Abstract

Objective

This study aims to compare a conventional medical treatment model with a telehealth platform for Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) outpatient care during the global novel coronavirus pandemic.

Methods

In this study, we described the process of converting our MFM clinic from a conventional medical treatment model to a telemedicine platform. We compared clinical productivity between the two models. Outcomes were analysed using standard statistical tests.

Results

We suffered three symptomatic COVID-19 infections among our clinical providers and staff prior to the conversion, compared with none after the conversion. We had a significant decrease in patient visits following the conversion (53.35 visits per day versus 40.3 visits per day, p < 0.0001). However, our average daily patient visits per full-time equivalent (FTE) were only marginally reduced (11.1 visit per FTE versus 7.6 visits per FTE, p < 0.0001), resulting in a relative decrease in adjusted work relative value units (6987 versus 5440). There was an increase in more basic follow-up ultrasound procedures, complexity (current procedural technology [CPT] code 76816 (10.7% versus 19.5%, relative risk [RR] 1.81, 95% CI 1.60–2.05, p < 0.0001)) over comprehensive follow-up ultrasound procedures, CPT code 76805 (17.2% versus 7.8%, RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.39–0.53, p < 0.0001) after conversion. Despite similar proportions of new consults, there was an increase in the proportion of follow-up visits and medical decision-making complexity evaluation and management CPT codes (e.g. 99214/99215) after the conversion (17.2% versus 24.6%, RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.26–163, p < 0.0001). There were no differences between amniocentesis procedures performed between the two time periods (0.3% versus 0.2%, p = 0.5805).

Conclusion

The rapid conversion of an MFM platform from convention medical treatment to telemedicine platform in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic resulted in protection of healthcare personnel and MFM patients, with only a modest decrease in clinical productivity during the initial roll-out. Due to the ongoing threat from the novel coronavirus-19, an MFM telemedicine platform is a practicable and innovative solution and merits the continued support of CMS and health care administrators.

Keywords: Telemedicine, pregnancy, coronavirus-19, pandemic, COVID-19, telehealth, maternal care

Introduction

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have advocated the use of telehealth services to improve access for women’s health.1,2 In response to the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth services through an 1135 waiver.3 These policy changes allowed reimbursement rates similar to an in-person visit and expanded use of telecommunication platforms used by providers.3

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth services provided by Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) specialists included consultative services, remote monitoring of ultrasound recordings including fetal echocardiogram, genetic counselling, diabetes education, fetal heart rate monitoring and management of chronic medical disease (e.g. diabetes, chronic hypertension).1,4–8 Despite the advantages of a telemedicine platform for access to specialty care, state-specific regulations and facility-specific credentialing and privileging requirements in telehealth have resulted in barriers to its widespread adoption.1

The description of obstetric telehealth services for prenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic has recently emerged.9,10 Innovations such as a drive-through prenatal care model highlight the importance of adaptability and outside-the-box thinking to maintain care while protecting healthcare workers and patients. While routine prenatal care can be achieved through this model, MFM care requires a different approach, as the specialty is largely procedural based, including ultrasound exams and invasive prenatal testing.

We describe our experience with rapid conversion of our MFM outpatient clinic from a conventional medical treatment model to a telehealth clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic, and compare clinical productivity between the two models, taking into account the impact to our clinical providers and staff as a result of the pandemic.

Background

Clinic characteristics

The Center for Maternal and Fetal Care (CMFC) is located on three different campuses in the greater San Antonio area. We serve as a primary treatment and referral site for South and Central Texas with a referral base of over 100 providers. In 2019, we had over 10,000 annual visits. The CMFC providers include nine MFM specialists, two certified genetic counsellors and two certified diabetic educators. Clinic staff includes 10 sonographers, two nurses, three medical assistants, four front desk staff, one patient account coordinator and one administrative coding/billing specialist. There is immediate access to certified interpreters both in-person and through a language line. Individuals with disabilities have full access to the clinics. The clinic demographics for our three different campuses characterize the population we serve (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of our clinical sites in Bexar and Comal Counties in Texas.

| Pavilion | Westover Hills | New Braunfels | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Central | West | Northeast |

| Waiting room size (sq. ft) | 165 | 944 | 330 |

| Clinic size (sq. ft) | 4394 | 5134 | 4000 |

| Clinical staff on site | |||

| Front desk | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| RN | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| MA | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Sonographers on site | 5–6 | 2–3 | 1 |

| GC* | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CDE* | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Certified interpreter | 2, language line | Language line | Language line |

| MFM physician availability (average per day)* | 2.5 | 2 | 1 |

| Total visits in 2019 | 7127 | 3013 | 677 |

| New consult visits (%) | 1343 (18.8) | 679 (22.5) | 178 (26.3) |

| Payor mix (%) | |||

| Government | 4967 (69.7) | 1813 (60.2) | 310 (45.8) |

| Commercial | 1653 (23.2) | 1003 (33.3) | 349 (51.5) |

| Under/uninsured | 1661 (23.3) | 111 (3.7) | 16 (2.3) |

| Other | 320 (4.5) | 81 (2.7) | 2 (3.6) |

| Room types | |||

| Ultrasound | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Exam | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| NST | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Nursing station | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Consultation | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Telemedicine workspaces | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Physician workspaces | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Sonographer workspaces | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Research office | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Clinic manager office | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Genetic Counsellor office | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CDE office | 1 | 1 | |

| Ultrasound equipment | |||

| Type | GE Voluson E-10s | GE Voluson E-10s | GE Voluson E-10s |

| 3, GE Voluson P8 | |||

| Number of US machines | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Reporting system | ViewPoint PACs | ViewPoint PACs | ViewPoint PACs |

*Providers with telemedicine capability to all three clinics; RN: registered nurse; MA: medical assistant; GC: genetic counsellor; CDE: certified diabetic educator; GE: General Electric; US: ultrasound.

Pre-pandemic CMFC telemedicine platform

When we first opened our clinics in 2016 we utilized telehealth to extend patient care to one location approximately 31 miles northeast of San Antonio, prior to establishing a physical and permanently staffed clinic in 2019. Our telehealth team consisted of an on-site front desk staff and one sonographer, a remotely located single MFM physician, and remotely located certified diabetic educator and/or genetic counsellor as needed. We used the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA)-compliant telehealth platform Zoom™ to conduct the audiovisual visits. During this time, almost all of our providers, and some of our ultrasound technicians and clinical staff, participated in our telehealth platform. In the last year, our telehealth platform has consisted mainly of telehealth visits with our genetic counsellors and certified diabetic educators. The annual data for our satellite campus in Table 1 include visits performed with our telehealth platform that was in place for the first 5 months of 2019, and visits conducted in-person and via telehealth after the opening of our new office. In 2019, approximately half (48.2%) of the visits at that location were conducted via telemedicine.

Conversion to an MFM telemedicine platform

San Antonio, located in Bexar County, Texas, was officially declared to have community spread of the novel coronavirus on 19 March 2020 and a shelter-in-place order was established on 25 March 2020. We started converting our MFM practice to a telehealth clinic on 23 March 2020 after we received notification that 40% of our clinic staff had an exposure to a COVID-19 case, necessitating a 2-week quarantine, including four MFM physicians, and all of our certified diabetes educators and genetic counsellors.

The process of rapid conversion of our MFM clinic from a conventional medical treatment model to a telehealth clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic was a collaborative effort involving a team comprising an operations manager (MFM physician), a clinic manager, an information technology specialist, our lead sonographer and the clinical staff. We identified several barriers that required immediate solutions. Weekend notification of the quarantine left little time (approximately 36 hours) for the conversion from in-person patient care to a telehealth platform, so we had to act quickly. While an existing footprint for telehealth services was in place, this typically had to accommodate a single telemedicine visit with one physician, certified diabetic educator or genetic counsellor at each clinic. Therefore, a rapid expansion of the telehealth platform, to include technology to accommodate eight physicians, two genetic counsellors, two diabetic educators and eight ultrasound technicians simultaneously was needed, while ensuring compliance with regulations from the CMS. In addition, we had to ensure that all MFM providers were familiar with the appropriate coding and billing for telehealth services. Finally, because the personal protective equipment (PPE) for our hospital and clinics was sparse at the time, we required discussions with the COVID-19 Incident Commander, a clinician leader charged with coordinating our institution’s response to the pandemic, regarding protection of our clinical staff providing in-person patient care.

We had several virtual meetings over the 36 hours to plan for pivoting to a telemedicine platform. Because of the quarantining of nearly half the staff, we decided to open the telemedicine clinic in a single clinic location to have adequate staffing. We chose the campus with the largest waiting room and best layout for promoting social distancing. Our clinic administrator purchased two tablets for this clinic, as the workstations in each ultrasound room were not telehealth compatible. We planned to use the HIPPA-compliant Zoom™ platform to perform the telehealth visit. In addition, we had a virtual meeting with all available providers and clinical staff the evening prior to launching to discuss details of the telemedicine clinic and ensure everyone was prepared for the transition the next morning.

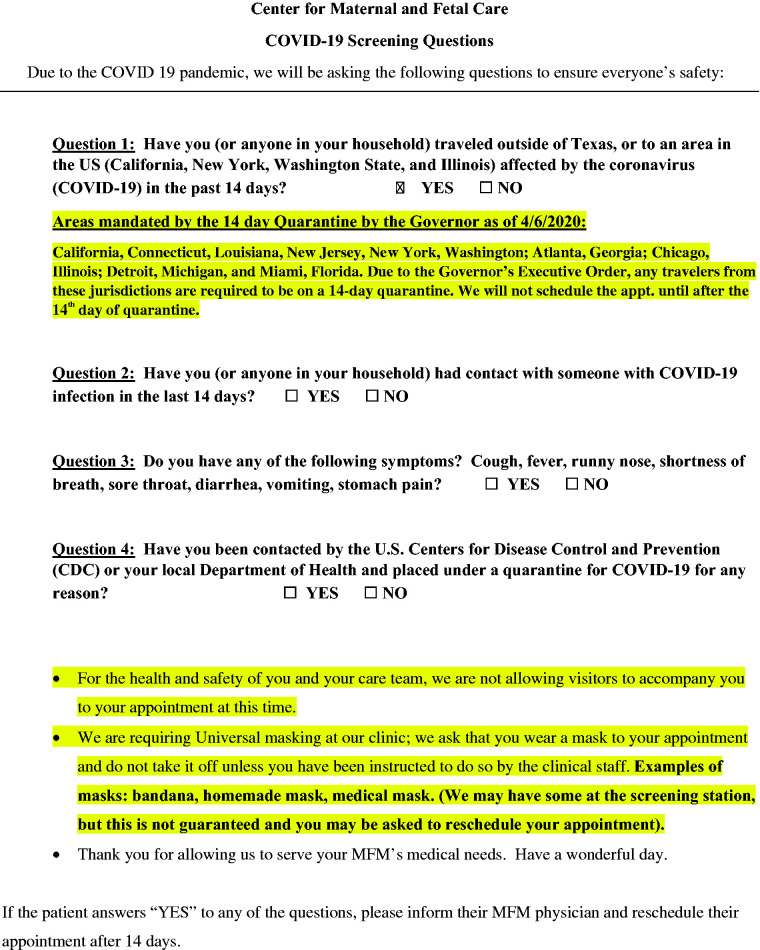

We had previously been performing novel coronavirus symptom screening by phone one day prior to scheduled appointments (Figure 1). Patients who screened positive for symptoms were told to inform their OB provider, and the appointment was rescheduled for 2 weeks later. Although we had previously instituted a policy of only one support person at the visit, with the conversion to the telemedicine clinic we planned to immediately inform patients that no guests were allowed into the clinic with the patient unless there were extenuating circumstances (e.g. patients with disabilities).

Figure 1.

Script used by clinical staff to screen for COVID-19 symptoms in clinic patients.

To ensure protection of clinic staff, we coordinated with the hospital COVID-19 Incident Commander, who was actually an MFM physician, regarding protection of our clinical staff providing in-person patient care. At the time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had not yet recommended universal masking for in-person patient care; however, we felt that continuation of a universal masking protocol for our MFM outpatient operations would be most appropriate, as social distancing could not be maintained for our staff providing in-person patient care, especially our sonographers. The Incident Commander subsequently approved our request. We asked the clinical staff to use one surgical mask every 72 hours unless it became soiled, which was consistent with hospital PPE policies. Gloves were changed after each patient encounter. Sonographers were also encouraged to wear eye protection during ultrasound examinations. All staff providing in-person patient care were briefed by the clinic manager on proper donning and doffing of PPE and social distancing guidelines.

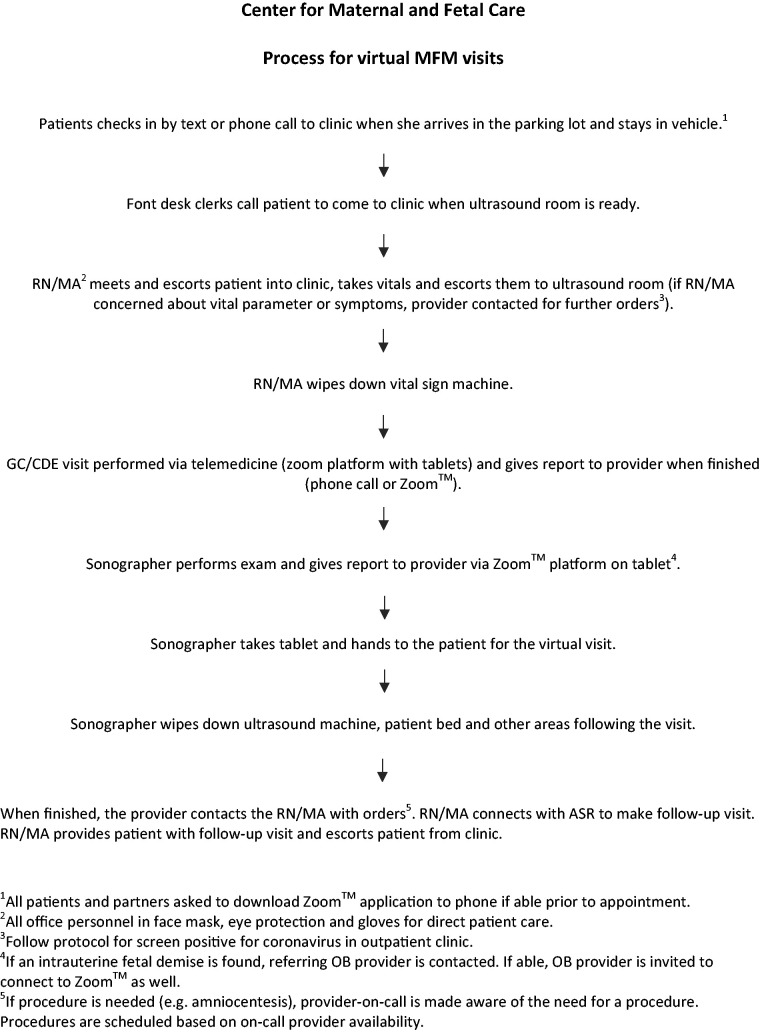

We developed a flow chart for the patient visit process (Figure 2), and shared this with the MFM providers and clinical staff prior to launching the telemedicine visit. We planned to utilize a virtual check-in process, whereby upon arrival for their appointment, the patient would call from the parking lot to check in. When they were ready to be seen, they were notified by phone to proceed to the clinic. Upon arrival, the patient would be greeted by our nursing staff and immediately taken to a room to collect vital signs and perform the intake, thus eliminating the patient waiting room experience. If they reported any concerning symptoms, the nursing staff was instructed to contact the MFM physician for further recommendations. If they passed this screen, they were placed in the ultrasound room and underwent the indicated procedures by the PPE-equipped ultrasound technician. After the ultrasound was completed, the sonographer would communicate with the physician and review the images; if no further imaging was recommended, the sonographer initiated a Zoom™ telehealth visit with the physician, usually keeping the patient in the same ultrasound room. If needed, the providers could dial in the genetic counsellor certified diabetic or language line translator to join the Zoom™ session. Physicians were instructed to confirm the patient’s identity and obtain verbal consent at the start of each visit. Documentation of the ultrasound procedure(s) and consult, including consent for telehealth visit, was performed in GE Viewpoint™ 6 PACS system, and coded in our electronic medical record. Physicians were provided with billing codes and modifiers for telehealth visits. Consult and procedure reports were sent to the referring provider following the visit. After the provider(s) met with the patient, the ultrasound technician or medical assistant would escort the patient to the lab collection area if indicated, or to the checkout area where the front desk staff scheduled any ordered follow-up appointments. The clinical staff and patients were encouraged to maintain social distancing as much as possible during the visit. All equipment, including blood pressure cuff, waiting room chairs (if used), ultrasound equipment and cords, and ultrasound beds were wiped down with an approved germicidal disposable wipe after each patient visit, and transvaginal probes were disinfected per standard protocols with Trophon® Sonex-HL®.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for telemedicine visits to the MFM clinics (RN: registered nurse; MA: medical assistant, ASR: ambulatory service representative).

A small group of our MFM physicians reviewed all appointments for the week and determined if the upcoming appointment was essential, or if the patient could be rescheduled based on guidelines adopted from a timely manuscript published by Boelig et al.10 These guidelines included recommended frequency and timing of MFM care during the novel coronavirus pandemic.4 The clinical staff then contacted each patient to inform them of the new telehealth process initiated to protect them, the providers and the clinic staff. The staff either provided patients with a reminder to keep the appointment or rescheduled the appointment based on the MFM physician recommendation that the appointment could be safely delayed (typically by 1–3 weeks). We also sent a letter to all of our patients explaining the need for conversion to a telehealth visit with their provider via Zoom™ platform (Appendix).

Our initial goal in implementing the telehealth platform was to maintain patient access to care while accommodating the loss of clinical staff and providers from quarantine. We also aimed to continue the telemedicine platform following the quarantine to optimize and preserve PPE needed throughout the novel coronavirus pandemic, and reduce the chance that more staff or providers would become ill with COVID-19.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Baylor College of Medicine (H-47839). We reviewed outpatient clinic metrics for all patient visits for the 8-week period (40 clinic days between 23 March 2020 and 18 May 2020) following implementation of the telemedicine platform, compared with the 8-week period (40 clinic days between 27 January 2020 and 20 March 2020) of pre-pandemic conventional medical care immediately prior to the telehealth platform conversion. We performed a search of our outpatient electronic health record (AthenaHealth™) for the pre-specified time period for total patient visits, total no-shows, evaluation and management (E&M) current procedural technology (CPT) codes, and ultrasound and invasive procedure CPT codes. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft© Excel for Mac version 16.36 and MedCalc for Windows, version 15.0 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). A t-test comparison of means was performed to detect differences in observed means between the pre- and post-conversion cohorts, and reported as the difference ± standard errors of mean with 95% confidence intervals. A relative risk (RR) ratio was used to detect differences in productivity outcomes between the two cohorts with 95% confidence intervals. A chi-square test of independence was done to evaluate patient satisfaction scores between the two cohorts. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We found that 100% of providers utilized the telehealth platform, with nine of our 11 providers using audiovisual interactions from their homes and the other two providers utilizing offices within the clinics. Phone consultation was available if audiovisual interaction was not feasible; phone consultation was generally limited to telehealth consultations to the patient’s home for follow-up discussion regarding testing results and/or for counselling with our diabetes educator or genetic counsellor when the patient did not have access to a HIPPA-secure audiovisual platform. A single on-call MFM provider was available for in-person patient care in the event procedures such as an amniocentesis or cervical examination were required. All clinical staff rendering in-person patient care wore surgical masks and gloves starting the day of the conversion. Our health system instituted a policy of masking the patient on 3 April 2020, which was reinforced by our local government who implemented a universal face covering policy for all citizens on 17 April 2020.

We initially consolidated all of our visits to a single clinical site with the largest footprint, mainly due to the initial lack of clinical staffing to run three clinics. However, we realized on the first day of the telemedicine clinic visits that it was hard to promote social distancing for staff, so we requested additional clinical support from across our hospital system, and on day two we were able to open up a second clinic location. By the end of the first week, we had resumed operations at all three clinics, allowing for improved social distancing and increased patient access, corresponding with increased efficiency with telehealth operations. Fortunately, the second and third clinics were already equipped with much of the necessary audiovisual capability to perform telehealth. The additional equipment cost for conversion to telehealth from our conventional model platform to a telemedicine platform was US$2150.00 (two tablets, five cameras), making it a very cost-effective transition.

There was a total of 40 clinic days in the 8 weeks prior to the clinic conversion from the novel coronavirus, and a total of 40 clinic days in the 8-week period after conversion to a telemedicine platform. Total physician visits were 2134 prior to conversion, and 1570 post-conversion. Average visits per day were 53.35 (range, 24–71) prior to conversion, and 40.33 (range 24–58) after the conversion to a telemedicine platform.

Prior to the conversion three of our clinical staff were diagnosed with the novel coronavirus, with two being some of the first cases of community spread in San Antonio. In the 8 weeks following conversion to a telemedicine clinic, we had no symptomatic cases of the novel coronavirus, although we did not perform universal testing for clinical staff to assess for asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cases. About half of our MFM providers and one-quarter of our clinical staff were tested during the quarantine period and were found to be negative. Some 40% of our perinatal sonographer staff was unable to provide in-person patient care following exposure due to required quarantine; therefore, only six sonographers were available for in-person patient care during the telemedicine clinic period. All certified genetic counsellors and certified diabetic educators were quarantined. Also, during the telemedicine period, capacity to provide in-person MFM physician full-time equivalent (FTE) staffing for clinics was reduced by 21% (4.8 FTE to 3.8 FTE). Reductions resulted from quarantine (two MFM providers), acute COVID-19 infection (one MFM provider) and redirection of clinical efforts to COVID-19 hospital leadership response (one MFM provider). In response to this immediate and dramatic reduction in in-person patient care clinical capacity, all clinically available physicians (including those in quarantine) provided telehealth care, and those who had previously been allocated for less than one FTE of clinical work expanded their clinical efforts, resulting in an average net increase of clinical capacity of 9.4% (4.8 FTE to 5.3 FTE) during the telemedicine period (Table 2). While the average visits per day decreased, the average number of daily patients seen per FTE only modestly decreased from an average of 11.1 visits per FTE versus 7.6 visits per FTE, p < 0.0001 (Table 2). The immediate financial impact of the conversion was a net reduction in adjusted work relative value units (wRVUs) of 22%, resulting in a 17% reduction in net payment in professional fees despite fewer denials during the post-conversion period (Table 3).

Table 2.

Change in clinic productivity prior to and following conversion to a telemedicine MFM clinic.

| Pre-conversion | Post-Conversion | Difference +/−SEM(95% confidence interval) | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total clinic days | 40 | 40 | |||

| Total physician visits | 2134 | 1570 | |||

| Average clinical FTEs (physician) | 4.8 | 5.3 | |||

| Average visits per day | 53.35 | 40.33 | –13.0 ± 0.28 | <0.0001* | |

| (range) | (24–71) | (24–58) | (–12.4 to –13.6) | ||

| Average visits per day per average clinical FTE | 11.1 | 7.6 | –3.50 ± 0.30 | <0.0001* | |

| (5.0–14.8) | (4.5–10.9) | (–2.92 to –4.08) | |||

| Total no-shows (%) | 878 (29.2) | 427 (21.4) | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | <0.0001* | |

| Ultrasound CPT codes | 3564 | 2717 | |||

| Total count (%) | |||||

| 76801 | 114 (3.2) | 86 (3.2) | 0.9896 | ||

| 76802 | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.1) | 0.638 | ||

| 76805 | 613 (17.2) | 213 (7.8) | 0.46 (0.39–0.53) | <0.0001* | |

| 76810 | 14 (0.4) | 10 (0.4) | 0.8748 | ||

| 76811 | 410 (11.5) | 338 (12.4) | 0.2562 | ||

| 76812 | 17 (0.5) | 9 (0.3) | 0.3755 | ||

| 76813 | 70 (2.0) | 59 (2.2) | 0.5659 | ||

| 76814 | 5 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0.7428 | ||

| 76815 | 51 (1.4) | 18 (0.1) | 0.46 (0.27–0.79) | 0.0048* | |

| 76816 | 383 (10.7) | 529 (19.5) | 1.81 (1.60–2.05) | <0.0001* | |

| 76817 | 105 (2.9) | 113 (4.2) | 1.41 (1.09–1.83) | 0.0096* | |

| 76818 | 29 (0.8) | 24 (0.9) | 0.7651 | ||

| 76819 | 1186 (33.3) | 834 (30.7) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.0305* | |

| 76820 | 279 (7.8) | 160 (5.9) | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.0030*1 | |

| 76821 | 49 (1.4) | 35 (1.3) | 0.7671 | ||

| 76825 | 111 (3.1) | 131 (4.8) | 1.55 (1.21–1.98) | 0.0005* | |

| 76826 | 18 (0.5) | 18 (0.7) | 0.4142 | ||

| 93325 | 104 (2.9) | 131 (4.8) | 1.65 (1.28–2.13) | 0.0001* | |

| E&M CPT codes | 2134 | 1570 | |||

| Total count (%) | |||||

| 99243 | 126 (7.6) | 53 (0.3) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78) | 0.0005* | |

| 99244 | 122 (7.1) | 51 (0.3) | 0.57 (0.41–0.78) | 0.0005* | |

| 99245 | 68 (4.0) | 33 (2.1) | 0.66 (0.44–0.99) | 0.0471* | |

| 99212 | 150 (6.6) | 17 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.09–0.25) | <0.0001* | |

| 99213 | 1209 (51.0) | 833 (53.1) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.0308* | |

| 99214 | 346 (17.0) | 340 (21.7) | 1.34 (1.17–1.53) | <0.0001* | |

| 99215 | 20 (1.1) | 46 (2.9) | 2.30 (1.37–3.87) | 0.0017* | |

| 99203 | 20 (1.2) | 43 (2.7) | 2.16 (1.28–3.65) | 0.0041* | |

| 99204 | 54 (3.2) | 99 (6.3) | 2.49 (1.80–3.45) | <0.0001* | |

| 99205 | 19 (1.1) | 55 (3.5) | 3.93 (2.35–6.60) | <0.0001* | |

| 99244/45 vs. 99204/05 | 190 (8.9) | 154 (9.8) | 0.348 | ||

| 99214/99215 | 366 (17.2) | 386 (24.6) | 1.43 (1.26–1.63) | <0.0001* | |

| Amniocentesis CPT codes | |||||

| 59000 | 6 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 0.5806 |

*Denotes statistical significance. SEM: standard error of the mean; N/A: not applicable; FTE: full-time equivalent; CPT: current procedural technology; E&M: evaluation and management.

Table 3.

Comparison of professional component financial data during the pre-conversion period versus the post-conversion (telemedicine) period in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Pre-conversion | Post-conversion | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Work RVUs | 6987 | 5440 |

| Claims | 3941 | 2634 |

| Denials | 417 | 215 |

| Net payment (USD) | $224,483 | $185,565 |

RVU: relative value units. Ultrasound technical component and facility fees are not reflected.

All of the contacted patients agreed to the telehealth visit. In the first 3 weeks after conversion, an average of 2–3 patients a day would present for a visit who we were unable to contact, and in these instances the patient was immediately taken to a private room to promote social distancing and worked into the schedule. Our patient no-show rate decreased by 34% during the telemedicine period (Table 2).

The rates of several E&M codes and ultrasound procedures also changed following implementation of the telemedicine clinic. As expected, the use of telehealth E&M codes for new consults (e.g. CPT codes 99203–99205) exceeded E&M codes for in-person new consults (e.g. CPT codes 99243–99245) after implementation of the telemedicine clinic. Ultrasound CPT code 76805 decreased (17.2% versus 7.8%, RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.39–0.53, p < 0.0001) while ultrasound CPT code 76816 increased (10.7% versus 19.5%, RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.60–2.05, p < 0.0001). There was an 85% decrease in established low-complexity visits (E&M CPT code 99212) after implementation of the telemedicine clinic (6.6% versus 1.1%, RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.09–0.25, p < 0.0001). We decided to not include the low-complexity telemedicine visit codes in the analysis as each group had fewer than 10 patients, and they were roughly equal sized between time periods. There were significantly more established visits, and more established visits coded at a higher medical decision-making complexity, after conversion to a telemedicine platform compared with the pre-pandemic period (e.g. E&M CPT 99214/99215), (17.2% versus 24.6%, RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.26–1.63, p < 0.0001). The numbers of invasive procedures for both time periods were not significantly different (p = 0.5805). Curiously, there was a relative increase in the proportion of fetal echocardiograms performed during the telemedicine platform versus pre-pandemic period (4.8 versus 3.1%, RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.21–1.98, p = 0.0005).

We had 31 responses to our Press Ganey® patient satisfaction surveys during the pre-conversion period versus 23 responses during the telemedicine period. Patients rated six domain items the pre-conversion period, including access, care provider, nurse/assistant, moving through your visit, telemedicine technology, personal issues and overall assessment. In the post-conversion period, a survey of telemedicine technology was added for a total of seven domain items assessed. Table 4 outlines the results. The majority of items were rated as positive in both periods. There were five positive comments that specifically mentioned the safety precautions that the clinic took to keep patients safe during the pandemic period. The majority of negative comments had to do with wait times in both periods, but there were two comments disagreeing with our policy of not allowing partners to accompany the patient into the clinic for the visit following the telemedicine conversion. There were also four comments observing incorrect mask wearing (below the nose) and/or social distancing practice during the telemedicine conversion. A chi-square test of independence showed that there was no significant association between pre- and post-conversion and patient satisfaction in any domain (p-value > 0.05, Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Press Ganey® patient satisfaction survey responses during the pre-conversion period versus the post-conversion (telemedicine) period in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

Responses |

p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Neutral/Mixed | Negative | |||

| Domain | |||||

|

|

Total # responses (n) |

||||

| Access | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 31 | 77% | 6% | 16% | 0.8629 |

| Post-conversion | 23 | 83% | 4% | 13% | |

| Care Provider | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 10 | 60% | 30% | 10% | 1.0000 |

| Post-conversion | 10 | 70% | 20% | 10% | |

| Nurse/Assistant | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 10 | 80% | 20% | 0% | 0.6440 |

| Post-conversion | 6 | 83% | 17% | 0% | |

| Moving Through Visit | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 7 | 43% | 28% | 29% | 0.7247 |

| Post-conversion | 9 | 67% | 0% | 33% | |

| Telemedicine Technology | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | N/A |

| Post-conversion | 1 | 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| Personal Issues | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 5 | 60% | 40% | 0% | 0.5614 |

| Post-conversion | 3 | 67% | 0% | 33% | |

| Overall Assessment | |||||

| Pre-conversion | 3 | 33% | 66% | 0% | 0.5614 |

| Post-conversion | 5 | 40% | 0% | 60% | |

Discussion

Due to a quarantine of 40% of our staff and focus on expanding telehealth services for MFM patients during the novel coronavirus pandemic, our MFM clinic rapidly expanded to HIPPA-compliant, interactive audiovisual telehealth visits. Advantages of this new telehealth platform included promotion of social distancing, a reduction in healthcare visits for the patient, conservation of PPE, and protection of more healthcare workers from contracting the novel coronavirus.

There were several observed changes in the E&M and procedures performed during patient visits following the conversion. The increase in medical decision-making complexity in follow-up visits during the telemedicine platform likely resulted from increased time given for each patient encounter on the telemedicine platform, coupled with scaling back of the clinic to the most essential (highest complexity) patient visits. The shift to keeping appointments for higher complexity patients only may also explain the relative increase in fetal echocardiograms performed in our telemedicine clinic, and the significant reduction in low-complexity visits (E&M CPT code 99212). The observed reduction in comprehensive anatomic follow-up procedures (CPT code 76805) and increase in basic follow-up procedures (CPT code 76816) was anticipated, and expected, as prior to the pandemic, we had made an internal decision to change our approach to follow-up visits and deliberately perform and subsequently use the ultrasound CPT code 76816 for the majority of follow-up scans. This serendipitous change also provided the benefit of reducing in-person patient exposure to our front-line sonographer staff. Our analysis only captured E&M and procedure-based CPT codes and not cost revenue, so we did not perform a cost utility analysis of the telemedicine MFM clinic.

Despite the reduction in patient access after conversion to a telemedicine clinic, we only saw a modest decrease in our clinical productivity per FTE with the initial roll-out. This was partly due to our quarantined providers and clinical staff easily and quickly adapting to the expanded telemedicine platform because of their prior experience with telehealth, and partly due to the significant decline in the patient no-show rate by 34% in the 8 weeks after implementation of the telemedicine clinic. We speculate that the no-show rate dropped dramatically due to scaling back of the clinic to the most essential visits during this time, which may have self-selected for more compliant, higher risk patients. Sheltering-in-place ordinances and decreased economic activity likely resulted in fewer work-related time constraints, allowing patients to answer phone calls reminding them of the scheduled visit and have greater flexibility to come for their clinic visit. Finally, the increased need for patient reassurance during the early days of the pandemic, when fear and uncertainty were highly prevalent, may have also contributed to a reduction in the no-show rate.

The impact of the immediate conversion and staffing reductions due to the pandemic ultimately resulted in a decrease in adjusted work RVUs and claims dropped during the post-conversion period. This was to be expected with the anticipated reduced efficiency of the initial immediate roll-out of expanded telemedicine services, and the intentional reduction in the numbers of patient visits in the early weeks of the conversion in anticipation of a potential influx of COVID-19 patients. Net payment decreased by 22%, but this difference may be exaggerated due to pending payment for denials from the post-conversion period. Also, our financial analysis only reflected the professional component financial data; technical and facility financial data were not provided. While not included in this analysis, the efficiency of our telehealth platform continues to improve, and in July 2020 the volume of clinical visits was the highest since January 2020, despite a surge in COVID-19 cases in our community.

Feedback from patients on the use of telehealth platforms was generally positive. At the very beginning of the transition, several patients did not respond to our phone calls or voicemails describing the rapid transition and our new policy that only the patient would be allowed to attend the visit. Specifically, there were two separate instances where security had to be called by our front desk staff to intervene and/or escort an upset partner from the premises. Based on these interactions, we quickly pivoted to invite loved ones to join the Zoom™ session if desired, and participate in the telehealth consultation including physician-guided review of the ultrasound. In addition, based on negative feedback on mask wearing and social distancing practices on our Press Ganey® patient satisfaction surveys early on, we now routinely reinforce the correct procedures for mask wearing and social distancing to our staff.

The MFM providers were initially worried about the lack of robust in-person care diminishing the quality of care. However, after the roll-out most thought that the quality of care provided during the telehealth visit was superior to that of a conventional model; they were able to provide a more focused visit with fewer of the external distractions that are present in daily, in-person operations of the clinic. MFM providers were also concerned about the lack of efficiency and patient access with a telemedicine platform, and this was observed in the initial roll-out of the clinic in total number of patient visits, which ultimately reflected the loss of in-person clinical productivity. However, as we gained experience in the telemedicine platform, we gained increased efficiency and patient access per FTE. Finally, many MFM providers expressed more personal satisfaction due to lack of commute times and increased after-hours personal time.

MFM physician leaders must continue to implement innovative solutions for the delivery of ambulatory care during the pandemic, centred on access to care and the promotion of patient safety and quality while maintaining a healthy workforce. The conversion of the MFM clinical operations from providing in-person care to telemedicine care is an innovative and necessary solution. The continued support for expansion of telehealth services from CMS, and from organizations such as ACOG and SMFM, is critical to the continued promotion of health and safety of MFM patients and healthcare providers during the novel coronavirus pandemic and beyond.

Appendix. Sample letter to patients explaining the transition to a telehealth clinic due to novel coronavirus 2019 pandemic.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Drs. Shields and Nielsen have grant funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and are co-owners of a health education consulting company.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Andrea D Shields https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6729-503X

References

- 1.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 798 . American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Implementing telehealth in practice. Obstet Gynecol 2020; e73–e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rad S, Smith D, Malish T, et al. SMFM Coding White Paper: Interim Coding Guidance: Coding for Telemedicine and Remote Patient Monitoring Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.smfm.org/covid-19-white-paper (2020, accessed 15 May 2020).

- 3.Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet (2020, accessed 30 May 2020).

- 4.Magann E, McKelvey S, Hitt W, et al. The use of telemedicine in obstetrics: A review of the literature. Obstetr Gynecol Survey 2011; 66: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odibo I, Wendel P, Magann E.Telemedicine in obstetrics. Clin Obstetr Gynecol 2013; 56: 422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowery C, Ott R. Statewide telehealth program enhances access to care, improves outcomes for high-risk pregnancies in rural areas. AHRQ Health Care Innov Exchange, https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/statewide-telehealth-program-enhances-access-care-improves-outcomes-high-risk-pregnancies (2014, accessed 9 July 2020).

- 7.Greiner A.Telemedicine applications in obstetrics and gynecology. Clin Obstetr Gynecol 2017; 60(4): 853–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fryer K, Delgado A, Foti T, et al. Implementation of obstetric telehealth during COVID-19 and beyond. Matern Child Health J 2020; 24: 1104–1110. DOI: 10.1007/s10995-020-02967-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turrentine M, Ramirez M, Monga M, et al. Rapid deployment of a drive-through prenatal care model in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obstetr Gynecol 2020; 136: 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boelig RC, Saccone G, Bellussi F, et al. MFM guidance for COVID-19. Am J Obstetr Gynecol2020; 2 (Suppl.): Article 100106. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]