ABSTRACT

Avian or human influenza A viruses bind preferentially to avian- or human-type sialic acid receptors, respectively, indicating that receptor tropism is an important factor for determining the viral host range. However, there are currently no reliable methods for analyzing receptor tropism biologically under physiological conditions. In this study, we established a novel system using MDCK cells with avian- or human-type sialic acid receptors and with both sialic acid receptors knocked out (KO). When we examined the replication of human and avian influenza viruses in these KO cells, we observed unique viral receptor tropism that could not be detected using a conventional solid-phase sialylglycan binding assay, which directly assesses physical binding between the virus and sialic acids. Furthermore, we serially passaged an engineered avian-derived H4N5 influenza virus, whose PB2 gene was deleted, in avian-type receptor KO cells stably expressing PB2 to select a mutant with enhanced replication in KO cells; however, its binding to human-type sialylglycan was undetectable using the solid-phase binding assay. These data indicate that a panel of sialic acid receptor KO cells could be a useful tool for determining the biological receptor tropism of influenza A viruses. Moreover, the PB2KO virus experimental system could help to safely and efficiently identify the mutations required for avian influenza viruses to adapt to human cells that could trigger a new influenza pandemic.

IMPORTANCE The acquisition of mutations that allow avian influenza A virus hemagglutinins to recognize human-type receptors is mandatory for the transmission of avian viruses to humans, which could lead to a pandemic. In this study, we established a novel system using a set of genetically engineered MDCK cells with knocked out sialic acid receptors to biologically evaluate the receptor tropism for influenza A viruses. Using this system, we observed unique receptor tropism in several virus strains that was undetectable using conventional solid-phase binding assays that measure physical binding between the virus and artificially synthesized sialylglycans. This study contributes to elucidation of the relationship between the physical binding of virus and receptor and viral infectivity. Furthermore, the system using sialic acid knockout cells could provide a useful tool to explore the sialic acid-independent entry mechanism. In addition, our system could be safely used to identify mutations that could acquire human-type receptor tropism.

KEYWORDS: influenza A virus, receptor tropism, sialylglycan, mutant, reverse genetics

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A virus initiates infection via viral hemagglutinin (HA) by binding to avian- or human-type receptors which consist of terminal sialic acids linked to galactose with α2,3 or α2,6 linkages, respectively (1, 2). Human influenza viruses preferentially bind to human-type receptors, whereas avian influenza viruses bind to avian-type receptors. The human upper respiratory tract predominantly expresses human-type receptors, leading to the efficient infection and replication of human influenza viruses but not avian influenza viruses (3, 4). The acquisition of mutations on avian virus HAs to recognize human-type receptors is mandatory for the transmission of avian influenza viruses or reassortants with avian virus HAs to humans, which could lead to a pandemic. Therefore, it is important to detect such mutations in animal influenza viruses as genetic markers for surveillance and risk assessment for pandemic preparedness.

The binding affinity of HAs for sialylglycans was measured using enzyme-treated resialylated erythrocytes in earlier years (5) and is currently measured using synthesized short sialylglycans resembling human- or avian-type receptors (6, 7) or glycan arrays such as the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) array. These arrays contain panels of glycans with various lengths and complex branching and enable evaluation of the binding affinity of viruses to various kinds of glycans (8, 9). In addition, to address the problem that glycans used in these methods do not necessarily mimic those on in vivo respiratory cells, a microarray method using isolated glycans from human or swine lungs has been developed to identify natural receptors for influenza viruses (10, 11). Although these methods are useful for measuring the physical binding affinity between HAs and sialylglycans, they cannot assess the biological correlation between sialylglycan binding and viral infection because binding affinity does not necessarily reflect different sialic acid forms, which are important for viral infectivity (12, 13). For instance, N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac)-type glycans act as functional receptors for influenza viruses, while N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc)-type glycans inhibit infection of most influenza viruses as pseudoreceptors (14).

It is well known that Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells efficiently support the replication of most influenza viruses. Therefore, MDCK cells lacking sialic acids could be useful for assessing the preference of biological receptors for influenza virus infection. Recently, Takada et al. (15) developed “humanized” MDCK cells expressing high levels of α2,6-linked sialylglycans and low levels of α2,3-linked sialylglycans that can support efficient growth of the recent seasonal H3N2 viruses. However, the development of MDCK cells lacking α2,6-linked sialylglycans and entire terminal sialic acids of cellular glycans have not been reported yet. Previous reports have indicated that SLC35A1 transports cytidine-5′-monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic (CMP-sialic) acid, a sialyltransferase substrate, from the cytoplasm to the Golgi apparatus (16) and that β-galactosidase α2,3 sialyltransferases (ST3Gals) or α2,6 sialyltransferases (ST6Gals) catalyze the transfer of CMP-sialic acids with α2,3 or α2,6 linkages to terminal galactose in the Golgi apparatus, respectively (17, 18). Mammalian genomes encode six ST3Gal subfamilies (ST3Gal1 to -6) and two ST6Gal subfamilies (ST6Gal1 and ST6Gal2). Therefore, it is predicted that sialylglycan knockout (KO) cells could be generated by knocking out the genes involved in sialylglycan synthesis.

In this study, we generated a series of cells lacking human- and/or avian-type receptors by knocking out six ST3Gals, two ST6Gals, or the SLC35A1 gene in MDCK cells. We then used these KO cells to biologically evaluate the receptor tropism of a panel of influenza viruses. By serially passaging a replication-incompetent avian virus lacking the PB2 gene, to limit biosafety concerns, in the avian-type receptor KO cells, we adapted the virus and selected mutants with enhanced replication in the KO cells. Through these experiments, we examined the receptor specificity of influenza viruses that have been overlooked in previous glycan-binding assays.

RESULTS

Establishment of sialic acid KO cells.

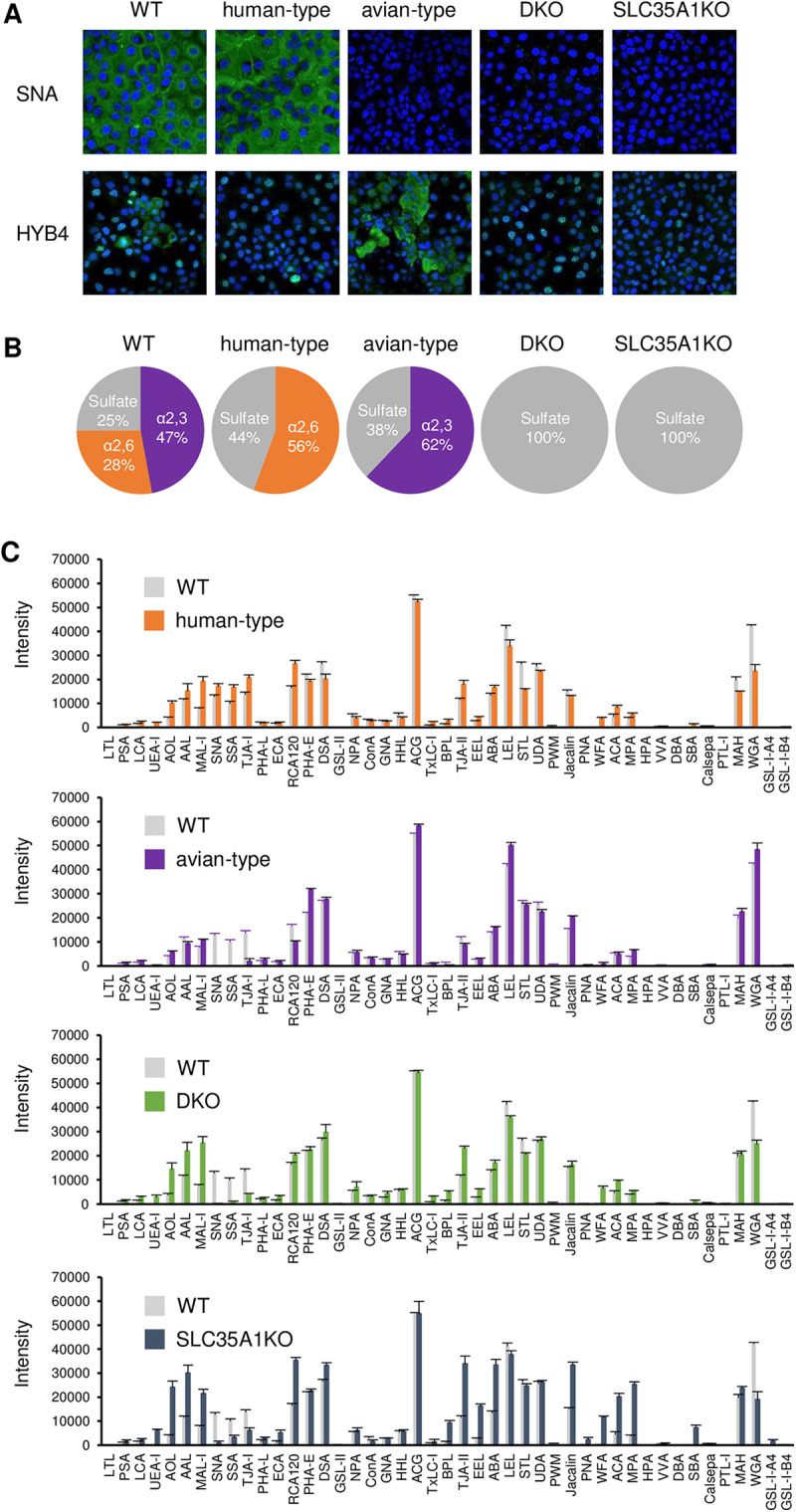

To establish an assay system to biologically evaluate the receptor tropism of influenza viruses, we generated Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells lacking human- and/or avian-type sialylglycans. First, we knocked out six ST3Gal (ST3Gal1 to ST3Gal6) and/or two ST6Gal (ST6Gal1 and ST6Gal2) genes in the cells using a CRISPR/Cas9 system with guide RNAs targeting these genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We also knocked out the sialic acid transporter SLC35A1 gene in these cells. After confirming indel sequences in the target genomic DNA regions, we confirmed the absence of avian- or human-type sialylglycans on the KO cells by staining with anti-Neu5Acα2,3Gal monoclonal antibody (HYB4) and Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) lectin recognizing Neu5Acα2,6Gal (Fig. 1A). Wild-type (WT) MDCK cells were stained with both HYB4 antibody and SNA lectin, whereas ST3Gal KO (human-type) cells were stained only with SNA lectin and ST6Gal KO (avian-type) cells were stained only with HYB4 antibody. Both ST3Gal and ST6Gal KO (DKO) cells and SLC35A1 KO (SLC35A1KO) cells were stained with neither SNA lectin nor HYB4 antibody. The morphologies of all KO cells were appreciably similar to those of the WT cells. Together, these data indicate that human- and/or avian-type receptor KO cells were successfully established.

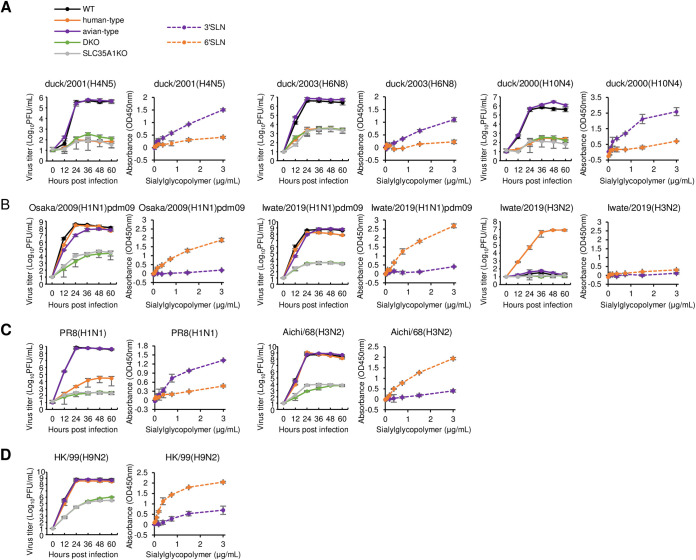

FIG 1.

Confirmation of the presence of avian- and human-type sialylglycans in KO cells. (A) Wild-type (WT) MDCK and KO cells were stained with SNA, a lectin that recognizes Neu5Acα2,6Gal, and HYB4, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes Neu5Acα2,3Gal. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. (B) Acidic sialylglycans among the N-type glycans were detected using mass spectrometric analysis with the SALSA method. The percentages of avian-type (α2,3), human-type (α2,6), and sulfated glycans are presented in pie charts in purple, orange, and gray, respectively. (C) The glycan profiles of WT, human-type, avian-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells were analyzed using lectin arrays. Cells were biotinylated and lysed, and the proteins in the lysate were added to slides printed with 45 types of lectin. The amounts of proteins binding to the lectins were measured using a GlycoStation Reader 1200. Data were mean normalized and are presented as the means of three replicates ± standard deviations.

Mass spectrometry and lectin array analyses of KO cells.

Influenza viruses predominantly use N-linked sialylglycans, but not O-linked sialylglycans, during infection (19). To investigate the distribution of N-linked glycans in KO cells, they were collected from the cell lysates and analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS) using the sialic acid linkage-specific alkylamidation (SALSA) method. This is based on the principal that α2,6- and α2,3-linked sialic acids are specifically amidated with different length alkyl chains that can be distinguished using mass spectrometry (20, 21). High-mannose-type glycans were abundant in WT cells and all tested KO cells, while neutral glycans were abundant and acidic glycans were less abundant in DKO and SLC35A1KO cells than in WT, human-type, and avian-type cells (Fig. S1). We further analyzed acidic glycans, which include sialylglycans (Fig. 1B), and found that while WT cells had both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialylglycans, α2,3-linked glycans were more dominant. Human- and avian-type cells lacked α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialylglycans, respectively, whereas DKO and SLC35A1KO cells lacked sialylglycans. The levels of terminal sulfated galactose increased in all KO cells, while all acidic glycans consisted of terminal sulfated galactose in DKO and SLC35A1KO cells (Fig. 1B).

Next, we investigated the glycan profiles of KO cells using lectin microarray assays (22, 23). A panel of lectins were immobilized as arrays (Table S2) and incubated with fluorescently labeled cell lysates containing all N- and O-linked glycans. The interactions between the lectins and lysates were detected using a fluorescence imager. Signals for MAL-I lectin, which recognizes Siaα2,3Gal and sulfated galactose (24), were higher in human-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells than in WT cells (Fig. 1C). Since Siaα2,3Gal was completely absent in these cells, as indicated by mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 1B), these increased signals should be due to sulfated galactose, consistent with the mass spectrometry results (Fig. S2). The signals for the Siaα2,6Gal-recognizing lectins, SNA and Sambucus sieboldiana agglutinin (SSA), and the Siaα2,6Galβ1,4GlcNAc-recognizing lectin, TJA-I, were also higher in human-type cells than in WT cells, indicating an increase in the amount of α2,6-linked sialic acid due to ST3Gal gene knockout. Conversely, SNA, SSA, and TJA-I signals were substantially lower in avian-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells (Fig. 1C), further supporting the mass spectrometry results. These results, in combination with those of the mass spectrometry analysis, suggest that the KO cells lacked N-linked α2,3- and/or α2,6-linked sialic acid residues and likely corresponding O-linked glycans.

Viral growth in sialic acid KO cells and physical binding to avian- and human-type synthetic sialylglycans.

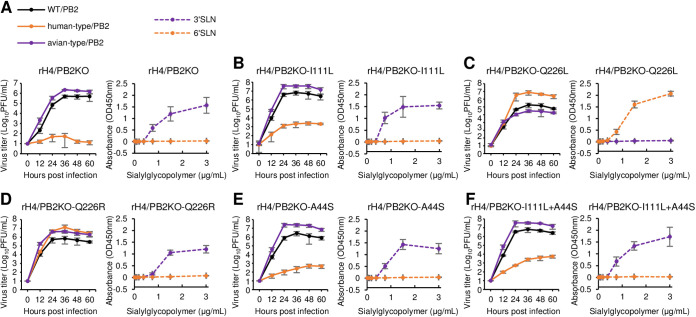

Each avian H4N5, H6N8, or H10N4 virus grew efficiently in both WT and avian-type cells but displayed limited growth in human-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells. These findings indicate that the avian viruses preferentially use avian-type receptors for their growth, consistent with their specific physical binding to avian-type sialylglycans in the solid-phase glycan binding assay (Fig. 2A). Osaka/H1N1pdm09 and its descendant Iwate/2019 grew efficiently not only in WT and human-type cells but also in avian-type cells, albeit at a slightly lower rate for Osaka/H1N1pdm09. However, the growth of both viruses was greatly reduced in both DKO and SLC35A1KO cells, indicating that these human H1N1 viruses use both human- and avian-type receptors for growth, despite their specific physical binding to human-type sialylglycan in the glycan binding assay (Fig. 2B). The recent seasonal Iwate/H3N2 virus grew well only in human-type cells, suggesting that it has strict human-type receptor selectivity for growth, although it displayed limited physical binding to sialylglycans in the glycan binding assay (Fig. 2B). The human-derived laboratory strain PR8(H1N1) grew efficiently in WT and avian-type cells but much less well in human-type cells (Fig. 2C), suggesting that successive passages of this human virus in chicken embryonated eggs might lead to preferential binding specificity to avian-type receptors, as supported by a strong physical binding to avian-type sialylglycans (Fig. 2C). Another human-derived laboratory strain, Aichi/68(H3N2), which is the ancestor of the seasonal H3N2 virus with unknown passage history, grew efficiently in both human- and avian-type cells, which did not correlate with the physical binding outcome of the glycan binding assay (Fig. 2C). The avian-origin HK/99(H9N2) virus, which was isolated from humans, is known to have a high affinity for human-type sialylglycan, as it possesses HA with L at position 226 (25, 26). This was consistent with the findings of our glycan binding assay and the observation that HK/99(H9N2) grew efficiently in both human- and avian-type cells as well as WT cells (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that the physical binding profiles between the viruses and sialic acids provided by the solid-phase glycan binding assay do not necessarily correlate with the biological usage of the receptors for viral growth.

FIG 2.

Comparison of virus growth in sialic acid KO cells and their physical binding to sialylglycopolymers. WT and sialic acid KO cells were infected with viruses at an MOI of 0.01. Supernatants were collected every 12 h, and viral titers were measured using plaque assays. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means of three independent experiments. Virus growth in WT, human-type, avian-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells is indicated by black, orange, purple, green, and gray solid lines, respectively. For the solid-phase binding assay, the virus (64 HAU) was absorbed to ELISA plate which was blocked and reacted with biotinylated avian-type (3′SLN) or human-type (6′SLN) sialylglycopolymers, followed by HRP-labeled biotin-streptavidin complex. TMB substrate reagent was added to develop color, and the reaction was stopped using 2% sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Data represent the means of three independent experiments ± standard deviations. The binding properties of the virus to avian- and human-type sialylglycopolymers are shown using purple and orange dashed lines, respectively. The growth and physical sialylglycan binding of avian-derived (A), human-derived (B), laboratory (C), and H9N2 (D) viruses are shown on the left and right, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to compare growth curves among samples. Statistical significance of the differences for AUC between each type and WT cells was analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test; P values are shown in Table S5 in the supplemental material.

Virus growth in sialic acid addback cells.

To confirm that the viral growth properties in KO cells (Fig. 2) were not due to off-target mutations from the CRISPR/Cas9 system, we generated four types of sialic acid addback cells in which the ST3Gal1 gene, ST6Gal1 gene, both genes, or the SLC35A1 gene was reintroduced into human-type, avian-type, DKO, or SLC35A1 KO cells, respectively. Sialic acid expression was restored in each addback cell type, as confirmed by staining with SNA lectin and HYB4 antibody (Fig. S3). We then tested viral growth in these cells, finding that growth was restored to levels comparable to those in the parental KO cells (Fig. S4). These results indicate a lack of off-target mutations and suggest that the difference in viral growth between the WT and KO cells was caused by KO of the corresponding sialylglycan.

Adaptation of an avian virus to human-type cells.

Although it is important to identify mutations that increase viral growth in human cells in order to monitor avian influenza viruses and assess their pandemic potential (27, 28), it is difficult to predict these mutations under laboratory conditions. Therefore, we used our established human-type cells to produce an evaluation system. We used reverse genetics to generate a replication-incompetent PB2 knockout virus (29) possessing HA and neuraminidase (NA) segments of the avian H4N5 virus, in addition to a modified PB2 segment containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene instead of the PB2 gene and the remaining five segments from WSN (namely, rH4/PB2KO virus). We also established WT and human- and avian-type cells stably expressing PB2 from WSN, which were termed WT/PB2, human-type/PB2, and avian-type/PB2 cells, respectively. We serially passaged the rH4/PB2KO virus in human-type/PB2 cell lines independently six times (lines A to F). Although the parental virus did not show clear cytopathic effects (CPEs) in the cells, they became clear by the sixth passage in all virus lines. Sequencing indicated that five out of the six passaged virus lines possessed Q to L or R mutations at amino acid position 226 of HA (HA1-Q226L/R), whereas line C possessed HA1-I111L and HA2-A44S without an HA1-226 mutation (Table 1). Line F had HA2-D112A as well as HA1-Q226R and NA-G341R, although HA2-A112 and NA-R341 were partially observed as a mixed population in the parental virus. HA1-226 and HA1-111 were located on the head domain of HA, and HA1-226 directly contacts the terminal sialic acid of the glycan receptor. HA2-44 and HA2-112 were located on the stalk region of HA (Fig. S5).

TABLE 1.

Mutations detected in human-type/PB2 cell-adapted PB2-deficient H4N5 virus

| Virus strain | Mutation in: |

|

|---|---|---|

| HA | NA | |

| H4N5-P6-A | HA1-Q226L | −a |

| H4N5-P6-B | HA1-Q226R | − |

| H4N5-P6-C | HA1-I111L | − |

| HA2-A44S | ||

| H4N5-P6-D | HA1-Q226R | − |

| H4N5-P6-E | HA1-Q226L | − |

| H4N5-P6-F | HA1-Q226R | G341R |

| HA2-D112A | ||

−, no mutation was detected.

Growth of H4N5 mutant viruses in sialic acid KO cells and binding to synthetic glycans.

To identify the mutation(s) in the adapted rH4/PB2KO virus responsible for efficient growth in human-type/PB2 cells, we generated recombinant rH4/PB2KO viruses with HA1-Q226L, HA1-Q226R, HA1-I111L, and/or HA2-A44S, which were referred to as rH4/PB2KO-Q226L, rH4/PB2KO-Q226R, rH4/PB2KO-I111L, rH4/PB2KO-A44S, and rH4/PB2KO-I111L+A44S, respectively. The rH4/PB2KO virus grew efficiently in both WT/PB2 and avian-type/PB2 cells, but not in human-type/PB2 cells, and bound specifically to avian-type glycan (Fig. 3A), as did the duck/2001(H4N5) virus (Fig. 2A). The rH4/PB2KO-I111L, rH4/PB2KO-A44S, and rH4/PB2KO-I111L+A44S viruses grew efficiently in WT/PB2 and avian-type/PB2 cells, like the rH4/PB2KO virus, but grew more than the parental virus in human-type/PB2 cells (Fig. 3B, E, and F). These mutant and parental viruses bound specifically to avian-type glycan in the glycan-binding assay, consistent with the viral growth observed in KO cells; however, the differences in growth between the mutant and parental strains could not be explained by the glycan-binding assay. rH4/PB2KO-Q226L grew more efficiently in human-type/PB2 than in WT/PB cells but grew at similar levels in avian-type/PB2 cells and in WT/PB cells (Fig. 3C), despite its specific binding to human-type glycans. In contrast, rH4/PB2KO-Q226R grew efficiently in all cells, despite its specific binding to avian-type glycans (Fig. 3D). These results confirm that the solid-phase glycan binding assay could not determine the biological usage of glycan receptors for viral growth and suggest that the KO cell-based virus adaptation assay could identify mutations that allow avian viruses to acquire efficient growth in human-type cells, unlike the glycan-binding assay.

FIG 3.

PB2-deficient H4N5 virus growth in PB2-expressing KO cells and binding to sialylglycopolymers. PB2-deficient viruses bearing WT or mutant H4 HA and N5 NA were inoculated into WT, human-type, and avian-type cells expressing PB2 at an MOI of 0.01. Supernatants were collected every 12 h, and the viral titer was measured using a plaque assay. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means of three independent experiments. Virus growth in WT, human-type, and avian-type cells are indicated by black, orange, and purple solid lines, respectively. For the solid-phase binding assay, various amounts of sialylglycopolymers were absorbed to the ELISA plate. After blocking, viruses (32 hemagglutination units [HAU]) were added to the plate and reacted with mouse antiserum against the H4N5 virus, followed by HRP-labeled secondary antibodies. TMB substrate reagent was added to develop color, and the reaction was stopped using 2% sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Data represent the means of three independent experiments ± standard deviations. The binding of the virus to avian- and human-type sialylglycopolymers is shown as purple and orange dashed lines, respectively. The growth and physical binding to sialylglycans of rH4/PB2KO (A), rH4/PB2KO-I111L (B), rH4/PB2KO-Q226L (C), rH4/PB2KO-Q226R (D), rH4/PB2KO-A44S (E), and rH4/PB2KO-I111L+A44S (F) viruses are shown on the left and right, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to compare growth curves among samples. Statistical significance of the differences for AUC between each type/PB2 and WT/PB2 cells was analyzed using ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test; P values are shown in Table S6.

Molecular dynamics simulation between HAs and human-type glycan.

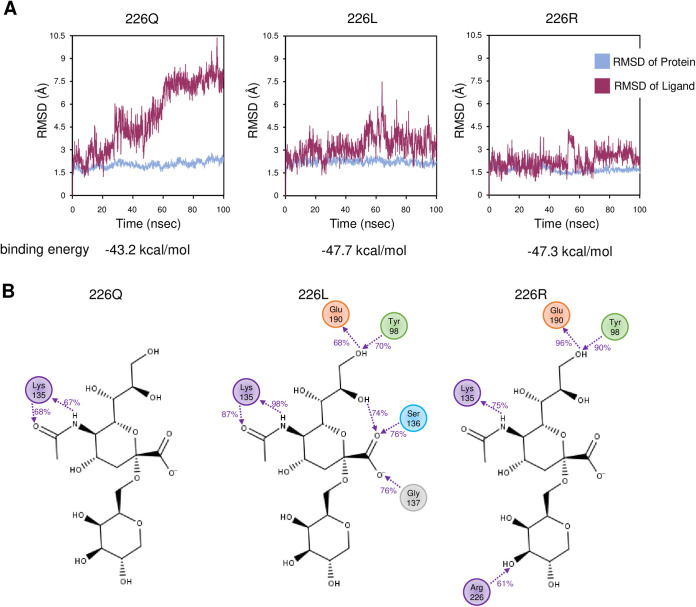

Finally, we analyzed the molecular basis of the HA1-Q226L/R mutations during binding to the human-type sialyl pentasaccharides analog (LSTc) using molecular dynamics simulation. To evaluate the stability of the HA-LSTc complex, the root mean square deviation (RMSD), which is an index of deviation from the initial structure, was calculated for each HA. The binding free energies between LSTc and H4 HAs were also calculated using the molecular mechanics with generalised Born and surface area (MM-GBSA) method. In HA1-226Q, the RMSD of the LSTc increased with time and dissociated from HA, suggesting weak LSTc binding, whereas in HA-HA1-226L or -226R, the RMSD did not change significantly over time, suggesting stable binding (Fig. 4A). The binding energies of the LSTc to HA1-226Q, -226L, and -226R were −43.2, −47.7, and −47.3 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating that 226L/R binds to human-type glycans more strongly than 226Q. The interaction between HA and the LSTc over 60% of the simulation time was found to be at only one site for HA1-226Q but at five and four sites for HA1-226L and HA1-226R, respectively (Fig. 4B). Together, these results suggest that the HA1-Q226L/R mutation enhances binding to human-type sialylglycans.

FIG 4.

Molecular dynamics simulation of human-type glycan and HA protein from H4 subtype. (A) Plots of RMSD against simulation time (100 ns). Blue and red lines indicate the RMSD of HA proteins and the glycan analog LSTc (Neu5Acα2,6Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,3Galβ1,4Glc), respectively. Simulation results from HA protein bearing Q, L, or R, at amino acid position 226 in HA1 are shown. (B) Detailed interactions between LSTc and amino acid residues. Interactions between galactose/sialic acid and the HA protein that were detected over 60% of the simulation time are indicated. Numbers between the interacting molecules represent the ratio (percent) of the time when the interaction was observed against the total simulation time.

DISCUSSION

The receptor tropism of influenza A viruses is one of the most important factors that determine their host range. To elucidate the mechanism via which avian viruses cross species barriers to infect humans and become pandemic viruses, it is essential to analyze their receptor specificity. Until now, receptor tropism analyses have mainly been performed by evaluating physical binding affinity to sialylglycans that resemble avian-type α2,3- or human-type α2,6-linked sialylglycans. However, these assay systems are often technical, requiring skills and expertise, and the resulting physical binding profiles do not necessarily represent the biological binding of the virus to receptors for growth. In this study, we developed a system that directly evaluates the biological receptor tropism of viruses by detecting their replication in artificially manipulated cells with avian- and/or human-type receptor KO. In addition, we developed a method to identify amino acid mutations in avian viruses that allow human-type receptor-mediated infection by adapting a replication-incompetent PB2-deficient virus with avian-derived HA to KO cells stably expressing PB2.

In this study, we found considerable inconsistency between the growth properties of some viruses in sialic acid KO cells and their sialylglycan-binding affinities as determined using conventional solid-phase binding assays. The growth properties of the avian H4, H6, and H10 viruses correlated well with the results of the binding assay, whereas H1N1pdm2009, Aichi/68(H3N2), and HK/99(H9N2) grew efficiently in avian-type cells despite their low binding affinities for avian-type sialylglycans. Recent human H3N2 viruses have been reported to have affinity for branched sialoglycans extended by LacNac repeats (13), rather than binding to α2,6-linked short glycans (30, 31). Therefore, it was difficult to detect the physical binding of recent seasonal H3N2 viruses, such as Iwate/43/2019, to human-type sialylglycans using the binding assays, although they grew efficiently in human-type cells with human-type receptor preference as reported previously (15). These results indicate that our sialic acid KO cell-based assay system can be used to assess the receptor specificity of viruses, even if their binding to avian- or human-type sialylglycans is undetectable using the binding assay. Thus, our assay system could be useful for biologically evaluating viral receptor preference. However, mass spectrometry analysis did not detect extended LacNac repeats in human-type cells. In addition, glycans with Gal-α1,3-Gal linkages, which were not expressed in human tissue, were detected in human-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells. These data suggest that the distribution and types of glycans may differ in part between the KO cells and the human respiratory cells. Due to these differences, mutations found in avian-derived viruses that were adapted to human-type cells were not necessarily a factor increasing infectivity to humans. Therefore, further modification of the KO cells to express sialylglycans with extended LacNac repeats and to knock out glycans not found in human tissues would help to identify mutations necessary to cause pandemics.

The acquisition of genetic mutations that increase binding affinity to human-type receptors is an essential factor for the adaptation of animal-derived viruses to humans. Passage experiments using primary human airway epithelial cells could be used to search for such mutations in avian viruses (32), since most cell lines, like MDCK cells, cannot be utilized as they possess both receptor types, despite supporting the efficient growth of most influenza A viruses (33). These types of passage experiments can also present biosafety concerns, as they generate mutant viruses with human-type receptor specificity. Therefore, we sought to create a replication-incompetent system using a PB2-deficient virus (29), wherein infectious viruses would not be produced in any intact cells. By combining this system with sialic acid KO cells, we identified HA1-Q226L and HA1-Q226R mutations in the avian H4 virus that are important for recognizing the human-type receptors. HA1-Q226L is a key mutation for avian H3N2 and H5N1 viruses to acquire binding to human-type receptors (34, 35), and it also contributes toward H5N1 and N7N9 viruses becoming transmissible between ferrets, which may indicate a potential for human-to-human transmissibility (27, 28, 36). HA1-226R has been detected in human and swine H1N1, avian H5N1, and egg-adapted H1N1pdm viruses (37) (see Table S4 in the supplemental material); however, the effects of this residue varied among viruses. In the human H1N1pdm virus, HA1-Q226R increased binding to avian-type sialylglycan and decreased binding to human-type sialylglycan (37), whereas in avian H5 virus, this mutation did not change binding affinity to human-type sialylglycan but decreased binding to avian-type sialylglycan (38). In this study, HA1-Q226R enhanced the preference of avian H4 virus for human-type sialylglycans, as evaluated using molecular dynamics simulations, but it did not change its binding affinity for human-type sialylglycan in the binding assay. Nonetheless, mutations at position 226 in HA1 may play a pivotal role in allowing avian viruses to change their biological binding to sialic acid receptors and thus potentially infect humans. Such human infection may also trigger further mutations for adaptation during the course of replication in humans.

A previous report showing that even MDCK cells desialylated by bacterial sialidase treatment were susceptible to influenza virus (39) has suggested that influenza virus can infect cells in a sialic acid-independent manner (40). Phosphorylated glycans (10), DC-SIGN/L-SIGN (41), or C-type lectin-mediated pathways (42) and dynamin-independent micropinocytosis (43) were reported to be related to cell entry of influenza viruses. In addition, it has been reported that major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II might be a receptor for bat influenza virus (44). In the present study, using DKO and SLC35A1KO cells, we have urged the presence of a sialic acid receptor-independent entry pathway. However, it has been unclear whether these molecules act as biologically functional receptors for viral infection. We believe that sialic acid KO cells such as those generated in this study could help to elucidate the molecular mechanism of early viral infection by functional assay, including alternative receptors.

Because viral HA and neuraminidase (NA) are glycosylated in host glycosylation pathway during their synthesis in cells, the glycosylation mode including terminal sialic acid in the viruses produced from the sialic acid KO cells should be different from its original state. Actually, the recombinant HAs that were expressed in N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase I-deficient cells or in insect cells lacked terminal sialic acid and such altered glycosylation patterns resulted in their different binding specificities from that of HA produced from wild-type human cells (45, 46). The HA glycosylation state also affected the viral pathogenicity (47) as well as immunogenicity (48–50). We can generate glycan-modified viruses lacking α2,3- and/or α2,6-linked terminal sialic acids by using our sialic acid KO cells. These viruses will be useful for elucidating the mechanisms regulated by glycosylation of viral surface glycoproteins in virus phenotypes such as cell attachment, pathogenicity, and immunogenicity.

In conclusion, we developed a novel method to evaluate the receptor preference of influenza viruses using viral replication as a biological indicator. In addition, we demonstrated that this method can be utilized to safely assess mutations for the adaptation of animal viruses to human cells that could lead to pandemic potential. This strategy could be used not only for basic analyses, such as elucidating the mechanism of viral host range determination, but also for the surveillance of viruses of animal origin that are capable of infection via human-type receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; CCL-34) and maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% newborn calf serum (NCS) and antibiotics. Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Research Center (RCB2202) and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. All cells were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

The A/duck/Hokkaido/1058/01(H4N5), A/duck/Hokkaido/228/03(H6N8), A/duck/Hokkaido/18/2000(H10N4), and A/Puerto Rico/8/34(H1N1) viruses were propagated in embryonated chicken eggs. The A/Osaka/364/2009(H1N1), A/Iwate/34/2019(H1N1), and A/Aichi/2/68(H3N2) viruses were propagated in MDCK cells. The A/Iwate/43/2019(H3N2) virus was propagated in avian-type receptor KO MDCK cells, which were established in this study. The A/Hong Kong/1073/99(H9N2) virus was generated using reverse genetics (51) and propagated in MDCK cells. Propagated viruses were aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Generation of sialic acid KO cells.

Avian-type receptor KO (human-type) cells, human-type receptor KO (avian-type) cells, avian- and human-type receptor KO (DKO) cells, and SLC35A1 KO (SLC35A1A1KO) cells were generated by knocking out the corresponding genes using a CRISPR/Cas9 system. The target sequences for six ST3Gals (ST3Gal-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6), two ST6Gals (ST6Gal-1 and -2), and the SLC35A1 gene were designed using CRISPR direct (https://crispr.dbcls.jp/) (Table S1), and each sequence was cloned into plentiCRISPR plasmids (52) (Addgene; plasmid number 52961, a gift from Feng Zhang) using NEBuilder (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). MDCK cells were transfected with the six ST3Gal-targeting plasmids to generate human-type cells, the two ST6Gal-targeting plasmids to generate avian-type cells, or the SLC35A1-targeting plasmid to generate SLC35A1KO cells using polyethylenimine (PEI; Polysciences, Warrington, PA). At 24 h posttransfection, the cell supernatant was replaced with medium containing 5 μg/mL of puromycin. Drug-resistant clones were randomly selected and their genomic DNA was sequenced. Cells possessing indels in all targeted genes were chosen for further analysis. DKO cells were generated by transfecting human-type cells with ST6Gal-targeting plasmids, followed by the same process as for the other KO cells.

Addback of genes involved in glycan sialylation to KO cells.

RNA was extracted from MDCK cells using ISOGEN (NIPPON Genetics, Tokyo, Japan), and cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription with oligo(dT) and RevaTraAce (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The coding sequences of ST3Gal1, ST6Gal1, and SLC35A1 were amplified using PCR with specific primers and cloned into the pS lentiviral vector (53) using NEBuilder (New England Biolabs).

To prepare recombinant lentivirus vectors expressing ST3Gal1, ST6Gal1, or SLC35A1, pS plasmids were cotransfected with p8.9QV (53) and pCAGGS-VSV-G, which express vesicular stomatitis virus G protein in 293T cells using PEI. At 48 h posttransfection, recombinant lentiviruses in the cell supernatant were concentrated using polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation and inoculated into the corresponding KO cells for gene addback. Human-type cells with ST3Gal1 addback were referred to as human-type/ST3Gal1 cells. Avian-type/ST6Gal1, DKO/ST3,6Gal1, and SLC35A1KO/SLC35A1 cells were also generated.

Lectin and antibody staining of KO and addback cells.

To stain the KO and addback cells, we used lectin Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA, biotinylated; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), which recognizes Neu5Acα2,6Gal, and the antibody HYB4 (54) (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan), which recognizes Neu5Acα2,3Gal. Cells were plated on an 8-well chamber slide (AGC Techno Glass, Shizuoka, Japan), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min, and blocked with skimmed milk at 21°C for 1 h. To stain Neu5Acα2,3Gal glycans, SNA (10 μL/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added to the cells at 150 μL/well, incubated at 21°C for 1 h, washed with PBS, and incubated with DyLight488 conjugate streptavidin (Vector Laboratories) (10 μL/mL in PBS) at 150 μL/well and 21°C for 1 h. To stain Neu5Acα2,3Gal glycans, HYB4 (15 μL/mL in PBS) was added to the cells at 150 μL/well, incubated at 4°C overnight, washed with PBS, and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:400 dilution in PBS) at 150 μL/well and 21°C for 1 h. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). Stained cells were observed under a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss LSM700; ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany).

Mass spectrometry analysis of N-linked glycans using the SALSA method.

N-linked glycans were analyzed using mass spectrometry (MS) according to the sialic acid linkage-specific alkylamidation (SALSA) method, as described previously (20, 21). α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acids were specifically amidated with different-length alkyl chains twice by alkylamidation, resulting in distinct linkages with different molecular masses. We prepared the following reagents for sialic acid derivatization: 1-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC-HCl), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole monohydrate (HOBt), isopropylamine hydrochloride (iPA-HCl), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methanol (MeOH), and aqueous methylamine [MA(aq)] (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan). After the wild-type MDCK, human-type, avian-type, DKO, and SLC35A1KO cells had been washed with PBS, they were lysed in Pierce immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (Thermo, Waltham, MA) and centrifuged to remove debris. Glycoproteins in the lysates were denatured using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). After cooling on ice, N-linked glycans were released using peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) and directly applied to hydrazide beads (BlotGlyco kit; Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan). The beads were added to the first alkylamidation solution (500 mM EDC-HCl, 500 mM HOBt, 2 M iPA-HCl in DMSO) and incubated at 25°C for 1 h with gentle agitation. The beads were washed three times with MeOH before being added to the second alkylamidation solution [10% MA(aq)] and gently agitated for a few seconds. After three washes with water, derivatized N-glycans were released from the beads in their native forms and their reducing ends labeled with 2-aminobenoic acid (2AA). N-glycans were ionized with 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), and mass spectra were obtained using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–quadrupole ion trap time of flight (MALDI-QIT-TOF) MS (AXIMA-Resonance; Shimadzu/Kratos, Manchester, UK) and MALDI-tandem TOF MS (MALDI-7090; Shimadzu/Kratos) in negative-ion mode.

Lectin array analysis of glycoproteins from wild-type and sialic acid KO cells.

Lectin microarray analysis was performed as described previously, with some modifications (22, 23). Briefly, wild-type and sialic acid KO MDCK cells were seeded on a 60-cm dish. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS for three times and labeled with 1 mg/mL of EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C for 1 h. The cells were then washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) to quench excess biotin-labeling reagents and lysed with TBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40 alternative, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor (Complete Ultra Mini; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Proteins were then diluted with probing buffer and applied to an activated LecChip (version 1.0; GlycoTechnica, Kanagawa, Japan) (Table S2). The array glass slide was incubated at 20°C overnight. After washing, the slides were overlaid with streptavidin, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and scanned using a GlycoStation Reader 1200 (GlycoTechnica). The obtained images were processed using GlycoStation ToolsPro Suite (version 1.5). The net intensity of each lectin was calculated from the mean value of three spots minus the background.

Generation of PB2-stably expressing cells.

PB2-stably expressing wild-type MDCK, human-type, and avian-type cells were generated (WT/PB2, human-type/PB2, and avian-type/PB2 cells, respectively). The PB2 coding sequence from A/WSN/33(H1N1) was cloned into the pCAGGS-BLAST plasmid (55), which was transfected into wild-type, human-type, and avian-type cells with PEI. The transfected cells were treated with 10 μg/mL of blasticidin (Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and drug-resistant cells were randomly cloned. PB2 expression was confirmed by observing GFP-expressing PB2-deficient virus propagation (29).

Evaluation of virus growth in cells.

Cells were inoculated with viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 and maintained in MEM containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin (MEM-BSA) and 1 μg/mL of l-(tosylamido-2-phenyl) ethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ). Supernatants were collected every 12 h, and viral titers were measured using a plaque assay.

Generation of PB2KO H4N5 virus.

The HA and NA segments of the duck/2001(H4N5) virus were cloned into the RNA expression plasmid pHH21 (56). Wild-type and mutant PB2KO H4N5 viruses were generated using reverse genetics, as described previously (56). Briefly, wild-type or mutant HA and NA from duck/2001(H4N5), PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS from A/WSN/33, and the pPolIPB2(300)GFP(300) viral RNA-expressing plasmid (57) were transfected together with PB2, PB1, PA, and NP from A/WSN/33 protein-expressing plasmids into 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, supernatants containing PB2KO viruses were harvested, propagated in WT/PB2 cells, and stored at −80°C.

Adaptation of H4N5 virus to human-type/PB2 cells.

Six dishes (6-cm diameter) containing human-type/PB2 cells were infected with the PB2KO H4N5 and maintained in MEM-BSA with 1 μg/mL of TPCK trypsin. Three days postinfection, viruses were collected from the supernatants and inoculated into fresh human-type/PB2 cells. After six passages, the viruses were collected and their entire genome was Sanger sequenced.

Evaluation of virus binding to synthetic glycans.

Solid-phase binding assays were performed as described previously (58), with some modifications. Briefly, viruses were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 3 h using a P32ST rotor (CP80WX; Himac, Tokyo, Japan) through a 30% sucrose cushion. The pellets were suspended in a small volume of PBS and the protein concentration as HA titer was measured. Each virus was diluted in PBS to 64 HA/100 μL (ranging from 2.2 to 9.1 μg/mL of protein per virus [Table S3]) and added (100 μL/well) to ELISA plates (Maxisorp Nunc-immuno plates; Thermo). Since Iwate/2019(H3N2) did not show any detectable HA titer, the virus was diluted with a protein concentration of 5.1 μg/mL in PBS per well. Once the viruses had adsorbed to the wells at 4°C overnight, they were washed with ice-cold PBS, 4% BSA in PBS was added (200 μL/well), and the plate was blocked at 21°C for 2 h. After two washes with ice-cold PBS, the wells were reacted with 50 μL of 3′SLN (Neu5Acα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ) or 6′SLN (Neu5Acα2,6Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ) artificial synthetic glycans conjugated with biotin (3′SLN-C3-BP or 6′SLN-C3-BP, respectively; GlycoNZ, Auckland, New Zealand) diluted to 3, 1.5, 0. 75, 0.375, 0.1875, 0.09375, and 0.046875 μg/mL in reaction buffer (RB; 0.02% BSA, 1 μM oseltamivir [Wako Chemicals, Japan] in PBS) at 4°C overnight. The wells were then washed twice with PBS and reacted with avidin/biotin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) complex (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories) at 50 μL/well at 4°C for 1 h. After a further five washes, 100 μL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidene (TMB) substrate (Vector Laboratories) was added to each well and incubated at 21°C for 12 min to detect a reaction. Next, the reaction was stopped with 2% sulfuric acid (25 μL/well), and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (iMark; Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan).

Solid-phase binding assays were used to reduce nonspecific reactions to assess PB2KO H4N5 viruses. Briefly, ELISA plates were incubated with streptavidin (100 μL/well, diluted to 1 μg/100 μL in PBS) at 21°C for 3 h (59), washed twice with PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C with artificial synthetic glycopolymers (3′SLN-C3-BP or 6′SLN-C3-BP; GlycoNZ), diluted in PBS to 3, 1.5, 0.75, 0.375, 0.1875, 0.09375, 0.09375, and 0.046875 μg/mL at 50 μL/well. After blocking with Pierce protein-free (TBS) blocking buffer (200 μL/well; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 21°C for 3 h, the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 100 μL of H4 PB2-deficient viruses (rH4/PB2KO, -I111L, -Q226L, -Q226R, -A44S, or -I111L+A44S) diluted to 32 HA/100 μL in PBS. The plates were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, reacted with mouse antiserum against duck/2000(H4N5) (1:100 in dilution buffer; Can Get Signal solution 1; TOYOBO) at 50 μL/well and 4°C for 1 h, washed a further two times, and incubated with anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies with HRP (number NA9340; GE Healthcare) (1:4,000) at 50 μL/well at 4°C for 1 h. After a further five washes, the plates were reacted with TMB substrate (100 μL/well; Vector Laboratories) at 21°C for 12 min, and 2% sulfuric acid was added (25 μL/well) to stop the reaction. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Molecular dynamics simulation of human-type glycan and HA protein.

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of H4-HA, generated by X-ray crystallography with 2.10-Å resolution, was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank archive (PDB code 5XL7) to provide data for HA possessing HA1-226L combined with human-type glycan analog LSTc (Neu5Acα2,6Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,3Galβ1,4Glc). The mutagenesis wizard tool (PyMOL software) was used to generate mutant HA possessing Q or R at position 226 in HA1. Molecular dynamics simulation was conducted using the Desmond simulation package (60) (Schrödinger release 2019–1, Desmond molecular dynamics system; DE Shaw Research, New York, NY). Based on the position of HA at the beginning of the simulation, the RMSD of the protein at each time point was calculated for 100 ns. The RMSD of the LSTc was calculated based on its relative position to HA. The binding free energies of the LSTc and HA were evaluated using the MM-GBSA method (61).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yoshihiro Sakoda (Hokkaido University) for providing the viruses.

This work, including the efforts of Shin Murakami, was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) (grant no. 17K19319) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This work, including the efforts of Taisuke Horimoto, was supported by Grant-in-Aid and for Scientific Research (A) (grant no. 18H03971) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Shin Murakami, Email: shin-murakami@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Taisuke Horimoto, Email: taihorimoto@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Anice C. Lowen, Emory University School of Medicine

REFERENCES

- 1.Connor RJ, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG, Paulson JC. 1994. Receptor specificity in human, avian, and equine H2 and H3 influenza virus isolates. Virology 205:17–23. 10.1006/viro.1994.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers GN, Paulson JC. 1983. Receptor determinants of human and animal influenza virus isolates: differences in receptor specificity of the H3 hemagglutinin based on species of origin. Virology 127:361–373. 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T. 2006. H5N1 virus attachment to lower respiratory tract. Science 312:399. 10.1126/science.1125548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature 440:435–436. 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulson JC, Rogers GN. 1987. Resialylated erythrocytes for assessment of the specificity of sialyloligosaccharide binding proteins. Methods Enzymol 138:162–168. 10.1016/0076-6879(87)38013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambaryan AS, Matrosovich MN. 1992. A solid-phase enzyme-linked assay for influenza virus receptor-binding activity. J Virol Methods 39:111–123. 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada S, Suzuki Y, Suzuki T, Le MQ, Nidom CA, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Muramoto Y, Ito M, Kiso M, Horimoto T, Shinya K, Sawada T, Kiso M, Usui T, Murata T, Lin Y, Hay A, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. Nature 444:378–382. 10.1038/nature05264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkataraman M, Sasisekharan R, Raman R. 2015. Glycan array data management at Consortium for Functional Glycomics. Methods Mol Biol 1273:181–190. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2343-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens J, Blixt O, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Glycan microarray technologies: tools to survey host specificity of influenza viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:857–864. 10.1038/nrmicro1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrd-Leotis L, Jia N, Dutta S, Trost JF, Gao C, Cummings SF, Braulke T, Müller-Loennies S, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Steinhauer DA, Cummings RD. 2019. Influenza binds phosphorylated glycans from human lung. Sci Adv 5:eaav2554. 10.1126/sciadv.aav2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd-Leotis L, Liu R, Bradley KC, Lasanajak Y, Cummings SF, Song X, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Galloway SE, Culhane MR, Smith DF, Steinhauer DA, Cummings RD. 2014. Shotgun glycomics of pig lung identifies natural endogenous receptors for influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E2241–E2250. 10.1073/pnas.1323162111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiono T, Okamatsu M, Nishihara S, Takase-Yoden S, Sakoda Y, Kida H. 2014. A chicken influenza virus recognizes fucosylated α2,3 sialoglycan receptors on the epithelial cells lining upper respiratory tracts of chickens. Virology 456–457:131–138. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng W, de Vries RP, Grant OC, Thompson AJ, McBride R, Tsogtbaatar B, Lee PS, Razi N, Wilson IA, Woods RJ, Paulson JC. 2017. Recent H3N2 viruses have evolved specificity for extended, branched human-type receptors, conferring potential for increased avidity. Cell Host Microbe 21:23–34. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi T, Takano M, Kurebayashi Y, Masuda M, Kawagishi S, Takaguchi M, Yamanaka T, Minami A, Otsubo T, Ikeda K, Suzuki T. 2014. N-glycolylneuraminic acid on human epithelial cells prevents entry of influenza A viruses that possess N-glycolylneuraminic acid binding ability. J Virol 88:8445–8456. 10.1128/JVI.00716-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takada K, Kawakami C, Fan S, Chiba S, Zhong G, Gu C, Shimizu K, Takasaki S, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Lopes TJS, Dutta J, Khan Z, Kriti D, van Bakel H, Yamada S, Watanabe T, Imai M, Kawaoka Y. 2019. A humanized MDCK cell line for the efficient isolation and propagation of human influenza viruses. Nat Microbiol 4:1268–1273. 10.1038/s41564-019-0433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Duncker I, Dupré T, Piller V, Piller F, Candelier JJ, Trichet C, Tchernia G, Oriol R, Mollicone R. 2005. Genetic complementation reveals a novel human congenital disorder of glycosylation of type II, due to inactivation of the Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter. Blood 105:2671–2676. 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takashima S, Tsuji S. 2011. Functional diversity of mammalian sialyltransferases. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol 23:178–193. 10.4052/tigg.23.178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takashima S, Tsuji S, Tsujimoto M. 2003. Comparison of the enzymatic properties of mouse β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferases, ST6Gal I and II. J Biochem 134:287–296. 10.1093/jb/mvg142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu VC, Whittaker GR. 2004. Influenza virus entry and infection require host cell N-linked glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:18153–18158. 10.1073/pnas.0405172102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishikaze T, Tsumoto H, Sekiya S, Iwamoto S, Miura Y, Tanaka K. 2017. Differentiation of sialyl linkage isomers by one-pot sialic acid derivatization for mass spectrometry-based glycan profiling. Anal Chem 89:2353–2360. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanamatsu H, Nishikaze T, Miura N, Piao J, Okada K, Sekiya S, Iwamoto S, Sakamoto N, Tanaka K, Furukawa JI. 2018. Sialic acid linkage specific derivatization of glycosphingolipid glycans by ring-opening aminolysis of lactones. Anal Chem 90:13193–13199. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiono T, Matsuda A, Wagatsuma T, Okamatsu M, Sakoda Y, Kuno A. 2019. Lectin microarray analyses reveal host cell-specific glycan profiles of the hemagglutinins of influenza A viruses. Virology 527:132–140. 10.1016/j.virol.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuno A, Uchiyama N, Koseki-Kuno S, Ebe Y, Takashima S, Yamada M, Hirabayashi J. 2005. Evanescent-field fluorescence-assisted lectin microarray: a new strategy for glycan profiling. Nat Methods 2:851–856. 10.1038/nmeth803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisler C, Jarvis DL. 2011. Letter to the Glyco-Forum: effective glycoanalysis with Maackia amurensis lectins requires a clear understanding of their binding specificities. Glycobiology 21:988–993. 10.1093/glycob/cwr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin YP, Shaw M, Gregory V, Cameron K, Lim W, Klimov A, Subbarao K, Guan Y, Krauss S, Shortridge K, Webster R, Cox N, Hay A. 2000. Avian-to-human transmission of H9N2 subtype influenza A viruses: relationship between H9N2 and H5N1 human isolates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:9654–9658. 10.1073/pnas.160270697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito T, Lim W, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Kida H, Nishimura S, Tashiro M. 2001. Characterization of a human H9N2 influenza virus isolated in Hong Kong. Vaccine 20:125–133. 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, Li C, Kawakami E, Yamada S, Kiso M, Suzuki Y, Maher EA, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2012. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature 486:420–428. 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science 336:1534–1541. 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Victor ST, Watanabe S, Katsura H, Ozawa M, Kawaoka Y. 2012. A replication-incompetent PB2-knockout influenza A virus vaccine vector. J Virol 86:4123–4128. 10.1128/JVI.06232-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Carney PJ, Chang JC, Guo Z, Villanueva JM, Stevens J. 2015. Structure and receptor binding preferences of recombinant human A(H3N2) virus hemagglutinins. Virology 477:18–31. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin YP, Xiong X, Wharton SA, Martin SR, Coombs PJ, Vachieri SG, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Liu J, Skehel JJ, Gamblin SJ, Hay AJ, Daniels RS, McCauley JW. 2012. Evolution of the receptor binding properties of the influenza A(H3N2) hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:21474–21479. 10.1073/pnas.1218841110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilyushina NA, Bovin NV, Webster RG. 2012. Decreased neuraminidase activity is important for the adaptation of H5N1 influenza virus to human airway epithelium. J Virol 86:4724–4733. 10.1128/JVI.06774-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobita K, Sugiura A, Enomote C, Furuyama M. 1975. Plaque assay and primary isolation of influenza A viruses in an established line of canine kidney cells (MDCK) in the presence of trypsin. Med Microbiol Immunol 162:9–14. 10.1007/BF02123572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers GN, Paulson JC, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. 1983. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature 304:76–78. 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens J, Blixt O, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404–410. 10.1126/science.1124513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richard M, Schrauwen EJ, de Graaf M, Bestebroer TM, Spronken MI, van Boheemen S, de Meulder D, Lexmond P, Linster M, Herfst S, Smith DJ, van den Brand JM, Burke DF, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. 2013. Limited airborne transmission of H7N9 influenza A virus between ferrets. Nature 501:560–563. 10.1038/nature12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson JS, Nicolson C, Harvey R, Johnson R, Major D, Guilfoyle K, Roseby S, Newman R, Collin R, Wallis C, Engelhardt OG, Wood JM, Le J, Manojkumar R, Pokorny BA, Silverman J, Devis R, Bucher D, Verity E, Agius C, Camuglia S, Ong C, Rockman S, Curtis A, Schoofs P, Zoueva O, Xie H, Li X, Lin Z, Ye Z, Chen LM, O'Neill E, Balish A, Lipatov AS, Guo Z, Isakova I, Davis CT, Rivailler P, Gustin KM, Belser JA, Maines TR, Tumpey TM, Xu X, Katz JM, Klimov A, Cox NJ, Donis RO. 2011. The development of vaccine viruses against pandemic A(H1N1) influenza. Vaccine 29:1836–1843. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eggink D, Spronken M, van der Woude R, Buzink J, Broszeit F, McBride R, Pawestri HA, Setiawaty V, Paulson JC, Boons G-J, Fouchier RAM, Russell CA, de Jong MD, de Vries RP. 2020. Phenotypic effects of substitutions within the receptor binding site of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus observed during human infection. J Virol 94:e00195-20. 10.1128/JVI.00195-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stray SJ, Cummings RD, Air GM. 2000. Influenza virus infection of desialylated cells. Glycobiology 10:649–658. 10.1093/glycob/10.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karakus U, Pohl MO, Stertz S. 2020. Breaking the convention: sialoglycan variants, coreceptors, and alternative receptors for influenza A virus entry. J Virol 94:e01357-19. 10.1128/JVI.01357-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Londrigan SL, Turville SG, Tate MD, Deng YM, Brooks AG, Reading PC. 2011. N-linked glycosylation facilitates sialic acid-independent attachment and entry of influenza A viruses into cells expressing DC-SIGN or L-SIGN. J Virol 85:2990–3000. 10.1128/JVI.01705-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng WC, Londrigan SL, Nasr N, Cunningham AL, Turville S, Brooks AG, Reading PC. 2016. The C-type lectin langerin functions as a receptor for attachment and infectious entry of influenza A virus. J Virol 90:206–221. 10.1128/JVI.01447-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Vries E, Tscherne DM, Wienholts MJ, Cobos-Jiménez V, Scholte F, García-Sastre A, Rottier PJM, de Haan CAM. 2011. Dissection of the influenza A virus endocytic routes reveals macropinocytosis as an alternative entry pathway. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001329. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karakus U, Thamamongood T, Ciminski K, Ran W, Günther SC, Pohl MO, Eletto D, Jeney C, Hoffmann D, Reiche S, Schinköthe J, Ulrich R, Wiener J, Hayes MGB, Chang MW, Hunziker A, Yángüez E, Aydillo T, Krammer F, Oderbolz J, Meier M, Oxenius A, Halenius A, Zimmer G, Benner C, Hale BG, García-Sastre A, Beer M, Schwemmle M, Stertz S. 2019. MHC class II proteins mediate cross-species entry of bat influenza viruses. Nature 567:109–112. 10.1038/s41586-019-0955-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Vries RP, de Vries E, Bosch BJ, de Groot RJ, Rottier PJM, de Haan CAM. 2010. The influenza A virus hemagglutinin glycosylation state affects receptor-binding specificity. Virology 403:17–25. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang CC, Chen JR, Tseng YC, Hsu CH, Hung YF, Chen SW, Chen CM, Khoo KH, Cheng TJ, Cheng YSE, Jan JT, Wu CY, Ma C, Wong CH. 2009. Glycans on influenza hemagglutinin affect receptor binding and immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:18137–18142. 10.1073/pnas.0909696106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun X, Akila Jayaraman A, Maniprasad P, Raman R, Houser KV, Pappas C, Zeng H, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2013. N-linked glycosylation of the hemagglutinin protein influences virulence and antigenicity of the 1918 pandemic and seasonal H1N1 influenza A viruses. J Virol 87:8756–8766. 10.1128/JVI.00593-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu CY, Lin CW, Tsai TI, Lee CCD, Chuang HY, Chen JB, Tsai MH, Chen BR, Lo PW, Liu CP, Shivatare VS, Wong CH. 2017. Influenza A surface glycosylation and vaccine design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:280–285. 10.1073/pnas.1617174114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Vries RP, Smit CH, de Bruin E, Rigter A, de Vries E, Cornelissen LAHM, Eggink D, Chung NPY, Moore JP, Sanders RW, Hokke CH, Koopmans M, Rottier PJM, de Haan CAM. 2012. Glycan-dependent immunogenicity of recombinant soluble trimeric hemagglutinin. J Virol 86:11735–11744. 10.1128/JVI.01084-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medina RA, Stertz S, Manicassamy B, Zimmermann P, Sun X, Albrecht RA, Uusi-Kerttula H, Zagordi O, Belshe RB, Frey SE, Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A. 2013. Glycosylations in the globular head of the hemagglutinin protein modulate the virulence and antigenic properties of the H1N1 influenza viruses. Sci Transl Med 5:187ra70. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamiki H, Matsugo H, Kobayashi T, Ishida H, Takenaka-Uema A, Murakami S, Horimoto T. 2018. A PB1-K577E mutation in H9N2 influenza virus increases polymerase activity and pathogenicity in mice. Viruses 10:653. 10.3390/v10110653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. 2014. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods 11:783–784. 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimojima M, Ikeda Y, Kawaoka Y. 2007. The mechanism of Axl-mediated Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis 196:S259–S263. 10.1086/520594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hidari KIPJ, Yamaguchi M, Ueno F, Abe T, Yoshida K, Suzuki T. 2013. Influenza virus utilizes N-linked sialoglycans as receptors in A549 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 436:394–399. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen T, Ueda Y, Dodge JE, Wang Z, Li E. 2003. Establishment and maintenance of genomic methylation patterns in mouse embryonic stem cells by Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Mol Cell Biol 23:5594–5605. 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5594-5605.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, Hobom G, Kawaoka Y. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:9345–9350. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muramoto Y, Takada A, Fujii K, Noda T, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Watanabe S, Horimoto T, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Hierarchy among viral RNA (vRNA) segments in their role in vRNA incorporation into influenza A virions. J Virol 80:2318–2325. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2318-2325.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matrosovich MN, Gambaryan AS. 2012. Solid-phase assays of receptor-binding specificity. Methods Mol Biol 865:71–94. 10.1007/978-1-61779-621-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu Y, Yang Y, Liu W, Liu X, Yang D, Sun Z, Ju Y, Chen S, Peng D, Liu X. 2015. Comparison of biological characteristics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses isolated from different hosts. Arch Virol 160:917–927. 10.1007/s00705-015-2337-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bowers KJ, Chow E, Xu H, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, Gregersen BA, Klepeis JL, Kolossvary I, Moraes MA, Sacerdoti FD, Salmon JK, Shan Y, Shaw DE. 2006. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE SC2006 Conference on High Performance Networking and Computing, Tampa, FL, USA. 10.1145/1188455.1188544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shivakumar D, Williams J, Wu Y, Damm W, Shelley J, Sherman W. 2010. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the opls force field. J Chem Theory Comput 6:1509–1519. 10.1021/ct900587b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1-S6; Fig. S1-S5. Download jvi.00416-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, pdf)