Abstract

Escherichia coli responds to external acidification (pH 4.0 to 5.0) by synthesizing a newly identified, ∼450-nucleotide RNA component. At maximal levels of induction it is one of the most abundant small RNAs in the cell and is relatively stable bacterial RNA. The acid-inducible RNA was purified, and the gene encoding it, designated asr (for acid shock RNA), mapped at 35.98 min on the E. coli chromosome. Analysis of the asr DNA sequence revealed an open reading frame coding for a 111-amino-acid polypeptide with a deduced molecular mass of approximately 11.6 kDa. According to computer-assisted analysis, the predicted polypeptide contains a typical signal sequence of 30 amino acids and might represent either a periplasmic or an outer membrane protein. The asr gene cloned downstream from a T7 promoter was translated in vivo after transcription using a T7 RNA polymerase transcription system. Expression of a plasmid-encoded asr::lacZ fusion under a native asr promoter was reduced ∼15-fold in a complex medium, such as Luria-Bertani medium, versus the minimal medium. Transcription of the chromosomal asr was abolished in the presence of a phoB-phoR (a two-component regulatory system, controlling the pho regulon inducible by phosphate starvation) deletion mutant. Acid-mediated induction of the asr gene in the Δ(phoB-phoR) mutant strain was restored by introduction of the plasmid with cloned phoB-phoR genes. Primer extension analysis of the asr transcript revealed a region similar to the Pho box (the consensus sequence found in promoters transcriptionally activated by the PhoB protein) upstream from the determined transcription start. The asr promoter DNA region was demonstrated to bind PhoB protein in vitro. We discuss our results in terms of how bacteria might employ the phoB-phoR regulatory system to sense an external acidity and regulate transcription of the asr gene.

The ability to sense and respond to changing environmental conditions by turning on genetic regulatory systems has been recognized as an essential feature that enables many enteric bacteria to survive and successfully adapt to numerous stressful treatments (heat, osmolarity, starvation, radiation, anaerobiosis, etc.). Products of genes comprising these networks are involved in a broad range of cellular events, from receiving the initial signal to repairing the damages caused by stress (57).

In a variety of environments, low pH is a common condition with which many enteric bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Helicobacter pylori, must cope. Enterobacteria respond to low pH by de novo synthesis of specific sets of proteins (23, 24) and the altered expression level of a number of genes, as has been demonstrated by gene-operon fusions (15, 22). Observations of the last few years have established that bacteria possess specific molecular mechanisms to respond and adapt to acid stress (for reviews, see references 5, 12, 45). The well known and investigated molecular systems responding to an environmental acidity are inducible amino acid decarboxylases. Their contribution to pH homeostasis (alkalinization of the cytoplasm by elimination of H+ ions), when bacteria encounter acidity, has been demonstrated by the analysis of E. coli and S. typhimurium cadBA operons (encoding lysine decarboxylase CadA and lysine/cadaverine antiporter CadB); the E. coli gene for arginine decarboxylase, adiA; and its regulator, adiY (39, 46, 55, 56). A similar role has been proposed for an E. coli glutamate decarboxylase and a putative glutamate/γ-amino butyrate antiporter (21). Whereas bacterial acid-inducible decarboxylases play an important role in pH homeostasis, survival and adaptation to extreme pH values, when constitutive pH homeostasis normally fails, require additional genetic systems. E. coli and S. typhimurium are able to tolerate severe acidity after exposure to a mild acid (14, 19). This complex acid tolerance response phenomenon in S. typhimurium has been intensively studied and shown to require the synthesis of over 50 acid shock proteins and to be growth phase regulated (4).

The expression of most low-pH-inducible genes identified so far in bacteria is also affected by other environmental signals (anaerobiosis, presence of nutrients, starvation, and specific host-produced factors), implying the intersection of different regulatory pathways and overlapping control of gene expression (12, 45). Here we report on the newly identified E. coli gene (asr) inducible by a low external pH. Acid-induced expression of asr is strongly reduced in complex Luria-Bertani (LB) medium compared to expression in minimal medium. Our experiments suggest that pH-triggered expression of asr may be regulated by the bacterial two-component regulatory system phoB-phoR, which controls the E. coli pho regulon inducible by phosphate starvation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli cells were grown in LB medium (40). For in vivo labeling with 32P and induction of RNA under acidic conditions, a low-phosphate-glucose-salts medium (LPM), supplemented with peptone (0.6 mg/ml), was used (28). LPM was buffered with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.0) or MES (morpholineethane sulfonic acid) (pH 5.0) to a final concentration of 0.1 M. For phosphate starvation analysis, MOPS minimal growth medium (MM), supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 0.01 M thiamine hydrochloride, and appropriate amino acids (20 μg/ml), was used (42). Phosphate was added to the MM as K2HPO4 to a final concentration of 0.01 mM (low Pi) or 1 mM (high Pi). To analyze the medium and phosphate starvation effect, cells were grown in the specified medium until the density of cultures reached approximately 108 cells ml−1. At this point, the pH of the growth medium was shifted down to 4.8, whereas that of the control cultures remained unchanged. After incubation for an additional 1 h, cells were assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or phage | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| ANCK10 | F−leu lacY trp his argG strA ilv metA (or metB) thi | 37 |

| ANCH1 | ANCK10 with Δ(phoB-phoR) Kanr | 69 |

| D10 | RNase− (rna) met relA | 28 |

| HB101 | F−hsdS20(rB− mB−) leu supE44 ara14 galK2 lacY1 proA2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 mcrB | 6 |

| JE13 | N2212 asr::Kan | This work |

| M8820 | F−araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 Δ(proAB-argF-lacIPOZYA)XIII rpsL | 9 |

| M8820Mu | M8820 with Mu cts | 8 |

| cts | ||

| MAL103 | F− Mu dI1 ara::(Mu cts)3Δ(proAB-argF-lacIPOZYA)XIII rpsL | 9 |

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)205 flbB5301 ptsF25 relA1 rpsL150 deoC1 | 8 |

| N 2212 | D10 ssrA::Cm | 44 |

| POI1734 | MAL103 with Mu dI1734 (Kanr) in place of Mu dI1734 (Apr) | 9 |

| Phagea | ||

| λ 311/E3F2 | asr+; position 35.98 minb | 29 |

| λ 311::Kan | pAS4 recombined on λ 311 | This work |

| Plasmid | ||

| pUC18/19 | Cloning vectors | 71 |

| pUC4K | Vector carrying Kanr fragment | Pharmacia |

| pBR322 | Cloning vector | 6 |

| pT7-6 | Expression vector | 59 |

| pBC6ΔPstI | phoBR operon in pUC18 | 65 |

| pGP1-4 | Vector with T7 RNA polymerase gene | 59 |

| pAS1 | 2.13-kb BglI fragment from λ 311 cloned into pUC19 | This work |

| pAS2 | 1.3-kb BglI-PvuII fragment from λ 311 cloned into pUC19 | This work |

| pAS3 | pAS1 without PstI restriction site in MCS | This work |

| pAS4 | 1.3-kb kanamycin resistance gene from pUC4K cloned into PstI site of pAS3 | This work |

| pAS5 | 706-bp Csp6I fragment from pAS2 cloned into SmaI site of pT7-6 | This work |

| pAS6 | 1.3-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment from pAS2 cloned into pBR322 | This work |

| pAS7 | 286-bp HindIII-Bsp143II fragment from pAS5 cloned into pT7-6 | This work |

| pAS8 | pAS6 containing Mu dI1734(Kanrlac) at position 127 in the asr DNA | This work |

| pVG6 | 2.0-kb MluI fragment with phoB gene from pBC6ΔPstI cloned into SmaI site of pT7-6 | This work |

| pVG11 | 2.0-kb MluI fragment with phoB gene from pBC6ΔPstI cloned into SmaI site of pUC19 | This work |

| pVG12 | 2.8-kb BpiI-EcoRI fragment with phoR gene from pBC6ΔPstI cloned into pUC18 | This work |

For solid media, the pH was adjusted prior to addition of agar (1.5%) and autoclaving. When necessary, the following antibiotics were added at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 34 μg/ml; tetracycline, 20 μg/ml; and kanamycin 60 μg/ml.

Growth and 32P labeling of cells.

Cells were cultured overnight in LB medium at 30°C and inoculated the next morning into the LPM (usually 1 ml of the medium). When the cultures had reached an A560 of 0.5 to 0.7, the pH was shifted to pH 4.8 to 5.0 by adding several drops of sterile 0.55 N HCl. After 30 min of incubation at 30°C, 50 μCi of H3PO4 (carrier free; ICN Radiochemicals)/ml added and incubation was continued. At appropriate times after labeling (30 to 120 min), samples were quickly poured into microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at room temperature for 20 s at 4,000 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM Na2EDTA, 20% glycerol, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 4 mM diethyl pyrocarbonate, and 0.01% bromophenol blue) and boiled for 4 min to achieve complete lysis. Cell lysates were subjected to electrophoresis in a 5%–8% tandem polyacrylamide gel (PAG) (1 mm thick) containing 7 M urea as described previously (18). The gels were dried and autoradiographed overnight on X-ray film (Hyperfilm; Amersham) at −70°C.

Isolation and purification of acid-induced RNA molecules.

For the preparation of purified acid-induced RNA, cultures were grown and labeled in a manner similar to that described above, except that 1 mCi of H332PO4 per ml of culture was added after the acid shift, and cells were incubated for an additional 2 h. Then, 2 volumes of the ice-cold stop solution (80% ethanol, 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate, 0.3 mM aurintricarboxylic acid) was added. Cultures were kept on ice for 20 min and harvested. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer, boiled for 4 min, and electrophoresed as described above, in a 2-mm-thick gel. After electrophoresis the wet gel was exposed for 5 to 15 min to an X-ray film to detect the induced RNA bands by autoradiography. Appropriate portions of the gel were cut out with a razor blade. The gel slice was added on top of another 12% PAG. After electrophoresis, the bands were identified again by wet autoradiography and, if necessary, purified on the third gel (13% PAG). After two or three runs the RNA was eluted from the gel slice in 10 volumes of elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl [pH 7.2]) by vigorous shaking for 4 to 8 h at 4°C. The mixture was centrifuged for 30 min at 3,000 × g, the supernatant was applied to a PREPAC mini-column (Gibco BRL), and RNA was eluted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. RNA was precipitated with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, and 2.5 volumes of cold ethanol. The purity of RNA was verified on a 5%–8% PAG. We usually obtained 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 32P cpm of homogenic RNA from 5 to 7 ml of labeled culture.

Hybridization with acid-induced RNA to the gene mapping membrane.

The gene mapping membrane (Takara Shuzo Co.) containing the recombinant lambda library from E. coli K-12 strain W3110 (29) was prehybridized for 18 h at 43°C in a solution containing 6× SSC (1× SSC = 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 5× Denhardt’s solution, 0.5% SDS, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), 50% formamide, denatured salmon sperm DNA (100 μg/ml), and 0.1-μg/ml concentrations each of 23S, 16S, and 5S rRNA. The 32P-labeled RNA probe (0.5 × 106 cpm) was added to the hybridization solution and hybridized for 18 h at 43°C. The membrane was washed at room temperature in 1× SSC–0.1% SDS and then twice in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS (30 min per wash) and exposed to X-ray film at −70°C overnight.

Northern blot hybridization.

Total RNA from 30-ml cultures was isolated by the guanidine isothiocyanate method (52). Acid induction was carried out as described above. RNA (15 to 30 μg) was electrophoresed in a 2% (wt/vol) formaldehyde-agarose gel. RNA was transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham) according to the protocol described by Sambrook et al. (52). Hybridization to the labeled DNA probe and posthybridization washes were performed following the same protocol as described above.

DNA methods.

Plasmid DNA was purified with a commercial plasmid purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Small-scale plasmid preparations from E. coli were made by the method of Holmes and Quigley (25). Cloning procedures were performed generally according to standard protocols (52). E. coli cells were transformed as described by Nishimura et al. (43). λ phage DNA (clone 311) containing the asr gene from the Kohara library was prepared with the λ-magic DNA purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Restriction enzymes and other DNA- and RNA-modifying enzymes were from AB Fermentas, Gibco BRL, Boehringer Mannheim, and U.S. Biochemicals. All enzymes were used as recommended by the suppliers. Restricted DNA fragments were separated in 1.0 to 2.0% (wt/vol) agarose (U.S. Biochemicals) and were purified with Gene Clean (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.).

Sequencing of the asr gene.

Plasmid pAS2 containing the asr gene was digested with PvuII; the resulting 1.5-kb fragment was purified and PCR amplified with M13 forward (5′-GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′) and reverse (5′-AAACAGCTATGACCATG-3′) sequencing primers (New England Biolabs). The resulting PCR products corresponding to the whole amplified asr DNA and to smaller fragments that had occurred by a fortuitous annealing of the primers to target DNA were sequenced as described by Krishnan et al. (30), with AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The M13 forward primer was found to anneal within a 1.5-kb noncoding asr DNA strand to a sequence complementary to the sequence 5′-GTTAACCCGATCACGAC-3′ (upstream from the asr DNA sequence [not shown]). The M13 reverse sequencing primer was found to anneal to the sequences complementary to asr DNA sequences 5′-GAGGGTATGACAATG-3′ and 5′-AAGCATCATAAAAATA-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 116 to 132 and 312–328 of the asr DNA sequence [see Fig. 3]). To allow the closure of a gap in the sequence near the left end of the asr DNA fragment and to determine the sequence of the second strand, synthetic custom oligonucleotide primers 5′-CTGGTGGGTAATTATGATTA-3′, 5′-AGGGGCTTTCTGTTCACC-3′, 5′-TAGAATAACTGCGCATCA-3′, and 5′-AACCCACTGCGGGGCCGT-3′ (designed according to the previously determined sequence) were used.

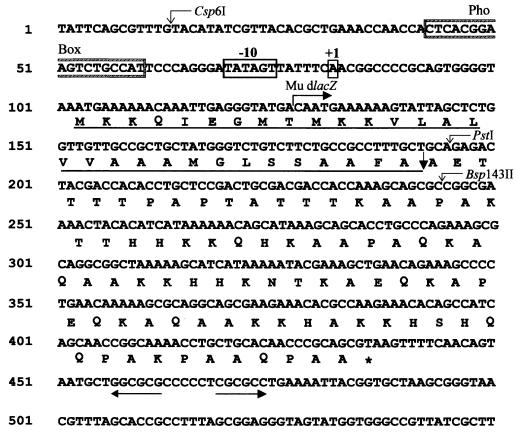

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the 600-bp DNA fragment bearing the E. coli asr gene. The transcription start site (+1) and −10 sequence are boxed. The deduced amino acid sequence of the ORF is shown (the asterisk indicates a stop codon). The computer-predicted signal peptide is underlined. A possible cleavage site of the signal sequence is indicated by the heavy downward-pointing arrow. A region similar to the consensus sequence for the PhoB regulated promoters (Pho box) is boxed and labeled. The pair of inverted arrows show a potential stem-loop structure. The integration site and orientation of the Mu d lacZ fusion within the asr gene is marked by the rightward-pointing arrow. Restriction enzyme cleavage sites are indicated by the thin downward-pointing arrows.

The DNA sequence was analyzed for gene elements by using CDSB (54) and NNPP/Prokaryotic (49) software. Codon usage was evaluated by using codon adaptation index calculations (53). GenBank/EMBL, SwissProt, and PIR databases were searched for homologies by using the Gapped BLAST program (2). Prediction of protein signal sequence, cellular localization, and transmembrane regions was performed with the TopPredII (11) and PSORT software (41). Links to servers containing these programs are found at the Marseilles University ABIM W3 server reference page (37a).

Allelic replacement of chromosomal asr gene.

The chromosomal knockout was performed essentially as described by Kulakauskas et al. (32). Plasmid pUC4K (Pharmacia) containing the Tn903 Kanr gene on a 1.3-kb cassette was restricted by PstI, the resulting fragment was ligated into PstI-restricted plasmid pAS3 bearing the asr gene, and the reaction mixture was used to transform strain HB101. Positive clones were verified by electrophoresis of PstI-digested plasmid DNA isolated from the transformants. The strain containing plasmid pAS4 with a mutagenized asr locus (asr::Kan) was infected with phage λ 311 to generate the recombinant phage carrying a Kan insertion within asr. Phage λ 311::Kan was used to infect strain N2212 to induce allelic replacement of the asr allele on the chromosome. The chromosomal asr::Kan mutants were verified by Southern hybridization using 32P-labeled asr DNA fragment as a probe.

PCR amplification.

PCR was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus thermocycler (model 480) with AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The cycling program was as follows: 30 cycles with a denaturation step at 94°C for 20 s, annealing at appropriate temperatures for 40 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min. PCR-amplified products were analyzed in 1 to 2% agarose gels.

Plasmid insertional mutagenesis and asr-lacZ operon fusions with the mini-Mu bacteriophage transposon.

The procedures were performed as described by Groisman (20). Plasmid pAS6 containing the asr gene was used to transform strain POI1734 (9) harboring the mini-Mu element and a helper phage. The resulting strain containing pAS6 was used to prepare a lysate of mini-Mu. The lysate was used to transduce strain M8820 Mu cts (9). Transductants with an insertion in the asr gene on the plasmid were screened by plating the culture on an LPM that was buffered with 0.1 M MES (pH 5.0) and contained ampicilin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (50 μg/ml). After 36 h of incubation at 32°C, dark-blue colonies were picked up, and plasmid DNAs were isolated. Mu d insertions into the asr gene were verified by the electrophoresis of restricted plasmid DNA fragments and a subsequent hybridization to a 32P-labeled DNA fragment with the asr gene. The exact location of insertions was determined by sequencing plasmid DNA with primers complementary to both ends of the inserted DNA fragment.

Primer extension analysis.

Primer extension analysis was performed by using a 19-nt oligodeoxyribonucleotide (5′-ACAGACCCATAGCAGCGGC-3′) complementary to the asr coding sequence 29 nt downstream of the mini-Mu insertion at position 127 in the asr DNA sequence given in Fig. 3. The procedures were generally performed as described by Sambrook et al. (52).

Expression of asr and phoB genes.

To identify the asr gene product, the 706-bp Csp6I DNA fragment from plasmid pAS2 was subcloned into the expression vector pT7-6, yielding pAS5, and subsequently transformed into E. coli HB101 harboring plasmid pGP1-4 with a gene coding for T7 RNA polymerase (59). Strains containing pGP1-4 and recombinant plasmid or parental vector, pT7-6, as a control were induced and 35S-labeled (Tran35S label; ICN Biomedical, Inc.) as described previously (59). Cell proteins (see below) were resolved on an SDS-PAG (33), which was subsequently dried and exposed to X-ray film for 24 h.

For expression of PhoB protein in E. coli ANCH1 and ANCK10 cells, a 2.0-kb MluI fragment on plasmid pBC6ΔPstI (65) with the phoB gene was subcloned into the pT7-6 vector at the SmaI site downstream from the phage T7 polymerase promoter. PhoB expression from the resulting plasmid pVG6 was achieved by the temperature induction of T7 RNA polymerase (pGP1-4) as described by Tabor and Richardson (59).

Preparation of cell extracts.

Cultures (300 ml) were grown in LB medium at 30°C to an optical density of 0.8 at 560 nm and harvested by low-speed centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in sonication buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [100 μg/ml]). Samples were sonicated with four 30-s bursts. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g, and the supernatant was used as a crude cell extract for mobility shift assays.

Gel mobility shift assays.

The 181-bp Csp6I-PstI DNA fragment containing the promoter region of the E. coli asr gene was 32P labeled with a Klenow fragment. E. coli protein extracts were incubated with ∼4,000 cpm of 32P-end-labeled DNA fragment in the presence of 0.5 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) and/or pBR322 DNA in a final volume of 20 μl. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a solution of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, bovine serum albumin (50 μg/ml), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.05% Nonidet P-40. After incubation, 2 μl of loading buffer (50% glycerol in binding buffer plus 0.1 mg of bromphenol blue per ml) was added, and the samples were loaded immediately on a nondenaturing vertical 5% PAG with the current on. The electrophoresis buffer consisted of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8)–1 mM EDTA. Following electrophoresis the wet gel was autoradiographed at −70°C overnight.

Western immunoblot analysis.

E. coli proteins were separated by electrophoresis in an SDS–10% PAG, and fractionated proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). The membrane was incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-PhoB antibody diluted 1:500. Binding of the primary antibody was evaluated by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugate (Amersham) and developing with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as described previously (3).

Preparation of polyclonal anti-PhoB antibody.

E. coli ANCK10 harboring pVG6 and pGP1-4 was grown in LB medium to an A600 of 0.3. Cells were induced for PhoB synthesis by a temperature upshift, and incubation was continued for an additional 6 to 8 h. A crude cell extract was prepared by sonication as described above. Cell proteins were separated by SDS-PAG electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The overexpressed PhoB protein was cut out after preparative gel electrophoresis, electroeluted, and used for rabbit immunization. The rabbits initially received a subcutaneous injection of 100 μg of PhoB protein emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant. Three booster injections of 40 μg of purified PhoB protein emulsified in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant were given once every subsequent 2 weeks. The rabbits were bled 2 weeks after the last injection, and the blood serum was analyzed for the presence of PhoB-specific antibody by Western immunoblot analysis. The nonspecific antibodies in the serum were adsorbed to a supernatant prepared from a sonicated culture of ANCH1 (phoB-phoR) strain according to the procedure of Yamada et al. (70).

Alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase assays.

Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined as described by VanBogelen et al. (61), with para-nitro-phenyl-phosphate as a substrate. Specific activity units are expressed as nanomoles of product formed per minute per cell culture optical density at 600 nm. For qualitative assay of alkaline phosphatase, agar plates were supplemented with XP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) (40 μg/ml) as a chromogenic substrate.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined from an asr::lacZ fusion strain according to the method of Miller (40).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence for the asr gene has been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. L25410.

RESULTS

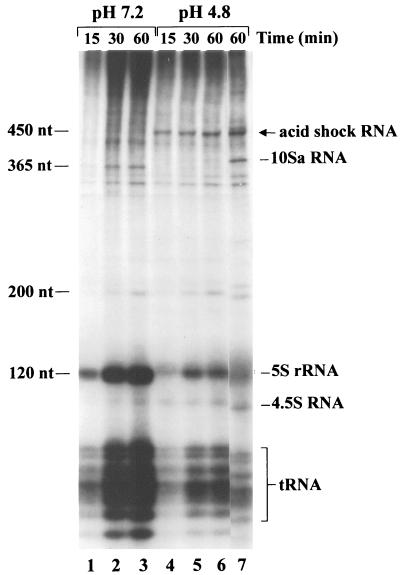

Identification of a unique RNA component inducible by low external pH.

An acid shift of growth media from pH 7.0 to a pH of 5.0 to 4.0 strongly induces a new RNA component, which could be identified on PAG after the electrophoresis of total in vivo 32P-labeled E. coli RNA. Figure 1 shows the electrophoretic pattern obtained for small RNA molecules (50 to 1,000 nt) from extracts of cells grown in the LPM (pH 7.0) and after acidification to pH 4.8 (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 3 and 4 to 7, respectively). The molecule, which we designated acid shock RNA, migrates in the region of two previously well characterized (10, 58) small E. coli RNAs, namely, 10Sa (365 nt [Fig. 1]) and its precursor, p10Sa (∼462 nt [not shown]). According to the mobility on the gel, the approximate size of the newly identified RNA molecule lies between 400 and 450 nt. Acid-inducible RNA appears to be one of the most highly labeled small RNAs in the cell under the present conditions, indicating a high rate of synthesis. Accumulation of this RNA component upon acid shift was observed in all E. coli K-12 laboratory strains tested.

FIG. 1.

Induction of acid shock RNA in E. coli K-12 strains. Cells were grown, acid induced, and 32P labeled as described in Materials and Methods. At the indicated times after the addition of 32Pi (added to the cultures at 30 min after shifting the pH of growth medium from 7.0 to 4.8, and added at the same time to control cultures [pH 7.0]), samples were taken and cell lysates were separated on 5%–8% polyacrylamide gel (the 5% part of the gel is not shown). Samples (2.5 × 105 cpm) were loaded on the gel. Lanes 1 to 3 and 4 to 6 contain RNAs derived from strain N2212 (10Sa RNA mutant) grown in LPM (pH 7.0) and after acid shift from pH 7.0 to 4.8, respectively. Lane 7 contains RNA derived from strain D10 (10Sa RNA-producing wild-type strain) grown in the same medium, pH shifted to 4.8. Various small E. coli RNA species are indicated. RNA lengths are shown at left. Acid shock RNA is indicated.

We analyzed the stability of the newly identified RNA in bacterial cells. E. coli D10 cells were grown in LPM, acid induced, and 32P labeled as described in Materials and Methods. Transcription initiation in the acid-induced E. coli culture (pH 4.8) was blocked by the addition of rifampin, and aliquots were removed at appropriate intervals for RNA preparation. We observed that acid shock RNA is long lived (Fig. 2) compared to other 32P-labeled bacterial transcripts and shows a half-life of >15 min (stable E. coli 10Sa RNA and other unidentified stable E. coli RNA of ∼300 nt are indicated).

FIG. 2.

Stability of acid shock RNA. Cells from strain D10 were grown in LPM (pH 7.0) to a density of ∼108 cells ml−1, and then the pH was shifted down from 7.0 to 4.8 and the incubation was continued. Cells were 32P labeled as described in Materials and Methods. At 30 min after 32Pi addition, rifampin was added to the culture at a final concentration of 400 μg/ml, and probes (2 ml) were sampled at appropriate intervals as indicated. Cell lysates (2.5 × 105 cpm) were separated on a 5%-8% polyacrylamide gel (only the 8% part is shown). Acid shock RNA is shown by the rightward-pointing arrow. Asterisks indicate the positions of stable E. coli 10Sa RNA (365 nt) and a stable unidentified RNA molecule (∼300 nt). The downward-pointing arrow indicates the addition of rifampin to the culture. The lengths of E. coli RNAs are indicated on the right.

Mapping and cloning of the asr gene.

In order to identify its coding locus on the E. coli chromosome, acid-induced RNA was purified as described in Materials and Methods. To avoid contamination with the 10Sa RNA molecule, which migrates in the gel close to the newly observed RNA, E. coli N2212 was chosen for purification. It contains a chromosomal insertion within the 10Sa RNA coding region, and the cells do not produce any detectable levels of this molecule (44). The purified acid shock RNA appeared as a single band when electrophoresed on a PAG (data not shown) and was used as a probe in hybridization to the lambda phage E. coli chromosomal library of Kohara et al. (29). One single phage clone (λ 311) was found to hybridize to acid-induced RNA (data not shown). To further define the map position, 32P-labeled acid shock RNA was used as a probe to identify hybridizing bands among size-fractionated restriction digests of λ 311 DNA. The smallest single fragment that hybridized to the RNA probe was an ∼1.3-kb PvuII-BglI DNA fragment. The same result was obtained with E. coli chromosomal DNA digests (data not shown). These findings localized the acid shock RNA gene to 35.98 min on the E. coli chromosome between the mlc gene (35.9 min) and pntBA operon (36.06 min) (31). We designated the new gene asr (for acid shock RNA).

The 1.3-kb asr containing PvuII-BglI fragment from λ clone 311 DNA containing asr was subcloned into the pUC19 vector, yielding pAS2. E. coli N2212 bearing pAS2 was assayed for the ability to synthesize RNA upon acid shock. The amount of acid shock RNA upon acidification of the growth medium was only about twofold higher than that in the wild-type strain, as observed by in vivo 32P-labeled RNA PAGE (data not shown). The low expression level of asr when placed on the multicopy plasmid suggests a regulator-dependent manner of induction commonly found among genes and operons inducible by environmental stimuli.

Nucleotide sequence of the asr region.

The 1,295-bp DNA fragment derived from plasmid pAS2 was sequenced by the DNA cycle sequencing method described by Krishnan et al. (30). Six hundred nucleotides encompassing the asr coding region are presented in Fig. 3. The largest open reading frame (ORF) deduced from the DNA sequence (54) extends from bp 103 to 436 and corresponds to a polypeptide of 111 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of about 11.6 kDa. There are two additional in-frame methionine codons corresponding to amino acid positions 8 and 10, shown in Fig. 3. The exact ATG codon used for the initiation of translation is currently unknown. Sequence analysis did not reveal a significant Shine-Dalgarno sequence preceeding the first ATG codon of this ORF. The sequence GAGGG (nt 118 to 122 in Fig. 3) is a plausible Shine-Dalgarno sequence if the second or third ATG codon is used as a translational start. Beyond the UAA stop codon of the asr gene, a potential DNA structure (from bp 458 to 475 [Fig. 3]) consisting of a 7-base loop and a 6-base stem (free energy, −13.8 kcal) (60) was found. This structure most likely represents a ρ-independent transcriptional terminator of the asr gene. Computer-assisted analysis done with this ORF revealed that its N terminus (30 amino acids [Fig. 3]) exhibits all the properties of a signal sequence regardless of which ATG is used as the translation initiation codon. The possible cleavage site is predicted at amino acid 30 of the longest polypeptide synthesized from the first ATG (Fig. 3) (41). According to sequence analysis, the predicted polypeptide contains one hydrophobic putative membrane-spanning segment at the N terminus (amino acids 10 to 31 [Fig. 3]). The computer-predicted features for the asr polypeptide therefore suggest it to be either a periplasmic or an outer membrane protein (41).

The amino acid sequence of the ORF was compared to the proteins in the SwissProt and PIR databases (2). However, this ORF showed no striking homology to any protein known in the databases so far. Some degree of sequence identity has been observed between the asr putative polypeptide and some E. coli proteins; however, all identical amino acids lie in the regions of repetitive amino acids and, most likely, are not significant.

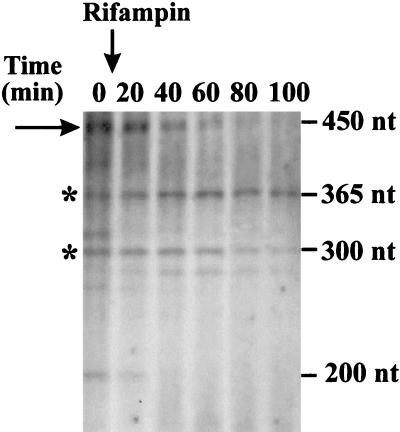

Identification of transcriptional start for acid-inducible RNA.

To identify a transcriptional start point of the acid-inducible RNA, we first determined the direction of transcription of the asr gene by generating mini-Mu transposon-mediated lacZ fusions. Plasmid pAS6 bearing the asr gene was mutagenized with mini-Mu as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting transductants containing transcriptional lacZ fusions within the asr gene were selected for their ability to form dark-blue colonies upon plating on the LPM (pH 5.0). Screening by Southern blot of plasmid DNA derived from such transductants indicated that the transposon has inserted the 1.3-kb asr containing fragment close to the PstI restriction site. The exact location was confirmed by plasmid DNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 3, position 127 in the asr DNA sequence). The direction of transcription of the lacZ gene was found to be identical to that of the putative ORF. These results indicated that the promoter for the asr gene was located upstream of the putative ORF. Primer extension analysis was performed with total RNA isolated from strain N2212 grown in LPM (pH 7.0) and after acid shift to pH 4.8. The primer used for extension corresponded to nt 157 to 175 in the asr sequence (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 4, an extended product was observed only with RNA isolated from cells that had been exposed to an acid shock (lane 2). The transcriptional start site for the asr gene was identified as the adenine residue (Fig. 4). Ten nucleotides upstream from the transcriptional initiation site, there is a sequence (TATAGT), highly similar to the consensus hexanucleotide −10 box (TATAAT) found in E. coli ς70-dependent promoters, whereas a region 35 bp away from the transcription start poorly matched the consensus −35 sequence (CGGAAG versus TTGACA), suggesting that the asr promoter represents a positively regulated promoter (50).

FIG. 4.

Identification of the transcriptional start site for the acid-induced RNA. Lanes 1 and 2 contain primer extension products obtained with RNA that was isolated from strain N2212 grown in the LPM (pH 7.0) or after the shift down from pH 7.0 to pH 5.0, respectively. A 19-nt primer complementary to nt from 157 to 175 of the asr DNA sequence shown in Fig. 3 was used for extension. Lanes containing a DNA sequencing ladder generated with the same primer and plasmid pAS2 are indicated by the letters. The nucleotide sequence of the region near the transcription start (the transcription start is indicated by the asterisk) is shown.

Expression of the asr gene in vivo.

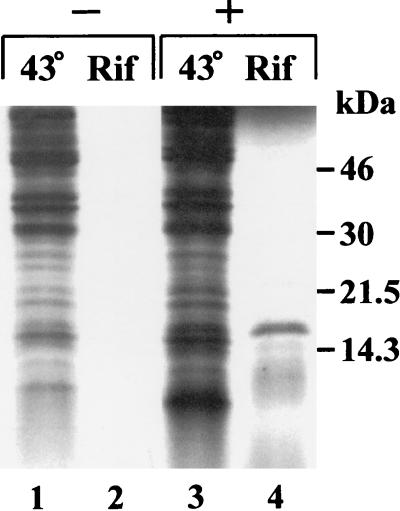

As was shown by the primer extension analysis, the promoter region for the asr gene is located upstream from the ORF which codes for a putative polypeptide with a molecular mass of ∼11.6 kDa. A 706-bp Csp6I DNA fragment from plasmid pAS2 carrying the asr gene was subcloned in a proper orientation into the pT7-6 expression vector to make pAS5 and subsequently transformed into strain HB101 containing pGP1-4 with the gene encoding phage T7 RNA polymerase (59). Systems containing pGP1-4 and pAS5 or control vector, pT7-6, were activated by temperature shift, and 35S-labeled proteins from both cultures were electrophoresed in an SDS-PAG (see Materials and Methods). Figure 5 shows the electrophoretic pattern of cell proteins obtained from induced cultures. Cells containing plasmid pAS5 synthesize a polypeptide migrating as an 18-kDa entity in SDS-PAG, which is the only 35S-labeled protein when the host RNA synthesis is blocked by rifampin (Fig. 5, lane 4). No synthesized protein has been observed in temperature-induced E. coli cells harboring plasmids pGP1-4 and pT7-6 with the cloned asr gene from which the downstream part from bp 286 to 600 was deleted. (Fig. 3) (data not shown) The deleted fragment contained the only reasonable ORF—the putative asr ORF. Since the deletion abolished the synthesis of the 18-kDa polypeptide, we conclude that it represents an asr gene product despite its decreased electrophoretic mobility relative to the deduced molecular mass (11.6 kDa). As can be seen in Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 4, the electrophoretic mobility of the 18.0-kDa polypeptide is identical to that of the pool of other cell proteins, and the synthesized product cannot be detected in whole extracts prepared from cells induced for the synthesis of T7 RNA polymerase (without addition of rifampin [Fig. 5, lane 3]). Inefficient translation or low content in the soluble fraction would make the translated product “invisible” in the pool of cellular proteins.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE of the proteins synthesized in E. coli using the T7 polymerase/promoter system. Labeling was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The absence (−) or presence (+) of the asr gene in the pT7-6 plasmid is indicated. Lanes 1 and 3 contain material obtained from the induced cultures with no rifampin (Rif) added. Lane 4 contains a polypeptide expressed from the asr gene (about 18 kDa as determined by protein molecular mass markers, whose mobilities are shown on the right).

Characterization of the mutant with a chromosomal asr knockout.

A chromosomal asr knockout mutation was generated by allelic replacement as described in Materials and Methods. The 1.3-kb Kanr gene cassette derived from plasmid pUC4K was inserted into the PstI site of the asr coding sequence. The asr::Kan mutation in the resulting JE13 strain was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization of chromosomal DNA restriction digests with 32P-labeled 1.3-kb BamHI-EcoRI asr DNA fragment, derived from plasmid pAS2 (data not shown). The asr-negative strain JE13 and its parental strain, N2212, were tested for growth ability in LB, LPM, and MOPS MM, all at pH 7.0 and pH 5.0. No obvious differences in either growth rate in liquid medium or colony formation were observed between the two strains. Likewise, cell viability after acidification (pH 5.0) of liquid LB, LPM, or MOPS MM and subsequent plating on the LB agar (pH 7.0) was not affected in the asr mutant.

Effect of other stresses and growth medium on acid-induced asr expression.

Several studies (23, 24) have demonstrated that the acidification of growth medium causes in microorganisms increased expression of proteins known to be inducible by heat shock, osmotic shock, and low temperature. Neither heat shock nor osmotic shock nor shift to a low temperature (10°C) resulted in the induction of the acid shock RNA (data not shown). A recA mutant known to be defective in the E. coli SOS response behaved like the wild-type strain with respect to its ability to induce asr-specific RNA (data not shown), suggesting that expression of the asr gene is not a part of this global regulatory system (63).

Treatment of E. coli cells with weak acids able to permeate the membrane, such as benzoic acid (benzoate) and salicylic acid (salicylate), known to reduce the cytoplasmic pH (51), did not result in asr induction (not shown). These data suggest that asr is specifically induced by an external acidity.

Next, we examined the effect of growth medium on acid-induced expression of the asr gene. The peptone-containing LPM, which was used for in vivo 32P labeling (see Materials and Methods) and acid induction of the asr gene, contains less phosphate than rich LB broth and permits an efficient incorporation of the added 32P label (28). Starvation for phosphate as an additional stress stimulus might be involved in acid-induced expression of the asr gene. To examine a possible phosphate effect, duplicate sets of cultures of E. coli M8820 with asr::lacZ fusion in the plasmid pAS8 (Table 1) were grown in MOPS-buffered (pH 7.0) LB medium, in LPM, and in MOPS MM with either 0.01 or 1 mM phosphate (see Materials and Methods). After a shift from pH 7.0 to pH 4.8, asr expression was analyzed by measuring the β-galactosidase activity. The level of β-galactosidase was reduced approximately 10- to 15-fold in acid-induced cells grown in LB medium compared to those cultured either in LPM or in MOPS MM (Fig. 6). The results of β-galactosidase assay of acid-induced E. coli cells grown in MOPS MM with excess or limited phosphate show that phosphate limitation does not significantly influence the asr expression (Fig. 6). The phosphate stress conditions were confirmed by a >30-fold increase of alkaline phosphatase activity in E. coli cells grown in minimal medium (pH 4.8) with 0.01 M phosphate (108 ± 4 U [mean ± standard error of the mean for three values]) compared to those grown in the same medium with 1 mM phosphate (3.2 ± 0.06 U).

FIG. 6.

β-Galactosidase activities from the strain containing the asr::lacZ fusion plasmid pAS8 in different growth media at pH 7.0 and upon acid shift from pH 7.0 to 4.8. The media used for analysis were LB medium, peptone-containing LPM, and MOPS MM with 0.1 or 1 mM phosphate (low and high Pi, respectively). Cells were grown and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are given in Miller units. Each value corresponds to the mean of triplicate values (error bars, standard errors of the means).

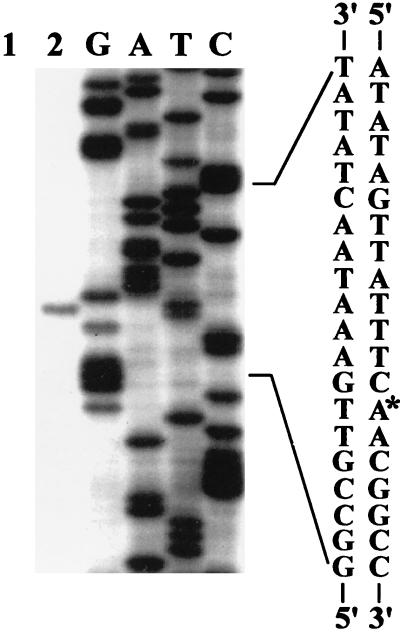

The phoB-phoR deletion mutant fails to induce acid shock RNA.

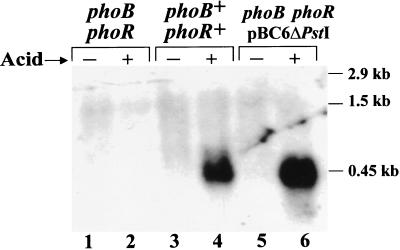

While testing the phosphate effect on asr expression, we also examined a possible involvement of phoB-phoR, a two-component regulatory system that regulates expression of a number of E. coli genes (the pho regulon) known to be inducible by phosphate starvation (64). The phoR product is a protein-histidine kinase, which when autophosphorylated (at phosphate starvation) phosphorylates PhoB, a transcriptional activator of genes belonging to the pho regulon (34, 35). The mutant strain ANCH1 with a chromosomal deletion of the entire phoB-phoR operon (70) was tested for the ability to induce acid shock RNA upon a shift from pH 7.0 to 4.8. We found that the transcription of asr was completely abolished in the phoB-phoR deletion mutant in contrast to the wild-type strain ANCK10 (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). The same results have been obtained with the ANCH1 strain containing either phoB (pVG12) or phoR (pVG11) (data not shown). Introduction of the plasmid pBC6ΔPstI with cloned E. coli phoB-phoR operon into strain ANCH1 restored the acid-mediated induction of the asr gene (Fig. 7, lane 6).

FIG. 7.

Northern blot analysis of total cellular RNA isolated from strain ANCH1 (ΔphoB-phoR) (lanes 1 and 2), strain ANCK10 (wild type) (lanes 3 and 4), and strain ANCH1 with plasmid pBC6ΔPstI (lanes 5 and 6). Cells were grown in the LPM, pH 7.0 (−), and after acid shift from pH 7.0 to 4.8 (+). RNA (30 μg) was loaded into each lane. A 32P-labeled 0.7-kb E. coli DNA fragment containing the asr gene was used as a hybridization probe. Positions of the asr mRNA (∼0.45 kb) and RNA markers (2.9 and 1.5 kb) are indicated.

The regulatory protein PhoB is known to bind specifically to a conserved DNA region consisting of 18 nt (the Pho box), which is a part of promoters for the genes belonging to the pho regulon (35). Upstream from the −10 region of the asr promoter there is an 18-nt region (CTCACGGAAGTCTGCCAT [Fig. 3]), which is similar to the consensus sequence (CTGTCATAAAACTGTCAT) of the Pho box. A 10-base space between the −10 region and the Pho box is common (35). The −10 sequence assigned for the asr promoter (TATAGT) is located 9 bases from the proposed Pho box (Fig. 3).

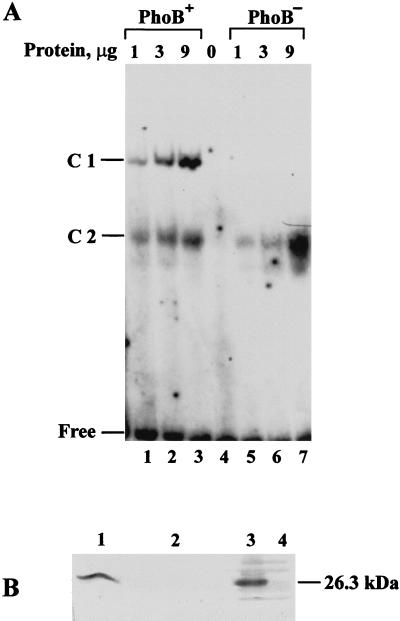

We analyzed whether the asr DNA fragment containing the proposed Pho box is capable of binding PhoB protein in vitro. The 181-bp Csp6I/PstI DNA fragment with a promoter region of the asr gene was 32P labeled and analyzed for binding with E. coli proteins extracted from ANCH1 cells (ΔphoB-phoR) and from the same cells overexpressing PhoB protein (see Materials and Methods). Results of electrophoretic mobility shift assays are presented in Fig. 8. Incubation of the asr DNA fragment with protein extracts prepared from PhoB-producing E. coli ANCH1 cells resulted in the formation of two 32P-labeled asr DNA-protein complexes, C1 and C2 (Fig. 8A). The complex with the lower electrophoretic mobility, C1, was not observed with proteins of ANCH1 (ΔphoB-phoR) cells (Fig. 8A, lanes 5 to 7). Analogous binding results have been obtained with the 32P-labeled E. coli phoB promoter DNA fragment containing the Pho box, which was used as a positive control (36) (data not shown). The binding was effectively competed in the presence of an excess of unlabeled asr DNA, but not plasmid pBR322 DNA or poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) (data not shown). No specific retarded complex was observed when a promoterless asr DNA fragment was used (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

(A) Gel mobility shift analysis for the binding of E. coli proteins to a promoter of the asr gene. Binding conditions are described in Materials and Methods. Increasing concentrations of the proteins from PhoB-producing ANCH1 cell extracts (PhoB+) (lanes 1 to 3) and the same cells with the expression vector pT7-6 only (PhoB−) (lanes 5 to 7) were incubated with 32P-labeled asr promoter DNA. Reaction mixtures were loaded on a 5% nondenaturing PAG and electrophoresed. The gel was analyzed by autoradiography. Positions of the free 32P-labeled asr DNA and DNA-protein complexes C1 and C2 are indicated on the left. (B) Western blot analysis of the proteins bound to the asr promoter DNA in complexes C1 and C2. Gel fragments with the retarded 32P-labeled asr DNA C1 and C2 were cut from the PAG, denatured, and polymerized into SDS–10% PAG (lanes 1 and 2, respectively). As controls, protein extracts (5 μg) obtained from PhoB-producing ANCH1 cells (PhoB+) (lane 3) and the same cells with the expression vector pT7-6 only (PhoB−) (lane 4) were precasted in the similar fragments of the nondenaturing PAG, denatured, and polymerized side-by-side. After electrophoresis, separated proteins were analyzed with the polyclonal antibodies raised against PhoB protein. The position and molecular mass of the PhoB protein identified in the E. coli cell extract are indicated on the right.

Proteins present in the retarded 32P-labeled asr DNA-protein complexes C1 and C2 were examined by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antibody raised against PhoB protein (see Materials and Methods). Anti-PhoB antibody specifically interacts with the protein released from the asr DNA-protein complex C1 (Fig. 8A, lanes 1 to 3). According to the electrophoretic mobility under SDS-PAGE conditions, the molecular mass of this polypeptide is identical to that of PhoB protein (26.3 kDa) as determined by Western blot analysis in PhoB-producing E. coli protein extracts (Fig. 8B, lane 3). These results indicate that E. coli activator protein PhoB is capable of binding asr promoter DNA in vitro, suggesting that this interaction is important for the asr transcription, which is also supported by the lack of asr transcript in phoB mutant cells. A faster migrating asr DNA-protein complex, C2, observed with the E. coli proteins derived from PhoB-producing (ANCH1/pVG6) and phoB mutant (ANCH1) cells (Fig. 8A, lanes 1 to 3 and 5 to 7, respectively), most probably is formed by another E. coli protein, which is not recognized by the anti-PhoB antibody but shows some affinity to the target asr DNA sequence.

DISCUSSION

Acid shift of growth medium from pH 7.0 to a pH of 5.0 to 4.0 strongly induces a novel E. coli RNA component which does not correspond to any previously characterized small RNA (27). Synthesis of the major small stable E. coli RNAs, such as 5S rRNA and tRNAs, is markedly decreased during acid shift as a consequence of a drop in growth and metabolic processes caused by acid stress. The relative amount of the acid shock RNA is comparable to that of pools of specific tRNAs and is about 1.5-fold higher than that of 10Sa RNA (10). The observed RNA under inducing conditions therefore represents one of the most abundant small RNA species in the cell. Rifampin decay experiments performed with acid-induced RNA demonstrate that it is long-lived bacterial RNA with a half-life of about 15 min.

The chromosomal location and organization of the asr region does not indicate asr to be a part of an operon known to be inducible by low external pH (38, 68) or presumably a part of any other E. coli operon (there are ∼100- and 300-bp noncoding sequences extending from the respective sides of the asr locus). The asr-specific sequence has been observed in all tested E. coli laboratory K-12 strains as well as in enteropathogenic E. coli strains (data not shown).

The gene encoding acid shock RNA contains an ORF that, if translated, would yield an ∼11.6-kDa polypeptide. Computer-assisted analysis demonstrated that the codons used in this ORF are highly preferred in E. coli protein-coding genes (53). Expression of the asr gene after transcription using the T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system defined a single polypeptide, which migrates in SDS-PAGE as an ∼18 kDa protein. No synthesized protein has been observed upon induction of E. coli cells containing the expression vector only and cells with the truncated asr gene cloned in plasmid pT7-6 downstream from phage T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The molecular mass of the identified polypeptide does not exactly match the molecular mass of the polypeptide deduced from the asr DNA sequence. A reason for this disagreement might be physicochemical properties of the asr protein.

Furthermore, the first 30 amino acids of the deduced sequence possess all common features for a prokaryotic signal sequence, suggesting that the asr gene encodes a secretory protein. Hydropathy profile analysis (43) (data not shown) of the putative polypeptide indicated the presence of one cluster of hydrophobic amino acids (amino acid positions 10 to 31 [Fig. 3]) located at its N terminus. According to the computer-predicted features, the asr polypeptide might be located either in the periplasm or in the outer membrane of the cell.

Analysis of the asr knockout mutant did not, however, shed light on a possible function for the asr gene product. Our data suggest that it is not essential for cell growth and survival under acid shock and its function is dispensable under the presently used growth conditions.

Most low-pH-inducible genes in E. coli and S. typhimurium were demonstrated to respond to other environmental stimuli (1, 13, 15, 55). Transcriptional analysis of the asr gene revealed that acid-mediated induction is significantly inhibited in complex (LB) medium compared to our LPM and MM, implying the existence of another regulatory component. Tests of individual constituents of LB medium indicated that yeast extract inhibited pH-induced expression of the asr gene (data not shown), although its component responsible for the inhibition is currently unknown.

While starvation for phosphate as an additional stimulus was not found to influence expression of the asr gene, acid-triggered induction requires an intact phoB-phoR system controlling E. coli genes (pho) inducible by phosphate starvation (64, 67). Analysis of the asr gene revealed that its promoter region contains a sequence similar to the Pho box of PhoB-regulated promoters. DNA electrophoretic mobility shift experiments performed with protein extracts derived from PhoB-producing and phoB mutant strain demonstrated that PhoB protein indeed is able to bind a promoter DNA of the asr gene. All the above findings argue that E. coli might employ the two-component PhoB-PhoR regulatory system to mediate the low-pH-induced expression of the asr gene.

The intriguing question is this: how is acidity of the growth medium sensed? The periplasmic domain of the sensory kinase PhoQ of the S. typhimurium two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ has been demonstrated to sense directly Mg2+ cations in the periplasm (16, 17, 62). Recent observations in Salmonella argue that PhoQ is an acid shock protein and, possibly, senses pH (5). Some genes of the E. coli and Bacillus subtilis Pho regulons have been demonstrated to respond to other environmental factors, such as carbon, nitrogen starvation, anaerobiosis, UV light, and catabolites, although neither has the acidity of the medium as an inducer been reported nor has the involvement of a regulatory system phoB-phoR in transducing such environmental signals been reported (26, 66).

Treatment with weak acids able to permeate membranes, such as sodium benzoate and sodium salicylate, known to depress the cytoplasmic pH (51), did not result in asr induction (data not shown). Thus, the induction of asr occurs exclusively in response to external acidification, suggesting the existence of an external sensor.

We suggest a model in which H+, directly, or via its acceptor, might activate a sensor protein (PhoR) in the periplasm, which rapidly reflects changes in the extracellular pH. Signal is further transduced to an activator protein (PhoB) or to another regulatory factor, produced by the cell in response to acidification, or both. The interaction or cumulative action of PhoB protein and the putative factor lead to asr transcription. Such a model would explain the absence of the asr induction at neutral pH in the medium with low phosphate concentration, when the components of the phoB-phoR system are in abundance, as well as the presence of induction of the asr at low pH and high phosphate, when a low level of both proteins is present. Different models in which a yet-unknown factor regulates PhoR in response to acidification cannot be excluded, however. Further analysis will hopefully reveal new factors and their roles employed by bacteria facing acid stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mitsuko Amemura and Barry Wanner for bacterial strains, Douglas Berg for providing of the sequencing and computer facilities, Violeta Šiaudinytė for skillful technical assistance, and Fermentas AB for the gift of some enzymes.

This work was supported by a grant from the Institutional Markey Award Foundation and by grant 219/2490-2 from the Lithuanian State Program “Molecular Background of Biotechnology.”

Footnotes

Dedicated to David Apirion, whose death in 1992 was the loss of a devoted scientist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliabadi Z, Park Y K, Slonczewski J L, Foster J W. Novel regulatory loci controlling oxygen- and pH-regulated gene expression in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:842–851. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.842-851.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3398–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. N.Y: Green Publishing and Wiley-Interscience; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearson B L, Wilson L, Foster J W. A low pH-inducible, PhoPQ-dependent acid tolerance response protects Salmonella typhimurium against inorganic acid stress. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2409–2417. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2409-2417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bearson S, Bearson B, Foster J W. Acid stress responses in enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;147:173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolivar F, Backman K. Plasmids of Escherichia coli as cloning vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:245. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casabadan M J. Fusion of the Escherichia coli lac genes to the ara promoter: a general technique using bacteriophage Mu-1 insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:809–813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casabadan M J, Cohen S N. Lactose genes fused to exogenous promoters in one step using a Mu-lac bacteriophage: in vivo probe for transcriptional control sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4530–4533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castilho B A, Olfson P, Casadaban M J. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-Mu bacteriophage transposon. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:488–495. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.488-495.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chauhan A K, Apirion D. The gene for a small stable RNA (10Sa RNA) of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1481–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claros M G, von Heijne G. TopPredII: and improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:3997–4001. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster J W. Low pH adaptation and the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:215–237. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster J W, Aliabadi Z. pH-regulated gene expression in Salmonella: genetic analysis of aniG and cloning of the earA regulator. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1605–1615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster J W, Hall H K. Adaptive acidification tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:771–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.771-778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster J W, Park Y K, Bang I S, Karem K, Betts H, Hall H K, Shaw E. Regulatory circuits involved with pH-regulated gene expression in Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology. 1994;140:341–352. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia Véscovi E, Ayala Y, Di Cera E, Groisman E A. Characterization of the bacterial sensor protein PhoQ. Evidence for distinct binding sites for Mg2+ and Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1440–1443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia Véscovi E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gegenheimer P, Watson N, Apirion D. Multiple pathways for primary processing of ribosomal RNA in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:3064–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodson M, Rowbury R J. Habituation to normally lethal acidity by prior growth of Escherichia coli at a sublethal acid pH value. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groisman E A. In vivo genetic engineering with bacteriophage Mu. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:180–212. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04010-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersh B M, Farooq F T, Barstad D N, Blankenhorn D L, Slonczewski J L. A glutamate-dependent acid resistance gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3978–3981. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3978-3981.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyde M, Coll J-L, Portalier R. Identification of Escherichia coli genes whose expression increases as a function of external pH. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;208:511–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00272156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyde M, Portalier R. Acid shock proteins of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;69:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90406-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickey E W, Hirshfield I N. Low-pH-induced effects on patterns of protein synthesis and on internal pH in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1038–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1038-1045.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes D S, Quigley M. A rapid boiling method for the preparation of bacterial plasmids. Anal Biochem. 1981;114:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulett M F. The signal-transduction network for Pho regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:933–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.421953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye M, Delihas N. Small RNAs in the prokaryotes: a growing list of diverse roles. Cell. 1988;53:5–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan R, Apirion D. The fate of ribosomes in Escherichia coli cells starved for a carbon source. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1854–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application for new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnan B R, Blakesley R W, Berg D E. Linear amplification DNA sequencing directly from single phage plaques and bacterial colonies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1153. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kröger M, Wahl R. Compilation of DNA sequences of Escherichia coli K-12: description of interactive databases ECD and ECDC (version 1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:46–49. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulakauskas S, Wikström P M, Berg D E. Efficient introduction of cloned mutant alleles into the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2633–2638. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2633-2638.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, Yamada M, Nakata A. Signal transduction in the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli involves phosphotransfer between PhoR and PhoB proteins. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:551–559. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Kimura S, Nakata A. Activation of pstS transcription by PhoB protein in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the phoB gene, the positive regulatory gene for the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1986;190:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Cloning and characterization of the alkaline phosphatase positive regulatory gene (phoM) of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:381–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00341438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Marseilles University ABIM W3 Server Reference Page.http://www-biol.univ-mrs.fr/english/biology.html. [17 February 1999, last date accessed.]

- 38.Médique C, Boushé J P, Hénaut A, Danchin A. Mapping of sequenced genes (700 Kbp) in the restriction map of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng S-Y, Bennett G N. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli cad operon: a system for neutralization of low extracellular pH. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2659–2669. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2659-2669.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for the predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishimura A, Morita M, Sugino Y. A rapid and highly efficient method for preparation of competent Escherichia coli cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6169. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh B-K, Apirion D. 10Sa RNA, a small stable RNA of Escherichia coli, is functional. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:56–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00264212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson E R. Influence of pH on bacterial gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park Y K, Bearson B, Bang S H, Ban I S, Foster J W. Internal pH crisis, lysine decarboxylase and the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:605–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5441070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedersen S, Reeh S, Friesen J D. Functional mRNA half lives in E. coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;166:329–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00267626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reese M G, Eeckman F H. Proceedings of the Seventh International Genome Sequencing and Analysis Conference 1995. 1995. New neural network algorithms for improved eukaryotic promoter site recognition; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg M, Court D. Regulatory sequences involved in the promotion and termination of RNA transcription. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:319–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salmond C V, Kroll R G, Booth I R. The effect of food preservatives on pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2845–2850. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharp P M, Li W H. The codon adaptation index: a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1281–1295. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solovyev V V, Slamov A, Lowrence C B. Predicting internal exons by oligonucleotide composition and discriminant analysis of spliceable open reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5156–5163. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.24.5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stim K P, Bennett G N. Nucleotide sequence of the adi gene, which encodes the biodegradative acid-induced arginine decarboxylase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1221–1234. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1221-1234.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stim-Herndon K P, Flore T M, Bennett G N. Molecular characterization of adiY, a regulatory gene, which affects expression of the biodegradative acid-induced arginine decarboxylase gene (adiA) of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1311–1320. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stock J B, Ninfa A J, Stock A M. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subbarao M N, Apirion D. A precursor for small stable RNA (10Sa RNA) of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:499–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02464923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tinoko I, Jr, Borer P N, Dengler B, Levine M D, Uhlenbeck O C, Gothers D M, Gralla J. Improved estimation of secondary structure in ribonucleic acids. Nature. 1973;246:40–41. doi: 10.1038/newbio246040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.VanBogelen R A, Olson E R, Wanner B L, Neidhardt F C. Global analysis of proteins synthesized during phosphorus restriction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4344–4366. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4344-4366.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waldburger C D, Sauer R T. Signal detection by the PhoQ sensor-transmitter. J Biol Chem. 1997;271:26630–26636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker G C. Mutagenesis and inducible responses to DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1984;48:60–93. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.1.60-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wanner B L. Phosphorus assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1357–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wanner B L, Chang B D. The phoBR operon in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5569–5574. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5569-5574.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wanner B L, Mcsharry R. Phosphate-controlled gene expression in Escherichia coli K12 using Mu dI-directed lacZ fusions. J Mol Biol. 1982;158:347–363. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wanner B L. Signal transduction and cross regulation in the Escherichia coli phosphate regulon by PhoR, CreC and acetyl phosphate. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Watson N, Dunyak D S, Rosey E L, Slonzcewski J L, Olson E R. Identification of elements involved in transcriptional regulation of the Escherichia coli cad operon by external pH. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:530–540. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.530-540.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamada M, Makino K, Amemura M, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Analysis of mutant phoB and phoR genes causing different phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5601–5616. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5601-5606.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamada M, Makino K, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli: properties of phoR deletion mutants and subcellular localization of PhoR protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220:366–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00391740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]