Visual Abstract

Keywords: translocator protein, neuroinflammation, PET, specific-to-nondisplaceable uptake, radiometabolites

Abstract

Because of its excellent ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake, the radioligand 11C-ER176 can successfully image 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO), a biomarker of inflammation, in the human brain and accurately quantify target density in homozygous low-affinity binders. Our laboratory sought to develop an 18F-labeled TSPO PET radioligand based on ER176 with the potential for broader distribution. This study used generic 11C labeling and in vivo performance in the monkey brain to select the most promising among 6 fluorine-containing analogs of ER176 for subsequent labeling with longer-lived 18F. Methods: Six fluorine-containing analogs of ER176—3 fluoro and 3 trifluoromethyl isomers—were synthesized and labeled by 11C methylation at the secondary amide group of the respective N-desmethyl precursor. PET imaging of the monkey brain was performed at baseline and after blockade by N-butan-2-yl-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methylisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (PK11195). Uptake was quantified using radiometabolite-corrected arterial input function. The 6 candidate radioligands were ranked for performance on the basis of 2 in vivo criteria: the ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake (i.e., nondisplaceable binding potential [BPND]) and the time stability of total distribution volume (VT), an indirect measure of lack of radiometabolite accumulation in the brain. Results: Total TSPO binding was quantified as VT corrected for plasma free fraction (VT/fP) using Logan graphical analysis for all 6 radioligands. VT/fP was generally high at baseline (222 ± 178 mL·cm−3) and decreased by 70%–90% after preblocking with PK11195. BPND calculated using the Lassen plot was 9.6 ± 3.8; the o-fluoro radioligand exhibited the highest BPND (12.1), followed by the m-trifluoromethyl (11.7) and m-fluoro (8.1) radioligands. For all 6 radioligands, VT reached 90% of the terminal 120-min values by 70 min and remained relatively stable thereafter, with excellent identifiability (SEs < 5%), suggesting that no significant radiometabolites accumulated in the brain. Conclusion: All 6 radioligands had good BPND and good time stability of VT. Among them, the o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro compounds were the 3 best candidates for development as radioligands with an 18F label.

The mitochondrial protein 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) is highly expressed in phagocytic inflammatory cells, including activated microglia and reactive astrocytes in the brain and macrophages in the periphery (1,2). Although numerous PET radioligands have been developed to image TSPO, several limitations have restricted their clinical utility for quantifying inflammation in the brain. Of these radioligands, the first-generation TSPO radioligand 11C-(R)-N-butan-2-yl-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methylisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (PK11195) has been the most extensively studied. 11C-(R)-PK11195 has high affinity for TSPO; however, its utility is limited by a low ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake (i.e., nondisplaceable binding potential [BPND]) in the brain and by the relatively short half-life of 11C (20 min) (3,4). Second-generation radioligands, such as 11C-PBR28, offer a higher in vivo TSPO-specific signal but suffer from sensitivity to the single-nucleotide polymorphism rs6971 (5,6), such that low-affinity binders (LABs) have too little TSPO binding to be accurately measured. This sensitivity to the single-nucleotide polymorphism both complicates the interpretation of results and requires genotyping to exclude LABs before imaging. Consequently, new and more effective radioligands are needed to image TSPO.

Third-generation TSPO radioligands were designed to have adequately high BPND across all rs6971 genotypes for reliable quantification and to lack the brain radiometabolite accumulation that interferes with the low specific signal in LABs. In this context, 11C-ER176 is arguably the most promising third-generation TSPO radioligand for clinical research (2,7). More specifically, it displays high specific binding (>80%), an adequately high BPND in LABs, and good time stability of total distribution volume (VT) across all genotypes (8,9). The whole-brain BPND of 11C-ER176 for LABs was 1.4 ± 0.8, which is about the same as that for high-affinity binders with 11C-PBR28 (∼1.2). For all 3 genotypes, the VT values of 11C-ER176 stabilized by 60–90 min to within 10% of their final 120-min values, suggesting that no significant amount of radiometabolites accumulated in the brain (8).

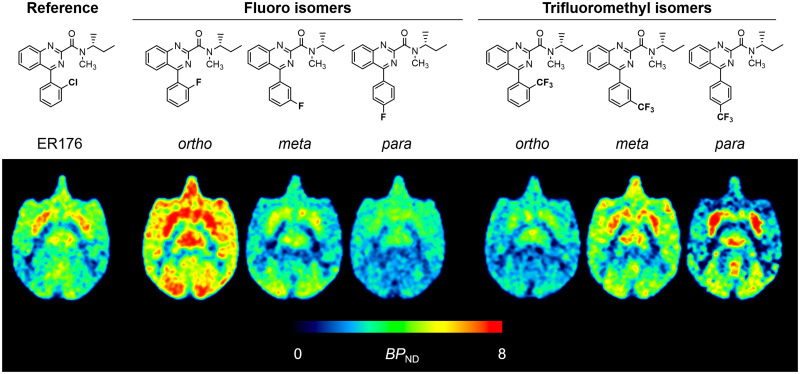

In contrast to 11C, 18F has several benefits for clinical PET imaging. Its relatively longer half-life (110 vs. 20 min) allows imaging for a longer period and for broader distribution of the radioligand from a central radiopharmacy, giving 18F-labeled radioligands greater flexibility for widespread use. However, the structure of ER176 does not contain a fluorine atom for labeling with 18F. Thus, as a first step toward developing an 18F-labeled third-generation radioligand, our laboratory synthesized 6 new fluorine-containing analogs of ER176—3 isomers with a fluoro group and 3 with a trifluoromethyl group at each of 3 positions (ortho, meta, and para) of the pendant aryl ring (Fig. 1) (10). In vitro studies demonstrated that all 6 analogs had high affinity for human TSPO (binding affinity, 1.2 − 7.0 nM) and could be successfully labeled with 11C with good yield (66%–81%, decay-corrected) and excellent chemical (>95%) and radiochemical (>99%) purities. Selecting the most promising radioligand among the 6 candidates to label with 18F would significantly reduce the time and cost of future investigations; however, in vitro data alone would not provide sufficient guidance for this decision.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structures of 11C-ER176 and 6 fluorine-containing analogs. Ki = binding affinity.

The present study used in vivo performance in the monkey brain to select the most promising of the 6 11C-labeled analogs of ER176 for subsequent 18F-radiolabeling. The 2 primary performance criteria were BPND and the stability of VT over time, which is an indirect measure of lack of radiometabolite accumulation in the brain. Both baseline and preblocked PET scans in the monkey brain were obtained, and brain uptake was quantified as VT using the radiometabolite-corrected arterial input function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Radiochemistry

11C-ER176 was synthesized as previously described (11), with a molar activity of 106 ± 65 GBq/μmol (n = 4) at the time of injection and radiochemical purity of 97.1% ± 4.4%.

Six fluorine-containing analogs of ER176 (Fig. 1) were labeled with 11C at the tertiary amide group by 11C-methylation of the respective N-desmethyl precursor as previously described (10). Briefly, the labeling precursors were synthesized by amidation of 4-oxo-3H-quinazoline-2-carboxylic acid followed by palladium-catalyzed coupling with appropriate fluorophenylboronic acids for the fluoro isomers—o-fluoro (SF12063), m-fluoro (SF12051), and p-fluoro (SF12052)—and trifluoromethylphenylboronic acids for the trifluoromethyl isomers—o-trifluoromethyl (SF12050), m-trifluoromethyl (SF12057), and p-trifluoromethyl (SF12054). Six 11C-labeled TSPO radioligands were then obtained by methylation at the secondary amide group of the respective N-desmethyl precursors in dimethyl sulfoxide with 11C-methyl iodide. The molar activity was 222 ± 162 GBq/μmol (n = 18) for the fluoro radioligands and 111 ± 71 GBq/μmol (n = 10) for the trifluoromethyl radioligands at the time of injection (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). The radiochemical purity of all radioligands was 99.6% ± 0.5% (n = 28).

Animals

In vivo experiments were performed on 9 healthy male rhesus monkeys (body weight, 12.4 ± 1.3 kg). Anesthesia was maintained with 1%–2% isoflurane and 98% O2 for the duration of the study. The head was firmly fixed by gauze and tape to the camera bed holder. Body temperature was maintained with air blankets; temperature, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and end-tidal CO2 were monitored for the duration of the study. All animal studies were conducted in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (12) and were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

PET Data Acquisition

The baseline PET scan was acquired for all radioligands (injected activity, 249 ± 78 MBq) using a microPET Focus 220 scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions), with a frame duration ranging from 30 s to 10 min. For the preblocked scans, racemic PK11195 (5 mg/kg) was intravenously administered 5–10 min before the radioligand. All PET scans were acquired for 120 min at baseline and 90 min after preblocking. Concurrent arterial blood sampling was performed in all scans to obtain a radiometabolite-corrected input function for quantification. PET images were reconstructed using a Fourier rebinning algorithm plus 2-dimensional filtered backprojection with attenuation and scatter correction.

Measurement of Parent Radioactivity in Plasma

Fifteen blood samples were drawn from an implanted port in the femoral artery during the PET scan every 15 s for the first 2 min, followed by sampling at 3, 5, 10, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min (varying from 1.0 to 3.0 mL); 14 samples were drawn during the 90-min PET scan. The parent radioligand was separated from radiometabolites as previously described (13). Plasma parent and whole-blood activity concentration were fitted with a triexponential function. The plasma free fraction ( fP) was measured by ultrafiltration as previously described (14).

Kinetic Analysis

All kinetic analyses were performed using PMOD, version 3.9 (PMOD Technologies Ltd.). VT was estimated with Logan graphical analysis (LGA) using 90 min of brain time–activity curves and the radiometabolite-corrected arterial input function for both baseline and preblocked studies. Details on the kinetic analysis are provided in the supplemental materials (15).

Estimating Ratio of Specific to Nondisplaceable Uptake

BPND was used to compare the performance of the 6 radioligands; this measure is a ratio of receptor-specific uptake (VS; VT − VND) to nondisplaceable uptake (VND; free plus nonspecific binding) at equilibrium. In our opinion, BPND is a better binding measure than VT because BPND directly quantifies specific binding. BPND is also more suitable than VS because it is a signal-to-noise measurement that takes background into consideration. BPND was calculated as follows (16):

where VT refers to VT at baseline and VND was estimated by the Lassen plot.

Because only unbound parent radioligand contributes to specific binding to the receptor, and because fP was significantly different before and after preblocking, brain uptake and BPND were calculated and compared for the 6 radioligands using VT and VND corrected for fP as VT/fP and VND/fP, respectively.

Time Stability Analysis of VT

To determine the minimal scan duration needed to reliably measure VT and to indirectly assess whether radiometabolites enter the brain, time stability was evaluated using 120 min of baseline PET data with a truncated acquisition duration from 30 to 120 min in 10-min increments. The identifiability of VT was also evaluated as percentage SE at each truncated scan duration.

Ex Vivo Blood Cell Analysis

The utility of radioligand uptake was investigated in blood cells as a surrogate for brain uptake. The radioactivity concentration in ex vivo blood cells was calculated both at baseline and in preblocked studies as follows (17):

Here, CBC, CPL, and CWB indicate radioactivity concentrations in the blood cells, plasma, and whole blood, respectively. The distribution volume in blood cells (VBC) was then obtained by dividing the radioactivity concentrations in the blood cells by the radioactivity concentration of the parent radioligand in plasma and then corrected for fP (VBC/fP). The correlation between VBC/fP and whole-brain VT/fP and between percentage blockade calculated using VBC/fP and whole-brain VT/fP was assessed using linear regression analysis.

Replication Study and Statistical Analysis

Based on the results of the first scans, replication studies were conducted for selected radioligands in different monkeys to confirm either the radioligands’ most favorable properties or aberrant data. When multiple experiments were performed with the same radioligand, quantitative results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted with Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Uptake in Monkey Brain

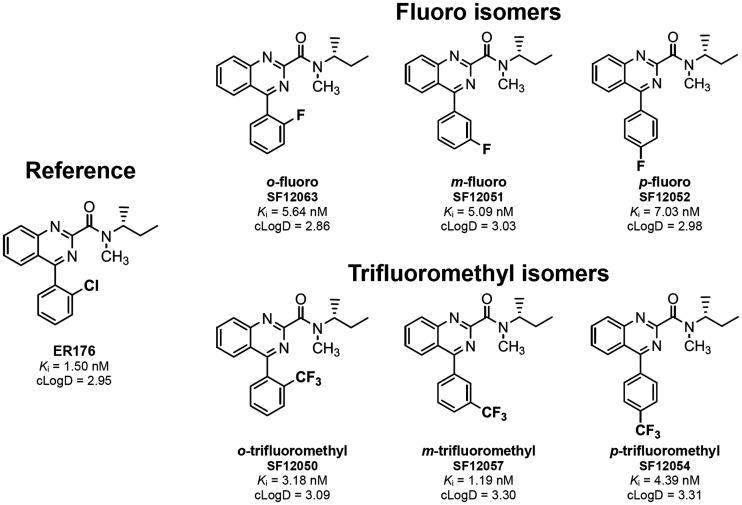

Brain radioactivity at baseline increased rapidly and peaked (SUVpeak, 2.7) at about 25 min after injection (Figs. 2A and 2B) except for the p-trifluoromethyl radioligand, which showed very slow uptake that peaked at 75 min. The m-trifluoromethyl radioligand showed the highest SUVpeak (3.4), and the m-fluoro radioligand showed the lowest SUVpeak (2.6). The brain region with the highest SUVpeak was the striatum (3.9), followed by the thalamus (3.2) and cerebellum (3.1); the parietal cortex had the lowest SUVpeak (2.4). Peak radioactivity uptake in all regions was followed by a smooth decrease in radioactivity level; for example, radioactivity in the whole brain decreased by 37% at 90 min after injection. In preblocked scans, all 6 radioligands showed a similar brain uptake pattern. Brain radioactivity rapidly increased and reached an SUVpeak of 4.1 at 3.5 min after injection, followed by a rapid decline and then a slow washout (Figs. 2C and 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Time–activity curves of whole-brain uptake in baseline and preblocked scans for fluoro (A and C) and trifluoromethyl (B and D) radioligands. Points represent SUVmean (±SD). Conc = concentration.

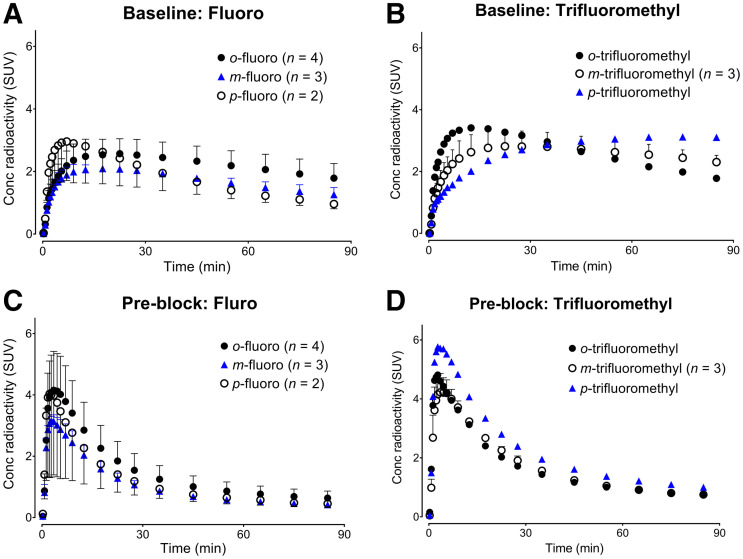

Plasma Concentration of Parent Radioligand

The concentration of parent radioligands in plasma peaked at 1.0–1.3 min after injection at baseline and then rapidly declined, followed by a slow terminal clearance phase. The fitting of plasma parent curves converged by triexponential function in all experiments (Fig. 3). The plasma parent fraction at baseline, expressed as a percentage of total plasma radioactivity, declined rapidly and reached 50% at 25.6 ± 11.6 min for the m-fluoro, p-fluoro, and o-trifluoromethyl radioligands (Supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, the o-fluoro and m-trifluoromethyl radioligands showed a slower decline, reaching 50% at 50.7 ± 14.5 min after injection, and the p-trifluoromethyl radioligand exhibited an unusually high plasma parent fraction (>90%) during the entire 120 min of the scan. In preblocked scans, the parent radioactivity concentrations in plasma showed a rapid increase, peaking at 1.0–1.5 min, followed by a fast washout and then a slow terminal clearance phase in all radioligands. As in our prior studies (11,18), the peak concentration of parent radioligand in plasma was much higher in the preblocked scans than in the baseline scans, because PK11195 blocks the distribution of radioligand to peripheral organs—such as the lung and kidneys—that have high densities of TSPO. The temporal changes in parent fraction in plasma were similar for all radioligands, characterized by a rapid decline that reached less than 50% by 30 min, with a subsequent gradual decline.

FIGURE 3.

Time course of radioactivity concentrations in plasma at baseline and in preblocked scans for fluoro (A and C) and trifluoromethyl (B and D) radioligands. Points represent SUVmean (±SD). Conc = concentration.

Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of plasma revealed at least 5 radiometabolites, all of which appeared less lipophilic than the parent radioligand. A lipophilic radiometabolite appeared in plasma from all radioligand experiments, except the baseline study of the p-trifluoromethyl radioligand. Nonetheless, the amount was negligible (0.07% ± 0.08% of total plasma radioactivity across all arterial samples). The fP was 17.3% ± 8.2% at baseline for the fluoro radioligands, whereas it was significantly higher (22.3% ± 11.3%) after preblocking (n = 9, P = 0.017). In contrast, there was no significant difference in fP at baseline and after preblocking for the trifluoromethyl radioligands; fP was 10.1% ± 2.9% at baseline and 10.6% ± 3.1% at preblock (n = 5, P = 0.423).

Kinetic Analysis

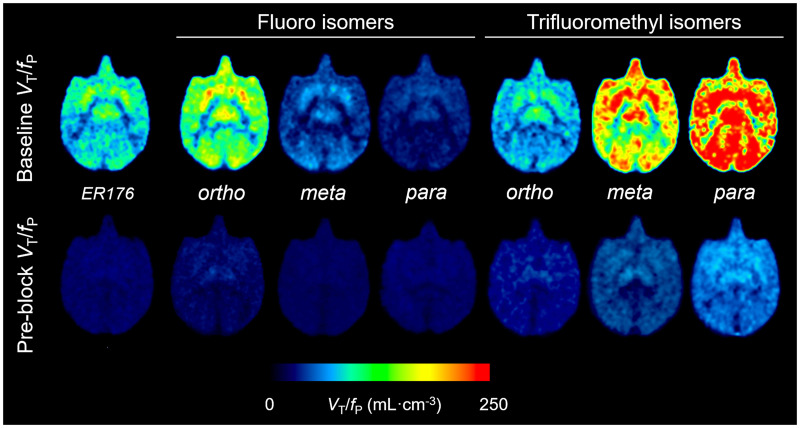

Brain uptake was well quantified by LGA, which does not require specific compartment configurations. Regional brain uptake was reliably quantified as VT with excellent identifiability (SE < 10%) in all baseline and preblocked studies. The trifluoromethyl radioligands generally showed higher VT/fP (mL·cm−3) for baseline and preblocked conditions than the fluoro radioligands (363 vs. 138, respectively, at baseline and 50 vs. 23, respectively, at preblock) (Fig. 4). The p-trifluoromethyl radioligand had the highest VT/fP (493) at baseline, followed by the m-trifluoromethyl (411) and o-fluoro (223) radioligands (Table 1). The 3 brain regions with the highest VT/fP were the striatum (286), thalamus (283), and frontal cortex (269). The 3 with the lowest VT/fP were the cerebellum (208), amygdala (228), and occipital cortex (243). The blockade by PK11195 was 82.5% ± 7.3% and was similar for all 6 radioligands.

FIGURE 4.

Average parametric images of total TSPO binding (VT/fP) for 11C-ER176 and 6 analogs in monkey brain at baseline (top row) and preblocked scans (bottom row). Each VT/fP image was generated using 0–90 min of PET data obtained via LGA.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of VT/fP, Occupancy, VND/fP, and BPND of Whole Brain Among 11C-ER176 and 6 Fluorine-Containing Analogs

| Compound | VT/fP (mL·cm−3) | Occupancy (%) | VND/fP (mL·cm−3) | BP ND | Binding affinity ratio* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Preblock | Blockade (%) | |||||

| Reference (11C-ER176) | 185.8 | 21.3 | 88.5 | 98.6 | 18.6 | 8.9 | 1.3 |

| Fluoro | |||||||

| o-fluoro | 223.8 | 33.3 | 85.0 | 92.9 | 16.6 | 12.1 | 2.8 |

| m-fluoro | 92.2 | 12.7 | 84.9 | 95.6 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 2.7 |

| p-fluoro | 45.3 | 13.4 | 70.3 | 89.0 | 7.9 | 4.8 | 2.9 |

| Trifluoromethyl | |||||||

| o-trifluoromethyl | 119.7 | 31.5 | 73.5 | 87.1 | 18.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| m-trifluoromethyl | 411.0 | 47.6 | 86.9 | 95.0 | 32.6 | 11.7 | 2.0 |

| p-trifluoromethyl | 493.0 | 73.6 | 84.8 | 97.7 | 63.6 | 6.7 | 0.8 |

Ratio of binding affinity (in nM) in LABs to that in high-affinity binders.

Data are mean.

Estimating Ratio of Specific to Nondisplaceable Uptake

The o-fluoro radioligand exhibited the highest ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake (BPND, 12.1), followed by the m-trifluoromethyl (11.7) and m-fluoro (8.1) radioligands (Table 1). The Lassen plot analysis displayed excellent linear correlations (R2 > 0.90) at high receptor occupancies (>87%) in all radioligands (Supplemental Fig. 2). Estimated VND/fP (mL·cm−3) ranged mainly between 5.0 and 35.0, except for the p-trifluoromethyl radioligand (63.6). VND/fP was smallest for the p-fluoro radioligands (7.9), followed by the m-fluoro (9.8) and o-fluoro (16.6) radioligands (Table 1). As shown in Supplemental Table 2, the results were similar to the analysis without fP correction.

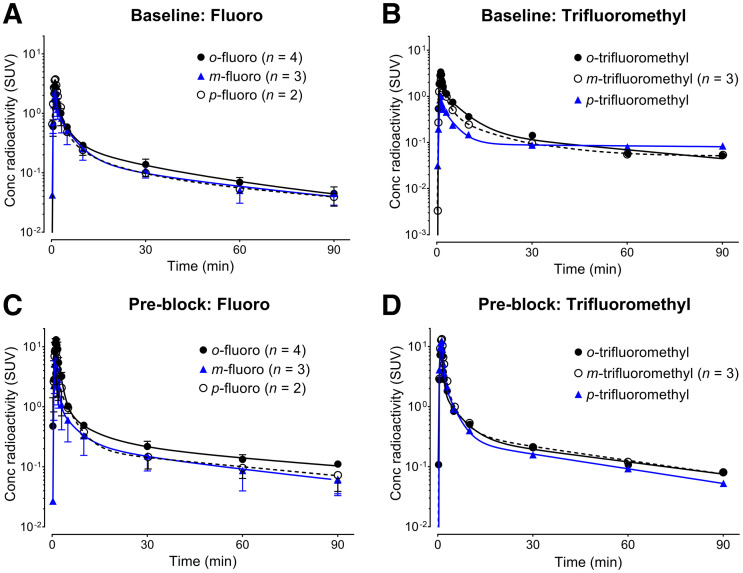

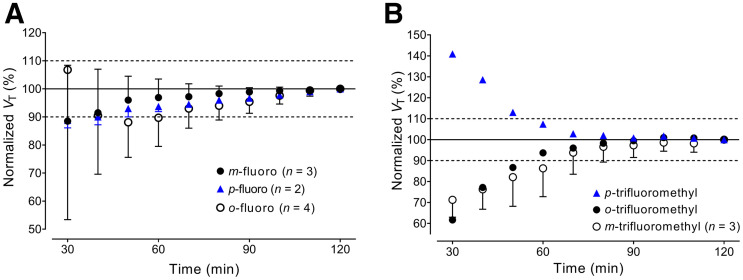

Time Stability of VT

Whole-brain VT asymptotically reached terminal values and converged within 10% of terminal values by the 70th minute of a 120-min scan (Figs. 5A and 5B). VT remained almost stable for the last 50 min, showing an average change of 4.7%, and could be quantified with excellent identifiability (SE < 5%) (Supplemental Fig. 3). The fluoro and trifluoromethyl radioligands took a similar time to achieve a stable VT (70 min). The relatively stable VT measurement over the 70–120 min of the scan suggested no significant accumulation of radiometabolites in the brain.

FIGURE 5.

Time stability analysis of whole-brain VT for fluoro (A) and trifluoromethyl (B) radioligands. VT was calculated via LGA and normalized to terminal VT at 120 min. Points represent mean normalized VT (±SD).

Performance Comparison with 11C-ER176

o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro radioligands showed a BPND similar to or higher than that of 11C-ER176 (8.9), whereas the other 3 showed slightly lower values (Table 1). Regarding the time stability of VT, it took a similar time for the whole-brain VT values of 11C-ER176 and its 6 fluorine-containing analogs to reach and remain stable within 10% of their terminal values (90 vs. 70 min) (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. 4).

Correlation Between Radioligand Uptake in Blood Cells and Brain

Ex vivo blood cell uptake (VBC/fP) correlated well with in vivo whole-brain VT/fP in both baseline (R2 = 0.938, P < 0.001) and preblocked (R2 = 0.750, P = 0.012) studies (Supplemental Fig. 5). The percentage blockade of VBC/fP by PK11195 also correlated significantly with that of whole-brain VT/fP (R2 = 0.583, P = 0.046).

DISCUSSION

Of the 6 11C-ER176 analogs developed by our laboratory, the present study found that the o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro compounds were the most promising. All 3 had a high BPND (the ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake) and a stable VT measured over time in the monkey brain, consistent with the lack of radiometabolite accumulation. Specifically, the o-fluoro radioligand had the third-highest VT/fP at baseline (120 mL·cm−3), 96% of which was specifically bound to TSPO, and the highest BPND (12.1), making it potentially the most promising of all 6 11C-ER176 analogs. The m-trifluoromethyl radioligand showed the second-highest VT/fP at baseline (411 mL·cm−3), high specific binding to TSPO (96%), and high BPND (11.7). The m-fluoro radioligand also showed a high VT/fP at baseline (92 mL·cm−3), high specific binding to TSPO (95.6%), and a high BPND (8.1). For these 3 radioligands, VT reached 90% of terminal 120-min values by 70 min and remained relatively stable thereafter, with excellent identifiability (%SE < 5%), suggesting that no significant radiometabolites accumulated in the brain.

In the present study, LGA was used to quantify and compare brain uptake across all 6 radioligands because neither the 1- nor the 2-tissue-compartment models fitted perfectly for all studies. With LGA, VT was quantified with excellent identifiability (SE < 10%) in all baseline and preblocked studies. Logan-derived VND/fP and BPND were within acceptable ranges and became less variable within each of the fluoro and trifluoromethyl radioligands. However, LGA tends to underestimate VT and BPND, typically by 10%–20% depending on both the noise level and the radioligand concentration (19,20). The degree of underestimation in this study remains uncertain; however, given the same target (TSPO) and similar performance measures, we believe that the underestimation, if any, would have been consistent across all 6 radioligands and would have led to the same finding—that is, that the o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro analogs were the 3 best candidates.

Evaluation of VT stability with respect to scan duration allows one to determine the minimum scan time required for obtaining a stable VT and to indirectly check the possibility that radiometabolites are accumulating in the brain. Acceptable scan durations typically occur when VT in all regions approaches 10% of a terminal value. If brain-penetrant radiometabolites accumulate in the brain, VT is expected to increase continuously, making the values unlikely to plateau and stabilize. Whether radiometabolites enter and accumulate in the brain is critical for imaging human TSPO, especially in LABs who have low specific binding. Although some small differences were noted between the radioligands, the present study found that, for all 6 radioligands, whole-brain VT at baseline reached 10% of the terminal value by 70 min and 5% by 90 min. This similarity in time stability suggests that radiometabolites are unlikely to have interfered with brain uptake.

Interestingly, the present study found that ex vivo blood cells were a useful surrogate for brain tissue. VBC at baseline and under preblocked conditions and the percentage blockade by PK11195 correlated well with those of whole-brain VT/fP. The similarity between the 2 organs can be used to evaluate radioligands that specifically bind to receptors expressed in both the brain and blood cells. For example, the blood cell analysis could be used as a quick screening tool for candidate radioligands or a nonimaging supplement to validate imaging results, thus aiding the development of new PET radioligands. However, the utility of ex vivo blood cells should be verified for individual radioligands because the 2 organs differ in their efflux systems and compartmental configurations.

One of the advantages of 11C-ER176 is that it has adequately high TSPO-specific binding for quantification across all rs6971 genotypes. A previous postmortem analysis of human brain tissue measured the in vitro binding affinities to all rs6971 genotypes for ER176 and these 6 fluorine-containing analogs (8,10). As summarized in Table 1, the p-trifluoromethyl compound showed the smallest ratio (i.e., binding affinity difference) (0.8) between high-affinity binders and LABs, followed by ER176 (1.3), the m-trifluoromethyl (2.0) compound, the 3 fluoro compounds (2.7–2.9), and the o-trifluoromethyl (5.4) compound. Building on this finding, all 6 analogs investigated here are expected to achieve an adequately high specific signal in LABs, at least higher than PBR28 (55.0) (5), which has been the most widely used of the second-generation TSPO radioligands.

Taken together, these in vitro and in vivo data suggest that the o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro compounds appear to be the most promising analogs. However, all 6 radioligands performed well and with only small interligand differences (Table 1). For example, the 3 fluoro radioligands exhibited similar BPND (4.8–12.1), time stability of VT (all achieved stable VT by 70 min), and binding affinity ratios (2.7–2.9), and all these measures were comparable to those of 11C-ER176. Nevertheless, unexpected labeling issues (e.g., unsatisfactory yield, or perhaps only marginally acceptable molar activity for labeling trifluoromethyl groups) for 18F radioligands may also arise in their development, limiting the use of particular radioligands despite solid performance in their 11C-labeled forms. Thus, though the candidate radioligands have now been ranked, priorities for subsequent 18F radiolabeling will also be affected by the time and effort needed for radiochemistry. Moving forward, none of the 6 compounds will be excluded.

The underlying assumption of this study is that 18F-labeled radioligands will perform similarly to their 11C-labeled versions. However, the performance of an 11C-labeled radioligand does not always guarantee success in its 18F-labeled form. 18F labeling at a position different from an 11C position in the molecular structure may change the spectrum of radiometabolites and generate unexpected brain-penetrating radiometabolites. Defluorination may also occur to confound the accurate quantification of receptor-specific brain uptake. Although strategic positioning of an 18F label can reduce the production of these troublesome radiometabolites, the in vivo metabolism of a radioligand (e.g., the sites of metabolic cleavage) is not always predictable and further varies across species (21).

CONCLUSION

The 6 fluorine-containing analogs of ER176 were relatively easily labeled with 11C. PET imaging in the monkey brain showed that all 6 11C-labeled analogs had a good BPND and good time stability of VT. Of the 6 ligands, the o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro compounds were arguably the 3 best candidates to radiolabel with 18F, a process that is expected to be quite challenging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the dedicated staff of the Molecular Imaging Branch of the NIMH, the PET Department of the NIH Clinical Center, and the NIMH veterinary staff for help in completing the studies.

DISCLOSURE

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (ZIAMH002795 and ZIAMH002793). No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Which are the most promising fluorine-containing analogs of 11C-ER176 for subsequent 18F radiolabeling?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: This study used generic 11C labeling and in vivo performance in the monkey brain—BPND and time stability of VT—to select the most promising analogs among 6 candidates. The o-fluoro, m-trifluoromethyl, and m-fluoro compounds were arguably the 3 best candidates because they showed the 3 highest BPND values as well as good time stability of VT.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: The development of an 18F-labeled radioligand based on 11C-ER176 would allow greater flexibility and more widespread use of TSPO PET.

REFERENCES

- 1. Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, et al. Translocator protein (18kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyer JH, Cervenka S, Kim MJ, Kreisl WC, Henter ID, Innis RB. Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: PET imaging and promising new targets. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:1064–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chauveau F, Boutin H, Van Camp N, Dolle F, Tavitian B. Nuclear imaging of neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review of [11C]PK11195 challengers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2304–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Le Fur G, Perrier ML, Vaucher N, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites: effect of PK 11195, 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide. I. In vitro studies. Life Sci. 1983;32:1839–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kreisl WC, Jenko KJ, Hines CS, et al. A genetic polymorphism for translocator protein 18 kDa affects both in vitro and in vivo radioligand binding in human brain to this putative biomarker of neuroinflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kreisl WC, Kim MJ, Coughlin JM, Henter ID, Owen DR, Innis RB. PET imaging of neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:940–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ikawa M, Lohith TG, Shrestha S, et al. 11C-ER176, a radioligand for 18-kDa translocator protein, has adequate sensitivity to robustly image all three affinity genotypes in human brain. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujita M, Kobayashi M, Ikawa M, et al. Comparison of four 11C-labeled PET ligands to quantify translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) in human brain: (R)-PK11195, PBR28, DPA-713, and ER176-based on recent publications that measured specific-to-non-displaceable ratios. EJNMMI Res. 2017;7:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siméon FG, Lee JH, Morse CL, et al. Synthesis and screening in mice of fluorine-containing PET radioligands for TSPO: discovery of a promising 18F-labeled ligand. J Med Chem. 2021;64:16731–16745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zanotti-Fregonara P, Zhang Y, Jenko KJ, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of translocator 18 kDa protein (TSPO) positron emission tomography (PET) radioligands with low binding sensitivity to human single nucleotide polymorphism rs6971. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:963–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . 8th ed. National Academy Press; 2011. [PubMed]

- 13. Zoghbi SS, Shetty HU, Ichise M, et al. PET imaging of the dopamine transporter with 18F-FECNT: a polar radiometabolite confounds brain radioligand measurements. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gandelman MS, Baldwin RM, Zoghbi SS, Zea-Ponce Y, Innis RB. Evaluation of ultrafiltration for the free-fraction determination of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radiotracers: beta-CIT, IBF, and iomazenil. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yasuno F, Brown AK, Zoghbi SS, et al. The PET radioligand [11C]MePPEP binds reversibly and with high specific signal to cannabinoid CB1 receptors in nonhuman primate brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kanegawa N, Collste K, Forsberg A, et al. In vivo evidence of a functional association between immune cells in blood and brain in healthy human subjects. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;54:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Briard E, Zoghbi SS, Imaizumi M, et al. Synthesis and evaluation in monkey of two sensitive 11C-labeled aryloxyanilide ligands for imaging brain peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in vivo. J Med Chem. 2008;51:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Ding YS, Wang GJ, Alexoff DL. A strategy for removing the bias in the graphical analysis method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slifstein M, Laruelle M. Effects of statistical noise on graphic analysis of PET neuroreceptor studies. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:2083–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pike VW. PET radiotracers: crossing the blood-brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]