Abstract

Over the past few decades, advances in the pharmacologic, catheter-based, and surgical reperfusion have improved outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarctions (AMI). However, patients with large infarcts or those who do not receive timely revascularization remain at risk for mechanical complications of AMI. The most commonly encountered mechanical complications are acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to papillary muscle rupture, ventricular septal defect (VSD), pseudoaneurysm, and free wall rupture; each complication is associated with a significant risk of morbidity, mortality, and hospital resource utilization. The care for patients with mechanical complications is complex and requires a multidisciplinary collaboration for prompt recognition, diagnosis, hemodynamic stabilization, and decision support to assist patients and families in the selection of definitive therapies or palliation. However, because of the relatively small number of high-quality studies that exist to guide clinical practice, there is significant variability in care which mainly depends on local expertise and available resources.

In this American Heart Association Scientific Statement, we: (1) define the epidemiology of mechanical complications of AMI; (2) propose contemporary best medical, interventional, and surgical management practice considerations; (3) consider best practices in clinical decisions and supportive care, and (4) outline specific research gaps for future investigation to improve overall cardiovascular care and post-discharge outcomes for this high acuity and complex patient population.

Keywords: Myocardial Infarction, Mechanical Complications, Outcomes, Cardiac Intensive Care Unit, Older Adults, Aging

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the American Heart Association (AHA) estimates that the overall prevalence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is 3%1, but advances in primary prevention resulted in significant decline in age- and sex- adjusted incidence of AMI over the past decades.2 Despite such improvements, large infarcts, late hospital presentation, and a lack of tissue-level reperfusion due to no reflow or poor coronary flow after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remain risk factors for mechanical complications, hemodynamic instability, and pump failure.3

While the incidence of mechanical complications remains low, the associated mortality rate is high, especially among older patients.4 Further, surgical and percutaneous therapeutic options are frequently complex and require the expertise of a multidisciplinary team of cardiac intensivists, non-invasive cardiologists, heart failure/transplant specialists, interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, palliative care specialists, nursing, and allied healthcare professionals. The high-acuity and time sensitive presentation of these complications highlight the need for timely recognition and prompt initiation of therapy to mitigate prolonged states of cardiogenic shock and potential death. In addition, differentiation between mechanical complications of AMI from non-cardiac causes of shock or other causes of pump failure requires integration of non-invasive imaging and/or invasive hemodynamic assessments. High quality evidence to guide management of mechanical complications of AMI is sparse and international clinical practice guidelines for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) lack comprehensive discussion on therapeutics and multidisciplinary management related to mechanical complications.5, 6 Hence, inter-institutional management may vary depending on local expertise and available resources.

In this AHA statement, we aimed to: (1) define the epidemiology of mechanical complications of AMI; (2) propose contemporary best medical, interventional, and surgical management practice considerations; (3) consider best practices in clinical decision and supportive care, and (4) outline specific research gaps for future investigation to improve the overall cardiovascular care and post-discharge outcomes in this high acuity and complex patient population.

RISK FACTORS FOR MECHANICAL COMPLICATIONS

Over the past 30 years, improvements in timely reperfusion within regionalized systems of care together with advancement in optimal medical therapies have contributed to reduced mortality of AMI.3, 7 However, these improvements are challenged by aging of the United States population and the higher burden of comorbidities that have been identified as risk factors for post-AMI mechanical complications.4, 8 Although there has been a temporal decline in the proportion of patients presenting with STEMI, contemporary patients with mechanical complications tend to be older, female, have a history of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and are often presenting with their first AMI.7, 9, 10 Furthermore, differences in the socioeconomic factors can play a significant role in influencing health outcomes after AMI.11 For example, prior research has reported that Medicare beneficiaries with the highest income category presented to the hospital earlier, were more likely to be treated by a specialized staff in the cardiac catheterization facilities, and received higher rates of guideline directed medical therapy, as compared to beneficiaries with lower socioeconomic class.11 Despite improvements in revascularization strategies and processes of care for STEMI, the incidence of mechanical complications has remained relatively unchanged over time. This can be explained, in part, by the growing prevalence of recognized cardiovascular risk factors and the aging of the U.S. population.10, 12, 13

THE HISTORY OF REPERFUSION STRATEGIES AND THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MECHANICAL COMPLICATIONS

The introduction of fibrinolytic therapy marked the beginning of an era of reperfusion therapies for treating STEMI, resulting in a 40% reduction in overall mortality.14 Beginning in the early 1990s, and continuing over the next decade, numerous studies supported a strategy of primary PCI, which was shown to be a safer and a more effective therapy to restore myocardial blood flow, resulting in a further reduction in short- and long-term mortality.15, 16 With the adoption of primary PCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy, the focus was now placed on improving systems of care to maximize the proportion of patients receiving PCI and emphasize timely percutaneous revascularization.17 Studies have demonstrated that when emergency medical services and hospital systems work together using coordinated protocols of care, mortality is further reduced for STEMI and cardiogenic shock.18, 19

Over the past two decades, the systematic adoption of early percutaneous revascularization for patient with AMI have a favorable impact on the global incidence of mechanical complications of AMI. The most notable minor reduction was observed during the era of primary PCI when the focus was placed on systems of care for STEMI (Figure 1).8, 13, 20, 21 Despite these improvements, studies reporting on outcomes among those with mechanical complications have shown conflicting results.8, 10, 12, 20, 21 Some studies have shown improved outcomes, but the majority reported that the case fatality rates for mechanical complications have remained flat despite an increase in the use of mechanical circulatory support devices, the use of percutaneous therapies for managing some complications of shock, and improvements in surgical techniques and outcomes over time.8, 10, 13 In contemporary studies, close to ¾ of these patients presented with cardiogenic shock and the majority required vasopressors, balloon pump, or percutaneous left ventricular support device.22 Diminished cardiac output secondary to cardiogenic shock leads to systemic hypoperfusion and maladaptive cycles of ischemia, inflammation, vasoconstriction, and volume overload culminating in multi-system failure and death.23 Recent evidence from clinical trials have suggested that there is no mortality difference between primary PCI and fibrinolysis combined with adjunctive medical therapy.24 While it is difficult to ascertain one causal mechanism to explain the stable incidence rate overtime despite the improvement in the management of AMI, possible explanations include (1) The rapid aging of the U.S. population, which increases the cohort at risk for mechanical complications; (2) Improvements in cardiac imaging and diagnostic ability to detect mechanical complications; (3) Growth of specialized cardiac centers with multidisciplinary care and advanced hemodynamic support systems to accept and triage these patients.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the incidence and mortality rates of mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction during different reperfusion strategies. STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

ACUTE MITRAL REGURGITATION SECONDARY TO PAPILLARY MUSCLE RUPTURE

The incidence of acute severe mitral regurgitation (MR) from papillary muscle rupture (PMR), like other mechanical complications of AMI, has declined in the reperfusion era (range: 0.05 to 0.26%)9, 25, but the reported hospital mortality remains high between 10 and 40%.9, 25, 26 The mitral valve is supported by two papillary muscles, the antero-lateral which has a dual arterial blood supply from the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the diagonal or marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery and the posteromedial papillary muscle which has a single blood supply from the circumflex coronary artery or the right coronary artery, depending on dominance. Thus, anterolateral PMR is extremely uncommon and posteromedial PMR typically occurs in association with inferior or lateral STEMIs. PMR may be complete or partial, which may influence the severity of the clinical symptoms.

Risk factors for PMR include older age, female gender, a history of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a delayed presentation with a first AMI.7, 9, 10, 27 PMR commonly occurs within days of AMI, and roughly half of patients present with pulmonary edema that may quickly progress to cardiogenic shock (Table 1).12 A murmur may be absent due to rapid equalization of left atrial and left ventricular pressures. The modern CICU has adopted the use of bedside echocardiography or point-of-care ultrasound for the management of acute cardiovascular illness, which can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of acute MR secondary to PMR; though it should be recognized that transthoracic echocardiography study can be non-diagnostic in cases of partial PMR and transesophageal echocardiography has a high diagnostic sensitivity. Left ventricular ejection fraction is often normal or low-normal, and coronary angiography will most often demonstrate single or 2-vessel CAD, with total occlusion of the infarct-related artery.8

Table 1.

Summary of major mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction.

| Complication | Presentation | Diagnosis | Management | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papillary muscle rupture and acute mitral regurgitation | 3–5 days post transmural infarct (inferior or lateral). Acute pulmonary edema and/or shock. | Echo shows severe and often eccentric jet of MR and mobile mass in LV sometimes prolapsing into LA | Surgical replacement (or repair in select cases) -(preferably emergency operation within 24 hours) | 10–40% |

| Ventricular septal defect | Commonly 3–5 days post transmural infarct. Symptoms range from isolated murmur to circulatory collapse | Echo shows left-to-right shunt across septum. Mixed venous O2 saturations> right atrial, i.e. step-up in O2 saturation | Initial afterload reduction with IABP or LV assist device. Urgent surgical or percutaneous repair, timing depends on cardiogenic shock and end-organ function | 30–40% |

| Rupture of the ventricular free wall | Commonly 3–5 days post transmural infarct. Tamponade and shock | Echo shows tamponade, and may visualize flow across defect in free wall | Immediate surgical repair unless prohibitive surgical risk | >50% |

| Pseudoaneurysm | Weeks to years after infarct. May be asymptomatic or present with chronic heart failure | CT scan or echo shows large aneurysm cavity with flow from LV across small neck | Urgent surgical or percutaneous repair, depending on symptoms | <10% |

Abbreviations: IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; LV: Left ventricle; LA: Left atrium; MR: Mitral regurgitation; CT: Computerized tomography.

Percutaneous repair needs discussion by the multidisciplinary heart team because only few cases are reported in the literature.

Initial medical care and resuscitation efforts in the CICU may include the need for vasoactive drugs and respiratory support with invasive mechanical ventilation.28 The use of positive pressure ventilation can improve gas exchange and cardiovascular hemodynamics by reducing LV preload and afterload, mitral regurgitation, and augment cardiac output.29 In hemodynamically stable patients, intravenous nitroglycerin or nitroprusside can be administered in the critical care environment to reduce left ventricular afterload. According to an American Heart Association Scientific Statement on contemporary management of cardiogenic shock secondary to severe mitral regurgitation28, norepinephrine or dopamine are good initial vasoactive agent that can be used for hemodynamic support, but after the hemodynamic stabilization is achieved, the addition of an inotropic agent is suggested for patients with pump failure.28 However, it should be noted that the use of vasopressors and inotropic support for mechanical complications of AMI has not been tested in clinical trials. In cases with advanced forms of cardiogenic shock, multiple organ failure, or other contraindications to surgery, a “Heart Team” discussion may lead to medical optimization in CICU and temporary mechanical support. Large v-waves from placement of the pulmonary catheter in a wedge position should be delineated from the pulmonary arterial waveform. While it is a rare complication of Swan-Ganz catheter, unrecognized prolonged balloon inflation in the wedge position can lead to catheter-associated pulmonary infarct. Patients who do not initially present with cardiogenic shock commonly experience rapid hemodynamic deterioration. The proportion of patients who suffered acute mitral regurgitation due to papillary muscle rupture and required mechanical circulatory support prior to mitral valve surgery was in excess of 70%.25 In the APEX-AMI trial, patients who underwent surgical repair had a markedly improved survival rate at 90 days, as compared to those who were treated medically (Surgical Treatment: 69% vs. Medical Treatment: 33%). While the IABP-Shock II Trial did not show mortality benefit from use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in patients with AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock30, the study excluded patients with mechanical complications and IABP placement is still recommended by guidelines as a bridge to therapy because of its presumed ability to reduce afterload in patients with severe MR due to PMR. The use of IABP provides approximately 0.5 L/min of cardiac output for mechanical circulatory support by using balloon counter-pulsation.23 This mechanism increases the aortic pressure during diastole while decreasing the mean arterial pressure during ejection, which in turn reduces the impedance (i.e., afterload) for the ejected blood from the left ventricle during systole and at the same time increases coronary blood flow during diastole.23 The reduction in the afterload during severe mitral regurgitation due to papillary muscle rupture decreases the regurgitant volume and regurgitant fraction, which may ultimately increase cardiac index.28 The experience with mechanical circulatory support, including percutaneous ventricular assist devices and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) for stabilization in PMR is limited to small case series, but can be considered as a bridge to decision or definitive surgical or percutaneous therapies.31

Cardiac Surgery

Acute papillary muscle rupture is a surgical emergency requiring immediate evaluation by a surgical team. Respiratory failure as a sequalae of mechanical complications should trigger prompt surgical and/or shock team evaluation. The emergent use of temporary mechanical circulatory support preoperatively may help attenuate the incidence of pre-operative or post-anesthetic induction hemodynamic and/or respiratory deterioration. Mitral valve replacement is generally utilized because the operation is predictable, and its durability is established. Patients included in surgical series of PMR treatment are highly selected and their outcomes cannot be generalized to all-comers given many patients with PMR are not considered for mitral valve surgery. For example, in the SHOCK trial registry, only 38% of patients with AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock from acute severe MR were offered mitral valve surgery.32 A recent analysis of AMI admissions from the National Inpatient Sample found that only 58% of patients with PMR underwent mitral valve surgery.25 Factors that may influence this decision include advanced age, comorbidities, and inability to stabilize the patient while awaiting for surgery.

Controversy exists on the optimal surgical approach to management of severe MR secondary to PMR.33 Chordal-sparing mitral valve replacement is generally utilized because the operation is predictable, and its durability is established. When compared to bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement, the use of a mechanical valve may improve long term symptom free survival particularly in younger patients.34, 35 Small series have reported repair techniques, typically for patients with partial PMR and less preoperative hemodynamic derangement with operative mortality approaching 20%.36, 37 The choice of bioprosthetic valve versus mechanical valve is also guided by the need for mechanical circulatory support or advanced heart failure therapies wherein the risk of mechanical valve thrombosis with LVAD and ECMO may be much higher.

Concomitant coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) should be considered in patients with PMR and obstructive coronary disease. However, the surgeon must weigh the risks of prolonging the operation versus the benefit of revascularization with CABG. Some surgical series have reported improved outcomes with concomitant CABG.38 In a large series from Society of Thoracic Surgery Database, similar operative mortality was observed in patients who received mitral valve surgery with concomitant CABG versus those who received valve surgery alone (20.1% versus 19.8%, p =0.91). It should be noted that many patients may have multivessel coronary disease which will require surgical revascularization. In addition, high quality studies are lacking, but if severe multivessel disease is not treated at the time of mitral valve replacement, weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass may be less feasible. Low cardiac output syndrome as well as need for postoperative VA-ECMO predict mortality after surgery for PMR.

Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Mitral Valve Repair for Patients who are not Surgical Candidates

While surgical treatment remains the standard for severe MR secondary to PMR, surgical risk may be prohibitive in select patients.26 In chronic MR, percutaneous edge-to-edge mitral valve repair with MitraClip has become the standard of care for patients with prohibitive surgical risk.39 There are currently case reports of using MitraClip to treat severe MR secondary to PMR, but care should be taken when interpreting results from these reports because of publication bias with selective reporting of successful procedures.26 In select patients with PMR complicated by cardiogenic shock and pump failure with prohibitively high surgical risk, percutaneous mitral valve edge-to-edge repair may be a therapeutic option. However, we advocate for multidisciplinary team-based discussions, which incorporate the patient/family preferences for care, to determine the optimal surgical or percutaneous approach to definitive therapy. Other than transcatheter edge to edge repair, other therapeutic options in patients with contraindication to surgical mitral valve intervention include medical management in a bridge to candidacy for mitral valve replacement and temporary mechanical support as a bridge to long term ventricular assist device or heart transplantation.

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

Emergency mitral valve replacement is the treatment of choice, but repair, typically for patients with partial PMR and stable hemodynamics, can be considered by surgeons with technical expertise in MV repair.

Medical management as bridge to more advanced therapy can be considered in patients with severe MR secondary to PMR and complicated by cardiogenic shock.

The choice of bioprosthetic versus mechanical mitral valve replacement should be patient-centered and the decision should incorporate factors including age and need for prolonged anticoagulation therapy.

In select patients with prohibitive surgical risk, transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair can be considered as part of a “Heart Team” approach to management.

Concomitant CABG can be performed to achieve optimal revascularization with similar operative mortality to mitral valve surgery alone.

Patient preferences and values are an important consideration in any high morbidity/mortality treatment choices.

While mitral valve surgery is the standard of care, in patients with contraindications to surgery, medical management as a bridge to candidacy for MVR, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair, and temporary mechanical support as a bridge to long term ventricular assist device or heart transplantation can be considered.

VENTRICULAR SEPTAL DEFECT

In contemporary cardiovascular practice, the incidence of VSD after AMI is approximately 0.3%.40, 41 Risk factors include older age, female sex, and delayed reperfusion.7, 9, 10, 27 Typically occurring three to five days post-infarction, presentations range from an incidental murmur to circulatory collapse (Figure 2). Symptoms may include dyspnea and orthopnea, and clinical examination often reveals hypotension, cool peripheries and oliguria due to low cardiac output, and a new pansystolic murmur, commonly at the lower left sternal edge, with signs of pulmonary venous congestion. A 12-lead electrocardiogram may identify ongoing ischemia, evolving myocardial infarction, q-wave in the affected territory (anterior or inferior), and/or associated ventricular arrythmias.

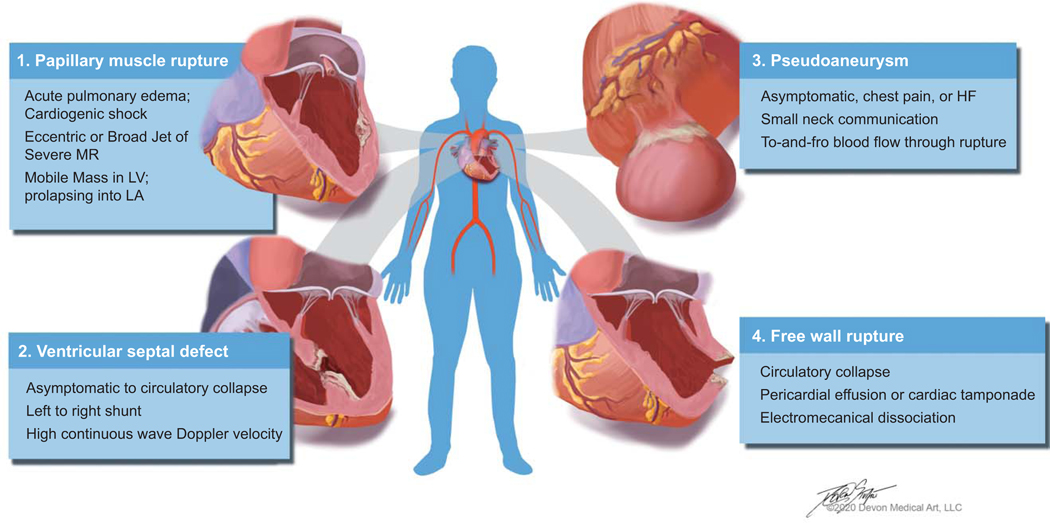

Figure 2.

Clinical characteristics of mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction.

Echocardiography is diagnostic for evaluating the size and location of a left-to-right shunt, biventricular function, and MR. Right heart catheterization shows a diagnostic “step-up” in oxygenation between the right atrium and pulmonary artery and elevated pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio (up to 8:1 depending on the defect size). Left heart catheterization often performed during the initial ischemic presentation guides concomitant revascularization and commonly shows a complete coronary obstruction without collateral circulation. Anterior and apical ischemic VSDs are caused by infarcts in the LAD territory, but posterior VSDs are due to inferior infarcts. Right ventricular infarction or ischemia with severe dysfunction is an important feature of VSDs caused by acute proximal right coronary occlusion. Posterior VSDs are often accompanied by MR commonly secondary to ischemic tethering (Figure 2). The location of VSD have been reported in one study and tend to occur more frequently in the anterior than inferior/lateral wall infarction (70% vs. 29%), but inferior infarcts are associated with “complex VSDs, those with multiple, irregular, and/or variable interventricular connections.41

Given the high mortality associated with uncorrected defects approaching 80% at 30 days, conservative medical therapy alone is limited to patients with hemodynamically insignificant defects, or those with prohibitive surgical risk.40, 42–44 Effective afterload reduction to decrease the left-to-right shunt is essential: intra-aortic balloon pumps with pharmacotherapy are used in over 80% of emergency and 65% of urgent repairs.5, 45 In the SHOCK trial registry, IABPs were utilized in up to 75% of post infarct VSDs. Within 30 minutes of initiation of IABP, the median systolic blood pressure was increased from 81 mmHg to 102 mmHg.46 When a patient presents with multi-organ failure, potential support with ECMO may be considered to allow for improvements in end-organ failure as a bridge to surgical candidacy. In patients without clinical symptoms or end-organ failure, a delayed treatment may allow for connective tissue or scar formation around the defect resulting a better anchor for suture material and a lower potential for patch dehiscence. Therefore, the patient with early shock and no evidence of multi-organ failure is potentially the best candidate for emergency surgery.47–49 Similar hemodynamic stability as a bridge to definitive therapy has been reported using ECMO50, Impella, and TandemHeart.51, 52 Patients severely compromised by multi-organ failure may benefit from biventricular mechanical support or ECMO with percutaneous or surgical left ventricular vents, allowing end-organ recovery before definitive surgery. The purpose of LV venting is to reduce LV afterload/preload, reduce the pulmonary shunt fraction, and thereby reduce pulmonary edema and improve gas exchange. The venting may be necessary to reduce acute lung injury and/or harlequin (North/South) syndrome. In addition, the LV vent may improve LV flow and the therapy minimizes the risk of LV or aortic thrombosis. However, venting strategies may also have potential drawbacks in patients with VSD including aspiration of deoxygenated blood from the right side to the left and embolization of necrotic LV debris with the use of Impella. In VSDs, the RV flow may minimize the risk of LV thrombosis and increase the risk of aortic thrombosis. Careful considerations of LV venting in patients with ECMO and in patients with post infarct VSD should be exercised. We suggest that a multi-disciplinary team carefully weigh the risk and benefits of LV venting in patients supported with ECMO.53, 54 Emergency surgery is indicated for patients with cardiogenic shock and/or pulmonary edema refractory to mechanical circulatory support. Lower mortality is reported when surgery is delayed for a week after diagnosis, although selection and survival bias may explain these reported outcomes.51 The rationale for delaying surgery in hemodynamically stable patients is to avoid bleeding from antiplatelet medication and allow improved patient selection for optimal outcomes.

Cardiac Surgery

During surgical repair of VSD, coronary bypasses are performed first, commonly with saphenous veins, to facilitate myocardial protection and minimize handling of the heart after VSD repair. Surgical techniques include primary repair (Dagett) or infarct exclusion (David) (Table 1; Figure 3). For anterior VSDs, the infarcted surface of the anterolateral left ventricle (LV) is incised parallel to the LAD. The septal defect is usually located immediately beneath the incision. A patch repair using pericardium or synthetic material is performed utilizing mattress sutures with the pledgets on the right ventricular side in non-infarcted myocardium, so the whole LV aspect of the septum is excluded from the mitral anulus to the anterolateral LV wall. It should be noted that the pressurized patch for VSD should be on the LV side with pledgets on the RV side. It is usually possible to close the left ventriculotomy primarily with mattress sutures buttressed with pericardium or felt, reinforced with continuous sutures and bioglue. True apical VSDs can be repaired and closed primarily by amputating the apex. Posterior VSDs are approached via a ventriculotomy in the infarcted posterior LV wall parallel to the posterior descending coronary artery, attaching a patch to the LV aspect of the non-infarcted septum with patch closure, primary closure or infarct exclusion depending on how much free ventricular wall is infarcted. Temporary left ventricular assist devices may be considered to decompress the LV reducing risk of left ventriculotomy rupture and supporting cardiac output post-operatively. Operative mortality following repair of a VSD remains at 40% and has not changed significantly in decades (Table 1).1,4 Among patients who underwent surgical repair of post-infarct VSD, preoperative prognostic factors associated with in-hospital mortality include poor ventricular function, deteriorating cardiovascular status, cardiogenic shock, inferior AMI, inotropic support and total occlusion of the infarct related artery.55 Factors that determine long-term survival include right ventricular dysfunction, residual LV function after surgical closure, and New York Heart Association functional class at the time of presentation.56

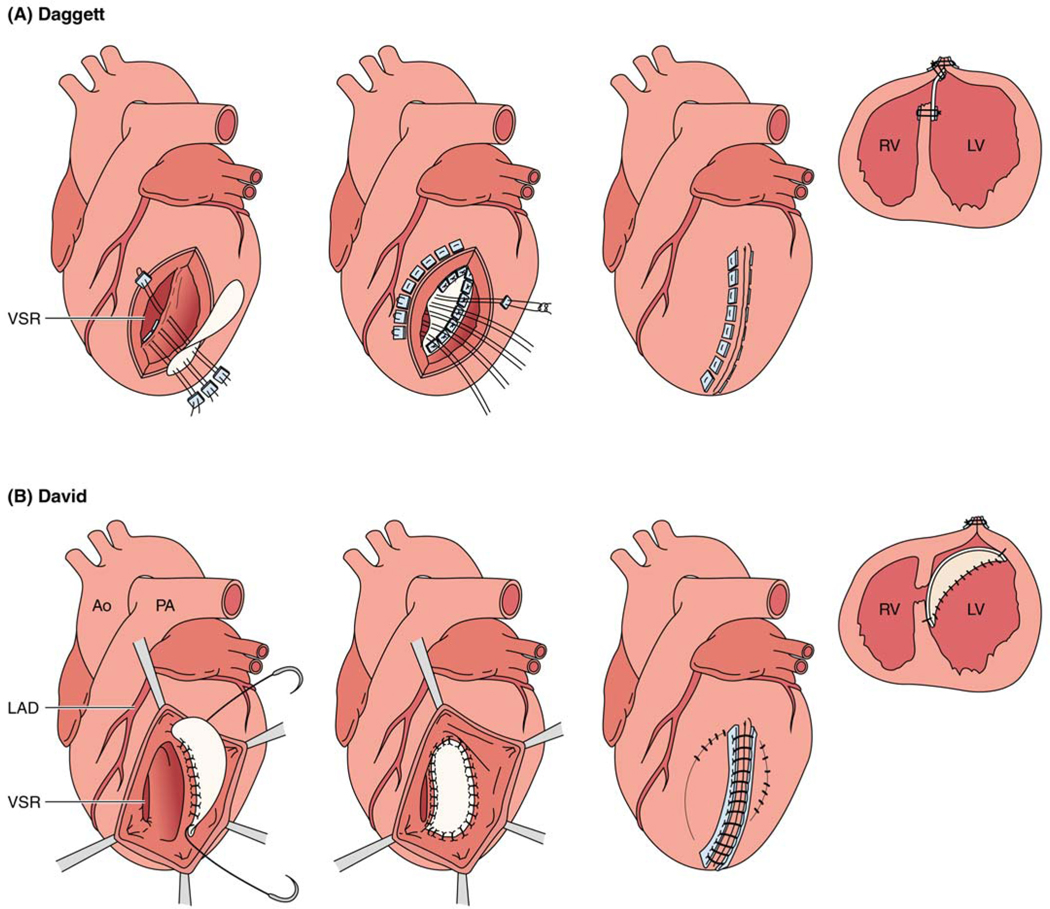

Figure 3.

Techniques for surgical repair of post infarct ventricular septal defect. A. Daggett and B. David repair. Note: for the Daggett repair and in the first two images of panel A, stitches are taken from the RV free wall, which is on the other side of the LAD (not as depicted).

Other modified surgical techniques to repair post-infarct VSD including the double-patch technique were previously described.57, 58 For an anterior-type VSD, a left ventriculotomy is performed approximately 2 cm away from the LAD and through the infarct zone.57 The first bovine pericardial patch is sutured to the healthy endocardium excluding the infarcted muscle from the ventricular cavity.57 A second small patch is utilized to close the perforated VSD directly with running sutures, which prevents the right to left shunt of blood until the bioglue or fibrin that is inserted in the cavity between the patches is stabilized.57, 58 Finally, the left ventriculotomy site is closed.57 This double patch repair can also be utilized for posterior VSDs.58

Transcatheter Repair of VSD

In patients who are not suitable for surgical treatment of VSD repair due to excessive risk, percutaneous closure can be considered. The procedure is usually performed under general anesthesia with transesophageal echocardiogram guidance for device sizing. Most commonly, the VSD is crossed using a hydrophilic wire from the left to the right ventricle into the pulmonary trunk. The wire is snared and exteriorized through the venous access (femoral or jugular). Over this arteriovenous rail, a shuttle sheath is advanced into the interventricular septum and an occluder is deployed. If difficulties crossing the VSD are encountered, right to left wiring and exteriorization can be performed. While procedural success approaches 89% (range: 80–100) in centers of excellence, hospital mortality remains excessively high and procedural complications are common.42–44, 59 These include device embolization, arrhythmia, hemolysis, and failure of complete occlusion of the VSD requiring surgical repair. Predictors of adverse outcomes include delayed diagnosis, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, increased pulmonary to systemic flow ratio at time of closure, and residual defect. In patients with severe refractory shock and biventricular failure prohibiting surgical or transcatheter repair, evaluation for durable mechanical circulatory support or heart transplantation or total artificial heart may be considered.60

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

Post-infarction VSD caused by rupture of infarcted myocardium typically occurs 3 to 5 days after a transmural AMI in <0.3% of patients in the contemporary era of routine primary revascularization.

Immediate afterload reduction is the mainstay of initial therapy; periprocedural temporary mechanical support is a useful adjunct to decompress the left ventricle and support cardiac output.

Optimal timing of surgical treatment should be discussed between a cardiac surgeon, cardiologist and cardiac intensivist and the severity of cardiogenic shock, organ failure and risk of coagulopathy due to antiplatelet medication should be factored in the decision making.

Urgent post-infarct VSD surgical repair in patients with cardiogenic shock and/or respiratory failure is associated with 40% mortality; percutaneous closure is an emerging treatment option for patients with prohibitive surgical risk.

We suggest delaying of surgery when feasible in hemodynamically stable patient without respiratory failure to allow better patient selection and for oral antiplatelet therapy to be less of a complicating factor during surgery.

Options in patients who are not candidates for VSD repair include percutaneous closure, mechanical support to heart transplant, and palliative medical therapy

FREE WALL RUPTURE

Although free wall rupture is the most commonly reported mechanical complication of AMI, its true incidence is unknown because it usually presents as out-of-hospital sudden cardiac death and there is lack of routine autopsy. While the overall incidence of rupture has decreased with prompt acute reperfusion therapy for STEMI, the initial trials of fibrinolysis vs placebo showed an early increased risk of free wall rupture after 24 hours with fibrinolytic therapy which supports a higher risk of rupture with delayed reperfusion therapy.5 This is attributed to intra-myocardial hemorrhage, myocardial dissection, and subsequent rupture.20

Free wall rupture should be suspected in any patient with hemodynamic instability or collapse following AMI, especially in the setting of delayed or ineffective reperfusion therapy. The clinical exam classically shows jugular venous distension, a pulsus-paradoxus or frank electromechanical disassociation, and/or muffled heart sounds in the setting of cardiovascular collapse. It is sometimes preceded by chest pain and nausea, and ECG may show new ST elevation as contact with blood irritates the pericardium. Free wall rupture is rapidly fatal, but occasionally a prompt bedside echocardiogram confirms the diagnosis and warrants emergent surgical correction. While surgery can be lifesaving, the hospital mortality for patients who underwent surgical repair is in excess of 35%.61, 62 A variant of frank rupture characterized by a friable infarct zone with an oozing bloody pericardial effusion should be recognized. In cases of circulatory collapse, immediate placement on ECMO support may provide an opportunity to stabilize the circulation and perform definitive repair with acceptable results, but poor venous return in cases with tamponade may limit ECMO blood flow.62

Cardiac Surgery

The initial surgical repair was performed by Fitzgibbons and involved an infarctectomy with defect closure on cardiopulmonary bypass.63 The goals of surgical intervention revolve around repairing the defect, treating tamponade, and leaving behind adequate healthy tissue that will minimize late complications.61 The preferred technique is guided by anatomy and presentation, and may rarely be limited to a linear closure, but often involves an infarctectomy when extensive necrosis is present with patch closure with materials like Dacron or pericardium. The ideal repair when anatomy allows is a primary patch repair that covers the defect. If depressurizing the LV either with cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegic arrest or LV vent, a sutureless repair utilizing a patch and glue or a collagen sponge patch can be a useful adjunct therapeutic approach. Mechanical circulatory support using ventricular assist devices may be considered to help wean patients from cardiopulmonary bypass after surgical closure of the LV free wall rupture and to provide left ventricular decompression.64 A percutaneous approach utilizing intrapericardial fibrin-glue injection has been described.61

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

Free wall rupture, a devastating complication of AMI with delayed or no reperfusion, usually results in sudden cardiac death.

High clinical suspicion, prompt diagnosis confirmed by echocardiography and immediate surgery are needed; ECMO may be needed for pre-operative stabilization.

While surgical technique for management of FWR continues to evolve, a primary patch repair that covers the defect, and when feasible a sutureless repair utilizing a patch and glue or a collagen sponge patch, can be used in a small subset of patients as an adjunct therapeutic option.

LEFT VENTRICULAR PSEUDOANEURYSM AND LV ANEURYSMS

Pseudoaneurysms of the LV develop when cardiac rupture is contained by pericardial adhesions.65–68 While they may occur after cardiovascular surgery, blunt or penetrating chest trauma, or as a result of infective endocarditis, pseudoaneurysms are most commonly associated with prior AMI.65–67 Compared to true aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms more often involve the inferior or lateral wall – perhaps the result of dependent pericardial adhesions developing in the recumbent, convalescing post-infarction patient.67 While acute anterior wall rupture is thought to result in massive hemopericardium, catastrophic tamponade, and immediate death, other pseudoaneurysms can remain undiagnosed for several months or longer.65–68

Patients with pseudoaneurysm may present with a myriad of signs or symptoms, none of which can be considered pathognomonic for the condition (Table 1). While previous case series have argued that nearly half of afflicted individuals will be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis66, more contemporary studies and systematic reviews instead note that the majority will be expected to present with congestive heart failure, chest pain, or shortness of breath.67, 68 Others may develop symptomatic arrhythmias, signs of systemic embolization, and even sudden cardiac death. Most patients are male, and will have both electrocardiographic (e.g. ST segment changes) and radiographic (e.g. “mass-like” protuberance on plain film or cardiomegaly) abnormalities at presentation.67 Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, and often necessitates the use of multiple complimentary imaging tools; among these include coronary angiography and ventriculography, two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography, and/or magnetic resonance imaging.65–68 Pseudoaneurysms usually have a narrow neck and lack the normal structural elements found in an intact cardiac wall (Figure 2).65–68

While commonly a delayed complication of AMI, left ventricular aneurysm is associated with an increased risk of angina pectoris in part secondary to an increased left ventricular end diastolic pressure, thrombus formation, worsening heart failure, and hemodynamically significant ventricular tachyarrhythmia.69 The aneurysm is made of a thin, scarred, or fibrotic myocardial wall and it most commonly involves the anterior or apical walls of the LV. The most common etiology is a total thrombotic occlusion of the left anterior descending artery, but involvement to the inferior or basal walls secondary to the occlusion of the right coronary artery can also be observed.69 For most cases, the management is conservative.69

Cardiac Surgery

Left ventricular pseudoaneurysms represent surgical emergencies due to their high risk for progressive rupture. However, little is known about the natural history of medically managed disease. In one small series from the Mayo Clinic, none of those treated medically succumbed to fatal hemorrhage: most died due to other complications, including recurrent ischemia or progressive heart failure.66 Contemporary literature is quite sparse, and likely undermined by selection and publication bias. While case reports of percutaneous repair exist70, most experts believe that immediate surgical management is prudent (Table 1). Surgeons should be prepared to quickly institute cardiopulmonary bypass at the time of operative intervention, as rupture and hemodynamic collapse can occur soon after pericardial manipulation.68 In pseudoaneurysms with small necks and heavily fibrotic edges, primary repair with pledgeted sutures buttressed by polytetrafluoroethylene felt can be performed.71 In patients with basal LV pseudoaneurysm, Gore-Tex patches can minimize traction of the edges of the defect.71 Autologous pericardial or Dacron double patches can also be used to repair pseudoaneurysms with good surgical outcomes.71 The use of Dacron, autologous or bovine pericardium as a surgical patch have all been used with good surgical outcomes. For patients with a remote myocardial infarction, the incidental discovery of LV pseudoaneurysm may be evaluated and planned for closure on an urgent rather than an emergent basis.

For left ventricular aneurysm, the 2004 ACC/AHA guidelines on STEMI gave a class IIa recommendation (Level of Evidence: B) to consider aneurysmectomy during CABG when intractable ventricular arrhythmia and or heart failure unresponsive to conventional therapies.72 These recommendations were also endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology.45, 72 Surgical techniques aim at restoring the LV physiologic geometry include plication, excision, with linear repair, and ventricular reconstruction with endoventricular patches.72 The 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines did not specify any level of recommendation for surgical repair, but the document suggested surgery for LV aneurysm in patients with refractory heart failure, ventricular arrhythmia not amenable to drugs or radiofrequency ablation, or recurrent thromboembolisms despite anticoagulation therapy.5

Percutaneous Repair

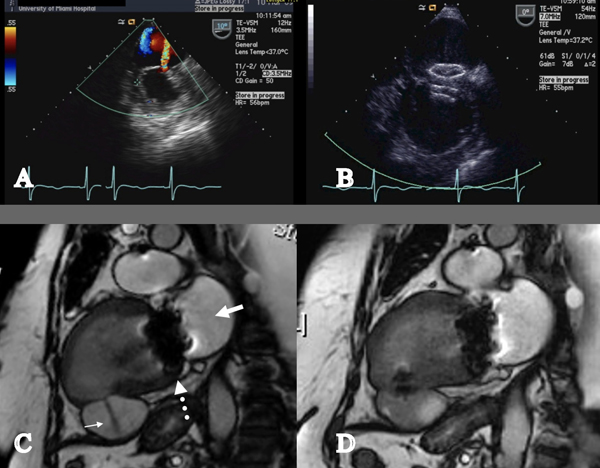

Percutaneous repair of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm via a retrograde approach across the aortic valve have been described usually involving general anesthesia.73–75 Under real-time transesophageal echocardiography (or other imaging modalities including simultaneous biplane fluoroscopy or reference MRI cine loop) and through an 8F Amplatzer delivery sheath, an IMA angiographic catheter is directed towards the jet of the orifice and a 0.035” Wholey High-Torque Plus guidewire (Covidien, Mansfield MA) can be used to gain access the neck of the pseudoaneurysm (Figure 4). A stiff guidewire then is inserted in the pseudoaneurysm through the angiographic catheter and then sheath and dilater can be advanced over this wire. In the example presented in Figure 4, a 15mm Amplatzer Septal Occluder (AGA Medical, Plymouth MN) was advanced across the neck; the distal disc and connecting waist were deployed and pulled back against the wall under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance. Spontaneous echo contrast (“smoke”) immediately appeared in the body of the pseudoaneurysm, indicating decreased flow and low shear forces upon the cellular blood elements. The proximal disc was then deployed, and the device was released (Figure 4). Imaging is likely to reveal several predictors of successful technical outcome of percutaneous closure, including the dimensions of the defect and thickness of the tissue at the rim. Predictors of clinical outcome (i.e., freedom from heart failure) may include the chronicity of the pseudoaneurysm and LV systolic function.

Figure 4.

Percutaneous repair of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. A. Transesophageal echocardiogram with color Doppler flow showing a thinned inferior wall infarction with a jet of flow into the large pseudoaneurysm; B. Transesophageal echocardiography showed the two discs of the occluder device seated across the defect. Spontaneous echo contrast (“smoke”) indicated stasis in the pseudoaneurysm; C. Cardiac MRI showing akinetic inferior wall segment with a jet of flow into the pseudoaneurysm. The bioprosthetic mitral valve is seen. (Bold white arrow = Left atrium; Narrow white arrow = pseudoaneurysm; dotted white arrow = mitral valve.); D. Cardiac MRI seven days after implantation of the occluder device showed no flow into the pseudoaneurysm.

Transcatheter therapies to restore LV geometry for patients with left ventricular aneurysms were previously evaluated using the Parachute device (CardioKinetics, Inc). The PARACHUTE III study demonstrated high procedural success, but device related major adverse cardiovascular events were seen in 7.0% of patients. Because of these events, the PARACHUTE IV study was early terminated in June 2017 (NCT # NCT01614652) after enrolling 331 subjects. It is not known if evaluation of the device efficacy to prevent death or hospitalization for heart failure will continue in future.76

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

Left ventricular pseudoaneurysms are a rare complication of myocardial infarction representing rupture of the myocardium, contained by pre-existing pericardial adhesions, most commonly in the posterior or lateral walls of the heart.

Left ventricular pseuodaneurysms require a high index of suspicion for diagnosis and urgent surgical intervention is advised for all operative candidates, although little is known about the natural history of medically managed patients.

Pseudoaneurysm with small necks can repaired with pledgeted sutures buttressed by poplytetrafluoroethylene felt, but Gore-Tex, pericardium, or a double patch Dacron can also be utilized to repair the defect with good surgical outcomes.

Utilizing a “Heart Team” approach to management, percutaneous repair can be considered in centers with structural heart disease expertise.

CARDIAC REPLACEMENT THERAPY

In patients who are not suitable candidates for surgical and transcatheter therapies, including those with significant biventricular failure and with associated end organ impairment, evaluation for orthotopic heart transplantation or mechanical circulatory support may be considered. The new UNOS transplant allocation system gives preference to patients on full circulatory support with VA-ECMO. Increasing number of patients are undergoing orthotopic heart transplantation while on full circulatory support (INTERMACS 1 or SCAI E).77 While concerns linger regarding perioperative mortality in these patients, this therapeutic option may be a successful bridge or destination therapy for select patients with mechanical complications of AMI if surgery or catheter-based therapies are not feasible.78

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Mechanical complications usually present with hemodynamic instability initially or following admission for AMI. Early diagnosis is critical, and a high degree of clinical suspicion is warranted. Table 2 highlights other clinical conditions that may be considered in the clinical differential.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis for mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction.

| Common Clinical Scenarioα | Features | Diagnosis | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrelated to Acute Myocardial Infarction | ||||

| Dynamic LVOT obstruction | (1) As a manifestation of Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Hypotension exacerbated by vasopressor use, systolic murmur in the left ventricular outflow tract, frequently accompanied by systolic murmur of MR at apex. | Bedside echocardiography | - Judicious use of intravascular volume resuscitation and beta blockade |

| (2) In the setting of inotrope/vasopressor use | - Discontinue IV vasodilators and inotropes | |||

| (3) Stress Induced Cardiomyopathy | - Use of phenylephrine or vasopressin as a vasoconstrictor | |||

| Acute pulmonary embolism | Predisposing factor to PE or history of established DVT | Hypotension, tachycardia with clear lung field, with SOB and a significant alveolar-arterial gradient. | CT PE protocol +/− echocardiogram | - Activation of Pulmonary Embolism Response Team for consideration of medical, surgical or catheter-based intervention. |

| Acute valvular emergency | (1) Acute severe mitral regurgitation | Symptoms of left ventricular failure and auscultatory features of valve insufficiency, with orthopnea, tachycardia as primary features. | Bedside echo with low threshold to perform TEE. | - Medical stabilization/resuscitation |

| (2) Acute severe Aortic regurgitation | Fluoroscopy or cine-CT for mechanical valves. | - Initiation of antibiotics if endocarditis related | ||

| (3) Acute Prosthetic Valve failure | Prosthetic metallic valve may have absent click | - Possible surgery/structural intervention. | ||

| Cardiac Tamponade | Predisposing factor to tamponade | Hypotension, tachycardia, jugular venous distension, pulsus paradoxicus | Bedside echo, TEE if post-surgery and localized tamponade. | - Pericardiocentesis or surgical exploration as dictated by underlying etiology |

| Septic Shock | Predisposing factor to septic shock | Hypotension, tachycardia, elevated lactate Possible fever and leukocytosis | Echo/TEE to evaluate septic focus | - Correction of intravascular status |

| - Appropriated anti-microbial therapy | ||||

| - Vasoactive drugs for hemodynamic support | ||||

| - surgical intervention or device removal if indicated. | ||||

| Acute Aortic Dissection | Type A dissection complicated by acute severe AI, acute coronary ischemia or pericardial tamponade. | Findings supportive of a dissection along with either murmur of aortic regurgitation, clinical findings of tamponade. | CT Aorta +/− Echo | - Absolute contraindication to antiplatelet medication / anticoagulants |

| - BP reduction and reducing shear stress with BB | ||||

| - Emergent surgery | ||||

| Related to AMI | ||||

| LV predominant cardiogenic shock | Large LAD myocardial infarction or new infarction in setting of a prior ischemic cardiomyopathy. | Hypotension, tachycardia, pulmonary edema, oliguria, peripheral hypoperfusion. | Echo, coronary angiography with confirmatory right heart catheterization findings if performed. | - Revascularization as dictated by coronary anatomy |

| - Possible temporary LV mechanical circulatory support. | ||||

| RV predominant cardiogenic shock | Usually in the setting of RCA infarction with RV involvement. | EKG findings, hypotension, relatively clear lungs, elevated JVD | Echo, coronary angiography with confirmatory right heart catheterization findings if performed | - Revascularization |

| - Possible institution of temporary RV mechanical support if indicated. | ||||

| Dynamic LVOT obstruction | Dynamic LVOT obstruction in setting of a large LAD infarction. | LVOT murmur occasionally accompanied by systolic MR murmur | Echo | - Judicious use of intravascular volume resuscitation and beta blockade and |

| - Discontinue IV vasodilators and inotropes | ||||

| - Use of phenylephrine or vasopressin as a vasoconstrictor | ||||

| Occult blood loss | Occult blood loss | Hypotension, reflex tachycardia may be blunted by beta blockade, decrease in hematocrit | CT looking for occult bleed, commonly RP, GI is a common source; endoscopy/colonoscopy. | - Stabilization and transfusion as needed, treat the primary bleeding source. |

| Drug Related | In setting of overzealous beta blockade or ACEi, IV NTG in a preload sensitive or intravascularly depleted state. | Hypotension | High clinical suspicion | - Modify pharmacotherapy as indicated. |

Abbreviations: AMI = Acute Myocardial Infarction; MR = Mitral Regurgitation; IV = intravenous; DVT = deep venous thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolism; CT = computed tomography; TEE = transesophagreal echocardiography; AI = aortic insufficiency; LAD = left anterior descending artery; LV = left ventricle; RCA = right coronary artery; JVD = jugular venous distension; RV = right ventricle; LVOT = left ventricle outflow tract; Echo = Echocardiography; RP = Retroperitoneal; GI = gastrointestinal; ACEi = Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; NTG = Nitroglycerin.

Predisposing factors indicate clinical symptoms, signs, laboratory, and imaging characteristics suggestive of each clinical condition

DECISION-MAKING AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM-BASED APPROACH

Heightened recognition of the complexities associated with contemporary cardiovascular care has led to a reappraisal of management practices and staffing requirements within the modern CICU.79 Multi-organ system injury is now commonplace79, 80, and often requires multidisciplinary input for optimal management. Shared decision-making, orchestrated by a critical care-trained physician, has been shown to enhance collaboration and communication81, streamline transitions of care, and even improve patient survival.82 Patient-centered, team-based care can also optimize adherence to best practice guidelines, decrease adverse events83, reduce costs-of-care, and result in patient and family statistfaction.81

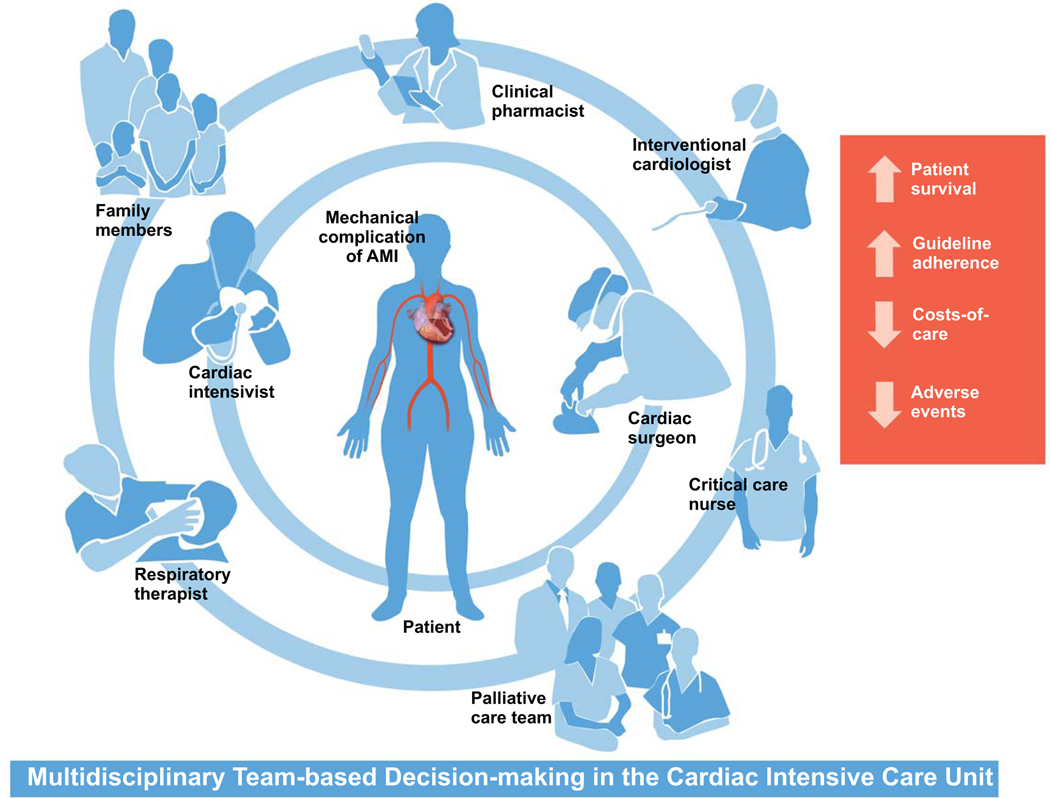

Patients with mechanical complications of AMI are at high-risk for multisystem sequelae, will frequently require critical care support for end-organ dysfunction, and are likely to benefit from a team-based approach for decision-making in the CICU. Mechanical complications have a spectrum of presentation for clinical acuity ranging from minimally symptomatic to cardiogenic shock; in patients with Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention stage B through E shock, we suggest that multidisciplinary shock team assessment and management has the potential to improve clinical coutcomes.84, 85 In addition to the aforementioned cardiac intensivist, these collaborative care teams will include nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, interventional cardiologists, cardiovascular surgeons, social workers, dieticians, and others (Figure 5). In most cases, mechanical complications of AMI are surgical emergencies and need an emergent surgical consultation to avoid undue delays for medical optimization. The multidisciplinary “Heart Team” discussion is critically important in non-straightforward cases. Palliative care experts and geriatricians will be frequently called upon to help determine patient-centered goals-of-care and to assist in end-of-life discussions.86 Patients and family members are pivotal partners in treatment decision-making.87, 88 In response, critical care societies have emphasized the importance of including well-delineated patient and family engagement pathways as part of routine intensive care delivery – this may include such practices as the engagement of patients and families during team rounds and the presence of family members during cardiopulmonary resuscitative efforts.89 Figure 5 summarizes and illustrates key perspectives necessary for optimal treatment decision-making and team-based care for critically ill patients with mechanical complications of AMI. It should be noted that these principles should not only include patients with mechanical complications in the CICU only, but they also include these patients if they were cared for in the emergency room, medical ICU, and surgical intensive care unit. Figure 6 highlights a treatment pathway for management of stable and unstable mechanical complications of AMI.

Figure 5.

Multidisciplinary team-based approach to mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction.

Figure 6.

A treatment pathway for management of stable and unstable mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). For unstable patients, consultation with the Shock Team can be considered prior to inter-hospital transfer to determine immediate medical management and possible candidacy for surgical and/or interventional treatment. In unstable patients where the risk of inter-hospital transfer may be prohibitive, alternative on-site therapies and/or inter-hospital transfer strategies can be considered in patients who are not surgical candidates only after discussion with the multidisciplinary Shock Team based on local on-site expertise and characteristics of the regional systems-of-care.

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

Most mechanical complications of AMI are surgical emergencies. Early involvement of the cardiac surgeon to discuss optimal timing of surgery is of paramount importance.

Multidisciplinary team, including cardiac intensivist, have the potential to improve adherence to best practice recommendations, decrease adverse events, and increase patient survival.

The prevalence of multisystem organ injury in patients with mechanical complications of AMI is high; hence, multidisciplinary collaboration may be required for optimal care.

Multidisciplinary teams, that include cardiac intensivist, have the potential to improve adherence to best practice recommendations, decrease adverse events, and increase patient survival.

Patients, family members, and palliative care specialists should be actively engaged in treatment decision-making within the CICU.

PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative care is a medical specialty that emphasizes interprofessional team, patient- and family-centered care with the goal of optimizing quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating symptoms.90 In critically ill cardiac patients, such as those experiencing mechanical complications of AMI, palliative care specialists can play a vital role in identifying the patient’s and family’s values and care preferences, which can then be matched with appropriate cardiac, life-sustaining, and comfort care treatment options. Values-based decision making and goals of care are tantamount to patient- and family-centered care, regardless of evidence of a therapy’s effectiveness in a given population.91 Palliative care consultation can provide value-added service to the multidisciplinary team by helping to balance potentially evidence-based treatment choices with individual patient and family cultural, spiritual, and quality of life contexts.91

Although numerous guidelines and reviews have recommended integration of palliative care for all patients with advanced stage cardiac conditions, regular use has been low.5, 28, 91, 92 In a nationwide sample of almost a million AMI patients from 2002–2016, palliative care consultation increased over time but still averaged only 1.3%. Even for high risk patients, like those with cardiogenic shock who experience an estimated 30–40% in-hospital mortality, consultation rate was only 6.5%.93 Another large, contemporary study found that only 2.5% of all AMI patients and 24% of AMI patients who died had palliative care specialist consultations.94

Barriers to palliative care use include patients’ uncertain prognosis, lack of understanding of risks and benefits of therapy, and conflation of palliative care with hospice and death.28, 92, 93, 95 These biases likely explain the common use of palliative care only when death seems certain.93 Professional societies have begun to identify appropriate triggers for palliative care referral, including the presence of advanced heart failure and objective, subjective, and patient-centric markers of critical cardiac illness.92, 95 Based on indicators and potential benefits of decision support, values-based care, symptom control, quality of life, and resource use, extrapolated from many critical cardiac conditions, regular referral to palliative care for patients with mechanical complications of AMI is currently routine practice in many centers.28, 91–95

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

The role of palliative care in mechanical complications of AMI includes symptom control and eliciting patient and family values and care preferences, while helping to match those with available, effective cardiac, life-sustaining, and comfort care treatments.

Palliative care consultation should be considered early in the evolution of AMI especially if risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality are high.

Evidence is limited but, in some AMI mechanical complications (e.g., cardiogenic shock and pump failure) palliative care consultation is associated with improved symptom control, quality of life, more do not resuscitate orders, and lower resource use, suggesting that palliative care consultation may result in less use of medically ineffective care.

GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE

Mechanical complications are rare and occur in <1% of patients with AMI. Their presentation is acute and requires a high intensity of care and clinical expertise, available only in select tertiary or quaternary care centers. Therefore, systematic enrollment of these patients in pragmatic clinical trials to develop pathways of care is extremely challenging. The variability in care of patients with mechanical complications is influenced by factors, such as difficulties in early diagnosis, limited availability of left ventricular assist devices, experienced multidisciplinary teams, risk-averse medical behaviors, and lack of equipoise among physicians caring for these patients. In this setting, randomized controlled trials become exceptionally difficult to perform, likely with unrepresentative patient samples. However, reliance on observational data is not satisfactory. Mechanical complications could be studied in a similar fashion as rare diseases, with study designs that require only a fraction of the number of subjects necessary for an adequately powered randomized controlled trial.96 Because of similarities in the presentation and early mortality rate between mechanical complications and aortic dissection, a registry similar to the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection, in selected referral centers could shed light and help develop pathways of care for the diagnosis and management of mechanical complications.97

Multiple gaps remain in the care of mechanical complications of AMI (Table 3); these include the role of point of care echocardiography in the initial assessment of complicated infarcts, use of other imaging modalities such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, the role and timing of new temporary left ventricular support devices or ECMO, and the timing of corrective intervention, either percutaneous or surgical. Of note, the surge of new procedures for structural heart disease could be extended to the management of mechanical complications, including customized solutions using three-dimensional printing technology.98

Table 3.

Priorities for Future Research on Mechanical Complications of Acute Myocardial Infarction.

| Research Domain | Specific Research Need | Proposed Study Design |

|---|---|---|

| Prognosis | Generating and evaluating parsimonious risk scores to examine short- and intermediate-term mortality | Prospective cohort or pragmatic trial |

| Integration of frailty, cognitive assessment, and comorbidity measure for assessment of patients unlikely to benefit from invasive care (i.e. futility) | Prospective cohort | |

| Monitoring | Defining the potential role and therapeutic targets of invasive hemodynamic monitoring in the cardiac and surgical intensive care units | Prospective cohort or pragmatic trial |

| Systems of Care | Studying whether specialized centers dedicated to care of mechanical complications can improve health outcomes (i.e. evidence-based algorithms that can be applied broadly) | Prospective cohort |

| Management | Examination of comparative effectiveness of mitral valve replacement versus repair for acute MR secondary PMR | Pragmatic trial |

| Defining the optimal timing of surgical intervention (early vs late; stable vs unstable; with vs without ECMO) | Pragmatic trial | |

| Studying the benefits of vasodilator therapy and/or use of IABP for afterload reduction for hemodynamically stable patients with PMR or VSD as a bridge to therapy | Prospective cohort or pragmatic trial | |

| Examination of role of different percutaneous LV support devices in different mechanical complication of AMI. | Pragmatic trial | |

| Decision Support and Palliative Care | Assessing the role of palliative care consultation and decision support for patients with mechanical complications on patient, family, and healthcare system outcomes. | Prospective cohort |

| Evaluating healthcare utilization among health care systems that frequently utilize palliative care services for care of complex cardiac patients with mechanical complications | Prospective cohort | |

| Identifying “triggers” for routine involvement of palliative care specialists in care of patients with mechanical complications | Prospective cohort |

Abbreviations: IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; MR: Mitral regurgitation; PMR: Papillary Muscle Rupture; CICU = Cardiac Intensive Care Unit; LV = left ventricle; ECMO = Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation.

CONCLUSION

Mechanical complications of AMI are high acuity and time sensitive conditions associated with high morbidity and mortality. We propose that early recognition, diagnosis, and multidisciplinary stakeholder involvement in medical resuscitation and stabilization together with patient-centered planning and timing of appropriate surgical intervention, percutaneous technologies, mechanical circulatory support, and palliative specialist support has the potential to improve disease- and patient-centered outcomes. We acknowledge the paucity of controlled studies in these infrequent conditions and we advocate for more collaborative international efforts to develop registries and conduct pragmatic trials to address the identified knowledge gaps and guide the optimal treatment strategies and pathways.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damluji AA, Bandeen-Roche K, Berkower C, Boyd CM, Al-Damluji MS, Cohen MG, Forman DE, Chaudhary R, Gerstenblith G, Walston JD, Resar JR and Moscucci M. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Older Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1890–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson ED, Shah BR, Parsons L, Pollack CV Jr., French WJ, Canto JG, Gibson CM and Rogers WJ. Trends in quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1045–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damluji AA, Forman DE, van Diepen S, Alexander KP, Page RL 2nd, Hummel SL, Menon V, Katz JN, Albert NM, Afilalo J, Cohen MG, American Heart Association Council on Clinical C, Council on C and Stroke N. Older Adults in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit: Factoring Geriatric Syndromes in the Management, Prognosis, and Process of Care: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e6–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW and American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P and Widimsky P. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017;70:1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, Canto JG, Ornato JP, Gibson CM, Pollack CV Jr.,, Gore JM, Chandra-Strobos N, Peterson ED and French WJ. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1026–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puerto E, Viana-Tejedor A, Martínez-Sellés M, Domínguez-Pérez L, Moreno G, Martín-Asenjo R and Bueno H. Temporal Trends in Mechanical Complications of Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French JK, Hellkamp AS, Armstrong PW, Cohen E, Kleiman NS, O’Connor CM, Holmes DR, Hochman JS, Granger CB and Mahaffey KW. Mechanical complications after percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (from APEX-AMI). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreyra AE, Huang MS, Wilson AC, Deng Y, Cosgrove NM, Kostis JB and Group MS. Trends in incidence and mortality rates of ventricular septal rupture during acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1095–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SV, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Gersh BJ and Jollis JG. Socioeconomic Status and Outcome Following Acute Myocardial Infarction in Elderly Patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1128–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elbadawi A, Elgendy IY, Mahmoud K, Barakat AF, Mentias A, Mohamed AH, Ogunbayo GO, Megaly M, Saad M, Omer MA, Paniagua D, Abbott JD and Jneid H. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Mechanical Complications in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1825–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsweig AM, Wang Y, Forrest JK, Cleman MW, Minges KE, Mangi AA, Aronow HD, Krumholz HM and Curtis JP. Ventricular septal rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction: Incidence, treatment, and outcomes among medicare beneficiaries 1999–2014. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:1104–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988;2:349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keeley EC, Boura JA and Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grines CL, Browne KF, Marco J, Rothbaum D, Stone GW, O’Keefe J, Overlie P, Donohue B, Chelliah N, Timmis GC and et al. A comparison of immediate angioplasty with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. The Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:673–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs AK, Antman EM, Faxon DP, Gregory T and Solis P. Development of systems of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients: executive summary. Circulation. 2007;116:217–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jollis JG, Al-Khalidi HR, Roettig ML, Berger PB, Corbett CC, Doerfler SM, Fordyce CB, Henry TD, Hollowell L, Magdon-Ismail Z, Kochar A, McCarthy JJ, Monk L, O’Brien P, Rea TD, Shavadia J, Tamis-Holland J, Wilson BH, Ziada KM and Granger CB. Impact of Regionalization of ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care on Treatment Times and Outcomes for Emergency Medical Services-Transported Patients Presenting to Hospitals With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Mission: Lifeline Accelerator-2. Circulation. 2018;137:376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damluji AA, Myerburg RJ, Chongthammakun V, Feldman T, Rosenberg DG, Schrank KS, Keroff FM, Grossman M, Cohen MG and Moscucci M. Improvements in Outcomes and Disparities of ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care: The Miami-Dade County ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Network Project. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda S, Asaumi Y, Yamane T, Nagai T, Miyagi T, Noguchi T, Anzai T, Goto Y, Ishihara M, Nishimura K, Ogawa H, Ishibashi-Ueda H and Yasuda S. Trends in the clinical and pathological characteristics of cardiac rupture in patients with acute myocardial infarction over 35 years. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figueras J, Alcalde O, Barrabés JA, Serra V, Alguersuari J, Cortadellas J and Lidón RM. Changes in hospital mortality rates in 425 patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and cardiac rupture over a 30-year period. Circulation. 2008;118:2783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanz J, Wyss D, Raber L, Stortecky S, Hunziker L, Blochlinger S, Reineke D, Englberger L, Zanchin T, Valgimigli M, Heg D, Windecker S and Pilgrim T. Mechanical complications in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A single centre experience. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0209502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tehrani BN, Truesdell AG, Psotka MA, Rosner C, Singh R, Sinha SS, Damluji AA and Batchelor WB. A Standardized and Comprehensive Approach to the Management of Cardiogenic Shock. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, Wilcox R, Danays T, Lambert Y, Sulimov V, Rosell Ortiz F, Ostojic M, Welsh RC, Carvalho AC, Nanas J, Arntz H-R, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Grajek S, Fresco C, Bluhmki E, Regelin A, Vandenberghe K, Bogaerts K and Van de Werf F. Fibrinolysis or Primary PCI in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1379–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhardwaj B, Sidhu G, Balla S, Kumar V, Kumar A, Aggarwal K, Dohrmann ML and Alpert MA. Outcomes and Hospital Utilization in Patients With Papillary Muscle Rupture Associated With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125:1020–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valle JA, Miyasaka RL and Carroll JD. Acute Mitral Regurgitation Secondary to Papillary Muscle Tear: Is Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Mitral Valve Repair a New Paradigm? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gueret P, Khalife K, Jobic Y, Fillipi E, Isaaz K, Tassan-Mangina S, Baixas C, Motreff P, Meune C and Study I. Echocardiographic assessment of the incidence of mechanical complications during the early phase of myocardial infarction in the reperfusion era: a French multicentre prospective registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG, American Heart Association Council on Clinical C, Council on C, Stroke N, Council on Quality of C, Outcomes R and Mission L. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e232–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alviar CL, Rico-Mesa JS, Morrow DA, Thiele H, Miller PE, Maselli DJ and van Diepen S. Positive Pressure Ventilation in Cardiogenic Shock: Review of the Evidence and Practical Advice for Patients With Mechanical Circulatory Support. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:300–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, Ferenc M, Olbrich HG, Hausleiter J, Richardt G, Hennersdorf M, Empen K, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, Hambrecht R, Fuhrmann J, Böhm M, Ebelt H, Schneider S, Schuler G and Werdan K. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1287–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiVita M, Visveswaran GK, Makam K, Naji P, Cohen M, Kapoor S, Saunders CR and Zucker MJ. Emergent TandemHeart-ECMO for acute severe mitral regurgitation with cardiogenic shock and hypoxaemia: a case series. European Heart Journal - Case Reports. 2020;4:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson CR, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, Antonelli TA, Webb JG, Jaber WA, Abel JG and Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock due to acute severe mitral regurgitation complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we use emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acker MA, Parides MK, Perrault LP, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns AC, Voisine P, Smith PK, Hung JW, Blackstone EH, Puskas JD, Argenziano M, Gammie JS, Mack M, Ascheim DD, Bagiella E, Moquete EG, Ferguson TB, Horvath KA, Geller NL, Miller MA, Woo YJ, D’Alessandro DA, Ailawadi G, Dagenais F, Gardner TJ, O’Gara PT, Michler RE and Kron IL. Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaneko T, Aranki S, Javed Q, McGurk S, Shekar P, Davidson M and Cohn L. Mechanical versus bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement in patients <65 years old. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chikwe J, Chiang YP, Egorova NN, Itagaki S and Adams DH. Survival and outcomes following bioprosthetic vs mechanical mitral valve replacement in patients aged 50 to 69 years. JAMA. 2015;313:1435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SK, Heo W, Min HK, Kang DK, Jun HJ and Hwang YH. A New Surgical Repair Technique for Ischemic Total Papillary Muscle Rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1891–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilic A, Sultan I, Chu D, Wang Y and Gleason TG. Mitral Valve Surgery for Papillary Muscle Rupture: Outcomes in 1342 Patients from the STS Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeter T, Lehmann S, Misfeld M, Borger M, Subramanian S, Mohr FW and Bakthiary F. Clinical outcome after mitral valve surgery due to ischemic papillary muscle rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:820–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, Kar S, Lim DS, Mishell JM, Whisenant B, Grayburn PA, Rinaldi M, Kapadia SR, Rajagopal V, Sarembock IJ, Brieke A, Marx SO, Cohen DJ, Weissman NJ, Mack MJ and Investigators C. Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]