Abstract

For over 50 years, our group has been involved in synthetic studies on biologically active cyclitols including carbasugars. Among a variety of compounds synthesized, this review focuses on carbaglycosylamine glycosidase inhibitors, highlighting the following: (1) the naturally occurring N-linked carbaoligosaccharide α-amylase inhibitor acarbose and related compounds; (2) the novel synthetic β-glycosidase inhibitors, 1′-epi-acarviosin and its 6-hydroxy analogue as well as β-valienaminylceramide and its 4′-epimer; (3) the discovery of the β-glycosidase inhibitors with chaperone activity, N-octyl-β-valienamine (NOV) and its 4-epimer (NOEV); and (4) the recent development of the potential pharmacological chaperone N-alkyl-conduramine F-4 derivatives.

Keywords: synthesis, carbasugars, carbaglycosylamines, N-linked carbaoligosaccharides, glycosidase inhibitors, pharmacological chaperones

1. Introduction

In the early 1960s, Prof. Umezawa and co-workers1) began to work on the total synthesis and chemical modification of the aminocyclitol antibiotic kanamycin, according to their proposed relative structure of the main component kanamycin A (1) (Fig. 1a). One of the authors (SO) was conducting joint research with Prof. Umezawa’s group at Keio University, synthesizing the model compounds aminocyclohexyl glucosaminides.2) The work was gradually extended to collaboration with Prof. Suami at the same university and the synthesis of aminocyclitols of biochemical interest,3,4) including the two main components of aminocyclitol antibiotics, streptamine (2) and 2-deoxystreptamine (3), leading to a practical synthesis of 3 from myo-inositol (4).5) This synthesis was later applied to the preparation of specifically 14C-labeled 36) to elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of the antibiotic neomycin.7,8) The findings were then utilized to develop the microbial production of novel neomycin analogs (hybrimycins) by replacement of 3 with various aminocyclitols.9,10) Since then, SO has been involved in the synthesis of new bioactive inositol derivatives, such as anhydro- and dianhydroinositols,11) and highly oxygenated cyclohexane compounds, such as crotepoxide.12)

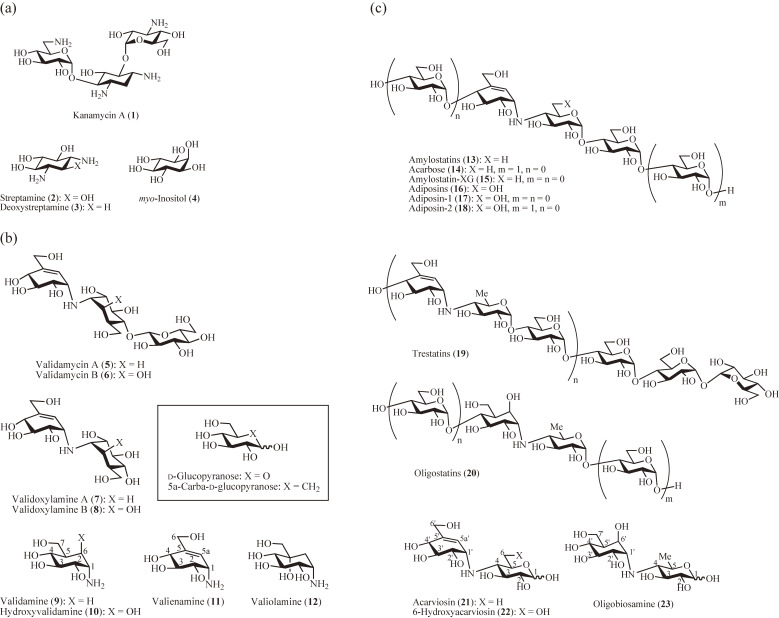

Figure 1.

Naturally occurring aminocyclitol and carbaglycosylamine antibiotics and glycosidase inhibitors. (a) Aminocyclitol antibiotic kanamycin A, two main aminocyclitol components of aminocyclitol antibiotics and naturally abundant cyclitol. (b) Agricultural antibiotics validamycins A and B, their carbadisaccharide active cores and carbaglycosylamine components. Inset: Glucose and carbaglucose with IUPAC nomenclature. (c) Carbaoligosaccharide α-amylase inhibitors and their carbadisaccharide active cores.

In 1970, the discovery of an antibiotic with potent trehalase inhibitory activity, validamycin A (5) (Fig. 1b), was reported by Takeda Chemical Co. Ltd.13–15) Structural studies demonstrated the presence of the active core N-linked carbadisaccharide validoxylamine A (7), composed of the aminocarbasugars validamine (9)16) and its unsaturated derivative valienamine (11).17) Carbasugars, originally referred to as pseudo-sugars, are carbocyclic analogues of carbohydrates (Fig. 1b, inset).18) The α,α-trehalose-like structure of 7 is believed to mimic the transition state of the trehalase reaction. In addition to 5, validamycin B14) (6) was isolated and found to have a core validoxylamine B (8) composed of hydroxyvalidamine16) (10) instead of 9. Later, the aminocarbasugars 9, 10, and 11 were also isolated together with a new aminocarbasugar α-glucosidase inhibitor valiolamine (12) from validamycin fermentation broth.19)

It is noteworthy that 3 years before the discovery of 5, some carbasugars were chemically synthesized by McCasland and co-workers,20–22) with the hope that these compounds, due to their structural similarity to natural sugars, might be incorporated into biological systems to exhibit a certain biological activity.

In 1977, a homologous series of α-amylase inhibitors including acarbose (14) (Fig. 1c) was discovered by Bayer Co.23,24) and characterized as N-linked carbaoligosaccharides with the common active core valienamine-containing N-linked carbadisaccharide acarviosin24) (21), which like 7 is considered as a transition-state analogue inhibitor of α-amylase. Among them, 14 was obtainable as a sole product and has been used clinically for the treatment of type II insulin-independent diabetes.25) Following the discovery by Bayer Co., other structurally related α-amylase inhibitors, amylostatins (13) including amylostatin-XG26) (15), adiposins27) (16) including adiposin-1 (17) and -2 (18), trestatins28) (19) and oligostatins29) (20) have been discovered in Japan, all of which contain N-linked carbadisaccharide cores: 21 for 13 and 19, 6-hydroxyacarviosin (22) for 16, and oligobiosamine (23) for 20.

Since the discovery of these carbasugar-containing glycosidase inhibitors, our interest has been extended to include biologically active carbasugars and, as a result, the total synthesis of 5, 6, 14, and related compounds has been achieved.18,30) In addition, the concept of the carbaglycosylamine-based transition state analogue inhibitors has been applied to design specific inhibitors of β-glycosidases. Particularly, β-valienaminylceramide ((E)-24) and its 4′-epimer (E)-25 (Fig. 2a) have been shown to be potent and specific inhibitors of gluco- and galactocerebrosidase, respectively.31)

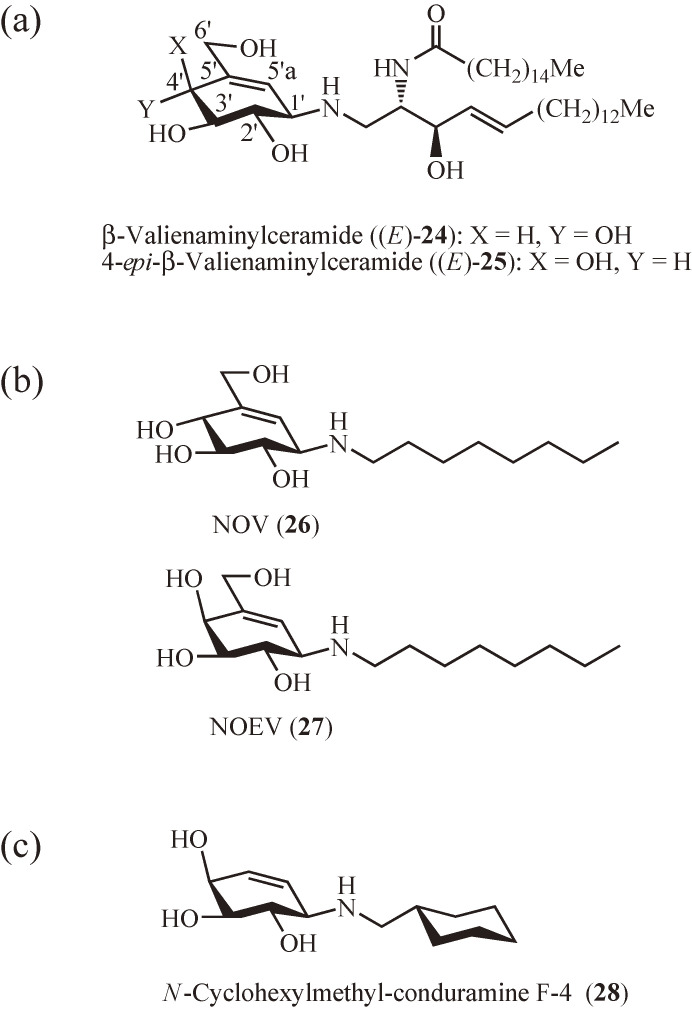

Figure 2.

Synthetic carbaglycosylamine-based transition-state analogue inhibitors of β-glycosidase. (a) Inhibitors of gluco- and galactocerebrosidases. (b) Inhibitors with chaperone activity. (c) Potential pharmacological chaperone for GM1-gangliosidosis.

During the course of the synthetic studies, the structure–activity relationships of 21 and (E)-24 were investigated and have led to the development of the potent glycosidase inhibitor N-alkyl-carbaglycosylamines including N-octyl-β-valienamine (NOV) (26)32) and its 4-epimer (NOEV) (27)33) (Fig. 2b). To facilitate the accessibility of N-alkyl-carbaglycosylamines, an improved and practical synthetic route to chiral carbaglycosylamines from myo-inositol (4) has been established.34) Both NOV (26) and NOEV (27) have later been found to possess chaperone activity for mutant forms of their target glycosidases. Since then, it has become of interest to develop carbaglycosylamine-based pharmacological chaperones for lysosomal glycosidases associated with lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs).35–37) Recently, the N-alkyl-conduramine F-4 derivatives have been identified as potential pharmacological chaperones for GM1-gangliosidosis, with the N-cyclohexylmethyl derivative 28 (Fig. 2c) being the most promising among them.38,39)

2. Total synthesis of N-linked carbaoligosaccharide α-amylase inhibitors

2.1. Preparation of validamine- and valienamine-derived carbaglycosyl acceptors and donors for the construction of N-linked carbaoligosaccharides.

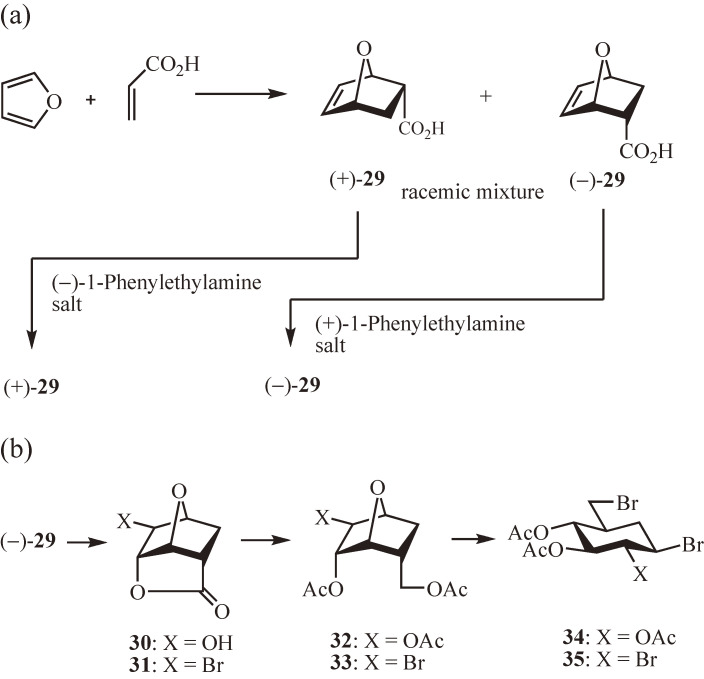

A practical preparative method for constructing N-linked carbaoligosaccharides is the ring opening of carbasugar acceptor epoxides with appropriate donor amines, and vice versa, as demonstrated in the total synthesis of antibiotic validamycins including 5 and 6.30) All the carbasugar derivatives used in the study can be prepared from a single starting compound, namely the Diels–Alder endo-adduct 29 of furan and acrylic acid (Fig. 3a),40) which is now obtainable in both chiral forms, (+)-29 and (−)-29, by chiral resolution of racemic 29 with (−)- and (+)-1-phenylethylamines, respectively41); thus, all the carbasugar derivatives described are available in both chiral forms. For the sake of simplicity, except noted otherwise, only the d-series of carbasugar derivatives derived from (−) 29 are shown in Figs. 3b and 4. The Diels–Alder adduct 29 was treated with hydrogen peroxide or bromine to give the lactones 30 or 31, respectively (Fig. 3b), both of which were converted into the corresponding 1,4-anhydro-5a-carba-α-glucopyranose derivatives 32 and 33 by reductive opening of the lactone ring with lithium aluminum hydride and subsequent acetylation.42) The anhydro rings of 32 and 33 were then cleaved with HBr/AcOH giving rise to the dibromocarbaglucose 34 and tribromocarbaglucose 35, respectively, which are versatile intermediates for the synthesis of various carbasugar derivatives including the validamine- and valienamine-derived acceptors and donors.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of carbasugars from Diels–Alder endo-adduct of furan and acrylic acid. (a) Diels–Alder reaction of furan and acrylic acid, and chiral resolution of the racemic endo-adduct. (b) Synthesis of di- and tribromo derivatives of carbaglucose as versatile intermediates of various carbasugars. The structural formulae shown correspond to the enantiomer derived from (−)-29.

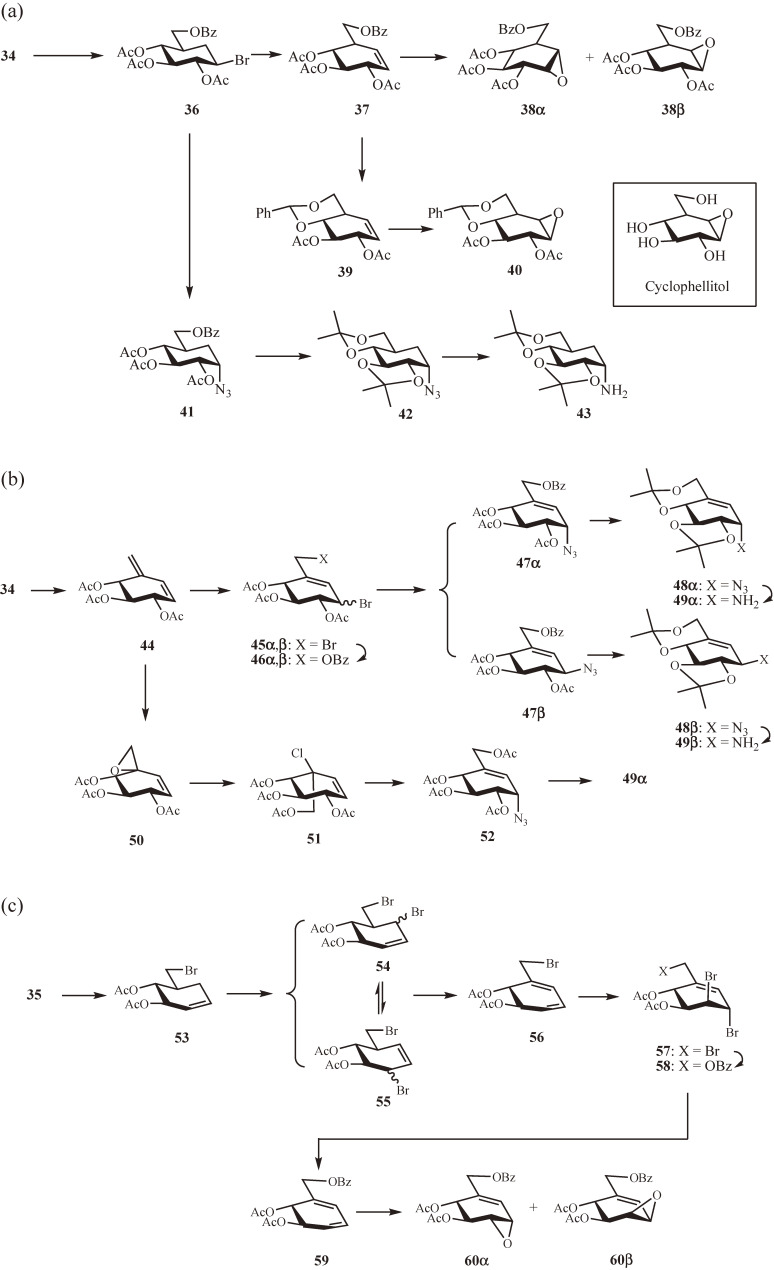

Figure 4.

Synthesis of validamine- and valienamine-derived acceptors and donors for the construction of N-linked carbaoligosaccharides. (a) Validamine-derived acceptor and donor from dibromocarbaglucose 34. Inset: Naturally occurring β-glucosidase inhibitor cyclophellitol. (b) Valienamine-derived donors from dibromocarbaglucose 34. (c) Valienamine-derived acceptors from tribromocarbaglucose 35.

The preparation of the validamine-derived acceptor and donor starts from 34 (Fig. 4a).43–46) Treatment of 34 with an excess of sodium benzoate resulted in benzoate for the primary bromide substitution (→ 36) and subsequent elimination of the secondary bromide giving rise to the cyclohexene 37. Because epoxidation of 37 with m-chloroperbenzoic acid (MCPBA) gave a mixture of nearly equal amounts of α- and β-epoxides 38α and 38β, the conformationally flexible 37 was first converted to the more rigid 39 by deacylation followed by benzylidenation and acetylation. The MCPBA epoxidation of 39 then proceeded stereoselectively yielding exclusively the acceptor β-epoxide 40. Notably, after our synthesis of 40, the strong β-glucosidase inhibitor cyclophellitol47) (Fig. 4a, inset), which is the deprotected form of 40, was discovered from the fermentation broth of Phellinus sp. When 34 was treated with an equivalent amount of sodium benzoate, the primary benzoate 36 was preferentially formed; subsequent SN2 substitution of the secondary bromide with an azide anion then yielded 41. After diacylation and di-O-isopropylidenation (→ 42), the azido group was reduced to give the protected validamine 43 as the donor amine.

The dibromocarbaglucose 34 is also the starting point for the preparation of the valienamine-derived donors (Fig. 4b).44,45) Dehydrobromination of 34 with 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) gave the crystalline conjugated alkene 44,43) which was reacted with an equivalent amount of bromine in CCl4 at −15 ℃ to provide the 1,4-addition products 45α and 45β in a ratio of 1:2; the ratio was reversed to 3:1 when the bromination was carried out at room temperature. Selective replacement of the primary bromide in 45α with benzoate was accompanied by the epimerization of the allylic secondary bromide yielding an inseparable mixture of 46α and 46β, azidation of which led to a separable 1:1.7 mixture of 47α and 47β. After deacylation and di-O-isopropylidenation, the resulting azides 48α and 48β were reduced with H2S or PPh3 to afford the protected valienamine 49α and β-valienamine 49β, respectively, as the donor amines. The efficient synthesis of 49α was later achieved from the spiro-epoxide 50 prepared by selective epoxidation of 44 with MCPBA48); thus, opening of the epoxide ring in 50 with hydrochloric acid and subsequent acetylation (→ 51) followed by SN2′ substitution with azide anion gave selectively the α-azide 52, which was then converted to 49α in a similar manner as 47α.

The valienamine-derived acceptors are prepared from the tribromocarbaglucose 35 (Fig. 4c).45) After vicinal debromination of 35 with zinc powder, the alkene 53 thus obtained was subjected to allylic bromination using a slight excess of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in CCl4, resulting in the formation of an equilibrium mixture of the allyl bromides 54 and 55 together with the cyclohexadiene 56 and the tribromocyclohexene 57. It seemed that both 54 and 55 tend to undergo dehydrobromination (→ 56) followed by addition of bromine generated in situ by the reaction of NBS and HBr (→ 57). Therefore, the reaction was carried out with an excess of NBS to convert 53 exclusively to 57. The primary bromide in 57 was then replaced with benzoate, and the resulting monobenzoate 58 was treated with zinc powder yielding the 1,3-cyclohexadiene 59. Regioselective epoxidation with MCPBA, followed by column chromatography separation, afforded 60α and 60β in a ratio of 1:1.5 as the valienamine-derived acceptor epoxides.

2.2. Synthesis of biologically active N-linked carbadisaccharide cores.

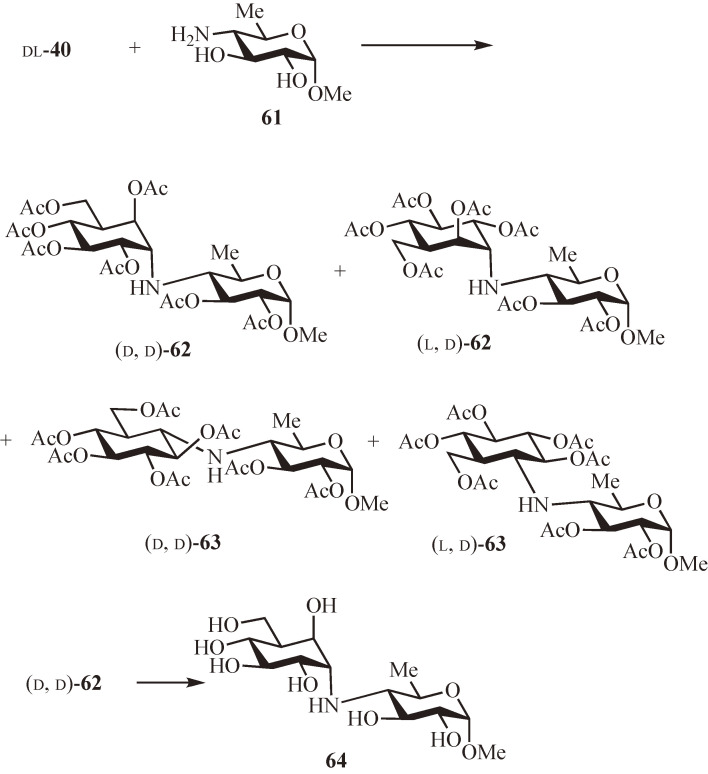

The first effort was made to construct oligobiosamine (23) (Fig. 5),49) which is the biologically active core of oligostatins (20) and contains hydroxyvalidamine (10). The coupling reaction of the validamine-derived acceptor epoxide 40 (racemic) and the donor amine, methyl 4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-α-d-glucopyranoside50) (61), was carried out in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ for 70 h. After de-O-benzylidenation followed by acetylation and column chromatography, all four products formed were isolated and their structures and absolute configurations were determined using 1H NMR analysis and specific rotations. As expected, the epoxide opening proceeded mainly in a trans-diaxial fashion to give a pair of diastereoisomers (d, d)-62 and (l, d)-62 in 30% yields together with the trans-diequatorial isomers (d, d)-63 and (l, d)-63 in 14% yield. The use of the chiral d-40 as the acceptor produced (d, d)-62 and the isomer (d, d)-63 in 34% and 16% yields, respectively. Deprotection of (d, d)-62 afforded the α-methyl glycoside of 23, methyl oligobiosaminide (64).

Figure 5.

Synthesis of methyl oligobiosaminide using a validamine-derived acceptor 40.

Two other active cores, acarviosin (21) and 6-hydroxyacarviosin (22), are composed of the valienamine (11) moiety. Therefore, a similar coupling reaction was investigated with the valienamine-derived acceptor 60β (Fig. 6a).45) When an equimolar mixture of 60β (racemic) and 61 was reacted in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ in a sealed tube, the ring opening occurred exclusively at the allylic position C-1 giving rise to the trans-diaxial products (d, d)-65 and (l, d)-65 which, after deprotection, yielded the α-methyl glycoside of the 2′-epimer of 21, methyl 2′-epiacarviosin (d, d)-66 (46%) and its diastereomer (l, d)-66 (31%), respectively.51) The attempted transformation of (d, d)-66 to 21 by inversion of the 2′-hydroxy group was unsuccessful due to the neighboring group participation of the nucleophilic imino group.

Figure 6.

Synthesis of N-linked carbadisaccharide cores composed of valienamine. (a) Attempted synthesis of methyl acarviosin using valienamine-derived acceptor 60β. (b) Synthesis of methyl 6-hydroxyacarviosin using valienamine-derived donor 49α. (c) Attempted synthesis of methyl acarviosin using valienamine-derived donor 49α.

Next, for the synthesis of 21 and 22, the protected valienamine 49α was used as the donor amine with the acceptor sugar epoxide, methyl 3,4-anhydro-α-d-galactopyranoside52) (67) (Fig. 6b).49) The reaction of equivalent amounts of 49α (racemic) and 67 in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ for 40 h afforded the desired pair of diastereomers (d, d)-68 and (l, d)-68 and their positional isomers (d, d)-69 and (l, d)-69 in 37% and 38% yield, respectively. This favorable result was rather unexpected because the formation of the desired pair involved the trans-diequatorial opening of the epoxide ring, which is generally less favorable than the trans-diaxial opening yielding the pair of the positional isomers. Deprotection of (d, d)-68 gave the α-methyl glycoside of 22, methyl 6-hydroxyacarviosin (70). A similar approach to prepare 21 using the 6-deoxy derivative of 67, methyl 3,4-anhydro-6-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranoside52) (71) (Fig. 6c)54) was, however, unsuccessful because of the exclusive formation of (d, d)-72 and (l, d)-72 by trans-diaxial opening of the epoxide ring.

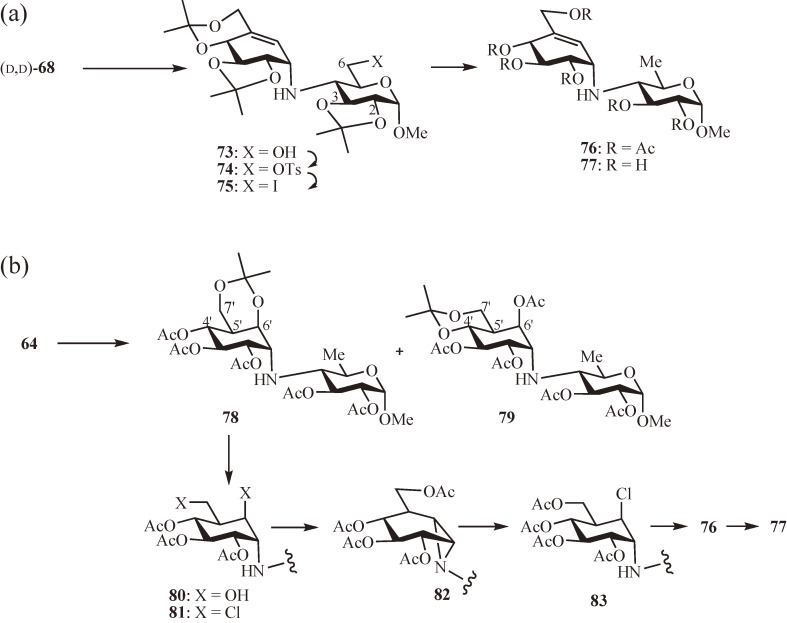

Two alternative routes to 21 were, therefore, investigated starting from other N-linked carbadisaccharide cores synthesized: (1) deoxygenation of the 6-hydroxy group of 70 (Fig. 7a)51) and (2) introduction of the C5′–C6′ double bond in 64 by dehydration of the 6′-hydroxy group (Fig. 7b).53,54) The first route began with the coupling product (d, d)-68. After protection of the 2- and 3-hydroxy groups by isopropylidenation (→ 73), the remaining 6-hydroxy group was converted to p-toluenesulfonate (→ 74) and replaced with iodide (→ 75). Without the protection of the 3-hydroxy group, the iodide for p-toluenesulfonate substitution led to the predominant formation of the 3,6-anhydro ring by intramolecular attack of the 3-hydroxy group. The iodide 75 was treated with lithium triethylborohydride followed by acetylation to give 76, which, after deacetylation, yielded the α-methyl glycoside of 21, methyl acarviosin (77). For the second route, selective protection of the 6′- and 7′-hydroxy groups in 64 was first carried out using an equivalent amount of 2,2-dimethoxypropane to yield, after acetylation, the desired 6′,7′- and the isomer 4′,7′-O-isopropylidene derivatives 78 and 79, respectively, in a ratio of 1:3. Removal of the isopropylidene group of 78 (→ 80) was followed by chlorination with sulfuryl chloride affording the dichloride 81. Because selective substitution of the primary chloride with acetate was accompanied by aziridine formation (→ 82), the chloro group was reinstalled at C6′ by opening of the aziridine ring with chloride (→ 83). The C5′–C6′ double bond was then introduced by treatment of 83 with DBU providing 76, which was deacetylated to give 77.

Figure 7.

Synthesis of methyl acarviosin. (a) From methyl 6-hydroxyacarviosin by deoxygenation of the 6-hydroxy group. (b) From methyl oligobiosaminide by dehydration of the 6′-hydroxy group.

2.3. Total synthesis of acarbose and related compounds.

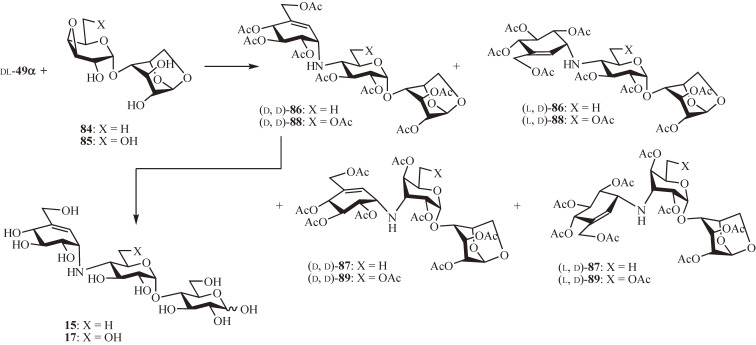

The total synthesis of N-linked carbatrisaccharide inhibitors, amylostatin-XG (15)55) and adiposin-1 (17),56) was first accomplished (Fig. 8). The coupling of the protected valienamine 49α (racemic) with 1,6-anhydro-4-O-(3′,4′-anhydro-6′-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranosyl)-d-glucopyranose (84), prepared from 1,6-anhydro-β-d-maltose,57) was carried out in a 1:8 mixture of N,N-dimethylformamide and propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ for 2.5 days. After de-O-isopropylidenation followed by acetylation, all diastereoisomers formed were isolated by column chromatography and characterized by the combination of 1H-NMR spectroscopy and specific rotation as a pair of trans-diequatorial products, (d, d)-86 (6.1%) and (l, d)-86 (5.7%), and a pair of trans-diaxial products, (d, d)-87 (24%) and (l, d)-87 (32%). Notably, as in the case with the acceptor 6-hydroxy epoxide 67, a similar coupling reaction of 49α (racemic) with the corresponding 6′-hydroxy derivative 85 facilitated the formation of the desired trans-diequatorial products affording (d, d)-88 (13%) and (l, d)-88 (14%) together with the trans-diaxial products (d, d)-89 (21%) and (l, d)-89 (16%). Both (d, d)-86 and (d, d)-88 were subjected to acetolysis with AcOH-Ac2O-H2SO4 (30:70:1) at room temperature and subsequent deacetylation with methanolic sodium methoxide to yield 15 and 17, respectively.

Figure 8.

Total synthesis of amylostatin-XG and adiposin-1.

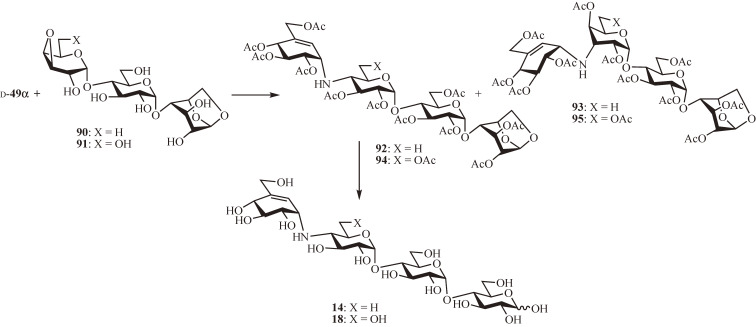

Next, the total synthesis of N-linked carbatetrasaccharide inhibitors, acarbose (14) and adiposin-2 (18), was achieved using the protected chiral valienamine d-49α (Fig. 9).58) The coupling reaction of d-49α with 1,6-anhydro-4′-O-(3″,4″-anhydro-6″-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranosyl)-β-d-maltose (90), prepared from 1,6-anhydro-β-d-maltotriose,59) in a 1:1 mixture of N,N-dimethylformamide and propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ for 3 days yielded, after de-O-isopropylidenation and acetylation, the trans-diequatorial and trans-diaxial products 92 and 93 in 19% and 30% isolated yields, respectively. Acetolysis followed by deacetylation converted 92 to 14. Once again, the reaction of d-49α with the corresponding 6″-hydroxy derivative 91 increased the yield of the trans-diequatorial product affording the desired 94 and the trans-diaxial product 95 in 33% and 21% isolated yields, respectively, of which 94 was converted to 18 by acetolysis and deacetylation. It is noteworthy that the role of the 6-hydroxy group in favoring the trans-diequatorial opening of the 3,4-anhydro ring, possibly through hydrogen bond formation to the epoxide oxygen, needs further investigation.

Figure 9.

Total synthesis of acarbose and adiposin-2.

Although the coupling reaction is not fully optimized, the successful synthesis of N-linked carbaoligosaccharides would allow for the development of novel N-linked carbaoligosaccharide glycosidase inhibitors.

2.4. Structure–activity relationship of methyl acarviosin.

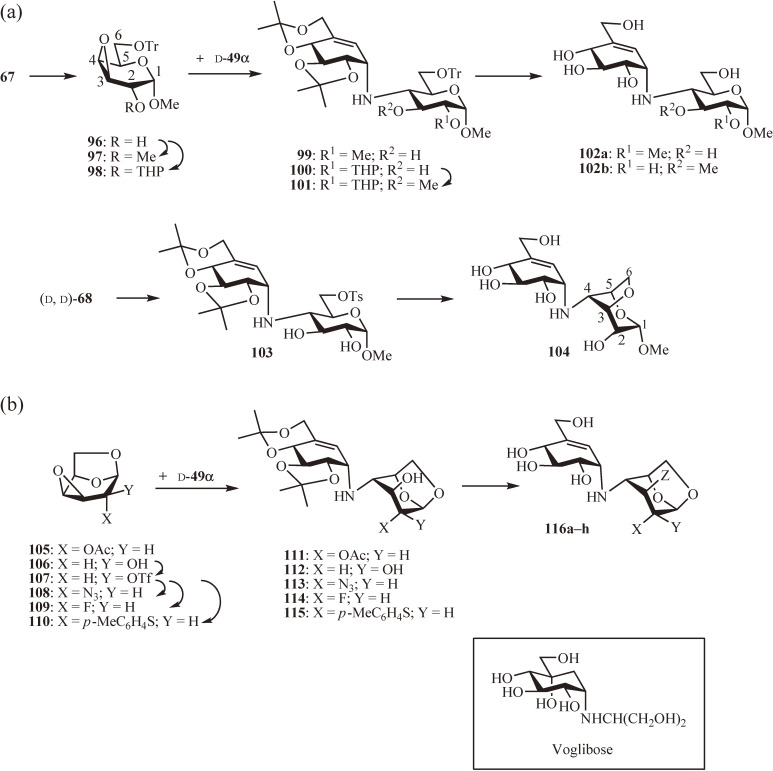

The valienamine moiety of methyl acarviosin (77), the active core of acarbose (14), is considered to mimic the oxocarbenium ion-like transition state of the α-amylase-catalyzed hydrolysis reaction. However, the role of the sugar moiety in the inhibitory activity was not clear. Therefore, the inhibitory activities of 77 and four related analogues with modified sugar moieties were compared against Baker’s yeast α-glucosidase; the analogues included methyl 6-hydroxyacarviosin (70) and its 2-O-methyl, 3-O-methyl, and 3,6-anhydro derivatives (102a, 102b, and 104, respectively) (Fig. 10 and Table 1a).60) For the synthesis of the monomethyl derivatives 102a and 102b, the epoxide 67 was first converted to either its 2-O-methyl or 2-O-tetrahydropyranyl derivative (97 and 98, respectively) after protection of the 6-hydroxy group as a trityl ether (→ 96). The coupling of d-49α with 97 in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ yielded 99, which, after removal of the trityl and isopropylidene groups, gave 102a. A similar coupling of d-49α with 98 (→ 100) followed by 3-O-methylation (→ 101) and deprotection provided 102b. The 3,6-anhydro derivative 104 was prepared from (d, d)-68 by treatment of its 6-O-tosyl derivative 103 with sodium methoxide followed by deprotection.

Figure 10.

Chemical modification of 6-hydroxyacarviosin. (a) Synthesis of 2-O-methyl, 3-O-methyl, and 3,6-anhydo derivatives. (b) Synthesis of 1,6-anhydro and its 2-azido, amino, acetamido, fluoro, and epi derivatives. Inset: Potent α-glucosidase inhibitor voglibose.

Table 1.

Chemical modification of methyl acarviosin. (a) α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of several anhydro, deoxy, and O-methyl derivatives. (b) α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of several 1,4-anhydro derivatives 116a–h.

| (a) | |

|---|---|

| Compd | Inhibitory activity |

| (IC50, µM) α-Glucosidase (Baker’s yeast) | |

| 70 | 0.98 |

| 77 | 0.38 |

| 102a | 1.25 |

| b | 0.75 |

| 104 | 1.45 |

| (b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | Inhibitory activity | |||

| (IC50, µM) α-Glucosidase (Baker’s yeast) | ||||

|

| ||||

| X | Y | Z | ||

| 116a | OH | H | OH | 0.10 |

| b | N3 | H | OH | 0.29 |

| c | NH2 | H | OH | 2.2 |

| d | NHAc | H | OH | 33 |

| e | F | H | OH | 0.18 |

| f | H | OH | OH | 0.50 |

| g | H | H | OH | 0.032 |

| h | H | H | H | 0.030 |

All four analogues were found to be slightly less active than 77 but were still potent inhibitors. Surprisingly, changing the conformation of the sugar moiety from 4C1 to 1C4 by 3,6-anhydro formation did not have any significant detrimental effect on the activity.

To gain further insight into the structural requirement of the sugar moiety, the 1,6-anhydride of 6-hydroxyacarviosin (22), namely 116a, and its several derivatives 116b–h were synthesized (Fig. 10b) and their inhibitory activities were compared with that of 77 (Table 1b).61,62) The 1,6-anhydride 116a and its 2-epimer 116f were synthesized by coupling of d-49α with 2-O-acetyl-1,6:3,4-dianhydro-β-d-galacto-63) (105) and 1,6:3,4-dianhydro-β-d-talopyranoses63) (106), respectively, in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ and subsequent deprotection of the corresponding products 111 and 112. The 2-azido and 2-fluoro derivatives of 116a (116b and 116e, respectively) were synthesized similarly by coupling of d-49α with the 2-azido and 2-fluoro derivatives of 105 (108 and 109, respectively), prepared by trifluoromesylaton of 106 (→ 107) and SN2 displacement of trifluoromesylate 107 by either azide or fluoride, and subsequent deprotection of the resulting 113 and 114, respectively. The reduction of 113 and deprotection afforded the 2-amino derivative 116c, whereas the reduction followed by N-acetylation and deprotection yielded the 2-acetamido derivative 116d. The mono- and dideoxy derivatives (116g and 116h, respectively) were synthesized by coupling of d-49α with the 2-thioether 110, prepared by SN2 displacement of the 2-trifluoromesylate in 107 by p-toluenethiolate, and subsequent desulfurization of the product 115 with Raney-nickel followed by deprotection. The ratio of the two products 116g and 116h was 1.4:1; the dideoxy derivative 116h was presumed to be formed through the intermediate episulfide.

As in the case of the 3,6-anhydro derivative 104, the 1C4 conformation of the 1,6-anhydro sugar moiety did not have any negative effect on the inhibitory activity. The 1,6-anhydride 116a, its 2-epimer 116f, and its 2-azido and 2-fluoro derivatives (116b and 116e, respectively) showed similar activities to 77, but the 2-amino derivative 116c and, particularly, the 2-acetamide derivative 116d were significantly less active. The most interesting finding was the increased activity of the deoxy derivatives: both mono- and dideoxy-derivatives (116g and 116h, respectively) were nearly 10 times more active than 77.

The X-ray crystallographic analysis of the acarbose (14) and glucoamylase complex was later published by Aleshin et al.,64) revealing: (1) an extensive hydrogen bond network between the valienamine moiety and the surrounding amino acids; (2) a salt bridge between the imino linkage and the putative catalytic Glu; and (3) the hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic faces of the sugar moieties and the Tyr/Trp at the binding site. The strong interaction of the valienamine moiety with the enzyme active site probably contributes to the potent activity of the synthetic analogues of 77 except 116c and 116d. The poor activity of these two analogues may be attributed to the disruption of the salt bridge interaction by the amino/acetamido group being 1,3-diaxially oriented to the imino linkage. The hydrophobic amino acids present in the sugar binding site may also explain the higher activity of the deoxy analogues 116g and 116h than 77. These results seemed to clearly suggest that the sugar moiety of 77 may be replaced by simple alkyl groups without impairing the inhibitory potency. Kameda et al.65) reported similar findings based on their semi-synthetic studies on valienamine-containing α-glycosidase inhibitors, in which several N-alkyl and N-aralkyl valienamines were synthesized from valienamine (11) prepared by microbial degradation of validamycin A (5), and the findings were used to guide the development of voglibose66) (Fig. 10b, inset), which is an N-substituted derivative of valiolamine (12) and a practical alternative to 14 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

3. Synthesis of novel carbaglycosylamine-based β-glycosidase inhibitors

Several valienamine-type carbaglycosylamine derivatives available in our laboratory were exploited to develop new transition-state analogue inhibitors of β-glycosidases.

3.1. Methyl 1′-epi-acarviosin and methyl 1′-epi-6-hydroxyacarviosin.

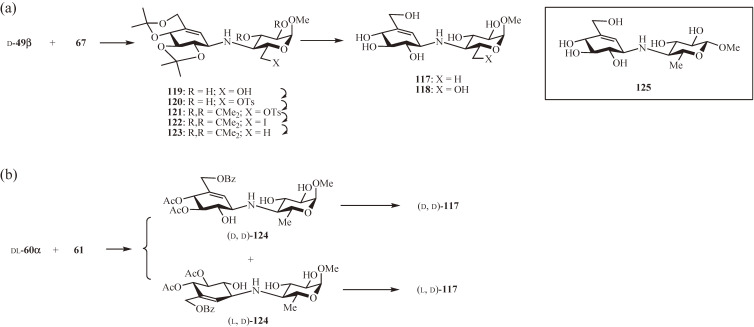

By analogy with methyl acarviosin (77) and methyl 6-hydroxyacarviosin (70), it was assumed that methyl 1′-epi-acarviosin (117) and 1′-epi-6-hydroxyacarvosin (118) (Fig. 11) with cellobiose-like structures might be potential transition-state analogue inhibitors of β-glucosidase.51) Both 117 and 118 were, therefore, synthesized similarly to 77 and 70, respectively, except that the protected β-valienamine 49β was used instead of the α-valienamine 49α (Fig. 11a). Coupling of d-49β with 67 yielded the desired 119 (55%). Which, after deprotection, provided 118. For the synthesis of 117, the 6-hydroxy group of the coupling product 119 was removed by a sequence of reactions involving selective 6-O-tosylation (→ 120), 2,3-O-isopropylidenation (→ 121), iodide-for-tosylate substitution (→ 122), and deiodination (→ 123). The 6-deoxy derivative 123 thus obtained was deprotected to give 117. The valienamine-derived epoxide 60α was also found to be effective for the straightforward synthesis of 117 (Fig. 11b).49) Treatment of 60α (racemic) with the amine 61 in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ in a sealed tube led to the opening of the epoxide exclusively at allylic C-1 yielding trans-diequatorial products (d, d)-124 and (l, d)-124, which, after deprotection, provided (d, d)-117 (25%) and its diastereoisomer (l, d)-117 (16%), respectively.

Figure 11.

Synthesis of N-linked carbadisaccharides composed of β-valienamine. (a) Synthesis of methyl 1′-epi-acarviosin and 1′-epi-6-hydroxyacarviosin using valienamine-derived donor 49β. Inset: β-Methyl glycoside analogue of methyl-1′-epi-acarviosin. (b) Straightforward synthesis of 1′-epi-acarviosin using valienamine-derived acceptor 60α.

The inhibitory activity of 117 and 118 were tested against three glycosidases: yeast α-glucosidase, almond β-glucosidase, and jack bean α-mannosidase (Table 2). Contrary to expectation, both 117 and 118 were found to be poor inhibitors of β-glucosidase but modest inhibitors of α-glucosidase and α-mannosidase. Of note, Stick and co-workers67,68) later synthesized the β-methyl glycoside analogue 125 of 117 (Fig. 11a, inset), and reported it to be a potent inhibitor of A. niger β-glucosidase but a weak inhibitor of C. saccharolyticum β-glucosidase. It seems that the substrate specificity differs widely even within a class of enzymes; hence, caution needs to be taken when evaluating the inhibition results.

Table 2.

Inhibitory activity of methyl 1′-epi-acarviosin 117 and methyl 1′-epi-6-hydroxyacarviosin 118

| Compound | Inhibition: I (%) at 1000 µg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| α-Glucosidase (yeast) | β-Glucosidase (almonds) | α-Mannosidase (Jack beans) | |

| 117 | 72 | 33 | 80 |

| 118 | 80 | ∼0 | 86 |

3.2. Synthesis of β-valienaminylceramide and 4-epi-β-valienaminylceramide.

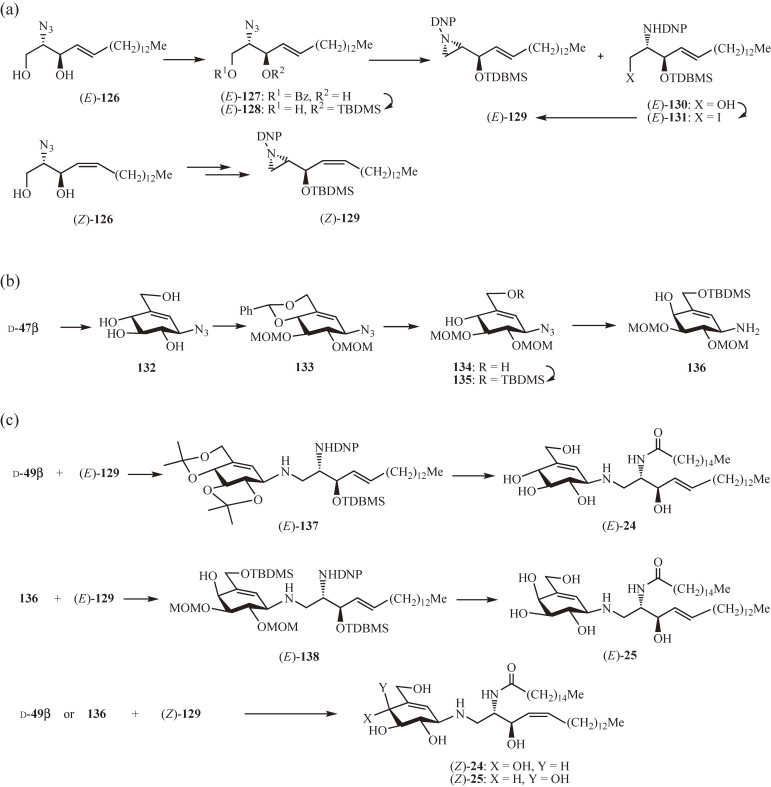

Glucocerebrosidase and galactocerebrosidase are the lysosomal β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase, respectively, and involved in glycolipid metabolism through hydrolysis of glucosyl- and galactosylceramide, respectively. It was reasoned that replacing the carbohydrate moiety of glucosylceramide and galactosylceramide with an appropriate valienamine derivative may provide a transition-state analogue inhibitor of the respective glycosylceramidase.31) The ring opening of sphingosine-derived aziridines with proper carbaglycosylamines was found to be effective for the synthesis of N-carbaglycosylceramides. The protected aziridine (E)-129 was prepared from the known azidosphingosine (E)-12669–71) in three steps (Fig. 12a): (1) selective benzoylation of the primary hydroxy group (→ (E)-127); (2) protection of the residual hydroxy group as a tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether followed by debenzoylation (→ (E)-128); and (3) aziridine formation by reduction of the azide with triphenylphosphine and subsequent protection of the aziridine with a 2,4-dinitrophenyl group (→ (E)-129). The aziridine product (E)-129 was formed in 39% yield together with the amino alcohol (E)-130 (45%), which was readily converted to (E)-129 (86%) by iodination (→ 131) followed by reductive cyclization. The isomer (Z)-129 was similarly prepared from the (Z)-126.

Figure 12.

Synthesis of potent gluco- and galactocerebrosidase inhibitors. (a) Synthesis of sphingosine-derived aziridine and its Z-isomer. (b) Synthesis of 4-epi-β-valienamine donor. (c) Synthesis of β-valienaminylceramide and 4-epi-β-valienaminylceramide.

The 4-epi-β-valienamine donor 136 was prepared from the precursor of the β-valienamine donor d-47β (Fig. 12b) by epimerization of the 4-hydroxy group, after a series of protecting group manipulations including deisopropylidenation (→ 132), benzylidenation and subsequent methoxymethylation (→ 133), and debenzylidenation followed by selective protection of the primary hydroxy group with tetrabutyldimethyl-silyl ether (→ 134 → 135). Epimerization at the 4 position was then achieved by oxidation of the 4 hydroxy group of 135 with pyridinium chlorochlomate, followed by reduction with diisopropylaluminum hydride, which also reduced the azido group, to give 136.

The coupling reaction of d-49β with (E)-129 was carried out in propan-2-ol at 120 ℃ for 5 d (Fig. 12c) to afford the protected β-valienaminylsphingosine (E)-137 (60%), which, after selective N-deprotection followed by N-palmitoylation and deprotection, yielded β-valienaminylceramide (E)-24 (44%). Likewise, the coupling of 136 with (E)-129 (→ (E)-138; 55%) followed by the same sequence of reactions gave the isomer (E)-25 (49%). The Z-isomers (Z)-24 and (Z)-25 were similarly prepared in 27% and 22% overall yields, respectively, using the aziridine (Z)-129.

Their inhibitory activities were tested against mouse liver glucocerebrosidase and galactocerebrosidase (Table 3). As expected, (E)-24 and (E)-25 were potent and selective inhibitors of glucocerebrosidase and galactocerebrosidase, respectively. Notably, their isomers (Z)-24 and (Z)-25 were also found to be potent and selective inhibitors. Both glucocerebrosidase and galactocerebrosidase appear to have a rather broad specificity for the ceramide moiety.

Table 3.

Inhibitory activity of carbaglycosylceramides

| Compound | Inhibition at 10 µM (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| β-Glucocerebrosidase (mouse liver) | β-Galactocerebrosidase (mouse liver) | |

| (E)-24 | 95.2 (0.3)* | 19.4 |

| (Z)-24 | 97.7 (0.1) | 28.6 |

| (E)-25 | 6.7 | 90.3 (2.7) |

| (Z)-25 | 9.6 | 78.4 (4.5) |

*Number in parentheses denotes IC50 (µM) values.

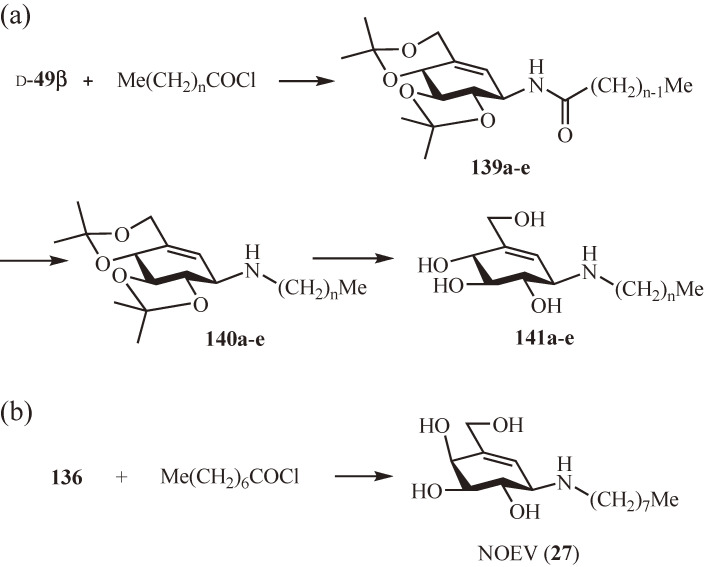

3.3. N-Octyl-β-valienamine and N-octyl-4-epi-β-valienamine.

The above findings suggested that the ceramide moiety of (E)-24 and (E)-25 can be replaced by simple alkyl chains without compromising their activities. Thus, several N-alkyl derivatives of β-valienamine were first prepared by N-acylation of the protected β-valienamine d-49β with n-alkanoyl chlorides (→ 139a–e) followed by lithium aluminum hydride reduction (→ 140a–e) and deprotection (→ 141a–e) (Fig. 13a) and evaluated for their inhibitory activity against mouse liver glucocerebrosidase (Table 4a).32) All the N-alkyl derivatives, except for the shortest alkyl chain derivative 141a, showed similar or better activity than (E)-24. The potency seemed to depend on the length of the N-alkyl chain: the potency increased rapidly from C4 (141a) to C6 (141b) and to C8 (26) and then decreased gradually for C10 (141c), C14 (141d) and C18 (141e). The most potent C8 derivative, NOV (26), exhibited 10-fold greater activity than (E)-24. Accordingly, the C8 derivative of 4-epi-β-valienamine, NOEV (27), was similarly synthesized from the protected 4-epi-β-valienamine 136 and n-octanoyl chloride (Fig. 13b) and tested for its inhibitory activity against mouse liver galactocerebrosidase as well as bovine liver β-galactosidase (Table 4b).33) Of note, NOEV (27) was found to be only a moderate inhibitor of galactocerebrosidase but rather a potent inhibitor of β-galactosidase. Moreover, it was later discovered that NOEV is a potent inhibitor of human lysosomal β-galactosidase responsible for the hydrolysis of the terminal β-galactose residue from GM1-ganglioside.35)

Figure 13.

Synthesis of N-alkyl derivatives of β-valienamine and 4-epi-β-valienamine.

Table 4.

Inhibitory activity of N-alkyl derivatives of β-valienamine and 4-epi-β-valienamine. (a) Inhibitory activity of N-octyl-β-valienamine (NOV) and its N-alkyl homologues. (b) Inhibitory activity of N-octyl-4-epi-β-valienamine (NOEV).

| (a) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | Inhibitory activity (IC50, µM) β-Glucocerebrosidase (mouse liver) | |

| 26 (NOV) | n = 7 | 0.03 |

| 141a | n = 3 | 10 |

| b | n = 5 | 0.3 |

| c | n = 9 | 0.07 |

| d | n = 13 | 0.12 |

| e | n = 17 | 0.3 |

| (b) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | Inhibitory activity (IC50, µM) | |

|

| ||

| β-Galactocerebrosidase (mouse liver) | β-Galactosidase (bovine liver) | |

| 27 (NOEV) | 5.0 | 0.87 |

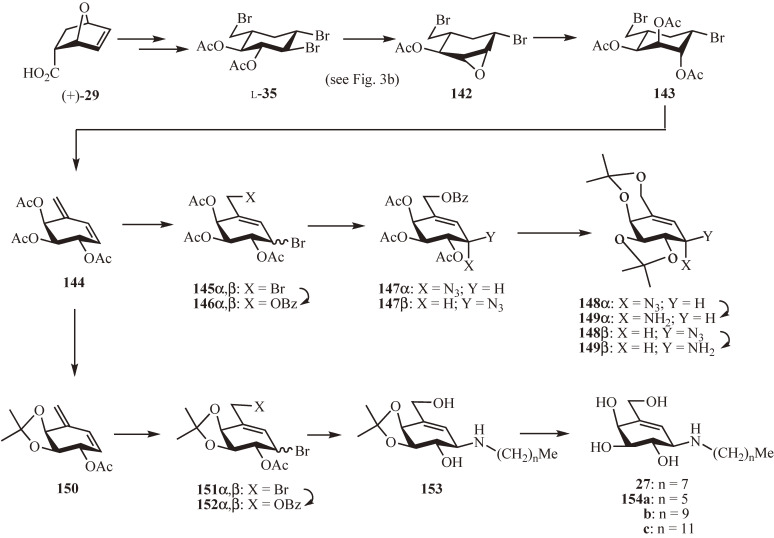

The potent β-galactosidase inhibitory activity of (E)-25 and NOEV (27) spawned an increased interest in the N-substituted 4-epi-β-valienamine and, therefore, a more straightforward synthesis of a suitable 4-epi-β-valienamine donor has been developed starting from the tribromocarbaglucose l-35 derived from the Diels–Alder adduct (+)-29 (Fig. 14).37,72,73) Treatment of 35 with sodium methoxide gave after acetylation the epoxide 142, which was subjected to acid hydrolysis followed by acetylation providing the dibromocarbaaltrose 143. Following the same sequence of reactions described for the preparation of the valienamine-donors 49α,β from 45α,β (Fig. 4b), the carbaaltrose derivative 143 was converted to the 4-epi-β-valienamine donor 149β and its α-isomer 149α via the conjugated alkene 144, the 1,4-conjugate addition products 145α,β, the primary benzoates 146α,β, the allyl azides 147α and 147β (at a ratio of ca. 1:1; 50%), and the di-O-isopropylidene derivatives 148α and 148β. Furthermore, after protecting group manipulation of 144 (deacetylation followed by isopropylidenation and acetylation), the resulting 150 was similarly converted to a mixture of the allyl bromides 151α,β and then to a mixture of 152α,β, which then reacted with alkylamines, providing selectively β-amine 153.73) The alkylamination of 152β likely proceeded via a cyclic acetoxonium ion.71) After deprotection, NOEV (27) and 154a–c thus obtained were evaluated for their inhibitory activity (Table 5). Both N-decyl and N-dodecyl derivatives (154b and 154c, respectively) were found to be more potent β-galactosidase inhibitor than NOEV (27). Notably, the most potent inhibitor 154c was also a potent inhibitor of β-glucosidase.

Figure 14.

Straightforward synthesis of 4-epi-β-valienamine donor.

Table 5.

Inhibitory activity of NOEV (27) and its N-alkyl homologues against three glycosidases

| Compd | Inhibitory activity (IC50, µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| α-Galactosidase (green coffee beans) | β-Galactosidase (bovine liver) | β-Glucosidase (almonds) | |

| 27: n = 7 | 3.1 | 0.87 | 3.1 |

| 154a: n = 5 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| b: n = 9 | 1.9 | 0.13 | 2.5 |

| c: n = 11 | 4.4 | 0.01 | 0.87 |

4. Development of carbaglycosylamine-based pharmacological chaperones for lysosomal storage disorders

4.1. Lysosomal storage disorders and pharmacological chaperones.

Lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) are a group of rare genetic diseases, most of which are caused by mutations in genes encoding lysosomal hydrolases.74,75) The mutations produce misfolded hydrolases that are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and degraded by ER-associated degradation. As a result, lysosomes are deficient in hydrolases, resulting in the progressive accumulation of undegraded substrates and ultimately generalized cell and tissue dysfunction.

Pharmacological chaperone therapy76) is an emerging approach to treat LSDs using small-molecule ligands that specifically bind and stabilize mutant enzymes, thereby facilitating proper folding and thus improving lysosomal trafficking and activities.77,78) Pharmacological chaperone therapy is particularly advantageous for the treatment of LSDs affecting the central nervous system, because of the potential of small-molecule ligands to cross the blood–brain barrier. As such, reversible competitive inhibitors are obvious candidates for the development of specific pharmacological chaperones. In 1999 the imino sugar 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin (migalastat), an α-galactosidase inhibitor, was shown to function as a pharmacological chaperone for Fabry disease, which is caused by a deficiency in α-galactosidase A activity and subsequent accumulation of the substrate globotriosylceramide.79) Its hydrochloride has been approved for the oral treatment of some variants of Fabry disease in several countries including the European Union, U.S.A., and Japan.80)

4.2. Discovery of chaperone activities of NOV and NOEV.

Gaucher disease and GM1-gangliosidosis are LSDs caused by deficiencies of lysosomal glucocerebrosidase and β-galactosidase, respectively, and characterized by the intracellular accumulation of the corresponding substrates, glucosylceramide and GM1-ganglioside.81) The selective inhibitors of these enzymes are potential candidates for the development of specific pharmacological chaperones: the glucocerebrosidase inhibitor NOV (26) (see Fig. 2b) for Gaucher disease and the human β-galactosidase inhibitor NOEV (27) (see Fig. 2b) for GM1-gangliosidosis.

The increased activity of the mutant enzyme due to the addition of 26, namely chaperone activity of 26, was evaluated in fibroblasts expressing F213I mutant glucocerebrosidase, which is a common mutation in patients with Gaucher disease in Japan (Table 6a).82,83) After incubation with 30 µM 26, the maximum enhancement of enzyme activity (∼6-fold compared to without 26) was observed together with lysosomal localization of the mutant enzyme and intracellular clearance of the substrate glucosylceramide.82) This finding was rather surprising, considering that the IC50 of 26 for wild-type human glucocerebrosidase was found to be 3 µM. Of note, a similar enhancement of activity was reproduced by 3 µM of the hydrochloride of 26 probably due to its increased water solubility.83) In addition to the F213I mutant, the hydrochloride of 26 (3 and 30 µM) was effective against other mutant glucocerebrosidases, including N188S, G202R, and N370S (each ∼2-fold in an ex vivo enzyme assay), but not against the D409H and L444P mutants.

Table 6.

Inhibitory and chaperone activity of NOV (26) and NOEV (27). (a) Activity of 26 against wild-type and mutant human β-glucosidase. (b) Activity of 27 against wild-type and mutant human β-galactosidase.

| (a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | IC50 (µM) against wild type | Enhanced activity (fold) of mutant with 26 (30 µM) or 26 HCl (3 and 30 µM) | |

| 26 | 3 | F213I | 6 |

| 26 HCl | 0.502 | F213I, N188S, G202R, N370S | ∼2 |

| (b) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | IC50 (µM) against wild type | Enhanced activity (fold) of mutants with 27 (0.2 µM) | |

| 27 | 0.2 | R201C | 5.1 |

| R201H | 4.5 | ||

| R457Q | 2.4 | ||

| W273L | 2.2 | ||

| Y83H | 2.0 | ||

The potent human β-galactosidase inhibitor 27 (IC50 = 0.2 µM) was evaluated for its chaperone activity in fibroblasts expressing R201C mutant β-galactosidase causing juvenile GM1-gangliosidosis (Table 6b).35) Incubation with 0.2 µM 27 resulted in the maximum enzyme activity (5.1-fold compared to without 27) as well as intracellular reduction of the substrate GM1-ganglioside. The enhancement of activity was also observed in fibroblasts expressing other mutant β-galactosidases including R201H (4.5-fold), R457Q (2.4-fold), W273L (2.2-fold), and Y83H (2.0-fold). An animal study was also performed using GM1-gangliosidosis model mice expressing human R201C mutant β-galactosidase. The oral administration of 27 enhanced the mutant enzyme activity and decreased GM1-ganglioside levels in neuronal cells in the brain.

Computational analysis of the interaction of 2684) and 2785) with their target enzymes indicated that their binding free energies were higher at pH 5 (lysosome) than at pH 7 (ER) because of the reduced number of hydrogen bonds caused by protonation of functional residues in the enzyme active site. Thus, both 26 and 27 bind to the respective mutant enzymes stabilizing them in the ER and dissociate from them thus restoring their activity in the lysosome, which is consistent with the observed chaperone activity of 26 and 27.

4.3. Practical synthesis of NOV and NOEV from quercitols.

The initial synthesis of NOV (26) and NOEV (27) began with chiral resolution of the racemic Diels–Alder adduct of furan and acrylic acid 29 into (−)-29 by crystallization with (+)-1-phenylethylamine (Fig. 3a), which is rather cumbersome and time-consuming and, moreover, is not atom-economical because the other enantiomer (+)-29 is not used. In order to facilitate the advancement of carbaglycosylamine-based glycosidase inhibitors as well as pharmacological chaperones, a more practical synthesis from readily available chiral compounds was investigated.

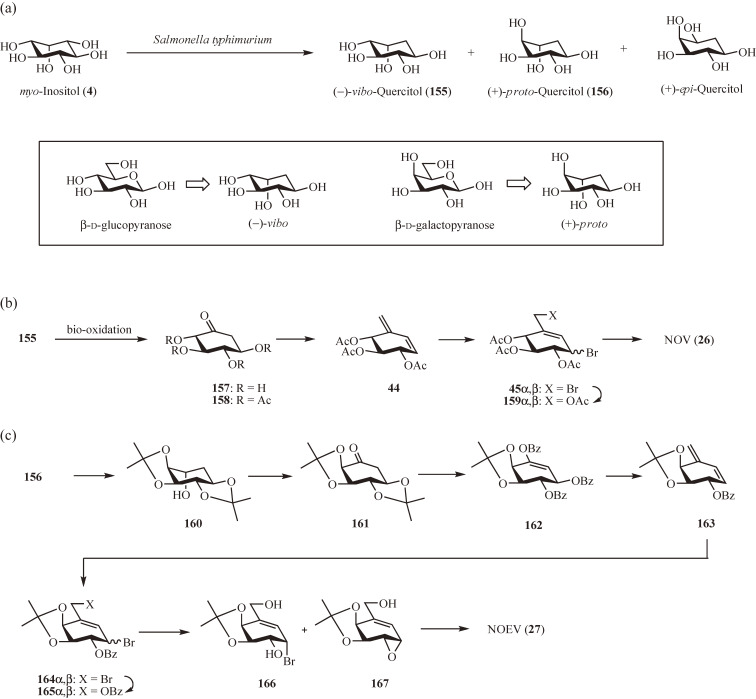

Quercitol (deoxyinositol) has ten diastereoisomers: four meso and six chiral, of which (−)-vibo- (155), (+)-proto- (156) and (−)-proto-quercitols are found in nature.86) In 1999, Takahashi et al.87) reported the production of 155, 156, and (+)-epi-quercitol by fermentation of myo-inositol (4) with Salmonella typhimurium: after fermentation, the three quercitols were isolated and purified by ion-exchange column chromatography and recrystallization providing 155, 156, and (+)-epi-quercitol in 35%, 5%, and 11% yields, respectively (Fig. 15a). Taking advantage of the close resemblance of the absolute configuration of the hydroxy groups between 155 and β-d-glucopyranose and between 156 and β-d-galactopyranose (Fig. 15a, inset), in addition to their ready availability, 155 and 156 were chosen as the chiral starting materials for the practical synthesis of 2688) and 27,89) respectively.

Figure 15.

Practical synthesis of N-octyl-β-valienamine (NOV) from (−)-vibo-quercitol and 4-epi-β-valienamine (NOEV) from (+)-proto-quercitol. (a) Bacterial conversion of myo-inositol to (−)-vibo-quercitol, (+)-proto-quercitol and (+)-epi-quercitol. Inset: Structural similarity between (−)-vibo-quercitol and β-d-glucopyranose and between (+)-proto-quercitol and β-d-galactopyranose. (b) Synthesis of NOV from (−)-vibo-quercitol. (c) Synthesis of NOEV from (+)-proto-quercitol.

The first step in the practical synthesis of 26 from 155 involves selective oxidation of the axial hydroxy group in 155, which was achieved by means of bio-oxidation (Fig. 15b).88) Thus, an aqueous solution of 155 was incubated with Gluconobacter sp. at ambient temperature for 1 day to give, after purification by cation- and anion-exchange chromatography, (−)-2-deoxy-scyllo-inosose (157)90) in practically quantitative yield. Subsequent acetylation of 157 in acidic conditions was accompanied by β-elimination yielding the α,β-unsaturated ketone 158 in 83% yield. exo-Methylenation was then carried out using acidic Nysted reagent to afford the conjugated alkene 44 but in lower yield (25%). Due to the base sensitivity of 158, conventional Wittig olefination was not applicable. From this point, the synthesis was able to follow the initial synthesis of 26: 44 → 49 (Fig. 4b) and 49 → 26 (Fig. 13a). Here, a more straightforward approach73) was used: after 1,4-dibromination of 44 to 45α,β, the primary bromide was replaced with acetate and the resulting mixture of allyl bromides 159α,β was reacted with n-octylamine yielding 26 as a sole product in 31% yield. The reaction of 159β likely proceeded via a cyclic acetoxonium ion.

For the practical synthesis of 27 from 156, isopropylidenation of 156 was first carried out to give the diisopropylidene derivative 160 (Fig. 15c).89) The residual hydroxy group was subsequently oxidized with SO3·Py/DMSO in the presence of Et3N to provide the ketone 161 in 53% yield from 156. After selective removal of the trans-O-isopropylidene group using slightly acidic conditions, benzoylation with benzoyl chloride afforded the enol ester 162 in 60% yield. Using the Wittig reaction conditions, 162 was successfully converted into the conjugated alkene 163 in 66% yield, probably through the following sequence of reactions: (1) debenzoylation of the enol ester by phosphorous ylide; (2) E1cB elimination of the β-benzoyloxy group forming the α,β-unsaturated ketone; and (3) reaction of the α,β-unsaturated ketone with the phosphorous ylide. Bromination of 163 with a slight excess of bromine (→ 164α,β) followed by selective substitution of the primary bromide with benzoate gave a 1.7:1 mixture of the α- and β-bromides 165α,β in 91% yield. Debenzoylation of the mixture in basic conditions led to the formation of the α-bromide 166 and the α-epoxide 167 in 47% and 26% yield, respectively. Because the subsequent coupling reaction of 166 and 167 with n-octylamine yielded the same product,89) the mixture of 166 and 167, without isolation, was treated with n-octylamine followed by deisopropylidenation to give 27 as the sole product in 47% yield.

Recently, Li et al.91) reported an efficient synthesis of 26 and 27 from naturally abundant shikimic acid with overall yields of 31% (14 steps) and 19% (17 steps), respectively.

4.4. N-Alkylconduramine F-4 derivatives as potential pharmacological chaperones for GM1-gangliosidosis.

NOV (26) and NOEV (27) have shown promising chaperone activity, yet their potent inhibitory activity might be counterproductive. Therefore, special considerations are necessary to maximize the stabilizing effect and to minimize the inhibitory activity. Mena-Barragán et al.92) have devised sp2-iminosugar inhibitors bearing pH-sensitive hydrophobic tails by incorporating an orthoester linker; thus, they are strong inhibitors of human glucocerebrosidase or α-galactosidase at pH 7 (in the ER) but become non/less-inhibitory at pH 5 (in the lysosome) due to the loss of the hydrophobic tails, which are necessary for the inhibitory activity, by hydrolysis of the acid-labile orthoester linker.

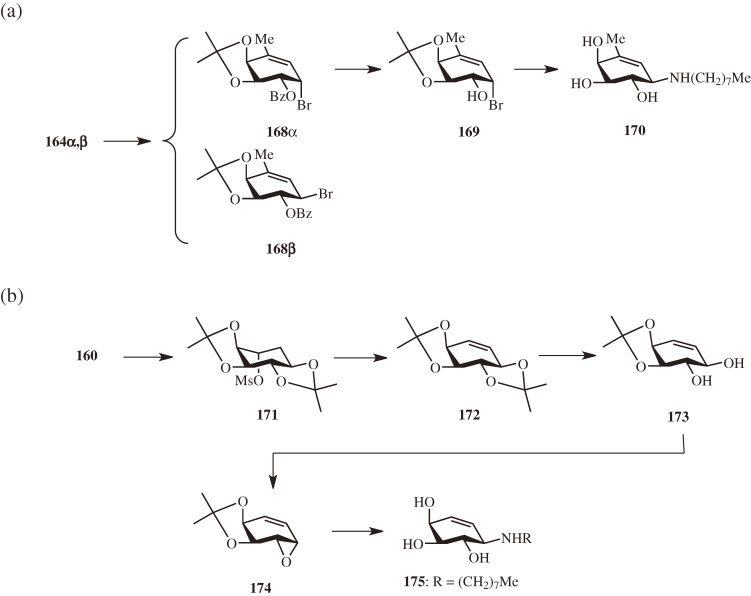

Suzuki et al.93) reported a comparative crystallographic analysis of human β-galactosidase in complex with 27 and sp2-iminosugar-type inhibitors, revealing the major interactions of 27 with the enzyme: (1) the hydrogen bond interactions involving the 2-, 3- and 4-hydroxy groups are crucial for the specific binding to the enzyme; (2) the salt bridge between the exocyclic nitrogen and the catalytic Glu is also crucial for the binding and specificity; and (3) the hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions involving the 6-hydroxy and n-octyl groups, respectively, are important for the stabilization of the complex. Based on these findings, in order to reduce the inhibitory activity of 27 while maintaining a certain affinity to the enzyme for the chaperone activity, modification of the interactions that stabilize the complex appeared to be a rational approach. Therefore, the 6-deoxy and dehydroxymethyl derivatives of 27 (170 and 175, respectively) were first prepared to eliminate the hydrogen bond interaction involving the 6-hydroxy group.

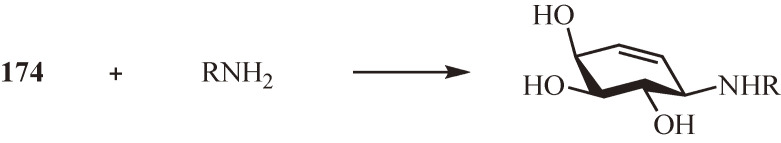

The 6-deoxy derivative 170 was synthesized from a mixture of the 1,4-dibromides 164α,β (Fig. 16a).89) Selective reduction of the primary bromide with NaBH4 yielded the mono bromides 168α and 168β in 68% and 23% yields, respectively. The α-bromide 168α was then debenzoylated to give 169 (51%), which was subjected to SN2 replacement of the α-bromide by n-octylamine and subsequent de-O-isopropylidenation to afford 170 in 90% yield. The dehydroxymethyl derivative 175, on the other hand, was synthesized from the di-O-isopropylidene derivative 160 (Fig. 16b).38) Mesylation of the hydroxy group (→ 171) followed by E2 elimination of the mesylate using DBU furnished the cyclohexenetetrol (known as conduritol F) derivative 172 in 76% yield. After selective removal of the trans-O-isopropylidene group with weak acid, the diol 173 thus obtained was treated with either Martin sulfurane or Mitsunobu reagent to give the α-epoxide 174 as the sole product in 69% and 59% yields, respectively. The epoxide ring opening with n-octylamine proceeded regio- and stereo-selectively to yield, after acidic removal of the isoproprylidene group, the hydrochloride of 175 (N-octyl-conduramine F-4) quantitatively.

Figure 16.

Synthesis of 6-deoxy and 5-dehydroxymethyl derivatives of N-octyl-4-epi-β-valienamine (NOEV). (a) Synthesis of N-octyl-6-deoxy-4-epi-β-valienamine. (b) Synthesis of N-octyl-conduramine F-4.

The hydrochlorides of 27, 170, and 175 were evaluated for their inhibitory activity against human wild-type β-galactosidase, and their chaperone activity was assessed using fibroblasts expressing R201C mutant β-galactosidase (Table 7).38) Both 170, and 175 indeed showed much lower inhibitory activity than 27; the IC50 values of 170 and 175 were 27- and 71-fold higher than that of 27, respectively. The higher IC50 values of 175 than 170 may be attributed to the 5-methyl group in 170, which might be involved in a hydrophobic interaction with the enzyme. Notably, the chaperone activities of 170 and 175 were slightly higher than that of 27.

Table 7.

Inhibitory and chaperone activity of 6-deoxy and 5-dehydroxymethyl derivatives of NOEV (170 and 175, respectively) against wild-type and mutant human β-galactosidase

| Compd | IC50 (µM) against wild type | Enhanced activity (fold) of the R201C mutant with 27 170, and 175 |

|---|---|---|

| 27 HCl | 1.7 | 3.6 |

| 170 HCl | 46 | 5.2 |

| 175 HCl | 120 | 5.4 |

Next, several N-alkyl derivatives of conduramine F-4 were prepared similarly to the N-octyl derivative 175 using the corresponding alkylamines (Table 8).38) Because the strength of hydrophobic interactions depends on the size and shape of the hydrophobic molecules, different types of alkylamines were selected including various linear and branched amines.

Table 8.

Inhibitory and chaperone activity of various N-alkyl conduramine F-4 against wild-type and mutant human β-galactosidase

| R | IC50 (µM) against wild type | Enhanced activity (fold) of the R201C mutant with N-alkyl-conduramine F-4 derivatives (20 µM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | n-Butyl | 50 | 2.0 |

| n-Pentyl | 19 | 4.0 | |

| n-Hexyl | 56 | 4.6 | |

| n-Octyl (175) | 120 | 5.4 | |

| n-Decyl | 43 | 1.6 | |

| (b) | (CH2)3OH | >1000 | 0.9 |

| CHEt2 | >1000 | 1.2 | |

| Cy | 490 | 1.4 | |

| (c) | CH2CHEt2 (176) | 15 | 7.4 |

| CH2Cy (28) | 60 | 8.5 | |

| CH2CHMe2 | 41 | 4.6 | |

| CH2Ph | 180 | 1.5 | |

| (CH2)2CHMe2 | 28 | 4.6 | |

| (CH2)2Ph | 86 | 4.2 | |

Linear alkyl groups shorter or longer than C8 led to slightly more active inhibitors than 175; meanwhile, the chaperone activity increased gradually with the length of the alkyl chain up to C8 (Table 8a). It should be noted that the C10 derivative showed high cytotoxicity to fibroblasts at 20 µM, probably due to its cationic surfactant character; therefore, linear alkyl groups longer than C10 were not investigated.

The binding affinity was significantly impaired when the linear alkyl group was replaced by either hydroxypropyl, 1-ethylpropyl, or cyclohexyl group (Table 8b). The hydrophilic hydroxypropyl group obviously did not form the hydrophobic interaction necessary for binding. On the other hand, both the 1-ethylpropyl and cyclohexyl groups are attached to the nitrogen atom through their secondary carbons; thus, they create more steric hindrance around the nitrogen, which may interfere with the formation of the salt bridge between the NH and the catalytic Glu. Indeed, reduction of the steric hindrance by insertion of a CH2 group between the nitrogen and the secondary carbon, namely the N-2-ethylbutyl and N-cyclohexylmethyl derivatives 176 and 28, respectively, restored the binding affinity (Table 8c). Of note, replacement of the terminal 3-pentyl group in 176 with an isopropyl group and the terminal cyclohexyl group in 28 with a phenyl group resulted in weaker inhibitory and chaperone activities, which were improved to some degree by insertion of an additional CH2 group.

Among the N-alkyl derivatives synthesized, the N-cyclohexylmethyl-conduramine F-4 (28) showed the best activity profile for a potential pharmacological chaperone with moderate inhibitory activity (IC50 = 60 µM) and the highest chaperone activity (8.5-fold activity enhancement). In addition, the N-2-ethylbutyl derivative 176 had the second-best activity profile with IC50 of 15 µM and 7.4-fold activity enhancement. Further in vivo studies will be needed to confirm the promising chaperone activity of 28 as well as 176.

5. Prospects

It is now well appreciated that carbohydrates are involved in cellular communication and interaction essential for physiological and pathological events. Despite the important role carbohydrates play, the molecular basis of carbohydrate-mediated recognition processes remains poorly understood. This is in part caused by their structural complexity and diversity, but it is also because their structures are, unlike those of nucleic acids and proteins, generated in a non-template driven manner by various glycosyltransferases and glycosidases. In this context, carbohydrate mimetics that selectively interfere with these carbohydrate-processing enzymes as well as carbohydrate-binding proteins are useful as molecular probes to understand the structure–function relationships of carbohydrates. Among the carbohydrate mimetics, carbasugars and their derivatives are of immense value because of their ability to mimic the oxocarbenium ion-like transition state of glycosidase-catalyzed hydrolysis in addition to the substrates of glycosyltransferases and the ligands of carbohydrate-binding proteins.

In the course of the total synthesis of naturally occurring N-linked carbaoligosaccharides, including the amylase inhibitor acarbose and related compounds, a general strategy has been established to link carbasugars to carbohydrates via an imino linkage by epoxide ring opening of either carbasugar epoxides with amino carbohydrates or carbohydrate epoxides with carbaglycosylamines. In addition, the synthesis of chiral carbasugars has been substantially improved with the ready availability of quercitols through the bioconversion of myo-inositol in conjunction with the well-established carbasugar synthesis from the Diels–Alder endo-adducts of furan and acrylic acid. This practical approach greatly facilitates the availability of carbasugars and their derivatives of interest, including carbaglycosylamines and N-linked carbaoligosaccharides, for their applications in glycobiology.

Several carbohydrate-processing enzymes and carbohydrate-binding proteins have been recognized as potential targets for therapeutic interventions. Therefore, carbasugars and their derivatives are also useful for the development of therapeutics against these targets. We were pleased to find the chaperone activity of the carbaglycosylamine-based transition-state analogue inhibitors NOV and NOEV; moreover, chemical modification of NOEV has led to the identification of N-cyclohexylmethyl-conduramine F-4 as a potential pharmacological chaperone for GM1-gangliosidosis related human lysosomal β-galactosidase.

Given their ready availability through synthesis, carbasugars and their derivatives now hold great promise for applications in glycobiology and therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

Our synthetic journey towards carbaglycosylamine glycosidase inhibitors described in this review would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of students as well as the valuable suggestions of colleagues and collaborators, whose names appear on the cited references. SO is particularly grateful to have had such outstanding students in his laboratory at Keio University.

When we started our synthetic journey, we had no idea it would lead to the development of potential pharmacological chaperones. The outcome of research is indeed unpredictable, but for this reason research is interesting and worth conducting. It is important to focus and execute your research with care and confidence and see what it leads to. Enjoy your journey!

Biographies

Profile

Seiichiro Ogawa was born in Tokyo in 1937. He graduated from the Department of Applied Chemistry at the Faculty of Engineering of Keio University in 1961 and received a Ph.D. from the same university in 1967. His Ph.D. research concerned the synthesis of the aminocyclitol units of aminocyclitol antibiotics. He then worked as a research fellow with Professor Kenneth L. Rinehart, Jr., at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (1967–1968) and extended his Ph.D. work to develop a practical synthesis of 14C-labeled 2-deoxystreptamine, which helped to elucidate the biosynthesis of neomycins. He was also an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Fellow with Professor Frieder W. Lichtenthaler at Technische Hochschule Darmstadt (1973–1974), where he studied the synthetic potential of the sugar enolones in the preparation of various sugar derivatives. He was appointed as an Associate Professor in 1973 and promoted to a Full Professor in 1984 at Keio University. Upon his retirement in 2003, he became an Emeritus Professor. Throughout his career, his research has focused on the synthesis of biologically active cyclitol compounds and has contributed to the development of carbasugar derivatives of biochemical and biomedical importance.

Shinichi Kuno was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1976. He graduated from International Christian University with a Bachelor of Liberal Arts in 2006 and then from the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo with a Master of Science in 2008. His master’s thesis was on mass analysis of sialyl glycosides and development of a chemical probe for identifying natural product-protein interactions. He subsequently joined an agrochemical and industrial chemical company, Hokko Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., and is working on several projects, including the design and synthesis of pharmacological chaperones. In 2012, he entered the Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology at Tokyo Institute of Technology as a working student to study the phosphorescence of organic crystals and received his Ph.D. in Science in 2017. In 2021, he moved to Hokko Chemical America Corporation in the U.S.A. as general manager. His research interest focuses on organic compounds with bioactive or photoactive properties.

Tatsushi Toyokuni, a retired professor from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), received his Ph.D. in chemistry in 1982 from Keio University under the supervision of Professor Tetsuo Suami and Professor Seiichiro Ogawa, working toward the total synthesis of validamycin A. He subsequently undertook postdoctoral research with Professor Kenneth L. Rinehart, Jr., at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he studied the biosynthesis of validamycins identifying that the validamine and valienamine units are derived from the pentose phosphate pathway. In 1987, he was recruited to the Biomembrane Institute, Seattle, WA, as Head of the Organic Chemistry Department and Affiliated Associate Professor of Chemistry at the University of Washington, and led the institute’s chemistry projects to help understand the relationship between the cell membrane and the cause of diseases, including the development of fully synthetic vaccines based on tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens, the development of anti-cell adhesion molecules based on cell-surface carbohydrates, and the synthesis of sphingosine derivatives to study the role of sphingolipids in cell signaling. Following the closure of the institute in 1996, he joined the faculty of the Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, UCLA School of Medicine. There, in addition to his continued interest in synthetic glycobiology, his research focused on the design and synthesis of novel radiopharmaceuticals (F-18 labelled and Cu-64 labelled compounds) for positron emission tomography imaging in collaboration with the Nuclear Medicine faculty.

References

- 1).Umezawa S. (1974) Structures and syntheses of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 30, 111–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Suami T., Ogawa S., Umezawa S. (1963) Studies on antibiotics and related substances. XVII. Syntheses of trans-2-aminocyclohexyl-d-glucosaminides. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 36, 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- 3).Suami T., Lichtenthaler F.W., Ogawa S. (1966) Aminocyclitols. VIII. A synthesis of inosamines and inosadiamines. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 39, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 4).Ogawa S., Abe T., Sano H., Kotera K., Suami T. (1967) Aminocyclitols. XIV. The synthesis of streptamine and actinamine. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 40, 2405–2409. [Google Scholar]

- 5).Suami T., Lichtenthaler F.W., Ogawa S., Nakashima Y., Sano H. (1968) Aminocyclitls. XVII. A facile synthesis of 2-deoxystreptamine. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 41, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 6).Ogawa S., Rinehart K.L., Jr., Kimura G., Johnson R.P. (1974) Chemistry of the neomycins. XIII. Synthesis of aminocyclitols and aminosugars via nitromethane condensations. J. Org. Chem. 39, 812–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Rinehart, K.L., Jr. and Schimbor, R.F. (1967) Neomycins. In Antibiotics. II. Biosynthesis (eds. Gottlieb, D. and Shaw, P.D.). Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- 8).Rinehart K.L., Jr., Stroshane R.M. (1976) Biosynthesis of aminocyclitol antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 29, 319–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Shier W.T., Rinehart K.L., Jr., Gottlieb D. (1969) Preparation of four new antibiotics from a mutant of Streptomyces fradiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 63, 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Shier W.T., Ogawa S., Hichens M., Rinehart K.L., Jr. (1973) Chemistry and biochemistry of the neomycins. XVII. Bioconversion of aminocyclitols to aminocyclitol antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 26, 551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Ogawa S., Oki S., Suami T. (1979) Inositol derivatives. 11. Synthesis of dianhydroinositols. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 52, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 12).Ogawa S., Takagaki T. (1987) Conversion of β-senepoxide to crotepoxide. Total synthesis of (+)-crotepoxide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 60, 800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 13).Iwasa T., Yamamoto H., Shibata M. (1970) Studies on validamycins, new antibiotics. I. Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. limoneus nov. var., validamycin producing organism. J. Antibiot. 23, 595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Iwasa T., Higashide E., Yamamoto H., Shibata M. (1971) Studies on validamycins, new antibiotics II. Production and biological properties of validamycins A and B. J. Antibiot. 24, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Iwasa T., Kameda Y., Asai M., Horii S., Mizuno K. (1971) Studies on validamycins, new antibiotics. IV. Isolation and characterization of validamycins A and B. J. Antibiot. 24, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Horii S., Iwasa T., Mizuta E., Kameda Y. (1971) Studies on validamycins, new antibiotics. VI. Validamine, hydroxyvalidamine and validatol, new cyclitols. J. Antibiot. 24, 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Kameda Y., Horii S. (1972) The unsaturated cyclitol part of the new antibiotic, the validamycins. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 746–747. [Google Scholar]

- 18).Suami T., Ogawa S. (1990) Chemistry of carba-sugars (pseudo-sugars) and their derivatives. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 48, 21–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Kameda Y., Asano N., Yoshikawa M., Takeuchi M., Yamaguchi T., Matsui K., et al. (1984) Valiolamine a new α-glucosidase inhibiting aminocyclitol produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J. Antibiot. 37, 1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).McCasland G.E., Furuta S., Durham L.J. (1966) Alicyclic carbohydrates. XXIX. The synthesis of a pseudo-hexose (2,3,4,5-tetrahydroxycyclohexanemethanol). J. Org. Chem. 31, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 21).McCasland G.E., Furuta S., Durham L.J. (1968) Alicyclic carbohydrates. XXXII. Synthesis of pseudo-β-dl-gulopyranose from a diacetoxybutadiene. Proton magnetic resonance studies. J. Org. Chem. 33, 2835–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).McCasland G.E., Furuta S., Durham L.J. (1968) Alicyclic carbohydrates. XXXIII. Epimerization of pseudo-α-dl-talopyranose to pseudo-α-dl-galactopyranose. Proton magnetic resonance studies. J. Org. Chem. 33, 2841–2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Schmidt D.D., Frommer W., Junge B., Müller L., Wingender W., Truscheit E., et al. (1977) α-Glucosidase inhibitors. New complex oligosaccharides of microbial origin. Naturwissenschaften 64, 535–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Truscheit E., Frommer W., Junge B., Müller L., Schmidt D.D., Wingender W. (1981) Chemistry and biochemistry of microbial α-glucosidase inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 20, 744–761. [Google Scholar]

- 25).Campbell L.K., White J.R., Campbell R.K. (1996) Acarbose: its role in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Ann. Pharmacother. 30, 1255–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Fukuhara K., Murai H., Murao S. (1982) Amylostatins, other amylase inhibitors produced by Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. Amylostatics No. 2476. Agric. Biol. Chem. 46, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar]

- 27).Namiki S., Kangouri K., Nagate T., Hara H., Sugita K., Omura S. (1982) Studies on the α-glucoside hydrolase inhibitor, adiposin. I. Isolation and physicochemical properties. J. Antibiot. 35, 1234–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Watanabe K., Furumai T., Sudoh M., Yokose K., Maruyama H.B. (1984) New α-amylase inhibitor, trestatins. IV. Taxonomy of the producing strains and fermentation of trestatin A. J. Antibiot. 37, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Omoto S., Itoh J., Ogino H., Iwamatsu K., Nishizawa N., Inouye S. (1981) Oligostatins, new antibiotics with amylase inhibitory activity. II. Structures of oligostatins C, D, and E. J. Antibiot. 34, 1429–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Ogawa, S., Toyokuni, T. and Miyamoto, Y. (2019) Synthesis of N-linked carbaoligosaccharides: total synthesis of antibiotic validamycins and related compounds. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Vol. 60 (ed. Rhaman, A.). Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 123–155. [Google Scholar]

- 31).Tsunoda H., Inokuchi J., Yamagishi K., Ogawa S. (1995) Pseudosugars, 35. Synthesis of glucosylceramide analogs composed of imino-linked unsaturated 5a-carbaglycosyl residues: potent and specific gluco- and galactocerebrosidase Inhibitors. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1995, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 32).Ogawa S., Ashiura M., Uchida C., Watanabe S., Yamazaki C., Yamagishi K., et al. (1996) Synthesis of potent β-d-glucocerebrosidase inhibitors: N-alkyl-β-valienamines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 6, 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- 33).Ogawa S., Kobayashi Matsunaga Y., Suzuki Y. (2002) Chemical modification of the β-glucocerebrosidase inhibitor N-octyl-β-valienamine: synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-epimeric and 4-O-(β-d-galactopyranosyl) derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 1967–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Ogawa S., Kanto M. (2007) Synthesis of valiolamine and some precursors for bioactive carbaglycosylamines from (−)-vibo-quercitol by biogenesis of myo-inositol. J. Nat. Prod. 70, 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Matsuda J., Suzuki O., Oshima A., Yamamoto Y., Noguchi A., Takimoto K., et al. (2003) Chemical chaperone therapy for brain pathology in GM1-gangliosidosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15912–15917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Ogawa S. (2004) Design and synthesis of carba-sugars of biological interest. Trends Glycosci. Glyc. 16, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- 37).Ogawa S., Kanto M., Suzuki Y. (2007) Development and medical application of unsaturated carbaglycosylamine glycosidase inhibitors. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 7, 679–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Kuno S., Higaki K., Takahashi A., Nanba E., Ogawa S. (2015) Potent chemical chaperone compounds for GM1-gangliosidosis: N-substituted (+)-conduramine F-4 derivatives. MedChemComm 6, 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- 39).Kuno S., Ogawa S. (2016) From quercitols to biologically active valienamine and conduramine derivatives: development of pharmacological chaperones. Trends Glycosci. Glyc. 28, E13–E22. [Google Scholar]

- 40).Suami T., Ogawa S., Nakamoto K., Kasahara I. (1977) Synthesis of penta-N,O-acetyl-dl-validamine. Carbohydr. Res. 58, 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Ogawa S., Iwasawa Y., Nose T., Suami T., Ohba S., Ito M., et al. (1985) Total synthesis of (+)-(1,2,3/4,5)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydroxycyclohexane-1-methanol and (+)-(1,3/2,4,5,)-5-amino-2,3,4-trihydroxycyclohexane-1-methanol [(+)-validamine]. X-ray crystal structure of (3S)-(+)-2-exo-bromo-4,8-dioxatricyclo[4.2.1.03,7]nonan-5-one. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 903–906. [Google Scholar]

- 42).Ogawa S., Nakamoto K., Takahara M., Tanno Y., Chida N., Suami T. (1979) Pseudo-sugars. 4. A facile synthesis of dl-validamine and its derivative. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 52, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 43).Ogawa S., Toyokuni T., Omata M., Chida N., Suami T. (1980) Pseudo-sugars. 5. Synthesis of dl-validatol and dl-deoxyvalidatol, and their epimers. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 53, 455–457. [Google Scholar]

- 44).Toyokuni T., Abe Y., Ogawa S., Suami T. (1983) Synthetic studies on the validamycins. III. Bromination of dl-tri-O-acetyl-(1,3/2)-4-methylene-5-cyclohexene-1,2,3-triol. Preparation of several branched-chain unsaturated cyclitols related to valienamine. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 56, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- 45).Ogawa S., Toyokuni T., Ara M., Suetsugu M., Suami T. (1983) Synthesis and epoxidation of trans-5,6-diacetoxy-1-benzoyloxymethyl-1,3-cyclohexadiene. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 56, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar]

- 46).Ogawa S., Chida N., Suami T. (1983) Synthetic studies on the validamycins. 5. Synthesis of dl-hydroxyvalidamine and dl-valienamine. J. Org. Chem. 48, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar]

- 47).Atsumi S., Umezawa K., Iinuma H., Naganawa H., Nakamura H., Iitaka Y., et al. (1990) Production, isolation, and structure determination of a novel β-glucosidase inhibitor, cyclophellitol from Phellinus sp. J. Antibiot. 43, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Toyokuni T., Ogawa S., Suami T. (1983) Synthetic studies on the validamycins. IV. Synthesis of dl-valienamine and related branched-chain unsaturated amincyclitols. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 56, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 49).Ogawa S., Iwasawa Y., Toyokuni T., Suami T. (1985) Synthesis of a core structure of the antibiotic oligostatin. Carbohydr. Res. 144, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 50).Stevens C.L., Blumbergs P., Daniher F.A., Otterbach D.H., Taylor K.G. (1966) Synthesis and chemistry of 4-amino-4,6-dideoxy sugars. II. Glucose. J. Org. Chem. 31, 2822–2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Ogawa S., Yasuda K., Takagaki T., Iwasawa Y., Suami T. (1985) Synthesis of some analogues of methyl dehydro-oligobiosaminide (acarviosin). Carbohydr. Res. 141, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- 52).Buchanan J.G. (1958) The behavior of derivatives of 3:4-anhydrogalactose towards acidic reagents. Part II. J. Chem. Soc. 2511–2516. [Google Scholar]

- 53).Ogawa S., Uchida C., Shibata Y. (1992) Alternative synthesis and enzyme inhibitory activity of methyl 1′-epiacarviosin and its 6-hydroxy analog. Carbohydr. Res. 223, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Shibata Y., Ogawa S., Suami T. (1990) Synthesis of methyl hexa-O-acethylacarviosin and the 6-acetoxy analogue. Carbohydr. Res. 200, 486–492. [Google Scholar]

- 55).Ogawa S., Sugizaki H., Iwasawa Y., Suami T. (1985) Synthesis of amylostatin-XG. Carbohydr. Res. 140, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 56).Ogawa S., Iwasawa Y., Toyokuni T., Suami T. (1985) Synthesis of adiposin-1 and related compounds. Carbohydr. Res. 141, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 57).Mori M., Haga M., Tejima S. (1975) Synthesis of 4-O-α-d-galactopyranosyl-d-glucopyranose and 4-O-(6-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranosyl)-d-glucopyranose by chemical modifications of maltose. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 23, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 58).Ogawa S., Shibata Y. (1988) Total synthesis of acarbose and adiposin-2. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 605–606. [Google Scholar]

- 59).Takeo K., Mine K., Kuge T. (1976) Synthesis of methyl α- and β-maltotriosides and aryl β-maltotriosides. Carbohydr. Res. 48, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 60).Shibata Y., Kosuge Y., Mizukoshi T., Ogawa S. (1992) Chemical modification of the sugar part of methyl acarviosin: synthesis and inhibitory activities of nine analogues. Carbohydr. Res. 228, 377–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Ogawa S., Shibata Y., Kosuge Y., Yasuda K., Mizukoshi T., Uchida C. (1990) Synthesis of potent α-glucosidase inhibitors: methyl acarviosin analogue composed of 1,6-anhydro-β-d-glucopyranose residue. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1387–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 62).Ogawa S., Aso D. (1993) Chemical modification of the sugar moiety of methyl acarviosin: synthesis and inhibitory activity of eight analogues containing a 1,6-anhydro bridge. Carbohydr. Res. 250, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 63).Pacák J., Podešva J., Točík Z., Černý M. (1972) Syntheses with anhydo sugars. XI. Preparation of 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose and 2,4-dideoxy-2,4-difluoro-d-glucose. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 37, 2598–2599. [Google Scholar]

- 64).Aleshin A.E., Firsov L.M., Honzatko R.B. (1994) Refined structure for the complex of acarbose with glucoamylase from Aspergillus awamori var. X100 to 2.4-A resolution. J. Biochem. 269, 15631–15639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65).Kameda Y., Asano N., Yoshikawa N., Matsui K., Horii S., Fukase H. (1982) N-Substituted valienamine, α-glucosidase inhibitors. J. Antibiot. 35, 1624–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66).Horii S., Fukase H., Matsuo T., Kameda Y., Asano N., Matsui K. (1986) Synthesis and α-d-glucosidase inhibitory activity of N-substituted valiolamine derivatives as potential oral antidiabetic agents. J. Med. Chem. 29, 1038–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67).McAuliffe J.C., Stick R.V., Tilbrook M.G., Watts A.G. (1998) The synthesis of a diastereoisomer of methyl acarviosin. Aust. J. Chem. 51, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 68).Tilbrook D.M.G., Stick R.V., Williams S.J. (1999) β-Acarbose. VIII. The synthesis of some N-linked carba-oligosaccharides. Aust. J. Chem. 52, 895–904. [Google Scholar]

- 69).Kiso M., Nakamura A., Tomita Y., Hasegawa A. (1986) A novel route to d-erythro-sphingosine and related compounds from mono-O-isopropylidene-d-xylose or d-galactose. Carbohydr. Res. 158, 101–111. [Google Scholar]