Organization, 2014). Demographic information includes sex, date of birth, age, ethnic group, education level, employment, civic status, and questions about marriage.

Experts of WHO developed the latest version of ACE- IQ based on the field studies done in seven countries. A study was done using ACE- IQ among adolescents in Vietnam showed good concurrent validity (Tran et al., 2015). As a part of broader health surveys, this questionnaire is being validated in several countries (Almuneef et al., 2014; Bellis et al., 2014).

Depending on the local contexts, the ACE- IQ tool can be used in a modular way. Hence, upon the expert opinion, certain modifications were done in the original ACE- IQ. Questions under the section, marriage in the demographic information were eliminated. The response category, ‘most of the time’ was eliminated from the two response categories, ‘always’ and ‘most of the time’, to the questions belonging to the category of emotional neglect. The response category ‘refused’ was also eliminated from all the questions. Thus, in the modified ACE- IQ, questions had four response categories only. Question regarding the involvement in a physical fight was also included along with the bullying when the total ACE was calculated. Except to the questions belonging to the emotional neglect category, all other questions were positively scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale according to the frequency with which experiences occurred (Bernstein et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 2016), by assigning the values 4, 3, 2 and 1 respectively to ‘many times’, ‘a few times’, ‘once’ and ‘never’. Since the questions belonging to emotional neglect are negative, reverse scoring was done on a 4-point Likert-type scale by assigning the values 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively ‘always’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’ and ‘never’. Values 2 and 1 were assigned respectively to ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in dichotomous scale questions. The total ACE score was calculated by summing up the values of each question in the Likert scale and dichotomous scale in 13 subcategories of ACEs (Zhang et al., 2016). Thus the total ACE score in the modified ACE-IQ ranged from 30 to 110 and was categorized as low (less than or equal to 40), moderate (between 41- 50), medium (between 51- 60), high (between 61- 70) and extreme (greater than or equal to 71).

Health Risk Behaviour Questions (HRBs)

Questions used to define Health Risk Behaviors like tobacco use, alcohol use, and street drugs/ substance abuse were adapted from the male version of the Family Health History Questionnaire of the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study (CDC, 2014).

There were six questions, three were ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions and others were regarding the age of onset of using tobacco, alcohol, and street drugs/ substance abuse. The participants reported whether they started the habit of using tobacco, alcohol, and street drugs/ substance abuse before the age of 18. ACE questionnaires used in the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study had demonstrated good reliability, strong internal consistency, and concurrent validity (Murphy et al., 2014). Values 2 and 1 were assigned respectively to ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in dichotomous scale questions in the HRB questions. The values were summed up to get overall HRBs and these ranges from 3 to 6.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were done with SPSS for Windows version 20.0 and hypotheses were tested at both 0.05 and 0.001 levels of statistical significance. Descriptive statistics, bivariate analysis, and multivariable analysis were carried out for data processing. Initially, descriptive statistics included percentages, mean and standard deviation were employed to understand the demographic information, response of ACE questions; smoking, alcohol, and drug abuse habits of cases, and controls. Subsequently, bivariate analysis was performed using an independent sample t-test for estimating the prevalence of ACEs as mean differences of scores of ACE categories, total ACE, and HRBs in cases and controls. Pearson correlation was carried out to analyse the linear relation within ACE categories in the participants and between ACE categories and violent criminality in cases. In addition, Pearson correlation estimated the relation between total ACE score and HRBs. Multivariable analyses were conducted with linear and multiple regression for predicting violent criminality (Dependent variable) using ACEs or total ACE score as predictors and total ACE score (Predictor) was also used to predict HRBs (Dependent variable).

Results

Demographic Information

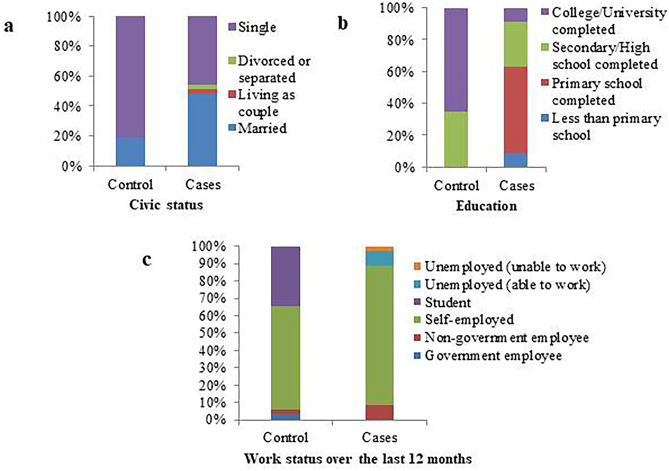

Out of 67 participants, 32 were controls and 35 were cases. The average age of controls was 29.94 (± 3.82) and ranged from 22 to 38. In cases, the average age was 32.17(± 5.15) and ranged from 24 to 43. Nearly half of the participants belonging to the category of the case were either married or living as single, however few were divorced/ separated or living as a couple (Fig. 2a). Regarding education, the controls have completed college/ university education than cases (Fig. 2b). Most of the participants belonging to cases were self-employed and were unemployed even though they were able to work (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Demographic information on civic status (a), education (b) and work status over the last 12 months (c) of participants in percentage

Prevalence of ACEs and HRBs

Table 1 shows the prevalence of ACEs faced by the cases and controls. Cases (M = 72.14, SD = 6.80, N = 35) experienced significantly more ACEs (t (65) = –17.30, p < 0.001) than controls (M = 44.91, SD = 5.39, N = 32). For five ACE categories (Household violence, physical neglect, bullying and physical fight, community violence, and collective violence), the cases that experienced this trauma were nearly double the rate of the controls. The ACEs, incarcerated household members (M = 1.00, SD = 00, N = 32) and household mental illness (M = 1.00, SD = 00, N = 32) were not experienced by the controls.

Table 1.

Prevalence of ACEs and HRBs in Controls and Cases

| ACE categories | Controls | Cases | t value | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | |||||

| ACE 1 | Physical Abuse | 4.28 (0.63) | 6.34 (0.99) | –9.98 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 2 | Emotional Abuse | 4.13 (0.94) | 5.80 (1.59) | –5.19 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 3 | Contact Sexual Abuse | 4.56 (1.37) | 5.80 (2.04) | –2.89 | 65 | 0.005* |

| ACE 4 | Household alcohol/substance abuse | 1.19 (0.40) | 1.71 (0.46) | –5.01 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 5 | Incarcerated household member | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.37 (0.49) | –4.28 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 6 | Household mental illness | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.20 (0.41) | –2.79 | 65 | 0.006* |

| ACE 7 | Household violence | 4.81 (1.55) | 8.97 (1.25) | –12.13 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 8 | Parental separation or divorce | 2.22 (0.42) | 2.86 (0.73) | –4.32 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 9 | Emotional neglect | 4.97 (1.12) | 6.51 (0.82) | –6.49 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 10 | Physical neglect | 3.75 (1.24) | 6.89 (2.10) | –7.35 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 11 | Bullying and physical fight | 3.88 (1.64) | 6.94 (0.99) | –9.33 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 12 | Community violence | 4.81 (1.12) | 7.57 (1.27) | –9.41 | 65 | 0.000** |

| ACE 13 | Collective Violence | 4.31 (0.59) | 10.17 (1.82) | –17.35 | 65 | 0.000** |

| Total ACE Score | 44.91 (5.39) | 72.14 (6.80) | –18.06 | 65 | 0.000** | |

| Types of HRBs | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.31 (0.47) | 1.97 (0.17) | –7.754 | 65 | 0.000** | |

| Alcohol use | 1.44 (0.50) | 1.94 (0.24) | –5.332 | 65 | 0.000** | |

| Street drugs/ Substance Abuse | 1.28 (0.46) | 1.77 (0.43) | –4.545 | 65 | 0.000** | |

| Overall HRB | 4.03 (1.31) | 5.69 (0.63) | –6.687 | 65 | 0.000** | |

Controls (N = 32), Cases (N = 35), Values are expressed as Mean ± SD. Asterisks (*) and (**) denotes significance at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 respectively against controls

In cases category 97.10% of the participants reported that they were using tobacco, however, only 31.20% of the controls was having this habit. Alcohol and street drug/ substance abuses were 94.30% and 77.10% respectively in the participants belonging to cases. Whereas in the control group, alcohol and street drug/ substance abuses were 43.80% and 28.10% respectively. Similarly, significant differences in the mean score of HRBs for tobacco use (t (65) = –7.754, p < 0.001), alcohol use (t (65) = –5.332, p < 0.001), substance abuse (t (65) = –4.545, p < 0.001) and also overall HRBs (t(65) = –6.687, p < 0.001) were observed in cases and controls (Table 1).

Out of the three HRBs, tobacco risk behavior seemed to have more prevalent in cases (M = 1.97, SD = 0.17, N = 35) than controls (M = 1.31, SD = 0.47, N = 32). In controls, all the three habits of HRBs started at the age of 16 or after. Whereas, the onset of HRB habits in cases were found to begin from age 12 and 14 and the number HRBs was increased depending upon the intensity of ACE exposure in them.

Relations between ACEs and HRBs

The bivariate correlations showing co-occurrence of ACEs between each item were estimated and presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations showing co-occurrence of ACEs

| ACE Categories | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE | ACE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| ACE 1:Physical Abuse | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ACE 2:Emotional Abuse | 0.591** | 1 | |||||||||||

| ACE 3:Contact Sexual Abuse | 0.320** | 0.2 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ACE 4:Householdalcohol/ substance abuse | 0.473** | 0.407** | 0.09 | 1 | |||||||||

| ACE 5:Incarcerated household member | 0.466** | 0.269* | 0.212 | 0.302* | 1 | ||||||||

| ACE 6:Household mental illness | 0.350** | 0.505** | 0.254* | 0.270* | 0.079 | 1 | |||||||

| ACE 7:Household violence | 0.752** | 0.503** | 0.265* | 0.570** | 0.472** | 0.237 | 1 | ||||||

| ACE 8:Parental separation or divorce | 0.396** | 0.229 | 0.389** | 0.394** | 0.325** | 0.299* | 0.412** | 1 | |||||

| ACE 9:Emotional neglect | 0.479** | 0.376** | 0.199 | 0.460** | 0.304* | 0.260* | 0.601** | 0.292* | 1 | ||||

| ACE 10:Physical neglect | 0.547** | 0.536** | 0.345** | 0.450** | 0.275* | 0.489** | 0.627** | 0.396** | 0.609** | 1 | |||

| ACE 11:Bullying & physical fight | 0.604** | 0.444** | 0.315** | 0.491** | 0.499** | 0.257* | 0.654** | 0.375** | 0.564** | 0.573** | 1 | ||

| ACE 12:Community violence | 0.633** | 0.341** | 0.186 | 0.398** | 0.472** | 0.194 | 0.723** | 0.385** | 0.520** | 0.500** | 0.735** | 1 | |

| ACE 13:Collective Violence | 0.744** | 0.539** | 0.358** | 0.598** | 0.493** | 0.323** | 0.813** | 0.515** | 0.592** | 0.635** | 0.795** | 0.748** | 1 |

N = 67, Asterisks (*) and (**) denotes significant correlations at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 respectively

Most of the ACE categories were positively correlated to one another and the correlation coefficients ranged from r = 0.079 to r = 0.813. Among the ACE items, the largest correlation was found between the presence of collective violence and household violence (r = 0.813). Whereas, a very weak correlation was found (r = 0.079) between household mental illness and incarcerated household members.

The correlation between HRBs and the total ACE score of the participants is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationship between HRBs and total ACE score among participants

| HRBs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Tobacco use | 1 | ||||

| 2. Alcohol use | 0.834** | 1 | |||

| 3. Street drugs/ Substance Abuse | 0.716** | 0.638** | 1 | ||

| 4. Total ACE Score | 0.724** | 0.575** | 0.559** | 1 | |

| 5. Overall HRB | 0.937** | 0.905** | 0.873** | 0.684** | 1 |

N = 67, HRBs = Health risk behaviors, ACE = Adverse childhood experience, Asterisks (**) denotes significance at p < 0.001

Significant relations were found between total ACE scores and tobacco use (r (67) = 0.724, p < 0.001), alcohol use (r (67) = 0.575, p < 0.001), substance abuse (r (67) = 0.559, p < 0.001) and all correlations were higher than 0.50. Also, overall HRB and total ACE score were found to be significantly correlated (r (67) = 0.684, p < 0.001).

As shown in Table [4], highly significant regression equation was found between total ACE scores and tobacco use (F (1, 65) = 71.56, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.524), alcohol use (F (1, 65) = 32.12, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.331), substance abuse (F (1, 65) = 29.53, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.312) and overall HRB (F (1, 65) = 57.18, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.468).

Table 4.

ACEs predicting HRBs

| HRBs | Un-standardized Coefficients | R2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constant

(B) (SE) |

Variable

(B) (SE) |

|||

| Tobacco use | 0.292 (0.166) | 0.023 (0.003) | 0.524 | 0.000** |

| Alcohol use | 0.657 (0.190) | 0.018 (0.003) | 0.331 | 0.000** |

| Street drugs/Substance Abuse | 0.431 (0.210) | 0.019 (0.003) | 0.312 | 0.000** |

| Overall HRB | 1.381 (0.479) | 0.059 (0.008) | 0.468 | 0.000** |

Un-standardized Coefficients (B), Standard error (SE), Coefficient of determination (R2) and significance levels (p) for total ACE score predicting HRBs; N = 67, ACE = Adverse childhood experience, HRBs = Health risk behaviors, Asterisks (**) denotes significance at p < 0.001

Relations of Violent Criminality with ACEs and HRBs

Significant association was found between age of onset of crime and the ACE exposure in cases (χ2 (7, N = 35) = 20.8, p < 0.05). The correlation between ACEs and violent criminality is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bivariate correlations of ACEs and criminality in Cases

| r | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criminality | 1 | |

| ACE 1 | Physical Abuse | 0.418* |

| ACE 2 | Emotional Abuse | 0.468** |

| ACE 3 | Contact Sexual Abuse | 0.495** |

| ACE 4 | Household alcohol/substance abuse | 0.313* |

| ACE 5 | Incarcerated household member | 0.370* |

| ACE 6 | Household mental illness | 0.355* |

| ACE 7 | Household violence | 0.393* |

| ACE 8 | Parental separation or divorce | 0.415* |

| ACE 9 | Emotional neglect | 0.059 |

| ACE 10 | Physical neglect | 0.375* |

| ACE 11 | Bullying & physical fight | 0.586** |

| ACE 12 | Community violence | 0.222 |

| ACE 13 | Collective Violence | 0.641** |

| ACE Total | 0.927** | |

Cases (N = 35), Asterisks (*) and (**) denotes significant correlations at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 respectively, r = correlation coefficient

Emotional neglect and community violence did not show any significant correlation with violent criminality, whereas all the other ACE categories showed a significant correlation with violent criminality (r > 0.30). Highly significant correlation was found between total ACE score and criminality (r (35) = 0.927, p < 0.001).

As shown in Table 6, scores of each ACE category, total ACE, and collective ACEs can be successfully used as predictors for violent criminality. Except for household alcohol/ substance abuse and emotional neglect, a marginally significant regression equation was found between categories of ACEs and violent criminality as the dependent variable. Using total ACE score as the predictor variable, 86.0% of the variability in the violent criminality as the dependent variable is accounted for by the regression (F (1, 33) = 202.71, p < 0.001) and the predictor variability of each of the 13 categories. Also, in multiple regression analysis collective ACEs significantly predicted violent criminality (F (13, 21) = 34.693, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.956).

Table 6.

Categories of ACEs predicting violent criminality

| ACE variables | Un-standardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients (β) |

R2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constant (B) (SE) |

Variable (B) (SE) |

|||||

| ACE 1 | Physical Abuse | 4.270(6.111) | 2.52 (0.952) | 0.418 | 0.175 | 0.012* |

| ACE 2 | Emotional Abuse | 9.957(3.501) | 1.771 (5.583) | 0.468 | 0.219 | 0.005* |

| ACE 3 | Contact Sexual Abuse | 11.766(2.734) | 1.459 (0.445) | 0.495 | 0.245 | 0.002* |

| ACE 4 | Household alcohol/ substance abuse | 13.200(3.844) | 4.1 (2.168) | 0.313 | 0.098 | 0.067 |

| ACE 5 | Incarcerated household member | 14.014(2.883) | 4.531 (1.983) | 0.37 | 0.137 | 0.029* |

| ACE 6 | Household mental illness | 13.929(3.049) | 5.25 (2.411) | 0.355 | 0.126 | 0.037* |

| ACE 7 | Household violence | 3.254(6.980) | 1.892 (0.771) | 0.393 | 0.154 | 0.020* |

| ACE 8 | Parental separation or divorce | 10.519(3.826) | 3.398 (1.298) | 0.415 | 0.172 | 0.013* |

| ACE 9 | Emotional neglect | 17.397(8.382) | 0.435 (1.277) | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.736 |

| ACE 10 | Physical neglect | 12.819(3.324) | 1.076 (0.462) | 0.375 | 0.141 | 0.026* |

| ACE 11 | Bullying and physical fight | -4.274(5.957) | 3.525 (0.850) | 0.586 | 0.343 | 0.000** |

| ACE 12 | Community violence | 12.261(6.179) | 1.052 (0.805) | 0.222 | 0.049 | 0.2 |

| ACE 13 | Collective Violence | -1.256(4.552) | 2.112 (0.441) | 0.641 | 0.41 | 0.000** |

| Total ACE Score | -38.939(4.174) | 0.820 (0.058) | 0.927 | 0.86 | 0.000** | |

Un-standardized Coefficients (B), Standard error (SE), Standardized coefficients (β), Coefficient of determination (R2) and significance levels (p) for individual ACE categories predicting violent criminality of Cases (N = 35), ACE = Adverse childhood experience; Asterisks (*) and (**) denotes significant correlations at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 respectively

However, the present study failed to identify significant relations between violent criminality and tobacco use (r (35) = 0.209, p = 0.114), alcohol use (r (35) = 0.030, p = 0.431), substance abuse (r (35) = 0.090, p = 0.304) and overall HRB (r (35) = 0.128, p = 0.232).

Discussion

Among both groups, the most frequent ACE reported by the participants in this study was physical abuse and none of the participants reported that they were never subjected to physical abuse during childhood. This was similar to the findings of Felitti and colleagues (Felitti et al., 1998) and in contrast to the published study done in Kerala among youth (Damodaran & Paul, 2017).

As reported by the participants, the frequency of exposure to sexual abuse was least among them and similar to the prevalence already reported in past investigations done in Kerala among adolescents and youths (Damodaran & Paul, 2017; Nair & Devika, 2014). The response rates were found to be less for the questions regarding sexual abuse in this study also due to the inherent nature of this social problem (Damodaran & Paul, 2017; Gorey & Leslie, 1997). Fourteen correlations were higher than 0.60. This result indicated that the 13 categories of ACE were correlated with each other indicating the co-occurrence and interrelation of ACEs in the Indian population (Baglivio et al., 2015; Damodaran & Paul, 2017). In the land marking study conducted by Felitti and colleagues (Felitti et al., 1998) it was reported that 67% of the participants experienced one or more ACEs together.

As the mean individual score of 13 categories of ACEs and total ACE score differed significantly among the cases and controls in this study, the impact of ACEs on cases was specifically analyzed. This helped to understand the impact that ACEs have on serious, violent, and chronic criminal behavior. Results indicated that when the intensity of ACEs increased, there was an early onset of violent crimes among offenders. This finding was similar to those reported by more than 20 longitudinal studies (Baglivio et al., 2015; Howell, 2003; Howell & Griffiths, 2018; Krohn et al., 2001). On examining the official crime records of the offenders with a highest ACE score, it was understood that the frequency, serious offenses, and gang involvement were more among these offenders (DeLisi & Piquero, 2011; Howell, 2003; Howell & Griffiths, 2018).

Among the recidivist violent offenders in this study, the number of incidents, longevity, or the severities of the exposure to individual ACEs was significantly higher. Similar findings were reported by past research (Barrett et al., 2014; Bellis et al., 2013). The major adverse experiences to which the offenders exposed were witnessing household, community, and collective violence; physical neglect; bullying, and involvement in physical fights, which were double the rate when compared to the control population, which indicated the “double whammy” or trigger compounding effect on violent behavior in recidivist violent offenders (Herrenkohl et al., 2008).

The mean score of the ACE category, bullying, and physical fight, was significantly high in offenders when compared to the controls. This showed that the offenders were subjected to frequent bullying and involved in physical fights when they were children. This might have resulted in peer adjustment problems, associating with deviant peers, and peer conflict resolution difficulties (Chapple et al., 2005; Margolin & Gordis, 2004).

Even though the offenders in this study were convicted several times and presumably corrected, the rate of violent criminal recidivism was high in this group. This showed the similar effect of ACEs in offenders as reported in several other investigations (Baglivio & Jackowski, 2013; Barrett et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2011; Cicchetti & Manly, 2001; Yun et al., 2011). Household incarceration and mental illness were reported only by the offender population in this study and the same adversity during childhood could have contributed to developing the violent criminal recidivism in them (Thomas et al., 1995; Wildeman, 2009).

The significant correlation of total ACE score and violent criminality among offenders indicated the developmental perspective of pathological aggression (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984; Toth & Cicchetti, 2013). Predictions of Moffit’s developmental taxonomy are supported by the findings of this study, as the offenders subjected to the most significant developmental risk factors and multiple adverse childhood experiences, became serious, violent, and chronic offenders (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). It could be assumed that the recidivist violent offenders in this study belong to Moffit’s LCP offending group. Also, the criminal trajectory of these offenders showed that these offenders belong to the SVC offenders who may continue to commit violence and serious crimes all through the life-course similar to the LCP offenders (Fox et al., 2015). The results of this study show that ACE scores can significantly predict future violence in offenders as reported in several other studies (Baglivio et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2015).

In this study, the prevalence of HRBs was significantly more in offenders when compared with the control population. Several other studies also reported that HRBs in offenders elevated the chances of criminal recidivism and violent behavior (Cottle et al., 2001; Dowden & Brown, 2002; Loeber & Farrington, 1998). Approximately one-third of the violent crimes, like homicide, sexual assault, domestic violence, etc., in the U.S are linked to alcohol use and similar results were obtained in this study also with a high prevalence of alcohol use among recidivist violent offenders (Horvath & LeBoutillier, 2014). The relation between HRBs and violent criminality was not found in this study. This result is against the finding of many other types of research where a significant relation was found between substance abuse and criminal recidivism behavior (Cottle et al., 2001; Dowden & Brown, 2002).

Most of the participants reported that during the first 18 years of life they had started the health risk behaviors like smoking, consumption of alcohol, and usage of street drugs. In the whole population, smoking was common, followed by alcohol use and substance abuse. Early onsets of HRBs were seen in both groups. In the participants, when the frequency of ACE exposure increased the number of HRBs also increased. Also, significant positive correlations were found between the total ACE score and score of each category of HRBs and total HRB. These findings were supported by several previous types of research which demonstrated a graded relation between ACEs and HRBs (Dube et al., 2003; Harrison et al., 1997; Rothman et al., 2008). As reported in this study, ACEs also could be used as predictors for HRBs (Anda et al., 2002; Harrison et al., 1997).

Policy Implications

From the results of this study, several practical interventions can be drawn. The results can be used to support the development of specific programs to prevent the paths toward SVC delinquency in juveniles who lacks proper attention. Prevention of the onset of childhood adverse experiences should be the primary goal of the intervention based on the result of this study. Since adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were a salient and significant predictor of both health risk behaviors (HRBs) and criminality in this study, the ability to prevent ACEs from occurring should be of the utmost importance. Theoretically, by preventing the variety of ACEs early in the lives of children, they should be able to develop in more adaptive and positive ways, which equips them to avoid more problematic, maladaptive, and violent behavioral outcomes.

Prevention of ACEs

Developing programs to prevent children from ACEs is principally endorsed by the findings of this study. Cost-effective practices like early life interventions which provide improved prenatal assistance and parental care have improved the family life of those at risk of trauma and subsequent adverse outcomes (Cohen et al., 2010; Zigler & Hall, 1989). Parental and family training programs have found a robust effect on the lives of the children, showing a reduction in antisocial behavior and subsequent delinquency over time (Piquero et al., 2008).

Visiting the home of high-risk families were designed to prevent ACEs and family conflicts, which enhanced the caregiving abilities of parents at risk, educated them on the effects of child maltreatment and taught positive problem-solving behaviors (Zigler & Hall, 1989). It was found that the parent management training (PMT) and functional family therapy (FFT) improved family dynamics, reduced family dysfunction and enhanced the overall development of the child (White, 1999). Hence, these findings suggest the effectiveness of a more comprehensive program in preventing the ACEs which will preclude children from a path that can lead to antisocial behavior and criminality.

Preventions programs on sexual abuse were best implemented at the school level which included role-playing, lectures, behavioral training, multimedia, doll, or puppet shows to teach children about what constitutes sexual abuse. At school, sexual abuse prevention programs were found to be effective and the effect increased with more sessions (Davis & Gidycz, 2000). In the case of incarcerated parents who re-enter the family household after incarceration, several support programs like behavioral or attitude training were introduced and found effective in preventing multiple ACEs (Hairston & Lockett, 1985).

Prevention of HRBs

Beyond the above-mentioned programs to reduce ACEs, interventions are also recommended to address HRBs in those who experienced ACEs. Also, SVC delinquency was directly related to substance abuse and hence their prevention and decrease would reduce the development of serious violent behaviors (Perez et al., 2018). “Drug Abuse Resistance Education” (D.A.R.E.) program implemented in the U.S was found to be largely ineffective (Perez, 2016a, b). Science-based substance abuse prevention programs for at-risk high school youth, “Project Towards No Drug Abuse” (Project TND) were able to be successful in preventing the onset of substance abuse (Gorman, 2003). This program was based on education about the consequences of drug abuse, motivation enhancement, and coping skills management (Sussman et al., 2012). Hence such scientifically evaluated interventions should be done among the children who have faced ACEs and are at risk of substance abuse. Such scientific interventions may be included in similar programs like ‘Clean Campus Safe Campus’ implemented in the schools of Kerala as a joint initiative of Home, Education, and Health Departments of Government of Kerala (KeralaPolice, 2018).

Prevention of Violent Criminal Recidivism

Based on the results of this study when a youth comes in contact with the juvenile justice system, coordinated primary interventions for assessing their ACEs and the mediating factors related to their behavior and personality should be done and considered for determining their risk for serious, violent, and chronic delinquency later in life. “Positive Achievement Change Tool” (PACT), a program developed by the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, screens the youth’s overall risk for recidivism (Perez, 2016a, b). Based on the PACT assessment and recommendations, these juveniles are directed for community-based correctional services or intensive attention and treatment (Vincent et al., 2012). Another program outside of the juvenile justice system, specifically for children who face ACEs, known as “Childhaven”, is an ecological-model therapeutic child caring intervention also found to be effective (Moore et al., 1998). “The Incredible Years Parent, Teacher, and Child” training series which targets children who display early indications of conduct problems have also been shown to reduce the chances of violent offending later in adolescence (Piquero et al., 2008). To reduce the SVC delinquency in youths whom this behavior has already manifested, a tertiary prevention program known as multisystemic therapy (MST) was implemented and found as a strong tool in the reduction and cessation of SVC delinquency (Borduin et al., 1995; Curtis et al., 2004; Henggeler et al., 1992). This intervention was individualized and highly flexible, addresses intrapersonal (cognitive) and systemic factors (family, peer, school) factors that were known to be related to adolescent antisocial behavior (Borduin et al., 1995). Also, the ACEs could be used as mitigating factors in the sentencing of youthful and non-youthful offenders (Trapassi, 2017).

Strengths and limitations

Several types of research have discussed independently the harmful effects of childhood traumas and HRBs on criminality and the relation between ACEs and HRBs in different populations. By including thirteen categories of ACEs in the ACE score and three HRBs of recidivist violent offenders, the present study was unique to its breath. Also, the prevalence of the ACEs was measured in this study, which most of the studies have not yet demonstrated (Perez, 2016a, b). Moreover, this is the first study conducted in the Indian population that demonstrated the interaction of ACEs in the development of violent criminality in recidivist offenders.

It should be noted that for research purposes, recruitment of prison inmates or prison-released offenders was extremely problematic due to the ethical limitations and significant legal hurdles (Gostin, 2007). Another issue might be regarding the retrospective assessment of ACEs and HRBs of the subjects using questionnaires. Many large scale studies in these areas have relayed upon self-complete questionnaires, but in this study face-to-face structured interviews were conducted for each participant by the trained investigator to know their ACEs and HRBs, a method having evidence of good validity that reduced data collection bias in a small sample size (Jaffee et al., 2004; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Newbury et al., 2018). The activities of several genes controlling the neurotransmitters in humans are altered by environmental factors like ACEs especially during the early stages of life and such factors also could develop aggression leading to violence (Prasad et al., 2020).

Conclusions

The results of this study could be used to support the development of specific programs to prevent the paths toward SVC delinquency in juveniles who lacks proper attention. Prevention of the onset of childhood adverse experiences should be the primary goal of the intervention based on the result of this study. Since adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were more among recidivist violent offenders in this study, the ability to prevent ACEs from occurring should be of the utmost importance. Also, the ACEs of the violent recidivist offenders may be assessed and considered while developing rehabilitation strategies for them. Theoretically, by preventing the variety of ACEs early in the lives of children, they should be able to develop in more adaptive and positive ways, which equips them to avoid more problematic, maladaptive, and violent behavioral outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the Prison and Police Departments, Government of Kerala; Prof. C. Jayan, Former Head of the Department of Psychology, University of Calicut. Greatly acknowledges Mrs. Priyatha Siva Prasad for providing statistical assistance and the participants who came forward for this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the University Grants Commission’s Junior Research Fellowship (JRF), Government of India.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Calicut University Human Ethical Committee, University of Calicut, Malappuram, Kerala, India (Ethical clearance certificate number: 003/CUEC/CR/2013–12-CU dated 25.04.2014).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Not required by the ethics committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Siva Prasad M.S., Email: drsivaprasadms@uoc.ac.in.

Jayesh K. Joseph., Email: criminologistkepa@gmail.com

Y. Shibu Vardhanan, Email: svardhanann@gmail.com.

References

- Almuneef M, Qayad M, Aleissa M, Albuhairan F. Adverse childhood experiences, chronic diseases, and risky health behaviors in Saudi Arabian adults: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(11):1787–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(8):1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Jackowski K. Examining the validity of a juvenile offending risk assessment instrument across gender and race/ethnicity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2013;11(1):26–43. doi: 10.1177/1541204012440107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Jackowski K, Greenwald MA, Howell JC. Serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders: A statewide analysis of prevalence and prediction of subsequent recidivism using risk and protective factors. Criminology & Public Policy. 2014;13(1):83–116. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, Piquero AR, Epps N. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and juvenile offending trajectories in a juvenile offender sample. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2015;43(3):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DE, Katsiyannis A, Zhang D, Zhang D. Delinquency and recidivism: A multicohort, matched-control study of the role of early adverse experiences, mental health problems, and disabilities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2014;22(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/1063426612470514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Jones L, Baban A, Kachaeva M, Ulukol B. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: Surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014;92:641–655. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.129247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, Harrison D. Adverse childhood experiences: Retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of Public Health. 2013;36(1):81–91. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borduin CM, Mann BJ, Cone LT, Henggeler SW, Fucci BR, Blaske DM, Williams RA. Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders: Long-term prevention of criminality and violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(4):569. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman MM, Finch S. Childhood aggression, adolescent delinquency, and drug use: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1992;153(4):369–383. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1992.10753733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2014). Violence prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html.

- Chapple CL, Tyler K, Bersani BE. Child neglect and adolescent violence: Examining the effects of self-control and peer rejection. Faculty Publications; 2005. p. 67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-Y, Propp J, Delara E, Corvo K. Child neglect and its association with subsequent juvenile drug and alcohol offense. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2011;28(4):273. doi: 10.1007/s10560-011-0232-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Manly JT. Operationalizing child maltreatment: Developmental processes and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(4):755–757. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401004011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Lesnick L, Hegedus AM. Traumas and other adverse life events in adolescents with alcohol abuse and dependence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(12):1744–1751. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Piquero AR, Jennings WG. Estimating the costs of bad outcomes for at-risk youth and the benefits of early childhood interventions to reduce them. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2010;21(4):391–434. doi: 10.1177/0887403409352896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottle CC, Lee RJ, Heilbrun K. The prediction of criminal recidivism in juveniles: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2001;28(3):367–394. doi: 10.1177/0093854801028003005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis NM, Ronan KR, Borduin CM. Multisystemic treatment: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(3):411. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran DK, Paul VK. Patterning/Clustering of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): The Indian Scenario. Psychological Studies. 2017;62(1):75–84. doi: 10.1007/s12646-017-0392-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MK, Gidycz CA. Child sexual abuse prevention programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29(2):257–265. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi M, Piquero AR. New frontiers in criminal careers research, 2000–2011: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011;39(4):289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deykin EY, Levy JC, Wells V. Adolescent depression, alcohol and drug abuse. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77(2):178–182. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.77.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowden C, Brown SL. The role of substance abuse factors in predicting recidivism: A meta-analysis. Psychology, Crime and Law. 2002;8(3):243–264. doi: 10.1080/10683160208401818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(5):713–725. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, D. P. (1994). Childhood, adolescent, and adult features of violent males Aggressive behavior (pp. 215–240): Springer.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, D. J., Vazsonyi, A. T., & Waldman, I. D. (2007). The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression: Cambridge University Press.

- Fox BH, Perez N, Cass E, Baglivio MT, Epps N. Trauma changes everything: Examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and serious, violent and chronic juvenile offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;46:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido EF, Culhane SE, Petrenko CL, Taussig HN. Psychosocial consequences of caregiver transitions for maltreated youth entering foster care: The moderating impact of community violence exposure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(3):382. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Leslie DR. The prevalence of child sexual abuse: Integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(4):391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman DM. Alcohol & drug abuse: The best of practices, the worst of practices: The making of science-based primary prevention programs. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(8):1087–1089. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO. Biomedical research involving prisoners: Ethical values and legal regulation. JAMA. 2007;297(7):737–740. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime: Stanford University Press.

- Greenbaum PE, Prange ME, Friedman RM, Silver SE. Substance abuse prevalence and comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders among adolescents with severe emotional disturbances. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):575–583. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo MJ, Dawe S. Impulsivity and adolescent substance use: Rashly dismissed as “all-bad”? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(8):1507–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF, Lockett P. Parents in Prison: A child abuse and neglect prevention strategy. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1985;9(4):471–477. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ. Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(6):529–539. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: An effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(6):953. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2008;9(2):84–99. doi: 10.1177/1524838008314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, M. A., & LeBoutillier, N. (2014). Alcohol use and crime. The encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice, 1–7.

- Howell, J. C. (2003). Preventing and reducing juvenile delinquency: A comprehensive framework: Sage.

- Howell, J. C., & Griffiths, E. (2018). Gangs in America's communities: Sage Publications.

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Taylor A. Physical maltreatment victim to antisocial child: Evidence of an environmentally mediated process. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):44. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KeralaPolice. (2018). Clean Campus Safe Campus. Available at http://safecampus.keralapolice.gov.in/about_clean_campus_safe_campus.

- Kerr T, Stoltz J-A, Marshall BD, Lai C, Strathdee SA, Wood E. Childhood trauma and injection drug use among high-risk youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(3):300–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, M., Thornberry, T., Rivera, C., & Le Blanc, M. (2001). Later delinquency careers of very young offenders. I R. Loeber, & DP Farrington (Red.). Child delinquents, (s. 67–94): Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions: Sage Publications.

- Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (1999). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions: Sage.

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. Children's exposure to violence in the family and community. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(4):152–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(2):355–375. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E, Armsden G, Gogerty PL. A twelve-year follow-up study of maltreated and at-risk children who received early therapeutic child care. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3(1):3–16. doi: 10.1177/1077559598003001001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Steele M, Dube SR, Bate J, Bonuck K, Meissner P, Steele H. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and adult attachment interview (AAI): Implications for parent child relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(2):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair AB, Devika J. Self-reported sexual abuse among a group of adolescents attending life skills education workshops in Kerala. Academic Medical Journal of India. 2014;2(1):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors B, Kempton T, Forehand R. Co-occurence of substance abuse with conduct, anxiety, and depression disorders in juvenile delinquents. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17(4):379–386. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90043-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury JB, Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Danese A, Baldwin JR, Fisher HL. Measuring childhood maltreatment to predict early-adult psychopathology: Comparison of prospective informant-reports and retrospective self-reports. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018;96:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Ikeda RM, Shah N, Fuller CM, Bailey S, Morse E, Vlahov D. Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(4):703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ).

- Organization, W. H. (2016). Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children.

- Perez, N. M. (2016a). The path to violent behavior. The harmful aftermath of childhood trauma.

- Perez, N. M. (2016b). The path to violent behavior: the harmful aftermath of childhood trauma: University of South Florida.

- Perez NM, Jennings WG, Baglivio MT. A path to serious, violent, chronic delinquency: The harmful aftermath of adverse childhood experiences. Crime & Delinquency. 2018;64(1):3–25. doi: 10.1177/0011128716684806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A, Farrington D, Welsh B, Tremblay R, Jennings W. Effects of Early Family/Parent Traning Programs on Antisocial Behavior & Delinquency. A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2008;2008:11. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad MS, Vardhanan YS, Prabha SS, Joseph JK, Aneesh EM. MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism in male recidivist violent offenders in the Indian population. Archiwum Medycyny Sądowej i Kryminologii/archives of Forensic Medicine and Criminology. 2020;70(4):1–9. doi: 10.5114/amsik.2020.104863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay S, Bartley A, Rodger A. Determinants of assault-related violence in the community: Potential for public health interventions in hospitals. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2014;31(12):986–989. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(1):101–109. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Edwards EM, Heeren T, Hingson RW. Adverse childhood experiences predict earlier age of drinking onset: Results from a representative US sample of current or former drinkers. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e298–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samerojf, A. J., Bartko, W. T., Baldwin, A., Baldwin, C., & Seifer, R. (2014). Family and social influences on the development of child competence Families, risk, and competence (pp. 171–196): Routledge.

- Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. An urgent global need to reduce the prevalence of youth violence in heterogeneous settings. International Journal of Advanced Medical and Health Research. 2016;3(1):36. doi: 10.4103/2350-0298.184674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Conger RD, Whitbeck LB. A multistage social learning model of the influences of family and peers upon adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Drug Issues. 1988;18(3):293–315. doi: 10.1177/002204268801800301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Miller WR. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(1):27–77. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. J., & Bradshaw, P. (2005). Gang membership and teenage offending: University of Edinburgh, Centre for Law and Society Edinburgh.

- Sroufe, L. A., & Rutter, M. (1984). The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child development, 17–29. [PubMed]

- Strine TW, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Prehn AW, Rasmussen S, Wagenfeld M, Croft JB. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, psychological distress, and adult alcohol problems. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36(3):408–423. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Sun P, Rohrbach LA, Spruijt-Metz D. One-year outcomes of a drug abuse prevention program for older teens and emerging adults: Evaluating a motivational interviewing booster component. Health Psychology. 2012;31(4):476. doi: 10.1037/a0025756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AM, Forehand R, Neighbors B. Change in maternal depressive mood: Unique contributions to adolescent functioning over time. Adolescence. 1995;30(117):43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment. 2013;18(3):135–139. doi: 10.1177/1077559513500380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Q. A., Dunne, M. P., Vo, T. V., & Luu, N. H. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and the health of university students in eight provinces of Vietnam. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(8_suppl), 26S-32S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Trapassi, J. R. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Role as Mitigators for Youthful and Non-Youthful Offenders in Capital Sentencing Cases.

- Verdejo-García A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(4):777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GM, Guy LS, Gershenson BG, McCabe P. Does risk assessment make a difference? Results of implementing the SAVRY in juvenile probation. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2012;30(4):384–405. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. (1999). R. Loeber & D. Farrington (Eds.) Serious & Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Journal of Youth Studies, 2(3), 371–374.

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59(3):355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C. Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography. 2009;46(2):265–280. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff KT, Baglivio MT. Adverse childhood experiences, negative emotionality, and pathways to juvenile recidivism. Crime & Delinquency. 2017;63(12):1495–1521. doi: 10.1177/0011128715627469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yun I, Ball JD, Lim H. Disentangling the relationship between child maltreatment and violent delinquency: Using a nationally representative sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(1):88–110. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ming Q, Wang X, Yao S. The interactive effect of the MAOA-VNTR genotype and childhood abuse on aggressive behaviors in Chinese male adolescents. Psychiatric Genetics. 2016;26(3):117–123. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigler, E., & Hall, N. W. (1989). Physical child abuse in America: Past, present, and future. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect, 38–75.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.