Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The differences in long-term outcomes of aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis between stentless and stented bioprostheses are controversial.

METHODS:

Between 2007–2018, 1173 patients underwent aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, including 559 treated with a stentless valve and 614 with a stented valve. A propensity score matched cohort with 348 pairs was generated by matching for age, sex, body surface area, bicuspid aortic valve, chronic lung disease, previous cardiac surgery, coronary artery disease, renal failure on dialysis, valve size, concomitant procedures, and surgeon. The primary endpoints of the study were long-term survival and incidence of reoperation.

RESULTS:

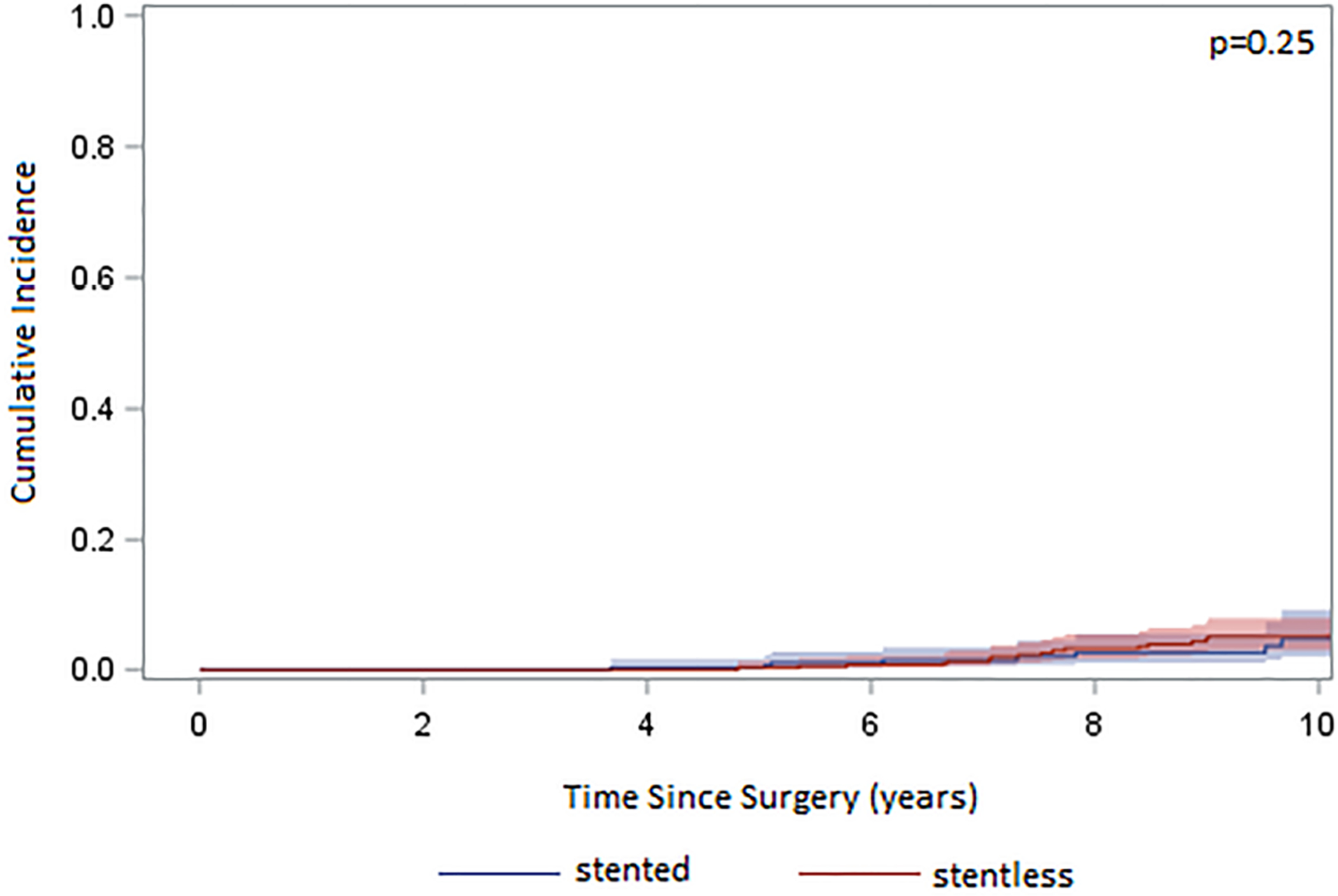

Immediate postoperative outcomes were similar between the stentless and stented groups with an overall operative mortality of 2.9% (p=0.19). Kaplan-Meier estimation for long-term survival was comparable between the stentless and stented valves in both the whole cohort and the propensity score matched cohort (10-year survival: 59% vs. 55%, p=0.20). The hazard ratio of stentless versus stented valve for risk of long-term mortality was 1.12 (p=0.33). The 10-year cumulative incidence of reoperation due to valve degeneration was 5.5% in the stentless group and 4.7% in the stented group (p=0.25). The transvalvular pressure gradient at 5-year follow-up was significantly lower in the stentless group (7 vs 11 mmHg, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Both stented and stentless valves could be used in aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. We recommend stented valves for aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis for their simplicity of implantation.

Classifications: Adult; Aortic root replacement; Aortic valve, replacement; Cardiac

The hemodynamic advantages of stentless bioprosthetic aortic valves compared to stented bioprostheses have been explored and discussed1–5. However, research aiming to demonstrate how those advantages translate into better short- and long-term outcomes is not as robust. The studies that have compared the long-term survival between the stentless and stented valves have drawn varying conclusions6–10.

In our study, we aim to compare the short- and long-term outcomes of aortic valve replacement with either a stentless (Freestyle, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) or stented (Magna Ease 3300TFX, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) bioprosthetic aortic valve. We hypothesize that there is no significant difference in long-term survival or long-term freedom from reoperation between patients treated with stentless versus stented valves.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan. A waiver of consent was obtained.

SUBJECTS

Between January 2007 and December 2018, 1173 patients with aortic stenosis as the primary surgical indication underwent aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthetic aortic valve at a single medical center. Patients were divided into groups based on whether a stentless (n=559) or stented (n=614) bioprosthesis was utilized.

Society of Thoracic Surgeons data was obtained from the University of Michigan Cardiac Surgery Data Warehouse to identify the cohort and to determine pre-operative, operative, and post-operative characteristics. Medical record review was utilized to supplement data collection, which included collection of echocardiographic datapoints for both preoperative echocardiograms and 5-year postoperative echocardiograms when available. The National Death Index database through June 30th, 202011 was used for long-term survival and supplemented with medical record review to ensure accuracy.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

All patients underwent primary replacement of the aortic valve with a Freestyle stentless bioprosthesis or Magna Ease stented valve. Operative implantation of the Freestyle valve was all completed by modified inclusion12. The stented valve was implanted via supra-annular implantation. The selection of stented vs. stentless valve was surgeons’ preference. Some surgeons used stentless valves for all patients with aortic stenosis because they believed the stentless valves had a better hemodynamic profile than stented valves of the same size. Other surgeons preferred to use stented valves for the simplicity of implantation. Surgeons used the maximum sized bioprotheses that the patients could take. Aortic root enlargement was performed when needed, including Nicks or Manougian procedure and non-coronary sinus enlargement for upsizing both stented and stentless valves.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables were summarized by median (interquartile range, 25,75 percentile) and categorical variables were reported as n (%) in frequency tables. Univariable comparisons across different treatment groups were performed using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, chi-square for categorical data (expected cell count ≥5), and Fisher’s exact test was implemented for categorical variables (expected cell count <5). Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) for independent risk factors by adjusting for valve types, valve sizes, body surface area (BSA), age, sex, bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), chronic lung disease, coronary artery disease (CAD), previous cardiac surgery, renal failure, concomitant procedures, and surgeons. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate the adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for independent risk factors by adjusting for same variables as the logistic model, based on the common risk factors associated with long-term mortality, with the exception of BSA, which was stratified as ≤1.8m2 and >1.8m2 based on the average BSA being 1.8m2 in normal weight individuals13. Propensity score matching of patients treated with stentless and stented valve was conducted by matching age, sex, BSA, BAV, chronic lung disease, previous cardiac surgery, CAD, renal failure on dialysis, concomitant procedures, valve size, and surgeon. Long-term survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier model, and the log-rank test was used to assess differences in survival between the groups. Cumulative incidences of reoperation were compared using Gray’s test. All statistical calculations used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The significance level was set at a standard 0.05.

RESULTS

PREOPERATIVE AND DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

The demographic characteristics and preoperative risk factors were overall similar between the groups (Table 1). However, the stentless group was mildly younger (65 years vs 67 years), had smaller BSA (2.0m2 vs 2.1m2), more prior cerebrovascular accidents (7.0% vs 3.6%), and more incidence of bicuspid aortic valve (55% vs 48%), but less dyslipidemia (60% vs 71%).

Table 1:

Demographics and Pre-Operative Data

| Total (N=1173) |

Stented (N=614) |

Stentless (N=559) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66 (58, 74) | 67 (58, 75) | 65 (57, 73) | 0.02 |

| Sex (Male) | 784 (67) | 404 (66) | 380 (68) | 0.43 |

| BSA | 2.0 (1.9, 2.2) | 2.1 (1.9, 2.2) | 2.0 (1.9, 2.2) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 887 (76) | 468 (76) | 419 (75) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes | 329 (28) | 181 (29) | 148 (26) | 0.25 |

| Dyslipidemia | 773 (66) | 435 (71) | 338 (60) | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 235 (20) | 128 (21) | 107 (19) | 0.47 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 236 (20) | 116 (19) | 120 (21) | 0.27 |

| Renal failure on Dialysis | 16 (1.3) | 7 (1.1) | 9 (1.6) | 0.49 |

| Last Creatinine Levels | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.92 |

| CAD | 454 (39) | 236 (38) | 218 (39) | 0.84 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 171 (15) | 101 (16) | 70 (13) | 0.06 |

| Prior Stroke | 61 (5.2) | 22 (3.6) | 39 (7.0) | 0.01 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 60 (55, 65) | 60 (55, 65) | 60 (55, 65) | 0.15 |

| BAV | 602 (51) | 296 (48) | 306 (55) | 0.03 |

| Previous Valve Procedure* | 125 (11) | 62 (10) | 63 (11) | 0.52 |

| Previous CABG | 91 (7.8) | 43 (7.0) | 48 (8.6) | 0.31 |

Data above is presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease

Previous Valve Procedure is defined as any history of replacement or repair of the aortic, mitral, tricuspid, or pulmonic valves

INTRAOPERATIVE DATA

The median prosthetic valve size was significantly larger in the stentless group with the median valve size in the stentless group being 27, while the median valve size in the stented group was 25 (Table 2). The stentless group had more concomitant procedures done overall (59% vs 52%). The stentless group had significantly less concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (15% vs 26%), but significantly more concomitant ascending aorta/arch procedures (42% vs 20%). In the stentless group, cardiopulmonary bypass time (182 minutes vs 146 minutes) and cross-clamp time (146 minutes vs 112 minutes) were significantly longer than in the stented group, and more patients required blood products (61% vs 42%). After propensity score match, there was no significant difference between the stentless and stented group in preoperative demographics, concomitant surgery, valve size and surgeons.

Table 2:

Operative Data

| Total (N=1173) |

Stented (N=614) |

Stentless (N=559) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | 0.88 | |||

| Elective | 1030 (88) | 540 (88) | 490 (88) | |

| Urgent | 143 (12) | 74 (12) | 69 (12) | |

| Prosthetic Valve Size | 25 (23, 27) | 25 (23, 27) | 27 (25, 29) | <0.001 |

| Valve Size/BSA | 12.5 (11.5,13.5) | 12.1 (11.2,13.1) | 12.8 (11.7, 13.8) | <0.001 |

| CPB Time | 168 (131, 211) | 146 (113, 189) | 182 (131, 225) | <0.001 |

| Cross Clamp Time | 134 (104, 170) | 112 (87,151) | 146 (118,181) | <0.001 |

| Isolated AVR | 522 (45) | 293 (48) | 229 (41) | 0.02 |

| Root Enlargement | 135 (12) | 54 (8.8) | 81 (15) | 0.002 |

| Concomitant CABG | 241 (21) | 160 (26) | 81 (15) | <0.001 |

| Concomitant Ascd. | 344 (29) | 121 (20) | 233 (42) | <0.001 |

| Aorta/Arch | ||||

| Concomitant Mitral Valve | 130 (11) | 76 (12) | 54 (10) | 0.14 |

| Concomitant Tricuspid Valve | 52 (4.4) | 23 (3.7) | 29 (5.2) | 0.23 |

| Blood Products Used | 600 (51) | 258 (42) | 342 (61) | <0.001 |

| Red Blood Cell | 518 (44) | 217 (35) | 301 (54) | <0.001 |

| Platelets | 365 (31) | 141 (23) | 224 (40) | <0.001 |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma | 300 (26) | 111 (18) | 189 (34) | <0.001 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 79 (6.7) | 23 (3.7) | 56 (10) | <0.001 |

Data above is presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting

POSTOPERATIVE DATA

There were no significant differences among most immediate postoperative outcomes including stroke, new-onset renal failure requiring dialysis, and operative mortality, but the stentless group spent more time in the intensive care unit (67 hours vs 53 hours) (Table 3). Overall operative mortality was 2.9%; 3.5% in the stentless group and 2.3% in the stented group (p=0.19). Logistic model for risk factors of operative mortality indicated that receiving a stentless valve was not a significant risk factor for operative mortality compared to receiving a stented valve (OR=1.91, 95% CI: 0.91, 4.03). Small prosthetic valve size (size 19–21 vs. size 29, OR=11.4, 95% CI: 1.2, 111) and prior cardiac surgery (OR=3.1, 95% CI: 1.5, 6.6) were significant risk factors for operative mortality (Table 4).

Table 3:

Post-Operative Data

| Total (N=1173) |

Stented (N=614) |

Stentless (N=559) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation | 400 (34) | 219 (36) | 181 (32) | 0.24 |

| Pacemaker | 17 (1.5) | 10 (1.6) | 7 (1.3) | 0.59 |

| Stroke | 16 (1.4) | 9 (1.5) | 7 (1.3) | 0.75 |

| ICU Stay (hours) | 61 (38, 98) | 53 (30, 96) | 67 (42, 99) | <0.001 |

| Ventilator Time | 7.7 (4.5, 15.6) | 6.9 (4.1, 13.9) | 8.1 (4.7, 16.8) | 0.08 |

| Prolonged Ventilator Hours | 139 (12) | 65 (11) | 74 (13) | 0.16 |

| Reoperation Due to Bleeding | 17 (1.5) | 7 (1.1) | 10 (1.8) | 0.35 |

| Renal Failure on Dialysis | 28 (2.4) | 11 (1.8) | 17 (3.0) | 0.16 |

| Intraoperative Mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| In-hospital mortality | 31 (2.5) | 13 (2.1) | 18 (3.2) | 0.24 |

| 30-day mortality | 31 (2.5) | 15 (2.3) | 16 (2.7) | 0.65 |

| Operative Mortality* | 36 (2.9) | 15 (2.3) | 21 (3.5) | 0.19 |

Data above is presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit.

Operative mortality includes all deaths occurring either during the hospitalization at any time or after discharge from the hospital, but within 30 postoperative days.

Table 4:

Logistic model for the risk factor of operative mortality

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Stentless Valve | 1.91 (0.91, 4.03) | 0.09 |

| Valve Size (19–21 vs 29) | 11.42 (1.18, 111.03) | 0.04 |

| Valve Size (23–27 vs 29) | 3.79 (0.48, 30.14) | 0.21 |

| BSA | 0.97 (0.20, 4.74) | 0.97 |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.17 |

| Sex (male) | 0.53 (0.22, 1.29) | 0.16 |

| BAV | 0.72 (0.32, 1.62) | 0.43 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 1.97 (0.95, 4.10) | 0.07 |

| Prior Cardiac Surgery | 3.13 (1.48, 6.62) | 0.002 |

| CAD | 0.92 (0.45, 1.87) | 0.82 |

| Renal Failure on Dialysis | 1.35 (0.16, 11.68) | 0.79 |

| Concomitant Procedure | 1.55 (0.76, 3.16) | 0.23 |

| Other Surgeons vs Surgeon 1 | 0.94 (0.39, 2.25) | 0.89 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CAD, coronary artery disease

LONG-TERM SURVIVAL

The completeness of follow-up was 100% for survival with combined data from the National Death Index and manual chart review, and the median follow-up period was 6.6 years for the whole cohort (7.9 years for the stentless and 5.5 years for the stented valve group). The stentless and stented groups had comparable 10-year survival, 59% (95% CI: 54%, 64%) vs. 54% (95% CI: 48%, 61%) (Figure 1A). This remained true in the propensity score matched cohort of stentless and stented groups (Figure 1B).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival of stentless vs. stented valve in the entire cohort (A) and propensity score matched patients using the variables: age, body surface area, valve size, sex, bicuspid aortic valve, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, previous cardiac surgery, coronary artery disease, renal failure on dialysis, concomitant procedures, and surgeon (B). 5-year survival was 82% in the stented valve group and 84% in the stentless valve group of the whole cohort.

Multivariable Cox model analysis indicated the stentless valve was not a significant protective factor for long-term mortality compared to the stented valve (HR=1.12, 95% CI: 0.89, 1.42) (Table 5). However, compared to the size 29 valve, both size 19–21 valves (HR=2.49, 95% CI: 1.38, 4.50) and size 23–27 valves (HR=2.05, 95% CI: 1.28, 3.29) were significant risk factors for long-term mortality. Other significant preoperative risk factors for long-term mortality included age (HR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.06), prior cardiac surgery (HR=1.55, 95% CI: 1.18, 2.02), chronic lung disease (HR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.27, 2.02), and renal failure on dialysis (HR=2.80, 95% CI: 1.53, 5.15); BAV was a protective factor (HR=0.66, 95% CI: 0.52, 0.84).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard regression for long-term mortality (stratified by BSA categories [≤1.8, >1.8])

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Stentless | 1.12 (0.89, 1.42) | 0.33 |

| Valve Size (≤21 vs 29) | 2.49 (1.38, 4.50) | 0.002 |

| Valve Size (23–27 vs 29) | 2.05 (1.28, 3.29) | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.16) | 0.39 |

| BAV | 0.66 (0.52, 0.84) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 1.60 (1.27, 2.02) | <0.001 |

| Prior Cardiac Surgery | 1.55 (1.18, 2.02) | 0.002 |

| CAD | 1.04 (0.85, 1.23) | 0.70 |

| Renal Failure on Dialysis | 2.80 (1.53, 5.15) | <0.001 |

| Concomitant Procedure | 1.12 (0.91, 1.38) | 0.30 |

| Other Surgeons vs Surgeon 1 | 1.35 (1.04, 1.74) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CAD, coronary artery disease.

LONG-TERM REOPERATION

Cumulative incidence of reoperation due to valve degeneration was comparable between the stentless and stented valves with a 10-year reoperation rate of 5.5% in the stentless group and 4.7% in the stented group (p=0.25) (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Cumulative incidence (CI) of reoperation after implantation of either a stented or stentless aortic valve adjusting for death and reoperation for non-valve related reasons showed no difference between stented and stentless valves (p=0.25).

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC DATA

Preoperative echocardiographic data showed no difference between stentless and stented groups in transvalvular pressure gradient (37 mm Hg vs 38 mm Hg) (Table 6). At 5 years post-operatively, the stentless group had a significantly lower ejection fraction than the stented group (60% vs 65%, p=0.008), and a significantly lower transvalvular pressure gradient (7 mm Hg vs 11 mm Hg, p<0.001).

Table 6:

Echocardiographic Data

| Total | Stented | Stentless | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | N=885 | N=447 | N=438 | |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 65 (60, 65) | 65 (57, 68) | 63 (60, 65) | 0.30 |

| Aortic Valve Gradient | 38 (28, 49) | 38 (29, 48) | 37 (27, 50) | 0.99 |

| Moderate or worse AI | 197 (22) | 87 (19) | 110 (25) | 0.044 |

| 5-year Postoperative | N=315 | N=128 | N=187 | |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 63 (60, 65) | 65 (60, 65) | 60 (60, 65) | 0.008 |

| Aortic Valve Gradient | 8 (6, 12) | 11 (7, 15) | 7 (5, 10) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or worse AI | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | >0.99 |

Data above is presented as median (25%, 75%) for continuous data.

Abbreviations: AI, aortic insufficiency.

COMMENT

In this study, we found perioperative outcomes of aortic valve replacement were comparable between the stentless and stented valves in patients with aortic stenosis. Despite the stentless group having better hemodynamics (Table 6), there was no difference in long-term survival in both unmatched and propensity score matched cohorts (Figure 1). There was also no difference in long-term incidence of reoperation between the stentless and stented valves (Figure 2).

There has been a long debate on whether to use a stentless or stented valve for patients with aortic stenosis needing an aortic valve replacement. Some surgeons prefer stentless valves because they believe the stentless valves have better hemodynamic performance compared to stented valves1,2 while others believe the difference is insignificant, especially compared to the newer generation of stented valves, such as Magna Ease. On top of this, stentless valves are more difficult to implant. In our study, we did not see a difference in long-term survival between stented and stentless valves in our Kaplan-Meier survival models across both the entire cohort and a propensity matched cohort (Figure 1) or in the multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis (Table 5). There was also no significant difference in cumulative incidence of reoperation due to valve degeneration (Figure 2). The most common technique we used was modified inclusion aortic root replacement, which has two suture lines and is more time consuming than stented valve aortic valve replacement, as shown by the longer cardiopulmonary bypass and cross-clamp times and more blood transfusions in the stentless valve group (Table 2). Although the stentless valve did show a better transvalvular pressure gradient compared to the stented valve (Table 6), consistent with the literature1–6, we can reasonably infer based on our study that the hemodynamic advantages of the stentless valve do not directly translate to better outcomes for patients. There was no significant difference in short- and long-term outcomes in these patients with aortic stenosis, so we would recommend the stented valve over the stentless valve for the simplicity of the operation. Based on our observation, stented valve is also a better set-up for future valve-in-valve compared to stentless valve.

Recently, at our institution, most surgeons have transitioned towards using stented valves over stentless valves (Figure 3). This leads to an important question: Do we believe stentless valves have any place in modern surgical management of aortic stenosis in situations where a stented valve is also a viable option? We think stentless valves can still be used by surgeons who are comfortable with implanting them if they would prefer to use one over a stented valve. Currently, only one surgeon at our institution who has an abundance of experience performing aortic valve replacement with a stentless valve still sometimes uses stentless valves in his patients with aortic stenosis. This leads us to another point: because stentless valves are more difficult to implant than stented valves, surgeon experience could be a risk factor of long-term mortality when implanting stentless valves in particular. This could potentially explain why our Cox model showed surgeon as being a risk factor for long-term mortality (Table 5). If surgeons are not familiar with stentless valve implantation, a stented valve may be a better option for aortic valve replacement.

Figure 3:

Annual distribution of stentless versus stented valve usage at our institution.

One interesting finding we uncovered in this study was that a larger valve size (size 29 vs size 19–21) was a significant protective factor for operative mortality (Table 4). We also found that the size 29 valve, when compared to all other sizes of valves, was a significant protective factor for long-term mortality per our Cox proportional hazards model (Table 5). These findings are not so surprising given the expected hemodynamic advantages of increasing the diameter of aortic annulus of prothesis by using a larger sized valve. However, this opens a conversation for future research on whether aortic root enlargement in all patients who can tolerate it is the optimal strategy for aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis patients14–19, especially given the recent addition of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement as an available tool in management of aortic stenosis20, which requires larger bioprosthesis (size 25 or bigger) to work effectively.

Our study is limited as a retrospective cohort analysis. The selection of stented or stentless valve was based on surgeons’ preference but not randomized. Additionally, implantation rates of stentless and stented valves were not contemporaneous; we used more stentless valves in the earlier years and more stented valves in the later years (Figure 3). We did not have 100% follow up echocardiographic data for all 1173 patients. Although we have cross-checked its validity in the past and found it to be reliable, the National Data Index database may not always catch all deaths. Lastly, although the University of Michigan Health System is one of the few tertiary centers in the state of Michigan and we thus expect most reoperations on our patients to have occurred here, some patients may still have ended up having a reoperation at an outside hospital. We may have underestimated the cumulative incidence of reoperation.

CONCLUSIONS

Both stented and stentless valves were good options for aortic valve replacement for patients with aortic stenosis with similar short- and long-term outcomes. Although the stentless valve had a better long-term hemodynamic profile, these advantages did not translate into better outcomes. We therefore would recommend the stented valve for the simplicity of its implantation.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Yang is supported by the NHLBI of NIH K08HL130614 and R01HL141891, R01HL151776.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentation: STS 57th Annual Meeting

Disclosure Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relating to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunadian B, Vijayalakshmi K, Thornley AR, de Belder MA, Hunter S, Kendall S, et al. Meta-analysis of valve hemodynamics and left ventricular mass regression for stentless versus stented aortic valves. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepper J, Cheng D, Stanbridge R, et al. Stentless versus stented bioprosthetic aortic valves: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Innovations. 2009;4:61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Straaten EP, Rademakers LM, van Straten AH, et al. Mid-term haemodynamic and clinical results after aortic valve replacement using the Freedom Solo stentless bioprosthesis versus the Carpentier Edwards Perimount stented bioprosthesis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:1174–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harky A, Wong CHM, Hof A, et al. Stented versus Stentless Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Small Aortic Root: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Innovations. 2018;13:404–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bach DS, Patel HJ, Kolias TJ, Deeb GM. Randomized comparison of exercise haemodynamics of Freestyle, Magna Ease and Trifecta bioprostheses after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;50(2):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerqueira RJ, Raimundo R, Moreira S, et al. Freedom Solo® versus Trifecta® bioprostheses: clinical and haemodynamic evaluation after propensity score matching. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vrandecic M, Fantini FA, Filho BG, et al. Retrospective clinical analysis of stented vs. stentless porcine aortic bioprostheses. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18(1):46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz BN, Timek T, Davis A, et al. A propensity matched analysis of outcomes and long term survival in stented versus stentless valves. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murashita T, Okada Y, Kanemitsu H, et al. Efficacy Of Stentless Aortic Prosthesis Implantation for Aortic Stenosis with Small Aortic Annulus. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;63:446–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David TE, Puschmann R, Ivanov J, et al. Aortic valve replacement with stentless and stented porcine valves: a case-match study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. National Death Index. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 12.Yang B, Malik A, Farhat L, et al. Influence of Age on Longevity of a Stentless Aortic Valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(2):500–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verbraecken J, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Van Gaal L. Body surface area in normal-weight, overweight, and obese adults. A comparison study. Metabolism. 2006;55(4):515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam DY, Dharma C, Rocha RV, et al. Early and late outcomes following aortic root enlargement: A multicenter propensity score-matched cohort analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(4):908–919. e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha RV, Manlhiot C, Feindel CM, et al. Surgical Enlargement of the Aortic Root Does Not Increase the Operative Risk of Aortic Valve Replacement. Circulation. 2018;137(15):1585–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang B A Novel Simple Technique to Enlarge the Aortic Annulus by Two Valve Sizes. JTCVS Tech. 2021;5:13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang B, Naeem A. A “Y” Incision/Rectangular Patch to Enlarge the Aortic Annulus by Three Valve Sizes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112(2):e139–e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang B; Naeem A. A “Y” Incision/Rectangular Patch to Enlarge the Aortic Annulus by 4 Valve Sizes in TAV and BAV Patients. CTSNet, Inc. 2021;4:14408741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan D, Brescia AA, Caceres J, Farhat L, Yang B. Management of Ruptured Left Ventricular Outflow Tract. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(1):e21–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleiziffer S, Simonato M, Webb JG, et al. Long-term outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in failed bioprosthetic valves. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(29):2731–2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]