Abstract

There has been an alarming rise in human monkeypox cases during these past few months in countries where the disease is not endemic. The recent COVID-19 pandemic and the connection of the monkeypox virus with the smallpox-causing variola virus makes it highly likely to be a candidate for another human health emergency. The transmission mode is predominantly via sexual contact, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM); anogenital lesions are the most typical presentation. Although it is a disease with a self-limiting course, some patients require admission for severe anorectal pain, pharyngitis, eye lesions, kidney injury, myocarditis, or soft tissue superinfections. Antiviral therapy has been advocated, of which tecovirimat is promising in patients with comorbidities. Vaccines will be the mainstay for the present and future control of the disease.

Introduction

When the world is grappling with the mutant SARS-CoV-19, the multicontinental emergence of hitherto endemic monkeypox in human beings is of concern. This is important, considering the virus is related to the ominous, often fatal variola virus. Since the global eradication of smallpox and the subsequent cessation of its vaccination program in 1970, the cross-immunity against monkeypox has been slowly waning in the world community. The new generation is devoid of this vital protection. In this scenario, any change in the behavior and virulence of the monkeypox virus may increase its infectivity and lethal potential. A high degree of suspicion in its prompt diagnosis, isolation of the patient, a thorough screening of the contacts, and other preventive measures are urgent needs. Additional measures, including its effective specific therapy and vaccine development, are significant in preventing the poxvirus disease.

Epidemiology

Since the discovery of the monkeypox virus and its isolation from Cynomolgus monkeys in Copenhagen in 1958, this poxvirus infection has remained a zoonosis,1 being chiefly confined to African countries. The first human infection due to the monkeypox virus was recorded in a child in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970. Soon, it was followed by other sporadic cases from Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone.2, 3, 4, 5 Since then, human monkeypox infection was occasionally reported in African countries for the next few decades (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 ) (Table 1 ). Unfortunately, there are an alarming number of human monkeypox cases now reported from non-African countries.

Fig. 1.

A 7-year-old girl with monkeypox from Equateur Region, Zaire. Front view, during day 8 of rash.

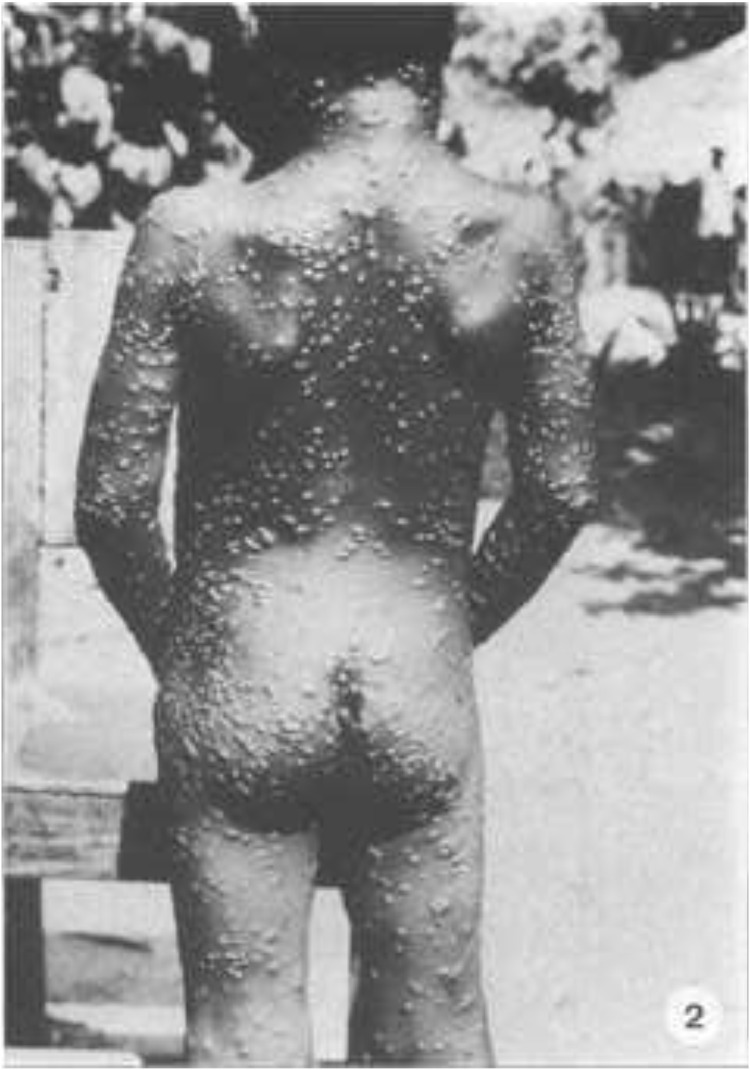

Fig. 2.

Rear view.

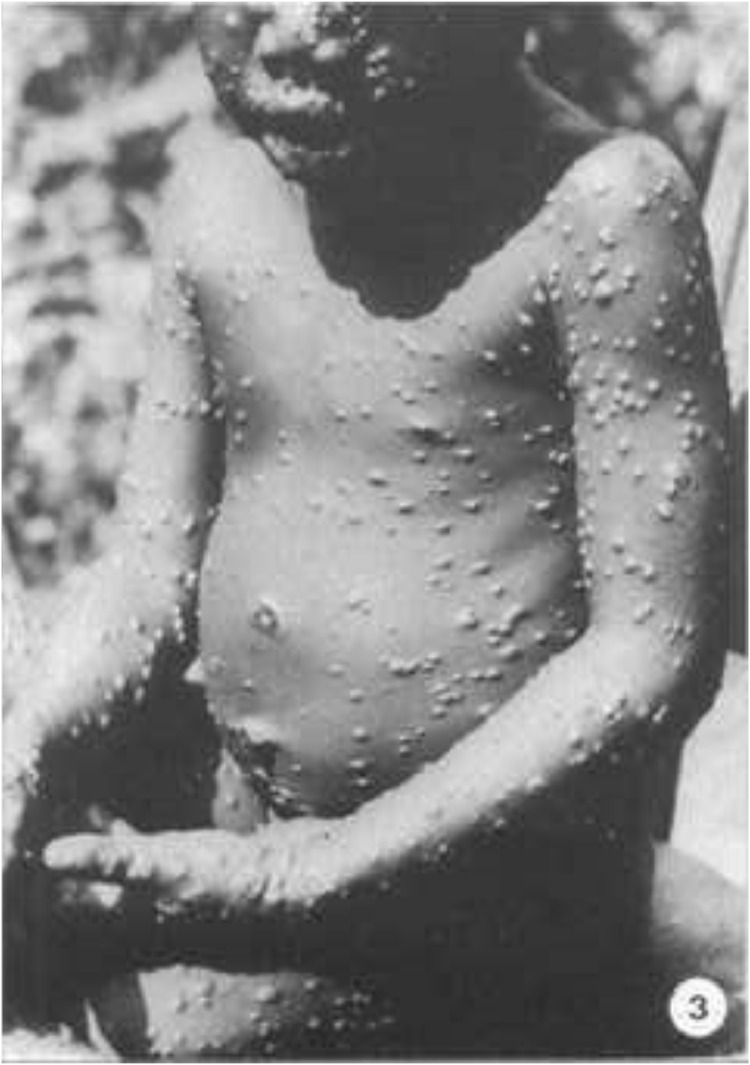

Fig. 3.

The old scar on the arm is not due to vaccination.5

Fig. 4.

Heavy concentration of lesions on the hands, inguinal lymphadenopathy, and pustules on genitalia.5

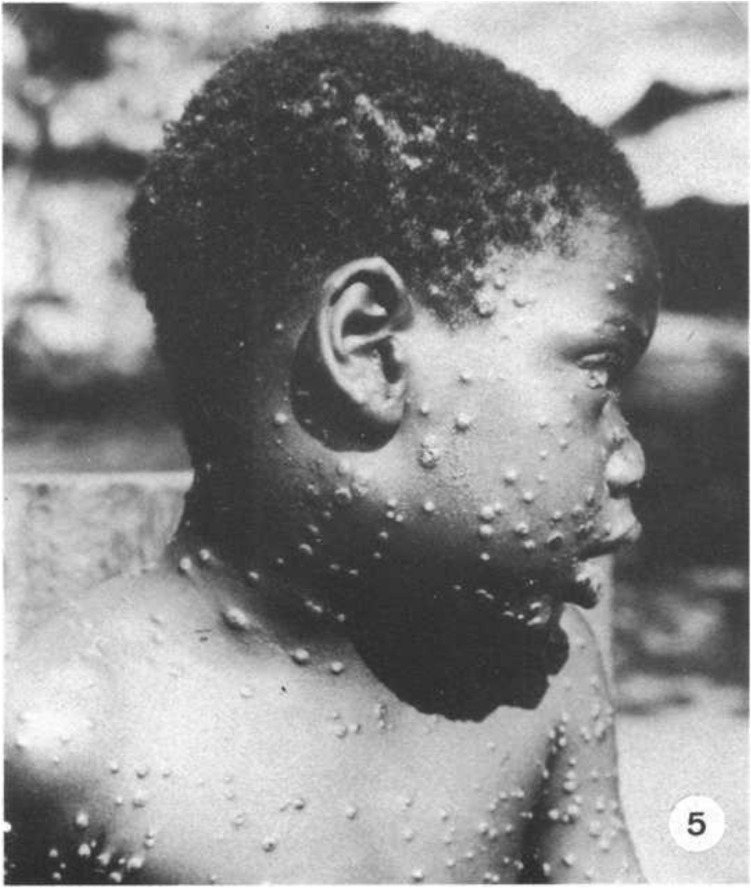

Fig. 5.

Swollen lower face and neck due to cervical and submandibular lymphadenopathy.5

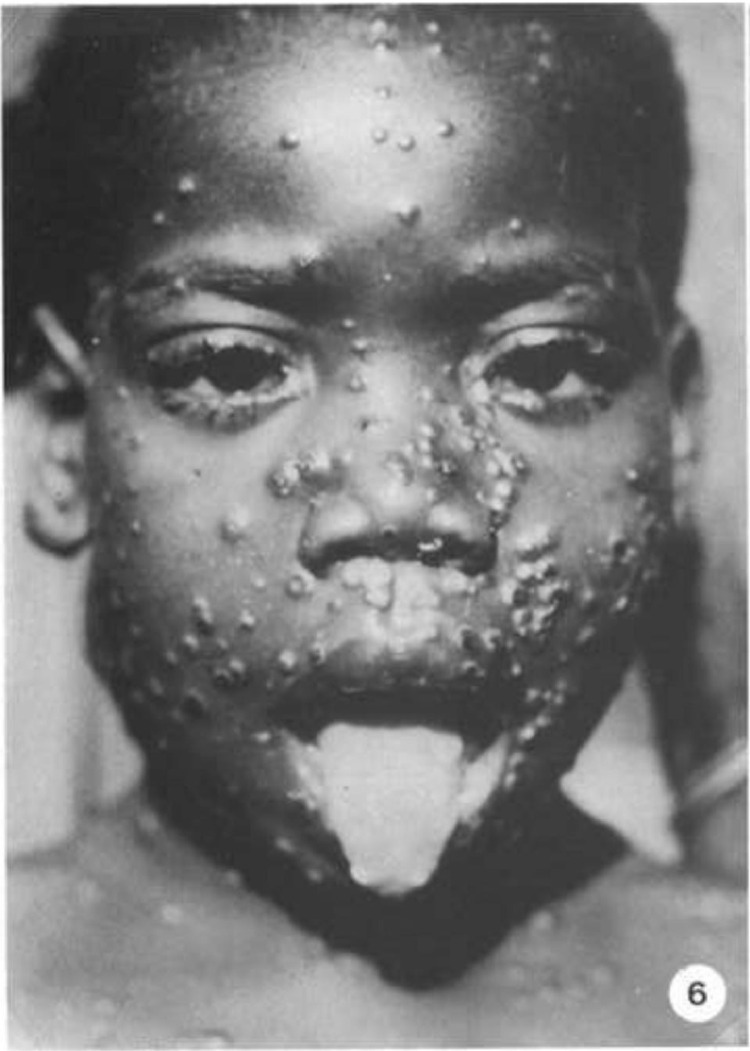

Fig. 6.

Lesions on lips, tongue, and eyelids.

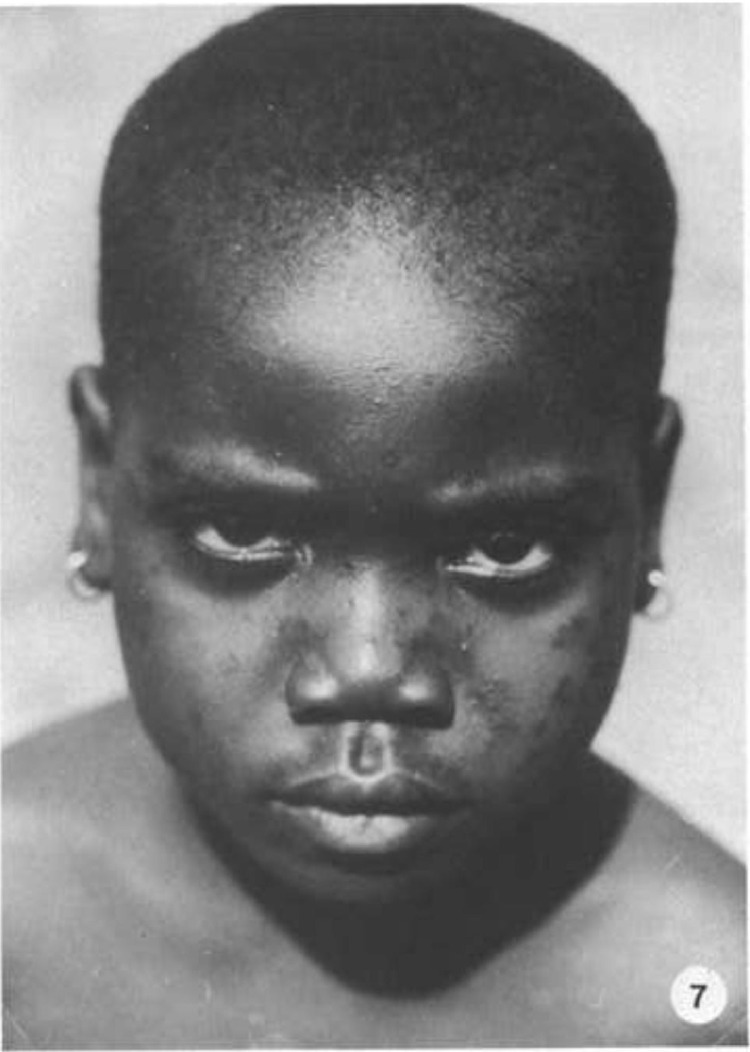

Fig. 7.

Same patient, 16 months after the initial illness. Hyperpigmentation of lesions with shallow pitting scars, most prominent over the bridge of the nose.5

Table 1.

Laboratory confirmed human monkeypox cases.6

| Year | Duration | Number of cases |

|---|---|---|

| 1970-2000 | 30 y | <1000 |

| 2000-2009 | 10 y | >10,000 |

| 2010-2019 | 10 y | >8000 |

| 2020-April 2022 | 2 y 4 mo | 10,545 |

| May 2022-July 2022 | 3 mo | >16,000 |

The first outbreak of human monkeypox was reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 20037, followed by the South Sudan in 2005.8 Then there was a lull in human monkeypox infections. Similarly, in Nigeria, several cases were reported from 2017 onward, after the first reported case 39 years ago.9 Outside of Africa, the Midwest states of the United States recorded 47 cases in 2003, when Gambian pouch rats were imported as exotic pets from Ghana.10 Soon after, isolated cases from the United Kingdom, Israel, and Singapore were reported.11

Beginning on May 7, 2022, a sudden emergence of human monkeypox was reported from 31 countries outside the normal monkeypox endemic cases and has increased exponentially to date.12 On June 22, 2022, the World Health Network (WHN) declared the current monkeypox outbreak a pandemic after confirming 3,417 monkeypox cases across 58 countries and rapidly expanding across multiple continents.13

A significant feature of these patients indicates that they are chiefly men who have sex with men (MSM) and live in urban areas.14 Fortunately, the mortality rates are low, permitting ample time for research about the recent behavior of this endemic zoonotic disease.

The agent

The monkeypox virus (MPV) is a large (200-250 nanometers), brick-shaped, linear double-stranded DNA virus enveloped with lipoproteins and belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family. This genus has more than 10 member species that are genetically and antigenically related (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Poxvirus group members.15

| Species | Infection |

|---|---|

| Variola-vaccinia viruses | Variola major (smallpox)Variola minorVacciniaCowpoxMonkeypoxRabbitpoxBuffalopox |

| Orf-like viruses | Milker's nodulesContagious pustular dermatitis (Orf)Bovine papular stomatitis |

| Avian poxviruses | Canarypox Fowlpox Pigeonpox Turkeypox |

| Myxoma-fibroma viruses | Rabbit myxoma Rabbit fibroma Squirrel fibroma Hare fibroma |

| Unclassified | Molluscum contagiosum Entomopox |

The immunity against one species cross-protects against all other species of this genus. MPV is divided into two genetically distinct clades (Table 3 ). The human MPV infections outside Africa have been caused by the West African clade, as confirmed by PCR and genetic sequencing.17

Table 3.

| Strains | Virulence | Human case fatality |

|---|---|---|

| The Congo Basin clade (Central African) | High | 10.6% |

| The West African clade | Low | 3.6% |

Transmission is via contact with infected animals, their body fluids, lesion materials, and respiratory droplets. Human-to-human transmission can occur through prolonged close contact. Sexual transmission among humans is another possibility, as the current outbreak chiefly involves MSM. The risk factors include non-smallpox-vaccinated patients, people with comorbidities including HIV, and occupational workers dealing with infected animals or humans.18

Clinical features

After an incubation period ranging from 7 to 21 days (mean: 13 days), the human monkeypox infection exhibits a brief prodromal stage, followed by a characteristic eruption. Prodromal features include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The dermatitis is monomorphic, being in the same stage of development, starting with macules, then papules, vesicles, and finally pustules6 , 19, 20, 21, 22 (Figure 8 ). In a week or so, the pustules crust and peel off23 (Figure 9 ) (Table 4 ). The Congo Basic clade is associated with a more severe illness and a higher mortality rate than the West African clade, especially if there is a comorbidity, including HIV9.

Fig. 8.

(A) Oral lesions (right tonsil) visible already at the patient's first presentation. (B-D) Both patients developed 10 to 12 initially vesicular, later pustular skin lesions distributed over the entire body. Many of these lesions were umbilicated, and all were at the same general stage of development. The typical septate structure of pox lesions became apparent upon opening the lesions.22

Fig. 9.

Photographs of the penile ulcer and the skin lesions. Non-tender ulcer on the dorsum of the penile shaft, measuring 7 mm in diameter with central umbilication. Erythematous, maculopapular lesions appeared on the upper back and proceeded down the body. The red-colored line indicates the period of fever (≥37.5°C).23

Table 4.

| Stage | Infectivity | Clinical features | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation period | Noninfectious | Asymptomatic | 7-21 d(Mean: 13 d) |

| Prodrome | Infectious | • Fever• Lymphadenopathy:Periauricular, cervical,axillary, and inguinal• Myalgia• Fatigue | 1-3 d |

| Prodrome | Infectious | • Fever • Lymphadenopathy: Periauricular, cervical, axillary, and inguinal. • Myalgia • Fatigue |

1-3 d |

| Infectious | |||

| Infectious | |||

| Non-infectious |

The recent human MPV infection outbreak has been observed across 16 countries outside the endemic African region.27 There have been several clinical digressions from the conventional infection, including a single genital lesion presentation and a significant rectal/mucosal affliction (Table 5 ). Out of 528 total patients, 70 required hospital admission: 21 for management for severe anorectal pain, 18 for soft tissue superinfection, 13 for infection control purposes, 5 for severe pharyngitis, and 2 for eye lesions, kidney injury, and myocarditis. No death was reported. A July 20, 2022 communication of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) has recorded five deaths in African nations among 14,000 worldwide cases of recent human MPV infection.28

Table 5.

Salient characteristics of the current human MPV outbreak (n = 528).27

| Parameter | Features |

|---|---|

| Sex | Exclusively men (men = 527, trans/nonbinary = 1) |

| Sex orientation | Homosexual = 509 (96%), heterosexual = 9 (2%), bisexual = 10 (2%) |

| HIV status | HIV positive = 218 (41%) |

| Concomitant STI | Present in 109 (29%) patients among 377 (screened) |

| Suspected route oftransmission | Sexual close contact = 504 (95%), nonsexual close contact = 4 (1%),household/unknown = 20 (4%) |

| Clinical features | Dermatitis = 500 (95%), fever = 330 (62%), lymphadenopathy = 295 (56%), lethargy = 216 (41%), myalgia = 165 (31%), headache = 145 (27%), pharyngitis = 113 (21%), anorectal pain/proctitis = 75 (14%) |

| Site of skin lesions | Anogenital region = 383 (73%), trunk and extremities = 292 (55%), face = 134 (25%), palm and soles = 51 (10%) |

| Characters of skin lesions (n = 500) |

Dermatitis (vesicular = 291, macular = 19) = 310 (62%), single ulcer = 54 (11%), multiple ulcers = 95 (19%) |

| Mucosal lesions (n = 217) | Only anogenital regions = 148 (68%), only oropharyngeal region = 50(23%), both anogenital and oropharyngeal regions = 16 (7%), nasal/eyes = 3 |

| Site of positive viralPCR | Anogenital region/skin = 512 (97%), nose/throat swab = 138 (26%),blood = 35 (7%), semen = 29 (5%), urine = 14 (3%) |

Transmission in children can occur through feeding, holding, cuddling, and fomites, as well as from toys.29 , 30 The recent monkeypox affliction of two children in the United States is concerning. Both have received antiviral therapy, recommended by the CDC, as children under 8 years of age are considered at a higher risk.30 , 31

Diagnosis

Monkeypox infection can be confirmed through using PCR for monkeypox DNA from the patient's specimen. Orthopoxviruses in the specimen can be visualized using electron microscopy; viral culture isolation can also be undertaken. Immunohistochemical staining for Orthopox viral antigens, serum studies for anti-Orthopoxvirus IgM (for recent infection), and anti-Orthopoxvirus IgG (for prior exposure/vaccination) are other important laboratory studies.32

The differential diagnoses include chickenpox, measles, secondary syphilis, hand-foot-mouth disease, and infectious mononucleosis. Genital human monkeypox can be confused with chancroid, donovanosis, and other nonvenereal genital ulcers.24 , 32

Management

There is no specific clinically-proven therapy for monkeypox disease. Tecovirimat (S.T.-246 and Brincidofovir are the two antiviral preparations approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox. Their use in human monkeypox has insufficient data but suggests that Tecovirimat is more effective than Brincidofovir.33

The preventive measures include isolation of the patient, keeping lesions covered, proper, and disposing of infectious materials with appropriate precautions. Contact tracing and monitoring for a reasonable duration will assist in controlling the spread of the disease.25 , 33

A concerted two-decade effort of the United States government to develop antivirals and next-generation vaccines against smallpox resulted in two FDA-approved antivirals and two next-generation vaccines (Table 6).

-

1.

The first next-generation smallpox vaccine called ACAM-2000 is similar to the discontinued Dryvax vaccine, known to generate long-lasting immunity34 , 35 and provides 85% protection against human monkeypox.36

-

2.

The second next-generation smallpox vaccine is MVA-BN (JYNNEOS in the United States), manufactured with the Modified Vaccinia Ankara strain and administered by two subcutaneous injections, 4 weeks apart.37 While the former vaccine is contraindicated in pregnancy, atopic dermatitis, and various immune deficiencies, the latter displayed no serious adverse events and no risk of inadvertent inoculation and auto-inoculation.6 , 18 , 37 The MVA-BN vaccine is approved in the United States for use against both smallpox and monkeypox. Tt still requires clinical trials for human efficacy.37

Table 6.

| Mode | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Prevention | By prior immunization with available smallpox vaccines |

| 1. JYNNEOS™ (MVA-BN, IMAVAMUNE, IMVANEX) | |

| 2. ACAM 2000® | |

| 3. Newer APSV (Avantis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine) | |

| Prophylaxis | 1. Pre-exposure: Vaccinating select people at risk for occupational exposure. |

| 2. Post-exposure: Vaccination within 4 d of exposure to the virus to prevent or minimize the development of the disease. | |

| Antiviral therapy | 1. Tecovirimat: (oral or intravenous) Adults 600 mg, twice daily; children 13-25 kg 200 mg, twice daily; children 25-40 kg, 400 mg twice daily. The duration of treatment is 14 d. |

| 2. Brincidofovir: (Oral suspension) Adults (>48 kg) 200 mg, once weekly for two doses; children (>10 kg) 4 mg/kg, once weekly for two doses. | |

| 3. Cidofovir: (Intravenous) 5 mg/kg, once weekly for 2 wk, followed by 5 mg/kg, once every other week. | |

| 4. Vaccinia immune globulins (intravenous): 6000 U/kg as soon as Symptoms appear. Repeat dose required based on response to Treatment and severity of symptoms. |

Among 528 human monkeypox patients in one report.27 23 (5%) were given antiviral therapy or vaccinia immune globulin with a favorable response. Tecovirimat (TPOXX or ST246) inhibits the spread of the virus by inhibiting the viral envelope protein VP37, thus blocking the final steps in the viral maturation and its release from infected cells.

The CDC-held Emergency Access Investigational New Protocol allows the use of Tecovirimat for non-variola orthopoxvirus infections such as monkeypox. The protocol also includes an allowance for opening an oral capsule and mixing its contents with liquid or soft food for pediatric patients weighing less than 13 kg. Cidofovir and Brincidofovir work by inhibiting viral DNA polymerase, the latter being more effective in controlling MPV infection.38

Conclusions

During the last 2 years, scientists, health care personnel, and world authorities have coordinated, promptly combating, and curtailing any future epidemic or pandemic. Our preventive strategy can allay apprehensions, anxiety, morbidity, mortality, and resources. Instead of an alarm, a rational scientific approach can help halt the spread from infected areas to other noninfected safe zones.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.von Magnus P, Anderson EK, Peterson KB. Birch-Anderson A. A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1959;46:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marennikova SS, Seluhina EM, Mal'ceva NN, Cimiskjan KL, Macevic GR. Isolation and properties of the causal agent of a new variola-like disease (monkeypox) in man. Bull World Health Org. 1972;46:599–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lady ID, Ziegler P, Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Org. 1972;46:593–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster SO, Brink EW, Hutchins DL, et al. Human monkeypox. Bull World Health Org. 1972;46:569–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breman JG, Kalisa-Ruti Steniowski MV, Zanotto E, Gromyko AI, Arita I. Human monkeypox, 1970-79. Bull World Health Org. 1980;58:165–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Y, White A. Monkeypox virus emerges from the shadow of its more infamous cousin: family biology matters. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:1768–1777. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2095309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Learned LA, Reynolds MG, Wassa DW, et al. Extended interhuman transmission of monkeypox in a hospital community in the Republic of the Congo, 2003. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:428–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Formenty P, Muntasir MO, Damon I, et al. Human monkeypox outbreak caused by novel virus belonging to Congo Basin clade, Sudan, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1539–1545. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.100713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhart M, et al. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017-18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:872–879. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the western hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauldin MR, McCollum AM, Nakazawa YJ, et al. Exportation of monkeypox virus from the African continent. J Infect Dis. 2022;225:1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathieu E, Dattani S, Ritchie H, et al. Monkeypox. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox, accessed on 27 July 2022.

- 13.World Health Network. The World Health Network declares monkeypox a pandemic - press release. Available at: https://www.worldhealthnetwork.global/monkeypoxpressrelease, accessed on 27 July 2022.

- 14.Vivancos R, Anderson C, Blomquist P, et al. Community transmission of monkeypox in the United Kingdom, April to May 2022. Eurosurveillance. 2022;27 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho CT, Wenner HA. Monkeypox virus. Bacteriol Rev. 1973;37:1–18. doi: 10.1128/br.37.1.1-18.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox: a potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson K, Heymann D, Brown CS, et al. Human monkeypox: after 40 years, an unintended consequence of smallpox eradication. Vaccine. 2020;38:5077–5081. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heskin J, Belfield A, Milne C, et al. Transmission of monkeypox virus through sexual contact – a novel route of infection. J Infect. 2022;85:334–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bragazzi NL, Kong JD, Mahroum N, et al. Epidemiological trends and clinical features of the ongoing monkeypox epidemic: a preliminary pooled data analysis and literature review. J Med Virol. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27931, accessed on 27 July 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Guidelines for management of monkeypox disease. Available at:https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Guidelines%20for%20Management%20of%20Monkeypox%20Disease.pdf. Accessed on 27 July 2022.

- 21.Moore M, Zahra F. StatPearls; Treasure Island, FL: 2022. Monkeypox. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noe S, Zange S, Seilmaier M, et al. Clinical and virological features of first human monkeypox cases in Germany. Infection. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01874-z, acceesed on 27 July 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jang YR, Lee M, Shin H, et al. The first case of monkeypox in the Republic of Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e224. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ongoing D, Iroezindu M, James HI, et al. Clinical course and outcome of human monkeypox in Nigeria. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:e210–e214. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehouse ER, Bonwitt J, Hughes CM, et al. Clinical and epidemiological findings from enhanced monkeypox surveillance in Tshuapa province, Democratic Republic of the Congo during 2011-2015. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1870–1878. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries. N Engl J Med. April-June 2022 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. accessed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soucheray S. WHO: 14,000 monkeypox cases worldwide, 5 deaths. Available at: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2022/07/who-14000-monkeypox-cases-worldwide-5-deaths. Accessed on 30 July 2022.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC and health partners responding to Monkeypox Case in the U.S. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/s0518-monkeypox-case.html. Accessed on 30 July 2022.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What clinicians need to know about monkeypox in the United States and other countries. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2022/callinfo_052422.asp. Accessed on 30 July 2022.

- 31.Crist C. Two children in U.S. diagnosed with monkeypox. Available at: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/news/20220725/two-children-us-diagnosed-monkeypox. Accessed on 30 July 2022.

- 32.McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the U.K. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, et al. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat Med. 2003;9:1131–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crotty S, Felgner P, Davies H, et al. Cutting edge: long-term B cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J Immunol. 2003;171:4969–4973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fine PE, Jezek Z, Grab B, et al. The transmission potential of monkeypox virus in human populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:643–650. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for pre-exposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734–742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7122e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forth DN, Rizk Y. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957–963. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01742-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. ACAM2000, (Smallpox (Vaccinia) Vaccine, Live)Lyophilized preparation for percutaneous scarification. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/75792/download.

- 40.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. TPOXX (tecovirimat) capsules for oral use. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208627s000lbl.pdf.

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smallpox vaccines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html. Accessed July 27, 2022.