Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a relatively uncommon cancer, with approximately 60 430 new diagnoses expected in 2021 in the US. The incidence of PDAC is increasing by 0.5% to 1.0% per year, and it is projected to become the second-leading cause of cancer-related mortality by 2030.

OBSERVATIONS

Effective screening is not available for PDAC, and most patients present with locally advanced (30%–35%) or metastatic (50%–55%) disease at diagnosis. A multidisciplinary management approach is recommended. Localized pancreas cancer includes resectable, borderline resectable (localized and involving major vascular structures), and locally advanced (unresectable) disease based on the degree of arterial and venous involvement by tumor, typically of the superior mesenteric vessels. For patients with resectable disease at presentation (10%–15%), surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, irinotecan, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) represents a standard therapeutic approach with an anticipated median overall survival of 54.4 months, compared with 35 months for single-agent gemcitabine (stratified hazard ratio for death, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.48–0.86]; P = .003). Neoadjuvant systemic therapy with or without radiation followed by evaluation for surgery is an accepted treatment approach for resectable and borderline resectable disease. For patients with locally advanced and unresectable disease due to extensive vascular involvement, systemic therapy followed by radiation is an option for definitive locoregional disease control. For patients with advanced (locally advanced and metastatic) PDAC, multiagent chemotherapy regimens, including FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel, and nanoliposomal irinotecan/fluorouracil, all have a survival benefit of 2 to 6 months compared with a single-agent gemcitabine. For the 5% to 7% of patients with a BRCA pathogenic germline variant and metastatic PDAC, olaparib, a poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADB]-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, is a maintenance option that improves progression-free survival following initial platinum-based therapy.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Approximately 60 000 new cases of PDAC are diagnosed per year, and approximately 50% of patients have advanced disease at diagnosis. The incidence of PDAC is increasing. Currently available cytotoxic therapies for advanced disease are modestly effective. For all patients, multidisciplinary management, comprehensive germline testing, and integrated supportive care are recommended.

Approximately 60 430 new diagnoses of pancreatic cancer are anticipated in the US in 2021.1 The incidence is rising at a rate of 0.5% to 1.0% per year, and pancreatic cancer is projected to become the second-leading cause of cancer death by 2030 in the US.1,2 Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for the majority (90%)of pancreatic neoplasms, and the other subtypes include acinar carcinoma, pancreaticoblastoma, and neuroendocrine tumors. Most patients with pancreatic cancer present with nonspecific symptoms at an advanced stage with disease that is not amenable to curative surgery.1 No effective screening exists. The 5-year survival rate approached 10% for the first time in 2020, compared with 5.26% in 2000.1 The survival improvements have been modest and attributed primarily to multiagent cytotoxic therapies.3–5 Recently, comprehensive germline and somatic genomic sequencing became standard of care for small subgroups of patients with targeted treatment opportunities.6,7 Olaparib, a poly (adenosine diphosphate[ADB]-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, can prolong cancer control in patients with a BRCA1/2 pathogenic germline variant.8,9 This review summarizes current evidence regarding pathobiology, diagnosis, and management of PDAC.

Methods

A PubMed search was performed for English-language articles describing randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews of pancreatic cancer published between January 1, 2010, and July 5, 2021. We identified 43 randomized clinical trials, 85 meta-analyses, and 171 systematic reviews. The authors selected articles for inclusion, prioritizing recent randomized clinical trials of higher quality based on rigor of study design, adequate sample size, and long-term follow-up. A total of 24 randomized clinical trials, 4 meta-analyses, 3 systematic reviews, 5 guideline recommendations, and 37 observational and cohort studies, including publications prior to 2010, were included.

Epidemiology and Screening

PDAC is the third-leading cause of cancer mortality in the US and the seventh-leading cause worldwide (Box).10The median age at diagnosis in the US is 71 years, and PDAC is slightly more common in men than in women (5.5 vs 4.0 per 100 000 individuals).11At presentation, 50% of patients have metastatic disease, 10% to 15% have localized disease amenable to surgery, and the remainder (30%–35%) have locally advanced mostly unresectable disease due to the extent of tumor-vascular involvement.1 Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms (PanINs) refer to precancerous lesions, of which a small fraction may progress to high-grade dysplasia and PDAC.12 Low-grade PanINs are common and their potential to transform into a malignancy is unclear. In a retrospective review of 584 patients who underwent a pancreatectomy for non-PDAC (median age, 59 years), 153 patients (26%) were identified with PanINs; most patients had low-grade PanIN-1 (50%) or PanIN-2 (41%) and 13 (8%) had PanIN-3. None of the patients with PanIN-3 developed cancer, whereas 1 patient with PanIN-1B developed cancer in 4.4 years.13 Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms are more common precancerous cystic lesions than PanINs and can arise in either the main or branch pancreatic duct. In a cohort study of 605 patients who underwent a surgical procedure for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, the malignancy rate for final pathology in main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms was 68%, whereas in a different cohort study of 1404 patients with branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, only 15% evolved to PDAC over 15 years.14–16 Annual imaging surveillance is recommended; however, there is no consensus as to the optimal surveillance method or frequency of assessment.15,17 For asymptomatic average-risk individuals, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine screening for PDAC.18

Modifiable and Inherited Risk Factors

Among lifestyle risk factors, current cigarette smoking has the strongest association with PDAC. A meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies that included 6507 patients with pancreatic cancer and 12 890 control patients reported an odds ratio (OR) of 1.74 (95% CI, 1.61–1.87) for the association of current smoking with pancreatic cancer (absolute rates not reported).19,20 There was also a modest association of alcohol use with PDAC, when intake exceeded 30 g per day (approximately 3 drinks per day), according to a meta-analysis of 19 prospective studies reporting outcomes from 4 211 129 individuals (relative risk, 1.22 [95% CI, 1.03–1.45]; absolute rates not reported).21 Chronic pancreatitis was associated with a 13-fold increased risk for PDAC in a pooled analysis of 14 prospective cohort studies of 862 664 individuals (relative risk, 13.3 [95% CI, 6.1–28.9]).22 Obesity, defined as a body mass index in the fifth quintile (highest 20%), was also associated with an increased risk of PDAC (incidence, 14.1 vs 5.7 per 100 000 person-years; adjusted relative risk, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.04–2.29]) in a Norwegian analysis of 940 060 individuals.23 Diets of processed meat, high-fructose beverages, and saturated fat were associated with obesity, diabetes, and pancreatic cancer.24 The incidence of PDAC in people younger than 30 years is increasing. The annual incidence of PDAC increased with younger age from 1995 to 2014, from 0.77% (95% CI, 0.57%–0.98%) for those aged 45 to 49 years, to 2.47% (95% CI, 1.77%–3.18%) for those aged 30 to 34 years, to 4.34% (95% CI, 3.19%–5.50%) for those aged 25 to 29 years, consistent with an increase in younger patients.24 This observation may be related to increasing rates of obesity and diabetes, which are potentially modifiable risk factors for PDAC.

About 3.8% to 9.7% of patients with PDAC have pathogenic germline gene variants that increase susceptibility to PDAC. These variants occur mostly in DNA damage repair genes.25–27 The most common variants in PDAC include BRCA2, BRCA1 (hereditary breast and ovary cancer syndrome), and ATM (ataxia telangiectasia syndrome). Germline BRCA2 variants are associated with an increased risk for PDAC (OR, 9.07 [95% CI, 6.33–12.98]) more commonly than BRCA1 (OR, 2.95 [95% CI, 1.49–5.60]) or ATM variants (OR, 8.96 [95% CI, 6.12–12.98]).28 Uncommon (1% of patients with PDAC) but therapeutically important inheritable germline variants also occur in PDAC in mismatch repair deficiency genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 as part of Lynch syndrome.29 In 2019, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommended that all patients newly diagnosed with PDAC undergo germline testing with a gene panel including BRCA1/2, ATM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.30 Healthy family members are also recommended for genetic counseling if an individual is determined to be at high risk based on the following criteria: a first-degree relative with early-onset PDAC (<50 years), more than 1 first-degree family member with PDAC, or a known pathogenic germline gene variant associated with PDAC. For optimal genomic testing, a multigene panel is recommended over traditional hierarchical single-gene testing for efficiency and cost.30

Molecular Profiling of Pancreatic Cancer

The pathophysiology of PDAC is characterized by complex multistep genetic alterations. In the precancerous state, PanINs acquire cumulative genetic insults resulting in instigating oncogenes that are responsible for the initiation and maintenance of PDAC, including KRAS, CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4.31 KRAS variants occur as an early step in PDAC development (low-grade PanINs) and are identified in 90% to 92% of individuals with PDAC. As PanIN progresses to grade 2 or 3, additional gene variants in CDKN2A, TP53, and/or SMAD4 are acquired.31 Collectively, these genomic alterations contribute to multifaceted defects in tumor suppressor mechanisms resulting in dysregulated growth signaling and inflammation, which are key aspects of PDAC. Additionally, about 10% to 15% of PDACs acquire variants in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling genes related to large-scale structural genomic aberrations.32

Recent advances in molecular pathology and classification of PDAC have affected clinical practice.32–35 One example is subtyping of PDAC into “basal-like” or “classical” type by RNA transcriptional analyses.34–36 The classical subtype of PDAC is characterized by a higher level of differentiation, fibrosis, and inflammation, whereas the basal-like subtype is associated with a poorer clinical outcome and loss of differentiation. The value of selecting therapies based on PDAC subtypes is under investigation in prospective trials.37,38 Whole-genome structure analysis has provided insight into genomic instability and the relationship with DNA maintenance genes (BRCA1/2 and PALB2) and, specifically, genetic signature 3. These findings suggest that platinum-based therapy and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors may be effective for patients with pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and PALB2.32 One prospective trial building on these observations has led to the approval of the targeted agent olaparib in select patients with BRCA1/2 pathogenic germline variants.8,9,33,39,40

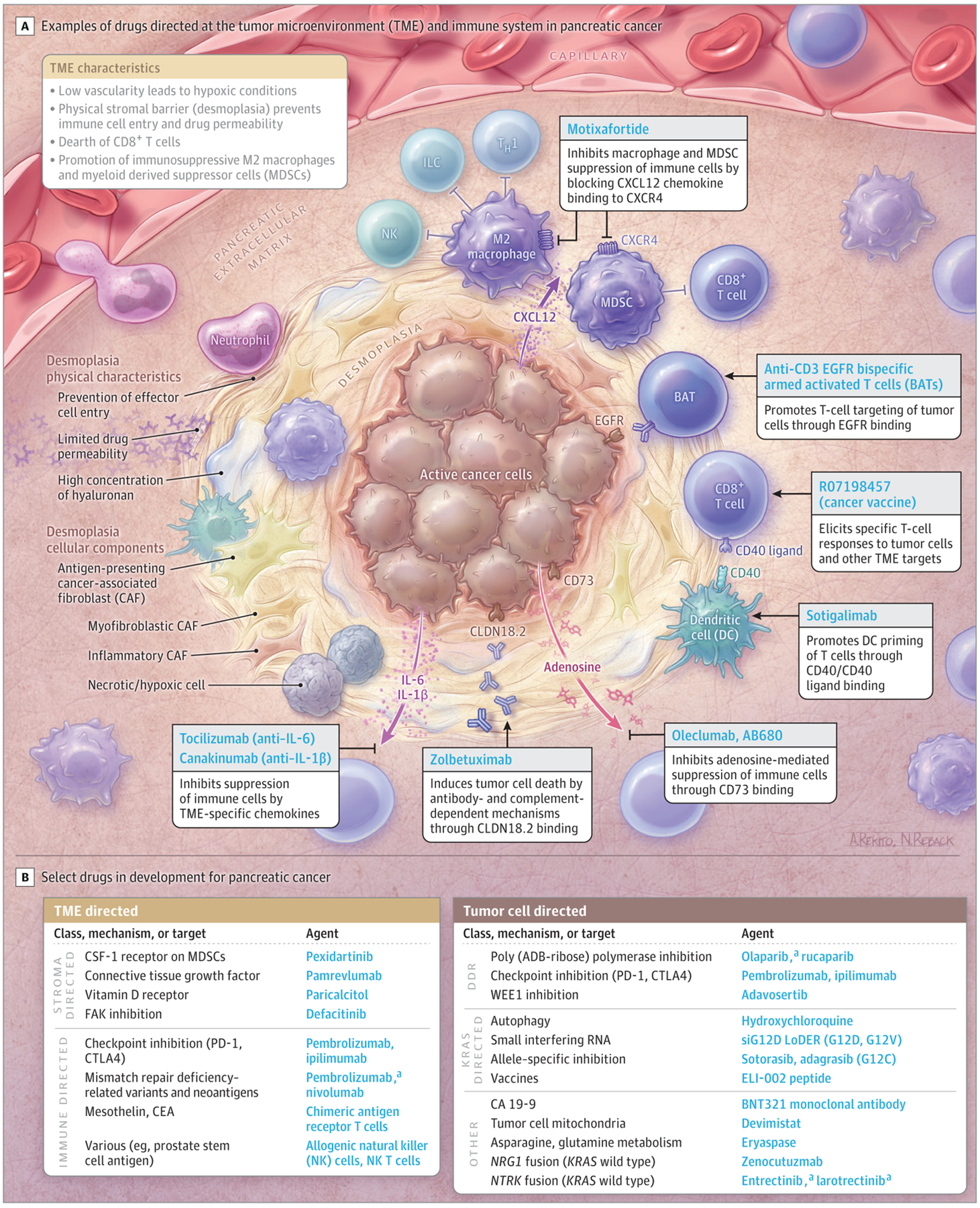

Clinical Significance of Immune Tumor Microenvironment

PDAC cells exist in an impenetrable network, also known as the tumor microenvironment (TME), which comprises immune cells, cytokines, metabolites, fibroblast, and desmoplastic stroma rich in hyaluronan. The immunosuppressive TME helps PDAC cells evade host immune surveillance. A potent host anticancer T cell memory against PDAC neoantigens has been identified in 82 select long-term survivors of PDAC who lived more than 3 years after undergoing surgery.41 However, in most patients, the TME suppresses the immune system and antagonizes host anticancer immunity and promotes carcinogenesis. The TME of PDAC is characterized by limited infiltration of CD8+ T cells and an abundance of myeloid derived suppressor cells, tumor-associated macrophages, tumor-associated neutrophils, and regulatory T cells. Additionally, the extracellular matrix, characterized by distinctive desmoplasia stemming from cancer-associated fibroblast, matrix metalloproteinases, and hyaluronan, may promote the immunosuppressive characteristic of the TME. These multifaceted compartments are viewed as responsible, in part, for the resistance to most single-agent therapeutic approaches.42–45 Many clinical trials that are underway are designed to increase the sensitivity of PDAC to the immune system with the goal of overcoming the immunosuppressive characteristic of the TME (eTable 1 in the Supplement).46,47

Clinical Manifestations and Presentation of Pancreatic Cancer

The presenting symptoms of PDAC are often vague and nonspecific. Most patients present with either locally advanced (unresectable) or metastatic disease. In a prospective cohort study of 391 participants 40 years or older who were suspected of having PDAC, initial symptoms were compared among 119 participants who were ultimately diagnosed with PDAC, 47 with other cancers, and 225 without PDAC. In this study, no initial symptoms differentiated participants diagnosed with PDAC from those who ultimately did not have PDAC, including the 3 most common symptoms: decreased appetite (28% vs 31%), indigestion (27% vs 39%), and change in bowel habit (27% vs 22%).48 Most tumors (approximately 70%) arise at the head of the pancreas and often present with biliary obstruction leading to dark urine (49%), jaundice (49%), appetite loss (48%), fatigue (approximately 51%), weight loss (approximately 55%), and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (25%). In contrast, individuals with body and tail pancreatic cancers present with more nonspecific symptoms, including abdominal pain, back pain, and cachexia-related symptoms (appetite loss, weight loss, fatigue). New-onset or worsening of preexisting diabetes may be a sign of PDAC and warrants evaluation.49 Rarely, acute pancreatitis can be a primary manifestation of PDAC and occurs in about 3% of patients with newly diagnosed PDAC. Referral to an experienced multidisciplinary team is recommended.

Diagnosis and Evaluation of Pancreatic Cancer

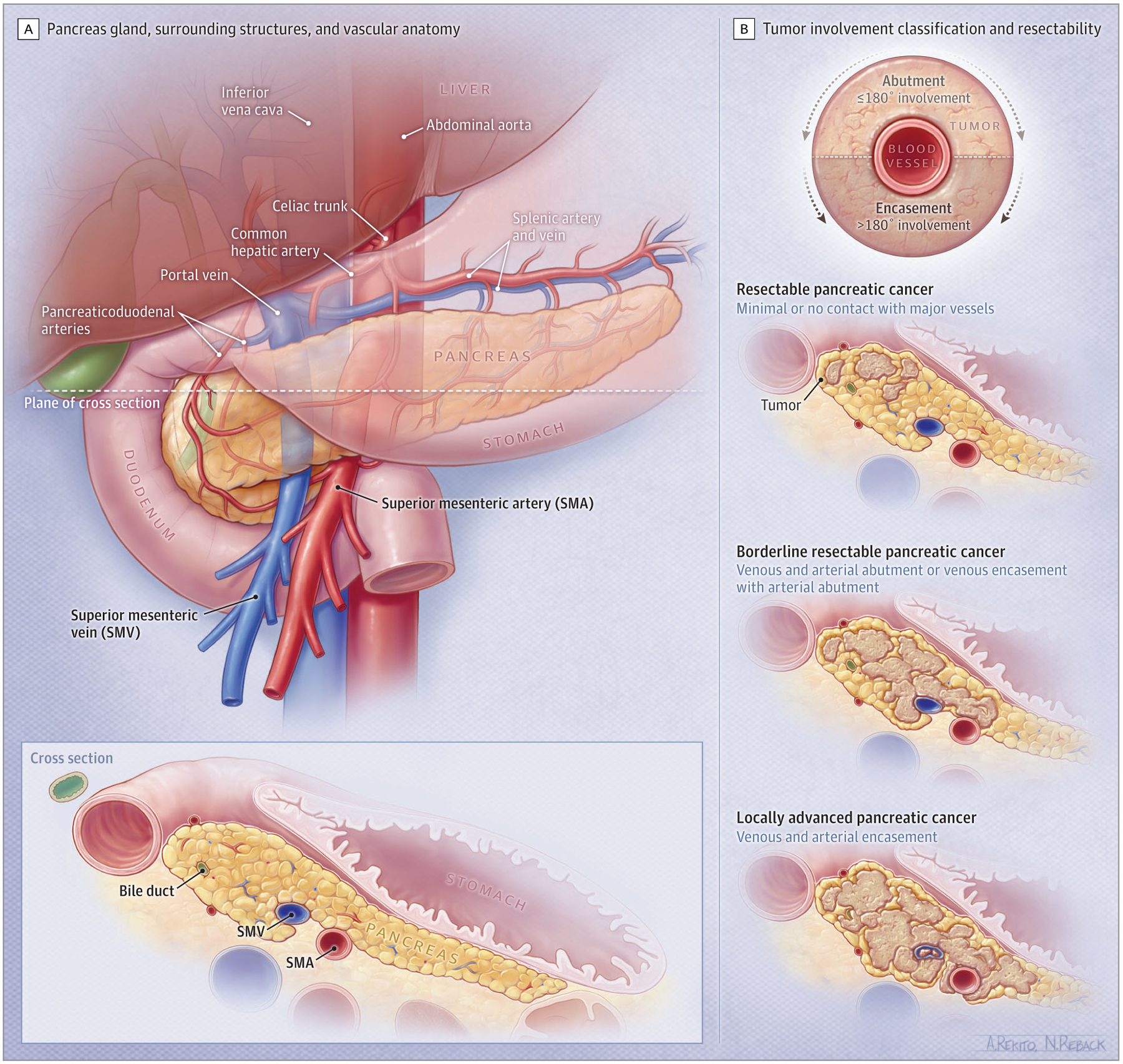

Pancreas computed tomography (CT) angiography with chest and pelvis CT can be used in the assessment of vascular anatomy and stage of disease and are recommended at diagnosis. The degree of contact between the tumor and local blood vessels (ie, the superior mesenteric and portal veins as well as the celiac, hepatic, and superior mesenteric arteries) is categorized as either uninvolved, abutted, or encased. Abutment implies that the tumor has 180° or less of blood vessel involvement and encasement implies greater than 180° of circumferential tumor-vessel involvement (Figure 1). This information is important to define the most optimal initial treatment. Common sites of PDAC metastases are liver (90%), lymph nodes (25%), lung (25%), peritoneum (20%), and bones (10%–15%).3 Magnetic resonance imaging and cholangiopancreatography can help determine whether indeterminate liver lesions are likely to represent metastases and identify cancers that may be poorly characterized on CT imaging. Positron emission tomography/CT using a fluorodeoxyglucose tracer is a functional imaging tool that evaluates glucose metabolism in the tumor and can help distinguish benign from malignant lesions in the pancreas; however, it lacks the spatial resolution and can detect glucose uptake from infection, inflammation also confounding interpretation.50 Positron emission tomography/CT is not considered a routine staging tool.

Figure 1.

Spectrum of Localized Pancreatic Cancer

Endoscopic ultrasonography is used to visualize a pancreas mass directly, secure a definitive cytologic or histologic diagnosis, define the degree of tumor-vascular involvement, evaluate regional lymph nodes, and evaluate the potential for complete resection. Fine-needle core biopsy (preferred over fine-needle aspiration) of a tumor guided by endoscopic ultrasonography is recommended to obtain a histologic diagnosis and to provide material for molecular testing (Table 1). Visualization of an obstructed biliary tree is performed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, with decompression most often achieved by placing a metallic biliary stent. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 is a well-established biomarker for PDAC and is useful for monitoring treatment response. Although carbohydrate antigen 19–9 is not sufficiently sensitive or specific for routine screening, its value as a screening tool is being revisited.51,52 Other investigational blood-based biomarkers, including cell-free DNA, exosomes, and circulating tumor cells, may also be useful for monitoring treatment response and evaluating therapy resistance.53

Table 1.

Overview of Treatment and Prognosis by Stage of Pancreatic Cancer

| Disease extent | Localized | Advanced | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major vasculature involvementa | Uninvolved or abutted | Uninvolved or abutted | Encased | Distant metastasis, irrespective of the major vascular involvement |

| Clinical stage | Resectable | Borderline resectable | Locally advanced | Metastatic |

| Prevalence of pancreatic cancer among patients newly diagnosed with PDAC, % | 10–15 | 30–35 | 30–35 | 50–55 |

| American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor, node, and metastasis stage | I-II | II-III | II-III | IV |

| Treatment intent | Curative | Curative | Supportive and palliative | Supportive and palliative |

| Treatment | Surgery plus adjuvant systemic therapy | Neoadjuvant systemic therapy; surgery for resectable patients from favorable response; radiation for unresectable patients without distant metastasis | Neoadjuvant systemic therapy; surgery for resectable patients from favorable response; radiation for unresectable patients without distant metastasis | Systemic therapya |

| 5-y survival rate, % | 35–45 | 10–15 | 10–15 | <5 |

Abbreviation: PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

The degree of contact between the tumor and local blood vessels (ie, the superior mesenteric and portal veins as well as the celiac, hepatic, and superior mesenteric arteries) is categorized as either uninvolved, abutted, or encased. Abutment implies that the tumor has 180° or less of blood vessel involvement and encasement implies greater than 180° of circumferential tumor-vessel involvement.

Clinical Staging and Multidisciplinary Management of Localized Disease

Resectability, defined as the ability to completely remove the cancer, is assessed to select treatment for localized PDAC (Table 1).54 The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, and metastasis classification is used to assess prognosis.55 For the practical treatment planning, each case is defined as resectable PDAC, borderline resectable PDAC (BRPC), or locally advanced PDAC (LAPC) based on the degree of tumor contact and invasion into the superior mesenteric, hepatic artery, or celiac vasculature (Figure 1). Localized disease consists of a spectrum of resectability, including resectable (operable), borderline resectable, and locally advanced and inoperable disease. Characterizing localized disease is best performed by multidisciplinary review, including physicians from surgical oncology, radiology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology disciplines. Several classifications of resectability are used.56 Tumors are typically considered resectable when there is minimal or no contact with major vessels. However, BRPC may have venous involvement and/or partial arterial involvement. There is growing interest in evaluating neoadjuvant systemic therapy with or without radiotherapy for BRPC and resectable PDAC. Locally advanced PDAC is unresectable at presentation due to vessel invasion.

The optimal procedure for resection of the primary tumor depends on tumor location and its relationship to the bile duct and vasculature. Generally, tumors in the pancreas head and uncinate process require a pancreaticoduodenectomy, or “Whipple procedure,” while tumors in the pancreatic neck (without bile duct involvement), body, and tail require a distal pancreatectomy. Vessel invasion may require vascular resection and reconstruction. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is associated with high rates of adverse events, including delayed gastric emptying (10%) and pancreatic leak (13%).57 The best outcomes are attained by surgeons who perform more than 20 pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures per year and conduct surgery in a high-volume center. Minimally invasive pancreatectomy has been demonstrated to be safe, with similar complication rates as open pancreatectomy (OR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.39–1.16]) as well as shorter hospital stay (weighted mean difference, 3.7 days) compared with open pancreatectomy.58,59 Pancreatectomy should be performed when a margin-negative resection is feasible. En bloc resection and reconstruction of the portal vein in patients with tumor invasion into this blood vessel is used to obtain a margin-negative resection. This undertaking results in a similar prognosis than in patients whose tumors do not invade the portal vein and is standard therapy for patients with BRPC.60

Current multidisciplinary management paradigms include early integration of supportive care, prehabilitation strategies with physical therapy, occupational therapy (prior to proceeding to the operating room), nutritional management (including pancreas enzyme supplementation), advance care planning, and increasing use of patient-reported outcome measures to enhance quality of life (eTable2 in the Supplement).61

Advances in Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Pancreatic Cancer

The recommended adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of PDAC is either modified FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, leucovorin) for individuals with high functional status or gemcitabine and capecitabine or gemcitabine alone for individuals with poorer functional status. Recommendations for adjuvant therapy are based on several important trials from the past 2 decades.5,62–64 The main chemotherapy agents are DNA-damaging agents, which directly affect DNA synthesis and repair (oxaliplatin, irinotecan), and antimetabolites, such as gemcitabine and fluorouracil (Table 2). The efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in resected PDAC was defined in the CONKO-001 trial, in which 368 patients who underwent surgical resection of PDAC were randomized to receive 6 months of adjuvant gemcitabine or undergo observation (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Superior median overall survival was observed in patients treated with gemcitabine compared with those who underwent observation (22.8 vs 20.2 months; hazardratio [HR], 0.76 [95% CI, 0.61–0.95]), representing a modest prolongation of survival.62 Subsequent trials compared gemcitabine with single-agent fluorouracil as well as 2- and 3-drug combination regimens.5,63,64 The ESPAC-4 phase 3 trial demonstrated an added survival benefit of dual-agent therapy over gemcitabine alone. In this trial, 730 patients were randomized to receive 6 months of adjuvant gemcitabine plus capecitabine, an oral antimetabolite, or gemcitabine alone. Combination therapy improved median overall survival compared with gemcitabine alone (28.0 vs 25.5 months; HR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.68–0.98]).64 Most recently, in the 2018 multicenter PRODIGE-24 trial, 493 patients with resected PDAC, along with a low serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (< 180 U/mL) and an excellent performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, 0–1), were randomized to receive 6 months of adjuvant modified FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine alone. In this trial, favorable survival occurred in both groups relative to prior trials with gemcitabine in the adjuvant setting and likely reflected inclusion of more highly selected patients: patients treated with modified FOLFIRINOX had an overall survival of 54.4 months, compared with 35 months in patients treated with gemcitabine (HR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.48–0.86]).5 Thus, modified FOLFIRINOX is recommended as standard adjuvant therapy in individuals with excellent functional status after surgical resection of PDAC. Overall, patients for whom treatment with modified FOLFIRINOX is not suitable can be considered for gemcitabine/capecitabine or gemcitabine alone.63,64 The role of radiotherapy as an adjuvant therapy for resected PDAC is controversial. Older studies did not support adjuvant radiation for PDAC because no overall survival advantage has been demonstrated.68,69

Table 2.

Summary of Selected Clinical Trials of Systemic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer

| Trial | Setting of therapy | Study regimen | Comparator regimen | Randomized patients, No. | Primary end point | Median survival, mo | Common serious adverse eventsa reported in study group (% of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONKO-00165 (2007) | Adjuvant | Gemcitabine | Observation | 368 | Disease-free survival | 13.4 vs 6.7 | Leukopenia (2), anemia (1), thrombocytopenia (1), nausea/vomiting (1), hepatic dysfunction (1), diarrhea (1) |

| ESPAC-466 (2017) | Adjuvant | Gemcitabine and capecitabine | Gemcitabine | 730 | Overall survival | 28.0 vs 25.5 | Neutropenia (38), leukopenia (10), hand-foot syndrome (7), fatigue (6), diarrhea (5) |

| PRODIGE-245 (2018) | Adjuvant | mFOLFIRINOX | Gemcitabine | 493 | Overall survival | 54.4 vs 35 | Neutropenia (28), diarrhea (19), paresthesia (13), fatigue (11), sensory peripheral neuropathy (9), nausea (6), hepatic dysfunction (<5) |

| PRODIGE3 (2011) | First-line for metastatic disease | FOLFIRINOX | Gemcitabine | 342 | Overall survival | 11.1 vs 6.8 | Neutropenia (46), fatigue (24), vomiting (15), diarrhea (13), thrombocytopenia (9), sensory neuropathy(9), hepatic dysfunction (7), thromboembolism (7), anemia (8) |

| MPACT4 (2013) | First-line for metastatic disease | Gemcitabine and albumin-bound paclitaxel | Gemcitabine | 861 | Overall survival | 8.5 vs 6.7 | Neutropenia (38), leukopenia (31), thrombocytopenia (13), anemia (13), fatigue (17), peripheral neuropathy (17), diarrhea (6) |

| NAPOLI-167 (2015) | For metastatic disease after progression on gemcitabine therapy | 5-FU/LV and nanoliposomal irinotecan | 5-FU/LV | 417 | Overall survival | 6.2 vs 4.2 | Neutropenia (27), fatigue (14), diarrhea (13), vomiting (11), anemia (9) |

| POLO8 (2019) | Maintenance following ≥4 mo of platinum-based therapy (germline BRCA1/2) | Olaparib | Placebo | 154 | Progression-free survival | 7.4 vs 3.8 | Anemia (11), fatigue (5), decreased appetite (3), abdominal pain (2), vomiting (1), arthralgia (1) |

Abbreviations: 5-FU/LV, fluorouracil, leucovorin; mFOLFIRINOX, modified FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin).

Grade 3 or higher.

Neoadjuvant and Perioperative Therapy for Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer

Neoadjuvant therapy, or preoperative therapy, can eradicate occult metastatic disease and increase the number of patients eligible for systemic therapy. The latter is important because a significant percentage of patients are unable to receive adjuvant therapy because of operative morbidity. Recent nonrandomized prospective trials demonstrated high completion rates, of 83% to 90%, in patients receiving neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX.7,70 In a phase 2 trial, 39 of 43 patients with BRPC received 4 months of FOLFIRINOX.7,70 Similarly, in the Southwest Oncology Group S1505 trial, 46 of 55 patients completed neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX therapy.7 Another advantage is potential downstaging prior to undergoing surgery, facilitating a margin-negative resection.70,71 This was demonstrated in a multi-institutional trial that reported improved margin-negative resection rates in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy compared with initial surgery in 58 patients with BRPC (82.4% vs 33.3%; P = .01).72

The role of radiotherapy in localized PDAC remains unclear and is being evaluated in ongoing investigations.73–76 Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy has demonstrated potential benefit in the phase 3 PREOPANC trial, in which 236 patients were randomized to receive neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemoradiation followed by surgery or initial surgery, both followed by adjuvant gemcitabine. An overall survival benefit was observed in the predefined subgroup of 113 patients with BRPC who were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (17.6 vs 13.2 months; HR, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.40–0.95]).74 The ALLIANCE A021501 trial, a randomized phase 2 trial, evaluated perioperative modified FOLFIRINOX with or without neoadjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy in 126 patients with BRPC. The addition of stereotactic body radiotherapy to neoadjuvant modified FOLFIRNOX did not improve median overall survival (31.0 months [95% CI, 22.2 to not reached] for the modified FOLFIRINOX group and 17.1 months [95% CI, 12.8– 24.4] for the modified FOLFIRINOX plus stereotactic body radiotherapy group). Data for both groups were compared with historical data and the study did not have sufficient statistical power to compare the groups directly.77 Current guidelines support neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy as an option in both BRPC and LAPC.54 Eligibility for surgical resection in BRPC and LAPC requires assessment by a multidisciplinary team.

The benefit of neoadjuvant therapy in resectable PDAC is undergoing evaluation. Potential limitations of neoadjuvant therapy include the lack of a major tumor response to neoadjuvant therapy in most patients.7Inadequate tumor response may facilitate tumor progression, obviating the opportunity to completely resect the tumor. However, the importance of this phenomenon remains unclear. Neoadjuvant therapy adds complexity to multidisciplinary treatment planning. It requires a pretreatment biopsy and endoscopic stent placement in patients with biliary obstruction. In patients with resectable disease, preoperative biliary drainage was associated with perioperative complications, such as pancreatitis in 7% of patients, cholangitis in 26%, stent occlusion in 15%, and postoperative wound infection in 13%.78 A randomized phase 2 Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) S1505 trial of 102 patients evaluated perioperative modified FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine and albumin-bound paclitaxel. Results showed no difference in overall survival between the modified FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus albumin-bound paclitaxel, with 2-year overall survival rates of 47% (95% CI, 31%–61%) and 48% (95% CI, 31%–63%).7 Uncertainties related to the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy in patients with resectable PDAC may be addressed by an ongoing phase 3 trial (A021806) comparing perioperative modified FOLFIRINOX with adjuvant modified FOLFIRINOX in patients with resectable PDAC.

Therapy of LAPC

LAPC is an inoperable disease at diagnosis, and approximately 80% of patients are unlikely to have sufficient tumor response from neoadjuvant therapy to become eligible for surgical resection. To achieve disease control, initial treatment typically consists of chemotherapy regimens, such as modified FOLFIRINOX or albumin-bound paclitaxel and gemcitabine.79 The role of radiation in LAPC is controversial. A pooled analysis of 11 trials involving 794 patients reported that chemoradiation was associated with improved survival, compared with radiotherapy alone (2 trials [168 patients]; HR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.51–0.94]), but chemoradiation followed by chemotherapy did not improve survival more than chemotherapy (2 trials [134 patients]; HR, 0.79 [95% CI, 0.32–1.95]).80 The SCALOP trial evaluated the use of capecitabine or gemcitabine combined with radiation. The capecitabine group had superior median overall survival compared with the gemcitabine group (15.2 vs 13.4 months; adjusted HR, 0.39 [95% CI, 0.18–0.81]; P = .012).81 The role of radiation, the optimum radiation modality, and the dosing schedule for radiation in LAPC all remain unclear. Innovative radiation strategies, including high-dose “ablative” radiotherapy, are under investigation.

Standard Therapies for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

Multiagent cytotoxic regimens have improved survival in advanced PDAC.3–5,67 Current standard first-line regimens for patients with metastatic disease include gemcitabine and albumin-bound paclitaxel or modified FOLFIRINOX (Table 2; eTable 3 in the Supplement).3,4 The Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Trial (MPACT) trial of 861 patients with untreated metastatic PDAC reported an overall survival benefit for gemcitabine and albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with gemcitabine (median survival, 8.5 vs 6.7 months; HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.62–0.83]; P < .001).4 The PRODIGE trial of 342 patients with untreated metastatic PDAC reported that mean survival was better with FOLFIRINOX treatment compared with gemcitabine (11.1 vs 6.8 months; HR, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.45–0.73]; P < .001).3 For 417 patients with metastatic PDAC and disease progression receiving gemcitabine therapy, the NAPOLI-1 trial demonstrated superiority of overall survival for the combination of nanoliposomal irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin, with a median 6.1 months, compared with fluorouracil and leucovorin, with a median of 4.2 months (HR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.49–0.92]; P = .012).67These trials were conducted in patients without selection for any specific disease or genetic characteristic. In contrast, the POLO (Pancreas Olaparib Ongoing) trial validated a genetic biomarker, germline BRCA1/2 variation, leading to US Food and Drug Administration approval of olaparib, apoly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. Olaparib or placebo was administered as a maintenance treatment in patients with a germline BRCA1/2 variation and metastatic PDAC following initial platinum-based chemotherapy and was approved based on a progression-free survival benefit compared with placebo (7.4 vs 3.8 months; HR, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.35–0.82]; P = .004).8 Of note, there was no difference in overall survival between the placebo and olaparib groups in the POLO trial (HR, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.56–1.22]; P = .35).

Symptom Management and Supportive Care Approaches in Pancreatic Cancer

Supportive care by a multidisciplinary team should be integrated with therapeutic management of PDAC to maximize length of life, quality of life, and symptom control. Specifically, attention to nutrition, pain management, management of thromboses, psychosocial needs, and advance care planning are among the most important considerations.61 Other challenges of PDAC include bile duct and duodenal obstruction. Biliary obstruction is managed with endobiliary metallic stent placement or surgical biliary-enteric bypass.82 Gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction is managed via endoscopic stent placement, which has been shown to have noninferior efficacy and greater durability relative to gastrojejunostomy.83

Novel Therapies for Pancreatic Cancer

A subgroup of 10% to 15% of individuals with PDAC have DNA damage repair gene alterations other than BRCA. Novel combination strategies evaluating targeted agents and immune therapy combinations are undergoing testing for patients with PDAC associated with impaired DNA damage repair.9,84 Single-agent PD-1 blockade has US Food and Drug Administration approval for mismatch repair deficiency in any tumor. Mismatch repair deficiency occurs in approximately 1% of individuals with PDAC and is defined by either germline or somatic alterations or loss in mismatch repair deficiency genes, such as MLH1 and MSH2.29,85 KRAS missense variants in codon G12C in PDAC occur in 1% to 2% of patients with PDAC, and early-phase assessment of the KRAS G12Callele-specific inhibitor sotorasib demonstrated 1 instance of partial response (>30% tumor reduction) and stable disease in a cohort of 12 patients with PDAC who have this variation. The KRAS wild-type subset of PDAC (absence of KRAS variation) is observed in 6% to 8% of all patients with PDAC and in up to 16% to 18% in patients younger than 50 years at diagnosis.86 In this setting, alternative oncogenic drivers are present and entrectinib and larotrectinib have activity in TRK fusion (<1%) and zenocutuzumab (MCLA-128) has activity in NRG-1 fusion (<1%) PDAC.87,88

There are multiple drugs targeting the epithelial component, signaling pathways, metabolism, and the TME of PDAC (Figure 2). Single or combination immune checkpoint blockade inhibitors, such as durvalumab and tremelimumab, are ineffective for PDAC.44,45,89 However, an early efficacy signal of an objective response rate of 67% (8 of 12 participants in all cohorts and median overall survival of 20.1 months [95% CI, 10.5 to not estimable] among 24 dose-limiting toxicity-evaluable participants) has been observed for the combination of the CD40 agonistic antibody sotigalimab with the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab and chemotherapy.90 Adenosine is an immunosuppressive metabolite in the TME. Depleting adenosine, using both small molecule–targeting agents (eg, AB680) or with antibody therapy (eg, oleclumab), represent novel metabolism-directed approaches being investigated in PDAC.91 eTable 1 in the Supplement summarizes select ongoing trials in PDAC.

Figure 2.

Novel Targets and Agents in Development in Pancreatic Cancer

ADB indicates adenosine diphosphate; CA, carbohydrate antigen;

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CSF, colony-stimulating factor; DDR, DNA damage repair, EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; and TH1, type 1 helper T cell.

a Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration or guideline-endorsed for pancreatic cancer.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, it is not a systematic review and the quality of included literature was not formally evaluated. Second, some relevant studies may have been missed. Third, it does not cover all aspects of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of pancreatic cancer.

Conclusions

Approximately 60 000 new cases of PDAC are diagnosed per year, and about 50% of patients have advanced disease at diagnosis. The incidence of PDAC is increasing. Currently available cytotoxic therapies for advanced disease are modestly effective. For all patients, multidisciplinary management, comprehensive germline testing, and integrated supportive care is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Box. Overview of Pancreatic Cancer.

| General Facts |

| Approximately 60 000 diagnoses per year in the US |

| Incidence of about 1% over lifetime |

| The tenth to eleventh leading cause of cancer in the US |

| Third leading cause of cancer-related mortality |

| 5-year survival (all-comers), 10% |

| Median age at diagnosis, 71 years |

| Male/female incidence ratio: 1.3/1.0 |

| 50% of patients present with metastatic disease (AJCC stage IV) |

| 30% of patients present with locally advanced disease (AJCC stage III) |

| 20% of patients present with localized resectable disease (AJCC stage I and II) |

| Most common causative germline alterations: BRCA2, BRCA1, ATM, PALB2 |

| Common sites of metastasis: liver, lymph node, lung, and peritoneum |

| Rare sites of metastasis: skin, brain, and leptomeninges |

| Lifestyle Risk Factors |

| Tobacco |

| Excess alcohol consumption (chronic pancreatitis) |

| Obesity (body mass index >30), metabolic disorders, low levels of physical activity |

| Diet: high fat, polyunsaturated fats, processed meats |

| Genetic Risk Factors a |

| Hereditary breast and ovary cancer syndrome (BRCA1/2, PALB2; 5%–9%) |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM; approximately 3%–4%) |

| Familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma syndrome (CDKN2A, p16; <1%) |

| Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM; <1%) |

| Hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1, SPINK1; <1%) |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11; <1%) |

Abbreviation: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Percentages indicate the frequency per 100 unselected patients diagnosed with pancreas cancer.

Funding/Support:

Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748; David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreas Cancer Research; Paul Calabresi Career Development Award K12 CA184746; Parker Institute for Immunotherapy Pilot Grant; Elsa U. Pardee Foundation Grant.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Park reported receiving grant and research support from Astellas, Gossamer Bio, and Merck and providing consultancy to Ipsen. Dr O’Reilly reported receiving grants and research funding to the institution from Genentech-Roche, Celgene-BMS, BioNTech, Arcus, AstraZeneca, and BioAtla; personal fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board from Cytomx Therapeutics, Rafael Therapeutics, personal fees from Sobi Consulting, non-financial support from Silenseed Consulting, personal fees from Molecular Templates Consulting, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim Consulting, personal fees from BioNTech Consulting, personal fees from Ipsen Consulting, personal fees from Polaris Consulting, and personal fees from Merck Consulting during the conduct of the study; other from Bayer Spouse consulting, other from Celgene/BMS Spouse consulting, other from Genentech-Roche Spouse consulting, and other from Eisai Spouse consulting outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Wungki Park, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, New York, New York; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York; Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, San Francisco, California.

Akhil Chawla, Department of Surgery, Northwestern Medicine Regional Medical Group, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois; Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Eileen M. O’Reilly, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, New York, New York; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. ; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. ; Canadian Cancer Trials Group and the Unicancer-GI–PRODIGE Group. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379(25):2395–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2020. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohal DPS, Duong M, Ahmad SA, et al. Efficacy of perioperative chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):421–427. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Reilly EM, Lee JW, Zalupski M, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase ii trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without veliparib in patients with pancreas adenocarcinoma and a germline BRCA/PALB2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38(13):1378–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong MCS, Jiang JY, Liang M, Fang Y, Yeung MS, Sung JJY. Global temporal patterns of pancreatic cancer and association with socioeconomic development. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3165. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02997-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawla P, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J Oncol. 2019;10(1):10–27. doi: 10.14740/wjon1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terhune PG, Phifer DM, Tosteson TD, Longnecker DS. K-ras mutation in focal proliferative lesions of human pancreas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7(6):515–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konstantinidis IT, Vinuela EF, Tang LH, et al. Incidentally discovered pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: what is its clinical significance? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3643–3647. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3042-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oyama H, Tada M, Takagi K, et al. Long-term risk of malignancy in branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):226–237.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. ; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6(1–2):17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackert T, Fritz S, Klauss M, et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: high cancer risk in duct diameter of 5 to 9mm. Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):875–880. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):819–822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for pancreatic cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322(5):438–444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosetti C, Lucenteforte E, Silverman DT, et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: an analysis from the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (Panc4). Ann Oncol. 2012; 23(7):1880–1888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iodice S, Gandini S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393(4):535–545. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0266-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YT, Gou YW, Jin WW, Xiao M, Fang HY. Association between alcohol intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:212. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, et al. Alcohol intake and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis of fourteen cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(3):765–776. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen D, Stocks T, Jonsson H, et al. Metabolic factors and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a prospective analysis of almost 580,000 men and women in the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(9):2307–2317. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(3):e137–e147. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30267-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shindo K, Yu J, Suenaga M, et al. Deleterious germline mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3382–3390. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu C, Hart SN, Polley EC, et al. Association between inherited germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2401–2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golan T, Kindler HL, Park JO, et al. Geographic and ethnic heterogeneity of germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation prevalence among patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer screened for entry into the POLO trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1442–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu C, LaDuca H, Shimelis H, et al. Multigene hereditary cancer panels reveal high-risk pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2. doi: 10.1200/po.17.00291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu ZI, Hellmann MD, Wolchok JD, et al. Acquired resistance to immunotherapy in MMR-D pancreatic cancer. Journal Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0448-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rainone M, Singh I, Salo-Mullen EE, Stadler ZK, O’Reilly EM. An emerging paradigm for germline testing in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and immediate implications for clinical practice: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):764–771. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2012; 142(4):730–733.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518(7540):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguirre AJ, Nowak JA, Camarda ND, et al. Real-time genomic characterization of advanced pancreatic cancer to enable precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1096–1111. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531(7592):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1168–1178. doi: 10.1038/ng.3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi A, Fan J, Chen R, et al. A unifying paradigm for transcriptional heterogeneity and squamous features in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nature Cancer. 2020;1(1):59–74. doi: 10.1038/s43018-019-0010-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1344–1354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knox JJClinical advances in pancreas adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2020;80(22 suppl). AACR Virtual Special Conference on Pancreatic Cancer abstract IA-08. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowery MA, Jordan EJ, Basturk O, et al. Real-time genomic profiling of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: potential actionability and correlation with clinical phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(20):6094–6100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the Know Your Tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):508–518. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30074-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balachandran VP, Łuksza M, Zhao JN, et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; Garvan Institute of Medical Research; Prince of Wales Hospital; Royal North Shore Hospital; University of Glasgow; St Vincent’s Hospital; QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute; University of Melbourne, Centre for Cancer Research; University of Queensland, Institute for Molecular Bioscience; Bankstown Hospital; Liverpool Hospital; Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse; Westmead Hospital; Fremantle Hospital; St John of God Healthcare; Royal Adelaide Hospital; Flinders Medical Centre; Envoi Pathology; Princess Alexandria Hospital; Austin Hospital; Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes; ARC-Net Centre for Applied Research on Cancer. Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;551(7681):512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature24462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beatty GL, Eghbali S, Kim R. Deploying immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer: defining mechanisms of response and resistance. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:267–278. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_175232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying cancers based on T-cell infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2015;75(11):2139–2145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, et al. T-cell-inflamed gene-expression profile, programmed death ligand 1 expression, and tumor mutational burden predict efficacy in patients treated with pembrolizumab across 20 cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):318–327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33(8):828–833. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho WJ, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer: clinical challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(9):527–540. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0363-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevala-Plagemann C, Hidalgo M, Garrido-Laguna I. From state-of-the-art treatments to novel therapies for advanced-stage pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(2):108–123. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0281-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter FM, Mills K, Mendonça SC, et al. Symptoms and patient factors associated with diagnostic intervals for pancreatic cancer (SYMPTOM pancreatic study): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(4):298–306. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aslanian HR, Lee JH, Canto MI. AGA Clinical Practice Update on pancreas cancer screening in high-risk individuals: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):358–362. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang XY, Yang F, Jin C, Fu DL. Utility of PET/CT in diagnosis, staging, assessment of resectability and metabolic response of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(42):15580–15589. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzeng CW, Balachandran A, Ahmad M, et al. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 represents a marker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16(5):430–438. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fahrmann JF, Schmidt CM, Mao X, et al. Lead-time trajectory of CA19–9 as an anchor marker for pancreatic cancer early detection. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1373–1383. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J-S, Park SS, Lee YK, Norton JA, Jeffrey SS. Liquid biopsy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: current status of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(8):1623–1650. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vauthey JN, Dixon E. AHPBA/SSO/SSAT Consensus Conference on Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: rationale and overview of the conference. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(7):1725–1726. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0409-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen PJ, Kuk D, Castillo CF, et al. Multi-institutional validation study of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (8th Edition) changes for T and N staging in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):185–191. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gilbert JW, Wolpin B, Clancy T, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: conceptual evolution and current approach to image-based classification. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2067–2076. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt CM, Turrini O, Parikh P, et al. Effect of hospital volume, surgeon experience, and surgeon volume on patient outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145(7):634–640. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Correa-Gallego C, Dinkelspiel HE, Sulimanoff I, et al. Minimally-invasive vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(1):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Steen MW, et al. ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative cohort and registry studies. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):257–267. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramacciato G, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, et al. Pancreatectomy with mesenteric and portal vein resection for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: multicenter study of 406 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(6):2028–2037. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5123-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moffat GT, Epstein AS, O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic cancer: a disease in need: optimizing and integrating supportive care. Cancer. 2019;125(22): 3927–3935. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1473–1481. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(10):1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32409-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297(3):267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, et al. ; NAPOLI-1 Study Group. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):545–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230(6):776–782. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(12):1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murphy JE, Wo JY, Ryan DP, et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy with folfirinox followed by individualized chemoradiotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(7):963–969. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chawla A, Molina G, Pak LM, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy is associated with improved survival in borderline-resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(4):1191–1200. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08087-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jang JY, Han Y, Lee H, et al. Oncological benefits of neoadjuvant chemoradiation with gemcitabine versus upfront surgery in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 2/3 trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katz MHG, Ou FS, Herman JM, et al. ; Alliance for Clinical Trials on Oncology. Alliance for clinical trials in oncology (ALLIANCE) trial A021501: preoperative extended chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy plus hypofractionated radiation therapy for borderline resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):505. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3441-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, et al. ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1763–1773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loehrer PJ Sr, Feng Y, Cardenes H, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31): 4105–4112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Treatment of locally unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas: comparison of combined-modality therapy (chemotherapy plus radiotherapy) to chemotherapy alone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80 (10):751–755. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.10.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katz MHG, Shi Q, Meyers JP, et al. Alliance A021501: preoperative mFOLFIRINOX or mFOLFIRINOX plus hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) for borderline resectable (BR) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 2021; 39(3_suppl):377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):129–137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pancreatic Cancer, Version 1.2021. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sultana A, Tudur Smith C, Cunningham D, et al. Systematic review, including meta-analyses, on the management of locally advanced pancreatic cancer using radiation/combined modality therapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(8):1183–1190. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mukherjee S, Hurt CN, Bridgewater J, et al. Gemcitabine-based or capecitabine-based chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (SCALOP): a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):317–326. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70021-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Glazer ES, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS. A meta-analysis of randomized trials: immediate stent placement vs. surgical bypass in the palliative management of malignant biliary obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uemura S, Iwashita T, Iwata K, et al. Endoscopic duodenal stent versus surgical gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2018; 18(5):601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park W, Chen J, Chou JF, et al. Genomic methods identify homologous recombination deficiency in pancreas adenocarcinoma and optimize treatment selection. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(13):3239–3247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Florou V, Nevala-Plagemann C, Barber KE, Mastroianni JN, Cavalieri CC, Garrido-Laguna I. Treatment rechallenge with checkpoint inhibition in patients with mismatch repair-deficient pancreatic cancer after planned treatment interruption. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4(4):780–784. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Varghese AM, Singh I, Singh R, et al. Early-onset pancreas cancer: clinical descriptors, genomics, and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021; djab038. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heining C, Horak P, Uhrig S, et al. NRG1 Fusions in KRAS Wild-Type Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1087–1095. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Reilly EM, Oh DY, Dhani N, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab for patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):1431–1438. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.O’Hara MH, O’Reilly EM, Varadhachary G, et al. CD40 agonistic monoclonal antibody APX005M (sotigalimab) and chemotherapy, with or without nivolumab, for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22 (1):118–131. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30532-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bendell JC, Manji GA, Pant S, et al. A phase I study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of AB680 combination therapy in participants with gastrointestinal malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38 (4_suppl):TPS788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.4_suppl.TPS788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.