Abstract

This study aims to better understand the perceptions and experiences related to incivility by students and faculty across multiple academic programs and respondent subgroups at a regional university in the southern United States. The study used a thematic analysis to examine student and faculty responses to three qualitative questions that focused on their perceptions of recent experiences and primary causes of incivility in higher education. Clark’s (2007, revised 2020) Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education and Daniel Goleman’s (1995) Emotional Intelligence domains were used to give meaning and context to the study findings. For this group of respondents, the study found that incivility in higher education between faculty, students, and faculty and student relationships remain pervasive. Despite the global pandemic and social unrest occurring during the study period, these behaviors did not coalesce around a specific subgroup. Both faculty and students agreed that relationship management with a keen focus on communication could mitigate academic incivility. These findings can inform educators, students, and future researchers in planning meaningful interventions that address incivility in higher education. A relational approach centered on communication skill-building is needed to combat the persistent issue of incivility in higher education.

Keywords: Incivility, Higher education, Faculty, Student, Emotional Intelligence

Incivility in higher education is not a new phenomenon. It likely got its inception in the first classroom (Holton, 1995). Academic incivility is getting worse despite decades of research to better understand this complex issue (Knepp, 2012). Clark (2008a) defines incivility in higher education as behavior “demonstrated by students or faculty… [that] violates the norms of mutual respect in the teaching–learning environment” (p. E38). It is relevant to note that civility is more than the absence of incivility. Pascarella and Terenzini (2005) describe civility as, “the extent to which the individual shares the normative attitudes and values of peers and faculty in the institution and abides by the formal and informal structural requirements for membership in that community or in subgroups of it” (p. 54).

The complex construct of incivility and its role in academic misconduct has been studied from numerous perspectives. Boice (1996) categorized classroom incivility and ranked the most problematic areas. A generation of researchers followed his work refining the definition of civility (Buttner, 2004; Clark & Spring, 2007), categorizing the observed behaviors (Caboni, et al., 2004; Knepp, 2012), scaling the severity of incivility (Bjorklund & Rehling, 2010; Clark & Springer, 2007; Lashley & DeMeneses, 2001), measuring the frequency of uncivil events (Lashley & DeMeneses, 2001; Mohammadipour et al., 2018), and identifying contributing factors. Researchers found that entitlement and generational shifts (Kopp & Finney, 2013; Lippmann et al., 2009), narcissism (Lippmann et al., 2009), technology (Knepp, 2012), societal acceptance (Lawrence, 2017), the academic environment itself (Lashley & DeMeneses, 2001; Meyers et al., 2006; Nordstrom et al., 2009), and varying learner/teacher demographics (Knepp, 2012; Nordstrom et al., 2009) contribute to academic incivility.

The search for a solution to academic incivility has an equally large footprint in the literature. Because incivility comprises a range of behaviors that have a harmful impact, but may or may not have harmful intent, solutions often highlight the importance of the intentional practice of classroom civility. Researchers suggest a range of mitigation efforts, including implementing prevention plans that address expected classroom behaviors (Black et al., 2011; Nilson & Jackson, 2004), sharing research about the importance of civility (Rehling & Bjorklund, 2010), enforcing behavioral standards (Nordstrom et al., 2009), establishing a class code of conduct (Nilson & Jackson, 2004; Nordstrom et al., 2009), including a civility policy in the course syllabi (Ausbrooks et al., 2011; Buttner, 2004; Morrissette, 2001), faculty demonstrating approachability and respectful communication (Morrissette, 2001; Nordstrom et al., 2009), and creating an engaging learning environment (Black et al., 2011; Boice, 1996; Clark, 2009; Morrissette, 2001). Current literature suggests that once incivility occurs, faculty should confront it directly, quickly, and privately (Alberts et al., 2010; Ausbrooks et al., 2011; Black et al., 2011; Boysen, 2012; Morrissette, 2001). Numerous studies report the positive impact of faculty role modeling professional and civil behavior for students (Ausbrooks et al., 2011; Buttner, 2004; Luparell & Frisbee, 2019; Morrissette, 2001).

Contributing factors and mitigation efforts are essential to understand the scope of incivility. Of equal importance is the impact of these behaviors on the members of the academic community. When considering the immediacy of the impact, the list of harmful outcomes from uncivil encounters is vast. Rawlin (2017) categorized the detrimental effects on health and well-being, the teaching and learning environment, stress levels, and overall levels of incivility, asserting that “incivility incites incivility” (p. 711). Negative emotional outcomes for faculty (decreased job satisfaction, anxiety, and burnout) and students (diminished self-esteem, sense of belonging, and community) (Clark, 2008b; Wagner et al., 2019) are some of the most reported consequences of uncivil academic behaviors. It is relevant to acknowledge that incivility also has a negative organizational impact (poor teaching/student performance and increased student/faculty turnover) (Rawlins, 2017).

The long-term effects of higher education incivility have a limited presence in current literature. Little is known about the career trajectory of uncivil faculty and graduated students. There is some evidence that unaddressed academic incivility sets the stage for future professional incivility. There is evidence that uncivil students become uncivil professionals (Luparell & Frisbee, 2019). This professional incivility saturates work cultures and leaches into the communities that are served by these former students, now professionals. Research makes clear that civility is the antecedent to achieving equity and justice for vulnerable community members (Mullen et al., 2011). Without civility as an embedded professional skill, communities will continue to struggle in affirming and mitigating the equity gap.

A key pillar of professionalism is civil behavior, irrespective of the professional field. In higher education settings, faculty are accountable for socializing students to their future professional role identities using civility as a framework. To do this effectively, it is essential that as leaders in higher education, faculty members be willing to reflect on their uncivil behavior, make changes to improve that behavior, and act as role models for students. A final step in this process would be faculty assisting students in connecting civil behavior with professional role expectations. There is limited data outside of health professional programs—where civility is part of the professional code of ethics—to link academic incivility and the ways faculty address incivility to the broader context of students’ future professional role performance across all disciplines.

This study aims to better understand the perceptions and experiences related to incivility by students and faculty across multiple academic programs and respondent subgroups at a regional four-year university in the southern United States. This study focuses on the diverse, often under-resourced, and/or first-generation students. These students are a large population of learners in regional universities but are typically a minority at major research institutions (Henderson, 2009; Miller, 2017). These students are more likely to be working off-campus, less likely to be traditional college-aged (18–21), and therefore more likely to participate simultaneously in academic environments and outside workplace environments with different institutional cultures and civility codes (Miller, 2017; Scott & Biag, 2016; Zack, 2020). While the study was not planned to occur during a highly stressful academic period, the 2020 Presidential election season gave rise to numerous national social and political conflicts while the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic remained in full swing. In this context, this study offers a perspective on academic incivility in a time of heightened inequities, enhanced stress, and increased levels of trauma and isolation.

In the years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, affective, social, and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning have taken a more central role in studies of higher education. Formerly confined to studies of children in primary and secondary education (Cole et al., 2005; Crosby, 2015), social and emotional learning (SEL) research is increasingly aware of the emotional environment and emotional outcomes of academic interactions in higher education. Research into trauma-informed teaching (Gutierrez & Gutierrez, 2019; McInerney & McKlindon, 2014) stresses the importance of creating safe and healthy effective learning environments through empathy and respect. Pre-pandemic studies of social and emotional learning identify the protective and moderating effects of positive social environments—both in and out of the classroom—on perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction, academic resilience, educational equity, and learning engagement (Bai et al., 2019; Bassett, 2020; Chukwuorji et al., 2018; Jagers et al., 2019; Lim & Richardson, 2021). As disruptions to a climate of respect and social support, uncivil academic behaviors heighten the challenges of learning in an already stressful and individually and collectively traumatic environment.

This study adds to the existing research in these emotional and affective dimensions not only by identifying the negative consequences of incivil academic behaviors but also by understanding the role of these dimensions in the experience and causes of incivility. Much previous research has been limited by glossing over the systemic causes of academic incivility and attributing incivil behavior to negative psychological traits, such as entitlement or superiority (Clark & Springer, 2007). As a result, proposed interventions have focused on clarifying expectations, setting norms, and reining in uncivil behaviors through conformity to civil practice. Based on this individual approach to the reasons for incivility, Cahyadi et al. (2021) hypothesized that the strength of an individual’s internal locus of control—their belief in their own ability to affect and control events in their lives—would serve to mediate against the negative effects of classroom incivility on learning engagement. Surprisingly, they found internal locus of control played no role in sustaining learning engagement in the face of classroom incivility (Cahyadi et al., 2021). Studies that rely on promoting individual adherence to civil norms without interrogating the causes of diversion from those norms do not go far enough to address the growing gap between definitions and perceptions of civil and uncivil behaviors between instructors and students based on cultural, generational, and experiential differences. This study maps the perceived behaviors, experiences, and causes of academic incivility onto the skills of emotional intelligence (EI) to uncover underlying causes of academic incivility and mitigate its negative effects on academic achievement, learning engagement, and ultimately future professional behavior.

Aim of the Study and Research Questions

In this study, we administered the proprietary Incivility in Higher Education Revised (IHE-R) survey developed by Clark et al. (2015) which asks student and faculty participants to rate 24 behaviors on a 4-point Likert scale (1-not uncivil to 4-highly uncivil) as well as rating the frequency with which these behaviors are witnessed (1-never to 4-often) and asks faculty participants to self-report frequency with which they engage in the identified 24 behaviors (1-never to 4-often). Additionally, the IHE-R includes several open-ended questions focused on student and faculty experiences of incivility in higher education, potential causes for incivility, and strategies to improve civility, as well as consequences of incivility in higher education. Results for the quantitative portion of the study are reported elsewhere (Hudgins et al., 2022). We were also interested in student and faculty perceptions of the primary cause of incivility. Results related to consequences of incivility and strategies to improve civility in higher education are reported separately. The following research questions guided the analysis.

What are the experiences of students and faculty both as recipients and witnesses of incivility in higher education?

What are the student and faculty perceptions of the primary cause of incivility in higher education?

Participants

Faculty and staff at a public university in the southeastern United States were invited to participate in an Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and exempted study aimed at understanding how incivility is experienced by students and faculty overall and in subgroups in higher education. A total of 53 faculty described experiences with uncivil behaviors and/or causes for incivility compared to 281student participants. A majority of the faculty participants were white females over 30 years old. A majority of the student participants were white females less than 30 years old. Most faculty participants reported holding a graduate degree while most student participants reported holding an Associate degree. Additional demographic characteristics of participants are described elsewhere (Hudgins et al., 2022).

Methods

A thematic analysis was utilized to analyze student and faculty responses to three qualitative questions which were included as part of a survey administered to faculty and student participants in October 2020 as part of an IRB reviewed and exempted research project. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six step model as described by Maguire & Delahunt (2017) guided this thematic analysis. Three qualitative questions related to witnessing or experiencing uncivil behaviors and potential causes of incivility were independently coded by the principal investigator and two other team members. Both inductive and deductive coding was used to analyze the qualitative data. A codebook was developed by the entire research team following initial coding to ensure consistency in coding across team members. Disagreement between initial coders were resolved by consensus of the entire research team for all student and faculty responses. Final codes were then organized into themes by the research team. Qualitative responses that did not address the questions asked were excluded from the analysis. Participant responses were also analyzed to determine whether the response was referencing student, faculty, student and faculty, or general behavior. Finally, all participant responses were compared by race (non-white or white) to identify differences.

Results

Theoretical Framework

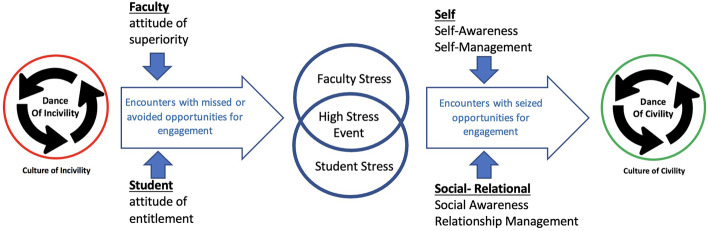

As a result of inductively coding the data the research team developed an adapted theoretical framework to reflect faculty and student experiences with uncivil behaviors in higher education. Two theoretical frameworks were combined to provide context for study findings. Clark and Springer (2007) Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education and Daniel Goleman’s (1995) Emotional Intelligence domains were used. Clark and Springer (2007) introduced this model as a metaphorical “dance” between two people where the participants respond, positively and negatively, to another’s “steps.” These actions and reciprocal responses cultivate a culture of civility or incivility. Clark (2008a) explains that “creating a culture of civility requires communication, interaction, and an appreciation for the interests each person brings to the relationship” (p. e37). This model demonstrates a continuum between civility and incivility that is influenced by participants’ attitudes (faculty attitudes of superiority, student attitudes of entitlement), high-stress encounters, and opportunities to engage (or not) with each other. With each ebb and flow of the interaction, civility or incivility can be experienced.

Salovey and Mayer (1990) defined EI as, “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.” Salovey and Mayer (1990) identified perceiving, using, understanding, and managing emotions as the four main EI abilities. In 1995, Daniel Goleman offered a new way of thinking about these concepts when he offered his own definition of EI that explained EI by organizing the behaviors as inter-related components to include: emotional self-awareness (knowing what one is feeling at any given time and understanding the impact those moods have on others), self-regulation (controlling or redirecting one’s emotions, anticipating consequences before acting on impulse), motivation (utilizing emotional factors to achieve goals, enjoy the learning process and persevere in the face of obstacles), empathy (sensing the emotions of others), and social skills (managing relationships, inspiring others and inducing desired responses from them) (Goleman, 1995). These components are organized into four quadrants including self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management.

With the author’s permission, the authors adapted the Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education including Goleman’s EI domains to further explain the influencing factors at the time of faculty and student encounters. By integrating Goleman’s’ self (self-awareness and self-management) and social-relational (social awareness and relationship management) domains into Clark’s “encounters with seized opportunities for engagement” phase, we believe students and faculty have the best opportunity to successfully progress through Clark’s civility model. Figure 1 provides details of this synthesis. We believe that EI provided critical “music” to Clark’s civility “dance.” In our thematic analysis, the student and faculty experiences clustered around Goleman’s EI components. These clusters provided context to our understanding of the issue of incivility in academic settings.

Fig. 1.

The relationships between Goleman’s emotional intelligence domains and Clark’s Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education. Note: Civility occurs on a continuum and can be directly influenced by elements of emotional intelligence. Clark’s Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education was adapted with permission

Experiencing Incivility

Faculty Perspectives

Faculty reported experiencing incivility across two EI domains including self-management and relationship management. Table 1 includes detailed information regarding the assignment of final themes to Goleman’s EI domains and competencies as well as student and faculty examples for each final code. Within the self-management domain faculty reported experiencing disrespect, negative emotional behaviors, and inattention. These behaviors align with two of the EI competencies (emotional self-control and initiative). Disrespectful peer faculty experiences were described as “I have heard one faculty member openly criticize the accomplishments of another” and “A professor making inappropriate comments about his/her student.” Faculty experiences involving negative emotional behaviors were reported as “In department meeting, some faculty raise their voices when they don't get their way.” Faculty described experiences related to inattention as “students are often ‘tuned out’ during class. They have little investment in participating,” and “students I have taught have been caught: eye rolling (2–3 students–1 very rude student did it a lot), almost sleeping in class (1 student), back talking (1 student–the same rude student mentioned above), interruptions during class that are not in the good way (i.e. a question or for clarification), pulling the phone out during classroom instruction to text or watch videos or make a call (just a few students–I quickly put a stop to it by asking that the student put it away–firm but gentle is my approach), not being prepared for class (many students), turning in assignments late (over half my class), not paying attention (you know this because they ask you the same thing that you just explained or told them several times to do, such as "Do we have to have it in MLA format? or "Did you want the paper on an article or a chapter from a book?”.

Table 1.

Themes and representative quotes from faculty and students categorized by emotional intelligence (EI) domain and competency for behaviors experienced and witnessed

| EI Domain | EI Competency | Theme | Faculty example |

Student example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | Emotional awareness | Bias | “Trying to intermediate between several advisees and a faculty member who comes off as rude, racist, and sexist in class.” | “A teacher using people's pronouns in a class, and making fun and dismissing the issue as crazy, being discriminatory against the issue of gender identity.” |

| Self-Motivation | Apathy | “Disinterest and lack of appreciation and compensation” | “Students do not take their classes seriously.” | |

| Boredom | None | “Boredom” | ||

| No interest | None | “For students, a lot of what it takes to get a degree contributes nothing to the degree itself or the career one hopes to use the degree for. These "enrichment" activities often end up just waste students' time and money, especially when given the testimony of recent alum who had to endure barrage after barrage of useless information.” | ||

| Accurate Self-Assessment | Ego | None | “Typically, egos get in the way of professionalism” | |

| Self-Confidence | Poor self esteem | None | “Insecurities in oneself” | |

| Self-management | Emotional self-control | Disrespect | “Students climbing over tables to leave class the clock moment class ended, but not before I finished talking and dismissed them.” | “In my last semester students would talk in [have] side conversations rather than paying attention.” |

| Lack of respect | “A lack of respect” | “Lack of respect for others” | ||

| Negative emotional behavior | “In department meeting, some faculty raise their voices when they don't get their way.” | “a teacher and student argued in the classroom in front of everyone.” | ||

| Stress | “STRESS (for both faculty and students).” | “Outside problems causing stress” | ||

| Initiative | Inattention | “Students talking in class, on phone in class. Faculty on computer during meetings.” | “I had three students who thought they knew how to teach better than the instructors/professors. They were rude in class, always on their phones/computers, and they made rude comments. This is very rare however.” | |

| Communication | Poor communication | “In a meeting just this week, I was shown a tremendous amount of disrespect. The person used poor language and had a high level of unprofessionalism.” | “Teacher has never responded to a single email the entire semester; I have to email the head of the department to get a response.” | |

| Social awareness | Empathy | Lack of empathy | “Some people do not think about how certain behavior would affect them if they were the one targeted.” | “a student was not accommodated or given any grace for having a full-time job and was called out in class.” |

| Organizational awareness | Lack of clear expectations | “Students can be uncivil because they haven’t been taught better communication skills. They aren’t uncivil in their heart of hearts, but their language is. Describing a situation may reduce anonymity.” | None | |

| Service orientation |

Poor professional performance |

“Faculty who refuse to go over exams with students because they don’t want to have to write a new exam” | “My teacher not being prepared for our class when it went virtual. The class was hybrid to begin with, but she didn't have the necessary materials for us to learn and left us all to essentially teach ourself. We had class twice maybe the whole semester” | |

| Poor academic performance | None | “Students not taking initiative and participating in our group project” | ||

| Lack of accountability | “No accountability for faculty or students. Also, faculty are not consistent in modeling proper behaviors.” | “There is no reward for acting civilly; there are only punishments for acting uncivilly.” | ||

| Relationship management | Influence | Power | “A student sent me multiple emails whenever they received a grade they disagreed with, threatening to involve my superiors because I did not give them the grade they expected.” | “I have heard professors bragging about how hard their class is and that students are on the fence of graduating or not because of their class.” |

| Developing others | Lack of experience | “Lack of engagement, acknowledgment, and awareness of available resources for managing relationships and expectations.” | “I think incivility almost always has to do with students' experiences prior to higher education, and most of them are inadequately prepared for the challenges they face as a result. The education system as a whole is to blame rather than a specific part, however, and trends throughout my life related to education have only made things worse, widening gaps that needed to be closed.” | |

| Lack of awareness | “Lack of awareness” | “Lack of awareness? Dissatisfaction with role” | ||

| Communication | Poor communication | “Varied approaches to professional communication and interactions” | “Just unprofessional. And the lack of knowledge of knowing how to communicate with others” | |

| Teamwork and Collaboration | Negative interpersonal skills | None | “Some people are just less sensitive or more gruff than others” | |

| Lack of relationships | None | “Online cohort with a higher number of students makes it impossible to develop personal relationships.” |

Faculty experiences of incivility within the relationship management domain involved power and poor communication. Faculty described experiences of incivility related to power as “in university meetings there is a[n] underlying tone that is condescending to certain departments and ranks (non-tenure).” Poor communication was described as “colleagues do not reply in a timely manner (6 h.) to emails during normal working hours.” Faculty reported experiencing incivility more often with peers than students and some reported experiences with general uncivil behaviors. Examples of experienced incivility between faculty related to power included “I have seen a full-rank professor berate an administrative assistant over spelling in meeting minutes” and “a tenured faculty member, in discussion about the structure of the department, was very confrontational, standoffish, and rude to an adjunct. (It was about status and rank so that the tenured professor even went so far as to claim “I make X more than you” in terms of salary.) The adjunct was brought to tears by the encounter.”

Faculty also described experiencing uncivil behavior from students. These encounters were primarily related to communication, inattention, or disrespect. Uncivil student behaviors reported by faculty included “students not responding to e-mails from faculty members,” “rude student comments and gestures about class assignments” and ‘students sometimes impulsively send emotional (angry, upset) emails when they do not receive the grade, they believe they should have.” Faculty also reported experiencing incivility not specific to faculty or students related to disrespect, inattention, and power. Disrespect was described as “Gossip is basically rampant and on occasionally deployed intentionally and strategically to harm others,” “Blatant disregard for other’s opinions, concerns, beliefs. Curving grades.” Power was described as “Degrading remarks about where someone graduated from…” and inattention was described as “working on the computer during virtual meetings.”

Student Perspectives

Students reported experiencing incivility among all four EI domains, but most frequently reported experiences related to social awareness and self-management. Most often student experiences involved faculty which were commonly related to poor professional performance of faculty, disrespect, or communication. Poor professional performance was described as “comparing my work to another student[’]s and telling me I clearly don’t understand an assignment, but not telling me why I did wrong, not returning phone calls, not returning emails, grading unfairly.” Examples of disrespectful behavior included “eye rolling from professors when a student asks a question for the second time because they still don’t understand,” and “some of my professors swear a lot during their lecture and I feel it takes away from their teaching and is not very professional.” Poor communication was described as “a professor who sent emails but didn't respond to my repeated requests for help with an assignment” and “I wasn't able to get ahold of one of my professor[s] for the first three weeks of class.” Students also described experiencing uncivil behaviors from other students. Student-to-student encounters were often related to poor academic performance or disrespect. Poor academic performance was described as “students unprepared for class and refuse to participate” and “students refusing to do class work on time.” Disrespectful behavior from students was described as “students ignoring teachers and being disrespectful” and “A student was upset with a professor, so he slung a textbook and left the class.”

Students also reported experiencing uncivil behaviors not specific to faculty or student behaviors related to disrespect, communication, and poor professional performance. Examples of disrespect included “swearing” and “thinking they know everything.” General experiences related to communication included “not replying to emails, expressing political beliefs,” and “lack of communication, not answering emails.” Examples of general poor professional performance included “politics in the classroom,” “when the class goes off topic,” and “people coming in late.”

Experiences of Faculty and Students by Race

Finally, when comparing experiences based on race, reported experiences were described similarly between nonwhite and white participants. Moreover, nonwhite, and white participants most often reported experiences involving faculty. Most frequently reported experiences related to self-management and social awareness within the competencies of emotional self-control, communication, service orientation, and organizational awareness. Examples of emotional self-control were described as negative emotional behavior and disrespect. Nonwhite student participants described negative emotional behavior and disrespect as “My class and I was being yelled at by a professor” and “I have seen teachers blatantly be disrespectful to students for small reasons like a phone going off and they start cussing and ranting. Then end class.” respectively. White student participants described negative emotional behavior and disrespect as “a teacher and student argued in the classroom in front of everyone” and “in one of my synchronous virtual classes this semester, the professor makes condescending comments towards students almost every class. It is noticeably passive-aggressive, and I am afraid to participate in class because of his attitude” respectively. Nonwhite faculty participants described negative emotional behavior and disrespect as “In department meeting, some faculty raise their voices when they don't get their way,” and “Being interrupted while talking by a third person. Students arriving and or leaving early. Looking at their electronic devices surreptitiously” respectively. White faculty described negative emotional behavior as disrespect and did not report negative emotional behavior. Examples of disrespect shared by white faculty participants included “I have heard one faculty member openly criticize the accomplishments of another,” and “Student not attending class for weeks or responding to emails later demanding course extensions.”

Poor communication was another commonly described experience for both nonwhite and white participants. Nonwhite students described poor communication as “Lack of communication, not answering emails” compared to white student participants describing poor communication as “Professor not responding to emails making it difficult to prepare for exams.” Nonwhite faculty described communication as “One student's rudeness” compared to white faculty participants who described poor communication as “rude student comments and gestures about class assignments.”

Witnessing Incivility

Faculty Perspectives

A total of 182 participants (29 faculty and 153 students) described experiences of witnessing incivility. Faculty reported experiences witnessing incivility with other faculty across four EI domains including the emotional self-control, influence, communication, and service orientation competencies. Reported examples within the self-management domain, specifically the emotional self-control competency included disrespect described as “I have witnessed another instructor threaten students with failing grades if something is not done to their requirements. Eye-rolling, uncaring emails, and threatened grades for a student that just delivered a baby” and “The faculty member openly and publicly insulted a student for having an older edition of the text, telling her that it was only $50 for the right one. It was more than that, and $50 adds up for many students.” Faculty reported experiences within the relationship management domain within the influence competency were described as power. One faculty participant described power as “A tenured faculty member used influence to change professors in an uncivil way. Had no conversation with the professor, just believed low performing students.” Faculty reported witnessing poor communication described as “I received a complaint of a faculty member not replying to emails or phone calls for over a week.” Experiences related to service orientation were explained as poor professional performance described as “I sometimes have a hard time getting students to stay on track during group activities. Rather than call them out over and over, I often just ignore it.”

Most of the experiences witnessed by faculty involved students. Experiences related to students ranged across six EI competencies including emotional self-control, initiative, influence, communication, service orientation, and organizational awareness. Experiences associated with emotional self-control included disrespectful behavior described as “I've received rude comments from students about an assignment not being graded quickly when they turned in the assignment after the due date.” Experiences related to initiative were reported as inattention described as “I had three students who thought they knew how to teach better than the instructors/professors. They were rude in class, always on their phones/computers, and they made rude comments. This is very rare however.” Influence related experiences were associated with power described as “a student verbally implied in front of the class that her low scores on the test were due to how myself and my co-teacher taught the content.” Challenges with communication were described as, “students not responding to e-mails about courses.”

Student Perspectives

Students also reported witnessing incivility across all four EI domains with many experiences reported related to social awareness and self-management. Most of the experiences witnessing incivility reported by students involved faculty members. Experiences associated with social awareness fell within the service orientation competency and were reported as poor professional performance when faculty were involved and poor academic performance when other students were involved. Poor professional performance was described as “multiple times, professors have had to cancel class and/or make changes to their schedules and syllabi” and “teacher refused to answer question and accused me of not paying attention.” Poor academic performance was described as “a student behind me in class complained about the material” and “student on cell phone during lecture, professor stopped teaching and told them if they had more important things to do instead of listening, they should leave.” Behaviors within the self-management domain involved the emotional self-control competency and were reported as disrespect and negative emotional behavior. Examples of disrespect witnessed by students involving other students included “a student employee thought they were allowed to use the n-word in front of black students/colleagues because they thought because their step-father was black they could. This student continued to use the n-word after several black/African American students told her they were uncomfortable” and “I had a classmate who was frustrated by a professor and would roll their eyes and be passive aggressive.” Student witnessed faculty disrespect was described as “teacher downing me for not knowing information I’m still learning” and “A professor only explained what I was confused about rudely and with a lot of yelling. I wanted to cry. Also told me and other students to get help in the tutoring lab instead of helping us himself.” Negative emotional behavior exhibited by faculty witnessed by students was described as “professor yelled at me when I didn’t understand. Did not want to explain what I was confused about” and “the professor cussed at me for being exactly 3 min late to class. And I mean big time profanity.” Negative emotional behavior displayed by students witnessed by other students was described as “there was one student who got in a verbal altercation with an instructor after the whole class had bad test grades” and “I had a student make a comment to another student about wanting to jump his professor because he made a bad grade on his test. He was very aggressive.” Students also reported witnessing behaviors within the relationship management and self-awareness domains involving both the communication and emotional awareness competencies.

Poor communication from faculty was described as “my professor has not emailed me back in WEEKS. She attends all the classes/ labs just refuses to email me back when I have questions” and “In discussing a grade via email. My complaint was dismissed with a civil but curt response. Further discussion was completely ignored.” Biased behaviors by faculty were also witnessed by students and reported as “When me and my friends were stepping off of the elevator, a professor (male) said “Ladies lingerie to the left”, which made some of us feel uncomfortable” and “An instructor making derogatory comments on a particular religion during class time.” Students also experienced biased behavior from other students which was reported as “student placed a note in my book bag attacking me for being gay and laughed about it to his friends.” Finally, students also witnessed general biased behavior not specifically associated with students or faculty described as “Bending subject material to suite (sic) a particular political party with no relevant connection to the subject being discussed. Making assumptions about another groups of people[’]s political or religious beliefs that which are implied as facts by the lecturer and/or professor. None of these actions occurred with instructors I had but with guest speakers from other departments and/or colleges that were sponsored by the campus.”

Witnessing Incivility by Nonwhite and White Faculty and Students

Experiences witnessing incivility were similarly described for both nonwhite and white participants. Both groups most frequently reported witnessing incivility among faculty and within the self-management and social awareness domains. Competencies that were described included emotional self-control, communication, and initiative within self-management and service orientation and organizational awareness within the social awareness domain.

Nonwhite faculty participants described behaviors within the emotional self-control domain as negative emotional behavior and disrespect. Examples of negative emotional behavior and disrespect from nonwhite faculty participants included, “I have had students in both my fall and spring classes who were uncivil. One slammed the door and shoved a library cart after she got a bad grade. The next semester another student used his sister to send me intimidating emails because I warned him he had missed too many days of class” and “…I was involved via an the (sic) email trail and it was terrible and thus I stepped [in] to HELP the student because that was the right thing to do. The student is [a] higher education customer and every leader should practice servanthood; the communication was terrible and very unprofessional.” White faculty participants also described emotional self-control as negative emotional behavior, disrespect, but also included integrity. Examples of negative emotional behavior and disrespect from white faculty included “Students sometimes impulsively send emotional (angry, upset) emails when they do not receive, they grade they believe they should have” and “students climbing over tables to leave class the clock moment class ended, but not before I finished talking and dismissed them” respectively. Integrity was described as “Student consistently lying (medical appointments for self or her mother) about why she will be absent from class that involved a mandatory test. (Discovered after discussing with other faculty that this behavior was being utilized across several courses and the student was using different scenarios for the same day.)”.

Primary Causes of Incivility in Higher Education

Faculty Perspectives

Overall, a total of 333 participants (52 faculty and 281 students) reported a range of reasons for incivility in higher education across all four EI domains. Reasons provided by faculty were most often categorized within the self-management domain including the emotional self-control competency followed by the relationship management domain including three competencies (influence, developing others, and communication). While students most often reported reasons within the relationship management domain including four competencies (influence, communication, developing others, teamwork and collaboration) followed by the self-management domain including the emotional self-control competency. Faculty also reported reasons within the social awareness domain including two competencies (service orientation and empathy) and the self-awareness domain including three competencies (emotional awareness, self-motivation, and accurate self-assessment). Students also reported reasons within the social awareness domain including the same competencies as faculty as well as the organizational awareness competency. Causes reported by students within the self-awareness domain aligned with competencies reported by faculty and included self-confidence as an additional competency. Both faculty and students most frequently cited general causes of incivility that were not specifically related to student or faculty behavior.

Faculty reported four behaviors including stress, negative emotional behavior, disrespect, and lack of respect as potential reasons for incivility within the emotional self-control competency. Examples of stress were described as “I think that right now much of it is due to COVID-19, and all the unknowns. You add in the racial and political unrest, and it creates a very stressful environment we are all functioning in” and “outside stress and anxiety leaking into the academic environment.” It is important to note that COVID and pandemic were not routinely mentioned across faculty or student responses as causes of incivility. Negative emotional behavior was reported as “regarding student incivility, I believe the cause to be a sense of entitlement. Regarding faculty incivility, I believe the cause is the extremely high workload and attendant feelings of stress and burnout” and “People's personal distress. Most of the time when people lash out at others it's because they're unhappy with their own lives/situations.” Disrespect was described as “a lack of respect for others and the belief that one is always correct” and “lack of respect for others."

Within the relationship management domain, faculty reported power as the cause for incivility within the influence competency. Power was described as “General one-upmanship. ‘I’m more woke than you,’” and “arrogance,” and “power mongering,” and “students seem to have adopted bullying and threatening to ruin teachers’ reputations over grades rather than taking responsibility. In 15 years, I’ve had two or three instances, but it’s becoming more wide-spread.” Lack of experience and lack of awareness were reported by faculty as potential causes within the developing others competency. Faculty described these behaviors as “Lack of engagement, acknowledgment, and awareness of available resources for managing relationships and expectations,” “lack of awareness,” and “poor parenting not leading students to have respect for others.” Another reason reported by faculty included poor communication which was described as “lack of communication,” “varied approaches to professional communication and interactions,” and “unclear expectations.” Within the social awareness domain, examples of service orientation and empathy were described by faculty participants as lack of accountability and a lack of empathy respectively. Lack of accountability was described as “No accountability for faculty or students. Also, faculty are not consistent in modeling proper behaviors” and “lack of expectations, poor accountability.” Lack of empathy was described as “Some people do not think about how certain behavior would affect them if they were the one targeted” and “While many will say they understand, until you have been in that situation, you cannot understand.”

Student Perspectives

Power was a behavior described frequently by student participants within the relationship management domain. Examples of power provided by student participants included “abuse of power,” “I think if anyone exhibits incivility, it's because of a feeling of entitlement, whether that be they feel they're due respect or exceptions to the rules,” and “Abuse of power, ‘fed up’ with unjust[ice]s that are out of your control, attempting to take care of a problem with no results or assistance.” Lack of experience or lack of awareness were behaviors students described within the developing others competency. Student participants described lack of experience as “The environment in which the uncivil individual was raised in,” “immature,” and “Not being in the real world enough.” Lack of awareness was described as “lack of education and awareness,” “ignorance,” and “lack of personal awareness.” Behaviors within the teamwork and collaboration competency were described as lack of relationships and negative interpersonal skills. Lack of relationship examples included “Online cohort with a higher number of students makes it impossible to develop personal relationships.” Examples of negative interpersonal skills included “not being understanding of each other,” “teacher/student issues,” and “people do not think of others when they do something.”

Students also described reasons related to emotional self-control within the self-management domain. Behaviors described related to emotional self-control included stress, negative emotional behavior, disrespect and lack of respect. Stress was described as “In my personal opinion I believe the main cause is due to stress,” “students being stressed or not wanting to be in school,” and “overwhelmed professors or students. High stress makes people react differently.” Examples of disrespect and lack of respect included “disrespect and insensitivity,” and “lack of respect for others” respectively. Negative emotional behavior was described by students as “ignorance and selfishness,” “people are rude,” and “people who cannot control themselves.”

Social awareness was the next most reported domain including behaviors within the organizational awareness, service orientation and empathy domains. Organizational awareness was described by students as a lack of clear expectations. Some examples provided by students included “lack of professionalism expectations,” “differences in standards, no objective standard of civility for the school,” and “misaligned priorities.” Poor professional performance, poor academic performance and lack of accountability were the three themes that aligned with the service orientation competency. Examples of poor professional performance include “I feel the primary reason or cause for incivility in higher education is the lack of professionalism,” “professors aren't held accountable for their actions,” and “think some teachers don’t like to help students much. They expect you to adequately teach yourself what they miss in class and it adds a lot of stress.” Poor academic performance was described by students as “lack of discipline for actions,” “lack of consequences, and value in the higher education environment,” and “lack of accountability.” Lack of empathy within the empathy competency was also reported by students and described as “people not having patience with one another,” “lack of empathy toward others,” and “I think the primary reason/cause for incivility is unwillingness to understand or to see another perspective.”

The final domain reported by students was self-awareness which included responses across four competencies (emotional awareness, self-motivation, accurate self-assessment, self-confidence). Bias was the behavior used to describe emotional awareness. Students reported examples of bias as “old age,” “racism,” “politics,” “ignorance and sometimes prejudice,” and “I feel like so much of it has to do with biases that people may not recognize that they have against certain groups of people.” There were several behaviors reported within the self-awareness domain including apathy, boredom, and no interest. Examples of apathy included “lack of personal engagement,” “not wanting to be in school,” and “lack of care.” Boredom was described a “boredom” while no interest was described as “For students, a lot of what it takes to get a degree contributes nothing to the degree itself or the career one hopes to use the degree for. These ‘enrichment’ activities often end up just wast[ing] students' time and money, especially when given the testimony of recent alum who had to endure barrage after barrage of useless information.” Poor self-confidence was reported by students as “insecurities in oneself.” Ego was also described as “typically egos get in the way of professionalism” which aligned with the accurate self-assessment competency.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the experiences of students and faculty both as recipients and witnesses of incivility in higher education, and the student and faculty perceptions of the primary cause of incivility in higher education. Employing the Incivility in Higher Education Revised (IHE-R) survey, the findings support previous research that incivility in higher education continues to be an issue (Knepp, 2012). Using the revision of Clark’s Incivility model by overlaying Goleman’s EI domains, this study provides a new insight on the causes of incivility in higher education.

While Clark’s Incivility model identifies the causes of incivility as feelings of superiority in faculty and entitlement in students, Goleman’s EI domains allow us to translate those innate, individual feelings into defined skills (or lack of skills) that influence behaviors. In this study, faculty respondents reported experiencing incidences of behaviors that lacked self-management and had poor relationship management. Goleman (1995) defines self-management as “controlling or redirecting one’s emotions.” Closely tied to self-management is relationship management, which Goleman (1995) defines as “having self-awareness and awareness of others’ emotions, the using that knowledge to successfully manage interactions.” Previous research identified contributing factors that lead to inability to control emotions in civil ways (Lashley & DeMeneses, 2001; Mohammadipour et al., 2018). When these EI dysregulated behaviors are applied to the revised Clark and Goleman model, the point on the continuum between the dance of civility and the dance of incivility skews left, marching toward incivility. Student respondents also reported experiencing incidences of behaviors that were categorized by lack of self-management, as well as lack of social awareness. Goleman (1995) defines social awareness as “the ability to identify emotions of others and read situations appropriately.” In our model, it is not enough to rein in negative feelings of superiority and entitlement, but it is necessary to exercise empathy, compassion, and respect, which all demand social awareness competencies. Interestingly, faculty reported the most incidences in the domain of regulation (self-management and relationship management), while students included the domain of awareness (social awareness). Faculty and students each reported experiencing incivility more with faculty than students.

Faculty and students also responded to incidences of witnessing uncivil behavior. Faculty reported witnessing behaviors mostly involving students. The domains of regulation and awareness were most often witnessed. A lack of emotional self-control was witnessed by faculty in both students and faculty. Research by Black et al. (2011), Boice (1996), Clark (2009) and Morrissette (2001) suggest that creating an engaging learning environment can promote civility. Our student responses suggest that such engagement may recognize and enhance the social awareness dimension of everyone in the classroom and thereby increase organizational awareness, service orientation, and empathy among all involved. This finding is consistent with previous research that supports the value of social and emotional learning (SEL) (Gutierrez & Gutierrez, 2019; McInerney & McKlindon, 2014). Social and emotional learning is integrated into practiced behaviors through active teaching and role modeling. Behaviors commonly associated with SEL align with EI behaviors.

Students in this study reported poor professional performance when faculty “cancel class” or “refused to answer questions.” Such examples of unprofessionalism among faculty in positions of authority in the classroom fail to recognize the disproportionate emotional impact on the students. These behaviors, when placed on the modified incivility model, contribute to the culture of incivility in the classroom by failing to demonstrate empathy or respect for everyone in the academic environment.

Previous studies suggest the importance of intentional civil classroom practice. Before incivility can be addressed in the classroom, the causes need to be identified. Behaviors such as “stress” and “disrespect” were identified by faculty, and “power” identified by students. Faculty responses were focused on self-management, while student responses focused on relationship management. This study brings to light the roles that faculty and students see each other play in the classroom. The faculty want students who have an attitude of respect but see them as having attitudes of entitlement that give them license to act on their emotions. Students want faculty who have attitudes of compassion, but instead see attitudes of superiority.

Psychologist Nathaniel Branden (1998) wrote that “[t]he first step toward change is awareness. The second step is acceptance (p. 162).” The modification of Clark’s Incivility in Higher Education Revised (IHE-R) survey can help faculty and students become aware how their own EI and behaviors contribute to the culture of their classroom and to take the first step needed to change the dance of incivility to one of civility.

Conclusion

At the inception of this study, the researchers did not intend to explore incivility in higher education during a global pandemic, nor during the height of modern social unrest. Interestingly, these two looming societal shifts were minimally mentioned in the qualitative data for this study. Our communities were experiencing unprecedented community health concerns and social division and unrest that was unfamiliar to many communities, yet the respondents in this study remained focused on the basic civil treatment of others. They wanted to be treated with positive regard, kindness, courtesy, and respect by the members of their educational community.

This study adapted Clark’s Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education as the overarching framework and added Goleman’s EI domains (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management) as thematic context to the qualitative data. While Clark’s model explains one-on-one encounters with incivility, this study found that individuals could respond civilly to situations in the academic environment only when all parties demonstrated a broader ability to recognize, manage, and interact with complex social and power dynamics among participants, bystanders, and institutional structures, such as rank and tenure. Despite Cahyadi et al.’s (2021) claim that the locus of control was not protective in managing classroom incivility, we believe that a refined approach to establishing locus of control through using Goleman’s EI domains has value. Goleman’s domains of self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness accentuate the individual’s locus of control and center on an individual’s ability to regulate personal behaviors in response to events and people in the environment. His final domain, relationship management, is likely where the real magic will happen in addressing incivility in higher education. Relationship management is a reciprocal process that ebbs and flows either in harmony or discord. In the academic setting, the faculty can set the tone for this metaphorical dance through role modeling, setting expectations, inviting relevant discussion, and holding accountable participants in the learning environment.

The results of our study suggest that there is a relational solution to academic incivility. Structured interprofessional student and faculty focus groups to identify antecedents to academic civility is an essential first step. By crafting a shared taxonomy, the academic stakeholder can design a path forward for a civil teaching and learning environment. Additionally, we believe that implications from this study may guide future research regarding faculty training for creating civil environments for learning. This framework can be used to lay a path forward to finding a solution to the chronic incivility that plagues higher education.

Limitations

It is important to note the recruitment period for this study occurred amid the global COVID-19 pandemic which forced many faculty and students to transition quickly to teaching and learn remotely. The rapid transition to remote learning paired with the need for the prolonged timeline for remote teaching and learning in settings that were previously face-to-face caused tremendous burden to both faculty and students potentially influencing participant responses. Researcher bias is always a risk within qualitative research, strategies to mitigate that risk within this study included independent coding of data by three team members with consensus for final coding and themes by the entire research team. Finally, because participants were asked to self-report data as part of a larger survey there is also a risk response bias and self-selection bias.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Lynda Davis for her assistance and support throughout the project.

Authors' Contributions

Tracy Hudgins – Primary investigator, co-author (tracyahudgins@gmail.com). Diana Layne – Co-investigator, co-author, statistical analysis. Celena E. Kusch – Co-investigator, co-author. Karen Lounsbury – Co-investigator, co-author.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of South Carolina Upstate Office of Institutional Equity, Inclusion, and Engagement.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of South Carolina (Columbia) affirmed this as an Exempt Study Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable; Exempt Study.

Consent for Publication

Include appropriate statements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflicts of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alberts HC, Hazen HD, Theobald RB. Classroom incivilities: The challenge of interactions between college students and instructors in the US. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. 2010;34:439–462. doi: 10.1080/03098260903502679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ausbrooks AR, Jones SH, Tijerina MS. Now you see it, now you don’t: Faculty and student perceptions of classroom incivility in a social work program. Advances in Social Work. 2011;12:255–275. doi: 10.18060/1932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Q., Liu, S., & Kishimoto, T. (2019). School incivility and academic burnout: The mediating role of perceived peer support and the moderating role of future academic self-salience. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bassett, B. S. (2020). Better positioned to teach the rules than to change them: University actors in two low-income, first-generation student support programs. Journal of Higher Education, 91(3), 353–377. 10.1080/00221546.2019.1647581

- Black LJ, Wygonik ML, Frey BA. Faculty-preferred strategies to promote a positive classroom environment. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 2011;22:109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund W, Rehling D. Student perceptions of classroom incivility. College Teaching. 2010;58(1):15–18. doi: 10.1080/87567550903252801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boice B. Classroom incivilities. Research in Higher Education. 1996;37(4):453–486. doi: 10.1007/BF01730110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boysen GA. Teacher responses to classroom incivility: Student perceptions of effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology. 2012;39(4):276–279. doi: 10.1177/0098628312456626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branden, N. (1998). Self-esteem every day: Reflections on self-esteem and spirituality. Simon and Schuster.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(1):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner H. How do we “dis” students? A model of (dis)respectful business educator behavior. Journal of Management Education. 2004;28:319–334. doi: 10.1177/1052562903252656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caboni TC, Hirschy AS, Best JR. Student norms of classroom/m decorum. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 2004;99:59–66. doi: 10.1002/tl.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, H., Mappadang, A. (2021). Workplace and classroom incivility and learning engagement: The moderating role of locus of control. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(4). 10.1007/s40979-021-00071-z

- Chukwuorji JC, Ituma EA, Ugwu LE. Locus of control and academic engagement: Mediating role of religious commitment. Current Psychology. 2018;37(4):792–802. doi: 10.1007/s12144-016-9546-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C., Barbosa-Leiker, C., Gill, L., & Nguyen, D. (2015). Revision and psychometric testing of the Incivility in Nursing Education (INE) Survey: Introducing the INE-R. The Journal of Nursing Education, 54, 306–315. 10.3928/01484834-20150515-01 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clark CM. The dance of incivility in nursing education as described by nursing faculty and students. Advances in Nursing Science. 2008;31:E37–E54. doi: 10.1097/01.ans.0000341419.96338.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM. Faculty and student assessment of and experience with incivility in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2008;47(10):458–465. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20081001-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C. M. (2009). Faculty field guide for promoting student civility in the classroom. Nurse Educator, 34(5), 194–197. 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181b2b589 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clark CM, Springer PJ. Thoughts on incivility: Student and faculty perceptions of uncivil behavior in nursing education. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2007;28(2):93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SF, O’Brien JG, Gadd MG, Ristuccia J, Wallace DL, Gregory M. Helping traumatized children learn. Massachusetts Advocates for Children; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby SD. An ecological perspective on emerging trauma-informed teaching practices. Children & Schools. 2015;37(4):223–230. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdv027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Gutierrez, D., & Gutierrez, A. (2019). Developing a trauma-informed lens in the college classroom and empowering students through building positive relationships. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 12(1), 11–18. 10.19030/cier.v12i1.10258

- Henderson, B. B. (2009) Introduction: The work of the people's university. Teacher-Scholar: The Journal of the State Comprehensive University, 1. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/ts/vol1/iss1/2

- Holton SA. It’s nothing new! A history of conflict in higher education. New Directions for Higher Education. 1995;92:11–18. doi: 10.1002/he.36919959204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins T, Layne D, Kusch C, Lounsbury K. An analysis of the perceptions of incivility in higher education. Journal of Academic Ethics. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10805-022-09448-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): Toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184. 10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

- Knepp KAF. Understanding student and faculty incivility in higher education. Journal of Effective Teaching. 2012;12(1):32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp JP, Finney SJ. Linking academic entitlement and student incivility using latent means modeling. Journal of Experimental Education. 2013;81(3):322–336. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.727887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley FR, De Meneses M. Student civility in nursing programs: A national survey. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2001;17:81–86. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2001.22271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, F. M. (2017). The contours of free expression on campus: Free speech, academic freedom, and civility. Liberal Education, 103(2), 14–21. Retrieved from http://www.aacu.org/publications/index.cfm

- Lim, J., & Richardson, J. C. (2021). Predictive effects of undergraduate students’ perceptions of social, cognitive, and teaching presence on affective learning outcomes according to disciplines. Computers & Education, 161. 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104063

- Lippmann S, Bulanda RE, Wagenaar TC. Student entitlement: Issues and strategies for confronting entitlement in the classroom and beyond. College Teaching. 2009;57(4):197–204. doi: 10.1080/87567550903218596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luparell S, Frisbee K. Do uncivil nursing students become uncivil nurses? A national survey of faculty. Nurse Education Perspectives. 2019;40(6):322–327. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 9(3), 3351. http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/3354

- McInerney, M., & McKlindon, A. (2014). Unlocking the door to learning: Trauma-informed classrooms & transformational schools. Education Law Center of Pennsylvania.

- Meyers SA, Bender J, Hill EK, Thomas SY. How do faculty experience and respond to classroom conflict? International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. 2006;18:180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. N. S. (2017). Building a community: Using regional comprehensives’ peer groups to define the sector. Alliance for Research on Regional Colleges. https://www.regionalcolleges.org/project/building-a-community

- Mohammadipour M, Hasanvand S, Goudarzi F, Ebrahimzadeh F, Pournia Y. The level and frequency of faculty incivility as perceived by nursing students of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2018;11(4):334–342. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette P. Reducing incivility in the university/college classroom. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning. 2001;5(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen C, Bettez S, Wilson C. Fostering community life and human civility in academic departments through covenant practice. Educational Studies. 2011;47(3):280–305. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2011.573608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, C. R., Bartels, L. K., & Bucy, J. (2009). Predicting and curbing classroom incivility in higher education. College Student Journal, 43, 74–85. Retrieved from http://www.projectinnovation.biz/csj.html

- Nilson, L. B., & Jackson, N. S. (2004, June). Combating classroom misconduct (incivility) with Bills of Rights. Paper presented at the International Consortium for Educational Development, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research (Vol. 2). Jossey-Bass.

- Rawlins L. Faculty and student incivility in undergraduate nursing education: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Education. 2017;56(12):709–716. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20171120-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehling DL, Bjorklund WL. A comparison of faculty and student perceptions of incivility in the classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 2010;21(3):73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 1990;9:185–211. doi: 10.2190/dugg-p24e-52wk-6cdg. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. R., and Biag, M. (2016). The changing ecology of U.S. higher education: An organization field perspective. In B. E. Popp, & C. Paradeise, (Eds.). The university under pressure (pp. 25–51). Emerald Publishing Limited. 10.1108/S0733-558X20160000046002

- Wagner B, Holland C, Mainous R, Matchum W, Li G, Luiken J. Differences in perceptions of incivility among disciplines in higher education. Nurse Educator. 2019;44(5):265–269. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack, L. (2020) Non-traditional students at public regional universities: A case study. Teacher-Scholar: The Journal of the State Comprehensive University, 9(1). https://scholars.fhsu.edu/ts/vol9/iss1/1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.