Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns potentially severely impact adolescents’ mental well-being. This research aims to study students’ subjective well-being during the covid-19 pandemic in Iran and investigate the role of loneliness, resilience, and parental involvement. For this study, 629 students (female = 345) were recruited by purposive sampling. Students were assessed on the Student’s Subjective Well-Being, Loneliness Scale, Resilience Scale, and Parental Involvement. The results confirm our hypothesis that the relationship between parental involvement and students’ subjective well-being is mediated by loneliness. Furthermore, the results indicated a partial mediation of resilience in the relationship between parental involvement and students’ subjective well-being. This study theoretically contributes to a better understanding of the factors determining the impact of traumatic events such as a pandemic on adolescents’ mental health. The implications of this study indicate interventions that can be carried out to minimize the negative psychological consequences of the pandemic.

Keywords: Subjective well-being, Loneliness, Resilience, Parental involvement, Covid-pandemic

Mental well-being is essential for society to function correctly (Tennant et al., 2007). In a state of well-being, individuals can cope with the pressures of life, be productive, and contribute to society (Surya et al., 2017). Recent studies show that conditions related to the Covid pandemic (e.g., social distancing, isolation, insecurity, and anxiety) exacerbate stress-related symptoms and affect mental health (Duan & Zhu, 2020; Satici et al., 2020). For example, individuals reported higher levels of depression, anxiety (Roy et al., 2020), post-traumatic stress disorder (Liu et al., 2020), frustration, isolation (Giallonardo et al., 2020), anger, sadness and depression (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2020).

Physical distancing and social isolation influence children and adolescents, where social bonding is a critical component of psychosocial development. The necessary policy responses to COVID-19 may impact mental health outcomes, including suicidal behavior (Gunnell et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown the psychological and physical health impacts of social isolation during quarantine (Brooks et al., 2020), and more generally, social isolation is associated with poor mental health and physical outcomes (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). Additionally, adolescents are likely to have reduced physical activity. Previous studies have shown the impacts of sedentary behavior on health outcomes in young people (Lobstein et al., 2015) and interrelated factors of diet, overweight and obesity, and well-being (Costigan et al., 2013; Fatima et al., 2015). In addition, In the case of diseases, the perception of threat is influenced by several factors, including the probability of vulnerability or contagion and the severity of the changes produced by the condition in the event of infection (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2020). The perceived threat has been linked to higher levels of worry (Berenbaum et al., 2007).

Therefore, people who perceive a higher threat are at greater risk of negative consequences on their subjective mental well-being. In the case of Covid, the perception of threat is linked to individuals’ perceptions of how COVID-19 can produce an unwanted outcome that can have negative consequences on their lives. In addition, individuals have been shown to experience fear due to the perceived threat of Covid, which can adversely affect their mental health (Garfin et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020).

Feeling of Loneliness among Students

Social distancing and school closures may increase loneliness among children and adolescents whose usual disease containment measures reduce social contact. When all physical and social connection is cut off during confinement, feelings of loneliness may intensify in adolescents, and negatively related to happy feelings (Neto, 2001), which has been linked to depressive symptoms, especially when experiencing these stressful feelings for a long time (Bitan et al., 2020).

Loneliness is the painful emotional experience of a mismatch between actual and desired social contact (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). Although social isolation does not necessarily equate to loneliness, early indications of COVID-19 indicate that more than thirty percent of adolescents report high levels of loneliness (Barzilay et al., 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020). Studies show a well-established link between loneliness and mental health (Wang et al., 2017).

Resilience as a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Well-being

Resilience is a dynamic process of positive coping in response to a traumatic/adverse event. This process is influenced by the interaction of risk and protective factors. Internal protective factors can include confidence, independence, and positive self-talk, enabling individuals to function resiliently in the face of adversity. Resilience does not protect people from adversity, but protective factors can help individuals respond resiliently to adversity. (Masten, 2015; Ungar & Hadfield, 2019).

People with such characteristics are likely to generate more positive self-talk that boosts their self-image and promotes independence. With such a positive mindset, resilience helps people develop a positive view of themselves, prompting them to seek out and participate in experiences that maximize their psychological well-being (Snodgrass & Thompson, 1997). It has been found that there is a positive relationship between resilience, high self-esteem (Benetti & Kambouropoulos, 2006), and high self-confidence (Klohnen et al., 1996). Such self-esteem drives resilient individuals to persist and endure in times of struggle (Smokowski et al., 1999).

Although many findings have indicated that resilience can protect individuals from adversity, fewer studies have focused on identifying the underlying mechanism. Among these were Tugade et al. (2004), who indicated that trait resilience was associated with experiencing positive effects. In other words, resilient individuals are suggested to use positive emotions to bounce back from adversity. Although the mediation of positive emotionality has been supported (Tugade et al., 2004), how positive emotions are cultivated has remained unanswered. According to the cognitive model of depression (Beck, 1987), how people perceive and interpret adversity influences how they feel and relate to the world. It has been found that depressed individuals view themselves, their world, and their future negatively (Beck, 1987).

Parental Involvement, Engagement, and Students’ Well-being

Parental involvement in education could be defined as the interaction of parents with schools and their children to benefit their children’s educational success (Hill et al., 2004). Researchers have conceptualized parental involvement as a multifaceted concept encompassing school participation, home participation, and school socialization (Epstein & Sanders, 2002; Fan & Chen, 2001; Hill & Chao, 2009).

School involvement includes parent-teacher communication, attending school events, and volunteering at school. Participation at home includes setting up a structure for homework and leisure time (e.g., having a fixed time or place for homework, visiting museums) and monitoring schoolwork and some progress. Several studies have identified parental involvement in education as a necessary means of facilitating the positive development of young people (Epstein & Sanders, 2002; Hill & Chao, 2009; Hill et al., 2004). In addition to academic success, parental involvement in education can serve as a critical context for adolescent mental health development (Roeser & Eccles, 2000). Several studies have underlined the importance of parental behavior in the courses of depression in adolescence (Duchesne et al., 2009; Pomerantz et al., 2006).

Research has also shown that improved emotional behaviors can positively impact success in school and, ultimately, in life (Masten et al., 2005). However, most existing research on parental involvement in education has focused on educational outcomes, with less emphasis on its potential impacts on emotional functioning in adolescents. Since adolescent mental health is integral to their academic competence, a deeper understanding of the relationship between parental involvement, academic achievement, and adolescent mental health is needed (Hill & Chao, 2009).

Present Study

As many researchers point out, the psychological consequences of the restrictions experienced will be visible for many years. Since the pandemic affects people worldwide, it is possible to compare people's feelings, beliefs, and behaviors from different cultural backgrounds. Iran was one of the first countries to be hit by the virus and struggled with high death tolls and social consequences, such as school closings. Pupils in both rural and urban areas use a mobile application called “Shabake Ejtemaee Baraye Daneshamoozan” (i.e., social media for students) or “Shad,” literally translated as “happy,” to access the educational materials and cyber-classrooms. Although the Ministry of Education has done its best to address the educational issues, many aspects of student's lives, including mental health, have been overlooked. This study hypothesized that resilience and loneliness predict student subjective well-being. In addition, it is also hypothesized that parental involvement mediates the relationship between loneliness and resilience with student subjective well-being.

Methods

Participants

The study participants were 629 school students studying in seventh, eighth, or ninth grade from various schools in Iran in 2020. These participants were selected from eight schools (four girls' and four boys' schools) from Isfahan, Arak, and Tehran. A purposive sampling technique was utilized for data collection. The participants chosen for the study were living with their parents and attending online school for at least the past six months during data collection. All participants have been studying in the current school for more than one year. All participants had access to internet facilities and gadgets to attend online schooling. The sample population consisted of 284 male (45.2%) and 345 female (54.8%) students from various state and private schools in Iran. A summary of the participants’ demographic information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants (n = 629)

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 284 | 45.2 |

| Female | 345 | 54.8 |

| Grade | ||

| 7th | 264 | 42 |

| 8th | 239 | 38 |

| 9th | 126 | 20 |

| Age | ||

| 12 | 39 | 6.2 |

| 13 | 188 | 29.9 |

| 14 | 226 | 35.9 |

| 15 | 147 | 23.4 |

| 16 | 29 | 4.6 |

| Number of Sibling | ||

| None | 80 | 12.7 |

| One | 350 | 55.6 |

| Two | 152 | 24.2 |

| Three or more | 47 | 7.5 |

| Access to school counsellor | ||

| Yes | 570 | 90.6 |

| No | 59 | 9.4 |

| Like to Continue online classes? | ||

| Yes | 202 | 32.1 |

| No | 427 | 67.9 |

Measures

Students’ Subjective well-being (Renshaw et al., 2015) was developed to measure the school-specific subjective well-being of young people. This is a 16-item self-assessment tool made up of four 4-item subscales: Joy of learning ( e.g., I feel happy while studying and learning), School connectivity (e.g., I think people at this school care about me), educational goals (e.g., I think what I do in school is essential) and academic competence (e.g., I am a successful student) The items of the SSWQ are assessed using a 4-point Likert-type scale (i.e., 1 = hardly ever, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = almost always). Previous research has shown that the original English version of the SSWQ has strong internal consistency and convergent validity with various general findings for young people (Renshaw et al., 2015). The reliability of the Persian version of the scale was reported as α = 0.87 (Akbaribalootbangan et al., 2016). The reliability in the current study was α = 0.86.

Loneliness Measure (Hughes et al., 2004) is a short three-item scale measuring loneliness in extensive surveys. The items were: “How often do you feel like you lack company?” (Relational connection); “How often do you feel left out?” (Collective connection); and “How often do you feel isolated from others?” (General isolation). The students were asked to answer the questions in the questionnaires. Previous studies found the three-item scale reliable (i.e., α = 0.80) (Matthews-Ewald & Zullig, 2013). The scale’s reliability was reported as α = 0.91 in a study conducted by Zarei et al. (2016). In the current study, the reliability was found to be α = 0.89.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003). This is a 25-item questionnaire developed as a clinical measure to assess the positive effects of treatment for stress reactions, anxiety, and depression. We chose this scale because it includes elements that illustrate the challenge, commitment, control, and other aspects of resilience, such as goal setting, patience, faith, tolerance to adverse effects, and humor. Subjects indicated their opinion on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ("not true at all") to 4 ("true most of the time"). Sample items included "I can deal with unpleasant or painful feelings such as sadness, fear and anger" and "Under pressure, I stay focused and think clearly." The internal consistency of the scale for Iranian samples has been reported to be high (Khoshouei, 2009). Likewise, the present study had a strong alpha (α = 0.89).

Parental Involvement Questionnaire (Voydanoff & Donnelly, 1999) measures how involved a parent or parents are in their children’s lives. Items ask whether parents have done things for their adolescents, such as attending school events or talking to teachers for three months, six months, or years. They can select the appropriate period based on your evaluation plan. The respondent needed to select each item on the parent’s list during the selected period. The α for the scale was found to be 0.71.

Procedure

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. The study participants were recruited by approaching authorities of schools and educational centers. Initially, the school authorities were briefed about the study; they were asked to share this information with potential participants. The research group approached ten schools. Parents were contacted in a parent-teacher meeting. We explained participants’ rights of voluntary participation, confidentiality, and withdrawal. Participants were guaranteed the confidentiality of their responses and their identity. In addition, they were assured that their identity would be made available only to the research teacher for research purposes only. After explaining the purpose of the study, parents and children were asked to complete an informed consent form. Due to the spread of Covid-19, we used an online-based survey system on an Iranian website, www.porsline.ir. The link to the questionnaires was sent to the participants. About 1000 participants viewed the link, and 629 final questionnaires were collected. Hence the response rate was 62.9%. Some of the responses were removed as they had missing data and were partially filled. There are several reasons for the response rate. Some participants opened the link, read the instructions, and decided to answer these questionnaires some other time.

On the other hand, others failed to push the final submit button, thinking an answer to the final question was enough, without actually sending their response to us. We also found that some participants' internet connection was disconnected while answering the questionnaire. Consequently, these participants had to answer the first few questions for the second time and were regarded as new participants by the data collection system. All online forms are stored in an online web-based cloud system provided by the University of Isfahan.

Data Analysis

The data collected was cleaned, numbered, and then entered into Excel. The data were analyzed using SPSS and AMOS software. The data set was tested for normality, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between the variables. Further, structural equation modeling and mediation analysis was conducted. The model fit was checked and assessed using specific model fit indices. Chi-square/degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF), the goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), tucker levis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation was used to evaluate the model fit. A good model fit needs CMIN/ df value is less than 3, GFI, CFI, and TLI values would be greater than 0.90 or 0.95, and RMSEA value is less than 0.80 or 0.50. The bootstrapping procedure was used to assess the mediating effects of the variables (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The data was presented with the support of appropriate tables and figures. The information was stored in a password-protected file on an external hard disk.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

The descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, reliability estimates (Cronbach alpha), and bivariate correlation for all the variables, are shown in Table 2. Relationship between parental involvement, loneliness, resilience, and student subjective well-being. The correlation results showed that parental involvement is negatively correlated with loneliness (r = -0.493, p < 0.01), positively correlated with resilience (r = 0.270, p < 0.01) and student subjective well-being (r = 0.504, p < 0.01). The variables loneliness and student subjective well-being (r =—0.478, p < 0.01) are negatively correlated. Also, resilience and student subjective well-being are positively correlated (r = 0.444, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Mean, Standard deviation, Correlation and reliability values

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Correlation | Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 1.Parental Involvement | 3.90 | 0.865 | –- | 0.847 (8 items) | |||

| 2. Loneliness | 1.71 | 0.583 | 0.493** | –- | 0.839 (3 items) | ||

| 3. Resilience | 3.79 | 0.967 | 0.270** | 0.203** | –- | 0.555 (2 items) | |

| 4. Student Subjective Well-being | 3.36 | 0.586 | 0.504** | 0.478** | 0.444** | –- | 0.925 (16 items) |

** p < 0.01

The Mediation Model for Parental Involvement, Loneliness, and Student Subjective Well-being

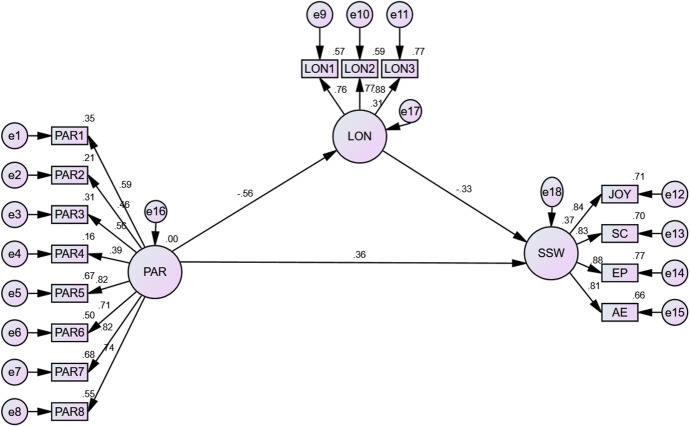

The mediation model with the independent variable as parental involvement, mediating variable as loneliness, and dependent variable as student subjective well-being was analyzed using structural equation modeling. All the path coefficients in the model were significant. The direct effects of the variables are shown in Fig. 1. Model fit was checked using absolute model fit indices, including chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and goodness of fit index (GFI). The incremental fit indices included comparative fit index (CFI) and tucker lewis index (TLI) values. Chi-square statistics was significant (chi-square = 209.773, p < 0.05), so chi-square / degrees of freedom (CMIN/ df) were checked. The value CMIN/ df was 2.411 indicating the acceptable fit of the model. The root mean square error of approximation value (RMSEA = 0.047), goodness of fit index (GFI = 0.941), comparative fit index (CFI = 0.974) and tucker lewis index (TLI = 0.968) indicated the model is a good fit.

Fig. 1.

The mediation model for parental involvement, loneliness and student subjective well-being (Model 1). Note. PAR- Parental involvement; LON- Loneliness; SSW- Student subjective well-being; JOY- Joy of learning; SC- School connectedness; EP – Educational purpose; AE – Academic efficacy

As presented in Fig. 1, the direct effect of parental involvement on student subjective well-being is significant (β = . 36, p < 0.001). Parental involvement and loneliness are negatively connected and significant (β = -0.56, p < 0.001). Loneliness is negatively linked to students' subjective well-being, and it is significant (β = -0.33, p < 0.001).

The mediation analysis results indicated a partial mediation of loneliness on the relationship between parental involvement and student subjective well-being. Five thousand bootstrap samples with a 95% confidence interval were used for the mediation analysis. The specific indirect effect of parental involvement on student subjective well-being through the mediation of loneliness (β = 0.184, 95% CI [ 0.105, 0.209]) was significant since the upper and lower limit of the confidence interval does not contain zero (presented in Table 3). The results indicated that the relationship between parental involvement and student subjective well-being is partially mediated by loneliness.

Table 3.

Indirect effects test using bootstrapping 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the final mediation models

| Paths between the variables | Boot strapping | 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SEB | Lower | Upper | |

| Parental involvement – Loneliness – Student subjective well-being (Model 1) | .184 | .048 | .105 | .259 |

| Parental involvement—Resilience – Student subjective well-being (Model 2) | .169 | .040 | .105 | .264 |

Empirical 95% confidence interval does not overlap with 0. β, Standardized coefficients; SEB, bootstrapped standard errors; CI, confidence interval

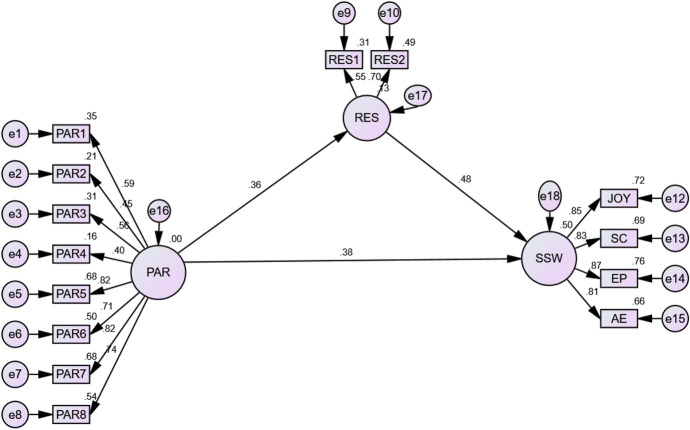

The Mediation Model for Parental Involvement, Resilience, and Student Subjective Well-being

The mediation model with the independent variable as parental involvement, mediating variable as resilience, and dependent variable as student subjective well-being was analyzed using structural equation modeling. All the path coefficients in the model were significant. The direct effects of the variables are shown in Fig. 1. In the model, Chi-square statistics was significant (chi-square = 197.548, p < 0.05), so chi-square / degrees of freedom (CMIN/ df) were checked. The value CMIN/ df was 2.670 indicating the acceptable fit of the model. The root means the square error of approximation value (RMSEA = 0.052) indicates the model is an acceptable fit. Goodness of fit index (GFI = 0.957), comparative fit index (CFI = 0.968) and tucker lewis index (TLI = 0.961) indicated the model is a good fit.

The direct effect of the variables is presented in Fig. 2. Parental involvement and student subjective well-being are positively linked and significant (β = 0.38, p < 0.01). Parental involvement and resilience are positively connected and significant (β = 0.36, p < 0.01). Resilience and student subjective well-being are also positively linked and significant ( β = 0.48).

Fig. 2.

The mediation model for parental involvement, resilience and student subjective well-being (Model 2). Note. PAR- Parental involvement, RES- Resilience, SSW- Student subjective well-being, JOY- Joy of learning, SC- School connectedness, EP – Educational purpose, AE- Academic efficacy

The mediation analysis results indicated a partial mediation of resilience in the relationship between parental involvement and student subjective well-being. Five thousand bootstrap samples with a 95% confidence interval were used for the mediation analysis. The specific indirect effect of parental involvement on student subjective well-being through the mediation of resilience (β = 0.169, 95% CI [0.105, 0.264]) was significant (presented in Table 3). The results indicated a partial mediation of resilience in the relationship between parental involvement and student subjective well-being.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine students’ subjective well-being during the covid-19 pandemic in Iran and investigate the role of loneliness, resilience, and parental involvement. The correlation analysis indicates that resilience positively relates to student well-being, whereas loneliness is negatively related. This shows that more resilience in children is associated with higher well-being, and those who feel lonely tend to have a lower well-being score. The relationship between resilience levels and well-being has been documented in several studies (Noble & McGrath, 2012; O’Brien et al., 2020).

One possible explanation for the relationship between subjective well-being and loneliness levels is that well-being represents the presence of intra- and interpersonal resources that enhance adaptation to a more lonely existence. Likewise, situational characteristics, such as having few social resources, and superficial or non-existent interpersonal relationships, are believed to be a predisposing factor for the development of loneliness (Perlman et al., 1984).

Thus, higher scores on loneliness show the lack of social resources and should be associated with lower scores related to available social resources such as resilience. Social resources are considered essential in mental health, as researchers emphasize that healthy adaptation is a process (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000; Windle, 2011; Windle et al., 2011). More precisely, it can be defined as a transactional process where resilience develops through the dynamic interaction of individuals with their environment. It can also be described as the individual’s ability to navigate between available resources (Ungar, 2005).

Parental involvement was positively correlated with subject well-being, indicating that students with more parental involvement in their lives scored higher on well-being. This result agrees with previous studies (Fan & Williams, 2010; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). In a related study, Wang and Sheikh-Khalil (2014) reported that parents who indicated the importance and value of education and discussed future goals with their children motivated them to be behaviorally and emotionally engaged in their schoolwork. Consequently, this behavioral and emotional engagement in school led to better results. Additionally, providing an appropriate structure and an intellectually supportive family environment was positively associated with success through behavioral engagement.

In addition, The individual models of parental involvement with loneliness and resilience as mediators and subjective well-being as the outcome variable have indicated a partial mediating effect. The first model showed that student well-being was influenced by parental involvement directly and through the mediating role of loneliness, with loneliness being significantly negatively related to parental involvement and subjective well-being. Similarly, the second model showed that resilience partially mediated the relationship between parental involvement and student well-being, wherein resilience was significantly positively correlated with both variables.

The relationship between parental involvement and students’ psychological well-being is based on two factors. The first is that the family environment is the initial social arena in which adolescents remain more systematically under the influence and supervision of their parents. Later in their lives, adolescents begin to seek an alternate reality, separating from their parents and integrating with their peers during adolescence (Bossard & Boll, 1960). Adolescents begin to construct their self-concept by observing the reactions directed toward them by vital individuals in their lives (Gibson & Jefferson, 2006). The personal experiences that arise from the parent-adolescent relationship are the initial source that sets off the cycle of how adolescents will self-assess and interact with others. In other words, the type of relationship they experience with their parents prefigures their attitudes towards themselves and the quality of the relationships they will have with their peers (Wilkinson, 2004).

To control the spread of Covid-19, the Iranian Ministry of Education required principals and teachers to turn to an online teaching plan. Although the online learning method promises to maintain course delivery and minimize disruption to learning routines, it poses even more challenges for students trying to survive the uncertainties and fears of pervasive disease and adapt to the new learning method. They were also at greater risk due to limited social interactions. In all COVID-19-affected countries, including Iran, government officials and medical experts sent the message “to stay at home." This social distancing, universally accepted as an effective measure for the COVID-19 pandemic, may be very helpful in reducing the prevalence of coronavirus. However, social isolation, i.e., the objective lack of interaction with others (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017), can contribute to adverse outcomes such as loneliness. In the meantime, psychological variables should be sought to reduce this negative experience of loneliness. The present study showed that resilience and parental intervention could mediate the relationship between Subjective Well-being and Loneliness in Iran.

Like any other study, this research may suffer from limitations. This study employs a self-report data collection method, which might impose some limitations on the study. In addition, this study did not use random sampling; although the sample size was relatively large, the generalization of the result needs to be done with caution. In addition, we contacted parents during parent-teacher meetings, which means that parents already have a basis for involvement. This might impose some limitations on the study. Another limitation of this study was that all participants were students who lived with both parents, and single-parent students were omitted. Therefore, we recommend that researchers investigate this variable in future studies as well.

In this study, we investigated Iranian public schools. In these schools, parents participate in student activities to a similar extent. Nevertheless, some private schools may have more opportunities for parental involvement, and we suggest that future researchers explore other forms of schools. Socio-demographic variables can also impact the study findings, including the student's age, gender, family status, etc.

Although this study may have some limitations, it is, to our knowledge, the first study to indicate that when there is parental involvement in a student's life, especially during a crisis, such as the pandemic of Covid-19, it is less likely for them to experience loneliness and more likely to be resilient. Additionally, current research findings have examined the role of both individual-level systems (i.e., resilience) and social systems (i.e., parental involvement) in increasing adolescents' well-being. Combining these findings leads to a better understanding of the lived experiences of adolescents during the pandemic. Echoing international policy reports, our findings indicate the urgency of generating strategies that help parents contribute to their children's better educational experiences. finally, the present study is the only study carried out in one of the Middle Eastern countries – i.e., Iran, and the repetition of this study in other countries can offer the possibility of comparing the results.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Faramarz Asanjarani, Email: f.asanjarani@edu.ui.ac.ir.

Aneesh Kumar, Email: aneesh.kumar@christuniversity.in.

Simindokht Kalani, Email: sd.kalani@edu.ui.ac.ir.

References

- Akbaribalootbangan A, Najafi M, Babaee J. The factorial structure of subjective well-being questionnaire in adolescents of Qom city. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2016;14(1):45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, DiDomenico GE, Brown LA, White LK, Gur RC, Gur RE. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety, and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Translational Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1987;1:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benetti C, Kambouropoulos N. Affect-regulated indirect effects of trait anxiety and trait resilience on self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41(2):341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Thompson RJ, Bredemeier K. Perceived threat: Exploring its association with worry and its hypothesized antecedents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(10):2473–2482. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan DT, Grossman-Giron A, Bloch Y, Mayer Y, Shiffman N, Mendlovic S. Fear of COVID-19 scale: Psychometric characteristics, reliability, and validity in the Israeli population. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113100. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossard JHS, Boll ES. The sociology of child development. Harper & Row; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: A rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depression and anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR. The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(4):382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, Ratelle CF, Poitras S-C, Drouin E. Early adolescent attachment to parents, emotional problems, and teacher-academic worries about the middle school transition. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(5):743–766. doi: 10.1177/0272431608325502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J. L., & Sanders, M. G. (2002). Family, school, and community partnerships. In (pp. 407–437): Citeseer.

- Fan X, Chen M. Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review. 2001;13(1):1–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1009048817385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Williams CM. The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology. 2010;30(1):53–74. doi: 10.1080/01443410903353302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima Y, Doi S, Mamun A. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2015;16(2):137–149. doi: 10.1111/obr.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfin DR, Silver RC, Holman EA. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology. 2020;39(5):355. doi: 10.1037/hea0000875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giallonardo V, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Albert U, Carmassi C, Carrà G, Cirulli F, Dell’Osso B, Nanni MG. The impact of quarantine and physical distancing following COVID-19 on mental health: Study protocol of a multicentric Italian population trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:533. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DM, Jefferson RN. The effect of perceived parental involvement and the use of growth-fostering relationships on self-concept in adolescents participating in gear up. Family Therapy. 2006;33(1):29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guessoum, S. B., Lachal, J., Radjack, R., Carretier, E., Minassian, S., Benoit, L., & Moro, M. R. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, Hawton K, John A, Kapur N, Khan M, O’Connor RC, Pirkis J, Caine ED. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Chao RK. Families, schools, and the adolescent: Connecting research, policy, and practice. Teachers College Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Castellino DR, Lansford JE, Nowlin P, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1491–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshouei MS. Psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) using Iranian students. International Journal of Testing. 2009;9(1):60–66. doi: 10.1080/15305050902733471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klohnen EC, Vandewater EA, Young A. Negotiating the middle years: Ego-resiliency and successful midlife adjustment in women. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11(3):431. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, Caan W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290:113172. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, James WPT, Wang Y, McPherson K. Child and adolescent obesity: Part of a bigger picture. The Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2510–2520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61746-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(4):857–885. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, Boelcke-Stennes K, Tellegen A. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(5):733. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews-Ewald MR, Zullig KJ. Evaluating the performance of a short loneliness scale among college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2013;54(1):105–109. doi: 10.1353/csd.2013.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neto F. Personality predictors of happiness. Psychological Reports. 2001;88(3):817–824. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2012). Well-being and resilience in young people and the role of positive relationships. In Positive relationships (pp. 17–33). Springer.

- O’Brien N, Lawlor M, Chambers F, Breslin G, O’Brien W. Levels of well-being, resilience, and physical activity amongst Irish pre-service teachers: A baseline study. Irish Educational Studies. 2020;39(3):389–406. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2019.1697948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes MdC, MoleroJurado MdM, MartosMartínez Á, Gázquez Linares JJ. Threat of COVID-19 and emotional state during quarantine: Positive and negative affect as mediators in a cross-sectional study of the Spanish population. PloS one. 2020;15(6):e0235305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, D., Peplau, L. A., & Goldston, S. (1984). Loneliness research: A survey of empirical findings. Preventing the harmful consequences of severe and persistent loneliness, 13–46.

- Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal Relationships. 1981;3:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Ng FF-Y, Wang Q. Mothers’ mastery-oriented involvement in children’s homework: Implications for the well-being of children with negative perceptions of competence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98(1):99. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw TL, Long AC, Cook CR. Assessing adolescents’ positive psychological functioning at school: Development and validation of the Student Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. School Psychology Quarterly. 2015;30(4):534. doi: 10.1037/spq0000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser, R. W., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Schooling and mental health. In Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 135–156). Springer.

- Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, Sharma N, Verma SK, Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici, B., Saricali, M., Satici, S. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Intolerance of uncertainty and mental well-being: serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smokowski PR, Reynolds AJ, Bezruczko N. Resilience and protective factors in adolescence: An autobiographical perspective from disadvantaged youth. Journal of School Psychology. 1999;37(4):425–448. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(99)00028-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JGE, Thompson RL. The self across psychology: Self-recognition, self-awareness, and the self concept. New York Academy of sciences; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Surya M, Jaff D, Stilwell B, Schubert J. The importance of mental well-being for health professionals during complex emergencies: It is time we take it seriously. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(2):188–196. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, Parkinson J, Secker J, Stewart-Brown S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Feldman Barrett L. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(6):1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M, Hadfield K. The differential impact of environment and resilience on youth outcomes. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. 2019;51(2):135. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. (2005). Pathways to resilience among children in child welfare, corrections, mental health and educational settings: Navigation and negotiation. Child and youth care forum.

- Usher K, Durkin J, Bhullar N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2020;29(3):315. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff, P., & Donnelly, B. W. (1999). Multiple roles and psychological distress: The intersection of the paid worker, spouse, and parent roles with the role of the adult child. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 725–738.

- Wang MT, Sheikh-Khalil S. Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development. 2014;85(2):610–625. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D, Forsyth R, Nebo C, Mann F, Johnson S. Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2017;52(12):1451–1461. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RB. The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(6):479–493. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2011;21(2):152–169. doi: 10.1017/S0959259810000420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei S, Memari AH, Moshayedi P, Shayestehfar M. Validity and reliability of the UCLA loneliness scale version 3 in Farsi. Educational Gerontology. 2016;42(1):49–57. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2015.1065688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]