Abstract

In late 2019, SARS-CoV-2 caused the greatest global health crisis in a century, impacting all aspects of society. As the COVID-19 pandemic evolved throughout 2020 and 2021, multiple variants emerged, contributing to multiple surges in cases of COVID-19 worldwide. In 2021, highly effective vaccines became available, although the pandemic continues into 2022. There has been tremendous expansion of basic, translational, and clinical knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 since the pandemic’s onset. Treatment options have been rapidly explored, attempting to repurpose preexisting medications in tandem with development and evaluation of novel agents. Care of the seriously ill patient is examined.

Keywords: COVID-19, Treatment, Critical care

Key points

-

•

High-quality supportive ICU care is paramount, including established therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

-

•

Therapeutic interventions for COVID-19 include virologic and immunologic therapies.

-

•

COVID-19 can be complicated by thromboembolic events and multisystem inflammatory syndrome.

Introduction

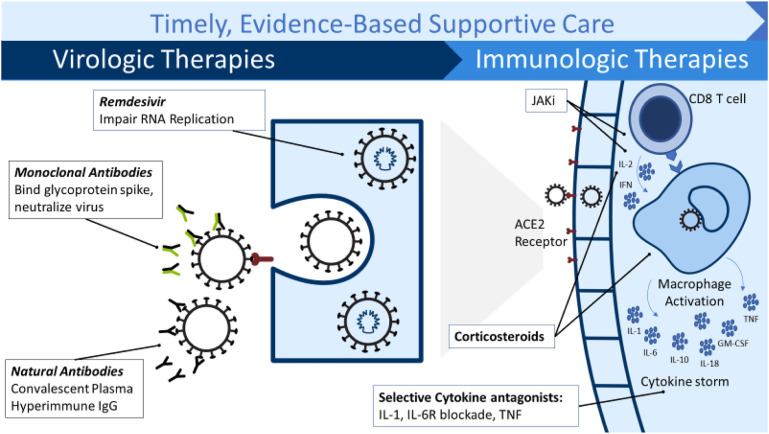

Common COVID-19 symptoms include fever, dyspnea, cough, and fatigue. Dyspnea is more often reported by those who develop severe infection and correlates with worse prognosis.1 , 2 COVID-19 disease results in a dynamic balance between antiviral immune defense and excessive inflammation, often conceptualized into a biphasic disease: an initial “viral phase” followed by either recovery or a “hyperinflammatory phase” driven by host-mediated organ damage resulting in severe illness, sometimes referred to as “cytokine storm.”3 Histopathologic evidence has demonstrated end-organ damage even in the absence of viral particles, supporting the notion that excessive host response contributes to mortality.4 In general, virus-targeted therapies tend to be most effective early in disease and host-focused or inflammatory focused therapies tend to be most effective later in the course of illness. In addition to the “biphasic model,” distinction has emerged over the past year regarding patient serologic status and viral load in relation to therapeutic efficacy. Notably, a subset of patients are unable to limit viral replication, and this inability to control the virus may contribute to the development of respiratory failure. Thus, although antivirals are most effective early in the disease, subgroups of patients with severe or critical disease may benefit from antiviral therapy (Fig. 1 ).5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 therapies for severely ill patients. GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IgG, immunoglobulin G; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

(Courtesy of Brandon Webb, MD, Intermountain Healthcare).

Morta among critically ill patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation have varied significantly throughout the pandemic. Contemporary meta-analysis suggests that mortality in this population is around 45%, although notable heterogeneity exists among published cohorts.10 , 11 Several studies have detected an association between increased mortality and case load or patient volumes, suggesting an impact of limited resources on outcomes.12 , 13

Supportive care

The mainstay of treatment for all critically ill patients is high-quality supportive intensive care unit (ICU) care. In the most severe cases of COVID-19, patients develop acute respiratory failure meeting the Berlin definition14 of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): (1) acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, (2) onset within 7 days, (3) bilateral opacities on imaging, (4) cardiac failure not the primary cause of respiratory failure. Early in the pandemic, some observers suggested that COVID-19 pneumonia did not cause “typical” ARDS based on the observation of relatively well-preserved lung mechanics despite severe hypoxemia.15 , 16 However, other observers noted that prepandemic ARDS also had patients with near-normal compliance despite hypoxemia. Instead of a different ARDS specific to COVID-19, there is rising recognition that ARDS per se exists along a physiologic continuum.17 As a consequence, standard ARDS therapies remain a critical part of treatment for severely ill COVID-19 patients. Invasive mechanical ventilation is a common therapy used to sustain patients with respiratory failure. However, mechanical ventilation can both improve survival and cause further lung damage. To best optimize outcomes, low-tidal-volume ventilation should be used, targeting 6 mL/kg predicted body weight.18 , 19 Additional mechanical ventilation therapies to prioritize include targeting higher rather than lower positive end-expiratory pressure and limiting plateau pressure to ≤30 cmh 2 o.18 , 20 Early prone positioning of intubated patients improves survival and has been an established therapy for patients with severe ARDS before the pandemic.21 Although separate trials have not been performed in COVID-19 ARDS, prone positioning for patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 ARDS is in common use around the world. Restricted fluid management whereby fluid intake is limited and urinary output is increased also improves patient outcomes.22 , 23

The best noninvasive respiratory support strategy in patients not being treated with invasive mechanical ventilation remains unclear. The FLORALI trial, conducted before COVID-19, found significant mortality benefit from the use of high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure compared with standard oxygen or noninvasive ventilation.24 However, the RECOVERY-RS trial in patients with COVID-19–related acute respiratory failure identified a significant decrease in intubation and mortality with the use of continuous positive airway pressure compared with HFNO or conventional oxygen.25 Of note, RECOVERY-RS was not a study of the use of non-invasive ventilation for “rescue” of patients failing HFNO. Based on experience with intubated patients, many institutions have proposed prone positioning for nonintubated patients,26 , 27 but data supporting this practice are controversial at best.28, 29, 30 Although the role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in the treatment of ARDS remains unclear,31 ECMO has been adopted as a rescue therapy option for management of severely ill COVID-19 patients at many institutions around the world.32 , 33 This widespread adoption of ECMO has occurred without supporting trial evidence.

COVID-19–specific therapies

Pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 includes acute pneumonitis with extensive opacities, diffuse alveolar damage, and microthrombosis.34 Additional host immune response is thought to play a role in perpetuating organ failure as evidenced by elevated inflammatory markers, such as ferritin, C-reactive protein, interleukin-1 (IL-1), and IL-6.35 , 36 Early in the pandemic, therapeutic interventions targeting inflammatory organ injury were proposed, and the value of glucocorticoids was widely debated. Data regarding use of corticosteroids in viral respiratory infections before COVID-19 were mixed, and differing conclusions were drawn from meta-analysis.37 , 38 GLUCOCOVID, an open-label trial, evaluated a 6-day course of methylprednisolone in 91 patients with SARS-CoV-2 receiving oxygen and evidence of systemic inflammation. This study suggested improved mortality but was severely underpowered.39 More than 6000 patients were included in the RECOVERY trial, comparing up to 10 days of low-dose dexamethasone versus usual care. Dexamethasone was associated with decreased 28-day mortality among hospitalized patients, with the largest benefit in patients receiving supplemental oxygen and invasive mechanical ventilation (the trial did not distinguish conventional oxygen from HFNO).40 A meta-analysis of other smaller trials suggested similar mortality benefit with glucocorticoids.41 Therefore, glucocorticoids are now a mainstay of therapy for severely ill COVID-19 patients and is the only treatment with a strong recommendation in multiple international guidelines.42, 43, 44

The pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 plus the apparent benefit of glucocorticoids suggests that other immunomodulatory therapies may be beneficial. Tocilizumab is a recombinant anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody that inhibits the binding of IL-6 to receptors. Tocilizumab is licensed for autoimmune diseases, including cytokine release syndrome. Tocilizumab in COVID-19 has yielded strangely mixed results: placebo-controlled trials have been largely negative, whereas pragmatic unblinded trials suggested benefit in severe disease.45, 46, 47, 48, 49 The largest trial included more than 4000 patients enrolled in the RECOVERY platform who were hospitalized and had evidence of systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein ≥75 mg/L). In this study, the addition of tocilizumab improved survival and other clinical outcomes, which persisted after control for level of respiratory support and concurrent systemic corticosteroids (82% of patients also received corticosteroids).48 In addition, the pragmatic platform trial REMAP-CAP investigated both tocilizumab and sarilumab (another IL-6 receptor antagonist) in ∼800 critically ill patients who were receiving organ support. IL-6 antagonists resulted in improved survival, increased organ support-free days, and other clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, several small to moderately sized randomized, placebo-controlled trials of hospitalized patients found no clinical benefit of tocilizumab.46 , 47 , 50 Whether this discrepancy reflects type 2 error in the placebo-controlled trials, differences in target populations, or differences in therapeutic context is not clear. Given the lack of large safety signals, IL-6 antagonists may well be appropriate therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19, particularly when started early in the course.

Remdesivir is a broad-spectrum antiviral with activity against coronaviruses. As a prodrug, it is converted to an adenosine analogue and acts as an inhibitor of the RNA polymerase found in SARS-CoV-2, which inhibits viral replication. Based on the PINETREE trial,51 all major guidelines recommend remdesivir in nonsevere COVID-19 patients at high risk of hospitalization. Although the World Health Organization guidelines do not recommend remdesivir for hospitalized patients,44 both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend the use of remdesivir for hospitalized patients receiving supplemental oxygen.42 , 44 , 52 In patients receiving mechanical ventilation, the IDSA guidelines give a conditional recommendation against the routine initiation of remdesivir, whereas the NIH guidelines acknowledge differing opinions of panel members given the limited evidence. In 2 studies conducted predominantly in North America, remdesivir shortened the time to clinical improvement and reduced the likelihood for mechanical ventilation compared with placebo, with nonsignificant trends toward improved mortality.53 However, improvement in mortality was not identified in international, pragmatic, open-label trials and one small, placebo-controlled trial conducted in China early in the pandemic.54, 55, 56 Although most studies evaluated 10 days of therapy, 2 studies found comparable outcomes between patients randomized to 5 days or 10 days, and thus, many centers use shorter durations of therapy.57 , 58 Earlier trials excluded patients with renal and hepatic dysfunction; however, the rate of renal and hepatic adverse events is low; effects are reversible, and observational studies support its use in these patient populations.59 Although better data among critically ill patients would be useful, remdesivir appears reasonable to use, much as oseltamivir is commonly used in critically ill patients with influenza.

Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 inhibit intracellular signaling pathways of cytokines, known to be elevated in COVID-19, act against the virus, and prevent viral cellular entry.60, 61, 62 Baricitinib is an oral JAK 1 and 2 inhibitor, and, in combination with remdesivir, improves outcomes of hospitalized patients compared with remdesivir alone. In a multinational, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, patients who received baricitinib and remdesivir had improved time to recovery, clinical status at 15 days, and mortality. This benefit was most notable in severely ill patients requiring high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive ventilation.63 Although in this trial corticosteroids were not administered for the treatment of COVID-19, another multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-control trial found improved mortality when baricitinib was added to standard of care, which could include remdesivir (19% of participants) and dexamethasone (72% of participants).64 Tofacitinib is another oral JAK inhibitor, which has been found in a multicenter, randomized placebo-control trial to lower risk of death or respiratory failure when given to hospitalized patients in addition to standard of care.65 Overall, it appears that tofacitinib may have similar benefit to COVID-19 patients as baricitinib, although with the significantly smaller sample size, the level of certainty is lower.

Immune suppression with infliximab (a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor) and abatacept (a T-cell activation inhibitor) shows promising results in the randomized placebo-controlled ACTIV-1 trial. Compared with placebo, infliximab improved mortality with 40.5% lower adjusted odds of dying in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Similarly, hospitalized patients receiving abatacept had 37.4% lower adjusted odds of dying compared with placebo.66

Serostatus, viral load, or both may be key factors contributing to efficacy of some therapies. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies do not appear beneficial in “unselected” hospitalized patients.8 , 67 However, increasing data suggest benefit in seronegative patients (ie, those who have not mounted their own humoral immune response). RECOVERY found seronegative hospitalized patients who received the REGEN-COV monoclonal antibody combination (casirivmab 4 g intravenously [IV] and imdevimab 4 g IV) plus usual care had improved mortality. This benefit was not seen in seropositive hospitalized patients.68 Similarly, the ACTIV-3 bamlanivimab study group suggested difference in efficacy and safety of the monoclonal antibody bamlanivimab depending on serostatus and viral load, although the sample size was too small for definitive conclusions.8 Based on available evidence, it seems wise to avoid administration of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to seropositive inpatients. Where testing of serology is difficult to perform in a timely fashion, it may be difficult to administer such agents; valid point-of-care tests are an urgent priority.

Hypercoagulability together with severe inflammation related to COVID-19 infection is thought to contribute to multiorgan failure and death.69 Thrombotic events are commonly reported in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Incidence ranges from about 22% to 60% in ICU patients, often despite use of standard prophylactic anticoagulation.70, 71, 72 It is prudent to have a low threshold for evaluation for venous thromboembolism. Given the association of increased thrombotic risk in COVID-19, some early guidance recommended higher-dose anticoagulation for critically ill patients,73 despite a lack of evidence at the time. A multiplatform, randomized clinical trial in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 compared therapeutic-dose heparin anticoagulation with usual care thromboprophylaxis. In noncritically ill patients, full-dose anticoagulation met its endpoint of more organ-support–free days, largely owing to a decrease in the use of HFNO.74 However, full-dose anticoagulation was associated with a high likelihood of increased harm among critically ill patients receiving organ support.75 In addition, intermediate-dose prophylaxis did not result in improved outcomes compared with standard-dose prophylaxis.76 Therefore, based on the available evidence, standard thromboprophylaxis with diagnostic vigilance, rather than full-dose or intermediate-dose anticoagulation, should be used in critically ill patients with organ failure.

Limitations of all published studies include the constantly changing viral and therapeutic contexts of the pandemic, leading to a constantly changing standard of care (especially around immune suppression); limited data for most therapies in vaccinated patients; and a paucity of data for the most recent variants. Data suggest remdesivir maintains activity against Delta and Omicron77; however, as clinical disease varies, so may clinical effectiveness. Immunosuppressive agents are likely to remain effective across various strains; however, patient selection will remain critical to realize the intended benefits.

Critical shortages

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed critical supply shortages worldwide with a large influx of high-acuity patients requiring intensive care. The disruption in staff, equipment, and space contributes to complex interactions affecting patient care and outcomes.78 Capacity strain includes patient census and volume, turnover, acuity, and workload.78 Care of the critically ill patient requires a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, which can be challenging to replicate outside of traditional ICU settings when space becomes limited. Observational studies have demonstrated a relationship between strain on ICU resources and ICU patient outcomes. This can come in the form of ICU triage decisions,79 , 80 adherence to guidelines,81 timing of end-of-life discussions,82 and mortality.83 Despite the detrimental impact of strain and resource limitation, a counter-phenomenon is seen in the form of adaptation, whereby care and outcomes of patients improve over time through real-time learning.78 This has been observed during the COVID-19 pandemic with decline in mortality over time, although population immunity and improved treatments also played a role in decreasing mortality over time.84, 85, 86 As disruptions in availability of personnel, supplies, and space continue, health care systems will continue to find ways to mitigate the impact of capacity strain on care delivery and outcomes.

Complications

Patients with COVID-19 are at risk for invasive fungal diseases, such as aspergillus and mucor. COVID-19–associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) is seen in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients and is associated with worse patient outcomes.87 , 88 The European Confederation for Medical Mycology and the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology developed consensus criteria for the diagnosis of proven, probable, and possible CAPA, which relies on a combination of microbiology, imaging, and clinical data.89 Of note, serum galactomannan alone is not reliable owing to low sensitivity, and radiographic imaging alone is not sufficient even in the presence of a halo sign. Recommended first-line treatment is either voriconazole or isavuconazole, with liposomal amphotericin B reserved for those with contraindications, poor response, or azole-resistant strains.

Another rare, poorly understood phenomenon is multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A). Similar to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), key features include recent COVID-19 infection, often after a period of recovery; elevated inflammatory markers; and multisystem end-organ damage. Although differentiating between MIS-A and a biphasic presentation of acute COVID-19 remains a challenge, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed diagnostic criteria.90 The CDC’s definition of MIS-A requires a fever plus rash with nonpurulent conjunctivitis or severe cardiac illness with additional clinical and laboratory criteria within the first 3 days of hospitalization. Patel and colleagues91 have published the largest case series to date (>200 patients with MIS-A), of which more than half were admitted to the ICU and received vasoactive medication for severe hypotension. No clear treatment recommendations have been established in adults, but given the similarities with MIS-C, treatment recommendations by the American College of Rheumatology for MIS-C are often used, which includes IV immunoglobulin plus corticosteroids as the backbone with intensification of immunomodulatory treatments, such as anakinra and infliximab, for poor responders.92

Summary

Since the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 treatment approaches have evolved substantially. Current standard of care for the COVID-19 patient in the ICU includes corticosteroids with or without remdesivir and secondary immunosuppression, in addition to high-quality supportive care. As scientific knowledge continues to grow, care of the critically ill patient with COVID-19 will continue to improve and evolve. Although there is still much to be learned about the optimal use of supportive care and COVID-19–specific therapies, it is a testament to modern medicine and the hard work of investigators around the world that treatment options are available.

Clinics care points

-

•

COVID-19 therapies include virologic and immunologic therapies with anti-viral medications having most therapeutic impactful earlier in the course of illness. Glucocorticoids are an important immunologic therapy targeting inflammatory organ injury.

-

•

Established acute respiratory distress syndrome therapies including lung protective ventilator management strategies, fluid management and prone positioning are important interventions.

-

•

Based on available evidence, standard dose thromboprophylaxis, rather than full-dose or intermediate-dose anticoagulation, should be used along with diagnostic vigilance in critically ill patients with organ failure.

Disclosure

Dr S.M. Brown reports royalties from Oxford University Press, research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, Faron, Sedana Medical, and Janssen, and payment for data safety monitoring board membership from New York University and Hamilton. Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McElvaney O.J., McEvoy N.L., McElvaney O.F., et al. Characterization of the Inflammatory Response to Severe COVID-19 Illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):812–821. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1583OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du R.H., Liu L.M., Yin W., et al. Hospitalization and Critical Care of 109 Decedents with COVID-19 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):839–846. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers J.D., Chotirmall S.H. Rewiring the Immune Response in COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):784–786. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202007-2934ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorward D.A., Russell C.D., Um I.H., et al. Tissue-Specific Immunopathology in Fatal COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(2):192–201. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202008-3265OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutmann C., Takov K., Burnap S.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and proteomic trajectories inform prognostication in COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23494-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermejo-Martin J.F., González-Rivera M., Almansa R., et al. Viral RNA load in plasma is associated with critical illness and a dysregulated host response in COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):691. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fajnzylber J., Regan J., Coxen K., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundgren J.D., Grund B., Barkauskas C.E., et al. Responses to a Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody for Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 According to Baseline Antibody and Antigen Levels: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(2):234–243. doi: 10.7326/M21-3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram-Mohan N., Kim D., Zudock E.J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia Predicts Clinical Deterioration and Extrapulmonary Complications from COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(2):218–226. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angriman F., Scales D.C. Estimating the Case Fatality Risk of COVID-19 among Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(1):3–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202011-4117ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim Z.J., Subramaniam A., Ponnapa Reddy M., et al. Case Fatality Rates for Patients with COVID-19 Requiring Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. A Meta-analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(1):54–66. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2405OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doidge J.C., Gould D.W., Ferrando-Vivas P., et al. Trends in Intensive Care for Patients with COVID-19 in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(5):565–574. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202008-3212OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churpek M.M., Gupta S., Spicer A.B., et al. Hospital-Level Variation in Death for Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(403–411):403–411. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202012-4547OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gattinoni L., Coppola S., Cressoni M., et al. COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a "Typical" Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care. 2020;24(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattinoni L., Gattarello S., Steinberg I., et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: pathophysiology and management. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30(162) doi: 10.1183/16000617.0138-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan E., Del Sorbo L., Goligher E.C., et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1253–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ARDSNetwork Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briel M., Meade M., Mercat A., et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(9):865–873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guérin C., Reignier J., Richard J.C., et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grissom C.K., Hirshberg E.L., Dickerson J.B., et al. Fluid management with a simplified conservative protocol for the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(2):288–295. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiedemann H.P., Wheeler A.P., Bernard G.R., et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frat J.P., Thille A.W., Mercat A., et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2185–2196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkins G.D., Ji C., Connolly B.A., et al. Effect of Noninvasive Respiratory Strategies on Intubation or Mortality Among Patients With Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure and COVID-19: The RECOVERY-RS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327(6):546–558. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor S.P., Bundy H., Smith W.M., et al. Awake Prone Positioning Strategy for Nonintubated Hypoxic Patients with COVID-19: A Pilot Trial with Embedded Implementation Evaluation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(8):1360–1368. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1164OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaiman T., Silvestri J.A., Srinivasan T., et al. Improving Prone Positioning for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome during the COVID-19 Pandemic. An Implementation-Mapping Approach. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(2):300–307. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-571OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson A.E., Ranard B.L., Wei Y., et al. Prone Positioning in Awake, Nonintubated Patients With COVID-19 Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1537–1539. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosén J., von Oelreich E., Fors D., et al. Awake prone positioning in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19: the PROFLO multicenter randomized clinical trial. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03602-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian E.T., Gatto C.L., Amusina O., et al. Assessment of Awake Prone Positioning in Hospitalized Adults With COVID-19: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(6):612–621. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X., Scales D.C., Kavanagh B.P. Unproven and Expensive before Proven and Cheap: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation versus Prone Position in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(8):991–993. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2216CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz R.A., Graf J., Zambrano J.M., et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for COVID-19-associated Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Chile: A Nationwide Incidence and Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(1):34–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202011-4166OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karagiannidis C., Strassmann S., Merten M., et al. High In-Hospital Mortality Rate in Patients with COVID-19 Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Germany: A Critical Analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(8):991–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202105-1145LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruan Q., Yang K., Wang W., et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell C.D., Millar J.E., Baillie J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shang L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):683–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corral-Gudino L., Bahamonde A., Arnaiz-Revillas F., et al. Methylprednisolone in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: An open-label randomized trial (GLUCOCOVID) Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(7–8):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., et al. Association Between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Infectious Disease Society of America IDSA Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/ Accessed 31 May 2022.

- 43.National Institutes of Health Clinical Management Summary. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/clinical-management-summary/?utm_source=site&utm_medium=home&utm_campaign=highlights Available at: Accessed May 31, 2022.

- 44.World Health Organization Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2022.3 Accessed 31 May 2022. [PubMed]

- 45.Salama C., Han J., Yau L., et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosas I.O., Diaz G., Gottlieb R.L., et al. Tocilizumab and remdesivir in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1258–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosas I.O., Bräu N., Waters M., et al. Tocilizumab in Hospitalized Patients with Severe Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10285):1637–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon A.C., Mouncey P.R., Al-Beidh F., et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonists in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stone J.H., Frigault M.J., Serling-Boyd N.J., et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottlieb R.L., Vaca C.E., Paredes R., et al. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe Covid-19 in Outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):305–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: Remdesivir. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antiviral-therapy/remdesivir/ Accessed May 31, 2022. [PubMed]

- 53.Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ader F., Bouscambert-Duchamp M., Hites M., et al. Remdesivir plus standard of care versus standard of care alone for the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (DisCoVeRy): a phase 3, randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(2):209–221. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan H., Peto R., Henao-Restrepo A.M., et al. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19 - Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldman J.D., Lye D.C.B., Hui D.S., et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1827–1837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spinner C.D., Gottlieb R.L., Criner G.J., et al. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients With Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1048–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Laar S.A., de Boer M.G.J., Gombert-Handoko K.B., et al. Liver and kidney function in patients with Covid-19 treated with remdesivir. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(11):4450–4454. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stebbing J., Krishnan V., de Bono S., et al. Mechanism of baricitinib supports artificial intelligence-predicted testing in COVID-19 patients. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(8):e12697. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sims J.T., Krishnan V., Chang C.-Y., et al. Characterization of the cytokine storm reflects hyperinflammatory endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoang T.N., Pino M., Boddapati A.K., et al. Baricitinib treatment resolves lower-airway macrophage inflammation and neutrophil recruitment in SARS-CoV-2-infected rhesus macaques. Cell. 2021;184(2):460–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.007. e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalil A.C., Patterson T.F., Mehta A.K., et al. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marconi V.C., Ramanan A.V., de Bono S., et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib for the treatment of hospitalised adults with COVID-19 (COV-BARRIER): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(12):1407–1418. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guimarães P.O., Quirk D., Furtado R.H., et al. Tofacitinib in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(5):406–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.NCfAT Sciences. Immue Modulator Drugs Improved Survival for People Hospitalized with COVID-19. https://ncats.nih.gov/news/releases/2022/Immune-Modulator-Drugs-Improved-Survival-for-People-Hospitalized-with-COVID-19 Available at: Accessed June 9, 2022.

- 67.Efficacy and safety of two neutralising monoclonal antibody therapies, sotrovimab and BRII-196 plus BRII-198, for adults hospitalised with COVID-19 (TICO): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00751-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Casirivimab and imdevimab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):665–676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P., et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., van Haaps T.F., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nopp S., Moik F., Jilma B., et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(7):1178–1191. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2020.; London: 2020. Clinical Guidelines. COVID-19 rapid guideline: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism in over 16s with COVID-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lawler P.R., Goligher E.C., Berger J.S., et al. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):790–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goligher E.C., Bradbury C.A., McVerry B.J., et al. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sadeghipour P., Talasaz A.H., Rashidi F., et al. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(16):1620–1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitts J., Li J., Perry J.K., et al. Remdesivir and GS-441524 retain antiviral activity against Delta, Omicron, and other emergent SARS-CoV-2 variants. bioRxiv. 2022;2022:479840. doi: 10.1128/aac.00222-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anesi G.L., Kerlin M.P. The impact of resource limitations on care delivery and outcomes: routine variation, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and persistent shortage. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27(5):513–519. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anesi G.L., Chowdhury M., Small D.S., et al. Association of a novel index of hospital capacity strain with admission to intensive care units. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(11):1440–1447. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-228OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anesi G.L., Liu V.X., Gabler N.B., et al. Associations of intensive care unit capacity strain with disposition and outcomes of patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(11):1328–1335. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-241OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weissman G.E., Gabler N.B., Brown S.E., et al. Intensive care unit capacity strain and adherence to prophylaxis guidelines. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hua M., Halpern S.D., Gabler N.B., et al. Effect of ICU strain on timing of limitations in life-sustaining therapy and on death. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(6):987–994. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gabler N.B., Ratcliffe S.J., Wagner J., et al. Mortality among patients admitted to strained intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):800–806. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0622OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Auld S.C., Caridi-Scheible M., Robichaux C., et al. Declines in mortality over time for critically ill adults with COVID-19. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1382. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Armstrong R., Kane A., Cook T. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1340–1349. doi: 10.1111/anae.15201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Asch D.A., Sheils N.E., Islam M.N., et al. Variation in US hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):471–478. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.White P.L., Dhillon R., Cordey A., et al. A National Strategy to Diagnose Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Invasive Fungal Disease in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1634–e1644. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Permpalung N., Chiang T.P., Massie A.B., et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(1):83–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koehler P., Bassetti M., Chakrabarti A., et al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):e149–e162. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30847-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A) Case Definition Information for Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-a/hcp.html Available at: Accessed May 31, 2022.

- 91.Patel P., DeCuir J., Abrams J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2126456. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Henderson L.A., Canna S.W., Friedman K.G., et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(4):e1–e20. doi: 10.1002/art.42062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]