Abstract

The complete hrp-hrc-hrmA cluster of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 encodes 28 polypeptides. A saprophytic bacterium carrying this cluster is capable of secreting HrpZ—a harpin encoded by hrpZ—in an hrp-dependent manner, which suggests that this cluster contains sufficient components to assemble functional type III secretion machinery. Sequence data show that HrcJ and HrcC are putative outer membrane proteins, and nonpolar mutagenesis demonstrates they are all required for HrpZ secretion. In this study, we investigated the cellular localization of the HrcC and HrcJ proteins by Triton solubilization, sucrose-gradient isopycnic centrifugation, and immunogold labeling of the bacterial cell surface. Our results indicate that HrcC is indeed an outer membrane protein and that HrcJ is located between both membranes. Their membrane localization suggests that they might be involved in the formation of a supramolecular structure for protein secretion.

The hypersensitive response (HR) of higher plants elicited by phytopathogenic bacteria is characterized by rapid cell collapse at infection sites and is associated with active defense (19). The hrp (HR and pathogenicity) genes of phytobacteria which are necessary for the HR are conserved among many gram-negative phytobacteria, including Pseudomonas syringae, Ralstonia (Pseudomonas) solanacearum, Xanthomonas campestris, Erwinia amylovora, Erwinia stewartii, and Erwinia chrysanthemi (1, 16). Based on their putative functions, the hrp gene products can be classified into three categories: (i) a delicate regulatory system, (ii) a type III secretion pathway, and (iii) extracellular or surface-associated proteins (24).

A 25-kb hrp-hrm cluster clone (pHIR11) isolated from P. syringae pv. syringae 61 allows saprophytes to cause the HR in tobacco, indicating that the cluster contains sufficient genes for HR elicitation (13). Nine hrp genes, which have been newly designated as hrc (HR and conserved) genes, are widely conserved in the type III secretion apparatus used by Yersinia, Shigella, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, Xanthomonas, and Erwinia spp. (5, 16). HrcC (= HrpH) is homologous to PulD, pIV, and other members of the outer membrane secretin superfamily of the general secretion pathway (1, 14, 30). The hrcJ (= hrpC) gene in the hrpZ operon encodes a putative lipoprotein with extensive similarity to YscJ and MxiJ (2, 15, 26). Eight of the Hrc proteins have additional homologues involved in flagellar biogenesis (1, 15). HrcJ is one of these and is homologous to FliF (15). At least three proteins, InvG, PrgH, and PrgK in Salmonella typhimurium, are identified from purified needle complexes, and InvG and PrgK are homologous to HrcC and HrcJ, respectively (21). Based on sequence conservation, these Hrc proteins might assemble into a supramolecular structure similar to the needle complex found in the S. typhimurium envelope. However, little is known about how many Hrc-Hrp proteins there are and the mechanism of how they are involved in assembly of the complex. In this report, we provide evidence for cellular locations of HrcC and HrcJ, based on cell fractionation with Triton X-100 extraction, sucrose-gradient isopycnic centrifugation, and cell surface immunogold labeling, to gain insight into the roles played by these two proteins in assembly of the type III secretion machinery. Also, our analysis of HrcJ has provided the first evidence for this class of proteins of an association with both membranes.

Biological functions of HrcJ and HrcC proteins.

hrcJ and hrcC are the third genes of hrpZ and hrpC operons, respectively. For characterization of their individual function, nonpolar mutations were made by inserting an nptII gene, which lacks a rho-independent transcription terminator, in the coding region, and the resultant mutants are Pss61-N314 (ΔhrcJ::nptII) and Pss61-N393 (ΔhrcC::nptII) (3, 6). Both mutations were confirmed by DNA gel blot hybridization with nptII as a probe (data not shown). Intact hrcJ and hrcC genes were generated by PCR and cloned individually into pRK415 (18) for complementation. After infiltrating into tobacco leaves at 108 CFU/ml, these two mutants were no longer able to elicit the HR, and their complementation clones can restore the ability for HR elicitation (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis with an anti-HrpZ serum was applied to determine the involvement of hrcJ and hrcC genes in harpin secretion. The HrpZ protein was detected in the cell pellet of Pss61-N314 and Pss61-N393, indicating that these mutants cannot secrete HrpZ, and their corresponding genes can restore the phenotype (data not shown). Those results reveal that HrcJ and HrcC proteins are indeed required for HR elicitation and harpin secretion.

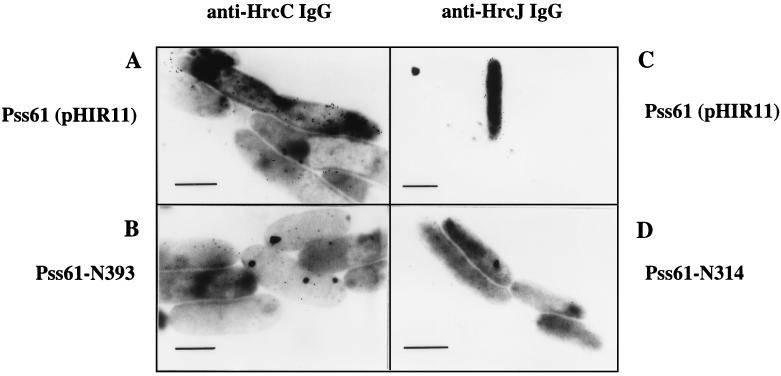

Observation of surface localization of HrcJ and HrcC by electron microscopy.

The question whether HrcJ and HrcC were localized on the outer membrane was firstly addressed by immunogold labeling and electron microscopy observation (7). Bacteria grown in 1 ml of Hrp-derepressing minimal medium (17) were harvested, washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), treated with Tris-EDTA (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 2 mM EDTA) for 1 h on ice (12), and then blocked with PBS–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. For cell surface immunogold labeling, anti-HrcC and anti-HrcJ immunoglobulins G (IgGs) were further purified from prepared antisera (6, 29), according to standard procedures (11). To remove nonspecific antibodies, purified anti-HrcJ and anti-HrcC IgG were preabsorbed with Tris-EDTA-treated corresponding mutants at a ratio of 30 μg of IgG to 0.2 mg of wet cell pellets in 250 μl of PBS–1% BSA solution. After prehybridization, an equal volume of fresh PBS–1% BSA and preabsorbed IgGs were mixed with the bacterial pellet, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. The protein-IgG complex was detected with protein A-gold conjugate (20-nm gold particles) (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) under the conditions recommended by the supplier. The labeled bacteria were fixed for 2 h at 4°C with 50 to 100 μl of 1% osmium tetroxide (Merck, Frankfurt, Germany) and observed with a JEOL 200 CX electron microscope at 80 kV. The electron micrographs of P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11), Pss61-N314, and Pss61-N393 are shown in Fig. 1. The distribution of gold particles over the cell surface was essentially homogeneous for P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11), and no significant labeling can be seen in Pss61-N314 and Pss61-N393 mutants.

FIG. 1.

Immunoelectron microscopic localization of HrcC and HrcJ proteins at the cell surface of P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11) and nonpolar hrcC (Pss61-N393) and hrcJ (Pss61-N314) mutants. Bacteria were treated with anti-HrcC IgG (A and B) or anti-HrcJ IgG (C and D) and then detected with protein A-gold (20-nm) conjugate as described in the text. Bars, 1 μm.

In this experiment, we found that HrcJ can be detected by its antiserum and protein A-gold only after Tris-EDTA treatment which is applied for membrane destabilization. HrcJ and its homologues are putative lipoproteins and probably attach to the outer membrane via their lipid moieties. Based on the current models of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, lipoproteins are buried in the inner leaflet of the outer membrane and therefore not exposed to the cell surface (25, 33). Unlike HrcJ, HrcC can be detected without Tris-EDTA treatment, but Tris-EDTA-treated cells have more labeled gold particles. We speculated that the low-efficiency labeling may due to the interference of other cell surface proteins, such as HrpA pilin (1); however, there is not yet direct evidence in favor of this hypothesis.

HrcC is an outer membrane protein, and HrcJ is present in outer and inner membranes.

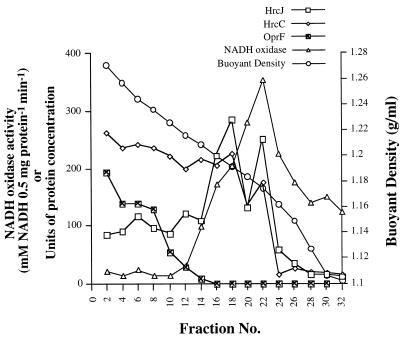

To further investigate the cellular location of HrcJ and HrcC, we took a biochemical approach to examining their distribution by cellular fractionation and analyzed the fractions by using immunoblots visualized with HrcC or HrcJ antiserum. The procedure of sucrose-gradient isopycnic centrifugation was modified slightly from a previous protocol (28), and all steps were carried out at 4°C except where specifically stated otherwise. In brief, P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11) harvested from Hrp-derepressing minimal medium was resuspended in a solution containing 20% (wt/wt) sucrose, 10 μg of DNase per ml, 10 μg of RNase per ml, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). These cells were disrupted by passage through a prechilled French pressure cell three times at 18,000 lb/in2 and centrifuged at 1,000 to 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove unbroken cells. The pellet containing membrane proteins was obtained from ultracentrifugation (1 h at 100,000 × g), resuspended in 20% (wt/wt) sucrose–10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)–5 mM EDTA, overlaid on top of 30 to 60% sucrose-gradient solutions, and ultracentrifuged at 274,000 × g for 40 h. After centrifugation and fractionation, each fraction was subjected to assays of refractive index (Abbe-3L Refractometer; Milton Roy Co., Rochester, N.Y.), NADH oxidase activity (27), and protein concentration (Pierce Coomassie protein assay reagent) and then precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 1 h. The precipitated proteins were dissolved in 2× loading buffer (0.625 M Tris [pH 6.8], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, and 2% β-mercaptoethanol) to a final concentration of 1 μg/μl and boiled for 5 min before SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A 10-μg sample of each fraction was applied to the gel, except that 20 μg was used for the detection of OprF—an OmpA homologue in Pseudomonas sp.—by an OmpA antibody (kindly provided by U. Henning of Max-Planck-Institut für Biologie, Tubingen, Germany). Each fraction was separated by SDS–8% (for HrcC) or SDS–10% (for HrcJ and OprF) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Inc., Bedford, Mass.) in a TE70 semidry transfer unit (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.), and probed individually with anti-HrcC, anti-HrcJ, or anti-OmpA antibodies. Immunodetection was done by an alkaline phosphatase-based chemiluminescent assay with 0.25 mM disodium 2-chloro-5 (4-methoxyspiro{1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro)-tricyclo(3.3.1.1) decan}-4-yl)-1-phenyl phosphate (CDP-Star; Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), and the results were quantified by a densitometer (Intelligent Quantifier; Bio Image). NADH oxidase activity and the presence of OprF were used as markers of inner and outer membranes, respectively. In Fig. 2, the majority of HrcC was detected within buoyant densities of 1.27 to 1.19 (fractions 2 to 18), whereas HrcJ was 1.2 to 1.17 (fractions 16 to 23). The distribution of HrcC and HrcJ in different fraction numbers reveals that these two proteins have different cellular localization. Moreover, HrcJ was found in both outer and inner membrane fractions at a ratio of 1:2, indicating that most HrcJ molecules were on the inner membrane.

FIG. 2.

Isopycnic centrifugation analysis of the total membrane preparation from P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11). The left vertical axis gives the units of NADH oxidase activity and the density of protein bands from immunoblots (determined by a laser Intelligent Quantifier densitometer). The right axis shows the sucrose buoyant density measured by a refractometer. The symbols are presented at the top.

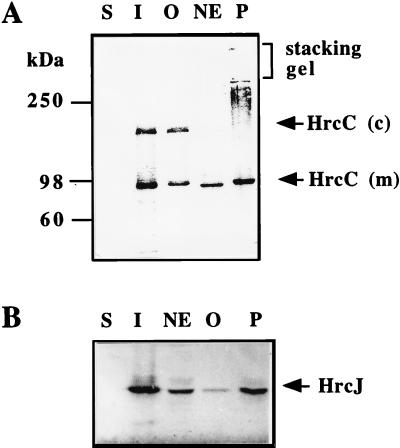

For Triton extraction of membrane proteins, bacteria were grown and harvested as described above and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 0.25 M sucrose and 1 mM PMSF for brief sonication (Sonicator XL-2020; Heat Systems Ultrasonics, Inc., Farmingdale, N.Y.). The membrane fraction was obtained as described above, dissolved in 1.0 ml of Triton-Mg solution (1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM PMSF), and mixed vigorously for 30 min at room temperature. The separation of inner and outer membrane proteins was achieved by centrifugation at 15,600 × g for 30 min. The supernatants containing inner membrane proteins were precipitated with 5% (wt/vol) TCA, and the pellets were further fractionated into outer membrane and nonextracted portions with Triton-EDTA solution (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF) and a 30-min centrifugation at 12,000 × g (31, 32). The supernatants which contain outer membrane proteins were precipitated by TCA and resuspended in 2× loading buffer, as was done for the pellets (nonextracted portion). All samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described above. The results also revealed that HrcC was found predominantly in the outer membrane fractions (Fig. 3A), whereas HrcJ was present in both membranes (Fig. 3B). HrpA1 of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, one of the HrcC homologues, has also been determined to be an outer membrane protein by sucrose-gradient fractionation and immunoblot analysis (34). Our data further support the idea that the subcellular location of HrcC family proteins in type III secretion machinery is in the outer membrane.

FIG. 3.

Triton X-100 fractionation of P. syringae pv. syringae 61(pHIR11). S, soluble proteins (periplasmic plus cytoplasmic); I, inner membrane proteins; O, outer membrane proteins; NE, nonextracted proteins; P, phenol-denatured proteins. The phenol extraction procedure was described previously by Hancock and Nikaido (9). After each treatment, phenol-denatured proteins were recovered by high-speed centrifugation and finally resuspended in 2× loading buffer for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analyses.

From the results of Triton extraction and immunoblotting with anti-HrcC antibody, a high-molecular-weight (Mr) band was found corresponding to the monomeric HrcC. In addition, a larger band with an estimated molecular mass of 190 kDa was observed, and it can be dissociated by phenol (Fig. 3A, lane P), indicating that it might be a protein complex containing HrcC. Like its homologous proteins pIV (22), PulD (10), XcpQ (4), InvG (8), and YscC (20), this complex is also SDS resistant (in 4% SDS) and heat stable (boiling at 100°C for 5 min). Salmonella InvG and Yersinia YscC are both involved in delivering effector proteins into animal cells. In vitro studies showed that YscC (20), InvG (8), and pIV (23) could form a ring-shaped multimeric complex, which is structurally similar to the multimer of PulD and XcpQ of the type II secretin superfamily. The similarities of amino acid sequence and biochemical features suggest that HrcC might also form a multimeric complex in the outer membrane. Due to the fact that plant cells have cell wall, we speculate that there might be an appendage-like structure attached to the HrcC multimer for assisting the translocation process, but the overall structure remains elusive.

In the assembly of the export apparatus, both HrcJ and HrcC, which possess N-terminal signal peptides, were believed to pass across the inner membrane in a Sec-dependent manner (30). After cleavage of signal peptides, HrcC is targeted to the outer membrane, and HrcJ is integrated into the inner and outer membrane, apparently by its C-terminal hydrophobic domain and the N-terminal lipid moiety, respectively. The latter finding is consistent with structure-based predictions for the Yersinia YscJ and Shigella MxiJ proteins (2, 26). The results of Triton extraction showed that a small amount of HrcC was present at the Triton-soluble fraction (Fig. 3A, lane I), and some HrcJ was seen in the Triton-insoluble sample (Fig. 3B, lanes O and NE). By analyzing the fractions of sucrose-gradient isopycnic centrifugation, we also found that a part of HrcC was distributed in the intermediate and inner membrane fractions, accompanying the peak of HrcJ (Fig. 2). The coexistence of HrcC and HrcJ may result from protein interaction or strong association with both membranes. Our attempts to evaluate HrcC-HrcJ interaction by immunoprecipitation in a wild-type strain were not successful (data not shown), which raises the possibilities that the association of HrcC and HrcJ is not strong enough to be resolved by this method or that these two proteins do not interact with each other directly but need another component(s), such as other Hrc-Hrp proteins, to participate in the association.

Conclusion.

In accordance with the association of HrcJ with both membranes and its similarity to the N terminus of FliF (15), HrcJ may be the major part of a core structure and may be involved in the primary assembly of the Hrp translocation system. In addition to HrcJ, several other Hrc proteins have homology with flagellar components (1). The needle structure isolated from the S. typhimurium type III secretion system (21) shows a structure similar to that of the flagellar export machinery, which further strengthens the intriguing possibility that HrcC (an InvG homologue) and HrcJ (a PrgK homologue) are both involved in forming a supramolecular structure in the bacterial envelope. This structural similarity between the type III and flagellar export systems also suggests that they might have similar mechanisms to assemble their components into a complex. Moreover, the type III systems in plant and animal pathogens are capable of delivering various—homologous and heterologous—effector proteins to the interior of host cells, indicating that they share a conserved secretion mechanism (for reviews, see references 1 and 16 and the references therein). Given the use of similar secretion systems to secrete different effector proteins, we speculate that these systems may be functionally interchangeable among animal and plant pathogens. However, the fundamental difference between plant and animal cells brings up the key questions of (i) how bacteria use similar structures to translocate effector proteins into host cells with such different surfaces (cell wall versus no cell wall), (ii) how bacteria regulate the translocation process, and (iii) how effector proteins are involved in diseases caused by different pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Collmer for critically reading the manuscript and U. Henning for providing anti-OmpA antibody.

This research was supported by NSC grant 85-2311-B-005-037 and the Chinese Rotary Club.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfano J, Collmer A. The type III (Hrp) secretion pathway of plant pathogenic bacteria: trafficking harpin, Avr proteins, and death. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5655–5662. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5655-5662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaoui A, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. MxiJ, a lipoprotein involved in secretion of Shigella Ipa invasins, is homologous to YscJ, a secretion factor of the Yersinia Yop proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7661–7669. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7661-7669.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck E, Ludwig G, Auerswald E A, Reiss B, Schaller H. Nucleotide sequence and exact localization of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene from transposon Tn5. Gene. 1982;19:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitter W, Koster M, Latijnhouwers M, de Cock H, Tommassen J. Formation of oligomeric rings by XcpQ and PilQ, which are involved in protein transport across the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:209–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogdanove A J, Beer S V, Bonas U, Boucher C A, Collmer A, Coplin D L, Cornelis G R, Huang H-C, Hutcheson S W, Panopoulos N J, Van Gijsegem F. Unified nomenclature for broadly conserved hrp genes of phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:681–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5731077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charkowski A O, Huang H-C, Collmer A. Altered localization of HrpZ in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae hrp mutants suggests that different components of the type III secretion pathway control protein translocation across the inner and outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;179:3866–3874. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3866-3874.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelis P, Sierra J C, Lim A, Jr, Malur A, Tungpradabkul S, Tazka H, Leitao A, Martins C V, di Perna C, Brys L, De Baetseilier P, Hamers R. Development of new cloning vectors for the production of immunogenic outer membrane fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1996;14:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nbt0296-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crago A M, Koronakis V. Salmonella InvG forms a ring-like multimer that requires the InvH lipoprotein for outer membrane localization. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:47–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancock R E W, Nikaido H. Outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. XIX. Isolation from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and use in reconstitution and definition of the permeability barrier. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:381–390. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.1.381-390.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardie K R, Lory S, Pugsley A P. Insertion of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli requires a chaperone-like protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:978–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiemstra H, De Hoop M, Inouye M, Witholt B. Induction kinetics and cell surface distribution of Escherichia coli lipoprotein under lac promoter control. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:140–151. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.140-151.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H-C, Hutcheson S W, Collmer A. Characterization of the hrp cluster from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 and TnphoA tagging of genes encoding exported or membrane-spanning hrp proteins. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H-C, He S-Y, Bauer D W, Collmer A. The Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 hrpH product, an envelope protein required for elicitation of the hypersensitive response in plants. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6878–6885. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6878-6885.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H-C, Lin R-W, Chang C-J, Collmer A, Deng W-L. The complete hrp gene cluster of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 includes two blocks of genes required for harpinPss secretion that are arranged colinearly with Yersinia ysc homologues. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:733–746. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hueck C J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh T V, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz B J. Bacterial blight of soybean: regulation of a pathogen gene determining host cultivar specificity. Science. 1989;245:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.2781284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klement Z. Hypersensitivity. In: Mount M S, Lacy G H, editors. Phytopathogenic prokaryotes. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koster N, Bitter W, de Cook H, Allaoui A, Cornelis G R, Tommassen J. The outer membrane component, YscC, of the Yop secretion machinery of Yersinia enterocolitica forms a ring-shaped multimeric complex. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:789–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6141981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubori T, Matsushima Y, Nakamura D, Uralil J, Lara-Tejero M, Sukhan A, Galan J E, Aizawa S-I. Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science. 1998;280:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linderoth N A, Model P, Russel M. Essential role of a sodium dodecyl sulfate-resistant protein IV multimer in assembly-export of filamentous phage. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1962–1970. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1962-1970.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linderoth N A, Simon M N, Russel M. The filamentous phage pIV multimer visualized by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Science. 1997;278:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindgren P B. The role of hrp genes during plant-bacterial interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1997;35:129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lughtenberg B, Van Alphen L. Molecular architecture and functioning of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;737:51–115. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(83)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michiels T, Vanooteghem J-C, de Rouvroit C L, China B, Gustin A, Boudry P, Cornelis G R. Analysis of virC, an operon involved in the secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4994–5009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.4994-5009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osborn M J, Gander J E, Parisi E, Carson J. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3962–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osborn M J, Munson R. Separation of the inner (cytoplasmic) and outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1974;166:642–653. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preston G, Deng W-L, Huang H-C, Collmer A. Negative regulation of hrp genes in Pseudomonas syringae by HrpV. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4532–4537. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4532-4537.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnaitman C A. Effect of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, Triton X-100, and lysozyme on the morphology and chemical composition of isolated cell walls of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:553–563. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.553-563.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnaitman C A. Solubilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli by Triton X-100. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:545–552. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.545-552.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tommassen J. Biogenesis and membrane topology of outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wengelnik K, Marie C, Russel M, Bonas U. Expression and localization of HrpA1, a protein of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria essential for pathogenicity and induction of the hypersensitive reaction. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1061–1069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1061-1069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]