Abstract

Background

Physical activity (including exercise) may form an important part of regular care for people with cystic fibrosis (CF). This is an update of a previously published review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of physical activity interventions on exercise capacity by peak oxygen uptake, lung function by forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and further important patient‐relevant outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis (CF).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group Trials Register which comprises references identified from comprehensive electronic database searches and handsearches of relevant journals and abstract books of conference proceedings. The most recent search was on 3 March 2022. We also searched two ongoing trials registers: clinicaltrials.gov, most recently on 4 March 2022; and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), most recently on 16 March 2022.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing physical activity interventions of any type and a minimum intervention duration of two weeks with conventional care (no physical activity intervention) in people with CF.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected RCTs for inclusion, assessed methodological quality and extracted data. We assessed the certainty of the evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We included 24 parallel RCTs (875 participants). The number of participants in the studies ranged from nine to 117, with a wide range of disease severity. The studies' age demographics varied: in two studies, all participants were adults; in 13 studies, participants were 18 years and younger; in one study, participants were 15 years and older; in one study, participants were 12 years and older; and seven studies included all age ranges. The active training programme lasted up to and including six months in 14 studies, and longer than six months in the remaining 10 studies. Of the 24 included studies, seven implemented a follow‐up period (when supervision was withdrawn, but participants were still allowed to exercise) ranging from one to 12 months. Studies employed differing levels of supervision: in 12 studies, training was supervised; in 11 studies, it was partially supervised; and in one study, training was unsupervised. The quality of the included studies varied widely.

This Cochrane Review shows that, in studies with an active training programme lasting over six months in people with CF, physical activity probably has a positive effect on exercise capacity when compared to no physical activity (usual care) (mean difference (MD) 1.60, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16 to 3.05; 6 RCTs, 348 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). The magnitude of improvement in exercise capacity is interpreted as small, although study results were heterogeneous. Physical activity interventions may have no effect on lung function (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) % predicted) (MD 2.41, 95% CI ‒0.49 to 5.31; 6 RCTs, 367 participants), HRQoL physical functioning (MD 2.19, 95% CI ‒3.42 to 7.80; 4 RCTs, 247 participants) and HRQoL respiratory domain (MD ‒0.05, 95% CI ‒3.61 to 3.51; 4 RCTs, 251 participants) at six months and longer (low‐certainty evidence). One study (117 participants) reported no differences between the physical activity and control groups in the number of participants experiencing a pulmonary exacerbation by six months (incidence rate ratio 1.28, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.94) or in the time to first exacerbation over 12 months (hazard ratio 1.34, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.80) (both high‐certainty evidence); and no effects of physical activity on diabetic control (after 1 hour: MD ‒0.04 mmol/L, 95% CI ‒1.11 to 1.03; 67 participants; after 2 hours: MD ‒0.44 mmol/L, 95% CI ‒1.43 to 0.55; 81 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). We found no difference between groups in the number of adverse events over six months (odds ratio 6.22, 95% CI 0.72 to 53.40; 2 RCTs, 156 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

For other time points (up to and including six months and during a follow‐up period with no active intervention), the effects of physical activity versus control were similar to those reported for the outcomes above. However, only three out of seven studies adding a follow‐up period with no active intervention (ranging between one and 12 months) reported on the primary outcomes of changes in exercise capacity and lung function, and one on HRQoL. These data must be interpreted with caution. Altogether, given the heterogeneity of effects across studies, the wide variation in study quality and lack of information on clinically meaningful changes for several outcome measures, we consider the overall certainty of evidence on the effects of physical activity interventions on exercise capacity, lung function and HRQoL to be low to moderate.

Authors' conclusions

Physical activity interventions for six months and longer likely improve exercise capacity when compared to no training (moderate‐certainty evidence). Current evidence shows little or no effect on lung function and HRQoL (low‐certainty evidence). Over recent decades, physical activity has gained increasing interest and is already part of multidisciplinary care offered to most people with CF. Adverse effects of physical activity appear rare and there is no reason to actively discourage regular physical activity and exercise. The benefits of including physical activity in an individual's regular care may be influenced by the type and duration of the activity programme as well as individual preferences for and barriers to physical activity. Further high‐quality and sufficiently‐sized studies are needed to comprehensively assess the benefits of physical activity and exercise in people with CF, particularly in the new era of CF medicine.

Plain language summary

Physical activity to improve exercise capacity in people with cystic fibrosis

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about whether physical activity interventions (including exercise) have any effect on exercise capacity, health‐related quality of life and lung function in people with cystic fibrosis (CF). This is an update of a previously published review.

Background

CF affects many systems in the body, but mainly the lungs. It causes shortness of breath and limits the amount of exercise people with CF can tolerate. The progress of lung disease leads to a low ability to exercise and to physical inactivity, which in turn affects health and health‐related quality of life. We looked for studies where people with CF engaged in a physical activity intervention (including endurance‐type activities such as walking, jogging, swimming and cycling; or resistance training; or combinations of both) compared to a control group with no intervention (usual care).

Search date

The evidence is current to 3 March 2022.

Study characteristics

We included 24 studies (875 participants) in this review. The number of people in each study ranged from nine to 117. Some studies included only children, others only adults, and some both children and adults. The studies included people with a wide range of disease severity. The studies used differing levels of supervision in their active training programmes: in 12 studies, participants were supervised; in 11 studies, participants were partially supervised; and in one study, participants were not supervised at all. The active training programme lasted up to and including six months in 14 studies, and longer than six months in the remaining 10 studies. Of the 24 included studies, seven added on a follow‐up period (when all participants reverted to usual care, but were still allowed to exercise if they wished). The quality of the included studies varied widely.

Key results

This systematic review shows that physical activity interventions for longer than six months probably improve exercise capacity in people with CF. When compared with no activity, physical activity interventions may make little or no difference to lung function and health‐related quality of life.

The largest study included in this review (117 participants) reported:

‐ no differences between the physical activity and control groups in the number of pulmonary exacerbations (a flare up of disease) (high‐certainty evidence);

‐ no differences in the time to the first flare up for 12 months (high‐certainty evidence);

‐ no beneficial effects of physical activity on diabetic control after nine months (moderate‐certainty evidence).

Two studies (156 participants) found no differences between groups in the number of reported adverse events (low‐certainty evidence).

For active training programmes lasting up to and including six months, the effects were similar to the longer programmes.

Only three studies which added a follow‐up period (of varying durations) reported data we could analyse on changes in exercise capacity and lung function; and only one reported on quality of life. These results must be interpreted with caution.

Overall and when compared to usual care (no intervention), physical activity and exercise training probably lead to slightly better exercise capacity, while they may have little or no effect on lung function and health‐related quality of life in people with CF.

Certainty of the evidence

We included 24 studies. Given the differences in effects across studies, the wide variation in study quality and the lack of information on clinically meaningful changes for several outcome measures, we consider the overall certainty of the evidence on the effects of physical activity interventions on exercise capacity, lung function and health‐related quality of life as low to moderate. We are uncertain about the effects we have seen and better‐quality studies will likely change these findings.

Factors affecting our certainty included that, in five studies, the characteristics of some of the people taking part were different between groups at the start of the studies, despite people being put into the different treatment groups at random.

Also, when comparing physical activity interventions to no intervention, people will always know which group they are in. However, we do not think the fact that people knew which treatment they were receiving would affect the results for lung function, as long as the assessments were done properly. In contrast, some bias may be introduced when investigators assessing a person's exercise capacity know to which group the person belongs. Investigators tried to prevent the outcome assessors from knowing to which groups the participants belonged in 10 included studies.

Selective reporting of results may also be an issue, especially as most of the included studies were not listed in trial registries, where details of the outcomes are reported.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Physical activity compared with no physical activity for cystic fibrosis.

| Physical activity compared with no physical activity for cystic fibrosis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with cystic fibrosis Settings: at home or in hospital Intervention: physical activity Comparison: no physical activity (usual care) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Physical activity | |||||

|

Exercise capacity: change in VO2 peak (mL/min per kg bodyweight) Active intervention: > 6 months |

VO2 peak was 1.60 mL/min per kg bodyweight higher in the physical activity group than in the control group (0.16 mL/min per kg bodyweight higher to 3.05 mL/min per kg bodyweight higher). |

— | 348 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝

Moderatea,b |

P = 0.005 Sensitivity analysis which removed 1 small outlying study did not alter the results. Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 8 studies reported the effect of physical activity for periods of up to and including 6 months (MD 2.10 mL/min per kg bodyweight, 95% CI 0.06 to 4.13; n = 323; P = 0.04). There was a high level of heterogeneity in the results. Follow‐up (no active intervention) This was reported by 3 out of 9 studies. VO2 peak was higher in the physical activity versus control groups (MD 3.27 mL/min per kg bodyweight, 95% CI 1.37 to 5.18; n = 125; P < 0.001). |

|

|

FEV1 % predicted (change from baseline) Active intervention: > 6 months |

The mean change in FEV1 % predicted was 2.41% higher in the physical activity group than in the control group (0.49% lower to 5.31% higher). | — | 367 (6) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝

Lowa,c |

P = 0.1 Sensitivity analysis which removed 1 small outlying study with wide CIs changed the effect slightly towards a beneficial effect of physical activity (MD 1.71 % predicted, 95% CI 0.15 to 3.26; P = 0.02). Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 8 studies found no difference between the physical activity group and control group (MD 1.30 % predicted, 95% CI ‒3.01 to 5.61; n = 356; P = 0.56). Follow‐up (no active intervention) 3/9 studies reported this outcome and found no difference between groups (MD 5.68 % predicted, 95% CI ‒1.88 to 13.23; n = 128; P = 0.14). |

|

|

HRQoL: change in CFQ‐R physical functioning domain score Active intervention: > 6 months |

The mean change in CFQ‐R score was 2.19 points higher in the physical activity group than in the control group (3.42 points lower to 7.80 points higher). | — | 247 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | P = 0.44 Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 6 studies reported that there was no difference in HRQoL CFQ‐R scores between groups (MD 4.67, 95% CI ‒2.55 to 11.90; n = 217; P = 0.21). Follow‐up (no active intervention) No studies reported CFQ‐R after a period off training. |

|

|

HRQoL: change in CFQ‐R respiratory symptoms domain score Active intervention: > 6 months |

The mean change in CFQ‐R score was 0.05 points lower in the physical activity group than in the control group (3.61 points lower to 3.51 points higher). | — | 251 (4) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | P = 0.98 Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 5 studies reported that there was no difference in HRQoL CFQ‐R scores between groups (MD ‒1.87, 95% CI ‒5.66 to 1.92; n = 212; P = 0.33). Follow‐up (no active intervention) No studies reported CFQ‐R after a period off training. |

|

|

Pulmonary exacerbations: number of exacerbations occurring in the study period Active intervention: 12 months |

There was no difference in the number of pulmonary exacerbations between the physical activity and control group. The incidence rate ratio was 1.28 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.94). | — | 117 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕

High |

P = 0.24 There was also no difference in the time to first exacerbation between the groups, HR 1.34 (95% CI 0.65 to 2.80). Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 1 study reported no difference in the number of exacerbations between groups at the 6‐month time point (incidence rate ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.90), or in the time to first exacerbation (HR 1.34, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.80). Follow‐up (no active intervention) No studies reported this outcome after a period off training. |

|

|

Diabetic control: change in blood glucose levels at rest, at 60 and 120 minutes after a glucose ingestion (mmol/L) Active intervention: 9 months |

There were no differences between the physical activity and control groups with regard to blood glucose. At rest: MD ‒0.16 mmol/L (95% CI ‒0.44 to 0.12) After 60 minutes: MD ‒0.04 mmol/L (95% CI ‒1.11 to 1.03) After 120 minutes: MD ‒0.44 mmol/L (95% CI ‒1.43 to 0.55) |

— | 91 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatee | Participants included for this outcome did not have a diagnosis of CFRD on entry to the study. Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 1 study (n = 14, including 2 people with CFRD at study entry) assessed HbA1c, plasma glucose and insulin response to an oral glucose tolerance test. There was no difference in HbA1c (MD ‒0.00%, 95% CI ‒0.01 to 0.00). There was no difference in plasma glucose values between groups at any time point apart from at 120 minutes postglucose test when there was a significant difference favouring the exercise group (Beaudoin 2017). Follow‐up (no active intervention) No studies reported this outcome after a period off training. |

|

|

Adverse events: number of adverse events Active intervention: 12 months |

1 study reported no adverse events in either the physical activity or control group during the 12‐month study period (Kriemler 2013). A larger study reported no difference in the number of participants experiencing an adverse event or serious adverse event related to the intervention between the physical activity and no physical activity group (adverse events: OR 6.22, 95% CI 0.72 to 53.40; serious adverse events: OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.54) (Hebestreit 2022). |

— | 156 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowf,g | Other time points: Active intervention ≤ 6 months 2 studies reported adverse events: in the first study there was muscle stiffness (common after active video games) and in the second study there was an ankle injury in the physical activity group and haemoptysis in 1 participant in the control group. 1 further study reported no adverse events during the 6‐week intervention period. Follow‐up (no active intervention) In 1 study it was not clear if the earlier reported muscle stiffness continued in the follow‐up period. The study that reported no adverse events in the 6‐week intervention period, also observed no adverse events in the follow‐up period. |

|

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CFQ‐R: Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire – Revised; CFRD: cystic fibrosis‐related diabetes; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin; HR: hazard ratio; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; MD: mean difference; n: number of participants; OR: odds ratio; VO2 peak: peak oxygen uptake. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded once due to high or unclear risk of bias across many of the domains for the included studies. Two studies contributing data to this outcome were at high risk of bias due to concerns around randomisation and allocation concealment. bThere was moderate heterogeneity in the results, but this was due to an outlying study (Kriemler 2013). When this study was removed from the analysis, the result remained significant and therefore we did not downgrade the certainty of evidence due to inconsistency. The outlying study included small numbers and had wide CIs around the effect. cThere was moderate heterogeneity in the results due to a small outlying study with wide CIs (Kriemler 2013); downgraded once. dDowngraded twice due to risk of bias across several domains in the studies included in this analysis. There were particular concerns around randomisation and allocation concealment in three of the four included studies. eDowngraded once due to imprecision caused by a small number of participants. fDowngraded once due to risk of bias in one of the two included studies for this outcome. gDowngraded once for imprecision (low event rates and wide CIs).

Background

Description of the condition

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life‐limiting, autosomal, recessively inherited disease in populations of Northern European descent. The worldwide incidence of CF has been estimated, on average, at between 1/3000 and 1/6000 live births, with great regional variation (Farrell 2008; Scotet 2020; Southern 2007). Life expectancy of people with CF has increased substantially over recent decades (MacKenzie 2014), with a large proportion of newborns expected to survive into their fifth decade and beyond (Keogh 2018). On the one hand, the changing demographics of CF lung disease and the growing population of older adults (Burgel 2015) with multiple chronic conditions and an increasing number of cardiovascular disease risk factors pose new challenges to healthcare professionals, including those providing and supervising physical activity and exercise training. On the other hand, a substantial proportion of people with CF can now benefit from highly effective drug therapies (Middleton 2019). However, their impact on individuals' daily physical activity and exercise behaviour is currently unknown and remains to be investigated. Reduced exercise capacity is still common among people with CF (Radtke 2018a), and is associated with reduced life expectancy (Hebestreit 2019; Nixon 1992; Pianosi 2005). Thus, healthcare professionals should encourage and support people with CF to live an active lifestyle early on, and, ideally, provide advice and guidance addressing individual barriers and facilitators to long‐term participation in physical activity.

Description of the intervention

Physical activity is defined as "any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure" (Caspersen 1985). Exercise training is a subcomponent of physical activity that is planned, structured and done repetitively, with the objective of improving or maintaining physical fitness (Caspersen 1985). It can be defined as participation in a programme of regular vigorous physical activity designed to improve physical performance, cardiovascular function, muscle strength or any combination of these three (Shephard 1994). There are basically two different types of exercise training: aerobic training or anaerobic training, but neither can be considered purely 'aerobic' or 'anaerobic' with respect to energy supply. Aerobic exercise usually involves periods of continuous and rhythmic training of large muscle groups (e.g. cycling or running) that rely predominantly on aerobic energy metabolism. Anaerobic exercise involves training (e.g. weight or resistance training, sprinting or high‐intensity interval training) at a high intensity for a very short duration (ACSM 2017). In this review, we use a broad categorisation of aerobic and anaerobic activities to characterise exercise training studies. However, unlike previous versions of this review, we no longer focus on comparisons between aerobic, anaerobic or a combination of aerobic and anaerobic training regimens versus no training.

Importantly, this review includes both physical activity and exercise training interventions. Exercise training refers to activities that are done for a certain purpose; for example, to improve fitness or to aid the clearance of secretions from the lungs. Since exercise training is a subcomponent of physical activity, we also include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that focused on improving daily (vigorous) physical activity levels by using wearable technology, such as step counters and fitness trackers, using goal setting and providing motivational feedback throughout their intervention (Nuss 2021), telehealth interventions, or combinations of those. For the rest of this review, we will use the term 'physical activity' inclusive of formal exercise training for ease to the reader.

How the intervention might work

Physical activity has multiple beneficial effects, and is one of the five most important treatments, as rated by people with CF (Davies 2020). Physical activity contributes to the alleviation of exertional dyspnoea and improves exercise tolerance in people with CF (Cerny 2013). Regular physical activity slows the rate of decline in pulmonary function by improving sputum clearance (Cox 2016; Cox 2018; Schneiderman 2014), likely through a combination of hyperventilation, mechanical vibration, coughing and changes in sputum rheology, leading to facilitated and increased sputum expectoration (Dwyer 2011; Dwyer 2017; Hebestreit 2001).

Regular physical activity may also be an important part of the management of diabetes in CF, as it improves glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing systemic inflammation (Galassetti 2013). Regular physical activity may also delay the onset of osteoporosis by preventing a reduction in bone mineral density (Tejero García 2011). Other postulated benefits of physical activity may be decreased anxiety and depression, and enhanced feelings of well‐being and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (Hebestreit 2014). Non‐adherence to prescribed physical activity may contribute to worsening signs and symptoms of respiratory disease, more frequent respiratory infections and a reduced ability to perform activities of daily living, and thus ultimately have a detrimental effect on the individual's prognosis. Side effects of physical activity are rare, so it can be considered safe in CF (Ruf 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

This review aims to provide evidence for the chronic effects of physical activity interventions on physiological, functional and patient‐reported outcomes in people with CF. Optimal physical activity programmes (e.g. duration, intensity, type of activity, level of supervision) for people with CF are unknown and have yet to be defined. Doing so would help to support healthcare professionals, who often lack confidence in providing individualised physical activity advice (Denford 2020). This is an update of previous versions of the review (Bradley 2002; Bradley 2008; Radtke 2015; Radtke 2017).

Objectives

To assess the effects of physical activity interventions on exercise capacity by peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak), lung function by forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), HRQoL and further important patient‐relevant outcomes in people with CF.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs.

Types of participants

People with CF, of any age, and any degree of disease severity, diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria and sweat testing or genotype analysis.

Types of interventions

Any type of prescribed physical activity intervention delivered to people with CF compared to usual care. We excluded studies which involved pure respiratory muscle training (exercise training specifically targeting the muscles that drive expansion or contraction of the chest, or both). In a post hoc change, we stipulated that studies must have an intervention duration of at least two weeks.

Types of outcome measures

For the 2022 review update, the review author team decided to reduce the number of secondary outcome measures to those that are most important to people living with CF, clinically relevant and patient‐centred. We removed outcomes that are rarely assessed, for which no standardised assessment is available, and outcomes that rely (mostly) on equations that are prone to measurement bias (e.g. fat‐free mass based on skinfold thickness). Please see more comprehensive details in the section Differences between protocol and review.

We assessed the following outcome measures at up to and including six months and longer than six months of active interventions and also for a follow‐up period where all participants received usual care.

Primary outcomes

Exercise capacity (VO2 peak reported either as L/min, mL/min and per kg bodyweight or kg fat‐free mass or as per cent (%) predicted)

Lung function measured as FEV1 (reported either as L or % predicted and as absolute values or change from baseline)

-

HRQoL (measured by generic or disease‐specific instruments, or both, using validated instruments or patient reports)

physical functioning

respiratory

other

Secondary outcomes

-

Additional indices of exercise capacity

peak work capacity (reported as either watt (W) absolute values, W per kg bodyweight, W % predicted or change from baseline)

submaximal exercise capacity (e.g. time to the limit of tolerance in constant work rate exercise tests or oxygen uptake or work rate at the anaerobic threshold, or both)

functional exercise capacity (i.e. 6‐minute walk test (6MWT) and shuttle tests)

-

Quadriceps muscle strength

isometric muscle strength, measured with strain gauges fixed to a medical bench/chair or using dynamometry (reported as either kg or newtons (N))

isokinetic muscle strength measured by isokinetic dynamometry (reported as newton‐metres (N.m))

Lung function measured as forced vital capacity (FVC) (reported either as L or % predicted and as absolute values or change from baseline)

-

Physical activity

subjective report (e.g. self‐reported diary or validated questionnaires of time spent in moderate‐to‐vigorous/intense activity)

objective report (e.g. pedometers (i.e. number of steps) or accelerometers (i.e. time spent in moderate‐to‐vigorous or vigorous physical activity, or both))

Body mass index (BMI) (reported as kg/m² or z‐scores)

-

Pulmonary exacerbations

number of exacerbations

time to first exacerbation

-

Hospitalisation

number of hospitalisations

number of days in hospital

Bone health, measured by dual x‐ray energy absorptiometry or peripheral quantitative computed tomography

Diabetic control, measured by fasting blood glucose levels (mmol/L or mg/dL), insulin levels (mmol/L or mg/dL) or homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) or oral glucose tolerance test (blood glucose in mmol/L or mg/dL)

Adverse events related to the physical activity intervention or exercise testing as part of intervention

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all relevant published and unpublished trials without restrictions on language, year or publication status.

Electronic searches

We identified relevant studies from the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register using the term 'exercise'.

The Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (updated each new issue of the Cochrane Library), weekly searches of MEDLINE, a search of Embase to 1995 and the prospective handsearching of two journals – Pediatric Pulmonology and the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. Unpublished work is identified by searching through the abstract books of three major CF conferences: the International Cystic Fibrosis Conference, the European Cystic Fibrosis Conference and the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. For full details of all searching activities for the register, please see the relevant sections of the Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group website (cfgd.cochrane.org/our-specialised-trials-registers). Our most recent search of the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register was on 3 March 2022.

We also searched the following trials registers:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 4 March 2022);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (trialsearch.who.int/; searched 16 March 2022).

For details of our search strategies, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of each RCT and of review articles for additional publications that may contain RCTs. We contacted authors of studies included in this review and other experts in the field to request information on other published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

We used the following methods where possible.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (for the original review, JB and FM; for the 2015 and 2017 updates, SK and TR; for the 2022 update, TR and SS) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of identified citations and selected the studies to be included in the review. We excluded non‐RCTs, studies involving respiratory muscle training exclusively, studies which did not have a physical activity programme and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria, based on screening the abstracts or full‐text articles. If disagreement arose on the suitability of a study for inclusion in the review, we reached a consensus through discussion. We recorded any areas of disagreement. We excluded studies that did not fulfil all of the inclusion criteria, and listed their details with the reason for exclusion. A third review author resolved discrepancies where any disagreement or uncertainty between the two review authors persisted.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (for the 2015 and 2017 updates, SK and TR, or for the included studies where SK and TR were authors, SS and SN; for the 2022 update, TR and SS), independently extracted data using a standard data acquisition form. We collected information about: study design (parallel versus multiarm; single‐centre versus multicentre; participants and study characteristics for baseline equality between groups; details on the number of participants screened for eligibility, randomised, analysed, excluded, lost to follow‐up and dropped out; method of randomisation and allocation concealment; blinding of personnel and outcome assessors; use of stratification; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; use of intention‐to‐treat analysis); the detailed intervention (aerobic training, anaerobic training, or a combination of both training regimens; duration of physical activity intervention (either supervised, partially supervised or unsupervised, i.e. up to and including six months, over six months, and studies with a follow‐up period (where all participants received usual care)); and whether the intervention was supervised, partially supervised or not supervised, but still with access to resources for physical activity additional to usual care); and outcome measures (continuous and dichotomous). If disagreement arose about the quality of a study, we attempted to reach a consensus through discussion. If disagreement persisted, a third review author arbitrated. We recorded any areas of disagreement. One review author (for the original review, JB; from the 2015 update onwards, TR) entered the data into the Cochrane software Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014), and a second review author (for the 2015 and 2017 update, SK; for the 2021 update, SS) reviewed it. We contacted the authors of the included studies in case of unclear or missing data and information.

We pooled data comparing physical activity versus no activity. For all outcomes in this review, we combined the two active arms of the Kriemler 2013 and Selvadurai 2002 studies. For the meta‐analysis of the primary outcomes FEV1, VO2 peak and HRQoL, we chose the measurement time points with the longest duration of controlled intervention (i.e. the time point up to which control group participants were asked to maintain their baseline physical activity level).

We reported results from each category of physical activity intervention at the end of that specific category; we reported results from the follow‐up periods during which all participants received usual care in a separate category labelled 'Follow‐up (no active intervention)'. If a study reported multiple time points for a single category of intervention (supervised, partially supervised or unsupervised) within our predefined training period lengths (i.e. up to and including six months, and longer than six months), we reported the longest time point within the given category. For example, Kriemler 2013 included assessments at three months and six months (fully supervised), 12 months (during the second six months participants were not supervised but still had access to physical activity resources from the study) and 24 months (i.e. 12 months' follow‐up with no active intervention or provision of resources)). In this case, we reported the six‐month, 12‐month and 24‐month assessments and discarded the three‐month assessment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the original review, two review authors judged the methodological quality of the review (JB, FM). For the review updates, two authors (2015 and 2017 update: SK and TR; 2022 update: SS and TR or SS and SN) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2017). In particular, we examined details of the randomisation method with sequence generation, allocation concealment, degree of blinding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dropouts or withdrawals, intention‐to‐treat and detailed statistical analysis. We also assessed the risk of selective reporting and any other potential sources of bias. For each domain, we judged the risk of bias as low, unclear or high. We considered unexplained dropouts or an unequal number of dropouts across treatment groups as a potential risk of bias. Likewise, we also considered a lack of important information (e.g. on adverse effects, missing data, statistical methods, etc.) as a potential risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported continuous outcome data and calculated the mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where between‐group differences in the mean change from baseline were recorded. When data on the standard deviation (SD) for an individual group were not available, but instead standard error (SEM) of the difference was available, we used the calculator within the Review Manager 5 to compute the MD with 95% CIs (Review Manager 2014). Where possible, we used the published standard error of the mean (SEM), or alternatively, we used published CIs to estimate SEM. In this review update, we report the number of acute pulmonary exacerbations as incidence rate ratios (i.e. based on mixed Poisson regression models, as reported in Hebestreit 2022, which is the only included study that reported this outcome). We analysed the outcome of 'time to first pulmonary exacerbation' between the physical activity intervention and control groups as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. We analysed the number of adverse events directly related to physical activity as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

In future updates of this review, if trials use different measurement scales for an outcome, we plan to analyse the data using the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We have not included any cross‐over studies in this latest version of the review. If future versions of this review include cross‐over studies, and if data are presented in published papers from paired statistical analyses or if information is available to allow us to adjust for within‐patient correlation using the methods described by Elbourne 2002, we will use the generic inverse variance method for data analysis. If appropriate data are not presented to allow adjustment for within‐patient correlation, we will contact study investigators to request these data. If we are unable to make the necessary adjustments, we will describe data from cross‐over studies narratively in the review.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the investigators of studies included in this review for further study details and data. Fourteen investigators responded. The investigators of four studies stated that the requested data were not available (Klijn 2004; Michel 1989; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002). The investigator of a one study confirmed that the extracted data were correct and that no further data were available (Cerny 1989). We also contacted the investigators of the Hebestreit study; additional data were provided and the paper has since been published. One investigator involved in the Phillips study, currently listed under Studies awaiting classification, confirmed that the study has been completed. We updated the information in the table (Phillips 2008). In both publications by Santana‐Sosa, the means and SEMs were reported for all variables; we contacted the investigators for additional data, which we received (Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014). The investigators of Carr 2018 responded to our initial request to provide additional raw data, but did not respond to further emails. We could not include the additional data.

Finally, investigators of eight studies provided additional raw data for this review update (Beaudoin 2017; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Kriemler 2013; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020). We received raw data from the corresponding author of Beaudoin 2017 which allowed us to calculate MD and the corresponding SEM for various outcomes. For Hebestreit 2022, we extracted the MDs and their 95% CIs from the adjusted intention‐to‐treat models with imputation of missing data to compute the relevant SEM using the Review Manager 5 calculator (inverse variance analysis). For Kriemler 2013 study, we extracted mean changes and SDs from the adjusted models for each group and calculated the relevant SEMs (inverse variance analysis). The two studies by Santana‐Sosa reported means and SEM at baseline, post‐training and 'off training' (i.e. labelled as a 'detraining' period in their original publications and defined as a period during which no supervised exercise was offered to intervention group participants) (Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014), and we were unable to calculate the MD. We received incomplete raw data files from the authors. Due to inconsistencies in the data sets provided, we were unable to reproduce all data. Due to our concerns about data quality, we excluded both studies from the formal analysis in the review. Instead, we provided data from these studies in two additional tables (see Table 2; Table 3). Sawyer 2020 reported within‐group changes from baseline as medians (interquartile range) for various outcomes. We received raw data from the authors, checked the distribution of the data (and confirmed normal distribution of the majority of outcomes), and calculated MD and SEM for relevant outcomes.

1. Study results for Santana‐Sosa 2012.

| Variable | Group | Pretraining | Post‐training | Detraininga | P value | Comments |

| Age (mean (SEM)) years | Intervention | 11 (3) | — | — | — | — |

| Control | 10 (2) | — | — | — | ||

| Sex (% boys) | Intervention | 55 | — | — | — | |

| Control | 64 | — | — | — | ||

| VO2 peak (mean (95% CI)) mL/min per kg bodyweight | Intervention | N/A | 3.9 (1.8 to 6.1) | ‒3.4 (‒5.7 to 1.7) | 0.036 | Higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.023). Data were presented in a figure in the original publication. |

| Control | N/A | ‒2.2 (‒5.3 to 0.1) | ‒0.7 (‒4.4 to 5.9) | |||

| Leg press (mean (95% CI)) kg | Intervention | N/A | 24.9 (14.3 to 34.4) | ‒1.0 (‒4.1 to 3.3) | < 0.001 | Data are reported in a figure in the original publication. Significantly higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.014). |

| Control | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Bench press (mean (95% CI)) kg | Intervention | N/A | 10.5 (7.0 to 14.0) | ‒1.2 (‒3.6 to 3.0) | < 0.001 | Significantly higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.007). Data presented in a figure in the original publication. |

| Control | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Seated row (mean (95% CI)) kg | Intervention | N/A | 12.7 (9.2 to 16.0) | ‒0.2 (‒3.6 to 3.2) | < 0.001 | Significantly higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.009). Data presented in a figure in the original publication. |

| Control | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Oxygen saturation at peak exercise (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | 94.9 (0.9) | 95.6 (0.8) | 94.5 (1.2) | N/A | — |

| Control | 95.7 (0.5) | 96.4% (0.4) | 96.1 (0.5) | |||

| FEV1 (mean (SEM)) L | Intervention | 1.87 (0.24) | 1.94 (0.23) | 1.90 (0.25) | 0.769 | — |

| Control | 1.77 (0.17) | 1.87 (0.15) | 1.79 (0.19) | |||

| FVC (mean (SEM)) L | Intervention | 2.41 (0.24) | 2.49 (0.25) | 2.56 (0.29) | 0.920 | — |

| Control | 2.29 (0.19) | 2.36 (0.20) | 2.40 (0.24) | |||

| PImax (mean (SEM)) cmH2O | Intervention | 64.0 (5.5) | 69.8 (6.8) | 75.2 (6.2) | 0.797 | — |

| Control | 61.5 (6.9) | 72.2 (7.2) | 76.4 (7.5) | |||

| HRQoL score – children's report (median (range)) | Intervention | 696 (495–741) | 719 (550–734) | — | 0.257 | HRQoL was assessed before and after the intervention. P value for comparison pre versus post‐training. |

| Control | 649 (578–768) | 638 (461–791) | — | |||

| HRQoL score – parents' report (median (range)) | Intervention | 896 (688–1011) | 889 (811–973) | — | 0.143 | HRQoL was assessed before and after the intervention. |

| Control | 911 (842–1028) | 978 (684–1059) | — | |||

| Weight (mean (SEM)) kg | Intervention | 39.9 (3.5) | 40.5 (3.4) | 41.4 (3.4) | 0.723 | — |

| Control | 34.0 (2.6) | 35.1 (2.8) | 36.2 (3.0) | |||

| BMI (mean (SEM)) kg/m² | Intervention | 18.4 (1.0) | 18.3 (0.7) | 18.5 (0.7) | 0.959 | — |

| Control | 17.2 (0.8) | 17.1 (0.8) | 17.4 (0.9) | |||

| Fat‐free mass (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | 78.1 (2.7) | 79.4 (2.8) | 78.8 (2.9) | 0.115 | — |

| Control | 81.1 (2.5) | 80.9 (2.1) | 81.1 (2.2) | |||

| Body fat (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | 21.9 (2.7) | 20.6 (2.8) | 21.2 (2.9) | 0.115 | — |

| Control | 18.9 (2.5) | 19.1 (2.1) | 18.9 (2.2) | |||

| Compliance with physical training (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | — | 95.1 (7.4) | — | — |

73% of children completed all training sessions. |

| Control | — | — | — | |||

| Adverse effects | Intervention | — | — | — | — | No adverse effects occurred during training or maximal exercise testing. |

| Control | — | — | — |

aDescribed in the original papers as "detraining" but corresponding to our definition of 'off training'.

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; N/A: not applicable; PImax: maximum inspiratory mouth pressure; SEM: standard error of the mean; VO2 peak: peak oxygen consumption.

2. Study results for Santana‐Sosa 2014.

| Variable | Group | Pretraining | Post‐training | Detraininga | P value | Comments |

| Age (mean (SEM)) years | Intervention | 11 (1) | — | — | — | — |

| Control | 10 (1) | — | — | — | ||

| Sex (% boys) | Intervention | 60 | — | — | — | — |

| Control | 60 | — | — | — | ||

| VO2 peak (mean (95% CI) mL/min per kg bodyweight | Intervention | N/A | 6.9 (3.4 to 10.5) | ‒1.5 (‒2.7 to ‒0.4) | < 0.001 | Significantly higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.034). |

| Control | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Leg press (mean (SEM)) kg | Intervention | 62.5 (6.5) | 89.5 (9.3) | 88.6 (9.2) | < 0.001 | Higher in controls at baseline (P = 0.046). |

| Control | 45.2 (4.7) | 43.9 (5.1) | 43.9 (5.4) | |||

| Bench press (mean (SEM)) kg | Intervention | 26.4 (2.7) | 38.4 (3.2) | 35.9 (2.9) | < 0.001 | — |

| Control | 23.2 (2.9) | 21.6 (3.2) | 21.7 (3.6) | |||

| Lateral row (mean (SEM)) kg | Intervention | 30.5 (3.6) | 43.0 (4.2) | 35.9 (2.9) | < 0.001 | — |

| Control | 23.2 (3.0) | 22.0 (3.1) | 21.7 (3.6) | |||

| Oxygen saturation at peak exercise (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | 94.7 (0.7) | 94.5 (0.7) | 93.1 (0.8) | N/A | — |

| Control | 96.4 (0.4) | 96.2 (0.5) | 96.1 (0.6) | |||

| FEV1 (mean (SEM)) L | Intervention | 1.65 (0.19) | 1.74 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.24) | 0.486 | — |

| Control | 1.57 (0.26) | 1.55 (0.26) | 1.59 (0.26) | |||

| FVC (mean (SEM)) L | Intervention | 2.23 (0.27) | 2.34 (0.29) | 2.28 (0.28) | 0.156 | — |

| Control | 1.90 (0.33) | 1.85 (0.32) | 1.92 (0.32) | |||

| PImax (mean (SEM)) cmH2O | Intervention | 68.3 (6.3) | 107.6 (8.4) | 103.2 (8.1) | < 0.001 | — |

| Control | 69.5 (9.7) | 71.8 (10.0) | 66.7 (9.4) | |||

| HRQoL score (median (range)) | Intervention | 629 (505–701) | 688 (609–791) | — | 0.071 | HRQoL was assessed before and after the intervention. |

| Control | 636 (626–745) | 638 (626–737) | — | |||

| Weight (mean (SEM)) kg | Intervention | 36.4 (3.1) | 37.8 (3.2) | 38.3 (3.1) | 0.342 | — |

| Control | 31.5 (4.6) | 32.4 (4.7) | 32.7 (4.5) | |||

| Fat‐free mass (mean (SEM)) % of total | Intervention | 81.6 (1.3) | 82.6 (1.0) | 82.5 (1.0) | 0.001 | — |

| Control | 82.9 (1.8) | 82.8 (1.8) | 82.5 (1.9) | |||

| Body fat (mean (SEM)) % of total | Intervention | 18.4 (1.3) | 17.4 (1.2) | 17.5 (1.1) | 0.023 | — |

| Control | 17.1 (1.8) | 17.2 (1.8) | 17.5 (1.9) | |||

| Compliance with physical training (mean (SEM)) % | Intervention | — | 97.5 (1.7) | — | — | 70% of children completed all training sessions. |

| Control | — | — | — | |||

| Adverse effects | Intervention | — | — | — | — | No adverse effects occurred during training or exercise testing. |

| Control | — | — | — |

aDescribed in the original papers as "detraining" but corresponding to our definition of 'off training'.

CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; N/A: not applicable; PImax: maximum inspiratory mouth pressure; SEM: standard error of the mean; VO2 peak: peak oxygen consumption.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We combined available data (extracted from published papers and calculated as previously stated) and conducted a meta‐analysis on the primary outcomes VO2 peak, FEV1 and HRQoL. We measured heterogeneity between studies using the Chi² test and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). The Chi² test measures the deviation of observed effect sizes from the underlying overall effect. A low P value (or a large Chi² statistic relative to its degree of freedom) provides evidence of heterogeneity of intervention effects (variation in effect estimates beyond chance). We used a P value of 0.10, rather than the conventional level of 0.05, to determine statistical significance. The I² statistic, as defined by Higgins (Higgins 2017), measures heterogeneity as a percentage, where a value:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depends on: (i) magnitude and direction of effects; and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi² test, or a CI for the I² statistic).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed relevant bias and selective reporting by comparing the 'methods' and 'results' sections from the included papers and trial registries, if available. We documented this information in the risk of bias tables for included studies (see Characteristics of included studies table), and in Figure 1 and Figure 2. If future updates of this review include and combine a sufficient number of studies (10 or more), we will assess publication bias, initially by visual inspection of a funnel plot. However, we are aware that an asymmetrical funnel plot is not necessarily due to publication bias.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model for all outcome parameters using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We used a random‐effects model for outcomes that were combined, and for which a meta‐analysis was performed (i.e. VO2 peak, FEV1, HRQoL). The random‐effects model incorporates any between‐study heterogeneity into a meta‐analysis. We selected the MD when we combined data and used forest plots to compare results across studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For future updates of this review, we plan to undertake subgroup analyses of children versus adults, (partially) supervised versus unsupervised training and according to disease severity, provided there is a sufficient number of studies (about 10) with at least moderate heterogeneity in the pooled analyses. Moreover, in the future, we plan to undertake subgroup analysis comparing studies performed in the 'new' era of CF medicine (i.e. after widespread availability of CF transmembrane conductance regulator modulator therapy) from 2020 onwards to those conducted before 2020.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis to investigate whether heterogeneity affected the overall pooled effects estimates by excluding from the pooled analysis individual studies that gave rise to methodological concerns. We restricted sensitivity analysis to primary outcomes. In future updates of this review (i.e. when more studies can be combined for meta‐analysis), we plan to perform two additional sensitivity analyses: with and without quasi‐randomised studies (not yet possible); and excluding studies with a high risk of bias from the analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We summarised the main findings of this review, including a grading of the certainty of evidence, in Table 1. We selected the following seven outcomes to report (chosen based on relevance to clinicians and consumers):

exercise capacity (VO2 peak);

Lung function measured as FEV1;

HRQoL: Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire – Revised (CFQ‐R) physical functioning domain;

HRQoL: CFQ‐R respiratory symptoms;

pulmonary exacerbations;

diabetic control;

adverse events.

We determined the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We downgraded evidence in the presence of a high risk of bias in at least one study, indirectness of the evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of results, or high probability of publication bias. We downgraded evidence by one level if we considered the limitation to be serious, and by two levels if very serious.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

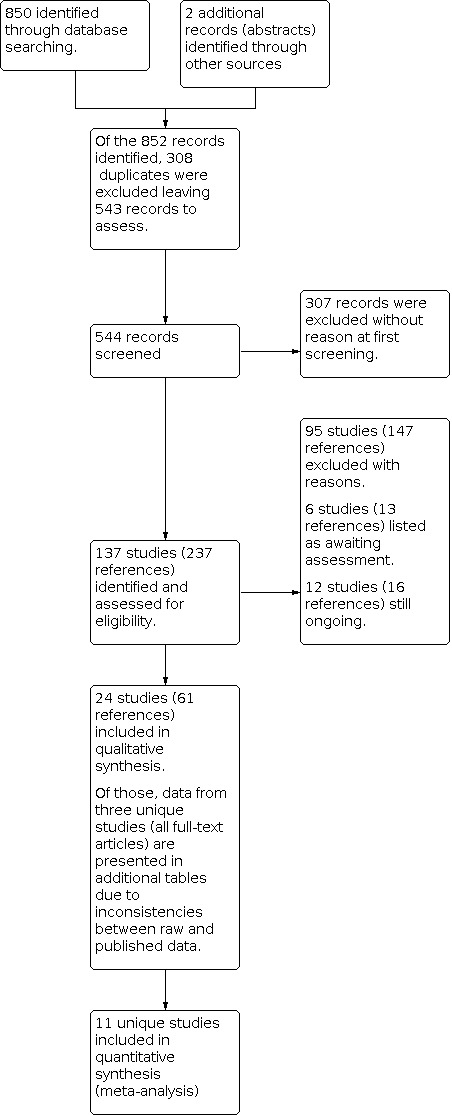

Results of the search

The combined searches to date have identified 544 individual references. After initial screening to exclude those references which were obviously not eligible, 137 unique studies are listed in the review. We included 24 studies (61 references); excluded 95 studies (147 references; for further details, see Excluded studies); six studies (13 references) are currently awaiting classification; and 12 studies (16 references) are ongoing. Please see the study flow chart for details (Figure 3).

3.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A total of 24 studies with 875 participants met the inclusion criteria (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Cerny 1989; Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Douglas 2015; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Michel 1989; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991).

Three review authors (TR, HH and SK) were lead investigators of the ACTIVATE‐CF trial (Principal Investigator Helge Hebestreit), and had full access to the data before the publication of the main manuscript. The data were included in this review, and during the process of preparing this review update, the paper was accepted for publication and is appropriately cited (Hebestreit 2022). Two other review authors (SS and SN) conducted data extraction and management for this study.

Trial characteristics

All included studies were of a randomised parallel‐group design. The study by Beaudoin and colleagues was registered as a randomised cross‐over study (ClinicalTrials.gov), but results were reported as a randomised parallel‐group design in the final publication (Beaudoin 2017). There were 20 single‐centre studies (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Cerny 1989; Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Douglas 2015; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Michel 1989; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991). Three studies were national, multicentre studies: two were conducted in Germany and Switzerland (Hebestreit 2010; Kriemler 2013), and one in Australia (Sawyer 2020). One study was an international, multicentre study across eight countries in Europe and North America (Hebestreit 2022). The size of trials varied, from a minimum number of nine participants (Michel 1989), to a maximum of 117 participants (Hebestreit 2022). One study did not report the number of participants in each group and the MD between the treatment and control groups could not be calculated (Michel 1989).

There was wide heterogeneity in study designs, with 12 studies using a supervised training approach (Carr 2018; Cerny 1989; Donadio 2020; Douglas 2015; Güngör 2021; Klijn 2004; Michel 1989; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991); 11 studies using a partially supervised approach (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Del Corral 2018; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Kriemler 2013; Rovedder 2014; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000); and one study using an unsupervised training approach (Moorcroft 2004).

The length of physical activity intervention varied substantially across the 24 studies. In 14 studies, the active intervention (either supervised, partially supervised or unsupervised but with access to study resources) lasted up to and including six months, while in 10 studies, it lasted longer than six months. Seven of the included studies implemented an additional follow‐up period (i.e. a period where supervision was withdrawn and participants received usual care and were not specifically discouraged from undertaking physical activity); these lasted from one to 12 months.

Four studies had active interventions of short duration (less than one month) and were carried out during hospitalisations (Cerny 1989; Michel 1989; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991). In Turchetta 1991, the hospital admission was for routine assessment; in Cerny 1989 and Selvadurai 2002, the hospital admission was due to an acute exacerbation requiring intravenous antibiotic treatment; and in Michel 1989, the reason for and the duration of admission were not reported. Four studies had active intervention periods lasting approximately eight weeks (Donadio 2020; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020). Both Santana‐Sosa studies had a two‐month active training period, plus a one‐month follow‐up period 'off training' during which the participants did not engage in supervised physical activity (described in the papers as "detraining") (Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014). Donadio 2020 and Sawyer 2020 were both fully supervised physical activity interventions. Five studies had an active intervention period of three months and were either home‐based (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Hommerding 2015; Rovedder 2014), or performed at the hospital (Klijn 2004). Klijn 2004 also included a three‐month follow‐up. In the study by Güngör and colleagues, the active intervention lasted for six months. A therapist supervised the first six weeks. Afterwards, the families were encouraged with weekly telephone calls to continue their child's exercise programme until the six‐month study visit (Güngör 2021).

In 10 studies, the active interventions lasted longer than six months. Del Corral 2018 was a 12‐month study including a six‐week, home‐based, physical activity intervention with video games. After six weeks, the participants were encouraged to continue video gaming exercise, supervised by their parents or caregivers. Two studies were of 24 months' duration in total with 12 months of active interventions and 12 months of follow‐up (Hebestreit 2010; Kriemler 2013). After six months of supervised or partially supervised physical activity, the participants in the intervention groups were no longer supervised but were encouraged to maintain or increase their activity level while retaining access to the study resources, while participants in the control groups were told not to change their exercise behaviour during the first 12 months. After 12 months, all participants reverted to usual care for a follow‐up period (Hebestreit 2010; Kriemler 2013). In Hebestreit 2010, investigators combined the three‐ and six‐month study visits and six‐ to 12‐month follow‐up visits. In Kriemler 2013, all study visits were reported separately in the original publication (i.e. three, six, 12 and 24 months). For the purpose of this review, we included the data from six, 12 and 24 months (i.e. after 12 months' follow‐up). Carr 2018 was a nine‐month intervention study comparing face‐to‐face versus Internet‐delivered Tai Chi lessons. The Internet group started the intervention three months later than the face‐to‐face group; the Internet group served as the control group in this review and we reported data at the three‐month time point only up to which the control group received no active intervention. In four studies, the active intervention lasted 12 months (Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2022; Moorcroft 2004); in one study 24 months (Douglas 2015); and in one study three years (Schneiderman‐Walker 2000).

In total, seven studies undertook follow‐up periods where all participants reverted to usual care, with these lasting between one and 12 months (Hebestreit 2010; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Michel 1989; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Selvadurai 2002).

Participants

Two studies included adults only (Beaudoin 2017; Moorcroft 2004); 12 studies included children and adolescents only (Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Douglas 2015; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991), eight studies included both adults and children (Carr 2018; Cerny 1989; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Kriemler 2013; Michel 1989; Rovedder 2014; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000); one study included prepubertal children (Alexander 2019); and one study included adolescents (15 years and older) and adults (Sawyer 2020). Overall, the studies included participants with a broad range of disease severity.

Most studies included participants of both sexes (Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Douglas 2015; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991). However, no information was available for three studies (Alexander 2019; Cerny 1989, Michel 1989). A total of 17 studies provided information about the proportion of male and female participants at baseline (Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Kriemler 2013; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Selvadurai 2002; Turchetta 1991).

In 10/20 studies published as full‐text articles, FEV1 % predicted values were used as exclusion criteria (Beaudoin 2017; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000); this was also true for the study available only in abstract form and trial register entry on ClinicalTrials.gov (Douglas 2015). The remaining eight studies published as full‐text articles did not specify disease severity based on FEV1 as an exclusion criterion (Carr 2018; Cerny 1989; Del Corral 2018; Hommerding 2015; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014; Sawyer 2020; Selvadurai 2002). No information was available from the remaining five studies, which were only published as abstracts (Alexander 2019; Donadio 2020; Hatziagorou 2019; Michel 1989; Turchetta 1991).

In four studies, the authors reported differences in baseline characteristics of the participants despite randomisation (Cerny 1989; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014). In Cerny 1989, lung function, measured as FEV1 and forced mid‐expiratory flow 25% to 75% (FEF25–75), was significantly lower in the control compared to the physical activity group at admission. In both Santana‐Sosa studies, the physical activity groups had a lower aerobic exercise capacity (VO2 peak) and lower muscle strength (most but not all strength measures) (Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014). In Rovedder 2014, there was a significantly lower BMI in the intervention group compared to the control group.

In Kriemler 2013, the control group experienced an unusual deterioration of physical health during the study, and the results should be interpreted with caution. In Del Corral 2018, mean modified shuttle walk test (MSWT) distance in the intervention group was 823.5 (SD 270.6) m and in the control group was 1085.5 (SD 255.6) m. The study did not report differences between groups in MSWT distance. Our own calculations using the Review Manager 5 software revealed a difference between groups at baseline (MD ‒262 m, 95% CI ‒425.1 to ‒98.86; P = 0.003). The authors adjusted for baseline values in their statistical analysis (Del Corral 2018). In Güngör 2021, the physical activity group appeared to have lower HRQoL (respiratory symptoms and physical functioning domain) compared to controls (MD of approximately 15 units to 20 units), but the authors reported that no significant difference existed in baseline characteristics between groups. This might be due to the small sample size and large SDs.

Interventions

As the aim of this review was to assess the efficacy of any type of physical activity intervention versus no physical activity intervention (usual care), we excluded studies which exclusively involved respiratory muscle training. All 24 studies included a control group which did not receive a prescribed physical activity programme.

Three studies had three study arms and compared different types of physical activity programmes (endurance training or resistance training or resistance training with neuromuscular electrical stimulation) with a control group (Donadio 2020; Kriemler 2013; Selvadurai 2002).

Five studies compared a training programme with short bouts of intense activity to a control group (Alexander 2019; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Klijn 2004; Sawyer 2020). Alexander 2019 compared a 12‐week whole‐body vibration training programme to control; Gupta 2019 compared a 12‐month home‐based physical activity programme, including strengthening exercises and plyometric jumping exercises, to a control group; and Sawyer 2020 compared an eight‐week cycling‐based high‐intensity interval training programme to a control group (Sawyer 2020). Klijn 2004 compared a 12‐week exercise programme including short (20 seconds to 30 seconds) intense exercises to normal daily activities. Güngör 2021 investigated the effects of a six‐week pulmonary rehabilitation programme, including active cycle of breathing techniques and postural exercises, compared with an active cycle of breathing techniques but no additional physical activity programme. After the six‐week intervention, children and parents were encouraged with weekly telephone calls to continue with the exercises for the following six months (Güngör 2021).

Five studies compared endurance type activities alone to a control group (Cerny 1989; Hommerding 2015; Michel 1989; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Turchetta 1991).

In 10 studies, investigators compared the effects of a combined training programme (a mixture of endurance type and resistance training or strengthening activities) to a control group (Beaudoin 2017; Del Corral 2018; Douglas 2015; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014). Beaudoin 2017 investigated a 12‐week combined endurance and resistance training programme compared to no training. Del Corral 2018 evaluated the efficacy of a six‐week video game programme, including a variety of physical activities such as running, squats, lunges and biceps curls; the intervention group participants were encouraged to continue the programme for 12 months. Douglas 2015 and Hatziagorou 2019 investigated individually tailored supervised or partially supervised physical activity programmes in children with CF over 12 months (Douglas 2015) and 24 months (Hatziagorou 2019). Hebestreit 2010 compared an individualised physical activity programme, including endurance‐type exercises, strengthening exercises or a combination of both regimens, with a control group over 24 months; the control group was simply encouraged to maintain their level of activity over 12 months. Hebestreit 2022 was a 12‐month individualised and partially supervised programme aimed at increasing vigorous activities using a combination of endurance‐type and strengthening exercises. Moorcroft and colleagues evaluated the effects of a 12‐month individualised, unsupervised physical activity training programme, including a combination of both endurance and resistance activities (Moorcroft 2004). Rovedder 2014 used unsupervised home‐based training with endurance and strengthening exercises over 12 weeks. Santana‐Sosa 2012, in hospitalised participants, compared supervised endurance and strengthening exercises, three times per week to a control group who were only informed of the benefits of exercise; both groups received the same chest physiotherapy during the entire study period. Santana‐Sosa 2014 compared an eight‐week combined programme (endurance and strength), including additional inspiratory muscle training, with a control group.

Carr 2018 compared Tai Chi programme to a control group for nine months.

In two studies, all participants additionally received intravenous antibiotic treatment (Cerny 1989; Selvadurai 2002).

Outcomes

The most commonly reported outcome measure was the change in FEV1, which all reported studies except reported (Alexander 2019; Del Corral 2018; Klijn 2004; Michel 1989). Fourteen studies documented the change in VO2 peak (Beaudoin 2017; Douglas 2015; Gupta 2019; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002). One study reported changes in VO2 at the anaerobic threshold following a physical activity intervention (Donadio 2020), and one study reported changes in VO2 during a submaximal constant work rate exercise test (Sawyer 2020). Sixteen studies reported change in HRQoL (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Del Corral 2018; Güngör 2021; Gupta 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Sawyer 2020; Selvadurai 2002), and 10 studies reported change in muscle strength (Beaudoin 2017; Del Corral 2018; Donadio 2020; Hebestreit 2010; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Rovedder 2014; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Selvadurai 2002). Sixteen studies reported change in body composition (Alexander 2019; Beaudoin 2017; Carr 2018; Del Corral 2018; Hatziagorou 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Klijn 2004; Kriemler 2013; Michel 1989; Moorcroft 2004; Santana‐Sosa 2012; Santana‐Sosa 2014; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002). Eight studies reported change in physical activity (Beaudoin 2017; Gupta 2019; Hebestreit 2010; Hebestreit 2022; Hommerding 2015; Kriemler 2013; Schneiderman‐Walker 2000; Selvadurai 2002), and five studies reported the change in other indices of exercise capacity (other than cardiopulmonary exercise testing) (Cerny 1989; Güngör 2021; Hommerding 2015; Moorcroft 2004; Rovedder 2014). Two studies reported changes in diabetic control (Beaudoin 2017; Hebestreit 2022), and two studies reported changes in bone health after the intervention (Alexander 2019; Gupta 2019). Six studies reported on adverse events (Del Corral 2018; Güngör 2021; Hebestreit 2022; Kriemler 2013; Sawyer 2020; Selvadurai 2002). Only one study reported the number of pulmonary exacerbations and time to first pulmonary exacerbation (Hebestreit 2022). No study reported hospitalisations.

Excluded studies

We excluded 95 studies for the following reasons.

A total of 24 studies were not RCTs (Andreasson 1987; Asher 1982; Balfour Lynn 1998; Barry 2001; Bongers 2015; Cantin 2005; de Jong 1994; Edlund 1986; Heijerman 1992; Hütler 2002; IRCT20161024030474N4; Moola 2017; NCT02277860; NCT02715921; NCT03117764; Orenstein 1981; Petrovic 2013; Pryor 1979; RBR‐34677v; Ruddy 2015; Salh 1989; Stanghelle 1998; Tuzin 1998; White 1997). Thirty‐eight studies did not include a physical activity programme according to our protocol (ACTRN12620001237976; Alarie 2012; Albinni 2004; Amelina 2006; Aquino 2006; Balestri 2004; Bellini 2018; Bieli 2017; Bilton 1992; Chang 2015; Chatham 1997; Combret 2018; Combret 2021; Cox 2013; Dwyer 2011; Falk 1988; Giacomodonato 2015; Happ 2013; Haynes 2016; Irons 2012; Kaak 2011; Lannefors 1992; Macleod 2008; Montero‐Ruiz 2020; NCT02199340; NCT02821130; NCT02875366; Ozaydin 2010; Patterson 2004; Rand 2012; Reix 2012; Salonini 2015; Spoletini 2020; Vallier 2016; Vivodtzev 2013; Ward 2018; Young 2019; Zeren 2019). There were 19 studies which did not use a control arm with 'no physical activity' (Bass 2019; Calik‐Kutukcu 2016; de Marchis 2017; del Corral Nunez‐Flores 2014; Gruber 1998; Gruet 2012; Kaltsakas 2021; Kuys 2011; Lang 2019; Lima 2014; Lowman 2012; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; NCT01759342; NCT04888767; NTR2092; Orenstein 2004; RBR‐5g9f6w; Reuveny 2020; Shaw 2016). Five studies were acute exercise studies and of insufficient duration (less than 14 days) to be included in this review (Dwyer 2017; Dwyer 2019; Kriemler 2016; Radtke 2018b; Wheatley 2015). Seven studies had a lack of information: the investigators of two studies informed us that no paper will be published and data were not available (Mandrusiak 2011; NCT00792194); an investigator of one study did not reply to our email request for more information about the study status and planned publication (Oliveira 2010); and for four studies, contact details could not be found online to contact study investigators (Almajan‐Guta 2011; Housinger 2015; Johnston 2004; Phillips 2008). Two studies were excluded for other reasons: one study focused on proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation in children with chronic respiratory diseases (this type of training aims to improve flexibility and range of motion; it is not considered a type of physical activity intervention that is expected to elicit improvements in the outcomes listed in our review and therefore not relevant for this review) (NCT03420209); and for one study, the last status update on ClinicalTrials.gov was posted in 2005 (NCT00129350), and it is unlikely that this study will be published in the future (if published data are found in future literature searches, the study will be considered for inclusion in the review).

Studies awaiting classification

There are six studies awaiting classification (Bishay 2017; Cox 2019; IRCT20190407043190N1; NCT03100214; NCT04293926; Powers 2016).

Trial characteristics

All six studies awaiting classification were of a randomised parallel‐group design. Two studies were multicentre (Cox 2019; IRCT20190407043190N1), and four were single‐centre studies (Bishay 2017; NCT03100214; NCT04293926; Powers 2016). The study size (i.e. enrolment goal if actual number of participants was not available) ranged from 19 to 80 participants (Bishay 2017; Cox 2019; IRCT20190407043190N1; NCT03100214; NCT04293926; Powers 2016).

All studies reported inclusion and exclusion criteria (Bishay 2017; Cox 2019; IRCT20190407043190N1; NCT03100214; NCT04293926; Powers 2016). One study enrolled adults (aged 18 years and older) (Bishay 2017), two studies enrolled children and adolescents (IRCT20190407043190N1; NCT04293926), and three studies enrolled adolescents and adults (Cox 2019; NCT03100214; Powers 2016).

Interventions

There was great variety between studies with respect to physical activity modalities and approaches. One study employed a combined aerobic and anaerobic home‐based training programme (Powers 2016). One study investigated a four‐week combined aerobic and anaerobic training programme, but the setting was not entirely clear from the registry entry (IRCT20190407043190N1). One study was conducted with participants hospitalised for treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation (NCT03100214). One study investigated the efficacy of a 12‐week web‐based application for improving participation in physical activity compared to usual care following hospitalisation for a respiratory exacerbation (Cox 2019). In another study, participants received an activity monitor (Fitbit) to measure physical activity and were followed over one year, completing surveys and exercise tests. Participants in the control group received usual care and were offered Fitbits after the first year (Bishay 2017). One study aimed to assess the effects of an eight‐week resistance training programme on the variability in heart rate in children and adolescents with CF versus usual care (i.e. routine recommendations, including lifestyle recommendations) (NCT04293926).

Outcomes

Five studies defined changes in FEV1 after the physical activity intervention as a secondary study outcome (Bishay 2017; Cox 2019; NCT03100214; NCT04293926; Powers 2016). Four studies reported on functional exercise capacity using a graded exercise test (Bishay 2017), the 6MWT (NCT03100214), or shuttle test (Cox 2019; Powers 2016). Four studies reported changes in HRQoL (Bishay 2017; Cox 2019; IRCT20190407043190N1; Powers 2016). Two studies included physical activity (Cox 2019; Powers 2016).

Ongoing studies