Abstract

Objective

To develop a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions.

Design

Development of the preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR) statement.

Participants

Core team (seven individuals) led day-to-day operations, and an expert advisory group (three individuals) provided methodological advice. A panel of 100 experts (authors, editors, readers including members of the public or patients) was invited to participate in a modified Delphi exercise. 11 expert panellists (chosen on the basis of expertise, and representing relevant stakeholder groups) were invited to take part in a virtual face-to-face meeting to reach agreement (≥70%) on final checklist items. 21 authors of recently published overviews were invited to pilot test the checklist.

Setting

International consensus.

Intervention

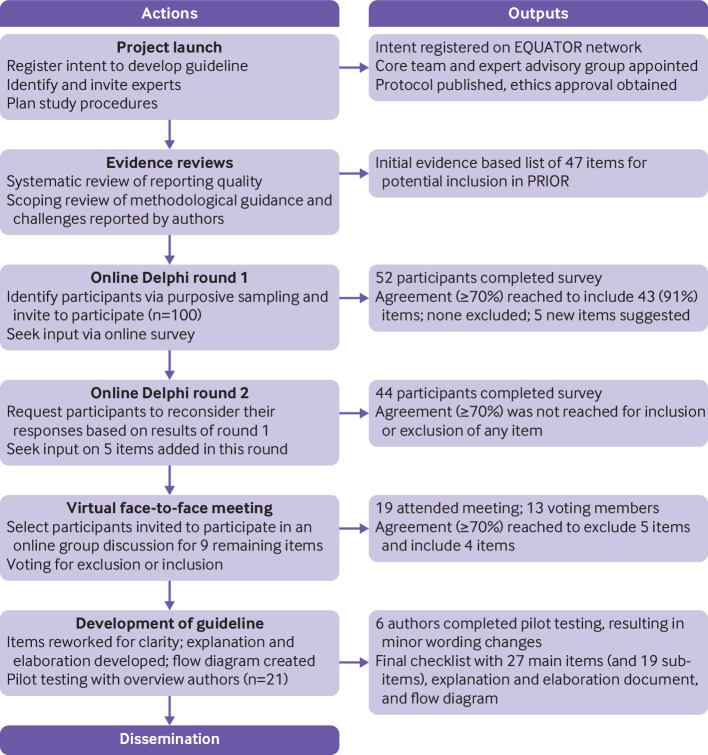

Four stage process established by the EQUATOR Network for developing reporting guidelines in health research: project launch (establish a core team and expert advisory group, register intent), evidence reviews (systematic review of published overviews to describe reporting quality, scoping review of methodological guidance and author reported challenges related to undertaking overviews of reviews), modified Delphi exercise (two online Delphi surveys to reach agreement (≥70%) on relevant reporting items followed by a virtual face-to-face meeting), and development of the reporting guideline.

Results

From the evidence reviews, we drafted an initial list of 47 potentially relevant reporting items. An international group of 52 experts participated in the first Delphi survey (52% participation rate); agreement was reached for inclusion of 43 (91%) items. 44 experts (85% retention rate) completed the second Delphi survey, which included the four items lacking agreement from the first survey and five new items based on respondent comments. During the second round, agreement was not reached for the inclusion or exclusion of the nine remaining items. 19 individuals (6 core team and 3 expert advisory group members, and 10 expert panellists) attended the virtual face-to-face meeting. Among the nine items discussed, high agreement was reached for the inclusion of three and exclusion of six. Six authors participated in pilot testing, resulting in minor wording changes. The final checklist includes 27 main items (with 19 sub-items) across all stages of an overview of reviews.

Conclusions

PRIOR fills an important gap in reporting guidance for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. The checklist, along with rationale and example for each item, provides guidance for authors that will facilitate complete and transparent reporting. This will allow readers to assess the methods used in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions and understand the trustworthiness and applicability of their findings.

Introduction

Decision makers (patient partners, healthcare providers, policy makers) rely on well conducted and reported systematic reviews and meta-analyses to inform evidence based healthcare.1 The publication of systematic reviews has rapidly increased in recent decades, such that in 2019, more than 80 systematic reviews were published daily.2 In some topic areas, this proliferation of systematic reviews has even outpaced the publication of randomised controlled trials.3 Identifying and interpreting evidence from the growing number of sometimes redundant, misleading, or conflicting syntheses is an onerous task,4 and is compounded by their variable methodological conduct (ie, rigor with which they are undertaken) and reporting quality (ie, complete and transparent reporting).5 6 A newer form of evidence synthesis, the overview of reviews (sometimes known as an overview, overview of systematic reviews, review of reviews, review of systematic reviews, or umbrella review, among others),7 8 9 10 aims in part to address this challenge by collating, assessing, and synthesising evidence from multiple systematic reviews on a specific topic.10 11 12 In some cases, overviews of reviews might also incorporate evidence from supplemental primary studies, for example, when existing systematic reviews are incomplete or out of date.

Within the past two decades, the publication of overviews of reviews has increased exponentially.7 8 9 13 In a recent survey, Bougioukas et al identified 1558 overviews of reviews published in English between 2000 and 2020, with 57% (n=882) being published in the most recent four years (2017-20).8 Along with their growing popularity as a publication type, guidance for the conduct of overviews of reviews has become abundant.14 15 16 Although many of the methods used to undertake systematic reviews are suitable for overviews of reviews, they also present unique methodological challenges.11 15 16 17 New methodological guidance published in recent years has helped to resolve some common challenges (eg, selecting systematic reviews for inclusion; handling primary study overlap at the analysis stage); however, several areas continue to be characterised by inconsistent or insufficient guidance.14 15 16 The lack of consensus on some of the methodologies applied in overviews of reviews means that careful reporting is required. Moreover, the reporting quality of overviews of reviews has been shown to be inconsistent and often poor.7 13 18

A reporting guideline based on evidence and agreement aims to facilitate improvements in the complete and accurate reporting of overviews of reviews.19 Until now, the reporting guidance for overviews has focused on specific components (eg, abstracts) or outcomes (eg, harms).20 21 22 23 24 25 These components were based predominantly on personal or expert experience, principles of good practice (eg, Cochrane standards), and existing reporting guidelines for other publication types.20 21 22 23 24 25 These earlier attempts sought to develop pragmatic checklists for conducting overviews of reviews but did not satisfy the current methodological standards of reporting guideline development. Further, to our best knowledge, earlier efforts to develop comprehensive reporting guidance for overviews of reviews were not completed and so far no evidence and consensus based reporting guidelines have been established for overviews of reviews.25

To address the clear need for an up-to-date, rigorously developed reporting guideline for overviews of reviews, we developed the preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR) statement. We decided a priori 26 that PRIOR would not be an extension to an existing reporting guideline (ie, the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement) and would focus on overviews that examine the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of healthcare interventions and that present descriptive summaries and meta-analyses of quantitative results. We expect that extensions of PRIOR will be needed for overviews that answer different types of questions (eg, qualitative, prognostic, diagnostic accuracy).

Methods

Approach

We registered our intent to develop PRIOR with the EQUATOR Network on 4 January 2017,27 and the protocol to develop PRIOR was published on 23 December 2019.26 We followed the methods suggested by the EQUATOR Network for developing reporting guidelines in health research.28 This process had four steps: project launch, evidence reviews, a modified Delphi exercise, and development of the reporting guideline (including checklist, explanation and elaboration document with examples, and flow diagram). The guideline development process is shown in figure 1. Before recruiting participants for the Delphi exercise, we received ethical approval via the health research ethics board at the University of Alberta (Pro00086094). Deviations from the protocol are reported in appendix 1 in the supplementary materials. Reporting adheres to the conduct and reporting of Delphi studies recommendations.29

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of development process of PRIOR statement (preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews)

Step 1—project launch

At project launch, we assembled a core team of methodological experts to lead the day-to-day operations (MG, AG, DP, RMF, ACT, MP, LH). We then appointed an international and multidisciplinary expert advisory group (EAG) consisting of three members (DM, SEB, TL), with whom we consulted for advice throughout the development of the reporting guideline. The tasks of the EAG included identifying relevant guidance documents, nominating participants for the Delphi exercise, cofacilitating and participating in the Delphi exercise, and contributing to dissemination activities.

Step 2—evidence reviews and development of the initial checklist

We conducted two evidence reviews to inform the initial list of items to include in PRIOR. The first was a systematic review on the reporting quality of a sample of overviews of reviews published between 2012 and 2016 (in preparation),30 which was supplemented by a study examining the completeness of reporting in a random sample of more contemporary overviews (published between January 2015 and March 2017).18 The second was a scoping review of methodological guidance and author reported challenges related to conducting overviews of reviews.14 We continued to monitor article alerts (ie, Google Scholar, Scopus Citing References, and PubMed Similar Articles) until publication of the reporting guideline to keep apprised of new developments that could impact its content. The core team used the findings of the reviews to inform an exhaustive list of 47 items for potential inclusion on the PRIOR checklist (appendix 2 in the supplementary materials).

Step 3—modified Delphi exercise

The Delphi technique is a structured method that aims to build consensus from a group of experts through a series of anonymous iterative questionnaires.31 In the case of PRIOR, a modified Delphi approach was used whereby a panel of 100 experts (referred to here as participants) were invited to consider and vote on the inclusion of items within the prospective list in a three round exercise designed to achieve a high level of agreement (≥70%). The number of Delphi rounds was prespecified, with the potential for additional rounds to be added if agreement could not be reached (this was not required).26 The first two rounds took place using online surveys created by the Hosted in Canada Surveys platform (https://www.hostedincanadasurveys.ca/).

We constructed the surveys according to Dillman principles32 33; the core team pilot tested each survey internally and with three research staff (external to the project team) to ensure readability, usability, and functionality. We had planned for the third and final round to occur in person; however, owing to the covid-19 pandemic we instead held two face-to-face meetings virtually using the Zoom videoconferencing platform. During the Delphi process, participants were asked to focus on the concept of each item rather than its wording.

Participant recruitment

We used purposive sampling34 to identify an international group of prospective participants. The prospective participant list was developed by the core team, with input from the EAG. We aimed to include participants with diverse experiences (eg, authors, peer reviewers, editors, readers) and roles (eg, public/patients, researchers, statisticians, librarians, healthcare professionals, policy makers), and who worked in a range of settings (eg, universities, government, non-profit organizations, major evidence synthesis centres). To identify interested patients and members of the public, we posted a call for participants on the Cochrane Task Exchange (https://taskexchange.cochrane.org/), Twitter pages for the Alberta Research Centre for Health Evidence (https://twitter.com/arche4evidence) and the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Evidence Alliance (https://twitter.com/sporalliance), and the SPOR Evidence Alliance monthly newsletter. At the time of the first Delphi round, we contacted 100 prospective participants with a personalised email that described the intent to develop the PRIOR statement, and details about their potential involvement. Informed consent from interested participants was obtained at the time of the first Delphi round. Those who declined participation were invited to recommend another candidate for potential inclusion.

Round 1—online survey

The first survey was open from 17 February 2020 to 19 April 2020 (nine weeks, which was five weeks longer than planned because of disruptions caused by the start of the covid-19 pandemic), with biweekly email reminders to encourage participation. In the first survey, participants were presented with the full list of 47 potential checklist items, in an order reflecting their logical progression within a report of an overview of reviews. For each checklist item, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with its inclusion in the checklist, using a four point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=somewhat agree, 4=strongly agree). Participants could also choose to respond with “I don’t know” and provide further explanation. An optional free text box was provided for each item, in which participants could provide justification for their response. Participants were also prompted to describe additional items that they believed were missing from the proposed list.

Based on the total number of responses received on the items, we calculated the proportion of participants who agreed or disagreed on the inclusion or exclusion of each. In doing so, a response of 1 or 2 was considered as “disagree,” and 3 or 4 as “agree.” Responses of “I don’t know” were included in the denominator but did not contribute to agreement or disagreement. The criterion for agreement to retain or remove an item was chosen a priori as ≥70%.35 Further, we collated all free text responses and grouped them into similar categories to inform wording changes and the potential for additional items.

Round 2—online survey

The second survey was distributed only to individuals who participated in the first round and was open from 6 July 2020 to 2 August 2020 (four weeks), with biweekly reminders as in round 1. The structure of the second Delphi round was similar to the first round and was presented in three parts. Firstly, participants were provided with a summary of the results of round 1, including items retained, removed, and those still needing agreement. Secondly, items still needing agreement were presented in turn, accompanied by the level of agreement and all anonymised free text comments from round 1. Participants were also able to see their personal responses from round 1. Participants were asked to re-rate each item on the same four point Likert scale after considering their original response in light of the group response and comments. Thirdly, participants rated new items originating from comments provided during round 1. As in the previous round, an optional free text box was available for an explanation for responses on each item as well as the potential to suggest additional items.

Round 3—virtual face-to-face meeting

The goal of the virtual meetings was to reach a high level of agreement on items for which agreement was not reached after the two survey rounds. A selected group of 11 survey respondents were invited to participate as so-called expert panellists in two virtual face-to-face sessions lasting two hours each on 27 and 29 October 2020. After completion of the second Delphi round, members of the core team and EAG selected panellists for their expertise with respect to the outstanding items, and with the aim of achieving perspectives from relevant stakeholder groups (ie, public or patients, authors, editors, peer reviewers, and readers). The participants’ responses on previous Delphi rounds were not considered when selecting the panellists. Two weeks before the meeting, all attendees received an information package via email, including: an agenda, background information about the development of PRIOR, considerations for the meeting (confidentiality, terms of reference, ground rules36), the qualitative and quantitative results of the round 2 survey, and an evidence summary (ie, empirical evidence supporting inadequate reporting of the item and its potential importance) for the items lacking agreement. Attendees were asked to review the information ahead of the meeting.

At the beginning of the first meeting, a core team member outlined the aim of PRIOR and the purpose and general structure of the meetings. For each item not previously reaching agreement, a facilitator (member of the core team or EAG) then provided a summary of the round 2 survey results (descriptive statistics and summary of comments) orally, as well as visually on slides. Next, participants discussed each item for about 15-20 min, with prompting by the facilitator, as needed. Recognising that each participant had inherent biases, the facilitator used prompts to ensure that arguments for and against the inclusion or exclusion of each item were discussed. Following discussion, the facilitator summarised the main points and the expert panellists and EAG members were prompted to vote on the inclusion of each item (yes or no) via a Zoom poll. At this time, only two response categories were available (“agree” or “disagree” with inclusion of the item). If ≥70% agreement for inclusion or exclusion was not reached, the item was set aside for further discussion later in the meeting as time allowed. Both meetings were audio recorded. A notetaker recorded the results of each poll, as well as any wording or other suggestions that arose during the discussions. After the meetings, a summary of the main discussion points was developed and shared with those who had participated.

Step 4—development of the guideline

Finalising the draft guideline

After the virtual meetings, the core team and EAG debriefed and finalised a draft guideline, incorporating the feedback received during the Delphi rounds. The guideline includes the PRIOR checklist; the explanation and elaboration document, which incorporates a rationale and detailed guidance for the reporting of each item; and the PRIOR flow diagram (not part of the Delphi rounds; modelled after the PRISMA statement by the core team, with opportunity for comment by others). Given the uptake of PRISMA in systematic reviews, explicit effort was made to align the wording and structure of elements of the PRIOR statement with those of the PRISMA 2020 statement.37 Although PRIOR is not a PRISMA extension, this alignment was expected to facilitate the usability and uptake of PRIOR.

Pilot testing

We sought a convenience sample of authors to pilot test the guideline. On 7 May 2021, we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the preprint server MedRxiv (https://www.medrxiv.org/), and the journal BMC Systematic Reviews to identify recently published (in full or in preprint) overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. We invited 21 corresponding authors (in order of most recent to least recent from each source) to complete a pilot testing exercise using the draft version of the PRIOR statement. The author team, and all others involved in the Delphi rounds, were not eligible for the pilot testing exercise, to allow independent feedback on the draft. We provided each author with documents related to the guideline and asked that they attempt to use the checklist on one of their recently completed overviews of reviews. After completing this process, we solicited comments about the usability and comprehensibility of the items. We collated responses from the participants, and after consideration of all responses, used these to inform wording and structural changes to the draft.

Patient and public involvement

The 100 prospective participants for the modified Delphi exercise included 11 members of the public and patients. Seven members of the public or patients participated in at least one of the two online surveys. Among the 11 individuals invited to take part in the virtual face-to-face meeting, two identified as a member of the public or patient. Two members of the public and patients (KM, SJM) met our pre-established criteria for authorship, which included participation in both online surveys, participation in both sessions of the virtual face-to-face meeting, contribution to drafting the manuscript, review of the draft manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Results

Participants

Of the 100 invited participants, 52 completed the round 1 survey (table 1). We were successful in gathering an international group spanning five continents and 16 countries; most participants resided in Canada (n=12/52, 23%), US (n=10/52, 19%), Australia (n=7/52, 13%), or UK (n=7/52, 13%). About half of the participants were female (n=27/52, 52%) and most were aged between 30 and 49 years (n=33/52, 63%). As intended, participants were generally highly experienced in multiple relevant roles; three quarters (n=39/52, 75%) had authored an overview of reviews, 37% (n=19/52) were journal editors, 71% (n=37/52) were peer reviewers, and 75% (n=39/52) were end users (eg, readers). Seventy nine per cent (n=41/52) of participants had at least seven years of experience conducting evidence syntheses, and 63% (n=33/52) had at least four years of experience specifically conducting overviews of reviews.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Delphi participants (n=52)

| Characteristic | No (%) of participants |

|---|---|

| Country of residence | |

| Australia | 7 (13) |

| UK | 7 (13) |

| Germany | 3 (6) |

| Greece | 3 (6) |

| Canada | 12 (23) |

| US | 10 (19) |

| Other* | 10 (19) |

| Age (years) | |

| <20 | 1 (2) |

| 20-29 | 2 (4) |

| 30-39 | 15 (29) |

| 40-49 | 18 (35) |

| 50-59 | 9 (17) |

| 60-69 | 4 (8) |

| ≥70 | 3 (6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 27 (52) |

| Male | 23 (44) |

| Other | 1 (2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2) |

| Experience with overviews of reviews† | |

| Author | 39 (75) |

| End user (eg, reader) | 39 (75) |

| Peer reviewer | 37 (71) |

| Journal editor | 19 (37) |

| Years of experience conducting evidence synthesis | |

| No experience | 1 (2) |

| <1 | 0 (0) |

| 1-3 | 2 (4) |

| 4-6 | 8 (15) |

| 7-10 | 13 (25) |

| ≥10 | 28 (54) |

| Years of experience conducting overviews of reviews‡ | |

| No experience | 6 (12) |

| <1 | 5 (10) |

| 1-3 | 7 (13) |

| 4-6 | 17 (33) |

| 7-10 | 11 (21) |

| ≥10 | 5 (10) |

One respondent from each of the following countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Iran, Israel, Japan, Lebanon.

Multiple responses were permitted.

There was one non-response.

Round 1 results—online survey

Agreement (≥70%) was reached for the inclusion of 43/47 (91%) of the items presented on the round 1 survey (appendix 3 in the supplementary materials). Agreement was not reached for the exclusion of any items. Based on the comments, we drafted five new items for consideration on the round 2 survey. These items pertained to the reporting of the involvement of decision makers (eg, clinicians, policy makers, patient groups) in the overview of reviews; a plain language summary, or policy or clinical brief; the methodological and reporting standards used to inform the conduct and reporting of the overview of reviews; the methods used to assess the risk of bias owing to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases at the systematic review and primary study levels); and the findings of assessments of risk of bias owing to missing results in a synthesis.

Round 2 results—online survey

Eighty five per cent (n=44/52) of the round 1 participants responded to the round 2 survey. Agreement (≥70%) was not reached for the inclusion or exclusion of any of the nine items on the survey (four items that did not reach agreement in the first round, and five new items; appendix 4 in the supplementary materials). Based on the comments, no new items were added or changed after this round.

Round 3 results—virtual face-to-face meeting

A total of 19 individuals participated in the virtual face-to-face meetings: six core team members, three EAG members, and 10 of the 11 invited expert panellists. Thirteen individuals participated in the voting process (all but the core team, who did not vote). One invited expert could not attend and did not contribute to voting but provided comments on the meeting minutes.

During the initial voting process, agreement was reached for excluding five of the nine items (≥77% agreement) for which agreement had not been reached on the round 2 survey (appendix 5 in the supplementary materials). For three items (two on risk of bias owing to missing results in a synthesis (a methods item and a corresponding results item) and one on summarising the risk of bias of primary studies), there was substantial discussion regarding their wording. Voting for these items was for their concept (irrespective of wording). Voting members agreed that the items should be retained (≥85% for each item); the core team committed to reworking the items during post-meeting revisions. For the final item (reporting of the method for managing and tracking records during selection), there was near agreement (69%) for exclusion. In an attempt to gain ≥70% agreement, discussion continued and the following edits were suggested: the item itself would be removed, and the content of the item would instead be incorporated into the associated checklist item on study selection (item 8a). Ninety two per cent agreement was achieved for this decision.

Development of the guideline

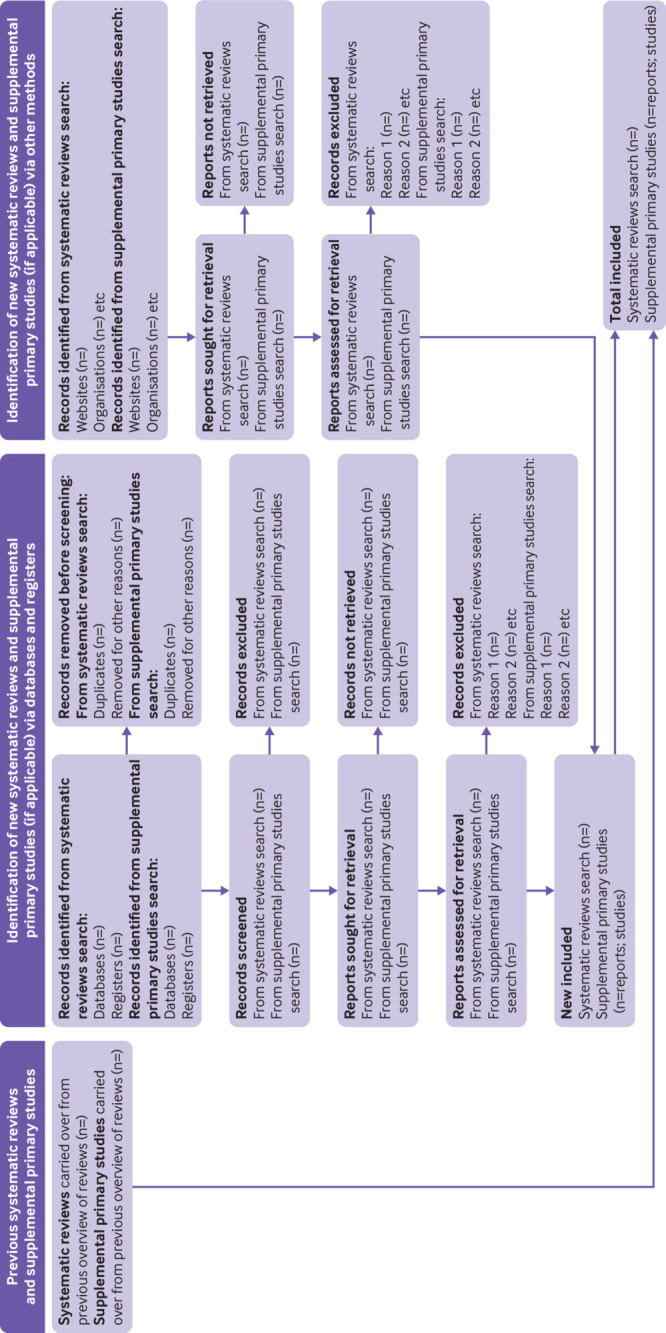

After the virtual meetings, members of the core team edited the checklist based on the group discussion. Of the 21 contacted, six (29%) authors of recently completed overviews of reviews participated in pilot testing and commented on the usability of the guideline. Iterative reviews of the final checklist by the author team, in addition to the pilot testing by overview authors, resulted in minor wording changes but no changes to the content of the checklist. The final PRIOR statement contains 27 main items with 19 sub-items (table 2). Terminology used in the guideline is shown in box 1. The explanation and elaboration document (web appendix 2) includes a rationale for the inclusion of each item, essential and additional elements to report, and an illustrative example from a published overview of reviews.49 The PRIOR flow diagram is shown in figure 2.

Table 2.

PRIOR checklist (preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews)

| Section topic |

Item No | Item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as an overview of reviews. | |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | Provide a comprehensive and accurate summary of the purpose, methods, and results of the overview of reviews. | |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for conducting the overview of reviews in the context of existing knowledge. | |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) addressed by the overview of reviews. | |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5a | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the overview of reviews. If supplemental primary studies were included, this should be stated, with a rationale. | |

| 5b | Specify the definition of “systematic review” as used in the inclusion criteria for the overview of reviews. | ||

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify systematic reviews and supplemental primary studies (if included). Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, such that they could be reproduced. Describe any search filters and limits applied. | |

| Selection process | 8a | Describe the methods used to decide whether a systematic review or supplemental primary study (if included) met the inclusion criteria of the overview of reviews. | |

| 8b | Describe how overlap in the populations, interventions, comparators, and/or outcomes of systematic reviews was identified and managed during study selection. | ||

| Data collection process | 9a | Describe the methods used to collect data from reports. | |

| 9b | If applicable, describe the methods used to identify and manage primary study overlap at the level of the comparison and outcome during data collection. For each outcome, specify the method used to illustrate and/or quantify the degree of primary study overlap across systematic reviews. | ||

| 9c | If applicable, specify the methods used to manage discrepant data across systematic reviews during data collection. | ||

| Data items | 10 | List and define all variables and outcomes for which data were sought. Describe any assumptions made and/or measures taken to identify and clarify missing or unclear information. | |

| Risk of bias assessment | 11a | Describe the methods used to assess risk of bias or methodological quality of the included systematic reviews. | |

| 11b | Describe the methods used to collect data on (from the systematic reviews) and/or assess the risk of bias of the primary studies included in the systematic reviews. Provide a justification for instances where flawed, incomplete, or missing assessments are identified but not reassessed. | ||

| 11c | Describe the methods used to assess the risk of bias of supplemental primary studies (if included). | ||

| Synthesis methods | 12a | Describe the methods used to summarise or synthesise results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). | |

| 12b | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among results. | ||

| 12c | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesised results. | ||

| Reporting bias assessment | 13 | Describe the methods used to collect data on (from the systematic reviews) and/or assess the risk of bias due to missing results in a summary or synthesis (arising from reporting biases at the levels of the systematic reviews, primary studies, and supplemental primary studies, if included). | |

| Certainty assessment | 14 | Describe the methods used to collect data on (from the systematic reviews) and/or assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | |

| Results | |||

| Systematic review and supplemental primary study selection | 15a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, including the number of records screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the overview of reviews, ideally with a flow diagram. | |

| 15b | Provide a list of studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but were excluded, with the main reason for exclusion. | ||

| Characteristics of systematic reviews and supplemental primary studies | 16 | Cite each included systematic review and supplemental primary study (if included) and present its characteristics. | |

| Primary study overlap | 17 | Describe the extent of primary study overlap across the included systematic reviews. | |

| Risk of bias in systematic reviews, primary studies, and supplemental primary studies | 18a | Present assessments of risk of bias or methodological quality for each included systematic review. | |

| 18b | Present assessments (collected from systematic reviews or assessed anew) of the risk of bias of the primary studies included in the systematic reviews. | ||

| 18c | Present assessments of the risk of bias of supplemental primary studies (if included). | ||

| Summary or synthesis of results | 19a | For all outcomes, summarise the evidence from the systematic reviews and supplemental primary studies (if included). If meta-analyses were done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | |

| 19b | If meta-analyses were done, present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity. | ||

| 19c | If meta-analyses were done, present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of synthesised results. | ||

| Reporting biases | 20 | Present assessments (collected from systematic reviews and/or assessed anew) of the risk of bias due to missing primary studies, analyses, or results in a summary or synthesis (arising from reporting biases at the levels of the systematic reviews, primary studies, and supplemental primary studies, if included) for each summary or synthesis assessed. | |

| Certainty of evidence | 21 | Present assessments (collected or assessed anew) of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome. | |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 22a | Summarise the main findings, including any discrepancies in findings across the included systematic reviews and supplemental primary studies (if included). | |

| 22b | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | ||

| 22c | Discuss any limitations of the evidence from systematic reviews, their primary studies, and supplemental primary studies (if included) included in the overview of reviews. Discuss any limitations of the overview of reviews methods used. | ||

| 22d | Discuss implications for practice, policy, and future research (both systematic reviews and primary research). Consider the relevance of the findings to the end users of the overview of reviews, eg, healthcare providers, policymakers, patients, among others. | ||

| Other information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 23a | Provide registration information for the overview of reviews, including register name and registration number, or state that the overview of reviews was not registered. | |

| 23b | Indicate where the overview of reviews protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | ||

| 23c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. Indicate the stage of the overview of reviews at which amendments were made. | ||

| Support | 24 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the overview of reviews, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the overview of reviews. | |

| Competing interests | 25 | Declare any competing interests of the overview of reviews' authors. | |

| Author information | 26a | Provide contact information for the corresponding author. | |

| 26b | Describe the contributions of individual authors and identify the guarantor of the overview of reviews. | ||

| Availability of data and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are available, where they can be found, and under which conditions they may be accessed: template data collection forms; data collected from included systematic reviews and supplemental primary studies; analytic code; any other materials used in the overview of reviews. | |

Box 1. Terminology used in the PRIOR statement (preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews).

Systematic review

A systematic review is a type of study design that uses systematic, reproducible methods to collect data on primary research studies, critically appraises the available research, and synthesises the findings descriptively or quantitatively. Typically, reviews considered to be systematic will include a research question, the sources that were searched, with a reproducible search strategy, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the methods used to select primary studies, assessments of risk of bias in the included primary studies, and information about data analysis and synthesis that allows the results to be reproduced.38 However, systematic reviews might lack some of these components, for example, risk of bias assessments.

Overview of reviews

An overview of reviews uses “explicit and systematic methods to search for and identify multiple systematic reviews on a similar topic for the purpose of extracting and analysing their results across important outcomes. Thus, the unit of searching, inclusion and data analysis is the systematic review.”39 40 The purpose of overviews of reviews is to describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a certain topic or to look at a new review question that has not previously been analysed by systematic reviews.39 40 Overviews of reviews might include supplemental primary studies (eg, if the included systematic reviews are incomplete or out of date; see definition below).

Other common terms used to describe overviews of reviews include “overviews,” “overviews of systematic reviews,” “metareviews,” “umbrella reviews,” “reviews of systematic reviews,” and “systematic reviews of reviews.” We selected the term “overview of reviews” for PRIOR at the protocol stage, as at that time it had gained widespread acceptance 11 and was the most frequent label used among overviews of reviews published from 2000 to 2011.7 However, the nomenclature over time has changed, with a more recent study finding “overviews of systematic reviews” to be more commonly used.41 In PRIOR, we have retained “overviews of reviews” for simplicity.

Importantly, overviews of reviews are distinct from network meta-analyses. A network meta-analysis is a statistical technique used to compare three or more interventions simultaneously within one statistical model using both direct and indirect evidence from the contributing studies.42 Network meta-analyses can be used in the context of systematic reviews or overviews of reviews. However, in the case of overviews of reviews, it can be more difficult to assess the assumption of transitivity (which underlies the validity of the indirect comparisons) because the information required to make this assessment is often not reported in the constituent systematic reviews. For this reason, the use of network meta-analyses in overviews of reviews is generally discouraged.40

Primary studies

Primary studies are reports of individual studies used to investigate the efficacy or effectiveness or safety of healthcare interventions (as this guideline is not meant to apply to diagnostic, prognostic, qualitative, or other overviews). Primary studies involve collecting data directly from human participants. We refer to “primary studies” when describing the individual studies included in systematic reviews.

Supplemental primary studies

Sometimes, after identifying all relevant systematic reviews, important gaps in coverage of evidence relating to the overview topic remain (eg, some systematic reviews are outdated) and authors of overviews of reviews choose to search for and include additional primary studies. We refer to these additional primary studies as “supplemental primary studies.”

Primary study overlap

Authors of overviews of reviews might include two or more systematic reviews that examine the same intervention for the same condition, and that include some of the same primary studies (sometimes called “overlapping systematic reviews”).40 We refer to “primary study overlap” when describing the extent to which the same primary studies are represented across the included systematic reviews in an overview of reviews.

Discrepant or discordant data

Sometimes systematic reviews present different study characteristics, different results data, or different assessments of risk of bias or methodological quality for the same primary studies. When this occurs, we refer to the data or assessments as being discrepant across the included systematic reviews. To a degree, some discrepancy can be expected, because risk of bias appraisals are not completely objective, and data extraction errors are prevalent in systematic reviews.43 The term “discordant” has been also used to refer to these issues18 or to systematic reviews on the same topic that draw different conclusions. For the purpose of PRIOR, we consider the terms to be equivalent.

Risk of bias and methodological quality

Terminology—Risk of bias and methodological quality are related, yet distinct constructs. Methodological quality has been defined as assessing the extent to which a study has been planned and performed to the highest possible standard of conduct (eg, Cochrane standards for conduct).44 Items included in tools that are used to assess methodological quality are variable and include items beyond those that might introduce bias (eg, description of characteristics of included studies). By contrast, the risk of bias of a study refers to the potential for a study to systematically overestimate or underestimate the true effect due to methodological limitations; this is also termed “internal validity.”45 Risk of bias is distinct from external validity (also referred to as generalisability or applicability), which refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other populations and settings.45

Types of bias—In an overview of reviews, risk of bias might be assessed at multiple levels. At the level of the included systematic reviews, bias could be introduced during development of the eligibility criteria, during the identification and selection of studies, in the choice of methods used to collect data and appraise included studies, and while synthesising the findings from individual studies and drawing conclusions.46 At the level of the primary study (ie, within the included systematic reviews or as supplemental primary studies), bias in, for example, randomised controlled trials could arise from the randomisation process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and in the selection of the reported result (note that different items would need to be assessed for observational studies).47

A further type of bias affecting meta-analysis estimates can arise owing to non-reporting bias (often referred to as reporting bias)48—that is, when there is selective publication of studies, or results within studies, leading to a non-representative set of studies included in the meta-analysis.48 While guidance and a tool for assessing the risk of bias due to missing results is available in the context of systematic reviews,48 this has not yet been extended to overviews of reviews. However, approaches for assessing reporting bias in overviews of reviews have been catalogued.16

Collect versus assess

At various stages of the overview of reviews, there is the option to either collect data from systematic reviews, or to assess anew (eg, collect data on risk of bias or certainty of the evidence, or assess anew). We use the word “collect” to indicate that data are extracted directly as they are reported in the included systematic reviews. When the desired data are missing from the included systematic reviews (or are deemed unreliable or inappropriate), authors of overviews of reviews could assess (ie, estimate or evaluate) relevant items themselves by returning to the primary studies and performing the work anew (eg, assessment of risk of bias, certainty of evidence).

Fig 2.

PRIOR flow diagram (in relation to preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews). *Appendix 6 in the supplementary materials includes the contextual information used to complete the flow diagram

A separate checklist for use is available in web appendix 3.

Discussion

Reporting guideline

The growing popularity of overviews of reviews in recent years has resulted in the need for a harmonised, credible, evidence based reporting guideline for authors. Alongside recently updated methodological guidance,39 40 PRIOR fills a pressing need for an evidence based reporting guideline. PRIOR is the first reporting guideline for overviews of reviews to be developed that adheres to the rigorous, systematic, and transparent methodology outlined by Moher et al.28 Specifically, the guideline integrates the most recent available empirical evidence on the conduct and reporting of overviews of reviews, as well as the perspectives of a variety of stakeholders worldwide with wide ranging expertise in evidence synthesis (ie, authors, peer reviewers, editors, readers). Adherence to the PRIOR statement will enable more complete and accurate reporting of future overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions, which will in turn, improve their reproducibility, trustworthiness, and usefulness for end users (eg, healthcare providers, healthcare decision makers, policy makers, and public or patients).

The standalone nature of the PRIOR statement acknowledges the methodological and reporting challenges that are unique to the production of overviews of reviews. Compared to systematic reviews, authors of overviews of reviews are faced with the additional layer of complexity that comes with synthesising two levels of related evidence: the included systematic reviews, and their included primary studies. Authors undertaking overviews of reviews might be faced with poorly reported or conducted systematic reviews, which can impede a thorough understanding of the characteristics and quality of their included primary studies. Although the PRIOR statement does not aim to offer methodological guidance, it provides reporting standards that will help authors to understand the minimum information that should be reported such that readers can understand where bias or uncertainty might have been introduced. For example, the risk of bias or quality of both the systematic reviews and their included studies should be reported, but PRIOR does not stipulate how this should be accomplished when information about the primary studies is missing or incompletely reported in the included systematic reviews. The explanation and elaboration document provides guidance on the options that authors could consider when faced with such scenarios, based on our scoping review of the available methodological guidance for overviews of reviews.14

Dissemination and evaluation

Wide dissemination and uptake of the PRIOR statement will be essential to reach the end goal of improved reporting of overviews of reviews. Our dissemination plan will include housing the checklist on the EQUATOR network website (https://www.equator-network.org/ ); launching a PRIOR website or the addition of a tab to the PRISMA website, which receives high traffic; developing infographics or tip sheets; preparing a slide deck for those who wish to incorporate PRIOR into their teaching; and sharing the PRIOR statement widely via social media channels (eg, Twitter), email listservs, and in relevant newsletters. Although few published evaluations exist, evidence suggests that the endorsement of PRISMA by journals is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews than in journals not endorsing the reporting guideline.50 51 52 We will actively contact journal editors to seek their endorsement of PRIOR and recommend that their authors use the checklist to inform their reporting, require a completed PRIOR checklist and flow diagram for all submitted overviews of reviews, and encourage use by peer reviewers.

It will similarly be important to evaluate the impact of PRIOR on the reporting of future overviews of reviews, potentially by regularly updating (eg, every five years) our existing systematic review, which audits the reporting quality of published overviews of reviews. An appraisal of how the endorsement of PRIOR by journals affects the reporting of overviews of reviews published in those journals, akin to previous work, would be valuable.50 Integral to the usability of the PRIOR statement will be an openness to feedback from authors using the guideline. Comments from authors on their experience in using PRIOR are encouraged, for example, by contacting the PRIOR core team. The information gathered could help to enhance the uptake of PRIOR, and will be useful in informing future updates, which will be expected periodically (eg, every five years) to incorporate emerging empirical evidence on the ideal reporting of overviews of reviews.

Limitations

The final guideline could have been different had another set of participants been included in the Delphi exercise. We used a ≥70% threshold for inclusion or exclusion of items in the guideline and far exceeded this threshold for most items. However, the final included items might have differed slightly had a higher or lower threshold been used. We originally planned to have an in-person meeting for round 3 of the modified Delphi exercise; however, we held the meeting online via Zoom owing to travel restrictions during the covid-19 pandemic. A face-to-face meeting might have brought about additional or more in-depth conversations that could have resulted in differences in the final guideline. In addition, the results of the virtual in-person meeting could have been different had we selected the panellists based on their responses to previous Delphi rounds. The guideline has been pilot tested by six authors of published overviews of reviews who were not involved in its development; while this pilot test resulted in only minor edits, additional changes could have been suggested with a larger sample. We did not collect information on the clinical expertise or patient experience of participants, or of those who pilot tested the guideline. Representation of all potentially relevant specialties was unlikely; how this might have affected the final checklist is unclear.

The PRIOR statement is intended for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions and might not apply to other fields or other types of overviews of reviews (eg, qualitative, diagnostic accuracy). The guideline is based on currently available evidence regarding the reporting of published overviews,30 a scoping review of currently available methodological guidance,14 and other recent evidence maps regarding the methods used in overviews of reviews.15 16 We acknowledge that for some items, little or no methodological guidance is available for overview of reviews authors (eg, the adaptation of GRADE to overviews, the assessment of missing results in a synthesis), and that in time PRIOR will require an update. The authors of PRIOR strongly believe that the inclusion of these items was essential to establish a precedent for the complete and transparent reporting of overviews of reviews, to encourage the methodological research that is needed to advance the science of overviews of reviews, and to be consistent with other related guidelines (eg, PRISMA 202037). Owing to a lack of methodological advice for some aspects of overviews of reviews, authors should clearly state what they have done. Given that the reporting of published overviews of reviews varies and is often suboptimal, the examples in the explanation and elaboration document are sometimes imperfect and should be considered illustrative. We suggest that authors of overviews of reviews rely on the list of essential items to guide their reporting. Doing so will allow readers and other overview authors to understand what has been done (eg, what methods are used and where there is variation). Moreover, overview authors might need to make decisions that involve trade-offs between rigor and feasibility; therefore, use of the PRIOR statement will allow readers to assess if and how much bias might have been introduced by these decisions.

Conclusions

PRIOR addresses a clear need for an up-to-date, rigorously developed reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. The list of items to be reported, along with the rationale and example given for each item, provides a framework for overview of reviews authors that aims to encourage the thorough and transparent reporting of their work. We hope that widespread dissemination and uptake of PRIOR will strengthen the reporting of overviews of reviews and allow end users (eg, healthcare providers, healthcare decision makers, policy makers, public or patients) to better evaluate their quality and applicability. We expect PRIOR to require periodic updates as evidence related to the conduct and reporting of overviews of reviews accumulates.

What is already known on this topic

The publication of systematic reviews has rapidly increased, making it challenging to remain apprised of and interpret evidence from their growing number

A newer form of evidence synthesis, the overview of reviews, synthesises evidence from multiple systematic reviews

Authors would benefit from evidence and consensus based guidance for the complete and transparent reporting of overviews of reviews; in turn, this guidance will improve their reproducibility, trustworthiness, and usefulness for readers and end users (eg, healthcare providers, healthcare decision makers, policy makers, and the public or patients)

What this study adds

The PRIOR statement (preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews) provides an evidence based reporting guideline developed using established, rigorous methods that involved a four stage process (project launch, evidence reviews, modified Delphi exercise, development of the reporting guideline)

An international stakeholder group representing varied experiences (eg, authors, peer reviewers, editors, readers) and roles (eg, public/patients, researchers, statisticians, librarians, healthcare professionals, policymakers) was also involved and provided feedback

The PRIOR statement includes a checklist with 27 main items that cover all steps and considerations involved in planning and conducting an overview of reviews of healthcare interventions; an explanation and elaboration document with rationale, essential elements, additional elements, and example for each item; and a flow diagram

Acknowledgments

We thank Samantha Guitard for coordinating the pilot testing and author feedback, and pilot testing the Delphi surveys; Sarah Elliott and Shannon Sim for pilot testing the Delphi surveys; all the participants of the Delphi rounds; Matthew Page for providing feedback after the virtual meeting; and all the participants who pilot tested the final version of the checklist and provided feedback. The study is registered at: https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-systematic-reviews/.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix 1: Supplementary materials, containing appendices 1-7

Web appendix 2: PRIOR Explanation and Elaboration

Web appendix 3: PRIOR Checklist

Contributors: MG, AG, DP, RMF, ACT, DM, SEB, TL, MP, SDS, and LH were responsible for the conception and design of the work. MG, AG, DP, RMF, ACT, DM, SEB, TL, MP, CL, DS, JEM, SDS, KAR, KM, KIB, PF-P, PW, SS, SJM, and LH contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. MG and AG drafted the manuscript. All authors revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the manuscript submitted, and agreed to be accountable for the work. LH is the study guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: No specific funding was received for this project. ACT is funded by a tier 2 Canada Research Chair for knowledge synthesis. TL was funded by grant UG1EY020522 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. CL is funded through a 2020 Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant (2021-2024). JEM is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council career development fellowship (1143429). SDS is supported by a Canada Research Chair for knowledge translation in child health. SJM was supported by the CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada doctoral scholarship. LH is supported by a Canada Research Chair for knowledge synthesis and translation.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; AG and MG are employees of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); the current work was unrelated to their employment at CADTH and CADTH had no role in the funding, design, or oversight of the work; ACT is an author of PRISMA 2020 and lead author of the PRISMA extension to scoping reviews; DM is co-lead of PRISMA 2020, coauthor of the PRISMA extension to scoping reviews, corresponding author of the EQUATOR guidance of how to develop reporting guidelines, and chair of the EQUATOR Network; SEB and PW are authors of PRISMA 2020; JEM is co-lead of PRISMA 2020; LH is co-author of the PRISMA extension to scoping reviews; all other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

The corresponding author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We plan to disseminate a summary of the study, with links to the manuscript and supplementary files, to participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

For the Delphi component, we received ethical approval via the University of Alberta’s health research ethics board (Pro00086094).

Data availability statement

All data are presented in the manuscript and supplemental files.

References

- 1. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91-108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoffmann F, Allers K, Rombey T, et al. Nearly 80 systematic reviews were published each day: Observational study on trends in epidemiology and reporting over the years 2000-2019. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;138:1-11. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fontelo P, Liu F. A review of recent publication trends from top publishing countries. Syst Rev 2018;7:147. 10.1186/s13643-018-0819-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ioannidis JP. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q 2016;94:485-514. 10.1111/1468-0009.12210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002028. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pussegoda K, Turner L, Garritty C, et al. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst Rev 2017;6:131. 10.1186/s13643-017-0527-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartling L, Chisholm A, Thomson D, Dryden DM. A descriptive analysis of overviews of reviews published between 2000 and 2011. PLoS One 2012;7:e49667. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bougioukas KI, Vounzoulaki E, Mantsiou CD, et al. Global mapping of overviews of systematic reviews in healthcare published between 2000 and 2020: a bibliometric analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;137:58-72. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lunny C, Neelakant T, Chen A, et al. Bibliometric study of ‘overviews of systematic reviews’ of health interventions: Evaluation of prevalence, citation and journal impact factor. Res Synth Methods 2022;13:109-20. 10.1002/jrsm.1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health 2018;21:95-100. 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev 2018;7:39. 10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ioannidis JPA. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 2009;181:488-93. 10.1503/cmaj.081086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pieper D, Buechter R, Jerinic P, Eikermann M. Overviews of reviews often have limited rigor: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1267-73. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gates M, Gates A, Guitard S, Pollock M, Hartling L. Guidance for overviews of reviews continues to accumulate, but important challenges remain: a scoping review. Syst Rev 2020;9:254. 10.1186/s13643-020-01509-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 1-purpose, eligibility, search and data extraction. Syst Rev 2017;6:231. 10.1186/s13643-017-0617-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 2-risk of bias assessment; synthesis, presentation and summary of the findings; and assessment of the certainty of the evidence. Syst Rev 2018;7:159. 10.1186/s13643-018-0784-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Overviews of systematic reviews: great promise, greater challenge. Syst Rev 2017;6:185. 10.1186/s13643-017-0582-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lunny C, Brennan SE, Reid J, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Overviews of reviews incompletely report methods for handling overlapping, discordant, and problematic data. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;118:69-85. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bougioukas KI, Bouras E, Apostolidou-Kiouti F, Kokkali S, Arvanitidou M, Haidich AB. Reporting guidelines on how to write a complete and transparent abstract for overviews of systematic reviews of health care interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;106:70-9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, Ntzani E, Haidich AB. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;93:9-24. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li L, Tian J, Tian H, Sun R, Liu Y, Yang K. Quality and transparency of overviews of systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med 2012;5:166-73. 10.1111/j.1756-5391.2012.01185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Onishi A, Furukawa TA. State-of-the-Art Reporting. In: Biondi-Zoccai G, ed. Umbrella Reviews: Evidence Synthesis with Overviews of Reviews and Meta-Epidemiologic Studies. Springer International Publishing, 2016: 189-202 10.1007/978-3-319-25655-9_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singh JP. Development of the metareview assessment of reporting quality (MARQ) checklist. Rev Fac Med Univ Nac Colomb 2012;60:325-32. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Posadzki P. Standards for reporting of overviews of reviews and umbrella reviews (STROVI) statement. Abstracts of the Global Evidence Summit, Cape Town, South Africa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017:9(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev 2019;8:335. 10.1186/s13643-019-1252-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.EQUATOR Network. Reporting guidelines under development for systematic reviews. 2018. https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/.

- 28. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000217. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684-706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pieper D, Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Büchter RB, Hartling L. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions published 2012-2016: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2017;6:73. 10.1186/s13643-017-0468-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess, Res Eval 2007;12:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dillman DA, Tortora RD, Bowker D, eds. J Am Stat Assoc. 1998. http://www.websm.org/db/12/2881/rec [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method–2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401-9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chatham House . Chatham House Rule. Chatham House, 2021. [Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/about-us/chatham-house-rule ] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Page MJ, McKenzie J, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews: MetaArXiv 2020. 10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:203. 10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Umbrella Reviews. In: Aromataris EM, ed. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joana Briggs Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pollock M, Fernandes R, Becker L, Pieper D, Hartling L. Overviews of reviews. In: Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Li T, Page MJ, Welch V, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 61 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lunny C, McKenzie JE, McDonald S. Retrieval of overviews of systematic reviews in MEDLINE was improved by the development of an objectively derived and validated search strategy. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74:107-18. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chaimani A, Caldwell DM, Li T, Higgins J, Salanti G. Undertaking network meta-analyses. In: Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 61 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mathes T, Klaßen P, Pieper D. Frequency of data extraction errors and methods to increase data extraction quality: a methodological review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:152. 10.1186/s12874-017-0431-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boutron IPM, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hrobjartsson A. Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In: Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 61. Cochrane, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, et al. ROBIS group . ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:225-34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. In: Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 62 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gates M, Gates A, Pieper D, et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: The Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) Explanation & Elaboration. MetaArXiv 2022. 10.31222/osf.io/23b6j [DOI]

- 50. Stevens A, Shamseer L, Weinstein E, et al. Relation of completeness of reporting of health research to journals’ endorsement of reporting guidelines: systematic review. BMJ 2014;348:g3804. 10.1136/bmj.g3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews of Biomedical Research: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002028. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Veroniki AA, Tsokani S, Zevgiti S, et al. Do reporting guidelines have an impact? Empirical assessment of changes in reporting before and after the PRISMA extension statement for network meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2021;10:246. 10.1186/s13643-021-01780-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix 1: Supplementary materials, containing appendices 1-7

Web appendix 2: PRIOR Explanation and Elaboration

Web appendix 3: PRIOR Checklist

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in the manuscript and supplemental files.