Abstract

Arterial and venous thrombotic events in COVID-19 cause significant morbidity and mortality among patients. Although international guidelines agree on the need for anticoagulation, it is unclear whether full-dose heparin anticoagulation confers additional benefits over prophylactic-dose anticoagulation. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of heparin full-dose anticoagulation in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. We searched Pubmed/Medline, EMBASE, Clinicaltrials.gov, medRxiv.org and Cochrane Central Register of clinical trials dated up to April 2022. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing full-dose heparin anticoagulation to prophylactic-dose anticoagulation or standard treatment in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients were included in our pooled analysis. The primary endpoint was the rate of major thrombotic events and the co-primary endpoint was the rate of major bleeding events. We identified 4 studies, all of them multicenter, randomizing 2926 patients. Major thrombotic events were 23/1524 (1.5%) in full-dose heparin anticoagulation versus 57/1402 (4.0%) in prophylactic-dose [relative risk (RR) 0.39; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25–0.62; p˂0.01; I2 = 0%]. Clinical relevant bleeding events occurred in 1.7% (26/1524) among patients treated with heparin full anticoagulation dose compared to 1.1% (15/1403) in prophylactic-dose group (RR 1.60; 95% CI 0.85–3.03; p = 0.15; I2 = 20%). Mortality was 6.6% (101/1524) versus 8.6% (121/1402) (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.33–1.19; p = 0.15). In this meta-analysis of high quality multicenter randomized trials, full-dose anticoagulation with heparin was associated with lower rate of major thrombotic events without differences in bleeding risk and mortality in hospitalized non critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Study registration PROSPERO, review no. CRD42022301874.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11239-022-02681-x.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Heparin, LMWH, Anticoagulant, Hospital mortality, Intensive care

Highlights

Full anticoagulation reduces thrombosis in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients

Full anticoagulation does not increase bleeding in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19

We present findings of meta-analysis of multicenter randomized controlled trials

Anticoagulation with full-dose heparin/LMWH is overall beneficial to COVID-19 patients

Randomized evidence supports the use of full-dose heparin/LMWH in COVID-19 patients

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection lead to death over 6 million of people worldwide and it represents a challenge for all healthcare systems [1] .

There is increasing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes immune-mediated micro-thrombosis due to endothelial injury and vascular inflammation, which has been linked to development of COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple organ failure. In particular, several studies suggested that immunothrombosis has a key role in hypoxemic respiratory failure, the most common presentation of severe COVID-19. The term MicroCLOTS (Microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome) has been suggested to describe this particular type of ARDS [2] . Therefore, it has been hypothesized that early initiation of anticoagulation may prevent further disease progression. However, the best timing of initiation of anticoagulation remains to be determined. Furthermore, it is unclear whether full-dose therapeutic anticoagulation may confer additional advantage over a prophylactic regimen.

Prior clinical trials [3, 4] and meta-analyses [5, 6] showed contrasting results in terms of clinical benefits of anticoagulation. This heterogeneity in findings is probably related to the inclusion in meta-analyses of non- randomized controlled trials (RCTs), inclusion of patients with highly variable disease severity (from outpatients to patients requiring ICU admission) and lack of data from the most recent trials.

We therefore conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of available RCTs to investigate efficacy and safety of full-dose anticoagulation with heparin in hospitalized, non-critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [7] and Cochrane methodology [8] . The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022301874).

The review question was designed with the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design) framework: Population: hospitalized, non-critically ill COVID-19 patients; Intervention: full-dose anticoagulation with heparin; Comparison: no full-dose anticoagulation (including standard treatment, placebo, or prophylactic-dose anticoagulation); Outcome: any of the primary and secondary outcomes as listed below; Study design: randomized controlled trials.

Search strategy and study selection

Two trained, independent authors searched PubMed/Medline, Embase, medRxiv.org, the Cochrane Central Register of clinical trials and Clinicaltrials.gov (last updated April 2022) for appropriate studies. In addition, references of review articles and included RCTs were screened to identify additional studies. Studies were only included if there was agreement between the two authors and disagreements were resolved by discussion involving a third reviewer. No language restrictions were applied. We designed a search strategy to include RCTs comparing therapeutic-dose of heparin anticoagulation to heparin prophylactic-dose utilization in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Inclusion criteria were: (1) randomized trials, (2) that enrolled hospitalized, non-critically ill adults (age ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of respiratory SARS-CoV-2 viral infection (RT-PCR or antigen testing) irrespective of age, gender or ethnicity, (3) comparing full-dose anticoagulation with heparin versus no full-dose anticoagulation. Exclusion criteria were: studies enrolling critically ill patients (defined according to Authors of each individual study), pediatric patients, non-hospitalized patients, a non-parallel design, a non-randomized or quasi-randomized study design. We performed our search strategy on PubMed and Embase in advanced mode with Boolean operators (all search strategies are available in the Supplementary material).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of our study was the rate of major thrombotic events, defined according to Authors of each individual study. Co-primary outcome was rate of major bleeding events, defined according to the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [9] .

Secondary outcomes were: all-cause mortality at the longest follow-up available; need for mechanical ventilation; a composite of death or need for mechanical ventilation; need for ICU admission; a composite of death or need for ICU admission.

Data abstraction and risk of bias assessment

Two trained authors separately abstracted data on study sample size patients, treatment type and dose, major thrombotic events (arterial and venous), clinical relevant bleeding events, need of ICU admission data (if this was missing we used intubation rate), need of intubation or any mechanical ventilation, and mortality at the longest follow-up available. We contacted by e-mail authors of the studies to obtain additional from investigators when not available in manuscripts (Supplementary material Table 1).

Risk of bias of included trials was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and using the recommended version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of- bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [10] . We assessed separately the fours items and we evaluated the potential risk of bias as “Low”, “Some concerns” or “High” for each study. RCTs included in the final analysis were assessed as high quality with low risk of bias. Small study effect and publication bias were assessed for primary endpoint by visual inspection funnel plot. Funnel plot asymmetry was assessed with Egger’s linear regression method performed using STATA 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Statistical analysis

All computations related to the outcomes were performed with RevMan 5.4.1 (Review Manager, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Pooled risk ratios (RRs) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes using the Mantel–Haenszel statistical method and we presented RR with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For pooled outcome analyses, a p value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle whenever possible. For trials which did not report intention-to-treat data we used data as available in the manuscript.

Heterogeneity analysis

Heterogeneity was firstly assessed through visual inspection of the forest plots, and then estimated using the I2 statistic. Statistical heterogeneity hypothesis was tested using RevMan 5.4.1 (Review Manager, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and we considered an I2 of 25%, 26–50%, and > 50% as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Fixed-effects model was used in case of low statistical heterogeneity, while random-effects model was used in case of moderate-to-high statistical heterogeneity.

Results

Study characteristics

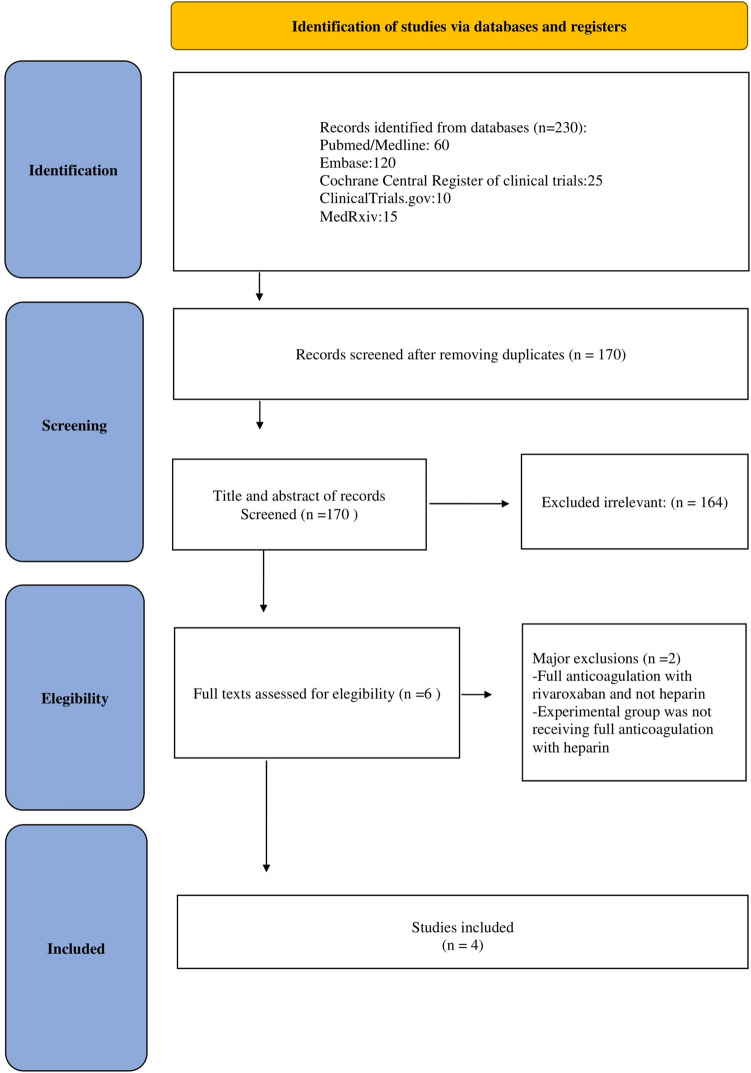

Our database and reference scanning initially yielded a total of 230 articles (Fig. 1). A total of 4 studies randomizing 2926 patients (1524 receiving full-dose heparin anticoagulation and 1402 receiving control treatment) were included in the analysis [11–14] . All studies were multicenter and had prophylactic-dose anticoagulation (administered according to local practice and guidelines, and clinician judgement) as control treatment.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

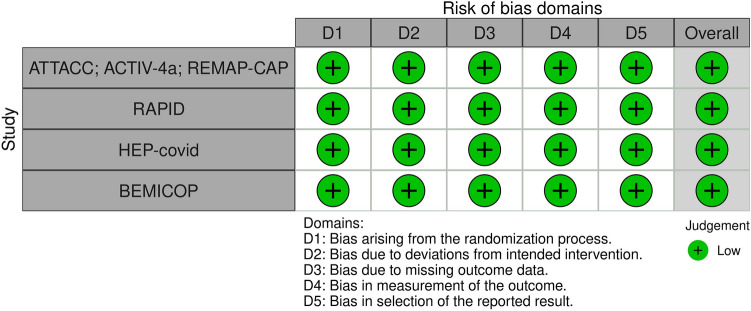

In terms of populations the trials enrolled patients from 12 different countries in 4 continents and all included studies were published in 2021 (Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the included studies). Overall, risk of bias analysis showed that all included trials were at low risk of bias [15] (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the included studies

| Study | No patients treatment group | No patients control group | Therapeutic-dose anticoagulation (drug and dosage) | Prophylactic-dose anticoagulation (drug and dosage) | Country | Study design and enrollment period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTACC; ACTIV-4a; REMAP-CAP [11] | 1180 | 1046 | LMWH dosed according to patient weight and creatinine clearance according to local practice and policy: enoxaparin starting at 1 mg/kg twice daily or enoxaparin starting at 1.5 mg/kg once daily; dateparin: 100 U/kg twice daily or starting at 200 U/kg once daily; tinzaparin 175 anti-Xa units/kg once daily. UFH continuous intravenous administration per local protocol | LMWH dosed according to patient weight and creatinine clearance according to local practice and policy: enoxaparin 40 mg once daily, up to and including (a) 0.5 mg/kg twice daily or (b) 40 mg twice daily; dalteparin 5000 units once daily or 5000 units twice daily; tinzaparin up to and including (a) 75 anti-Xa units/kg once daily or (b) 4500 units once daily; tinzaparin: 4500 units twice daily. UFH 5000 units twice or three times daily or 7500 units three times daily or 10,000 units twice daily | USA, Canada, UK, Brazil, Mexico, Nepal, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain | mRCT (April 21, 2020 to January 22, 2021) |

| BEMICOP [12] | 32 | 33 | bemiparin 7500 IU qd if bwt between 50 and 70 kg; bemiparin 10,000 IU qd if bwt between 70 and 100 kg; bemiparin 12,500 IU qd if bwt > 100 kg | bemiparin 3500 IU sc qd | Spain | mRCT (October 2020 to May 2021) |

| HEP [13] | 84 | 86 | enoxaparin 1 mg/kg sc bid if CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2; enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg sc bid if CrCl 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 | UFH up to 22,500 IU sc; enoxaparin 30–40 mg sc qd/bid; dalteparin 2500–5000 IU sc qd. UFH treatment dose iv if CrCl ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 | USA | mRCT (May 8, 2020 to May 14, 2021) |

| RAPID [14] | 228 | 237 | enoxaparin 1 mg/kg sc bid or enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg sc qd or dalteparin 100 IU/kg sc bid or dalteparin 200 IU/kg sc qd or tinzaparin 175 IU/kg sc qd or UFH iv titrate to institution specific anti-Xa or aPTT values* if CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ˂ 40; enoxaparin 1 mg/kg sc bid or dalteparin 100 IU/kg sc bid tinzaparin 175 IU/kg sc qd or UFH iv titrate to institution specific anti-Xa or aPTT values* if CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ≥ 40. UFH iv titrate to institution specific anti-Xa or aPTT values* or LMWH per hospital protocol taking BMI into consideration if CrCl ˂30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | enoxaparin 40 mg sc qd or or dalteparin 5000 IU sc qd or tinzaparin 4500 IU sc qd or fondaparinux 2.5 mg sc qd or UFH 5000 UI iv bid/tid if CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ˂ 40; enoxaparin 40 mg sc bid or dalteparin 5000 IU sc bid or tinzaparin 9000 (± 1000) UI sc qd or UFH 7500 UI sc tid if CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ≥ 40; UFH 5000 UI iv bid/tid if CrCl ˂30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ˂ 40 or LMWH per hospital protocol taking BMI into consideration as above. UFH 7500 UI sc tid tid if CrCl ˂30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and bmi ˃40 or LMWH per hospital protocol taking BMI into consideration as above | USA, Canada,Ireland, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates | mRCT (May 29, 2020 to April 12, 2021) |

No number, QD quaque die; BID bis in die; TID ter in die, iv intravenous, bwt body weight, UFH unfractionated heparin, CrCl creatinine clearance, BMI body mass index, LMWH low molecular weight heparin, mRCT multicenter randomized controlled trial

*Initial bolus dose determined by sites, encouraging use of dosing algorithm designed for treatment of venous thromboembolism. UFH anti‐Xa titration was preferred over aPTT if available as achieving a therapeutic aPTT may be challenging in patients with a pro‐inflammatory state such as COVID‐19

Fig. 2.

Traffic plot of RCTs included in the meta-analysis

Quantitative data synthesis

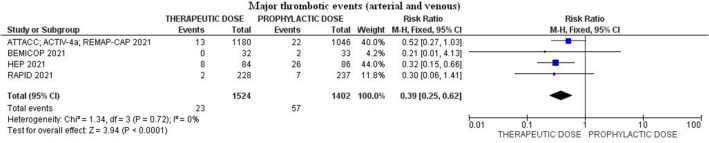

Major thrombotic events (arterial and venous) occurred in 1.5% (23/1524) among patients treated with heparin therapeutic-dose compared to 4.0% (57/1402) in those that received prophylactic-dose [relative risk (RR) 0.39; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25–0.62; p ˂ 0.01; I2 = 0%; Egger’s test p = 0.47] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the rate of major arterial and venous thrombotic events

Sequential removal of each trial did not change magnitude and direction of treatment effect for the primary outcome (lowest RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.16–0.58; p˂0.01; I2 = 0%; removing ATTACC; ACTIV-4a; REMAP-CAP and highest RR 0.45; 95% (CI 0.25–0.83; p = 0.01; I2 = 0%; removing HEP).

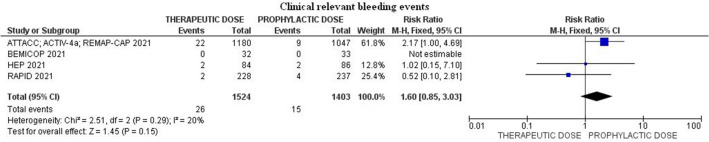

Clinical relevant bleeding events occurred in 1.7% (26/1524) among patients treated with heparin full anticoagulation dose compared to 1.1% (15/1403) in prophylactic-dose group (RR 1.60; 95% CI 0.85–3.03; p = 0.15; I2 = 20%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the rate of clinical relevant bleeding events

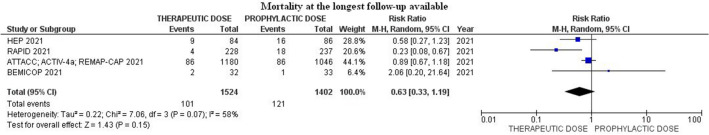

Mortality at the longest follow-up available among patients treated with heparin therapeutic-dose was 6.6% (101/1524) compared to 8.6% (121/1402) in those that received prophylactic-dose (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.33–1.19; p = 0.15; I2 = 58%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the rate of mortality at the longest follow-up available

All secondary endpoints showed a trend in favour of full-dose anticoagulation as reported in Table 2 and Supplementary material Figs. 1–5.

Table 2.

Pooled analysis of studies comparing full-dose heparin anticoagulation to prophylactic-dose anticoagulation

| Outcomes | Events/Total number heparin full anticoagulation (%) | Events/Total number prophylattic anticoagulation (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | I2(%) | Number of included trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Major thrombotic events (arterial and venous) | 23/1524 (1.5%) | 57/1402 (4.0%) | 0.39 (0.25–0.62) | ˂ 0.01 | 0 | 4 |

| Clinical relevant bleeding events | 26/1524 (1.7%) | 15/1403 (1.1%) | 1.60 (0.85–3.03) | 0.15 | 20 | 4 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Mortality at the longest follow-up available | 101/ 1524 (6.6%) | 121/1402 (8.6%) | 0.63 (0.33–1.19) | 0.15 | 58 | 4 |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 157/1493 (10.5%) | 166/1373 (12.1%) | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.18 | 0 | 3 |

| Composite outcome death or mechanical ventilation | 210/1409 (14.9%) | 224/1287 (17.4%) | 0.81 (0.59–1.10) | 0.18 | 43 | 2 |

| Need for ICU admission | 173/1525 (11.3%) | 182/1406 (12.9%) | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | 0.21 | 0 | 4 |

| Composite outcome death or ICU admission | 165/1409 (11.7%) | 177/1287 (13.7%) | 0.86 (0.71–1.05) | 0.14 | 0 | 2 |

ICU intensive care unit, CI confidence interval

Discussion

Key findings

The main finding of our systematic review and meta-analysis is that heparin full-dose anticoagulation treatment (either enoxaparin, bemiparin, other LMWH, or UFH) significantly reduced major thrombotic events in hospitalized non critically ill COVID-19 patients, with no differences in the risk of bleeding events and mortality.

Relationship to previous studies

Few meta-analyses summarized this topic but they included heterogeneous treatment (e.g., RCT on rivaroxaban rather than heparin) and settings (e.g., mixing critically and non-critically ill studies) [16] . In 2021 Reis et al. reported that therapeutic-dose anticoagulation may decrease a composite of any thrombotic event or death with a risk of major bleeding [5] . Similarly, Wills et al. found that full-dose anticoagulation compared to prophylaxis decreased the risk of venous thromboembolism events but increased major bleeding events risk [17] . In another meta-analysis, Sholzberg M. et al.; 2021 found a reduction in the composite outcome of death or invasive mechanical ventilation [odds ratio (OR) 0.77; 95% CI 0.60–0.98], and death or any thrombotic event in moderately ill patients (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.45–0.77) with a nonsignificant increase in major bleeding. We added to their analysis since we identified and included a further RCT [6] . Compared to previous studies, noteworthy aspects of our meta-analysis are the decisions to focus our attention only on full-dose anticoagulation with heparin and to evaluate only non-critically ill patients.

Notably, full-dose anticoagulation in critically-ill patients seems to increase bleeding without being able to improve clinically relevant outcomes. Our meta-analysis can help to improve the management of hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients since it suggests that the minimal non significant increase in bleeding is couterbalanced by an important reduction in thrombotic events with a trend towards a mortality reduction and an improvement in all clinically relevant outcomes.

Our study aims to investigate full-dose anticoagulation with heparin (either enoxaparin, bemiparin, other LMWH, or UFH). There are plausible biological explanations for anti-viral ancillary beneficial properties of heparin and we considered this when planning our systematic review and meta-analysis.

Significance of study findings and what this study adds to our knowledge

Among hospitalized adults with COVID-19 venous thromboembolism (VTE) such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and arterial thromboembolism (ATE) such as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke are common and affects morbidity and mortality [18–21] . Furthermore, patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection are likely subjected to the formation of immune mediated pulmonary micro-clots caused by endothelial injury and vascular inflammation [2] . We decided to focus our attention on non-critically ill patients in the hypothesis that full-dose anticoagulation is likely capable of being an effective prophylaxis against immunothrombotic events and in preventing their progression [22] . If COVID-19 MicroCLOTS are similar to the immune-thrombosis model, they are probably resistant to anticoagulants drugs thus heparin may stop the progression of the coagulation cascade avoiding the increase in thrombi size, but is not able to dissolve clots [23] . This aspect may be an explanation of conflicting results of other previous studies that grouped critical and non-critical patients without distinction. In critically ill patients heparin may not be capable of acting on the advanced state of immunothrombi formation characteristic of MicroCLOTS. This particular thrombosis of microcirculation is likely responsive to anticoagulantion only at an early stage of the disease and the correct timing of anticoagulative regimen may be important to prevent the evolution of lung damage.

Several international guidelines recommend heparin-based anticoagulation therapy in all COVID-19 hospitalized patients [24–29] . Despite all these recommendations, the proper dosage of anticoagulant therapy (prophylactic-dose vs full-dose) and the exact time to start anticoagulants remain research objects [30, 31] . The overall results of our meta-analysis show a trend in favour of benefits of full-dose anticoagulation in hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. It is imperative to note that all clinical benefits of heparin full-dose anticoagulation regarding clinical worsening must be weighted after a careful evaluation of the bleeding risk for each patient and case-by-case considerations are necessary to better balance the thrombotic risk with that of bleeding.

Our results confirm that, within the context of mild-to-moderate illness, hospitalized, non-critically ill COVID-19 patients benefit from heparin full-dose anticoagulation as prevention for major thrombotic events (arterial and venous). On the other hand heparin full-dose anticoagulation may theoretically increase bleeding risk but the effect size is small and the overall effect on survival seems to be beneficial according to our meta-analysis.

In addition to antithrombotic benefits heparin shows anti-inflammatory, and potentially antiviral effects [32, 33] . The molecular mechanisms of these pleiotropic effects are not fully understood. It is reported in scientific literature that LMWH binds with high affinity to IFNγ fully inhibiting the interaction with its cellular receptor. Furthermore, it influences the biological activity of IL-6 by binding either IL-6 or IL-6/IL-6Rα. These molecular interactions are likely the basis of the anti-inflammatory action of LMWH and better clarify its ability to favourably influence conditions such as COVID-19 characterized by overexpression of these chemical mediators [34] . More clinical evidence is without doubt required to better clarify these aspects related to heparin full-dose anticoagulation usage in hospitalized non critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main originality of our study is represented by the high quality and design of the RCTs that we included in the meta-analysis: they were all at low risk of bias. The choice to include only randomized trials allowed us to minimize differences between groups and potential confounders to achieve more transparency and reproducibility. The inclusion of RCTs from different countries and different healthcare realities during a pandemic emergency increases the external validity of the findings. Furthermore, statistical heterogeneity was low in most of the analyses. We are aware that meta-analyses should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than confirmative. Therefore, more adequately powered multicenter RCTs are required before definitive answers on full-dose heparin anticoagulation efficacy and safety can be provided.

Conclusions

Evidence from high-quality randomized trials suggests a significative reduction of major thrombotic events in COVID-19 non-critically ill patients receveing full-dose heparin anticoagulation when compared to propylactic-dose anticoagulation with only a trend towards an improvement in survival.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

EP: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. AB: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Writing—original draft. SF: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft. GF: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—original draft, Supervision. GL: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Data curation, Visualization Writing—original draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 20 April 2022 Edition 88, Emergency Situational Updates

- 2.Ciceri F, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, Colombo S, Landoni G, Ruggeri A, et al. Microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome (MicroCLOTS): an atypical acute respiratory distress syndrome working hypothesis. Crit Care Resusc. 2020;22:95–97. doi: 10.51893/2020.2.pov2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawler PR, Goligher EC, Berger JS, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:790–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goligher EC, Bradbury CA, McVerry BJ, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid 19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:777–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis S, Popp M, Schmid B, et al. Safety and efficacy of intermediate- and therapeutic-dose anticoagulation for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):57. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sholzberg M, da Costa BR, Tang GH, et al. Randomized trials of therapeutic heparin for COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(8):e12638. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Accessed 22 Mar 2019

- 9.Schulman S, Kearon C, The Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ATTACC Investigators. ACTIV-4a Investigators. REMAP-CAP Investigators. Lawler PR, Goligher EC, Berger JS, Neal MD, McVerry BJ, Nicolau JC, Gong MN, Carrier M, Rosenson RS, Reynolds HR, Turgeon AF, Escobedo J, Huang DT, Bradbury CA, Houston BL, Kornblith LZ, Kumar A, Kahn SR, Cushman M, McQuilten Z, Slutsky AS, Kim KS, Gordon AC, Kirwan BA, Brooks MM, Higgins AM, Lewis RJ, Lorenzi E, Berry SM, Berry LR, Aday AW, Al-Beidh F, Annane D, Arabi YM, Aryal D, Baumann Kreuziger L, Beane A, Bhimani Z, Bihari S, Billett HH, Bond L, Bonten M, Brunkhorst F, Buxton M, Buzgau A, Castellucci LA, Chekuri S, Chen JT, Cheng AC, Chkhikvadze T, Coiffard B, Costantini TW, de Brouwer S, Derde LPG, Detry MA, Duggal A, Džavík V, Effron MB, Estcourt LJ, Everett BM, Fergusson DA, Fitzgerald M, Fowler RA, Galanaud JP, Galen BT, Gandotra S, García-Madrona S, Girard TD, Godoy LC, Goodman AL, Goossens H, Green C, Greenstein YY, Gross PL, Hamburg NM, Haniffa R, Hanna G, Hanna N, Hegde SM, Hendrickson CM, Hite RD, Hindenburg AA, Hope AA, Horowitz JM, Horvat CM, Hudock K, Hunt BJ, Husain M, Hyzy RC, Iyer VN, Jacobson JR, Jayakumar D, Keller NM, Khan A, Kim Y, Kindzelski AL, King AJ, Knudson MM, Kornblith AE, Krishnan V, Kutcher ME, Laffan MA, Lamontagne F, Le Gal G, Leeper CM, Leifer ES, Lim G, Lima FG, Linstrum K, Litton E, Lopez-Sendon J, Lopez-Sendon Moreno JL, Lother SA, Malhotra S, Marcos M, Saud Marinez A, Marshall JC, Marten N, Matthay MA, McAuley DF, McDonald EG, McGlothlin A, McGuinness SP, Middeldorp S, Montgomery SK, Moore SC, Morillo Guerrero R, Mouncey PR, Murthy S, Nair GB, Nair R, Nichol AD, Nunez-Garcia B, Pandey A, Park PK, Parke RL, Parker JC, Parnia S, Paul JD, Pérez González YS, Pompilio M, Prekker ME, Quigley JG, Rost NS, Rowan K, Santos FO, Santos M, Olombrada Santos M, Satterwhite L, Saunders CT, Schutgens REG, Seymour CW, Siegal DM, Silva DG, Jr, Shankar-Hari M, Sheehan JP, Singhal AB, Solvason D, Stanworth SJ, Tritschler T, Turner AM, van Bentum-Puijk W, van de Veerdonk FL, van Diepen S, Vazquez-Grande G, Wahid L, Wareham V, Wells BJ, Widmer RJ, Wilson JG, Yuriditsky E, Zampieri FG, Angus DC, McArthur CJ, Webb SA, Farkouh ME, Hochman JS, Zarychanski R. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):790–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcos-Jubilar M, Carmona-Torre F, Vidal R, Ruiz-Artacho P, Filella D, Carbonell C, Jiménez-Yuste V, Schwartz J, Llamas P, Alegre F, Sádaba B, Núñez-Córdoba J, Yuste JR, Fernández-García J, Lecumberri R, BEMICOP Investigators Therapeutic versus prophylactic bemiparin in hospitalized patients with nonsevere COVID-19 pneumonia (BEMICOP Study): an open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(2):295–299. doi: 10.1055/a-1667-7534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, Diab W, Wang J, Khanijo S, Mignatti A, Gianos E, Cohen M, Sharifova G, Lund JM, Tafur A, Lewis PA, Cohoon KP, Rahman H, Sison CP, Lesser ML, Ochani K, Agrawal N, Hsia J, Anderson VE, Bonaca M, Halperin JL, Weitz JI, HEP-COVID Investigators (2021) Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the HEP-COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 181(12):1612–1620. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med 2022;182(2):239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sholzberg M, Tang GH, Rahhal H, AlHamzah M, Kreuziger LB, Áinle FN, Alomran F, Alayed K, Alsheef M, AlSumait F, Pompilio CE, Sperlich C, Tangri S, Tang T, Jaksa P, Suryanarayan D, Almarshoodi M, Castellucci LA, James PD, Lillicrap D, Carrier M, Beckett A, Colovos C, Jayakar J, Arsenault MP, Wu C, Doyon K, Andreou ER, Dounaevskaia V, Tseng EK, Lim G, Fralick M, Middeldorp S, Lee AYY, Zuo F, da Costa BR, Thorpe KE, Negri EM, Cushman M, Jüni P, RAPID trial investigators Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with covid-19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2021;375:n2400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Syn Meth. 2020;2020:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes RD, de Barros-E-Silva PGM, Furtado RHM, Macedo AVS, Bronhara B, Damiani LP, Barbosa LM, de Aveiro-Morata J, Ramacciotti E, de Aquino-Martins P, de Oliveira AL, Nunes VS, Ritt LEF, Rocha AT, Tramujas L, Santos SV, Diaz DRA, Viana LS, Melro LMG, de AlcântaraChaud MS, Figueiredo EL, Neuenschwander FC, Dracoulakis MDA, Lima RGSD, de Souza Dantas VC, Fernandes ACS, Gebara OCE, Hernandes ME, Queiroz DAR, Veiga VC, Canesin MF, de Faria LM, Feitosa-Filho GS, Gazzana MB, Liporace IL, de Oliveira TA, Maia LN, Machado FR, de Matos SA, Conceição-Souza GE, Armaganijan L, Guimarães PO, Rosa RG, Azevedo LCP, Alexander JH, Avezum A, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O, ACTION Coalition COVID-19 Brazil IV Investigators Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (ACTION): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2253–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wills NK, Nair N, Patel K, Sikder O, Adriaanse M, Eikelboom J, Wasserman S. Efficacy and safety of intensified versus standard prophylactic anticoagulation therapy in patients with Covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.03.05.22271947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Cobelli F, Palumbo D, Ciceri F, Landoni G, Ruggeri A, Rovere-Querini P, D'Angelo A, Steidler S, Galli L, Poli A, Fominskiy E, Calabrò MG, Colombo S, Monti G, Nicoletti R, Esposito A, Conte C, Dagna L, Ambrosio A, Scarpellini P, Ripa M, Spessot M, Carlucci M, Montorfano M, Agricola E, Baccellieri D, Bosi E, Tresoldi M, Castagna A, Martino G, Zangrillo A. Pulmonary vascular thrombosis in COVID-19 pneumonia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35(12):3631–3641. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, Endeman H. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(7):1178–1191. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roncon L, Zuin M, Barco S, et al. Incidence of acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;82:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miesbach W, Makris M. COVID-19: coagulopathy, risk of thrombosis, and the rationale for anticoagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:1076029620938149. doi: 10.1177/1076029620938149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sofia R, Carbone M, Landoni G, Zangrillo A, Dagna L. Anticoagulation as secondary prevention of massive lung thromboses in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19: May 2021 update on the use of intermediate intensity anticoagulation in critically ill patients. Blood Adv. 2021 doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Information on COVID-19 Treatment, Prevention and Research. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed 5 Oct 2021

- 30.Giannis D, Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC. Anticoagulant therapy for COVID-19: what we have learned and what are the unanswered questions? Eur J Intern Med. 2022;96:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haider Z, Rajalingam K, Khalid T, Oswal D, Dwarakanath A. Intermediate dose thromboprophylaxis in SARS-CoV-2 related venous thrombo embolism. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:141–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buijsers B, Yanginlar C, Maciej-Hulme ML, de Mast Q, van der Vlag J. Beneficial non-anticoagulant mechanisms underlying heparin treatment of COVID-19 patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102969. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mycroft-West CJ, Su D, Pagani I, Rudd TR, Elli S, Gandhi NS, Guimond SE, Miller GJ, Meneghetti MCZ, Nader HB, Li Y, Nunes QM, Procter P, Mancini N, Clementi M, Bisio A, Forsyth NR, Ferro V, Turnbull JE, Guerrini M, Fernig DG, Vicenzi E, Yates EA, Lima MA, Skidmore MA. Heparin inhibits cellular invasion by SARS-CoV-2: structural dependence of the interaction of the spike S1 receptor-binding domain with heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(12):1700–1715. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Litov L, Petkov P, Rangelov M, Ilieva N, Lilkova E, Todorova N, Krachmarova E, Malinova K, Gospodinov A, Hristova R, Ivanov I, Nacheva G. Molecular mechanism of the anti-inflammatory action of heparin. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10730. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.