Abstract

Background:

Acute gastroenteritis (GE) is a clinical syndrome and harbours a significant global burden. Nosocomial acquisition of gastroenteritis results in a significant economic burden. We aim to determine gastroenteritis frequency, disease severity, nosocomial acquisition and clinical spectrum in our region for 2016-2017.

Methods:

This is a prospective study of all children up to 3 years of age who presented to Mayo University Hospital with vomiting and diarrhoea, from 18 November 2016 to 18 November 2017. All children had their clinical severity of gastroenteritis assessed using the internationally recognised Vesikari scoring system.

Results:

A total of 159 cases were detected, 157 were studied, 87 were male (55%) and 90 were severe (57%). Nosocomial gastroenteritis is rare (2 cases) (1.1%); 129 cases were admitted and the majority of paediatric gastroenteritis cases (68%) stayed between 1 and 2 days. Diarrhoea was noted in all cases, vomiting in 130 cases (82%), fever in 136 cases (86%) and dehydration in 89 cases (56%). Oral rehydration therapy was successful in 33 cases (21%). The fourth week of June was the peak week of the year for gastroenteritis (7 cases). The largest number of presentations with GE was noted in May (20 cases), followed by December and June (18 cases each) with the largest number of severe GE noted in June (12 cases), followed by December and May (11 cases each).

Conclusion:

Diarrhoea is the most predominant feature of gastroenteritis. Acute viral gastroenteritis occurs throughout the year. Seasonal variations of gastroenteritis were noted throughout the year. Nosocomial infection is rare.

Keywords: Paediatric, Health services, Gastroenteritis, Mayo University Hospital, Northern Ireland

INTRODUCTION

Acute gastroenteritis (GE) is a clinical syndrome often defined by increased stool frequency (e.g., ≥3 loose or watery stools in 24 hours or a number of loose/watery bowel movements that exceeds the child’s usual number of daily bowel movements by two or more), with or without vomiting, fever or abdominal pain [1-4], occurs throughout the year, with a fall (autumn) and winter predominance [5,6,7-9]. Vomiting usually lasts for 1-2 days and diarrhoea for 5-7 days [2,5,6,10].

In a study on acute viral GE from a tertiary care children’s hospital between 2006 and 2009, diarrhoea was present in 90%; the median duration of diarrhoea was 6 days (interquartile range = 3-14); and the median maximum number of stools per day was six (interquartile range = 4-10). Vomiting was present in 56%; the median duration of vomiting was 4 days (interquartile range = 2-6); and the median maximum number of episodes of emesis per day was three (interquartile range = 2-5). Fever (>38.3°C) was present in 42% [5]. Acute viral GE may be complicated by dehydration and hypoglycaemia [1-4,10,11]. The burden of GE is substantial. There is direct impact of admission costs on hospital budget and direct and indirect societal costs when children are admitted to a hospital: days off work being most noteworthy, childcare costs etc. In a systematic analysis of the global burden of diarrhoeal diseases conducted in one study [12], diarrhoea was the eighth leading cause of death among all ages and the fifth leading cause of death among children younger than 5 years of age.

Nosocomial infections are mainly associated with infants up to 5 months of age. Rotavirus (RV) was found to be the major etiologic agent of paediatric nosocomial diarrhoea (31-87%) [13]. In a Swedish study that recruited 604 children <5 years of age from 3 geographical areas, admitted to hospital with RV-induced GE, 49 out of 604 (8.1%) fulfilled the criteria for nosocomial infection [14].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 18 November 2016 to 18 November 2017, recruited in this study were all children up to 3 years old who attended the emergency department (ED) or were admitted to Mayo University Hospital (MUH) with vomiting and diarrhoea (loose stool) or diarrhoeal symptoms. The cohort also included admitted children who developed diarrhoea 3 days (72 hours) after their admission to the paediatric ward, possible nosocomial gastroenteritis (NGE), or readmitted to the paediatric ward within 48 hours following recent discharge, possible NGE. Children presenting with chronic diarrhoea due to other diseases, e.g., immunodeficiency or inflammatory bowel disease or presenting with the same diagnosis within a 48-hour period, were excluded. In total, four children were excluded.

Stool samples were tested by real-time polymerase chain reaction for viral pathogens (rotavirus, adenovirus, norovirus, astrovirus and sapovirus) at the National Virus Reference Laboratory in Dublin.

The internationally recognised Vesikari scoring system was used to assess disease severity [15]. The Vesikari clinical scoring system was applied to all children presenting with GE to our regional hospital – on a daily basis for the whole period of the study. Senior house officers were given training on the method of assessment of GE severity using the Vesikari scoring system. They were provided with copies of the scoring system. Wherever possible, the scoring system was checked again on the following day to ensure that the scoring process was conducted effectively.

Based on the Vesikari scoring system, GE was classified into mild, moderate and severe forms. Hospital admission in our study was defined as a period of at least one night stay.

A number of parameters were used in the Vesikari scoring system. Any score below 7 was defined as mild GE; scores between 7 and 10 were defined as moderate GE; equal to or higher than 11 were defined as severe GE. No scores were given for any parameter that was not present or was not applicable (N/A) at the time of assessment. The highest score was 20.

In our study, data are presented in relation to the total number of children with GE, expressed as a percentage of the total number of paediatric admissions; total number of children up to 3 years of age with GE, expressed as a percentage (%) of the total number of children with GE; and total number of admissions with GE in children up to 3 years of age, as a percentage in relation to the total number of paediatric admissions and percentage of GE in children up to 3 years of age as a proportion of the total number of paediatric attendances to the ED.

Data are also presented in relation to GE-related length of hospital stay, clinical spectrum of GE, vomiting (number per day and duration in days), diarrhoea (number per day and duration in days), temperature (37.1°C–38.4°C, 38.5°C–38.9°C and >38.9°C), management (oral rehydration therapy, ORT), hospitalisation and intravenous fluid therapy.

RESULTS

Viral gastroenteritis-related admissions, clinical presentation and management

During the prospective study period (18 November 2016 to 18 November 2017), almost 8,000 children presented to the ED at MUH; 1,111 were admitted and 55% were male. Respiratory diagnosis was the lead cause of admissions (41%). GE was the second leading cause of paediatric admissions (182 cases) (16%); 129 children (71%) were ≤3 years old. The total number of children ≤3 years of age who attended to ED with GE was 159 (2% of the total number of children attending the ED, which was 7,827).

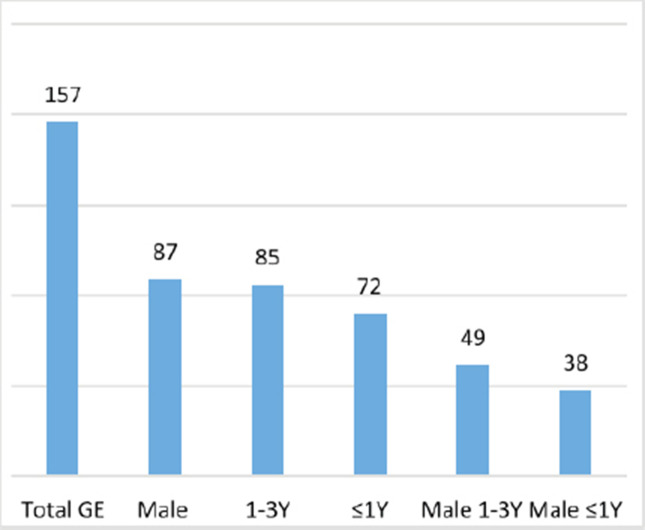

During the study period, 157 patients were diagnosed with GE, after excluding 2 females who presented twice during the study period with GE; 87 were male (55%); 85 patients were between 1 and 3 years of age (54%), of whom 49 were male (56% of the total male number) and 36 were female (51%); 72 were aged ≤1 year (46%), of whom 38 patients were male (44% of the total male number) and 34 (49%) patients were female (Figure 1). The median age at presentation was 15 months.

Figure 1.

Gastroenteritis cases age and gender (2016–2017). GE, gastroenteritis; Y, year.

NGE was only reported in two cases (1.1%): one case was a 10-month-old female with complex cardiac problems detected during the fourth week of April; no viral pathogen was detected; case was of moderate severity; and she remained hospitalised for 3 weeks. The second case was a 25-month-old male with I-cell disease; case was severe; rotavirus was detected; he was hospitalised for 4 weeks; detected during the third week of July. Viral illness was detected in 110 patients (9%); urinary tract infection in 42 children (4%); other causes for admission were noted in 343 patients (30%).

Gastroenteritis length of hospital stay

During the prospective study period, 128 patients were admitted (82%) and 1 readmitted [total number of admitted children aged up to 3 years = 129), of whom 66 were male (51%) and 70 (54%) were aged between 1 and 3 years. Further analysis of their demographics revealed six children of non-Irish origin, four ≤1 year, three severe GE, one mild, one moderate and one of unknown severity due to a language barrier. Among the 129 patients admitted, 81 (63%) had severe GE, 41 (32%) moderate and 6 (5%) mild. Expectedly, the majority of paediatric GE cases (68%) stayed between 1 and 2 days, 23% between 2 and 3 days and 9% for more than 4 days. The highest number of children admitted with GE in 1 month was noted in May and June: 18 and 15, respectively. The least number of children admitted with GE in 1 month was noted in September.

Clinical spectrum

During the prospective study period, 159 cases of GE were detected. Clinical scoring was not applicable in one patient due to a language barrier. Therefore, 158 cases were studied for clinical spectrum using the Vesikari clinical scoring system; 90 cases were severe. Vomiting was a predominant feature of paediatric GE, noted in 82%, with a duration mostly between 1 and 3 days (62%). The median % of the frequency of vomiting was more than four per day (30%). Diarrhoea was noted in all 158 children. The majority of children had diarrhoea for a period between 1 and 4 days (82%); 58% of the children had episodes of diarrhoea between 1 and 3 times per day.

Fever was noted in 86% of the children with GE; >38.5°C was present in 34%. Half of the children were mildly dehydrated at presentation; 69 patients were not dehydrated (44%). Greater than 5% dehydration was detected in 10 patients (6%). ORT was only successful in the management of GE in 21% (33 patients). Intravenous fluids were administered to the remaining 79% of the children (125 patients).

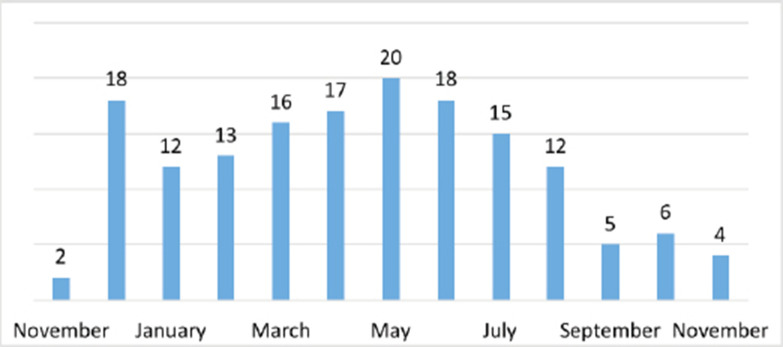

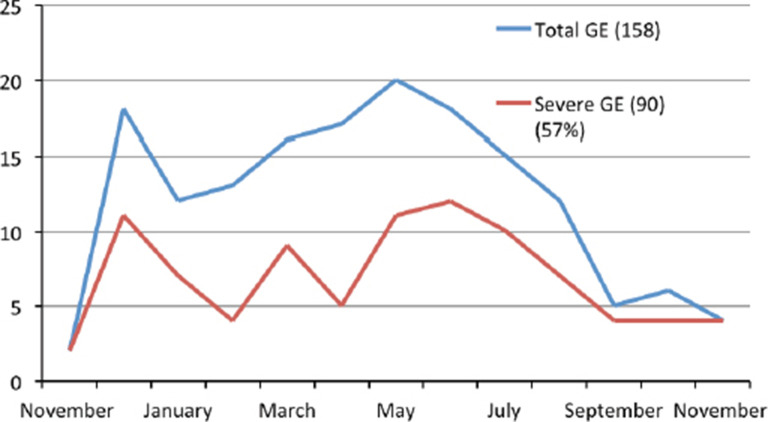

Seasonal variation

The fourth week of June was the peak week of the year, during which seven cases of GE presented; all admitted. Four were male, followed by the second week of April, the first week of May, the first week of August and the fourth week of December (six patients in each month). The largest number of presentations with GE (Figure 2) was noted in May (20 cases), followed by December and June (18 cases each) with the largest number of severe GE noted in June (12 cases), followed by December and May (11 cases each). In total (Figure 3), 90 cases were severe (57%), 57 were moderate (36%) and 11 were mild (7%).

Figure 2.

Gastroenteritis monthly figures.

Figure 3.

Gastroenteritis monthly figures and severity. GE, gastroenteritis.

DISCUSSION

Acute viral GE may be complicated by dehydration [1-4,10,11], as shown in our study (56%). Our study supports the findings of others that vomiting usually lasts for 1–2 days [2,5,6,10] and that diarrhoea is the most predominant feature of GE [5]. Fever (>38.3°C) was present in 42% in one study [5], whereas in this study, fever was noted in 34%. Acute viral GE occurs throughout the year, with a fall and winter predominance [5,7-9]; seasonal variability of GE was also noted in this study.

Nosocomial infections are mainly associated with infants up to 5 months of age. Rotavirus (RV) was found to be the major etiologic agent of paediatric nosocomial diarrhoea (31–87%) [13]. In a Swedish study that recruited 604 children <5 years of age from 3 geographical areas, admitted to hospital with RV-induced GE, 49 out of 604 (8.1%) fulfilled the criteria for nosocomial infection [14]. Unlike other studies that demonstrated a high rate of nosocomial infection [14], this study, surprisingly, showed that nosocomial GE was rare and was detected in two cases, among 150 samples (1.1%). The low rate of nosocomial RV infections in our study may be attributed to a small sample size over a short period of study, limited by recruiting patients from only one geographical area in Ireland. Adhering to strict local policies of hygienic measures in our unit may also have a positive effect in reducing the rate of nosocomial RV infection. Of the 157 patients who were studied with GE, about 82% of the patients were admitted (129, including 1 readmitted patient) and 63% were severe GE. The majority of admitted children were of Irish origin (123 patients, 95%) and between 1 and 3 years old (54%). All admitted children received intravenous fluids following unsuccessful ORT. Other demographics, such as income, education and employment, are not applicable due to the very young age factor in this study. Due to a small sample size of this cohort (129 patients), it is not possible to risk stratify them. Additional research in a larger geographical location in Ireland with a larger sample size is required to enable risk stratification of children with GE in an attempt to develop a management pathway.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first prospective study to address the clinical spectrum of GE in a regional Irish context. We have demonstrated the seasonal variations of GE and assessed its clinical severity using internationally recognised scoring tools.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Consent was obtained and parents were given the right to choose to withdraw or opt out of the research at any time. A certificate of ethical approval for the research study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethical Committee at MUH before study commencement (Ref: TOM/DP).

REFERENCES

- 1.Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: update 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:132. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000375. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diarrhoea and vomiting in children: Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis: diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years; 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. Vol. 52. MMWR Recomm Rep; 2003. Duggan, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; p. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velázquez FR, Matson DO, Calva JJ, Guerrero L, Morrow AL, Carter-Campbell S, et al. Rotavirus infection in infants as protection against subsequent infections. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351404. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199610033351404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborne CM, Montano AC, Robinson CC, Schultz-Cherry S, Dominguez SR. Viral gastroenteritis in children in Colorado 2006-2009. J Med Virol. 2015;87:931. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colomba C, De Grazia S, Giammanco GM, Saporito L, Scarlata F, Titone L, et al. Viral gastroenteritis in children hospitalised in Sicily, Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:570. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0188-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-006-0188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chhabra P, Payne DC, Szilagyi PG, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Shirley SH, et al. Etiology of viral gastroenteritis in children <5 years of age in the United States, 2008–2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:790. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit254. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall AJ, Rosenthal M, Gregoricus N, Greene SA, Ferguson J, Henao OL, et al. Incidence of acute gastroenteritis and role of norovirus, Georgia, USA, 2004–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1381. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.101533. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1708.101533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman CM, Bresee JS, Parashar UD, Riggs TL, Holman RC, Glass RI. Cost of diarrhea-associated hospitalizations and outpatient visits in an insured population of young children in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:14. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200101000-00004. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivière M, Baroux N, Bousquet V, Ambert-Balay K, Beaudeau P, Jourdan-Da Silva N, et al. Secular trends in incidence of acute gastroenteritis in general practice, France, 1991 to 2015. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(50):17–00121. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.50.17-00121. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.50.17-00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady K. Acute gastroenteritis: evidence-based management of pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2018;15(2):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troeger C, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, Rao PC, Cao S, Zimsen SR, et al. GBD 2016 Diarrhoeal Disease Collaborators Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease. The Lancet Infect.Dis. 2018;18(11):1211–28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30362-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleizes O, Desselberger U, Tatochenko V, Rodrigo C, Salman N, Mezner Z. Nosocomial rotavirus infection in European countries: a review of the epidemiology, severity and economic burden of hospital-acquired rotavirus disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis J. 2006;25(1 Suppl):S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000197563.03895.91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000197563.03895.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinder M, Tran AN, Bennet R, Brytting M, Cassel T, Eriksson M, et al. Burden of severe rotavirus disease leading to hospitalization assessed in a prospective cohort study in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(4):294–302. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.876511. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365548.2013.876511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim DH, Kim DY, Cho KY. Diagnostic value of the Vesikari Scoring System for predicting the viral or bacterial pathogens in pediatric gastroenteritis. Korean J Pediatr. 2016;59(3):126–31. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.3.126. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2016.59.3.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]