Abstract

Platelets have emerged as key inflammatory cells implicated in the pathology of sepsis, but their contributions to rapid clinical deterioration and dysregulated inflammation have not been defined. Here, we show that the incidence of thrombocytopathy and inflammatory cytokine release was significantly increased in patients with severe sepsis. Platelet proteomic analysis revealed significant upregulation of gasdermin D (GSDMD). Using platelet-specific Gsdmd-deficient mice, we demonstrated a requirement for GSDMD in triggering platelet pyroptosis in cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis. GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis was induced by high levels of S100A8/A9 targeting toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Pyroptotic platelet-derived oxidized mitochondrial DNA (ox-mtDNA) potentially promoted neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, which contributed to platelet pyroptosis by releasing S100A8/A9, forming a positive feedback loop that led to the excessive release of inflammatory cytokines. Both pharmacological inhibition using Paquinimod and genetic ablation of the S100A8/A9–TLR4 signaling axis improved survival in mice with CLP-induced sepsis by suppressing platelet pyroptosis.

Subject terms: Cell death, Inflammation, Cell death and immune response, Innate immunity

Su, Chen et al. show that sepsis-derived S100A8/A9 induces GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis via the TLR4/ROS/NLRP3/caspase 1 pathway, leading to the release of ox-mtDNA contributing to neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) formation. NET in turn release S100A8/A9 and accelerate platelet pyroptosis, forming a positive feedback loop, thereby amplifying the production of proinflammatory cytokines. GSDMD deficiency in platelets or pharmacological inhibition of S100A9 using Paquinimod can break this detrimental feedback loop, thus ameliorating excessive NET-mediated inflammation in mouse models of severe sepsis.

Main

Sepsis, the leading cause of morbidity, mortality and healthcare utilization in children worldwide, is characterized by a dysregulated inflammatory response to infection1. The incidence of sepsis varies substantially by age, peaking in early childhood2. The development of inflammation-related thrombocytopathy during sepsis is recognized as a significant event associated with increased severity of sepsis, leading to higher mortality3. Platelets have emerged as key inflammatory cells implicated in the pathophysiology of sepsis4; however, their role in exacerbating severe sepsis has not been clearly defined.

Pyroptosis, a form of inflammation or infection-induced cell death, is critical for immunity5. Pyroptosis plays a pivotal role in the defense against viral and microbial infections6. Platelets have the necessary components for pyroptosis, including NOD-like receptors containing domain pyrin 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, adaptor-apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), caspase 1 and interleukin-1β (IL-1β)7,8. The NLRP3 inflammasome is implicated in sensing intracellular danger signals in innate immunity and pathogenic inflammation9. During pyroptosis, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome results in GSDMD-pore formation, cell swelling, and a burst of inflammatory cytokine and cytosolic content release. Of note, mitochondria, a source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), have recently been implicated in inflammatory responses10,11. Ox-mtDNA is proinflammatory, participating in the formation of polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) NETs in autoimmune diseases12. NETs are described as a double-edged sword in innate immunity: they serve to defend against bacterial infection, and they produce proinflammatory molecules that amplify the inflammatory response13. However, there is no direct evidence that platelet pyroptosis occurs in sepsis, and if present, whether it is involved in NET formation and the immune host response in severe sepsis.

Previous studies have suggested that an abundance of S100A8/A9 (calprotectin, myeloid-related protein-8/14) protein is released from PMNs14 and NETs15 at the site of inflammation. Heterodimer S100A8/A9 is a molecular pattern associated with alarmin damage that is rapidly released from myeloid lineage cells upon stress or cell/tissue damage, acting as a secondary amplifier of inflammation16. A recent study has demonstrated that a high plasma level of S100A8/A9 at the early stage of sepsis is linked to a higher risk of death in patients with septic shock17. Moreover, S100A8/A9 is an endogenous activator of TLR4, regulating the inflammatory cascade during sepsis16. Platelet TLR4 detects its ligands in blood, inducing platelet binding to adherent PMNs and the formation of NETs18. However, the interaction between S100A8/A9 and platelets in the development of inflammation during sepsis remains unclear.

In the current study, we provide evidence for GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis in severe sepsis using platelet-specific Gsdmd knockout (KO) mice. In severe sepsis, elevated S100A8/A9 induces GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis via a TLR4/NLRP3 axis. Pyroptotic platelet-derived ox-mtDNA potentially promotes NET formation, which in turn contributes to platelet pyroptosis via the release of S100A8/A9, forming a positive feedback loop that exacerbates inflammation in severe sepsis.

Results

Cohort features and proteomic analysis of septic platelets

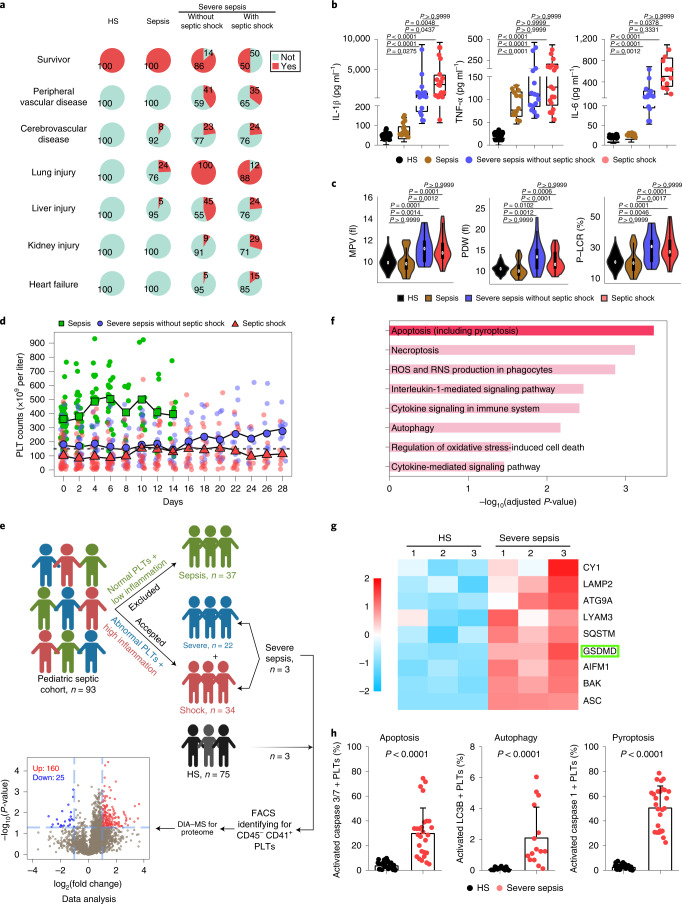

On retrospective examination of the electronic medical records of patients with sepsis (n = 37), severe sepsis (n = 22) and septic shock (n = 34) and healthy subjects (HS; n = 75), we found that children with severe sepsis/septic shock had moderate/severe complications (peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular, lung, liver, kidney and heart) and high mortality rates (14% and 50%) on admission (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). By contrast, patients with sepsis (without severe sepsis/septic shock) had few complications and low death rates after appropriate treatment (Fig. 1a). Plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)), procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in patients with sepsis, especially those in severe sepsis/septic shock, were significantly increased compared with the HS group (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). In addition, patients with severe sepsis/septic shock had evidence of thrombocytopathy (high mean platelet volume, high platelet distribution width and high platelet large cell ratio) and coagulopathy (high activated partial thromboplastin time, prolonged prothrombin time and low fibrinogen) (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Cohort features and proteomic analysis of septic platelets.

a, Pie charts showing mortality and complications in the HS (n = 75) and sepsis groups (sepsis, n = 37; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 22; septic shock, n = 34). b, Boxplots showing the levels of IL-1β (HS, n = 53; sepsis, n = 15; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 17; septic shock, n = 17), TNF-α (HS, n = 53; sepsis, n = 13; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 15; septic shock, n = 18) and IL-6 (HS, n = 53; sepsis, n = 15; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 14; septic shock, n = 11). The boxes indicate the 25% quantile, median and 75% quantile. c, Violin plots showing the platelet parameters: mean platelet volume (HS, n = 75; sepsis, n = 37; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 21; septic shock, n = 31); platelet distribution width (PDW) (HS, n = 73; sepsis, n = 37; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 21; septic shock, n = 30); and high platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR) (HS, n = 75; sepsis, n = 37; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 21; septic shock, n = 31) among sepsis groups. d, Scatterplots showing platelet counts for sepsis, severe sepsis without septic shock and septic shock patients along the time (28 d) axis (sepsis, n = 37; severe sepsis without septic shock, n = 21; septic shock, n = 30). The dotted line indicates the lower limit of platelet counts for HS (150 × 109 to 399 × 109 per liter). e, Schematic diagram of the experimental design for DIA-MS (HS, n = 3; severe sepsis, n = 3). Volcano plot with significantly increased (red) and decreased (blue) expression of proteins from the HS and sepsis groups. Fold change cutoff >2 and P value <0.05. f, Bar plots of the enriched GO biological processes, KEGG or Reactome terms of highly expressed genes from sepsis groups. g, Heatmap of representative proteins related to different cell death signal pathways in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) and HS samples. h, Bar graphs displaying the percentage activation of caspase 3/7 (HS, n = 27; severe sepsis, n = 27), LC3B (HS, n = 15; severe sepsis, n = 15) and caspase 1 (HS, n = 27; severe sepsis, n = 27) in septic and HS platelets using FACS. Data were presented as mean ± s.d. or median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was conducted using Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (b,c), and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (h). PLT, platelet.

Platelet counts in patients with severe sepsis/septic shock were gradually increased after admission, but remained lower compared with the HS or sepsis (without severe sepsis/septic shock) groups (Fig. 1d). Based on the consistent features of severe sepsis/septic shock, and the difference from moderate sepsis, we focused on patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock), who are collectively referred to as ‘severe sepsis’ patients in the following context unless otherwise indicated. Collectively, these results support that the assessment of platelet counts and morphology closely correlate with inflammation and pathology severity in patients with sepsis. Key questions arise as to whether abnormal platelets could potentially offer an additional biomarker to assess sepsis severity in patients, and the role of platelets in exacerbating severe sepsis.

To identify platelet changes associated with severe sepsis, purified platelet (Extended Data Fig. 1a) samples from three patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) and three HS were subjected to high-throughput proteomics analysis using data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) (Fig. 1e). A total of 3,892 proteins were identified and 3,542 proteins were quantified across all the samples (see the source data for Fig. 1e,f). Among all the 185 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), 160 were significantly upregulated and 25 were downregulated in the sepsis group compared with HS (Fig. 1e). Pathway analysis of DEPs in platelets showed apoptosis (including pyroptosis (pyroptosis-related proteins also have been classified into apoptosis)) and necroptosis pathways were significantly upregulated in patients compared with HS (Fig. 1f). Representative proteins related to different cell death signal pathways were displayed as a heatmap. Proteins involved in apoptosis (BAK, P = 0.002, among others) and autophagy (LAMP2, P = 0.034, among others) were increased (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Key pyroptosis-related proteins, including GSDMD (P = 0.007), were also increased in severe sepsis platelets (Fig. 1g). Because of the heterogeneity of platelets in patients with sepsis, fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was performed to delineate the type of cell death pathway that was primarily present in the septic platelets. As shown in Fig. 1h, 30.5% of platelets were apoptotic (caspase 3/7 positive), 2.2% were autophagic (LC3B positive) and 51.2% were pyroptotic (caspase 1 positive). Platelet pyroptosis also ensued in sepsis, although mainly in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Extended Data Fig. 1c). These data demonstrate pyroptosis to be the predominant form of cell death in platelets from severe sepsis.

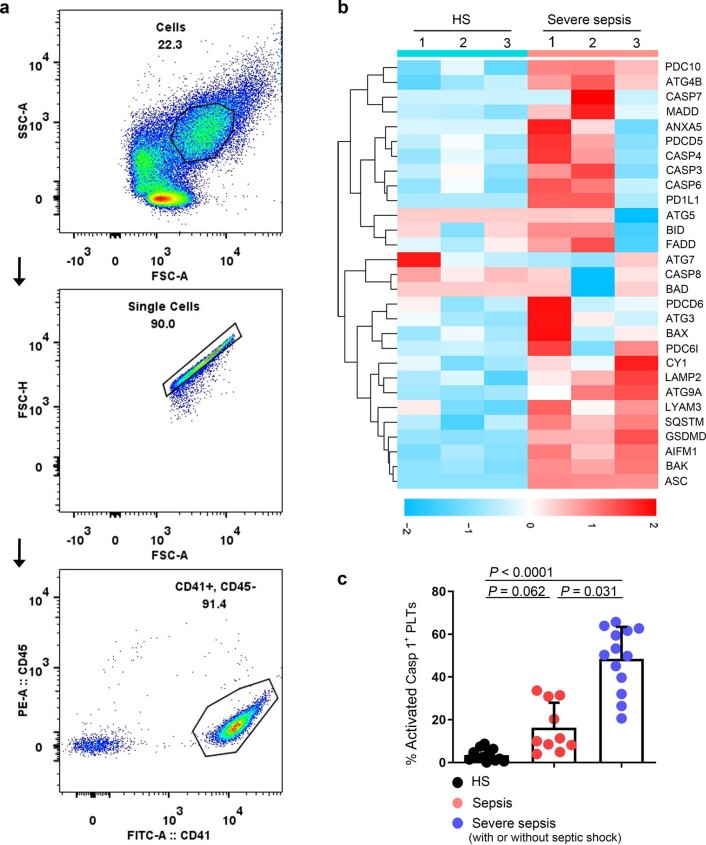

Extended Data Fig. 1. Identified purity of platelet, representative proteins related to different cell death signal pathways and platelet pyroptosis in sepsis.

a, Purified platelets were obtained from human. Purity of platelet preparation was determined by FACS analysis using FITC anti-human CD41a and PE anti-human CD45 (n = 3). b, Heatmap of representative proteins expression related to different cell deaths signal pathways in purified platelet samples from HS (n = 3) and severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (n = 3) using high-throughput proteomics analysis. c, Bar graphs displaying the percentage of activations of caspase 1 in platelets from sepsis and severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) and HS using FACS (HS: n = 13, Sepsis: n = 10, Severe sepsis with or without septic shock: n = 13). Data was presented as mean ± s.d. Kruskall-Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for c. HS, healthy subjects; Severe sepsis, severe sepsis/septic shock; PLTs, platelets.

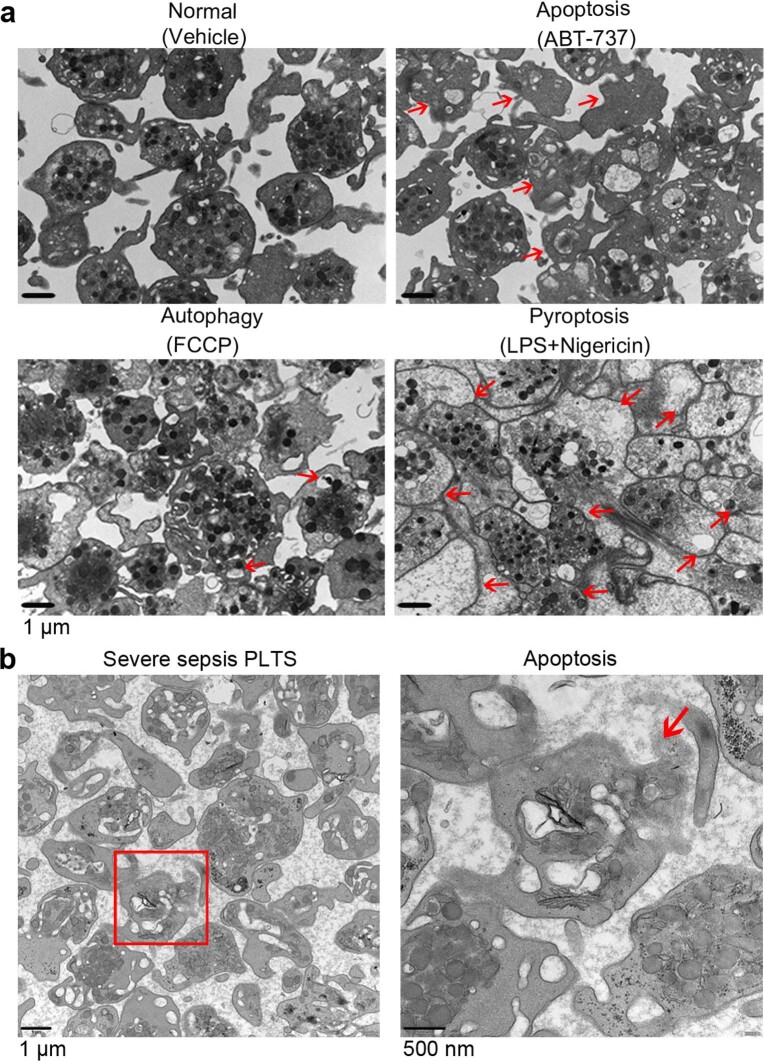

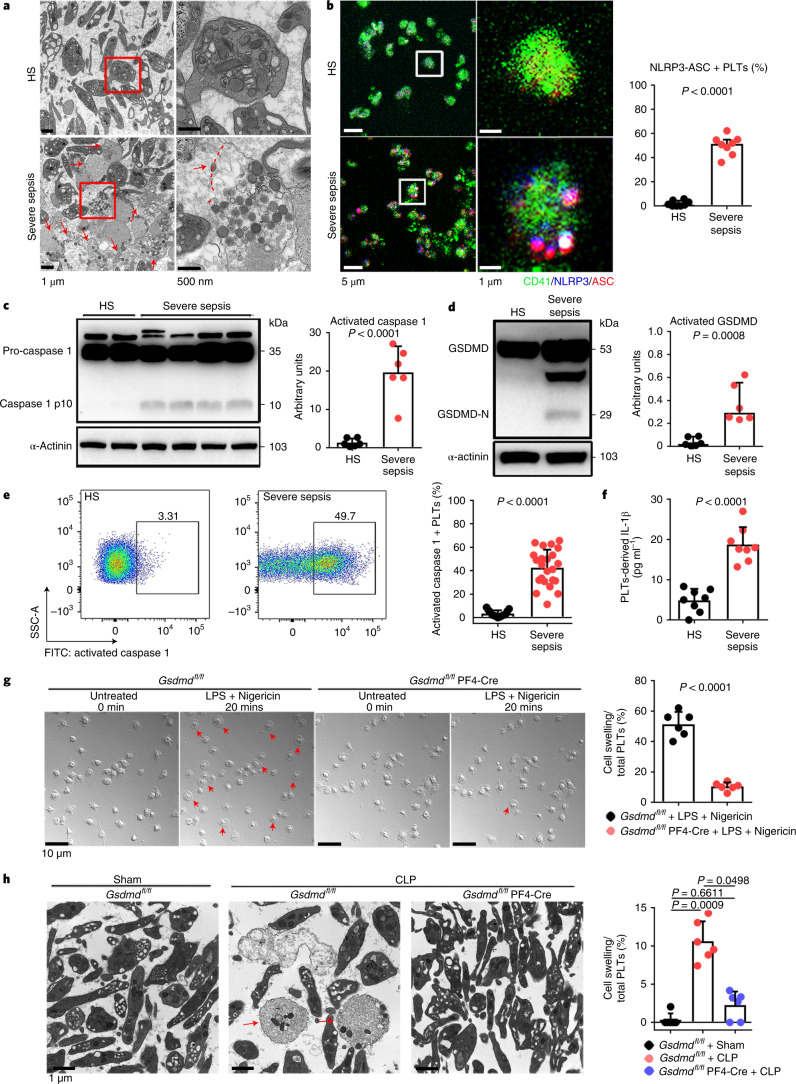

GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis ensues in severe sepsis platelets

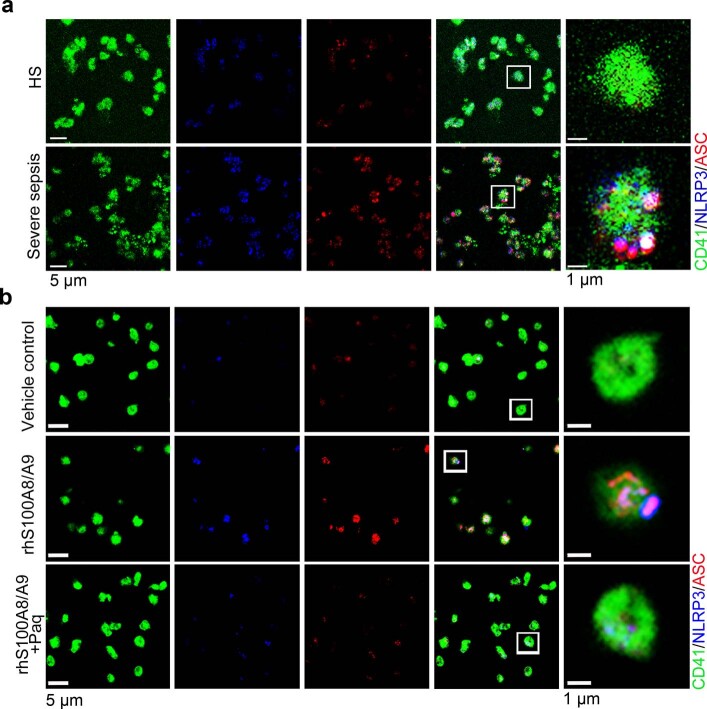

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to determine the ultrastructure of platelets from patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) and HS. First, platelets were treated with different cell death agonists in vitro to identify the features of different cell deaths by TEM (Extended Data Fig. 2a). In severe sepsis platelets (with or without septic shock), in addition to some features of apoptosis (Extended Data Fig. 2b), cell swelling, loss of cellular architecture, plasma membrane rupture and release of cytosolic contents, all characteristics of end-stage pyroptosis6 were found (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescence showed that NLRP3 inflammasomes assembled with ASC in platelets from patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3a). In addition, caspase 1 activation was significantly increased in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) compared with HS platelets (Fig. 2c,e). Consistent with the results of DIA-MS, activated GSDMD (cleaved GSDMD-N) was significantly increased in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) compared with HS platelets (Fig. 2d). Compared with HS, the level of platelet-derived IL-1β was significantly increased in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 2f). These results suggest that platelet pyroptosis is activated in severe sepsis.

Extended Data Fig. 2. TEM images of platelets induced by apoptosis, autophagy or pyroptosis agonists and apoptosis in severe sepsis patients.

a, Platelets were induced to apoptosis (10 μM ABT-737 induces apoptosis), autophagy (10 μM FCCP induces autophagy) and pyroptosis (10 μg/ml LPS and 5 μM Nigericin induces pyroptosis). TEM imaging of different states in platelets. b, Representative lower and higher power TEM field demonstrating loss of platelet ultrastructure in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients (n = 5), with reduced granules/organelles and increased vacuolation. Apoptosis, red arrowheads indicate shrinkage of cell membrane and apoptotic bodies in apoptosis of platelet. Scale bars: 1 μm and 500 nm. Severe sepsis, severe sepsis/septic shock; PLTs, platelets.

Fig. 2. GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis ensues in septic platelets.

a, Representative low- and high-power TEM fields showing platelet ultrastructures from patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (n = 5) and HS (n = 5). Red arrowheads indicate swelling and rupture of the platelet plasma membrane during severe sepsis. The magnified TEM showed a swollen platelet that had ruptured (region around red arrow) and released its cellular contents. Scale bars, 1 μm and 500 nm. b, Colocalization of CD41 (green), ASC (red) and NLRP3 (blue) in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (HS, n = 8; severe sepsis, n = 8). Purple indicates overlap. Scale bars, 5 μm and 1 μm. c, Expression and quantification of pro-caspase 1 and activated caspase 1 in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (HS, n = 6; severe sepsis, n = 6). d, Expression and quantification of GSDMD and GSDMD N terminus proteins in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (HS, n = 6; severe sepsis, n = 6). e, FACS analysis of the activated caspase 1 in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (HS, n = 13; severe sepsis, n = 23). f, Expression of IL-1β in platelets from HS and sepsis groups (HS, n = 8; severe sepsis, n = 8). g, Live-imaging of platelets from Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice induced by LPS (10 μg ml−1) and NIG (5 μM) for 20 min (n = 6). Scale bars, 10 μm. h, Representative TEM field of platelets from Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice with or without CLP operation (n = 6). Scale bar, 1 μm. Data were presented as mean ± s.d. or median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired two-tailed t-test (b–g), and Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (h). Sham, sham-operated mice.

Extended Data Fig. 3. The expression and localization of NLRP3 and ASC in severe sepsis platelets or rhS100A8/A9-induced platelets.

a, b, Immunofluorescence analysis showing the co-localization of CD41 (green), ASC (red) and NLRP3 (blue) in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients (a) (n = 8); and platelets treated with 1 μg/ml rhS100A8/A9 or 10 μM Paquinimod (b) (n = 6); purple indicates overlap. Scale bars: 5 μm and 1 μm. HS, healthy subjects; Severe sepsis, severe sepsis/septic shock; NLRP3, NOD-like receptors containing domain pyrin 3 inflammasome; ASC, adaptor-apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; Paq, Paquinimod.

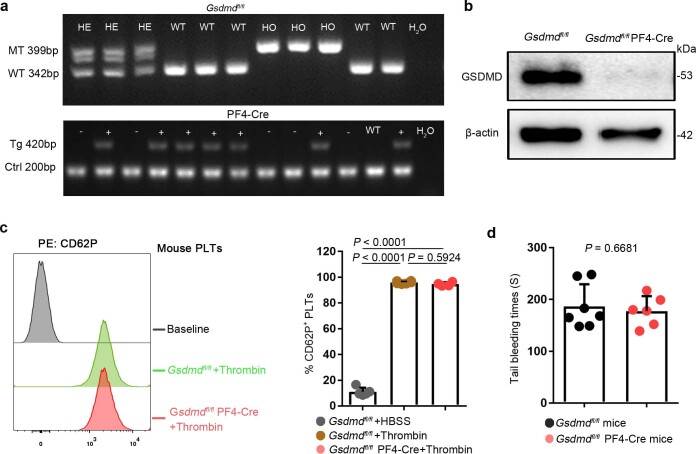

To further investigate the requirement of GSDMD for platelet pyroptosis, platelet-specific Gsdmd KO (Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre) mice were produced by crossing Gsdmdfl/fl mice with PF4-Cre mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). The parameters and classic functions (platelet activation and thrombosis/hemostasis) of platelets were not significantly different between platelet-specific Gsdmd KO mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice (Supplementary Table 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). After lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Nigericin (NIG) treatment19 (used as classical pyroptosis stimuli), the morphologic features of rapid swelling and membrane rupture were observed in platelets from the littermate controls, but were absent in the Gsdmd KO platelets (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Moreover, to assess the role of GSDMD in platelets pyroptosis in vivo, Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice were subjected to the CLP-induced sepsis murine model. Swollen ruptured platelets with release of contents were observed via TEM in Gsdmdfl/fl mice, but these changes were not seen in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice (Fig. 2h). These data suggest that GSDMD is required to trigger pyroptosis in septic platelets.

Extended Data Fig. 4. The identification and classic functions of platelets from platelet-specific Gsdmd KO mice.

a, b, The Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice were identified by PCR (a) and confirmed by western blot (b), respectively (n = 6). c, The platelet (isolated from mice) suspensions were incubated with 0.1 U/ml thrombin for 30 minutes. P selectin translocation to membrane was assessed by FACS after stimulation with thrombin. The representative plots were presented as the number of counts over the log of associated fluorescence (baseline refers to the group without thrombin). Quantification of data presented as percentage of platelet activation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (Gsdmdfl/fl + HBSS, n = 5; Gsdmdfl/fl + Thrombin, n = 6; Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre+Thrombin, n = 4). d, Tail bleeding times of mouse was measured with the tail dipped into warmed saline to assess haemostasis using a tail-guillotine. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (Gsdmdfl/fl mice, n = 7; Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice, n = 6). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for c. Unpaired t test with two-tailed for d. MT, mutation; WT, wild type; Tg, transgene; Ctrl, control; GSDMD, Gasdermin D; PLTs, platelets; HBSS, hank’s balanced salt solution.

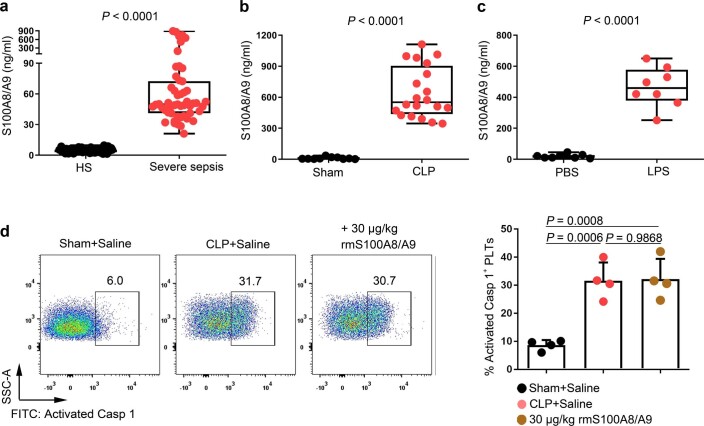

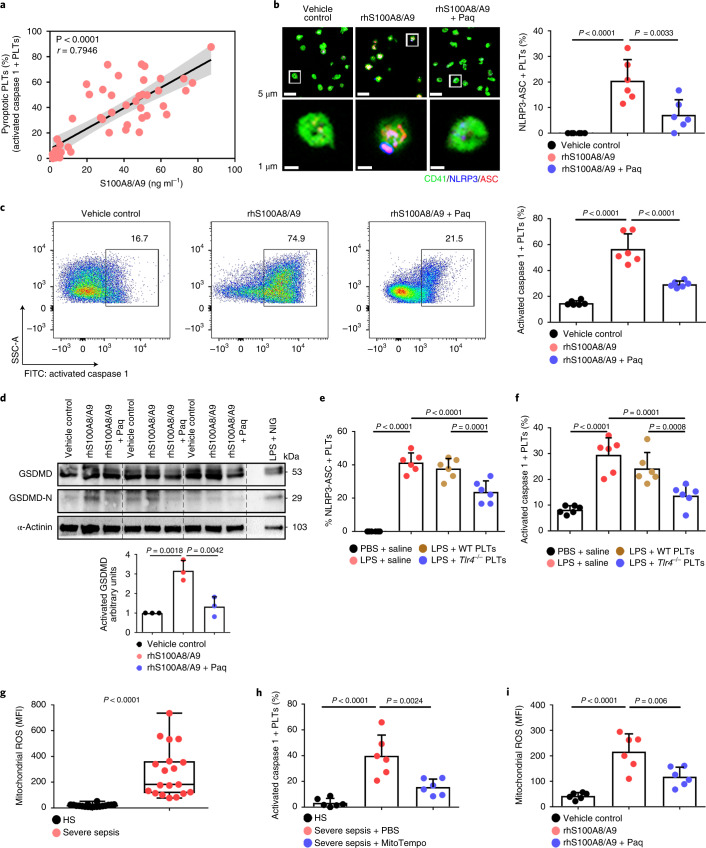

S100A8/A9 induces platelet pyroptosis via the TLR4 pathway

Consistent with previous studies20, S100A8/A9 was significantly increased in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Similarly, S100A8/A9 was also significantly elevated in CLP- or LPS-induced sepsis mice (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). The percentage of pyroptotic platelets (activated caspase 1 positive) was positively correlated with the plasma levels of S100A8/A9 in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 3a). Our in vitro result showed that NLRP3 inflammasomes were assembled with ASC in platelets treated with recombinant human S100A8/A9 (rhS100A8/A9) compared with vehicle control (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3b). Furthermore, activated caspase 1 (Fig. 3c) and GSDMD (Fig. 3d) were significantly increased in platelets treated with rhS100A8/A9 compared with vehicle control. In vivo, recombinant mouse S100A8/A9 (rmS100A8/A9) could induce platelet pyroptosis (activated caspase 1 positive platelets) like CLP (Extended Data Fig. 5d).

Extended Data Fig. 5. The levels of S100A8/A9 in sepsis patients/mice and the caspase 1 activity in platelets from the CLP or rmS100A8/A9-injected mice.

a-c, Boxplots displaying the level of heterodimer S100A8/A9 in plasma from (a) severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients (HS: n = 53, Severe sepsis: n = 51), (b) CLP-induced sepsis mice (Sham, n = 10, CLP: n = 20) and (c) LPS-induced sepsis mice (PBS, n = 8, LPS: n = 8) by ELISA. The boxes indicate the 25% quantile, median, and 75% quantile. d, In a mouse model, mice that were injected intravenously with rmS100A8/A9 (30 μg/kg) or normal saline (n = 4 mouse/group) for 6 hours. Another mouse model, mice were induced CLP for 6 hours. FACS analysis displaying the caspase 1 activity in platelets. Mann Whitney test with two-tailed for a-b. Unpaired t test with two-tailed for c. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for d. Data was presented as mean ± SD. HS, healthy subjects; Severe sepsis, severe sepsis/septic shock; Sham, sham-operated mice; CLP, CLP-induced sepsis mice; PBS, PBS-injected mice; LPS, LPS-injected mice.

Fig. 3. S100A8/A9 induces platelet pyroptosis via the TLR4 pathway.

a, Scatterplot displaying correlation of platelet pyroptosis (activated caspase 1 positive platelets) with plasma levels of S100A8/A9 in severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients and HS (n = 49). r, correlation coefficient. b, Coexpression of CD41 (green), ASC (red) and NLRP3 (blue) in platelets (n = 6). Purple indicates overlap. Scale bars, 5 μm and 1 μm. c, FACS analysis and bar graphs displaying the caspase 1 activity of platelets (n = 6). d, Human platelets were treated with 1 μg ml−1 rhS100A8/A9 or 10 μM Paquinimod for 4 h, or LPS (10 μg ml−1) priming for 3.5 h and then NIG (5 μM) for 30 min. Expression and quantification of GSDMD and GSDMD N terminus in human platelets (n = 3). e,f, In the LPS-induced murine model, mice depleted of platelets were transfused with 1.2 × 107 purified platelets (200 μl, 6 × 1010 platelets per liter) from Tlr4−/− or WT mice (n = 6). Bar graphs show the percentage of NLRP3-ASC inflammasome (e) and caspase 1 activity (f). g, Boxplots displaying abundant mitochondrial ROS production in platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (HS, n = 18; severe sepsis, n = 19). The boxes indicate the 25% quantile, median and 75% quantile. h, Bar graphs displaying caspase 1 activity in septic platelets by FACS analysis (n = 6). i, Bar graphs displaying mitochondrial ROS production in platelets (n = 6). Data were presented as mean (or fluorescence) ± s.d. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-tailed Pearson’s correlation test (a), two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (g), and one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b–f,h,i). LPS + saline, LPS-injected mice transfused with normal saline; LPS + Tlr4−/− PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with Tlr4−/− platelets; LPS + WT PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with WT platelets; Paq, Paquinimod; PBS, PBS-injected mice; rhS100A8/A9 + Paq, platelets from HS treated with rhS100A8/A9 and Paquinimod; rhS100A8/A9, platelets from HS treated with rhS100A8/A9; vehicle control, platelets from HS treated with HBSS.

Having observed that S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis, we sought to identify candidate platelet receptors of S100A8/A9. S100A8/A9 can regulate cell function by binding to cell-surface receptors such as TLR4 (ref. 16), advanced glycation end products21 and CD36 (ref. 22). To determine which receptor participates in S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis, we evaluated platelet pyroptosis in the presence of neutralizing antibodies for CD36, advanced glycation end products or TLR4. Platelet pyroptosis was significantly suppressed by anti-TLR4 antibody compared with with the other neutralizing antibodies and isotype control (percentage inhibition = 36.79, P = 0.0025) (Extended Data Fig. 6a). In addition, platelet activation was significantly inhibited by anti-CD36 antibody compared with that observed with other neutralizing antibodies and isotype control (Extended Data Fig. 6b), which is consistent with a previous report22. Paquinimod (also known as ABR-215757) can prevent the binding of S100A9 to TLR4 (ref. 23). Blockade of S100A9 by Paquinimod significantly attenuated NLRP3 inflammasome formation (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3b), the activation of caspase 1 (Fig. 3c) and GSDMD (Fig. 3d) in platelets.

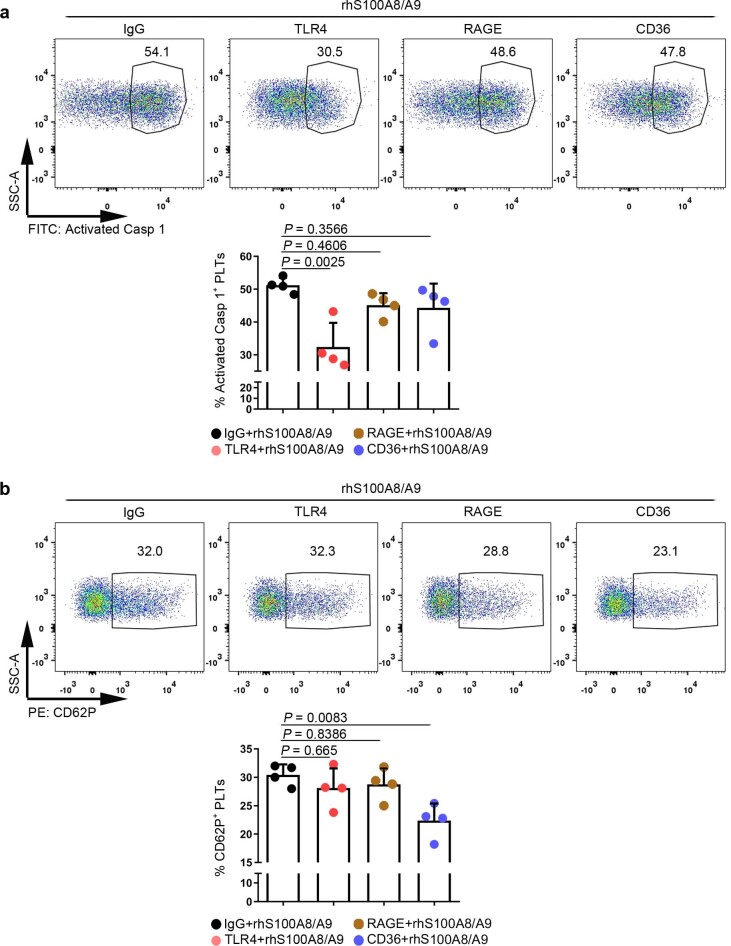

Extended Data Fig. 6. Putative receptors for S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis.

The platelet (isolated from HS) suspensions were incubated in the presence of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (20 μg/ml) against control IgG, CD36, RAGE, or TLR4, and then treated with 1 μg/ml rmS100A8/A9 for 4 hours. a, FACS analysis displaying the caspase 1 activity in human platelets after stimulation. The quantified results are shown on the below. b, P selectin translocation to membrane (CD62P) was assessed by flow cytometry after stimulation. The quantified results are shown on the below. Data was presented as mean ± SD, n = 4. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for a, b. HS, healthy subjects; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; RAGE, advanced glycation end products.

To further determine whether TLR4 is involved in S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis, platelets (wild type (WT) or global Tlr4 deficient (Tlr4−/−), no significant differences in the parameters of platelets) (Supplementary Table 4) were treated with rmS100A8/A9. Compared with the vehicle group, activation of caspase 1 was significantly attenuated in Tlr4−/− platelets treated with rmS100A8/A9 in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Furthermore, Tlr4−/− platelets were transfused into mice to determine TLR4 function in vivo. To monitor transfused platelet dynamics, purified platelets from Tlr4−/− or WT mice were transfused intravenously into a mT/mG:PF4-Cre mouse24, where PF4-Cre drives membrane green fluorescent proteins (GFP) expression. After LPS treatment, a greater percentage of transfused Tlr4−/− platelets (GFP negative and CD41 positive cells) over total platelet counts (CD41 positive cells) were retained and detected compared with mice transfused with WT platelets (Extended Data Fig. 7b–d). NLRP3 inflammasome formation and activation of caspase 1 were significantly attenuated following Tlr4−/− platelet transfusion compared with transfusion with WT platelets (Fig. 3e,f and Extended Data Fig. 7e,f). Taken together, our results suggest that TLR4 is required for S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis.

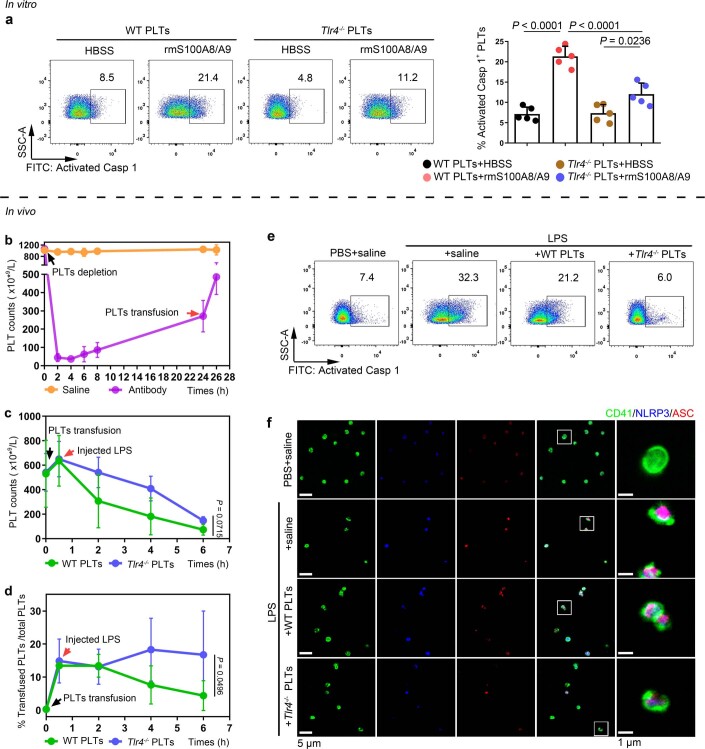

Extended Data Fig. 7. NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase 1 activity of platelets in mice transfused with Tlr4-/- or WT platelets.

a, In vitro, FACS analysis displaying the caspase 1 activity in platelets (Tlr4-/- or WT) treated with 1 μg/ml rmS100A8/A9 for 4 hours (n = 5). The quantified results are shown on the right. b-f, In vivo, a total of 1.2 ×107 purified platelets (volume: 200 μl, concentration: 6 ×1010 platelets/L) from Tlr4-/- or WT mice were intravenously transfused to mT/mG: PF4-Cre mouse. (b) After platelet depletion, platelet counts in mice were assessed at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 26 hours using a hematology analyzer (n = 3). (c) Platelet counts in mice before and after transfused with WT or Tlr4-/- platelets were detected at 0, 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 hours using a hematology analyzer (n = 3). (d) The percentages of transfused Tlr4-/- platelets in total platelets of mice were detected at 0, 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 hours using FACS analysis (n = 3). (e) Caspase 1 activity was measured using FACS analysis (n = 6). (f) The association of ASC and NLRP3 inflammasome in murine platelets was measured by immunofluorescence analysis. Platelets were stained for CD41 (green), ASC (red) and NLRP3 (blue); scale bars: 5 μm and 1 μm; n = 6. Data was presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for a. Two-way ANOVA test for c, d. Abbreviation is as follow: HBSS, hank’s balanced salt solution; Saline, mice transfused with normal saline; WT PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with WT platelets; Tlr4-/- PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with Tlr4-/- platelets. PBS, PBS-injected mice; LPS + saline, LPS-injected mice transfused with normal saline; LPS + WT PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with WT platelets; LPS + Tlr4-/- PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with Tlr4-/- platelets; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NLRP3, NOD-like receptors containing domain pyrin 3 inflammasome; ASC, adaptor-apoptosis-associated speck-like protein.

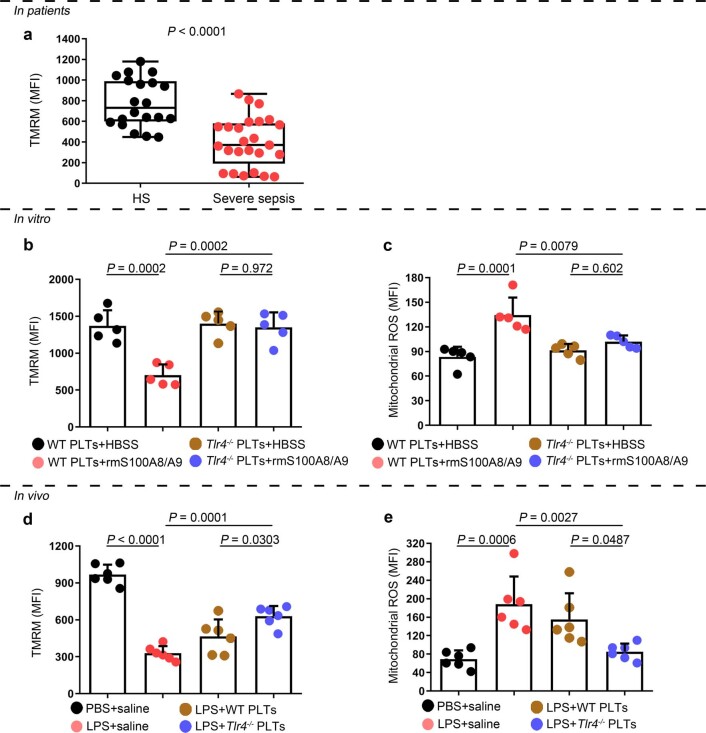

Because mitochondrial ROS are activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome25, we then assessed the mitochondrial function of septic platelets. Platelets isolated from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients exhibited mitochondrial dysfunction, as indicated by dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) (Extended Data Fig. 8a) and increased mitochondrial ROS production (Fig. 3g). Blockade of mitochondrial ROS production with the mitochondrial-specific antioxidant MitoTempo significantly attenuated induction of caspase 1 activity in septic platelets (Fig. 3h). Dissipation of Δψm and increased mitochondrial ROS production were observed in platelets treated with rmS100A8/A9 in vitro (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 8b,c) and in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e); however, these changes were not found in Tlr4−/− platelets (Extended Data Fig. 8). Our results suggest that mitochondrial ROS are required for the activation of caspase 1 and the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Extended Data Fig. 8. The function of mitochondria in septic platelets and S100A8/A9-induced platelets.

a, In platelets from severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) patients, bar graphs displaying change of mitochondrial membrane potential (∆Ψm) by staining with 40 nM TMRM using FACS analysis (HS: n = 20, Severe sepsis: n = 25). b, c, In vitro, bar graphs displaying change of mitochondrial ∆Ψm (b) and ROS production (c) in platelets (Tlr4-/- or WT) treated with 1 μg/ml rmS100A8/A9 for 4 hours using FACS analysis (n = 5). d, e, In the LPS induced murine model, mice with platelets depletion were transfused with a total of 1.2 ×107 purified platelets (volume: 200 μl, concentration: 6 ×1010 platelets/L) from Tlr4-/- or WT mice (n = 6/group). After 6 hours, bar graphs displaying change of mitochondrial ∆Ψm (d) and ROS production (e) in platelets (Tlr4-/–or WT) using FACS analysis (n = 6). Data was presented as mean fluorescence ± SD. Unpaired t test with two-tailed for a. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for b-e. Abbreviation is as follow: HS, healthy subjects; Severe sepsis, severe sepsis/septic shock; HBSS, hank’s balanced salt Solution. PBS, PBS-injected mice; LPS + saline, LPS-injected mice transfused with normal saline; LPS + WT PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with WT platelets; LPS + Tlr4-/- PLTs, LPS-injected mice transfused with Tlr4-/- platelets; TMRM, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

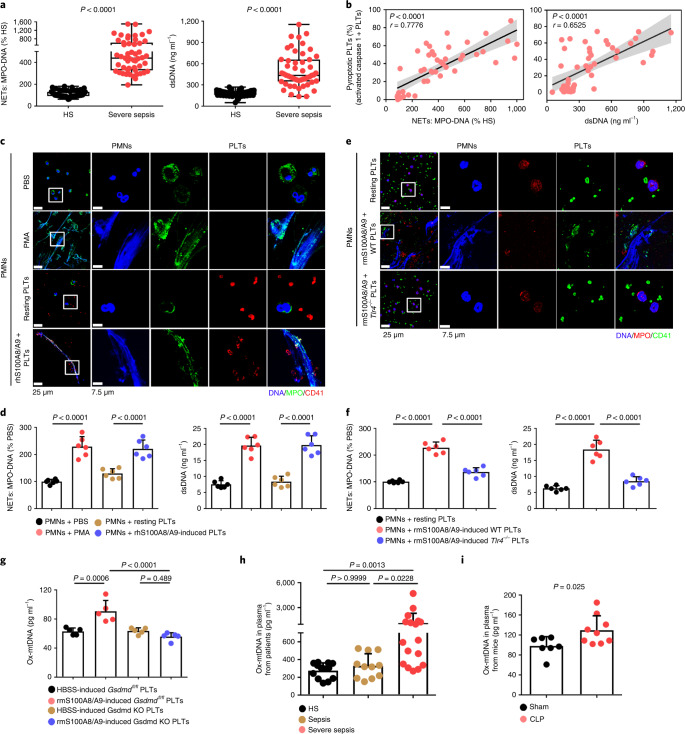

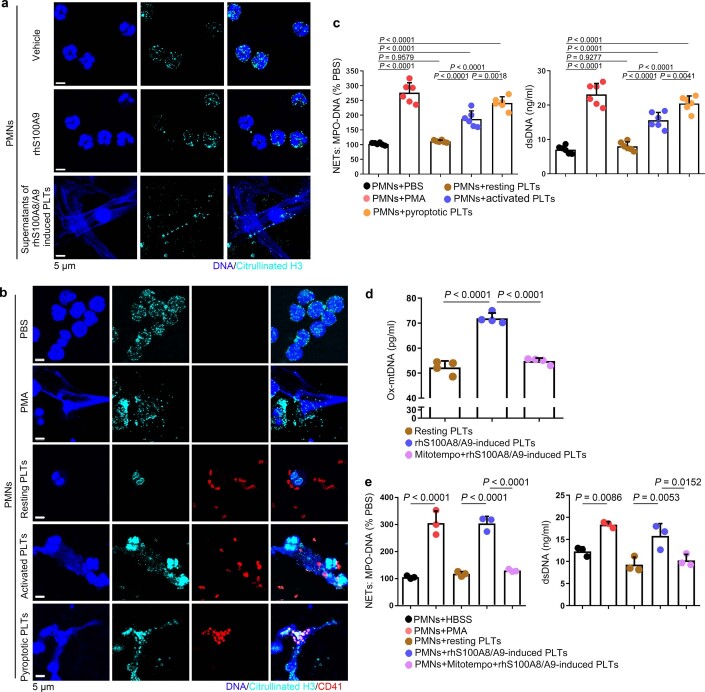

Pyroptotic platelets promote NET formation through ox-mtDNA

NET formation (as assessed by myeloperoxidase (MPO)–DNA complexes and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)) was significantly increased in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 4a). NET formation was positively correlated with the percentage of pyroptotic platelets (activated caspase 1 positive platelets) in patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 4b). When incubated with purified PMNs, pyroptotic platelets induced by either phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, used as a classical NET stimuli) or rhS100A8/A9, induced NET formation (DNA and MPO double-positive cells) with a concomitant increase in MPO–DNA complexes and dsDNA, compared with PBS-treated and resting platelet-treated groups (Fig. 4c,d), but not rhS100A8/A9 alone (Extended Data Fig. 9a). In the case of equivalent cells, pyroptotic platelets could induce more NET formation than activated platelets (Extended Data Fig. 9b,c). Because S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis via TLR4 (Fig. 3), murine PMNs were incubated with rmS100A8/A9-treated murine platelets (WT or Tlr4−/−) to assess NET formation. rmS100A8/A9-induced Tlr4−/− platelets had significantly reduced NET formation compared with WT platelets (Fig. 4e,f). These results suggest that S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis contributes to NET formation.

Fig. 4. Pyroptotic platelets promote NET formation via ox-mtDNA.

a, Boxplots showing quantification of MPO–DNA and dsDNA (NET structures) in the plasma of HS (n = 53) and patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (n = 51). The boxes indicate the 25% quantile, median and 75% quantile. b, Scatterplots displaying correlations of platelet pyroptosis (activated caspase 1 positive platelets) with the levels of MPO–DNA (HS, n = 15; severe sepsis, n = 34) complexes and dsDNA (HS, n = 20; severe sepsis, n = 29) in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) and HS (r, correlation coefficient; n = 49). c, Immunofluorescence analysis showing S100A8/A9-induced pyroptotic platelets induced NET formation. Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-MPO for PMNs or NETs (green) and CD41 for platelets (red). Scale bars, 25 μm and 7.5 μm. d, Quantification of MPO–DNA and dsDNA in the supernatant of cells (n = 6). e, Immunofluorescence analysis showing NET formation in PMNs treated with rmS100A8/A9-induced platelets (WT or Tlr4−/−) (n = 6). Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-MPO for PMNs or NETs (red) and CD41 for platelets (green). Scale bars, 25 μm and 7.5 μm. f, Bar graphs displaying the levels of MPO–DNA and dsDNA in the supernatant of cells treated with rmS100A8/A9-induced platelets (Tlr4−/− or WT) (n = 6). g, Levels of ox-mtDNA in supernatant of S100A8/A9-induced pyroptotic platelets (for 4 h) determined using a General 8-OHdG ELISA Kit (n = 5). h, Levels of ox-mtDNA in plasma from sepsis patients (sepsis, n = 11; severe sepsis, n = 17) and HS (n = 13). i, Levels of ox-mtDNA in plasma of sham (n = 7) or CLP mice (n = 9). Data were presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (a), two-tailed Pearson’s correlation test (b), one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (d,f,g), Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (h) and two-tailed unpaired t-test (i).

Extended Data Fig. 9. The formation of NET with different treatments and the release of ox-mtDNA from S100A8/A9-induced platelets after MitoTempo treatment.

a, Representative immunofluorescence of platelets treated with rhS100A8/A9 alone or supernatants of rhS100A8/A9-induced platelets for 4 hours. Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-citrullinated H3 for PMNs or NETs (cyan); scale bars: 5 μm; n = 4. b-c, PMNs isolated from HS were incubated with PBS, 50 nM PMA, and resting platelets, 0.1 U/ml thrombin activated platelets or 1 μg/ml S100A8/A9-induced platelets for 4 hours. Representative immunofluorescence of NET formation treated with PMA, resting platelets, thrombin or S100A8/A9-induced platelets (b). Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-citrullinated H3 for PMNs or NETs (green), CD41 for platelet (red). (c) Quantification of MPO-DNA and dsDNA in the supernatant of NET formation using PicoGreen fluorescent dye and MPO-DNA-ELISA, respectively (n = 6). d-e, Purified platelets suspensions were treated with rhS100A8/A9 (1 μg/ml) and MitoTempo (5 mM) for 4 hours, and then 50 nM PMA, S100A8/A9-induced platelets or MitoTempo-S100A8/A9-induced platelets induced NET formation. (d) The levels of ox-mtDNA in supernatant of S100A8/A9-induced platelets were determined by General 8-OHdG ELISA Kit (n = 4). (e) Quantification of MPO-DNA and dsDNA (NETosis) in the supernatant of cells using PicoGreen fluorescent dye and MPO-DNA-ELISA, respectively (n = 3). Data was presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for c-e. Abbreviation is as follow: HS, healthy subjects; PLTs, platelets; PMNs, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; MPO, myeloperoxidase; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; NET, neutrophil extracellular trap; ox-mtDNA, oxidized mitochondrial DNA.

Because ox-mtDNA participates in NET formation12, we wondered whether platelet-derived ox-mtDNA could induce NET formation. First, we found that supernatants of rhS100A8/A9-induced platelets could induce NET formation (Extended Data Fig. 9a), indicating pyroptotic platelets may induce NET formation without direct interaction with PMNs. Moreover, we found that levels of DNA 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) were significantly increased in the supernatant of rmS100A8/A9-treated platelets (Fig. 4g), indicative of platelet-derived ox-mtDNA release. The increased DNA 8-OHdG was significantly attenuated in rmS100A8/A9-induced Gsdmd KO platelets compared with controls (Fig. 4g). Furthermore, the ox-mtDNA level was significantly increased in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 4h) and CLP-induced mice (Fig. 4i). Blockade of mitochondrial ROS with the mitochondrial-specific antioxidant MitoTempo significantly attenuated the increase in ox-mtDNA (DNA 8-OHdG) in S100A8/A9-induced platelets (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Moreover, NET formation (MPO–DNA and dsDNA) was also significantly decreased in S100A8/A9-induced platelets with MitoTempo (Extended Data Fig. 9e). These results suggest that S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis releases ox-mtDNA, which may induce NET formation in severe sepsis.

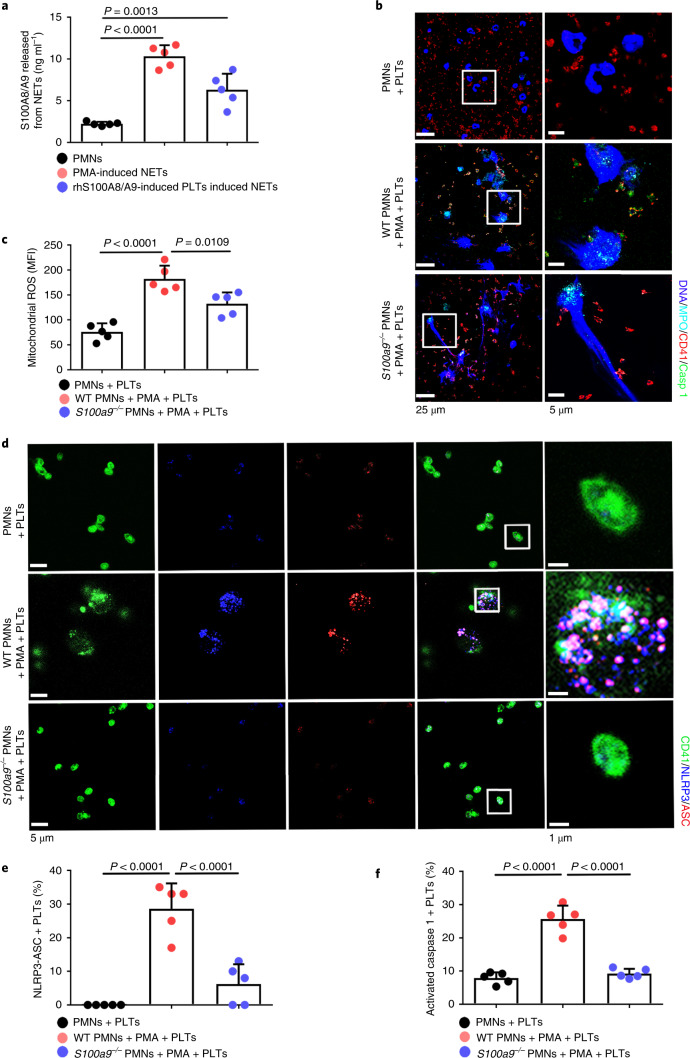

NETs induce platelet pyroptosis via releasing S100A8/A9

Consistent with previous studies14, S100A8/A9 was significantly increased in PMA- or rhS100A8/A9-induced pyroptotic platelet-induced NETs (Fig. 5a). To determine whether NET-derived S100A8/A9 induce platelet pyroptosis, murine platelets were incubated with PMA-treated murine PMNs (WT or global S100a9 deficient (S100a9−/−)). Immunofluorescence demonstrated pyroptotic platelets (caspase 1 positive cells) in the net structure of NETs (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 10a). Platelet pyroptosis, as indicated by mitochondrial ROS, NLRP3 inflammasome and activated caspase 1, was significantly reduced when incubated with S100a9−/− PMNs compared with WT PMNs (Fig. 5c–f). These results suggest that NET-derived S100A8/A9 contributes to platelet pyroptosis.

Fig. 5. NETs induce platelet pyroptosis via releasing S100A8/A9.

a, S100A8/A9 released from NETs determined by ELISA (n = 5). b, Representative immunofluorescence images of pyroptotic platelets incubated with PMA-treated murine PMNs (WT or S100a9−/−). Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-MPO for PMNs or NETs (cyan), CD41 for platelets (red) and caspase 1 for pyroptosis (green). Scale bars, 25 μm and 5 μm. c, Bar graphs displaying mitochondrial ROS production in platelets cocultured with PMA-treated murine PMNs (WT or S100a9−/−) using FACS analysis (n = 5). d, Immunofluorescence analysis showing coexpression of CD41 (green), ASC (red) and NLRP3 (blue) in platelets cocultured with PMA-treated murine PMNs (WT or S100a9−/−) (n = 5). Purple indicates overlap. Scale bars, 5 μm and 1 μm. e, Quantified results for the NLRP3 inflammasome are shown. f, Bar graphs displaying the caspase 1 activity of platelets cocultured with PMA-treated murine PMNs (WT or S100a9−/−) by FACS analysis (n = 5). Data were presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (a,c,e,f).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Immunofluorescence of pyroptotic platelets in NETs and the change of platelet counts in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice by CLP.

a, PMNs (S100a9-/- or WT) were incubated with 50 nM PMA to induced NET formation for 4 hours, and then incubated with platelets for another 4 hours. Representative immunofluorescence of PMNs incubated with platelets. Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-MPO for PMNs or NETs (cyan), CD41 for platelet (red) and activated caspase 1 for pyroptosis (green); scale bars: 25 μm and 5 μm. b, In the CLP-induced sepsis model, platelet counts in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and littermate control Gsdmdfl/fl mice were assessed at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours using a hematology analyzer (n = 5). Data was presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for b. Abbreviation is as follow: PLT, platelet; NS, not statistically significant; PMNs, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; MPO, myeloperoxidase; Sham, sham-operated mice; CLP, CLP-induced sepsis mice; GSDMD, Gasdermin D.

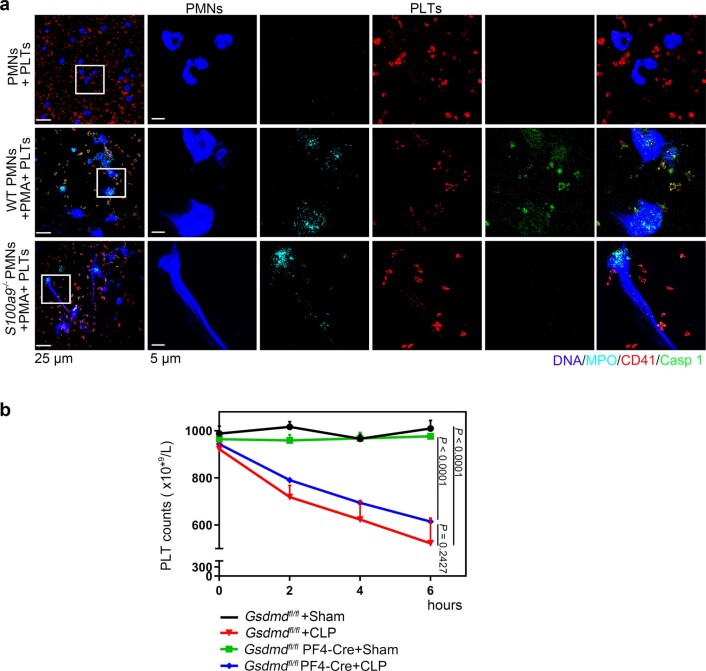

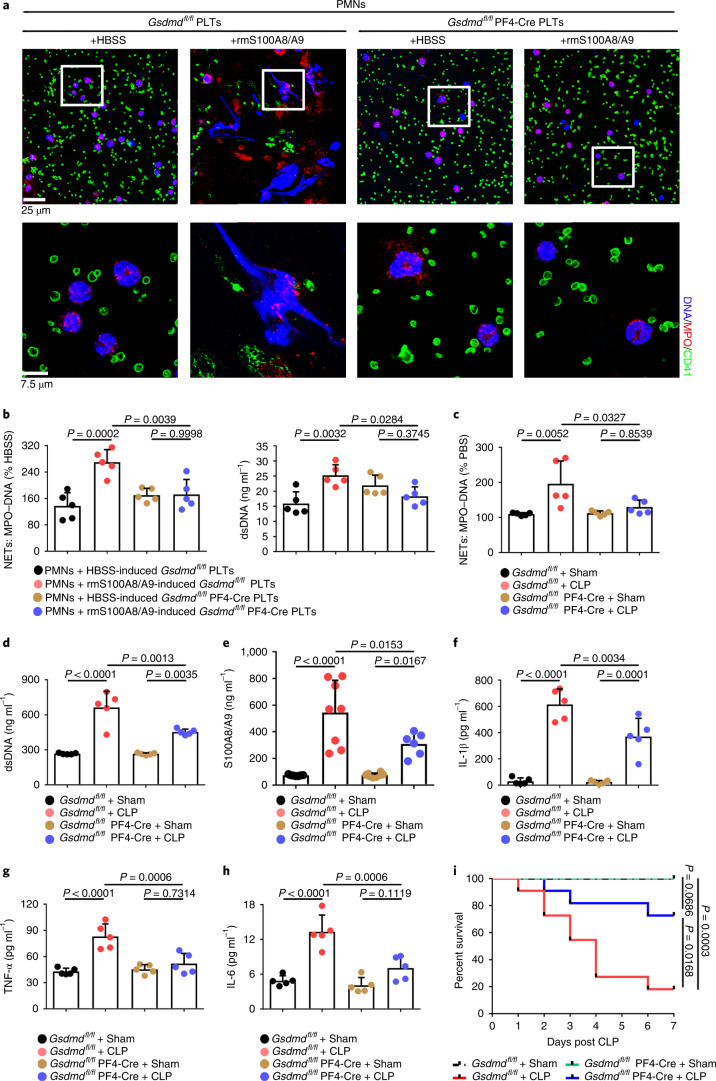

GSDMD-deficient platelets ameliorate excessive inflammation

To address the role of GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis in NET formation in severe sepsis, platelets isolated from Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice were treated with rmS100A8/A9 to induce pyroptosis, followed by incubation with murine PMNs. Incubation with rmS100A8/A9-treated Gsdmdfl/fl platelets induced NET formation, as indicated by DNA and MPO double-positive cells, but this was not observed in the Gsdmdfl/fl KO platelets (Fig. 6a). Moreover, NET formation was also significantly decreased in rmS100A8/A9-induced Gsdmd KO platelets (Fig. 6b). In vivo, NET formation in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice was significantly attenuated by CLP compared with Gsdmdfl/fl mice (Fig. 6c,d). After 6 h of CLP, plasma levels of heterodimer S100A8/A9 were significantly increased in Gsdmdfl/fl mice, and significantly reduced in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice (Fig. 6e). Consistent with the patient results (Fig. 1b), the proinflammatory cytokines in Gsdmdfl/fl mice were significantly increased by CLP, whereas they were significantly reduced in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice (Fig. 6f–h). Moreover, mortality in Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice was significantly reduced by CLP compared with in Gsdmdfl/fl mice (Fig. 6i). Our results suggest that GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis contributes to NET formation, enhanced inflammation and mortality associated with severe sepsis.

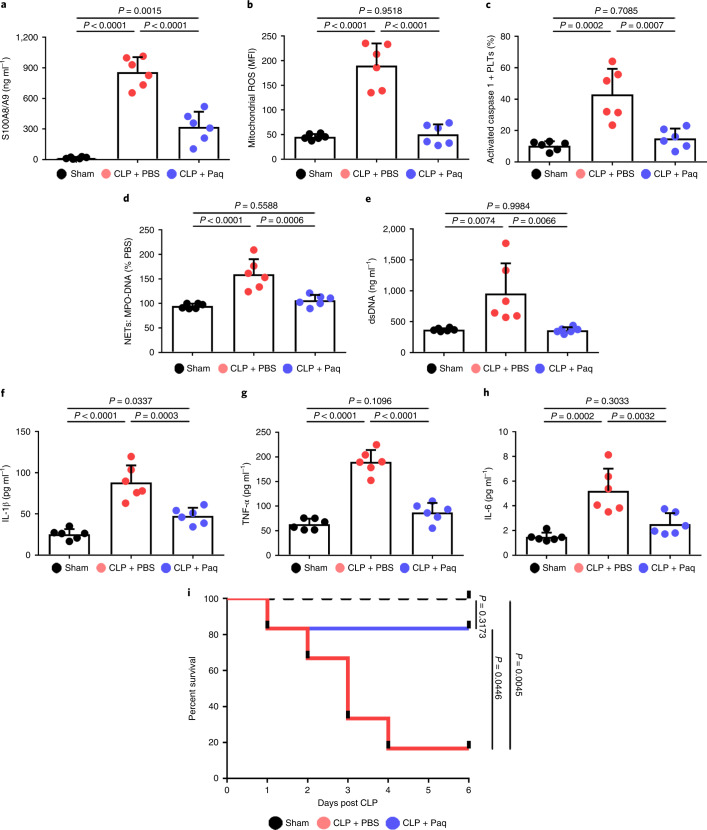

Fig. 6. GSDMD-deficient platelets ameliorate excessive inflammation.

a, Immunofluorescence analysis showing NET formation induced by platelets from Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice treated with S100A8/A9 (n = 5). Cells were stained with Hoechst for DNA (blue), anti-MPO for PMNs or NETs (red) and CD41 for platelets (green). Scale bars, 25 μm and 7.5 μm. b, Bar graphs displaying the levels of MPO–DNA and dsDNA in supernatant of rmS100A8/A9-induced platelets from Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice using PicoGreen fluorescent dye and MPO–DNA–ELISA, respectively (n = 5). c–h, In the CLP-induced sepsis murine model, levels of NETs, heterodimer S100A8/A9 and proinflammatory cytokines in plasma of Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice were detected using ELISA kits after 6 h. c,d, Bar graphs displaying plasma levels of MPO–DNA complexes (c) and dsDNA (d) in mice (n = 5). e, Bar graphs showing plasma levels of heterodimer S100A8/A9 in mice (Gsdmdfl/fl + sham, n = 7; Gsdmdfl/fl + CLP, n = 8; Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre+sham, n = 8; Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre+CLP, n = 6). f–h, Bar graphs showing plasma levels of IL-1β (f), TNF-α (g) and IL-6 (h) in mice (n = 5). i, Survival analysis of Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice and Gsdmdfl/fl mice in CLP-induced sepsis model for 7 d (n = 11). Data were presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b–h) and the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (i).

In addition to inflammation, development of thrombocytopenia during a septic episode is recognized as a significant event associated with multiple organ failure and increased mortality3. Upon admission, 60% of patients with sepsis in whom platelet counts remained low over 28 d developed into severe sepsis (with or without septic shock) (Fig. 1d), consistent with previous studies26. Gsdmdfl/fl PF4-Cre mice demonstrated a small but nonsignificant increase in platelet counts (Extended Data Fig. 10b), suggesting that GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis is not a major contributor to thrombocytopenia. Our data support a key role for GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis in NET formation and inflammation in severe sepsis, but not in thrombocytopenia.

Paquinimod ameliorates inflammation and improves survival

To establish whether a platelet S100A8/A9–TLR4 axis may have therapeutic benefit for inflammation progression in severe sepsis, pharmacologic inhibition of S100A9 (Paquinimod) was introduced in mice with CLP-induced sepsis. In accordance with previous studies14,27, mice were given Paquinimod (10 mg per kg (body weight) per d) (or PBS) by oral gavage for 5 d in the CLP-induced sepsis model. Consistent with the result in patients (Extended Data Fig. 5a and Figs. 2e and 3g), we found that plasma S100A8/A9, mitochondrial ROS and caspase 1 activity were significantly increased in mice with sepsis, but significantly reduced in mice with sepsis and Paquinimod treatment (Fig. 7a–c). Administration of Paquinimod also significantly reduced NET formation in the plasma of mice with sepsis (Fig. 7d,e), and significantly suppressed plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 7f–h). Compared with PBS-treated mice, administration of Paquinimod significantly increased the survival rate in mice with sepsis (Fig. 7i). Taken together, these results indicate that pharmacological inhibition of the S100A8/A9 with Paquinimod suppresses platelet pyroptosis, thereby ameliorating NET formation and inflammation, consequently leading to increased survival in sepsis.

Fig. 7. Paquinimod ameliorates inflammation and improves survival.

In the CLP-induced sepsis model, mice were given Paquinimod (10 mg per kg (body weight) per d) or PBS by oral gavage for 5 d (n = 6 mice per group). a, Bar graphs showing the plasma levels of heterodimer S100A8/A9 in mice. b,c, Bar graphs showing mitochondrial ROS production (b) and caspase 1 activity (c) in murine platelets using FACS analysis. d,e, Quantification of MPO–DNA (d) and dsDNA (e) in the plasma of mice was assessed using PicoGreen fluorescent dye and MPO–DNA ELISA kit, respectively. f–h, Bar graphs displaying the levels of IL-1β (f), TNF-α (g) and IL-6 (h) in plasma of mice. i, Survival analysis of mice with CLP-induced sepsis treated with Paquinimod for 5 d. Data were presented as mean (or fluorescence) ± s.d. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (a–h) or the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test for survival curves (i). CLP + PBS, CLP-induced sepsis mice with PBS; CLP + Paq, CLP-induced sepsis mice with Paquinimod.

Discussion

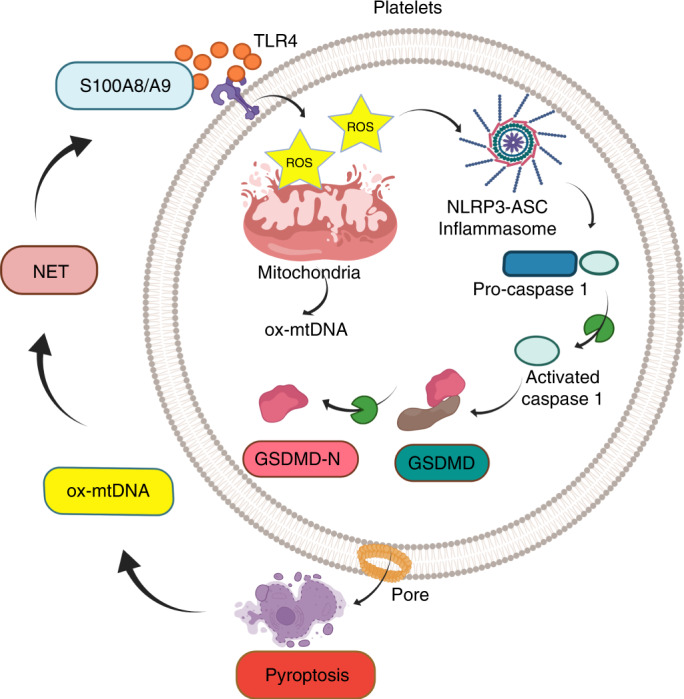

Sepsis is a time-critical emergency that can rapidly spiral into severe sepsis28. Thus, early recognition is required. The underlying mechanisms for such rapid progression are poorly understood, leading to a lack of effective therapies. With the use of three different genetically modified murine models (Gsdmd−/−, Tlr4−/− and S100a9−/−), we now demonstrate that sepsis-derived S100A8/A9 induces GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis via the TLR4/ROS/NLRP3/caspase 1 pathway, leading to the release of ox-mtDNA to mediate NET formation. Furthermore, we find that NETs, in turn, release S100A8/A9 and accelerate platelet pyroptosis, forming a positive feedback loop, thereby amplifying production of proinflammatory cytokines. GSDMD deficiency in platelets or pharmacological inhibition of S100A9 using Paquinimod can break this detrimental feedback loop, ameliorating excessive NET-mediated inflammation in severe sepsis (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Platelet pyroptosis exacerbates NETs and inflammation.

Sepsis-derived S100A8/A9 induces GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis via the TLR4/ROS/NLRP3/caspase 1/GSDMD pathway in severe sepsis. Pyroptotic platelets promote NET formation via ox-mtDNA, whereas NETs, in turn, lead to more platelet pyroptosis via release of S100A8/A9, forming a platelet pyroptosis–NET feedback loop.

The first report of platelet pyroptosis in sepsis

Pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death, has been well documented in different cell types of various diseases6,29. However, it remains uncertain whether pyroptosis ensues in platelets during sepsis. In CLP-induced sepsis, NLRP3 inflammasome was activated in platelets and levels of IL-1β/IL-18 were significantly increased, which was associated with inflammation and multiple organ injury7. Moreover, NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition normalized these cytokine levels and prevented multiple organ injury30. A recent study indicated that the activated NLRP3 inflammasome may be involved in primary immune thrombocytopenia via the ROS–NLRP3–caspase 1 pathway8. By contrast, another study suggested that human and mouse platelets did not express components (NLRP3, ASC, caspase 1 or IL-1β) of the canonical pathways of inflammasome activation31, and the discrepancy may be due to the severity of different diseases. Thus, it is important to verify whether platelets have NLPR3 inflammasomes and if so whether platelet pyroptosis has a pathophysiological role. Using DIA-MS, immunofluorescence and western blotting, we confirmed the expression of NLRP3, ASC and GSDMD in platelets. Furthermore, using platelet-specific Gsdmd KO mice, we provided direct evidence that GSDMD is a key component of platelet pyroptosis in sepsis (Fig. 2).

Our study demonstrates the importance of the S100A8/A9–TLR4 signaling pathway in platelet pyroptosis during sepsis. By blocking TLR4 signaling with TLR4 antibody, Tlr4−/− platelet transfusion or Paquinimod, we suppressed platelet pyroptosis and improved the survival rate in mice with CLP-induced sepsis. A recent study also showed that S100A8/A9 mediated activation of aberrant PMNs and immune disorder through TLR4 in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 (ref. 32). Although many studies have realized the important role of S100A8/A9 in sepsis33,34, the underlying mechanism was not clear. Here, we found the role of S100A8/A9 in platelet pyroptosis during severe sepsis via the TLR4 signaling pathway.

The clinical outcomes of pediatric severe sepsis, including excessive inflammation and thrombocytopenia, are major causes of mortality3. Our finding that substantial platelet pyroptosis leads to increased IL-1β release (Fig. 2f) is supported by recent studies showing that platelet-derived IL-1β mediates endothelium permeability in dengue35, which amplifies proinflammatory cytokine production in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis (Fig. 1b). However, in our cohort, the platelet counts in patients with severe sepsis remained low after admission (Fig. 1d). Thrombocytopenia in severe sepsis is caused by altered platelet production, hemophagocytosis, antibodies, disseminated intravascular coagulation or platelet scavenging in the circulation due to platelet–leukocyte or platelet–pathogen interactions, vessel injury or desialylation36. A recent report suggested that elevated angiotensin II induced platelet apoptosis, leading to sepsis-associated thrombocytopenia37. In our study, GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis slightly reduced platelet counts, but was not a major contributor to thrombocytopenia in sepsis.

A positive feedback loop between platelets and NETs

Crosstalk between PMNs and platelets depends on cell-to-cell contact and secreted substances, which activate each other38. Activated platelets have been shown to be potent activators of NETs by platelet-derived high mobility group box 1, von Willebrand factor, platelet factor 4 and exosomes38,39. Clark et al. reported that platelet TLR4 could induce robust PMN activation and NET formation to ensnare bacteria18, suggesting a bacterial trapping mechanism in severe sepsis. Another study has also indicated that platelet TLR4 can trigger NET formation; histones 3 and 4 released from NET can, in turn, enhance platelet activation in a continuous loop40. In our study, using Tlr4 deficiency in platelets and pharmacological inhibition of S100A9 by Paquinimod, we demonstrated that platelet pyroptosis can ensue in severe sepsis via S100A8/A9–TLR4 signaling. NETs have a key role in killing pathogens, although excessive formation of NETs might lead to tissue damage38,41. It has also been reported that NETs release S100A8/A9 (ref. 14). Here, we propose that activated platelets promote NET formation to kill pathogens during the early stage of sepsis. However, with the occurrence of platelet pyroptosis in the later stage of sepsis, excessive formation of NETs exacerbates the inflammatory response (for example, release of S100A8/A9), which further induces platelet pyroptosis, forming a positive feedback loop between platelets and NETs (Figs. 4–6). Our study provides an insight into the mechanism of S100A8/A9-induced platelet pyroptosis inducing NET formation in sepsis.

Therapeutic implications in severe sepsis

Rapidly dysregulated immune systems and prolonged excessive inflammation induce multiorgan failure and increased mortality42. Standard treatments require a combination of antimicrobial therapy, supportive care including fluid therapy, and/or vasoactive pressor medications1. Despite such therapies, 60% of our recruited patients with sepsis developed into severe complications, suggesting that alternative therapies are urgently needed for such severe sepsis. The potent disease-inhibitory effects of Paquinimod have been suggested for experimental models of autoimmune and inflammation disease43 and for systemic lupus erythematosus44. Moreover, a recent study has suggested that inhibition of S100A9 with Paquinimod may reduce mortality and improve learning and memory performance in mice with sepsis45. We now provide an unusual mechanism involving a platelet pyroptosis positive feedback loop that contributes to the development of severe sepsis. In mice with CLP-induced sepsis, our results showed that administration of Paquinimod effectively suppressed platelet pyroptosis and NET formation, with a concomitant reduction in inflammation, resulting in an improved survival rate (Fig. 7). Therefore, targeting the S100A8/A9–TLR4 pathway may provide adjunct therapy for inflammation progression in patients with sepsis. However, we should note that the reduction in inflammation induced by Paquinimod could also be via additional mechanisms (for example, inhibition of S100A9 by Paquinimod attenuated neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment via suppressing microglia M1 polarization in CLP or LPS-induced sepsis survivor mice45) and requires further investigation.

In summary, S100A8/A9 induces GSDMD-dependent platelet pyroptosis via a TLR4/NLRP3 pathway in severe sepsis, which exacerbates NET formation via the release of ox-mtDNA. NETs, in turn, release S100A8/A9, thereby inducing platelet pyroptosis in severe sepsis (Fig. 8). This positive feedback mechanism contributes to the amplification of inflammation following infection. Thus, assessment of platelet pyroptosis may serve as a diagnostic and prognostic tool for the progression of severe sepsis. Particularly in patients with severe sepsis and with substantial platelet pyroptosis, targeting S100A8/A9 or platelet-specific GSDMD may provide a much needed adjunct therapy.

Methods

Patient recruitment and isolation of human platelets

We recruited 93 pediatric sepsis patients (aged 0–18 years) and 75 age-matched HS, from Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, China between November 2019 and August 2021 (Supplementary Table 1). According to guidelines from the Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Congress46, pediatric sepsis is defined as a suspected or proven infection caused by any pathogen or a systemic inflammatory response syndrome associated with a high probability of infection. The age-specific vital signs and laboratory variables of pediatric sepsis were divided into six distinct categories as listed in Supplementary Table 5 (ref. 47). In accordance with the clinical spectrum of severity, it encompasses sepsis (systemic inflammatory response syndrome in the presence of infection), severe sepsis (sepsis in the presence of cardiovascular dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome or dysfunction of two or more organ systems) and septic shock (sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction persisting after at least 40 ml per kg (body weight) of fluid resuscitation in 1 h). For subjects aged 18 and under informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from each subject (Human Investigation Committee No. 2019-44102-1) and the human studies conformed to the principles set out in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

After admission, all patients with sepsis were treated with antibiotics including cephalosporin, vancomycin and broad-spectrum penicillin. Venous blood samples were drawn from patients with sepsis when they were enrolled on the first day. Venous blood samples (3 ml) were drawn from HS and patients with severe sepsis using blood collection tubes containing 3.8% trisodium citrate (w/v). Briefly, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was centrifuged at 250g at 25 °C for 15 min. PRP was then treated with 100 nM prostaglandin E1 (Sigma, catalog no. 745-65-3) and centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, the platelet pellet was washed and resuspended with 3 ml Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Gibco, catalog no. 14025092). The purity of the platelet preparation was determined by FACS (BD FACSCanto; BD Biosciences) analysis using platelet markers (>90% fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-human CD41a, 1:200; BD Biosciences, catalog no. 555466).

Animals and treatment

The Gsdmdflox/flox murine model used in this study was designed and developed by Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. Briefly, the targeting construct was designed to flank exon 3 with loxP sites and a pGK-Neomycine-polyA cassette. The targeting vector was electroporated into C57BL/6J embryonic stem cells (ES), which were used to perform double drug selection with G418 and ganciclovir for screening the homologous recombination clones. ES clones with the correct homologous recombination were identified by PCR and confirmed by sequencing. Positive ES cell clones were expanded and microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate chimeric offspring. Platelet-specific Gsdmd KO mice (Gsdmdflox/flox PF4-Cre) were generated by crossing Gsdmd flox and PF4-Cre mice. Mice were genotyped using primers P8 (5′-AGGGCGTCAGATCTCATTACAG-3′) and P9 (5′- TTCCCATCGACGACATCAGAGACT-3′).

The global S100a9-deficient (S100a9−/−) mouse model used in this study was designed and developed by Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. Briefly, Cas9 messenger RNA was in vitro transcribed with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two single guide RNAs targeted to delete exons 2–3 were in vitro transcribed using the MEGAshortscript Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. B135410). One sgRNA targeted to intron 1 of gene S100a9 was 5′- CAGTGGCCAGAGACTAGGTCAGG-3′. The other sgRNA targeted to the 3′ downstream sequence of gene S100a9 was 5′- GGTTCTCACATGAATGGGAATGG-3′. In vitro transcribed Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs were injected into zygotes of C57BL/6J mice, which were transferred to pseudopregnant recipients. The obtained F0 mice were validated by PCR and sequencing using the primer pairs: F (5′-TCAGATGCAAGGGGGAGAATG-3′) and R (5′-GGGGGTCACTTGATCTCTTTGGTC-3′). Positive F0 mice were chosen and crossed with C57BL/6J mice to obtain F1 heterozygous S100a9−/− mice. The genotype of the F1 mice was identified by PCR and confirmed by sequencing. Male and female F1 heterozygous mice were intercrossed to produce homozygous S100a9−/− mice.

Global Tlr4-deficient (Tlr4−/−) mice, mT/mG:PF4-Cre mice and WT mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice. Genotyping was performed via PCR using standard methods. To block the S100A8/A9–TLR4 axis, 5-week-old mice were gavaged with Paquinimod (synonym: ABR-215757; 10 mg per kg (body weight) per d; MedChemExpress, catalog no. HY-100442) or PBS (HyClone, catalog no. SH30258.01) every 24 h over 5 d (n = six per group). To build a murine septic model, 5-week-old mice were induced by CLP with a 19-gauge needle. Briefly, the cecum was ligated at the designated position for the desired severity grade, and ligation of the ileocecal valve was subjected to a single through-and-through puncture with a 19-gauge needle. Sham-operated mice underwent the same surgical procedure except for ligation and perforation of the cecum. To build the LPS-induced septic shock model, 5-week-old mice (n = 6 per group) were injected with a single dose of LPS (20 mg per kg; Sigma, catalog no. L4391). All mice (5 weeks old, male) were housed at a density of three per cage in a controlled environment at a constant temperature of 18–22 °C and a humidity of 55%–60% on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. After acclimation for 7 d, mice were freely supplied with food and water every day. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangzhou Medical University (No. SYXK2018-266). All mouse experiments complied with the principle of animal protection, welfare, ethics and 3R (replacement, reduce and refine).

Data-independent acquisition

Protein extraction and digestion

Protein extraction was performed as follows. Purified platelets were obtained from patients with severe sepsis and HS. Appropriate amounts of L3 lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0) without SDS were added to the samples, followed by 2 mM ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid (Amersco) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and incubated on ice for 5 min. Dithiothreitol (10 mM ; Amersco) was then added. Samples were ground with a grinder (60 Hz, 2 min) and centrifuged at 25,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Next 10 mM dithiothreitol was added, and the mixture was reacted at 56 °C for 1 h. Next, 55 mM iodoacetamide was added and reacted for 45 min in the dark at room temperature. Quantitative electrophoresis was then performed. The concentration of protein extract was measured using the Bradford assay48. The purity of the extracted proteins (10 μg) was verified and the proteins were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining. For protein enzymatic digestion, 100 μg of protein per sample was digested with 2.5 μg of trypsin enzyme (protein/enzyme ration of 40:1) for 4 h at 37 °C. Finally, enzymatic peptides were desalted using a Strata X column and vacuum dried prior to MS.

Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) and DIA analysis by nanoscale liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry

All proteomic experiments were performed using an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC liquid chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In accordance with previous studies49,50, the dried peptide samples were redissolved with a buffer comprising mobile phase A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid v/v), centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant from the samples was first enriched in the trap column and desalted. The supernatant from the samples was loaded onto a tandem column (150 μm internal diameter, 1.8 μm column size, 35 cm column length), and separated at a flow rate of 500 nl min−1 using the following effective gradient: 5% mobile phase B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid v/v) at 0–5 min; increase in mobile phase B from 5% to 25% at 5–120 min; increase in mobile phase B from 25% to 35% at 120–160 min; increase in mobile phase B from 35% to 80% at 160–170 min; 80% mobile phase B at 170–175 min; and 5% mobile phase B at 175–180 min.

For DDA analysis, LC separated peptides underwent nano-electrospray ionization and were injected into a tandem MS Q-Exactive HF X (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with DDA detection mode. The MS parameters were as follows: 1.9 kV ion source voltage; 350–1,500 m/z scan range, 120,000 resolution, 100 ms maximal injection time (MIT), 3 × 106automatic gain control (AGC) target. The high collision energy desolation coupled to tandem mass spectrometry parameters were: 28 collision energy normalized collision energies; 30,000 resolution, 100 ms MIT, 1 × 105 AGC target, 30 s dynamic exclusion duration, isolation window 2.0 m/z. For DIA analysis, the same nano-LC system and gradient was used as for the DDA analysis. The main settings were: MS 400–1,250 m/z scan range; 120,000 resolution, 50 ms MIT; 3 × 106 AGC target, 45 loop count (400–1,250 m/z). For high collision energy desolation coupled to tandem mass spectrometry, fragment ions were scanned in Orbitrap, 30,000 resolution, automatic MIT, 1 × 106 AGC target, 45 loop count, 30 s dynamic exclusion duration, stepped normalized collision energies: 22.5, 25, 27.5.

DIA-MS data analysis

The spectral library was generated from MaxQuant (v.1.5.3.30)51 DDA search results using Spectronaut with default settings. With the established spectral library, the acquired DIA data were processed and analyzed by Spectronaut (12.0.20491.14.21367)52, with retention time prediction type set to dynamic indexed retention time, decoy generation set to scrambled, peptide and protein level Q-value cutoff set to 1% and normalization strategy set to local normalization. The precursor level of the Spectronaut normal report was exported, and downstream data processing including log-transformed intensities, median normalization across conditions and protein summarization were performed using MSstats53. Based on the preset comparison groups, the mixed linear model in MSstats R package (v.3.2.1) was employed to assess DEPs (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.2/bioc/html/MSstats.html). A DIA secondary fragment ion was used for the peak areas. A minimum of one unique peptide and at least three transitions per peptide were used to obtain the peak area. For bioinformatics analysis, identified proteins from platelets were annotated and classified into pathways using the Gene Ontology (GO) database (2018 version), Reactome database (2016 version) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (2019 version), respectively. Criteria of fold change >2 and P < 0.05 were used to determine statistically significant differences. A heatmap of all significant DEPs was performed using the Euclidean distance and hierarchical cluster.

TEM

To distinguish morphologic features of pyroptosis from apoptosis, platelets were examined by TEM. Platelets were fixed and stained as previously described54. The ultrastructural sections were examined with the TEM (Japan Electron Optics Laboratory, JEM-1400), followed captured with an Advantage CCD camera (MORADA, EMSIS) using RADIUS AII 2.2 (build 21230) software.

In vivo platelet depletion and transfusion assay

Blocking TLR4 signaling by transfusion of Tlr4−/− platelets into WT mice can be an effective method to verify the role of TLR4 in platelets during sepsis55,56. Briefly, before the experiments, 5-week-old mice were injected intravenously at 5 μl per mouse with rabbit anti-mouse thrombocyte polyclonal antibody (Mybiosource, catalog no. MBS524066) or normal saline (200 μl). After 24 h post ablation, blood samples (approximately 0.8 ml) were directly obtained from the right cardiac ventricle into 3.8% trisodium citrate in mice. The obtained blood samples were diluted with an equal volume of HBSS buffer. PRP was centrifuged at 250g and 25 °C for 5 min. PRP with 100 nM prostaglandin E1 was recentrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, the platelet pellet was washed and resuspended in 3 ml HBSS. In accordance with Xu et al.57, 1.2 × 107 purified platelets (200 μl, 6 × 1010 platelets per liter) were transfused intravenously into recipient mice. Tlr4−/− platelets and WT platelets were transfused intravenously into recipient mice, followed by LPS-induced sepsis for 6 h (n = 6 per group). Mice were euthanized postinfection using chloral hydrate in PBS at a dose of 400–500 mg per kg (body weight), and then used for retro-orbital blood drawls. After finishing all experiments, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Platelet count in whole blood was measured using a hematology analyzer55 (Sysmex Corporation, XN-350).

To monitor transfused platelet dynamics, purified platelets were prepared and a total of 1.2 × 107 purified platelets (200 μl, 6 × 1010 platelets per liter) from Tlr4−/− or WT mice were transfused intravenously into mT/mG:PF4-Cre mice, in which PF4-Cre drives membrane GFP expression in megakaryocytes and platelets, whereas all other cells are labeled with mT24. After depletion, platelet counts in mice transfused with WT or Tlr4−/− platelets were detected at 0, 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h using a hematology analyzer and FACS stained with PE-Cy7 anti-mouse CD41 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:200, catalog no. 25-0411-82).

Isolation of human and murine PMNs

Human PMNs were obtained with Ficoll Hypaque gradient centrifugation (δ = 10,771, Sigma), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The red blood cell layer was then ablated by hypotonic lysis. Cell suspensions contained 95% PMNs, as determined by FACS (APC anti-human CD66b antibodies; BioLegend, 1:200, catalog no. 305118). Murine PMNs were obtained with Ficoll Hypaque gradient centrifugation (δ = 1,090, Sigma), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The red blood cell layer was then ablated by hypotonic lysis. Cell suspensions contained 90% PMNs, as determined by PE anti-mouse Ly6G (BioLegend, 1:200, catalog no. 127607) staining and FACS. Human and murine PMNs were washed in PBS and resuspended with RPMI 1640 (in 2% FBS; Gibco, catalog no. 10099141C) and used for immunofluorescence assays.

NET formation and imaging assay

Purified human PMNs (2 × 105 per ml) were prestimulated with PMA (50 nM; Sigma, catalog no. P1585)58,59 that used as classical NET stimuli for subsequent assessments, resting platelets or pyroptotic platelets (1 μg ml−1 rhS100A8/A9-induced; BioLegend, catalog no. 753404) (0.04 × 105 per ml) for 4 h. To further confirm that pyroptotic platelets triggered NET formation, purified murine PMNs (2 × 105 per ml) were cocultured with resting WT platelets or with rmS100A8/A9-induced (1 μg ml−1; BioLegend, catalog no. 765506) Tlr4−/− platelets (0.04 × 105 per ml) for 4 h. Use of S100A8/A9 was determined according to previous studies14.

Measurement of NETs

MPO–DNA complexes and dsDNA in plasma of human/mice and medium supernatant were detected by anti-MPO polyclonal (biotin conjugated) primary antibody (Bioss, 1:500, bs-4943R-Biotin) with a Cell Death Detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Roche, 11774425001)60 and Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA reagent (Invitrogen, catalog no. P7581) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The data were presented as percent control ± s.d., arbitrarily set at 100%.

ELISA

Levels of S100A8/A9, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 in human plasma (S100A8/A9, CUSABIO CSB-E12149; IL-1β, BOSTER EK0392; IL-6, CUSABIO CSB-E04638h; TNF-α, CSB-E04740h) or plasma from mice (S100A8/A9, CUSABIO CSB-EQ013485MO; TNF-α, CSB-E04741m; IL-6, CSB-E04639m; IL-1β, EK0394) were detected using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To measure the release of IL-1β from septic platelets through pore formation, purified platelets (from HS and patients with sepsis, 500 μl, 1 × 108 platelets per ml) were incubated at room temperature. After 12 h, IL-1β in the supernatant was measured using ELISA kits. DNA 8-OHdG was measured using a general 8-OHdG ELISA kit (Develop, dl-8-OHdG-Ge) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Platelets or PMNs were fixed and incubated with antibodies including anti-NLRP3 (Abcam, 1:100, catalog no. ab4207), anti-ASC (Novusbio, 1:100, catalog no. NBP1-78978), anti-CD41 (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab134131), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse CD41 (BioLegend, 1:200, catalog no. 133908), Hoechst (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:3,000, catalog no. H3570), anti-myeloperoxidase (Genetx, 1:200, catalog no. gtx75318), anti-myeloperoxidase (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab208670) and anti-histone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17, 1:200, Abcam, catalog no. ab5103) at 4 °C overnight. Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-goat antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150135), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150079), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150084), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150116), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody (BioLegend, 1:200, catalog no. 405508), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150077) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150113). Cells were captured using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (×63 oil immersion lens, Leica SP8).

Flow cytometric analysis

The purity of the platelet preparation was determined by FACS analysis using FITC anti-human CD41a (BD Biosciences, 1:200, catalog no. 555466) and PE anti-human CD45 (eBioscience, 1:200, catalog no. 12-9459-42) antibodies. The caspases 1, caspase 3/7, LC3B and GSDMD activity of platelets was determined using a Pyroptosis/Caspase-1 Assay Kit (Green) (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, 1:200, catalog no. 9146), FAM-FLICA Caspase-3/7 Assay Kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, 1:200, catalog no. 94), FLICA 660 Caspase-3/7 Assay Kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, 1:200, catalog no. 9125), LC3B antibody Alexa Fluor 405 (Novus Biologicals, 1:200, catalog no. NB100-2220AF405) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Abcam, 1:200, catalog no. ab150084). Data were collected from 20,000 platelets on a BD FACSCanto and analyzed using FlowJo-V10 software.

Measurement of mitochondrial function

∆Ψm was detected using 100 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (Invitrogen, catalog no. T668) by FACS. ROS levels were measured by a mitochondrial ROS detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mitochondrial superoxide production was labeled with 5 µM MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen, catalog no. M36008) for 30 min at 37 °C. Suspensions of purified platelets (isolated from HS and patients with sepsis, 500 μl, 1 × 108 platelets per ml) were incubated with 5 mM MitoTempo for 1 h. Caspase 1 activity was then determined by FACS analysis.

Western blotting

Cells were collected and lysed using protein lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore). Total proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: anti-GSDMD (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000, catalog no. 96458S), anti-NLRP3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000, catalog no. 15101S), anti-TMS1/ASC (Abcam, 1:1,000, catalog no. ab151700), anti-pro-caspase 1 + p10 + p12 (Abcam, 1:1,000, catalog no. ab179515), α-actinin (Abcam, 1:3,000, catalog no. ab68194) and β-actin (Abcam, 1:3,000, catalog no. ab6276). The membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (1:2,000). Relative intensities were quantified using Image Lab (Bio-Rad) using enhanced chemiluminescence (Millipore).

Statistical analysis

For the experimental data, statistical analyses and graphics production were performed using GraphPad Prism v.8.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and s.d. or median with interquartile range. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data. For normally distributed data, comparisons between two groups were analyzed using unpaired nonparametric Student’s t-test. Comparisons between more than two groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. For data that were not distributed normally, values were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test and comparisons between more than two groups were performed using Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple test. Comparisons between more than two groups were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. Categorical variables were presented as frequency rates and percentages and were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Pearson’s correlation test was used to analyze the linear relationship between two variables. The log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used for survival curves. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–5.

Gsdmd_flox_PLTs_video_1.

Gsdmd_KO_PLTs_video_2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 82100141, 82101655, 82022003, 81970437 and 81903605), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant no. 2021A1515011304), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (Grant nos. 202102020164 and 202102010151), Guangzhou Science and Post-doctoral Research Project (Grant no. 2180157 and 011302031), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M700934) and Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center/Guangzhou Institute of Pediatrics (Grant nos. 3001076 and 3001149).

Extended data

Source data

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed western blots.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed western blots.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed western blots and/or gels.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Author contributions