Abstract

The aim of this article is to analyse the dysfunctionalities of Polish democracy that has seen the stability of the power-opposition system disturbed; and society left suffering under the totality of political polarisation. Considering the fact that within a polarised society only one solution can be the leading one, the society and the state, both internally and externally, have become extremely divided, which has not only impacted Polish society’s image of itself, but also Poland’s standing and relations on the international stage. The observed phenomena can be traced to multiple events that started years before Poland became beset by a crisis of democracy.

This article will analyse political and legal changes in Poland within the democratic frames, which no longer fulfil the previously assigned tasks. It will also make a connection between affective political polarisation and dysfunctions of democracy that might lead to a worsening of the stability of the democratic system. Finally, it will show the consequences of the country’s dysfunctionality on both national and international stages.

Keywords: Political polarisation, Dysfunctional democracy, Illiberal democracy, Democracy backsliding, Rule of law, Right-wing parties

Abstract

Ziel dieses Artikels ist es, die Dysfunktionalität der polnischen Demokratie zu analysieren, was dazu geführt hat, dass die Stabilität des Systems von Regierung und Opposition gefährdet ist und die Gesellschaft unter der Totalität der politischen Polarisierung leidet. In Anbetracht der Tatsache, dass in einer polarisierten Gesellschaft gemäß offiziellem Narrativ nur ein Lösungsansatz Gültigkeitsanspruch hat, sind die Gesellschaft und der Staat sowohl intern als auch extern extrem gespalten. Dies wirkt sich nicht nur auf das Selbstbild der polnischen Gesellschaft, sondern auch auf das Ansehen und die Beziehungen Polens auf internationaler Ebene aus. Die beobachteten Phänomene lassen sich auf mehrere Ereignisse zurückführen, die bereits Jahre vor der Krise der Demokratie in Polen ihren Anfang genommen haben.

In diesem Artikel werden die politischen und rechtlichen Veränderungen in Polen innerhalb des demokratischen Rahmens analysiert, der die ihm zugeordneten Aufgaben nicht mehr erfüllt. Weiters wird in diesem Beitrag eine Verbindung zwischen affektiver politischer Polarisierung und Dysfunktionen der Demokratie hergestellt, die zu einer Verschlechterung der Stabilität des demokratischen Systems führen können. Schließlich werden die Folgen der Dysfunktionalität Polens sowohl auf nationaler als auch auf internationaler Ebene aufgezeigt.

Schlüsselwörter: Politische Polarisierung, Dysfunktionale Demokratie, Illiberale Demokratie, Gefährdung der Demokratie, Rechtsstaatlichkeit, Rechte Parteien

Introduction

The number of articles and research works on democracy backsliding has increased significantly in recent years (e.g. Giovannini and Wood 2022; Casal Bértoa and Rama 2020; Przeworski 2019). We can see the first research results linking the democratic crisis with a rise in anti-establishment or radical populist parties (Casal Bértoa and Rama 2020; Giebler and Werner 2020), weak economies and high income inequality (Dalio et al. 2017; Funke et al. 2016) or an opposition to imposed cultural changes (Inglehart and Norris 2016). Much of this research has also suggested that the aforementioned phenomena is causing strong political polarisation, which ends up undermining democratic stability even further. On the one hand, we can observe the ideological polarisation and building of “ideological silos” on both the left and right of the political spectrum (Pew Research Centre 2014). On the other, there has also been an affective polarisation, with a rising tendency among party supporters to view (an)other party/parties as (a) disliked ‘out-group(s)’, while holding positive in-group feelings for one’s own party (Reiljan 2020, p. 377). The radicalization of the political scene does not fully explain this phenomenon, as political polarisation in contemporary Europe affects not only the political and institutional spheres but also the social one; with “broken” communication lines between political players and society. This ultimately leads to a decrease in political trust among the supporters of the party that has actually won the election, the emergence of harsh rhetoric between party elites and the inducing of discriminatory outlooks in other sections of society (Reiljan 2020, p. 381). Ideological conflict, usually associated with party sympathies, has deepened by way of a psychological winner-take-all logic and an us-versus-them discourse (Vegetti 2019, p. 79). What is more, it undermines social cohesion, which within the democratic system takes into consideration not only institutional aspects such as the rule of law and the separation of powers, but also the equal participation of social minorities and sociopolitical inclusion (Küpper and Váradi 2021). The definition of political polarisation from Emilia Palonen allows us to appreciate these considerations in a holistic way:

(…) polarisation is a political tool—articulated to demarcate frontiers between “us” and “them” and to stake out communities perceived as moral orders. Polarisation is a situation in which two groups create each other through demarcation of the frontier between them. The dominant political frontier creates a point of identification and confrontation in the political system, where consensus is found only within the political camps themselves. Polarisation is reproduced in all political and social contexts with an intensity that distinguishes it from mere two-party politics. It is a totalising system, as it aims to dominate the existing systems of differences and identities. (Palonen 2009, p. 321)

The data shows that, on average, the level of electoral polarisation in Europe since the end of the Second World War (WWII), has never been so high (Casal Bértoa 2019). Therefore, it is crucial to look at whether and how polarisation is related to democratic trends in contemporary Europe. According to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) 2021 report on the global state of democracy, more countries are moving in an authoritarian than in a democratic direction (International IDEA 2021, p. 3). However, especially in Europe, there is a question as to whether the institutional and systemic changes occurring in Europe are truly leading countries towards authoritarianism, or rather, they are influencing our perception of democracy, which is starting to change. Even though many researchers point out that democracy in Europe has been adversely affected, we have not yet seen it collapse, even in highly polarised democratic societies (Casal Bértoa and Rama 2020). Recent years have shown that liberal democracy is not, in contrary to popular belief, the ultimate form of governance (Mounk 2020). Even if Fukuyama’s “end of history” theory became the subject of harsh criticism, the idea behind liberal democracy as a “certain state” was still working for the majority of European states (Przeworski et al. 1996, p. 48). However, the occurring changes in European democracy are forcing us to look at it from a converse position, focusing on how it can further transform and where are the limits of these new democratic systems. Even though Robert Dahl in his acclaimed book On Democracy points out, that “democracy” refers to both an ideal and an actuality (Dahl 2015, p. 26), he still listed the criteria necessary to speak of a democratic process: effective participation, voting equality, enlightened understanding of the political agenda, as well as an opportunity to change the same; and finally inclusion by exercising the right of citizens to participate in the political process (Dahl 2015, p. 37–38). His view was focused on the core element of democratic theory, which is ‘representation and participation’. Currently, when observing international reports on democracy backsliding, the focus lies primarily on democratic norms and institutional changes such as the undermining of rule-of-law standards or a weakening the separation of powers (Hartmann and Thiery 2022). Therefore, some of the changes linked to the democracy crises (polarisation, populism, and globalization) might be difficult to place when predicting the development of a contemporary European system of values. Even if most European countries still have democratically functioning institutions, they do not seem to correspond adequately to the new sociopolitical reality and therefore are producing unintended or undesirable outcomes. Dysfunctional democracy is a term, which focuses on the contemporary changes in democratic regimes, without imposing a solely institutional or legal approach, describing as it does a democratic system that fails to adapt adequately to the demands of a changing landscape (Pickel et al. 2022). In opposition to functional democracies, dysfunctional democracy cannot absorb new sociopolitical demands and transform them adequately into a workable political reality. This leads to an undermining of basic democratic principles; and the democratic system can no longer react to challenges with predictable outcomes.

The phenomena of political polarisation seems to enhance the dysfunctionality of democracies. Research proving that the instrumental use of polarisation as a political tool threatens democratic norms and governance in very diverse democracies around the world (see: McCoy et al. 2018). As dysfunctional democracies are not necessarily weak in terms of their institutional structure, they show deficiencies in the spheres of political will-forming and decision-making process and present the inoperative relationships between the political system and the intra- and extra-societal environment (Pickel et al. 2022). This corresponds to a polarising “camp-mentality”, which weakens independent (of party-political interest) public engagement and has a disinformational effect (Körösényi 2013, p. 20), which affects both individual citizens as well as public political figures. Therefore, a political decision made in a context of political polarisation may not produce the intended outcomes, as it does not consider all of the factors but rather focuses on political goals within the very strict frames of one’s own ideological boundaries. The occurring societal and global changes require constant adaptation, which is hard to achieve within a polarised society. Democratic resilience is the ability of a political regime to recover from, or adjust to changes, react to challenges and withstand them and still function, without losing its democratic character (Merkel and Lührmann 2021, p. 872). Polarised societies reject changes outside of the predestined political camps, which are clearly distinct regardless of the distance between them, their size, or their levels of internal cohesion (Bramson et al. 2017, p. 125). Therefore political polarisation favours democratic dysfunctionality as it does not allow for the assessment and prediction of outcomes arising from a political decision.

One of the countries whose democratic credentials have been questioned in recent years is Poland, with its adherence to legal norms disputed at national (Witkowski 2021; Sadurski 2019; Szuleka 2018; Dobrowolski 2017; Ossowski 2015) and international (European Parliament 2022; Council of Europe 2017) levels. There has been a commensurate rise in Polish literature regarding political polarisation, linking it to a weakening of democratic standards in the country (See: Górska 2019; Ruszkowski et al. 2020; Wielgosz 2020).

In this article, the phenomena of political polarisation and dysfunctional democracy will be subjected to a critical and systemic analysis based on empirical evidence pertaining to the political, legal and cultural changes, which have a significant impact on restructuring the shape of democracy in Poland. To this end, we will be looking at deviations from the previously established national and international legal frames; as well as the specificity of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. This analysis will answer the following questions:

What are the institutional and sociopolitical causes of the changes which have taken hold in Polish democracy?

How does the process of political polarisation correspond to the dysfunctionality of Polish democracy?

What are the real effects of the process of political polarisation in the structures of a democratic state (the case of Poland)?

Where lies the future of Polish democracy with its current political course?

Polish democracy and polarisation of the society

The collapse of the Iron Curtain and ending the Cold War was one of the high points in the history of twentieth century Europe. It was followed by revolutionary disintegration of states and the emergence of new ones as well as systemic transformations. The dissolution of the Soviet Union was accompanied in Europe by unipolar peace-making, the supremacy of liberal capitalism and the emergence of national identity as high politics (Clark 2014, p. 515). For the Post-Soviet and Post-Satellite states, it also meant a complete systemic transformation, in which it was necessary to somehow refer to the “legacy” of the previous decades. Thus, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe had to take into account the function of social, cultural and institutional (formal) structures created under the previous regime (Rafałowski 2014, p. 29). One of those countries was Poland, whose Round Table Talks in 19891 represented the hallmark of a systemic transition; one that does not entirely reject the previous order, but tries to build a new one within its frames. This kick-started what would be a long and complicated process of transformation; whereas it was followed immediately by a consolidation of the country’s democratic system (although the first truly free elections according to the contemporary democratic standards took place in 1991). Fundamental problems included decisions on the pace of introducing market economy mechanisms, the scope of social security measures, decisions on the formation of the governmental system and electoral law; and social solutions on how to deal with the “burden of history” and the presence of post-communist parties in the Polish political scene (Rafałowski 2014; Wiatr 2006). This democratization process, although always remaining incomplete and perpetually running the risk of reversal (Tilly 2007), seemed to point for Poland and many other Central and Eastern Europe Countries (CEEC) towards a consolidated democracy. In the studies from 2002 on authoritarian regimes and defective and liberal democracies, Estonia, Lithuania, Slovak Republic, Czech Republic, Slovenia and finally Hungary and Poland were categorized altogether as liberal democracies, stating that the transitional changes that had happened at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s did not damage the democratic aspirations of these countries (Merkel 2004, p. 51). Polish democracy proved more stable, compared to other transition countries (Jarosz 2005, p. 331). The country, of course, encountered problems typical for Post-Satellite states, related to the high scale of corruption in the country, the unofficial political connections of interest groups or lobbyists influencing the country’s policy outside the legislative process; and low political turnout (Gilejko 2012, p. 68). However, the observed changes, especially in the early 2000s in Poland and Europe proved that we could discuss the arrival of a new wave of liberal democracies. As Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2006 showed, all of the listed above CEEC countries managed to maintain their Democracy Status over the 9.2 index on the 10-point scale within the “Democracies in Consolidation” category (Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2020). Poland was the leader in categories such as the Stability of the Democratic Institutions, Rule of Law or Political Participation with an almost 10/10 score for the latter. The lowest rating was given to the party system which at that time was still dominated by the Democratic Left Alliance (Pol. Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD), strongly connected with the former communist party, and the newly created (2001) Law and Justice (Pol. Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) and Civic Platform (Pol. Platforma Obywatelska, PO), both of which were an amalgam of centre and right-wing policies2. The democratic transformation however, would be strengthened by Poland’s accession to the European Union. As Klaus Ziemer notes, the years 1999 to 2008 saw Poland as a Europhilia state by which the belief in Europeanization and Democratic values was the most prominent (Ziemer 2020, p. 252). By\2016, Poland reached the rating of 9.5 of Democracy Status with the outstanding 10/10 result when it came to the Stability of Democratic Institutions. Similar results could be found in the Freedom House Index research results, where Poland was assigned to a “consolidated democracy” category with 80/100 Democracy Percentage within the Nations in Transit Index (Freedom House 2015).

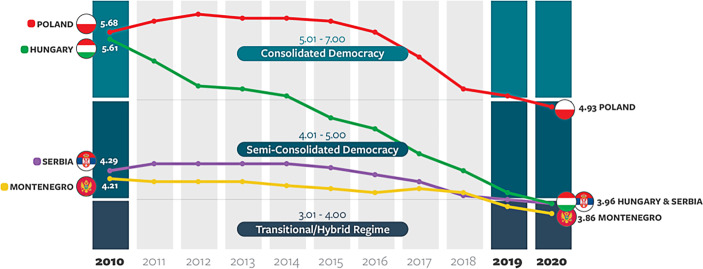

It came as an initial surprise when a “consolidated democracy” like Poland, with stable democratic institutions, started to lose high scores in the international democracy ratings and had somehow embarked on another transition. The first moments of these changes were hard to connect to the economic crisis, which is often associated with the weakening of democracy (Morlino and Quaranta 2016). In fact, Poland avoided the 2007–2009 recession (Drozdowicz-Bieć 2011) and noted constant growth of GDP per capita. By 2015, the parliamentary system was well established, the preference for democracy was still high, and Centre for Public Opinion Research (pol. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, CBOS) had recorded the highest percentage of respondents in the history of research, who declared satisfaction with their health, education, income and financial situation, material living conditions and future prospects (CBOS 2015). Yet in 2015, a major democratic shift took place, and the stability of the Polish democracy began to be questioned at the international level. In just 4 years, starting from 2015, Bretelsmann Transformation Index dropped to 8.0 score and the most prominent democracy categories “Stability in the Democratic Institutions” and “Rule of Law” noted a major decrease in rating (Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2020). The Freedom House index changed Poland’s rating to a Semi-Consolidated democracy, making it the second EU member state after Hungary, to lose its full democratic status (Freedom House 2021) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Freedom House: index of democracy score for Poland, Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro between years 2010 and 2020. Poland: from 5.68 to 4.93; Hungary: from 5.61 to 3.96; Serbia: from 4.29 to 3.96; Montenegro: from 4.21 to 3.86. (Source: Tilles 2020b)

The transformation, which began in 2015, gave rise to many questions regarding the course of changes taking place in the country. At one point consolidated, democratic institutions started to produce various unexpected outcomes. The question was whether it was the new and purposeful political course of the country; or was it rather an unintended consequence of the newly introduced policies. In 2015, the populist Law and Justice Party (PiS) won parliamentary elections and not only secured a parliamentary majority, but also managed to fill the position of the president, who holds an important role in the legislative process in Poland. Immediately PiS started the process of far-reaching legal changes in the country, which not only began re-shaping the country’s political traditions but also provoked a strong reaction from the opposition (more on this later in the article). It was the first time in the history of modern Poland that one party had taken sole responsibility for the country’s future. Because there is a proportional representation (PR) system in Polish electoral law, it usually forces a coalition of several parties to rule (art. 96 of The Constitution of the Republic of Poland 1997). Such a huge electoral advantage of one party created the new division between governing PiS and the opposing parties, one that shifted public attention to the issue of party polarisation, which quickly became a new media topic (Dempsey 2016; Forsal.PL 2016). As mentioned previously, political polarisation can be understood both as a very specific term and as a multidimensional phenomenon. We can focus only on the ideological frame and describe polarisation as political support for extreme views in the country, sometimes with a commensurate decline in centrist viewpoints. However, we can also look at this from a wider perspective. In the Polish case, polarising conflict might have started to be publicly visible at a party level, but it was anchored in years of gathering social conflict. In Poland, we can distinguish different class-layers; and they transfer to alternative systems of values and norms (Ruszkowski et al. 2020, p. 173). As some of them were constantly omitted in the political programs of the previous governments, the newly introduced aggressive conservative changes in the social system were initially met with widespread public support. However, the clash between existing groups that were resistant to change, ultimately led to dysfunctionalities of the social sphere. Since the well-established interests of the liberal-minded section of the country had been marginalised, the political polarisation took an even harsher turn (Ruszkowski et al. 2020, p. 174). Nowadays we can notice that not only the political scene, but also Polish society is strongly polarised. It is worth emphasizing that currently in Poland there is also a public belief in a strong political polarisation between people. Research shows that both the governing party and opposition supporters, predict negative feelings towards political opponents, on the basis of the belief that political opponents do not like or dehumanise the group to which the respondent belongs (Górska 2019, p. 2). This creates an even greater problem for social dialogue, as reluctance does not come from any objective premises, but rather from a conviction about negative assessment from the outside group. Besides the political creation of the extreme views platform, Poland suffers from the breakdown in the social and political dialogue and impoverishment of the public debate, which prevents consensus beyond one’s own group or political camp.

Analysing Polish recent history, with national and international scandals regarding the judicial system, the freedom of the media, freedom of expression; and frictions with the European Union, it is crucial to understand how those changes started to occur and how they led to such strong levels of polarisation in the country. It is important not only to be able to link newly emerged dysfunctionalities to the specific events, but also to better understand significant consequences for the internal and external stability of the country. Current Polish politics challenges democratic values, limits freedom of speech, and radicalises political and societal relations. Over thirty years after the transition, there is an observed problem with Polish democracy that has produced unexpected outcomes, even if the majority of institutions still operate on a democratic basis. What is happening in Poland has had a major impact on the rest of European democratic states and the stability of the European Union. The Polish transition has yet to be completed but there is still a question whether Poland will emerge from it as a democratic state.

The roots of dysfunctionalities

When we look at the common law system in many democracies, the basic functionality can be summed up by the maxim: “everything which is not forbidden is allowed”. Of course, this links with the assumption that freedom of action, as long as it does not harm the others, is one of the roots of the democratic state. There, where a government is accountable to their people and acts according to law, the democratic freedom can be achieved in many ways. Individual citizens might come up with an unexpected idea and be allowed to pursue the same as long as the law does not prevent them from doing so. However, what about the government? Should actions based on searching for legal loopholes be the foundation of official state activity? At the beginning of 2015, the scope of permitted activity of state authorities started to be the focal point of many Polish studies.

2015 in Poland was primarily an election year with both parliamentary and presidential elections. What is more, in 2015 Poland had also a nationwide referendum—the first one since 20033. The first half of the year focused on the presidential elections, which ended after the second round with a victory for Andrzej Duda (51.55%), who defeated the incumbent president Bronisław Komorowski (48.45%) (National Electoral Commission 2015b). It came as quite a surprise, especially since the incumbent president, Komorowski, up until beginning of 2015, had been enjoying very high approval ratings. However, an intense campaign on the part of his opponents exposed the very limited campaign of the incumbent and a series of media mishaps led to what was an unexpected outcome.

Andrzej Duda’s electoral committee had been supported by PiS, which by winning the presidential elections enjoyed a surge heading into the parliamentary elections, scheduled to take place October 25, 2015. In the meantime, on September 6, 2015 Poles had to attend the polls yet again with a nationwide referendum. It concerned the single-member constituencies in the Sejm (the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland), the financing of political parties from the state budget and the interpretation of the principles of tax law. As a result of a poorly conducted referendum campaign, coupled with the short time interval from the presidential elections, and a detachment on the part of society to the questions being posed, the referendum failed, obtaining only a 7.8% turnout (National Electoral Commission 2015a). Finally, in October Poland had its final parliamentary elections of 2015, which ended with the victory of PiS. It was the first time since 1989, that the victorious election committee won a parliamentary majority to form an independent government. Given the fact that a PiS candidate had also won the presidential elections, the party gained complete power to govern. Of course, this turnout was not all a surprise. Polish society was tired of the long governance of the centrist PO party, its internal warring, combined with the 2014 scandal which saw the leak of expletive-ridden recordings of private conversations between top politicians in Warsaw (Lyman 2014). The recording revealed PO politicians making disparaging jokes about Polish society, while eating in pricey restaurants, which resulted in widespread evaluation of the party as being an “alienated establishment” (Jażdżewski 2015). PO’s policies at that time prized liberal and European values, which for the poorer and more conservative part of society did not constitute an attractive vision for the future. On the other hand, PiS presenting a program aimed at those, who, though perhaps less well-off, represented the very core of the country in terms of their values and traditions. Their election program was led by three major slogans: “health”, “work” and “family” (PiS 2014); and they focused not only on the cities but also on the countryside where the majority of Poles had felt overlooked by the ruling PO government.

The Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) in their Election Assessment Mission Report stated that the Polish Parliamentary Elections 2015 “(…) were competitive and pluralistic, conducted with a respect for the fundamental principles of democratic elections in an atmosphere of freedom to campaign and on the basis of the equal and fair treatment of contestants” (ODIHR 2016, p. 3). Even if the final two weeks of the campaign were dominated by the European emigration crisis that divided political parties, still the discussion around the subject was not clearly polarising or aggressive. In this way, in a legitimate and constitutional manner, a right-wing national-conservative political party won and started the process of changes in the country. The new ruling party chose to form a government with new faces at the helm (e.g. the appointment of Beata Szydło a Prime Minister) whilst keeping the most influential party member—Jarosław Kaczyński—as merely a member of the parliament. It was certainly a turning point for Polish society. However, the events that took place in the following months and years revealed not only the different political sympathies of Poles; but that Polish society was much more polarised than had previously been assumed. In this new reality, some Poles have found their voice again. What is more, in the years that followed, a number of loopholes that existed in the Polish legal system were exploited, which led to further threat to the stability of Polish democracy.

The dispute over the constitutional tribunal

It is only natural that with such a massive power shift in the country, Polish citizens expected a new round of reforms. Poland has a semi-presidential system, where a popularly elected fixed-term president exists alongside a prime minister and cabinet who are responsible to parliament (Sydorchuk 2014, p. 119). The condition for the entry into force of any act passed by the Polish Sejm or Parliament is for it to be signed by the President (art. 122 of The Constitution of the Republic of Poland). Therefore, in most cases, the positive conclusion of a given legislative process, must met with the President’s acceptance. In the past, when the President was a representative of the oppositional party, the right to refuse to sign the bill was often used. For this reason, each legislative process required agreement, and also with the parliamentary opposition. With a PiS parliamentary majority of 2015 and the party’s president Andrzej Duda, these limitations had been effectively done away with.

The new government quickly embarked on an ambitious plan for institutional and constitutional reforms. The first one, the consequences of which are still being felt today, originated from the misuse of power of the previous ruling party—PO. The origin of the dispute goes back to June 2015, when the ruling coalition of the PO-PSL party passed a new act on the Constitutional Tribunal and authorised the Sejm to fill 5 judicial posts in this institution. 3 of them were to be released before the end of the term of this Sejm (6 November 2015), and 2 after the elections (HFHR 2017, p. 17). The Sejm, despite the protests of PiS against the filling of two additional seats, adopted a resolution on the election of all five judges of the Constitutional Tribunal. It, of course, sparked an objection and resulted in an appeal by a grouping of PiS deputies, who were disapproving of election of 2 judges—the ones that were supposed to have been elected after the parliamentary elections (the sitting judges were to be released in December 2015) (Constitutional Tribunal 2015). However, after the elections, the winning party did something unexpected. Not only did the aforementioned group of deputies withdraw their appeal from the Constitutional Tribunal but the newly elected Sejm adopted a resolution stating the “lack of legal force” of the election of all five judges. Therefore, not only the two mentioned judges were to be appointed once more, but all five; even those whose were to be filled before the elections by the previous Sejm. Despite the stormy protests, all five of the new judges were sworn in by the President of the Republic of Poland on the night of December 2/3, immediately giving no place to further discuss what had been a controversial legal matter.

It was not only what happened that provoked outrage in the country but also the mode in which it had come about. The express mode of proceedings and night deliberations indicated a strategy not to allow time, or the possibility, for either party to intervene or change its mind. This one act resulted in a series of constitutional consequences risking the stability and integrity of one of the most prominent judicial institutions. The question of legitimacy of the judgments issued with the participation of newly elected judges undermined confidence in the entire judicial process. What is more, because the Constitutional Tribunal is the very institution that controls the compliance of lower-order legal norms (statutory or sub-statutory) with higher-order legal norms, primarily with the Constitution and some international agreements, it raised doubts about the legitimacy of any future law passed by the eighth term Sejm. The issue of the legality of decisions made by both parties would become the subject of many debates.

It is worth noting that it was not only the legal dispute over the Tribunal which heavily influenced the stability of Polish democracy. It was the entanglement of society and PiS indicating early on that it be the only grouping that makes decisions. The dispute over the Constitutional Tribunal very firmly placed citizens on both sides of the barricades. The case of PiS managing (although it still remains an unsettled issue) to keep five newly elected judges in the Constitutional Tribunal, did not change the fact that a part of society was irreversibly discouraged from any decisions made by them. Research showed that this dispute contributed to both legal uncertainty in the country and a belief, shared by swathes of the society, that PiS had violated the standards of democracy (Maliszewski and Wysocki 2016).

As already mentioned, the origin of this issue had not actually been caused by PiS, but by PO’s unlawful decision. However, the revenge path chosen by the new government made fractious relations between PiS and the opposition for years to come. The first signs of an upcoming crisis emerged with the creation of the Committee for the Defense of Democracy (Pol. Komitet Obrony Demokracji—KOD)—a citizens’ initiative to form a non-party opposition. They began to organise a series of protests in the country, with attendance at one march as high as 50,000 (BBC 2015) an event unseen in previous years. Of course, the protests and strikes had occurred in Poland before, but usually they were not aimed at opposing the entire ruling party, but rather the specific legal solution.

This however did not stop the ruling party from continuing with their reforms of the legal justice system. On December 22, 2015, the Sejm passed a law that implemented significant changes to the functioning of the Constitutional Tribunal (Sejm 2015). Almost all of the bill’s paragraphs strengthened the position of the newly elected ‘controversial’ five judges. One of the articles stated that the Constitutional Tribunal could only pass verdicts with a two-thirds majority and with at least 13 out of 15 judges present. This significantly increased the position of the newly elected judges, making it impossible to treat them as a minority during the ruling. The approved act did not have vacatio legis, which meant that changes would take effect immediately, upon publication in the Journal of Laws. This all happened despite the many objections formulated by the most prominent Polish judicial institutions, inter alia, the National Council of the Judiciary or The Supreme Bar Council. Passing this law immediately produced a number of unexpected events and consequences that further undermined the position of the Constitutional Tribunal. Academic experts pointed out that not only was the act unconstitutional in its entirety, but it had created a loophole where the Tribunal could adjudicate directly on a Constitutional basis disregarding the Amendment Act from 22 December 2015 (Faculty of Law and Administration, University of Silesia in Katowice 2016). Consequently, the following year, on March 9, 2016, the Tribunal, composed of 12 judges, issued the judgement that the Act of 22 December 2015 had been entirely inconsistent with the Constitution. Of course, due to the contents of the judgement, the previously introduced requirement for the presence of 13 judges was dropped. However, this ruling was never published. The Prime Minister Beata Szydło announced that in her opinion, any adjudication ignoring the provisions of the new act was a violation in itself. By this, she distorted the publication process, which in turn created a rupture in the legal system (Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights HFHR 2017). One can easily imagine how this added another, even more political, layer to the dispute, which effectively weakened the Polish judicial system. Immediately, this led to a further division within the political space; and in Polish society. Again, different sides of the conflict presented their expertise, accusing the other party of proceeding in an illegal manner. In the following years, the conflict over each major judgement of the Tribunal worsened. This led to further disagreements, such as the conflict over the legal dualism of the judgements, a dispute over the president of the Constitutional Tribunal; and the boycott of the work of the Tribunal by judges (Szuleka et al. 2016). Only one thing remained unchanged—a consistent undermining of the position of the Constitutional Tribunal in Poland.

While most of the Polish legal and academic circles, NGOs and human rights organizations opposed the subsequent changes in the Polish judicial system, the relocation of the conflict to the international arena was inevitable. On July 7, 2016, the European Commission issued a recommendation regarding the legally questionable processes at the Polish Tribunal (European Commission 2016). On December 20, 2017, the Commission concluded that there is “a clear risk of a serious breach of the rule of law in Poland” (European Commission 2017). It made a proposal to the European Council to adopt a decision under Article 7 (1) of the Treaty on European Union to protect the rule of law in Europe. It was the first such significant indication that the dispute over the Constitutional Tribunal was not merely a legal dispute. The shape of this problem turned into an international controversy about permissible deviations from the rule of law. Polish society would soon cease to recognise the difference between a political game and a legal discussion. The problem quickly shifted from the Constitutional Tribunal to the Polish Supreme Court, compromising the legal system of the country. To date, the Court of Justice of the European Union has already (status on July 27, 2021) ruled three times on the breach or violation of the rule of law in Poland at the request of the European Commission. As a response, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal decided that the application of interim measures in cases concerning the Polish court system imposed by the CJEU is inconsistent with the Polish constitution (European Commission 2021). Therefore, Poland does not intend to follow the CJEU recommendations.

The current rupture in the Polish tripartite separation of power is more than obvious. However, this serious dysfunction did not result directly from open opposition to the law, but rather from mixing the politics with the legal system of the country. Politicians who spoke about the Constitutional Tribunal crisis created a “political trap” further dividing Polish society. Internally this led to a much more dangerous polarisation of Polish society, which quickly became visible in the public space and, above all, in the media. Externally, it worsened Poland’s position in the international arena and started to build a Polish opposition against the rulings of the European Union. It would be unfair to conclude that the source of this dispute was a straightforward breach of the law. Legal conflicts occur regularly in democratic countries and do not necessarily weaken the entire system. However, in Poland, the legal truth in this dispute ceased to be relevant at the very beginning and became a social dispute. As the conflict deepened, the social division also worsened. This transformed the electoral divide, and led to a polarisation not witnessed since 1989.

The media crisis

When discussing democracy in the 21st century, it is hard not to mention the role of the free media. Of course, their character differs depending on the type of democratic system under consideration. The media can be perceived as watchdogs with a goal to identify and make public the wrongdoings of elected representatives; or as a transmitter with an obligation to inform the public about potentially crucial issues and engage them in the discussion (Trappel and Tomaz 2021, p. 13–14). Because of their strong position as the fourth estate, they can be both a support and a threat. Hyper-commercialism, media concentration, and the declining diversity of news can easily undermine the right to a democratic and diverse communication that takes place between a government and the public (Trappel and Tomaz 2021, p. 11). In recent years, the Polish media has undergone a dramatic transformation. From a relatively diverse platform, the Polish media began to also experience polarisation. It is not unheard of for media publishers to be seen as biased, and looking to propagate either liberal or conservative views. This corresponds to the distributions of views in society. The problem occurs when the media not only shifts towards certain sympathies but becomes the open advocates of specific ideologies and viewpoints. In the case of Poland, the matter is even more serious, as it concerns the public broadcaster.

Shortly after winning the 2015 parliamentary elections, PiS proposed an amendment called the “Small Media Act” aimed at regulating the provisions of the National Broadcasting Council (Pol. Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji—KRRiT). It imposed, among others, the expiry of the mandates of the current members of management boards and supervisory boards of Telewizja Polska TVP and Polish Radio (main Polish public television and radio broadcasters). The reason for introducing such a regulation were the accusations that the current management board was restricting access to freedom of speech for all citizens equally (TVN 24 2015). It was rather clear that this regulation was aimed at planting government-friendly officials within this institution. Although controversial, these kinds of practices occurred also during the rules of previous governments. The new chairman of the Polish public broadcaster was Jacek Kurski, a former politician of the PiS party. Soon public television audiences understood that the newly formed public broadcaster was being more than favourable to the ruling party. This was especially in evidence with the daily evening news (Pol. Wiadomości) which started to present domestic and international events in tune with the government’s views, including coverages regarding public protests, actions of the opposition or news regarding the European Union.

Years 2016–2021 in Poland were filled with massive public protests against many new changes implemented by the government. Implemented by PiS changes to the abortion law in Poland sparked in late 2016 a nationwide movement called the “black protest” where women wore black clothes at protest marches to show their opposition to the anti-abortion restrictions. The demonstration from October 3, 2016 saw the gathering of as many as one hundred thousand people. However, the public broadcaster, in the media coverage, lowered the numbers of protesters and highlighted the opposing protest which had been significantly smaller (Chapman 2017, p. 11).

Journalists did not shy away from making biased assessments of many political events. When Donald Tusk, Poland’s former prime minister from the PO party, was reappointment as a president of the European Council, in TVP’s evening news, he was presented as a candidate pushed through by European “elites,” with Germany at the helm (Chapman 2017, p. 13). The fact that the Polish government had attempted to block the renewal of Tusk’s mandate, coincided with a negative assessment of the public broadcaster. However, a true threat to the “free media” in Poland came with the Sejm’s proposal from December 14, 2016 to restrict access to the parliament to only selected journalists. These changes were to include, among others, limitations on recording and photographing of reports on the sessions of the Sejm and a prohibition of recording parliamentarians before or after the session. What is more, only one place in the Sejm building was to be created for television stations to broadcast live; or record for later broadcast (a place which journalists would have to reserve) (Chancellery of the Sejm 2016). As a reaction to this proposal, some national media (including the main opposition broadcaster TVN) introduced a boycott of PiS’s politicians by not conducting interviews with them. Two days later, Michał Szczerba, MP from the PO’s opposition party, was excluded from the Sejm’s parliamentary session because he had come out on the rostrum with a piece of paper with the hashtag Free Media in the Sejm (Pol. #WolneMediawSejmie). In reaction to this event, a group of parliamentarians from PO and Nowoczesna opposition parties blocked the Sejm’s rostrum. On the same day, KOD organised a demonstration in front of the Sejm building complex, which quickly led to massive protests in the major cities of Poland. Jarosław Kaczyński, the PiS leader, assessed the actions of the opposition as “an attempted coup” (BBC 2016). Ultimately, the changes proposed by the Sejm were not introduced.

The crisis of free and impartial media in Poland, however, did not concern only the public broadcaster. The radicalization and bias in public media has also radicalised other representatives of the “fourth estate”. It led to impartiality and worsening quality of media coverage in the country. The main media broadcasters: TVP (public) and TVN (private, oppositional) started to make recourse to polarising language, often using the statements bearing the hallmarks of hate speech. It was mainly visible during the times of increased media activity, such as the parliamentary or presidential elections in 2019 and 2020. The pluralism of the available broadcasters did not transfer into the objectivity of the provided information. ODIHR ran an election observation mission and monitored prime-time content on five Polish TV stations from September 18 to October 11, 2019 (ODIHR 2020b). Their finding showed that, contrary to the law, the information services of the public broadcaster had failed to provide an adequate platform to opposition candidates. The station’s journalists described the opposition candidates as “pathetic”, “incompetent” or “lying”. The private media showed less partiality, although they also made critical statements, this time, directed at the government and the ruling party (Horonziak 2021). With a clear media division between government supporters and opposition, it was hard to find unbiased coverage. This polarisation of the media also motivated the ruling party to engage in more attempts at limiting freedom of speech. As the main oppositional broadcaster, TVN is a part of the foreign Discovery group. A group of PiS deputies submitted a bill proposal that would have limited the granting of concessions to any media owned by foreign capital, with PiS politician Marek Suski stating that Poland must be protected from hostile entities. Given the fact that the main percentage of TVN’s capital belongs to the United States, this project not only threatened TVN with the loss of its license but also undermined international relations between Poland and the United States. Ultimately TVN was forced to obtain a European, Dutch broadcasting license. Eventually, the Polish National Broadcasting Council licensed the station after a record 19-month long waiting time (TVN 24 2021).

There is no doubt that Polish democracy has suffered from the constant lowering of media standards. A Reporters without Borders report has stated that although the private market in Poland has remained fairly pluralistic, the public media, especially TVP, has been transformed into instruments of government propaganda (Reporters without Borders 2022). Even if there is a wide range of media providers, the fact is the public broadcaster, financed by the state, has become a propaganda instrument for the ruling party, undermining the very notion of media pluralism. The radicalization and bias also affected other media publishers. Despite of the availability of many sources, it is difficult to get objective information, especially from the largest broadcasters. As a report by The Freedom House indicates, the Independent Media rating declined due to multiple attempts to silence government critics, attacks on journalists, and successful government efforts to “re-Polonize” the private media sector (Freedom House 2021). Increased media polarisation indicates not only a polarisation of the political scene but also the split of society into two sides of the barricade. Without the clear presentation of facts, the ground for the spreading of fake news is fertile. This questions the logic of the democratic process where public debate conveyed by an unbiased media should lead to a well-informed society.

Total opposition

Because of the specificity of the Polish proportional representation election system, almost all of the Polish governments have been coalitional. With PiS 2015 electoral victory, for the first time since 1989, the ruling party obtained a total majority. Therefore, PiS did not need any additional supporters, not to mention the need to discuss political changes with the opposing parties. As stated before, the first major conflict between the government and opposition started even before the elections, beginning the Polish Constitutional Tribunal crisis. However, the roots of the party antagonism go back even earlier to the Smolensk air disaster of 10th of April 2010. In this tragedy a Polish diplomatic plane crashed near the Russian city of Smoleńsk, killing all 96 people on board, including the President of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, and his wife Maria Kaczyńska, as well as many Polish politicians and parliamentarians. In the first months after the tragedy, the nation was united. However, very quickly, some members of the PiS party, including Jarosław Kaczyński, brother of the deceased President, began to question the randomness of the accident. This led to a clear division between those who believed that this tragedy had been an accident and those who believed in the theory that an assassination had taken place. The internal political conflict caused by this event proved to be very polarising. The exhumations of the victims and the investigation that took place in the following years stirred up emotions each time. The two main sides of this conflict—PiS and PO reminded each other of the pain and helplessness associated with the tragedy. This somehow established an unspoken principle of non-cooperation. Consequently, in 2015, not only did PiS not hesitate to implement all the desired changes in the law as soon as possible after the elections, but also PO did not think much before engaging in what it termed as a total opposition. The more PiS pushed ahead with their plans, the more the opposition was determined to prevaricate and block all discussion. Grzegorz Schetyna, then the PO chairman, stated on 28th of February 2016 that PO “(…) will be a total opposition to the total power” (Grzegorz Schetyna’s parliamentary office 2016). It quickly sent a message to Polish society, that either one is with the opposition or against it, and with no middle ground. This firm attitude resulted in two things. Firstly, PiS supporters were reassured that supporting the ruling party in everything it does is the only option, as there was no longer room for doubts or questions. The opposition in turn was determined to demonstrate that being a PiS supporter was only worthy of scorn. There ensued a derisory narrative pertaining to the lower social and educational status of the governing party’s voters4. PiS supporters remained loyal to those who did not mock their ideas and outlook. The second effect of the “total opposition” attitude was discord among the oppositional parties. Besides PO, other parties managed to win parliamentary seats, such as Modern Party (Pol. Nowoczesna), The Polish People’s Party (Pol. Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe—PSL) and The United Left (Pol. Zjednoczona Lewica). However, throughout the four years, prior to the next elections, they failed completely to present a united front against the government. Although they all opposed PiS, they could not agree on any substantial matter. This fatally undermined them with their base, who were tired of the constant conflict. In the parliamentary elections 2019, PiS once more gathered nearly 44% of the vote; which was over 8 million Poles (National Electoral Commission 2019). This showed that the party’s mandate from 2015 was not a one off, but a real expectation of the majority of voters. That said, the opposition managed to maintain a small majority in the Senate, the upper house of the Polish Parliament, but with the presidential support, PiS retained a substantial amount of governmental power.

The event that ultimately showed how frayed the political consensus had become came with the global COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the fact that the coronavirus pandemic had partially halted the normal functioning of many countries, some processes had to continue along a predetermined path. The scheduled elections in various countries were also considered to be of the utmost importance. Some countries, like France, chose to follow the standard legal way and conduct elections in accordance with the previously set date (Ministry of the Interior. France 2020). Some other countries, like Great Britain, decided to postpone them for a year with the hope that things would have normalised by then (Cabinet Office 2020). Elsewhere an alternative voting form was chosen, as in Germany, where in the state of Bavaria, the local government decided to organise a second ballot of local elections only in the form of postal voting (Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik 2020). With presidential elections planned for May 10, 2020, Poland faced the same dilemma.

One might think that the issue of organizing elections during a pandemic would be a challenge in itself. In Poland, however, this problem soon took the form of an open political conflict. In the first months of 2020, the support for incumbent President Andrzej Duda was at its peak, with him polling 60%; which would guarantee a victory in the first round of elections (Social Changes 2020). It came as no surprise that the set date of May 10 would be ideal for the ruling party, which continued to support Duda’s candidacy. As the pandemic situation worsened and the first serious restrictions were introduced in the country, not only did the support for the President Duda drop but also people began to question the legitimacy of organizing an election during a pandemic. Soon, almost all of the other Presidential candidates began to insist on postponing the election date, particularly given the fact that the elections provided an excellent opportunity for increased people-to-people contact. Moreover, pandemic restrictions made the entire election process more difficult. Candidates had a problem with collecting the 100,000 required signatures to stand in the election. Predictably, the ruling party did not perceive this as a problem, because the incumbent President had gathered the signatures with a singular ease. However, the health risk was worrying for all citizens, and for this reason on April 6, 2020, the Sejm received a parliamentary bill proposing that elections should be held only by postal vote (Sejm 2020). However, Poland had never conducted an election based exclusively on a postal voting form5. With only one month left before the election, there was no possibility of preparing such an election, whilst being able to provide reassurances pertaining to transparency, fairness and voter secrecy. ODIHR issued an opinion that the presidential election in Poland in the proposed form could not be considered as democratic (ODIHR 2020a). Many officials and academic institutions supported this very statement. The ruling party, however, stood its ground. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki ordered the Polish Post Office to prepare for the postal elections, even though they were completely unready to accomplish this task in such a short time. Until the very last moments, no one in the country was sure if the elections would take place. Ultimately, on May 7, 2020, only three days before the set election date, the National Electoral Commission informed the nation that 10th May voting would not take place, due to many misconducts (National Electoral Commission 2020). The clear impossibility of being able to implement the plan, the lack of ballot papers and missing voter lists ultimately persuaded the government that they had to withdraw from the originally planned date. At the same time, any voices from the opposition side were treated as a smokescreen aimed at postponing the election date in order to lower support for Andrzej Duda. This was also the reason why the postponed election date was set for June 28, 2020 (Marshal of the Sejm 2020), this time in a hybrid form (presenting and postal voting). During the next few weeks, the support for the incumbent President steadily declined. This gave an impetus for the newly appointed opposition candidate Rafał Trzaskowski, President “Mayor” of Warsaw, who managed to gather support not only from PO voters but also from the supporters of other presidential candidates. After the first round of presidential elections on June 28, 2020 none of the candidates received more than 50% votes which resulted in a second round run off ballot, which was scheduled for July 11, 2020. As the chances for both candidates were level, both sides forgot for a time about the arguments related to the health and safety of citizens during the pandemic. The most famous statement came from the Prime Minister Morawiecki, who encouraged people to cast their votes by saying that they should not be afraid of the virus because it is in retreat (Tilles 2020a). Ultimately, the elections ended with a narrow win by the incumbent President Andrzej Duda (51.03–48.97%).

Electoral conflict proved that a polarising winner-takes-all logic governs Polish politics. The COVID-19 pandemic was treated more like an obstacle as opposed to the serious threat it actually was. Before the second ballot, not even one public debate took place between the candidates. Instead, Duda and Trzaskowski decided to present their views in their various supporting media outlets. The totality of the conflict in Poland results in the tuning out of any meritorious argument that came from the opposite side. There has been a visible decrease of political trust among the party supporters, as well as complete rejection of a dialogue as a form of conflict resolution, even in the face of a nationwide crisis. The Presidential elections of 2020 showed that current Polish politics is unable to cope with either changes or crises, which can only lead us to question the ability of Polish democracy to endure.

Impoverishment of the public political debate

It has been proved that strong political polarisation can contribute to the deterioration of communication quality and the radicalization of political views (Küpper and Váradi 2021, p. 10.). Polarisation is governed by negative feelings and the creation of identities based on moral panic, xenophobia and strong emotions, as well as obscene or offensive words (Prinz 2021). When Krystyna Pawłowicz, a controversial figure in Polish politics and a judge of the Constitutional Tribunal, compared women who protested against the tightening of the abortion law in Poland to Nazi SS criminals (Cienski 2020), one could argue that she is known for this type of hyperbole and it cannot be carried over to the whole population. When Jarosław Kaczyński in 2017 in the Sejm took the rostrum and shouted to the opposition deputies how they had murdered his brother with the additional appendance of the offensive wording (Mańkowski 2017) an explanation was harder to find. However, when Andrzej Duda—the incumbent president seeking re-election in 2020—during the election campaign referred to LGBT ideology as worse than communism (BBC 2020), Polish society started to take notice. During the multiple protests that occurred in the country in recent years, hate speech and vulgarisms have become a staple of the conveyance on both sides of the political conflict. It was also clear during election campaigns, when in both 2019 and 2020 the ODIHR observatory report stated that increased instances of intolerant rhetoric, which was xenophobic, homophobic and anti-Semitic in nature, should not only be prohibited but also publicly disavowed whenever it occurs (ODIHR 2020c, p. 13). However, in the Polish legal system the notions of hate speech or hate crimes do not exist expressis verbis. What is more, the Polish Constitution and Penal Code mention only a limited catalogue of groups protected from public insult or hatred (see: art. 13 of the Constitution of Republic of Poland and art. 256, 257 of the Polish Penal Code). The former Polish Ombudsman Adam Bodnar identified those deficiencies in 2020 and made a direct intervention with Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. In an official letter, he stated the need to create a comprehensive policy to combat crimes motivated by hatred and prejudice based on not only nationality, ethnic origin or religion (as it is listed in aforementioned legislation), but also on sexual orientation and identity, age or disability (Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich 2020). Amnesty International Report already in 2015 stated that despite suffering widespread discrimination, the scope of Polish anti-discrimination law is very limited and protects lesbian, gay and bisexual people only in the area of employment (Amnesty International 2015). However, soon the term hate speech became in Poland a part of the political game. The opposition uses it freely to prove that the ruling party and the government does not acknowledge its existence. In consequence, when PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński was asked about this during an interview; and he responded that he rejects this terminology because it is a concept that tries to introduce one-sided censorship against only right-wing parties (Mazurczak 2019). The concept of hate speech in Poland has been stripped of its real meaning, which made it harder for the real victims to seek justice. Article 19’s report from the Media Against Hate initiative showed that the number of prosecutions and convictions of hate crimes remains dangerously low (Article 19 2018).

Since the sociopolitical scene in Poland has clearly become polarised, this means that the checks and balances no longer work in the way that they should. With polarised rhetoric, society cannot trust any solution, even the right one. Citizens do not trust those who check or those who are checked. The interventions of the aforementioned former Polish Ombudsman, Adam Bodnar, pertaining to the deepening of the constitutional crisis, the proliferation of hate speech, and violations of the freedom of speech were ignored despite his enormous popularity and positively evaluated work. As his term of office ended in 2020, Sejm had tried to elect a new Ombudsman. It took more than a year and six different voting ballots to choose a new candidate. The problem was the absolute lack of trust in the newly proposed candidates. If PiS proposed a candidate, the opposition rejected them on the grounds that they may be politically biased. The same obtained for the candidates from the other side. It did not seem to matter that during that time Poland was deprived of such an important office.

Political polarisation and the deteriorating quality of public debate has clearly undermined Poland’s standing on the international arena. The activation of the Rule of Law Framework by the European Commission shows that Poland has begun to pose a threat to the European order. The same applies to the case of the European Parliament condemning Polish homophobic actions; including LGBT-free zones present in over 80 local government units (European Parliament 2019). This caused loss of funds of some units from not only UE but also the Norwegian Funds In July 2020, the European Union rejected grants under a twinning program to six Polish cities, because of their disparaging declarations with respect to the LGBTQ community (Euronews 2020). In addition, the Polish government’s plans to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, which seeks to prevent and combat violence against women further soiled an already tarnished reputations. The current government treats criticisms of actions as an oppositional carping, and not a “wake-up” call. Polarisation in the country has blurred the lines between the act and the person, having turned the political scene into a zero-sum game. Unfortunately, this has contributed to a significant deterioration in the social situation of some groups. Sexual minorities or immigrants have become victims of this conflict as a targeted emotional and aggressive rhetoric briefs against their protected rights in EU law.

Summary

Today’s Europe is changing. Representative democracy is in crisis, traditional parties are being challenged and anti-establishment parties are on the rise (Casal Bértoa and Rama 2021). Poland is one of the countries whose future of democracy remains in doubt. In 2021, it became one of the most polarised countries in Europe and its quality of democratic governance continued to deteriorate. However, associating Polish democratic backsliding only with a change in government or some selected conflict would be a mistake. Dysfunctions of the Polish system have not solely been the result of institutional changes, but rather an inability to adapt to societal transformation, globalization processes and international crises; all of which require mindfulness, national and transnational dialogue and political flexibility. The polarised political scene in Poland has made it impossible to be adaptive to these changes, because political parties have chosen to rigidly stick with predetermined ideological positions. Poland in 2022 is a dysfunctional democracy where unlawful outcomes have become a normative standard. To make matters worse, Polish parties are indifferent to many of society’s problems, particularly when their resolution does not offer electoral advantage. Due to the divide, the voices of reason have been rendered mute. The conflict over the 2020 presidential election was one of many instances that showed how irrelevant real argumentation is when faced with a blind determination to achieve political power. In the polarised state, the opponent will always present a bad idea. The consequences can be a year’s delay in the appointment of a new Ombudsman. However, it can also end as a constitutional crisis, and with an undermining of the legal and judicial system. At this moment, the actions of Polish politicians are imposing further polarisation. We still do not know how this state of affairs will influence the direction of the country in the coming years; but we are observing the first outcomes. Massive street protests, increases in aggression and hate speech in public communication, a deterioration of the status of minorities, and a rising conflict with the European Union are but the first indicators of what may actually come to pass if the country does not change its course. With the unfolding reality of another migration crisis caused by Russia’s attack on Ukraine, Poland is once again at the forefront of European diplomacy. Its ability to play a part in a resolution of the crisis, whilst maintain its democratic status, could have a significant impact on the future centrality of European values. For this reason, it is more important than ever to understand the causes of modern democratic deteriorations. We need to address the issue of political polarisation in order to be able to strengthen European democracies in the face of the many crises that may yet manifest.

Conflict of interest

S. Horonziak declares that she has no competing interests.

Footnotes

The talks between the Polish People’s Republic government and opposing trade union Solidarność and other groups in an attempt to defuse the social conflict and start compromise system transformations.

In this article, I will be using the Polish abbreviations of the political parties’ names, as they are the most commonly used in both national and international media.

7th and 8th of June 2003: The referendum on consenting to the ratification of the Treaty on the accession of the Republic of Poland to the European Union.

In the parliamentary elections 2015 PiS received the greatest support among people with primary and lower secondary education, as well as with basic vocational education: Wirtualna Polska (2015).

Before this legal change, the only people who could vote by post were voters with a medical report stating moderate or severe degree of disability and Poles living abroad.

References

- Amnesty International. 2015. Targeted by hate, forgotten by law. Lack of a coherent response to hate crimes in Poland. London: Peter Benenson House. [Google Scholar]

- Article 19. 2018. Poland: responding to ‘hate speech’. Report. https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Poland-Hate-Speech.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2022.

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik. 2020. Kommunalwahl Stichwahl am 29.03.2020. https://www.kommunalwahl2020.bayern.de/uebersicht_personen_wahlbeteiligung_1.html. Accessed 13 May 2021.

- BBC. 2015. Poland protests: thousands march ‘to defend democracy. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35083561. Accessed 10 June 2021.

- BBC. 2016. Poland protests: crowds renew calls for press freedom. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38352742. Accessed 22 July 2021.

- BBC. 2020. Polish election: Andrzej Duda says LGBT ‘ideology’ worse than communism. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53039864. Accessed 12 July 2021.

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index. 2020. Transformation Index: Poland. https://atlas.bti-project.org/1*2020*CV:CTC:SELPOL*CAT*POL*REG:TAB. Accessed 27 July 2021.

- Bramson, Aaron, Patrick Grim, Daniel Singer, William Berger, Graham Sack, Steven Fisher, Carissa Flocken, and Bennett Holman. 2017. Understanding polarisation: meanings, measures, and model evaluation. Philosophy of Science 84(1):115–159. 10.1086/688938. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. 2020. Postponement of May 2020 elections. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/postponement-of-may-2020-elections. Accessed 6 June 2021.

- Casal Bértoa, Fernando. 2019. Polarisation: what do we know about it and what can we do to combat it? Policy Memo No. 30. Georgian Institute of Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Casal Bértoa, Fernando, and José Rama. 2021. Polarisation: what do we know and what can we do about it? Frontiers in Political Science10.3389/fpos.2021.687695. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS). 2015. Komunikat z badań CBOS. Zadowolenie Z życia (3)/2015:1–7. ISSN: 2353-5822. https://cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2015/K_003_15.pdf

- Chancellery of the Sejm. 2016. Informacja na temat zmian w organizacji pracy mediów w Parlamencie. https://archive.is/nnS5q. Accessed 20 June 2021.

- Chapman, Annabelle. 2017. Pluralism under attack: the assault on press freedom in Poland. Freedom house. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FH_Poland_Media_Report_Final_2017.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2021.

- Cienski, Jan. 2020. Poland’s government backed into a corner over abortion. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-government-abortion-backed-into-corner/. Accessed 15 May 2021.

- Clark, Ian. 2014. Globalization and the post-cold war order. In The globalization of world politics, ed. John Baylis, Steve Smith, and Patricia Owens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Constitutional Tribunal (Poland). 2015r. Postanowienie z dnia 25 listopada 2015 r. Sygn. akt K 29/15 [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2017. The functioning of democratic institutions in Poland. http://www.assembly.coe.int/LifeRay/MON/Pdf/DocsAndDecs/2017/AS-MON-2017-14-EN.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2022.

- Dahl, Robert. 2015. On democracy, 2nd edn., New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalio, Ray, Steven Kryger, Jason Rogers, and Davis Gardner. 2017. Populism: the phenomenon. Technical Report 3/22/2017. Bridgewater Daily Observations (203):226–3030. Publication date March, 22, 2017. https://www.bridgewater.com/_document/populism-the-phenomenon?id=00000171-a337-d77b-a973-af3727ef0000

- Dempsey, Judy. 2016. Poland’s polarising politics. Carnegie Europe. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/63529. Accessed 25 May 2022.

- Dobrowolski, Tomasz. 2017. ‘Ucieczka od wolności’—Kryzys zaufania do demokracji liberalnej. Zjawisko przejściowe czy długotrwała tendencja? Krakowskie Studia Międzynarodowe 14(4):151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdowicz-Bieć, Maria. 2011. Reasons why Poland avoided the 2007–2009 recession. Prace I Materiały, Instytut Rozwoju Gospodarczego (sgh) 86(2):39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Euronews. 2020. EU funding withheld from six Polish towns over ‘LGBT-free’ zones. https://www.euronews.com/2020/07/29/eu-funding-withheld-from-six-polish-towns-over-lgbtq-free-zones. Accessed 2 July 2021.

- European Commission. 2016. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2016/1374 of 27 July 2016 regarding the rule of law in Poland. Official Journal of the European Union L 217/53-68.

- European Commission. 2017. Rule of Law: European Commission acts to defend judicial independence in Poland. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_17_5367. Accessed 20 June 2021.

- European Commission. 2021. Statement by the European commission on the decision of the polish constitutional tribunal of 14 july. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_21_3726. Accessed 20 June 2021.

- European Parliament. 2019. Parliament strongly condemns “LGBTI-free zones” in Poland. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20191212IPR68923/parliament-strongly-condemns-lgbti-free-zones-in-poland. Accessed 13 July 2021.

- European Parliament. 2022. The commission’s rule of law report and the EU monitoring and enforcement of article 2 TEU values. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/727551/IPOL_STU(2022)727551_EN.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2022.

- Faculty of Law and Administration, University of Silesia in Katowice. 2016. Stanowisko w sprawie podstaw orzekania przez Trybunał Konstytucyjny w przedmiocie zgodności z Konstytucją ustawy z dnia 22 grudnia 2015 r. o zmianie ustawy o Trybunale Konstytucyjnym. https://archive.is/9V8xj. Accessed 29 June 2021.

- Forsal.PL. 2016. Prognozy Statfor: Polaryzacja społeczeństwa w Polsce i tarcia z Zachodem, Brexitu nie będzie. https://forsal.pl/artykuly/935452,prognozy-statfor-na-ii-kw-polaryzacja-spoleczenstwa-w-polsce-i-tarcia-z-zachodem-brexitu-nie-bedzie.html. Accessed 5 May 2022.

- Freedom House. 2015. Nations in transit 2015: Poland. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/nations-transit/2015. Accessed 27 July 2021.

- Freedom House. 2021. Nations in Transit 2021: Poland. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/nations-transit/2021. Accessed 27 July 2021.

- Funke, Manuel, Moritz Schularick, and Christoph Trebesch. 2016. Going to extremes: politics after financial crises, 1870–2014. European Economic Review 88(C):227–260. 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.03.006. [Google Scholar]

- Giebler, Heiko, and Annika Werner. 2020. Cure, poison or placebo? The consequences of populist and radical party success for representative democracy. Representation 56(3):293–306. 10.1080/00344893.2020.1797861. [Google Scholar]

- Gilejko, Leszek. 2012. Trzy wymiary demokracji: polskie problemy. In Dylematy polskiej demokracji, ed. Łukasz Danel, Jerzy Kornaś. Kraków: Fundacja Gospodarki i Administracji Publicznej. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, Arianna, and Matthew Wood. 2022. Understanding democratic stress. Representation 58(1):1–12. 10.1080/00344893.2021.2019821. [Google Scholar]

- Górska, Paulina. 2019. Polaryzacja polityczna w Polsce. Jak bardzo jesteśmy podzieleni?, Center for Research on Prejudice. Warsaw. http://cbu.psychologia.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/410/2021/02/Polaryzacja-polityczna-2.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2022.

- Grzegorz Schetyna’s parliamentary office. 2016. Będziemy totalną opozycją dla totalnej władzy. http://schetyna.pl/aktualnosc/bedziemy-totalna-opozycja-dla-totalnej-wladzy. Accessed 10 June 2021.

- Hartmann, Hauke, and Peter Thiery. 2022. Global findings. Resilience wearing thin. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. 10.11586/2022032. [Google Scholar]

- Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (HFHR).. 2017. Niepublikowanie wyroków TK: dokumenty z śledztwa. https://www.hfhr.pl/niepublikowanie-wyrokow-tk-dokumenty-z-sledztwa/. Accessed 13 May 2021.

- Horonziak Sonia. 2021. Wybory w świetle polaryzacji. Mowa nienawiści w kampanii parlamentarnej 2019 roku. In Kampania parlamentarna 2019, ed. Piotr Borowiec, Adrian Tyszkiewicz. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2016. Trump, Brexit and the rise of populism: economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Working Paper., 16–26. Harvard: Kennedy University. [Google Scholar]

- International IDEA. 2021. The global state of democracy 2021. Building Resilience in a Pandemic Era. Stockholm: International IDEA. 10.31752/idea.2021.91. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, Maria. 2005. Polska. Ale jaka? Warszawa: Oficyna Naukowa. [Google Scholar]

- Jażdżewski, Leszek. 2015. Dlaczego PO przegrała wybory. Polityka. https://jazdzewski.blog.polityka.pl/2015/10/29/dlaczego-po-przegrala-wybory/. Accessed 20 May 2022.

- Körösényi, András. 2013. Political polarisation and its consequences on democratic accountability. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 4(2):3–30. 10.14267/cjssp.2013.02.01.

- Küpper, Beate, and Luca Váradi. 2021. Polarisation in Europe: Positioning for and against an open and diverse society. In Polarisation, radicalisation and discrimination with focus on Central and Eastern Europe 2021, Demokratie gegen Menschenfeindlichkeit. Nr. 1/2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maliszewski, Norbert, and Aleksander Wysocki. 2016. Rozłam społeczny jako skutek sporu o Trybunał Konstytucyjny. IUSTITIA 1(23):22-24. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal of the Sejm. (Poland) 2020. Postanowienie Marszałka Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 3 czerwca 2020r. w sprawie zarządzenia wyborów Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Dz.U. 2020 poz. 988.