Abstract

Purpose.

Non-pharmacologic adjuncts to opioid analgesics for burn wound debridement enhance safety and cost effectiveness in care. The current study explored the feasibility of using a custom portable water-friendly immersive VR hardware during burn debridement in adults, and tested whether interactive VR would reduce pain more effectively than nature stimuli viewed in the same VR goggles. Methods: Forty-eight patients with severe burn injuries (44 adults and 4 children) had their burn injuries debrided and dressed in a wet wound care environment on Study Day 1, and 13 also participated in Study Day 2.

Intervention:

The study used a within-subject design to test two hypotheses (one hypothesis per study day) with the condition order randomized. On Study Day 1, each individual (n = 44 participants) spent 5 minutes of wound care in an interactive immersive VR environment designed for burn care, and 5 minutes looking at still nature photos and sounds of nature in the same VR goggles. On Study Day 2 (n = 12 adult participants and one adolescent from Day 1), each participant spent 5 minutes of burn wound care with no distraction and 5 minutes of wound care in VR, using a new water-friendly VR system. On both days, during a post-wound care assessment, participants rated and compared the pain they had experienced in each condition.

Outcome measures on Study Days 1 and 2:

Worst pain during burn wound care was the primary dependent variable. Secondary measures were ratings of time spent thinking about pain during wound care, pain unpleasantness, and positive affect during wound care.

Results:

On Study Day 1, no significant differences in worst pain ratings during wound care were found between the computer-generated world (Mean = 71.06, SD = 26.86) vs. Nature pictures conditions (Mean = 68.19, SD = 29.26; t < 1, NS). On secondary measures, positive affect (fun) was higher, and realism was lower during computer-generated VR.

VR vs. No VR (Study Day 2):

Participants reported significantly less worst pain when distracted with adjunctive computer generated VR than during standard wound care without distraction (Mean = 54.23, SD= 26.13 vs 63.85, SD = 31.50, t(11) = 1.91, p < .05, SD = 17.38). In addition, on Study Day 2, “time spent thinking about pain during wound care” was significantly less during the VR condition, and positive affect was significantly greater during VR, compared to the No VR condition. No significant differences in pain unpleasantness or “presence in VR” between the two conditions were found however.

Conclusion:

The current study is innovative in that it is the first to show the feasibility of using a custom portable water-friendly immersive VR hardware during burn debridement in adults. However, contrary to predictions, interactive VR did not reduce pain more effectively than nature stimuli viewed in the same VR goggles.

Keywords: Non-pharmacologic analgesia, virtual reality, acute pain, burn wound debridement

Introduction

Individuals often report severe acute pain during a wide range of medical procedures; controlling such pain safely and cost-effectively is a constant challenge in health care. Repeatedly experiencing acute pain can lead to long term pathological changes in the central processing of nociceptive signals, and can increase the person’s risk of developing costly long term medical problems such as chronic pain [1].

Opioid analgesics have long been the approach of choice for reducing severe acute pain during medical procedures [2–4]. Although such medications are effective, opioid analgesic-related side effects can limit their use, especially when higher doses are required to manage severe pain [5]. Increasing the dose also increases opioid side effects such as constipation, nausea, urinary retention, habituation, dependence, reduced respiration, and risk of addiction [6]. Furthermore, very high doses (opioid overdose) can create fatal respiratory depression. Although opioid analgesia-related overdose deaths are rare in the controlled hospital setting, opioids used in this setting increase risk of diversion and unintended overdose in non-hospital settings (e.g., recreational settings). According to the CDC, “During 1999–2018, opioids were involved in 446,032 deaths in the United States” (Wilson et al., 2020, p 290) [5], with 69,710 opioid related overdose deaths in the USA in 2020 alone. https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2021-07-14-cdc-drug-overdose-deaths-294-2020

In addition to these limitations of opioid analgesics, maladaptive psychological factors can also contribute to the severity and negative impact of pain [7,8,9,10,11]. For example, children with large burns often experience the same burn wound cleaning procedure repeated daily during hospitalization [12, 13]. If a person experiences severe to excruciating pain during one wound care session, their memories of the painful event can increase expectations of pain as they return to the wound care room on a subsequent day [14]. Anxiety [15] and catastrophizing [16] can also make pain worse, and expectations of pain can amplify the intensity of both nociceptive (pain) signals and the pain experience [10]. In addition to the humanitarian need to reduce suffering, adequate pain control has important long-term medical benefits (and associated cost savings) [17], given the findings that more severe acute pain and distress during burn hospitalization predicts poorer post-discharge psychological adjustment [51,52].

Because pain perception can be influenced by psychological factors, psychological treatments can be used to help reduce the amount of acute pain experienced during medical procedures [18–20]. For example, there is growing evidence that during wound care, children with large burns report significantly lower pain during adjunctive immersive virtual reality (VR) treatment compared to control conditions that do not involve VR [12, 41]. VR can also reduce pain during physical/occupational therapy range-of-motion exercises [22] [23]), dental procedures, venipuncture, urological endoscopic prostate treatments, and a growing number of other painful medical procedures [12, 21, 24–35]. Although the mechanism by which VR reduces pain needs further investigation, researchers propose that the variable of “presence” (feeling “there” during VR instead of “here” in the wound care room) may help to make VR a compelling distraction analgesia tool, and there is growing evidence that distraction is a viable mechanism for the analgesic effects of VR for acute pain [47–50].

Burn wound care involves some of the most painful procedures in medicine, and the painful wound cleaning procedures are usually repeated, often daily. To date, several clinical studies on VR analgesia for acute procedural pain have involved participants with severe burns during burn wound care in dry settings (e.g., participants received wound care in their hospital bed). For example, McSherry et al., (2018) [34] studied VR analgesia during wound care in adults with severe burns and showed significantly less opioid use during VR wound care. And several early studies have explored the use of VR during wound care in children [30, 33] or people aged 8 to 65 [35, 40, 63]. These above-mentioned studies in dry settings (e.g., in hospital beds) all compared adjunctive VR vs. standard of care. One challenge in this body of literature is that immersive VR during burn wound care has rarely been compared to other distraction interventions. A recent meta-analysis calls for a shift to studies comparing non-pharmacologic adjunct techniques during burn dressing changes [64].

One question addressed in this study is whether the VR analgesia treatment reported in other VR burn pain studies [12,41] would reduce pain more effectively than a non-interactive, but powerful alternative type of distraction. “Images of nature scenes” (e.g., looking at nature views out of their window of their hospital room vs. no window, or looking at pictures of nature scenes vs. no pictures) have previously been shown to reduce clinical pain [55,56,57,58,65]. We attempted to make the images of nature more powerful in the current study, by having participants watch still images of nature in the wide field of view VR goggles, while listening to sounds from nature in noise cancelling earphones, and participants used their mouse to interact with and control which slides they viewed and at what pace. In both the computer generated VR world and Nature pictures, the VR goggles helped block the participants view of the wound care, so they could not see their burns or wound care procedure, to ideally reduce how much attention they focused on wound care and pain. Using the VR goggles in both treatment conditions also helped keep the wound care nurse blind to the current treatment condition.

Despite the increasing body of evidence supporting the efficacy of immersive VR in burn wound care, there remain gaps in the knowledge and technology utilized. To date, most studies on immersive virtual reality have been conducted with bulky equipment and helmets that do not allow the use of hydrotanks or washings involved in the typical “wet wound” environment. To broaden the use of VR analgesia, we developed a portable, DC battery powered water-friendly VR system used in the current study that is safe in environments that use water. Analog laboratory studies with healthy volunteers have found that compared to passive versions of the same virtual world, interacting with virtual objects significantly increased VR analgesia, significantly increased the participant’s illusion of “being there” in the computer generated world, and significantly increased positive affect (fun) [49,59]. We hypothesized that an adjunctive, interactive, computer-generated virtual world designed for burn care would provide superior pain control compared to (1) an alternative but more passive form of distraction (still photos of nature seen in the same VR goggles on Study Day 1). (2) We also separately hypothesized that VR would reduce pain compared to standard burn care (i.e., wound debridement) without distraction (Study Day 2) for the subset of participants available for Study Day 2. We also sought to explore the effects of VR, using the new water-friendly VR goggles, on a number of secondary outcomes, including presence, i.e., the illusion of “being there” [42, 43], time thinking about pain, and amount of “fun” during the treatment conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted between July 2015 and Dec 2017 with approval from the University of Washington Human Subjects Internal Review Board.

Participant Recruitment.

Participants were recruited from the treating hospital in Seattle by a research coordinator while the participant was in the inpatient/outpatient burn unit. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent was obtained from the participants and/or their legal guardians by medical staff authorized to consent participants for this study.

Inclusion Criteria.

Participants were treated in the burn unit of a large regional burn center in Seattle. They were included in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) able to complete study measures, (2) required to receive at least one burn wound cleaning session, (3) willing/able to provide informed consent (adults) or consent/assent if they were under 18 years (this also required that the parent/legal guardian was able to communicate in English), (4) admitted to the treating hospital, and (5) aged 8–65 years of age. Participants were excluded from this study if they: (1) were unable to complete the study measures, (2) were not undergoing burn wound care, (3) if the adult or the parent/legal guardian of a child were unable to communicate verbally in English, (4) if the participant had a history of seizure disorders, chronic organic brain disorder, severe developmental delay, or history that suggests diminished decisional capacity during the study period, (5) were receiving prophylaxis for alcohol or drug withdrawal, (6) were younger than 8 or older than 65 years of age, (7) had a sensitivity or allergy to opioids, (8) had a pre-existing cardiac dysrhythmia disorder, elevated intracranial pressure, history of severe susceptibility to motion sickness, or a history of seizures, and (9) had burns to the eyes, eyelids or face so severe that this precluded the use of VR hardware.

Apparatus

Burns on an individual’s head or face can be a barrier to wearing a conventional VR helmet. In the current study, a custom DC-battery powered water friendly VR system was brought into the burn wound care hydrotank room on a portable Anthro medical cart with nothing plugged into an electrical outlet. Instead of wearing a head mounted VR helmet, the participant could look into the VR goggles without wearing a helmet (see Figure 2). A custom articulated arm holds the VR goggles for the participant without touching the participant [12, 41]. The goggles can be rotated into a wide range of orientations, locked into the desired orientation, and were mounted to an Anthro medical cart to increase portability. Instead of watching their wound care, during VR treatment, participants looked into the VR goggles designed to distract them. The goggles used were MX90 VR goggles from NVISinc.com, with 90 degrees diagonal field of view, per eye (unusually wide field-of-view/extra peripheral vision and relatively crisp view of the virtual world, at the time the study was initiated, pre-Oculus, and 1,280 × 1,024 pixels resolution per eye). Participants could interact with the computer-generated virtual world or nature pictures by moving and clicking a wireless computer mouse. The fact that the patient was looking into the VR goggles and clicking their mouse in both treatment conditions helped blind the wound care nurse to treatment condition. To help provide converging evidence from multiple senses (sight and sound), participants wore noise cancelling Bose Q35 earphones. The VR system was approved for clinical use and the equipment was periodically checked for safety by hospital infection control. Thin, clear disposable plastic wrap was used to help isolate the equipment and mouse, and the plastic was disposed after each session. Chemical disinfectants were used to systematically clean the equipment after each use, and the goggles and mouse were periodically cleaned using an ultraviolet radiation UV lamp. Cleanliness was also periodically monitored by the hospital’s infection control team. The VR equipment was brought into the hydrotank room when needed, and was removed from the hydrotank room after each use.

Figure 2.

A patient looking into virtual reality during a burn wound cleaning session. Photo and copyrights Hunter Hoffman, UW, www.vrpain.com

MEASURES

The Graphic Rating Scale was used to measure pain on several domains. The GRS is a 10-unit horizontal line labeled with number and word descriptors. Descriptor labels were associated with each mark to help the respondent rate pain magnitude in each domain. The Graphic Rating Scale (GRS) has a great deal of evidence supporting its reliability and validity as a subjective measure of pain [44, 45]. It has also been validated for participants aged 8 and older [46]. After the wound care session, on Study Day 1, during a single assessment period, participants answered each pain rating twice, once for their pain during the computer-generated immersive condition, and the following question asked them to rate their pain while viewing nature pictures. The treatment order was randomized, such that approximately half of the participants received nature pictures first and half received the computer-generated world first.

After each wound cleaning session was completed, participants received the following instructions. “Please indicate how you felt during the wound cleaning today by making a mark anywhere on the line. Your response doesn’t have to be a whole number.” In the study, several separate queries were made (see example and paragraph below), with a pictorial example of the labeled graphic rating scale shown for each query. After the wound care session, on Study Day 1, participants answered each pain rating twice, once for their pain during the computer-generated immersive condition, and once for their pain while viewing nature pictures (see Appendix to see the full Day 1 GRS pain ratings questionnaire). Both questions described each treatment as a “game” in the assessment tools, to help minimize response bias.

Rate your WORST pain intensity during the Virtual Reality Snowball game:

Rate your WORST pain intensity during the Nature Pictures Game.

Similarly, on Study Day 2, participants answered each pain rating twice, once for their pain during the computer-generated VR, and once for the pain during No VR during an equivalent portion of their wound care session.

Rate your WORST pain intensity during the Virtual Reality Snowball game:

Rate your WORST pain intensity during No VR.

Experimental Design

Study Day 1 (n = 48 participants).

The current study used a statistically powerful within-subjects, within wound-care design [13]. All participants received their usual pain medications, i.e., VR was always used adjunctively, in addition to usual traditional pain medications. To reduce bias on Study Day 1, the two VR treatments were designed to look similar to an outside observer, and the wound care nurses remained blind to our hypothesis and blind to treatment condition on Study Day 1.

On Study Day 1, the participant’s wound care was divided into two equivalent (two approx. 5 minute) segments and used identical VR hardware (e.g., the same VR goggles) in each of two treatment conditions (i.e., computer generated VR vs. nature pictures). The independent variable was the content of what participants saw in the goggles. During one condition, participants looked into the custom VR goggles and saw the nature pictures (e.g., still photographs of islands in the Great Barrier Reef, gardens, etc., that participants could see as 2D photos while looking into the virtual reality goggles, see Figure 3). Participants could interact with/progress to the next photo by clicking the wireless computer mouse. The use of nature pictures to reduce clinical pain is a relatively novel research topic. To our knowledge there are no validated stimulus sets for still nature pictures/photographs designed for pain control. The current exploratory nature pictures stimulus set was created from a portfolio of nature photos taken by our team, copyrighted by HH, www.vrpain.com. During the nature pictures, using Bose Q35 noise cancelling earphones, participants heard relaxing sounds from nature (e.g., crickets chirping, birds singing) played in the background during the VR slide show that participants passively viewed in the articulated arm mounted MX90 VR goggles.

Figure 3.

A screenshot example of Nature pictures patients viewed in VR goggles on Study Day 1, photo and copyright

Hunter Hoffman, U.W., www.vrpain.com

During an equivalent portion of the same wound care session, and using the same VR goggles, participants saw/experienced SnowWorld (see Figure 4), an interactive 3D computer generated virtual reality world, where participants used their wireless computer mouse to look around, aim and throw snowballs at creatures in virtual reality, including snowmen, penguins, flying fish, and wooly mammoths. As part of the “interactivity,” the creatures in virtual reality reacted when hit by the participant’s snowballs, and Snowmen playfully threw snowballs back. In this VR world, participants could hear sound effects (e.g., mammoths trumpeting angrily when hit by a snowball, etc.), and background music in the Bose Q35 noise cancelling earphones. The interactive computer generated VR world software (copyrighted University of Washington, Seattle) was developed by our team at the UW (iteratively created in sequential collaboration with three separate teams of commercial professional worldbuilding companies, over several years (www.vrpain.com).

Figure 4.

A screenshot of the virtual reality world SnowWorld, owned by the University of Washington, Seattle, image by Ari Hollander and Howard Rose, copyright Hunter Hoffman, U.W., www.vrpain.com

Each participant sequentially experienced both of the two 5-minute conditions using the water-friendly VR goggles during wound care, on Study Day 1. Treatment order was block randomized, with treatment order assigned via computer-generated random sequences from random.org. In summary, during both nature pictures, and during computer generated VR, the research staff positioned the VR goggles weightlessly near the participant’s eyes, with little or no physical contact between the VR goggles and the participant, using an articulated arm goggle holder [12, 41]. During the nature pictures VR, on Day 1, the participant looked into the VR goggles, and saw a series of still photographs for 5 minutes, clicking the mouse to view the next Nature picture ad lib, and during the computer-generated immersive world, participants used a computer mouse to look around, aim and click the mouse button to throw snowballs while floating slowly through a 3D canyon for 5 minutes (treatment order randomized).

Shortly after the Study Day 1 wound care session, during a single questionnaire, the participants briefly rated their pain twice. They rated how much pain they had experienced during wound care during the nature pictures vs. during computer generated VR, using graphic rating scales to measure their subjective pain ratings. The participant was returned to their hospital bed, the research staff cleaned and disinfected the VR, and the VR cart was removed from the wound care hydrotank room.

Statistical Analyses

On Study Day 1, our primary hypothesis stated that supplementing standard analgesic care (e.g., opioid analgesics) with computer-generated virtual reality would be significantly more effective at reducing participant’s self-reports of worst pain they experienced during wound debridement than adjunctive “pictures from nature”, seen through the same VR goggles during the same wound care session. We further predicted that on Study Day 2, the adjunctive computer generated virtual reality would be more effective than “treatment as usual”, (no VR during wound debridement, treatment order randomized). Within-subjects analyses (paired t-tests) were used to test these two hypotheses. Participant’s “worst pain” rating during treatment served as the primary dependent variable, with the treatment condition as the independent variable. Paired t-tests were used to test whether, as expected, participants reported significantly lower levels of pain during wound care (worst pain ratings) during computer-generated VR compared to pain during pictures of nature, seen in the same virtual reality goggles on Study Day 1. Retrospective worst pain ratings after the Study Day 2 wound care session were also used to compare computer generated VR vs. no VR (treatment as usual).

T-tests were used in secondary analyses to determine whether there was an effect of treatment condition on the secondary outcome variables of pain unpleasantness, time spent thinking about pain during wound care, fun during wound care (a surrogate for positive affect), presence and nausea. IBM SPSS (2019) statistical analyses of the primary and secondary hypotheses involved a priori paired sample t-tests, with alpha = 0.05 (two tailed for Study Day 1, one tailed for Study Day 2).

RESULTS of Study Day 1.

Demographics. Out of 56 participants screened, forty-eight participants aged 8 to 65 (four people under 18 years old, and 44 people aged 18–65) met our apriori inclusion criterion. Seventy percent of the participants were male, and 30% were female. The ethnicity of the participants was 83% Caucasian, 9% Hispanic, 4% Native American, 2% Black, 2% unknown. The mean size of the participants’ severe burn injuries was 14% Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) burned (range 1–50% TBSA), SD = 10.1.

The most commonly injured body part was legs = 71%, followed by hand burns = 63%, arm, 57%, back = 29%, face burns = 34%, stomach, 30%, foot =29%, chest = 21%, neck = 11%, and buttocks = 7%. The etiology of the burns were as follows: flame = 71%, scald = 4%, grease = 13%, flash = 7%, other = 5%.

Interactive immersive virtual reality vs. still nature pictures.

As shown in Table 1, on Study Day 1, 48 participants received a computer-generated virtual world during one 5-minute segment of their wound care, and looked at photographs of nature during an equivalent 5-minute session (treatment order randomized). Contrary to predictions, pain was not significantly lower during the computer-generated VR world on Study Day 1. Moreover, participants’ illusion of “being there” in virtual reality was not significantly stronger during the computer-generated VR than during the VR nature picture condition, as viewed using the same VR goggles. As predicted, participants reported more positive affect (“fun”) during computer generated VR than during the nature pictures condition. However, participants rated the realism of the nature pictures significantly higher than the realism of the somewhat cartoonish computer-generated VR world.

Table 1.

Study Day 1, 48 participants aged 8-and older (VR still pictures vs. computer generated VR), 4 children and 44 adults).

| VR Nature Pictures | VR SnowWorld | Study Day 1 (n = 48 participants on Study Day 1) Within-subjects paired t-tests, two tailed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 44.69 (29.62) | 38.13 (25.24) | t(47) = 1.50, p = . 14, SD = 30.29 |

| Unpleasant | 56.60 (30.17) | 54.79 (30.40) | t(46) < 1, NS, SD = 25.97 |

| Worst pain1 | 68.19 (29.26) | 71.06 (26.86) | t(46) < 1, NS, SD = 23.49 |

| Fun | 46.33 (34.97) | 71.67 (27.84) | t(44) = 5.52, p <.001, SD = 30.77 |

| Presence | 38.56 (29.46) | 41.11 (29.58) | t(45) < 1 NS, SD = 29.90 |

| Real | 60.00 (36.62) | 40.44 (29.79) | t(44) = 4.83, p < .001, SD = 34.14 |

| Nausea | 0.43 (2.95) | 1.74 (8.51) | t(45) = 1.18, p = .24, SD = 7.49 |

For the primary DV, worst pain, paired samples effect size Cohen’s d = −0.18, CI = −0.46 to 0.12

Study Day 2

Out of the 48 people in Study 1, 13 people went on to participate in VR on a second study day (Study Day 2). Most of the dropouts were not patient initiated. After Study Day 1, wound care sessions were often spent training participants how to clean their own burn wounds, and letting them practice cleaning and rebandaging their own wounds, in anticipation that they would soon be discharged from the hospital. Furthermore, patients who knew before signing up that they were expecting to only receive one wound care session were still eligible to participate on Study Day 1. Treatment order for Day 1 did not affect dropout rate (i.e., there was no differential dropout between people randomized to get VR first vs. those who received Nature Pictures first). The immersive environment of Study Day 1 (SnowWorld) was the same as Study Day 2.

Study Day 2 Treatment Conditions (n = 13 participants who previously participated during Study Day 1).

Study Procedure.

Out of the 48 participants who participated in Study Day 1, 13 participants (12 adults and one child) also completed a Study Day 2 wound care session (see limitation section of Discussion). During Study Day 2, participants received one portion of their wound care with No VR (standard pain medications only, with no distraction), and received an equivalent portion of their wound care during adjunctive interactive computer-generated VR in the VR goggles, treatment order randomized. After the wound care session on Study Day 2, participants retrospectively answered each pain rating twice, once for their pain during wound care during No VR, and once for their pain during wound care during the computer-generated VR. After their pain ratings, the participant was returned to their hospital beds, the VR cart was removed from the wound care room, and the research staff cleaned and disinfected the VR equipment.

RESULTS of Study Day 2.

Interactive immersive virtual reality vs. No VR.

The current Study Day 2 explored whether it was feasible to use VR during wound care in the wet wound care environment. As shown in Table 2, on Study Day 2, pain during No VR was compared to pain during the adjunctive computer-generated VR (treatment order randomized), for the 12 adult participants and one adolescent. As predicted, the participants reported significant reductions in pain during VR vs. during No VR for worst pain during wound care, as well as for time spent thinking about pain during wound care. Pain unpleasantness during wound care did not differ significantly between the two conditions, although the differences were in the predicted direction (i.e., lower during VR vs. during No VR). Participants rated their illusion of presence as a mild sense of going inside the virtual world during the computer-generated VR, and rated the virtual world as “somewhat real.”

Table 2,

Study Day 2, all participants (n = 13) including 12 adult participants and one adolescent participant, No VR vs. the computer-generated VR.

| No VR | Computer generated VR | Study Day 2 (n = 13 participants on Study Day 2). Within-subjects paired t-tests, one-tailed. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worst pain | 63.85 (31.50) | 54.23 (26.13) | t(12) = 2.08, p < .05, SD = 16.64 |

| Time | 56.15 (32.80) | 30.77 (18.47) | t(12) = 3.03, p < .01, SD = 30.17 |

| Unpleasant | 53.85 (33.05) | 46.54 (25.12) | t(12) < 1 NS |

| Fun | 10.77 (16.05) | 62.69 (34.19) | t(12) = 5.32, p < .001, SD = 35.21 |

| Nausea | 6.67 (16.14) | 0 | t(11) = 1.43, p = .09, NS, SD = 16.14 |

| Presence | 40.00 (33.85) | NA | |

| Real | 37.50 (25.98) | NA |

As shown in Table 3, analyzing the adults alone also showed the predicted pattern of results, making this the first study to show water-friendly VR analgesia in adults.

Discussion.

Our primary hypothesis (tested on Study Day 1) was that immersive, interactive virtual reality would increase analgesia compared to a condition of viewing nature still pictures using identical hardware. Contrary to predictions, interactive computer generated VR did not increase presence in VR and did not reduce pain more effectively compared to viewing nature pictures. The more immersive computer-generated VR resulted in more positive affect (significantly higher ratings of fun during wound care); however, this did not translate into increased analgesia. However, we speculate that creating more positive affect may help reduce anticipatory anxiety and may reduce avoidance of painful medical procedures. Similarly, although participants rated the nature slides (seen in the VR goggles) as significantly more realistic than that of the computer-generated condition, the nature pictures condition and interactive computer generated VR were equally effective at reducing pain. Thus, the extent to which a visual image was rated as being more fun or more realistic, did not appear to have an impact on pain ratings.

Immersive VR during burn wound care has rarely been compared to other distraction interventions in clinical studies; however, a clinical case series [13] showed that immersive virtual reality elicited a stronger illusion of presence than a conventional non-VR video game. In that early case study, immersive VR was found to be more effective at reducing pain than playing a 2-dimensional, traditional, console video game during the same burn wound care session. The current study is among the first controlled clinical trials to compare two VR treatments for acute pain in a clinical population.

The findings from Study Day 2 supported the feasibility of a water-friendly, portable VR system. A limitation that has existed for VR as a possible pain treatment during burn wound care is that many people have burns on their heads and face, which can make it difficult or not possible to wear a conventional VR helmet. Previous studies have demonstrated that a portable, water-friendly VR system reduced the pain of children with unusually large severe burn injuries [12, 41]. The current study demonstrated that this finding holds for adults with burn injuries.

The current results (on Study Day 2) show that water-friendly virtual reality can significantly reduce procedural pain in adults during painful wound care sessions. Compared to standard of care (no VR), 12 adults reported significant reductions in worst pain ratings during adjunctive immersive VR (15% less in VR); they also spent significantly less time thinking about their pain during wound care (51% less during VR), and reported significantly more positive emotion when in virtual reality during their burn wound care (80% more “fun” during VR compared to standard of care, no VR). They further reported less pain unpleasantness during VR than the non-VR condition (14% less in VR), although this effect of VR on unpleasantness was not found to be statistically significant.

Limitations.

Several limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of the current study. One limitation is that we were not able to include a baseline pain rating during Study Day 1. Baseline would have represented three conditions in one wound care session which would have been a prohibitive strain on participants. Another limitation was the low number of participants in Study Day 2. This was primarily a function of participants not requiring the same type of aggressive wound care on the second day of the study. On Study Day 1, to help reduce bias, the wound care nurses remained unaware of the hypothesis and did not know which treatment the patient was receiving at any given time (computer-generated VR vs. Nature pictures). On Study Day 2, the wound care nurses could not be blinded because it was obvious whether the patient was either getting No VR (treatment as usual) or was getting adjunctive VR.

The current study measured the patient’s memory for pain during wound care. According to Noel et al., 2017 [61], p 1, “pain memories have been shown to be a powerful predictor of subsequent pain experiences in acute procedural and experimental pain settings.” However, one possible disadvantage of measuring pain in this manner, shortly after all wound care is completed, is that it is possible that the more recent wound care segment could influence the patient’s responses. As pointed out by Ebbinghaus in the 1800s, information recently learned is often more easily retrieved [62 see also more recent 66,67]. Fortunately, the within subject treatment order on Study Day 1 was randomized and participants were equally likely to get either condition first. Randomizing treatment order should thus mitigate any recency effects. Similarly, on Day 2 treatment order was randomized.

Other limitations are as follow; Although the computer-generated VR condition is arguably more interactive than clicking the mouse to control the nature photo stills, the current study is not a comparison of interactive compared to non-interactive VR. A clinical study manipulating only interactivity (e.g., interactive computer-generated VR versus passive computer-generated VR of the same World) would be needed to isolate the influence of interactivity on VR analgesia in clinical settings. Although previous laboratory studies with healthy volunteers have shown that interactivity significantly increases VR analgesia [47–50], whether interactivity significantly increases analgesia in clinical pain studies remains an interesting question for future research. A final limitation is that on Study Day 2, participants received “no VR” during one portion of their wound care and immersive VR during an equivalent portion of their wound care. Given the nature of this arm of the study design it is possible participants may have been able to directly connect study questions to the use of VR equipment. Alternatively, in a between-groups study design, each individual is exposed to only one treatment. Future large comparative randomized controlled between-group research studies comparing VR to a traditional and widely used distraction technique (e.g., music) during burn wound care are needed, ideally blinding participants and/or assessors to treatment conditions, to help reduce bias. For example, in a study comparing a highly immersive VR treatment group vs. a plausible control treatment group (e.g., music distraction with no VR), vs. a No distraction control group, patients can be randomly assigned to treatment group before consenting. Then the consent forms can fully inform the patients about the treatment they will receive, without mentioning that there is another group receiving a different distraction treatment. This way, patients can remain blind to the between groups manipulation (reducing bias), without deceiving the patients.

Despite the possible disadvantages mentioned above, the within-subject design had a number of advantages. A within-subject design is more statistically powerful, because confounds are identical in the two treatment conditions, and cancelled out. For example, the amount of pain medications at the time of treatment, was essentially identical in each condition. Similarly, the amount of sleep participants had the night before, and similar factors that can influence pain perception were also controlled [13,40]. Each person serves as their own control so there is no inter-subject variance and because both treatment conditions occur during the same wound care session, there is no inter-day variance, and there was no missing data on Study Day 1.

The current study is innovative in that it is one of the first in the VR literature to compare computer-generated VR to a competitive distraction using identical hardware during a clinical procedure. We were able to demonstrate the viability of a portable VR system with adult wound care as well as its analgesic efficacy.

Supplementary Material

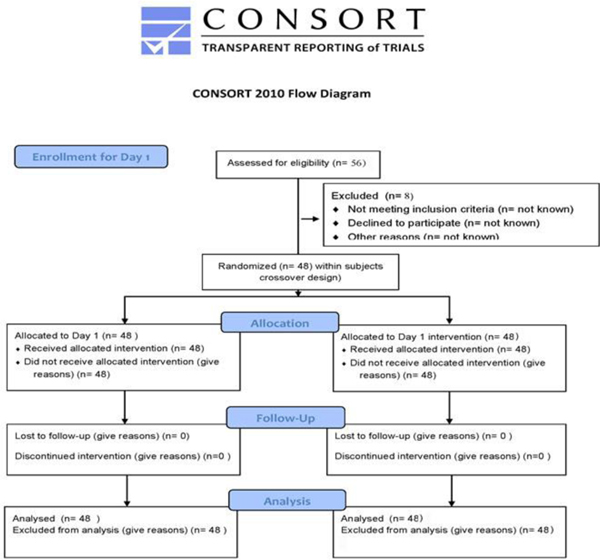

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for subject enrollment, allocation and follow-up. The University of Washington IRB prohibits data collection on eligible research subjects who do not participate for any reason. Thus information on potential subjects assessed, excluded, or who refused is not available.

Table 3,

Study Day 2, adult participants only (n = 12), aged 18–65, No VR vs. the computer-generated VR (75% male, 25% female)

| No VR | Computer generated VR | Study Day 2 (n = 12 adult participants on Study Day 2). Within-subjects paired t-tests, one-tailed. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worst pain | 64.17 (32.88) | 54.58 (27.26) | t(11) = 1.91, p < .05, SD = 17.38 |

| Time | 57.50 (33.88) | 28.33 (16.97) | t(11) = 3.59, p < .005, SD = 28.11 |

| Unpleasant | 54.17 (34.50) | 48.75 (24.88) | t(11) < 1, NS |

| Fun | 11.67 (16.42) | 59.58 (33.74) | t(11) = 4.95, p < .001, SD = 33.54 |

| Nausea | 7.27 (16.79) | 0 | t(10) = 1.44, p = .09, NS, SD = 16.79 |

| Presence | 36.36 (32.95) | ||

| Real | 33.64 (23.36) |

Highlights.

Using a custom portable water-friendly immersive VR hardware during burn debridement in adults is feasible.

During wound debridement, participants reported significantly less worst pain intensity when distracted with VR than in standard wound care without distraction.

Contrary to predictions, interactive VR did not increase presence or reduce pain more effectively than nature stimuli viewed in the same VR goggles.

Participants gave significantly higher ratings of positive affect during the computer-generated world condition compared to participants’ ratings during the nature pictures condition.

Funding.

This research was supported by NIH grant R01GM042725 to DP, and Mayday Fund to WJM and HH

Footnotes

Clinical Trials number = NCT02729259

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References.

- 1.Topham L, et al. , The transition from acute to chronic pain: dynamic epigenetic reprogramming of the mouse prefrontal cortex up to 1 year after nerve injury. Pain, 2020. 161(10): p. 2394–2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne JC, The brain on opioids. Pain, 2018. 159 Suppl 1: p. S24–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krane EJ and Walco GA, With Apologies to Lennon and McCartney, All We Need is Data: Opioid Concerns in Pediatrics. Clin J Pain, 2019. 35(6): p. 461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre MK, et al. , Progress of clinical practice on the management of burn-associated pain: Lessons from animal models. Burns, 2016. 42(6): p. 1161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson N, et al. , Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(11): p. 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malchow RJ and Black IH, The evolution of pain management in the critically ill trauma patient: Emerging concepts from the global war on terrorism. Crit Care Med, 2008. 36(7 Suppl): p. S346–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly TJ, Palermo TM, and Newton-John TRO, Parent cognitive, behavioural, and affective factors and their relation to child pain and functioning in pediatric chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 2020. 161(7): p. 1401–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melzack R and Wall PD, Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science, 1965. 150(3699): p. 971–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnie KA, Chambers CT, and Spellman CM, Mechanisms of distraction in acute pain perception and modulation. Pain, 2017. 158(6): p. 1012–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields HL, How expectations influence pain. Pain, 2018. 159 Suppl 1: p. S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heathcote LC, et al. , Child attention to pain and pain tolerance are dependent upon anxiety and attention control: An eye-tracking study. Eur J Pain, 2017. 21(2): p. 250–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman HG, et al. , Immersive Virtual Reality as an Adjunctive Non-opioid Analgesic for Predominantly Latin American Children With Large Severe Burn Wounds During Burn Wound Cleaning in the Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Study. Front Hum Neurosci, 2019. 13: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hoffman HG, et al. , Virtual reality as an adjunctive pain control during burn wound care in adolescent patients. Pain, 2000. 85(1–2): p. 305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel M, et al. , Remembering pain after surgery: a longitudinal examination of the role of pain catastrophizing in children’s and parents’ recall. Pain, 2015. 156(5): p. 800–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman CR and Turner JA, Psychological control of acute pain in medical settings. J Pain Symptom Manage, 1986. 1(1): p. 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, and Kirsch I, Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain, 2001. 91(1–2): p. 147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery GH, et al. , A randomized clinical trial of a brief hypnosis intervention to control side effects in breast surgery patients. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2007. 99(17): p. 1304–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson DR, Practical applications of psychological techniques in controlling burn pain. J Burn Care Rehabil, 1992. 13(1): p. 13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson DR and Jensen MP, Hypnosis and clinical pain. Psychol Bull, 2003. 129(4): p. 495–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson DR, Tininenko J, and Ptacek JT, Pain during burn hospitalization predicts long-term outcome. J Burn Care Res, 2006. 27(5): p. 719–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman HG, et al. , Virtual reality hand therapy: A new tool for nonopioid analgesia for acute procedural pain, hand rehabilitation, and VR embodiment therapy for phantom limb pain. J Hand Ther, 2020. 33(2): p. 254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrougher GJ, et al. , The effect of virtual reality on pain and range of motion in adults with burn injuries. J Burn Care Res, 2009. 30(5): p. 785–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman HG, et al. , Feasibility of articulated arm mounted Oculus Rift Virtual Reality goggles for adjunctive pain control during occupational therapy in pediatric burn patients. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw, 2014. 17(6): p. 397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honzel E, et al. , Virtual reality, music, and pain: developing the premise for an interdisciplinary approach to pain management. Pain, 2019. 160(9): p. 1909–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrett B, et al. , A rapid evidence assessment of immersive virtual reality as an adjunct therapy in acute pain management in clinical practice. Clin J Pain, 2014. 30(12): p. 1089–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keefe FJ, et al. , Virtual reality for persistent pain: a new direction for behavioral pain management. Pain, 2012. 153(11): p. 2163–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman HG, Virtual-reality therapy. Sci Am, 2004. 291(2): p. 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trost Z, et al. , Virtual reality approaches to pain: toward a state of the science. Pain, 2021. 162(2): p. 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffs D, et al. , Effect of virtual reality on adolescent pain during burn wound care. J Burn Care Res, 2014. 35(5): p. 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khadra C, et al. , Projector-based virtual reality dome environment for procedural pain and anxiety in young children with burn injuries: a pilot study. J Pain Res, 2018. 11: p. 343–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khadra C, et al. , Effects of a projector-based hybrid virtual reality on pain in young children with burn injuries during hydrotherapy sessions: A within-subject randomized crossover trial. Burns, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kipping B, et al. , Virtual reality for acute pain reduction in adolescents undergoing burn wound care: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Burns, 2012. 38(5): p. 650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McSherry T, et al. , Randomized, Crossover Study of Immersive Virtual Reality to Decrease Opioid Use During Painful Wound Care Procedures in Adults. J Burn Care Res, 2018. 39(2): p. 278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faber AW, Patterson DR, and Bremer M, Repeated use of immersive virtual reality therapy to control pain during wound dressing changes in pediatric and adult burn patients. J Burn Care Res, 2013. 34(5): p. 563–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman HG, et al. , Water-friendly virtual reality pain control during wound care. J Clin Psychol, 2004. 60(2): p. 189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman HG, et al. , Virtual reality helmet display quality influences the magnitude of virtual reality analgesia. J Pain, 2006. 7(11): p. 843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman HG, et al. , Virtual reality as an adjunctive non-pharmacologic analgesic for acute burn pain during medical procedures. Ann Behav Med, 2011. 41(2): p. 183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maani CV, et al. , Virtual reality pain control during burn wound debridement of combat-related burn injuries using robot-like arm mounted VR goggles. J Trauma, 2011. 71(1 Suppl): p. S125–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman HG, et al. , Virtual Reality Analgesia for Children With Large Severe Burn Wounds During Burn Wound Debridement. Front Virtual Real, 2020. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slater M, Usoh M, and Steed A, Depth of presence in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ, 1994. 3: p. 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slater M, and Wilbur S, A framework for immersive virtual environments (FIVE): speculations on the role of presence in virtual environments. . Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ, 1997. 6: p. 603–616. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen MP, The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain, 2003. 4(1): p. 2–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson A and Hoggart B, Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs, 2005. 14(7): p. 798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tesler MD, et al. , The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity. Res Nurs Health, 1991. 14(5): p. 361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffman HG, et al. , Manipulating presence influences the magnitude of virtual reality analgesia. Pain, 2004. 111(1–2): p. 162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Ghamdi NA, et al. , Virtual Reality Analgesia With Interactive Eye Tracking During Brief Thermal Pain Stimuli: A Randomized Controlled Trial (Crossover Design). Front Hum Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wender R, et al. , Interactivity Influences the Magnitude of Virtual Reality Analgesia. J Cyber Ther Rehabil, 2009. 2(1): p. 27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffman HG. Interacting with virtual objects via embodied avatar hands reduces pain intensity and diverts attention. Sci Rep. 2021. May 21;11(1):10672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards RR, Magyar-Russell G, Thombs B, Smith MT, Holavanahalli RK, Patterson DR, Blakeney P, Lezotte DC, Haythornthwaite JA, Fauerbach JA. Acute pain at discharge from hospitalization is a prospective predictor of long-term suicidal ideation after burn injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007. Dec;88(12 Suppl 2):S36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fauerbach JA, McKibben J, Bienvenu OJ, Magyar-Russell G, Smith MT, Holavanahalli R, Patterson DR, Wiechman SA, Blakeney P, Lezotte D. Psychological distress after major burn injury. Psychosom Med. 2007. Jun;69(5):473–82. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e31806bf393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vincent E, Battisto D, Grimes L, McCubbin J. The effects of nature images on pain in a simulated hospital patient room. HERD. 2010. Spring;3(3):42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emami E, Amini R, Motalebi G. The effect of nature as positive distractibility on the Healing Process of Patients with cancer in therapeutic settings. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018. Aug;32:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.05.005. Epub 2018 May 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lechtzin N, Busse AM, Smith MT, Grossman S, Nesbit S, Diette GB. A randomized trial of nature scenery and sounds versus urban scenery and sounds to reduce pain in adults undergoing bone marrow aspirate and biopsy. J Altern Complement Med. 2010. Sep;16(9):965–72. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furness PJ, Phelan I, Babiker NT, Fehily O, Lindley SA, Thompson AR. Reducing Pain During Wound Dressings in Burn Care Using Virtual Reality: A Study of Perceived Impact and Usability With Patients and Nurses. J Burn Care Res. 2019. Oct 16;40(6):878–885. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irz106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharar SR, Alamdari A, Hoffer C, Hoffman HG, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Circumplex Model of Affect: A Measure of Pleasure and Arousal During Virtual Reality Distraction Analgesia. Games Health J. 2016. Jun;5(3):197–202. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2015.0046. Epub 2016 May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noel M, Rabbitts JA, Fales J, Chorney J, Palermo TM. The influence of pain memories on children’s and adolescents’ post-surgical pain experience: A longitudinal dyadic analysis. Health Psychol. 2017. Oct;36(10):987–995. doi: 10.1037/hea0000530. Epub 2017 Jul 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ebbinghaus H (1913/1885) Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Ruger HA, Bussenius CE, translator. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoffman HG, Patterson DR, Seibel E, Soltani M, Jewett-Leahy L, Sharar SR. Virtual reality pain control during burn wound debridement in the hydrotank. Clin J Pain. 2008. May;24(4):299–304. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164d2cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lauwens Y, Rafaatpoor F, Corbeel K, Broekmans S, Toelen J, Allegaert K. Immersive Virtual Reality as Analgesia during Dressing Changes of Hospitalized Children and Adolescents with Burns: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Children (Basel). 2020. Oct 22;7(11):194. doi: 10.3390/children7110194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li H, Zhang X, Wang H, Yang Z, Liu H, Cao Y, Zhang G. Access to Nature via Virtual Reality: A Mini-Review. Front Psychol. 2021. Oct 5;12:725288. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.https://www.davemanuel.com/investor-dictionary/recency-bias/ accessed Jan 22, 2022.

- 67.Kahneman Daniel; Fredrickson Barbara L.; Schreiber Charles A.; Redelmeier Donald A. (1993). “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End”. Psychological Science. 4 (6): 401–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00589.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.