Abstract

Telehealth (TH) is defined as the entire spectrum of activities used to deliver care remotely. It could either be provider-to-patient or provider-to-provider communications. TH can take place synchronously (via telephone and video), asynchronously (via patient portal messages, e-consults), and through virtual agents (chat) and wearable devices. It has been used to support access to specialised medical advice in remote areas in many countries all over the world. We discuss the potential use of TH Clinics in Sudan and propose guidance for establishing such services. The current pandemic of SARS-COVID-19 has increased the pressure on most health systems. This has challenged and urged for significant changes in the way we provide health care for both COVID and non-COVID cases. There is a great potential for improvement in services in many countries including Sudan with the use of TH.

Keywords: Telehealth, Sudan, SARS-COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

Telehealth (TH) is defined as the entire spectrum of activities used to deliver care remotely [1]. It could either be provider-to-patient or provider-to-provider communications and has been used to support access to specialised medical advice in remote areas in many countries all over the world. Sudan, a 1.8 million square kilometres country, with a population of 41 million, is a developing country with an under-resourced health care service. Sudan’s infrastructure of mobile phone network and landlines is variable from one area to another. Mobile phone users constitute 72% of people, and most towns have good mobile network coverage but not so good internet services. The use of speedy internet services would be very challenging at this stage.

The crisis of COVID-19 pandemic has created great challenges for the health care services worldwide but even more on the limited-resources countries. Therefore, diversion of resources towards providing emergency care to those affected by the disease was needed. Unfortunately, the price was a reduction of outpatients and elective services. Lots of hospitals and healthcare personnel went out of service and the demand of patient care was ever increasing. This was the best time to start delivering TH service with government support.

Elements of telehealth clinics

Elements of TH include the use of mobile communication devices to provide clinical consultation service through mobile health (M-health), Videoconferencing (V-health) and communication with patients in an integrated manner combined with additional online tools to improve accessibility and quality of care [2].

Requirements of telehealth clinics

For TH clinics to operate efficiently, significant service reorganisation and logistic support are required [3,4]. Appropriate selection of patients is of paramount importance as it does not suit all patients. Good mobile or landline networks and fast speed internet connections, depending on the service used, are the cornerstones of TH. A quiet and well-lit area for the phone/video consultation is mandatory. There are still some complex challenges to establish wide virtual consultation services within different routine practices in many sectors [5] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Requirements of telehealth clinics.

| Platform | Technology requirements | Opportunities | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient initiated texting | High Tech infrastructure | Handling clear issues | Needs staffing Potential lack of context |

| Phone calls | Minimum | Universally accessible Cost- effective Easy and quick |

No physical exam |

| Video-Conference | Moderate. Requires WiFi connection, a smart device with good camera and a microphone | Allows visible inspection Allows for non-verbal cues |

Could be time consuming and costly |

| Tele-health softwares | Complex | Confidential Allows visual inspection |

Time and high Tech required, Cost |

| Video-Visit (e.g. for in patients during COVID-19) | Complex Requires Wi-Fi connection, a smart device with good camera and a microphone |

Allows visual and verbal consultation | May need digital peripherals, e.g stethoscope. Needs infection control re: devices used |

Options of telehealth in Sudan

WhatsApp chats

WhatsApp is currently used widely as a form of communication between patients and doctors and amongst doctors when seeking advice from a colleague or when sharing knowledge. It has the advantages of being accessible and easy to use (in many towns) in addition to sharing videos and images. However, there are huge concerns regarding patients’ confidentiality.

Virtual phone clinics

In our opinion, phone clinics should be the starting point to TH in Sudan. Helped with the relatively good mobile network coverage in most areas and fixed lines in others, it has the potential to form the base for the future of TH in Sudan. Improvements in internet services and upgrading of the current network to faster WiFi connections and 5G mobile network would add a significant boost to TH.

Emails and texting

The use of emails can also help in TH in Sudan. However, we need to recognise that it is an asynchronous way of TH and would not suit all.

Telehealth platforms

Unfortunately, this is not feasible in Sudan at the moment. It is currently used in countries with good telecommunication infrastructures. There are multiple platforms providing TH support services such as attend anywhere. These platforms are used to connect clinicians and patients using video links. Most only require both patient and healthcare provider to access a smart phone or computer with a webcam and have a fast-speed internet connection and a private well-lit area to allow uninterrupted consultation.

How do these platforms work?

If the patient agrees to have their appointment via video conferencing, they will then receive a letter and/or a text message with the link to the virtual waiting room on the website for their appointment.

On the day and time of the appointment, the patient or their carers 77 logs to the site through the link. They will be asked to confirm their demographic details such as their name, date of birth and contact phone number.

The healthcare providers will see them arriving, so they will join them in the video room for the consultation.

At the end of the appointment, the healthcare provider will disconnect the call and the web page will close.

Telehealth clinics worldwide experiences

Advances with the internet offered a great opportunity to improve long distance communication. Telemedicine using real time videoconferencing had allowed for valuable direct interaction. On the other hand, though, asynchronous telemedicine using e-mails or specially designed websites was considered a cheaper and a much more flexible method in both time and place [6]. In The Netherlands, telemedicine has been used successfully in dermatology consultations avoiding long waiting times for a dermatologist`s opinion in out-patient clinics when referred by general practitioners (GPs) [6]. In Australia, telemedicine was used widely in health care. Since 1996, Tele-health services have been growing steadily and in 2002 there were over 30,000 Tele-radiology transmissions and 1,250 clinical occasions of service via videoconferencing [7]. Appropriately targeted video consultation has much potential to improve the delivery of primary health care in Australia, particularly in rural and remote regions [8]. The same was noticed in India where virtual clinics were considered a new concept. Virtual clinics were promising and had seemed to be of great benefit especially in rural areas where access to specialised medical advice could be difficult [9].

In Paediatrics, a Dutch randomised controlled study showed that implementing frequent virtual asthma clinic had improved asthma control and increased symptoms-free days significantly when compared with conventional outpatients’ clinics [10].

Steps for conducting the telehealth clinic via phone

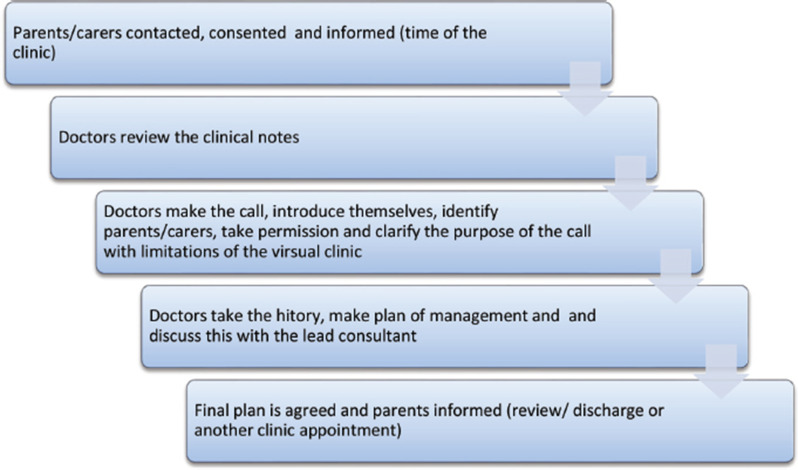

Telehealth starts with the department administrative staff contacting the patients’ carers/parents through phone/mobile messaging or call system to inform them about the assigned times and date for the virtual clinics appointments. The parents/carers will be asked to give consent to be enrolled and to record the weight and height for the child awaiting the appointment and have it to hand during the scheduled appointment (if they have weighing scales and measuring tapes, or if they have a recent measurements). The clinical notes of the patients are made available on the day of the clinic with the contact details on the front of the notes. The virtual clinics are then conducted by the team lead by the responsible consultant. The doctors in the clinic will review patients’ charts and then contact the parent/carer using outpatient department phones calling the recorded mobile /phone numbers of parents/carers of patients during the scheduled time. The phone calls will involve identifying the patients’ and carers names and the purpose of the call. After confirming identity of receiver of the call then a consent is to be taken for pursuing the call as a part of TH procedure. Doctors should explain the limitations of the TH clinic; as it does not involve clinical exam or face to face interaction. The doctor then takes the history and proceeds in the consultation as usual. The doctor will make a plan of treatment and follow-up and convey to the parent/carer after discussing it with the consultant. This could be ordering investigations, referrals to other specialties or scheduling a ward review appointment where patients can be seen and examined when it is necessary. The doctor ensures documenting the visit and the outcome with the follow-up plan. In our centre, we have used the virtual clinic opportunity to give medical advice to parents /carers regarding keeping healthy during COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps for conducting the telehealth clinic via phone.

Limitations of telehealth clinics

Telehealth clinics are limited by the inability to examine patients (inspection is only possible in case of video-based clinics). Confidentiality is also a concern. Telehealth does not give us the chance to respond to patients /carers nonverbal cues. There are concerns that TH clinics may affect doctor-patient relationship, so advised patient should not have two successive TH clinics. Some challenges which face TH in Sudan include social and cultural acceptability as parents prefer face to face consultation, lack of administrative support, issues with sending or collecting prescriptions and issues with billing in cases of private sector patients. Connection stability could be an issue as well, in cases of internet and even phone clinics. Importantly, TH clinics are not suitable for new referrals, acute conditions and some specialised clinics such as orthopaedics and cardiology.

CONCLUSION

Virtual clinics and telemedicine have been used in the past widely in different specialties and proved to be helpful and effective in reducing patient’s costs, improve accessibility and reducing need for face to face interactions with HCWs in hospital settings. During the current pandemic of COVID-19, virtual clinics have gained more focus. Despite some understandable limitations, virtual clinics can represent a feasible alternative to conventional outpatients’ clinics in this challenging time of COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual clinics when used appropriately can allow continuation of patient’s care, improve accessibility and reduces the risk of nosocomial transmission. In Sudan’s setting, there is huge potential for TH although this would be limited by administrative support and cultural acceptability.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

No ethical approval was required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, Gellad ZF, Cho A, Phinney D, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(6):957–62. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krausz M, Ward J, Ramsey D. From Telehealth to an Interactive Virtual Clinic. In: Mucic D, Hilty D, editors. e-Mental health. Switzerland: Springer, Cham; 2016. pp. 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20852-7_15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parish T, Ratnaraj M, Ahmed TJ. Virtual clinics in the present – a predictor for the future? Future Healthc J. 2019 Jun;6(Suppl. 2):37. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s37. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, Barber J, Thompson S, Jacklin P, et al. Joint teleconsultations (virtual outreach) versus standard outpatient appointments for patients referred by their general practitioner for a specialist opinion: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9322):1961–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08828-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw S, Wherton J, Vijayaraghavan S, Morris J, Bhattacharya S, Hanson P, et al. Southampton. UK: NIHR Journals Library; 2018. Advantages and limitations of virtual online consultations in a NHS acute trust: the VOCAL mixed-methods study. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr06210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eminović N, de Keizer NF, Wyatt JC, ter Riet G, Peek N, van Weert HC, et al. Teledermatologic consultation and reduction in referrals to dermatologists: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(5):558–64. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.44. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillon E, Loermans J. Telehealth in Western Australia: the challenge of evaluation. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(Suppl 2):S15–9. doi: 10.1258/135763303322596147. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763303322596147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raven M, Butler C, Bywood P. Video-based telehealth in Australian primary health care: current use and future potential. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(4):283–6. doi: 10.1071/PY13032. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY13032. PMID: 24134865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angrish S, Sharma M, Bashar MA, Tripathi S, Hossain MM, Bhattacharya S, et al. How effective is the virtual primary healthcare centers? An experience from rural India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(2):465–9. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1124_19. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1124_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Wijngaart LS, Roukema J, Boehmer ALM, Brouwer ML, Hugen CAC, Niers LEM, et al. A virtual asthma clinic for children: fewer routine outpatient visits, same asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1700471. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00471-2017. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00471-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]