Abstract

Introduction

Information regarding the clinical manifestations and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children under the Omicron variant predominant period is still limited.

Methods

A nationwide retrospective cohort study was conducted. Pediatric COVID-19 patients (<18 years of age) hospitalized between August 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022 were enrolled. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics between the Delta variant predominant period (August 1 to December 31, 2021) and the Omicron variant predominant period (January 1 to March 31, 2022) were compared.

Results

During the study period, 458 cases in the Delta predominant period and 389 cases in the Omicron predominant period were identified. Median age was younger (6.0 vs. 8.0 years, P = 0.004) and underlying diseases were more common (n = 65, 16.7% vs. n = 53, 11.6%) in the Omicron predominant period than those in the Delta variant predominant era. For clinical manifestations, fever ≥38.0 °C at 2 to <13 years old, sore throat at ≥ 13 years, and seizures at 2 to <13 years old were more commonly observed, and dysgeusia and olfactory dysfunction at ≥ 6 years old were less commonly observed in the Omicron variant predominant period. The number of patients requiring noninvasive oxygen support was higher in the Omicron predominant period than that in the Delta predominant period; however, intensive care unit admission rates were similar and no patients died in both periods.

Conclusions

In the Omicron variant predominant period, more pediatric COVID-19 patients experienced fever and seizures, although the overall outcomes were still favorable.

Keywords: Omicron variant, Delta variant, SARS-CoV-2, Seizures, Children

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2); since the first case reported in December 2019, it has spread rapidly and has caused 500 million cases and 6 million deaths worldwide to date [1]. At the beginning of the epidemic, the patients were mainly older adults; however, it gradually shifted to children and younger adults coinciding with distribution of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the mature adult population. As of May 2022, the largest number of newly diagnosed cases in Japan were among those in their teens or younger [2].

SARS-CoV-2 can mutate during its replication, and many variant strains have emerged so far [3]. It is known that the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 vary depending on the predominant variant strain [4]. For example, the Delta variant was reported to be more infectious and more likely to cause severe disease than previous strains did [5,6]. Our group also previously reported that the number of pediatric COVID-19 inpatients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission was higher during the Delta variant predominant period than before [7].

Since January 2022, the Omicron variant has become predominant worldwide, including in Japan [3,8]. It has been reported that the Omicron variant is more contagious than conventional strains, but the risk of severe diseases may be lower in the adult population [1]. However, information regarding the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 during the Omicron variant predominant period in children is limited.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the differences in clinical characteristics of pediatric COVID-19 hospitalized cases during the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This is a retrospective cohort study using data from the COVID-19 registry Japan (COVIREGI-JP) conducted under the Repository of Data and Biospecimen of Infectious Disease (REBIND) project. The details about COVIREGI-JP were described previously [9]. In brief, COVIREGI-JP is a prospective, nationwide COVID-19 registry in Japan. Laboratory confirmed, hospitalized COVID-19 patients in all age groups are registered from participating institutions all over Japan. As of April 2022, 708 facilities have participated in this registry and 64,366 cases have been enrolled [10].

Pediatric patients (<18 years of age) hospitalized between August 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022 were identified from the registry. The study period was divided into two groups, namely, the Delta variant predominant period (August 1 to December 31, 2021) and the Omicron variant predominant period (January 1 to March 31, 2022). Epidemiological and clinical information including age, sex, underlying diseases, history of prior exposure to COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status, signs and symptoms, severity, complications, and outcomes were extracted from the registry database. These values were compared between the Delta and the Omicron variant predominant periods.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous values were expressed as number (%) and median (interquartile range [IQR]), respectively. To compare the two groups (Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods), the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables were used. P values < 0.05 (two-sided test) were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by R statistical software (version 4.1.3).

2.3. Ethical consideration

This study was conducted under approval from the ethics review committees at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM-G-003494-0) and the National Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD-2022-025).

3. Results

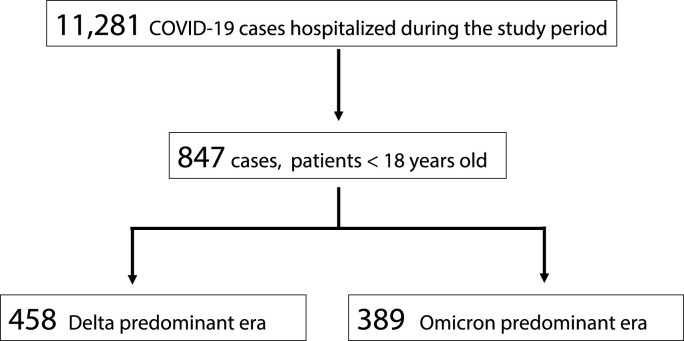

During the study period, 11,281 hospitalized COVID-19 cases were enrolled in the registry. Among them, 847 pediatric cases aged <18 years were identified; 458 cases were during the Delta variant predominant period and 389 cases were during the Omicron variant predominant period. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Median (IQR) age was 7.0 (2.0–13.0) years and male sex was 456 (53.8%). One hundred eighteen (13.9%) patients had underlying diseases; the most common one was bronchial asthma (n = 52, 6.1%), followed by congenital heart anomaly (n = 13, 1.5%) and obesity (n = 12, 1.4%). Only 50 (5.9%) patients completed two doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.(see fig 1)

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variables | Number of cases | Subcategory | Total | Delta variant predominant period | Omicron variant predominant period | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | 847 | 847 | 458 | 389 | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 847 | 7.0 (2.0–13.0) | 8.0 (2.0–13.0) | 6.0 (1.0–12.0) | 0.004 | |

| Male sex, number (%) | 847 | 456 (53.8) | 245 (53.5) | 211 (54.2) | 0.836 | |

| Body weight, median (IQR) | 815 | 23.0 (11.8–45.1) | 25.9 (13.0–48.0) | 20.2 (10.1–40.0) | <0.001 | |

| Underlying disease, number (%) | 847 | Any underlying disease | 118 (13.9) | 53 (11.6) | 65 (16.7) | 0.036 |

| Bronchial asthma | 52 (6.1) | 24 (5.2) | 28 (7.2) | 0.253 | ||

| Congenital heart anomaly | 13 (1.5) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (2.1) | 0.276 | ||

| Obesity | 12 (1.4) | 10 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.045 | ||

| Congenital anomaly or chromosomal abnormality | 12 (1.4) | 4 (0.9) | 8 (2.1) | 0.159 | ||

| Diabetes without complications | 6 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0.693 | ||

| Hypertension | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 | ||

| Others | 33 (3.9) | 7 (1.5) | 26 (6.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Immunosuppressive condition, number (%) | 847 | 23 (2.7) | 3 (0.7) | 20 (5.1) | <0.001 | |

| Exposure within 14 days prior to admission | 844 | Travel abroad | 26 (3.1) | 17 (3.7) | 9 (2.3) | 0.336 |

| 842 | Close contact with COVID-19 cases | 633 (75.2) | 367 (80.5) | 266 (68.9) | <0.001 | |

| 847 | Family | 481 (56.8) | 300 (65.5) | 181 (46.5) | <0.001 | |

| 847 | Educational facility | 113 (13.3) | 46 (10.0) | 67 (17.2) | 0.002 | |

| 847 | Nonfamily roommates | 7 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.3) | 0.257 | |

| 847 | Workplace | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0 | |

| 847 | Healthcare facility | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | 1.0 | |

| 847 | Others | 36 (4.3) | 18 (3.9) | 18 (4.6) | 0.614 | |

| Onset to hospitalization (days) | 763 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | <0.001 | |

| Past history of COVID-19 | 845 | 8 (0.9) | 8 (1.8)a | 0 (0.0) | 0.009 | |

| Number of patients with two doses of SARS-CoV-2vaccine | 847 | 50 (5.9) | 1 (0.2) | 49 (12.6) | <0.001 |

SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory coronavirus type 2; VOC, variant of concern; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Among eight patients with a known history of COVID-19, five patients were diagnosed within the same Delta variant predominant period.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram

Comparing the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods, respectively, median age was younger (8.0 vs. 6.0 years, P = 0.004), underlying diseases were more common (n = 53, 11.6% vs. n = 65, 16.7%) and COVID-19 exposure at an educational facility prior to admission was more common (n = 46, 10.0% vs. n = 67, 17.2%) in the Omicron variant predominant period. The frequency of several clinical characteristics in each age group was different between those periods, i.e., fever ≥38.0 °C at 2 to <13 years old, sore throat at ≥ 13 years old, cough in 3–24 months old, seizures at 2 to <13 years old, and vomiting at 6–13 years old were more commonly observed, and dysgeusia and olfactory dysfunction at ≥ 6 years old were less commonly observed in the Omicron variant predominant period than those in the Delta variant predominant period. Among the 33 patients with seizures, 22 (66.7%) were febrile with a body temperature ≥38.0 °C. Asymptomatic patients at age <3 months and 6 to <13 years were more common in the Delta predominant period (Table 2 ). The differences in the severity, complications, and outcomes between those two periods are summarized in Table 3 . We found 9/847 (1.8%) patients developed pneumonia in entire period: 2/458 (0.4%) during the Delta variant period and: 7/389 (1.8%) Omicron variant period, p = 0.088). The number of patients requiring noninvasive oxygen support was higher in the Omicron predominant period than that in the Delta predominant period; however, ICU admission rates and frequency of complications, including meningitis/encephalitis, seizures as a complication, and myocarditis/endocarditis/cardiomyopathy, were similar and no patients died in both periods. Among the 13 patients who required ICU admission, 5 (38.5%) had underlying diseases, including bronchial asthma (n = 2), liver dysfunction (n = 1), cerebrovascular disease (n = 1), and solid tumor (n = 1); none received two doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Death, need for mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), ICU admission, or the requirement of noninvasive oxygen support were set as the composite outcome for moderate to severe COVID-19. For patients with this composite outcome, none received two doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination [0/43 (0%) with composite outcome vs. 50/747 (6.7%) without composite outcome, p = 0.103. Vaccine history was not obtained in 57 patients].

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics on admission in the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods by age group.

| Patient characteristics | Total | <3 months | 3 to <24 months | 2 to <6 years | 6 to <13 years | ≥13 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 458 | 20 | 74 | 88 | 142 | 134 |

| Omicron predominant period | 389 | 27 | 86 | 67 | 116 | 93 |

| Asymptomatic cases | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 61 (13.3) | 3 (15.0) | 14 (18.9) | 17 (19.3) | 23 (16.2) | 4 (3.0) |

| Omicron predominant period | 18 (4.6) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (5.8) | 9 (13.4) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.2) |

| Body temperature (°C) | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 37.2 (36.7–37.9) | 37.5 (37.1–38.0) | 37.2 (36.7–37.7) | 37.1 (36.7–37.7) | 37.0 (36.7–37.6) | 37.2 (36.8–38.0) |

| Omicron predominant period | 37.5 (36.9–38.5) | 37.6 (37.2–38.3) | 37.6 (37.0–38.9) | 37.8 (37.0–38.5) | 37.7 (36.9–38.5) | 37.2 (36.8–38.1) |

| Fever ≥ 38.0°C | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 109 (23.8) | 7 (35.0) | 22 (29.7) | 18 (20.5) | 27 (19.0) | 35 (26.1) |

| Omicron predominant period | 145 (37.3) | 9 (33.3) | 38 (44.2) | 29 (43.3) | 43 (37.1) | 26 (28.0) |

| SpO2 < 96% under room air | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 18 (4.1) | 1 (5.6) | 4 (5.6) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (2.1) | 6 (4.7) |

| Omicron predominant period | 16 (4.3) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (4.9) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (4.5) | 4 (4.5) |

| Runny nose | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 108 (23.6) | 8 (40.0) | 29 (39.2) | 17 (19.3) | 26 (18.3) | 28 (20.9) |

| Omicron predominant period | 91 (23.4) | 10 (37.0) | 33 (38.4) | 17 (25.4) | 14 (12.1) | 17 (18.3) |

| Sore throat | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 85 (18.6) | N/A | 3 (4.1) | 5 (5.7) | 26 (18.3) | 51 (38.1) |

| Omicron predominant period | 89 (22.9) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.5) | 30 (25.9) | 56 (60.2) |

| Cough | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 215 (46.9) | 6 (30.0) | 26 (35.1) | 40 (45.5) | 60 (42.3) | 83 (61.9) |

| Omicron predominant period | 191 (49.1) | 10 (37.0) | 50 (58.1) | 30 (44.8) | 54 (46.6) | 47 (50.5) |

| Wheezing | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 6 (1.3) | N/A | 2 (2.7) | 4 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Omicron predominant period | 11 (2.8) | N/A | 6 (7.0) | 4 (6.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chest pain | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 8 (1.7) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (4.5) |

| Omicron predominant period | 2 (0.5) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 81 (17.7) | N/A | 6 (8.1) | 2 (2.3) | 17 (12.0) | 56 (41.8) |

| Omicron predominant period | 49 (12.6) | N/A | 2 (2.3) | 7 (10.4) | 20 (17.2) | 20 (21.5) |

| Headache | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 72 (15.7) | N/A | 1 (1.4) | 3 (3.4) | 15 (10.6) | 53 (39.6) |

| Omicron predominant period | 46 (11.8) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.5) | 16 (13.8) | 25 (26.9) |

| Alteration of consciousness | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Omicron predominant period | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 5 (4.3) | 2 (2.2) |

| Seizures | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 9 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (0.7) |

| Omicron predominant period | 24 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.0) | 9 (13.4) | 9 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 38 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (12.2) | 7 (8.0) | 10 (7.0) | 12 (9.2) |

| Omicron predominant period | 22 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (5.8) | 2 (3.0) | 11 (9.5) | 3 (3.2) |

| Vomiting | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 39 (8.5) | 2 (10.0) | 5 (6.8) | 7 (8.0) | 9 (6.3) | 16 (11.9) |

| Omicron predominant period | 65 (16.7) | 2 (7.4) | 10 (11.6) | 13 (19.4) | 32 (27.6) | 8 (8.6) |

| Dysgeusia | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 28 (6.1) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (6.3) | 18 (13.4) |

| Omicron predominant period | 3 (0.8) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.2) |

| Olfactory dysfunction | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 26 (5.7) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (5.6) | 18 (13.4) |

| Omicron predominant period | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Arthralgia/myalgia | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 25 (5.5) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 23 (17.2) |

| Omicron predominant period | 12 (3.1) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (3.4) | 7 (7.5) |

| Rash | ||||||

| Delta predominant period | 9 (2.0) | 1 (5.0) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Omicron predominant period | 9 (2.3) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (4.5) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.1) |

SpO2, saturated oxygen in arterial blood.

Subjective symptoms in children under 3 months were not applicable (N/A) because they had difficulty describing them.

Symptom frequencies by age between the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods were compared using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables; items with P < 0.05 are in bold.

Table 3.

Comparison of severity, complications, and outcomes between the Delta variant and Omicron variant predominant periods.

| Variables | Total | Delta variant predominant period | Omicron variant predominant period | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | 847 | 458 | 389 | NA |

| Noninvasive oxygen support (nasal cannula, face mask, reservoir mask, high-flow oxygen device) | 45 (5.3) | 17 (3.7) | 28 (7.2) | 0.031 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation/ECMO | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 0.211 |

| ICU admission | 13 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | 1.0 |

| Pneumonia | 9 (1.8) | 2 (0.4) | 7 (1.8) | 0.088 |

| Meningitis/encephalitis | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.782 |

| Seizures as complication | 8 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (1.5) | 0.153 |

| Myocarditis/endocarditis/cardiomyopathy | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1.0 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | <0.001 |

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; VOC, variant of concern.

4. Discussion

This study revealed that several clinical symptoms, including fever, seizures, and vomiting, were more common in the Omicron variant predominant period than in the Delta variant predominant period; however, the ICU admission rates were similar in those two periods in COVID-19 hospitalized pediatric patients in Japan.

Changes in clinical manifestations during the Omicron variant predominant period have been reported mainly from adult populations. A retrospective observational multicenter study conducted in 13 emergency departments in France revealed that the patients with the Omicron variant had lower rates of cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, and anosmia compared with patients with the Delta variant [11]. A prospective longitudinal observational study performed in the UK, including 4990 patients in the “Delta variant prevalent at > 70% period” and 4990 patients in the “Omicron variant prevalent at > 70% period”, reported that sore throat and hoarse voice were more common, and fever, runny nose, and altered smell were less common in the Omicron variant period [12]. In these studies, the frequency of seizures was not assessed.

Information regarding clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in children with the Omicron variant is still limited. A multicenter observational study conducted in South Africa during the first wave of the Omicron variant revealed that fever, vomiting, and seizures were observed in 58/125 (46%), 30/125 (24%), and 25/125 (20%), respectively, of hospitalized children ≤13 years old with COVID-19; however, this study did not compare these frequencies to any other variant [13]. A case series at a hospital in Sweden reported four cases of COVID-19 in children (three were laboratory confirmed, one was a clinical diagnosis) with convulsions [14]. Consistent with these reports, our study revealed that more pediatric COVID-19 patients experienced seizures in the Omicron variant predominant period. Interestingly, in both previous reports and our report, there were cases with seizures at age 5 years and older that were outside of the common age range for febrile seizures in children. This may suggest that the omicron variant can not only cause febrile seizures in infants, but can also cause seizures in older children. In our cohort, only one (0.3%) patient had meningitis/encephalitis as a complication of COVID-19; however, neurotrophicity of SARS-CoV-2 in children should be investigated in the future.

Furthermore, the interpretation of the frequency of COVID-19 symptoms in children is more complex than in adults because of the difficulty of interpreting subjective symptom complaints at younger ages in children and differences in the frequency of symptoms at different ages [15]. Hence, we compared the frequency of symptoms of the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods by age group and excluded subjective symptoms in the young age groups that had difficulty in explaining their symptoms. In addition, it should be noted that younger age groups may underestimate subjective symptoms.

The severity and outcomes of COVID-19 with the Omicron variant are important issues. Many COVID-19 related studies in the adult population reported that COVID-19 during the Omicron variant predominant period was less severe than during other periods, including the Delta variant predominant period [11,12,16]. A similar trend was reported for COVID-19 in children. Wang et al. performed a propensity score matching cohort study in children younger than 5 years in the United States that revealed that risks for hospitalizations and ICU admissions were lower in the patients <5 years old in the Omicron variant predominant period than those in the Delta predominant period. Another propensity matched cohort study conducted in Qatar reported that the patients with the Omicron variant infection had less severe disease [17]. In our study, more patients required noninvasive oxygen support in the Omicron variant predominant period than in the Delta variant predominant period; however, the ICU admission rates in those two periods were similar and no patients died. The reason that more patients in the Omicron variant predominant period required noninvasive oxygen support is still unclear; although not statistically significant, there were more patients with pneumonia in the Omicron variant period in our cohort, which may explain the difference in the need for oxygen support in part. A further large-scale study is needed to confirm whether the Omicron variant plays a role in the susceptibility to pneumonia, requiring oxygenation in children.

This study has a several limitations. First, our data did not include information regarding the specific variant strain detected from each patient, and therefore, we could not assess the direct effect of variant strain on its clinical characteristics. However, data from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases revealed that more than 95% of the variant strains detected in Japan during the Delta and Omicron variant predominant periods that we defined were the Delta and Omicron variants, respectively [8]. This suggests that the impact of not being able to detect variant strains directly could be considered minimal. Second, the number of SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated children during the study period was small and its impact on their clinical manifestations has not been fully evaluated. Although the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is known to be useful for preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 disease [18,19], its impact on clinical manifestations and frequency of complications is not clear. This issue needs to be addressed in future studies using data from the phase when the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is more widely distributed in children in Japan. Third, there may have been differences in the indications for hospitalization at the two time periods. In fact, there were more asymptomatic patients hospitalized during the Delta predominant period in some age groups, and it cannot be ruled out that this may have affected the differences in the frequencies of symptoms between the two periods. Fourth, as the current analysis was based on acute-phase data, the impact of long-COVID could not be examined. It has been reported that long-COVID can be a problem even in children [20,21], and future studies on long-COVID in Japanese children are warranted. Finally, COVIREGI-JP is a voluntary-based registry and does not include all hospitalized COVID-19 patients. In fact, between August 4, 2021, and March 29, 2022, almost the same period as our study periods, 1,397,236 COVD-19 patients aged <20 years were newly diagnosed in Japan, including non-hospitalized patients. It means approximately 0.06% of cases were included in our registry. Therefore, it is fair to say our data only partially represent the epidemiology of inpatient pediatric COVID-19 in Japan. To provide more data with better accuracy, establishing a national registry that enrolls all hospitalized patients should be warranted.

In conclusion, fever and seizures were more common in the Omicron variant predominant period; however, overall severity was still low and outcomes were favorable. The clinical characteristics of COVID-19 can change depending on the predominant variant strain at the time, and therefore, it is necessary to keep the data updated.

Authorship statement

KS contributed to designing and conceptualizing the study and drafted the manuscript. TA and ST contributed to data collection, statistical analysis, and revising of the manuscript. NM, YA, SS, and NI contributed to data collection, and revising of the manuscript. TF contributed to the revised the manuscript. NO contributed to the revised the manuscript, and supervised the study. All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

K. Shoji received payment for lectures from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Astellas, AbbVie GK, Biomelieux Japan, Nippon Becton Dickinson Company, Ltd., and Gilead. S. Tsuzuki received payment for supervising medical articles from Gilead Sciences, Inc.

The other authors have indicated they have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare “Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases and Immunization” program (grant no. 19HA1003) and the REBIND Project.

References

- 1.World Health Organization COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---8-june-2022 Available at:

- 2.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Visualizing the data: information on COVID-19 infections. https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/en/ Available at:

- 3.World Health Organization Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants Available at:

- 4.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): variants of SARS-COV-2. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29-variants-of-sars-cov-2?gclid=CjwKCAjwve2TBhByEiwAaktM1Bs4oJ-dA7zjT9ARwvrNYWND68h83WB8S8zU8wEHwO7xN0iuWF0L-hoCJcQQAvD_BwE Available at:

- 5.Fisman D.N., Tuite A.R. Evaluation of the relative virulence of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants: a retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2021;193:E1619–e1625. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health England SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England Technical briefing 14. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/991343/Variants_of_Concern_VOC_Technical_Briefing_14.pdf Available at:

- 7.Shoji K., Akiyama T., Tsuzuki S., et al. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in children before and after the emergence of Delta variant of concern in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Infectious Diseases 20220601_genome_weekly_lineageJAPAN. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/kokunainohasseijoukyou.html Available at:

- 9.Matsunaga N., Hayakawa K., Terada M., et al. Clinical epidemiology of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Japan: report of the COVID-19 REGISTRY Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e3677–e3689. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Global Health and Medicine COVID-19 registry Japan. https://covid-registry.ncgm.go.jp/ Available at:

- 11.Bouzid D., Visseaux B., Kassasseya C., et al. Comparison of patients infected with delta versus omicron COVID-19 variants presenting to Paris emergency departments : a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.7326/M22-0308. M22-0308[Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menni C., Valdes A.M., Polidori L., et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet. 2022;399:1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00327-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloete J., Kruger A., Masha M., et al. Paediatric hospitalisations due to COVID-19 during the first SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant wave in South Africa: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:294–302. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00027-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludvigsson J.F. Convulsions in children with COVID-19 during the Omicron wave. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111:1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/apa.16276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoji K., Akiyama T., Tsuzuki S., et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 in children: report from the COVID-19 registry in Japan. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10:1097–1100. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdullah F., Myers J., Basu D., et al. Decreased severity of disease during the first global omicron variant covid-19 outbreak in a large hospital in tshwane, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butt A.A., Dargham S.R., Loka S., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 disease severity in children infected with the omicron variant. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Apr 11 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac275. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frenck R.W., Jr., Klein N.P., Kitchin N., et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the BNT162b2 covid-19 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter E.B., Talaat K.R., Sabharwal C., et al. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 Years of age. N Engl J Med. 2021;386:35–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borch L., Holm M., Knudsen M., Ellermann-Eriksen S., Hagstroem S. Long COVID symptoms and duration in SARS-CoV-2 positive children - a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1597–1607. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFarland S., Citrenbaum S., Sherwood O., van der Togt V., Rossman J.S. Long COVID in children. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:e1. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00338-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]