ABSTRACT

The regulated uptake and consumption of d-amino acids by bacteria remain largely unexplored, despite the physiological importance of these compounds. Unlike other characterized bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, which utilizes only l-Asp, Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 can consume both d-Asp and l-Asp as the sole carbon or nitrogen source. As described here, two LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs), DarR and AalR, control d- and l-Asp metabolism in strain ADP1. Heterologous expression of A. baylyi proteins enabled E. coli to use d-Asp as the carbon source when either of two transporters (AspT or AspY) and a racemase (RacD) were coexpressed. A third transporter, designated AspS, was also discovered to transport Asp in ADP1. DarR and/or AalR controlled the transcription of aspT, aspY, racD, and aspA (which encodes aspartate ammonia lyase). Conserved residues in the N-terminal DNA-binding domains of both regulators likely enable them to recognize the same DNA consensus sequence (ATGC-N7-GCAT) in several operator-promoter regions. In strains lacking AalR, suppressor mutations revealed a role for the ClpAP protease in Asp metabolism. In the absence of the ClpA component of this protease, DarR can compensate for the loss of AalR. ADP1 consumed l- and d-Asn and l-Glu, but not d-Glu, as the sole carbon or nitrogen source using interrelated pathways.

IMPORTANCE A regulatory scheme was revealed in which AalR responds to l-Asp and DarR responds to d-Asp, a molecule with critical signaling functions in many organisms. The RacD-mediated interconversion of these isomers causes overlap in transcriptional control in A. baylyi. Our studies improve understanding of transport and regulation and lay the foundation for determining how regulators distinguish l- and d-enantiomers. These studies are relevant for biotechnology applications, and they highlight the importance of d-amino acids as natural bacterial growth substrates.

KEYWORDS: ADP1, Acinetobacter baylyi, DarR, LTTR, LysR, aspartate, racemase, regulation, transport

INTRODUCTION

The role of d-Asp as a physiological signaling molecule in diverse vertebrates and invertebrates is evidenced by a wide range of neuroendocrine effects (1). In humans, d-amino acids arise from bacterial sources and impact health and disease (2). In bacteria, d-amino acids are key components of peptidoglycan. Additionally, they affect processes such as sporulation, biofilm formation, and some types of symbioses (3). An increased awareness of their biological importance led to renewed attention to the microbial production of d-amino acids, especially by lactic acid bacteria (4).

Studies have also addressed the microbial degradation of d-amino acids and the bioavailability of these compounds in nature (5). Nevertheless, many details of d-amino acid uptake and consumption remain unclear. We previously showed that a genetically malleable, saprophytic soil bacterium, Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 (6, 7), requires a LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR), DarR, to grow on d-Asp as the carbon source (8). This regulator responds to d-Asp to activate transcription of racD, which encodes an aspartate racemase, and an adjacent transporter gene, here designated aspT. Sequence analysis indicates that AspT belongs to a large protein family of bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic dicarboxylate/amino acid:cation symporters (DAACS) (Pfam PF00375) (9). Based on genetic context in diverse bacteria (8), AspT likely transports d-Asp, although this function has not been demonstrated.

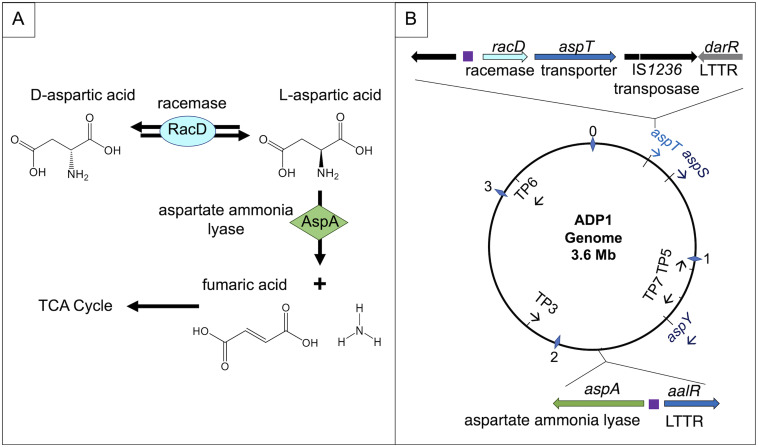

We sought to clarify the coordination of d-Asp metabolism with that of l-Asp. Growth of A. baylyi on d-Asp as the carbon source depends on RacD, suggesting that l-Asp is formed and then cleaved by aspartate ammonia lyase (AspA) (Fig. 1A). In the A. baylyi chromosome, aspA is divergently transcribed from an LTTR gene predicted to affect transcription of its own gene as well as aspA (Fig. 1B) (8, 10). The encoded LTTR was designated AalR (for aspartate ammonia lyase regulator). An LTTR also regulates aspA transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that does not grow on d-Asp as the sole carbon or nitrogen source (11). Similarities between AalR and DarR in A. baylyi raise questions about the recognition and response of each protein to d-Asp and/or l-Asp. Additional questions arise as to the recognition of different operator-promoter sequences, as the N-terminal DNA-binding domains of DarR and AalR share 83% amino acid sequence similarity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

d- and l-Asp catabolism pathway and genes in A. baylyi ADP1. (A) d-Asp is converted to l-Asp by a racemase, RacD. Next, l-Asp is cleaved by a lyase, AspA. Fumarate is further metabolized in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. (B) The racD gene (ACIAD_RS01510) is adjacent to a gene (ACIAD_RS01515), designated aspT, predicted to encode a d-Asp transporter. The chromosomal positions and orientations of aspT and six additional genes encoding paralogous transport proteins (TP) (Fig. S2) are indicated. (The distance from the origin in megabases is indicated by numbered diamonds.) Two of the TP genes (TP2 and TP4) were renamed aspY and aspS. As described in the text, our data support a regulatory scheme in which two LTTRs, DarR and AalR, control a regulon that includes aspA, racD, aspT, and aspY. Purple boxes indicate operator-promoter regions upstream of aspA and the racD-aspT operon that are subject to LTTR-activated transcription.

Mutants were constructed to determine whether AalR or DarR can substitute for the loss of the other. Growth phenotypes were tested using both enantiomers of Asp, Glu, and Asn as carbon or nitrogen sources. Regulatory effects were investigated using transcriptional fusions, transcript characterization, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). To test the role of transporters in d-Asp uptake, A. baylyi proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli, which naturally consumes l-Asp but not d-Asp. These studies demonstrated the presence of two d-Asp-inducible transporters in A. baylyi, suggesting that d-Asp is a significant nutrient in the natural environment of this bacterium.

RESULTS

Potential Asp transporters in ADP1.

The loss of darR or racD from ADP1 prevents growth on d-Asp, but not l-Asp, as the carbon source (8). Here, we deleted aspT (ACIAD_RS01515) to test its role in d-Asp uptake. The resulting ΔaspT mutant was designated ACN2035 (strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1; additional details are provided in Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material). ACN2035 grew comparably to wild-type ADP1 on l-Asp (Fig. 2A, patches in region 1 compared to those in region 4). On d-Asp, the aspT mutant grew with a delay relative to the wild type. After 1 day, patches were visible for the wild type but not the mutant (Fig. 2B). Therefore, AspT may play a role in d-Asp transport.

TABLE 1.

A. baylyi strains and plasmidsa

| Strain or plasmidb | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ADP1 | Wild-type strain (BD413UE) | 38 |

| ACN1260 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | This study |

| ACN1280 | ΔaalR51280 | This study |

| ACN1726 | ΔdarR51726 | 8 |

| ACN1894 | aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 | This study |

| ACN1895 | ΔaalR51280 aspA::gfp-ΩKr51883 | This study |

| ACN2035 | ΔaspT52035 | This study |

| ACN2059 | aspY::ΩS52059 | This study |

| ACN2061 | ΔaspT52035 aspY::ΩS52059 | This study |

| ACN2140 | ΔaalR::darR52140 ΔdarR51726 | This study |

| ACN2141 | ΔaalR::darR52141 ΔdarR51726 | This study |

| ACN2144 | aspY::lacZ-Kmr52144 | This study |

| ACN2153 | ΔaalR::darR52141 aspA52153(PaspA52153) ΔdarR51726 ACN2141-derived d-Asp+ spontaneous mutant | This study |

| ACN2180 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 clpA52180d | This study |

| ACN2197 | ΔaalR::darR52141 aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 ΔdarR51726 | This study |

| ACN2208 | aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 aspA52153(PaspA52153) | This study |

| ACN2209 | ΔaalR1280 aspA52153(PaspA52153) aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 | This study |

| ACN2222 | aspA52153(PaspA52153) aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 ΔdarR51726 ΔaalR::darR52141 | This study |

| ACN2246 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 clpA::ΩS52246 | This study |

| ACN2247 | ΔaalR51280 clpA::ΩS52246 | This study |

| ACN2278 | ΔaalR51280 aspA52153(PaspA52153) aspA::gfp-ΩK51883 ΔdarR51726 | This study |

| ACN2917 | ΔaalR51280 clpA52917d | This study |

| ACN2921 | ΔaspT52035 aspY::ΩS52059 aspS52921(PaspS*) ACN2061-derived spontaneous d-Asp+ mutant | This study |

| ACN2926 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 clpA52926d | This study |

| ACN2927 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 clpA52927d | This study |

| ACN2928 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 clpA5928d | This study |

| ACN2952 | ΔdarR51726 racD2947(PracD_trc52947) | This study |

| ACN2957 | ΔdarR51726 racD2947(PracD_trc52947) ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | This study |

| ACN2964 | aspS::lacZ-Kmr52964 | This study |

| ACN2967 | aspS::lacZ-Kmr52964 ΔaspT52035 aspY::ΩS52059 | This study |

| ACN2969 | aspS52921(PaspS*) aspS::lacZ-Kmr52964 ΔaspT52035 aspY::ΩS52059 | This study |

| ACN2984 | aspY::lacZ-Kmr52144 ΔdarR51726 ΔracD52953 racD52947(PracD_trc52947) | This study |

| ACN2987 | aspS::lacZ-Kmr52964 ΔaspT52035 | This study |

| ACN2988 | aspS::lacZ-Kmr52964 aspY::ΩS52059 | This study |

| ACN2989 | aspY::lacZ-Kmr52144 ΔaalR51280 ΔracD52953 racD2947(PracD_trc52947) | This study |

| Plasmidsc | ||

| pJPK13 | Kmr; expression vector | 41 |

| pBAC1673 | Kmr; racD and aspT sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1680 | Kmr; racD sequence from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1683 | Kmr; aspT sequence from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1941 | Kmr; racD and aspY sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1942 | Kmr; racD and ACIAD_RS10205 (TP3) sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1943 | Kmr; racD and aspS sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1944 | Kmr; racD and ACIAD_RS04730 (TP5) sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1945 | Kmr; racD and ACIAD_RS14645 (TP6) sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pBAC1946 | Kmr; racD and ACIAD_RS05475 (TP7) sequences from ADP1 in pJPK13 | This study |

| pET21b | Apr; expression vector | Novagen |

| pBAC1057 | Apr; aalR coding sequence was inserted (as a PCR product that was digested with NdeI and XhoI) into pET21b; used to express C-terminally His-tagged AalR protein | This study |

Additional details about the construction of strains and plasmids, including intermediary constructs used to engineer the final versions, are reported in Table S1.

A. baylyi strains were derived from ADP1, previously known as Acinetobacter calcoaceticus or Acinetobacter sp. (7).

E. coli strain DH5α (39) was used to express ADP1 proteins encoded on plasmids.

See Table 2.

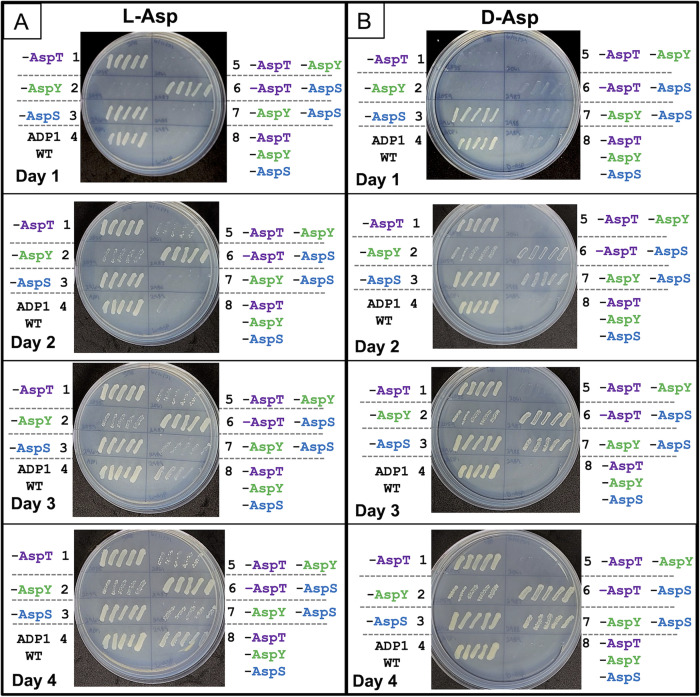

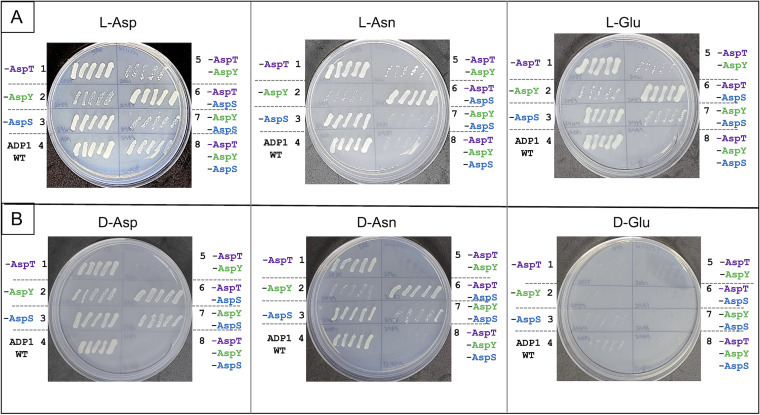

FIG 2.

Patched colonies of the wild type (WT) and aspT, aspY, and aspS mutants. Five comparably sized pyruvate-grown colonies were taken from a single plate for each strain and patched in the same position on a plate with l-Asp (A) or d-Asp (B) as the carbon source. Photographs were taken after 1, 2, 3, and 4 days of incubation (from top to bottom) at 37°C. Patches on other plates, including a final plate with LB medium as a positive control, are not shown here. The following strains are in these regions of each patched plate: 1, ACN2035, no AspT; 2, ACN2059, no AspY; 3, ACN2964, no AspS; 4, ADP1, WT; 5, ACN2061, no AspT or AspY; 6, ACN2987, no AspT or AspS; 7, ACN2988, no AspY or AspS; 8, ACN2967, no AspT, AspY, or AspS.

To determine if redundant uptake specificity of different transporters permitted growth of the aspT mutant, we searched for similar protein sequences. Six paralogs of AspT were identified in ADP1 (Fig. S2). These putative transport proteins (TPs) were termed TP2 to TP7, in descending order of similarity to AspT (corresponding to TP1 [Fig. S2]). In pairwise alignments with AspT, the sequence identities are 61% for TP2 (later named AspY), 38% for TP3, 36% for TP4 (later named AspS), 32% for TP5, 30% for TP6, and 24% for TP7.

Inactivation of the gene most like aspT, ACIAD_RS06160, impaired growth on Asp, and the gene was designated aspY. Loss of this gene, unlike aspT, caused poor growth on l-Asp (Fig. 2A, region 1 compared to region 2). On d-Asp, the individual aspY and aspT mutants grew similarly to each other, but slower than ADP1 (Fig. 2B, regions 1, 2, and 4). A double mutant, unable to produce AspT or AspY, failed to grow on d-Asp even after prolonged incubation (Fig. 2B, region 5). This strain, ACN2061, grew on l-Asp as the carbon source, albeit slowly (Fig. 2A, region 5). Collectively, these results suggest that AspY transports l-Asp and d-Asp, whereas AspT transports d-Asp. AspY and AspT together may account for all typical d-Asp transport, as the loss of both precludes growth on this carbon source.

Selection of a spontaneous mutant that grows on d-Asp without AspY or AspT.

To obtain ACN2061-derived spontaneous mutants capable of growing on d-Asp, cultures of this strain were grown on different substrates to induce transport proteins that might provide an initial growth advantage after transfer to selective medium. Each ACN2061 culture was grown with either a dicarboxylic acid (l-Asp, l-Glu, adipate, or succinate) or with pyruvate as the carbon source. Cells were concentrated and spread on plates with d-Asp as the carbon source. d-Asp+ colonies arose (at a frequency of 6 × 10−10), but only when the inoculating culture was grown on l-Asp. One such mutant, designated ACN2921, was characterized further.

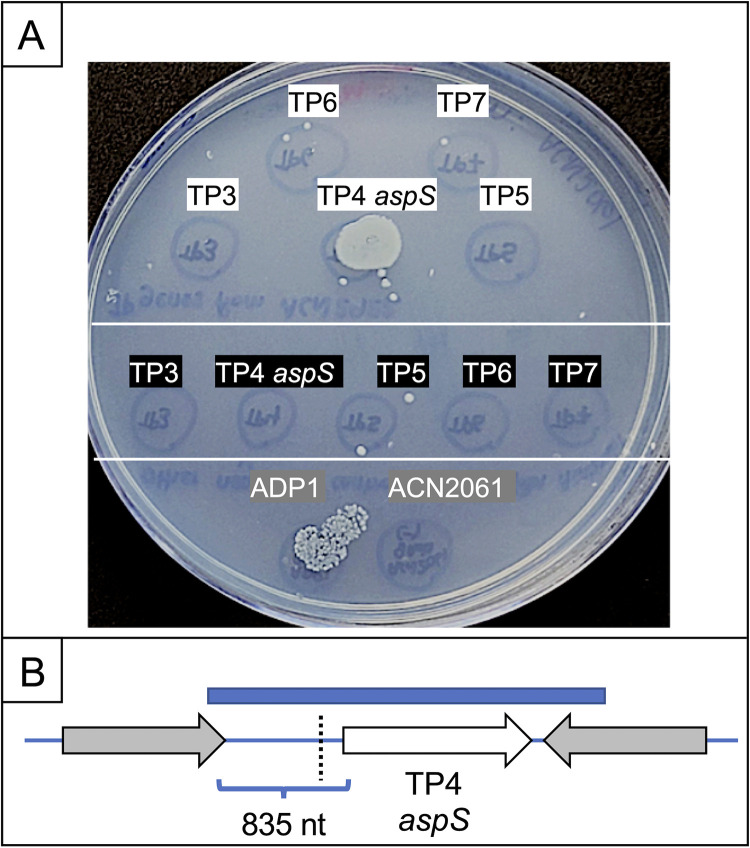

A transformation assay tested if mutations in any of the TP3 to TP7 genes could account for growth on d-Asp without AspY or AspT. The high efficiency of natural transformation and homologous recombination in A. baylyi allows allelic replacement when linear DNA is added to a recipient strain (12). Cell-free DNA of the TP genes, amplified from genomic DNA of the d-Asp+ mutant (ACN2921), was dropped on its d-Asp− parent. Transformants grew on a d-Asp plate in spots where donor DNA introduced a compensatory genetic change (Fig. 3). d-Asp+ transformants arose with donor DNA from the TP4 gene (ACIAD_RS02190) of ACN2921 but not from comparable DNA of the parent strain (Fig. 3A). DNA sequencing revealed only one point mutation in the TP4 DNA of ACN2921 that confers growth (blue rectangle in Fig. 3B). This mutation, upstream of the TP4 coding sequence, was in a position that could affect transcription. Based on a possible role in Asp metabolism, TP4 was renamed AspS.

FIG 3.

Transformation assay. (A) ACN2061 (lacking AspY and AspT) was spread on a plate with d-Asp as the carbon source. This recipient, which is d-Asp−, grew only in 2 of 12 spots where specific cell-free donor DNA was dropped and could generate transformants in which the donor DNA replaced the corresponding chromosomal region of the recipient. PCR fragments were made with genomic template DNA from ACN2921 (d-Asp+). PCR products that each encompass the sequence of genes for TP3, TP4, TP5, TP6, or TP7 were dropped in spots (white labels with black text). Comparable fragments, made with genomic template DNA from ACN2061, were dropped in spots (black labels with white text). At the bottom, genomic DNA from ADP1 (able to reintroduce aspT and aspY) and DNA from ACN2061 served as positive and negative controls, respectively. (B) Schematic of the relative positions of the TP4 (aspS) coding sequence (white arrow), the PCR product (blue rectangle) used in the transformation assay, and a mutation (dotted line) identified in ACN2921. At this position, 200 nt upstream of the aspS coding sequence, the wild-type sequence (GTTTA) is altered by the insertion of one extra T (GTTTTA). This mutation (allele aspS52921) creates a variant aspS promoter (PaspS*). No mutations occurred in the aspS (TP4) coding sequence of ACN2921.

High gene expression of aspS enables growth on d-Asp without AspY or AspT.

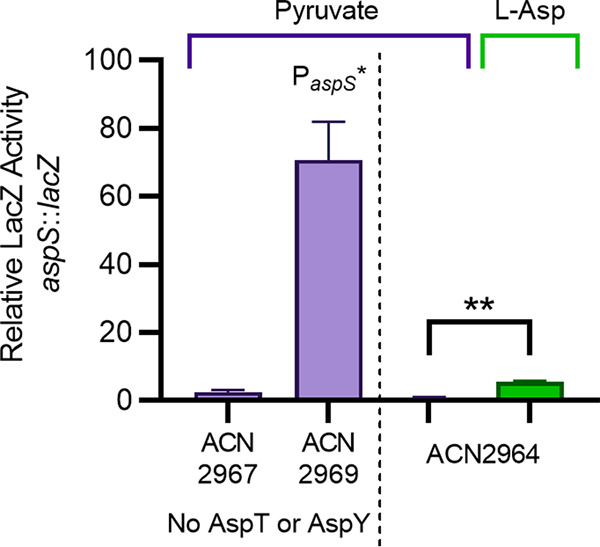

A lacZ transcriptional fusion was engineered to disrupt the chromosomal copy of aspS in ACN2921. The resulting aspS mutant (ACN2969) was d-Asp−, indicating that AspS is required for growth of ACN2921 on d-Asp without AspY or AspT. Since spontaneous d-Asp+ mutants arose only when the inoculum was grown on l-Asp, we tested if l-Asp normally induces AspS by comparing levels of aspS transcription in cells grown on Asp versus pyruvate. Growth on l-Asp of ACN2964, which has an aspS::lacZ fusion in an otherwise wild-type chromosome, resulted in higher LacZ activity than did growth on pyruvate. Transcription from the wild-type aspS promoter (PaspS) increased approximately 5-fold in response to growth on l-Asp, a relatively low but significant value (t test value, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). In ACN2964, l-Asp can be metabolized to d-Asp and other compounds, which makes it impossible to discern the true inducer.

FIG 4.

LacZ expression from the wild-type aspS promoter (PaspS) in ACN2967 and ACN2964 or the mutated promoter (in ACN2969), which was identified in the d-Asp+ mutant (allele aspS52921, PaspS* [Fig. 3]). Each strain has a chromosomal aspS::lacZ transcriptional reporter. LacZ activity is shown relative to that of ACN2964, which is otherwise wild type, grown on pyruvate (150 Miller units). Purple bars indicate that strains were grown on pyruvate as the sole carbon source. The green bar corresponds to LacZ activity when ACN2964 was grown on l-Asp as the sole carbon source. Error bars show the standard deviation from at least three biological replicates, each with two technical replicates. The significance in a t test of ACN2964 grown on pyruvate compared to the same strain grown in l-Asp is indicated by ** (P < 0.0001).

Expression of the aspS::lacZ reporter was also compared in two pyruvate-grown strains lacking AspT and AspY. LacZ activity was high for ACN2969, the reporter strain with the promoter mutation (aspS52921 [PaspS*]) (Fig. 4). The expression of LacZ controlled by this promoter was significantly higher (more than 60-fold) than it was for ACN2967, which has the wild-type PaspS. These results support the conclusion that AspS can compensate for the loss of AspT and AspY to confer d-Asp+ growth if there is a mutation that increases aspS transcription.

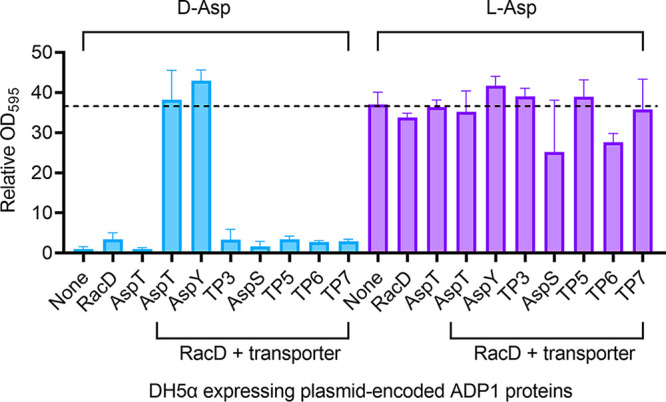

Assessing the roles of d-Asp transporters from A. baylyi ADP1 in E. coli.

We investigated whether the Asp racemase (RacD) and/or transport proteins from ADP1 (TP1 to TP7) would enable E. coli strain DH5α to grow on d-Asp (Fig. 5). The cell density of DH5α(pJPK13) in d-Asp medium was comparable to that with no carbon source, confirming that this E. coli strain (carrying a plasmid with no ADP1 DNA) is d-Asp−. We also confirmed that this strain had the expected l-Asp+ phenotype. Two plasmids (pBAC1673 and pBAC1941) conferred growth on d-Asp. Both encode RacD, a racemase not encoded by E. coli, and either AspT or AspY. AspT alone did not confer growth (Fig. 5). Similarly, expression of RacD alone did not confer growth. These results support the conclusion that AspT and AspY transport d-Asp and that racemization is needed for d-Asp consumption in E. coli.

FIG 5.

Heterologous expression of A. baylyi ADP1 proteins in E. coli DH5α. Cultures of DH5α carrying either a plasmid with no ADP1 DNA (pJPK13 [None]) or derivatives of this plasmid encoding the indicated proteins were grown in media with d-Asp (left side) or l-Asp (right side) as the carbon source. Growth measurements (OD595), taken 72 h after inoculation, are shown relative to that of DH5α(pJPK13) in d-Asp medium (OD595 = 0.03). The growth of this strain on l-Asp (OD595 = 1) is indicated by a dashed line. The following plasmids encode the ADP1 proteins indicated in parentheses: pBAC1680 (RacD), pBAC1683 (AspT), pBAC1673 (RacD and AspT), pBAC1941 (RacD and AspY), pBAC1942 (RacD and TP3), pBAC1943 (RacD and AspS), pBAC1944 (RacD and TP5), pBAC1945 (RacD and TP6), and pBAC1946 (RacD and TP7). Error bars represent the standard deviation from at least 5 biological replicates.

Regulation of d- and l-Asp catabolism in A. baylyi ADP1.

To understand the coordinated regulation of genes for d- and l-Asp catabolism in ADP1 (Fig. 1), we focused on AalR and DarR, LTTRs that are 29% identical and 54% similar in sequence (Fig. S1). We previously demonstrated that DarR mediates d-Asp-dependent transcriptional activation from the promoter for racD in Aliivibrio fischeri (formerly Vibrio fischeri) and that DarR is required by A. baylyi to use d-Asp as a carbon source (8). We predicted that AalR regulates aspA based on genomic context (8, 10). In our current studies, growth was compared for mutants missing AalR or DarR (Fig. S3). Loss of DarR prevented growth on d-Asp but not l-Asp (8). However, loss of AalR (in ACN1280) prevented growth on either enantiomer as the carbon source. Similar results were obtained from a strain in which a drug resistance cassette interrupts the aalR coding sequence (ACN1260) (Fig. S3). Therefore, we hypothesized that AspA expression requires AalR.

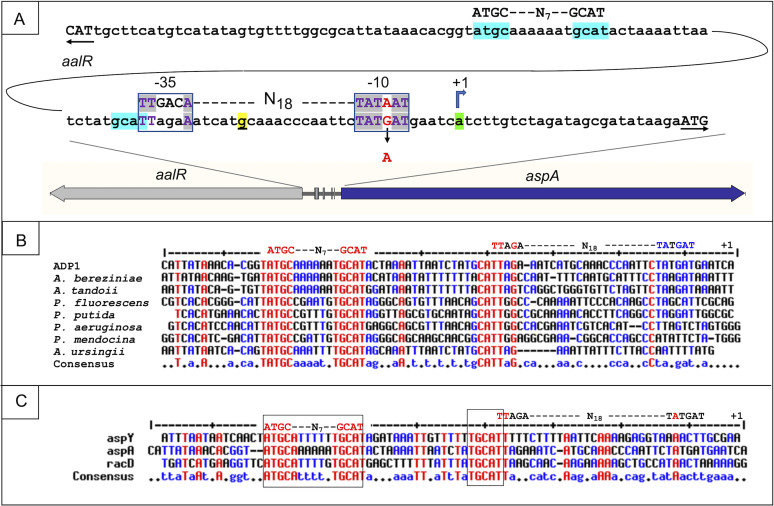

AalR binding to the aspA operator-promoter region.

We determined the aspA transcriptional start site (+1) using the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) method (13) with RNA from l-Asp-grown ADP1. Using the experimentally determined +1 site, the aspA operator-promoter sequence was aligned with comparable regions in different Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter strains (Fig. 6A and B). A conserved sequence was evident that has dyad symmetry characteristic of LTTR-binding sites, 5′-ATGC-N7-GCAT-3′. This sequence exactly matches a site upstream of racD-aspT in A. baylyi (Fig. 6C). In A. fischeri, the identical sequence binds DarR to enable d-Asp-dependent expression from the racD promoter (8, 14).

FIG 6.

Operator-promoter sequences of aspA, aspY, and racD (A) Predicted regions for AalR binding/regulation are highlighted in turquoise. Part of this highlighted region abuts the −35 portion of the aspA promoter (boxed). The promoter mutation (PaspA52153 [red text]), shown near the aspA transcriptional start site (+1 [green]), increases the resemblance to a consensus σ70 E. coli promoter, shown above the ADP1 sequence. The transcriptional start site for aalR, on the opposite DNA strand, was localized to a 45-nt region between the underlined nucleotide (yellow) and the aspA coding sequence. (B) The ADP1 aspA promoter (+1 site at the right side) is aligned with predicted aspA DNA in Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas strains. Conserved sequences are marked in red or blue, depending on how many sequences are identical. Many red sequences correspond to the regions highlighted in turquoise in panel A. The putative AalR binding site (ATGC-N7-GCAT) and the ADP1 promoter sequence are shown above the alignment. (C) The aspA sequence from panel B is aligned with regions upstream of aspY and racD in ADP1. The right-most nucleotide (top line) is the experimentally determined transcriptional start site for aspY (+1). The aspS sequence is not included because there was insufficient similarity to allow alignment.

Attempts to align these regions with sequences upstream of aspS were unsuccessful. These attempts involved searching the 835-nucleotide (nt) region upstream of the aspS coding sequence (Fig. 3) for sequences that would align with conserved regions of aspA, aspY, and racD (Fig. 6C). We additionally focused on sequences in the vicinity of the aspS5291 mutation (Fig. 3 and 4), as this nucleotide change presumably lies in a critical position of the operator-promoter region. No sequence matching ATGC-N7-GCAT, the predicted AalR/DarR binding site, was identified in a position upstream of a potential aspS promoter.

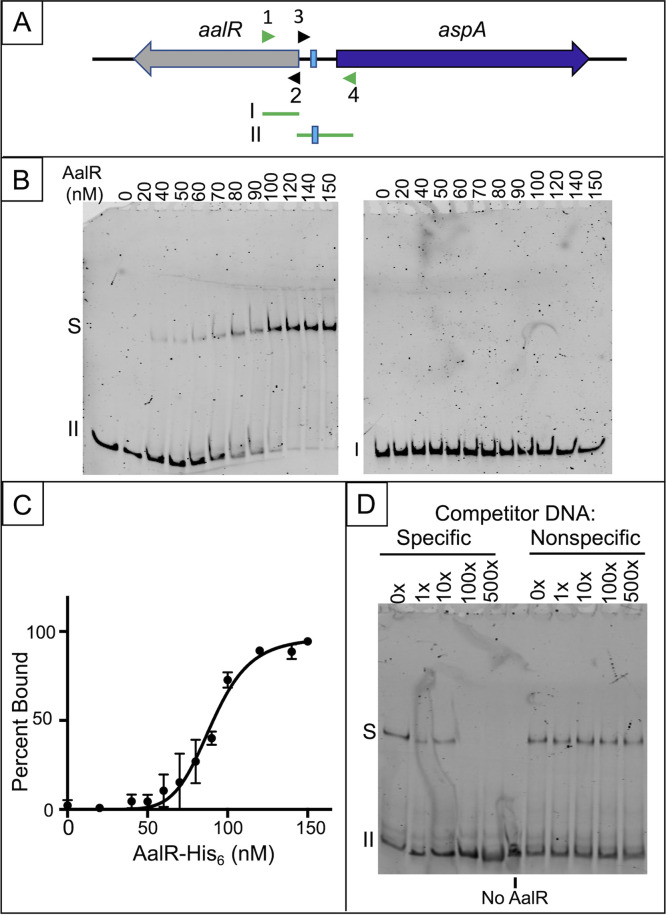

EMSAs were used to assess the binding of a purified, His-tagged regulator (AalR-His6) to two labeled DNA fragments in the aspA region of ADP1 (Fig. 7). One of these labeled PCR fragments is positioned within the aalR coding sequence (fragment I), while the other (fragment II) corresponds to the aalR-aspA operator-promoter region, including the predicted AalR binding site (ATGC-N7-GCAT) (Fig. 7A). The mobility of fragment II, but not fragment I, was shifted in the presence of AalR-His6 and 1 mM l-Asp (Fig. 7B). Binding data for interactions between AalR-His6 and fragment II revealed an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 93 ± 7 nM when calculated for a tetramer (Fig. 7C). The functional unit for AalR in solution, or when bound to its cognate DNA site, is predicted to be a tetramer based on studies of DarR from A. fischeri (14). The specificity of this interaction was tested using binding assays between labeled fragment II and AalR-His6 in the presence of unlabeled competitor DNA that was either specific (identical in sequence to fragment II) or nonspecific (sonicated herring sperm DNA) (Fig. 7D). Binding to the labeled fragment was significantly reduced in the presence of 10-fold molar excess of the specific competitor DNA relative to the labeled probe, and binding was eliminated at ≥100-fold molar excess of the specific competitor DNA (Fig. 7D). The nonspecific competitor DNA did not reduce AalR-His6 binding to fragment II, even at 500-fold molar excess (Fig. 7D). These results confirm that AalR-His6 binds specifically to the operator-promoter region of the divergently oriented aspA and aalR genes.

FIG 7.

AalR-His6 binding to the operator-promoter region of aspA assessed by EMSA. (A) Two 6-FAM-labeled PCR products were used. At the start of the aalR coding sequence, a 202-bp fragment I (made with primers 6-FAM-ALS68 and ALS67 [arrowheads 1 and 2]), has no predicted AalR-binding site. Fragment II (241 bp, made with primers ALS66 and 6-FAM-ALS65 [arrowheads 3 and 4]) contains DNA between the divergent coding sequences, including the predicted AalR binding site (turquoise highlighting in Fig. 6). (B) Binding assays used purified AalR-His6 at the indicated tetramer concentrations (nM) with fragment I or II (2 nM) in the presence of 1 mM l-Asp. A representative EMSA is shown for each fragment. Unbound DNA is indicated with the fragment number; shifted AalR-DNA complex is labeled “S.” (C) A plot of the percent AalR-His6-bound fragment II versus nM concentration of tetrameric AalR-His6 from EMSAs performed in the presence of l-Asp is shown (results from two replicate experiments; vertical bars indicate standard error). Nonlinear regression analysis of the data for saturation binding of a single site (PRISM software) provided an estimate of the Kd value (93.3 ± 6.5 nM) for AalR-His6 binding of fragment II in the presence of the effector l-Asp. (D) A representative competition EMSA assessing the specificity of AalR-His6 binding to fragment II in the presence of 1 mM l-Asp is shown. (Four replicate assays were performed.) Binding reactions were performed with 280 nM AalR-His6; the molar excess of specific (unlabeled fragment II) and nonspecific (sonicated herring sperm DNA) competitor DNA relative to the 6-FAM-labeled fragment II (2 nM) is indicated above each lane of the gel.

Because analysis of the aalR transcriptional start site was complicated by low-level transcription, we used a gene amplification method to increase the copy number of the aalR-aspA genomic region (15). This approach yielded sufficient aalR mRNA for 5′ RACE, but three RNA samples from different cultures indicated slightly different end points. The results suggest that transcription initiates in an approximately 45-nt region between one nucleotide in the aspA promoter (underlined in Fig. 6A) and the aspA coding sequence. Initiation in this region combined with AalR binding to its predicted recognition site (ATGC-N7-GCAT) is consistent with negative autoregulation, a common feature of LTTRs that are transcribed divergently to a target gene.

Suppressor mutations that allow DarR regulation of aspA in aalR mutants.

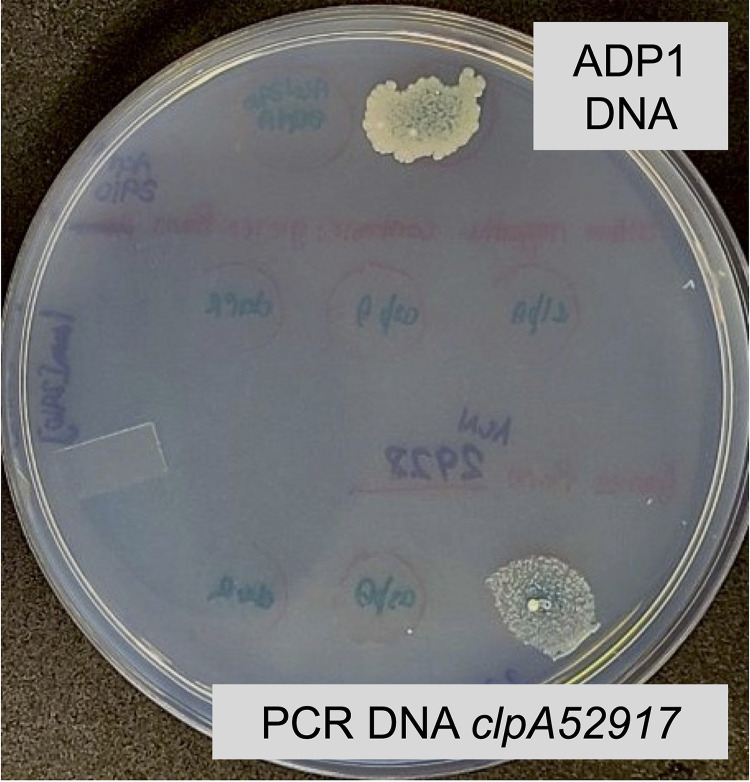

Extended incubation of aalR mutants ACN1260 or ACN1280 on l-Asp or d-Asp plates resulted in Asp+ derivatives (Fig. S3B). In one Asp+ isolate (ACN2180), whole-genome sequencing revealed a mutation in clpA (ACIAD_RS06285). Based on this result, clpA was sequenced in similar spontaneous mutants, and five different clpA alleles were discovered (Table 2). Linear DNA fragments with these clpA mutations were used to transform an aalR (Asp−) recipient. In one example of this assay (Fig. 8), d-Asp+ growth resulted when a mutated allele (from ACN2917) replaced the wild-type clpA of the recipient. This allele most likely eliminates the function of ClpA, a chaperone that contributes to protein degradation mediated by the ClpAP protease (16). To confirm that growth resulted from loss of clpA, two strains without aalR were constructed in which clpA was inactivated (ACN2246 and ACN2247). Both strains were d-Asp+, demonstrating that the loss of ClpA enables growth on this carbon source without AalR.

TABLE 2.

clpA alleles in spontaneous Asp+ mutants derived from strains without aalR

| Asp+ mutant | aalR allele of parent strain | Carbon source selection | Position of mutation in 2,277-bp coding sequence of clpA | Effect on 758-residue ClpA protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACN2180 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | l-Asp | 11-bp repeat (positions 1138–1148) | Frameshift after aa 383 |

| ACN2917 | ΔaalR51280 | l-Asp | G→T (position 82, creates TAA stop signal) | Truncates protein after 27 residues |

| ACN2926 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | Mix of l- and d-Asp | GG insertion (duplication of nt 1600 and 1601) | Frameshift after aa 533 |

| ACN2927 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | Mix of l- and d-Asp | ΔC (nt 899) | Frameshift after aa 299 |

| ACN2928 | ΔaalR::sacB-Kmr51260 | Mix of l- and d-Asp | T insertion (after nt 560) | Frameshift after aa 190 |

FIG 8.

A clpA mutation transforms a ΔaalR recipient, enabling d-Asp+ growth. A transformation assay with an ACN1280 culture spread on the surface of a d-Asp plate is shown. ADP1 DNA dropped on the bacterial lawn enabled d-Asp+ growth, presumably by allelic replacement that restores aalR. A PCR product carrying the mutated clpA allele of ACN2917 also enabled d-Asp+ growth. Additional DNA dropped on the plate in different spots failed to confer growth: PCR products carrying DNA of clpA, darR, and aspA using template DNA from the recipient, ACN1280. PCR products carrying DNA of darR and aspA from the d-Asp+ clpA mutant (ACN2917) were also dropped on as donor DNA and failed to confer d-Asp+ growth by allelic replacement.

We investigated whether the AalR-independent d-Asp+ growth of a clpA mutant requires DarR for aspA transcription. However, to understand the possible role of DarR in aspA transcription when AalR is absent, we needed to ensure expression of RacD and AspT without DarR. For this purpose, the racD promoter was replaced with a modified trc promoter that allows constitutive expression of chromosomal genes in A. baylyi (6). A strain with this constitutive promoter upstream of racD, a darR deletion, and a wild-type aalR gene (ACN2952) was d-Asp+, indicating that the modified trc promoter drives sufficient expression of RacD and AspT for d-Asp uptake and racemization. When aalR was inactivated, a strain (ACN2957) carrying all the other mutations of ACN2952 in the chromosome failed to grow on d- or l-Asp. Transformation assays were conducted using this mutant as the recipient (with no AalR, no DarR, and a constitutive promoter upstream racD and aspT). In these experiments, clpA mutations failed to confer a d-Asp+ phenotype by allelic replacement. These results indicate that mutants grow on d-Asp without AalR when ClpA is absent, but only if DarR is present.

We tested whether replacing the aalR coding sequence with that of darR would affect DarR-mediated aspA transcription. In two strains (ACN2140 and ACN2141), darR was removed from its native locus and inserted in place of aalR. These strains differed in several nucleotides at the 5′ region of darR to account for two different potential start sites for the coding sequence. While both strains failed to grow on Asp, a spontaneous d-Asp+ mutant (ACN2153), derived from ACN2141, was isolated and found to have a single-nucleotide change in the 136-bp region between the coding sequences for aspA and the divergent LTTR gene. The mutation changed the −10 region of the aspA promoter to match the consensus for E. coli (ATAAT) (Fig. 6A), creating an altered promoter designated PaspA52153.

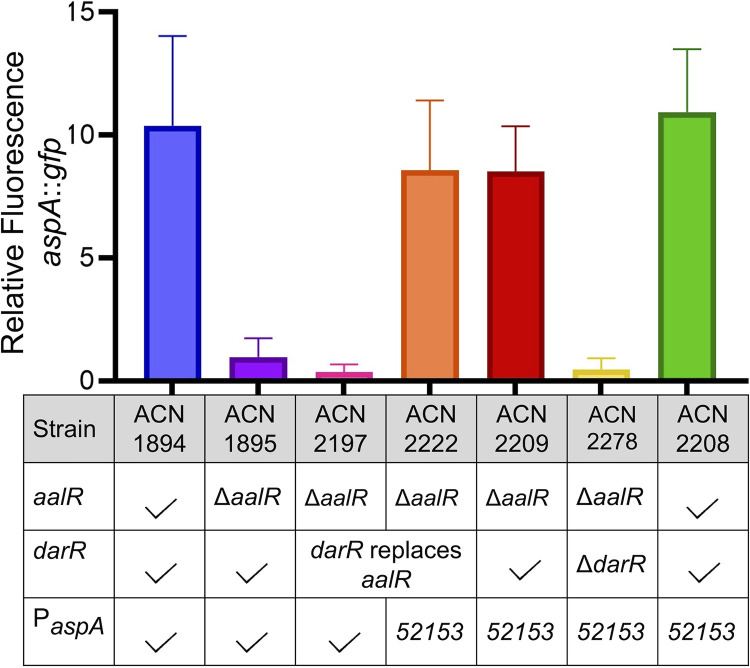

A reporter strain for aspA transcription (ACN1894) was constructed with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene inserted in aspA. The insertion prevents Asp from being used as the carbon source. Control of this transcriptional fusion (aspA::gfp) by the wild-type promoter (PaspA), led to high-level fluorescence when d-Asp was added as the inducer. In this strain, d-Asp and l-Asp can be interconverted by RacD. In a strain where aalR was deleted, Asp-mediated induction was not observed (Fig. 9, ACN1894 compared to ACN1895). The basal fluorescence level in the aalR mutant (ACN1895) was comparable to that of ACN1894 grown without Asp and to that of a strain with no gfp (ACN1280 [data not shown]). Regulation was not restored when aalR was replaced by darR (ACN2197 in Fig. 9). Thus, AalR (and not DarR) appears to be an Asp-responsive activator of aspA.

FIG 9.

Relative fluorescence of strains with an aspA::gfp transcriptional fusion. All strains have a chromosomal transcriptional fusion controlled by either the wild-type aspA promoter (PAspA) or the aspA promoter with one mutation, which was identified in ACN2153 (PaspA52153 promoter allele indicated as “52153”). Differences in genetic backgrounds are indicated for each strain in the table. A checkmark indicates the wild-type allele for aalR, darR, or PaspA. Fluorescence is shown per OD595 relative to that of ACN1895 (average florescence normalized to OD595 = 10). Error bars represent the standard deviation from at least 6 biological replicates. All strains were grown on pyruvate with d-Asp added as an inducer.

A strain was constructed with the aspA::gfp fusion controlled by the mutated aspA promoter (PaspA52153) and with the darR coding sequence in place of aalR. This strain (ACN2222) was designed to resemble that in which this mutation was isolated (ACN2153). PaspA52153 increased GFP expression in the presence of d-Asp when darR was divergent from aspA or in its native position (ACN2222 and ACN2209 in Fig. 9). Transcription was not constitutive, but rather depended on DarR, as evidenced by low fluorescence when darR was deleted (ACN2278 in Fig. 9). The promoter mutation did not appear to affect AalR-mediated transcription, since strains with PaspA or PaspA52153 resulted in nearly identical fluorescence (ACN1984 and ACN2208 in Fig. 9). Thus, PaspA52153 specifically improves the ability of DarR to regulate aspA.

Transcriptional regulation of aspY.

We studied the AalR-DarR regulon further by evaluating expression of AspY, which appears to transport both d-Asp and l-Asp. Sequence alignment of the promoter regions of aspA (regulated by AalR) and racD (regulated by DarR) with aspY revealed similarities to the aspY regulatory region (Fig. 6C). Using the same approach as for aspA, we determined the transcriptional start site of aspY by 5′ RACE (13). The experimentally determined start site (+1) for aspY is shown as the right-most nucleotide in the top line of the alignment in Fig. 6C.

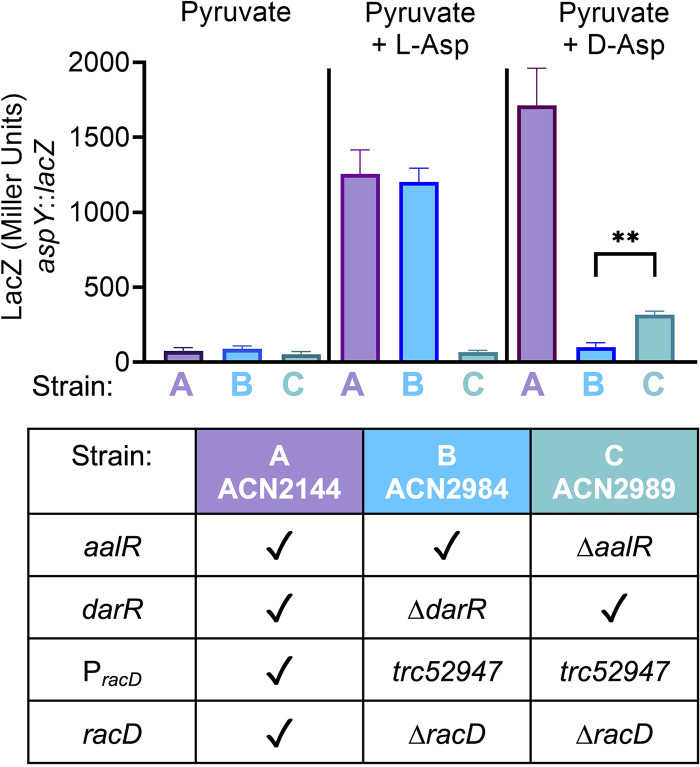

An aspY::lacZ fusion was integrated in the chromosome as a transcriptional reporter. When both regulators were present, transcription from PaspY increased in response to l-Asp or d-Asp, ACN2144 (strain A in Fig. 10). We made additional strains to assess the individual roles of DarR and AalR. In these mutants lacking darR (ACN2984) or aalR (ACN2989), we prevented isomerization of the enantiomers by deleting racD. To enable aspT transcription, the trc promoter (described earlier) was used to create PracD_trc52947. When aalR was intact, l-Asp but not d-Asp increased transcription (ACN2984, strain B). In contrast, when darR was intact, d-Asp, but not l-Asp, induced a small but statistically significant increase in LacZ expression from PaspY in ACN2989 (strain C in Fig. 10). These results indicate that both AalR and DarR can regulate aspY transcription and that each regulator responds only to one Asp enantiomer.

FIG 10.

LacZ expression from the aspY promoter. All strains have a chromosomal transcriptional fusion (17) controlled by the aspY promoter. Differences in genetic backgrounds are indicated. A checkmark signifies the wild-type allele for aalR, darR, PracD (the promoter controlling racD and aspT), and racD. ACN2984 (strain B) and ACN2989 (strain C) carry a racD deletion (ΔracD52953) to prevent the interconversion of d-Asp and l-Asp. In these strains, an engineered constitutive promoter (PracD_trc52947) allows aspT transcription regardless of the presence of DarR. All strains were grown on pyruvate. d-Asp or l-Asp was added as an inducer where noted. The significance in the unpaired t test of ACN2989 compared to ACN2984 grown on pyruvate plus d-Asp is indicated by ** (P < 0.0001).

l- and d-amino acids as carbon and nitrogen sources.

We compared the ability of A. baylyi to consume both enantiomers of Asp, Glu, and Asn. Of these six compounds tested, all but d-Glu served as the sole carbon or nitrogen source. On plates with each compound as the sole carbon source, individual colonies of ADP1 and various transport mutants were patched (l-Asp and d-Asp shown in Fig. 2 and all six plates shown in Fig. 11). While the overall patterns were similar for each strain on l-Asp, l-Asn, or l-Glu as the carbon source (Fig. 11A), loss of AspY (alone or in combination with AspT and/or AspS) had a greater impact on growth with l-Asn or l-Glu than with l-Asp. For example, the strain missing all three transporters (ApsY, AspT, and AspS) failed to grow on l-Glu or l-Asn, in contrast to slow growth on l-Asp (Fig. 2A and 11A, regions 8). Similarly, loss of AspY affected growth on d-Asn more than on d-Asp (Fig. 11B, regions 2). There appear to be functional overlaps for the uptake of these related amino acids with some subtle differences in the specificities and/or induction of the transporters.

FIG 11.

Growth of the wild type and transport mutants on l- and d-isomers of Asp, Glu, or Asn as the sole carbon source. Colonies were patched as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The images shown were taken after 4 days of incubation. The strains are ACN2035 (no AspT) in region 1, ACN2059 (no AspY) in region 2, ACN2964 (no AspS) in region 3, ADP1 (wild type) in region 4, ACN2061 (no AspT or AspY) in region 5, ACN2987 (no AspT or AspS) in region 6, ACN2988 (no AspY or AspS) in region 7, and ACN2967 (no AspT, AspY, or AspS) in region 8.

To assess the ability to use these amino acids as sole nitrogen sources, ADP1 and a mutant lacking AspA (ACN1894) were grown in medium with the indicated compound as the sole nitrogen source. Of the amino acids tested (both enantiomers of Asp, Asn, and Glu), only d-Glu failed to serve as a nitrogen source (Fig. S4). For this compound, culture densities were comparable to those attained when no nitrogen source was added. Although the loss of AspA in ACN1894 prevents the use of Asp and Asn as the sole carbon sources, AspA was not required for the use as a sole nitrogen source of l-Asp, d-Asp, l-Asn, d-Asn, or l-Glu. Possible routes for nitrogen assimilation for these amino acids that do not require AspA-mediated deamination are discussed below.

DISCUSSION

Two paralogs in ADP1, DarR and AalR, were found to regulate d- and l-Asp metabolism. These LTTRs control the transcription of aspA (encoding Asp ammonia lyase), racD (encoding Asp racemase), and aspT and aspY (encoding two Asp transporters). Although high expression of a third transporter (AspS) could compensate for the loss of AspT and AspY to enable growth on d-Asp as the carbon source, the aspS operator-promoter region shared no discernible similarity to comparable regions of genes in the DarR/AalR regulon (Fig. 6C). Additional studies are needed to clarify the transcriptional regulation of aspS.

AspT, AspY, and AspS belong to a family of Glu/Asp proton symporters that are common in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (9, 18). Mammalian homologs are studied intensively because of their roles in Glu-mediated neuronal signaling (18, 19). Moreover, the importance of d-Asp as a neurotransmitter draws attention to the specificity of Glu/Asp transporters and their ability to act on amino acid enantiomers. Structural studies of an archaeal homolog, GltTk from Thermococcus kodakarensis, describe features resulting in the uptake of d-Asp and l-Asp with similar affinities (20).

We are unaware of previous studies of the physiological relevance of transporter(s) for the bacterial consumption of d-Asp. As reported here, AspY and AspT enable ADP1 to use d-Asp as a sole carbon source. A transcriptional regulator, DarR, specifically responded to this compound to increase aspY and aspT transcription. The d-Asp transport function was corroborated by heterologous expression in E. coli, which acquired a d-Asp+ phenotype when AspY or AspT was expressed together with a racemase (RacD).

Overlapping functions of AspY, AspT, and AspS.

A complex evolutionary pattern for AspT homologs makes it difficult to rely solely on sequence analysis to infer function and specificity. The number of bacterial homologs varies. For example, while ADP1 encodes seven proteins in this family, E. coli encodes four, and A. fischeri, the bacterium in which aspT was first reported (VF_1546), encodes three. Because this diversity results in confusing database annotation, we used new designations of AspT, AspY, and AspS to reflect a role in Asp metabolism. Nevertheless, the primary role of AspS in ADP1 is unclear, as its loss had little effect on growth with d- or l-Asp as the carbon source (Fig. 2). Unlike AspT and AspY, expression of AspS with RacD failed to enable E. coli to grow on d-Asp as a carbon course. The heterologous host may not express and/or localize a functional AspS at sufficiently high levels.

Deleting aspY, aspT, and/or aspS impacted growth on l-Asp and d-Asp differently (Fig. 2 and 11). For example, the loss of AspT was more detrimental with d-Asp than l-Asp as the carbon source. This result, together with genetic context (Fig. 1), suggests a specific role for AspT in d-Asp uptake. Loss of AspT also prevented growth on d-Asn as the carbon source (Fig. 11). Since bioinformatic analysis did not reveal an Asn racemase, d-Asn may be converted to d-Asp by an asparaginase, some of which act on d-Asn (21, 22). If deamidation occurs in the periplasm, as it often does, further import would rely on Asp transporters, thereby accounting for similar growth patterns of each transport mutant with d-Asp or d-Asn as the carbon source. While genes for Asp and Asn catabolism are sometimes linked (22, 23), the asp genes on the ADP1 chromosome are distal to those encoding two putative asparaginases (UniProt IDs Q6FEV1 and Q6FAL6). One of these (Q6FAL6) is predicted to be exported to the periplasm, based on a lipoprotein signal peptide sequence detected with the SignalP-6.0 program (24).

Overall, similar growth patterns were observed with l-Asp, l-Asn, or l-Glu as the carbon source (Fig. 11). Comparable patterns on l-Asp and l-Asn media could be explained by periplasmic deamidation, as explained above for the corresponding d-enantiomers. Patterns on l-Asp and l-Glu media may reflect typical overlap in the specificity of Glu/Asp transporters (9). Nevertheless, some minor growth pattern differences were observed that require further investigation to explain.

d-Glu was not used as a sole carbon source, despite the presence of a d-Glu racemase (MurI) in ADP1. d-Glu may fail to be consumed due to factors such as regulation, the properties of MurI, and/or transport. Unlike A. baylyi, P. aeruginosa uses d-Glu but not d-Asp as a sole carbon or a sole nitrogen source.

Effector specificity of DarR and AalR.

AalR, like a comparable LTTR in P. aeruginosa, called AspR (11), responded to Asp. It appears that this amino acid itself serves as the effector rather than a downstream metabolite based on activation of an aspA::gfp reporter. In these experiments (Fig. 9), l-Asp cleavage is prevented by the aspA disruption. However, d-Asp and l-Asp can be interconverted by RacD, thereby precluding conclusions about which enantiomers allow AalR to increase transcription. In a different set of experiments, AalR-dependent transcriptional activation of aspY was observed in a racemase-deficient strain when l-Asp but not d-Asp was provided (ACN2984; strain B in Fig. 10). Similarly, although DarR can activate transcription from this promoter, it does so in response to d-Asp but not l-Asp (ACN2989; strain C in Fig. 10). Thus, DarR and AalR appear capable of distinguishing l-Asp from d-Asp.

Based on well-studied LTTRs, l-Asp and d-Asp may bind in a ligand recognition region of AalR and DarR, respectively (25). Structural studies of DarR from A. fischeri identified residues within the effector binding domain involved in ligand recognition (14). However, in this study the ligand-binding pocket was occupied by 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (MES), presumably an artifact of protein purification. Attempts to detect interactions between d-Asp and DarR were unsuccessful (14). Confirmation of Asp binding to DarR and AalR awaits further investigation, as does determination of the significance of sequence differences between l-Asp-responsive LTTRs (from A. baylyi and P. aeruginosa) and their d-Asp-responsive DarR homologs (from A. baylyi and A. fischeri) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

DNA binding and transcriptional control by DarR and AalR.

Within the DNA-binding domains of AalR and DarR at the N terminus of each protein, the recognition helix of a winged helix-turn-helix motif (wHTH) can be predicted based on the structure of DarR from A. fischeri (14). The high degree of sequence conservation in the DNA recognition regions of the aligned sequences (marked by a red box in Fig. S1) may reflect that they bind the same DNA sequence, ATGC-N7-GCAT. The spacing of a T-N11-A pattern within a short region of dyad symmetry matches the consensus binding site for LTTRs (26). This specific sequence is required for DarR binding to the operator region of PracD in A. fischeri (8).

Typically, LTTRs bind to DNA as homotetramers in the presence or absence of an effector molecule (25, 27). The binding of the effector may cause conformational changes that result in repositioning the regulator on the DNA and/or altering the bending angle of the DNA (28). In the case of DarR, a tetramer (14), the dyad symmetry of the recognition sequence (ATGC-N7-GCAT) should allow interactions with the wHTH motif of two subunits. The recognition helix of each would be positioned in the major DNA groove to interact with half of the recognition sequence (ATGC), on the top or bottom strand of DNA. When DarR is in the active conformation, presumably bound to d-Asp, the wHTH of one of the other two subunits could interact with the reverse complement of a sequence (GCAT) overlapping the −35 region of the promoter (boxed in Fig. 6C). This promoter-proximal position is comparable to that used to bind subunits of other well-studied LTTRs of ADP1, BenM and CatM (29). However, for these regulators, the promoter-proximal binding site (sometimes called the activation site) has near-perfect dyad symmetry resembling the recognition sequence. Such symmetry is absent in this site for racD of ADP1 (TTTT-N7-GCAT).

Alignment of the racD operator-promoter region with those of aspA and aspY suggests that the promoter-proximal “half-site” sequence (GCAT) is significant, as it is conserved in all three regulatory regions of ADP1 controlled by AalR and/or DarR (Fig. 6C). This pattern, which could account for three of the four subunits of a tetramer binding to the same sequence (ATGC), has not previously been noted. However, structural studies of CbnR provide an example in which two subunits of a tetramer bind to an activation site with no dyad symmetry and no obvious resemblance to its recognition sequence (T-N11-A within short inverted repeats) (28). Our EMSA data demonstrated that AalR binds specifically to the aspA operator-promoter region, but precise localization cannot be determined from this method. As described for BenM and CatM, LTTR binding of DarR or AalR at the proposed positions could enable transcriptional activation by direct contact with the σ70 subunit of RNA polymerase holoenzyme and/or the C-terminal domains of the α subunit (29). However, the LTTR regulatory model based on studies of BenM and CatM did not exactly match the features of a canonical class I or a class II promoter (29, 30).

Similarity in AalR/DarR-regulated operator-promoter regions (Fig. 6C) raised the possibility that DarR could substitute for AalR to activate aspA transcription. However, AalR-independent growth on d- or l-Asp as the carbon source required additional mutations. DarR substitution resulted from a single-nucleotide change in the −10 region of the aspA promoter (PaspA52153 in Fig. 6 and 9). In other mutants, DarR activated aspA transcription when ClpAP-mediated proteolysis was prevented. Without ClpA, an increase in the concentration or stability of DarR, or other protein(s), may occur to enable DarR to substitute for AalR. These subtle distinctions in the roles of AalR and DarR presumably reflect the importance of fine-tuned regulation in nature and suggest that d-Asp is a significant carbon and/or nitrogen source.

Nitrogen metabolism in A. baylyi ADP1.

l- and d-Asp can each serve as a sole carbon or nitrogen source (Fig. S4). In ADP1, ammonia is produced by AspA-mediated cleavage (Fig. 1), and its assimilation is expected to proceed by incorporation into Glu via glutamate dehydrogenase (UniProt ID Q6FD67) or Gln via glutamine synthetase (GS) (UniProt ID Q6F9N5). The latter enzyme, in conjunction with glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) (UniProt IDs Q6F7E7 and Q6F7E8) is often the primary pathway for ammonia assimilation in bacteria (31).

While nitrogen assimilation from Asp by E. coli depends on AspA (32), an A. baylyi aspA mutant could use l- or d-Asp as the sole nitrogen source (ACN1894 in Fig. S4). In contrast, ACN1894 did not use l- or d-Asp as the sole carbon source. This distinction might account for cultures of ADP1 reaching higher cell densities than those of ACN1894 when l- or d-Asp was provided as the nitrogen source (significance assessed by t tests, P < 0.0001 for l-Asp and P = 0.0007 for d-Asp). For the wild-type strain (but not ACN1894), AspA-mediated cleavage would produce both ammonia and fumarate, and the latter compound could serve as an additional source of carbon (Fig. 1; Fig. S4). For the aspA mutant, an alternative pathway must be used for nitrogen assimilation. In this case, an aminotransferase, AspC (UniProt ID Q6F9C7), may convert l-Asp and 2-oxoglutarate to l-Glu and oxaloacetate (33). Similarly, ACN1894 must use a route for nitrogen assimilation that does not involve AspA when it grows with l-Asn, d-Asn, or l-Glu as the nitrogen source.

A. baylyi ADP1 and other bacteria, such as E. coli, A. fischeri, and P. aeruginosa, have distinctive metabolic characteristics related to d- and l-Asp consumption. Because chiral amino acids are important in agricultural, food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, amino acid metabolic pathways have potential applications in biotechnology (34). Our studies of the transport, regulation, and catabolism of d-Asp highlight both the catabolic versatility and genetic malleability of ADP1. The ability to use this bacterium for simple genetic studies allowed many of our experiments to be conducted in an undergraduate teaching laboratory. Furthermore, the ease of chromosomal manipulation contributes to the increasing choice of ADP1 for metabolic engineering applications and synthetic biology (6, 35).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media, growth conditions, and methods for comparative growth of different strains.

Cultures were grown in a minimal medium (MM) with (NH4)2SO4 as the nitrogen source, as described previously (36). Unless otherwise noted, a 20 mM carbon source was provided: pyruvate, l-Asp, d-Asp, l-Asn, d-Asn, l-Glu, or d-Glu. Cultures were incubated at 37°C, and liquid cultures were aerated by shaking at 250 rpm. Antibiotics were used at final concentrations of 25 μg/mL for kanamycin (Km), 12.5 μg/mL each for streptomycin (Sm) and spectinomycin (Sp), and 150 μg/mL for ampicillin (Ap). In some experiments, including those for plasmid construction, bacteria were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB), also known as Luria-Bertani medium (10 g of Bacto-tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl per L) (37).

For heterologous expression of ADP1 proteins, cultures of E. coli DH5α carrying plasmids (Table 1; see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were grown on MM with Km and 20 mM l-Asp or d-Asp as the carbon source. Cell density (optical density [OD]) was measured spectrophotometrically at 595 nm 72 h after inoculation. Six independent replicates were evaluated.

To compare levels of A. baylyi growth on media with different carbon sources (as shown in Fig. 2 and 11 and Fig. S3), strains were streaked or plated on nonselective medium to obtain uniform, well-isolated colonies. Cells from one colony were then transferred with a toothpick to the same position on plates with different carbon sources. Multiple colonies from the same strain were tested. Plates were incubated and photographed. To test nitrogen sources, MM was used without (NH4)2SO4. Starting cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in MM with 20 mM pyruvate and 7.6 mM (NH4)2SO4 as the carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. The next day, 20-μL samples of these cultures were used to inoculate 5 mL of MM with 20 l-Asp, d-Asp, l-Asn, d-Asn, l-Glu, or d-Glu as the nitrogen source and pyruvate as the carbon source. As controls, the nitrogen-free MM was supplemented with (NH4)2SO4 or no nitrogen source. After incubation for 24 h with aeration at 37°C, OD595 readings were recorded (Fig. S4).

Strains and plasmids.

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. Additional details are provided in Tables S1 to S3. A. baylyi strains with ACN designations were derived from the wild type, ADP1 (7, 38). E. coli strains XL1-Blue (Agilent Technologies) and DH5α (39) were used as plasmid hosts. Plasmids are listed in Table 1 and Table S2. Several vectors were used for cloning: pUC18 or pUC19 (40), pminiT2.0 (New England Biolabs), and pJPK13 (41). Omega drug resistance cassettes were obtained from pUI1637 (ΩK, which confers Kmr) or pUI1638 (ΩS, which confers resistance to Smr and Spr) (42). The sources of transcriptional reporter genes were pKOK6 (for lacZ) (17) and pJLS27 (for gfp) (43). A selectable/counterselectable cassette (sacB-Kmr) was obtained from pRMJ1 (44).

Methods for strain and plasmid construction involved standard molecular biology procedures (37) and techniques developed for ADP1 (6). DNA was PCR amplified with the high-fidelity polymerases PrimeSTAR Max (TaKaRa Biosciences) and Phusion (New England Biolabs), with primers shown in Table S3. Plasmids were constructed by overlapping sequence assembly (45), by restriction digest and ligation (Quick Ligation kit; New England Biolabs), with the NEBuilder kit (New England Biolabs), and/or by overlap extension PCR (46). Plasmids were confirmed by restriction mapping and/or regional DNA sequencing (Eton Biosciences).

A. baylyi chromosomal changes were made by allelic replacement using linear DNA to transform naturally competent recipients (6, 47, 48). To prepare donor DNA, plasmids were linearized by digestion with restriction enzymes. When genomic DNA was used, DNA was usually prepared as a crude cell lysate. Pelleted cells were suspended in 0.5 mL of sterile lysis buffer (0.05% sodium dodecyl-sulfate [SDS], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M citrate, trisodium salt) and incubated in a 65°C water bath for 1 h. The lysate was diluted (10 to 100×), and any remaining cells were removed by filtration. For PCR products, template DNA was degraded by DpnI (New England Biolabs). Genotypes were confirmed by PCR with LongAmp polymerase (New England Biolabs) and/or regional DNA sequencing (Eton Biosciences).

Isolation and characterization of spontaneous Asp+ mutants.

Six spontaneous mutants were isolated in these studies (ACN2153, ACN2917, ACN2921, ACN2926, ACN2927, and ACN2928) (Table 1; Table S1). Each was selected as an Asp+ colony on a plate and streak purified three times on selective medium. Genotypes were evaluated by localized DNA sequencing, whole-genome sequencing, and/or by A. baylyi transformation assays. ACN2921 arose from a targeted search for mutants. The parent strain (ACN2061) was grown in multiple 5-mL cultures, each in MM with a single carbon source (20 mM): l-Asp, l-Glu, adipate, succinate, or pyruvate. After overnight growth, samples (100 μL) were used in dilution series, plated to nonselective pyruvate medium, to determine CFU per milliliter in initial cultures. Cultures were pelleted (in a microcentrifuge at 5,000 × g for 3 min) and concentrated by suspension in 100 μL MM. All cells were spread on a single MM plate with d-Asp as the carbon source. Mutation frequency was calculated as the number of d-Asp+ mutants arising from the total CFU that were plated.

A. baylyi transformation assays.

Transformation methods for naturally competent A. baylyi have been described (6, 12, 47). For assays such as those shown in Fig. 3 and 8, the recipient strain was grown overnight in 5 mL of MM with pyruvate. The next day, 20 mM pyruvate (100 μL) was added, and cells were incubated with aeration for an additional 30 min. A sample of the culture (100 μL) was plated on selective medium that did not support growth of the recipient. Linear DNA (100 μg) was dropped in marked spots on top of the cells. After incubation, growth was observed in spots where the donor DNA replaced the homologous chromosomal regions. When PCR products were used as donor DNA, digestion by DpnI (New England Biolabs) was used to degrade the template. Methods for preparing genomic DNA as the donor removed whole cells.

Transcriptional fusions (measurements of LacZ and GFP).

For β-galactosidase (LacZ) assays, cells from overnight cultures were diluted (1:10 to 1:40) with Z-buffer (16 g Na2HPO4·7H2O, 5.5 g NaH2PO4·H2O, 0.8 g KCl, and 0.3 g MgSO4·7H2O in 1 L H2O with 27 μL β-mercaptoethanol added fresh to 10 mL Z-buffer). Chloroform and 0.001% SDS (final concentration) were added. The reaction, at 37°C, was started by adding, to 1 mL of cell mixture, 250 μL o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) (4 mg/mL ONPG in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.0]). After color formation, 500 μL stop buffer (106 g Na2CO3 in 1 L H2O) was added. Cells were pelleted at 5,000 × g for 3 min, and the supernatant fluid was measured at 420 nm. Each culture was also diluted 1:5 in Z-buffer and measured spectrophotometrically at 650 nm. Miller units were calculated as (1,000 × A420)/(t × v × A650). At least 4 replicates were assayed for each strain.

Green fluorescence (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 528 nm) from GFP expressed under transcriptional control from the aspA promoter was measured (Fig. 9). Cultures grown on MM with pyruvate as the carbon source were diluted (1:10) in the same medium with and without exogenous inducers (5 mM l-Asp or d-Asp). Cultures were assayed at an OD600 of 0.86 to 1.2. Measurements were determined as green fluorescence relative to OD600, using a Synergy 2 plate reader (Biotek). Values were reported relative to an A. baylyi strain without gfp.

Transcript analysis.

For RNA isolation, ADP1 cells were harvested at an OD600 of approximately 0.7. RNA was preserved using RNAprotect (Qiagen) and isolated using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA was further treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and confirmed to be free of DNA using PCR with appropriate primers and controls. The transcript initiation sites for aspA, aspY, and aalR were determined (with the 5′ RACE kit, Invitrogen) after making cDNA using gene-specific primers: oALS60, oLES9, and oALS114, respectively (Table S3). For aspA, cells were grown with l-Asp as the carbon source. Two aspA-specific PCR primers (oALS61 and oALS62) were used to pair with two kit-provided primers that bind to the region of homopolymeric C-tailing corresponding to the transcriptional start site. For aspY, cells were grown with d-Asp as the carbon source. In this case, the kit-provided primers were used to generate PCR products in reactions with aspY-specific primers oLES10 and oLES11. Multiple PCR products were cloned (into pCR4-TOPO vector; Invitrogen) and sequenced from at least two independently isolated RNA samples. The transcriptional start sites were determined as shown in Fig. 6A and C.

For aalR, several attempts failed to provide sufficient cDNA for characterization. Since LTTR genes are often transcribed at low levels, we used a previously described method to generate multiple copies of a chromosomal region in a tandem array (15, 49). The resulting strain, ACN2029, was grown on l-Asp. In this case, primers oALS66 and oALS115 were used in combination with the kit-provided primers to generate PCR products in reactions using three independently isolated RNA samples. After cloning and sequencing multiple fragments, the aalR transcriptional start site was localized to a region rather than a precise nucleotide.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay with AalR-His6.

C-terminal hexahistidine-tagged protein (AlaR-His6) was expressed from plasmid pBAC1057 in E. coli BL21(DE3) RIPL (Agilent Technologies). The tagged protein was purified by the method used for MdcR-His5 (15), with the following modification: the dialysis buffer contained 20 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl, 10 % glycerol, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (pH 8.1).

The binding of purified AalR-His6 to DNA was assessed as described for MdcR-His5 in reference 15, with the following modifications. (i) Purified AalR-His6 was diluted in a mixture of 20 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl, 10 % glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (pH 8.1), and 10 mg bovine serum albumin (BSA) mL−1. (ii) Labeled DNA probes were generated from ADP1 genomic DNA by PCR with primer pairs 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-oALS68 and oALS67 and 6-FAM-oALS65 and oALS66. (iii) Binding reaction mixtures contained the indicated concentration of AalR, 50 mM NaCl, 2% glycerol, 2 mg BSA mL−1, 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8), 1 mM potassium acetate, 2.5 mM ammonium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM CaCl, 50 ng poly(dI-dC) mL−1 or 10 ng sonicated herring sperm DNA mL−1, 1 mM l-Asp, and 2 nM labeled DNA probe. For the competition assays, unlabeled specific competitor DNA (PCR generated with primers oALS65 and oALS66) and nonspecific competitor DNA (sonicated herring sperm DNA) were added to binding reaction mixtures at the indicated molar ratios relative to the 2 nM labeled DNA probe. Electrophoresis of binding reactions (with 1 mM l-Asp in the running buffer), gel imaging, and analysis were performed as described in reference 15.

DNA sequencing, analysis, and sequence alignments.

Localized DNA sequencing was conducted using Eton Biosciences. For whole-genome resequencing, genomic DNA was isolated and sonicated to approximately 500-bp fragments in a total of 500 ng. Genomic libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA library prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs), including end repair, adaptor ligation, and addition of an individual i5/i7 index primer. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NextSeq500 instrument at the Georgia Genomics and Bioinformatic Core at the University of Georgia. Sequence analysis was performed using Geneious software with default settings (50). A reference genome was constructed by mapping reads from ADP1 to GenBank accession no. CR543861. Paired-end reads were mapped to this refence genome, and a minimum variant frequency of 0.8 was used to call variants and identify single nucleotide polymorphisms.

To determine paralogs of AspT, we used the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (51) and the sequence similarity database (SSDB) with associated search tools of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (52). Protein sequences were aligned and data exported using programs on the UniProt website (53). Figures displaying protein sequence alignments (Fig. S1 and S2) were generated using a Sequence Manipulation Suite program, Multiple Align Show (54). DNA sequences were aligned and displayed (Fig. 6) using the MultAlin program (55).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Students from multiple semesters of a University of Georgia experimental Microbiology Lab course contributed to this research (Ayah Abdelwahab, Sina Ayati, Walker Boyd, John Chaknis, Arnav Cherian, Nicholas Ciappa, Ana Cvijetinovic, Tina Dimnwaobi, Melissa Downey, Julia Evans, Kenleanne Hass, Jessica Ho, Jessica Ijeoma, Luan Huynh, Dahyun Ji, Yoon Ji, Yoonjee Kim, Brendan Mahoney, Felder Martin, Nida Moledina, Silas Money, Miles Morgan, Whitney Okenwa, Chiagoziem Onyegbule, Prital Patel, Alexandria Purcell, Nolan Ross-Kemppinen, Yosselin Ochoa, Rahil Patel, Jenny Son, R. Caroline Smith, Teresa Tran, Blaine Walsh, David White, and Abigail Wilson). These students helped at various steps to construct plasmids and strains, to select/screen for mutants, to measure growth and/or lacZ activity for mutant/reporter strains, to map transcriptional start sites, and to perform EMSAs. Nicole Laniohan and Jennifer Tsang contributed as teaching assistants for the course. We thank Cory Momany for help with purifying the regulatory protein for EMSA studies. Caroline M. Dunn also contributed to this work as a summer undergraduate student in an NSF-funded REU program.

This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grants DEB-1556541, MCB-1615365, and DBI-1460671 (the REU Site program). This project was also supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Science Program under Award no. DE-SC0022220. Additional funding was provided by the UGA Microbiology Department.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Ellen L. Neidle, Email: eneidle@uga.edu.

Gladys Alexandre, University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ota N, Shi T, Sweedler JV. 2012. d-Aspartate acts as a signaling molecule in nervous and neuroendocrine systems. Amino Acids 43:1873–1886. 10.1007/s00726-012-1364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastings J, van Eijk HM, Olde Damink SW, Rensen SS. 2019. d-Amino acids in health and disease: a focus on cancer. Nutrients 11:2205. 10.3390/nu11092205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cava F, Lam H, De Pedro MA, Waldor MK. 2011. Emerging knowledge of regulatory roles of d-amino acids in bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:817–831. 10.1007/s00018-010-0571-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi J. 2019. d-Amino acids and lactic acid bacteria. Microorganisms 7:690. 10.3390/microorganisms7120690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang R, Zhang Z, Sun J, Jiao N. 2020. Differences in bioavailability of canonical and non-canonical d-amino acids for marine microbes. Sci Total Environ 733:139216. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggs BW, Bedore SR, Arvay E, Huang S, Subramanian H, McIntyre EA, Duscent-Maitland CV, Neidle EL, Tyo KEJ. 2020. Development of a genetic toolset for the highly engineerable and metabolically versatile Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Nucleic Acids Res 48:5169–5182. 10.1093/nar/gkaa167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaneechoutte M, Young DM, Ornston LN, De Baere T, Nemec A, Van Der Reijden T, Carr E, Tjernberg I, Dijkshoorn L. 2006. Naturally transformable Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 belongs to the newly described species Acinetobacter baylyi. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:932–6. 10.1093/nar/gkaa167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RM, Jr, Popham DL, Schmidt AL, Neidle EL, Stabb EV. 2018. Vibrio fischeri DarR directs responses to d-aspartate and represents a group of similar LysR-type transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol 200:e00773-17. 10.1128/JB.00773-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman M, Ismat F, Jiao L, Baldwin JM, Sharples DJ, Baldwin SA, Patching SG. 2017. Characterisation of the DAACS family Escherichia coli glutamate/aspartate-proton symporter GltP using computational, chemical, biochemical and biophysical methods. J Membr Biol 250:145–162. 10.1007/s00232-016-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craven SH, Ezezika OC, Momany C, Neidle EL. 2008. LysR homologs in Acinetobacter: insights into a diverse and prevalent family of transcriptional regulators. In Gerischer U (ed), Acinetobacter molecular biology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, Lu C-D. 2018. Molecular characterization and regulation of operons for asparagine and aspartate uptake and utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology (Reading) 164:205–216. 10.1099/mic.0.000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neidle EL, Ornston LN. 1986. Cloning and expression of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus catechol 1,2-dioxygenase structural gene catA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 168:815–820. 10.1128/jb.168.2.815-820.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frohman MA, Dush MK, Martin GR. 1988. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:8998–9002. 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, Wu H, Xiao Q, Zhou H, Li M, Xu Q, Wang Q, Yu F, He J. 2021. Crystal structure details of Vibrio fischeri DarR and mutant DarR-M202I from LTTR family reveals their activation mechanism. Int J Biol Macromol 183:2354–2363. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoudenmire JL, Schmidt AL, Tumen-Velasquez MP, Elliott KT, Laniohan NS, Walker Whitley S, Galloway NR, Nune M, West M, Momany C, Neidle EL, Karls AC. 2017. Malonate degradation in Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1: operon organization and regulation by MdcR. Microbiology (Reading) 163:789–803. 10.1099/mic.0.000462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins JR, Pak M, Maurizi MR, Wickner S. 1998. The role of the ClpA chaperone in proteolysis by ClpAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:12135–12140. 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokotek W, Lotz W. 1989. Construction of a lacZ-kanamycin-resistance cassette, useful for site-directed mutagenesis and as a promoter probe. Gene 84:467–471. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grewer C, Gameiro A, Rauen T. 2014. SLC1 glutamate transporters. Pflugers Arch 466:3–24. 10.1007/s00424-013-1397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji Y, Postis VL, Wang Y, Bartlam M, Goldman A. 2016. Transport mechanism of a glutamate transporter homologue GltPh. Biochem Soc Trans 44:898–904. 10.1042/BST20160055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arkhipova V, Trinco G, Ettema TW, Jensen S, Slotboom DJ, Guskov A. 2019. Binding and transport of d-aspartate by the glutamate transporter homolog GltTk. eLife 8:e45286. 10.7554/eLife.45286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell HA, Mashburn LT. 1969. l-Asparaginase EC-2 from Escherichia coli. Some substrate specificity characteristics. Biochemistry 8:3768–3775. 10.1021/bi00837a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuo S, Zhang T, Jiang B, Mu W. 2015. Recent research progress on microbial l-asparaginases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:1069–1079. 10.1007/s00253-014-6271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun D, Setlow P. 1991. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Bacillus subtilis ans operon, which codes for l-asparaginase and l-aspartase. J Bacteriol 173:3831–3845. 10.1128/jb.173.12.3831-3845.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teufel F, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Johansen AR, Gislason MH, Pihl SI, Tsirigos KD, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2022. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Chhor G, Tsai CS, Winans JB, Jedrzejczak R, Joachimiak A, Winans SC. 2018. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding domain of a LysR-type transcriptional regulator: transcriptional activation via a rotary switch. Mol Microbiol 110:550–561. 10.1111/mmi.14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alanazi AM, Neidle EL, Momany C. 2013. The DNA-binding domain of BenM reveals the structural basis for the recognition of a T-N11-A sequence motif by LysR-type transcriptional regulators. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:1995–2007. 10.1107/S0907444913017320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerche M, Dian C, Round A, Lonneborg R, Brzezinski P, Leonard GA. 2016. The solution configurations of inactive and activated DntR have implications for the sliding dimer mechanism of LysR transcription factors. Sci Rep 6:19988. 10.1038/srep19988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannopoulou EA, Senda M, Koentjoro MP, Adachi N, Ogawa N, Senda T. 2021. Crystal structure of the full-length LysR-type transcription regulator CbnR in complex with promoter DNA. FEBS J 288:4560–4575. 10.1111/febs.15764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tumen-Velasquez MP, Laniohan NS, Momany C, Neidle EL. 2019. Engineering CatM, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, to respond synergistically to two effectors. Genes 10:421. 10.3390/genes10060421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browning DF, Busby SJ. 2004. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:57–65. 10.1038/nrmicro787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reitzer L. 2003. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:155–176. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schubert C, Zedler S, Strecker A, Unden G. 2021. l‐Aspartate as a high‐quality nitrogen source in Escherichia coli: regulation of l‐aspartase by the nitrogen regulatory system and interaction of l‐aspartase with GlnB. Mol Microbiol 115:526–538. 10.1111/mmi.14620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu F, Hao J, Yan H, Bach T, Fan L. 2014. AspC-mediated aspartate metabolism coordinates the Escherichia coli cell cycle. PLoS One 9:e92229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue YP, Cao CH, Zheng YG. 2018. Enzymatic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amino acids. Chem Soc Rev 47:1516–1561. 10.1039/c7cs00253j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santala S, Santala V. 2021. Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1-naturally competent for synthetic biology. Essays Biochem 65:309–318. 10.1042/EBC20200136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh A, Bedore SR, Sharma NK, Lee SA, Eiteman MA, Neidle EL. 2019. Removal of aromatic inhibitors produced from lignocellulosic hydrolysates by Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 with formation of ethanol by Kluyveromyces marxianus. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:91. 10.1186/s13068-019-1434-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juni E, Janik A. 1969. Transformation of Acinetobacter calco-aceticus (Bacterium anitratum). J Bacteriol 98:281–288. 10.1128/jb.98.1.281-288.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:4645–4649. 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. 1983. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene 26:101–106. 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson J, Phillips GJ. 2008. New pSC101-derivative cloning vectors with elevated copy numbers. Plasmid 59:193–201. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eraso JM, Kaplan S. 1994. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 176:32–43. 10.1128/jb.176.1.32-43.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colton DM, Stoudenmire JL, Stabb EV. 2015. Growth on glucose decreases cAMP‐CRP activity while paradoxically increasing intracellular cAMP in the light‐organ symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 97:1114–1127. 10.1111/mmi.13087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones RM, Williams PA. 2003. Mutational analysis of the critical bases involved in activation of the AreR-regulated σ54-dependent promoter in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5627–5635. 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5627-5635.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kostylev M, Otwell AE, Richardson RE, Suzuki Y. 2015. Cloning should be simple: Escherichia coli DH5α-mediated assembly of multiple DNA fragments with short end homologies. PLoS One 10:e0137466. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horton RM, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Hunt HD, Cai Z, Pease LR. 1993. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol 217:270–279. 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seaton SC, Elliott KT, Cuff LE, Laniohan NS, Patel PR, Neidle EL. 2012. Genome-wide selection for increased copy number in Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1: locus and context-dependent variation in gene amplification. Mol Microbiol 83:520–535. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neidle E, Hartnett C, Ornston L. 1989. Characterization of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus catM, a repressor gene homologous in sequence to transcriptional activator genes. J Bacteriol 171:5410–5421. 10.1128/jb.171.10.5410-5421.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]