Abstract

A Staphylococcus xylosus C2A gene cluster, which encodes enzymes in the pathway for choline uptake and dehydrogenation (cud), to form the osmoprotectant glycine betaine, was identified. The cud locus comprises four genes, three of which encode proteins with significant similarities to those known to be involved in choline transport and conversion in other organisms. The physiological role of the gene products was confirmed by analysis of cud deletion mutants. The fourth gene possibly codes for a regulator protein. Part of the gene cluster was shown to be transcriptionally regulated by choline and elevated NaCl concentrations as inducers.

Among the nonhalophilic eubacteria, the members of the genus Staphylococcus are distinguished by their ability to cope with a broad range of osmotic pressures in their environment. For example, Staphylococcus aureus is able to survive in media with moderate salt concentrations as well as under high salt conditions up to 3.5 M NaCl (6). This indicates that these bacteria possess an effective and well-regulated mechanism to protect themselves from the detrimental effects of high osmolarities.

In many organisms, osmotolerance is mediated by compatible solutes or osmoprotectants that can be accumulated intracellularly to counterbalance elevated osmolarities in the environment without affecting cell metabolism (4). Among these substances, glycine betaine is one of the most-effective compounds. Many bacteria are able to accumulate glycine betaine via uptake systems or by de novo synthesis with choline as the precursor (4). To date, the osmoregulatory role of choline and its derivative glycine betaine has been investigated exclusively on the physiological level in staphylococci. Choline enters the staphylococcal cell by a specific uptake system (8) and is subsequently converted to glycine betaine, a potent osmoprotectant in S. aureus (6). The genetic basis for choline uptake and dehydrogenation has been elucidated for Escherichia coli (11) and recently for Bacillus subtilis (1). In E. coli, a gene cluster comprises the genes encoding a choline transporter (BetT), two dehydrogenases, an NADH-dependent glycine betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BetB), and an FADH-dependent choline dehydrogenase (BetA), which are responsible for the conversion of choline to glycine betaine aldehyde. In addition, a regulatory protein, BetI, is encoded by the E. coli bet gene cluster; BetI binds to the DNA region between the betIBA operon and the betT gene and is responsible for the choline-dependent regulation of bet transcription (12, 21). In B. subtilis, an operon encodes two dehydrogenases, a glycine betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (GbsA) that shows similarity to glycine betaine aldehyde dehydrogenases found in various other organisms, and a choline oxidase (GbsB) that belongs to a family of alcohol dehydrogenases and thus represents a novel type of choline-dehydrogenating enzyme involved in glycine betaine biosynthesis. In contrast to E. coli, no genes for a choline transporter or a regulatory protein have been identified in the gbs locus (1).

In this study, we identified and characterized a staphylococcal gene cluster encoding the biosynthesis pathway for choline uptake and conversion to glycine betaine. This is the first presentation of genetic data on glycine betaine synthesis in a member of the halotolerant genus Staphylococcus.

Cloning and characterization of the cud gene cluster.

Part of the cud gene cluster was identified on a 5.5-kb XbaI fragment (see Fig. 1A) in a gene bank of S. xylosus genomic DNA which was cloned in E. coli DH5α (Gibco-BRL, Eggenstein, Germany) with pBLUESCRIPT II KS+ (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) as the vector. The fragment was accidentally detected as a false-positive signal in a screening of the gene bank by Southern blot analysis with a radiolabelled wobble oligonucleotide derived from an exoprotein of S. xylosus C2A. To complete the gene cluster, another 1.3-kb XbaI-BamHI fragment of S. xylosus chromosomal DNA was cloned and inserted into pRB473, a derivative of pRB373 (3), together with the 5.5-kb XbaI fragment, leading to the construction of pRBcud which carries the complete cud gene cluster (Fig. 1A).

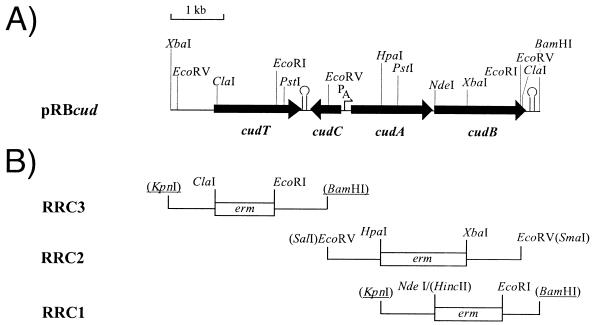

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction map of the 6.8-kb chromosomal DNA fragment of the S. xylosus cud locus cloned in pRB473. The location and orientation of the cud genes are indicated by arrows. Hairpin symbols indicate putative transcriptional terminators. PA, cudA promoter. (B) Physical maps of plasmid constructions used for replacing genes by homologous recombination. The location of the erm cassette is indicated by a box (not drawn to scale). Restriction sites of vector pBT2 are given in parentheses. Those sites introduced by intermediate cloning into pEC4 are in parentheses and are underlined.

The inserted DNA was sequenced by the dideoxy chain-termination method (22) according to a cycle sequencing protocol using Thermosequenase (Amersham) and fluorescence-labeled primers. Sequencing reactions were analyzed with the DNA sequencer model 4000L (LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, Neb.).

The sequenced region comprised 6874 nucleotides and revealed four open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1A). The ORFs that encoded gene products with similarities to proteins responsible for uptake and dehydrogenation of choline were designated cudT, cudA, and cudB. The derived gene product of the fourth ORF, cudC, revealed no similarity to proteins known to be involved in the biosynthesis of glycine betaine.

cudT starts with an ATG codon at bp 811 and ends at a TAA codon at nucleotide 2431, thereby encoding a protein of 540 amino acids (60.0 kDa). Immediately downstream of cudT is a transcription terminator-like structure. Divergently oriented with respect to cudT is cudC, which starts at nucleotide 3164 with a TTG codon and ends at bp 2606 with a TAA codon. The corresponding gene product is 186 amino acids long (21.6 kDa). The cudA gene, starting at position 3363 (ATG), is in the same orientation as cudT and ends at position 4854 with a TAA codon. cudA encodes a protein of 497 amino acids (54.8 kDa). cudB, in the same orientation as cudA, starts at bp 4915 with an ATG codon and ends at bp 6595 (TAA), thus encoding a protein of 560 amino acids (62.4 kDa). cudB is also followed by a transcription terminator-like structure. No such secondary structure is found in the intergenic region between cudA and cudB, which indicates that the two genes are probably transcribed as a polycistronic mRNA.

Database comparisons of the S. xylosus C2A Cud proteins.

CudT shows similarities to transport proteins involved in the uptake of compatible solutes. Among the most similar sequences are the high-affinity choline uptake system of E. coli, BetT (11); the glycine betaine uptake systems of B. subtilis, OpuD (9), and Corynebacterium glutamicum, BetP (19); and a carnitine transporter of E. coli, CaiT (5). Computer-aided searching for membrane-spanning domains according to the positive-inside rule (23) predicted twelve membrane-spanning helices for CudT, indicating that it is an integral membrane protein.

The gene product of the cudA gene reveals a striking similarity to betaine aldehyde dehydrogenases from bacteria and plants. It shows the highest similarity to the GbsA protein of B. subtilis (65% identity), which is involved in the biosynthesis of glycine betaine (1). Significant similarities were also found to betaine aldehyde dehydrogenases from plants, such as Spinacia oleracea (44% identity), Beta vulgaris (45% identity), Amaranthus hypochondriacus (45% identity), Oryza sativa (46% identity), and Atriplex hortensis (44% identity) (13, 17, 18, 24, 25).

For CudB, the highest similarities were found to choline dehydrogenases, such as the BetA protein of E. coli (49% identity) and choline dehydrogenases from Caenorhabditis elegans (46% identity), Sinorhizobium meliloti (45% identity), and Rattus rattus (45% identity) (11, 16, 20).

CudC exhibits no similarity to proteins with known function, but CudC has a striking similarity (54% identity) to the gene product of orf-2, which is located upstream of the B. subtilis gbsAB operon (1) and 29% identity to a 180-amino-acid protein encoded by an ORF located upstream of the B. subtilis opuB genes, which code for a choline uptake system (10). The function of this latter protein is unknown, but an analysis of the primary structure revealed a helix-turn-helix motif between amino acids 52 and 71, suggesting a regulatory function. Interestingly, an identical protein is also encoded by an ORF upstream of a chimeric proU operon in B. subtilis (14), which is involved in glycine betaine uptake. According to these similarities, we propose a regulatory role for CudC.

CudA and CudB catalyze the conversion of choline to glycine betaine. (i) Construction of S. xylosus cudAB mutants.

In order to verify a physiological function for CudA and CudB, we constructed S. xylosus mutants by replacing the wild-type cudAB genes with an erythromycin resistance cassette (erm) by homologous recombination. For that purpose, fragments of the cud gene cluster were eliminated as indicated in Fig. 1B and replaced by the erm gene of plasmid pEC4. The resulting constructs were inserted into the temperature-sensitive shuttle vector pBT2 and transformed into S. xylosus C2A. The gene replacement procedure used was the method of Brückner (2).

In mutant S. xylosus RRC2, cudA and cudB were inactivated by replacement of a 1.6-kb HpaI-XbaI fragment with the erythromycin resistance marker (Fig. 1B). In S. xylosus RRC1, a 1.2-kb NdeI-EcoRI fragment of the cudB gene was replaced, leaving the cudA gene unchanged (Fig. 1B). The site of insertion of the erm cassette was verified by DNA sequencing using erm-specific sequencing primers.

(ii) Growth experiments.

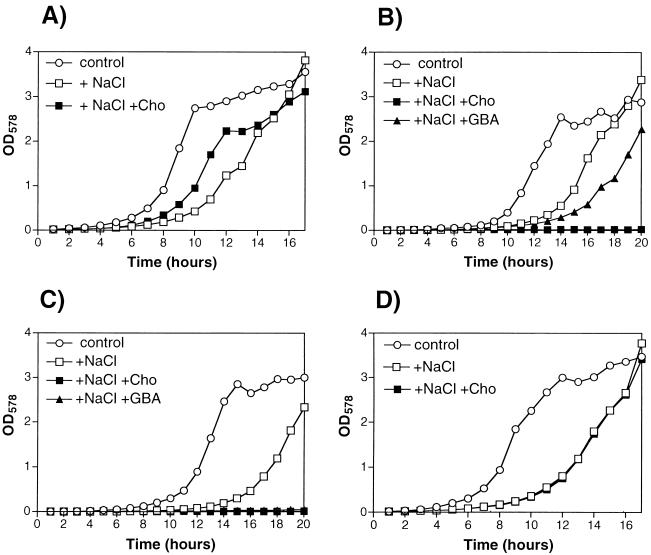

The wild-type strain C2A and the mutants RRC1 and RRC2 were cultivated in a defined medium with low or high osmolarity in the presence or absence of choline or glycine betaine aldehyde (Fig. 2). In this defined medium, S. xylosus C2A was able to grow in NaCl concentrations up to 2.0 M without any osmoprotective substance added and up to 2.5 M NaCl in the presence of glycine betaine (data not shown). For studying growth under hyperosmotic conditions and the effect of osmoprotectants, we chose a salt concentration of 1.5 M. Under these conditions, the entrance of S. xylosus C2A into the exponential growth phase was retarded by about 4 h (Fig. 2A). In the presence of choline, the lag phase was significantly reduced, which demonstrated the osmoprotective effect of choline for S. xylosus C2A (Fig. 2A). Addition of glycine betaine to cultures containing high salt concentrations resulted in growth comparable to that of the control culture (data not shown). The final optical densities of the cultures were not significantly influenced by hyperosmolarity, either in the absence or presence of choline (Fig. 2A). When RRC1 was cultivated in high-salt medium without choline or glycine betaine aldehyde added, the same retarded onset of growth was observed as with the wild-type strain. However, in contrast to the wild type, choline not only had no osmoprotective effect on mutant RRC1 but caused a complete inhibition of growth (Fig. 2B). With glycine betaine aldehyde, mutant RRC1 was able to grow but with a significantly extended lag phase (Fig. 2B). The growth behavior of the cudAB mutant RRC2 was similar to that of mutant RRC1, with the exception that not only choline but also glycine betaine aldehyde caused a complete inhibition of growth (Fig. 2C). The toxic effect of choline on mutants RRC1 and RRC2 supports the assumption that CudB represents a choline dehydrogenase, since the cudB gene was inactivated in both mutants. The different effects of glycine betaine aldehyde on the growth of the two mutants is consistent with the assumption that CudA is a glycine betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase that is not affected by gene replacement in mutant RRC1 and thus permits growth in the presence of the toxic compound, in contrast to mutant RRC2 in which both genes are affected. An inhibitory effect of choline and its dehydrogenated derivative glycine betaine aldehyde has also been reported for B. subtilis mutants with defects in the choline-converting pathway encoded by the gbsAB operon (1). Growth inhibition of the cudAB mutants by choline was dependent on the salt concentration in the medium. Full inhibition of growth occurred only at NaCl concentrations above 1 M (data not shown). This suggests that choline uptake by S. xylosus is dependent on elevated osmolarities.

FIG. 2.

Growth of S. xylosus C2A (A) and cud mutants RRC1 (ΔcudB::erm) (B), RRC2 (ΔcudAB::erm) (C), and RRC3 (ΔcudT::erm) (D) in defined medium (Na2HPO4 · 2H2O [8.90 g/liter], KH2PO4 [6.80 g/liter], MgSO4 · 7H2O [200 mg/liter], NH4Cl [500 mg/liter], NaCl [500 mg/liter], glycine [1.0 g/liter], sodium citrate [3.0 mg/liter], nicotinic acid [0.2 mg/liter], pantothenate [0.2 mg/liter], thiamine [0.2 mg/liter], FeCl2 · 4H2O [1.5 mg/liter], ZnCl2 [0.07 mg/liter], MnCl2 · 4H2O [0.1 mg/liter], boric acid [0.006 mg/liter], CoCl2 · 6H2O [0.19 mg/liter], CuCl2 · 2H2O [0.002 mg/liter], NiCl2 · 6H2O [0.024 mg/liter], Na2MoO4 · 2H2O [0.036 mg/ml], 0.5% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, [pH 7.0]). Growth was assayed in the presence or absence of 1.5 M NaCl with or without choline or glycine betaine aldehyde. Media (50 ml) were inoculated with 1/200 volume of a culture grown overnight and incubated at 37°C for the indicated time. Growth was monitored spectrophotometrically (optical density at 578 nm [OD578]). Cho, choline (1 mM); GBA, glycine betaine aldehyde (1 mM); control, growth in defined medium without NaCl and osmoprotectant added.

(iii) Choline conversion assay.

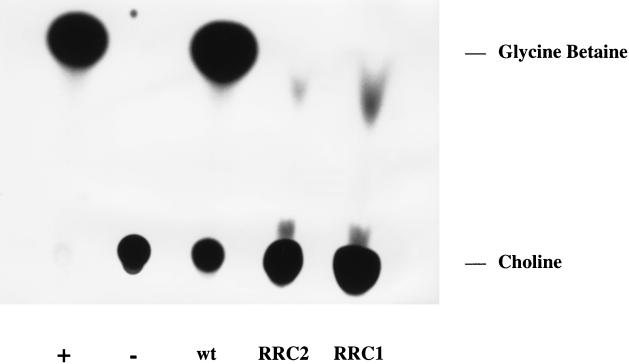

In order to verify whether cudA and cudB encode dehydrogenases that convert choline to glycine betaine, in vitro assays with S. xylosus C2A, RRC1, and RRC2 with [14C]choline as the substrate were performed. For the determination of glycine betaine formation, the strains were incubated overnight with [14C]choline and subsequently were assayed for choline conversion by thin-layer chromatography of the cell extracts (Fig. 3). With S. xylosus C2A, the distribution of the radioactivity in the chromatogram is comparable to that in the positive control, indicating that glycine betaine was formed from choline by the wild-type strain. In contrast, with the extracts of S. xylosus RRC1 and RRC2, most of the radioactivity remained at the spots where the samples had been applied (Fig. 3). In contrast to the negative control, the mutant extracts show additional faint dots with migration distances different from those of choline and glycine betaine. The nature of these spots is unknown, but they obviously do not represent choline or glycine betaine. The lack of conversion of choline to glycine betaine by the mutants again supports the proposed roles for CudA and CudB as dehydrogenases involved in glycine betaine formation and demonstrates their essentialness for choline utilization by S. xylosus.

FIG. 3.

Assay for choline conversion by S. xylosus C2A (wild type [wt]), RRC1, and RRC2. Cultures were grown in 1 ml of defined medium with 0.5 M NaCl and 36.4 μM [methyl-14C]choline (55.0 mCi/mmol; Amersham Life Science, Braunschweig, Germany) for 16 h at 37°C. The cells were harvested, lysed by treatment with 50 μl of lysostaphin solution (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 10 min at 37°C, and 5 μl of the lysates were separated by thin-layer chromatography on Silica Gel G thin-layer plates (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) with methanol–0.88 M ammonia (75:25) as the solvent system. For a positive control, we used [14C]glycine betaine produced from [14C]choline by incubation with choline oxidase from Aspergillus species. After separation, the chromatogram was analyzed by autoradiography. +, positive control ([14C]glycine betaine formed by incubation of [14C]choline with choline oxidase); −, negative control (same sample as positive control but no choline oxidase added). (This figure was produced with Adobe Photoshop 5.0 for MacOS.)

cudT encodes a choline transporter. (i) Construction of a cudT mutant.

In order to clarify whether the cudT gene encodes a choline transporter, as expected from the similarities to other transport proteins, we constructed a mutant strain, S. xylosus RRC3, in which a 1.26-kb ClaI-EcoRI fragment comprising the gene almost completely was replaced by the erm cassette (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the wild-type strain, this mutant retained a prolonged lag phase when grown in the presence of choline at high salt conditions (Fig. 2D). The lack of a beneficial effect of choline for S. xylosus RRC3 suggests that this mutant is unable to take up choline from the medium, which is in agreement with the assumption that cudT encodes a choline uptake system.

(ii) [14C]choline uptake assays.

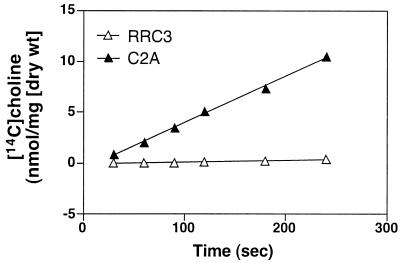

To demonstrate the physiological role for CudT directly, we performed [14C]choline uptake assays with the wild-type and mutant RRC3 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of [14C]choline uptake by S. xylosus C2A and mutant RRC3 (ΔcudT::erm). Cells were grown in defined medium with 0.5 M NaCl and 1 mM choline to an optical density at 578 nm (OD578) of 0.5. The cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in transport buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 20 mM glucose, 0.75 M NaCl) to an OD578 of 1.0. One milliliter of the cell suspension was used in the transport assays, which were performed at 30°C. At time point zero, 54.5 nmol of [methyl-14C]choline (55.0 mCi/mmol; Amersham Life Science) was added. At the times indicated, 150-μl aliquots were sampled and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany); the captured cells were washed with 5 ml of transport buffer, and cell-associated radioactivity was measured in a Beckman LS-6000TA scintillation counter.

We first tested the influence of different growth and transport assay conditions on the choline uptake rates of S. xylosus C2A. The highest transport activities were observed when the cells were grown in the presence of choline and elevated NaCl concentrations and when the assays were performed in high-salt buffer (data not shown). Under these conditions, the wild-type strain accumulated choline with an uptake rate of 2.53 nmol · (mg [dry weight])−1 · min−1. Mutant RRC3 accumulated choline with a drastically reduced rate of 0.1 nmol · (mg [dry weight])−1 · min−1, which corresponds to about 4% of the wild-type uptake rate (Fig. 4A). This clearly demonstrated that CudT is involved in choline uptake.

Analysis of cudA transcription.

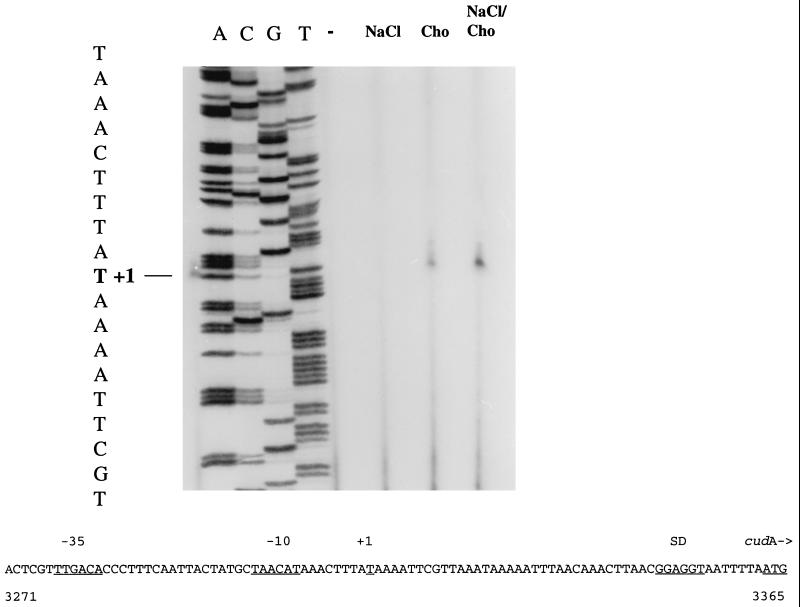

In order to localize the transcriptional start of the cudA gene and to test whether this gene is regulated on the transcriptional level, we performed primer extension analysis with total RNA from S. xylosus C2A (Fig. 5). One extension product was detected in the autoradiograph and corresponded to a T at position 3315 of the nucleotide sequence. This nucleotide is located 48 nucleotides upstream of the cudA start codon. Upstream of the transcription start site, putative −10 and −35 sequences were detected; the −35 region corresponded perfectly with the corresponding consensus sequence of E. coli and B. subtilis vegetative promoters (7, 15), while the −10 sequence differed in two positions from the canonical sequence. The regions are separated by 18 nucleotides. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the strongest signal was observed when the cells were grown in the presence of choline and 1.5 M NaCl. With choline alone, the amount of extension product was slightly lower. RNA from cells cultivated with or without 1.5 M NaCl and no choline added yielded no detectable signals in the primer extension experiment. Thus, choline is the main inducing factor of cudA expression (and probably cudB expression, since the two genes are believed to form an operon).

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of cudA transcription. Total RNA was isolated from S. xylosus C2A cells grown in defined medium to an optical density at 578 nm (OD578) of 1.0 without any supplement (−), with 1.5 M NaCl (NaCl), with 1 mM choline (Cho), or with 1.5 M NaCl and 1 mM choline (NaCl/Cho). Twenty micrograms of each preparation was used for primer extension with a cudA-specific primer (5′-CTTTATTTGAGCTTTCAACC-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 3432 to 3413 of the cud sequence). Half of each reaction mixture was loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel together with a sequencing reaction performed with the same primer. The sequence of the template strand is given to the left of the gel. The transcriptional start is indicated by +1. At the bottom, part of the sequence from positions 3271 to 3365, containing the cudA promoter, is shown. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD), the start codon of cudA, and the putative −10 and −35 sequences are underlined.

We also attempted to map the start points of the transcripts of cudT and cudC by using the same RNA preparations as used for the analysis of the cudA transcript. We obtained no signals in the primer extension experiments, which indicates that these genes might be transcribed at a significantly lower level than the cudAB genes. Lower expression levels of betI of E. coli have been found; betI is expressed at only 10% of the level of that of the betA and betB genes (21). Low levels of expression of cudC and cudT are not unexpected if CudC is a regulatory protein and CudT is an integral membrane protein.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence determined in this study has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AF009415.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen A. Brune for critical reading of the manuscript and Vera Augsburger and Regine Stemmler for skillful technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 323).

REFERENCES

- 1.Boch J, Kempf B, Schmid R, Bremer E. Synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of the gbsAB genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5121–5129. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5121-5129.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brückner R. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;151:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brückner R. A series of shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. Gene. 1992;122:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90048-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csonka L N, Hanson A D. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:569–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichler K, Bourgis F, Buchet A, Kleber H-P, Mandrand-Berthelot M-B. Molecular characterization of the cai operon necessary for carnitine metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:775–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Staphylococcus aureus osmoregulation: roles for choline, glycine betaine, proline, and taurine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2711–2716. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2711-2716.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helman J D. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigmaA-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2351–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.13.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaenjak A, Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Choline transport activity in Staphylococcus aureus induced by osmotic stress and low phosphate concentrations. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2400–2406. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2400-2406.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappes R M, Kempf B, Bremer E. Three transport systems for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine operate in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of OpuD. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5071–5079. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5071-5079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappes, R. M., B. Kempf, S. Kneip, J. Boch, J. Gade, and E. Bremer. 1998. GenBank entry, accession no. AF008930.

- 11.Lamark T, Kaasen I, Eshoo M W, Falkenberg P, McDougall J, Strom A R. DNA sequence and analysis of the bet genes encoding the osmoregulatory choline-glycine betaine pathway of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1049–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamark T, Rokenes T P, McDougall J, Strom A. The complex bet promoters of Escherichia coli: regulation by oxygen (ArcA), choline (BetI), and osmotic stress. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1655–1662. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1655-1662.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legaria, J. P., and G. Iturriaga. 1997. Swiss-Prot entry, accession no. O04895.

- 14.Lin Y, Hansen J N. Characterization of a chimeric proU operon in a subtilin-producing mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6874–6880. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6874-6880.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisser S, Margalit H. Compilation of E. coli mRNA promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1507–1516. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeffler, M. 1994. EMBL entry, accession no. X94769.

- 17.McCue K F, Hanson A D. Salt-inducible betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase from sugar beet: cDNA cloning and expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00018451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura T, Yokota S, Muramoto Y, Tsutsui K, Oguri Y, Fukui K, Takabe T. Expression of a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in rice, a glycine betaine nonaccumulator, and possible localization of its protein in peroxisomes. Plant J. 1997;11:1115–1120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11051115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peter H, Burkovski A, Krämer R. Isolation, characterization, and expression of the Corynebacterium glutamicum betP gene, encoding the transport system for the compatible solute glycine betaine. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5229–5234. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5229-5234.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocard J A, Vincent N, Boncompagni E, Smith L T, Poggi M C, Le Rudulier D. Molecular characterization of the bet genes encoding glycine betaine synthesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti 102F34. Microbiology. 1997;143:1369–1379. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rokenes T P, Lamark T, Strom A R. DNA-binding properties of the BetI repressor protein of Escherichia coli: the inducer choline stimulates BetI-DNA complex formation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1663–1670. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1663-1670.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Heijne G. Membrane protein structure prediction: hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90934-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weretilnyk E A, Hanson A D. Molecular cloning of a plant betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase, an enzyme implicated in adaptation to salinity and drought. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2745–2749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao G, Zhang G, Liu F, Chen S. Study on BADH gene from Atriplex hortensis. Chin Sci Bull. 1995;40:741–745. [Google Scholar]