Abstract

Although work stress, turnover intention, and work–family conflicts among police officers have been extensively investigated, no studies have explored these issues simultaneously under the context of the coronavirus pandemic. Clearly, both work and family domains have been drastically affected by this global health crisis, and it is likely that each domain has a distinctive impact on work outcomes. Using survey data based on a representative random sample of 335 police officers in Hong Kong, this study examines the impacts of resource losses and gains across family and work domains on occupational stress and turnover intention amid the pandemic. A multiple regression indicates that both family-to-work and work-to-family conflicts lead to work stress and turnover intention among police officers. Among officers, supervisory support is negatively associated with turnover intention and moderates the impact of work-to-family conflicts on turnover intention. Finally, measures to mitigate work stress during public health disasters are discussed.

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, police, turnover intention, work stress, work–family conflict

Many studies have shown that police work is highly stressful (Anshel, 2000; Goodman, 1990; He et al., 2002), and enforcing the law as a Hong Kong police officer is no exception (Li et al., 2019; Lo, 2012). Work stress becomes inevitable when the balance between work and family is disrupted. The recent coronavirus pandemic has had a major effect on both the work and family domains of police officers. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak as a pandemic. As of April 10, 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected 223 countries worldwide, with more than 13.4 million confirmed cases and a death toll exceeding 2.9 million (WHO, 2021). COVID-19 is the most significant public health crisis of our time and a public order concern. As one of the most densely populated places in the world (with 6,690 persons per square kilometer), Hong Kong is especially vulnerable to this pandemic.

The literature demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative effect on police officers’ working situations and family relationships. For example, De Camargo (2021) used data collected via interviews with 18 police officers in the U.K. to reveal the connection between continued lack of support in the workplace and the detachment and displacement of anxiety and fear related to working during a pandemic. Police officers’ stress during the pandemic can be attributed in part to changes of work schedules and job routines (Stogner et al., 2020). In China, police officers’ stress levels were linked to their background characteristics, such as age, education, and marital status (Yuan et al., 2020). Police officers worried about bringing the infection home (Frenkel et al., 2021), and thus avoided contact with their own families (Stogner et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic and related precautionary measures have imposed additional job demands on police officers. First, in addition to medical and public health professionals, police officers shoulder some of the responsibility of controlling the spread of the virus. They are required to stop, detain, and arrest individuals suspected of violating public preventive measures and laws, which can create tension between them and the public. Second, police officers assist health officials in handling the prevention and inspection of passengers in airplanes and public transportation, which unavoidably increase work volumes and the pressure on the time spent with their families. Third, officers have close daily contact with the public and face a higher risk of being infected with the disease than those in other professions. These aspects can trigger worry or anxiety in officers and their families.

Survey data used in this study were collected between May and July 2020, when Hong Kong faced social unrest and the outbreak of COVID-19. On January 23, 2020, the first positive case of COVID-19 was confirmed. A steady increase in confirmed cases has since been reported, from 17 in January 2020 to more than 1,000 in April 2020, 3,000 in July 2020, and more than 11,000 in March 2021 (Hong Kong Government, 2020). The Hong Kong government has imposed and advised a series of precautionary measures, including (a) border control and social distancing; (b) contact tracing, testing, and mandatory quarantine; (c) screening and surveillance; and (d) regular public updates (Wong et al., 2020). The Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance (2021a; 2021b; 2021c) (Cap. 599) was released, covering mandatory quarantine (Cap. 599 C and Cap. 599E), the prohibition of public gatherings (Cap. 599 G), and mandatory mask-wearing in public (Cap. 599I). Law enforcement agents must send reminders and warnings to citizens, and arrest violators who fail to comply with these legal requirements. For example, the first prosecution under the Ordinance was reported in April 2020, when six people were each fined HKD2,000 (US$258) for playing chess together in a public housing estate, in breach of social-distancing laws (Lo, 2020a). In the same month, another 30 people were fined for the same act in a Hong Kong park (Lo, 2020b).

The job of enforcing the law in relation to COVID-19-related precautionary measures has become complicated in the midst of social unrest and mistrust. It has been difficult to ensure that citizens comply with law and order in Hong Kong, especially since the 2019 Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Movement. On January 29, 2019, the Hong Kong government announced potential amendments to its extradition laws—the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance Cap. 503 (2017)—that would allow suspects to be extradited to places with which Hong Kong has no formal extradition agreement. This move proved to be very controversial and was followed by prolonged social unrest, demonstrations, riots, and arrests. Public speculation that the police intentionally used the ban on group gatherings to suppress protests rather than promote social distancing has exacerbated police–citizen conflicts (Marlow & Hong, 2020a).

Following the arrests of 15 high profile pro-democracy protest leaders in Hong Kong on April 20, 2020, the announcement by Beijing authorities that the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) would introduce national security legislation applicable to Hong Kong on May 22, 2020, and in anticipation of the 1-year anniversary of the first major clashes in the 2019 social unrest on June 12, 2020, rallies, demonstrations, violence, and arrests occurred every weekend in May and June 2020, despite social distancing rules limiting group gatherings to control the spread of the virus. On a single day in May 2020, 230 people were arrested for unlawful assembly and other offenses such as assaulting police officers, and penalty tickets were issued to 19 people for violating the gathering ban in weekend rallies (Marlow & Hong, 2020b). Clearly, the COVID-19 did not slow down much Hong Kong people’s protests against the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance (2017). During close and frequent encounters with the public, officers have faced a high risk of virus exposure and infection, and increased workloads due to the protests, disrupting the balance between work and family demands.

Investigations of work–family and work–life conflicts among police officers have been conducted extensively (Hall, 2010; Howard et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2005; Mikkelsen & Burke, 2004; Qureshi et al., 2016). However, no such studies have been conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. Several recent studies examined police officers’ work-related experiences in mainland China (Sun et al., 2016), Hong Kong (Siu et al., 2015), and Taiwan (Kuo, 2015). These studies relied on non-random convenience samples, which limited the representativeness of the collected responses. This study was based on a third wave of data collected from a representative random sample to fill the knowledge gap. We applied the conservation of resources (COR) theory to reveal the impact of work–family conflicts on work stress and turnover intention among police officers in Hong Kong during the pandemic. This study addressed the following research questions: (1) To what extent have Hong Kong police officers experienced work stress and turnover intention during the pandemic? (2) Have officers’ demographic characteristics affected their work stress and turnover intention amid the pandemic? (3) Do COR-related variables influence police work stress and turnover intention? (4) To what extent do family support, supervisory support, and personal coping techniques mitigate work stress and turnover intention?

Literature Review

Conservation of Resources Theory

It is logical to adopt Hobföll’s (1989, 2001) COR theory to understand stress related to police work engagement during the pandemic. First, COR theory has been supported by empirical studies on stress (Gong et al., 2020; Wolter et al., 2019) and work–family conflicts (Hall et al., 2010; G. He et al., 2019) among police officers, forming a solid basis for the current study. Secondly, as articulated by Hobföll (1989) and echoed by Snyder et al. (2020), the COR model is more directly testable, comprehensive, and parsimonious than previous approaches. More importantly, our research team observed that policing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to involve resource loss and gain, which is in line with the core concepts of the COR model.

Police officers’ resource conservation has been substantially disrupted by the pandemic. Foundational to this study, COR theory defines psychological stress as

a reaction to the environment in which there is (a) the threat of a net loss of resources, (b) the net loss of resources, or (c) a lack of resource gain following the investment of resources. Both perceived and actual loss or lack of gain are envisaged as sufficient for producing stress. (Hobföll, 1989, p. 516)

COR theory assumes that “humans are motivated to protect their current resources and acquire new resources” (Halbesleben et al., 2014, p. 1335). Stress is caused by inadequate resources to accommodate demands from the external environment, and inadequacy refers to a resource loss that outweighs a resource gain. The mitigation of work stress depends on how well individuals can acquire, retain, and reserve resources.

Although resource can refer to anything that an individual perceives as helpful for meeting their work goals (Halbesleben et al., 2014), Hobföll (2001) identified 74 resources, including “time for work,” “time with loved ones,” “intimacy with spouse or partner,” “understanding from employer/boss,” and “help with tasks at home.” Families and workplaces are two major sources of human need fulfillment (resource gain). Supervisory support (SS; Cullen et al., 1985) and family support (FS; Shim et al., 2015) reduce work stress among police officers. However, families and workplaces also impose significant demands on individuals (resource loss).

According to COR theory, the lack or removal of salient workplace resources has spillover effects on the quality of the home life (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). Increased conflict at home can lead to emotional exhaustion (Netemeyer et al., 1996), which can spread to the workplace. Work–family conflicts result from an imbalance between resources and demands across the two domains. This dynamic can worsen when individuals cannot retain or gain resources from either system. The resources and demands from families and workplaces are critical to understanding work stress. During a pandemic, police officers are likely to experience resource loss owing to work demands, such as increased working hours and disruption of job routine. However, resource gain, such as instrumental and emotional support from their families, is unlikely due to restricted contact with family members.

The conservation of current resources and the acquisition of new resources from the two domains are not well understood. The influence of work–family conflicts on various work outcomes, such as work stress and turnover intention, remains relatively unexplored in Hong Kong, a city with unique social and political background. With this study, we intended to fill this gap by empirically examining the relationships between work stress; turnover intention; work–family conflicts; and individual, family, and workplace resources among police officers in Hong Kong. We contend that resource gains and losses are related to increased and decreased work stress, respectively. A resource loss in a work–family conflict is likely to increase police work stress, whereas the support of family members and supervisors and the use of positive personal coping mechanisms can help police officers to gain resources, which can decrease work stress.

Work Stress

Work–related stress is “the response people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities and which challenge their ability to cope” (WHO, 2020). Such stress is detrimental to police officers, leading to psychological disorders (Brown & Campbell, 1994; He et al., 2002) and deteriorating job performance (Goodman, 1990). Stress has also been correlated with health concerns, such as sleeplessness, digestive issues, and cardiovascular problems (Scholarios et al., 2017).

Several studies have shown that officers’ occupational stress is related to their demographic characteristics. Older officers appear to be resilient to negative affective responses to strain (Bishopp et al., 2018). Age does not appear to be a strong risk factor for burnout among police officers (Wickramasinghe & Wijesinghe, 2018). Female officers have reported higher levels of psychological stress than their male counterparts in the form of somatization and depression (He et al., 2002); however, several studies have not been able to confirm this association (e.g., Acquadro Maran et al., 2014). With respect to officers’ stress and rank, several studies have revealed that police constables encounter more occupational stress than higher ranking officers (Fielding, 1988), whereas other studies have indicated that sergeants experience the most stress (Gudjonsson & Adlam, 1985). No consistent conclusion has been reached regarding stress and rank. Similarly, the association between education level and stress varies across studies. In one study, college-educated officers reported higher stress levels than their less-educated counterparts, and the authors found that bureaucratic restrictions often alienated better-educated officers (Zhao et al., 2002). However, Griffin and Sun (2018) found that better-educated officers reported less stress than less-educated officers. One study found that married officers tend to experience more stress in relation to family and work (Qureshi et al., 2016), but another study found that married male officers were more likely to have a lower level of depression than their unmarried counterparts (He et al., 2005). Clearly, more research is needed on the relationships between officer demographics and occupational stress.

Turnover Intention

Turnover intention refers to the subjective probability of an individual to leave his or her organization in the near future (Mowday et al., 1984), and it is the best predictor of voluntary turnover (Lambert, 2006). The resignation of police officers is costly. The direct financial costs involve recruiting, selecting, and training police personnel, and the indirect costs consist of disruptions in services and organizational efficiency, the waiting period for police recruits to achieve competence on the job, and the provision of fewer services to citizens (Harris & Baldwin, 1999). Maintaining stable, reliable police manpower is essential for community safety. Exploring the correlates to voluntary turnover intent among police officers is therefore warranted.

An officer’s voluntary turnover can result from conflicts between the officer’s ideal of policing and the reality (Haarr, 2005), personal emotional instability (Cortina et al., 1992), or abusive supervision (Saleem et al., 2021). Female officers have reported gender-specific reasons such as family concerns (Doerner, 1995) and gender discrimination in the workplace (Haarr, 2005). The Hong Kong government reported that more than 1,300 civil servants (including police officers) resigned from their positions in 2017–2018, resulting in a resignation rate of 0.8%. Approximately 24% of the resigned staff members cited marriage or family as a major reason for leaving (Research Office, Legislative Council Secretariat, 2020). Work–family conflict appears to be correlated with turnover in Hong Kong. However, the extent to which it contributes to police turnover in Hong Kong warrants further examination.

Work–Family Conflict

Work-family conflict has been conceptualized as “a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” and it can take three forms: (a) time-based conflict, (b) strain-based conflict, and (c) behavior-based conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77). Work–family conflicts can contribute to work stress among police officers (He et al., 2002, 2005). Police officers have a high chance of encountering different forms of work–family conflicts (Qureshi et al., 2016; Youngcourt & Huffman, 2005). These include (a) time constraints (e.g., irregular work hours in the police force can make interactions with family members difficult), (b) strain (e.g., the dangerous and unpredictable nature of the job can make officers tense during their shift and after work), or (c) behavior (e.g., police officers often act firm, detached, and suspicious of suspects and can cause tension in the home if they interact with family members in such a manner).

Stress in one domain can also spread to another, leading to a work–family conflict (Mikkelsen & Burke, 2004). This study examined two types of work–family conflicts. A work-to-family conflict (WFC) is “a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and stress created by a job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities” (Netemeyer et al., 1996, p. 401). Reversely, a family-to-work conflict (FWC) refers to “a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and stress created by family interfere with performing work-related responsibilities” (Netemeyer et al., 1996, p. 401).

Personal Coping, Family Support, and Supervisory Support

Personal, family, and organizational resources are supposed to mitigate work stress. Workplace resources help workers to complete their tasks and make work pleasant (Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012). The removal or absence of workplace resources can result in stress and frustration for workers (Alarcon, 2011). Support from an immediate supervisor is an essential resource for reducing work-related stress (Ellrich, 2016). Supervisor support (SS) is the most important source of work-based support in terms of alleviating stress, whereas the impact of co-worker support is relatively low (Ganster et al., 1986).

Family support (FS) is vital for counteracting job stress (Nohe & Sonntag, 2014). Talking to family members and friends has been found to act as a buffer between the authoritative organizational culture and organizational commitments (Choi et al., 2020). Spousal support has been shown to moderate the effect of parental overload on FWCs (Aryee et al., 1999). However, research has indicated that FS does not moderate the effect of a WFC on an employee’s turnover intention (Nohe & Sonntag, 2014).

Constructive coping (CC) mechanisms are “positive, productive and active responses intended to deal with stress” (McCarty et al., 2007. p. 680). Coping mechanisms can focus on problems or emotions (Kalliath & Kalliath, 2014). Problem-focused coping involves identifying steps for problem-solving, whereas emotion-focused coping leads individuals to seek emotional support, such as empathy, understanding, and encouragement, from their social networks.

Working Conditions of Hong Kong Police Officers

The Hong Kong Police Department is the largest regulatory organization in the region, with a workforce of 32,992. As of August 30, 2020, it accounted for 18.6% of all civil servants in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Civil Service Bureau, 2020). In 2019–2020, approximately 90% of officers were at a junior level, such as junior constable, senior constable, sergeant, or station sergeant, while 10% were officers working at the inspectorate level or higher (Hong Kong Police Force, 2020). The police–citizen ratio of 390 to 100,000 population in Hong Kong has remained steady over the past decade (Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department, 2020) and is largely in line with the rate in major Western cities, such as 360 in Greater London (Allen & Zayed, 2020) and 398 in New York (US Census Bureau, 2020). In Hong Kong, high salaries and adequate welfare benefits have been used to discourage police officers’ involvement in corruption since the late 1970s.

Despite good pay and benefits, the Hong Kong Police Department has encountered difficulties in recruiting and detaining officers over the past year. Nearly 450 police officers left the force, and only 766 officers were hired between June 2019 and February 2020, compared with 1,341 in the previous year. The Security Bureau of Hong Kong said the reasons for leaving included resignation during training, early retirement, and family or personal reasons (Leung, 2020). Although no official statistics are available to support the role of work stress in officers’ early retirement decisions, their turnover intention has probably been motivated by the challenging working environment marked by social unrest, violence, and citizen resentment.

Hong Kong has recently experienced several waves of social unrest, including the Umbrella Movement in 2014, the Fishball Movement in 2016, and the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement in 2019. These movements, especially the most recent, have led to thousands of injuries and generated considerable resentment toward the police, particularly among young people. Public satisfaction with the Hong Kong police decreased from 69% in June 2010 to 50% in June 2019, and dissatisfaction rose from 13% to 28% during the same period (Public Opinion Program, The University of Hong Kong, 2019). Reduced satisfaction and increased dissatisfaction can result in resentment and violence. Reported cases of assault on the police increased from 448 in 2009 to 724 in 2019, despite a steady decrease in the crime rate from 1,113 (per 1,00,000 population) to 789 during the same period (Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department, 2020).

Consequent to the diminishing trust between the police and the public and the rising number of riots in recent years, Hong Kong’s public order policing style has shifted from “soft” to “coercive” (Ho, 2021). This coercive policing style has involved the increased use of arrests and beatings instead of negotiation and communication, which also imposes adverse working conditions on frontline police officers. The adverse working environment may have been exacerbated by the non-compliance of some citizens towards health protection measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Current Study

This study sought to gauge the views of frontline police officers regarding (a) their perceived work stress and turnover intention, (b) perceived work-to-family conflicts (WFCs) and family-to-work conflicts (FWCs), (c) supervisor support (SS), family support (FS), and constructive coping (CC). This study was designed to test the following six hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: Work stress and turnover intention vary across demographic backgrounds.

Hypothesis 2: Work stress is positively related to FWC and WFC (resource loss).

Hypothesis 3: Work stress is negatively related to SS, FS, and CC (resource gain).

Hypothesis 4: Turnover intention is positively related to FWC and WFC (resource loss).

Hypothesis 5: Turnover intention is negatively related to SS, FS, and CC (resource gain).

Hypothesis 6: Resource variables can moderate the effects of demand variables on work stress and turnover intention.

By testing these hypotheses, our study offers three potential contributions. First, this study extends the literature on police job stress and turnover intention to include Hong Kong. This city witnessed a noticeable decrease in rank on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (2020) Biennial Safe Cities Index, and police officers’ job demands became extraordinary during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study results may reveal implications and useful insights for other cities experiencing mass protests during the pandemic.

Second, our study adopted COR theory, and our findings demonstrate how well resource losses and gains across the workplace and family domains can affect work stress and turnover intention. To the best of our knowledge, this study offers the first empirical and theoretically driven analysis of the spillover effects of resources and demands on work stress (as a psychological response) and turnover intention (as a behavioral response) among a sample of police officers in Hong Kong. As a postcolonial society with a mixture of Chinese and Western cultures, the Hong Kong public (including police officers) expect the family–work interface to reflect traditional Chinese ideologies, such as the Confucian principles of interpersonal harmony and collectivism toward family unity (King & Bond, 1985), and a capitalist ideology that emphasizes individuals’ efforts toward career achievement. The median number of weekly working hours for employees was 44.3 in 2020 (Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department, 2020), which is higher than in most comparable cities. Hong Kong is an ideal research site to confirm the influence of the spillover effects of the family and workplace on work stress and turnover intention.

Third, our study may shed light on the directions of policies and practices intended to mitigate police work stress and turnover intention, especially during natural disasters. Our study results can confirm the extent of the negative impact of work–family conflict on work stress and turnover intention and whether FS, SS, and CC moderate this effect. If the negative impact of work–family conflict is unavoidable, police organizations can consider strengthening the resilience of officers and their family members or providing organizational support to counteract the consequences.

Methods

Data Collection and Sample

This study used part of the data collected by a multi-year research project that measured factors relating to officers’ work stress and turnover intention. The research project used an 80-item survey instrument that was developed and finalized in 2016 by a team of researchers after a pilot survey study, using the test–retest reliability method. The pilot survey was conducted among approximately 80 police officers to confirm the construct, convergent, and discriminant validities. The research team contacted the Junior Police Officers’ Association (JPOA) in Hong Kong to obtain permission to survey its members. JPOA is the union that represents almost all of the serving police constables, sergeants, and station sergeants, who account for approximately 90% of the total officer population in Hong Kong. As at 31 December 2019, there were 28,034 junior police officers (Hong Kong Police Force, 2020).

The study was conducted according to ethical protocols approved by the first author’s University. The survey was administered using a random sampling method based on a full list of JPOA members. Eight hundred targets were randomly selected in 2018. An invitation letter explaining the research objectives, confidentiality issues, and the voluntary nature of participation was sent to the targets. Informed consent was collected through a reply form attached to the invitation letter. Data were collected through a self-administered survey questionnaire distributed and gathered by JPOA and given to the research team during the early summers of 2018, 2019, and 2020. Our research team received all filled questionnaires before July. This survey study was conducted in a pencil-and-paper format, which was suggested by JPOA as a more feasible approach than an online one. We excluded questionnaires with inadequate responses in a three-wave study on the same group of officers. At the first wave of the study in 2018, we collected the valid response from 625 officers (78% response). The questionnaires were only sent to those who had participated in the previous wave (i.e., wave 1), resulting in a 72% response rate (N = 456) for wave 2 and 73% response rate (N = 335) for wave 3. The current study is based on the analysis of the valid responses in wave 3. The current study is based on the analysis of the valid responses in wave 3. The sample size of the current study adhered to the power analysis (see Cohen, 1988) for testing an effect (r > .15), with a p-value of .05 and a power of .80.

Considering the decrease of sample members between the waves can alter the original sample representativeness, our research team checked the possible attrition bias. Bivariate comparisons of stayers versus leavers on baseline data is one of the methods to detect attrition bias in a longitudinal study (Miller & Wright, 1995). In this study, an independent-sample t test was performed on key demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, education, marital status, having children or not, tenure, and rank) comparing those respondents who discontinued their participation after the first wave of data collection in 2018 (leavers, N = 301) to those who continued their participation till to the third wave of data collection in 2020 (stayers, N = 335). Almost all 2020 respondents attended all three waves of studies, except a few of them who missed the second wave data collection. Our analysis did not find any significant differences between the two groups at the .05 level (see Table 1). Hence the threat to sample representativeness due to attrition bias is not a concern in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Leavers and Stayers.

| Characteristics | Leavers (N = 301) |

Stayers (N = 335) |

|---|---|---|

| M | M | |

| Female (%) | 21.4 | 16.9 |

| Age (years) | 36.9 | 34.4 |

| Education (years) | 13.4 | 13.0 |

| Married (%) | 57.1 | 59.0 |

| Have children (%) | 57.1 | 37.4 |

| Tenure (years) | 13.9 | 11.5 |

| Rank | 16.7 | 11.5 |

Note. Leavers = those respondents who discontinued their participation after 2018, Stayers = those respondents who continued their participation till to 2020.

No significant differences between the two groups at the .05 level.

Dependent Variables

Two dependent variables, namely officer work stress and turnover intention, were examined in this study (Table 2). Eight items were originally used to measure officers’ work stress, consistent with the methods of a previous study (McCarty et al., 2007). After the pilot test, two items were dropped. We used a series of 6-point Likert items to ask the respondents how often they encountered certain situations, such as “I feel tired at work even with adequate sleep,” “I become moody, irritable, or impatient over small problems,” and “My interest in doing fun activities has decreased because of my work.” The response categories included “never,” “rarely,” “seldom,” “sometimes,” “frequently,” and “always” (scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively). The scale had a Cronbach’s α of .887, suggesting high internal reliability.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics, Factor Analysis, and Reliability Test Results.

| Scale and items | M | SD | Factor loadings | % of variance explained | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work stress (1 = never; 6 = always) | 40.0 | 18.7 | 64.3 | .887 | |

| 1. I feel tired at work, even with adequate sleep. | 50.3 | 24.9 | .836 | ||

| 2. I become moody, irritable, or impatient over small problems. | 37.6 | 21.1 | .784 | ||

| 3. I feel that work is futile. | 34.9 | 22.5 | .827 | ||

| 4. My resistance to illness is lowered because of my work. | 39.4 | 23.7 | .778 | ||

| 5. My interest in doing fun activities has lowered because of my work. | 44.8 | 26.3 | .791 | ||

| 6. I have difficulty concentrating on my job. | 33.2 | 21.8 | .794 | ||

| Turnover intention (1 = never; 6 = always) | 15.3 | 19.6 | 80.1 | .916 | |

| 1. Thinking about quitting. | 14.8 | 20.9 | .908 | ||

| 2. A desire to leave the current job. | 19.5 | 24.2 | .900 | ||

| 3. Searching for alternative employment or preparing for official examinations. | 13.4 | 20.2 | .892 | ||

| 4. Undecided about staying next year. | 13.2 | 21.9 | .881 | ||

| Work-to-family conflict (WFC; 1 = totally disagree; 6 = totally agree) | 52.7 | 22.3 | 76.8 | .923 | |

| 1. The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life. | 54.6 | 25.4 | .870 | ||

| 2. Because of my job, I can’t involve myself as much as I would like in maintaining close relations with my family or spouse/partner. | 53.5 | 24.8 | .912 | ||

| 3. Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my job puts on me. | 55.1 | 24.9 | .902 | ||

| 4. I often have to miss important family activities because of my job. | 54.8 | 25.7 | .884 | ||

| 5. There is a conflict between my job and the commitments and responsibilities I have to my family or spouse/partner. | 45.8 | 27.0 | .810 | ||

| Family-to-work conflict (FWC; 1 = totally disagree; 6 = totally agree) | 28.7 | 20.5 | 74.2 | .911 | |

| 1. The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities. | 35.4 | 24.2 | .775 | ||

| 2. I sometimes have to miss work so that family responsibilities are met. | 28.5 | 25.2 | .862 | ||

| 3. Things I want to do at work don’t get done because of the demands of my family or spouse/partner. | 28.1 | 22.3 | .912 | ||

| 4. My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work, such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime. | 27.8 | 24.7 | .892 | ||

| 5. My co-workers and peers dislike how often I am preoccupied with my family life. | 23.5 | 22.8 | .859 | ||

| Supervisory support (SS; 1 = absolutely no support; 6 = enormous support) | 65.6 | 20.8 | 92.6 | .960 | |

| 1. Your leader backs you up when you have difficulties in combining work and family. | 66.6 | 21.1 | .963 | ||

| 2. Your leader listens to you when you face difficulties in combining work and family. | 66.0 | 21.3 | .961 | ||

| 3. Your leader helps you face difficulties in combining work and family. | 64.2 | 22.4 | .963 | ||

| Family support (FS; 1 = absolutely no support; 6 = enormous support) | 72.1 | 21.1 | 91.5 | .953 | |

| 1. Your spouse/family backs you up when you have difficulties in combining work and family. | 72.1 | 21.3 | .950 | ||

| 2. Your spouse/family listens to you when you face difficulties in combining work and family. | 72.5 | 22.2 | .963 | ||

| 3. Your spouse/family helps you face difficulties in combining work and family. | 71.7 | 22.8 | .956 | ||

| Constructive coping (CC; 1 = never; 6 = always) | 44.9 | 16.1 | 44.8 | .689 | |

| 1. Talk with your spouse, relative, or friend about the problem. | 54.8 | 21.6 | .685 | ||

| 2. Pray for guidance and strength. | 25.9 | 26.9 | .738 | ||

| 3. Make a plan of action and follow it. | 55.7 | 22.2 | .644 | ||

| 4. Exercise regularly. | 63.3 | 22.1 | .501 | ||

| 5. Rely on your faith in God to see you through this rough time. | 24.8 | 27.0 | .749 |

Note. N = 335. The values of the responses to the variables were converted from 1–6 to 0–100 for data comparison (0 = 1st point, 20 = 2nd point, 40 = 3rd point, 60 = 4th point, 80 = 5th point, and 100 = 6th point).

The second dependent variable in this study was turnover intention, which was gauged using four items with high reliability (α = .916). This scale was adopted from Lai (2017) and was used to assess turnover intent among correctional officers in Taiwan. We asked the respondents to rate the frequency of the following thoughts or actions: “thinking about quitting,” “a desire to leave the current job,” and “searching for alternative employment or preparing for official examination” on a 6-point Likert scale. The response categories included “never,” “rarely,” “seldom,” “sometimes,” “frequently,” and “always” (scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively).

In this study, we performed an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation to check the variability among observed variables and used the variance of inflation factor (VIF) scores for checking the problem of multicollinearity (Table 3). VIF ranged from 1.01 to 6.91was lower than the threshold of 10 (Hair et al., 1995). Multicollinearity was not a concern.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions Predicting Stress and Turnover Intention and Moderating Effects Among Predictors.

| Stress |

Turnover intention |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | R² | β | R² | VIF |

| Step 1 (demographics) | .008 | .028 | |||

| Female | −.031 | −.103 | 1.05 | ||

| Age | .061 | −.085 | 6.91 | ||

| Education | .007 | .058 | 1.20 | ||

| Married | −.015 | −.124 | 2.01 | ||

| Have children | −.054 | .012 | 1.85 | ||

| Tenure | −.039 | .119 | 7.49 | ||

| Rank | −.050 | −.065 | 2.03 | ||

| Step 2 (resource loss & gain) | .443 | .205 | |||

| WFC | .443*** | .143* | 1.34 | ||

| FWC | .305*** | .167* | 1.42 | ||

| SS | −.084 | −.236*** | 1.35 | ||

| FS | .009 | −.047 | 1.36 | ||

| CC | −.015 | .074 | 1.06 | ||

| Step 3 (moderation) | .454 | .269 | |||

| WFC × SS | −.006 | −.176** | 1.05 | ||

| WFC × FS | .039 | −.061 | 1.01 | ||

| WFC × CC | .067 | −.022 | 1.01 | ||

| FWC × SS | .041 | .025 | 1.02 | ||

| FWC × FS | −.029 | −.104 | 1.04 | ||

| FWC × CC | .000 | .077 | 1.02 | ||

Note. N = 335. VIF = the variance inflation factor scores, WFC = Work-to-family conflict, FWC = Family-to-work conflict, SS = Supervisor support, FS = Family support, CC = Constructive coping.

Each interaction is added alternately.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Independent Variables

The independent variables were constructed based on the key concepts of COR: (a) resource loss because of family and workplace demands, which include work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict, and (b) resources gain from family support, supervisor support, and constructive coping for managing demands.

Work-to-family Conflict (WFC). WFC was measured using a 5-item additive variable developed by Howard et al. (2004), which was scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “totally disagree” to 6 = “totally agree”). This scale has one dimension, and the sample items include “I often have to miss important family activities because of my job” and “There is a conflict between my job and the commitments and responsibilities I have to my family or spouse/partner.” A Cronbach’s α of .923 reveals a high level of internal reliability.

Family-to-work Conflict (FWC). FWC was also adapted from the scale developed by Howard et al. (2004). The sample questions include “The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities” and “Things I want to do at work don’t get done because of the demands of my family or spouse/partner.” The respondents were asked to use a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 6 = “totally agree.” The FWC scale has a Cronbach’s α of .911.

Supervisor Support (SS). The SS scale consists of three items (α = .960; Nohe & Sonntag, 2014). The respondents offered answers based on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “absolutely no support” (=1) to “enormous support” (=6). The question items include “To what extent can you count on your leader to listen to you when you face difficulties in combining work and family?” and “To what extent can you count on your leader to help you face difficulties in combining work and family?”

Family Support (FS). The FS scale was also adopted from Nohe and Sonntag (2014). Three items were used (α = .953), and sample items include “To what extent can you count on your spouse to back you up when you have difficulties in combining work and family?” and “To what extent can you count on your spouse to listen to you when you face difficulties in combining work and family?”

Constructive Coping (CC). CC strategies were measured using five items (α = .689) that were adopted from He et al. (2002). The respondents in the current study were asked to indicate the frequency at which they adopted certain strategies, such as “praying for guidance and strength” and “exercising regularly.” A 6-point Likert scale ranging from “never” (=1) to “always” (=6) was used.

In this study, the values of the responses to the variables were converted from 1–6 to 0–100 for the ease of data comparison (0 = 1st point, 20 = 2nd point, 40 = 3rd point, 60 = 4th point, 80 = 5th point, and 100 = 6th point). This linear rescaling resulted in no variations in the meanings and relationships concerning the measures (Preston & Colman, 2000).

Demographic and Control Variables

Demographic characteristics were used as control variables (Table 1). They included gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age (in years), education (in years), marital status (0 = not married; 1 = married), parenthood (0 = not a parent, 1= parent), tenure (in years), and rank (1 = junior police constable, 2 = senior police constable, 3 = sergeant, 4 = station sergeant). The mean age of the respondents was 34 years, and 16.9% were female. The gender ratio is similar to that of the overall police population in Hong Kong in 2019–2020, in which female police officers accounted for 17.5% of the force (Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department, 2020). On average, the respondents had 13 years of education, the equivalent of a high school diploma. More than half of the respondents were married (59%), and more than a third (37.4%) had children. The respondents had an average of 11.5 years of service experience. Regarding rank, 77.7% were junior constables, 10.7% were senior constables, 10.7% were sergeants, and 0.9% were station sergeants. This rank structure largely resembles that of the current police population. As of December 31, 2019, 76% of junior police officers were police constables, while 19% were sergeants and 5% were station sergeants (Hong Kong Police Force, 2020).

Results

Univariate Analysis

The descriptive data for work stress and turnover intention are shown in Table 2. Splitting the scores ranging from 0 to 100 into tertiles (i.e. lower scores = less than 40; medium scores = 40–60; higher scores = more than 60), the police officers in this study were found to encounter medium levels of work stress (M = 40.0, SD = 18.7) and exhibit lower levels of turnover intention (M = 15.3, SD = 19.6). The police officers “sometimes” felt work stress and “rarely” had turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were confronted by a medium level of WFC (M = 52.7, SD = 22.3) and a lower level of FWC (M = 28.7, SD = 20.5). However, they reported that they had received substantial support to handle their stress from their supervisors (M = 65.6, SD = 20.8) and spouses/families (M = 72.1, SD = 21.1). The use of constructive coping strategies to manage work stress was not very frequent among police officers in this study (M = 44.9, SD =16.1).

Multivariate Analysis

Hierarchical multiple regressions (Table 3) were used to assess the effects of different sets of variables based on the theoretical framework of this study. Step 1 examined the effects of the participating police officers’ background characteristics on their occupational stress and work turnover intention. In Step 2, the two variables of WFC and FWC were added. In Step 3, the support and coping variables (SS, FS, and CC) were added. In the final step, the interaction effects of the five independent variables were added. We examined the interaction terms individually so as to eliminate the overlapping interaction effect problem. For the sake of interpretability of results, we did the mean centering of the moderating and independent variables prior to computing the interaction terms.

Demographic variables only accounted for less than 1% and 2% of the variation in the participants’ work stress and turnover intention, respectively. None of the demographic variables had a significant impact on the two outcome variables of the study. Hence, hypothesis 1 was not supported in this study. Adding the five explanatory variables into the regression (step 2) greatly improved the explanatory power of work stress and turnover intention, increasing the R2 values from .008 to .443 and from .028 to .205, respectively. The results indicate that police work stress is significantly related to WFC (β = .443, p < .001) and FWC (β = .305, p < .001) but not to SS, FS, and CC. Moreover, the officers’ intention to quit is related to WFC (β = .143, p < .05), FWC (β = .167, p < .05), and SS (β = −.236, p < .001) but not to FS and CC. Therefore, hypotheses 2, 4, and 5 were confirmed, whereas hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

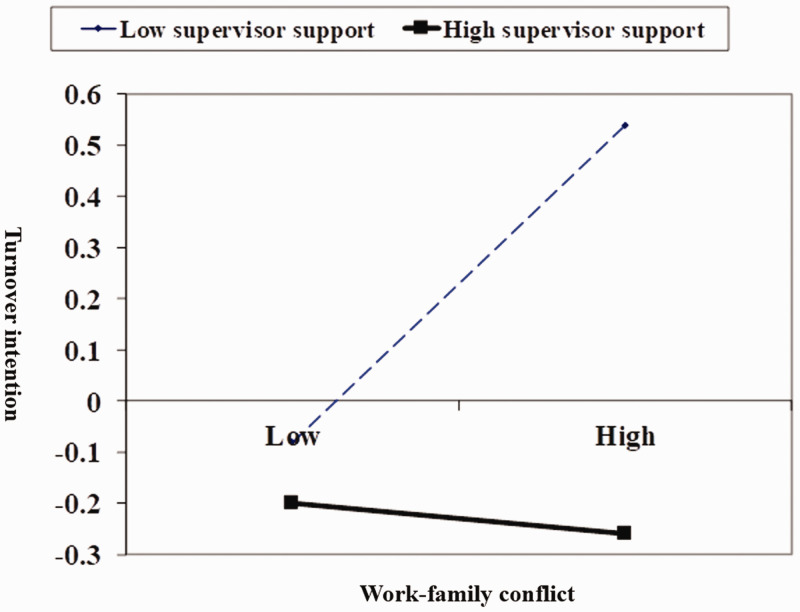

The moderation effect exists in explaining turnover intention (Step 3). SS can moderate the impact of work–family conflict on turnover intention (β = −.176, p < .01). When the moderating effect was added, the R2 increased from .443 to .454 to explain work stress and from .205 to .269 to account for turnover intention. Hypothesis 6 was partially supported. Figure 1 shows the standard scores of turnover intention by high and low levels of work–family conflict and supervisor support. A positive relationship between work–family conflict and turnover intention was noted under the condition of low supervisor support, while a negative relationship was noted under the condition of high supervisor support. All explanatory variables together accounted for more than 45% of the variation in work stress and more than 26% of the variation in turnover intention among police officers in this study.

Figure 1.

Standard Score of Turnover Intention by High (1 SD Above M) and Low Levels (1 SD Below M) of Work–Family Conflict and Supervisor Support.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study is one of the first to examine the effects of COR variables on work stress and turnover intention among police officers in Hong Kong amid a pandemic. The findings have important research and practical implications.

First, compared with the data collected from another group of police officers in Hong Kong in 2017 by our research team, the police officers in this study appeared to have encountered less work stress but a similar level of conflict between their work and families. In 2017, the mean scores were 50 for work stress, 58.2 for WFC, and 33.3 for FWC (Li et al., 2019). There are three possible explanations for this finding. First, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were fewer mass demonstrations due to health concerns and restrictions on group gatherings. Hong Kong police officers were released from the burden of handling riots and conflicts in public places. Second, the results may be related to the issue of “survival bias” that has been shown in previous police stress studies (Gershon et al., 2009). Our study did not include officers who went into early retirement or were on sick leave due to work stress over the past 2 years. Third, the stress tolerance or resiliency of Hong Kong police officers may have increased alongside their exposure to riots and mass protests.

Second, the study findings enrich our understanding of resource losses and gains across two key life domains, family and work. The two full models explained approximately 45% of the variance in work stress and 26% of the turnover intention among police officers. Our findings suggest that COR theory is well suited to recognize the factors involved in police occupational stress and turnover intention in Hong Kong.

Among the explanatory variables, FWC (e.g., missing work due to family responsibilities) and WFC (e.g., missing important family activities due to work) exert significant effects on work stress. These results indicate that police officers are likely to feel psychological distress when conflicts with family members spread to the workplace, which will substantially affect their resources. Support from family members and supervisors and positive coping mechanisms did not demonstrate any effect on work stress. These findings contradict the conclusions of previous studies that SS (Ellrich, 2016; Ganster et al., 1986), FS (Aryee et al., 1999; Shim et al., 2015), and CC (Clark-Miller & Brady, 2013) can alleviate or moderate work stress directly. The resources that the participants may have derived from personal coping mechanisms and support from their families or workplaces may not have played a role in work stress mitigation due to the drastic changes in their work environment and demands amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

WFC and FWC also significantly influence job turnover intention. Police officers with FWC may realize that they need to withdraw from the current situation to avoid a further loss of resources, such as time and affection shared with loved ones. This realization echoes Hobföll’s (2001) proposition that individuals strive to protect things that they value. SS has a negative impact and moderates the effect of WFC on officers’ turnover intention. This finding suggests that SS, in the form of listening and offering help, can drastically reduce a subordinate’s intention to quit their job and offset the negative impact of WFC and FWC on turnover intention.

Third, none of the demographic variables in this study (including gender, age, education, marital status, parenthood, years of service, and rank), were found to be significantly correlated with work stress and turnover intention. Therefore, it would seem that the impact of the explanatory variables (work–family conflict, social support, and constructive coping) on the outcome variables (work stress and turnover intention) is free from interference of the respondents’ backgrounds. This provides additional evidence that work resources and demands are more potent than demographics.

Finally, it is imperative to design and implement policies and practices to reduce police work stress and turnover intention amid and after a pandemic. We found that WFCs and FWCs are salient variables affecting work stress and turnover intention among Hong Kong officers. Promoting a family-friendly policy in the workplace is important during the COVID-19 pandemic. Extra energy is required to take care of children who cannot attend school and address the concerns of family members regarding safety and health. In line with family-friendly policies for civil servants (including the police), the Hong Kong government extended paid maternity leave for employees from 10 to 14 weeks in 2018. This action is a good move, although it lags behind standards in Europe; for example, the U.K. offers 39 weeks. In the context of COVID-19, the Hong Kong government should also consider flexible work arrangements (e.g., long-term leave with employment protection and temporary remote work for caring purposes) and childcare options (e.g., emergency childcare and extra support for pregnant employees: United Nations Children’s Fund et al., 2020).

At the organizational level, it is essential to cultivate a supportive workplace environment. This study indicates that SS can moderate the impact of work–family conflicts on work stress. Police organizations should offer support that is tangible (i.e., assistance with resources, time, and labor), informational (i.e., advice or information on community assistance), and emotional (i.e., care, concern, and listening; Youngcourt & Huffman, 2005). Practical suggestions include offering police officers priority access to COVID-19 vaccines to enhance their sense of safety from infection (De Camargo, 2021), and shifting non-core policing duties to the community and commercial sector, such as volunteers and security staff, to alleviate work overload during the pandemic (Jiang & Xie, 2021).

Several limitations of this study should be noted when interpreting the findings. First, the cross-sectional design makes it difficult to confirm causal relationships between the variables. For instance, although the study findings indicated that work–family conflicts had a significant effect on police work stress and turnover intention, these variables are reciprocally related, and the direction of influence remains uncertain. Second, although the study was conducted based on a random sample and the same group of officers was invited to take part in the study’s three waves in 2018, 2019, and 2020, the representativeness of the sample was threatened by the attrition rate of each cohort. The responses of officers who retired, resigned, or declined to answer were not included. Third, the categorization of work–family conflicts in this study is limited to two types, namely WFCs and FWCs, which may not adequately reflect all of the types of stress that officers experience. Future studies should consider examining other forms of work–family conflicts, such as those based on time, roles, and stress. Fourth, social desirability concerns may have biased the respondents’ answers in this study. Social desirability bias occurs when respondents over-report admirable attitudes and/or behaviors to present themselves favorably with respect to current social norms and standards, and under-report attitudes and behaviors that they feel are not socially acceptable or respectable (Zerbe & Paulhus, 1987). The respondents in this study may have under-reported their stress levels to present a strong, tough self-image. To eliminate personal bias, further conclusions could be generated based on multiple sources of information. Future studies could collect data on partners’ and children’s perceptions and experiences of stress.

Author Biographies

Jessica C. M. Li, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests are in the fields of police stress, commercial sex exploitation and situational crime prevention. Her recent published articles were included in Journal of Interpersonal Violence, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, and Psychology, Law & Crime (email: cmj.li@polyu.edu.hk).

Chau-kiu Cheung, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences at the City University of Hong Kong. He has recently published articles concerning civility, social inclusion, resilience, character education, moral development, peer influence, and class mobility. His current research addresses issues of grandparenting, drug abuse, risk society, and Internet use through Child Indicator Research, Children and Youth Service Review, and the Social Science Journal.

Ivan Y. Sun, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the University of Delaware. His research interests include police attitudes and behavior, public opinion on legal authorities, and crime and justice in Asian societies. His recent publications on police have appeared in the Police Quarterly, Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, and British Journal of Criminology.

Yuen-kiu Cheung, is a PhD student in the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Shimin Zhu, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests cover mental health, stress, and wellbeing. Her recent publications have appeared in Health Psychology and Behavioural Medicine, Frontiers in Psychology, and Occupational Medicine.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jessica C. M. Li https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5589-4986

Chau-kiu Cheung https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3278-1633

Ivan Y. Sun https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5679-196X

References

- Acquadro Maran D. A., Varetto A., Zedda M., Franscini M. (2014). Stress among italian male and female patrol police officers: A quali-quantitative survey. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 37(4), 875–890. 10.1108/pijpsm-05-2014-0056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G., Zayed Y. (2020). Police service strength. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn00634/ [Google Scholar]

- Anshel M. H. (2000). A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 27(3), 375–400. 10.1177/0093854800027003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S., Fields D., Luk V. (1999). A cross-cultural test of a model of the work–family interface. Journal of Management, 25(4), 491–511. 10.1177/014920639902500402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishopp S. A., Piquero N. L., Worrall J. L., Piquero A. R. (2018). Negative affective responses to stress among urban police officers: A general strain theory approach. Deviant Behavior, 40(6), 1–20. 10.1080/01639625.2018.1438069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. M., Campbell E. A. (1994). Stress and policing: Sources and strategies. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Kruis N. E., Yun I. (2020). When do police stressors particularly predict organizational commitment? The moderating role of social resources. Police Quarterly, 23(4), 527–546. 10.1177/1098611120923153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Miller J., Brady H. C. (2013). Critical stress: Police officer religiosity and coping with critical stress incidents. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 28(1), 26–34. 10.1007/s11896-012-9112-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina J. M., Doherty M. L., Schmitt N., Kaufman G., Smith R. G. (1992). The “big five” personality factors in the IPA and MMPI: Predictors of police performance. Personnel Psychology, 45(1), 119–140. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1992.tb00847.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen F. T., Lemming T., Link B. G., Wozniak J. F. (1985). The impact of social supports on police stress. Criminology, 23(3), 503–522. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1985.tb00351.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Camargo C. (2021). It’s tough shit, basically, that you’re all gonna get it’: UK virus testing and police officer anxieties of contracting COVID-19. Policing & Society, 10.1080/10439463.2021.1883609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner W. G. (1995). Officer retention patterns: An affirmative action concern for police agencies? American Journal of Police, 14(3/4), 197–210. 10.1108/07358549510112018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2020). Safe cities index 2019. https://safecities.economist.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Aug-5-ENG-NEC-Safe-Cities-2019-270x210-19-screen.pdf

- Ellrich K. (2016). The influence of violent victimisation on police officers’ organizational commitment. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 31(2), 96–107. 10.1007/s11896-015-9173-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding N. (1988). Joining forces: Police training socialization and occupational competence. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel M. O., Giessing L., Egger-Lampl S., Hutter V., Oudejans R. R., Kleygrewe L., Jaspaert E., Plessner H. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on European police officers: Stress, demands, and coping resources. Journal of Criminal Justice, 72, 101756. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugitive offenders ordinance Cap. 503, Laws of Hong Kong (2017). https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap503

- Ganster, D. C., Fusilier, M. R., & Mayes, B. T. (1986). Role of social support in the experience of stress at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(1), 102–110. 10.1037/0021-9010.71.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon B. R. M., Barocas B., Canton A. N., Li X., Vlahov D. (2009). Mental, physical, and behavioural outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers. Criminal Justice & Behaviour, 36(3), 275–289. 10.1177/0093854808330015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z., Yang J., Gilal F. G., Van Swol L. M., Yin K. (2020). Repairing police psychological safety: The role of career adaptability, feedback environment, and goal- self concordance based on the conservation of resources theory. Sage Open, 10(2), 215824402091951–215824402091911. 10.1177/2158244020919510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. M. (1990). A model for police officer burnout. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5(1), 85–99. 10.1007/bf01013947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). The conservation of resources model applied to work“Cfamily conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 350--370. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0001879198916669 [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus J. H., Beutell N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. 10.5465/amr.1985.4277352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J. D., Sun I. Y. (2018). Do work–family conflict and resiliency mediate police stress and burnout? A study of state police officers. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(2), 354–370. 10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson G. H., Adlam K. R. C. (1985). Occupational stressors among British police officers. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 58(1), 73–80. 10.1177/0032258x8505800110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haarr R. N. (2005). Factors affecting the decision of police recruits to “drop out” of police work. Police Quarterly, 8(4), 431–453. 10.1177/1098611103261821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J. F., Jr., Anderson R. E., Tatham R. L., Black W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis (3rd ed.). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J. R. B., Neveu J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl S. C., Westman M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. 10.1177/0149206314527130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G. B., Dollard M. F., Tuckey M. R., Winefield A. H., Thompson B. M. (2010). Job demands, work–family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in police officers: A longitudinal test of competing theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 237–250. 10.1348/096317908x401723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. M., Baldwin J. N. (1999). Voluntary turnover of field operations officers: A test of confluency theory. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(6), 483–493. 10.1016/s0047-2352(99)00019-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He G., An R., Zhang F. (2019). Cultural intelligence and work–family conflict: A moderated mediation model based on conservation of resources theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2406. 10.3390/ijerph16132406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He N., Zhao J., Archbold A. (2002). Gender and police stress: The convergent and divergent impact of work environment, work–family conflict, and stress coping mechanisms of female and male police officers. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25(4), 687–708. 10.1108/13639510210450631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He N., Zhao J., Ren L. (2005). Do race and gender matter in police stress? A preliminary assessment of the interactive effects. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(6), 535–547. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L. (2021). A government–society confrontation. Interventions, 23(4), 481–505. 10.1080/1369801X.2020.1784025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobföll S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. 10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobföll S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nest-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. 10.1111/1464-0597.00062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Census & Statistics Department. (2020). Hong Kong annual digest of statistics 2020. https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10100032020AN20B0100.pdf

- Hong Kong Civil Service Bureau. (2020). Strength of the civil service (June 30, 2020). https://www.csb.gov.hk/english/stat/quarterly/541.html

- Hong Kong Government. (2020). Latest situation of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Hong Kong.https://chp-dashboard.geodata.gov.hk/covid-19/zh.html

- Hong Kong Police Force. (2020). 2019 Hong Kong police review. https://www.police.gov.hk/info/doc/review/review_2019_tc.pdf

- Howard W. G., Donofrio H., Boles J. S. (2004). Inter‐domain work–family, family–work conflict and police work satisfaction. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 27(3), 380–395. 10.1108/13639510410553121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Xie C. (2021). Roles of Chinese police amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(4), 1127–1137. https://academic.oup.com/policing/article/14/4/1127/6054277 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. B., Todd M., Subramanian G. (2005). Violence in police families: Work–family spillover. Journal of Family Violence, 20(1), 3–12. 10.1007/s10896-005-1504-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalliath P., Kalliath T. (2014). Work–family conflict: Coping strategies adopted by social workers. Journal of Social Work Practice, 28(1), 111–126. 10.1080/02650533.2013.828278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King A. Y. C., Bond M. H. (1985). The Confucian paradigm of man: A sociological view. In Tseng W. S., Wu D. Y. (Eds.), Chinese culture and mental health (pp. 29–46). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S.-Y. (2015). Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and affective commitment to policing among Taiwanese police officers. Police Quarterly, 18(1), 27–54. 10.1177/1098611114559039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y.-L. (2017). The impact of individual and institutional factors on turnover intent among taiwanese correctional staff. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(1), 100–121. 10.1177/0306624x15589099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert E. (2006). I want to leave: A test of a model of turnover intent among correctional staff. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 2(1), 57–83. http://dev.cjcenter.org/_files/apcj/2_1_turnover.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. (2020, April 8). Nearly 450 Hong Kong police officers quit unexpectedly amid last year’s anti-government protests, security bureau says. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3079045/nearly-450-hong-kong-police-officers-quit-unexpectedly [Google Scholar]

- Li J. C. M., Cheung C. K., Sun I. Y. (2019). The impact of job and family factors on work stress and engagement among Hong Kong police officers. Policing: An International Journal, 42(2), 284–300. 10.1108/PIJPSM-01-2018-0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C. (2020. a, April 6). Coronavirus: Six fined in Hong Kong’s first Covid-10 prosecutions for illegal public gathering. South China Morning Post.https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3078646/coronavirus-six-fined-hong-kongs-first-covid-19

- Lo C. (2020. b, April 21). Coronavirus: Hong Kong police hand out HK$66,000 in fines after breaking up largest illegal gathering since social-distancing laws took effect. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3080844/coronavirus-hong-kong-police-hand-out-hk66000 [Google Scholar]

- Lo S. S.-H. (2012). The changing context and content of policing in China and Hong Kong: Policy transfer and modernisation. Policing and Society, 22(2), 185–203. 10.1080/10439463.2011.605129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow I., Hong J. (2020. a, May 11). Hong Kong police arrest protesters for violating social distancing guidelines. Time. https://time.com/5835103/hong-kong-protesters-coronavirus-restrictions/

- Marlow I., Hong J. (2020. b, May 12). Hong Kong uses coronavirus rules to stop protests even as bars fill up. The Japan Times.https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/12/asia-pacific/hong-kong-coronavirus-protests/

- McCarty W. P., Zhao J., Garland B. E. (2007). Occupational stress and burnout between male and female police officers. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30(4), 672–691. 10.1108/13639510710833938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen A., Burke R. J. (2004). Work–family concerns of Norwegian police officers: Antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Stress Management, 11(4), 429–444. 10.1037/1072-5245.11.4.429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. B., Wright D. W. (1995). Detecting and correcting attrition bias in longitudinal family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(4), 921–929. https://www.jstor.org/stable/353412 [Google Scholar]

- Mowday R. T., Koberg C. S., McArthur A. W. (1984). The psychology of the withdrawal process: A cross-validation test of Mobley’s intermediate linkages model of turnover in two samples. Academy of Management Journal, 27(1), 79–94. 10.5465/255958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer R. G., Boles J. S., McMurrian R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410. 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nohe, C., & Sonntag (2014). Work-family conflict, social support, and turnover intentions: a longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 85(1), 1–12. 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preston C. C., Colman A. M. (2000). Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica, 104(1), 1–15. 10.1016/s0001-6918(99)00050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance: Compulsory quarantine of persons arriving at Hong Kong from foreign places regulation, Cap.599E, Laws of Hong Kong (2021a). https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap599E

- Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance: Compulsory quarantine and certain persons arriving at Hong Kong regulation, Cap. 599C, Laws of Hong Kong (2021b). https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap599C

- Prevention and Control of Disease (prohibition of group gathering) Regulation, Cap. 599G, Laws of Hong Kong (2021c). https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap599G!en?INDEX_CS=N

- Public Opinion Program, The University of Hong Kong. (2019). HKU POP final release: Popularity of police force drops to new low in recent years. https://www.hkupop.hku.hk/english/release/release1592.html

- Qureshi H., Lambert E. G., Keena L. D., Frank J. (2016). Exploring the association between organizational structure variables and work on family strain among Indian police officers. Criminal Justice Studies, 29(3), 253–271. 10.1080/1478601x.2016.1167054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Research Office, Legislative Council Secretariat. (2020). Statistical highlights. https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1920issh21-family-friendly-policies-for-civil-servants-20200305-e.pdf

- Saleem S., Yusaf S., Sarwar N., Raziq M. M., Malik O. F. (2021). Linking abusive supervision to psychological distress and turnover intention among police personnel: The moderating role of continuance commitment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9-10), 4451–4471. August 10.1177/0886260518791592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholarios D., Hesselgreaves H., Pratt R. (2017). Unpredictable working time, well-being and health in the police service. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(16), 2275–2298. 10.1080/09585192.2017.1314314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shim H. S., Jo Y., Hoover L. T. (2015). A test of general strain theory on police officers’ turnover intention. Asian Journal of Criminology, 10(1), 43–62. 10.1007/s11417-015-9208-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siu O., Cheung F., Lui S. (2015). Linking positive emotions to work well-being and turnover intention among Hong Kong police officers: The role of psychological capital. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 367–380. 10.1007/s10902-014-9513-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. D., Boan D., Aten J. D., Davis E. B., Van Grinsven L., Liu T., Worthington E. L., Jr., (2020). Resource loss and stress outcomes in a setting of chronic conflict: The conservation of resources theory in the Eastern Congo. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(3), 227–237. 10.1002/jts.22448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun I. Y., Liu J., Farmer A. K. (2016). Chinese police supervisors’ occupational attitudes. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 39(1), 190–205. 10.1108/pijpsm-04-2015-0048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stogner J., Miller B. L., McLean K. (2020). Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 718–730. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12103-020-09548-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund, International Labour Organization, & United Nations Women. (2020). Family-friendly policies and other good workplace practices in the context of Covid-19: Key steps employers can take.https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-gender/documents/publication/wcms_740831.pdf

- US Census Bureau. (2020). The rate of state and local police officers in the United States in 2019, by state (per 10,000 population).https://www.statista.com/statistics/302435/us-rate-of-state-and-local-police-officers

- Wickramasinghe N. D., Wijesinghe P. R. (2018). Burnout subtypes and associated factors among police officers in Sri Lanka: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 58, 192–198. 10.1016/j.jflm.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter C., Santa Maria A., Gusy B., Lesener T., Kleiber D., Renneberg B. (2019). Social support and work engagement in police work: The mediating role of work–privacy conflict and self-efficacy. Policing: An International Journal, 42(6), 1022–1037. 10.1108/pijpsm-10-2018-0154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y. S., Kwok K. O., Chan K. L. (2020). What can countries learn from Hong Kong’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(19), E511–E515. 10.1503/cmaj.200563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2020). Stress at the workplace. https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2021). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19).https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- Youngcourt S. S., Huffman A. H. (2005). Family-friendly policies in the police: Implications for work–family conflict. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 1(2), 138–162. http://dev.cjcenter.org/_files/apcj/1_2_policies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Zhu L., Chen F., Cheng Q., Yang Q., Zhou Z. Z., Zhu Y., Wu Y., Zhou Y., Zha X. (2020). A survey of psychological responses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic among Chinese police officers in Wuhu. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 2689–2697. https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/survey-psychological-responses-during-coronavirus/docview/2470804256/se-2?accountid=201395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbe, W. J., & Paulhus, D. L. (1987). Socially desirable responding in organizational behavior: A reconception. The Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 50--64. 10.2307/258533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., He N., Lovrich N. (2002). Predicting five dimensions of police officer stress: Looking more deeply into organizational settings for sources of police stress. Police Quarterly, 5(1), 43–62. 10.1177/109861110200500103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]