Abstract

Background

Existing mental health treatments are insufficient for addressing mental health needs at scale, particularly for teenagers, who now seek mental health information and support on the web. Single-session interventions (SSIs) may be particularly well suited for dissemination as embedded web-based support options that are easily accessible on popular social platforms.

Objective

We aimed to evaluate the acceptability and effectiveness of three SSIs, each with a duration of 5 to 8 minutes (Project Action Brings Change, Project Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere, and REFRAME)—embedded as Koko minicourses on Tumblr—to improve three key mental health outcomes: hopelessness, self-hate, and the desire to stop self-harm behavior.

Methods

We used quantitative data (ie, star ratings and SSI completion rates) to evaluate acceptability and short-term utility of all 3 SSIs. Paired 2-tailed t tests were used to assess changes in hopelessness, self-hate, and the desire to stop future self-harm from before to after the SSI. Where demographic information was available, the analyses were restricted to teenagers (13-19 years). Examples of positive and negative qualitative user feedback (ie, written text responses) were provided for each program.

Results

The SSIs were completed 6179 times between March 2021 and February 2022. All 3 SSIs generated high star ratings (>4 out of 5 stars), with high completion rates (approximately 25%-57%) relative to real-world completion rates among other digital self-help interventions. Paired 2-tailed t tests detected significant pre-post reductions in hopelessness for those who completed Project Action Brings Change (P<.001, Cohen dz=−0.81, 95% CI −0.85 to −0.77) and REFRAME (P<.001, Cohen dz=−0.88, 95% CI −0.96 to −0.80). Self-hate significantly decreased (P<.001, Cohen dz=−0.67, 95% CI −0.74 to −0.60), and the desire to stop self-harm significantly increased (P<.001, Cohen dz=0.40, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.47]) from before to after the completion of Project Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere. The results remained consistent across sensitivity analyses and after correcting for multiple tests. Examples of positive and negative qualitative user feedback point toward future directions for SSI research.

Conclusions

Very brief SSIs, when embedded within popular social platforms, are one promising and acceptable method for providing free, scalable, and potentially helpful mental health support on the web. Considering the unique barriers to mental health treatment access that many teenagers face, this approach may be especially useful for teenagers without access to other mental health supports.

Keywords: web-based intervention, internet intervention, digital intervention, single-session intervention, mental health

Introduction

Limited Accessibility of Existing Mental Health Treatments

Existing mental health treatments have long been inaccessible due to well-established structural (eg, cost, transportation, and time) and individual (eg, stigma and distrust of providers) barriers [1-3]. Furthermore, people experiencing suicidal thoughts or engaging in self-harm often fear the negative consequences of disclosing these experiences (eg, involuntary hospitalization) [4,5], creating additional barriers to treatment among those who may need it most. This is particularly true for teenagers whose caregivers often serve as gatekeepers for their own mental health care [6-8] and who often fear the involvement of a caregiver without their consent [5].

To fill the gap between the need for support and access to it, many teenagers seek and receive mental health support on the web [9,10]. Specifically, a majority (61%-85%) of teens and young adults have sought information or help for their mental health on the web [10-12]. Teenagers report using web-based mental health resources as a way to obtain free, easily accessible, or anonymous support [12,13], and web-based communities via social platforms (eg, forums and discussion boards) offer a space to share one’s experiences with others who have faced similar challenges [14-17]. Youth facing greater psychological distress are also more likely to search for and discuss topics related to their mental health on the web [15]. Thus, these web-based communities in social platforms represent a unique, underexplored avenue for reaching teenagers in need of mental health support.

Offering Mental Health Support via Web-Based Social Platforms

Initial efforts suggest that it is possible to provide mental health supports that are integrated into existing web-based social platforms. Koko, a nonprofit, web-based mental health platform, provides on-demand peer support [18,19], crisis triage [20], and self-guided interventions on topics such as body image, self-harm, and stress management. People can access Koko services on various messenger apps (eg, Telegram, Facebook Messenger, and Kik) or via direct message channels of certain social networking platforms (eg, Tumblr); in recent studies, a portion of Koko users were directly referred from a social media integration [20]. However, no previous evaluation of Koko’s services has focused entirely on investigating the acceptability and effectiveness of embedding mental health supports within a social networking platform.

Single-Session Interventions as Embedded Web-Based Support

Single-session interventions (SSIs)—brief, targeted interventions designed to be completed within 1 sitting or clinical interaction—provide an especially promising intervention format for reaching young people on the web [21]. Multiple large-scale studies have indicated that SSIs can create meaningful changes for key mental health outcomes. In a recent randomized controlled trial of adolescents (N=2452), a 20- to 30-minute web-based behavioral activation SSI (Project Action Brings Change [ABC]) outperformed a supportive therapy control program at reducing postintervention hopelessness and depressive symptoms 3 months later [22]. Another trial (N=565) found Project Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere (SAVE), a web-based 30-minute SSI targeting self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in teenagers, improved postintervention self-hatred, and desires to stop future self-harm, relative to an active control [23]. Taken together, substantive evidence suggests the efficacy of web-based SSIs in improving mental health outcomes among young people.

Despite the great potential of SSIs to increase access to mental health supports, little large-scale research has evaluated their acceptability and effectiveness when disseminated in web-based settings that young people already routinely access. One study evaluated the acceptability and preliminary utility of a free, open-access platform offering 3 web-based SSIs for youth [24]. After viewing paid advertisements on a social media platform (ie, Instagram), nearly 700 youths clicked on the advertisement and viewed the web-based platform within 6 months. The youths rated all 3 SSIs as acceptable, and analyses indicated significant pre- to postintervention reductions in hopelessness and self-hate among 187 SSI completers. However, to complete an SSI program, the youth had to be (1) aware of the open-access platform and (2) motivated to visit the platform on a separate, unfamiliar website and finish a 30-minute activity. Reducing friction (ie, points of difficulty) between individuals and their technology during key help-seeking thresholds may be particularly important for encouraging greater access to mental health supports on the web [25]. Rather than relying on individuals’ ability and motivation to seek external mental health resources in moments of heightened distress (eg, standalone web-based resources, crisis hotlines, and text lines), SSIs could provide accessible, in-the-moment anonymous supports for young people who are already embedded in popular social platforms.

Considerations for Intervention Design

SSIs designed for these web-based, embedded contexts should be streamlined to improve engagement while retaining their therapeutic value. Once disseminated in the real world, digital interventions often encounter issues with user engagement (ie, low uptake and low completion) [26-28]. Substantially reducing the time and effort required to complete web-based SSIs (eg, condensing content and reducing the number of writing prompts) may improve user engagement, particularly for SSIs delivered as in-the-moment supports at times of elevated distress. Determining which elements of SSIs to condense versus preserve presents a particular design challenge for the creation of SSIs embedded on the web.

Several intervention design principles, drawn from basic research in social psychology, education, and marketing [29], have been theorized to support the use of web-based SSIs for mental health: (1) using neuroscientific evidence to normalize youths’ experiences and boost message credibility; (2) centering youths’ expertise in their own lived experiences; (3) asking youths to share what they have learned with others, using their own words; and (4) providing testimonials from others experiencing similar and relevant challenges [21]. These core principles have been featured in much of the existing research evaluating web-based SSIs [22-24]. However, limited research to date has evaluated whether very brief, streamlined SSIs (ie, SSIs much shorter than 30 minutes) that retain these core principles may still provide some benefit as quick, free mental health supports embedded on the web.

This Study

As a majority of existing mental health treatments remain inaccessible, many young people seek mental health support via social platforms on the web. SSIs are uniquely well positioned for integration within web-based social platforms, providing free, brief, and anonymous mental health support options at scale. However, little research has formally evaluated the acceptability and effectiveness of very brief SSIs designed for this context. This study adapted 3 web-based SSIs (5-8 minutes) that were offered as Koko minicourses on Tumblr, a microblogging and social networking website with 135 million active users monthly [30]. The aims of this study were 2-fold: (1) to evaluate the acceptability of SSIs in this context via user data and acceptability ratings and (2) to assess short-term effectiveness of all 3 SSIs in improving key mental health outcomes (ie, hopelessness, self-hate, desire to discontinue self-harm) from before to after the SSI. Given the unique barriers to mental health treatment access faced by teenagers, the analyses were restricted to teenagers (ages 13-19 years) where possible. The results may inform continued efforts to increase access to free, anonymous, and timely mental health support options.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

For this study, we collected anonymous data exclusively from individuals on Tumblr—all of whom were introduced to the service by either (1) clicking on a featured advertisement from Tumblr (eg, “take control by taking this mood-boosting minicourse”) or (2) direct referral from the platform. As all data were part of a completely anonymous program evaluation, this study was deemed as nonhuman subjects research in consultation with the institutional review board at Stony Brook University. In addition, Koko’s privacy policy and terms of service acknowledge that anonymized data may be shared for research purposes.

Recruitment and Procedure

The direct referral pathway for each of the 3 SSIs was similar. Users who searched for mental health topics on Tumblr were shown an in-app overlay with links to various resources, such as The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. A set of over 1300 keywords and their derivations were used to detect terms such as “self-harm” or “depression” as well as slang and obfuscations, such as “sewer-slide” and “'s3lf h@rm.” In addition to links to crisis lines, users were also sent a direct message from Koko through the Tumblr direct message channel. Specifically, they were sent the following automated message from a chatbot called “Kokobot”:

Hi! I’m Kokobot [wave emoji]. I’m working with Tumblr to connect people who are interested in mental health topics. Type “hi” to get started...

Next, users were onboarded to the service and asked to describe a recent negative situation that they have been facing, along with any associated negative thoughts. From there, a set of text-based classifiers for mental health [20,31] categorized the user’s posts and directed them to one of several resources, including peer support, crisis lines, and SSIs. Users could also access any of these services from a main menu at any point while using the platform. Users whose text descriptions were flagged by a crisis model were asked to specify whether their current struggles were related to suicidal thoughts, abuse, eating disorders, or self-harm. If a user disclosed that they were struggling with self-harm, they were shown crisis lines from around the world as well as a link to Project SAVE.

The 3 SSIs were initially introduced as Koko minicourses at 3 separate times: March 2021 (Project ABC), June 2021 (REFRAME), and July 2021 (Project SAVE). Across all 3 SSIs, the data for this study were collected through February 2022. Preintervention data were collected immediately before beginning each SSI (ie, each Koko minicourse), and postintervention data were collected immediately following the completion of a program.

SSI Programs

Project ABC Single-Session Intervention

Project ABC minicourse was a briefer 5- to 8-minute version of the original 20- to 30-minute Project ABC SSI evaluated in earlier randomized trial research [22]. As with the full-length program, the abbreviated Project ABC SSI used principles of behavioral activation, encouraging individuals to “take action” and engage in pleasurable behaviors that align with personal values to boost mood and build self-efficacy. Similar to the original SSI, the brief minicourse involved the following components: (1) psychoeducation, describing how taking values-based actions can boost mood over time; (2) values assessment, where individuals identify a top value for them (eg, academics, friendships, hobbies, family, or staying active); (3) “action plan” exercise, where individuals develop a personalized plan for engaging in meaningful activities of their choice; (4) roadblock exercise designed to identify real-life obstacles and how to address them; and (5) writing prompts, where individuals can share what they have learned with other Koko users. This shortened version of the Project ABC SSI contained condensed intervention content, fewer writing prompts, and greater emphasis on multiple-choice, interactive options, relative to the original 30-minute program.

Project SAVE Single-Session Intervention

Before disseminating as a Koko minicourse, an abbreviated (8-minute) version of the Project SAVE SSI was adapted from an original 30-minute program [32]. Project SAVE was designed to reduce the use of self-harm behaviors to cope with high emotional distress, especially in the context of self-hatred or desires to punish oneself [33]. Similar to the original SSI, the 8-minute version of Project SAVE included evidence-based techniques that are common in cognitive behavior therapies (eg, psychoeducation and secondary distress tolerance skills). Specifically, Project SAVE included four key components: (1) information about how changing actions (eg, reducing self-harm behavior, being kinder to yourself) can change feelings and thoughts for the better; (2) statistics and testimonials from other teenagers with lived experiences of coping with self-hatred or self-harm; (3) alternative coping strategies to use in place of self-harm; and (4) offering advice to others using Koko based on what they learned. Compared with the original, the shortened Project SAVE SSI contained condensed material, fewer writing exercises, and more multiple-choice, interactive options.

The REFRAME Single-Session Intervention

The REFRAME SSI (5 minutes) teaches cognitive reappraisal, an emotion regulatory strategy that involves modifying one’s interpretation of stressful situations [34]. A recent multicountry study with 21,644 individuals found that a brief web-based training on cognitive reappraisal reduced negative emotions and increased positive emotions about COVID-19–related stressors [35]. The REFRAME SSI on Koko included similar components, but it did not specifically target COVID-19–related stressors and it did not distinguish between multiple reappraisal strategies (eg, reconstrual vs repurposing). It included (1) a brief introduction to cognitive reappraisal; (2) a simplified description of its neural correlates; (3) practice examples with vignettes taken from the Koko peer support platform; and (4) a set of brief prompts to help users engage positive reappraisals in their own lives (eg, “This could get better because...”; “This isn’t 100% my fault because...”). Users were also taught how to practice this skill on the Koko peer support platform and that helping others reappraise may confer positive psychological outcomes [36,37].

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information (age, gender, and race and ethnicity) was collected as part of the preintervention measures for individuals completing Project SAVE.

Hopelessness

The Beck Hopelessness Scale-4 is a brief and reliable measure used to assess hopelessness in young people [38,39]. At pre- and postintervention time points for the Project ABC and REFRAME SSIs, responders indicated their agreement “right now, in the present moment” with each of 4 statements (eg, “I feel that my future is hopeless and things will not improve”) on a 4-point Likert scale (1=“absolutely disagree”; 4=“absolutely agree”). Hopelessness scores for each person (4-item average) ranged from 1 to 4, with higher values indicating greater hopelessness. Internal consistency was Cronbach α=.84 and Cronbach α=.89 for pre- and post-Project ABC time points, and α=.81 and Cronbach α=.87 for pre- and post-REFRAME SSI time points, respectively.

Self-hate

The Self-Hate Scale is a reliable 7-item measure used to assess self-hatred in young people [24,40]. At pre- and postintervention time points for the Project SAVE SSI, respondents indicated how true each statement (eg, “I hate myself”) is for them, “right now, in the present moment,” on a 7-point Likert scale (1=“not at all true for me”; 4=“somewhat true for me”; 7=“true for me”). The self-hate scores for each person (7-item average) ranged from 1 to 7, with higher values indicating greater self-hate. Internal consistency was Cronbach α=.90 and Cronbach α=.94 for pre- and post-Project SAVE SSI time points, respectively.

Desire to Discontinue Self-harm

Desire to discontinue self-harm behavior was indexed using a single item adapted from the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview–Revised [23,41]. Individuals were asked, “How much do you want to stop purposefully hurting yourself without wanting to die?” and told to rate their answer on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“I don’t want to stop at all”; 5=“I definitely want to stop”). A sixth option (eg, “I have stopped engaging in these behaviors”) was available for individuals not currently engaging in self-harm behaviors. Data for these individuals were not included in the analyses evaluating pre- to post-SSI changes in this outcome.

SSI Feedback

After completing all 3 SSIs, users were prompted to provide a quantitative “star rating” of the program, from 1 to 5 stars, where higher star values indicate higher ratings or more positive feedback. In addition, after the intervention, all individuals were asked if they would like to provide qualitative feedback via an optional writing prompt (eg, “Do you have any feedback for us?”).

Statistical Analysis

Power

Previous web-based SSI research suggests small to large within-group effect sizes for key outcomes (including hopelessness and self-hatred) using more naturalistic study designs (ie, not randomized controlled trials) [24]. Thus, we estimated our statistical power to detect a small within-group effect (Cohen d=0.20) using a paired 2-tailed t test in the smallest of the 3 samples (ie, REFRAME, n=768 pairs).

Data Exclusion

We assessed the total number of views, starts, and completions for each SSI, as well as item-level drop-off data within each SSI, to describe broad usage patterns without excluding any data. Demographic and outcome data were only recorded and made available once individuals advanced through to the end of a program and clicked “submit.” All pre-post analyses, star ratings, and qualitative data were therefore conducted and reported within program “completers” (ie, individuals who completed an SSI). In addition, where demographic data were available (Project SAVE SSI data), we restricted our analysis to teenagers (ie, excluding individuals who reported ages outside of 13-19 years). As Project SAVE was designed for teenagers engaging in self-harm, only individuals who self-disclosed recently engaging in self-harm (via the Koko onboarding pathways described earlier in this section) were directed to complete this program.

Usage Patterns and SSI Feedback

For each SSI, we evaluated usage patterns and feedback, including the number of people who viewed (ie, opened the first page of the program), started (ie, advanced past the first page), completed (ie, advanced through the entire program and beyond the questions), and provided “star ratings” (ie, quantitative ranking of 1-5 stars, with higher stars reflecting a higher rating) for each SSI. In addition, we calculated the program completion rates (percentage completed out of those who started) and average star ratings for each SSI. To illustrate the types of qualitative feedback each SSI received, we extracted specific examples of positive and negative feedback (see the Results section).

Aggregate-level data were available for views and user dropout, for every page within each SSI, among the entire sample (ie, without focusing solely on program completers). We reported these results by plotting the percentage dropout from the number of views for each page within each SSI.

Evaluating Pre-Post Changes

We evaluated pre- to postintervention changes for 4 outcomes: hopelessness (via two separate tests, 1 for Project ABC and 1 for REFRAME) as well as self-hate and desire to discontinue self-harm (Project SAVE only). After checking appropriate assumptions (ie, verifying that pre-post difference scores for each outcome were approximately normally distributed) [42], we performed 2-tailed, paired t tests across all outcomes for all programs. We calculated Cohen dz for paired t tests using t values, sample sizes, and the Measure of the Effect package in R (version 4.0.0) [43] to evaluate the magnitude of within-group changes for each outcome. For outcomes where difference scores were not normally distributed, we completed an additional sensitivity analysis using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test to evaluate within-group changes from before to after the intervention [44]. We applied a false discovery rate correction to all 4 P values to reduce the likelihood of false positives [45]. Thus, we interpreted the results for each outcome as significant if the false discovery rate–corrected P values were <.05. All analysis code and deidentified data for this study have been made publicly available [46].

Results

Sample Characteristics

As Koko provides anonymous mental health support, individuals are not required to provide potentially identifiable demographic information (eg, age, gender, and race and ethnicity) to complete minicourses. Specific demographic information for this study (age, gender, and race and ethnicity) was only available for the Project SAVE SSI, as this minicourse was introduced to Koko after Project ABC and REFRAME SSIs had been introduced. For the Project SAVE minicourse, individuals were given the option (but were not required) to report demographic information about themselves.

The Project SAVE analyses excluded individuals who were not teenagers between the ages of 13 and 19 years, resulting in a final sample of 1194 individuals (72.28% of the total Project SAVE data). Among this group, the average age of the individuals who completed Project SAVE was 15.71 (SD 1.83) years. The top three most commonly endorsed gender identities were female (419/1194, 35.09%), nonbinary (189/1194, 15.83%), and not sure (98/1194, 8.21%). The top three most commonly endorsed racial or ethnic identities were White (607/1194, 50.84%); Asian (172/1194, 14.41%); and Hispanic or Latinx (112/1194, 9.38%). Table 1 presents complete details on participant demographics.

Table 1.

Gender identity and race and ethnicity for Project Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere (N=1194).

| Demographics | Values, n (%) | |

| Gender | ||

|

|

Agender | 35 (2.93) |

|

|

Androgynous | 13 (1.09) |

|

|

Female | 419 (35.09) |

|

|

Female to male transgender | 74 (6.20) |

|

|

Gender expansive | 15 (1.26) |

|

|

Gender identity not listed | 18 (1.51) |

|

|

Gender information missing | 219 (18.34) |

|

|

Intersex | 3 (0.25) |

|

|

Male | 27 (2.26) |

|

|

Male to female transgender | 2 (0.17) |

|

|

Nonbinary | 189 (15.83) |

|

|

Not sure | 98 (8.21) |

|

|

Prefer not to say | 26 (2.18) |

|

|

Transfeminine gender | 2 (0.17) |

|

|

Trans man | 10 (0.84) |

|

|

Transmasculine gender | 44 (3.69) |

|

|

Transgender | 15 (1.26) |

|

|

Two-spirited | 2 (0.17) |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||

|

|

Asian | 172 (14.41) |

|

|

Black or African American | 66 (5.53) |

|

|

Hispanic or Latinx | 112 (9.38) |

|

|

Native American or Alaska Native | 23 (1.93) |

|

|

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 12 (1.01) |

|

|

White | 607 (50.84) |

|

|

Prefer not to answer | 125 (10.47) |

aIndividuals could select multiple racial and ethnic identities.

Statistical Analysis

Power

Power analyses indicated that we had 99% power to detect a small effect size (Cohen d=0.20) using a 2-tailed paired t test in the smallest of the 3 current samples (REFRAME, n=768 pairs).

Usage Patterns and SSI Feedback

Project ABC

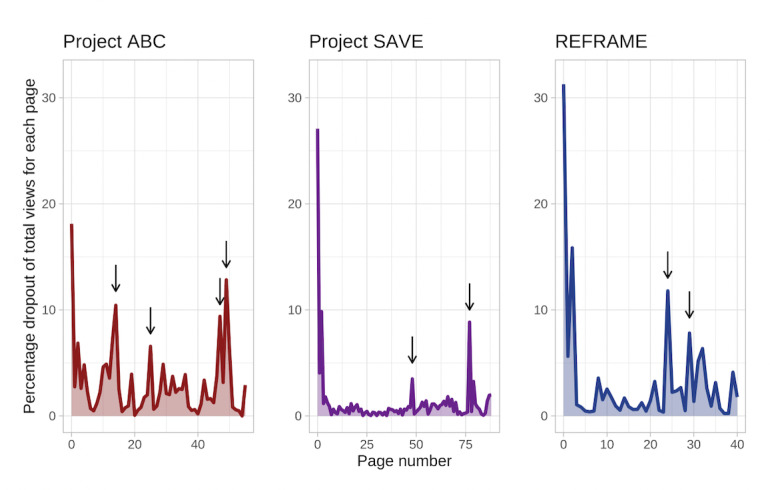

Project ABC was viewed 17,620 times, started 14,434 times, and completed 3679 times—with a 25.49% (3679/14,434) completion rate among starters across the 12-month study period. Among the Project ABC completers, 3412 (92.74%) provided a star rating with an average star rating of 4.27 (SD 0.94; median 5) stars. In total, 1217 (33.08%) provided qualitative feedback on Project ABC (see Table 2 for examples of user feedback). The dropout percent of the number of views for each page for all 3 SSIs is plotted in Figure 1. Notably, high levels of dropout (relative to page views, 7%-13%) consistently occurred on pages where Project ABC users were asked to respond to a writing prompt.

Table 2.

Examples of positive and critical feedback for all single-session interventions (SSIs).

| SSI | Positive feedback | Critical feedback |

| ABCa | “Thanks y’all! been dealing w some serious mental health issues and having places to remind me of my agency and joy is really helpful.” | “Despite the great intentions and work I think there is situations that are very complicated and having this intermediate bot, very few info of the person you are helping it’s too simplistic.” |

|

|

“this was really really helpful and i’m seriously going to try my goal/plan. I also feel awake and motivated enough to study. I’d love to see more in the future.” | “This helped me see get through my rain cloud but now I kinda feel stressed.” |

|

|

“Hey, this was surprisingly well done. I went in expecting it would be terrible. But you’re making mental health a really approachable topic for people. Thanks for working on reaching out to others. I’d love to see you continue with these mini-courses.” | “This is a good idea, but only works for the things one has control over. If you are terminally ill, just lost a loved one or in another uncontrollable challenge, none of these can help.” |

| REFRAMEb | “This is such a great way to de-stress, I mean re-frame your stress, it’s definitely a bit helpful.” | “Less simplification” |

|

|

“I decided to pick up my phone and do this while I was procrastinating. It’s so crazy how this seemingly small task changed my perspective.” | “i think that one of the problems i see is that this requires people to be more specific and there isn’t a sense of connection.” |

|

|

“I love this so much!! It actually made me feel better, which I didn’t think it would! Thank you <3.” | “Please include physical stress reducers, as well. It is difficult to focus on reducing stress when I can’t properly string thoughts together.” |

| SAVEc | “This is amazing. My thoughts of self-harm faded a bit, and prompted me to do the things alternative to when I have self-hate thoughts.” | “It would’ve been more helpful if reasons for self-harm outside of self-hatred were explored. I’m currently dealing with external circumstances that are overwhelming me and my response is to harm myself. It feels like the only way to release my emotions.” |

|

|

“This is the most convincing thing I’ve ever heard as to why not to self harm. Thank you so much this is so helpful.” | “I have dealed with this so long that there wasn’t really anything new to me, so it really didn’t help.” |

|

|

“Thank you. This course has definitely calmed me down when I was having a breakdown and thinking of hurting myself.” | “Talk about slowly building up to recovery instead of just jumping right in. Talk about how to deal with intense emotions and more.” |

aProject Action Brings Change (ABC) SSI.

bREFRAME SSI.

cProject Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere (SAVE) SSI.

Figure 1.

Percentage dropout on each page of all 3 single-session interventions (SSIs), out of the number of individuals who viewed that page. Arrows reflect points where writing prompts were introduced, in each of the 3 SSIs. Spikes in dropout tended to occur after initially opening each SSI, as well as on pages requesting written responses. ABC: Action Brings Change; REFRAME; SAVE: Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere.

Finally, Project ABC received far more views, starts, and completions than either of the other two SSI programs (4065 and 2174 views for Project SAVE and REFRAME, respectively), as Tumblr advertised the Project ABC SSI as a featured minicourse between December 2021 and February 2022, resulting in higher traffic to this SSI.

Project SAVE

In 12 months, Project SAVE was viewed 4065 times, started 2961 times, and completed 1652 times; 55.79% (1652/2961) of those who started Project SAVE completed it. After excluding individuals with ages outside our desired range (13-19 years), 1194 observations remained for analysis. Among those who completed the minicourse, 954 (79.90%) provided a star rating for Project SAVE, with an average rating of 4.22 (SD 0.97; median 5) stars. A total of 209 (17.50%) participants provided qualitative feedback on Project SAVE (Table 2). Similar to the Project ABC SSI, Project SAVE observed higher dropout rates (relative to page views, 3%-9%) on pages where users were asked to enter a written response (Figure 1).

REFRAME

REFRAME was viewed 2174 times, started 1498 times, and completed 848 times within 12 months (848/1498, 56.60% completion rate among the starters). Among REFRAME completers, 732 (86.32%) provided a star rating for the REFRAME SSI, with an average rating of 4.31 (SD 0.93; median 5) stars; 246 (29.01%) provided qualitative feedback on the REFRAME minicourse (Table 2). Consistent with dropout patterns for the other 2 SSIs, REFRAME observed higher dropout rates (relative to page views, 8%-12%) on pages requesting writing from users.

Evaluating Pre-Post Changes

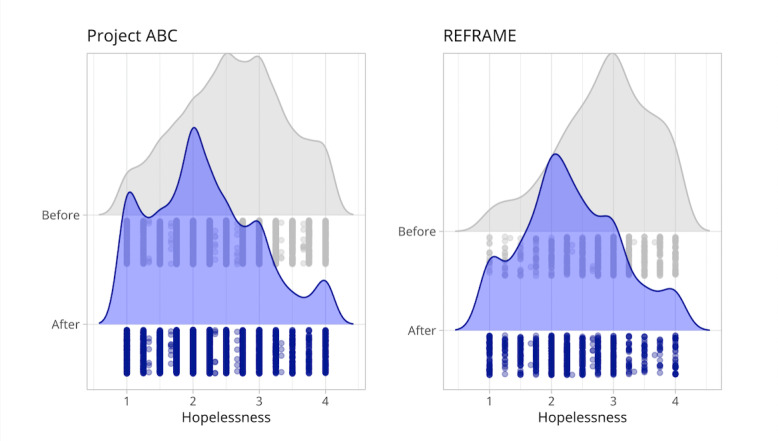

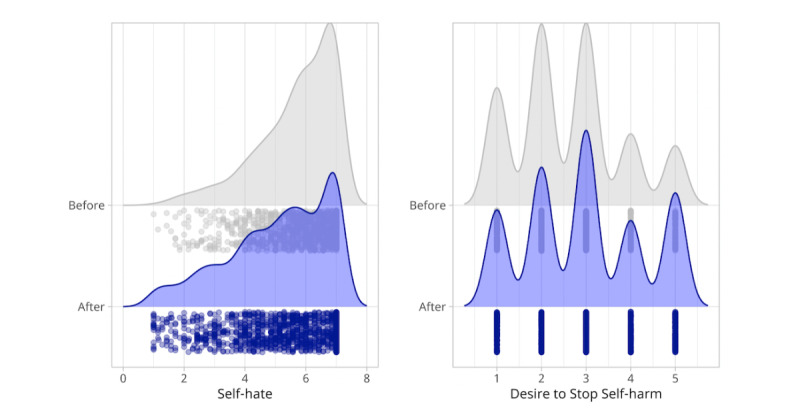

Among individuals who completed Project ABC, hopelessness significantly decreased from before to after the SSI (t3,565=−48.48, P<.001). Similarly, individuals who completed the REFRAME SSI reported significant reductions in hopelessness from before to after the intervention (t767=−24.41, P<.001). Project SAVE completers reported significant pre- to postintervention reductions in self-hate (t1,007=−21.30, P<.001) and an increase in desire to discontinue self-harm (t839=11.48, P<.001). All the means, SDs, and within-group effect sizes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means, SDs, and effect sizes for all single-session intervention (SSI) outcomes.

| Outcome and SSI | Before the SSI, mean (SD) | After the SSI, mean (SD) | Cohen dz (95% CI) | |

| Hopelessness | ||||

|

|

ABCa | 2.60 (0.78) | 2.16 (0.80) | −0.81 (−0.85 to −0.77) |

|

|

REFRAMEb | 2.86 (0.74) | 2.31 (0.78) | −0.88 (−0.96 to −0.80) |

| Self-hate | ||||

|

|

SAVEc | 5.69 (1.27) | 5.07 (1.64) | −0.67 (−0.74 to −0.60) |

| Desire to stop harmd | ||||

|

|

SAVE | 2.63 (1.20) | 2.97 (1.32) | 0.40 (0.33 to 0.47) |

aProject Action Brings Change (ABC) SSI.

bREFRAME SSI.

cProject Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere (SAVE) SSI.

dDesire to discontinue self-harm behavior.

In addition, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed as sensitivity analyses for all outcomes due to the relatively nonnormal distributions of difference scores. For all outcomes, results were consistent with t test analyses, indicating significant pre-post reductions in hopelessness (P<.001; Project ABC and REFRAME) and self-hate (P<.001; Project SAVE), as well as a significant increase in desire to discontinue self-harm (P<.001; Project SAVE) from before to after the intervention. Distributions for all outcomes at pre- and post-SSI time points are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Hopelessness ratings before and after the Project Action Brings Change (ABC) single-session intervention (SSI; left) and before and after the REFRAME SSI (right). Higher scores reflect higher levels of hopelessness.

Figure 3.

Self-hate ratings before and after the Project Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere single-session intervention (left), where higher scores reflect higher levels of self-hatred. (Right) Desire to stop future self-harm behavior, where higher scores reflect higher desire to stop future self-harm.

Discussion

Principal Findings

Within 12 months, 3 very brief (5-8 minutes) web-based SSIs were viewed >18,800 times and completed >6100 times. Offered as Koko minicourses and embedded within a popular social platform, all 3 SSIs received high-quality ratings (average ratings >4 out of 5 stars). Of the participants who started an SSI, between 25% and 57% of them completed one. Among those who completed Project ABC and REFRAME minicourses, individuals reported a decrease in hopelessness from before to after the SSI. For those who completed Project SAVE, individuals reported decreased self-hatred and increased desire to stop future self-harm behavior from before to after the intervention. This study represents a real-world evaluation of the acceptability and short-term utility of web-based SSIs as very brief, anonymous, “in-the-moment” mental health supports that can be integrated within major social platforms such as Tumblr.

Comparison With Prior Work

Consistent with existing research on web-based SSIs [24], all 3 interventions were (1) rated as acceptable by users and (2) associated with improvements across primary outcomes. Furthermore, despite reducing intervention length by nearly 75%, effect sizes for these 5- to 8-minute SSIs were remarkably similar to effect sizes for SSIs designed to last 30 minutes (Cohen dz =0.71 vs 0.81 (hopelessness) and Cohen dz =0.61 vs 0.67 (self-hate) for full and abbreviated SSIs, respectively) [24]. These results support a growing body of evidence that suggests even extremely brief digital interventions may improve clinically relevant outcomes [20,47].

One possible reason for the relative similarity of postintervention effect sizes observed in this study (5-8–minute SSIs) versus within-group effects in earlier randomized trials (30-minute SSIs) [22,23] might be the shared design features and principles across the “brief” and “very brief” versions of these interventions. Given that these core principles have been featured in all versions of these SSIs to date, it is possible that these common principles are more important than the exact length of the SSI. Future research should formally evaluate this possibility in a head-to-head trial by comparing SSIs of various lengths.

Our results may also indicate the real-world utility of these very brief web-based SSIs. Naturalistic study designs similar to that used in this study are crucial for evaluating acceptability and utility among web-based SSIs, as randomized trials overestimate user engagement levels for unguided, digital mental health interventions—often producing usage rates that are 4 times greater than rates observed in real-world settings [27]. Once these interventions are disseminated outside of randomized trials, a small minority of individuals (0.5%-28.6%) complete all content [28]. Therefore, relative to real-world completion rates of other digital self-help interventions for mental health, completion rates for the 3 SSIs tested in this study (25%-57%) were extraordinarily high.

Low real-world completion rates for self-help digital interventions, especially relative to guided digital supports [26,48,49], are unsurprising; unguided supports require substantial emotional and mental bandwidth (eg, energy, sustained attention, and motivation) to find and engage with an unguided mental health support tool at the very moments when these capacities may be at their lowest (eg, when experiencing elevated distress). Our study sought to minimize the bandwidth necessary to engage with 3 single-session, unguided supports by (1) dramatically reducing their length and (2) bringing these interventions to web-based spaces where people already are. Future research should explicitly assess whether these strategies improve completion rates across other unguided digital mental health supports.

Embedding SSIs within a popular social platform (Tumblr) also likely increased the visibility and uptake of these SSIs. For example, after 6 months of recruitment using paid advertising and leveraging substantial media coverage, 1 study found that 700 youths viewed an open-access, web-based mental health platform featuring 3 SSIs [24]. The 3 SSIs in this study received a combined ≥18,800 views within 12 months—nearly 6240 of which were views of interventions that were never featured in a Tumblr-based advertisement (Project SAVE and REFRAME). These numbers suggest considerable interest in accessible, anonymous, “in-the-moment” support options, as well as the potential to sustainably offer these supports at high scale and relatively low cost.

Notably, existing research identifies safety as a primary ethical concern for researchers and stakeholders interested in using digital mental health tools among youth [50]; many digital resources lack evidence or clinical validation and others may not provide sufficient protection for sensitive user data. By using SSIs that have previously been evaluated in rigorous randomized trial research [22,23] and by collecting anonymous pre- and post-SSI user data, in this study, we aimed to mitigate these common concerns. Thus, calls for clearer guidelines for safety and quality in mental health apps [51] should also be accompanied by clearer guidelines, both for academic- and industry-based program developers and researchers, on how to responsibly and ethically disseminate mental health resources via partnerships with social networking platforms.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Although randomized trial research overestimates user engagement for digital interventions [27], it constitutes much of the existing research on web-based SSIs to date [22,23,52]. Therefore, the naturalistic design of this study provides a valuable, more accurate estimate of the potential for web-based SSIs to offer mental health supports at scale. Koko’s partnership with Tumblr also made it possible to offer anonymous, “in-the-moment” support for people seeking mental health–related content within the platform, rather than requiring individuals to search for external resources. Finally, we conducted a fine-grained analysis of usage data (ie, dropout) going item by item for each SSI. It was especially valuable to recognize high levels of user dropout relative to page views (3%-13%) on pages requesting written responses. Further studies should seek to understand patterns in user dropout and how they may inform digital intervention design. In addition, future evaluations may also want to expand upon this study by conducting smaller-scale usability testing [53] and research explicitly designed for the in-depth analysis of rich qualitative user feedback [54].

In addition to the aforementioned strengths, this study has some limitations. First, demographic information was not available for all individuals included in this study. Demographic information that was available from 1 of the 3 SSIs indicated substantial missing data (several users reported skipping demographic items to ensure they could not be identified). Black, Hispanic, and Asian youths consistently access mental health treatment at lower rates than their non-Hispanic White peers [55,56], yet up to 90% of youths in mental health clinical trials are White [57,58]. Digital interventions provide one possible avenue toward reducing disparities in access to mental health resources among racial and ethnic minority populations [59,60]; a vast majority of adolescents in the United States have internet access via either smartphones or desktops or laptops (88% and 95%, respectively) [61]. While there are disparities in broadband access by socioeconomic status, geographic region, educational attainment, and race and ethnicity, some evidence suggests that these gaps in access may be decreasing [62]. Should SSIs hope to provide truly accessible and equitable mental health supports, they must be accompanied with consistent evaluations of who has access to them, with researchers actively working to prevent further (or exacerbated) inequity via a new treatment modality [60].

In addition, as is often the case in web-based mental health support research [24,63,64], cisgender boys were underrepresented in this sample. Given unique barriers to seeking mental health treatments faced by cisgender boys and young men (eg, internalized masculine gender norms, such as “toughness”; elevated mental health stigma) [65,66], future mixed methods research may want to evaluate whether boys view SSIs as a less stigmatizing or more approachable mental health support option.

Finally, given that this study represents an unmasked evaluation of within-group intervention effects in a completers-only sample, our ability to draw causal inferences was limited. For example, those who completed an SSI may have provided more positive star ratings for the programs than those who exited before finishing the program. However, 2 of the 3 SSIs featured in this study have demonstrated positive effects on identical outcomes in large-scale, triple-masked, and randomized research [22,23]. SSIs have shown considerable promise in multiple studies and study designs.

Conclusions

Very brief SSIs (5-8 minutes) can be embedded within web-based social platforms as anonymous, in-the-moment mental health supports capable of reaching many individuals within months. Among those who complete these SSIs, individuals generally rate them as acceptable, and pre-post evaluations suggest that they may be helpful in reducing hopelessness and self-hate as well as in increasing the desire to stop self-harm. These pre-post findings, combined with results of earlier randomized trial research, suggest that SSIs delivered in this context may be a sustainable approach for providing the much-needed mental health resources, particularly for teenagers who may not have access to other mental health supports. Considering the substantial unmet need for mental health care among teenagers in the United States [67], SSIs may provide a valuable and complementary source of mental health support among a broader ecosystem of mental health treatment options (eg, school- and community-based programs, mental health screening, and gatekeeper training), all of which are necessary for reducing mental illness at scale.

Acknowledgments

JLS received funding from the National Institute of Health Office of the Director (DP5OD028123), National Institute of Mental Health (R43MH128075), National Science Foundation (2141710), Health Research and Services Association (U3NHP45406-01-00), Upswing Fund for Adolescent Mental Health, Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, and the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation.

MLD received funding from the Graduate Council Fellowship at Stony Brook University and has previously received research funding from the Psi Chi International Honors Society and the University of Denver Faculty Research Fund.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Action Brings Change

- SAVE

Stop Adolescent Violence Everywhere

- SSI

single-session intervention

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: JLS, RM, and MLD conceptualized the project, contributed to the study design, and developed the original versions of the single-session interventions. RM adapted the original intervention materials for integration into the Koko. MLD performed data analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: MLD receives book royalties from New Harbinger and funding from the Graduate Council Fellowship at Stony Brook University. She has previously received research funding from Psi Chi International Honors Society and University of Denver Faculty Research Fund. RM is the cofounder and chief executive officer of Koko, a nonprofit organization that receives financial aid from industry partners, private donors, and Hopelab Ventures. He also serves as a scientific advisor for Homecoming, a digital platform to help support psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. JLS serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Walden Wise and the Clinical Advisory Board for Koko; is the cofounder and codirector of Single Session Support Solutions, Inc.

References

- 1.Brown A, Rice SM, Rickwood DJ, Parker AG. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;8(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/appy.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, Wells KB, Pincus HA, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011 Aug;41(8):1751–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21134315 .S0033291710002291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Crum RM, Martins SS, Kaufmann CN, Strain EC, Mojtabai R. Service use and barriers to mental health care among adults with major depression and comorbid substance dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 Sep 01;64(9):863–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200289. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23728427 .1693284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hom MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Evaluating factors and interventions that influence help-seeking and mental health service utilization among suicidal individuals: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015 Aug;40:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.006.S0272-7358(15)00076-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox KR, Bettis AH, Burke TA, Hart EA, Wang SB. Exploring adolescent experiences with disclosing self-injurious thoughts and behaviors across settings. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022 May;50(5):669–81. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00878-x.10.1007/s10802-021-00878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd RC, Butler L, Benton TD. Understanding adolescents' experiences with depression and behavioral health treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2018 Jan;45(1):105–11. doi: 10.1007/s11414-017-9558-7.10.1007/s11414-017-9558-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breland DJ, McCarty CA, Zhou C, McCauley E, Rockhill C, Katon W, Richardson LP. Determinants of mental health service use among depressed adolescents. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.12.003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24417955 .S0163-8343(13)00368-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickwood DJ, Mazzer KR, Telford NR. Social influences on seeking help from mental health services, in-person and online, during adolescence and young adulthood. BMC Psychiatry. 2015 Mar 07;15:40. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0429-6. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-015-0429-6 .10.1186/s12888-015-0429-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pretorius C, Chambers D, Coyle D. Young people's online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: systematic narrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Nov 19;21(11):e13873. doi: 10.2196/13873. https://www.jmir.org/2019/11/e13873/ v21i11e13873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coping with COVID-19: how young people use digital media to manage their mental health. Common Sense Media. 2021. Mar 15, [2022-06-29]. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/coping-with-covid19-how-young-people-use-digital-media-to-manage-their-mental-health .

- 11.Wetterlin FM, Mar MY, Neilson EK, Werker GR, Krausz M. eMental health experiences and expectations: a survey of youths' Web-based resource preferences in Canada. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Dec 17;16(12):e293. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3526. https://www.jmir.org/2014/12/e293/ v16i12e293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pretorius C, Chambers D, Cowan B, Coyle D. Young people seeking help online for mental health: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Ment Health. 2019 Aug 26;6(8):e13524. doi: 10.2196/13524. https://mental.jmir.org/2019/8/e13524/ v6i8e13524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fish JN, McInroy LB, Paceley MS, Williams ND, Henderson S, Levine DS, Edsall RN. "I'm kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now": LGBTQ youths' experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Sep;67(3):450–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.002. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32591304 .S1054-139X(20)30311-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horgan A, Sweeney J. Young students' use of the Internet for mental health information and support. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010 Mar;17(2):117–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01497.x.JPM1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns JM, Birrell E, Bismark M, Pirkis J, Davenport TA, Hickie IB, Weinberg MK, Ellis LA. The role of technology in Australian youth mental health reform. Aust Health Rev. 2016 Nov;40(5):584–90. doi: 10.1071/AH15115.AH15115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams AJ, Nielsen E, Coulson NS. "They aren't all like that": perceptions of clinical services, as told by self-harm online communities. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(13-14):2164–77. doi: 10.1177/1359105318788403. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105318788403?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones R, Sharkey S, Ford T, Emmens T, Hewis E, Smithson J, Sheaves B, Owens C. Online discussion forums for young people who self-harm: user views. Psychiatrist. 2018 Jan 02;35(10):364–8. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.110.033449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris RR, Schueller SM, Picard RW. Efficacy of a Web-based, crowdsourced peer-to-peer cognitive reappraisal platform for depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Mar 30;17(3):e72. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4167. https://www.jmir.org/2015/3/e72/ v17i3e72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doré BP, Morris RR. Linguistic synchrony predicts the immediate and lasting impact of text-based emotional support. Psychol Sci. 2018 Oct;29(10):1716–23. doi: 10.1177/0956797618779971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaroszewski AC, Morris RR, Nock MK. Randomized controlled trial of an online machine learning-driven risk assessment and intervention platform for increasing the use of crisis services. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019 Apr;87(4):370–9. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000389.2019-14424-004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schleider JL, Dobias ML, Sung JY, Mullarkey MC. Future directions in single-session youth mental health interventions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2020;49(2):264–78. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1683852. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31799863 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schleider JL, Mullarkey MC, Fox KR, Dobias ML, Shroff A, Hart EA, Roulston CA. A randomized trial of online single-session interventions for adolescent depression during COVID-19. Nat Hum Behav. 2022 Feb;6(2):258–68. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01235-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34887544 .10.1038/s41562-021-01235-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobias ML, Schleider JL, Jans L, Fox KR. An online, single-session intervention for adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: results from a randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. 2021 Dec;147:103983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103983.S0005-7967(21)00182-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schleider JL, Dobias M, Sung J, Mumper E, Mullarkey MC. Acceptability and utility of an open-access, online single-session intervention platform for adolescent mental health. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Jun 30;7(6):e20513. doi: 10.2196/20513. https://mental.jmir.org/2020/6/e20513/ v7i6e20513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ash J, Anderson B, Gordon R, Langley P. Digital interface design and power: friction, threshold, transition. Environ Plan D. 2018 Apr 13;36(6):1136–53. doi: 10.1177/0263775818767426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torous J, Nicholas J, Larsen ME, Firth J, Christensen H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018 Aug;21(3):116–9. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102891.eb-2018-102891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumel A, Edan S, Kane JM. Is there a trial bias impacting user engagement with unguided e-mental health interventions? A systematic comparison of published reports and real-world usage of the same programs. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Nov 25;9(6):1020–33. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz147.5613435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming T, Bavin L, Lucassen M, Stasiak K, Hopkins S, Merry S. Beyond the trial: systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. J Med Internet Res. 2018 Jun 06;20(6):e199. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9275. https://www.jmir.org/2018/6/e199/ v20i6e199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewin GW. Constructs in field theory. In: Lewin K, editor. Resolving Social Conflicts and Field Theory in Social Science. Washington, D.C., United States: American Psychological Association; 1944. pp. 191–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Press information. Tumblr. [2022-06-29]. https://www.tumblr.com/press .

- 31.Kshirsagar R, Morris R, Bowman S. Detecting and explaining crisis. Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology — From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality; CLPsych '17; August 3, 2017; Vancouver, BC, Canada. 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobias ML, Schleider JL, Fox KR. Project SAVE: stop adolescent violence everywhere. Open Science Framework. 2020. [2022-06-29]. https://osf.io/vguf4/

- 33.Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007 Mar;27(2):226–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002.S0272-7358(06)00096-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. Emotion. 2020 Feb;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/emo0000703.2020-03346-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang K, Goldenberg A, Dorison CA, Miller JK, Uusberg A, Lerner JS, Gross JJ, Agesin BB, Bernardo M, Campos O, Eudave L, Grzech K, Ozery DH, Jackson EA, Garcia EO, Drexler SM, Jurković AP, Rana K, Wilson JP, Antoniadi M, Desai K, Gialitaki Z, Kushnir E, Nadif K, Bravo ON, Nauman R, Oosterlinck M, Pantazi M, Pilecka N, Szabelska A, van Steenkiste IM, Filip K, Bozdoc AI, Marcu GM, Agadullina E, Adamkovič M, Roczniewska M, Reyna C, Kassianos AP, Westerlund M, Ahlgren L, Pöntinen S, Adetula GA, Dursun P, Arinze AI, Arinze NC, Ogbonnaya CE, Ndukaihe IL, Dalgar I, Akkas H, Macapagal PM, Lewis S, Metin-Orta I, Foroni F, Willis M, Santos AC, Mokady A, Reggev N, Kurfali MA, Vasilev MR, Nock NL, Parzuchowski M, Espinoza Barría MF, Vranka M, Kohlová MB, Ropovik I, Harutyunyan M, Wang C, Yao E, Becker M, Manunta E, Kaminski G, Marko D, Evans K, Lewis DM, Findor A, Landry AT, Aruta JJ, Ortiz MS, Vally Z, Pronizius E, Voracek M, Lamm C, Grinberg M, Li R, Valentova JV, Mioni G, Cellini N, Chen S, Zickfeld J, Moon K, Azab H, Levy N, Karababa A, Beaudry JL, Boucher L, Collins WM, Todsen AL, van Schie K, Vintr J, Bavolar J, Kaliska L, Križanić V, Samojlenko L, Pourafshari R, Geiger SJ, Beitner J, Warmelink L, Ross RM, Stephen ID, Hostler TJ, Azouaghe S, McCarthy R, Szala A, Grano C, Solorzano CS, Anjum G, Jimenez-Leal W, Bradford M, Pérez LC, Cruz Vásquez JE, Galindo-Caballero OJ, Vargas-Nieto JC, Kácha O, Arvanitis A, Xiao Q, Cárcamo R, Zorjan S, Tajchman Z, Vilares I, Pavlacic JM, Kunst JR, Tamnes CK, von Bastian CC, Atari M, Sharifian M, Hricova M, Kačmár P, Schrötter J, Rahal R, Cohen N, FatahModarres S, Zrimsek M, Zakharov I, Koehn MA, Esteban-Serna C, Calin-Jageman RJ, Krafnick AJ, Štrukelj E, Isager PM, Urban J, Silva JR, Martončik M, Očovaj SB, Šakan D, Kuzminska AO, Djordjevic JM, Almeida IA, Ferreira A, Lazarevic LB, Manley H, Ricaurte DZ, Monteiro RP, Etabari Z, Musser E, Dunleavy D, Chou W, Godbersen H, Ruiz-Fernández S, Reeck C, Batres C, Kirgizova K, Muminov A, Azevedo F, Alvarez DS, Butt MM, Lee JM, Chen Z, Verbruggen F, Ziano I, Tümer M, Charyate AC, Dubrov D, Tejada Rivera MD, Aberson C, Pálfi B, Maldonado MA, Hubena B, Sacakli A, Ceary CD, Richard KL, Singer G, Perillo JT, Ballantyne T, Cyrus-Lai W, Fedotov M, Du H, Wielgus M, Pit IL, Hruška M, Sousa D, Aczel B, Szaszi B, Adamus S, Barzykowski K, Micheli L, Schmidt N, Zsido AN, Paruzel-Czachura M, Bialek M, Kowal M, Sorokowska A, Misiak M, Mola D, Ortiz MV, Correa PS, Belaus A, Muchembled F, Ribeiro RR, Arriaga P, Oliveira R, Vaughn LA, Szwed P, Kossowska M, Czarnek G, Kielińska J, Antazo B, Betlehem R, Stieger S, Nilsonne G, Simonovic N, Taber J, Gourdon-Kanhukamwe A, Domurat A, Ihaya K, Yamada Y, Urooj A, Gill T, Čadek M, Bylinina L, Messerschmidt J, Kurfalı M, Adetula A, Baklanova E, Albayrak-Aydemir N, Kappes HB, Gjoneska B, House T, Jones MV, Berkessel JB, Chopik WJ, Çoksan S, Seehuus M, Khaoudi A, Bokkour A, El Arabi KA, Djamai I, Iyer A, Parashar N, Adiguzel A, Kocalar HE, Bundt C, Norton JO, Papadatou-Pastou M, De la Rosa-Gomez A, Ankushev V, Bogatyreva N, Grigoryev D, Ivanov A, Prusova I, Romanova M, Sarieva I, Terskova M, Hristova E, Kadreva VH, Janak A, Schei V, Sverdrup TE, Askelund AD, Pineda LM, Krupić D, Levitan CA, Johannes N, Ouherrou N, Say N, Sinkolova S, Janjić K, Stojanovska M, Stojanovska D, Khosla M, Thomas AG, Kung FY, Bijlstra G, Mosannenzadeh F, Balci BB, Reips U, Baskin E, Ishkhanyan B, Czamanski-Cohen J, Dixson BJ, Moreau D, Sutherland CA, Chuan-Peng H, Noone C, Flowe H, Anne M, Janssen SM, Topor M, Majeed NM, Kunisato Y, Yu K, Daches S, Hartanto A, Vdovic M, Anton-Boicuk L, Forbes PA, Kamburidis J, Marinova E, Nedelcheva-Datsova M, Rachev NR, Stoyanova A, Schmidt K, Suchow JW, Koptjevskaja-Tamm M, Jernsäther T, Olofsson JK, Bialobrzeska O, Marszalek M, Tatachari S, Afhami R, Law W, Antfolk J, Žuro B, Van Doren N, Soto JA, Searston R, Miranda J, Damnjanović K, Yeung SK, Krupić D, Hoyer K, Jaeger B, Ren D, Pfuhl G, Klevjer K, Corral-Frías NS, Frias-Armenta M, Lucas MY, Torres AO, Toro M, Delgado LG, Vega D, Solas S, Vilar R, Massoni S, Frizzo T, Bran A, Vaidis DC, Vieira L, Paris B, Capizzi M, Coelho GL, Greenburgh A, Whitt CM, Tullett AM, Du X, Volz L, Bosma MJ, Karaarslan C, Sarıoğuz E, Allred TB, Korbmacher M, Colloff MF, Lima TJ, Ribeiro MF, Verharen JP, Karekla M, Karashiali C, Sunami N, Jaremka LM, Storage D, Habib S, Studzinska A, Hanel PH, Holford DL, Sirota M, Wolfe K, Chiu F, Theodoropoulou A, Ahn ER, Lin Y, Westgate EC, Brohmer H, Hofer G, Dujols O, Vezirian K, Feldman G, Travaglino GA, Ahmed A, Li M, Bosch J, Torunsky N, Bai H, Manavalan M, Song X, Walczak RB, Zdybek P, Friedemann M, Rosa AD, Kozma L, Alves SG, Lins S, Pinto IR, Correia RC, Babinčák P, Banik G, Rojas-Berscia LM, Varella MA, Uttley J, Beshears JE, Thommesen KK, Behzadnia B, Geniole SN, Silan MA, Maturan PL, Vilsmeier JK, Tran US, Izquierdo SM, Mensink MC, Sorokowski P, Groyecka-Bernard A, Radtke T, Adoric VC, Carpentier J, Özdoğru AA, Joy-Gaba JA, Hedgebeth MV, Ishii T, Wichman AL, Röer JP, Ostermann T, Davis WE, Suter L, Papachristopoulos K, Zabel C, Ebersole CR, Chartier CR, Mallik PR, Urry HL, Buchanan EM, Coles NA, Primbs MA, Basnight-Brown DM, IJzerman H, Forscher PS, Moshontz H. A multi-country test of brief reappraisal interventions on emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav. 2021 Aug;5(8):1089–110. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01173-x. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34341554 .10.1038/s41562-021-01173-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doré BP, Morris RR, Burr DA, Picard RW, Ochsner KN. Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one's own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2017 May;43(5):729–39. doi: 10.1177/0146167217695558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arbel R, Khouri M, Sagi J. Reappraising negative emotions reduces distress during the COVID-19 outbreak. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/y25gx. Preprint posted online on September 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhoades H, Rusow JA, Bond D, Lanteigne A, Fulginiti A, Goldbach JT. Homelessness, mental health and suicidality among LGBTQ youth accessing crisis services. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2018 Aug 10;49(4):643–51. doi: 10.1007/s10578-018-0780-1.10.1007/s10578-018-0780-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perczel Forintos D, Rózsa S, Pilling J, Kopp M. Proposal for a short version of the Beck Hopelessness Scale based on a national representative survey in Hungary. Community Ment Health J. 2013 Dec;49(6):822–30. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9619-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turnell AI, Fassnacht DB, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Kyrios M. The Self-Hate Scale: development and validation of a brief measure and its relationship to suicidal ideation. J Affect Disord. 2019 Feb 15;245:779–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.047.S0165-0327(18)31314-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox KR, Harris JA, Wang SB, Millner AJ, Deming CA, Nock MK. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview-revised: development, reliability, and validity. Psychol Assess. 2020 Jul;32(7):677–89. doi: 10.1037/pas0000819.2020-28140-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Field A, Miles J, Field Z. Discovering Statistics Using R. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2012. pp. 390–391. [Google Scholar]

- 43.MOTE: Magnitude of the Effect - An Effect Size and CI calculator. GitHub. [2022-06-29]. http://github.com/doomlab/MOTE .

- 44.Bauer DF. Constructing confidence sets using rank statistics. J Am Stat Assoc. 1972 Sep;67(339):687–90. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1972.10481279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2018 Dec 05;57(1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dobias M, Morris R, Schleider J. Analysis Code and De-identified Data. Open Science Framework. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/k3prh. Preprint posted online on February 22, 2021. https://osf.io/e3ys5/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baumel A, Fleming T, Schueller SM. Digital micro interventions for behavioral and mental health gains: core components and conceptualization of digital micro intervention care. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Oct 29;22(10):e20631. doi: 10.2196/20631. https://www.jmir.org/2020/10/e20631/ v22i10e20631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moshe I, Terhorst Y, Philippi P, Domhardt M, Cuijpers P, Cristea I, Pulkki-Råback L, Baumeister H, Sander LB. Digital interventions for the treatment of depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2021 Aug;147(8):749–86. doi: 10.1037/bul0000334.2022-09577-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interven. 2014 Oct;1(4):205–15. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wies B, Landers C, Ienca M. Digital mental health for young people: a scoping review of ethical promises and challenges. Front Digit Health. 2021 Sep 6;3:697072. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.697072. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34713173 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torous J, Roberts LW. Needed innovation in digital health and smartphone applications for mental health: transparency and trust. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 01;74(5):437–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0262.2616170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung JY, Mumper E, Schleider JL. Empowering anxious parents to manage child avoidance behaviors: randomized control trial of a single-session intervention for parental accommodation. JMIR Ment Health. 2021 Jul 06;8(7):e29538. doi: 10.2196/29538. https://mental.jmir.org/2021/7/e29538/ v8i7e29538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Issa T, Isaias P. Usability and human computer interaction (HCI) In: Issa T, Isaias P, editors. Sustainable Design: HCI, Usability and Environmental Concerns. London, UK: Springer; 2015. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng W, Kanthawala S, Yuan S, Hussain SA. A qualitative study of user perceptions of mobile health apps. BMC Public Health. 2016 Nov 14;16(1):1158. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3808-0. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-016-3808-0 .10.1186/s12889-016-3808-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cummings JR, Druss BG. Racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use among adolescents with major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;50(2):160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21241953 .S0890-8567(10)00849-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elster A, Jarosik J, VanGeest J, Fleming M. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Sep;157(9):867–74. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.867.157/9/867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kemp J, Barker D, Benito K, Herren J, Freeman J. Moderators of psychosocial treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: summary and recommendations for future directions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2021;50(4):478–85. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2020.1790378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM, Krumholz Marchette LS, Chu BC, Weersing VR, Fordwood SR. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol. 2017;72(2):79–117. doi: 10.1037/a0040360.2017-07146-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramos G, Chavira DA. Use of technology to provide mental health care for racial and ethnic minorities: evidence, promise, and challenges. Cogn Behav Pract. 2022 Feb;29(1):15–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2019.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friis-Healy EA, Nagy GA, Kollins SH. It is time to REACT: opportunities for digital mental health apps to reduce mental health disparities in racially and ethnically minoritized groups. JMIR Ment Health. 2021 Jan 26;8(1):e25456. doi: 10.2196/25456. https://mental.jmir.org/2021/1/e25456/ v8i1e25456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2018. Pew Research Center. 2018. [2022-06-29]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- 62.Bauerly BC, McCord RF, Hulkower R, Pepin D. Broadband access as a public health issue: the role of law in expanding broadband access and connecting underserved communities for better health outcomes. J Law Med Ethics. 2019 Jun;47(2_suppl):39–42. doi: 10.1177/1073110519857314. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31298126 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kramer J, Conijn B, Oijevaar P, Riper H. Effectiveness of a Web-based solution-focused brief chat treatment for depressed adolescents and young adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014 May 29;16(5):e141. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3261. https://www.jmir.org/2014/5/e141/ v16i5e141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Zanden R, Kramer J, Gerrits R, Cuijpers P. Effectiveness of an online group course for depression in adolescents and young adults: a randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012 Jun 07;14(3):e86. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2033. https://www.jmir.org/2012/3/e86/ v14i3e86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Stigma starts early: gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. J Adolesc Health. 2006 Jun;38(6):754.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011.S1054-139X(05)00395-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sileo KM, Kershaw TS. Dimensions of masculine norms, depression, and mental health service utilization: results from a prospective cohort study among emerging adult men in the United States. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14(1):1557988320906980. doi: 10.1177/1557988320906980. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1557988320906980?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kazdin AE. Annual Research Review: expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;60(4):455–72. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]