Abstract

Introduction/Objective:

This review aimed to summarize articles describing caregiver burden and the relationship between health outcomes as well as describing interventions focusing on this population.

Methods:

The review used the PRISMA statement and Whittemore and Knafl guidelines. The search engines Scopus, PubMed, Ovid (PsycINFO), and CINAHL were searched for articles published in English.

Results:

This review included 30 studies that met the criteria. Physical, psychological, and social factors were associated with HF caregiver burden. HF caregiver interventions included health education, post-discharge home visits, phone calls, counseling, and support groups that demonstrated some potential to reduce the caregivers’ burden.

Discussion:

Healthcare provider team should screen for caregiver burden and promote healthy behaviors, and strategies to improve quality of life. Further studies should include caregivers as care team members and embed social networking in the interventions for reducing HF caregiver burden. The caregivers’ burden could influence the poor outcomes of care, including physical, psychological, societal, and functional dimensions. Future interventions should develop to alleviate HF caregiver burden.

Keywords: heart failure, caregivers, caregiver burden, chronic illness, systematic review

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a condition in which the heart cannot supply enough blood to meet the metabolic demands of vital organs.1,2 In the United States, roughly 5.7 million people live with HF and 870 000 new cases are diagnosed annually.3,4 Patients with HF mostly suffer the burden of symptom exacerbation (eg, dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, depression, edema, and fluid overload), which often results in poor health outcomes including decreased quality of life (QOL), increased rehospitalization, and mortality.5,6 The limitations due to HF cause people to be more dependent on others and maintaining cardiac function can be helped with medication management, symptom recognition, and adhering to diet and exercise regimens from others. 7

Caregivers play a significant role in patients with HF as they support symptom management, self-care, and decision-making, particularly in regard to the transition from the hospital to home. 8 A lack of caregiver’s support has been associated with increased rehospitalizations and mortality. 9 While caregiver support has been shown to improve a patient’s health, assuming the role of a surrogate and advocate for patients with HF may cause a burden on the caregiver. Caregiver burden is defined as “The extent to which caregivers perceive that caregiving has had an adverse effect on their emotional, social, financial, physical, and spiritual functioning.” 10 The outcome of caregiver burden is the multidimensional impact of caregiver burden caused by an imbalance between caregivers’ demand and their ability to cope with demands, which is similar across caregivers of chronic conditions such as dementia, cancer, diabetes.11 -14 For instance, caregivers’ reported burdens have consisted of physical, psychological, and lifestyle issues such as insomnia and fatigue, 15 depressive symptoms and anxiety, 9 limited social life, and changed roles. 15

Several literature reviews have examined caregiver burden in patients with HF; however, previous studies focused on caregivers’ individual perceptions of physical and psychological burden.16,17 However, there was limited knowledge of caregivers’ burden in social dimensions such as social interaction. 18 There is a need to improve the understanding of the relationship between caregiver burden and HF caregiver outcomes because the effects of caregiving on the patient and caregiver can have extensive impacts on both individuals’ physical, psychological, and financial factors. 18 This review will determine what factors of HF caregiver’s burden are associated with HF caregiver outcomes and which interventions are the most effective at improving the well-being of HF caregivers to help guide the development of a novel intervention to influence the design of a future clinical study. Therefore, the aims of the current review were to summarize articles describing caregiver burden and the association between health outcomes as well as describing interventions focusing on this population.

Methods

Study Design

This review was conducted using PRISMA guidelines 19 and followed the Whittemore and Knafl 20 methods for a systematic review. The review consisted of 5 steps: (1) problem identification; (2) literature searching; (3) data review and evaluation; (4) data synthesis and analysis; and (5) data presentation.

Search Methods

The current review performed a search for relevant articles in 4 electronic databases: Scopus, PubMed, Ovid (PsycINFO), and CINAHL. The article search used the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to create the search keywords: (1) “caregiver*” OR “caregiving” OR “family caregiver*”; (2) “burden”; and (3) “heart failure” OR “HF” OR “HF Patients.” Criteria for articles to be included in the review were: (1) the subjects were caregivers or family caregivers of patients with HF; (2) published in peer-reviewed journals in English; (3) original research articles; and (4) studies published between 2011 and 2020. Our search excluded: (1) focus on only patients with HF (not caregivers); (2) focus outside of HF; (3) outcomes not related to family caregivers or HF caregivers (eg, questionnaire development); (4) non-research articles (eg, review articles, editorials, letter to editor papers); (5) articles with non-empirical data; and (6) unpublished masters and doctoral dissertations that did not go through the peer-review process.

Search Outcome

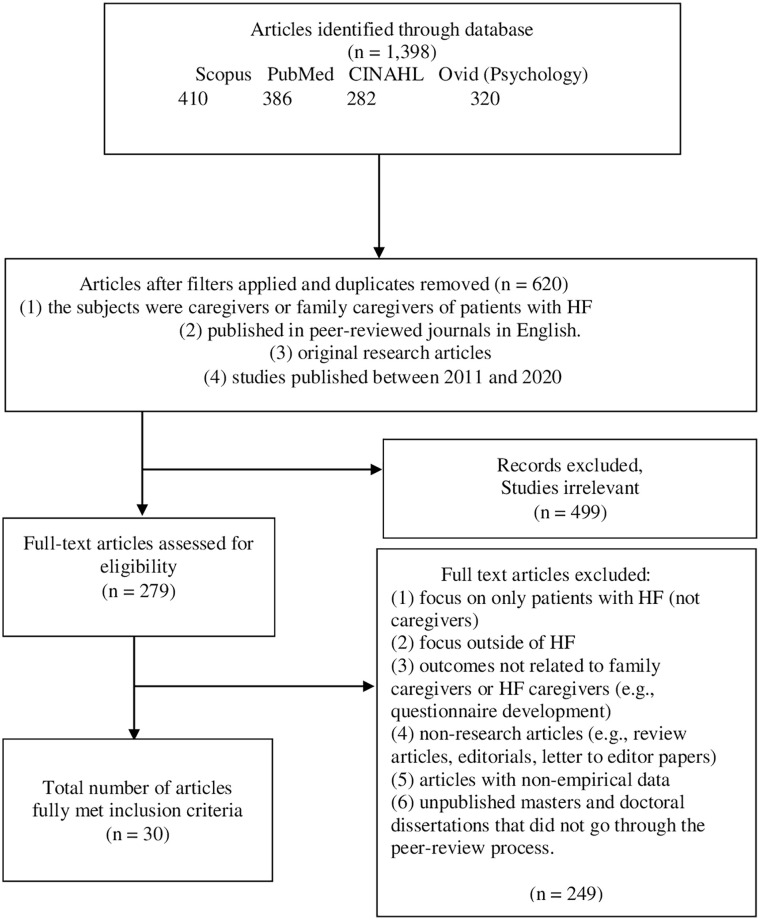

The search resulted in 1398 articles that were published between 2011 and 2020, which were identified in the initial databases (Figure 1). After duplicates were removed, 778 articles remained. Of these, 499 were excluded based on irrelevant studies; 249 full articles were excluded for other reasons, such as abstract screening, wrong outcomes, review articles, or master’s theses and doctoral dissertations without publication and peer-review. Finally, 30 publications met the criteria and were included in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for literature selection adopted from PRISMA Guidelines. 19

Quality Appraisal

Two researchers (W.S. and T.T.) were independently screened and identified primary studies based on the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the appraisals were discussed and resolved among the authors (W.S., T.T., and P.D.). Then 30 studies were evaluated using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). 21 The MMAT is beneficial to use as a quality appraisal for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies. No studies were excluded based on the quality appraisal using the MMAT.

Results

Study Characteristics

The review (Table 1) included 20 cross-sectional studies,4,15,22 -39 5 randomized controlled trials,40-44 2 qualitative studies5,45 1 quasi-experimental study, 46 1 mixed-methods study, 47 and 1 multicenter case-control study. 48 This systematic review included studies conducted in the USA (n = 11), China (n = 7), Italy (n = 3), Turkey (n = 2), Iran (n = 2), Spain (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), United Kingdom (n = 1), and Taiwan (n = 1). The number of participants ranged from 18 to 530.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| Author Country | Purpose | Study design | Sample | Demographics data (mean ± SD) (%) | Instruments | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Rawashdeh et al 22 USA | To determine whether sleep disturbances of patients and their spousal caregivers predicted their own and their partners’ QOL | CS | 78 | • Age 59.53 ± 12.3 years | • Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II) | • Patients’ mental well-being was sensitive to their spouses’ sleep disturbance. |

| • Female (74.4) | • Minnesota living with heart failure | • Patients’ sleep disturbance was significantly correlated with spousal caregivers’ mental well-being (P < .01). | ||||

| • High school (50) | • PHQ-9 | • Sleep disturbance scores were negatively correlated with age in spouses (r = −.220, (P = .05) | ||||

| • Chronic disease (81.9) | • Restfulness of sleep | |||||

| • QOL | ||||||

| Bahrami et al 45 Iran | To explore the Iranian family caregivers’ burden of caregiving for patients with HF | QS | 18 | • Age 31-50 years (77.78) | • In-depth understanding of the experiences of caregiving for HF patient and challenges in the caregiving situation | • Four major themes emerged from the analysis of the transcripts: Lack of care-related knowledge, physical exhaustion, psychosocial exhaustion, and lack of support. |

| • Female (77.8) | • Family caregivers believed that they have little knowledge about the patients’ disease, drugs, and how to perform caregiving roles. | |||||

| • Married (66.67) | • CGs experienced negative physical and psychosocial consequences of full-time and highly extended caregiving roles, such as musculoskeletal disorder, fatigue, and sleep disturbance, and a high level of anxiety, stress, and social isolation | |||||

| • Patient’s daughter (38.89) | • CGs believed that they receive little familial and organizational support on the emotional and financial dimensions of caregiving. | |||||

| • Primary school (50) | ||||||

| • Homemaker (61.11) | ||||||

| • Monthly family income <US$200 (61.11) | ||||||

| • Providing care >6 h/day (77.78) | ||||||

| Bangerter et al 47 USA | To examine the predictors of self-gain and gain a holistic, in-depth understanding of the challenging and positive aspects of caring for a person with HF. | MS | 108 (CS) | • Age 65.9 ± 13.5 years | Quantitative data: | Quantitative results: • Spouse caregivers had 3.3 times higher odds of high self-gain compared with non-spouse caregivers (95% CI 1.15-9.48, P = .023). |

| 16 (QS) | • Female (83.8) | • Caregiver self-gain | • Caregivers with higher preparedness had 1.12 times greater odds of high self-gain (95% CI 1.03-1.21, P = .003). | |||

| • Some college (37) | • Caregiver mastery scale | • Caregivers with higher mastery had 1.16 times greater odds of high self-gain for caregiver age and sex (95% CI 1.00-1.35, p = 0.045). | ||||

| • Married (63.9) | • Caregiver preparedness scale | Qualitative data: authors revealed three themes of self-gain including: (1) caregiving as a means to enhancing relationships, (2) success in negotiating care and healthy behaviors with patients with HF, (3) caregiving as a means of preparing caregivers for the future. | ||||

| • Retired (48.8) | • Zarit Burden inventory (ZBI) | |||||

| • Providing care <1 year (40.6) | • Health literacy marital satisfaction | |||||

| • Spousal caregiver (32.5) | Qualitative data: | |||||

| • In-depth understanding of the challenging and positive aspects of caring for a person with HF | ||||||

| Bidwell et al 23 USA | To quantify the influence of patient and caregiver characteristics on patient clinical event risk rehospitalization or death) in HF | CS | 183 | • Age 57.2 ± 14.3 years | • Caregiver burden inventory (CBI) | • Higher caregiver strain had a 0.94 times lower risk of clinical event (95% CI 0.91-0.97, P < .001). |

| • Female (67.3) | • Caregiver mental health status | • Higher mental health status of caregiver had 0.41 times lower risk of clinical event (95% CI 0.20-0.84, P = .01). | ||||

| • High school (51.2) | • Caregiver contributions (CC-SCHFI) | • Greater caregiver contributions to HF self-care maintenance had 0.99 times lower risk of clinical event (95% CI 0.97-0.99, P = .04). | ||||

| • Spousal caregiver (32.5) | • Greater caregiver contributions to patient self-care management had 1.01 times higher risk of clinical event (95% CI 1.00-1.03, P = .04). | |||||

| Chiang et al 46 Taiwan | To evaluate the effectiveness of nursing-led transitional care combining discharge plans and telehealth care on family CG burden, stress mastery and family function in family CGs of HF patients compared to those receiving traditional discharge planning only. | QE | 30 | • Age >60 years (50) | • The Chinese version of the caregiver burden inventory (CBI) | • Family CGs in both groups had significantly lower burden, higher stress mastery, and better family function at 1-month follow-up compared to before discharge |

| • Female (76.7) | • The mastery of stress scale | • The total score of CG burden, stress mastery, and family function were significantly more improved for the family CGs in the experimental group than the comparison group at post-test. | ||||

| • Bachelor’s degree (53.4) | • The Chinese version of the Feetham family functioning survey | |||||

| • Married (86.7) | ||||||

| • Total household income ≤US$1670-6250 (45) | ||||||

| • Spousal caregiver (50) | ||||||

| • Employed (60) | ||||||

| Caregiving time 1-5 years (53.3) | ||||||

| Cooney et al 24 USA | To test the moderating role of changes in caregivers’ social support and patient-caregiver relationship mutuality in the association between HF patient functioning and caregiver burden | CS | 100 | • Age 57.22 ± 15.66 years | • ZBI | • The reduction in caregiver-patient mutuality over the 12 months of the study amplified the association between patient functioning (ie, dyspnea, symptom severity, and disability) and caregiver burden. |

| • Female (81) | • The ENRICHD social support scale | • Caregiver burden at wave 1 correlated with patient disability at wave 2 P < .05 | ||||

| • Married (60) | • Family caregiving inventory | |||||

| • Relationship with the patient; child (26) | ||||||

| Davidson et al 25 Australia | To describe the profile of those providing care in the community and their needs. | CS | 373 | • Age 31-50 years (77.78) | • Index of socioeconomic disadvantage (SEIFA) index | • Two factors were significant predictors of unmet needs at the time of death which related to caregiver burden compared between caregivers for people with HF and caregivers for people with other diagnoses. First, the increase a year of age (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.01-1.04; P = .005) and not having access to palliative care services (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.24-0.64; P = .000). |

| • Female (77.8) | ||||||

| • Married (66.67) | ||||||

| • Patient’s daughter (38.89) | ||||||

| • Primary school (50) | ||||||

| • Homemaker (61.11) | ||||||

| • Monthly family income <US$200 (61.11) | ||||||

| • Providing care >6 h/day (77.78) | ||||||

| Dirikkan et al 15 Turkey | To evaluate the relationship between the caregiver burden and the psycho-social adjustment of caregivers to cardiac failure patients | CS | 200 | Completed primary school (37.5) | • ZBI | • 94% of the caregivers remarked that after the diagnosis they experienced physical, psychological, social, occupational, or economic changes. |

| • Retired (24.0) | • The psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS-SR) | • 71.5% of caregivers faced difficulties with care provision, and 84% experienced the anxiety. | ||||

| • Spousal caregiver (43) | • Caregiver burden were statistically significant relationships with psychosocial adjustment to illness subscale including vocational environment (r = .484); domestic environment (r = .416); sexual relationship (r = .210); extended family relationships (r = .182); social environment (r = .365); psychological distress (r = .493). | |||||

| Durante et al 4 Italy | To identify predictors of caregiver burden in heart failure; and to evaluate if caregiver contribution to heart failure self-care maintenance and management increases caregiver burden. | CS | 505 | • Age 56.5 ± 14.9 years | • CBI | • The only two predictors of higher developmental burden were patients taking fewer medications, and lower patient mental QOL (F = 2.994, P < .001). |

| • High school (51.7) | • CC-SCHFI) | • Higher levels of physical burden were significantly associated with caregiver older age, fewer medications taken by the patient and lower patient mental QOL (F = 2.534, P < .001). | ||||

| • Married (72.5) | • Social support received by the caregiver | • Higher levels of social burden were significantly associated with caregivers’ older age, fewer hours of caregiving per day, lower levels of caregiver social support, lower caregiver physical and mental QOL, higher patient education, fewer medications taken by the patient and lower patient mental QOL (F = 4.678, P < .001) | ||||

| • Currently employed (56) | • Higher levels of emotional burden were significantly associated with fewer hours of caregiving per day, older patient age, higher patient education, fewer medications taken by the patient, higher level of patient physical QOL and lower patient mental QOL (F = 5.108, P < .001). | |||||

| • Hours of caregiving per day (7.5 ± 7.1) | • Higher levels of total burden were significantly associated with caregivers’ older age, patient older age, higher patient education, and lower patient mental QOL (F = 3.590, P < .001). | |||||

| • Relationship with the patient; child (49.3) | ||||||

| Durante et al 5 Italy | To describe CG contributions to HF self-care maintenance (ie, treatment adherence and symptom monitoring) and management (ie, managing HF symptoms when they occur). | QE | 40 | • Age 53.6 ± 15.66 years | • Elicit in-depth descriptions of how caregivers contributed to the self-care of the patients | • Caregiver contributions to self-care maintenance included practices related to: (1) monitoring medication adherence, (2) educating patients about HF symptom monitoring, (3) motivating patients to perform physical activity, (4) reinforcing dietary restrictions |

| • Female (82.5) | • Caregiver contributions to self-care management included practices related to: (1) symptom recognition, (2) treatment implementation | |||||

| • High school (52) | • Caregivers were able to recognize symptoms of HF exacerbation (eg, breathlessness) but lacked confidence regarding treatment implementation (eg, administering an extra diuretic) | |||||

| • Married (80) | ||||||

| • Employed (52.5) | ||||||

| Ghasemi et al 26 Iran | To investigate the relationship between caregivers burden and family functioning in family caregivers of older adults with HF | CS | 140 | • Age 38.74 ± 12.77 years | • ZBI | • A direct correlation between mean score of care burden and total score of family functioning (r = .345, P = .047). |

| • Female (61.9) | • Family assessment device | • A direct relationship between the score of burden of care and the dimensions of problem solving (r = .206, P = .032) and affective responsiveness (r = .115, P = .045). | ||||

| • Married (79) | • Caregivers of HF patients with chronic disease had higher burden scores than caregivers of HF without chronic disease (t = 2.76, P = .007) and older age (r = .257, P = .007). | |||||

| • Bachelor’s or higher degree (37.7) | ||||||

| • Employed (50) | ||||||

| • Monthly income US$237.5 (44.2) | ||||||

| • Average care rate 5-8 h/day (31.4) | ||||||

| • Affected by a chronic disease themselves (48) | ||||||

| • Relationship with the patient; child (49.29) | ||||||

| • No chronic disease (65) | ||||||

| Grant et al 27 USA | To examine predictors that influence depressive symptoms in informal caregivers of IHF. | CS | 530 | • Age 41.39 ± 10.38 years | • Social support | • 57.7% of caregivers were experiencing depressive symptoms |

| • Married (92.3) | • Social problem-solving | • Caregivers who provided care for 3-4 years had 2.9 times higher odds of depression than caregivers who have provided care for 6 months to 1 year (95% CI = 1.02-8.60, P < .05). | ||||

| • Spousal caregiver (44.9) | • Family functioning | • Rural caregivers had 2 times higher odds of depression than caregivers in urban areas (95% CI = 1.03-3.88, P < .05). | ||||

| • CBI | • Odds of depression decreased 1.28 times with each 1 unit increased in social support (95% CI = 1.21-1.37, P < 0.05). | |||||

| • Depressive symptoms | • Odds of depression decreased 1.20 times with each 1 unit increased in social problem-solving (95% CI = 1.07-1.36, P < .05). | |||||

| Graven et al 28 USA | To examine whether social support and problem-solving mediate relationships among caregiver demands and burden, self-care, and life changes in HF caregivers. | CS | 530 | • Age 41.39 ± 10.38 years | • Dutch objective burden inventory | • Social support may be a relevant mediator of the relationship between caregiver burden and depression (indirect effect = 0.25), with increases in social support associated with decreased depression. |

| • Female (49.1) | • Interpersonal support evaluation | • Increased caregiver burden is associated with worse caregiver self-care, more depression, and negative perceptions of life changes due to caregiving. | ||||

| • Married (92.5) | • Social problem-solving inventory | • Clinicians should assess caregivers’ available support and make appropriate referrals to community services and resources. | ||||

| • Bachelor’s degree (54.9) | • The center for epidemiological studies-depression scale | |||||

| • Spousal caregiver (44.9) | • Denyes self-care practice | |||||

| • Length of time providing care; 1-2 years (40.9) | • Bakas caregiving outcomes scale | |||||

| Hooker et al 29 USA | To examines the associations among mutuality, patient self-care confidence and maintenance, caregiver confidence in and maintenance of patient care, and caregiver perceived burden. | CS | 99 | • Age 57.4 ± 15.8 years | • ZBI | • Patients and caregiver’s mutuality increased the confidence in-patient self-care (P < .05). |

| • Female (80.8) | • Mutuality scale of FCI | • Regression models indicated that caregivers with greater mutuality reported less perceived burden P < .01). | ||||

| • High school (36) | • Caregiver contributions self-care of heart failure index (CC-SCHFI) | • Perceived caregiver burden was also significantly and negatively associated with caregiver confidence in patient self-care (b = −.76, SE = 0.25, β = −.29, P = .003) | ||||

| • Retired (32) | ||||||

| • Married (82) | ||||||

| • Total household income ≤US$40,000 (45) | ||||||

| • Spousal caregiver (60) | ||||||

| • Providing care >8 h/day (58) | ||||||

| Hu et al 30 China | To investigate the status of caregiver burden and identified the factors related to caregiver burden among family caregivers of patients with HF | CS | 226 | • Age 41.9 ± 13.8 years | • ZBI | • The mean ZBI score was 37.1 (SD = 12.3) |

| • Female (57.6) | • Social support rating scale | • 86.7% of caregivers perceived a high level of burden. | ||||

| • Married (75.8) | • General self-efficacy scale | • The caregiver burden was inversely associated with social support (r = −.527, P < .01) and self-efficacy (r = −.509, P < .01). | ||||

| • Junior high school or above (71.2) | • The payment type for treatment (b = −.431, P < .01), monthly family income (b = −.133, P < .01), relationship to the patient (b = .404, P < .01), self-efficacy (b = −.314, P < .01), and social support (b = −.137, P < .01) were significantly related to the caregiver burden. | |||||

| • Monthly family income <US$500 (82.8) | ||||||

| • Spent >4 h/day providing care for the patients (84.1) | ||||||

| • Cared for the patients >1 year (47.8) | ||||||

| Hu et al 40 China | To examine the effects of the multidisciplinary supportive program on caregiver burden, QOL, and depression. | RCT | 118 | • <40 years (58.5) | • ZBI | • Intervention consisted of: (1) health education; (2) peer support group; and (3) regular follow-up and consultations |

| • Female (57.6) | • HRQOL SF-36 | • There were significant improvements in caregiver burden (F = 65.345, P < .001), mental component of QOL (F = 22.482, P < .001), and depression (81.589, P < .001) after post-test and 3 months after post-test in the experimental group. | ||||

| • Married (83.1). | • Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) | • The physical component of QOL did not improve after the intervention. | ||||

| - Senior high school (32.3) | • There was no significant improvement in caregivers’ physical health at either 3 or 6 month following discharge. | |||||

| • Employed (75.4) | ||||||

| • Monthly family income <US$500 (82.2). | ||||||

| • Taken care of the patients for >1 year (54.2) | ||||||

| • Spent >4 h/day on caregiving (84.7) | ||||||

| Hu et al 31 China | To investigate the QOL and to identify the factors (characteristics of patients and caregivers, caregiver burden, self-efficacy, and social support) related to QOL among family caregivers of patients with HF | CS | 251 | • <50 years (78.1) | • Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) | • The median scores of physical and mental QOL were 70 and 60, respectively. |

| • Female (58.2) | • ZBI | • NYHA classification (b = −.675, P < .01), caregiving h per day (b = −1.929, P < .01), number of readmissions (b = −.344 P < .01), caregiver burden (b = −.013, P < .05), social support (b = .039, P < .05), and self-efficacy (b = .217, P < .05) were associated with PCS. | ||||

| • Married (76.1) | • General self-efficacy scale (GSE) | • NYHA classification (b = −.700, P < .01), caregiving hours per day (b = −1.608, P < .01), number of readmissions (b = −.362, P < .01), caregiver burden (b = −.015, P < .05), and social support (b = .039, P < .05) were significantly associated with MCS. | ||||

| • Junior high school education or higher (71.7) | • HRQOL SF-36. | |||||

| • Monthly family income <US$500 (82.9) | ||||||

| • Unemployed while taking care of patients (52.6) | ||||||

| • Spent >4 h/day providing care (75.3) | ||||||

| • Cared for the patients >1 year (47.8%) | ||||||

| Hu et al 32 China | To investigate the status of depressive symptoms and to identify the factors that are associated with depressive symptoms in family care-givers of patients with HF | CS | 134 | • Age 41.4 ± 13.6 years | • ZBI | • 31% of the caregivers experienced depressive symptoms. |

| • Female (58.2) | • Caregivers’ Depressive symptoms (the CES-D scale) | • The type of payment for treatment (b = −.312, P < .01), readmissions within the last 3 months (b = .397, P < .01), duration of caregiving (b = −.213, P < .05), caregiver burden (b = .299, P < .05), active coping (b = −.235, P < .01), and negative coping (b = .245, P < .05) were related to caregivers’ depressive symptoms. | ||||

| • Married (83.6) | • Coping ability (the 20-item SCSQ) | |||||

| • Equivalent to junior high school or below (58.2) | ||||||

| • Monthly family income <US$500 (82.8) | ||||||

| • Spousal caregivers accounted for 29.1% of the sample | ||||||

| • Unemployed (61.9) | ||||||

| • Spent >4 h./day caregiving (84.3) | ||||||

| • Provided care to the patient >1 year (53) | ||||||

| Hwang et al 33 USA | To identify factors associated with the impact of caregiving | CS | 76 | • Age 53.4 ± 15.7 years | • Dutch objective burden inventory | • Impact on finances was related to CGs’ economic status, perceived control, and social support. Although caregivers’ economic status (β = −.43; P < .001) explained a considerable amount of variance in the financial strain (16%), CGs’ perceived control (β = −.24; P = .01) and the availability of social support (β = −.26; P = .01) |

| • Female (54) | • The medical outcome study social support survey | • Impact on schedule was associated with patient’s NYHA class (β = .27; P = .003), amount of care tasks performed (β = .43; P < .001), CG’s perceived social support (β = −.37; P < .001) | ||||

| • High school (33.5) | • The control attitudes scale-revised | • CG’s esteem was associated with CGs perceived social support and the patient’s comorbid conditions (β = 1.57; P = .01), nonwhite caregivers felt more positive about their role as a CG than did white CGs (β = .29; P = .006). The more often a patient had visited the emergency department in the preceding 12 months, the less positive CGs felt about their role as a CG (β = −.25; P = .02). | ||||

| • Married (54) | • The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) | |||||

| • Total household income ≤US$1670-6250 (45) | • The physical and mental component summary scores of the short form 36 health survey | |||||

| • Spousal caregiver (56) | • The patient health questionnaire (PHQ-8) | |||||

| • Employed (41) | ||||||

| • Providing care >7 h/day (64) | ||||||

| Jackson et al 34 China | To describe the burden of caregiving on informal caregivers of patients with chronic HF | CS | 458 | • Age 60.1 ± 10.6 years | • Caregiver self-completion (CSC) | • Time spent and activity: caregivers were most often required to provide support included reminding patients to take their medication (70%), helping patients prepare meals (65%), and providing emotional support and encouragement (59%). |

| • Female (60) | • EuroQol (EQ-5D-3L) | • Social life and employment: 63% of caregivers reported that caregiving had resulted in changes to some aspects of their lives such as reduction in their social activities (33%), followed by reductions in time for themselves (21%) and time for their other family members (12%). | ||||

| • Retired or pensioners (74) | • HF caregiver questionnaire (HF-CQ) | • Caregivers’ own health: 57% of the caregivers reported that caregiving had negatively affected their health in some way such as stress (23%), anxiety (23%), sleeping problems (14%), migraines/headaches (9%), and depression (7%). | ||||

| • Full-time employment (16) | • QOL: 79%-99% reported that HF had no impact on QOL | |||||

| • Commonly spouses (77) or a son/daughter (20). | • Economic burden: 22% reported that a change in their job or a reduction in working hours had resulted in a decrease in income. (95%) were not receiving financial support from the health care system or social services | |||||

| • Spent time taking care of the patients 24.5 ± 16.9 h/week | ||||||

| Lee et al 35 USA | To examined whether HF patients with depression received assistance from CPs living outside of their homes | CS | 372 | • Age 47 ± 13.20 years | • Care partners support | • Depression was not significantly associated with caregiving strain (IRR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81: 1.23, P = .984). |

| • Female (64.4) | • Modified caregiver strain index (MCSI)) | • CPs who provided greater in-person support h per week had significantly greater MCSI scores (IRR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.01-1.06, P = .008). However, CPs’ weekly telephone support hours were not significantly associated with their MCSI scores (IRR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.98-1.06, P = .341). | ||||

| • Married (69.9) | • Patient depression had no effect on caregiver burden (IRR = 1.00, P = .843). | |||||

| • Employed (63.1) | ||||||

| • At least some college education (73.1) | ||||||

| • CPs were most commonly the adult child of their support recipient (61.8) | ||||||

| Leung et al 36 China | To examined whether support from family and friends would associate with caregiver burden and patient’s QOL to different extents, mediated via caregiving self-efficacy in patient–caregiver dyads with patients requiring palliative care using a structural equation modeling approach. | CS | 225 | • Age 57.1 ± 14.6 years | • Caregiver burden Chinese version (C-CGI-18) | • The final model provided a satisfactory fit (SRMR = 0.070, R-RMSEA = 0.055 and R-CFI = 0.926) with the data, as good as the hypothesized model did (P = .326). |

| • Females (64.9) | • Chinese version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (C-MSPSS) | • Family support had a significant negative indirect effect on caregiver burden and a significant positive indirect effect on patient’s QOL through caregiving self-efficacy, whereas friend support had a significant positive direct effect on caregiver burden but a minimal effect, if any, on a patient’s QOL. | ||||

| • Married (83.1) | ||||||

| • Secondary education or above (68.4) | ||||||

| • Relationship with the patient (child) 51.6 | ||||||

| • Perceived health status 3.28 ± 0.97 | ||||||

| • Had a domestic helper (25.3) | ||||||

| Liljeroos et al 41 Sweden | To describe the 24 month effects from a psycho-educational intervention in relation to caregiver burden and morbidity in partners to HF patients | RCT | 155 | • Age 67.1 ± 12.1 years | • CBI | • A younger partner, less comorbidity, higher levels of perceived control, better physical health and less symptoms of depression in patients, and better mental health in the partners were factors associated with absence of increased caregiver burden over time. |

| • Females (75) | • QOL (SF-36) | Intervention: consisted of: face-to-face counseling; educational booklets; and computer programs. | ||||

| • Retired (68) | • Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II) | • The intervention focused on help partners develop problem- solving skills to be able to recognize and alter factors contributing to emotional and psychological stress. | ||||

| • Exercised >3 h/week (50) | • Control attitude scale (CAS) | • The mean total caregiver burden in both groups was found to be significantly increased compared to baseline (36 ± 12 vs 38 ± 14, P = .05). | ||||

| • There were no significant differences between the intervention and control group in any dimension of caregiver burden after 24 months | ||||||

| Malik et al 37 UK | To compare experiences of caring for a breathless patient with lung cancer versus those with heart failure and to examine factors associated with CG burden and positive caring experiences | CS | 51 | • Age 65.8 ± 12.7 years | • The modified Borg breathlessness scale | • Higher burden was associated with poorer “quality of patient care” and worse CGs’ psychological health (R 2 = 0.37, F = 12.2, P = .01) |

| • Female (82) | • ZBI | • Caregiver depression and looking after more breathless patients were associated with fewer positive caring experiences (R 2 = 0.15, F = 4.4, P = .04). | ||||

| • Married (86.7) | • Hospital anxiety and depression scale | |||||

| • Spousal caregiver (70) | • Short form-36 (SF-36) | |||||

| • Employed (82) | ||||||

| Metin and Helvacı 38 Turkey | To examine the correlation between quality of life, depression, anxiety, stress, and spiritual well-being in patients with heart failure and their family caregivers | CS | 60 | • Age 52.0 ± 13.5 years | • FCI | • QOL was negatively associated with depression (r = −.808, P < .05). |

| • Females (25.0) | • Depression anxiety stress scale (DASS) | • QOL was positively correlated with spiritual well-being (r = .548, P < .05). | ||||

| • Primary school (80) | • FACIT–Sp | • Depression was negatively associated with spiritual well-being (r = −.640, P < .05). | ||||

| • Married (100.0) | • WHOQOL-BREF | • QOL was associated with health status and spiritual well-being respectively (r = .434, r = .575, P < .05) | ||||

| • Income levels (moderate) (85.0) | • Depression was negatively correlated with health status and spiritual well-being respectively (r = −.390, r = −.513, P < .05). | |||||

| • Employed (81.7) | ||||||

| • Relationship (Spouse) (53.3) | ||||||

| • Duration of caregiving ≤5 years (75) | ||||||

| • Daily caregiving time >8 h. (40.0) | ||||||

| Ng and Wong 42 China | To examine the effect of a home-based palliative heart failure (HPHF) program on QOL, symptoms burden, functional status, patient satisfaction, and caregiver burden among patients with ESHF | RCT | 84 | • Age 78.3 ± 16.8 years | • ZBI | • The structure of the HPHF program included post discharge home visits and telephone calls. |

| • Females (56.1) | • QOL | • A statistically significant between-group effect was found, with the HPHF group having significantly higher QOL total score than the control group (P = .016) and there was significant group × time interaction effect (P = .032). | ||||

| • No schooling (44.2) | • QOL: there were significant improvements over time.in the physical (P = .011), psychological (P = .04), and existential (P = .027) domains between the intervention and control groups. | |||||

| • Retired (97.7) | • Caregiver burden: a significant difference was noted between the intervention and control groups at 4 weeks in the aspects of dyspnea (P = .02), emotional function (P = .014), mastery (P = .019), and the total score (P = .01). | |||||

| • Perceived economic status (just enough) (58.1) | • Caregiver burden: there was no between-group effect noted at 12 weeks for any group. | |||||

| Piamjariyakul et al 43 USA | To improve family caregiver outcomes | RCT | 20 | • Age 61.4 ± 15.7 years | • Preparedness scale | • At 6 months, compared to standard care, the intervention group had significantly fewer rehospitalizations (P = .03), higher caregiver confidence (P = .003) and higher social support (P = .01) were significantly higher, and lower caregiver depression (P = .01) than control. While preparedness on HF home care and caregiver burden were not statistically significant differences. |

| • Female (85) | • Perceived social support | |||||

| • High school (60) | • CBI | |||||

| • Married (70) | • The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) | |||||

| • Employed (60) | • Helpfulness rating | |||||

| Timonet-Andreu et al 48 Spain | To analyze the relationship between HF patients’ use of hospital services and the HRQOL of their family caregivers. | MCS | 530 | • Age 56.3 ± 14.3 years | • Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) | • Patients’ use of hospital services was associated with worsened QOL for family caregivers, with an overall OR of 1.48 (95% CI: 1.23-1.79, P < .001). |

| • Female (77.4) | • PHQ-9 | • A positive correlation was found between patients’ perceptions of their physical health and the perceived mental health of caregivers (r = .127, P = .004) and between the perceived mental health of both (r = .291; P < .001). | ||||

| • Primary school (62.6) | • HRQOL | |||||

| • Relationship with patient; child (50.9) | ||||||

| Vellone et al 44 Italy | To evaluate the influence of mutuality as a whole and of its dimensions on self-care maintenance, management, and confidence in HF patient caregiver dyads | RCT | 366 | • Age 58.61 ± 15.66 years | • Mutuality scale | • There is also evidence of actor effects of patient and caregiver mutuality on patient self-care confidence (B = 4.144, P = .039) and on caregiver self-care confidence (B = 9.209, P < .001). |

| • Female (73.3) | • Caregiver contribution to self-care of heart failure index | • The only partner effect that we found was the effect of patient mutuality total score on caregiver contribution to self-care management (B = 5.756, P = .014). | ||||

| • Married (69.6) | • Total score of patient mutuality also had a partner effect on caregiver self-care management (ie, responses to symptoms of HF exacerbation). | |||||

| • Unemployed or retired (53.44) | ||||||

| • High school (37.5) | ||||||

| • Relationship with patient; child (43.5) | ||||||

| Yeh and Bull 39 USA | To examine the influences of older peoples’ activities of daily living dependency, family CGs’ spiritual well-being, quality of relationship, family support, coping, and care continuity on the burden of family CGs of hospitalized older people with CHF using the Resiliency Model of Family Stress, Adjustment, and Adaptation. | CS | 50 | • Age 60.33 ± 14.42 years | • JAREL spiritual well-being scale (SWBS) | • Patients’ ADL dependence, spiritual well-being, coping, quality of relationships, lack of family support, and care continuity accounted for 66% of the variance in family CG burden. |

| • Female (70) | • Carers’ assessments of managing index (CAMI) | |||||

| • High school (58) | • Care continuity scale | |||||

| • Monthly income > US$ 2000 (48) | • Caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) | |||||

| • Married (86.7) | • Caregiver’s esteem subscale | |||||

| • Spousal caregiver (40) | • Lack of family support subscale | |||||

| • Employed (82) | • Index of ADL | |||||

| • Length of time in the caregiver role >1 year (68) | ||||||

| • Providing care >6 months (80) |

Abbreviations: CBI, caregiver burden inventory; CG, caregiver; CPs, caregiver partners; CS, cross-sectional study; FACIT–Sp, functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–spiritual well-being scale; FCI, family caregiving inventory; HF, heart failure; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; MCS, multicenter case-control study; MS, mixed-methods study; PHQ-9, the patient health questionnaire 9-it; QE, quasi-experimental study; QOL, quality of life scale; QS, qualitative study; RCT, randomized controlled trial study; WHOQOL-BREF, the world health organization quality of life short form; ZBI, Zarit Burden Inventory.

Sample Characteristics of Caregivers

Over 60% of caregivers were older than 50 years (65.52%) and the majority of the participants were female and married. Most of the studies reported that caregivers had a primary school education or higher (82.35%). The majority of the participants had a monthly income between 237 and 3330 US dollars; 53.33% of the studies indicated that the HF caregivers were unemployed. Most of the studies reported that 52.25% received care from spousal caregivers; the majority of caregivers provided care for more than 1 year (77.78%). Most caregivers (91.67%) spent more than 4 h per day taking care of HF patients.

Caregivers Burden Measurement

The instruments included the direct measurement of caregiver burden and the consequence of caregiver burden measurement. First, caregiver burden was measured by the Zarit Burden Inventory (ZBI) and the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI). Second, the consequence of caregiver burden was measured by physical, psychological, and societal health outcomes.

Eleven researcher teams used the ZBI for measuring caregiver strain and stress. The ZBI is a 22-item self-reporting survey consisting of a 5-point Likert-scale, with responses of 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = most often, and 4 = always. The total scores ranged between 0 and 88, with higher scores representing a higher burden of care. Scores of less than 30 were considered mild, scores that ranged between 30 and 60 represented moderate, and scores higher than 60 represented severe burden of care. In addition, researchers also used the CBI in some studies (n = 7) to measure the individual’s levels of strain of caregiver and caregiver burden. This tool is a 24-question self-report questionnaire with 5-point Likert-scale responses. The total scores ranged from 0 to 100, with responses from 0 = minimum burden to 4 = maximum burden, a higher scale and dimension scores represented a higher burden of care.

Several researchers (Table 1) indicated that caregiver burden in HF influenced physical, psychological, social and lifestyle outcomes as a consequence of providing care and support. Physical outcome was measured by the Caregiver Strain Index. 48 Psychological outcomes consisted of depression and psychological health. Depression was measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale,28,30 -32,40 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).22,27,48 Psychological health was evaluated by Caregiver Mental Health Status, 23 Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), 38 and the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS-SR). 15

Societal outcomes were measured by social support.5,27,31,36 Functional outcomes were measured by the following factors: (1) self-care,5,23,28 (2) QOL: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire, 22 the Health-Related QOL questionnaire (HRQOL), 48 (3) self-efficacy,30,31 (4) self-gain, 47 (5) the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36),33,37 (6) activities of daily living, 39 and (7) clinical events. 23

Caregiver Burden

The majority (86.7%) of caregivers of patients with HF (Table 1) perceived a high level of burden. 30 Comorbidity and aging were associated with the severity of caregivers’ burden. For instance, caregivers of HF patients with chronic disease had higher burden scores than caregivers of HF without chronic disease (t = 2.76, P = .007). Age was positively related (r = .257, P = .007) with caregiver burden. 26 Caregivers’ burdens were significantly related to caregivers’ older age, patient’s older age, higher patient education, and lower patient mental QOL (F = 3.590, P < .001). 4 Moreover, the unmet needs at the time of death, such as physical support and community support, were related to the caregiver burden. For example, patients with HF had 0.39 times lower opportunity to access palliative care compared with patients with other chronic conditions (95% CI 0.24-0.64; P < .01). 25

Almost all caregivers (94%) remarked that after the HF diagnosis, HF caregivers experienced physical, psychological, social, and economic burden. 15 Physical burden was incurred when providing support for example reminding patients to take their medications (70%), and helping patients prepare meals (65%), etc. 34 Higher levels of physical burden were significantly related to caregiver older age, fewer medications taken by the patient, and lower patient mental QOL (F = 2.534, P < .001). 5 Psychological burden was identified as one of caregiving’s major problematic aspects, more than half (57%) of HF caregivers asserted that caregiving had negatively affected their health due to stress, anxiety, sleeping problems, and depression. 34 Moreover, emotional burdens were related to hours of caregiving during the day, patient age, patient education, medications taken, and QOL (F = 5.108, P < .001). 5

Social burden also had a large impact on caregivers: most caregivers (63%) noted that caregiving had resulted in changes in some aspects of their lives such as reductions in their social activities, reductions in time for themselves, and reduced time for their other family members. 34 Social burdens were significantly related to the caregivers’ age, hours of caregiving per day, caregivers’ social support, caregivers’ QOL, patients’ education, medications taken, and patients’ mental QOL. 5 On the other hand, one-fourth of caregivers asserted that economic burden, such as a change in their job or a reduction in working hours had resulted in a reduce in income. Almost all caregivers (95%) were not receiving financial support from the healthcare system or social services. 34 Moreover, the following were significantly associated with the caregiver burden: the payment type for treatment (b = −0.431, P < .01), monthly family income (b = −0.133, P < .01), relationship to the patient (b = 0.404, P < .01), self-efficacy (b = −0.314, P < .01), and social support (b = −0.137, P < .01). 30

The Relationship Between Caregivers’ Burden and Their Health Outcomes

Clinical outcomes (rehospitalization or death), higher caregiver strain had a 0.94 times lower risk of clinical event compared to lower caregiver strain (95% CI 0.91-0.97, P < .001). 23 Then, higher mental health status of caregivers had a 0.41 times lower risk of a clinical event compared with lower health status (95% CI 0.20-0.84, P = .01). Next, greater caregiver contributions to HF self-care maintenance had a 0.99 times lower risk of clinical event (95% CI 0.97-0.99, P = .04). However, greater caregiver contributions to patient self-care management had 1.01 times higher risk of clinical event (95% CI 1.00-1.03, P = .04). 23 As regards societal outcomes, caregiver burden impacted finance. For instance, caregiver economic status was a significant predictor of financial strain, caregivers perceived control and social support. 33

Interventions for Heart Failure Caregivers

Five randomized control trials and 1 quasi-experimental study were identified to reduce caregiver burden. Two experimental studies reported that a brochure for caregivers, education (eg, lectures, skills training), peer support group, regular follow-up and consultations, and computer programs significantly improved caregivers’ burden, mental health, and depression in the experimental group.40,41 Ng and Wong 42 found that a home-based palliative HF program (ie, home visits and telephone calls) was statistically significant between groups and at 12 weeks had higher satisfaction (P = .001) and lower caregiver burden (P = .024) than the control group.

Then, Vellone et al 44 indicated the effects of patient and caregiver mutuality on patient self-care confidence (B = 4.144, P = .039) and on caregiver self-care confidence (B = 9.209, P < .001) and the effect of patient mutuality total score on caregiver contributions to self-care management (B = 5.756, P = .014). Their study suggests that the intervention could improve mutuality in HF caregivers and may influence patient self-care and caregiver contribution to self-care. 44 One quasi-experimental design used a telehealth follow-up intervention to implement health education and counseling. The telehealth also indicated that the caregiver burden score was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group by the mean score of 23.27 and 32.37, respectively. 46 However, the telephone was not statistically different at the 6-month follow-up. 43 Moreover, there was no significant improvement in caregivers’ physical health at either 3 or 6 months following discharge. 40

Caregiver Perceptions

Two qualitative studies reported that caregiver contributions to self-care maintenance included practices associated with the following: (1) monitoring medication adherence, (2) educating patients about HF symptom monitoring, (3) motivating patients to perform physical activities, and (4) reinforcing dietary restrictions. Researchers also found that caregiver contributions to self-care management included practices associated with (1) symptom recognition and (2) treatment implementation. 5 In addition, caregivers were able to recognize the symptoms of HF exacerbation (eg, breathlessness) but lacked confidence regarding the implementation of treatment (eg, administering an extra diuretic). Therefore, caregiving could enhance relationships, lead to success in negotiating care and healthy behaviors with patients with HF, and prepare caregivers for the future. 47 While one study presented the factors related to caregiver burden including lack of care-related knowledge, physical exhaustion, psychosocial exhaustion, and lack of support. 45

Discussion

Caregivers benefit patients with HF because they provide care, health support, and improve the patients’ QOL.24,49 The current review highlights the importance of acting as a caregiver for HF patients that had a strong effect on physical, psychological, and social factors of the caregivers’ own lives. This review was concurred with the study of Clements et al 50 that most caregivers were female and spouses of patients with HF. Several studies found that caregivers experienced physical, psychological, social, occupational, or economic changes due to providing care.15,30,48,51 Similarly, 1 study reported that spousal caregiver burden was significantly correlated with relationship dissatisfaction, worse patient depression and decreased patient-perceived social support. 52

The findings of several studies showed that HF caregivers spent more than 8 h per day providing care for HF patients.31,32 Some studies reported that caregivers spent 5 to 8 h or more each day when taking care of HF patients.26,38 Caregivers who cared for patients with HF many hours a day had a higher risk of emotional stress, and some caregivers were not psychologically prepared for the caregiver role. This review found that HF caregivers spent more time providing care, which affected the quality of care and incurred negative caregiver outcomes such as poor psychological well-being, poorer health, burden, and lower QOL. 17

Caregivers of patients with chronic illness shoulder a larger responsibility, and this larger caregiver burden altered their physical, psychological, social, and financial functioning. 53 Healthcare providers mostly focus on patients with HF by alleviating HF symptoms and providing a continuing care plan for patients—without assessing the caregivers’ burden. The assessment of burden should include both caregiver situation and burden assessment. First, healthcare providers have to collect the information of caregiver situations consisting of needs, strengths, challenges, and resources for the family caregiver.54,55 Second, healthcare providers also need to perform a comprehensive assessment of caregivers’ burden including physical, psychological, social, and economic burden. 56

The complexity of HF often overwhelms the caregivers who prioritize the care given to the patients. Patients use of hospital services had 1.48 times higher odds of worsened QOL for family caregivers compared with patients who did not require hospital services (95% CI: 1.23-1.79, P < .001). Then, caregivers’ knowledge and experience were the important factors in order to provide effective care because they contributed to caregiver self-gain, which is the strength and confidence to provide care. After that, caregiver contributions to HF self-care maintenance had a 0.99 times lower risk of rehospitalization or death (95% CI 0.97-0.99, P = .04). The contributions in self-care of caregivers represented the relationship of caregivers and patients so the engagement between caregivers and patients could prevent clinically adverse events in patients. 16

Several research teams have developed interventions of health education, post-discharge home visits, phone calls, counseling, and support groups to reduce the caregivers’ burden.40,42 All the interventions were effective in reducing the burden of HF care in caregivers. However, the intervention was effective only for a short period of time. The long-term follow-up found there were no significant differences in caregivers’ burden between the intervention and control group at 24 months after intervention. The interventions were not effective in the long-term follow-up because HF is a chronic condition and patients usually suffer from the exacerbation of HF symptoms several times after HF diagnosis—particularly pain, dyspnea, depression, gastrointestinal distress, and fatigue. 57 The longer caregiving time increased the risk of HF burden in caregivers. Previous interventions tried to solve caregivers’ burdens by providing health education, emotional support, and support groups. Another important missing component would be social support in order to promote the support from social service and healthcare systems. Caregiver burden was negatively associated with social support, for example, increasing social support was associated with decreasing depression.27,28

Limitations

The current review had 6 limitations. First, the sample size in each study varied widely, so the findings of comparison between variables might be imprecise. Second, they did not report some variables in the results or did not clearly include details in the table such as outcomes of care, relationships with the patients, lengths of time providing care; it may develop a biased interpretation of the findings which could impact study validity. Third, the instrument of HF caregiver burden in each tool was heterogeneous and based mostly on self-reporting surveys, which are not the most reliable sources of data. Fourth, there was a low diversity of the HF caregiver demographic characteristics, with all of study participants being female, HF caregivers with spouses, and relationships to patients. As such, the results from the studies were not generalizable to males, other relationships to the caregiver, and other status. Fifth, our study did not use the theory to identify the outcomes. Future research needs to apply the Social Determinant of Health framework with a stronger rationale for the significance of the topic, in particular, it would be stronger if it provided specific information about the domains of caregiver burden and how it is important to understand interpersonal relationships and social interaction components of caregiver burden. Finally, the current review included only English language publications, which might have missed out on pertinent studies performed in other languages and other areas. Future research should be included in all types of studies in other languages; it might change the results that could be improved HF caregivers.

Conclusion

The current findings confirm that HF caregiver burden is significantly related to physical, psychological, and social factors. The current review also confirms that intervention studies can improve mutuality in HF caregivers and influence patient self-care and caregiver contributions to self-care. Despite the early state of the evidence in this field, it seems that effective management of HF caregivers will play a significant role in the future in reducing of caregiver burden for the patients with HF and their caregivers.

Footnotes

Author’s Contribution: Two reviewers (W.S., T.T.) screened the titles and abstracts of each article. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the third reviewer (P.D.). The data were extracted by W.S. and cross-checked by T.T. including the discussion between both authors to reach a consensus where differences arose. The synthesis was carried out by W.S. and reviewed by T.T. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the final findings and approved the final version of the article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: No ethical approval was needed.

Informed consent: No inform consent was needed.

ORCID iD: Wanich Suksatan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1797-1260

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1797-1260

References

- 1. Savarese G, Lund LH. Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3(1):7-11. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2016:25:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suksatan W, Tankumpuan T. The effectiveness of transition care interventions from hospital to home on rehospitalization in older patients with heart failure: an integrative review. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2022;34(1):63-71. doi: 10.1177/10848223211023887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durante A, Greco A, Annoni AM, Steca P, Alvaro R, Vellone E. Determinants of caregiver burden in heart failure: does caregiver contribution to heart failure patient self-care increase caregiver burden? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(8):691-699. doi: 10.1177/1474515119863173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durante A, Paturzo M, Mottola A, Alvaro R, Vaughan Dickson V, Vellone E. Caregiver contribution to self-care in patients with heart failure: a qualitative descriptive study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(2):E28-E35. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suksatan W, Tankumpuan T. Depression and rehospitalization in patients with heart failure after discharge from hospital to home: an integrative review. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2021;33(3):217-225. doi: 10.1177/1084822320986965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cowie MR, Anker SD, Cleland JGF, et al. Improving care for patients with acute heart failure: before, during and after hospitalization. ESC Heart Fail. 2014;1(2):110-145. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lum HD, Lo D, Hooker S, Bekelman DB. Caregiving in heart failure: Relationship quality is associated with caregiver benefit finding and caregiver burden. Heart Lung. 2014;43(4):306-310. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung ML. Caregiving in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;35(3):229-230. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26(3):260-266. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hunt CK. Concepts in caregiver research. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(1):27-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jansen L, Dauphin S, De Burghgraeve T, Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, van den Akker M. Caregiver burden: an increasing problem related to an aging cancer population. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(11):1833-1849. doi: 10.1177/1359105319893019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Connors MH, Seeher K, Teixeira-Pinto A, Woodward M, Ames D, Brodaty H. Dementia and caregiver burden: a three-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(2):250-258. doi: 10.1002/gps.5244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Costa MSA, Machado JC, Pereira MG. Burden changes in caregivers of patients with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(10):2322-2330. doi: 10.1111/jan.13728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dirikkan F, Baysan Arabacı L, Mutlu E. The caregiver burden and the psychosocial adjustment of caregivers of cardiac failure patients. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2018;46(8):692-701. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2018.10.5543/tkda.2018.69057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bidwell JT, Lyons KS, Lee CS. Caregiver well-being and patient outcomes in heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32(4):372-382. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicholas Dionne-Odom J, Hooker SA, Bekelman D, et al. Family caregiving for persons with heart failure at the intersection of heart failure and palliative care: a state-of-the-science review. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22(5):543-557. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9597-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitko L, McIlvennan CK, Bidwell JT, et al. Family caregiving for individuals with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;141(22):e864-e878. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103-112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546-553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inform. 2018;34(4):285-291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Rawashdeh SY, Lennie TA, Chung ML. The association of sleep disturbances with quality of life in heart failure patient-caregiver dyads. West J Nurs Res. 2017;39(4):492-506. doi: 10.1177/0193945916672647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bidwell JT, Vellone E, Lyons KS, et al. Caregiver determinants of patient clinical event risk in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16(8):707-714. doi: 10.1177/1474515117711305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cooney TM, Proulx CM, Bekelman DB. Changes in social support and relational mutuality as moderators in the association between heart failure patient functioning and caregiver burden. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;36:212-220. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davidson PM, Abernethy AP, Newton PJ, Clark K, Currow DC. The caregiving perspective in heart failure: a population based study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:342. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghasemi M, Arab M, Mangolian Shahrbabaki P. Relationship between caregiver burden and family functioning in family caregivers of older adults with heart failure. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020;46(6):25-33. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20200511-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grant JS, Graven LJ, Abbott L, Schluck G. Predictors of depressive symptoms in heart failure caregivers. Home Healthc Now. 2020;38(1):40-47. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Graven LJ, Azuero A, Abbott L, Grant JS. Psychosocial factors related to adverse outcomes in heart failure caregivers: a structural equation modeling analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;35(2):137-148. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hooker SA, Schmiege SJ, Trivedi RB, Amoyal NR, Bekelman DB. Mutuality and heart failure self-care in patients and their informal caregivers. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(2):102-113. doi: 10.1177/1474515117730184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu X, Dolansky MA, Hu X, Zhang F, Qu M. Factors associated with the caregiver burden among family caregivers of patients with heart failure in southwest China. Nurs Health Sci. 2016;18(1):105-112. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu X, Hu X, Su Y, Qu M. Quality of life among primary family caregivers of patients with heart failure in Southwest China. Rehabil Nurs. 2018;43(1):26-34. doi: 10.1002/rnj.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu X, Huang W, Su Y, Qu M, Peng X. Depressive symptoms in Chinese family caregivers of patients with heart failure: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2017;96(13):e6480. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hwang B, Fleischmann KE, Howie-Esquivel J, Stotts NA, Dracup K. Caregiving for patients with heart failure: impact on patients’ families. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(6):431-441; quiz 442. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson JD, Cotton SE, Bruce Wirta S, et al. Burden of heart failure on caregivers in China: results from a cross-sectional survey. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2018;12:1669-1678. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S148970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee AA, Aikens JE, Janevic MR, Rosland A-M, Piette JD. Functional support and burden among out-of-home supporters of heart failure patients with and without depression. Health Psychol. 2020;39(1):29-36. doi: 10.1037/hea0000802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leung DYP, Chan HYL, Chiu PKC, Lo RSK, Lee LLY. Source of social support and caregiving self-efficacy on caregiver burden and patient’s quality of life: a path analysis on patients with palliative care needs and their caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):E5457. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malik FA, Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Living with breathlessness: a survey of caregivers of breathless patients with lung cancer or heart failure. Palliat Med. 2013;27(7):647-656. doi: 10.1177/0269216313488812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Metin ZG, Helvacı A. The correlation between quality of life, depression, anxiety, stress, and spiritual well-being in patients with heart failure and family caregivers. Turk J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;11(25):60-70. doi: 10.5543/khd.2020.93898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yeh PM, Bull M. Use of the resiliency model of family stress, adjustment and adaptation in the analysis of family caregiver reaction among families of older people with congestive heart failure. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):117-126. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hu X, Dolansky MA, Su Y, Hu X, Qu M, Zhou L. Effect of a multidisciplinary supportive program for family caregivers of patients with heart failure on caregiver burden, quality of life, and depression: a randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;62:11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liljeroos M, Ågren S, Jaarsma T, Årestedt K, Strömberg A. Long-term effects of a dyadic psycho-educational intervention on caregiver burden and morbidity in partners of patients with heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(2):367-379. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1400-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ng AYM, Wong FKY. Effects of a home-based palliative heart failure program on quality of life, symptom burden, satisfaction and caregiver burden: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Piamjariyakul U, Werkowitch M, Wick J, Russell C, Vacek JL, Smith CE. Caregiver coaching program effect: reducing heart failure patient rehospitalizations and improving caregiver outcomes among African Americans. Heart Lung. 2015;44(6):466-473. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vellone E, Chung ML, Alvaro R, Paturzo M, Dellafiore F. The influence of mutuality on self-care in heart failure patients and caregivers: a dyadic analysis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(4):563-584. doi: 10.1177/1074840718809484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bahrami M, Etemadifar S, Shahriari M, Farsani AK. Caregiver burden among Iranian heart failure family caregivers: a descriptive, exploratory, qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19(1):56-63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chiang LC, Chen WC, Dai YT, Ho YL. The effectiveness of telehealth care on caregiver burden, mastery of stress, and family function among family caregivers of heart failure patients: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(10):1230-1242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bangerter LR, Griffin JM, Dunlay SM. Positive experiences and self-gain among family caregivers of persons with heart failure. Gerontologist. 2019;59(5):e433-e440. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Timonet-Andreu E, Morales-Asencio JM, Alcalá Gutierrez P, et al. Health-related quality of life and use of hospital services by patients with heart failure and their family caregivers: a multicenter case-control study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(2):217-228. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Evangelista LS, Dracup K, Doering L, Westlake C, Fonarow GC, Hamilton M. Emotional well-being of heart failure patients and their caregivers. J Card Fail. 2002;8(5):300-305. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.128005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Clements L, Frazier SK, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Chung ML. The mediator effects of depressive symptoms on the relationship between family functioning and quality of life in caregivers of patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2020;49(6):737-744. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mårtensson J, Dracup K, Canary C, Fridlund B. Living with heart failure: depression and quality of life in patients and spouses. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(4):460-467. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00818-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Trivedi RB, Piette J, Fihn SD, Edelman D. Examining the interrelatedness of patient and spousal stress in heart failure: conceptual model and pilot data. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(1):24-32. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182129ce7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310(6):575-576. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Collins LG, Swartz K. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(11):1309-1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Swartz K, Collins LG. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(11):699-706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bastawrous M. Caregiver burden–a critical discussion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(3):431-441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alpert CM, Smith MA, Hummel SL, Hummel EK. Symptom burden in heart failure: assessment, impact on outcomes, and management. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22(1):25-39. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9581-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]