Abstract

Introduction

Community-integrated care initiatives are increasingly being used for social and health service delivery and show promising outcomes. Nevertheless, it is unclear what structures and underlining causal agents (generative mechanisms) are responsible for explaining how and why they work or not.

Methods and analysis

Critical realist synthesis, a theory-driven approach to reviewing and synthesising literature based on the critical realist philosophy of science, underpinned the study. Two lenses guided our evidence synthesis, the community health system and the patient-focused perspective of integrated care. The realist synthesis was conducted through the following steps: (1) concept mining and framework formulation, (2) searching for and scrutinising the evidence, (3) extracting and synthesising the evidence (4) developing the narratives from causal explanatory theories, and (5) disseminate, implement and evaluate.

Results

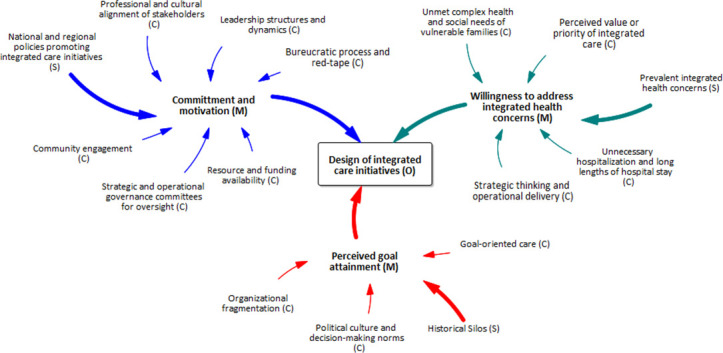

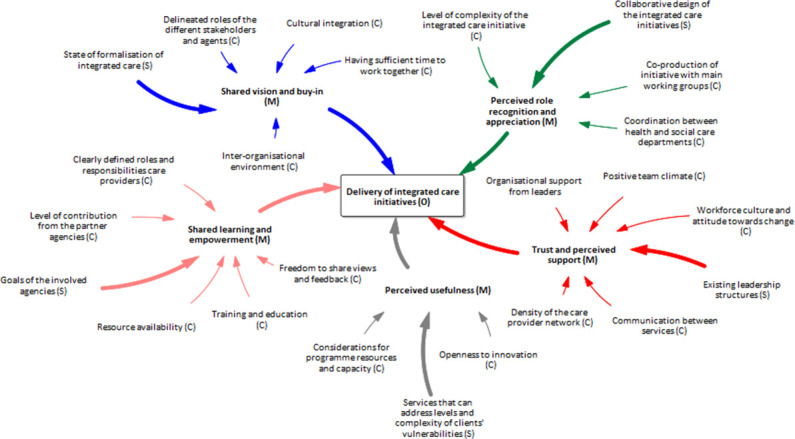

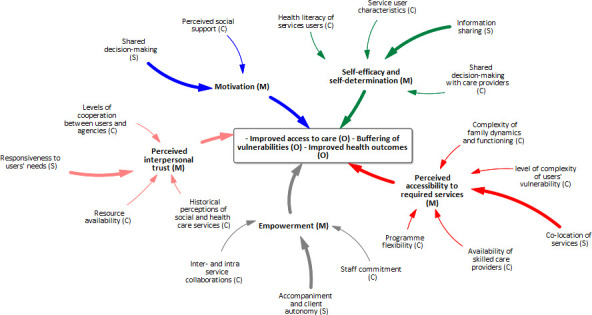

Three programme theories, each aligning with three groups of stakeholders, were unearthed. At the systems level, three bundles of mechanisms were identified, that is, (1) commitment and motivation, (2) willingness to address integrated health concerns and (3) shared vision and goals. At the provider level, five bundles of mechanisms critical to the successful implementation of integrated care initiatives were abstracted, that is, (1) shared vision and buy-in, (2) shared learning and empowerment, (3) perceived usefulness, (4) trust and perceived support and (5) perceived role recognition and appreciation. At the user level, five bundles of mechanisms were identified, that is, (1) motivation, (2) perceived interpersonal trust, (3) user-empowerment, (4) perceived accessibility to required services and (5) self-efficacy and self-determination.

Conclusion

We systematically captured mechanism-based explanatory models to inform practice communities on how and why community-integrated models work and under what health systems conditions.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020210442.

Keywords: Health systems, Health services research, Review

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Community-integrated care initiatives are designed to better co-ordinate care around people’s needs.

Community-integrated care initiatives are increasingly being used for social and health service delivery and show promising outcomes.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Causality-based explanatory models constructed through the integration of community health systems and patient-centred lenses to capture the complexity around the design, implementation and uptake of community-integrated care initiatives.

Unpacks and causally links the existing structures, relevant context conditions, and generative mechanisms critical to the design, implementation, and uptake of community-based integrated initiatives.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The generative mechanisms, relevant structures and influential contextual elements can provide guidance to the critical elements required for the successful design, implementation and uptake of community-integrated care initiatives.

Introduction

Integrated service delivery initiatives are increasingly being identified and adopted to address the multifactorial and dynamic causes of ill health and ill-being across the globe. Integrated care is the inclusion of a range of different care services to achieve better social and health outcomes.1 In this perspective, integrated care is a coherent set of methods and models for funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the care and cure sectors.2 Goodwin defines it as ‘a broad and multicomponent set of ideas and principles that seek to better co-ordinate care around people’s needs’.3

Integrated care approaches strive to overcome care fragmentation, especially in situations where fragmented service delivery adversely impacts clients’ care experiences and outcomes.3 Community-based integrated care initiatives are those that are based primarily in the community and aim to engage clients with primary healthcare and community services while using hospital services in an appropriate manner.4 Leutz5 observed that community-based integrated care approaches may be best suited to people living with poor socioeconomic determinants of health with medically complex or long-term care needs. The level, type and combination of strategies used while designing a community-based integrated care initiative would depend on the characteristics of the patient population and the specific challenges they face to obtain appropriate quality care.5

Owing to their multidimensional design and service provision structure, community-based integrated care delivery models provide more comprehensive services to improve the care of families with complex health and social needs. There is an increasing evidence indicating that community-based integrated care models reduce avoidable hospital admissions.6 From a health and social systems perspective, community-based integrated care services can reduce costs accrued from delivering inappropriate and fragmented care, across hospital and primary care services.7 In addition, integrated care including community-based initiatives strive to enhance quality and provide a better service experience—more sensitive to the personal circumstances and wishes of the individual client and their family.2 The goal of adopting integrative approaches to service delivery is to enhance the quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction and system efficiency for people by cutting across multiple services, providers and settings.3

Combined medicosocial services close to home have shown to have the potential to close the significant service delivery gap and improve the uptake of healthcare services, which in turn improves population health.8 Nevertheless, such service delivery initiatives face regulatory, organisational and technical challenges. First, highly context-dependent unpredictable treatments are caused by uncertainties and interruptions typical of knowledge-intensive work. Second, the heterogeneity of available services hinders the required exchange of semantic information. Third, coordination across multiple organisations and different roles are essential. In addition, combining healthcare and social care activities provided in a specific spatiotemporal context and relational proximity, integrated and centred on the needs of the inhabitants of a territory engenders generative mechanisms to improve the health outcomes of a targeted population.9

Owing to their multidimensional, multicomponent and complex nature, community-integrated care programmes pose enormous challenges to evaluate. To this end, the ‘true’ or ‘real life’ impact of community-integrated care initiatives are difficult to determine, and the standard measures currently used to assess them do not directly assess their impact on service users and service providers. Billings et al10 confirm that there is a mismatch between the ability to capture the somewhat ‘elusive’ impact of integrated care initiatives and what could be the most appropriate way to do so. Consequently, there is advocacy for patient experiences and outcomes to be captured as measures of integration.11 Nevertheless, simply capturing patients’ experiences and outcomes will have a limited contribution to evidence-based practice that can inform the further design, implementation and uptake of community-integrated care initiatives to other relevant contexts. As such, theory-driven approaches to evaluation such as realist-informed methodologies have been proposed as suitable for the evaluation of integrated care initiatives.12

A pragmatic evaluation of a community-integrated care initiative should inform decision-makers whether the intervention has the capacity and capability to maintain service delivery, sustain (or improve) health outcomes and client experiences while minimising daily costs.13 Critical realist approaches have value in improving evidence-based practice as they can be used to study the intricacies around the design, implementation and uptake by identifying and highlighting causal claims concerning these details while retaining the notion of complexity that exists in their practical implementation.14 The dynamic learning process that can arise in conducting a realist synthesis may generate new ideas for programme development and innovation apart from what can be achieved in reviews providing a summary of quantified evidence.15

In this critical realist synthesis, we aimed to identify the causal mechanisms provided and triggered by community-integrated care initiatives within various contextual conditions in relation to hospital presentation behaviours among people with complex health and social care requirements. We sought to achieve this by gleaning and refining a priori initial programme theory on ‘how’ and ‘why’ community-integrated care initiatives improve (or not) hospital presentation behaviours among people with complex health and social care requirements. The purpose of undertaking the review is to use the reported or identified causal mechanisms—which may highlight flows and blockages in the various context conditions—to build transferable integrated theories that can inform the design, implementation, and uptake of integrated care initiatives.16

Methods

Study design

We conducted a critical realist synthesis (also known as “realist review”), a theory-driven approach to reviewing and synthesising the literature rooted in the philosophy of critical realism. Critical realist-informed research seeks to unearth the causal mechanisms and circumstances by which programmes, policies and interventions work or do not work.17 Critical realist synthesis as a method has been used to develop evidence-informed theories about the interactions between community-based integrated care mechanisms and their implementation contexts.18

As community-integrated care models strive to modify the organisation of services, it is possible to suggest that such social programmes, introduced as interventions, tend to also involve structural, cultural, agential and relational mechanisms.14 Critical realists argue for comprehensive explanations of the interactions of structure and agency,19 which are sometimes excluded or conflated in the realist synthesis practice proposed by the Realist and Meta-Narrative Evidence Syntheses—Evolving Standards project. This conflation occurs because Pawson and Tilley20 present mechanisms as a combination of reasoning and resources, which implies that they can be components of both structure and agency. This makes discerning the actual source of change challenging and may lead to ‘the intervention’ in general being designated as the main source.17

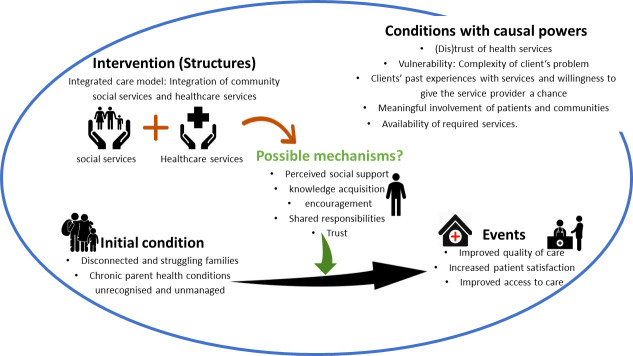

The concept of mechanisms is central to the critical realist philosophy of science. Mechanisms are typically not directly observable and are considered the underlying entities that produce specific outcomes in specific contexts. The task of conducting a realist synthesis is to mine and make explicit the underlying mechanisms that produce the ‘phenomenon and to understand the interplay between them and how they shape the outcome’.14 The elicitation of our programme theories was informed by the critical realist causality framework proposed by Sayer21 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Critical realist-informed causal configuration.

Under certain contextual conditions, the existing mechanisms and those introduced by the community-integrated care initiatives can be activated to improve hospital attendance and the uptake of healthcare services. Therefore, the identification of generative mechanisms and counteracting mechanisms requires the consideration of context elements, conditions required to determine how a mechanism empirically manifests.14 The context or condition with causal tendencies may consist of aspects of structure, culture, agency and relations (eg, individual, organisational and environmental characteristics) and historical elements that can potentially (de)activate existing or introduced mechanisms.18 22 23

The design of this synthesis was based on the realist synthesis idea proposed by Hinds and Dickson17 and steps developed by Rycroft-Malone et al.24 The steps adopted were as follows: (1) concept mining and framework formulation, (2) searching for and scrutinising the evidence, (3) extracting and synthesising the evidence (4) developing the narratives from causal explanatory theories, and (5) disseminate, implement and evaluate.24

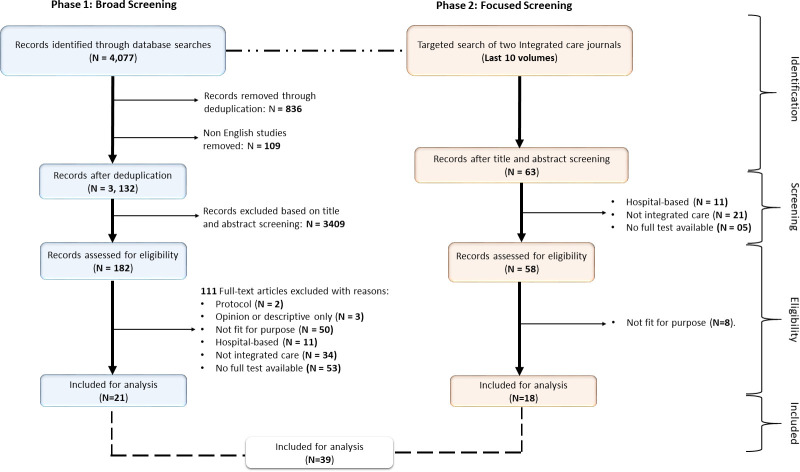

In addition to specific guidance for realist reviews, this review also drew on the six cross-cutting principles of meta-narrative reviews: pragmatism, pluralism, historicity, contestation, reflexivity and peer review25 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed iterative process for searching articles in the synthesis.28

Our realist search and review process was iterative and not as linear or rigid as a traditional systematic review.16 The following sections describe the five steps that were adopted in the review.

Step 1: clarify scope - concept mining and framework formulation

This step involved refining the review focus and purpose through initial informal searches, discussions and drawing on existing theoretical and empirical literature. We started by identifying what definition of integrated care will suit our review aims. Integrated care, which has more generalised definitions, has also been defined from four different perspectives, namely, (1) a health system-based perspective; (2) a manager’s perspective; (3) a social science perspective and (4) a patient’s perspective. After iterative discussions about the review aim and objectives, we adopted a people-centred integration care approach to the review. According to Goodwin, a people-centred integration care approach is ‘integrated care between providers and patients and other service users to engage and empower people through health education, shared decision-making, supported self-management and community engagement’(Goodwin3, p 2).

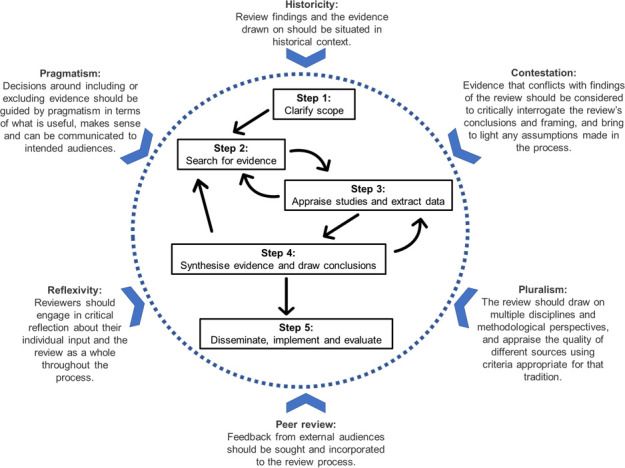

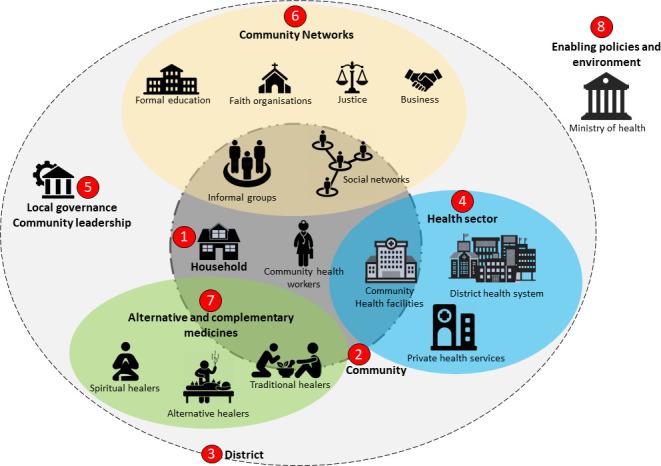

The ‘community’ is particularly relevant in integrated care given that it is their dwelling place. To explain the impact of community-integrated care initiatives using the people-centred integration care approach while maintaining the element of complexity, we incorporated two lenses to guide our evidence synthesis — (1) the community health system26 and (2) the person-focused perspective of integrated care. Our adoption of these two lenses is informed by the fact that when used to describe a person-centred care model, integrated healthcare is synonymous with a more holistic and tailored approach to patient care, one which focuses on a patient as a ‘whole person’ and incorporates more complementary services in the process (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Integration of community health systems and patient-centred lenses.

We initiated this critical realist synthesis by identifying two peer-reviewed articles through our initial scoping search to elicit the initial theories.27 The rationale for our selection was to allow us to capture the critical elements of community-based integrated care programmes that provide care to people that often have complex health and social care requirements (structures). We intended to search for those articles that could shed light on elements related to such structures, possible mechanisms and possible observed outcomes to allow us to formulate our initial programme theory through abductive thinking—a form of inventive and intuitive (‘hunch-driven’) thinking that allows a researcher to creatively imagine, for example, potential mechanisms to be investigated.28 29

The first of the two papers report on the critical realist evaluation of a community-based integrated care project, Healthy Homes and Neighbourhoods (HHAN), for vulnerable families in Sydney, Australia.30 HHAN Integrated Care Initiative was established in Sydney, Australia to improve the care of families with complex health and social needs who reside in Sydney Local Health District. HHAN was designed to provide long-term multidisciplinary care coordination to enhance capacity building and promote integrated care.30 The authors found trust, perceived support, social and organisational relationships, and client empowerment as mechanisms underpinning how HHAN worked.30 The authors also found that reluctance to engage with services was related to service (un)availability and client vulnerability; important context conditions with causal tendencies.30 This paper provided us with important information related to possible mechanisms and other conditions with causal tendencies at work in the implementation of a community-based integrated care model in Australia.

The second paper that we found useful to inform our initial programme formulation was a systematic review designed to explore the effects of integrated care models globally. The paper was focused on systematically reviewing the literature on the effects of integration or coordination between healthcare services or between health and social care on service delivery outcomes including effectiveness, efficiency and quality of care.6 The authors found perceived improved quality of care, increased patient satisfaction and improved access to care as the outcomes of various integrated care models implemented globally.6 This paper, therefore, provided us with information regarding the possible outcomes of community-based integrated care models.

With the information on the possible mechanisms and other conditions with causal tendencies at work in the implementation of a community-based integrated care model from Tennant et al30 and information regarding the possible outcomes of community-integrated care models from Baxter et al,6 we developed the following initial programme theory (Figure 4). Our initial theory was elicited based on the information obtained from these two sources through abductive thinking and retroductive theorising figure 4.15 This meant considering the outcomes of community-based integrated care interventions described in the two selected studies—presentations at hospitals and the uptake of healthcare services, and working backwards to think about the conditions of reality that are necessary for these outcomes to occur as influenced by the elements of the community-based integrated care models.15 The elements obtained from the two studies were abductively developed into a conceptual diagram informed by Sayer’s conceptualisation of critical realist causality.21 The theories were further abstracted following discussions within the author team.

Figure 4.

An initial programme theory of community-integrated care approaches.

Figure 4 illustrates the initial programme theory of community-integrated care approaches. Our initial programme theory captures how the perceptions, feelings and experiences vis-à-vis the different components of the community-based integrated care influence their hospital attendance and healthcare services uptake behaviours. This enables the review to remain open to both positive and negative, intended and emergent, and ethical or other outcomes.

Step 2: search for evidence

Searches for realist reviews are usually less formulaic and are iterative, involving multiple search strategies and approaches.31 We searched the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and the EBM reviews including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. This involved using combinations of search terms such as “integrated community care”, “non-communicable disease”, “complex health and social care requirements”, prevention and more. The search was focused on one or more integrated care health and/or social care interventions that are based in a primary care/community care setting, rather than a hospital setting.

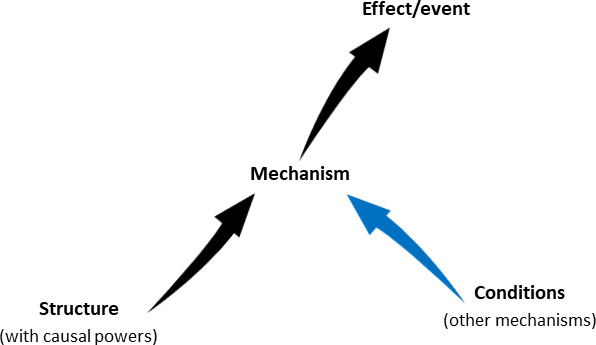

An initial search strategy using MeSH terms was conducted by two of the authors CM and PF. This process yielded 21 articles that met the inclusion criteria. Then, a second search was conducted by FCM, which was relatively narrow and targeted two Integrated care journals: Journal of Integrated Care (JICA) and The International Journal of Integrated Care (IJIC). We searched the titles and abstracts of all the 10 last volumes of JICA and IJIC from 2011 to 2021. Through the second search process, a further 18 articles were included for review. The search and screening processes are reported on a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram (figure 5).

Figure 5.

PRISMA diagram illustrating the search and screening process of relevant articles. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Our goal for information gathering was to obtain explanations based on empirical data and also on information as to how the introduction of community-integrated initiatives interact with other systems and cultural ideas to engender change.17 It is acknowledged that realist searches are likely to be iterative and responsive to emergent data.31 To this end, our study selection was purposive, meaning that the goal was not to represent the existing evidence base in its entirety, but rather only include what the authors deemed relevant for expanding, refuting or refining the initial theories.32 Initial screening of studies based on title, abstract and keywords took place simultaneously with the searches. We also considered grey literature reporting on impact evaluations, process evaluations, action research, documentary analysis, administrative records, surveys, legislative analysis, conceptual critique, personal testimony thought pieces and commentaries. The following inclusion criteria were considered:

Study design: All published study types were included.

Papers from all WHO defined regions and countries will be considered if an English language translation is available.

Publication date: Any, with priority given to more recent studies.

Document type: Any document type that informed the review, including commentaries and practice-based articles, if they come from peer-reviewed journals or reputable and relevant sources of grey literature.

Population: Multimorbidity clients enrolled in an integrated care programme that takes place in a community setting will be included. Clients can be both adults and children in the included studies.

Content: Community-integrated care initiatives that provide healthcare and social services to people that often have complex health and social care requirements.

Intervention: One or more community-integrated care initiatives.

Language: English.

Step 3: appraise studies and extract data

Data extraction and appraisal were carried out using a template that was developed and piloted specifically for this realist review, covering both any data relevant to inform the theory development and study characteristics needed for conducting a quality assessment of each study. The template and data extraction process were also informed by the realist approach to thematic analysis, which incorporates different forms of reasoning (inductive, deductive, abductive and retroductive) into the thematic analysis.33 While the use of a data extraction template resembles a codebook approach to thematic analysis, the realist approach was used to consider both manifest semantic content, such as reported outcomes, latent context and potential mechanisms.34 This enabled us to start eliciting theories already at the data extraction phase.

Further inclusions and exclusions of literature, and refinement of inclusion criteria, occurred at this point. This step of the process entailed the review team’s judgement of ‘fitness for purpose’ in relation to the review’s aims. Considerations of ‘fitness for purpose’ was be guided by the two key criteria of relevance (does the research address the review’s objectives and theories being developed?) and rigour (do the conclusions put forward by researchers or the review team hold about the data presented?).28

Step 4: synthesise evidence and draw conclusions

The process of synthesising the evidence was guided by retroductive theorising—deliberately going back to unearth the generative mechanisms and other causal conditions necessary for the observed phenomenon to occur.35 Analysis and synthesis of data extracted in the previous step were carried out through thematic analysis34 with a particular focus on abductive thinking to elicit new theories and build on the initial programme theory. Abductive thinking guided the process of postulating what mechanisms are involved in generating specific outcomes.35 First, the mechanisms were identified through clear causal linkages identified as triads (context-mechanism-outcomes) and dyads (mechanism-outcome, context-mechanism) and then as single constructs. Through retroduction, we linked the thematically obtained constructs to formulate mechanism-based explanatory models.36 Second, the countervailing mechanism identified at each level and pertaining to the identified outcomes were used to confirm the causal mechanisms that trigger the intended outcome. This was achieved in the process of counterfactual thinking.37 We, therefore, used feedback loop diagrams as an analytic strategy to synthesise material from the review of evidence to map out pathways of change in community-integrated care initiatives and to identify generative mechanisms.17 Using causal loop diagrams helped us to identify and represent the relevant constructs (structures, contexts, mechanisms and outcomes) and to illustrate the links between these constructs to highlight the micro theories that make up the theoretical model.36

To streamline our identified theories, we followed Layder’s conceptualisation: self—consumer, situated face to face—clinician-consumer, and intermediate level of social and service organisation,38 which aligns with the microlevel (clinical), mesolevel (service delivery) and macrolevel (system) of a health system. For each of these levels, we have provided thematic constructs for each of the elements in our heuristic tool, with table 1 illustrating the different elements of the Structure-Context-Mechanism-Outcome heuristic framework. In addition to the illustrative tables, we constructed causality models using the corresponding elements identified in table 1. Figures 6–8 illustrate the programme theories elicited at three levels.

Table 1.

Thematic representation of the realist constructs

| Structure | Context | Mechanism | countervailing and/or control mechanisms | Outcome |

| Systems level | ||||

| National and regional policies promoting integrated care initiatives |

|

|

|

|

| Prevalent integrated health concerns |

|

|

|

|

| Historical Silos |

|

|

|

|

| Provider level | ||||

| State of formalisation of integrated care |

|

|

|

|

| Goals of the involved agencies |

|

|

|

|

| Level and complexity of clients’ vulnerabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Existing leadership structures |

|

|

|

|

| Collaborative design of the integrated care initiatives |

|

|

|

|

| Consumer level | ||||

| Shared decision-making |

|

|

|

|

| Responsiveness to users' needs |

|

|

|

|

| Accompaniment and client autonomy |

|

|

|

|

| Co-location of services Programme flexibility |

|

|

|

|

| A platform for Information sharing |

|

|

|

|

The mechanisms at each level are related to the actors operating at that level. For instance, the systems level included stakeholders such as managers, heads of departments and other high-level stakeholders. The organisational level stakeholders includes programme implementers and health and social care providers. Consumer-level mechanisms relate to service users and their social networks.

Figure 6.

Systems-level SCMO configurational theory. The mechanisms at this level are related to the actors operating at the systems level such as managers, heads of departments and other high-level stakeholders. SCMO, structure–context–mechanism–outcome.

Figure 7.

Provider level SCMO configurational theory. Organisational level relates to programme implementers and health and social care providers. SCMO, structure–context–mechanism–outcome.

Figure 8.

User-level programme theory. Consumer-level mechanisms relate to service users and their social networks. C, context; M, mechanism; O, outcome; S, structure.

Step 5: disseminate, implement and evaluate

The output of this critical realist synthesis has practical applications in community-based integrated care programmes research, design, interventions and other health promotion efforts. For evaluation, stakeholders—persons involved with or affected by a course of action—consultations should be carried out in relation to specific integrated initiatives the form of discussions and realist interviews to refine the programme theories in a contextually meaningful way.

Patient and public involvement

It was not appropriate to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Discussion

In this critical realist review, we sought to unearth, based on the published literature, the critical generative mechanism and social structures required to explain how and why community-integrated care initiatives are designed, implemented and adopted by the targeted populations. To streamline our identified theories, we followed Layder’s conceptualisation: consumer level provider level, and systems or service level of social and health service organisation.38

At the systems level, three bundles of mechanisms were identified as critical to the consideration and design of community-based integrated health initiatives, namely, (1) commitment and motivation, (2) willingness to address integrated health concerns and (3) shared vision and goals. Frieden39 identified political commitment as one of the six critical elements necessary for effective public health programme design and implementation. He argued that effectively engaged political commitment leads to the provision of resources and support needed to design, coordinate, implement and sustain public health interventions, including policy change where needed.39 Lezine and Reed40 also identified political will as being essential for securing the resources for policy change. The critical role of shared vision and goals as core features for primary care transformation, which includes the design of relevant healthcare interventions was also discussed by Tamblyn et al.41 In combination, our study suggests that these three bundles of mechanisms are triggered under various contexts in the existence of structures such as national and regional policies promoting integrated care initiatives, the prevalence of integrated health concerns and historical service delivery silos to inform the development of integrated care initiatives.

At the provider level, five bundles of mechanisms critical to the successful implementation of integrated care initiatives were abstracted, namely, (1) shared vision and buy-in, (2) shared learning and empowerment, (3) perceived usefulness, (4) trust and perceived support, and (5) perceived role recognition and appreciation. Buy-in is considered to be a personal and professional commitment to actively engage in a process, task or initiative.42 Buy-in does not occur until the individual’s goals and core beliefs align with those of the organisation hence its association with shared vision.42 Shared vision and buy-in across organisations and professions are therefore critical to innovation and change including the implementation of integrated care initiatives.43 Empowerment relates to a process in which an individual understands their role, are given the knowledge and skills to perform a task and encourages their participation in an activity. Its connection to knowledge acquisition justifies its association with shared learning in our analysis. Generally, ideals of empowerment are used to draw attention to the capacities and abilities of individuals to promote power and participation.44 Regarding perceived usefulness, according to Gajanayake et al,45 healthcare professionals’ perception of the usefulness and their attitudes towards an intervention has significant effects on the overall acceptance of that intervention by users. Healthcare providers perceived support has been associated with increased participation in healthcare intervention delivery.46 The extant literature on organisational psychology suggests that employee engagement, in general, is related to the perceived social support offered by their organisation.47 Perceived support enhances trust—reliance on a trustee with confidence—which is also important in the functioning of the health system and delivery of health and social care services.48 An employee’s satisfaction with their job affects their quality of work and productivity. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology,49 when employees are appreciated, feel needed and nurtured, they become motivated to do more. The mechanisms discussed herein are underpinned within the structures of (1) state of formalisation of integrated care, (2) goals of the involved agencies, (3) level and complexity of clients’ vulnerabilities, (4) existing leadership structures and (5) collaborative design of the integrated care initiatives.

At the user level, five bundles of mechanisms were unearthed: (1) user motivation, (2) perceived interpersonal trust, (3) user-empowerment, (4) perceived accessibility to required services and (5) self-efficacy and self-determination. Motivation is central to the adoption of any healthcare delivery interventions. Regarding the uptake of integrated service initiatives, both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations have roles to play. While intrinsic motivation is based on the physiological needs of the patient primarily, extrinsic motivation is more service delivery related. Motivation has been identified as being a key mechanism for patient engagement in care especially long-term engagement.50 Perceived trust from the point of view of the patient is the cornerstone for the uptake of health and social care services. According to Rowe and Calnan,51 the need for interpersonal trust relates to the vulnerability associated with illness, information asymmetries, and the uncertainty and element of risk regarding the competence and intentions of the service provider. Having positive expectations regarding the competence of the service provider and that they will work in the best interests of patients51 is, therefore, a key mechanism driving the uptake of integrated care initiatives. Patient empowerment—a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health—is effective and beneficial to populations with complex medical and social needs.52 Individuals who have difficulty gaining access to healthcare may delay seeking such services. According to Shavers et al,53 an individual’s perception of healthcare access is likely to influence their uptake of healthcare services when the need arises. Two key determinants of behaviour are self-efficacy and self-determination. Individuals who have higher self-determined motivation to engage with integrated healthcare services are more likely to develop health self-efficacy.

In addition to identifying the generative mechanism and relevant structures central to determining how and why community-integrated care initiatives are designed, implemented and used, we also captured relevant social and health systems contexts that trigger such generative mechanisms. The consideration of context-embedded evidence includes understanding the history and precedence of the observation—basically what has happened in the past in the context, plays a part in explaining how things came to be so and not otherwise. Therefore, to improve the explanatory power and consequently, the adaptability of evidence informing the implementation of a community-integrated care initiative, the evidence should be linked to the programmatic/organisational and historical contexts.

The implementation of an integrated care approach involves all the settings where the targeted population dwell and function (communities), but also requires a concerted action among microlevel (clinical), mesolevel (service delivery) and macrolevel (system).54 The community is, therefore, of relevance as it represents where the actors reside and function. To this end, we used integrated-community health systems and patient-centred lenses to delineate our study boundaries and capture the complexity of how and why community-integrated care initiatives are designed, implemented and used. Although we formulated three programme theories relating to outcomes of design, implementation and uptake, these programme theories are intricately connected. What happens at one level, the programme design, for example, affects what happens at the other levels. For example, poor implementation outcomes of the community integrated care initiative at the provider level will affect the uptake or adoption of the intervention at the user level. This approach aligns with the complexity science approach, a theoretical approach to understanding interconnections among agents and how they give rise to emergent-level, dynamic-level, and systems-level behaviours.55

Limitations

All but one of the studies from which the evidence was obtained came from high income countries with most of the studies conducted in Australia and the USA. Therefore, critical context element and relevant mechanisms that are unique to middle-income and low-income countries might have not been captured.

Conclusion

Outcome-based and process evaluation exercises have demonstrated that community integrated care initiatives integrating healthcare and social services improve the uptake of healthcare services and the health outcomes of the targeted populations. This critical realist review unearthed the generative mechanisms, relevant structures and influential contextual elements critical to the successful design, implementation and uptake of these initiatives. In our three programme theories, we systematically captured through retroductive thinking, explanatory models to provide feedback to intervention developers and implementation-relevant information to the practice communities.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: The project was conceived by FCM and JGE. FCM designed, conducted and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DDS provided methodological guidance and contributed to writing these sections. HL, GU and JGE revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published.

Funding: This study will be funded in part by Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW Australia (Award No. 162 N/A), and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Grant (Award No. 163 APP1198477) Centre of Research Excellence for Integrated Health and Social Care (Award No. N/A).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Formal ethics review is not required for the review itself, as it constitutes secondary research with the element of peer feedback from relevant researchers.

References

- 1.Eastwood J, Miller R. Integrating Health- and Social Care Systems. In: Amelung VSV, Suter E, Goodwin N, et al., eds. Handbook integrated care. Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2021: 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications--a discussion paper. Int J Integr Care 2002;2:e12. 10.5334/ijic.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin N. Understanding integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:6. 10.5334/ijic.2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plochg T, Klazinga NS. Community-Based integrated care: myth or must? Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:91–101. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.intqhc.a002606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q 1999;77:77–110. 10.1111/1468-0009.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, et al. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:350. 10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eastwood JG, De Souza DE, Shaw M, et al. Designing initiatives for vulnerable families: from theory to design in Sydney, Australia. Int J Integr Care 2019;19:9. 10.5334/ijic.3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dnestrean T. Assessing community needs in rural Moldova – an integrated medico-social service approach. Int J Integr Care 2021;21:11. 10.5334/ijic.ICIC20444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiam Y, Allaire J-F, Morin P, et al. A conceptual framework for integrated community care. Int J Integr Care 2021;21:5. 10.5334/ijic.5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billings J, de Bruin SR, Baan C, et al. Advancing integrated care evaluation in shifting contexts: blending implementation research with case study design in project sustain. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:971. 10.1186/s12913-020-05775-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crocker H, Kelly L, Harlock J, et al. Measuring the benefits of the integration of health and social care: qualitative interviews with professional stakeholders and patient representatives. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:515. 10.1186/s12913-020-05374-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smeets RGM, Hertroijs DFL, Mukumbang FC, et al. First things first: eliciting the initial program theory for a realist evaluation of the TARGET integrated care program. The Milbank Quarterly 2021;99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smithson R, Wicker C. Understanding complex interventions: evaluating the impact of integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2021;20:1. 10.5334/ijic.s4001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eastwood JG, Souza DED, Mukumbang FC, Amelung VSV, Suter E, Goodwin N, et al., eds. Handbook integrated care. Springer, 2021: 629–56Design and Evaluation for Integrated Care Initiatives. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagosh J. Retroductive theorizing in Pawson and Tilley’s applied scientific realism. J Crit Realism 2020;19:121–30. 10.1080/14767430.2020.1723301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10 Suppl 1:21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinds K, Dickson K. Realist synthesis: a critique and an alternative. J Crit Realism 2021;20:1–17. 10.1080/14767430.2020.1860425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagosh J. Realist synthesis for public health: building an Ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:361–72. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science. Madison Avenue, New York: Routledge, 2008: 310 p. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE Publications, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayer A. Realism and social science. London: Sage Publications, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Souza DE. Elaborating the Context-Mechanism-Outcome configuration (CMOc) in realist evaluation: a critical realist perspective. Evaluation 2013;19:141–54. 10.1177/1356389013485194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenhalgh J, Manzano A. Understanding ‘context’ in realist evaluation and synthesis. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2021;41:1–13. 10.1080/13645579.2021.1918484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:33. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11:21. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaffmann Zambruni J, Rasanathan K, Hipgrave D, et al. Community health systems: allowing community health workers to emerge from the shadows. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e866–7. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30268-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukumbang FC, van Wyk B. Leveraging the Photovoice methodology for critical realist theorizing. Int J Qual Methods 2020;19:160940692095898. 10.1177/1609406920958981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klingberg S, Adhikari B, Draper CE, et al. Engaging communities in non-communicable disease research and interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a realist review protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11:e050632. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danermark B, Ekström M, Karlsson JC. Explaining Society: critical realism in the social sciences. 2 edn. Routledge, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tennant E, Miller E, Costantino K, et al. A critical realist evaluation of an integrated care project for vulnerable families in Sydney, Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:995. 10.1186/s12913-020-05818-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Booth A, Briscoe S, Wright JM. The "realist search": A systematic scoping review of current practice and reporting. Res Synth Methods 2020;11:14–35. 10.1002/jrsm.1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter R, Gorely T, Beattie M, et al. Realist review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2022;15:242–65. 10.1080/1750984X.2021.1969674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilmore B, McAuliffe E, Power J, et al. Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: toward more transparent methodological approaches. Int J Qual Methods 2019;18:160940691985975. 10.1177/1609406919859754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiltshire G, Ronkainen N. A realist approach to thematic analysis: making sense of qualitative data through experiential, inferential and dispositional themes. Journal of Critical Realism 2021;20:159–80. 10.1080/14767430.2021.1894909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukumbang FC. Retroductive theorizing: a contribution of critical realism to mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res 2021;15:155868982110498. 10.1177/15586898211049847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukumbang FC, Kabongo EM, Eastwood JG. Examining the application of Retroductive theorizing in Realist-Informed studies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2021;20:160940692110535. 10.1177/16094069211053516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukumbang FC, Marchal B, Van Belle S, et al. Using the realist interview approach to maintain theoretical awareness in realist studies. Qualitative Research 2020;20:485–515. 10.1177/1468794119881985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Layder D. New strategies in social research: an introduction and guide. Wiley, 1993: 232 p. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health 2014;104:17–22. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lezine DA, Reed GA. Political will: a bridge between public health knowledge and action. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2010–3. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamblyn R, Meyers D, Kratzmann M, et al. Shared vision for primary care delivery and research in Canada and the United States: highlights from the Cross-border symposium. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:930–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.French-Bravo M, Crow G. Shared governance: the role of Buy-in in bringing about change. Online J Issues Nurs 2015;20:388–408. 10.3912/OJIN.Vol20No02PPT02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussain S, Dornhorst A. Integrated care: the clinicians' view. Future Hosp J 2015;2:83–5. 10.7861/futurehosp.2-2-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halvorsen K, Dihle A, Hansen C, et al. Empowerment in healthcare: a thematic synthesis and critical discussion of concept analyses of empowerment. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:1263–71. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gajanayake R, Sahama T, Iannella R. The role of perceived usefulness and attitude on electronic health record acceptance. International Journal of E-Health and Medical Communications 2014;5:108–19. 10.4018/ijehmc.2014100107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitz KM, Terhorst L, Smith CN, et al. Healthcare providers' perceived support from their organization is associated with lower burnout and anxiety amid the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2021;16:e0259858. 10.1371/journal.pone.0259858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahman A, Björk P, Ravald A. Exploring the effects of service provider’s organizational support and empowerment on employee engagement and well-being. Cogent Business & Management 2020;7:1767329. 10.1080/23311975.2020.1767329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezumah N, Manzano A, Ezenwaka U, et al. Role of trust in sustaining provision and uptake of maternal and child healthcare: evidence from a national programme in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 2022;293:114644. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oncology ASoC . Staff recognition and appreciation. J Oncol Pract 2007;3:100–1. 10.1200/JOP.0725501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukumbang FC, Van Belle S, Marchal B, et al. Exploring 'generative mechanisms' of the antiretroviral adherence club intervention using the realist approach: a scoping review of research-based antiretroviral treatment adherence theories. BMC Public Health 2017;17:385. 10.1186/s12889-017-4322-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rowe R, Calnan M. Trust relations in health care--the new agenda. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:4–6. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakefield D, Bayly J, Selman LE, et al. Patient empowerment, what does it mean for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: a systematic review using critical interpretive synthesis. Palliat Med 2018;32:1288–304. 10.1177/0269216318783919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shavers VL, Shankar S, Alberg AJ. Perceived access to health care and its influence on the prevalence of behavioral risks among urban African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc 2002;94:952–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cesari M, Sumi Y, Han ZA, et al. Implementing care for healthy ageing. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e007778. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, et al. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med 2018;16:63. 10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.