Abstract

The Ophiostomatales was erected in 1980. Since that time, several of the genera have been redefined and others have been described. There are currently 14 accepted genera in the Order. They include species that are the causal agents of plant and human diseases and common associates of insects such as bark beetles. Well known examples include the Dutch elm disease fungi and the causal agents of sporotrichosis in humans and animals. The taxonomy of the Ophiostomatales was confused for many years, mainly due to the convergent evolution of morphological characters used to delimit unrelated fungal taxa. The emergence of DNA-based methods has resolved much of this confusion. However, the delineation of some genera and the placement of various species and smaller lineages remains inconclusive. In this study we reconsidered the generic boundaries within the Ophiostomatales. A phylogenomic framework constructed from genome-wide sequence data for 31 species representing the major genera in the Order was used as a guide to delineate genera. This framework also informed our choice of the best markers from the currently most commonly used gene regions for taxonomic studies of these fungi. DNA was amplified and sequenced for more than 200 species, representing all lineages in the Order. We constructed phylogenetic trees based on the different gene regions and assembled a concatenated data set utilising a suite of phylogenetic analyses. The results supported and confirmed the delineation of nine of the 14 currently accepted genera, i.e. Aureovirgo, Ceratocystiopsis, Esteya, Fragosphaeria, Graphilbum, Hawksworthiomyces, Ophiostoma, Raffaelea and Sporothrix. The two most recently described genera, Chrysosphaeria and Intubia, were not included in the multi-locus analyses. This was due to their high sequence divergence, which was shown to result in ambiguous taxonomic placement, even though the results of phylogenomic analysis supported their inclusion in the Ophiostomatales. In addition to the currently accepted genera in the Ophiostomatales, well-supported lineages emerged that were distinct from those genera. These are described as novel genera. Two lineages included the type species of Grosmannia and Dryadomyces and these genera are thus reinstated and their circumscriptions redefined. The descriptions of all genera in the Ophiostomatales were standardised and refined where this was required and 39 new combinations have been provided for species in the newly emerging genera and one new combination has been provided for Sporothrix. The placement of Afroraffaelea could not be confirmed using the available data and the genus has been treated as incertae sedis in the Ophiostomatales. Paleoambrosia was not included in this study, due to the absence of living material available for this monotypic fossil genus. Overall, this study has provided the most comprehensive and robust phylogenies currently possible for the Ophiostomatales. It has also clarified several unresolved One Fungus-One Name nomenclatural issues relevant to the Order.

Taxonomic novelties: New genera: Harringtonia Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Heinzbutinia Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Jamesreidia Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Masuyamyces Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter. New species: Masuyamyces massonianae M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer. New combinations: Dryadomyces montetyi (M. Morelet) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Dryadomyces quercivorus (Kubono & Shin. Ito) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Dryadomyces quercus-mongolicae (K.H. Kim et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Dryadomyces sulphureus (L.R. Batra) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Graphilbum pusillum (Masuya) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia abieticolens (K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia altior (Paciura et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia betulae (Jankowiak et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia curviconidia (Paciura et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia euphyes (K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia fenglinhensis (R. Chang et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia gestamen (de Errasti & Z.W. de Beer) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia innermongolica (X.W. Liu et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia pistaciae (Paciura et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia pruni (Masuya & M.J. Wingf.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia taigensis (Linnak. et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Grosmannia trypodendri (Jankowiak et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Harringtonia aguacate (D.R. Simmons et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Harringtonia brunnea (L.R. Batra) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Harringtonia lauricola (T.C. Harr. et al.) Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Heinzbutinia grandicarpa (Kowalski & Butin) Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Heinzbutinia microspora (Arx) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Heinzbutinia solheimii (B. Strzałka & Jankowiak) Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Jamesreidia coronata (Olchow. & J. Reid) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Jamesreidia nigricarpa (R.W. Davidson) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Jamesreidia rostrocoronata (R.W. Davidson & Eslyn) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Jamesreidia tenella (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Leptographium cainii (Olchow. & J. Reid) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Leptographium europioides (E.F. Wright & Cain) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Leptographium galeiforme (B.K. Bakshi) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Leptographium pseudoeurophioides (Olchow. & J. Reid) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Leptographium radiaticola (J.J. Kim et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces acarorum (R. Chang & Z.W. de Beer) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces ambrosius (B.K. Bakshi) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces botuliformis (Masuya) Z.W. de Beer & M. Procter, Masuyamyces jilinensis (R. Chang et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces lotiformis (Z. Wang & Q. Lu) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces pallidulus (Linnak. et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Masuyamyces saponiodorus (Linnak. et al.) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer, Sporothrix longicollis (Massee & E.S. Salmon) M. Procter & Z.W. de Beer.

Citation: de Beer W, Procter M, Wingfield MJ, Marincowitz S, Duong TA (2022). Generic boundaries in the Ophiostomatales reconsidered and revised. Studies in Mycology 101: 57–120. doi: 10.3114/sim.2022.101.02

Keywords: Generic boundaries, new taxa, nomenclature, Ophiostomataceae, Ophiostomatales, Sordariomycetidae, taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

The Ophiostomatales (Sordariomycetidae, Ascomycota), was described by Benny & Kimbrough (1980) accommodating the single family Ophiostomataceae. The Order includes species that are the causal agents of plant and human diseases as well as common associates of wood infesting insects such as bark beetles (Wingfield et al. 1993, Seifert et al. 2013). Well known examples are the Dutch elm disease fungi and the causal agents of sporotrichosis in humans and animals (Figs 1, 2). As described, this Order originally accommodated four genera, Ophiostoma, Ceratocystiopsis, Sphaeronaemella and Ceratocystis. These authors considered Ceratocystis distinct from Ophiostoma based on cell wall constituents and conidiogenesis (Weijman & De Hoog 1975, Seifert et al. 2013). Upadhyay (1981) treated Ophiostoma as a synonym of Ceratocystis based on morphological similarities such as their long-necked ascocarps that produce sheathed ascospores in sticky droplets to facilitate arthropod dispersal (Upadhyay 1981, Malloch & Blackwell 1993). In the 1990’s, DNA sequence data confirmed that Ophiostoma and Ceratocystis resided in two distinct Orders of the fungi (Hausner et al. 1993c, Spatafora & Blackwell 1994). Ceratocystis has subsequently been shown to represent several morphologically and ecologically distinct genera in the Ceratocystidaceae (Microascales) (De Beer et al. 2013a, 2014, Nel et al. 2018, Mayers et al. 2015, 2020).

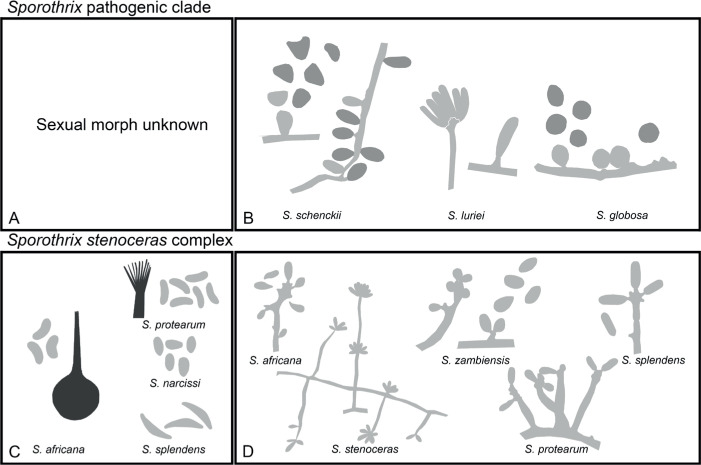

Fig. 1.

Ecological niches in which genera and species residing in the Ophiostomatales are found. A. Ulmus americana street trees dying as a result of Dutch Elm Disease (photo: D.W. French). B. Symptoms of infection by the human pathogen Sporothix schenckii (photo: Prof. Dr Flávio de Queiroz Telles Filho, Federal University of Paraná, Brazil). C. Signage in Yellowstone National Park emphasising the important role that bark beetles (and by extension their fungal symbionts) play in the ecology of conifer ecosystems. D. Blue stain in conifer timber caused by numerous species of Ophiostomatoid fungi. E. Hylobius rhizophagus (root collar weevil) squashed onto the surface of agar medium containing cycloheximide selective for many genera and species of Ophiostomatales and in this case Leptographium procerum. F. Infructescences of a Protea species in which numerous species of Ophiostomatoid fungi can be found. G. Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzesii) trees dying as a result of black stain root disease caused by Leptographium wageneri var. pseudotsugae (Photo: F.W. Cobb). H. Pinus resinosa trees dying as a result of mass infestation by Ips pini and associated Ophiostoma minus.

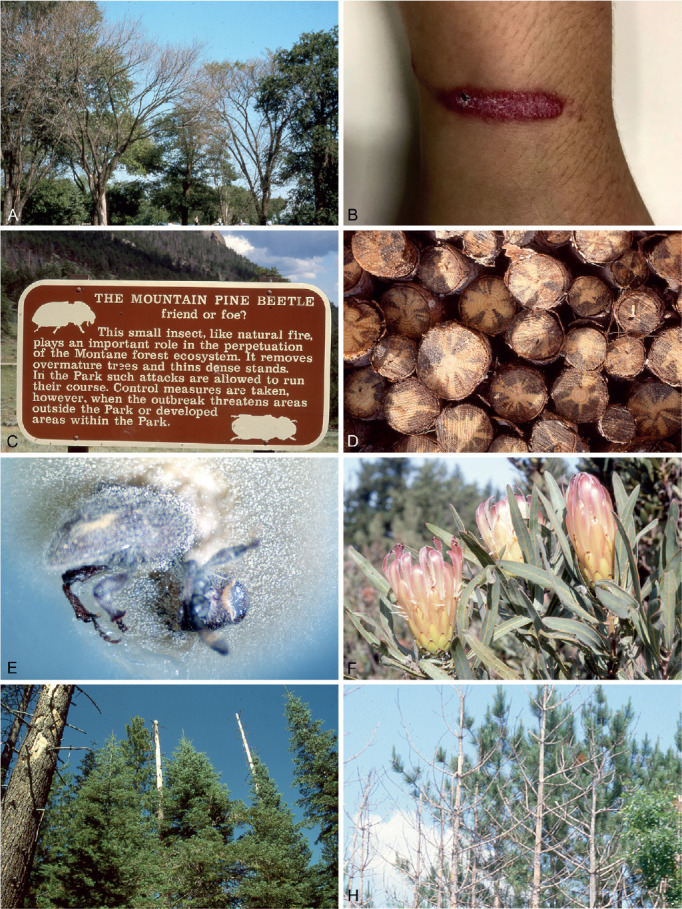

Fig. 2.

Ecological niches of Ophiostomatoid fungi and micrographs providing examples of structures typical of these fungi. A. Transverse stellate gallery systems of Ips schmutzenhoferi in the bark of a Pinus spinulosa tree, showing blue-stain around nuptial chambers and female galleries. B. Section through a Eucalyptus stem infested by the ambrosia beetle Megaplatypus mutatus showing tunnels in which species of Ophiostomatales occur. C, D. Ascomata of Ophiostoma ulmi (C) (photo: D.W. French) and O. pilliferum (D) (photo: Z.W. de Beer) with sticky ascospores masses at their apices, illustrating the manner by which these fungi easily attach to the insects that carry them. E. Conidiophores of Leptographium procerum, illustrating asexual structures well suited to being vectored by insects. F. Conidiogenous cells of a Sporothrix sp. G. Typical single-celled conidia found in most species of Ophiostomatales. H. Many species of Ophiostomatales have ascospores with sheaths such as these pillow-shaped spores in Ophiostoma ips.

The Ophiostomatales as it is currently defined accommodates a single family, the Ophiostomataceae (De Beer et al. 2013a), which was initially described in 1932 (Nannfeldt 1932). At the time, it included Ophiostoma, with Endoconidiophora and Ceratocystis as synonyms (Melin & Nannfeldt 1934). The family was treated in various Orders prior to 1980 (De Beer et al. 2013a). Apparently unaware of Benny & Kimbrough’s (1980) study, Upadhyay (1981) re-defined the Ophiostomataceae with Ceratocystis as type genus, and Ophiostoma, Sphaeronaemella, Grosmannia and Europhium as synonyms, and with Ceratocystiopsis as a distinct new genus. However, the DNA-based distinction between Ceratocystis and Ophiostoma led to their inevitable separation and emended definitions of the Ceratocystidaceae and Ophiostomataceae (Wingfield et al. 1993, Réblová et al. 2011, De Beer et al. 2013a, 2016a).

The first attempt to resolve generic boundaries within the Ophiostomatales subsequent to its separation from the Ceratocystidaceae was made by Zipfel et al. (2006). Based on phylogenies constructed from ribosomal DNA and β-tubulin sequences and including 55 taxa, they recognised Ophiostoma, Ceratocystiopsis and Grosmannia as distinct sexual genera. Following the dual nomenclature system at the time, asexual Sporothrix and Leptographium species retained their names in these genera, although they respectively grouped in Ophiostoma and Grosmannia.

After 20 years of DNA-based taxonomy and in the wake of the abandonment of a dual nomenclature for the fungi (Hawksworth et al. 2011, Hawksworth 2012), De Beer & Wingfield (2013) revised the Ophiostomatales, considering all published ribosomal large subunit (LSU) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, including 266 species. They redefined Ophiostoma sensu stricto, Raffaelea s.s., Ceratocystiopsis, Fragosphaeria and Graphilbum, and recognised 18 species complexes within the various genera of the Ophiostomatales. However, they concluded that the rDNA-based phylogenies were not sufficiently robust to resolve the generic status of the Sporothrix schenckii-Ophiostoma stenoceras species complex, or that of various lineages within what they defined as Leptographium sensu lato. Their phylogenies also suggested that ambrosial species previously treated as Raffaelea did not form a monophyletic group.

After the revision of the Ophiostomatales by De Beer & Wingfield (2013), the majority of studies focused on new species descriptions (Romón et al. 2014a, b, Musvuugwa et al. 2015, 2016, De Errasti et al. 2016, Simmons et al. 2016, Chang et al. 2017, Marincowitz et al. 2017, 2020, etc.) and on resolving issues within species complexes (Ando et al. 2016, Linnakoski et al. 2016, Jankowiak et al. 2017, Yin et al. 2019, 2020, etc.).

De Beer et al. (2016a) reconsidered the status of the S. schenckii-O. stenoceras complex, providing sequences for four gene regions of 65 species with sporothrix-like asexual morphs. They concluded that Sporothrix represented a distinct genus including 51 species and incorporated the characters of the sexual morphs of many of the species, previously treated as Ophiostoma, in the emended definition of Sporothrix. A lineage including some of the remaining sporothrix-like species that did not form part of the newly defined genus were provided with the new genus name, Hawksworthiomyces, in a subsequent paper (De Beer et al. 2016b). In addition, Van der Linde et al. (2016) and Bateman et al. (2017) described Aureovirgo and Afroraffaelea respectively as novel, monotypic genera in the Order. In 2018, a fungus was discovered preserved in amber alongside an ambrosia beetle, leading to the description of Paleoambrosia. The genus was treated in the Ophiostomatales based on morphological characters resembling Raffaelea species (Poinar & Vega 2018). Most recently, Nel et al. (2021) described two new genera, Chrysosphaeria and Intubia, from the abandoned combs of fungus-growing termites (Termitomyces) in South Africa.

In this study, we reconsidered and redefined the unresolved boundaries of genera including Leptographium, Raffaelea and some smaller lineages in the Ophiostomatales. To achieve this goal, we selected four gene regions based on a phylogenomic framework constructed from genome-wide sequence data for representative ophiostomatalean species. Sequence data for these four gene regions were then generated for as many species in the Order as possible, and phylogenetic analyses were conducted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates and DNA extraction

Fungal cultures used in this study were obtained from the Culture Collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, South Africa, and the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS), Utrecht, the Netherlands. Isolates were grown on 2 % malt extract agar (MEA: 20 g malt extract, 20 g agar, 1 L dH2O) at room temperature; initially with streptomycin (0.4 g/L, Sigma-Aldrich, Kempton Park, South Africa) and cycloheximide (0.5 g/L, Sigma-Aldrich, Kempton Park, South Africa) supplemented in the media, then sub-cultured to MEA, and maintained at 4 °C after optimal growth had occurred. DNA was extracted following the protocol described by Duong et al. (2012).

Phylogenomic analyses

Available genome sequences for 31 species representing 11 of 14 currently recognised genera (excluding Afroraffaelea, Aureovirgo and Paleoambrosia) in the Ophiostomatales (Supplementary Table S1) were used to construct a phylogenomic tree. Two species of Diaporthales (Cryphonectria parasitica and Diaporthe ampelina), two species of Magnaporthales (Magnaporthe grisea and Magnaporthe poae), and one species of Togniniales (Phaeoacremonium minimum) were included in the analyses as outgroup taxa. Genome assemblies for all species were subjected to BUSCO v. 4.0.5 (Seppey et al. 2019) runs using the Sordariomycetes_odb10 dataset to obtain BUSCO genes. The amino acid sequences were extracted from BUSCO results and datasets were compiled for each of the BUSCO orthologous groups. All BUSCO orthologous groups with duplicated BUSCO genes were excluded from the analysis. PRANK (Löytynoja 2014) was used to align the datasets with default parameters.

Trimal v. 1.4 (Capella-Gutiérrez et al. 2009) was used for trimming of the alignments with “-resoverlap 0.8 -seqoverlap 75” parameters. Only datasets with lengths equal or larger than 100 aa after trimming step were retained for further analysis. Permutation Tail Probability (PTP) tests were conducted in PAUP v. 4.0a (Swofford 2003) to identify and remove datasets having no phylogenetic signal as well as those with less than 50 parsimony-informative characters. Individual gene trees for each BUSCO orthologous group were constructed using IQ-TREE v. 2 with an optimal substitution model automatically determined and 1 000 ultrafast bootstraps (Hoang et al. 2018, Minh et al. 2020). TreeShrink v. 1.3.7 (Mai & Mirarab 2018) was used to remove outliers (taxa with abnormal branch length) from all trees with default parameters. Newick utilities (Junier & Zdobnov 2010) was used to collapse branches with less than 10 % bootstrap support. A species tree was then constructed from the final set of trees under the multi-species coalescent model using ASTRAL v. 5.7.7 (Mirarab et al. 2014). Branch length of the species tree was optimized with RAxML v. 8.2.11 (Stamatakis 2014) using only BUSCO orthogroups that have all 36 taxa present and without any outliner taxon as identified with TreeShrink analysis.

Selection of gene regions for phylogenetic analyses

Sequences for eight gene regions commonly used in phylogenetic studies of the fungi were extracted from 31 draft genome sequences for species in the Ophiostomatales, as well as from those used as outgroups in the phylogenomic analysis (Supplementary Table S1). These included β-tubulin (β-tub), translation elongation factor 1 alpha (TEF-1α), internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), ribosomal large subunit (LSU), mini chromosome maintenance protein complex 7 (MCM7), DNA-directed RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPBII), DNA-directed RNA polymerase II largest subunit (RPBI) and ribosomal small subunit (SSU). A phylogenetic tree was constructed for each of these datasets using IQ-TREE v. 2 as indicated above. Based on the level of congruency between individual gene trees and the phylogenomic tree as well as the phylogenetic signal of these gene regions, the LSU, ITS, TEF-1α and RPBII gene regions were selected as markers to delineate genera in the Ophiostomatales. These regions included the primary (ITS) and secondary (TEF-1α) barcodes for fungi (Schoch et al. 2012, Stielow et al. 2015).

Primer selection

Existing primers were used to amplify and sequence the ITS (ITS1F: Gardes & Bruns 1993, ITS4: White et al. 1990), TEF-1α (EF2F: Marincowitz et al. 2015, EF2R: Jacobs et al. 2004) and LSU (LR5, LROR: Vilgalys & Hester 1990) gene regions. Since previously available primers for RPBII did not consistently amplify the targeted region in most of the isolates investigated, we designed new primers for this gene region based on the available genome sequences: Oph-RPB2F1 (5’ - GAYGAYCGIGAYCAYTTYGG - 3’), Oph-RPB2F2 (5’ - TICTGGCIAARCTNTTCCG - 3’) and Oph-RPB2R1 (5’ - CCCATRGCYTGYTTRCCCAT - 3’). A combination of Oph-RPBF1 and Oph-RPBR1 was used in most instances, while Oph-RPBF2 and Oph-RPBR1 were used in cases where the former combination was not successful.

PCR

For the ITS, TEF-1α and LSU regions, FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase (Roche, Germany) was used. For the RPBII gene region the Platinum® Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) was used. The ITS, LSU and TEF-1α gene regions were amplified following the protocol described by Duong et al. (2012). For the RPBII gene region, the protocol provided with the Platinum® Multiplex PCR Master Mix was used but amended as follows: the PCR mixture was made up to a final volume of 12.5 μL, primers were added to a concentration of 1 μM each, and PCR was carried out with 40 cycles of denaturing at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (1 % agarose) was performed on all PCR products to confirm the success of amplification. PCR products were treated with ExoSAP (a mixture of exonuclease I and alkaline phosphatase; one unit of each enzyme was used for approximately 20 μL of PCR product). The mixture was then subjected to two incubation steps at 37 °C for 15 min (for enzymatic action) and 80 °C for 15 min (to deactivate the enzymes). The treated products were stored at 4 °C until PCR sequencing was carried out.

DNA sequencing

Sanger sequencing was performed for all ExoSAP treated PCR products. The PCR sequencing setup reaction (12 μL) consisted of 6.4 μL dH2O, 2.1 μL 5× sequencing buffer, 0.5 μL BigDye v 3.1, 1 μL of the forward or reverse primer (10 mM), and 2 μL ExoSAP treated PCR product. The reaction was performed under the following conditions: 25 cycles of a denaturing step at 96 °C for 10 s, an annealing step at 55 °C for 5 s, and an elongation step at 60 °C for 4 min. The products were maintained at 4 °C until being used for precipitation.

PCR sequencing products were precipitated using the ethanol/NaOAc precipitation method. For each of the PCR sequencing products (total volume of 12 μL) 8 μL dH2O, 2 μL NaOAc (3 M, pH 5.2) and 50 μL absolute ethanol (EtOH) was added. The tubes were incubated on ice for 10 min, then centrifuged at 13 400 rpm for 30 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet washed twice with 150 μL of 70 % EtOH and centrifuged for 10 min at 13 400 rpm at room temperature. After the final wash, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was air-dried for approximately 15 min. The samples were kept at -20 °C until they could be analysed. The fragment separations were performed using an ABI PRISM® 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Consensus sequences were derived from sequences obtained with forward and reverse primers. All sequences generated in this study have been submitted to GenBank, and those from ex-type isolates will be included in the RefSeq Targeted Loci (RTL) database in GenBank (Schoch et al. 2014).

Phylogenetic analyses

For species with available genome sequences (Supplementary Table S1), gene region data were extracted from assembled genome sequences. Sequences were downloaded from GenBank for newly described species for which cultures were not available during the study period, as well as for species for which our sequence data were incomplete. Datasets were aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh & Stanley 2013) with default parameters. Alignments were refined with an online version of Gblocks v. 0.91b (Castresana 2000) using default parameters – i.e. no alternative options for more or less stringent selection were selected. Datasets for the various gene regions obtained from Gblocks were concatenated using FASconCAT-G (Kück & Meusemann 2010). Partitionfinder v. 2.1.1 (Lanfear et al. 2017) was used to determine best substitution models for the combined dataset.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses using RAxML (Stamatakis 2014) were performed separately for all gene regions and for the concatenated dataset with raxmlGUI v. 1.3 (Silvestro & Michalak 2012) using the GTR+G+I substitution model and 1 000 thorough bootstrap replicates. Bayesian analysis was conducted using PhyloBayes-MPI v. 1.8 (Lartillot et al. 2013); two chains were run in parallel under the CAT-GTR model. The program bpcomp was used to assess the convergence in tree space. Runs were terminated when the maxdiff value obtained between two chains reached 0.1 or lower.

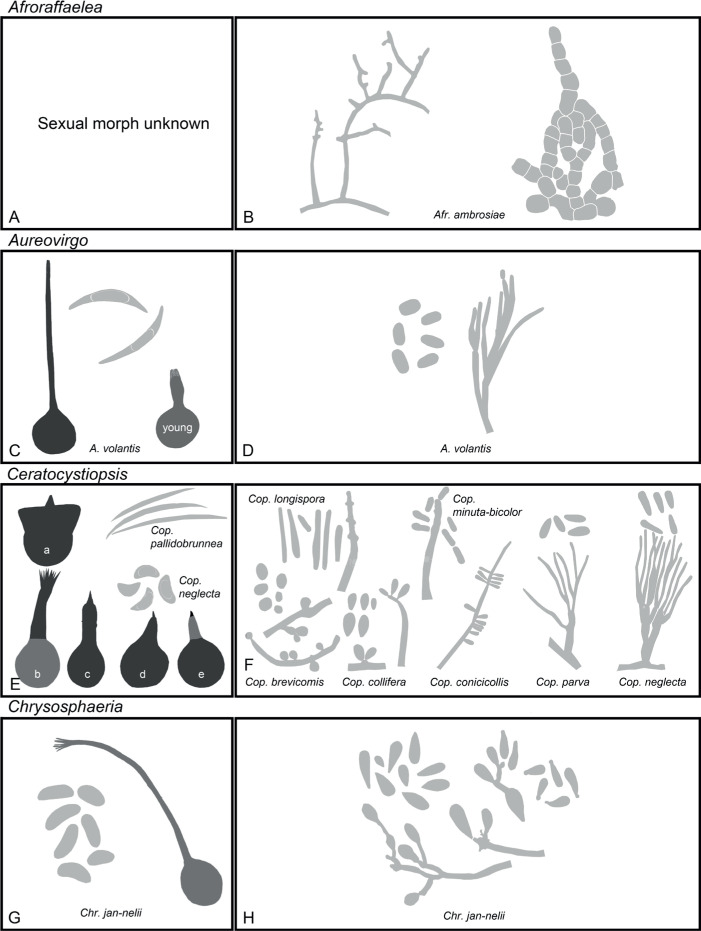

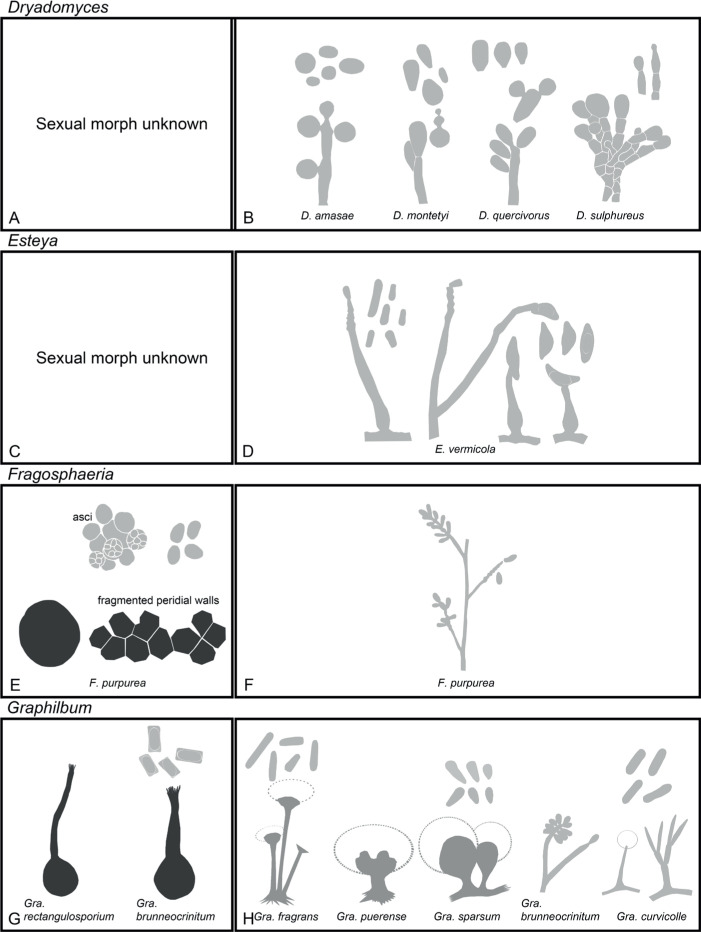

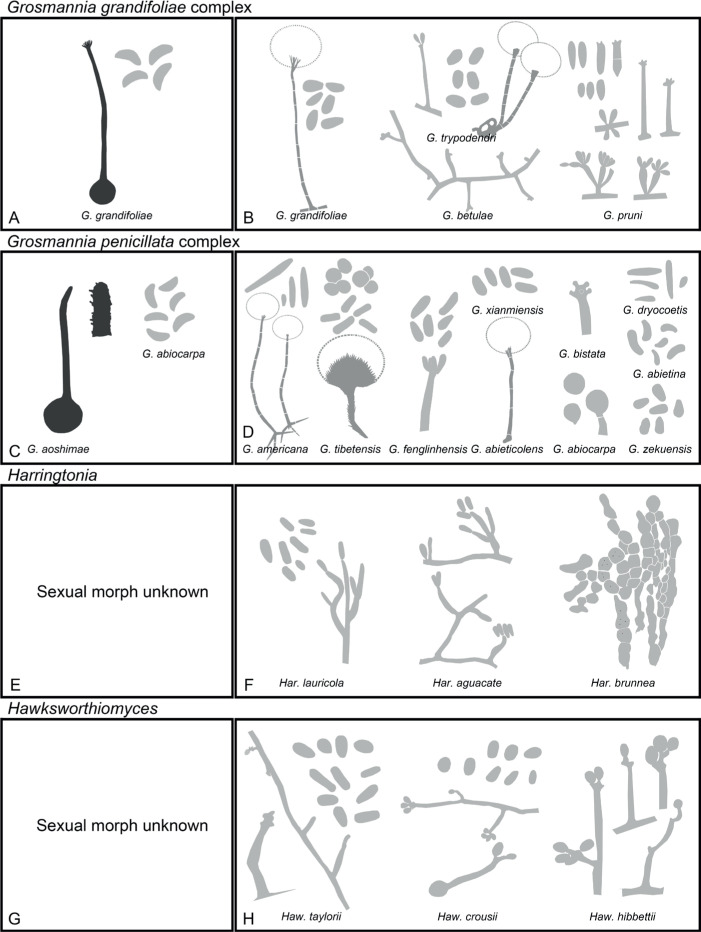

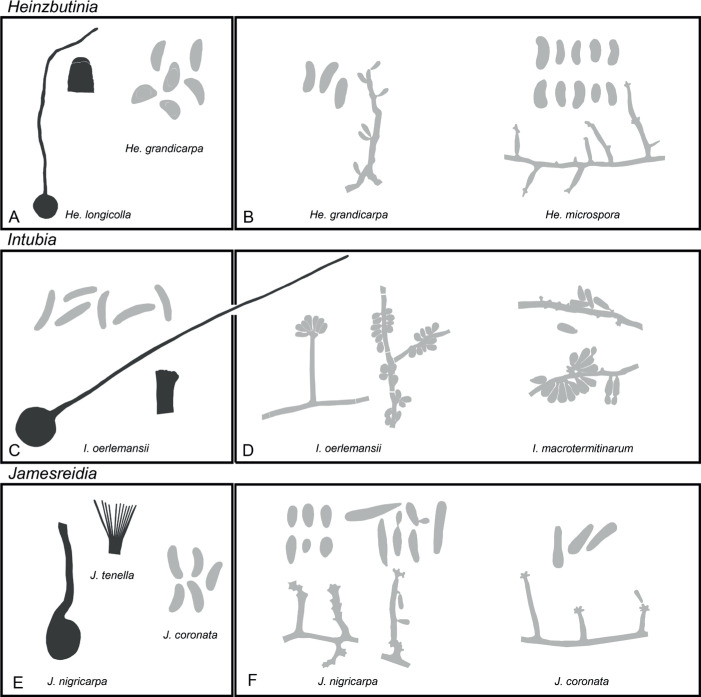

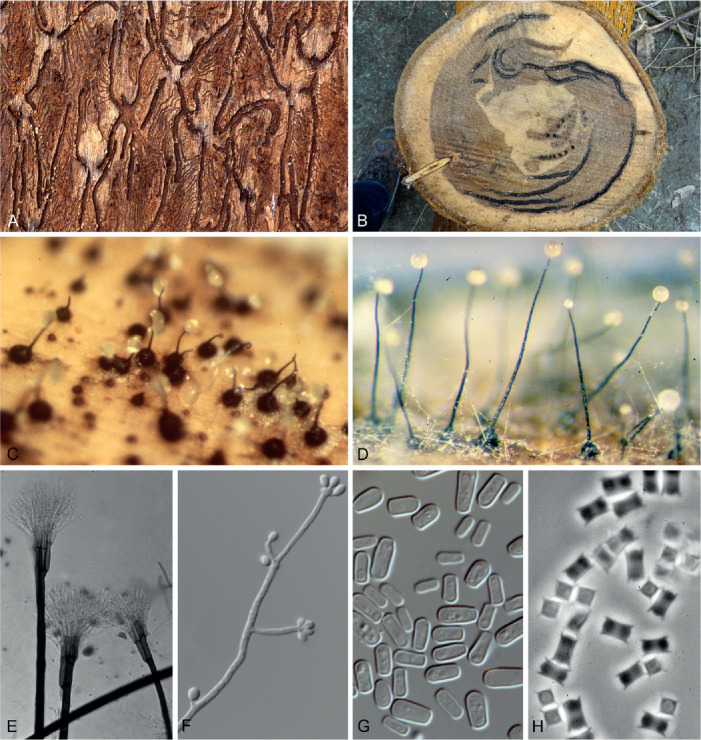

Morphology

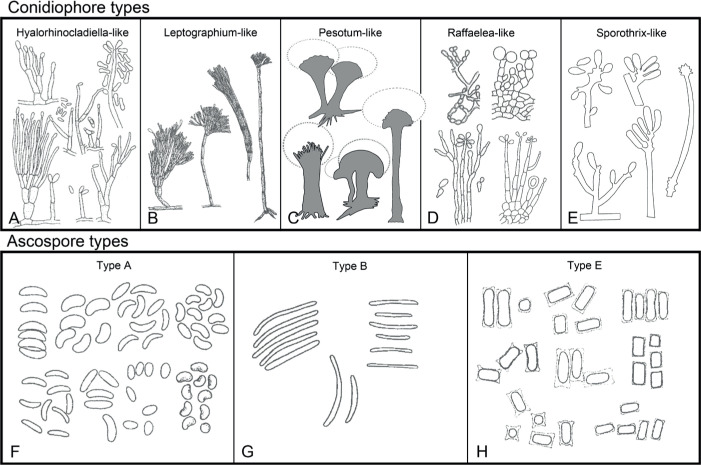

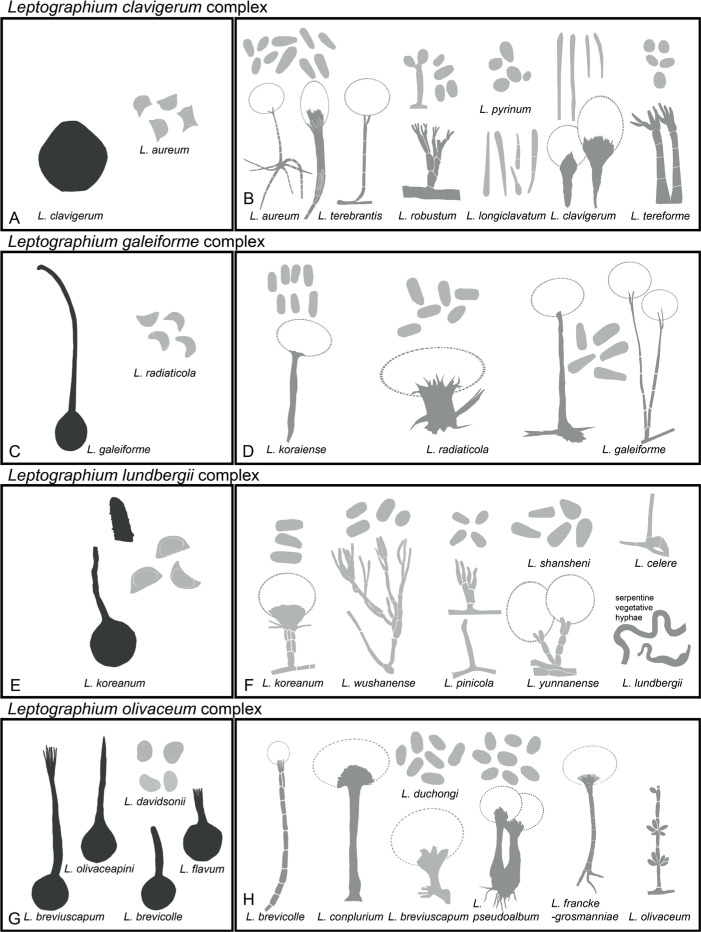

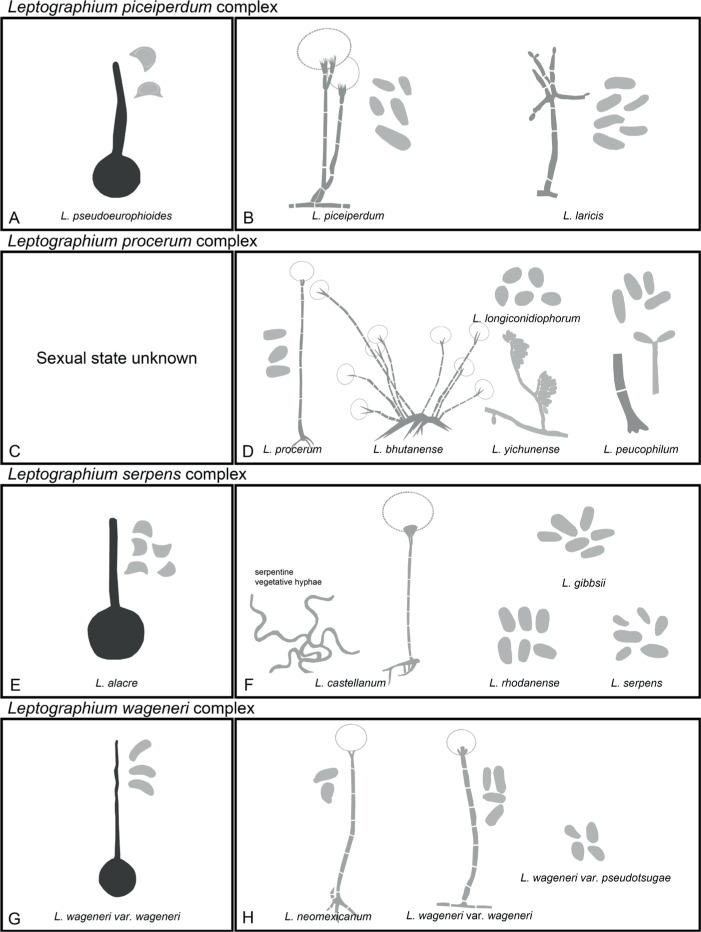

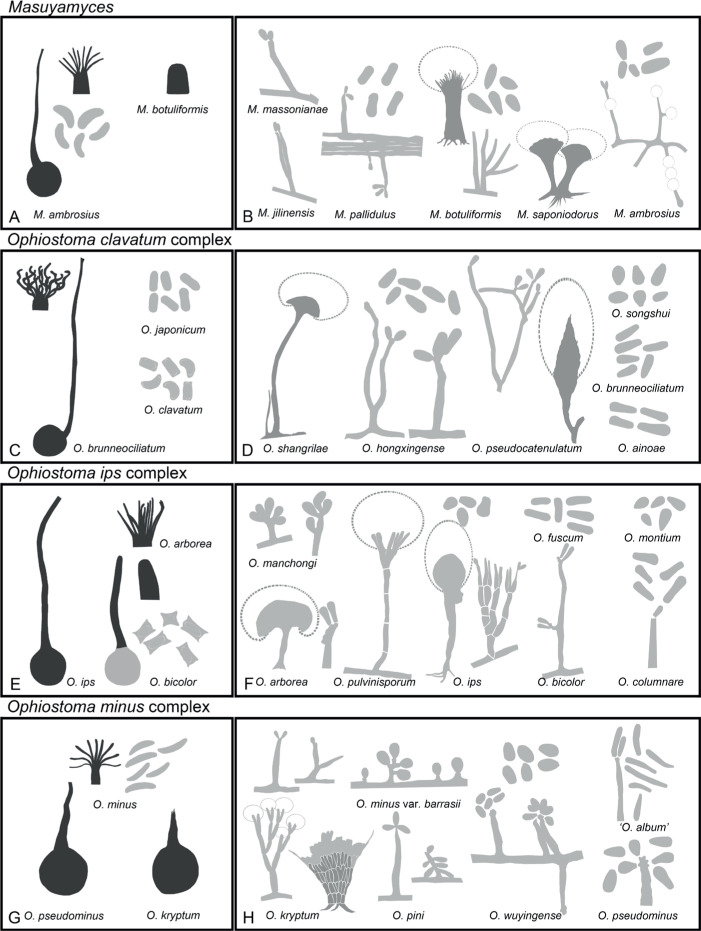

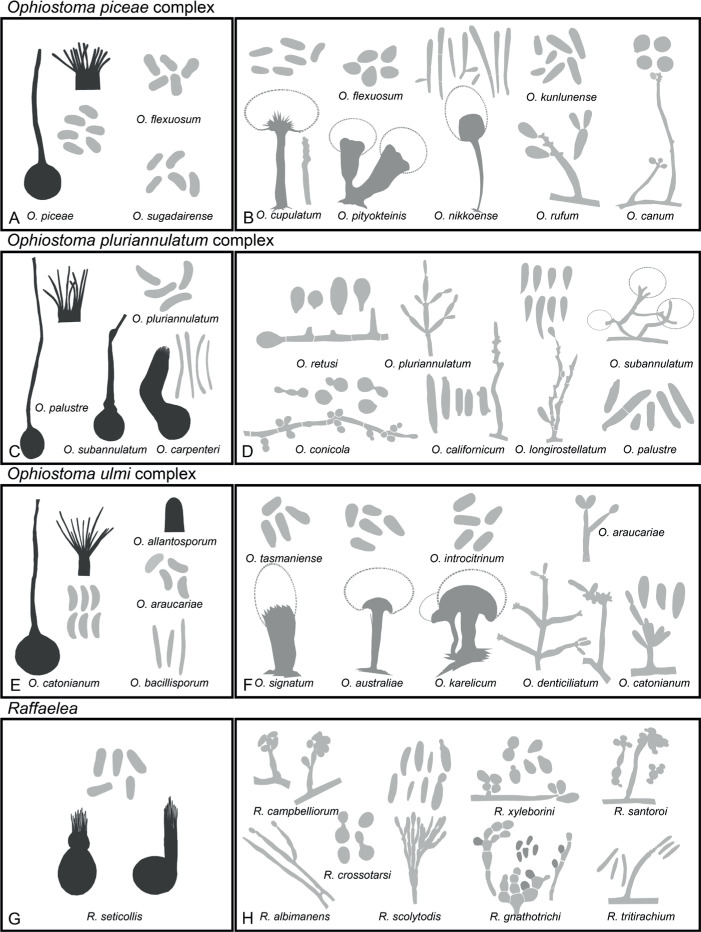

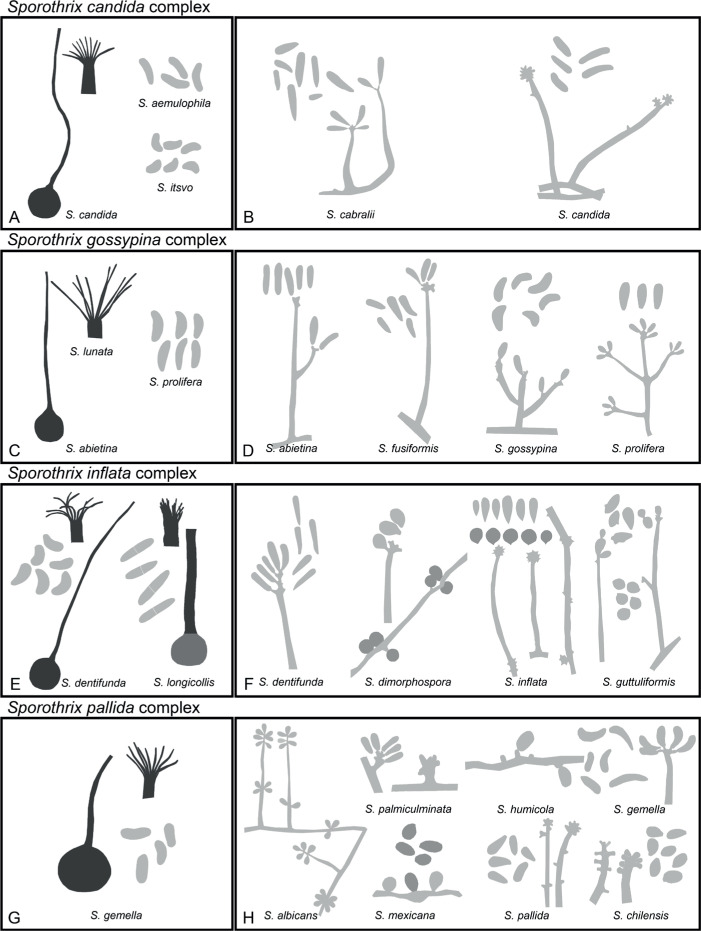

Of the 11 ascospore morphotypes defined by De Beer & Wingfield (2013) for the Ophiostomatales, three (Type A, B, E) were used to describe ascospore types in the present study (Fig. 3). Type A ascospores are those described as allantoid, bean-shaped, crescent to sickle-shaped, clavate to ovate, curved, cylindrical and slightly curved, orange section, lunate or reniform. Type B ascospores are those that are bacilliform, elongate filiform or narrow clavate. Type E ascospores are those with sheaths and are box-shaped, cylindrical, oblong, pillow-shaped, rectangular or rod-shaped. For the asexual morphs, five conidiophore types, hyalorhinocladiella-like, leptographium-like, pesotum-like, raffaelea-like and sporothrix-like, were used as descriptors where applicable (Fig. 3). Three shades of grey were applied in the figures to depict the colours of structures. Thus, hyaline to subhyaline structures were shaded in pale grey. Brown to dark brown structures were a medium-tone grey and fuscous black to black structures were presented in dark grey.

Fig. 3.

Conidiophore and ascospore types mentioned in the paper. A–E. Conidiophore types. F–H. Ascospore types sensu De Beer & Wingfield (2013). A, B, D, F–H. Adapted from illustrations in De Beer & Wingfield (2013). Shades of grey depict colours of various structures ranging from hyaline to dematiaceous.

RESULTS

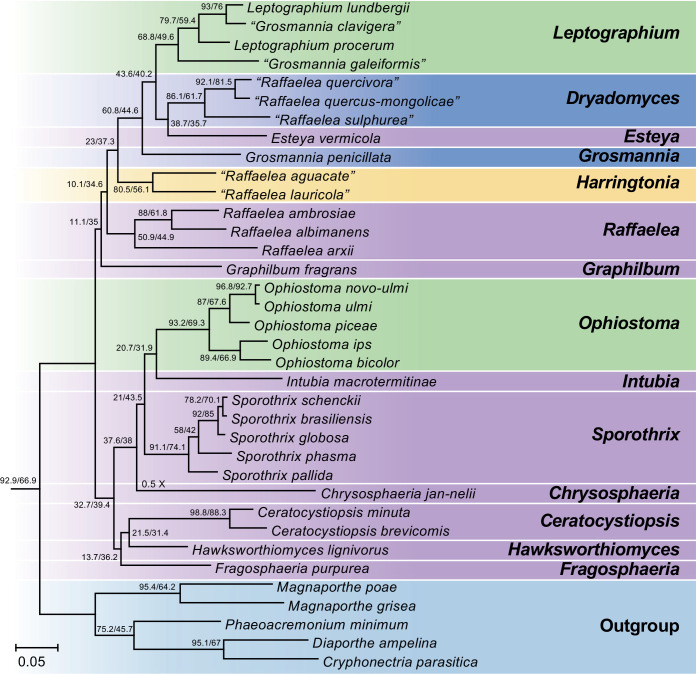

The phylogenomic tree constructed from the genome-wide sequence data for 31 ophiostomatalean species (Fig. 4) showed a similar topology to those obtained in previous studies (Nel et al. 2021, Vanderpool et al. 2018). The placement of Graphilbum fragrans was, however, different from that suggested by Vanderpool et al. (2018). This inconsistent placement for Gra. fragrans was also observed by Nel et al. (2021) where different phylogenomic approaches were applied. Species of Leptographium s.l. grouped in two distinct lineages; one of these accommodated the Grosmannia penicillata complex and the other the L. lundbergii, L. procerum and L. galeiforme complexes. Species of Raffaelea s.l. resolved in three distinct clades, which is consistent with the findings in two previous studies (Nel et al. 2021, Vanderpool et al. 2018). Otherwise, all remaining species and genera included in the analysis resided in the clades consistent with their current recognition as separate genera in the Ophiostomatales.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenomic tree obtained from supertree analysis with ASTRAL using gene trees constructed from 3 548 BUSCO genes (identified using the sordariomycetes_odb10 dataset; BUSCO v. 4.0.5). All 31 species in the Ophiostomatales for which genome sequence currently available were included in the analysis. Cryphonectria parasitica, Diaporthe ampelina, Magnaporthe grisea, Magnaporthe poae and Phaeoacremonium minimum were included as outgroup taxa. Gene concordance factors (gCF) and site concordance factors (sCF), which indicate the percentage of genes and sites that support a parcular nodes respectively, were determined using IQ-TREE2 are presented at nodes as gCF/sCF. Species names presented in double quotes denote old names which have been changed to their new respective genera subsequent to this study.

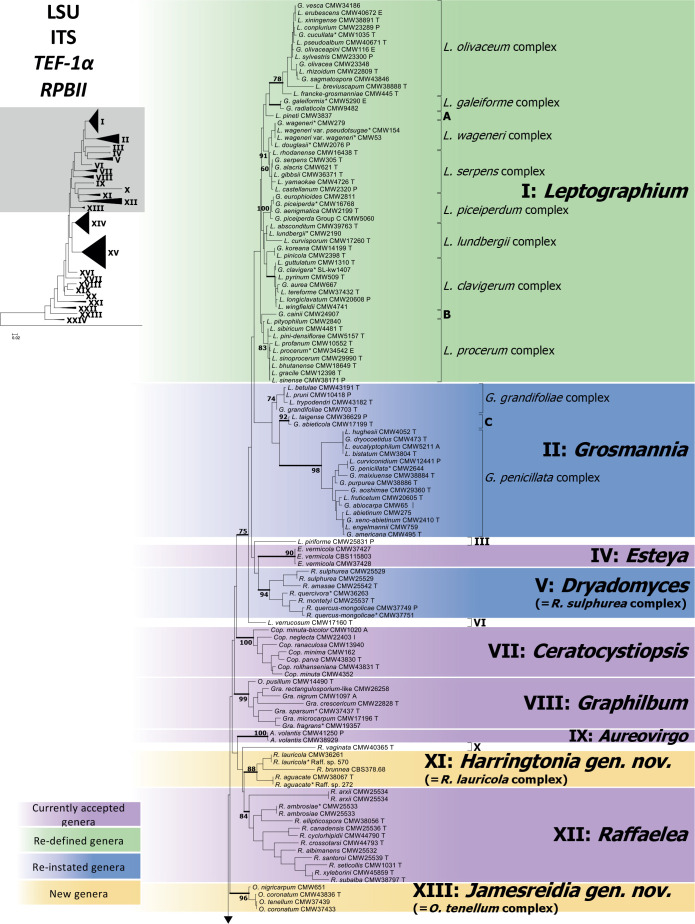

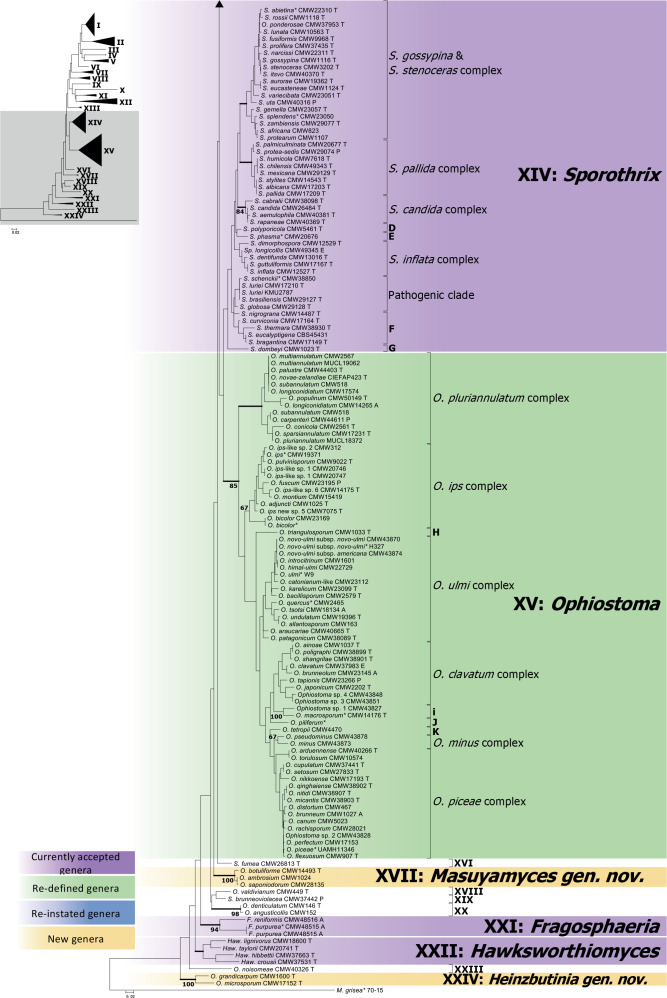

The maximum likelihood tree (Fig. 5) resulting from analyses of the concatenated dataset (LSU, ITS, TEF-1α and RPBII) for 264 isolates representing 249 species revealed 24 distinct lineages. Posterior probability values generated from Bayesian Inference analysis are indicated at the genus-level nodes (Fig. 5). Although the topologies of the individual gene trees (Figs S1–S4) were different to one another and to those in the combined tree, (apart from a few exceptions discussed below), the terminal clades were mostly consistent for the gene regions. To facilitate a discussion of the emerging results, the 24 lineages that represent genera or smaller groups were annotated using Roman numerals (I–XXIV). These were applied in the order of appearance in the concatenated tree (Fig. 5). Single species that grouped within major lineages, but not within defined species complexes, or not consistent within the same lineage in different trees, were labelled alphabetically (A–K).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree depicting the boundaries of currently accepted genera in the Ophiostomatales. This tree was generated using maximum likelihood analysis of the concatenated dataset of LSU, ITS, TEF1-α and RPBII gene regions. The dataset consisted of 264 isolates and 2 360 characters (including gaps). Bootstrap values above 60 % are shown. Bold lines indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities values above 0.8. Bootstrap values and Bayesian posterior probabilities values below the species complex level were removed for simplification. Purple blocks indicate existing genera, yellow blocks new genera described in this study, green blocks, genera that we redefine here, and blue blocks indicate genera that that have been reinstated and re-defined. (T = ex-type, E = ex-epitype, P = ex-paratype; L = ex-lectotype; A = authentic isolate, used in the original study; * Genome sequenced).

The overall topology of the LSU tree (Fig. S1) showed some differences from that of the concatenated tree, but 22 of the lineages corresponded between the two trees. The exceptions were Lineages III and XIX. Lineage III consisted of a single species in the concatenated tree, for which no LSU data were available, while Lineage XIX grouped outside the other genera in the concatenated tree, but as part of Sporothrix (Lineage XIV) in the LSU tree. Species complexes within Leptographium, Sporothrix and Ophiostoma were generally less well-defined in the LSU tree than in the concatenated tree.

The ITS tree (Fig. S2) showed little resolution below the genus level. Due to the variable nature of the ITS1 and ITS2 regions, the dataset was subjected to a strict Gblocks treatment (using automated parameters). The dataset consisted of 1 132 characters (including gaps) prior to treatment with Gblocks, and only 169 characters thereafter. The remaining dataset on which the tree (Fig. S2) is based, consisted predominantly of the 5.8S region. Nevertheless, we retained this analysis in the study because the ITS region is the officially recognised barcode for the fungi (Schoch et al. 2012). The ITS sequences were submitted to the GenBank Refseq database. The ITS tree (Fig. S2) supported separation of most of the genera, but Lineages XI, XII and XXII were not monophyletic in this tree, when compared to the concatenated tree. The relatively small dataset also failed to resolve most of the species complexes for the larger genera.

The TEF-1α tree (Fig. S3) resolved almost all the lineages representing species complexes, but failed to support monophyly of Lineages I, II, VIII, XI and XXII.

The RPBII tree (Fig. S4) supported the separation of all genera, species complexes and smaller lineages apart from Lineage XII that separated in four clades, and Lineage VIII that grouped within Lineage I.

Based on the concatenated tree (Fig. 5), Lineage I included species complexes previously defined in Leptographium s.l. (De Beer & Wingfield 2013), namely the Leptographium clavigerum, L. galeiforme, L. lundbergii, L. olivaceum, L. piceiperdum, L. procerum, L. serpens and L. wageneri complexes; as well as two species not forming part of these species complexes (A & B). Lineage II included the G. grandifoliae and G. penicillata species complexes and a smaller lineage (C). Leptographium piriforme was labelled as Lineage III and L. verrucosum as Lineage VI, both grouping outside of Leptographium (Lineage I). Lineage IV consisted of three isolates of the monotypic genus Esteya. The Raffaelea sulphurea complex formed Lineage V. Ceratocystiopsis spp. formed Lineage VII, Graphilbum formed Lineage VIII and Aureovirgo formed Lineage IX. Raffaelea vaginata grouped outside of Raffaelea (Lineage XII) and was labelled Lineage X. Lineage XI consisted of the R. lauricola complex, distinct from Raffaelea spp., which formed Lineage XII. The Ophiostoma tenellum complex formed Lineage XIII. Sporothrix and Ophiostoma, as defined by De Beer et al. (2016a), formed Lineages XIV and XV, respectively. Lineage XIV consisted of the S. gossypina and S. stenoceras species complexes (which grouped inseparably from each other), the S. candida, S. inflata and S. pallida species complexes, the pathogenic clade (including the type species of Sporothrix, S. schenckii), as well as groups D to G. Lineage XV included the O. clavatum, O. ips, O. minus, O. piceae, O. pluriannulatum and O. ulmi complexes as well as groups H to K. Sporothrix fumea and S. brunneoviolacea both grouped separate from Sporothrix, and were labelled as Lineages XVI and XIX, respectively. Three Ophiostoma species consistently grouped together and distinct from Ophiostoma and were labelled Lineage XVII. Lineage XVIII included O. valdivianum and Lineage XX consisted of O. denticulatum and O. angusticollis. Lineage XXI represented Fragosphaeria, and Lineage XXII represented Hawksworthiomyces. Ophiostoma noisomeae was labelled Lineage XXIII, while O. grandicarpum and O. microsporum together constituted Lineage XXIV.

Afroraffaelea was excluded from the final analyses because the placement of the type for this monotypic species, Afr. ambrosiae, was completely incongruent among the separate gene trees (data not shown), most often forming long branches, distinct from all other groups. This impacted negatively on the support for several lineages in the concatenated tree, which prompted the decision to exclude the species from the analyses. Likewise, the two species of Intubia and the monotypic Chrysosphaeria were excluded from the analyses due to their ambiguous generic placement when using traditionally applied phylogenetic markers (Nel et al. 2021).

TAXONOMY

Phylogenetic analyses for four gene regions revealed 16 lineages within the Ophiostomatales, which we now recognise as valid genera. Seven of these represent genera currently known and defined in the Order. They include Esteya (Lineage IV), Ceratocystiopsis (Lineage VII), Graphilbum (Lineage VIII), Aureovirgo (Lineage IX), Sporothrix (Lineage XIV), Fragosphaeria (Lineage XXI) and Hawksworthiomyces (Lineage XXII). Two Lineages (Lineage II and V), which were clearly distinct from all other genera, included the ex-type cultures of Grosmannia penicillata and Dryadomyces amasae respectively. These species have previously been treated in the genera Grosmannia/Leptographium and Raffaelea respectively and we have consequently reinstated and redefined the genera Grosmannia and Dryadomyces with emended descriptions. Four lineages (Lineage XI, XIII, XVII and XXIV) are recognised as representing new genera and are described as such. Characters of these new genera were previously included in the descriptions of Leptographium, Ophiostoma and Raffaelea, and we have consequently emended their descriptions. Although Afroraffaelea, Chrysosphaeria, Intubia, and the fossil genus Paleoambrosia were not included in our analyses, we recognise these genera as valid, retaining them in the Ophiostomatales.

The placement of the remaining lineages (III, VI, X, XVI, XVIII, XIX, XX and XXIII) remains uncertain, as most of these lineages were represented by single species that grouped inconsistently in our analyses. We have chosen not to describe new monotypic genera for these lineages, but rather to delay this decision until additional taxa are discovered that support establishing novel genera. In addition to describing and redefining genera, new combinations have been provided for species where necessary.

Circumscription of the Ophiostomatales and Ophiostomataceae

At present there is no need to revise the description of the Ophiostomatales. This is because the emended description by De Beer et al. (2013a) broadly encompasses the morphologies of all genera, including the novel genera described in the present study. With more than 300 species and clearly distinct broad morphological groups in the Order, it would make sense to provide a narrower definition for the Ophiostomataceae, and to introduce one or more additional families. However, in view of the lack of support for the deeper nodes in our analyses, we have refrained from doing so at present. We suggest that this should be done only when related taxa outside the Ophiostomatales, such as those included in the LSU and SSU phylogenies of De Beer et al. (2013a), can be incorporated in multigene phylogenies to provide more robust context within the Sordariomycetidae.

Currently accepted genera in the Ophiostomatales

All currently accepted genera in the Ophiostomatales are defined below, and based on our results, descriptions have been emended where necessary. Genera and species complexes are discussed in alphabetical order, with lineage numbers corresponding to their appearance in the concatenated phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5).

New combinations

Where required, new combinations have been provided, and these are listed under the relevant genera. Species that have been treated in a particular genus but were shown based on our data to reside in a different genus, for which a name already exists in the appropriate genus, have been listed under ‘current name’ in Table 1, and thus not in the following section For example, Grosmannia serpens is now treated as Leptographium serpens but did not require a new combination and is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Taxa described in the Ophiostomatales, based on currently published data.

| Previous name | Current name | CMW1 | CBS or other1 | Type2 | Isolated from | Country | Collector |

GenBank Accession Numbers3

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | TEF1-α | RPBII | ||||||||

| Afroraffaelea | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Afr. ambrosiae | Afr. ambrosiae | 48331 | 141678 | T | Premnobius cavipennis | Florida, USA | C. Bateman | OM632703 | OM584293 | OM631576 | OM631577 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Aureovirgo | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| A. volantis | A. volantis | 41250 | 139649 | P | Cyrtogenius africus on Euphorbia ingens | South Africa | J.A. van der Linde | OM501369 | OM514700 | OM631743 | OM631579 |

| A. volantis | A. volantis | 38929 | 140081 | Cyrtogenius africus on Euphorbia ingens | South Africa | J.A. van der Linde | OM501368 | OM514699 | OM631742 | OM631578 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ceratocystiopsis | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Cop. brevicomis | Cop. brevicomis | 40952 | 333.97 | T | Dendroctonus brevicomis | California, USA | T. Harrington | EU913722 | EU913683 | – | – |

| Cop. collifera | Cop. collifera | 7074 | 126.89 | T | Dendroctonus valens on Pinus teocote | Mexico | J. Marmolejo | EU913721 | EU913681 | – | – |

| Cop. concentrica | Cop. concentrica | – | WIN(M)71-07 | Pinus banksiana | Canada | J. Reid, A. Olchowecki | – | AF135571 | – | – | |

| Cop. conicicollis | Cop. conicicollis | – | WIN(M)69-25 | Abies balsemea | Canada | J. Reid, A. Olchowecki | – | – | – | – | |

| Cop. longispora | Cop. longispora | – | UM48 | Pinus sp. | Canada | A. Olchowecki | EU913723 | EU913684 | – | – | |

| Cop. lunata # | Cop. lunata | 55897 | 47171 | T | Xylosandrus crassciusculus | South Africa | W.J. Nel | MW028169 | MW028141 | – | – |

| Cop. manitobensis | Cop. manitobensis | 13792 | UAMH9813 | T | Manitoba beetle gallery in Pinus resinosa | Canada | J. Reid | EU913714 | EU913674 | – | – |

| Cop. minima | Cop. minima | 162 | 182.86 | Pinus banksiana | Wisconsin, USA | M.J. Wingfield | OM501370 | OM514701 | OM631744 | – | |

| Cop. minuta* | Cop. minuta | 4352 | 138717 | Ips cembrae | Poland | T. Kirisits | OM501372 | OM514703 | OM631745 | OM631581 | |

| Cop. minuta-bicolor * | Cop. minuta-bicolor | 1020 | 635.66 | A | Gallery of Ips sp. in Pinus contorta | USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501371 | OM514702 | – | OM631580 |

| Cop. neglecta | Cop. neglecta | 22403 | 100596 | I | Hylurgops palliatus | Germany | R. Kirschner | OM501373 | OM514704 | OM631746 | OM631582 |

| Cop. ochracea | Cop. ochracea | – | DAOM100148 | Picea mariana | Canada | H.D. Griffin | – | – | – | – | |

| Cop. pallidobrunnea | Cop. pallidobrunnea | – | UM51 | Populus tremuloides | Canada | J. Reid | – | EU913682 | – | – | |

| Cop. parva | Cop. parva | 43830 | UAMH9650 | T | Abies balsamea | Canada | A. Olchowecki | OM501374 | – | OM631747 | OM631583 |

| Cop. ranaculosa | Cop. ranaculosa | 13940 | 119683 | Pinus echinata | North Carolina, USA | F. Hains | OM501375 | OM514705 | OM631748 | OM631584 | |

| Cop. rollhanseniana | Cop. rollhanseniana | 43831 | UAMH9774 | T | Unknown beetle on Pinus sylvestris | Norway | J. Reid | OM501376 | OM514706 | OM631749 | – |

| Cop. spinulosa | Cop. spinulosa | DAOM110151 | T | Tilia americana | Canada | H.D. Griffin | – | – | – | – | |

| Cop. synnemata # | Cop. synnemata | – | NRIF 16918DA | T | Dryocoetes alni infesting Populus tremula | Poland | K. Miœkiewicz | MN900988 | MN900988 | MN901018 | – |

| Cop. yantaiensis # | Cop. yantaiensis | – | SNM650 | T | Pinus thunbergii | China | R. Chang | MW989411 | MZ819924 | MZ853080 | – |

| Cop. weihaiensis # | Cop. weihaiensis | – | SNM649 | T | Pinus thunbergii | China | R. Chang | MW989413 | MZ819926 | MZ853082 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Chrysosphaeria | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Chr. jan-nelii # | Chr. jan-nelii | 47058 | 141570 | T | Termitomyces fungal comb of Macrotermes natalensis | South Africa | W.J. Nel | MT637038 | MT637006 | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Dryadomyces (R. sulphurea complex) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| R. amasae | D. amasae | 25542 | 116694 | T | Amasa concitatus on Angiosperms | Taiwan | H. Gebhardt | – | MT629750 | OM631750 | OM631585 |

| R. montetyi | D. montetyi | 25537 | 463.94 | T | Platypus cylindrus on Quercus suber | France | D. Vouland | – | MT629761 | OM631751 | – |

| R. quercivora * | D. quercivorus | 36263 | 122982 | Quercus mongolica | Japan | T. Kubono | MT633072 | MT629762 | OM631752 | OM631586 | |

| R. quercus-mongolicae | D. quercus-mongolicae | 37749 | KACC44403 | P | Quercus mongolica | South Korea | K.H. Kim | MT633073 | MT629764 | OM631754 | OM631588 |

| R. quercus-mongolicae * | D. quercus-mongolicae | 37751 | KACC44405 | Platypus koryoensis-infested Quercus | South Korea | K.H. Kim | MT633074 | MT629763 | OM631753 | OM631587 | |

| R. sulphurea* | D. sulphureus | 25529 | 380.68 | Xyleborus saxesenii gallery in Populus deltoides | Kansas, USA | L.R. Batra | MT633077 | MT629768 | OM631755 | OM631589 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Esteya | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| E. vermicola | E. vermicola | 37427 | 100821 | Olea europeae | Italy | S. Frisullo | – | OM514708 | OM631757 | OM631591 | |

| E. vermicola | E. vermicola | 37428 | 156.82 | Pinus sp. | Taiwan | T. Tatsuno | OM501378 | OM514709 | OM631758 | – | |

| E. vermicola* | E. vermicola | – | 115803 | S. intricatus and its galleries in oak trees | Czech Republic | L. Marvanova | OM501377 | OM514707 | OM631756 | OM631590 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Fragosphaeria | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| F. purpurea* | F. purpurea | 48515 | 133.34 | A | Fagus sp. | England, UK | C.G.C. Chesters | OM501379 | OM514710 | OM631759 | OM631592 |

| F. reniformis | F. reniformis | 48516 | 134.34 | A | Fagus sp. | England, UK | E.W. Mason | OM501381 | – | OM631760 | OM631593 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Graphilbum | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Gra. acuminatum # | Gra. acuminatum | 54769 | 145828 | T | Ips acuminatus gallery on Pinus sylvestris | Poland | R. Jankowiak | MN548902 | – | MN548952 | – |

| Gra. brunneocrinitum | Gra. brunneocrinitum | – | TRTC34581 | T | Abies balsamea | Canada | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gra. carpaticum # | Gra. carpaticum | 43141 | 145835 | T | Pissodes piceae gallery on Abies alba | Poland | P. Majka | KY568116 | – | MN548956 | – |

| Gra. curvidentis # | Gra. curvidentis | 54779 | 145832 | T | Pitokteines curvidens gallery on Abies alba | Poland | P. Bilański | KY568111 | – | KY56850 | – |

| Gra. crescericum | Gra. crescericum | 22828 | 130864 | T | Hylurgops palliatus on Pinus radiata | Spain | P. Romón | OM501403 | OM514749 | OM631779 | OM631604 |

| Gra. curvicolle | Gra. curvicolle | – | WIN(M)70-25 | T | Abies balsamea | Canada | J. Reid, A. Olchowecki | – | – | – | – |

| Gra. fragrans * | Gra. fragrans | 19357 | 138720 | Pinus patula | South Africa | X. D. Zhou | OM501404 | OM514750 | OM631780 | OM631605 | |

| Gra. furuicola # | Gra. furuicola | 44770 | 145813 | T | Tomicus piniperda in Pinus sylvestris | Norway | R.H. Lindseth, T.H. Sundt | MN548907 | – | MN548961 | – |

| Gra. gorcense # | Gra. gorcense | 34153 | 146203 | T | Tetropium sp. in Picea abies | Poland | R. Jankowiak | MN548919 | – | MN548972 | – |

| Gra. interstitiale # | Gra. interstitiale | 54780 | 145816 | T | Hylurgops interstitialis in Pinus sylvestris | Russia | H. Solheim | MN548909 | – | MN548963 | – |

| Gra. ipis-grandicollis # | Gra. ipis-grandicollis | – | VPRI43762 | Ips grandicollis gallery on Pinus radiata | Australia | A.J. Carnegie | MW046071 | MW046117 | MW066405 | – | |

| Gra. kesiyae | Gra. kesiyae | 41729 | 139652 | T | Polygraphus szemaoensis on Pinus kesiya | China | S. Taerum | MG205669 | – | – | – |

| Gra. microcarpum | Gra. microcarpum | 17196 | YCC439 | T | Cryphalus montanus | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | OM501405 | OM514751 | OM631781 | OM631606 |

| Gra. nigrum | Gra. nigrum | 1097 | 163.61 | A | Abies lasiocarpa | Colorado, USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501406 | OM514752 | – | OM631607 |

| Gra. niveum # | Gra. niveum | – | SNM145 | T | Pinus thunbergii | China | R. Chang | MW989418 | – | MZ019548 | – |

| Gra. puerense | Gra. puerense | 41673 | 139640 | T | Ips acuminatus on Pinus kesiya | China | S. Taerum | MG205671 | – | – | – |

| Gra. rectangulosporium | Gra. rectangulosporium | 29364 | MAFF 238952 | T | Polygraphus proximus on Abies mariesii | Japan | N. Ohtaka | MG205671 | – | – | – |

| Gra. roseum # | Gra. roseum | 40349 | 141074 | T | Curtisia dentata | South Africa | T. Musvuugwa | KY050751 | – | – | – |

| Gra. sexdentatum # | Gra. sexdentatum | 54773 | 145814 | T | Ips sexdentatus in Pinus sylvestris | Norway | H. Solheim, M.E. Waalberg | MN548915 | – | MN548968 | – |

| Gra. sparsum * | Gra. sparsum | 37437 | 405.77 | T | Bark beetle gallery on Picea glauca | Alaska, USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501409 | OM514755 | – | OM631608 |

| Gra. translucens # | Gra. translucens | – | SNM144 | T | Pinus thunbergii | China | R. Chang | MW989416 | – | MZ019546 | – |

| Gra. tsugae | Gra. tsugae | – | UAMH11701 | T | Tsuga heterophylla | Canada | J. Reid, B. Reid | KJ661745 | – | – | – |

| Gra. tubicolle | Gra. tubicolle | 43837 | UAMH9686 | T | Pinus banksiana | Canada | A. Olchowecki | – | – | – | – |

| O. pusillum | Gra. pusilllum | 14490 | – | T | Pinus densiflora | Japan | H. Masuya | OM501407 | OM514753 | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Grosmannia: G. penicillata complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. abiocarpa | G. abiocarpa | 65 | 594.85 | L | Ips sp. on Picea engelmannii | Colorado, USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501384 | OM514715 | OM631764 | – |

| G. americana | G. americana | 495 | 497.96 | T | Dendroctonus simplex on Larix laricina | Vermont, USA | D. Bergdalh | OM501385 | OM514718 | OM631765 | OM631595 |

| G. aoshimae | G. aoshimae | 29360 | MAFF238948 | T | Polygraphus proximus on Abies mariesii | Japan | N. Ohtaka | OM501386 | OM514719 | OM631766 | OM631596 |

| G. crassifolia # | G. crassifolia | 38885 | 136505 | T | Polygraphus poligraphus in Pinus crassifolia | China | X.D. Zhou, S. Taerum | – | MN644475 | MN647897 | – |

| G. dryocoetis | G. dryocoetis | 473 | 376.66 | T | Dryocoetes confusus on Abies lasiocarpa | Canada | A.C. Molnar | OM501392 | OM514727 | OM631768 | OM631597 |

| L. fenglinhense | G. fenglinhensis | 44579 | 141896 | T | Ips typographus on Pinus sp. | China | R. Chang, S.F. Chen | MH144128 | – | MH124404 | – |

| G. maixiuense | G. maixiuense | 38884 | 136502 | T | Polygraphus poligraphus, Ips shangrila in Picea crassifolia | China | M. Yin, S. Taerum, X.D. Zhou | OM501396 | MN644474 | MN647900 | OM631599 |

| G. penicillata * | G. penicillata | 2644 | 116008 | Picea abies | Norway | H. Solheim | OM501397 | OM514737 | OM631774 | OM631600 | |

| G. purpurea | G. purpurea | 38886 | 136975 | T | Ips shangrila on Picea purpurea | China | M. Yin, S. Taerum, X.D. Zhou | OM501399 | MN644476 | MN647914 | – |

| G. tibetensis | G. tibetensis | – | CFCC53415 | T | Orthotomicus sp. on Pinus likiangensis var. balfouriana | Tibet | Z. Wang, Q. Lu | MT269759 | – | MT268756 | – |

| G. xeno-abietinum | G. xeno-abietinum | 2410 | 136514 | T | Pinus ponderosa | California, USA | T. Harrington | OM501402 | MN644471 | MN647894 | OM631603 |

| G. xianmiense # | G. xianmiense | 38892 | 136500 | T | Polygraphus poligraphus in Pinus crassifolia | China | X.D. Zhou, S. Taerum | – | MN644479 | MN647911 | – |

| G. zekuensis # | G. zekuensis | 41876 | 141901 | T | Bakerdania sp. in gallery of Ips nitidus on Picea crassifolia | China | S.J. Taerum | MH121683 | MH121683 | MH124546 | – |

| L. abieticolens | G. abieticolens | 2865 | 115248 | T | Abies balsamea | Vermont, USA | D. Bergdalh | AF343701 | – | – | – |

| L. abietinum | G. abietina | 275 | 118590 | Picea engelmannii | Canada | A. Molnar | OM501383 | OM514713 | OM631763 | OM631594 | |

| L. altius | G. altior | 12471 | 123619 | T | Picea koraiensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406851 | – | HQ406875 | – |

| L. bistatum | G. bistata | 3804 | 120192 | T | Pinus radiata | Japan | J.J. Kim | OM501388 | OM514721 | OM631795 | – |

| L. chlamydatum | G. chlamydata | 36631 | 128840 | Pityogenes chalcographus on Picea abies | Finland | Z.W. de Beer | JF279965 | – | JF280080 | – | |

| L. curviconidium | G. curviconidia | 12441 | 123617 | P | Ips typographus on Picea koraiensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | OM501390 | OM514725 | OM631767 | – |

| L. curvisporum | G. curvispora | 17260 | 123914 | T | Picea abies | Norway | M.J. Wingfield, H. Solheim | OM501391 | OM514726 | EU979347 | – |

| L. engelmannii | = G. abietina | 759 | – | Picea engemannii | Canada | R.W. Davidson | – | OM631763 | OM631762 | – | |

| L. eucalyptophilum | G. eucalyptophila | 5211 | – | A | Eucalyptus urophylla × E. pellita | Democratic Republic of Congo | J. Roux | OM501393 | OM514728 | OM631769 | – |

| L. euphyes | G. euphyes | 259 | 109701 | T | Pinus strobus | New Zealand | M. Dick | AF343686 | – | – | – |

| L. fruticetum | G. fruticetum | 20605 | – | T | Picea engelmannii × P. glauca | Canada | S. Massoumi Alamouti | OM501394 | OM514730 | OM631770 | – |

| L. hughesii | G. hughesii | 4052 | 109709 | T | Aquilaria sp. | Vietnam | B. Lanchette | OM501395 | OM514732 | OM631772 | OM631598 |

| L. pistaciae | G. pistaciae | 12499 | 123626 | T | Pistacia chinensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406846 | – | HQ406870 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Grosmannia: G. grandifoliae complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. grandifoliae | G. grandifoliae | 703 | ATCC28746 | T | Fagus grandifolia | Iowa, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | – | OM631771 | – |

| L. betulae | G. betulae | 43191 | 142734 | T | Scolytus ratzeburgi on Betula verrucosa | Poland | R. Jankowiak | KY801840 | – | KY801817 | – |

| L. pruni | G. pruni | 10418 | 120197 | P | Polygraphus ssiori on Prunus jamasakura | Japan | H. Masuya | OM501398 | OM514740 | OM631775 | – |

| L. trypodendri | G. trypodendri | 43182 | 142724 | T | Trypodendron domesticum on Fagus sylvatica | Norway | R. Jankowiak | KY801828 | – | KY801805 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Grosmannia: Group C | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. abieticola | G. abieticola | 17199 | – | T | Dryocoetes hectographus on Abies mariesii | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | OM501382 | OM514712 | OM631761 | – |

| L. innermongolicum | G. innermongolica | – | MUCL55158 | T | Ips subelongatus on Larix sp. | China | Q. Lu | KM236107 | – | KM981763 | – |

| L. taigense | G. taigensis | 36629 | – | P | Ips typographus on Picea abies | Russia | Z.W. de Beer | OM501400 | OM514744 | OM631777 | – |

| L. gestamen | G. gestamen | 38096 | CIEFAP453 | T | Nothofagus dombeyi | Argentina | A. de Errasti | KT362234 | KT362232 | KT381300 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Harringtonia gen. nov. (previously Raffalea lauricola complex) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| R. aguacate | Har. aguacate | 38067 | 141672 | T | Persea americana | Florida, USA | C.L. Harmon | – | KJ909296 | – | – |

| R. aguacate * | Har. aguacate | – | Raff. sp. 272 | Persea americana | Florida, USA | C.L. Harmon | MT633065 | MT629748 | OM631783 | OM631613 | |

| R. brunnea | Har. brunnea | – | 378.68 | Monarthrum sp. | USA | L.R. Batra | – | EU177457 | – | – | |

| R. lauricola * | Har. lauricola | – | Raff. sp. 570 | Xyleborus sp. on Persea sp. | Florida, USA | J. Smith | MT633071 | MT629759 | OM631784 | OM631614 | |

| R. lauricola | Har. lauricola | 36261 | PL159 | Xyleborus glabratus | Georgia, USA | S. Fraedrich | OM501411 | MT629760 | OM631785 | OM631615 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Hawksworthiomyces | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Haw. crousii | Haw. crousii | 37531 | MUCL55928 | T | Bamboo chips | South Korea | J.J. Kim | KX396551 | KX396548 | OM652622 | OM631609 |

| Haw. hibbettii | Haw. hibbettii | 37663 | MUCL55929 | T | Trachymyrmex sp. | Texas, USA | U. Mueller | KX396550 | KX396547 | OM652623 | OM631610 |

| Haw. lignivorus* | Haw. lignivorus | 18600 | 119148 | T | Eucalyptus pole | South Africa | E.M. de Meyer | OM501410 | OM514756 | OM631782 | OM631611 |

| Haw. taylorii | Haw. taylorii | 20741 | MUCL55927 | T | Eucalyptus pole | South Africa | E.M. de Meyer | KX396549 | KX396546 | OM652624 | OM631612 |

| ‘Haw. sequentia ENAS’ | ‘Haw. sequentia ENAS’ | – | nik62104a_03C_19 | T | Picea log | Sweden | – | HQ611296 | – | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Heinzbutinia gen. nov. | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| O. grandicarpum | He. grandicarpa | 1600 | 250.88 | T | Quercus robor | Poland | H. Butin | OM501412 | OM514757 | OM631786 | OM631616 |

| O. longicollum | He. longicolla | – | JCM10198 | T | Quercus mongolica var. grosseserrata infested by Platypus quercivorus | Japan | H. Masuya | – | – | – | – |

| O. microsporum | He. microspora | 17152 | 440.69 | T | Quercus sp. | Virginia, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | OM514758 | OM631787 | OM631617 |

| O. solheimii # | He. solheimii | 52050 | 144881 | T | Anisandrus dispar infesting Quercus robur | Poland | P.Wieczorek | MH283134 | – | MH283488 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Intubia | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| I. macrotermitinarum # | I. macrotermitinarum | 46496 | 141560 | T | Termitomyces fungal comb of Macrotermes natalensis | South Africa | W.J. Nel | MT637025 | – | – | – |

| I. oerlemansii # | I. oerlemansii | 47048 | 141564 | T | Termitomyces fungal comb of Macrotermes natalensis | South Africa | W.J. Nel | MT637024 | – | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Jamesreidia gen. nov. (previously O. tenellum complex) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| O. coronatum | J. coronata | 43836 | UAMH9685 | T | Pinus sp. | Canada | A. Olchowecki | OM501413 | OM514759 | OM631788 | OM631618 |

| O. nigricarpum | J. nigricarpa | 651 | 638.66 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Idaho, USA | R.W. Davidson | AY280490 | DQ294356 | – | – | |

| O. rostrocoronata | J. rostrocoronata | 456 | 434.77 | Pulpwood chips | Wisconsin, USA | R.W. Davidson | AY194509 | KX590871 | – | – | |

| O. tenellum | J. tenella | 37439 | 189.86 | Pinus sp. | Colorado, USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501414 | OM514760 | OM631789 | – | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. clavigerum complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. aurea | L. aureum | 667 | 438.69 | A | Pinus contorta var. latifolia | Canada | R. W. Davidson | OM501387 | OM514720 | OM631793 | OM631621 |

| G. clavigera * | L. clavigerum | – | SL-Kw1407 | Sapwood associated with Dendroctonus ponderosae | Canada | S. Lee | OM501421 | OM514723 | OM631799 | OM631624 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| G. robusta | L. robustum | 668 | – | T | Pinus ponderosa | Idaho, USA | R.C.R. Jeffrey, R.W. Davidson | – | AY544619 | JF798465 | – |

| L. longiclavatum | L. longiclavatum | 20608 | – | P | Pinus contorta | Canada | S. Lee | – | OM514771 | – | – |

| L. pyrinum | L. pyrinum | 509 | 120181 | T | Dendroctonus adjunctus | USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501445 | OM514781 | OM631819 | OM631642 |

| L. terebrantis | L. terebrantis | 29841 | 337.70 | T | Dendoctronus terebrantis | Louisiana, USA | S.J. Baras | JF798477 | – | JF798470 | – |

| L. tereforme | L. tereforme | 37432 | 125736 | T | Hylurgus ligniperda | California, USA | S.J. Kim | OM501455 | OM514786 | OM631828 | OM631649 |

| L. wingfieldii | L. wingfieldii | 4741 | – | Pinus densiflora | Japan | H. Masuya | OM501461 | OM514789 | OM631834 | OM631654 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. galeiforme complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. galeiformis* | L. galeiforme | 5290 | 115711 | E | Pinus sylvestris | Scotland | T. Kirisits | OM501428 | OM514731 | OM631806 | OM631631 |

| G. radiaticola | L. radiaticola | 9482 | – | Hylurgus ligniperda on Pinus radiata | Chile | X.D. Zhou | OM501446 | OM514742 | OM631820 | OM631643 | |

| L. doddsii # | L. doddsii | 34479 | 143470 | T | Dendroctonus valens | California, USA | M.J. Wingfield | MT637215 | MT637212 | MT637205 | – |

| L. gordonii # | L. gordonii | 34619 | 143477 | T | Dendroctonus valens in Pinus resinosa | New Hampshire, USA | M.J. Wingfield | MT637226 | MT637213 | MT637207 | – |

| L. koraiense | L. koraiense | 44461 | 141898 | T | Ips typographus on Pinus koraiensis | China | R. Chang | MH144096 | – | MH124372 | – |

| L. owenii # | L. owenii | 34448 | 143467 | T | Dendroctonus valens | California, USA | M.J. Wingfield | MT637217 | KF515912.1 | KF515884.1 | – |

| L. seifertii # | L. seifertii | 34620 | 143478 | T | Dendroctonus valens on Pinus resinosa | New Hampshire, USA | M.J. Wingfield | MT637224 | KF515911.1 | KF515885.1 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. lundbergii complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. koreana | L. koreanum | 14199 | KUC2078 | T | Tomicus piniperda on Pinus koraiensis | South Korea | J.J. Kim | OM501431 | OM514733 | OM631808 | OM631633 |

| G. yunnanensis | L. yunnanense | 5152 | – | Pinus yunnanensis | China | X.D. Zhou | AY707207 | – | – | – | |

| L. absconditum | L. absconditum | 39763 | 136527 | T | Orthotomicus laricis on Pinus nigra | Spain | P. Romón | OM501415 | OM514761 | OM631790 | – |

| L. celere | L. celere | 12422 | 123628 | T | Pinus semaonensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406834 | – | HQ406858 | – |

| L. conjunctum | L. conjunctum | 12473 | 123631 | T | Pinus yunnanensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406831 | – | HQ406855 | – |

| L. lundbergii * | L. lundbergii | 2190 | 138716 | Pinus sylvestris | Norway | H. Roll-Hansen | OM501432 | OM514772 | OM631809 | OM631634 | |

| L. manifestum | L. manifestum | 12436 | 123622 | T | Larix olgensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406839 | – | HQ406863 | – |

| L. pinicola | L. pinicola | 2398 | – | T | Hylastes sp. on Pinus sp. | Canada | J. Juzwik | OM501439 | OM514775 | – | – |

| L. shansheni | L. shansheni | 44462 | 141895 | T | Ips typographus on Picea sp. | China | R. Chang, S.F. Chen | MH144097 | – | MH124373 | – |

| L. sosnaicola # | L. sosnaicola | 52084 | 147023 | T | Pinus sylvestris | Poland | D. Jazłowiecka | MT210337 | MT210353 | MT210397 | – |

| L. truncatum | L. truncatum | 28 | 929.85 | T | Pinus taeda | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | DQ062052/AY935626 | – | DQ062019 | – |

| L. wushanense | L. wushanense | – | YMF1.04936 | T | Pinus sp. | China | J. Lu | MG878407 | – | MG878409 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. olivaceum complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. cucullata * | L. cucullatum | 1035 | 218.83 | T | Ips typographus | Norway | H. Solheim | OM501423 | OM514724 | OM631801 | OM631626 |

| G. davidsonii | L. davidsonii | – | YCC611 | Logs of Larix kaempferi infested with Ips subelongatus | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | GU134165 | – | – | – | |

| G. olivacea | L. olivaceum | 23348 | – | Pinus sylvestris | Finland | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | OM501434 | OM514735 | OM631811 | – | |

| G. olivaceapini | L. olivaceapini | 116 | 504.86 | E | Pinus ponderosa in Dendroctonus sp. | Arizona, USA | T. Hinds | OM501433 | OM514736 | OM631810 | OM631635 |

| G. sagmatospora | L. sagmatosporum | 43846 | UAMH6971 | Pinus strobus | Canada | B. Grylls, K. Seifert | OM501449 | OM514743 | OM631823 | – | |

| G. vesca | L. vescum | 34186 | 800.73 | Ips pilifrons, Dendroctonus engelmanni in Picea engelmannii | Colorado, USA | F.F. Lombard, R. W. Davidson | OM501457 | OM514745 | – | – | |

| L. brevicolle | L. brevicolle | – | 150.78 | Beetle gallery in Populus tremuloides | Colorado, USA | R.W. Davidson | MH055549 | AF155670 | MH055635 | – | |

| L. breviuscapum | L. breviuscapum | 38888 | 136507 | T | Picea crassifolia infested with Polygraphus poligraphus | China | M.L. Yin, X.D. Zhou | OM501419 | OM514763 | MN517742 | – |

| L. conplurium | L. conplurium | 23289 | 128834 | P | Pinus sylvestris | Finland | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | OM501422 | OM514765 | OM631800 | OM631625 |

| L. duchongi | L. duchongi | 44455 | 141897 | T | Ips typographus on Pinus koraiensis | China | R. Chang | MH144122 | – | MH124398 | – |

| L. erubescens | L. erubescens | 40672 | 278.54 | E | Pinus sylvestris | Sweden | A. Mathiesen-Käärik | OM501425 | OM514767 | OM631803 | OM631628 |

| L. flavum | L. flavum | 51797 | 144099 | T | Quercus robur | Poland | R. Jankowiak | MH055548 | – | MH055634 | – |

| L. francke-grosmanniae | L. francke-grosmanniae | 445 | 356.77 | T | Hylecoetus dermestoides on Quercus sp. | Germany | H. Francke-Grosmann | OM501427 | OM514768 | OM631805 | OM631630 |

| L. sylvestris | L. sylvestris | 23300 | 128833 | P | Picea abies | Finland | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | OM501454 | OM514777 | OM631827 | – |

| L. pseudoalbum | L. pseudoalbum | 40671 | 276.54 | T | Blastophagus piniperda in Pinus sylvestris | Sweden | A. Mathiesen-Käärik | MN516723 | MN516723 | MN517755 | OM631641 |

| L. raffai # | L. raffai | 34451 | 143468 | T | Dendroctonus valens | California, USA | M.J. Wingfield | MT637219 | MT637211 | MT637206 | – |

| L. rhizoidum | L. rhizoidum | 22809 | 136512 | T | Hylastes ater on Pinus radiata | Spain | P. Romón, X.D. Zhou | MN516724 | MN516724 | MN517748 | OM631644 |

| L. tardum | L. tardum | 51789 | 144091 | T | Trypodendron domesticum on Fagus sylvatica | Poland | R. Jankowiak | MH055529 | – | MH055615 | – |

| L. vulnerum | L. vulnerum | 51794 | 144096 | T | Fagus sylvatica | Poland | R. Jankowiak | MH055534 | – | MH055620 | – |

| L. xiningense# | L. xiningense | 38891 | 136509 | T | Polygraphus poligraphus in Picea crassifolia | China | M.L. Yin, X.D. Zhou | MN516732 | MN516732 | MN517752 | OM631637 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. piceiperdum complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. aenigmatica | L. aenigmaticum | 2199 | – | T | Ips typographus japonicus on Picea jezoensis | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | OM501416 | OM514716 | OM631791 | OM631619 |

| G. europhioides | L. europhioides | 2811 | 115245 | Picea rubens | New York, USA | T. Harrington | OM501426 | OM514729 | OM631804 | OM631629 | |

| G. laricis | L. laricis | 1913 | 120188 | Larix sp. | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | – | DQ294393 | – | – | |

| G. piceiperdum * | L. piceiperdum | 16768 | 138719 | Picea glauca | Canada | K. Harrison | OM501435 | OM514738 | OM631812 | OM631636 | |

| G. pseudoeurophioides | L. pseudoeurophioides | – | WIN(M)42 | – | Canada | J. Reid | EU879136 | – | – | – | |

| L. heilongjiangense | L. heilongjiangense | 44456 | 141702 | T | Ips typographus on Pinus koraiensis | China | R. Chang | MH144098 | – | MH124374 | – |

| L. zhangii | L. zhangii | – | MUCL55162 | T | Ips subelongatus on Larix gmelinii | China | X. Liu | KM236108 | – | KM974275 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. procerum complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| L. bhutanense | L. bhutanense | 18649 | 122076 | T | Pinus wallichiana | Bhutan | M.J. Wingfield | OM501418 | OM514762 | OM631794 | – |

| L. gracile | L. gracile | 12398 | 123623 | T | Pinus armandii | China | X.D. Zhou | OM501430 | OM514769 | – | – |

| L. latens | L. latens | 12438 | 124023 | T | Picea koraiensis | China | X.D. Zhou, Z.W. de Beer | HQ406845 | – | HQ406869 | – |

| L. longiconidiophorum | L. longiconidiophorum | 2004 | 135624 | T | Hylastes sp. on Pinus densiflora | Japan | M.J. Wingfield | KM491421 | – | KM491471 | – |

| L. peucophilum | L. peucophilum | 2876 | 120191 | Picea sp. | New York, USA | D. Bergdalh | – | – | – | – | |

| L. pini-densiflorae | L. pini-densiflorae | 5157 | 115261 | T | Pinus densiflora | Japan | H. Masuya | OM501438 | OM514774 | OM631815 | |

| L. procerum * | L. procerum | 34542 | 138288 | E | Dendroctonus valens on Pinus resinosa | Maine, USA | M.J. Wingfield | OM501442 | OM514778 | OM631816 | OM631639 |

| L. profanum | L. profanum | 10552 | 120307 | T | Carya sp. | Alabama, USA | L. Eckhardt | OM501443 | OM514779 | OM631817 | OM631640 |

| L. sibiricum | L. sibiricum | 4481 | 115260 | T | Monochamus urussoni on Abies sibitica | Russia | V.P. Vetrova | OM501451 | OM514783 | – | – |

| L. sinense | L. sinense | 38171 | 316515 | P | Pinus elliottii | China | M. Yin, R. Chang, X.D. Zhou | OM501452 | OM514784 | OM631825 | OM631647 |

| L. sinoprocerum | L. sinoprocerum | 29990 | MUCL46532 | T | Pinus tabuliformis | China | Q. Lu | OM501453 | OM514785 | OM631826 | OM631648 |

| L. yichunense | L. yichunense | 44464 | 141705 | T | Ips typographus on Picea sp. | China | R. Chang, S.F. Chen | MH144114 | – | MH124390 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. serpens complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. alacris | L. alacre | 621 | 128830 | T | Pinus pinaster | Portugal | M. de Famtima Moniz | OM501417 | OM514717 | OM631792 | OM631620 |

| G. serpens | L. serpens | 305 | 141.36 | T | Pinus sylvestris | Italy | G. Goidànich | OM501450 | – | OM631824 | OM631646 |

| L. castellanum | L. castellanum | 2320 | 128698 | P | Pinus occidentalis | Dominican Republic | R. Webb | OM501420 | OM514764 | OM631798 | OM631623 |

| L. gibbsii | L. gibbsii | 36371 | – | T | Hylastes opacus on Pinus sylvestris | England, UK | J. Gibbs | OM501429 | – | OM631807 | OM631632 |

| L. rhodanense | L. rhodanense | 16438 | 138284 | T | Pinus sylvestris | Switzerland | U. Heiniger | OM501448 | – | OM631822 | OM631645 |

| L. yamaokae | L. yamaokae | 4726 | 129732 | T | Pinus densiflora | Japan | H. Masuya | – | – | OM631835 | OM631655 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: L. wageneri complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. wageneri * | L. wageneri var. ponderosum | 279 | – | Pinus sp. | USA | T. Harrington | OM501458 | OM514746 | OM631831 | OM631651 | |

| L. douglasii * | L. douglasii | 2076 | – | P | Pseudotsuga menziesii | New Mexico, USA | M. Midke | OM501424 | OM514766 | OM631802 | OM631627 |

| L. neomexicanum | L. neomexicanum | 2079 | 168.93 | T | Pinus ponderosa | New Mexico, USA | T. Harrington, W Livingston | AY553382 | – | AY536176 | – |

| L. reconditum | L. reconditum | 15 | 116348 | Zea mays | South Africa | W. Jooste | AF343690 | – | AY536177 | – | |

| L. wageneri var. pseudotsugae* | L. wageneri var. pseudotsugae | 154 | 115246 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | USA | T. Harrington | OM501459 | OM514747 | OM631832 | OM631652 | |

| L. wageneri var. wageneri* | L. wageneri var. wageneri | 53 | 139665 | Pinus ponderosa | California, USA | T. Harrington | OM501460 | OM514788 | OM631833 | OM631653 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: Group A | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| L. pineti | L. pineti | 3837 | 115257 | Pinus sp. | Indonesia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | OM631814 | OM631638 | |

| L. ningerense | L. ningerense | 41786 | 139663 | T | Coccotrypes cyperi on Pinus kesiya | China | S. Taerum | MG205674 | – | MG205765 | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium: Group B | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. cainii | L. cainii | 24907 | – | Picea sp. | Canada | C. Breuil | OM501389 | OM514722 | OM631797 | OM631622 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium Incertae sedis (based on our data) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. huntii | G. huntii | 2868 | 118780 | Pinus strobus | North Carolina, USA | V. Lackner | AY553394 | – | DQ354938 | – | |

| G. leptographioides | G. leptographioides | 481 | 144.59 | Quercus sp. | New York, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | DQ294382 | – | – | |

| G. truncicola | G. truncicola | – | – | Dendroctonus sp. on Picea sp. | USA | – | – | – | – | – | |

| L. albopini | L. albopini | ^26 | – | Hylastes sp. on Pinus sp. | USA | – | AF343695 | – | – | – | |

| L. alethinum | L. alethinum | ^3763 | – | Galleries of Hylobus abietis on log of Pinus nigra var. maritima | England, UK | A. Uzunovic | AY553391 | – | AY536185 | ||

| L. calophylli | L. calophylli | 752 | 277.51 | Cryphalus sp. on Calophyllum sp. | Mauritius | J.A. Stevenson | MH856855 | MH868375 | – | – | |

| L. microsporum | L. microsporum | – | – | T | Fagus sp. | Mississippi, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | – | – | – |

| L. obscurum | L. obscurum | 37429 | 125.39 | Pinus sp. | USA | R.W. Davidson | – | – | – | – | |

| L. pityophilum | L. pityophilum | 2840 | 109706 | Pinus nigra | Italy | S. Frisullo | OM501441 | OM514776 | – | – | |

| L. rostrocylindricum | L. rostrocylindricum | – | – | Quercus sp. | Connecticut, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | – | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Leptographium & Grosmannia incertae sedis (based on our data) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| L. guttulatum | L. guttulatum | 1310 | 120185 | T | Tomicus piniperda on Pinus sylvestris | England, UK | J. Gibbs | – | OM514770 | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Lineage III | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G. crassivaginata | G. crassivaginata | 90 | 120178 | – | – | T. Hinds | AF343673 | – | – | – | |

| L. alneum# | L. alneum | 52076 | 144901 | T | Dryocoetes alni infesting Populus tremula | Poland | K. Miœkiewicz | MN900997 | MN900997 | MN901024 | – |

| L. piriforme | L. piriforme | 25381 | UAMH10681 | P | Beetle caught in a trap baited with coyote dung | Canada | M.D. Greif | OM501440 | – | – | – |

|

| |||||||||||

| Lineage VI | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| L. verrucosum | L. verrucosum | 17160 | 112420 | T | Xyleborus dryographus | Germany | H. Gebhardt | OM501456 | OM514787 | OM631830 | OM631650 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Masuyamyces gen. nov. | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| O. ambrosium | M. ambrosius | 1024 | 210.64 | Wood of Pinus sylvestris | Netherlands | J.A. von Arx | OM501465 | OM514793 | OM631836 | OM631656 | |

| O. acarorum | M. acarorum | 41850 | 139748 | T | Orthotomicus angulatus on Pinus kesiya | China | S. Taerum | MG205657 | – | – | – |

| O. botuliforme | M. botuliformis | 14493 | – | Cryphalus jeholensis | Japan | H. Masuya | OM501471 | OM514799 | OM631837 | – | |

| O. jilinense | M. jilinensis | 40491 | 141894 | T | Ips typographus on Picea sp. | China | X. D. Zhou | MH144094 | – | MH124370 | – |

| O. lotiforme # | M. lotiformis | – | MUCL55165 | T | Ips subelongatus on Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica | China | X. Meng | MK748185 | – | – | – |

| O. massoniana | M. massonianae | – | MUCL55179 | T | Monochamus sp. on Pinus sp. | China | Q. Lu | KY094067 | – | – | – |

| O. pallidulum | M. pallidulus | 23278 | 128118 | T | Pinus sylvestris | Russia | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | HM031510 | – | – | – |

| O. saponiodorum | M. saponiodorus | 28135 | 128302 | Pinus sylvestris | Russia | R. Linnakoski | OM501512 | OM514838 | OM631838 | OM631657 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ophiostoma: O. clavatum complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| O. ainoae | O. ainoae | 1037 | 205.83 | T | Picea abies | Norway | H. Solheim | OM501463 | OM514791 | – | – |

| O. brevipilosi | O. brevipilosi | 41873 | 139660 | T | Tomicus brevipilosus on Pinus kesiya | China | S. Taerum | MG205660 | – | MG205732 | – |

| O. brunneociliatum | O. brunneociliatum | 5212 | – | Larix sp. | Scotland, UK | T. Kirisits | KU184422 | – | KU184379 | – | |

| O. brunneolum | O. brunneolum | 23145 | – | A | Picea abies | Russia | J. Ahtiainen, P. Niemelä | OM501472 | OM514800 | OM631843 | OM631663 |

| O. clavatum | O. clavatum | 37983 | 141080 | E | Ips acuminatus on Pinus sylvestris | Sweden | C. Villari | OM501477 | OM514805 | OM631848 | – |

| O. hongxingense # | O. hongxingense | – | CFCC52695 | T | Ips subelongatus on Larix gmelinii | China | Q. Lu | MK748194 | – | MN896068 | – |

| O. japonicum | O. japonicum | 2202 | YCC099 | T | Ips typographus japonicus on Picea jezoensis | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | OM501492 | – | OM631855 | OM631673 |

| O. jiamusiensis | O. jiamusiensis | 40512 | 141893 | T | Ips typographus on Picea sp. | China | X.D. Zhou | MH144064 | – | MH124343 | – |

| O. macroclavatum | O. macroclavatum | 23115 | 141081 | T | Pinus sylvestris | Russia | Z.W. de Beer | HM031499 | – | KU094765 | – |

| O. peniculi # | O. peniculi | – | CFCC52687 | T | Ips subelongatus infesting Larix gmelinii | China | Q. Lu | MK748198 | – | MN896063 | – |

| O. poligraphi | O. poligraphi | 38899 | 136517 | T | Polygraphus poligraphus on Picea crassifolia | China | M. Yin, S. Taerum, X.D. Zhou | OM501507 | OM514832 | OM631871 | OM631688 |

| O. pseudocatenulatum | O. pseudocatenulatum | 43103 | 141276 | T | Ips cembrae on Larix decidua | Poland | R. Jankowiak | KU094686 | – | KU094774 | – |

| O. shangrilae | O. shangrilae | 38901 | 136519 | T | Ips shangrila on Picea purpurea | China | M. Yin, S. Taerum, X.D. Zhou | OM501514 | OM514840 | OM631879 | OM631695 |

| O. songshui | O. songshui | 44473 | 141707 | T | Ips typographus on Picea sp. | China | R. Chang, S.F. Chen | MH144065 | – | MH124344 | – |

| O. subelongati # | O. subelongati | – | CFCC52693 | T | Ips subelongatus infesting Larix gmelinii | China | Q. Lu | MK748200 | – | MN896064 | – |

| O. tapionis | O. tapionis | 23266 | 128122 | P | Picea abies | Russia | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | OM501516 | OM514842 | OM631881 | OM631697 |

| Ophiostoma sp. 3 (Hyalorhinocladiella sp. 2) | Ophiostoma sp. 3 (Hyalorhinocladiella sp. 2) | 43851 | UAMH10642 | Ips sp. | Canada | S. Massoumi Alamouti | OM501524 | OM514851 | OM631888 | – | |

| Ophiostoma sp. 4 (Hyalorhinocladiella sp. 1) | Ophiostoma sp. 4 (Hyalorhinocladiella sp. 1) | 43848 | UAMH10639 | Ips sp. | Canada | S. Massoumi Alamouti | OM501525 | OM514852 | OM631889 | OM631704 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ophiostoma: O. ips complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| O. adjuncti | O. adjuncti | 1025 | 314.77 | T | Stained sapwood in Pinus ponderosa | New Mexico, USA | R.W. Davidson | OM501462 | OM514790 | – | OM631658 |

| ‘O. arborea’ | ‘O. arborea’ | – | WIN(M)69-23 | Picea mariana | Canada | A. Olchowecki, J. Reid | – | – | – | – | |

| O. bicolor | O. bicolor | 23169 | – | Pinus sylverstris | Russia | J. Ahtiainen, P. Niemelä | OM501470 | OM514798 | OM631842 | OM631662 | |

| O. columnare | O. columnare | – | WIN(M)71-27 | Pinus banksiana | Canada | A. Olchowecki, J. Reid | – | – | – | – | |

| O. fuscum | O. fuscum | 23195 | 128124 | P | Pinus sylverstris | Finland | Z.W. de Beer, P. Niemelä | OM501483 | OM514810 | – | OM631670 |

| O. gilletteae # | O. gilletteae | 30681 | 143458 | T | Dendroctonus valens | Washington, USA | N. Gillette | MT637227 | – | – | – |

| O. guatemalensis | O. guatemalensis | 44221 | – | T | Pinus patula | Guatemala | I. Barnes, J. Garnas | – | – | – | – |

| O. hyalothecium | O. hyalothecium | – | ATCC28825 | Pinus contorta | Wyoming, USA | R.W. Davidson | – | AF137284 | – | – | |

| Tuberculariella ips | O. ips-like sp. 6 | 14175 | 435.34 | T | Ips sp. on Pinus sp. | Minnesota, USA | J.G. Leach | OM501487 | OM514813 | OM631854 | OM631672 |

| O. ips * | O. ips | 19371 | 138721 | Pinus taeda | Louisiana, USA | X.D. Zhou | OM501486 | OM514812 | OM631853 | OM631671 | |

| O. manchongi # | O. manchongi | 41954 | 141906 | Uropodoidea sp. in Ips shangrila gallery on Picea purpurea | China | S.J. Taerum | MH121662 | – | – | – | |

| O. montium | O. montium | 15419 | – | Pinus contorta | Idaho, USA | B. Bentz | OM501498 | OM514822 | OM631861 | OM631678 | |

| O. pseudobicolor # | O. pseudobicolor | – | CFCC52683 | T | Ips subelongatus in Larix gmelinii | China | Q. Lu | MK748188 | – | – | – |

| O. pulvinisporum | O. pulvinisporum | 9022 | 118673 | T | Pinus pseudostrobus | Mexico | X.D. Zhou | OM501509 | OM514835 | OM631874 | OM631691 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ophiostoma: O. minus complex | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ‘O. album’ | ‘O. album’ | – | MUCL55189 | T | Monochamus alternatus gallery on Pinus massoniana | China | Q. Lu, Y.Y. Lun | KY094073 | – | – | – |

| O. exiguum | O. exiguum | – | – | Pinus virginiana | West Virginia, USA | G.G. Hedgcock | – | – | – | – | |

| O. kryptum | O. kryptum | – | 116190 | T | Tetropium on Picea | Austria | T. Kirisits | AY305685 | – | – | – |

| O. minus | O. minus | 43873 | UAMH4917 | Dendroctonus ponderosae on Pinus flexillis | Canada | P. Muruyama | OM501497 | OM514821 | OM631860 | OM631677 | |

| ‘O. olgensis’ | ‘O. olgensis’ | – | CXY1410 | T | Ips subelongatus on Larix olgensis | China | Q. Lu | KU551303 | – | KU551297 | – |

| O. minus (in Europe O. pini) | O. minus (in Europe O. pini) | 43346 | – | Pinus sylvestris | Poland | T. Tomasz | – | – | – | – | |

| O. pseudominus | O. pseudominus | 43878 | UAMH9721 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Canada | J. Reid, B Reid | OM501508 | OM514834 | OM631873 | OM631690 | |

| O. pseudotsugae | O. pseudotsugae | – | D48/3 | – | Canada | H. Solheim | AY542501 | – | – | – | |